Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

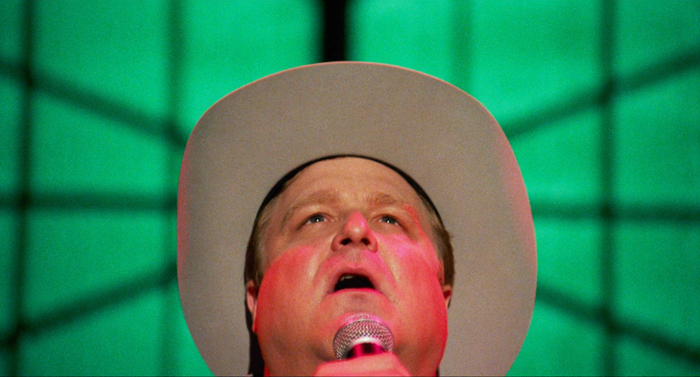

Pockets of Utopia: TRUE STORIES

True Stories (1986).

DB here:

Fall of 1986 saw two helpings of twisty Americana from a pair of Davids. Lynch’s Blue Velvet was released in September, and Byrne’s True Stories followed less than a month later. In a year dominated by the Goliath known as Top Gun, the Davids stood little chance. As of January 1987, Blue Velvet had made $3.5 million domestically, while True Stories, on a budget of $5 million, earned only $1.2 million, less than The Toxic Avenger. But both acquired cult followings, especially on videotape.

Fall of 1986 saw two helpings of twisty Americana from a pair of Davids. Lynch’s Blue Velvet was released in September, and Byrne’s True Stories followed less than a month later. In a year dominated by the Goliath known as Top Gun, the Davids stood little chance. As of January 1987, Blue Velvet had made $3.5 million domestically, while True Stories, on a budget of $5 million, earned only $1.2 million, less than The Toxic Avenger. But both acquired cult followings, especially on videotape.

In the decades since, Blue Velvet has received luxurious DVD and Blu-ray treatment. True Stories, however, wasn’t well-served by Warners’ offhand DVD transfer. Now the Criterion people have given us a lustrous Blu-ray edition of another movie that shows that the 1980s weren’t all big hair, padded shoulders, and John Hughes pity parties. This will quickly become a fetish object for the vast True Stories cult. Visit us way down in the codicil for details.

This movie has been a favorite of mine since I saw it in 1986. Kristin gave me a 16mm print for a long-ago birthday. I’ve wanted to write about it for years, and the Criterion release provides a nifty opportunity. (Full disclosure: I’ve done work for the company. Fuller disclosure: I happily paid for this Blu-ray.)

But I realize that music is so ingredient to the sneaky pleasure of this film that I need expert help. Hence this entry will be followed by one by Jeff Smith. Jeff, as you probably know, is our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our FilmStruck/Criterion series Observations on Film Art, as well as being a frequent contributor to the blog. His deep knowledge of music will yield an entry you’re sure to find interesting.

Many true stories

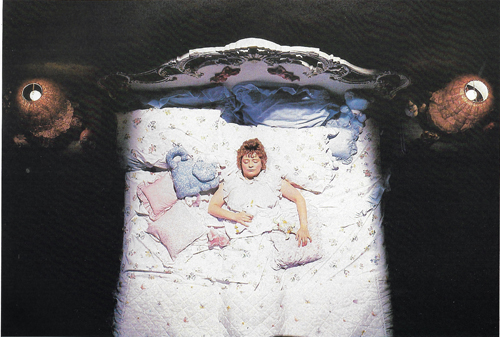

In the film’s publicity Byrne was at pains to claim that he drew the narrative material from tabloid articles he collected over years of touring with Talking Heads. These clippings supply the initial characterization of the lovelorn Louis Fyne, the Lazy Woman lolling in bed, and the Culvers who never speak directly to each other. Other aspects of the film come from fringe culture more generally, like conspiracy theories and extraterrestrial communication. (The Computer Guy sends signals “up”; in a cut scene available on the Criterion release, he’s transmitting New Age music to be picked up by aliens.)

At the end of the published screenplay, Byrne admits that he used these and other faits divers as inspiration more than as well-documented material. Is this stuff true? “I don’t even really care. . . . It seems to give the movie an extra little bit of excitement to think that maybe it could be true.” The dossier he collected includes not just weird anecdotes but articles about prefab architecture, the computer industry, the malling of America, and other social developments. These are just as important “true stories” as any tales from The Weekly World News.

Do all these stories add up to A Story? Sounding a bit like Wim Wenders, Byrne notes: “Movies are a combination of sounds and pictures, and stories are a trick to get you to keep paying attention.” So he began with drawings, which he posted on walls and kept shuffling around. Eventually two screenwriters, Beth Henley and Steven Tobolowsky, pulled a plot out of them, but Byrne went on to fragment that considerably. The result shifts between episodic and classically plotted cinema.

True Stories has a clear time frame: four days, from Wednesday to Saturday night in and around the fictitious town of Virgil, Texas. This period is followed by an indeterminate gap, ending in an epilogue showing a wedding and the Narrator’s departure. The whole tale is framed, beginning and end, by the solfège song of a little girl on the road. Jonathan Demme told Byrne that a movie needs a clock, so the plot creates a soft deadline, the variety show on Saturday.

We get something like a tandem story line. First, there’s Louis Fyne’s quest for a woman to marry. More casually, we explore everyday life among the locals. Mostly these revelations come through the wanderings of the Narrator, a lanky outsider dressed in cowboy clothes nobody else wears and possessed of hesitant curiosity. At times, without his guidance, we get other glimpses of town life, such as the habits of the Lazy Woman and the divination powers of her servant Roberto. There are also some very brief vignettes on the margin. The big show ties up the romance line of action when Louis’s stirring performance of his song, “People Like Us,” rouses the Lazy Woman to propose to him. Despite Byrne’s desire to avoid “too much story,” I think most viewers are grateful for a fairly tidy plot that helps us engage with these offbeat characters.

Our Town (not)

Because of the film tries to survey small-town life, it’s been compared to Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, and it seems that Byrne considered that one model. Still, the differences are pretty important.

Our Town concentrates on two families in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire. People live close together and duck into each other’s kitchens and stop to gossip in front yards. But in Virgil there’s mostly no there there. That town is seen chiefly in empty night vistas, lit by blinking traffic lights. Only the parade seems to energize the fairly sparse main drag.

Virgil is hollowed out; all the big stores relocated to the mall. This is the new Main Street, the Narrator explains, and even the music club sits among boutiques and chain stores. Elsewhere, people’s homes homes squat in splendid isolation, like the Lazy Woman’s mansion, or in half-finished developments pasted against a desolate horizon. People have to reinvent themselves in new spaces, we’re told; the cloistered community of New England hasn’t been rebuilt in the exurbs of the New Southwest.

Hence the importance of driving scenes, of which the film has some of the most beautiful in all of cinema. The Narrator cruises the flat, baked landscape, the sky reflected gorgeously in the sheen of his red convertible. Without a car, you can’t join the community, and the Sesquicentennial Parade boasts its share of customized transport, from the Low Riders to the Red Mustang Shriners.

Our Town builds its action out of work and family routines, ceremonies marking marriage and death. The pathetic fate of Simon Stimson, the church musician, warns of the perils of solitude. The romance of George and Emily shows that marriage at least provides companionship and at most nourishes devotion. Across three days separated by years (and with a flashback to a fourth day), Wilder tries to put this entire mundane rhythm into a cosmic context, a cycle of birth and death that should teach us to appreciate each precious instant of life.

So too, in its way, does True Stories. But here the work routines are post-Fordist: Earl Culver explains that people don’t differentiate between working and not working. He’s thinking of techies like the Computer Guy, who ransacks the mall for equipment to tinker with at home. But the blue-collar employees get into the 24/7 spirit. They make their day on the assembly line as casual as lunchtime, talking about love and money and quirks, even crooning to one another. Louis in the Clean Room can spare a moment for a monologue about his love life. At the bar and the mall, the same workers cross paths. In Greater Virgil, leisure is an extension of the break room.

The only family we see in detail are the Culvers, who under a surface perkiness play out rigid roles (and the parents don’t talk to one another). The Cute Woman and the Lying Woman seem to want more, as both meet Louis on dates, but neither can really break out of her obsession (smiling, lying). Even Louis’s eventual mate, the Lazy Woman, gets out of bed only to phone him. After the wedding he has joined her under the covers, presumably to watch TV forever.

Death haunts Our Town, and the same goes for True Stories in its original form. In the screenplay and footage shot, the Cute Woman dies during the parade (overcome by the sweetness emanating from the babies on display). The film’s final scene would have shown her funeral, where the Narrator shares thoughts with Roberto. Byrne deleted her death and burial as too sad, thereby also losing her melancholy Molly-Bloomish bed monologue. (These scenes are in the supplemental material as analog video; below are production stills.)

In a way, the burial would have rounded things off. While Louis’s quest for a wife is rewarded, the Narrator’s inquiry into Virgil’s not-so-wild life could have ended with his discovery of a death from pathetic obsession. It would have been marked by the Lying Woman’s pointless lie: “She was my best friend. . . . We had so much in common.” The comic grotesque would have become the pathetic grotesque.

Excising this scene leaves a gap. After Louis’s wedding (which the Narrator doesn’t attend), the Narrator is seen simply driving off and reflecting on why he likes to forget. Denying us a farewell between the two characters who have built up a friendship in the course of the film, expelling the foreign visitor back to the road and the horizon, Byrne gives us another flavor of sadness. Their encounter was as transitory as everything else in this post-Our Town landscape. And as we’ll see, the Narrator’s meditation as he drives off carries a burden as important as the postcard addressed to “The Mind of God” in Our Town.

Virgil’s guide

Our Town’s Stage Manager is omniscient. He knows everything about Grover’s Corners, past, present, and future. (He predicts the death dates of some people as he introduces them to us.) He indeed stage-manages the action, calling on experts and even summoning George and Emily to reenact their courtship. Yet although he can interact with characters, he can stand outside the story and address us directly. His presence comes to seem comfortable and reliable. He’s an all-controlling guide—at least until the climax, when Emily takes over the narration and tries to return to the world of the living.

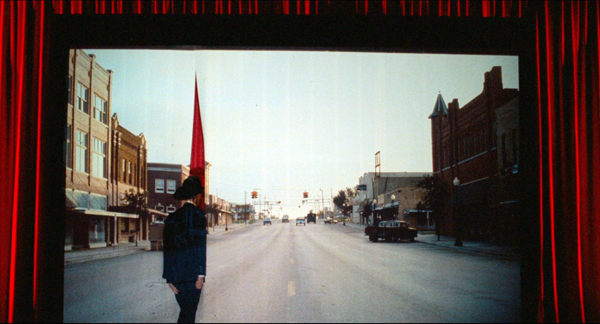

The Narrator of True Stories doesn’t stage-manage anything. He starts out omniscient, lecturing to us about the history of Texas and the occasion for Virgil’s celebration. But once he steps through the slit in the screen, he mostly becomes a naïve, passive presence. He quizzes locals as they deliver monologues, and he seems politely puzzled by their outrageous claims. His dude-ranch getup and geeky silhouette make him almost childlike. He marvels at all the nicknames for highway drivers and is staggered when he sees a four-car garage. (“Who can say it isn’t beautiful?”) The film is almost over when he assures us that this is not a rental car: “This is privately owned.” Who ever thought to ask? And now that you mention it, who does own it?

True, the Narrator issues grown-up pronouncements about the Varicorp chip-assembly plant, but it’s in the bland tones of a PR brochure. He gives us stray factoids like a schoolboy proud of memorization. Even his pronunciation (“special-ness”) suggests either ignorance or awkward efforts to be cute. He might be the incarnation of the voice in one of Byrne’s Knee Plays (“Social Studies”):

I thought that if I ate the food of the area I was visiting

That I might assimilate the point of view of the people there

As if the point of view was somehow in the food….

When shopping at the supermarket

I felt a great desire to walk off with someone else’s groceries

So I could study them at length

And study their effects on me

What sort of narrative authority is this?

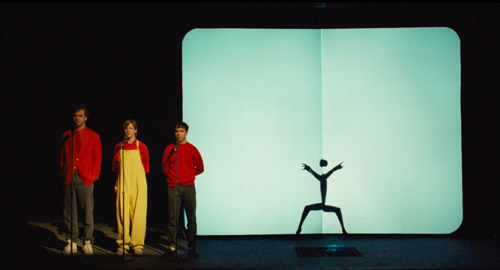

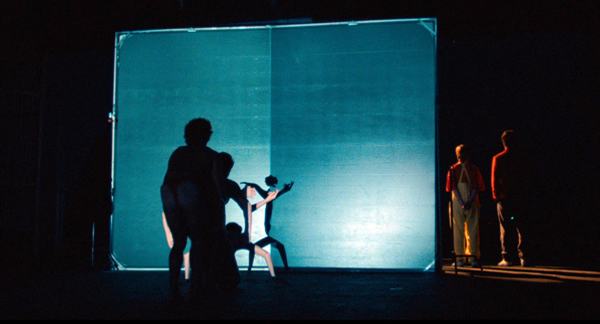

A sort, I think, we find in the calculated vacancy of post-Pop art culture. It’s the blankness of (Texan) Robert Wilson’s po-faced theatre spectacles, where counting off numbers and metronomic gesturing suggest behavior “on the spectrum.” It’s Jeff Koons, maker of gilded Michael Jacksons, saying, “Removing judgments lets you feel, of course, freer, and you have acceptance of things, and everything’s in play, and it lets you go further.” It’s above all Warhol, who perfected affirmative blankness in art and life.

I’m not more intelligent than I appear. . . . The world fascinates me. It’s so nice, whatever it is. I approve of what everybody does.

It’s an artistic strategy that invokes what Viktor Shklovsky called “defamiliarization” and Brecht called “estrangement.” The aim is to make us perceive ordinary life afresh, without the preconceptions we normally bring to it.

For Wilson, repetition and abstraction in the glowing stage box resensitize us to the unique signatures a body traces in space. For Warhol, and his decadent successor Koons, what gets “estranged” is contemporary mass culture, images of Elvis or soup cans or electric chairs or achingly cute balloon bunnies. We’re not far from Romanticism’s cult of the innocent eye, except that we’re not achieving a lyrical insight into nature but rather the thrill of seeing kitsch reveal elusive beauty and unexpected emotion. (I think that this is the point of Tati’s Play Time as well.)

Defamiliarization was of course on Thornton Wilder’s agenda too. Our Town’s bare-bones staging and breaking of the fourth wall aimed at refreshing our perception of stereotypes of rural life. The local-color writers before him had either celebrated small towns (Cather, My Ántonia) or condemned them (Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio), but neither had given them such archetypal poignancy. In Our Town, we might say that Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River gets redeemed by cosmic purpose.

Like others in the New York art scene, what Byrne sought to defamiliarize was American commodity culture. He had done it throughout the Talking Heads’s songbook, but with a sour, somewhat superior tone. That doesn’t entirely vanish here, I think, as in the moments of satire during Earl Culver’s dinnertime monologue, which becomes a pitch for letting a hundred Silicon Valleys bloom.

Such mockery is aimed mainly at corporate culture, while the community as a whole gets treated with a more grave affection. Does the sobriety check in the shadow of a Stop’n’Go (up top of today’s entry) owe something to Robert Wilson’s gestural tableaux? The gravity also stems from the planimetric framings, recalling not only Wilson but Walker Evans too.

These angles defamiliarize the landscape of exurbia, and their slightly comic monumentality will be echoed by Wes Anderson and other filmmakers of the 1990s.

As for the affection: I think the gee-whiz acceptance of commodity culture we find in Warhol and Koons becomes something different in True Stories. The good folk of Grover’s Corners, cradled among kin and friends, don’t need to assert their individuality, but the Virgilians define themselves by comparison shopping—and rebranding. True Stories is in part an appreciation of how people creatively remake all the crap pumped out for them to consume.

Amateur virtuosity

None of them seemed to feel alienated. They seemed to respond to mass culture in a very individual way—like, they take a prefabricated house and do something odd with it on the inside. I guess I was sort of proposing that here are these other possibilities—and maybe it was also a little bit of someone from New York imagining these little pockets of Utopia out there.

Near Spring Green, Wisconsin, sits the House on the Rock, a wondrous homage to the maxim “Too much is never enough.” In one hall a pneumatically controlled orchestra plays while you wander among a brewery, a pipe organ, and display cases, while above you hangs the engine of a whaling ship. With its carousels, dollhouses, Titanic souvenirs, and calliopes, welling out of the darkness in spotlights and glowing primary colors, the House on the Rock shows that if you plunge deeply enough into kitsch you come out the other side with something sublime, or at least surreal.

True Stories is in part about that plunge into tackiness, steered by a very 80s concern with the intersection of high and low. Can you endow kitsch with an avant-garde disorientation? Can you infuse avant-garde art with the good dirty fun of kitsch?

Byrne tries. The fashion show blurs the line between inspired tastelessness (a wedding dress like a wedding cake) and PoMo gallery art, the grass leisurewear provided by Bill Harding of Chicago. In the Criterion Making-of, Byrne insists that Adelle Lutz’s costumes are only one step beyond what you could find in Sears Roebuck of the day.

The Red Mustang Shriners, genuine as can be, constitute straightfaced populist eccentricity in a House-on-the-Rock vein. So do many of the variety acts, such as the Apache Belles and the eerie Shadow Dancers. And Mr. Tucker’s bungalow is actually the home of artist Willard Watson (aka The Texas Kid); footage of his encounter with Pops Staples is featured in the Criterion disc. This is another way the title levels with us: Many of the disconcerting images and sounds we encounter are as true as any story.

Some of the moments present authentic local music, like the accordion number in the Tex-Mex club where Ramon performs. Yet more often Byrne navigates the meeting of high and low in a striking way. While artworld-based Performance Art was going mainstream in the 1980s, Byrne starts from the other end and gives highbrow legitimacy to outsider performance art.

Virgil’s routines and ceremonies become occasions for impromptu performance. Instead of a traditional Happy Hour dance competition, there’s a lip-sync contest (“Wild, Wild Life”), with performers using their body to spin associations off the lyrics. A fashion show gets its own catwalk waltz, and a sermon on conspiracy theories becomes a stomping gospel tune. (It provocatively incorporates video clips assaulting the blue-sky tech promises of Earl Culver and Varicorp.) The Talking Heads music video “Love for Sale” absorbed TV commercials; now the film makes the video part of the flow of ads and programs on the Lazy Woman’s monitor. In Virgil, a parade can be a variety card, and a talent show can be as off-kilter as a string of pieces in a SoHo loft.

Amateurism isn’t necessarily clumsy; it has its own virtuosity. Why shouldn’t auctioneering be a sort of rap? Why shouldn’t children enact a love story with ventriloquist dummies? Why can’t people on the prairie come up with mysterious shadow choreography? At the climax, Louis is able to channel his search for love into a country and western song that he belts out with a confidence we haven’t seen from him before.

“Ideally,” Robert Wilson told an interviewer, “what we’d like to do onstage is to present ourselves.” The songs in True Stories, Byrne said, aimed to

give relatively placid people—like you or me—a justification for being vibrant and full of energy, for expressing themselves and exposing their insides to everyone else in the town.

Yet an audience isn’t necessary. Late at night a businessman dances alone at his office window, and a carpenter takes the empty stage to sing an aria. At the beginning and end, on the endless road, a little girl murmurs a song and makes mesmeric passes at nothing. She expresses herself in a fusion of naïve art and Downtown minimalism: It’s at once childish warbling and a Meredith Monk tune.

Our (favorite) town

That song stands out as a sort of primal beginning of all the film’s performances. It becomes the orchestral underpinning of the Narrator’s introduction to Texas history and his first trip down the expressway. The same spirit emerges in the 4H kids’ spontaneous brick ballet “Hey Now.” Childhood, it seems, is media-free, back to the basics of bodies and castoff noisemakers.

The kids’ direct expression is starkly different from the media-enabled activity we see among the grownups. One character, Ramon, is associated with radio; he thinks that each of us transmits our feelings on wavelengths he can pick up. Naturally, he’s written a song about it. The Lazy Woman, on the other hand, is identified with television, her main contact with the outside world.

Mr. Tucker is an LP aficionado; the Computer Guy works on early digital sound. Documentary film is represented as a collage of Puzzling Evidence. Print media surface as the hectic tabloids read by the teenagers.

The sensational stories in the tabs, the wellspring of Byrne’s film, shape the Lying Woman’s confabulations. Grover’s Corners was never plugged in to the flow of information like this.

All these factors—the mix of avant-garde and down-home artmaking, the nutty byways of populist performance art, people responding to a multimedia environment—heighten the effect of estrangement. The film’s opening montage has an arch knowingness, anachronistically mixing Raquel Welch cheesecake with dinosaur lore. Call it comic defamiliarization. But things grow more sincerely felt as we go along, so that the crazy grotesques of Virgil become not so crazy or grotesque after all. Many are waiting on love.

The Narrator, a tenderfoot in a Stetson, is curious and unflappable. His puzzled acceptance of everything that comes his way encourages us to forget what we think we know about hayseeds, the sovereign state of Texas, high-tech industry, suburban sprawl, prefab buildings, and dorky parades. The last we hear of him, he’s already deleting the file, but I doubt we can.

Well, I really enjoy forgetting. When I first come to a place I notice all the little details. I notice the way the sky looks, the color of white paper, the way people walk, doorknobs. Everything. Then I get used to the place and I don’t notice those things any more. So only by forgetting can I see the place again as it really is.

In the film’s final moments, the Narrator’s confession of Warholian passivity turns into a defense of defamiliarization that could have come from Shklovsky. “Art,” he wrote, “exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.” We can perceive true stories only by stripping away our preconceptions.

Byrne the creator has suggested that the film allowed him to find his way back to emotions beyond comfortable irony. “It was hard to go around not liking everything.” We can debate a long time why the end of Louis’s song, “We don’t want freedom/ We don’t want justice/ We just want someone to love,” both shocks and satisfies us. (Today, a Deplorable would change only the lyric’s last word.) But as an expression of sheer self-presentation, it’s hard not to sympathize with this Texas Bachelor.

Although the Narrator can forget, we don’t have to. According to the final song, we can remember this as our favorite town. With this film, Byrne makes sentiment safe for hipster consumption.

Working with Byrne and DP Ed Lachman, producer Kim Hendrickson and her team have supervised a brilliant 4K edition, the first time the film has been presented in 5.1 sound. They’ve included some precious material culled from new interviews, period footage, and excised scenes. There are also informative essays by Rebecca Bental, Joe Nick Patoski, Spalding Gray, and Byrne. The making-of is the best example of the genre I’ve ever seen, and the documentary on Tibor Kalman is quite informative on Byrne’s visual imagination. (The Criterion cover art is one of Kalman’s rejected designs.) One bonus short is a piece of analog video shot behind the scenes; another, by Bill and Turner Ross, is a contemporary return to the places shown in the film.

The film was shot full frame, to be masked in projection; some video versions displayed it at 1.37:1, others at 1.85:1, which is the one presented here. Kim was assisted by technical director Lee Kline, and audio supervisor Ryan Hullings. Also very helpful in the restoration and supplements was Christina Patoski, who organized a large portion of the original production. Many participants supplied photos and notes from preproduction.

Most of my quotations from David Byrne come from the Introduction in the book of the film: True Stories (New York: Penguin, 1986). Byrne’s remark about pockets of Utopia is quoted in Michiko Kakutani, “David Byrne Turns His Head to Movies,” New York Times (5 October 1986), 92.

The Warhol passage comes from Gretchen Berg, “Nothing to Lose: Interview with Andy Warhol,” Cahiers du cinéma in English no. 10 (1967), 40-42. The Robert Wilson quotation comes from Calvin Tomkins, “Time to Think,” in Robert Wilson: The Theater of Images, 2d ed. (Harper and Row, 1980), 84. The Shklovsky quotation is in “Art as Technique,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. Lee T. Lemon and Marian J. Reis (University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 12. I say more about Shklovsky and narrative here.

True Stories.

Catching up with the past: Recent DVD and Blu-ray releases

Behind the Door (1919).

Kristin here:

David and I have moved house recently, which has caused a long lag in my getting around to doing a DVD/Blu-ray roundup of recent releases. Some are not so recent anymore, but I shall call attention to them nonetheless.

Behind the Door (1919)

Our friends at Flicker Alley have been busy, as usual.

Way back in February of last year, they released Behind the Door, a notoriously grim and brutal drama of World War I that long survived only in incomplete form. Using tinting rolls from the Library of Congress, some scenes from star Hobart Bosworth’s collection, and a re-edited Russian distribution print, as well as a copy of the continuity script, the restoration by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the Library of Congress, and Gosfilmofond approximates the original American release version fairly closely. (Two brief missing sections are filled in by photos and the texts of the original titles.) The tinting and toning, based on the Library of Congress material, is authentic and effective (see top), as is the new score by Stephen Horne.

The Russian version is included in the two-disc set, so we have one of those rare cases where it is possible to compare the foreign and domestic versions–to a degree. Most of the shots, of course, were made with a second camera, and there are inevitably differences of framings and even takes between those versions. Given that the new restoration depends heavily on the Russian print, the comparison must be made primarily on the basis of the differences in the order of the scenes and the other narrative changes made by the Russian editors.

Behind the Door tied for Best Single Release in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s DVD Awards, announced just last month. Congratulations to Flicker Alley and to other organizations we have ties to, which also won awards. The Criterion Collection tied for Best Box Set for its 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912-2012. This massive set (32 discs on Blu-ray, 43 on DVD) contains 53 films, including those by Leni Riefenstahl, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch, Carlos Saura, and Miloš Forman. Belgium’s Cinematek won Best Discovery of a Forgotten Film for its Marquis de Wavrin (1924-1937), actually a series of films shot in South America by this major anthropologist and filmmaker. German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (from the BFI and the Imperial War Museum), which David commented on last year, won Best Special Features.

Das alte Gesetz (1923)

I have a particular interest in German silent cinema of the post-World War I era, so I was happy to see Flicker Alley’s release of Ewald André Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (“The Ancient Law”). Most people know Dupont only from his most famous and successful film, Variety (1925), known for its spectacular camera movements taken from trapezes.

Dupont had a long career, however, starting as a scriptwriter in the 1910s and becoming a director as well in 1918. Das alte Gesetz is mainly known as one of a small group of Jewish-themed films made in Germany in the period 1919-1924. More familiar to most would be Der Golem:Wie er in der Welt kam, co-directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (1920) and to some, Die Gezeichneten, Carl Dreyer’s first German film (aka Love One Another, 1922). A helpful essay in the accompanying booklet by Cynthia Walk gives the political context of die Judenfrage (“the Jewish question) as it was being debated in Europe at the time.

Set in the 1860s, the film concerns Barush, the son of a rabbi in a shtetl in western Russia. He suddenly and somewhat implausibly conceives a desire to leave home and become a famous actor. Naturally his father disowns him. Joining a small traveling troupe, Barush ends up in Vienna, where an archduchess, played by Henny Porten, is impressed by his performance as Romeo and attracted to him as well. She arranges for him to join her court-theatre troupe, where he becomes a star as a classical actor.

The scenes in the shtetl (above) are done with considerable attention to authenticity and without the sort of ethnic humor that one might expect. Although Barush encounters prejudice in Europe, he does not evenually learn a lesson about assimilation and go back to his home with his tail between his legs. Far from it; his father is induced to read Shakespeare and suddenly realizes that there are indeed more things in heaven and earth than he had dreamed of in his philosophy. A happy reunion results, and Barush continues his career.

Das alte Gesetz was clearly a big-budget period piece, with several large sets. Moreover, the influence of classical Hollywood films, which began to be shown in Germany in 1921, is quite apparent. Dupont has mastered three-point lighting and analytical editing, including shot/reverse shot, as this scene between Barush and his father demonstrates.

Barush is played by Ernst Deutsch, a major actor of the day, including in Expressionist films. He’s the rabbi’s son in Der Golem as well, and he plays the bank-cashier protagonist in Karl-Heinz Martin’s From Morn to Midnight.

MOD

Flicker Alley has also developed a healthy list of manufactured-on-demand titles. Many of these are out-of-print films from the Blackhawk Collection. The 51 titles currently on the list include many silent classics, some of them difficult to see on disc otherwise, such as Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle and Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa.

The new offerings lately have branched out somewhat to include more recent films. On September 3 of last year, the company released Alex Barrett’s London Symphony (2017) for its home-video debut. In the press release for the disc, the director describes it as “a love letter to a city, but it is also a film about life in the modern era.” As the title indicates, Barrett places his film in the city symphony genre, and its release was timed to coincide with the 90th anniversary of the premiere of Berlin: Symphony of a City. City symphonies tend to be associated with the 1920s, when the genre originated and its most famous exemplars, Berlin and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, were made. The genre has never disappeared, but Barrett has written that he chose “to make the film in a style associated with the filmmakers of the 1920s.”

For me, it captures well the style of the 1920s, and particularly Berlin. Shot in black-and-white, London Symphony falls into four movements, following a day in the life of the city–with, as in Berlin, pauses for lunch and dinner particularly dwelt upon. The opening section concentrates on buildings, and there are the inevitable juxtapositions of old and new (see bottom). Multiple cinematographers filmed the footage, but their work blends into a unified visual whole with many striking compositions.

Ruttmann injects occasional implicit political commentary, as when he juxtaposes shots of beggars in the streets with the well-fed Berliners in restaurants. Barratt concentrates on the beautiful and peaceful side of London–historic buildings, quiet parks, pleasant markets, and river scenes. The rather grubby and crowded atmosphere of, say, the West End of London is nowhere to be seen, which befits “a love letter.”

In January The Indomitable Teddy Roosevelt joined the MOD catalog. This is a reissue of a 1983 television documentary that mixes documentary footage (Roosevelt was the first president to be filmed) and staged scenes.

Edition Filmmuseum

This series continues its steady release of experimental filmmaker James Benning’s works with a sixth two-disc set (DVD only) that goes back to his earliest features, films that solidified his international reputation. The new two-disc set contains two films from the late 1970s, 11 x 14 (1977) and One Way Boogie Woogie (1978). Jim followed up the latter, a series of sixty shots of Milwaukee cityscapes, with 27 Years Later (2005), which presents the same series of locations, and One Way Boogie Woogie 2012, which further documents the changes in the filmmaker’s hometown. All three films are included in this set.

11 x 14 flirts with presenting a narrative without ever really concentrating on it. We see some of the same people at intervals, but no causal events link them, and their actions create situations rather than developing stories. Instead, the film’s shots, some quite lengthy, others brief, explore the urban and rural landscapes of Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural roads and fields in the surrounding area. (A familiar highway sign pointing the way to Madison is glimpsed at one point.)

For the most part the urban images concentrate on run-down areas, with motifs of travel (billboards, airplanes) and drinking (bars and more billboards) hinting at contrasting modes of escape. The shot above captures both motifs at once.

Given that Jim’s films seldom play outside festivals and museum venues, the Filmmuseum series is vital–though many of the images in these films are long or even extreme long-shots and benefit from being seen on a big screen. The last time we had a chance to do so was when RR (2007) was shown at the 2008 Vancouver International Film Festival. The Austrian Filmmuseum also published a book on Jim’s work, which David discusses here.

London Symphony (2017)

FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL: A guest post by Jeff Smith

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Jeff here:

Last week, the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art” videos dropped on FilmStruck. The topic this time was continuity editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Many of our faithful blog readers are surely familiar with the techniques and devices that make up the continuity system. The video is really intended to be a primer for the uninitiated. It illustrates some of the basic formal elements of classical continuity, such as the eyeline match, shot/reverse shot, and the 180° rule.

In the video, I tried to highlight some of the reasons why the continuity system became common among popular cinemas around the globe. The tacit principles of the continuity system help ensure that:

- the story’s dimensions of space and time are clearly communicated to the audience

- characters’ and objects’ positions remain relatively constant from shot to shot

- that eyelines and screen direction stay consistent

- the spectator’s attention is guided to the most salient details in a scene.

The last may be the most important, if least understood. Several perceptual psychologists argue that one of the things that makes cinema a unique art form is its ability to produce attentional synchrony among viewers.

Editing is not the only means of guiding attention, to be sure. Filmmakers use lighting, composition, figure movement, camera movement, and blocking to nudge us to look at particular areas of the frame. The continuity system, though, further harnesses these shifts of attention by yoking them to the timing of cuts. Cuts are often coordinated with natural attention cues in a scene, such as conversational turns, changes in where the characters look, and pointing gestures. As Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting put it, “By piggy-backing on natural visual cognition, Hollywood style presents a highly artificial sequence of viewpoints in a way that is easy to comprehend, does not require specific cognitive skills, and may even be perceived by viewers who have never watched film before.”

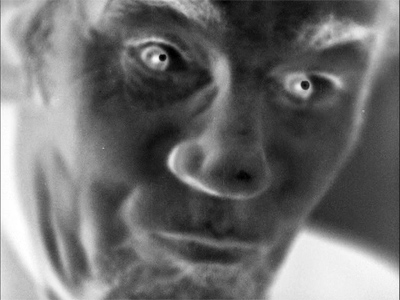

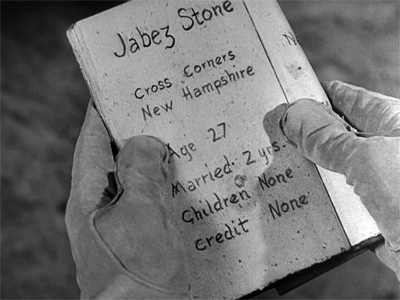

In its deployment of classical Hollywood editing techniques, The Devil and Daniel Webster doesn’t do anything particularly special. Rather, in telling the story of how a New Hampshire farmer, Jabez Stone, sold his soul to the devil, it beautifully illustrates the clarity and efficiency of Hollywood craft at the height of the studio era. Indeed, the editing epitomizes the style of director William Dieterle as a whole: simple, direct, no fuss, no muss.

That being said, The Devil and Daniel Webster does add a few wrinkles to the usual Hollywood style. For example, it uses “trick film” techniques dating back to the era of George Melies to highlight the magical powers of the diabolical Mr. Scratch.

When Jabez throws an axe, it is initially seen as a blur heading straight for Scratch’s head.

A combination of stop-motion substitution and rear projection shows the axe freeze in midair.

A traveling matte is then used as the axe bursts into flames.

Moreover, the Criterion DVD contains deleted scenes from an earlier preview version of the film titled Here is a Man. This alternate version was, in fact, more formally adventurous than the one commonly seen by contemporary audiences. Each time something bad befalls Jabez during the first 20 minutes of the film, Here is a Man cuts to a few frames of photographic negative of Scratch. For instance, when Mary accidentally falls off a wagon, Dieterle cuts to Walter Huston smugly pursing his lips.

Dieterle and his collaborators wisely removed these shots from the final version of the film. The opening scene shows Scratch with Jabez’s name in a small book he carries with him.

When ruinous things start happening to Jabez, viewers naturally infer that Scratch caused them. The oddball moments in Here is a Man, unlike the other effects shots, don’t really add any new information and are heavy-handed in their symbolism.

The Long and the Short of It: Adapting Stephen Vincent Benét to the Silver Screen

Beyond offering good examples of editing craft, The Devil and Daniel Webster is of interest today for other reasons. One involves some of the creative choices made by Stephen Vincent Benét and Dan Totheroh in adapting the former’s short story, first published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1936. The second issue I’ll explore has to do with the way the film speaks to political issues of its moment. It seems endorse a collectivist vision of society as a counter to the excesses of unrestrained capitalism.

Most film adaptations use books for their source material, and most screenwriters face the challenge of condensing the book’s narrative to fit the running time of a typical feature film (roughly about two hours). In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, Benét and Totheroh faced the opposite problem.“The Devil and Daniel Webster” runs less than twenty pages in a Hythloday Press collection of Benét’s short stories. So how do you stretch Benét’s relatively slim tale to fit a 107 minute running time? Benét and Totheroh did what most screenwriters do when they confront the same dilemma. They add incidents, invent new characters, and develop new subplots, adding this material to the existing story spine.

Some print editions of Benét’s story break it into five parts with each new segment introduced with a Roman numeral. Part I introduces Daniel Webster via the tall tales told about him in the New England area. It also provides exposition to Jabez’s blighted existence, and the deal he makes with the devil. After breaking his plow on a stone, Jabez angrily proclaims, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil. And I would, too, for two cents!”

Part II covers the seven-year period of prosperity Jabez enjoys as well as his interest in contesting the mortgage held by the mysterious stranger. This section also establishes the stranger’s mystical powers as Jabez hears the voice of his neighbor, Miser Stevens, coming from a moth-like creature that the stranger captures in a bandanna.

Part III describes Jabez’s recruitment of Daniel Webster for his defense and the preparations for trial. Parts IV and V depict the trial itself. The former introduces the judge and jury, and portrays Daniel’s passionate defense of Jabez. The latter tells of the jury’s verdict and Daniel’s banishment of Mr. Scratch from New Hampshire.

One of the most striking things about Benét’s original story is how much of it focuses on the trial itself. Approximately half of the story covers Webster’s initial deliberations with Mr. Scratch, his demand for a trial, and the legal proceedings. In contrast, these story events account for less twenty percent of the film’s running time.

In expanding the story to feature length, Benét and Totheroh add new incidents, characters, and subplots to the early and middle sections of the screenplay. Consider, for example, Benét’s economy in his prose description of Jabez’s misfortunes:

If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them. If stones cropped up in his neighbor’s field, boulders boiled up in his; if he had a horse with the spavins, he’d trade it for one with the staggers and give something extra.

Years of toil and trouble for Jabez are compressed into three sentences. When Jabez breaks his plowshare, it becomes simply the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, coming at a time when his wife and children are sick and even his horse has a rheumy cough.

In their script, Benét and Totheroh create a handful of new vignettes to illustrate Jabez’s rotten luck. In the film’s first scene, Jabez’s pig breaks its leg after being chased by the family dog. Later, Jabez’s wife, Mary, takes a tumble off their wagon when trying to stop her husband from selling the family’s calf. Still later, a fox gets into Jabez’s henhouse. In the film, Jabez’s breaking point comes not with the plow, but after he spills precious seed in a puddle just outside his barn. Unlike the story’s description of blight and corn borers, these brief episodes not only visualize Jabez’s tribulations, but also contain their own short dramatic arcs.

Another way Benét and Totheroh expand the original story is to add depth and specificity to its secondary characters. In the original, Miser Stevens never appears as anything more than an insect that’s escaped from Scratch’s collecting box. In the film, he is much more fully fleshed-out character, especially as embodied by the wonderful character actor, John Qualen.

Benét and Totheroh’s screenplay uses Stevens to create important story parallels. Like Scratch, who possesses a mortgage on Jabez’s soul, Stevens holds the mortgage to the Stone farm. Yet, Stevens also has made a Faustian bargain with Mr. Scratch. His death at Jabez’s party lingers over the rest of the film, a vivid reminder of what’s at stake during the trial.

Benét’s story also treats Jabez’s wife and children quite impersonally. The characters are never named. The references to them mostly add narrative weight to Jabez’s sense of burden. In contrast, the film version not only give these characters names and individual traits, but also uses them to highlight changes Jabez undergoes once he becomes a wealthy landowner. Jabez and his wife, Mary, frequently argue about disciplining their son, Daniel. Jabez indulges Daniel, spoiling him but offering little in the way of love. Similarly, after becoming successful, Jabez also falls short of what we’d expect of a caring husband.

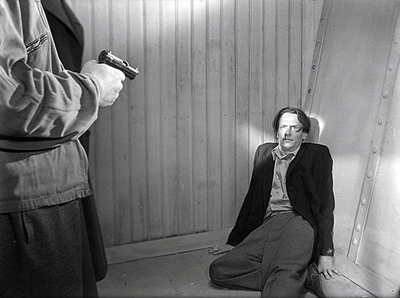

In the middle parts of the film, Jabez becomes crueler and harder. He starts treating trespassers on his land more harshly. He even fires a weapon at one in an effort to scare him away. His anti-social attitudes make him an outcast among the citizenry of Cross Corners.

As was the case with Jabez’s family, the film gives the townspeople more life and personality. Early on, they serve to motivate Daniel Webster’s presence in the story, welcoming him to Cross Corners and serving as a receptive audience for the Senator’s political views. Later, the townspeople act as a foil for Jabez, establishing an important thematic contrast between his laissez faire mindset and their more communitarian values.

Lastly, Benét and Totheroh also invent several new characters for the film adaptation. Of these, the most important is Belle. Loosely allied with Mr. Scratch, Belle is ostensibly Daniel’s nanny, but is implied to be Jabez’s mistress. Belle supplies a sexual temptation not present in the original story, and this complements the temptations of wealth and power. In this respect, the character anticipates the femme fatales found in the cycle of films noir that appear later in the forties, especially as played by Simone Simon at her most fetching.

Although Dieterle was best known for costume pictures rather than film noir, the photographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster sometimes displays the kind of dark, moody look we associate with noir’s Germanic influence. Consider, for example, the shot of Scratch’s entrance into Jabez’s barn. The mists, the backllight, and the gnarled tree in the background all foreshadow the darkness that will soon take hold of Jabez’s soul.

In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, tracing the film’s lineage back to German expressionism is fairly easy. Prior to becoming a director, Dieterle was an actor in dozens of German silent films, including F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). Murnau’s adaptation of Goethe’s play not only shares its narrative conceit with Dieterle’s film, but is also one of the most strikingly photographed of his twenties masterpieces.

Looking both backward and forward, The Devil and Daniel Webster might seem like a link between German Expressionism and American film noir. Like German films of the 1910s and 1920s, Dieterle’s film contains some of the fantasy elements found in canonical titles like The Student of Prague (1913), Der Golem (1915), or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Dieterle’s curious afterlife fantasy Six Hours to Live (1932), discussed in an earlier entry, has a strong affinity with Gothic and Expressionist imagery. Like films noir of the forties, the cinematographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster captures the story’s dark, fatalistic tone.

Indeed, the look of the final trial scene displays the same sort of stylization seen in the dream sequence of The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a film often seen as a key noir progenitor.

Still, Dieterle also retains the folksy Americana that was an appealing part of Benét’s original story. Some of the characters, like Ma Stone or Squire Slossum, seem like they’ve wandered into the story from one of Frank Capra’s small towns or John Ford’s rural comedies. This combination makes The Devil and Daniel Webster a true original. Indeed, it might count as an almost singular example of “cracker barrel noir” if the term itself didn’t seem like a complete oxymoron.

Things That Make a Country a Country, and a Man a Man: Benét’s Tale as Allegory

One of the other things that interests me about The Devil and Daniel Webster is the degree to which both the story and the film can be read as allegory. Benét’s original narrative certainly makes American identity a central theme. The opening paragraph proposes that, if you go to Daniel Webster’s gravesite and call his name, you’ll hear his deep, rolling voice ask, “Neighbor, how stands the Union?” Benét adds, “Then you better answer the Union stands as she stood, rock-bottomed and coppersheathed, one and indivisible, or he’s liable to rear right out of the ground.” This description not only foreshadows the oratorical power that Webster will display when Jabez goes on trial, but also the sacrifices Scratch prophesies. These include Webster’s loss of two sons in combat and a missed opportunity to become president.

Later, Webster will challenge Scratch on the grounds of his nationality, saying “no American citizen may be forced into the service of a foreign prince.” Scratch responds that he is an American, and further that he was present for “the first wrong done to the first Indian” and when the first American slave ship set sail for the Congo. Moreover, when Scratch assembles his jury, he selects a group of black-hearted souls whose dark deeds affected the course of the nation’s history. Among them is the pirate Edward Teach, otherwise known as Blackbeard. There’s also Walter Butler, the architect of the Cherry Valley massacre; Simon Girty, who burnt men at the stake; and Governor Thomas Dale, who Benét claims “broke men on the wheel.” Overseeing the proceedings is Judge John Hathorne, a magistrate in Salem who supervised some of the witch trials.

The larger significance of these passages is hard to ignore. Jabez may be on trial within the narrative, but Benét seems to put America itself on trial. The plaintiff and defendant, thus, come to symbolize the yin and yang of America’s soul. Webster represents the virtues that define the American ethos: grit, pluck, ingenuity, and liberty. Scratch, on the other hand, associates himself with the nation’s original sins: genocide, slavery, cruelty, torture, and theocratic inquisition. Webster emerges victorious in the legal battle, but as he says in his summation, our citizens’ hard-won freedom came at a cost of suffering and tribulation. Successes and failures are all part of the great journey of humanity. Says Webster, “And everybody had played a part in it, even the traitors.”

Dieterle’s film preserves all of these elements of Benét’s short story, but adds a couple of wrinkles of its own. First, General Benedict Arnold is added to the film’s panel of jurors, even though he is pointedly absent from the original. In the story, Webster observes that he misses Arnold’s company and is told that the General is engaged in other business. Benedict Arnold is not only fully present in the film version, but is even featured prominently during the trial scene in several medium close-ups.

Webster even singles out Arnold in his impassioned defense of Jabez’s character. Using Arnold’s betrayal of his country as a cautionary tale, the orator asks the jury to give Jabez the second chance that the devil denied to them.

The other, even more important, change made by Benét and Totheroh is the subplot concerned with the formation of the Grange. Officially known as the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, the Grange was founded in 1867 to promote the interests of farmers and rural communities. But Webster died in 1852. As an addition to the screenplay of The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Grange seems to be a historical anomaly.

So why this anachronistic subplot? The simple answer is that it sharpens the conflict between Jabez and the other townspeople. Not only is he differentiated in class, but he’s set apart by his personal values. The less obvious answer involves the film’s historical context. Released in 1941, the story of a lone holdout resisting the pressure of others in his community likely would evoke broader geopolitical issues. The plea for unity in the face of existential evil would seem to suggest The Devil and Daniel Webster works as an allegorical critique of American isolationism on the threshold of World War II.

Like other allegories, this type of reading follows a pattern of metaphorical substitution. The Grange becomes a stand-in for the Allied Powers. Scratch represents Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo, and other Axis leaders. And, as discussed above, Stone and Webster symbolize America itself.

Dieterle’s earlier career in Hollywood also offers some additional warrant for this interpretation. He was a German Jew who emigrated to the U.S. in 1930. His relocation was less about fleeing the Nazis than it was the opportunity to work for Warner Bros. Still, Dieterle bore witness to the corrosive effects of Nazi ideology, and his directorial assignments show a loose affiliation with anti-Fascist politics. He helmed The Life of Emile Zola, a Warners biopic that depicts the French author’s involvement in the Dreyfus affair. The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1938. Thanks to its timely exploration of anti-Semitism, Zola burnished Warner Bros. reputation as Hollywood’s most socially conscious studio.

That same year, Dieterle directed Blockade (1938) for producer Walter Wanger. Although it is mostly a routine espionage thriller, the film is now remembered as one of the few films Hollywood made about the Spanish civil war. As scripted by John Howard Lawson, who later was blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten, Blockade is now seen as an emblem of the Popular Front. Most film historians associate it with anti-Fascist politics, even though the film pointedly avoids identifying the Loyalist and Nationalist sides of the conflict.

Unlike these previous projects, The Devil and Daniel Webster positioned Dieterle as both producer and director. The creative decisions involved in the addition of the Grange subplot would seem more directly under his control. The film’s thematic emphasis on collective interests seems to suggest this political subtext in much the same way that Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) is sometimes viewed as a parable of democracy’s failure in the face of dictatorship.

In highlighting this allegorical dimension of The Devil and Daniel Webster, I don’t wish to suggest that it makes the film inherently more interesting. Indeed, like other allegorical interpretations, it seems a bit reductive and simplistic. More importantly, if taken too far, these types of interpretive strategies quickly become wrongheaded and even silly (i.e. Belle as a stand-in for Vichy collaboration).

Yet, I also can’t help but feel that The Devil and Daniel Webster’s invocation of American identity offers something important to a contemporary audience. If, like me, you bristle every time you hear “American interests” referenced as the reason to abandon the Paris Accords or to potentially withdraw from NATO, then you have a sense of the film’s relevance to our moment.

The whole arc of the Grange subplot seems to invert much contemporary political rhetoric insofar as it dramatizes the social benefits of the Commons and the individual tragedy of self-interest. In the parlance of our times, Jabez is a risk-taker, mortgaging his immortal soul for the promise of earthly riches. Yet, when we see the resulting inequality in Dieterle’s film, we recognize the situation for what it is. For Jabez, Miser Stevens, and other capitalist mountebanks, it is, quite literally, a deal with the devil. And that, consarn it, is a lesson that all modern viewers can take to heart.

A handy introduction to the continuity system can be found in Chapter 6 of Film Art.

To learn more about the role of editing in guiding viewers’ attention, see Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting, “A Window on Reality: Perceiving Edited Moving Images,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21, no. 2 (2012): 107-113. A PDF of this essay can be found here.

Stephen Vincent Benét can be found in many places around the web, including here. Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (1974, University of California Press) remains a useful introduction to the movement’s lighting and visual motifs. For more on the interpretation of films as political allegories, see my book Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds (2014, University of California Press).

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Bye bye Bologna

Lucky to Be a Woman (1955).

DB here:

How to sum up nine days of Cinema Ritrovato? I logged thirty-two features and half as many shorts and fragments, along with a few panels and workshops. Fate cursed me with the need to blog and to sleep, so I missed many prime items. And that’s including my (sad) decision not to revisit films I’d already seen, so I sacrificed new exposure to masterpieces from Ozu, Mizoguchi, Feuillade, Leone, de Sica, etc.

In this last Bologna roundup, all I can do is wave at some of the surprises and discoveries that captivated me.

Many of my pals praised the Mexican noir Western Rosauro Castro (1950), which I had to miss, but I did get compensated by Prisioneros de la Tierra (1939), an Argentine classic of romantic realism. The plot concerns the exploitation of peasant migrants forced to work in dire conditions. One scene, of a drunken doctor in the throes of the DTs, got a rise out of Jorge Luis Borges.

Even more shocking was the red-light melodrama Víctimas del Pecado (1951, above) by the great Emilio Fernández. A newborn baby dumped into a garbage can; a preening, sadistic pimp who can smoke, chew gum, and dance frantically at the same time; a nightclub dancer who tries to live righteously but winds up in prison for her pains; and several splashy music numbers–who could resist this? Not the Bologna audience, who burst into applause when, after slapping a child silly, said pimp got a quick and violent comeuppance. Of course the gorgeous cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa contributed a lot: One shot of a train blasting black smoke into the night would be enough to exalt a far less delirious movie.

Thanks to Dave Kehr of MoMA, who brought a sampler from his recent Fox retrospective, and to UCLA and other sources, aficionados of American studio cinema had no shortage of delights. Monta Bell’s Lights of Old Broadway (1925) gave Marion Davies a dual role as twins separated at birth and she made the most of half of it, playing a no-nonsense colleen who makes it big at Tony Pastor’s. Part of the fun was the film’s historical references: Teddy Roosevelt as an undisciplined schoolboy, Weber & Fields as a kiddie act, and a solicitous Thomas Edison urging the heroine to invest in electricity.

Ten years later, One More Spring (1935, above) from Henry King offered a gentle seriocomic Depression tale. Two homeless men squatting in a garage take in a woman who sleeps on the subway, and they try to make ends meet with the help of a kindly old couple. At first engagingly episodic in the McCarey manner, the plot gets more tightly bound when the old couple faces the loss of their savings. Janet Gaynor is endearing, as usual, and Warner Baxter brings his clipped energy to the role of a hopelessly optimistic failure. There are no villains. The banker struggles to save his depositors, though he’s frank enough to admit, “It’s all the fault of the Republicans. Still, I’ll vote for them in the next election. With the Democrats you never know what to expect.” Another big laugh from the crowd around me.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

Another 1940s technique was the chaptered or block-constructed film, Holy Matrimony (1943), a genial comedy about switched identities, contains sections with titles like “But in 1907” and “And so in 1908.” The film, about a painter brought back to London from his tropical hideaway, reworks the Gauguin motif made famous by Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence (1919). Was this release an effort to build on Albert Lewin’s 1942 version of the novel? Monty Woolley plays himself, but Gracie Fields brought real warmth to the clever, ever practical woman who marries him.

Holy Matrimony was a welcome, if minor entry in the John Stahl retrospective. I had to miss the much-praised When Tomorrow Comes (1939) but was happy to break my rule of avoiding things I’d seen before when I had a chance to revisit Imitation of Life (1934). I persist in thinking this better than the Sirk version, not least because of its harder edge. Beatrice Pullman’s exploitation of her servant Delilah’s pancake recipe carries a sharp economic bite, and the brutal classroom scene yanks our emotions in many directions. (While Peola writhes in her seat, her mother asks innocently, “Has she been passin’?”) As in Stahl’s other 1930s efforts, his studiously neutral style is built out of profiled two shots in exceptionally long takes.

Ritrovato has always done well by its diva films, under the curatorship of Marianne Lewinsky. (They’ve just released a hot-pink box set of four classics.) In tribute to 1918 there were several star vehicles. I’ve already mentioned L’Avarazia (1918), an installment in a Francesca Bertini series devoted to the seven deadly sins.

Another high point was La Moglie di Claudio (1918), an exemplary tale of excess. When a movie starts by comparing its heroine to a spider, you know she means trouble. Cesarina (Pina Minichelli) two-times her husband, has an illegitimate child, flirts relentlessly with her husband’s protégé, collaborates with spies, and steals the plans to the cannon the husband has designed. She does it all in high style. As she dies, she falls clutching a window curtain.

In a fragment from Tosca (1918), we got a quick lesson in the illogical powers of cinematic composition. Tosca (Bertini again) visits her lover Mario in prison. Their furtive conversation is played out while the shadows of the guards come and go in the background. That’s a source of some suspense for us.

And for the couple as well. Instead of looking left at the offscreen window itself, which they could easily see, they–like us–turn to monitor the silhouettes.

It’s a nice variant on the background door or window so common in 1910s film.

Of all the surprises, the biggest for me was This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension, 1950), an Ingmar Bergman thriller. You read that right.

This Cold War intrigue shows spies from Liquidatsia (you read that right too) infiltrating a circle of refugees living in Sweden. The first half hour is soaked in noir aesthetics, with men in trenchcoats glimpsed in bursts of single-source lighting. The preposterous plot gives us a briefcase full of secret papers, attempted murder by hypodermic, torture scenes, and enemy agents acting impossibly suave at gunpoint. A cadre meets in a movie theatre playing a Disney cartoon, with Goofy’s offscreen gurgles punctuating an informer’s confession.

Bergman forbade screenings of the film, but Bologna was given the rare chance to reveal another side of his obsessions with brooding solitude and the pitfalls of love. Peter von Bagh’s illuminating essay included in the catalogue rightly emphasizes how in This Can’t Happen Here murder becomes the natural outcome of an unhappy marriage.

My visit was topped off by the charming Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) in the Mastroianni strand. Sophia Loren, looking like a million and a half bucks, plays a working girl accidentally turned into tabloid cheescake. Mastroianni is a louche photographer who can make her career. Bantering at breakneck speed, they thrust and parry for ninety-five minutes, all the while satirizing modeling, moviemaking, and the itchy palms of philandering middle-aged men. Mastroianni spins minutes of byplay out of an unlit cigarette, while La Loren plants herself like a statue in the foreground, facing us; if Marcello’s lucky, she may address him with a smoldering sidelong glance.

What’s not to like? After thirty-two years, Ritrovato’s magnificence is unflagging.

As usual, thanks must go to the core Ritrovato team: Festival Coordinator Guy Borlée (with appreciation for help with this entry) and the Directors (below). They and their corps of workers make this vastly complex celebration of cinema look easy. It’s actually a kind of miracle.

Ehsan Khoshbakht, Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, and Gian Luca Farinelli.