Archive for the 'Global film industry' Category

Around the world in 750 pages

The Double Life of Véronique (1992).

DB here:

Just over twenty years ago Kristin and I embarked on a perilous task. We decided to write a synoptic history of world cinema.

The task wasn’t perilous because it was innovative. Since the 1930s, there has been no shortage of historical surveys of international filmmaking, and such items continue to be published. But when we decided on this project in 1987, we wanted something different.

Soon that book will appear in a third edition. We take this occasion to explain the whys and wherefores.

Just start over

Daisies (1966).

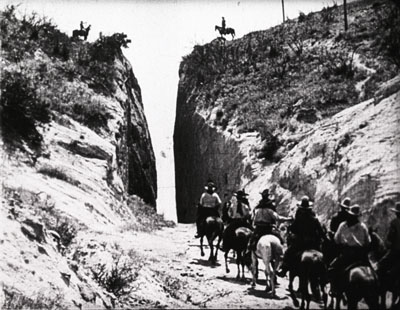

For a very long time, and sometimes still, film histories written by Americans took a very partial look at the phenomenon of cinema. For one thing, they tended to focus on a series of masterpieces, films that had been deemed important within a narrow canon. The earliest lineup went pretty much this way: Lumière films, Méliès’ Trip to the Moon, Porter’s Great Train Robbery, Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and/ or Intolerance. Then came national schools, such as German Expressionism (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), Soviet Montage (Battleship Potemkin), and Continental Dada and Surrealism (Entr’acte, The Andalusian Dog). Early sound was M and Sous les toits de Paris and maybe Love Me Tonight. The 1940s was Grapes of Wrath and Citizen Kane and Enfants du Paradis and Italian Neorealism. And so on.

But in the 1970s archivists began opening their doors to researchers. Thanks to wider and deeper viewing, new film historians, young and old, were questioning the canon. André Gaudreault and Charles Musser showed that Porter’s Life of an American Fireman, which supposedly gave birth to crosscutting, did not do so; in fact the version people had used for years was a re-cut print! In Jay Leyda’s seminars at NYU, young scholars like Roberta Pearson were tracing what Griffith actually did and didn’t do, a task taken up by Joyce Jesionowski as well. At the same time, Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Noël Burch, and others began questioning the idea that “our cinema” developed step by step from “primitive” beginnings. In England, Ben Brewster, Barry Salt, and others were minutely analyzing changes in film technique in the earliest years. Here at Madison, Tino Balio and Doug Gomery were revising the study of Hollywood as a business enterprise. Specialists working on national cinemas, from Russia, Italy, and the Nordic countries, were showing that there was far more diversity in world cinema than was dreamt of in orthodox histories.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution, as well as particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I did work on European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution, as well as particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I did work on European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

That’s what made our task perilous. Everything, it seemed, needed to be rethought.

Most obviously, countries outside Europe and North America had been neglected. One of my favorite film statistics is this, to quote from our book:

In the mid-1950s, the world was producing about 2800 feature films per year. About 35 percent of these came from the United States and western Europe. Another 5 percent were made in the USSR and the Eastern European countries under its control. . . . Sixty percent of feature films were made outside the western world and the Soviet bloc. Japan accounted for about 20 percent of the world total. The rest came from India, Hong Kong, Mexico, and other less industrialized nations. Such a stunning growth in film production in the developing countries is one of the major events in film history.

Traditional histories, and film history textbooks, had virtually ignored the bulk of film-producing nations. Only one or two major directors would step in from the shadows. Kurosawa summed up Japan, Satayajit Ray stood in for India. And the books’ layout of chapters indicated this second-class status. The history of film was Euro-American, with East Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa, appearing, if at all, in periods when westerners first got glimpses of their film culture. So Japan was typically first mentioned after World War II, when Rashomon won a prize at the Venice Film Festival. One would hardly know that there were many, and many great, Japanese filmmakers working in a long-standing tradition.

As if this weren’t enough, we were determined to include other varieties of artistic filmmaking. Documentary cinema, animation, and experimental film had attracted subtle historians like Bill Nichols, Mike Barrier, and P. Adams Sitney. We weren’t experts in these areas, but we were keenly interested in the debates in that domain, and so, guided by these and other scholars, we sought to integrate the histories of documentary, avant-garde, and animated cinema into our survey.

Kristin and David’s excellent adventure

Straight Shooting (1917).

In sum, we decided that we could write a plausible international history of cinema—not a be-all and end-all, but a new draft that reflected the rich variety of new findings and fresh perspectives. Like all historians, we had to be selective. We couldn’t, for instance, track every nuance of the “false starts and detours” in early film technique. More globally, we decided to concentrate on three lines of inquiry.

First, we studied changes in modes of film production and distribution. This inquiry committed us to a version of industrial history. How filmmaking was embedded in particular times and places, how it connected to local culture and national politics: these factors affected the ways films were made and circulated. For example, the early distribution of films followed the trade routes of late nineteenth-century imperialism. That global system started to crack with the start of World War I. A new world power, the United States, became the major film exporting country—a position it has enjoyed for most years since then.

Secondly, we studied changes in film form, style, and genre. We treated these artistic matters as not wholly the products of individual innovators but also as more widely-developed practices and norms. This emphasis on norms allowed us to link, in some degree, the development of technique to opportunities and constraints presented by film industries.

This angle of approach also meant looking at older works with a fresh eye, informed by others’ research but also by our own interests in film as an art. We were obliged to seek out films lying outside the orthodox story. Birth and Caligari and M feature in our account, but so do The Cheat and Assunta Spina and Liebelei. In those pre-DVD days, few of the titles we sought could be found on video, but we preferred to watch film on film anyway. So it was off to the archives. Fortunately, many collections were wide-ranging. We saw Egyptian and Swedish films in Rochester, French and Italian films in London, Indian and Japanese films in Washington, D. C., Polish and African films in Brussels. Committed to documenting our claims with frame enlargements, not production stills, we were lucky to be able to take photos from many of the movies we saw.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

For example, we could point to the emergence of tableau cinema in many countries in the 1910s. We could consider various models of state-controlled cinema in the 1930s and discover the “New Waves” that emerged not only in France but around the world in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Citizen Kane popularized a “deep-focus” look, but comparative study showed us that its principles were prefigured in Soviet cinema of the 1930s and spread to most major filmmaking nations in the 1940s. Not all trends march in lockstep, but there was enough synchronization to let us plot broad waves of change across the 100 years of film. Our aim was a truly comparative film history.

As a kind of overarching commitment, we wanted readers to think about what historical processes had shaped earlier historical frames of reference. How, for instance, did the “standard story” and the mainline canon get established in the first place? Part of the answer lies in the growth of film journalism and film archives. Why did Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, and other directors get so much fame in the 1950s and 1960s? True, they made exceptional films, but so did many other directors who remained unknown to a wider public. We suggested that the “golden age of auteurs” owed a good deal to developments in film criticism and to the postwar growth of film festivals. What led Japanese anime to a period of international popularity in the 1980s? Not only worldwide television distribution, but also devoted fans who spread their gospel through fanzines, videocassettes, and the youthful Internet. The “institutional turn” in film research of the 1970s and 1980s pushed us to consider how film industries and international film culture governed the way films were made and circulated.

The research programs that were launched in the 1970s were characterized by a greater self-consciousness than we had seen before. Historians questioned their assumptions and explanations. Why attribute originality only to “great men” without also examining their circumstances? Why presuppose that film technique grows and progresses in a linear way? To capture this new self-consciousness about purposes and methods, we incorporated something that had never been seen in a film history before: an introduction to historiography. In its latest incarnation it can be found elsewhere on this site. We also appended to each chapter short “Notes and Queries” discussing intriguing side issues, debates in the field, and topics for further research.

Up-to-date, and beyond

10 Canoes (2006).

The result of our efforts was first published by McGraw-Hill in 1994 as Film History: An Introduction. A second edition appeared in late 2002. More recently, we’ve spent about twenty months preparing a third edition, which will be published on 20 February this year.

We thought that writing the first edition was bloody hard, and it didn’t get any easier on the second or third pass. As usual, however, visiting new material broadens your compass. Writing my portions of the first edition had a profound impact on my research, but also on my personal tastes. The activity awakened my interest in Hindi cinema of the 1950s, Latin American cinema of the 1960s, experimental work of the 1980s, and African film of the 1990s. On this third round, I was caught up in the innovations of contemporary Korean film and of avant-gardists like Sharon Lockhart. Overall, our urge to trace cinematic creativity around the world led us to a greater appreciation of the wonders of film.

Film History‘s third edition consists of six parts. The first looks at early cinema, from the 1880s to the end of the 1910s. The second considers the late silent era through the 1920s and slightly beyond. Part Three surveys the international development of sound film, up to 1945. The postwar era, from 1945 to the end of the 1960s, constitutes Part Four. We next consider the contemporary period, generously conceived as running from the 1970s to the present. The last section, Cinema in the Age of Electronic Media, makes up for the broad compass of Part Five by reconsidering trends that took shape during the 1980s.

Film History‘s third edition consists of six parts. The first looks at early cinema, from the 1880s to the end of the 1910s. The second considers the late silent era through the 1920s and slightly beyond. Part Three surveys the international development of sound film, up to 1945. The postwar era, from 1945 to the end of the 1960s, constitutes Part Four. We next consider the contemporary period, generously conceived as running from the 1970s to the present. The last section, Cinema in the Age of Electronic Media, makes up for the broad compass of Part Five by reconsidering trends that took shape during the 1980s.

What’s new in this edition? Several small changes have been made in the early portions to reflect newly available films and filmmakers now recognized as important. We have updated coverage of documentary with discussions of the rise of the theatrical doc and its two most striking practitioners, Errol Morris and Michael Moore. We have likewise expanded our section on avant-garde filmmaking by considering “paracinema,” which should have been in earlier editions, and the increase in cinema presented as installations and gallery works.

As for national cinema developments, we have extended our survey of western Europe and the USSR (Chapter 25), continental and subcontinental cinemas such as Latin America, Africa, and India (Chapter 26), and East Asia and Oceania (Chapter 27). New coverage is given to the recovery of the Russian and Chinese industries, the increasing world presence of Bollywood, and fresh talent from the Middle East and South Korea.

The book’s last part continues to host a chapter (28) on American cinema’s development in the light of home video and the rise of independent filmmaking; the blockbuster and Mumblecore are among the subjects we tackle. As in the second edition, we devote a chapter to globalization, which lets us trace the struggle between Hollywood’s global blockbusters and countervailing trends in other regions. This chapter allows us to study other globalizing processes, such as multiplexing, the Internet, fan culture, piracy, and diasporic populations.

Chapter 30 is new to this edition. It examines the effects of the digital revolution on all aspects of film production, as well as on new means of distribution and exhibition. The subjects covered include 3-D animation, DIY independents, and online distribution. We end by recognizing film as no less international an art form than it was in the earliest decades, when silent films slipped freely across national borders.

As in the early editions, we’ve tried to synthesize contemporary contributions but also add our own research and our own interpretations. Here, for example, is our very cine-centric conclusion about “the death of film.”

Will this barrage of new media ultimately overwhelm the cinema? Will the Internet, video games, and personal music players take over as the preferred forms of entertainment? Possibly, but there is evidence against that notion.

Each time that a digital platform appeared, it initially lacked the capacity to show films. Yet each platform adapted itself in order to add that capacity. In the 1990s, computers acquired the power to display movies. The Internet originally did not show films, but now it has Quicktime and downloads. Cell phones started out as communication devices, but later models included a camera and screen so that users could shoot and view films. The first game consoles could not show movies, but after the advent of DVDs, the next generation of machines became combination players. The original iPod and other personal music devices were strictly for audio, but Apple added the capacity to download digital video from computers, DVDs, and the Internet. The iPod enlarged its screen to better display films, even though that meant abandoning the signature click-wheel in favor of touch-screen controls.

Far from killing movies, digital media have allowed them to leave the theater and our living rooms. Now they can travel with us almost anywhere. In effect, film has reshaped the new media to accommodate it. As new digital devices emerge, we suspect that they, too, will adjust themselves to the cinematic traditions that have developed over 110 years.

No book can be definitive, partly because things change astonishingly fast. When we wrote the revision, DreamWorks was firmly within the Paramount family, and our chart of media conglomerates on p. 683 left it there. In page proofs, we shifted it when it seemed all but certain to move to Universal. Now comes the news that DreamWorks has signed with Disney. Likewise, the flow of important research hasn’t abated, and valuable books, like Jay Beck and Tony Grajeda’s Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound, were published after we went to press. Another peril of writing contemporary history, then: Keeping up.

To squeeze in our new material, we’ve had to excise the historiography essay mentioned above, as well as our Notes and Queries and our plump bibliographies. Those, all updated, have appeared at the McGraw-Hill site. Even if you’re not reading the book, feel free to go to the Student Edition tab and browse through the Notes and Queries for each chapter. Some of these brief, bloggish items may pique your interest.

Without exactly planning to do it, we seem to have come up with the most wide-ranging, extensively illustrated survey of world cinema history available in English. The third edition of Film History: An Introduction runs to 750 large-format pages, not counting the index. It contains hundreds of black-and-white frame enlargements and thirty pages of color illustrations.

We hope that if you’re interested in film history you’ll take a look. Feel free to write to us with your thoughts, especially if you find misprints (we’ve been chasing them for months) and factual errors. We’d also appreciate comments about our larger arguments and interpretations. We improve only by constantly rechecking what we say and how we say it.

The quotation about 1950s world film output comes from Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction, third ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009), 373.

Tokyo Drifter (1966).

Filling the New Line gap

The Loews Santa Monica Beach Hotel, one of the AFM venues

Kristin here-

The 2008 American Film Market started yesterday. Like the film festivals at Cannes, Toronto, and, increasingly, Berlin, the AFM is one of the major places where independent and foreign-language films get sold. Distributors from all over the world come to sell their products and to buy the films that they will release at home. It seems a good occasion to look at what effect the folding-in of New Line Cinema into a unit within Warner Bros. early this year has had on the international independent film market.

The good old days

In my book The Frodo Franchise, Chapter 9 dealt with the impact of The Lord of the Rings on the film industry. There I discuss what effects the trilogy had on New Line and its parent company Time Warner. I also analyze the rise of the fantasy genre, the technological advances, and the boost given to the depressed indie market internationally. The 26 international independent distributors that financed a substantial portion of the film’s production through presales—with commitments to all three parts, sight unseen, at very steep prices—grew dramatically as a result of its success.

In 2001, an international slump in independent and foreign-language cinema started. The causes were complex, and I detail them in the book; they included a sag in advertising, the dot-com bust, the September 11 attacks, and the American dollar’s high exchange rate. With perfect timing, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring came out in December of 2001. Its theatrical and DVD earnings in 2002 poured money into the market through the 26 companies’ ability to buy new product when other distributors were still strapped for cash. By early 2004, the market had substantially recovered. Rings wasn’t the only factor aiding that recovery, but it was a major one.

That section of Chapter 9 is one of the parts of the book I’m proudest of. Most people interested in film knew something about most of the topics I covered. They were probably at least vaguely aware of the video games and other tie-in products, the highest successful internet campaign, the growth in filmmaking and tourism in New Zealand, and so on. But the fact that this massive blockbuster was an independently financed film, sold on the independent market, and highly beneficial to that market was something completely unknown except to specialists within the industry. I cottoned onto it only because there were a few references to these distributors’ unusual buying power during the coverage of the 2003 Cannes Film Festival and AFM in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.

Beyond those brief discussions, there was really no way I could research the topic without talking to people involved. That meant interviewing some of the executives of those 26 companies and someone very expert in the international indie market. A very helpful source was Mads Nedergaard, then of SF-Film, Copenhagen, who provided marvelous information for my major case study in that chapter. For the expert, I decided upon Jonathan Wolf, then and now the Managing Director of the AFM. Luckily he agreed to be interviewed. During our conversation Jonathan remarked that he had been very struck that I understood that Rings was an independent film and that it had had a positive impact on international markets. I gather that’s why he agreed to the interview, during which he furnished me with valuable insights. Those two interviews really made that part of the chapter possible.

Despite the huge success of the trilogy, New Line continued to function as an independent, financing its films through presales of distribution rights and of licensing fees for ancillary products. It continued to sell them at events like the AFM, as well as having regular output deals with some of the same overseas companies that it had been dealing with for nearly a decade. New Line was one of the main U.S. firms supplying such distributors. Its growing success ultimately became part of what got the studio into trouble.

What had worked so well for Rings continued to work until the blockbuster fantasy trilogy that had been touted as the successor to Rings. The Golden Compass was financed in the same way, with special rights pre-sold to foreign distributors, many of them the same ones that had handled Rings. The problem was that Compass did tepid business in the U.S. but was a distinct success abroad. That money stayed with the foreign distributors.

Absorbed into Warner Bros.

The Compass problem coincided with the promotion of Jeff Bewkes as CEO of Time Warner at a time when the conglomerate’s stock price was low. The real problem was the encumbrance of AOL, but that was a problem that would take time to solve. New Line’s lack of success with its big Christmas release made it a target. Bewkes could slash the company as a signal to stockholders that he would streamline Time Warner. On February 25, he announced that New Line would be folded into Time Warner, to become a production unit specializing in the sort of genre fare that had sustained New Line for so long, such as the Nightmare on Elm Street series. It would also continue to produce the occasional major film, such as The Hobbit.

The point of absorbing New Line into Warner Bros. was largely to downsize the former by eliminating its distribution and other departments that could be handled by Warners. With Warners distributing New Line films abroad, the income would return to the studio rather than remaining with foreign distributors. Receiving financing from Warners, New Line would no longer need to finance films through presales.

For Time Warner, this made sense, but it was a blow to the overseas distributors with regular output deals with New Line. New Line and Miramax had provided steady product to these companies, which otherwise would have to compete in the open market on a film-by-film basis. With the departure of the Weinstein brothers from Miramax, that firm had dried up as a source, leaving the burden on New Line. Now New Line was disappearing as well.

What now?

In the 7 March 2008 issue of Screen International (the online version is subscription only), Mike Goodridge discussed where these distributors might be able to turn after the expiration of their New Line contracts. He pointed out, “The distribution partners had good years and bad with New Line. None were thrilled with The Long Kiss Goodnight or The Island Of Dr. Moreau but for every flop, there was a Seven or Austin Powers, a Mask or Rush Hour.” He also confirms my claims about the Rings trilogy’s impact on its international distributors: “The success of the three films for the international partners cannot be overestimated. Nor can the fact that they, more than anybody involved, took a huge risk on the trilogy. The risk paid off. The Greens at Entertainment [the U.K. distributor], the Hadidas at Metropolitan [the French distributor] and others genuinely shared in the profits of one of the box-office phenomenons of the last 20 years. It was the international buyers’ dream. Instead of losing money on studio cast-offs, they had a hefty piece of a trilogy which grossed nearly $2bn outside North America.” New Line’s disappearance as a source of hit films “brings a dramatic sea change to the complexion of the global business,” according to Goodridge. These independent firms “will be competing for an increasingly small number of tentpole pictures available to them.”

Where have these distributors turned for films? In some cases their contracts with New Line, which predate the studio’s absorption into Warner Bros., are good through 2009. That means, however, that those distributors are already looking ahead for releases after the contracts end. At Cannes this year, New Line had a much-reduced presence. Camela Galano, one of the executives who had been in the studio’s international sales wing for years, was promoted to being its president in May. She brought only Journey to the Center of the Earth. Galano told Variety, “We just won’t be selling movies … but we’ll be doing what we normally do with our outputs, which is go through the lineup, releases and materials.”

A number of firms at Cannes stepped up to fill in the void left by New Line’s withdrawal from distribution. One up-and-coming firm, QED, was selling Oliver Stone’s W, the sci-fi film District 9 (produced by Peter Jackson and due out in the U.S. next August 14), and the Milla Jovovich thriller A Perfect Getaway. Gary Michael Walters, co-president of Bold Films, commented that he saw an opportunity presented by Warners’ takeover of New Line’s foreign distribution. “We see a sweet spot in that niche of $10 million-$30 million smart but commercial pictures.” Similar rising firms include IM Global, formed by the former head of Miramax International, Stuart Ford. (See Variety‘s summary here.)

John Hazleton analyzed the impact of New Line’s withdrawal from the international market for Screen International just before Cannes (May 9, 2008 issue). Hazleton harks back to the impact of Rings and other New Line franchises:

Many sales executives, in fact, go further and suggest that by boosting the fortunes of the distributor partners with which it had ongoing output or package deals—companies including the UK’s Entertainment, France’s Metropolitan, Australia’s Villege Roadshow and Spain’s Tri Pictures—New Line effectively elevated the independent international industry as a whole. Other sellers benefited, for example, when the New Line distributors reinvested profits from The Lord of the Rings and Rush Hour movies—or from last Christmas’ The Golden Compass—in the acquisition of non-New Line films.

No wonder, then, [that] the decision by parent Warner Bros to turn New Line into a stripped-down genre label whose films will (once current deals expire) be distributed worldwide by the studio is having such an impact in the independent arena. Filling the New Line void has suddenly become a pressing need, or an enticing opportunity, for all sorts of independent players.

One such player is Hyde Park International, whose president Lisa Wilson told Hazleton, “We’re certainly seeing an uptick in interest from distributors who previously didn’t need as much product because they were secure in having the New Line output. They’ve been making more of an effort than usual to meet us before Cannes.” Another is The Film Department, selling two films under production, Law Abiding Citizen, a thriller starring Gerard Butler, and The Rebound, a Catherine Zeta-Jones vehicle.

Hazleton identifies two major independent films suppliers that are stepping into the supply gap left by New Line’s departure:

Leading the field of remaining big picture suppliers are Summit Entertainment and the combination of Lionsgate and Mandate formed when the former acquired the latter last September. Crucially, like New Line, each group now has its own North American theatrical distribution operation, giving international buyers assurance that films will get a domestic theatrical launch and allowing the co-ordination of domestic and international release dates.

Summit is new to the domestic distribution business. But it is a company with vast international experience that plans to handle 10-12 films in the $15m-$45m budget range a year. Its Cannes slate includes Terrence Malick’s drama Tree of Life, starring Brad Pitt, and it already has output deals for its own productions in France, Germany, UK and Scandinavia.

In Lionsgate, Mandate has a well-proven domestic distribution outlet that last year scored three $50m-plus box-office hits and this year has a bigger market share than any independent or studio specialty division.

As the combination’s international arm, Mandate—which will be in Cannes with titles including Whip It! featuring rising star Ellen Page, and family animation Alpha And Omega—handles around half of Lionsgate’s domestic slate plus titles from third-party producers.

New Line’s withdrawal, says Helen Lee Kim, president of Mandate International, “just puts us in a better situation, because you can count on one hand the independent companies able to bring studio-level product to the marketplace.”

Hazleton also points out that “Studio-owned sales operations Paramount Vantage and Focus Films International [a Universal subsidiary] will be another alternative source for buyers.” In general, though, the Hollywood studios’ recent retreat from art-house divisions means that they will have less to contribute to foreign distributors.

Summit and Mandate are both participating in the AFM as well. Another major firm is Relativity Media, a rapidly expanding production-distribution independent responsible for such recent films as 3:10 to Yuma, Atonement, Baby Mama, and Pineapple Express. Relativity had expanded into international sales this year at Cannes. In October it offered $150 million for Universal’s Rogue Pictures and will gain the 40-50 projects that genre division has in the works. As the AFM began, it had just signed long-term output contracts with nine foreign distributors. Finally, Relativity has, according to Variety, “partnered with sales company Mandate Intl. to oversee sales in non-output territories as well as provide worldwide servicing of the slate.”

Other sales firms at Cannes included Odd Lot and Essential, and new companies debuting at the AFM this year were FilmNation, Exclusive Film Distribution, Icon Entertainment, and WestEnd Films. Some of these companies will grow, others won’t. But gradually they will absorb the market position formerly held by New Line.

So does all this mean that the impact of New Line’s glory days is over? Not entirely. I believe that although the distribution of The Lord of the Rings has receded five years into the past and New Line has now disappeared as an independent entity, the trilogy’s impact still lingers in the international industry. Steve Bickel, president of The Film Department, commented to Screen International shortly before Cannes, “The loss of any independent or independent-spirited company is a loss to the industry. New Line provided a great service to all of us because they helped make strong companies that we’re now able to sell to.”

Superheroes for sale

DB here:

After a day at the movies, maybe I am living in a parallel universe. I go to see two films praised by people whose tastes I respect. I find myself bored and depressed. I’m also asking questions.

Over the twenty years since Batman (1989), and especially in the last decade or so, some tentpole pictures, and many movies at lower budget levels, have featured superheroes from the Golden and Silver age of comic books. By my count, since 2002, there have been between three and seven comic-book superhero movies released every year. (I’m not counting other movies derived from comic books or characters, like Richie Rich or Ghost World.)

Until quite recently, superheroes haven’t been the biggest money-spinners. Only eleven of the top 100 films on Box Office Mojo’s current worldwide-grosser list are derived from comics, and none ranks in the top ten titles. But things are changing. For nearly every year since 2000, at least one title has made it into the list of top twenty worldwide grossers. For most years two titles have cracked this list, and in 2007 there were three. This year three films have already arrived in the global top twenty: The Dark Knight, Iron Man, and The Incredible Hulk (four, if you count Wanted as a superhero movie).

This 2008 successes have vindicated Marvel’s long-term strategy to invest directly in movies and have spurred Warners to slate more comic-book titles. David S. Cohen analyses this new market here. So we are clearly in the midst of a Trend. My trip to the multiplex got me asking: What has enabled superhero comic-book movies to blast into a central spot in today’s blockbuster economy?

Enter the comic-book guys

It’s clearly not due to a boom in comic-book reading. Superhero books have not commanded a wide audience for a long time. Statistics on comic-book readership are closely guarded, but the expert commentator John Jackson Miller reports that back in 1959, at least 26 million comic books were sold every month. In the highest month of 2006, comic shops ordered, by Miller’s estimate, about 8 million books (and this total includes not only periodical comics but graphic novels, independent comics, and non-superhero titles). There have been upticks and downturns over the decades, but the overall pattern is a steep slump.

Try to buy an old-fashioned comic book, with staples and floppy covers, and you’ll have to look hard. You can get albums and graphic novels at the chain stores like Borders, but not the monthly periodicals. For those you have to go to a comics shop, and Hank Luttrell, one of my local purveyors of comics, estimates there aren’t more than 1000 of them in the U. S.

Moreover, there’s still a stigma attached to reading superhero comics. Even kitsch novels have long had a slightly higher cultural standing than comic books. Admitting you had read The Devil Wears Prada would be less embarrassing than admitting you read Daredevil.

For such reasons and others, the audience for superhero comics is far smaller than the audience for superhero movies. The movies seem to float pretty free of their origins; you can imagine a young Spider-Man fan who loved the series but never knew the books. What’s going on?

Men in tights, and iron pants

The films that disappointed me on that moviegoing day were Iron Man and The Dark Knight. The first seemed to me an ordinary comic-book movie endowed with verve by Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. While he’s thought of as a versatile actor, Downey also has a star persona—the guy who’s wound a few turns too tight, putting up a good front with rapid-fire patter (see Home for the Holidays, Wonder Boys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Zodiac). Downey’s cynical chatterbox makes Iron Man watchable. When he’s not onscreen we get excelsior.

Christopher Nolan showed himself a clever director in Memento and a promising one in The Prestige. So how did he manage to make The Dark Knight such a portentously hollow movie? Apart from enjoying seeing Hong Kong in Imax, I was struck by the repetition of gimmicky situations–disguises, hostage-taking, ticking bombs, characters dangling over a skyscraper abyss, who’s dead really once and for all? The fights and chases were as unintelligible as most such sequences are nowadays, and the usual roaming-camera formulas were applied without much variety. Shoot lots of singles, track slowly in on everybody who’s speaking, spin a circle around characters now and then, and transition to a new scene with a quick airborne shot of a cityscape. Like Jim Emerson, I thought that everything hurtled along at the same aggressive pace. If I want an arch-criminal caper aiming for shock, emotional distress, and political comment, I’ll take Benny Chan’s New Police Story.

Then there are the mouths. This is a movie about mouths. I couldn’t stop staring at them. Given Batman’s cowl and his husky whisper, you practically have to lip-read his lines. Harvey Dent’s vagrant facial parts are especially engaging around the jaws, and of course the Joker’s double rictus dominates his face. Gradually I found Maggie Gyllenhaal’s spoonbill lips starting to look peculiar.

The expository scenes were played with a somber knowingness I found stifling. Quoting lame dialogue is one of the handiest weapons in a critic’s arsenal and I usually don’t resort to it; many very good movies are weak on this front. Still, I can’t resist feeling that some weighty lines were doing duty for extended dramatic development, trying to convince me that enormous issues were churning underneath all the heists, fights, and chases. Know your limits, Master Wayne. Or: Some men just want to watch the world burn. Or: In their last moments people show you who they really are. Or: The night is darkest before the dawn.

I want to ask: Why so serious?

Odds are you think better of Iron Man and The Dark Knight than I do. That debate will go on for years. My purpose here is to explore a historical question: Why comic-book superhero movies now?

Z as in Zeitgeist

More superhero movies after 2002, you say? Obviously 9/11 so traumatized us that we feel a yearning for superheroes to protect us. Our old friend the zeitgeist furnishes an explanation. Every popular movie can be read as taking the pulse of the public mood or the national unconscious.

I’ve argued against zeitgeist readings in Poetics of Cinema, so I’ll just mention some problems with them:

*A zeitgeist is hard to pin down. There’s no reason to think that the millions of people who go to the movies share the same values, attitudes, moods, or opinions. In fact, all the measures we have of these things show that people differ greatly along all these dimensions. I suspect that the main reason we think there’s a zeitgeist is that we can find it in popular culture. But we would need to find it independently, in our everyday lives, to show that popular culture reflects it.

*So many different movies are popular at any moment that we’d have to posit a pretty fragmented national psyche. Right now, it seems, we affirm heroic achievement (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Kung Fu Panda, Prince Caspian) except when we don’t (Get Smart, The Dark Knight). So maybe the zeitgeist is somehow split? That leads to vacuity, since that answer can accommodate an indefinitely large number of movies. (We’d have to add fractions of our psyche that are solicited by Sex and the City and Horton Hears a Who!)

*The movie audience isn’t a good cross-section of the general public. The demographic profile tilts very young and moderately affluent. Movies are largely a middle-class teenage and twentysomething form. When a producer says her movie is trying to catch the zeitgeist, she’s not tracking retired guys in Arizona wearing white belts; she’s thinking mostly of the tastes of kids in baseball caps and draggy jeans.

* Just because a movie is popular doesn’t mean that people have found the same meanings in it that critics do. Interpretation is a matter of constructing meaning out of what a movie puts before us, not finding the buried treasure, and there’s no guarantee that the critic’s construal conforms to any audience member’s.

*Critics tend to think that if a movie is popular, it reflects the populace. But a ticket is not a vote for the movie’s values. I may like or dislike it, and I may do either for reasons that have nothing to do with its projection of my hidden anxieties.

*Many Hollywood films are popular abroad, in nations presumably possessing a different zeitgeist or national unconscious. How can that work? Or do audiences on different continents share the same zeitgeist?

Wait, somebody will reply, The Dark Knight is a special case! Nolan and his collaborators have strewn the film with references to post-9/11 policies about torture and surveillance. What, though, is the film saying about those policies? The blogosphere is already ablaze with discussions of whether the film supports or criticizes Bush’s White House. And the Editorial Board of the good, gray Times has noticed:

It does not take a lot of imagination to see the new Batman movie that is setting box office records, The Dark Knight, as something of a commentary on the war on terror.

You said it! Takes no imagination at all. But what is the commentary? The Board decides that the water is murky, that some elements of the movie line up on one side, some on the other. The result: “Societies get the heroes they deserve,” which is virtually a line from the movie.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). That’s the bait the Times writers took.

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Back to basics

If the zeitgeist doesn’t explain the flourishing of the superhero movie in the last few years, what does? I offer some suggestions. They’re based on my hunch that the genre has brought together several trends in contemporary Hollywood film. These trends, which can commingle, were around before 2000, but they seem to be developing in a way that has created a niche for the superhero film.

The changing hierarchy of genres. Not all genres are created equal, and they rise or fall in status. As the Western and the musical fell in the 1970s, the urban crime film, horror, and science-fiction rose. For a long time, it would be unthinkable for an A-list director to do a horror or science-fiction movie, but that changed after Polanski, Kubrick, Ridley Scott, et al. gave those genres a fresh luster just by their participation. More recently, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It, the fantasy film arrived as a respectable genre, as measured by box-office receipts, critical respect, and awards. It seems that the sword-and-sorcery movie reached its full rehabilitation when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King scored its eleven Academy Awards.

The comic-book movie has had a longer slog from the B- and sub-B-regions. Superman, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy were all fodder for serials and low-budget fare. Prince Valiant (1954) was the only comics-derived movie of any standing in the 1950s, as I recall, and you can argue that it fitted into a cycle of widescreen costume pictures. (Though it looks like a pretty camp undertaking today.) Much later came revivals of the two most popular superheroes, Superman (1978) and Batman (1989).

The success of the Batman film, which was carefully orchestrated by Warners and its DC comics subsidiary, can be seen as preparing the grounds for today’s superhero franchises. The idea was to avoid simply reiterating a series, as the Superman movie did, or mocking it, as the Batman TV show did. The purpose was to “reimagine” the series, to “reboot” it as we now say, the way Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns re-launched the Batman comic. Rebooting modernizes the mythos by reinterpreting it in a thematically serious and graphically daring way.

During the 1990s, less famous superheroes filled in as the Batman franchise tailed off. Examples were The Rocketeer (1991), Timecop (1994), The Crow (1994) and The Crow: City of Angels (1996), Judge Dredd (1995), Men in Black (1997), Spawn (1997), Blade (1998), and Mystery Men (1999). Most of these managed to fuse their appeals with those of another parvenu genre, the kinetic action-adventure movie.

Significantly, these were typically medium-budget films from semi-independent companies. Although some failed, a few were huge and many earned well, especially once home video was reckoned in. Moreover, the growing number of titles, sometimes featuring name actors, fueled a sense that this genre was becoming important. As often happens, marginal companies developed the market more nimbly than the big ones, who tend to move in once the market has matured.

I’d also suggest that The Matrix (1999) helped legitimize the cycle. (Neo isn’t a superhero? In the final scene he can fly.) The pseudophilosophical aura this movie radiated, as well as its easy familiarity with comics, videogames, and the Web, made it irrevocably cool. Now ambitious young directors like Nolan, Singer, and Brett Ratner could sign such projects with no sense they were going downmarket.

The importance of special effects. Arguably there were no fundamental breakthroughs in special-effects technology from the 1940s to the 1960s. But with motion-control cinematography, showcased in the first Star Wars installment (1977) filmmakers could create a new level of realism in the use of miniatures. Later developments in matte work, blue- and green-screen techniques, and digital imagery were suited to, and driven by, the other genres that were on the rise—horror, science-fiction, and fantasy—but comic-book movies benefited as well. The tagline for Superman was “You’ll believe a man can fly.”

Special effects thereby became one of a film’s attractions. Instead of hiding the technique, films flaunted it as a mark of big budgets and technological sophistication. The fantastic powers of superheroes cried out for CGI, and it may be that convincing movies in the genre weren’t really ready until the software matured.

The rise of franchises. Studios have always sought predictability, and the classic studio system relied on stars and genres to encourage the audience to return for more of what it liked. But as film attendance waned, producers looked for other models. One that was successful was the branded series, epitomized in the James Bond films. With the rise of the summer blockbuster, producers searched for properties that could be exploited in a string of movies. A memorable character could tie the installments together, and so filmmakers turned to pop literature (e.g., the Harry Potter books) and comic books. Today, Marvel Enterprises is less concerned with publishing comics than with creating film vehicles for its 5000 characters. Indeed, to get bank financing it put up ten of its characters as collateral!

Yet a single character might not sustain a robust franchise. Henry Jenkins has written about how popular culture is gravitating to multi-character “worlds” that allow different media texts to be carved out of them. Now that periodical sales of comics have flagged, the tail is wagging the dog. The 5000 characters in the Marvel Universe furnish endless franchise opportunities. If you stayed for the credit cookie at the end of Iron Man, you saw the setup for a sequel that will pair the hero with at least one more Marvel protagonist.

Merchandising and corporate synergy. It’s too obvious to dwell on, but superhero movies fit neatly into the demand that franchises should spawn books, TV shows, soundtracks, toys, apparel, and so on. Time Warner’s acquisition of DC Comics was crucial to the cross-platform marketing of the first Batman. Moreover, most comics readers are relatively affluent (a big change from my boyhood), so they have the income to buy action figures and other pricy collectibles, like a Batbed.

The shift from an auteur cinema to a genre cinema. The classic studio system maintained a fruitful, sometimes tense, balance between directorial expression and genre demands. Somewhere in recent decades that balance has split into polarities. We now have big-budget genre films that made by directors of no discernible individuality, and small “personal” films that showcase the director’s sensibility. There have always been impersonal craftsmen in Hollywood, but the most distinctive directors could often bring their own sensibilities to projects big or small.

David Lynch could make Dune (1984) part of his own oeuvre, but since then we have many big-budget genre pictures that bear no signs of directorial individuality. In particular, science-fiction, fantasy, and superhero movies demand so much high-tech input, so much preparation, so many logistical tasks in shooting, and such intensive postproduction, that economy of effort favors a standardized look and feel. Hence perhaps the recourse to well-established techniques of shooting and cutting; intensified continuity provides a line of least resistance. A comic-book movie can succeed if it doesn’t stray from the fanbase’s expectations and swiftly initiates the newbies. Not much directorial finesse is needed, as 300 (2007) shows.

The development of the megapicture may have led the more talented directors to the “one for them, one for me” motto. Think of the difference between Burton’s Planet of the Apes or even Sweeney Todd and, say, Ed Wood or Big Fish. Or think of the moments of elegance in Memento and The Prestige, as opposed to the blunt handling of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Too much is never enough. Since the 1980s, mass-audience pictures have gravitated toward ever more exaggerated presentation of momentary effects. In a comedy, if a car is about to crash, everyone inside must stare at the camera and shriek in concert. Extreme wide-angle shooting makes faces funny in themselves (or so Barry Sonnenfeld thinks). Action movies shift from slo-mo to fast-mo to reverse-mo, all stitched together by ramping, because somebody thinks these devices make for eye candy. Steep high and low angles, familiar in 1940s noir films, were picked up in comics, which in turn re-influenced movies.

Movies now love to make everything airborne, even the penny in Ghost. Things fly out at us, and thanks to surround channels we can hear them after they pass. It’s not enough simply to fire an arrow or bullet; the camera has to ride the projectile to its destination—or, in Wanted, from its target back to its source. In 21 of earlier this year, blackjack is given a monumentality more appropriate to buildings slated for demolition: giant playing cards whoosh like Stealth fighters or topple like brick walls.

I’m not against such one-off bursts of imagery. There’s an undoubted wow factor in seeing spent bullet casings shower into our face in The Matrix.

I just ask: What do such images remind us of? My answer: Comic book panels, those graphically dynamic compositions that keep us turning the pages. In fact, we call such effects “cartoonish.” Here’s an example from Watchmen, where the slow-motion effect of the Smiley pin floating down toward us is sustained by a series of lines of dialogue from the funeral service.

With comic-book imagery showing up in non-comic-book movies, one source may be greater reliance on storyboards and animatics. Spfx demand intensive planning, so detailed storyboarding was a necessity. Once you’re planning shot by shot, why not create very fancy compositions in previsualization? Spielberg seems to me the live-action master of “storyboard cinema.” And of course storyboards look like comic-book pages.

The hambone factor. In the studio era, star acting ruled. A star carried her or his persona (literally, mask) from project to project. Parker Tyler once compared Hollywood star acting to a charade; we always recognized the person underneath the mime.

This is not to say that the stars were mannequins or dead meat. Rather, like a sculptor who reshapes a piece of wood, a star remolded the persona to the project. Cary Grant was always Cary Grant, with that implausible accent, but the Cary Grant of Only Angels Have Wings is not that of His Girl Friday or Suspicion or Notorious or Arsenic and Old Lace. Or compare Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve, Double Indemnity, and Meet John Doe. Young Mr. Lincoln is not the same character as Mr. Roberts, but both are recognizably Henry Fonda.

Dress them up as you like, but their bearing and especially their voices would always betray them. As Mr. Kralik in The Shop around the Corner, James Stewart talks like Mr. Smith on his way to Washington. In The Little Foxes, Herbert Marshall and Bette Davis sound about as southern as I do.

Star acting persisted into the 1960s, with Fonda, Stewart, Wayne, Crawford, and other granitic survivors of the studio era finishing out their careers. Star acting continues in what scholar Steve Seidman has called “comedian comedy,” from Jerry Lewis to Adam Sandler and Jack Black. Their characters are usually the same guy, again. Arguably some women, like Sandra Bullock and Ashlee Judd, also continued the tradition.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

Horror and comic-book movies offer ripe opportunities for this sort of masquerade. In a straight drama, confined by realism, you usually can’t go over the top, but given the role of Hannibal Lector, there is no top. The awesome villain is a playground for the virtuoso, or the virtuoso in training. You can overplay, underplay, or over-underplay. You can also shift registers with no warning, as when hambone supreme Orson Welles would switch from a whisper to a bellow. More often now we get the flip from menace to gargoylish humor. Jack Nicholson’s “Heeere’s Johnny” in The Shining is iconic in this respect. In classic Hollywood, humor was used to strengthen sentiment, but now it’s used to dilute violence.

Such is the range we find in The Dark Knight. True, some players turn in fairly low-key work. Morgan Freeman plays Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine does his usual punctilious job, and Gary Oldman seems to have stumbled in from an ordinary crime film. Maggie Gylenhaal and Aaron Eckhart provide a degree of normality by only slightly overplaying; even after Harvey Dent’s fiery makeover Eckhart treats the role as no occasion for theatrics.

All else is Guignol. The Joker’s darting eyes, waggling brows, chortles, and restless licking of his lips send every bit of dialogue Special Delivery. Ledger’s performance has been much praised, but what would count as a bad line reading here? The part seems designed for scenery-chewing. By contrast, poor Bale has little to work with. As Bruce Wayne, he must be stiff as a plank, kissing Rachel while keeping one hand suavely tucked in his pocket, GQ style. In his Bat-cowl, he’s missing as much acreage of his face as Dent is, so all Bale has is the voice, over-underplayed as a hoarse bark.

In sum, our principals are sweating through their scenes. You get no strokes for making it look easy, but if you work really hard you might get an Oscar.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

But of course the caricaturists got here first, from Hogarth and Daumier onward. Most memorably, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy strip offered a parade of mutilated villains like Flattop, the Brow, the Mole, and the Blank, a gentleman who was literally defaced. The Batman comics followed Gould in giving the protagonist an array of adversaries who would even raise an eyebrow in a Manhattan subway car.

Eisenstein once argued that horrific grotesquerie was unstable and hard to sustain. He thought that it teetered between the comic-grotesque and the pathetic-grotesque. That’s the difference, I suppose, between Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands, or between the Joker and Harvey Dent. In any case, in all its guises the grotesque is available to our comic-book pictures, and it plays nicely into the oversize acting style that’s coming into favor.

You’re thinking that I’ve gone on way too long, and you’re right. Yet I can’t withhold two more quickies:

The global recognition of anime and Hong Kong swordplay films. During the climactic battle between Iron Man 2.0 and 3.0, so reminiscent of Transformers, I thought: “The mecha look has won.”

Learning to love the dark. That is, filmmakers’ current belief that “dark” themes, carried by monochrome cinematography, somehow carry more prestige than light ones in a wide palette. This parallels comics’ urge for legitimacy by treating serious subjects in somber hues, especially in graphic novels.

Time to stop! This is, after all, just a list of causes and conditions that occurred to me after my day in the multiplex. I’m sure we can find others. Still, factors like these seem to me more precise and proximate causes for the surge in comic-book films than a vague sense that we need these heroes now. These heroes have been around for fifty years, so in some sense they’ve always been needed, and somebody may still need them. The major media companies, for sure. Gazillions of fans, apparently. Me, not so much. But after Hellboy II: The Golden Army I live in hope.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell for information about the history of the comics market.

The superhero rankings I mentioned are: Spider-Man 3 (no. 12), Spider-Man (no. 17), Spider-Man 2 (no. 23), The Dark Knight (currently at no. 29, but that will change), Men in Black (no. 42), Iron Man (no. 45), X-Men: The Last Stand (no. 75), 300 (no. 80), Men in Black II (no. 85), Batman (no. 95), and X2: X-Men United (no. 98). The usual caveat applies: This list is based on unadjusted grosses and so favors recent titles, because of inflation and the increased ticket prices. If you adjust for these factors, the list of 100 all-time top grossers includes seven comics titles, with the highest-ranking one being Spider-Man, at no. 33.

For a thoughtful essay written just as the trend was starting, see Ken Tucker’s 2000 Entertainment Weekly piece, “Caped Fears.” It’s incompletely available here.

Comics aficionados may object that I am obviously against comics as a whole. True, I have little interest in superhero comic books. As a boy I read the DC titles, but I preferred Mad, Archie, Uncle Scrooge, and Little Lulu. In high school and college I missed the whole Marvel revolution and never caught up. Like everybody else in the 1980s I read The Dark Knight Returns, but I preferred Watchmen (and I look forward to the movie). I like the Hellboy movies too. But I’m not gripped by many of the newest trends in comics. Sin City strikes me as a fastidious piece of draftsmanship exercised on formulaic material, as if Mickey Spillane were rewritten by Nicholson Baker. Since the 80s my tastes have run to Ware, Clowes, a few manga, and especially Eurocomics derived from the clear-line tradition (Chaland, Floc’h, Swarte, etc.). I believe that McCay and Herriman are major twentieth-century artists, with Chester Gould and Cliff Sterrett worth considering for the honor too.

You can argue that Oliver Stone’s films create ambivalence inadvertently. JFK seems to have a clear-cut message, but the plotting is diverted by so many conspiracy scenarios that the viewer might get confused about what exactly Stone is claiming really happened.

On the ways that worldmaking replaces character-centered media storytelling, the crucial discussion is in Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York University Press, 2007), 113-122.

On franchise-building, see the detailed account in detail in Eileen R. Meehan, “‘Holy Commodity Fetish, Batman!’: The Political Economy of a Commercial Intertext,” in The Many Lives of the Batman, ed. Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (Routledge, 1991), 47-65. Other essays in this collection offer information on the strategies of franchise-building.

Just as Star Wars helped legitimate itself by including Alec Guinness in its cast (surely he wouldn’t be in a potboiler), several superhero movies have a proclivity for including a touch of British class: McKellan and Stewart in X-Men, Caine in the Batman series. These old reliables like to keep busy and earn a spot of cash.

PS: 21 August 2008: This post has gotten some intriguing responses, both on the Internets and in correspondence with me, so I’m adding a few here.

Jim Emerson elaborated on the zeitgeist motif in an entry at Scanners. At Crooked Timber, John Holbo examines how much the film’s dark cast owes to the 1990s reincarnation of Batman. Peter Coogan writes to tell me that he makes a narrower version of the zeitgeist argument in relation to superheroes in Chapter 10 of his book, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, to be reprinted next year. Even the more moderate form he proposes doesn’t convince me, I’m afraid, but the book ought to be of value to readers interested in the genre.

From Stew Fyfe comes a letter offering some corrections and qualifications.

*Stew points out that chain stores like Borders do sell some periodical comics titles, though not always regularly.

*Comics publishing, while not at the circulation levels seen in the golden era, is undergoing something of a resurgence now, possibly because of the success of the franchise movies. Watchmen sales alone will be a big bump in anticipation of the movie.

*As for my claim that film is driving the publishing side, Stew suggests that the relations between the media are more complicated. The idea that the tail wags the dog might apply to DC, but Marvel has made efforts to diversify the relations between the books and the films.

They’ve done things like replacing the Hulk with a red, articulate version of the character just before the movie came out (which is odd because if there’s one thing that the general public knows about the character is that he’s green and he grunts). They’ve also handed the Hulk’s main title over to a minor character, Hercules. They’ve spent a year turning Iron Man, in the main continuity, into something of a techno-fascist (if lately a repentant one) who locks up other superheroes.

Stew speculates that Marvel is trying to multiply its audiences. It relies on its main “continuity books” to serve the fanbase who patronizes the shops, and the films sustain each title’s proprietary look and feel. In addition, some of the books offer fresh material for anyone who might want to buy the comic after seeing the film; this tactic includes reprinted material and rebooted continuity lines in the Ultimate series. Marvel has also brought in film and TV creators as writers (Joss Whedon, Kevin Smith), while occasionally comics artists work in TV shows like Heroes, Lost, and Battlestar Galactica. So the connections are more complex than I was indicating.

Thanks to all these readers for their comments.

Legacies

DB here:

By now James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma has had its critics’ screenings and sneak previews. It’s due to open this weekend. The reviews are already in, and they’re very admiring.

Back in June, I saw an early version as a guest of the filmmaker and I visited a mixing session, which I chronicled in another entry. I was reluctant to write about the film in the sort of detail I like, because I wasn’t seeing the absolutely final version and because it would involve giving away a lot of the plot.

I still won’t offer you an orthodox review of the film, which I look forward to seeing this weekend in its final theatrical form. Instead, I’ll use the film’s release as an occasion to reflect on Mangold’s work, on his approach to filmmaking, and on some general issues about contemporary Hollywood.

An intimidating legacy

It seems to me that one problem facing contemporary American filmmakers is their overwhelming awareness of the legacy of the classic studio era. They suffer from belatedness. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that this is a relatively recent development, and it offers an important clue to why today’s ambitious US cinema looks and sounds as it does.

In the classic years, there was asymmetrical information among film professionals. Filmmakers outside the US were very aware of Hollywood cinema because of the industry’s global reach. French and German filmmakers could easily watch what American cinema was up to. Soviet filmmakers studied Hollywood imports, as did Japanese directors and screenwriters. Ozu knew the work of Chaplin, Lubitsch, and Lloyd, and he greatly admired John Ford. But US filmmakers were largely ignorant of or indifferent to foreign cinemas. True, a handful of influential films like Variety (1925) and Potemkin (1925) made an impact on Hollywood, but with the coming of sound and World War II, Hollywood filmmakers were cut off from foreign influences almost completely. I doubt that Lubitsch or Ford ever heard of Ozu.

Moreover, US directors didn’t have access to their own tradition. Before television and video, it was very difficult to see old American films anywhere. A few revival houses might play older titles, but even the Museum of Modern Art didn’t afford aspiring film directors a chance to immerse themselves in the Hollywood tradition. Orson Welles was considered unusual when he prepared for Citizen Kane by studying Stagecoach. Did Ford or Curtiz or Minnelli even rewatch their own films?

With no broad or consistent access to their own film heritage, American directors from the 1920s to the 1960s relied on their ingrained craft habits. What they took from others was so thoroughly assimilated, so deep in their bones, that it posed no problems of rivalry or influence. The homage or pastiche was largely unknown. It took a rare director like Preston Sturges to pay somewhat caustic respects to Hollywood’s past by casting Harold Lloyd in Mad Wednesday (1947), which begins with a clip from The Freshman. (So Soderbergh’s use of Poor Cow in The Limey has at least one predecessor.)

Things changed for directors who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s. Studios sold their back libraries to TV, and so from 1954 on, you could see classics in syndication and network broadcast. New Yorkers could steep themselves in classic films on WOR’s Million-Dollar Movie, which sometimes ran the same title five nights in a row. There were also campus film societies and in the major cities a few repertory cinemas. The Scorsese generation grew up feeding at this banquet table of classic cinema.

In the following years, cable television, videocassettes, and eventually DVDs made even more of the American cinema’s heritage easily available. We take it for granted that we can sit down and gorge ourselves on Astaire-Rogers musicals or B-horror movies whenever we want. Granted, significant areas of film history are still terra incognita, and silent cinema, documentary, and the avant-garde are poorly served on home video. Nonetheless, we can explore Hollywood’s genres, styles, periods, and filmmakers’ work more thoroughly than ever before. Since the 1970s, the young American filmmaker faces a new sort of challenge: Now fully aware of a great tradition, how can one keep from being awed and paralyzed by it? How can a filmmaker do something original?

I don’t suggest that filmmakers have decided their course with cold calculation. More likely, their temperaments and circumstances will spontaneously push them in several different directions. Some directors, notably Peckinpah and Altman, tried to criticize the Hollywood tradition. Most tried simply to sustain it, playing by the rules but updating the look and feel to contemporary tastes. This is what we find in today’s romantic comedy, teenage comedy, horror film, action picture, and other programmers.

More ambitious filmmakers have tried to extend and deepen the tradition. The chief example I offer in The Way is Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire, but this strategy also informs The Godfather, American Graffiti, Jaws, and many other movies we value. I also think that new story formats like network narratives and richly-realized story worlds have become creative extensions of the possibilities latent in classical filmmaking.

James Mangold’s career, from Heavy onward, follows this option, though with little fanfare. He avoids knowingness. He doesn’t fill his movies with in-jokes, citations, or homages. Instead, he shows the continuity between one vein of classical cinema and one strength of indie film by concentrating on character development and nuances of performance. In an industry that demands one-liners and catch-phrases sprinkled through a script, Mangold offers the mature appeal of writing grounded in psychological revelation. In a cinema that valorizes the one-sheet and special effects and directorial flourishes, he begins by collaborating with his actors. He is, we might say, following in the steps of Elia Kazan and George Cukor.

Sandy

By his own account, Mangold awakened to these strengths during his formative years at Cal Arts, where he studied with Alexander Mackendrick. Mackendrick directed some of the best British films of the 1940s and 1950s, but today he is best known for Sweet Smell of Success.

Seeing it again, I was struck by the ways that it looks toward today’s independent cinema. It offers a stinging portrait of what we’d now call infotainment, showing how a venal publicist curries favor with a monstrously powerful gossip columnist. It’s not hard to recognize a Broadway version of our own mediascape, in which Larry King, Oprah, and tmz.com anoint celebrities and publicists besiege them for airtime. While at times the dialogue gets a little didactic (Clifford Odets did the screenplay), the plotting is superb. Across a night, a day, and another night, intricate schemes of humiliation and aggression play out in machine-gun talk and dizzying mind games. It’s like a Ben Jonson play updated to Times Square, where greed and malice have swollen to grandiose proportions, and shysters run their spite and bravado on sheer cutthroat adrenalin.

Sweet Smell was shot in Manhattan, and James Wong Howe innovated with his voluptuous location cinematography. “I love this dirty city,” one character says, and Wong Howe makes us love it too, especially at night.

Today major stars use indie projects to break with their official personas, and the same thing happens in Mackendrick’s film. Burt Lancaster, who had played flawed but honorable heroes, portrayed the columnist J. J. Hunsecker with savage relish. “My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand in thirty years,” he remarks. Tony Curtis, who would go on to become a fine light comedian, plays Sidney Falco as a baby-faced predator, what Hunsecker calls “a cookie full of arsenic.” Falco is sunk in petty corruption, ready to trade his girlfriend’s sexual favors for a notice in a hack’s column. Hunsecker and Falco, host and parasite, dominator and instrument, are inherently at odds, then in a breathtaking scene they double-team to break the will of a decent young couple. There are no heroes. Nor, as Mangold points out in his Afterword to the published screenplay, do we find any of that “redemption” that today’s producers demand in order to brighten a bleak story line.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.