Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

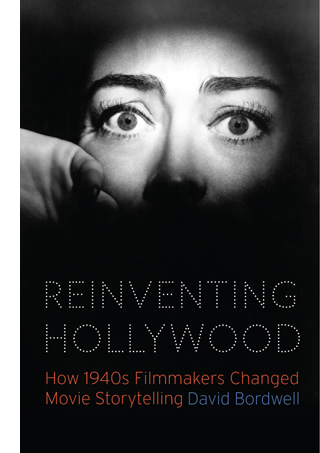

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in NYRB

Backfire (1950).

DB here:

The New York Review of Books has just published a review by Geoffrey O’Brien of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. This is a big deal for me.

I never thought my work would be reviewed in a publication I’ve subscribed to since my college days. And to be reviewed by O’Brien is a special honor. He’s one of those wide-ranging intellectuals who are rare today. He writes fiction and poetry, and offers criticism of film, literature, music, painting, and theatre. He’s ideally equipped to appraise my arguments about how 40s cinema drew on narrative conventions in adjacent arts. He’s also a connoisseur of the obscure and marginal in classic studio cinema.

I especially admire his writings on noir film and literature, on popular music, and his study of American cinema as a sort of popular hallucination. The Phantom Empire makes this case memorably, but the opening of his review catches the flavor too.

One night not long ago I found myself once again drawn into a movie from the tail end of the 1940s. This one, with the thoroughly generic title Backfire (not to be confused with Crossfire or Criss Cross or Backlash ), did not come with a high pedigree. It had sat on the shelf for two years after it was filmed in 1948, and afterward seems to have faded quickly from recollection. But movies of that time, when they emerge decades later, have devious ways of holding the attention: beguiling hooks and feints lead deeper into a maze whose inner reaches remain tantalizing no matter how many times those well-worn pathways have been explored, and no matter how many times the interior of the maze has led only to an empty space.

One night not long ago I found myself once again drawn into a movie from the tail end of the 1940s. This one, with the thoroughly generic title Backfire (not to be confused with Crossfire or Criss Cross or Backlash ), did not come with a high pedigree. It had sat on the shelf for two years after it was filmed in 1948, and afterward seems to have faded quickly from recollection. But movies of that time, when they emerge decades later, have devious ways of holding the attention: beguiling hooks and feints lead deeper into a maze whose inner reaches remain tantalizing no matter how many times those well-worn pathways have been explored, and no matter how many times the interior of the maze has led only to an empty space.

In a state of suspended fascination only just distinguishable from the preliminary stages of dreaming, I remained absorbed as documentary-style scenes of wounded war veterans recuperating at a hospital in Van Nuys, California, gave way to progressively more disjointed and often barely comprehensible episodes: an unidentified woman creeping in the dark into a patient’s room with a message about a missing war buddy, a murder investigation, a cleaning woman peering through a keyhole in a fleabag Los Angeles hotel, a winding path from mortuary to boxing arena to gambling den to the office of a particularly corrupt doctor, a plaintive piano theme playing over and over accompanied by reminiscences of its origin in a far-off Austrian village. The story splintered into flashbacks, spiraling into deepening confusions of identity and chronology, punctuated, as if to keep the spectator awake, by a series of point-blank shootings.

All the while, the dialogue was evoking the trauma of wartime injury, questioning the difference between memory and hallucination, talking about nightclub rackets, tax evasion, gambling debts, obsessive love, as the narrative coiled in its final swerve toward a strangling, silhouetted on a bedroom wall while Christmas carols were sung in the background. And then, abruptly, the nightmare was over, we were back in the veterans’ hospital after a second and successful round of rehabilitation, and the three surviving principal characters were even managing to laugh as they took off in their jeep for Happy Valley Ranch. By then I could hardly have said what the movie was about or even if it was especially good—few viewers have ever thought so—yet could not deny that something had caught me in its grip and stirred up troubling associations, like partially retrieved memories of a parallel life.

Apart from wishing I could write like this, I find myself agreeing. Popular culture does offer us a phantasmagoric alternative world that we can drift through in an almost somnambulistic way. I don’t see this argument as the sort of Zeitgeisty criticism I’ve complained about elsewhere. Rather, I think it’s in the spirit of Parker Tyler, who saw Hollywood not as reflecting a collective psyche but as building occasionally rickety story worlds out of cultural flotsam scavenged from wherever. Not a mirror but a mirage.

That hallucination demands that conventions and schemas, norms and forms, bring order to an occasionally demotic array of materials. Given this orientation, the sort of analysis I float in Reinventing Hollywood might seem to be overthought and flat-footed. But O’Brien gets into both the book’s research assumptions and its ambitions. He sees that I was trying to figure out how the dépaysment of Forties cinema stems from the frantic pressures of the industry, ambitious filmmakers itching to explore unusual narrative strategies, and the jolts that occur when time schemes collide, motives get muddled, and story premises wriggle out of control. To savor eccentricities, you need the sense of a center, and that’s where my inquiry starts.

It’s a generous review. O’Brien makes my arguments crisp and cogent, and he adds ideas of his own. It’s a review that both fans and nonspecialists can learn from, as I did. It’s also good to know that some of my jokes didn’t fall flat. (I can hear readers asking: Wait, there were jokes?)

For more on Reinventing Hollywood, go to the tag 1940s Hollywood. The book is available from the University of Chicago Press website and the mighty Amazon. As ever, I owe thanks to the University of Chicago Press staff, particularly Rodney Powell, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Levi Stahl, and Melinda Kennedy.

I discuss Parker Tyler’s conception of the Hollywood Hallucination in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

Wisconsin Film Festival: Footage fetishism

The Green Fog (2017).

DB here:

Kristin and I have been unusually busy during this year’s fest, its twentieth, so I got to see only ten of the vast array of offerings. Herewith a first report on what our intrepid team–Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Matt St John, and Ella Quainton–programmed and put before adoring crowds. Today we look at movies about movies.

JLG par Not JLG

The title of Michel Hazanavicius’s Le redoubtable has been Francoanglicized as Godard mon amour, not a bad way of signaling it’s a French movie. (The same tactic turned Nikita into La Femme Nikita.) The title also lets us know it centered on the most important living director. And the possessive pronoun correctly puts us in the place of the heroine, the late Anne Wiazemsky, whose memoir-novel chronicled her few years with Godard. How could the film not take her side? On my limited exposure to the man, “difficult” doesn’t begin to describe his temperament.

The film omits Anne’s role in Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar, which Godard admired extravagantly, and takes us briefly through the shooting of La Chinoise (1967). Soon we’re plunged into ’68 debates about making commercial films, making political films, and “making films politically.” We’re firmly attached to Anne, to the point that Godard’s activities at the Cannes festival are kept obstinately offscreen while we see her sunbathing at a villa. There are unattributed voice-overs from an older male, but mostly we’re in Anne’s consciousness as she struggles to live with the torn, cruel, more or less ridiculous man who brought her into the film industry.

As a satire, the film goes for straightforward targets, such as the moments when people come up to our filmmaker and ask why he doesn’t make movies like Contempt any more. That seems to be Hazanavicius’s question as well. He makes no effort to match his film’s style to Godard’s work in the years when the story takes place. It would have been bold, though probably off-putting, to mimic La Chinoise or Le Gai Savoir (1969), one of his most daring experiments, a sort of Child’s Garden of Semiology. Instead we get snatches of pre-1967 scores, chapter titles, compositions, and iconography, with special emphasis on Une Femme mariée (1964), perhaps a sly reference to Anne’s role.

While pastiching the early work, Hazavanicius softens its edges. One of Godard’s minor innovations, for instance, was inserting a chapter title partway through a new section, rather than planting it at the outset. That not only blurs the boundary between segments and usefully jars the viewer, but it also lets the title give a sharper commentary on the images around it. Tarantino embraced this technique, but Hazanavicius is tidier in his chaptering. Similarly, his shoutouts to planimetric framing don’t really exploit their disruptive possibilities.

His film reminds us that Early Godard has become virtually a period style. Hence, perhaps, Godard’s own flight from it over the last forty years, in the process making films of exceptional beauty and abrasiveness. Still, we tend to forget how unsettling the early films remain. (At the Venice International Film Festival last year, Kristin attended the packed 400-seat screening of the restored Two or Three Things I Know about Her and reported that perhaps a third of the audience had walked out by the end.) Despite all his influence, the original Godard will never become “normalized,” just as Schoenberg will never become elevator music.

Godard mon amour goes down easy and doesn’t, to my way of thinking, have a brain in its pretty head. Godard emerges as a wacky celebrity, politically confused and emotionally bullying. There’s no attempt to show how his personality surfaces in his art, or even why his art is important. Still, Godard mon amour usefully calls attention to a director who, in his 88th year, has another feature coming to Cannes. It’s called Livre de l’image, and it promises to be in five chapters, like the fingers of a hand.

Fog over Frisco

Made on commission from the San Francisco International Film Festival, The Green Fog is a collage exercise in associational mode, with echoes of Craig Baldwin’s work. In their own gonzo filmfreak way, Guy Maddin and Evan and Galen Johnson have created an homage to the city and its ultimate film, Vertigo.

It can please on many levels. First, there’s the spot-the-clip quiz in the manner of Marclay’s The Clock. Some bits I found fairly easy to identify, but others are drawn from obscure movies and TV programs. All showcase San Francisco. Second, there’s the looping and twisting motifs of male-female tension, surveillance (films projected, phone lines tapped), and class identity: we’re forced to notice how tony restaurants set the stage for 80s big-hair melodrama.

Then there’s the pleasure of watching how cutting can suggest expanding narrative trajectories through eyelines. The Green Fog is an extended exercise in the Kuleshov effect. Sometimes the whole process gets embedded: people watch screens showing people watching people. Or they’re watching a scene from another movie: McMillan, without wife, sees a tree that was 68 years old when Jesus was born.

These linkages are accentuated by the habit of omitting lines of dialogue, so that characters seldom speak but, in shots plagued by visual hiccups, emphatically react to one another, sometimes just by smacking their lips or gulping.

Not least, The Green Fog is a free fantasia on incidents and images from Vertigo. Although only one Vertigo shot is shown, the canonical moments are evoked by their mates in films both earlier and later: people scrambling up buildings and plummeting, couples embracing in horse stables, men pulling women out of the bay, and–thanks to the invading green miasma–a woman stepping out of a doorway to confront her lover. Scotty’s vision of Judy’s aura is made into a city-wide contagion of obsessive love.

The film takes our memories of bits of Hitchcock’s film and spirals out from them, creating a hallucinatory whirlpool of variations on clichés. Going beyond Vertigo, the film evokes its own vertigo, a media phantasmagoria. I was reminded of Geoffrey O’Brien’s book The Phantom Empire.

How did you wander into this maze, anyway, and how would you get out? Do you in fact want to, or do you prefer to sink deeper into it, savoring its manifold ramifications and outlying distortions?

The teeming image-clusters of The Green Fog, made even more eerie and lyrical by Jacob Garchik’s score, capture the delirium of cinephilia, reminding us of how much a masterpiece owes to anonymous, banal visions pulsing through popular culture.

Right here in River City

William Brinton and his wife Indiana were a colorful couple. They were nudists and kept a mummy in their living room. More to our point, around 1900 they ran an Iowa theatre and traveled throughout the midwest showing films and lantern slides. Brinton died in 1919, Indiana in 1955, and the executor of her estate in 1981.

The Brinton collection passed to Michael Zahs–junior-high history teacher and confessed “saver” of things. Three truckloads of boxes came to Zahs labeled “Brinton crap.” They contained over 130 films, 700 magic-lantern slides, many sound recordings, and a host of vintage equipment.

Zahs was told to bury the nitrate materials and dispose of the rest. Instead he hung on to everything, and eventually the American Film Institute and the Library of Congress selected several reels for preservation. Since 1997 16mm copies of Brinton titles have been shown in festivities at the Graham Opera House in Washington, Iowa–a site recently declared by the Guinness Book of World Records to be the world’s oldest surviving film venue. The University of Iowa Library has committed to keeping safety copies of the entire collection.

This fascinating story is brought to light by Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherbourne of Northland Films. Saving Brinton is, like Bill Morrison’s Dalton City: Frozen Time (reviewed by Kristin here), a heroic tale of cinema lost and refound. Morrison’s film centers on 1910s and early 1920s features, but the Brinton legacy takes us back to earlier times. There are “actualities” (newsreels) and gag reels and even–watch Serge Bromberg’s eyes light up–a lost Méliès. Many items are in superb condition, with well-preserved hand-coloring. There are films from Lumière, Edison, and other major companies. In one, a powerful panning shot shows Teddy Roosevelt parading down Market Street in San Francisco (without green fog) just before the earthquake. And then there are the projectors and paper, including a Pathé catalogue.

Saving Brinton is as much a portrait documentary as an account of film rescue. The Brintons stand out, not least for William’s fascination with airships, but the star of the present-day show is Michael Zahs. With his Darwinian beard and jovial presence, he comes across as one of those impresarios who knows a lot about everything, from chemistry to grave marker symbolism. For four years the filmmakers followed his efforts to preserve and show the Brinton legacy, while also tracing his personal life. We get scenes of his devotion to his ailing mother, who died during filming, and interplay with his wife, a smiling woman who doesn’t mind sharing her household with combustible materials. At the same time, this packed documentary evokes the community that welcomed Zahs’ cheerful obsession. As a graduate of the University of Iowa, I had to beam at the sheer niceness radiating from these people and their town and the earth they steward.

On 23 April the University Library in Iowa City will be screening the whole collection, with seven projectors running the films on loops. You can sample them online, in pretty copies. And Saving Brinton will continue to tour festivals; you can track its progress here. This charming documentary is a must-see for everybody who loves old movies, not to mention flyover Americana.

My quotation from Geoffrey O’Brien’s The Phantom Empire: Movies in the Mind of the 20th Century (New York: Norton, 1993) comes from p. 28.

The Saving Brinton website gives more information on the film. Diana Nollen’s story in The Gazette supplies helpful background. Watch the trailer and glimpse our old friend Rick Altman, emeritus at the University of Iowa.

The Language of Flowers (n.d.).

You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t

Casablanca (1943).

DB here:

How could I have written a longish book on 1940s Hollywood and have devoted so little space to Casablanca?

This question was brought home to me when Pauline Lampert, mastermind of Flixwise, asked me to be a guest on her podcast….and to talk about Casablanca. You can listen to our conversation here. Yes, Joan Crawford is involved.

Reinventing Hollywood mentions Casablanca in a few places, but it doesn’t discuss it in the depth it devotes to, say, A Letter to Three Wives or Cover Girl or Five Graves to Cairo or Unfaithfully Yours, let alone Swell Guy or Repeat Performance or The Guilt of Janet Ames. I suppose it’s partly because many of those movies are less famous and more peculiar.

In addition, I confess that I’ve never been a big fan of Casablanca. I admire it as a solid piece of work, but it hasn’t aroused my passion. I’m much more emotionally attached to How Green Was My Valley, The Magnificent Ambersons, Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Meet Me in St. Louis, Mildred Pierce, The Little Foxes, On the Town, and many other movies of its time.

Admittedly, my book doesn’t dwell on most of these either, although I’ve written about most of them elsewhere (including on this site). Basically, I suppose I neglected Warners’ evergreen classic because its canonical status made it unnecessary for me to talk about it. It’s a typical 40s film that everybody knows well, and I guess I trusted that interested readers would apply to it the ideas I float in the book. And another factor may have blocked my considering Casablanca.

Learning from a classic

When historians want to explain changes in film artistry, they have some options. One possibility is to focus on the influential individual, the great artist who inspires successors. Charles Rosen makes this case in The Classical Style, which concentrates on Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven as prime innovators. Traditional film historians have singled out Griffith for this role; I’d add Ozu and Antonioni, in their respective contexts, as significant influencers.

A second option is to zero in on an individual work that became a prototype for other works. The Birth of a Nation, Potemkin, Citizen Kane, and The Bicycle Thieves have played this role in film histories.

A third possibility is to explain change through patterns of collective practice. Creative choices, disclosed in several (perhaps minor) works, propagate through a community and eventually establish norms. This seems to have been what happened with tableau staging and the system of continuity editing. They emerged in bits and pieces, as ad hoc practices that were forged into firm craft practice.

Without denying that some individuals, like Welles and Hitchcock, matter, and without denying that there are powerful models, such as Kane, my book was mostly committed to showing how narrative norms, pressured by competition and other factors, mutate across the 40s ecosystem. This emphasis on norms is one aspect of my research program.

So in re-watching Casablanca for my meeting with Lady P.’s podcast, I noticed some norm-abiding and norm-tweaking things I could have written about.

Classical plot construction (of course). Despite the legend of last-minute screenplay fixes, this is a tightly organized plot. Kristin’ s four-part structural template is in force. After shrewdly distributed exposition, Laszlo and Ilsa stroll into Rick’s at the 25-minute point. At the midpoint (about 50:00), Rick calls Ilsa a whore and she departs to meet Renault. The climax, I’d say, starts around 80:00, when Rick and Ilsa reconcile and he hatches his plan to rescue her and Laszlo.

The parallels are also well-carpentered. Rick is compared to Laszlo; both have been activists. Rick’s also like Renault, in that both are now in-between men, apolitical cynics who will convert to the cause. Ilsa is paralleled to Rick’s high-strung paramour Yvonne, as well as the Bulgarian woman who has concealed from her husband the fact that she traded her body for safe passage out of Casablanca.

Ticking the 40s boxes: Voice-over narration to open the thing? Check. Crisis structure that launches an explanatory flashback? Check.

Franker sexuality and Parker Tyler’s Morality of the Single Instance? Check-plus. When Ilsa comes to Rick’s apartment, they obviously do the thing. He later says they “got Paris back last night.”

And of course it’s a feast of 40s character actors, including Rains, Lorre, Greenstreet (in a silly fez), Veidt, Kinskey, Dalio, and Sakall (aka Cuddles).

Even John Qualen shows up. Casablanca is as much an oddball hangout as Casablanca is.

Domesticating deep focus: Part of the influence of Citizen Kane stemmed from its flaunting of big-foreground depth. A head or an object would be pasted in the front plane, and other figures would stretch out in the distance.

Kane wasn’t the first film to use this strategy, but Welles and Gregg Toland made it vivid by playing out these shots in very long takes. After Kane, 1941 became the Year of the Big Head, apparent in The Little Foxes and, surprisingly, Ball of Fire. Toland shot these.

But these films didn’t treat such compositions in long takes. Wyler and Hawks integrated the wide-angle shots into a standard analytical editing breakdown, using the big foregrounds for orthodox shot/ reverse shot. We see the trend as well in tighter-than-usual over-the-shoulder shots like these from The Maltese Falcon, also 1941.

Curtiz wasn’t as flamboyant a stylist as Welles, but he often added pictorial zest to his shots. He too integrates the wide-angled foreground into standardized setups and editing patterns. Interestingly, his cinematographer was Arthur Edeson, who shot Falcon.

In this respect, Casablanca exemplifies how a new norm was diffused as a toned-down version of a more self-conscious technique.

Smooth visual and verbal narration: This time around I admired the opening passage, with rapid exposition based on adjacency. We start at street level, as the police capture suspected agents of the Free French. One is gunned down, in a moderate deep-space composition. And everything is explained by a chatty pickpocket.

The Bulgarian couple is planted in a panning shot that follows the secret agent and settles on them. (Again, the wide angle accentuates foreground action.)

We get continuity by contiguity. A neat touch: Major Strasser’s plane arriving is glimpsed in conjunction with Rick’s sign, setting up that location well before we visit it. (See still up top.) At the airport, Renault closes the loop, explaining to Strasser that everybody comes to Rick’s. That initiates a dialogue hook to the café, where we’ll spend the next thirty minutes of screen time. And the arrival of Strasser’s plane rhymes neatly with the departure of the one carrying Ilsa and Laszlo at the end.

Motifs, motifs: In a movie where every scene has a famous tagline, I was struck this time by one tweak. Meeting Strasser, Renault says that he’ll round up “twice the usual number of suspects.” In the epilogue, that phrase becomes the nonchalant one everybody remembers, “Round up the usual suspects.” It’s a reminder of corrupt policing, a guarantee that Rick will not be charged, a sign of Renault’s new loyalties, and a contrast to Renault’s initial obedience to the man Rick has just killed.

Seeing eye to eye: I’ve written elsewhere (here and here and here) about the importance of eye behavior in storytelling cinema. In Casablanca, I noticed how Edeson’s cinematography made the women’s eyes glisten. This is standard female lighting for the period, but Ingrid Bergman often gets an extra princess sparkle.

As for Bogart, often a blinker, he lowers his eyes ambiguously when he says that Renault has always kept his word.

When the Bulgarian woman asks about a woman who keeps secret something to save her husband, he manages to shift into a stricken stare for eleven seconds: “Nobody ever loved me that much.”

Actually, Bergman beats him when Sam plays “As Time Goes By.” Ilsa stares, slightly shifting her head but with a largely blank expression, though her mouth opens slightly.

She doesn’t blink for twenty-four seconds. Nearly all the action is in those eyes, as a glint of light jumps from her right eye to her left.

A 1940s movie, over-solemn as it can sometimes be, has this virtue: it can show people thinking.

When you try to study filmmaking norms, often you find that the individual film becomes a “tutor text,” as the French Structuralists used to call it. The movie shows you things about movies. His Girl Friday, I’ve argued, is such a film for me. Maybe Casablanca should be. In any event, we can learn a lot from it, and in the process still enjoy its drama of love sacrificed to political commitment.

Thanks to Pauline for having me on Flixwise. Kristin’s analysis of four-part plotting, first floated in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, has been applied and expanded in my The Way Hollywood Tells It and many of our site entries, as here and here. I discuss Parker Tyler’s Morality of the Single Instance in The Rhapsodes. My deep-focus arguments can be found in Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema and developed at greater length in On the History of Film Style, soon to be available in an updated version on this site. See also this entry and this one and this one.

Casablanca.

New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking

La La Land.

DB here:

Between the end of principal photography on First Man and the start of post-production, Damien Chazelle squeezed in a visit to the UW–Madison. We’re very glad he did. A hell of a time was had by all.

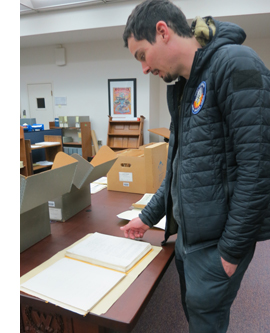

His visit culminated a Cinematheque series devoted to his work. On Friday 23 February we picked him up at O’H are and had a fine ride back talking about film and less important things. Then he visited our archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; on the right, he examines an original Final Revised script of Citizen Kane.

are and had a fine ride back talking about film and less important things. Then he visited our archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; on the right, he examines an original Final Revised script of Citizen Kane.

After that, he sat down for a conversation about his career with a hundred or so students. At a quick dinner, he and our Cinematheque impresario Jim Healy gave dueling impersonations of Michael Gazzo as Frankie Pentangeli. Damien then plunged into a long Q & A with a full house who had just seen La La Land in 35mm.

Next morning he met with Criterionistas Kim Hendrickson and Grant Delin for a FilmStruck segment. Then, in a discussion with Kelley Conway, he introduced a string of films he curated for the Cinematheque. But he wasn’t off the hook, because driving back to O’Hare with Kelley and Jeff Smith, he was immersed in more film talk.

Damien proved himself the ultimate guest—friendly and generous, enthusiastic and excited, free of airs and snark. We learned a lot from him. Herewith, a sample.

A Direct-Cinema musical

Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench.

Although he considered a musical career, film was Damien’s first love. He wrote scripts in middle school, transcribed movie dialogue from VHS tapes, and as an undergrad watched films in Harvard’s magnificent archive. The film program there, with leaders like Alfred Guzzetti and Ross McAlwee, stressed documentary and experimental film, and the exposure stuck. Among the films Damien curated for our Cinematheque show were the Rouch-Morin investigation Chronicle of a Summer and Su Friedrich’s Sink or Swim.

No surprise, then, that his first feature, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, was shot in a Direct Cinema mode. It’s got light leaks and run-and-gun footage, complete with bumpy handheld pans and zooms. To get around problems of inexperienced actors, Damien told some of them that it was a documentary. The 16mm project was produced over three years; sometimes the exposed films sat in the lab while Damien drummed up donations from friends, family, and strangers. (Writing blind to Harvard alums, Damien got a donation from John Lithgow.) When a processing accident ruined some footage, Damien’s producer talked the lab into free work for a time.

Guy and Madeline cuts among three characters: trumpeter Guy, his ex-girlfriend Madeline, and his new girlfriend Ilena. Like a Nouvelle Vague film, it relies on chance encounters. Madeline is emotionally wrenched by the breakup with Guy, and we follow her efforts to find work and a new partner. Ilena’s semi-reluctant meeting with an older man who brings her home to meet his daughter reminded me of the moment in Shoot the Piano Player when Charlie, running from the thugs, falls into step beside a stranger who tells him his own troubles. And of course the title characters recall the separated lovers of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

For all its documentary textures, the film at times becomes what J. Hoberman called a Mumblecore musical. But there’s a gradual shift to the full-blown show-biz mode. Damien talked of the thrilling moment in Hollywood musicals when realistic presentation of a scene gives way to nondiegetic music and the characters leap to a new, more ethereal level. Guy and Madeline presents this transition in gradual doses.

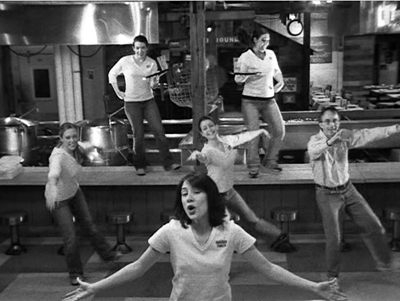

At first, the numbers are motivated realistically. Guy, an African American, plays trumpet with a jazz ensemble, so we get scenes of their performance at a local hangout. We move a bit further toward stylization with a party sequence that induces some talented kids to indulge in singing and tap-dancing among their friends—captured in casually imperfect framings.

The transition to pure musical fantasy comes forward after the breakup in a solo number, with Madeline singing a soliloquy as she wanders in the park. There’s no sense of an audience; this is a private reverie. (A whiff of this tune, heard on a car radio, makes its way into La La Land‘s opening shot.)

When Madeline takes up work at a diner, the components come together in an all-out production number addressed to us.

In an echo of Bande à part’s “Madison” sequence (lucky name), shooting a dance number in cinéma-vérité mode brings out an intriguing friction. It’s the same kind of productive clash we get on the soundtrack, between Justin Hurwitz’s shimmering Legrand-inflected score and varieties of jazz (Dixieland, Guy’s cool composition for Madeline). And like Nouvelle Vague characters, these people are devoted to books, the arts, and self-exploration.

As a “staged documentary” Chazelle’s film parallels Chronicle of a Summer in an intriguing way. That film starts as pure Direct Cinema, with investigators stopping people on the street to ask them questions. But as we get to know the group the film concentrates on, there’s a lot more control and “fictionalization.” There are precise matches on action, for instance, with camera ubiquity indicating careful restaging.

This rigging doesn’t damage the film as a document of summer 1960. Damien learned from it that you can make a truthful movie by “creating a situation with less and less acting to do.” Given this hybrid quality, Chronicle of a Summer becomes a vivid example of a moment when a film mode is “figuring itself out.” Its self-conscious artifice, which includes participants watching themselves during a screening, was foundational for the New Wave. “You watch a language being born.” That language was also political, as Damien pointed out: The film summons up memories of the Holocaust and glimpses of the Algerian war.

In other respects, Damien’s first film looks forward to La La Land thematically and formally. Guy and Madeline starts with the moment of the couple’s breakup (on the bench) and flashes back to vignettes of their love affair before returning to the bench. This opening loop is like the one that jumps from Mia’s night out back to the traffic jam and then follows Sebastian. A large stretch of each film’s plot is about how the couple’s lives converge and diverge.

Similarly, when the signature tune “I Left My Heart in Cincinnati” is played, shots of Madeline and Guy frame a flashback to the combo’s earlier performance, as if they’re sharing the memory. Something similar happens at the climax of La La Land, in what seems to be a mutual vision of Sebastian and Mia’s alternative future. As often happens in Chazelle’s cinema, epiphanies burst out in moments of musical performance.

Blood, sweat, and tears on the drumhead

Grand Piano.

Despite playing many festivals and winning critical praise, Guy and Madeline didn’t open any doors in Hollywood. Damien picked up odd jobs, not all film-related, while writing commercial genre screenplays. He sold a kidnapping script (not made) and Grand Piano (2013), skillfully directed by Eugenio Mira. He began getting assignments like The Last Exorcism Part II (2013) and he contributed to the screenplay for what became 10 Cloverfield Lane (2017), released long after he’d worked on it.

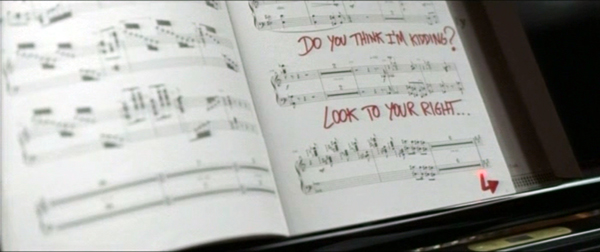

I found Grand Piano pretty impressive on the big screen. Chazelle’s script and Mira’s direction create a solid thriller built around the situation Hitchcock designed for his versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much. Most of the action takes place during a concert celebrating the return of a traumatized pianist to the stage. As he’s about to start the program, a sniper uses cellphone messages and scribbles on the score to demand a perfect performance of the florid piece that spooked the pianist years before.

At first restricted to the pianist, the film’s viewpoint widens gradually to include others, and soon crosscutting builds tension. The tormenting voice (“Play one wrong note and you die”) calls to mind the music teacher in Whiplash. As in a classic thriller, the climax arrives when the victim must fight back. And as in Whiplash, the performer wins using the only weapon he has: nearly crazed virtuosity.

Damien now thinks that the long germination of the scripts for Whiplash and La La Land made them better. As financing kept falling through, the films gained more layers. Whiplash (2014) found a home first, with Blumhouse producing and helping with the financing. It was their idea to shoot a scene to show investors (we screened it in our series), and the project found financing at Bold Films.

Given a $3 million budget and a 20-day schedule, Whiplash demanded meticulous storyboarding and very little coverage. Like Hitchcock and Leone, Damien shot only what he needed. He used two cameras for the rehearsal scenes and three for the climactic concert. The cuts and camera moves were planned to coincide with measures of the music.

Damien calls Whiplash a film about music (the same could apply to Grand Piano). It owes a lot to the sports-film genre as well; Damien envisioned its punishing force as indebted to Raging Bull. He turns big-band drumming into blunt-force trauma, with gory drumheads and cymbals. Sam Fuller would have approved.

Like Guy and Madeline and Grand Piano, Whiplash culminates in a musical performance that carries a powerful emotional impact. No wonder that as a kid Chazelle studied one-reel movies of classic drummers, then started to think of the shorts as films in their own right. In this spirit he curated for us two Dudley Murphy shorts, St. Louis Blues (1929, with Bessie Smith) and Black & Tan (1929, with Duke Ellington), along with the 1954 documentary Jazz Dance, a night on the town that explodes with pure human happiness. In all these, music-making is pushed to the edge of ecstasy.

This time around with Whiplash (good name for a movie about sadomasochistic musicians), I noticed its straightforward classical construction. Damien says that he learned screenplay construction after moving to LA. Its tale of a boy caught between a good but weak father and a punishing, strong one gains strength and sharpness from its traditional four-part plot.

At the crucial 25-minute mark, Fletcher wins Andrew’s trust. Four minutes later, in the performance of “Whiplash,” Fletcher is bellowing and Andrew is sobbing. First reversal noted. The second part, the Complicating Action, interweaves Andrew’s romance with Nicole, his persistence in drumming, and his fraught relation with his family. This part culminates at the midpoint with Fletcher’s giving Andrew a new rival, which impels Andrew to break up with Nicole. In the Development section, Andrew suffers more setbacks. A harrowing car accident leads him to botch a major competition and assault Fletcher. He leaves school, accuses Fletcher of abuse, and abandons drumming.

After he discovers Fletcher playing piano in a club, he agrees to join his new combo, which preciptates the climax: a competition performance at which Andrew, realizing that Fletcher is out for revenge, seizes control. The result is another burst of barely controlled frenzy, complete with unmotivated bursts of light spattering Andrew in the last shot.

Whiplash is a film without pity. Andrew’s rejection of Nicole suggests that he’s become obsessive, and after his scuffle with Fletcher he’s drained and numb. And no sympathy is extended to the monstrous Fletcher. Damien avoided what he called the “rubber ducky” moment that shows this man to be damaged by some childhood trauma. We get no explanation of his ruthless brutality; he’s simply a force to be fled or fought. (Damien told us that he modeled Fletcher on a music teacher he’d had; the original probably wasn’t as nasty, but Damien wanted the film to convey how frightening he was to a fifteen-year-old.)

At the end, Andrew earns a glint of triumph, but the reverse shot shrewdly withholds from us the expression that might warm us up to this man. His sliced-off smile and slight nod are all it takes for Andrew to react.

Still, his grudging approval means that Andrew has won over one scary dad.

Embarrassing yourself and your characters

At 29, Chazelle found himself with a hit, confirming the Magic Number 30 Rule. Whiplash made a splash at the Sundance Film Festival and went on to be nominated for several Oscars, winning three. It also brought in a lot more than its cost. Damien could now reignite La La Land.

Lionsgate, via Summit, picked it up and production began. There were 40 days of shooting across 65 locations. The production was able to be so efficient because of careful planning and the reliance on long takes. “The long take has become fashionable,” Damien says, who knows his film history: “But it’s actually the most old-fashioned kind of thing.” Whiplash is an editing-driven movie, but La La Land relies on many fewer shots. The moments of shot/reverse shot–notably in the spoiled dinner when Sebastian is briefly between tour gigs–gain a prominence they don’t have in most movies.

In shooting, the morning was given over to rehearsals, followed by a great many takes–often required to sync the actors to playback. Around about take twelve, Damien recalls, things started to crystallize, but sometimes as many as twenty takes were needed. While Whiplash stayed tight to the screenplay, La La Land was heavily improvised. The visuals were pre-designed, but the relationship at the center needed a casual feel, as if the characters were tossing off their lines.

Damien had thought he would simply be able to cut together the “one-ers,” but editing took five months, not least because he and his long-time editor Tom Cross played with many versions. Every number was a candidate for deletion, including the freeway opening. (Yeah, I shuddered.) There was also some digital adjustment of the 35mm original. David Koepp wrote me:

Maybe ask Chazelle about how beautifully he used color to direct our eye in his LA LA LAND opening. Always the right burst of costume color directing us to the right spot at the right time… although I guess that’s more of a compliment than a question.

Damien explained that he made those colors pop a bit more by digitally toning down other costumes in that intricate opening sequence.

La La Land has steadily grown in my regard and affection; I think it’s one of the best recent American movies. Just the title gets you going. “La la” suggests music, but also the self-absorption of jamming your ears lalalala. LA is a town of airheads, but it can become a town of worthwhile fantasy too. Damien spoke of most movies trying to make fake sets look real; he wanted to “take real stuff and make it look false.”

This time around, I was struck by the film’s harsh side. It’s pretty hard on mainstream Hollywood, from the smug partygoer who says he’s really good at world-building to Mia’s superficial roommates. Their anthem “Someone in the Crowd” is about careerism, but it becomes for her about the search for a soulmate.

Then there’s Sebastian. A lot of Hollywood plots work only if the guy is a jerk. In Whiplash, Andrew turns smug when he thinks he’s Fletcher’s pet, and he dumps Nicole heartlessly. (He’s becoming a bit like Fletcher.) In La La Land, I began to see Sebastian as a stubborn nerd, refusing to play the cocktail-bar set list and ranting about jazz to anyone who’ll listen. Ryan Gosling’s ingratiating performance makes this nerd more likable, but as written the character is pretty arrogant.

One scene that puzzled me now makes sense in a larger pattern of Seb’s obtuse, evasive behavior. After he learns he may be kept from attending Mia’s show, why doesn’t he phone her? We see him brooding outside the music studio.

He may think he can still make it in time, which would reflect his somewhat risky self-assurance. But Damien pointed out that elsewhere in the film he’s not seen using a cellphone, or for that matter a computer. Old school as he is, he seems wary of modern technology. He drives an utterly impractical Buick convertible. He plays cassette tapes and LPs and his apartment’s phone is an old-style handset, antenna and all. An omitted screenplay scene showed him in a movie audience ranting at somebody using a phone, thereby disturbing the viewers more than the caller has.

I’m being too hard on Sebastian, of course. We admire his idealism, his tenacity, and his romantic attachment to what he thinks is the best of the past. Still, Damien has remarked that he sees sides of himself in both Andrew and Sebastian, which reminds us that “commercial” films can also be personal ones. For him, the strongest creative choices risk exposing you. “If you’re not embarrassing yourself, you’re not doing your job.”

If Sebastian is too willful, Mia is too eager and desperate. “I can do it differently,” she tells the audition staff after they’ve brushed her off. Sebastian and Mia complement each other. His cockiness (“Fuck ’em”) pushes her to mount her one-woman show, while she tries to steer him back to his basic commitments. The larger theme seems to me that the most vital art comes from yourself, be it your memory of a Francophile aunt or your irrational attachment to classic jazz. Instead of having to fit into prefab TV characters, Mia gets her breakout role in a film that will build its script around her personality.

Damien spoke of the musical as Hollywood’s most avant-garde genre. That partly stems from the transition from realism to fantasy that launches a number. This shift provides the film’s final turning point, with Mia’s audition; for once a Chazelle film makes its musical climax a subdued one, but it’s no less a demonstration of the performer’s authentic emotion. Art’s power comes from novelty (“new colors to sing”) grounded in sincerity and self-awareness, even if by some standards it seems awkward and geekish.

The avant-garde overtones are also a matter of how musicals make real locations look unreal—as Demy films memorably show. So it was uncannily appropriate that Damien asked us to introduce La La Land with Bruce Baillie’s All My Life (1966). A slow pan left across a fence and flowers gives way to a diagonal tilt up to the sky; the whole accompanied by Ella Fitzgerald and Teddy Wilson.

La La Land might well be a sequel, as we tilt down from another blue sky to a gridlocked freeway.

As Baillie turns a prosaic bush and fence into an audiovisual flow, so the opening of Chazelle’s film takes the banality of a traffic jam and makes it an explosion of youthful hope and energy, complete with somersaults.

The sheer cinematic exuberance of La La Land will, I think, keep the film alive for a long time. “Every scene, a new idea”: Damien quoted Arnaud Desplechin quoting Truffaut. Many parts of La La Land put nifty tweaks on the conventions of comedy, drama, and the musical. There’s the “enacted” slow-mo at the party, the iris around a kiss, and the montage rendered as a flash-forward from a duet at the piano (“City of Stars”). There’s often a tweak on what might have been perfunctory filler. The exit-on-an-elevator shot is lit and costumed so as to (a) suggest the conformity of the dress code for an audition; (b) emphasize the height of her rivals; and (c) accentuate the spill on the less glamorous Mia’s blouse. Her disadvantages are diagrammed.

Then there’s the idea of having a “real” dream ballet at the planetarium and a virtual one at the end. Speaking of the end, I especially liked the head-fake at the start of the present-time part. By showing Mia on the Warners lot and Sebastian in his club, we’re invited to infer for a moment that they stayed a couple, before revealing that she’s actually married to an easygoing beefcake and Seb still lives alone.

Pitching La La Land, Damien found that many producers insisted that the couple unite for a happy ending. Damien objected that many of the great romantic films, including Casablanca, A Star Is Born, and Gone with the Wind, center on lost love. Still, he found a way to a happy ending by offering an alternative outcome that many viewers will prefer.

True, it’s sad. But Jacques Demy once remarked that sad movies make him happy. For me, La La Land is that sort of movie.

How much does cinephilia help a director? I’d expected Damien to recommend the sort of movie immersion he had as a kid. And he admitted the power of the past. “I can’t unwatch the movies I’ve seen.” But some great directors aren’t cinephiles, he granted. He cited Bresson and Dreyer; I thought of Ford. What’s important, he suggested, is a relation to some, any art form–if not film, then visual arts or theatre or literature.

Maybe the best of both worlds is to be a young filmmaker who knows both film and another medium, such as music, and thinks as an audiovisual artist. Damnien remarked that in writing he starts with images rather than words but then lets the dialogue focus the scene. Interestingly, Eisenstein taught his students to stage a scene first as if it were in a silent film, then revise it with music, color, and (only then) dialogue. That assured that pictorial storytelling would be foremost.

Kristin and I were gratified to hear that Damien has over the years read several things we’ve written. In turn, he taught us a lot. His visit reminded me that one path to filmmaking achievement is just thinking about your craft and your choices, in light of your life experiences and your encounters with powerful art. He passed that lesson along to the hundreds of people who came to learn from him.

Thanks to Damien Chazelle and Alissa Goldberg for making the visit possible. Thanks as well to J. J. Murphy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, Matt St. John, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Maria Belodubrovskaya, Erik Gunneson, Jason Quist, Kim Hendrickson, and Grant Delin. Event planners Kelley Conway, Jeff Smith, and above all Jim Healy, Cinematheque Director, deserve massive gratitude as well.

We have other discussion of La La Land on this site: my search for some of its roots in 1940s innovations, and my analysis of its song plot. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation among experts Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen. Jeff Smith weighed in on the film’s score, correctly predicting its Oscar triumph.

P.S. 8 March 2018: Many thanks to Steve Elworth for a correction about All My Life.

Kelley Conway interviews Damien Chazelle.