Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past

Cover Girl (1944).

DB here:

I just got my first copy of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I’m always scared to look at a published piece because I expect my eye to light on (a) a misprint; or (b) a sentence of unusual clumsiness or simplemindedness. Other writers have told me they have similar qualms. But I did look, and on this fat volume: so far, so good. It even has black, slightly corrugated endpapers, like the paper inside a box of chocolates.

This was a personal project for me, for reasons I’ve sketched elsewhere on this site. I grew up watching 1940s films on TV and have always had a fondness for what James Naremore has called “the beating heart of Hollywood.” In my teen years, watching Welles and Hitchcock movies along with B films and minor musicals fed my interest in studio cinema.

When I started teaching in the 1970s, I was keen to catch up with all those nifty movies sitting comfortably in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. My classes screened His Girl Friday (in a pirate copy) and Meet Me in St. Louis and Possessed and The Locket and White Heat and The Ministry of Fear and many more. Students working with me studied Gothics, war films, and I Remember Mama. It was then I started to realize just how creative this period was.

One piece of boilerplate for the book puts it more melodramatically.

In the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Viewers were plunged into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists. Others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes were lurching into violent confrontations.

Films were exploring parallel universes and supernatural dimensions. Characters switched bodies or intuited the future. Combining many of these ingredients, there emerged a new genre—the psychological thriller, populated by murderous spouses and witnesses who became targets of violence.

If this sounds like our cinema of today, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, David Bordwell examines for the first time the range and depth of the 1940s trends. Those trends crystallized into traditions. The Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the 1940s.

Bordwell shows that the booming movie market at the start of the Forties allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. He traces how Orson Welles, Preston Sturges, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and dozens of lesser-known creators built models of intricate plotting and psychological complexity.

Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun in the late 1930s, in radio, fiction, and theatre before migrating to cinema. And even with the late 1940s recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation could not be stopped. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, when filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analysis of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, Bordwell analyzes the era’s unique ambitious and its legacy for future filmmakers.

Today I’d like to give you some background on the book and flag a new page on this site you might find of interest. (If you can’t wait, you have permission to go there now.)

Questions, questions

Kitty Foyle (1940).

Reinventing Hollywood turned my enthusiasm for the 1940s into a set of questions.

The enthusiasm was based on a hunch that Hollywood cinema between 1939 and 1952 saw a burst of innovative storytelling. The innovations weren’t utterly new, but they differed from what was seen in the 1930s by virtue of their range, number, and complexity. The more I looked, the more I realized that the Forties recaptured the narrative range and fluidity of silent cinema, extending and nuancing it with sound. In essence, a new set of norms emerged, forged by many filmmakers.

Several questions followed. How to describe those innovations? How to chart their range and variations? How to analyze their effects—on the sort of stories told, on how viewers understood them? How did the innovations alter genres, or create new ones? How might we explain the rise and expansion of these new norms? And finally, what sort of legacy did this process of changing conventions leave to the filmmakers that followed? In all, how did various trends coalesce into a tradition?

This plan, ridiculously ambitious, at least has the virtue of originality. Most books about the 1940s concentrate on major figures—stars, producers, directors, the Hollywood Ten. Other books explain how studios or censorship or labor disputes worked. Others focus on genres such as the musical or the melodrama or the combat film. A popular option is devoted to that not-quite-a-genre film noir. These are all worthy subjects. And there’s no shortage of books seeing 40s film as a reflection of wartime or postwar America, or the geopolitics of the Cold War.

Studying narrative norms cuts across many of these common perspectives. Individuals matter, particularly ambitious screenwriters, producers, and directors striving to tell stories in unusual ways. But institutions matter too, as studio culture and writers’ associations prized a degree of originality in plotting or point of view. And narrative devices cut across genres to a considerable degree. Although flashbacks have come to be associated with film noir, they actually appear in all genres, and take on different roles accordingly.

So, 621 films later, my project has become an effort to contribute to a history of film form—the various storytelling methods that filmmakers have developed in different times and places. (In other words, a poetics of cinema.) In effect, I’m asking that the kind of appreciation people show for genres, actors, and auteurs be stretched to narrative strategies as well.

Darryl F. Zanuck, with his shrewd narrative instinct, gave me my epigraph.

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

The book in between

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

The project blended in with earlier work I’d done, particularly in The Classical Hollywood Cinema and The Way Hollywood Tells It. In a sense, Reinventing Hollywood is a bridge between those two books.

CHC, written with Kristin and Janet Staiger, traced continuity and change in the studio storytelling tradition from its inception to 1960. It analyzed how conventions of story, style, and work practices were established and maintained over the decades. The Way Hollywood Tells It suggested that after 1960, the broad conventions remained in place but were modified in particular ways.

In passing, I suggested that innovations of “contemporary Hollywood” owed a lot to experiments launched in the 1940s. The new book tries to pay off that IOU. Reinventing Hollywood asks how, within the broad conventions of classical Hollywood, particular innovations could emerge in the boom-and-bust 1940s. Many standard devices of our films today, from voice-over and fragmentary flashbacks to block construction and tricks with point of view, can be traced back to the Forties, when they were consolidated and refined.

The two earlier books also considered film technique—staging, shooting, editing, and the like. Reinventing Hollywood doesn’t tackle visual style, for two reasons. It would have doubled the book’s length, and I’ve said my say on 40s style in other work. Style shapes story, of course, and I’ve tried to take this factor into account. But I concentrate on the principles of story world, plot construction, and narration—the three dimensions of narrative I’ve outlined elsewhere.

None of these books is auteurist in basic orientation, but they aren’t anti-auteurist either. Surveying techniques in a systematic way helps call attention to adepts, middling talents, and innovators. In Reinventing, I think the interludes on Mankiewicz, Sturges, Welles, and Hitchcock show how skillful filmmakers mobilized emerging conventions in powerful ways. In effect, we reconstruct a menu of options to sense the values in picking and mixing them. For example, Citizen Kane‘s investigation plot, adorned with a dying message and a bevy of flashbacks, was a vigorous synthesis of devices that were circulating through film and other media in the late 1930s. The boldness of the effort made it influential on what followed. We get a better sense of directors’ (and writers’ and producers’) idiosyncratic strengths when we know the norms they’re working with, and sometimes against.

Reinventing Hollywood, running nearly 600 pages, makes The Rhapsodes look scrawny. But it isn’t the behemoth that CHC is. CHC could give this book noogies.

The big and the small

The Bishop’s Wife (1947).

It was hard to discuss broad trends and still probe particular cases in detail. So the chapters move from generalities to specifics in steps. Some films are merely mentioned, others described briefly, others considered at greater length, and some analyzed in depth. After a conceptual introduction and a historical panorama of Hollywood as a creative community (Chapter 1), there are chapters on flashbacks, plot construction, woven versus chaptered plots, manipulation of viewpoint, voice-over, character subjectivity, psychoanalytic plots, realism and fantasy, mystery plots, and self-conscious artifice. The conclusion looks at the impact of the period on later filmmakers.

I try to go beyond obvious observations to study the mechanics of familiar devices. So I come up with terms and concepts to pick out finer-grained tactics: the breadcrumb trail that sets up many flashbacks, block construction, hooks, switcheroos, and the like.

The chapters on particular techniques are broken by “interludes” devoted to particular movies or moviemakers. Some of these interludes involve well-known films and figures, but others look at obscure items. (Yes, The Chase is involved.) Even the treatment of Big Names tries to offer something original, as when I argue that Hitchcock and Welles pushed 40s innovations very far and sustained them throughout their later careers.

Here’s the table of contents, with small annotations

Introduction: The Way Hollywood Told It

Chapter 1: The Frenzy of Five Fat Years (Hollywood as an ecosystem)

Interlude: Spring 1940: Lessons from Our Town

Chapter 2: Time and Time Again (flashbacks)

Interlude: Kitty and Lydia, Julia and Nancy

Chapter 3: Plots: The Menu (conventions of plot structure)

Interlude: Schema and Revision, between Rounds

Chapter 4: Slices, Strands, and Chunks (alternative structural options)

Interlude: Mankiewicz: Modularity and Polyphony

Chapter 5: What They Didn’t Know Was (managing narrative information)

Interlude: Identity Thieves and Tangled Networks

Chapter 6: Voices out of the Dark (voice-over)

Interlude: Remaking Middlebrow Modernism

Chapter 7: Into the Depths (subjectivity)

Chapter 8: Call It Psychology (psychoanalytic films)

Interlude: Innovation by Misadventure

Chapter 9: From the Naked City to Bedford Falls (realism, fantasy, and in-between)

Chapter 10: I Love a Mystery (thrillers and mystery-based plotting)

Interlude: Sturges, or Showing the Puppet Strings

Chapter 11: Artifice in Excelsis (self-conscious display of conventions)

Interlude: Hitchcock and Welles: The Lessons of the Masters

Conclusion: The Way Hollywood Keeps Telling It (legacy of the 1940s)

To keep things specific, I’ve prepared eleven film clips keyed to particular analyses. Just playing the clips might give you a sense of the book’s range. They’re also fun in their own right.

No zeitgeists, please

Blues in the Night (1941).

Two last points. One bears on preferred explanations. How do we explain why cinematic innovation burst out at this particular time? Again, the book tries to pursue an uncommon path.

Many writers look to a zeitgeist—the anxieties of war, the anxieties of postwar adjustment, the anxieties of the anti-Communist crusade, any anxiety you can imagine. Instead I try to look for institutional factors shaping the films’ norms. Centrally, there are the conditions of the film industry, with its rich interplay of personnel and story materials shuttling all over the place. There are also the cinematic traditions themselves, such as plots depending on amnesia. Particularly important are the adjacent arts, including theatre, radio, and popular fiction. All these sources get modified by a process of schema and revision—borrowing something already out there but warping it to new ends. In short, instead of looking for remote causes in the broader society, I try to locate more proximate ones within the filmmaking community and the turmoil of popular culture.

Someone might argue that this just pushes the problem back a step. Don’t social anxieties surface in all these media? To this I’d argue, as I did here and here, that those anxieties are very hard to identify. Not all anxieties or concerns will be shared by a populace (viz. our current political situation). And we can’t establish a strong causal connection between them and the products of popular media—especially since media are indeed mediated, by tastemakers, gatekeepers, and the institutions that produce popular culture.

For the period I’m concerned with, James Agee noted the role of mediators in his complaints aimed at the film-as-dream sociologists of the period:

It seems a grave mistake to take [movies] as evidence as definitive, as from-the-public, as if 40 million people had actually dreamed them. Take the far simpler case of advertising art. The American family, as shown therein, is not only not The Family; it isn’t even what the American people imagines as The family. It is A’s guess at that, subject to the guesswork of his boss, which is subject in turn to the guesswork of the client. At best, a queer, interesting, possible approximation, but certainly never definitive. In movies many more people take part in the guesswork, but not enough to represent a population: and many more accidents and irrelevant rules and laws deflect and distort the image.

A movie does not grow out of The People; it is imposed on the people— as careful as possible a guess as to what they want. Moreover, the relative popularity or failure of a picture, though it means something, does not at all necessarily mean it has made a dream come true. It means, usually, just that something has been successfully imposed.

Instead of social reflection, we should expect refraction. Decision-makers opportunistically grab memes and commonplaces (the unhappy housewife, the juvenile delinquent, the returning vet) in hopes they can make something appealing out of them. They absorb those into familiar (narrative) forms. We get, then, not a “vertical” or top-down flow of social anxieties into artworks, but a “horizontal” ecosystem, a dynamic of exchange and transformation. The creators copy one another, obeying local norms while also resetting boundaries. This process includes selective assimilation of ideas thrown up by the culture, and it gets amplified by network effects, as sticky ideas themselves get copied. In other words, ideology doesn’t turn on the camera. The final film is always mediated by humans working in institutions, and both the people and the institution have many agendas.

A second point follows. Working on this book brought home to me how much film owes to other media. In a way, Forties cinema became more “novelistic” because it sought to assimilate techniques of split viewpoints, replays, inner monologue, and subjective response characteristic not so much of modernism (those were old hat by the 1940s) but of popular fiction and what we might call “middlebrow modernism.” A Letter to Three Wives (1948) attaches itself in turn to three women, each with memories of the past, with that trio interrupted by a never-seen fourth woman mockingly narrating the tale. It’s a cinematic treatment of the shifting viewpoints and personified narrative voices to be found in the nineteenth-century novel (Dickens, Collins, James) and later in genre fiction, not least in mystery tales. (It’s also a modification of the source novel.)

But you could also argue, as André Bazin did, that the 1940s saw a new “theatricalization” of cinema, with self-conscious adaptations that stressed stage conventions like the single-setting action. And of course radio supplied important prototypes for acoustic texture and first-person voice-over. Each of these devices wasn’t simply ported over to film; moving images and recorded sound gave literary, theatrical, and radio-based techniques new expressive possibilities. And all depended on the churn of people working side by side to innovate within familiar norms.

Every author discovers or remembers too late those things that should have been mentioned. Doug Holm reminded me of the dream narrative of Sh! The Octopus (1937). Jim Naremore pointed out that Rex Stout had already done my work for me in Too Many Women (1947, year of my birth), when Archie reports, “It was a wonderful movie . . . Only two people in it have amnesia.” On a different pathway, I’d love to do more research on moguls’ screening rooms as a condition of influence. (They could borrow films from rival studios without charge.) Julien Duvivier is a minor hero of my book, but only after the book was submitted did I see his L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), a perfect extension of 1940s storytelling to a French milieu.

And just recently I found a nice confirmation of the unexpected byways of the ecosystem. According to the author, the figure of the “psycho-neurotic” returning soldier was at first mandated by government policy but then twisted by ambitious screenwriters into tales of civilian madmen. The article has the enviable title: “That Psycho Story Swing Is No Cycle; It’s Now an Obsession.” If you buy the book, please write that into the endnotes.

And for the third time, feel free to visit the clips page!

I owe a lot to several people who saw this book through publication. Foremost are my editor at the University of Chicago Press, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues Melinda Kennedy and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. Then too there is Bob Davis, who supplied the book’s jacket photograph; Kait Fyfe, who prepared the clips for posting; and web tsarina Meg Hamel who set up the clips page. My other debts are recorded in the acknowledgments, but of course I must mention Kristin who had the hardest job of all. She had to put up with the author.

My Agee quotation comes from “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for Museum of Modern Art Round Table (1949),” in James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017), 975. I’m indebted to Chuck for sharing this with me. Chuck’s discussion of Agee on our site is well worth a read.

Many entries on this site are dedicated to 1940s Hollywood. See the relevant category. “Murder Culture” has been revised as a chapter in the book. On 1940s visual style, see Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style, and entries under 1940s Hollywood. There’s also the web essay on William Cameron Menzies. My most detailed arguments against social reflection and zeitgeists in historical explanations comes in the title essay in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32.

Although the Amazon page offering Reinventing Hollywood says copies aren’t available until October, it seems that copies are shipping now from Chicago’s webpage. Amazon offers no discount on the title. (See P.S.) It’s currently available only in hardcover, with a paperback planned for the distant future.

P.S. 27 Sept 2017: Actually, Amazon is now discounting Reinventing Hollywood; it’s $30.77, as opposed to the $40 list price.

P.P.S. 13 October: Amazon’s prices on the thing have been fluctuating wildly. See this entry. Those wild and crazy algorithms!

Our Town (1940).

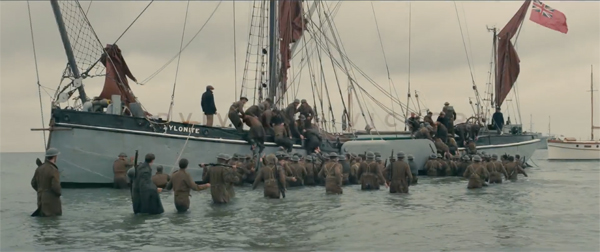

DUNKIRK Part 2: The art film as event movie

Dunkirk (2017).

DB here:

In some ways Christopher Nolan has become our Stanley Kubrick. Many directors have found ways to turn genre movies into art films; think of Wes Anderson and comedy, or Paul Thomas Anderson and melodrama. But seldom does the result become both a prestige picture and an event film.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Like Kubrick, Nolan moved from the independent realm to an assignment (Insomnia) before being entrusted with a big picture, the first of the Batman reboots. As he developed the Dark Knight trilogy, he made two films in the one-for-them, one-for-me mode (The Prestige, Inception). But Inception became his 2001, a genre hybrid (science-fiction/heist film) that proved that he could turn an eccentric “personal” project into a blockbuster. After The Dark Knight Rises, Interstellar showed that he could make an original genre film that was both prestigious (brainy, based on real science) and an event film. He became another director you want to be in business with. Warners obliged.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

True, Kubrick the former photographer is the more fastidious stylist. You can’t imagine him accepting that his film could be shown in three aspect ratios (as Dunkirk is). The Prestige shows that Nolan can be a precise pictorialist, but as I argue in our little book on his work he’s usually looser at the level of composition and cutting. What he’s interested in above all is narrative.

It’s rare to find any mainstream director so relentlessly focused on exploring a particular batch of storytelling techniques. Like Resnais, Godard, and Hong Sangsoo (a strange crew, I admit), Nolan zeroes in, from film to film, on a few narrative devices, finding new possibilities in what most directors handle routinely. He seems to me a very thoughtful, almost theoretical director in his fascination with turning certain conventions this way and that, to reveal their unexpected possibilities.

Specifically, I think, he’s interested in subjective storytelling, and how it interacts with a very traditional film technique: crosscutting. And he manages to make both fit within a genre framework.

Take Dunkirk. Spoilers ahead.

Field-stripping the war movie

In working on Reinventing Hollywood, I came to realize that the war film bristles with a lot of narrative possibilities. You can focus on a single protagonist, as Sergeant York and Hacksaw Ridge do. Or you can spread the protagonist function to two pals, three comrades, or an entire unit. Mission-team movies like Desperate Journey or The Guns of Navarone can be tightly plotted, but films about ongoing combat can be more episodic, stressing the long slog (The Story of G.I. Joe) or the need to respond to more or less random attacks (Battleground). In most variants, battles and strategy sessions alternate with relatively dead time when the grunts ponder their fate and talk about life back home. Letters from mom or photos of wives and girlfriends are a must.

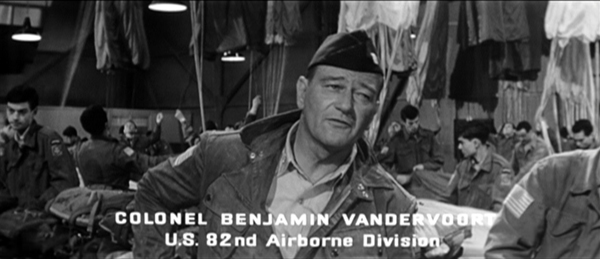

One popular subgenre is the Big Maneuver movie. In The Longest Day the Allies’ landing at Normandy is given as a panorama across nations and a trip through the military hierarchy. The viewpoint sweeps from top brass on both the Allies’ and Axis side to lower-down infantrymen, partisans, and ordinary citizens. Although A Bridge Too Far stresses the generals’ debates about what turns out to be a failed strategy, it too spends time on lower-echelon officers.

In the Big Maneuver movie, certain scenes are conventional. We see briefing rooms fitted out with maps and models of the terrain. Because the cast is vast, officers are sometimes distinguished by titles (as well as being played by instantly recognizable stars).

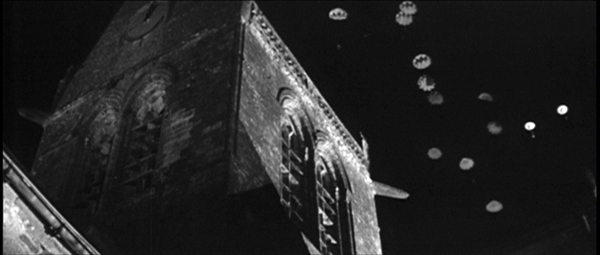

And when the film’s narration shifts to the grunts, we get quick characterizations that invoke their pasts. Early in The Longest Day, a rosary in an envelope reminds paratrooper Schultz of an incident at Fort Bragg.

Later in the film we’ll find out what this incident was, and what it says about his character.

As many critics have noticed, Dunkirk adopts the framework of the Big Maneuver war movie but it strips away many of these conventions. The only map we can examine, as Kristin mentioned, is the one on the leaflets the Germans are circulating, and for our protagonist the leaflets’ biggest value is as toilet paper. Commander Bolton and Colonel Winnaut are the only brass we see, apart from a brief visit from a Rear Admiral. More important, they’re in the thick of it, not in some safe HQ reading dispatches and pushing toy ships around tabletops.

Just as important, Nolan has purged the characters of backstory. Tommy, Farrier, pilot Collins, the French boy posing as Gibson, and Alex, the angry soldier who attaches himself to Tommy, aren’t given family or memories, nor do they display tokens of home. We don’t even know how Tommy got those scars on his knuckles. Only Mr. Dawson has a bit of a past, and that’s given us late when we learn that his son, an RAF pilot, was killed–thus giving extra motivation to his patriotic urge to help in the evacuation.

While critics complained of too much exposition in Inception, now Nolan gives almost none. In one sense, this laconic presentation is characteristic of the blank spaces we find in “art films,” where character motivation and psychology are often obscure. This is, by Hollywood standards, certainly a sparse war picture. Yet Nolan has spoken of this strategy as reworking a familiar structure. His film, he says, is all climax.

For me, this film was always going to play like the third act of a bigger film. There have been films that have done this in recent years, like George Miller’s last Mad Max film, Fury Road, or Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, where you’re dealing with things as the characters deal with them.

Kristin’s previous entry points out that in her model of classical plot structure, the film is actually both a Development and a Climax–that is, parts three and four. A Development section consists of obstacles and delays, which comprise most of the action of this film before the climactic bomber attack. Still, Nolan’s point is well-taken. In most climax sections (third acts), we know everything we need to know about the action. All the relevant motivations and backstory have been supplied in the earlier stretches, so we can concentrate solely on what happens next. In Dunkirk, we don’t see those prior sections, so we’re plunged into the prolonged suspense characteristic of climaxes.

The war movie as thriller

Granted, suspense is an ingredient of any war picture. Alongside GHQ debates about strategy, the Big Maneuver movie includes episodes aiming at momentary tension. The dive into the French village in The Longest Day offers the painful spectacle of men being shot down like a flock of geese, while A Bridge Too Far shows Urquhart (Sean Connery) trapped in a Dutch household as Nazis surround him.

Nolan’s strategy, though, is to make virtually the entire film an exercise in suspense. He understands that pure suspense doesn’t require us to like or even know a lot about the characters. We can feel tension in relation to characters we don’t like (e.g., Bruno’s reaching for the lighter in Strangers on a Train) or characters we don’t know much about at all.

Dunkirk offers a cascade of primal dangers, an anthology of narrow escapes and last-minute rescues.

The whole film is a race against time, enclosing mini-races. Nolan plays on fears of being crushed, swallowed by darkness, blasted to bits, and shot out of the sky. How many ways can you drown–in a sinking ship, under a flaming oil slick, inside a Spitfire cockpit? The appeals are elemental and irresistible; a child of five could understand the dangers here. This catalogue of stark situations takes us straight back to silent cinema, to cliffhangers, Griffith rescues, and Lang’s dungeons filling with water. Nolan points out:

Dunkirk is all about physical process, all about tension in the moment, not backstories. It’s all about ‘Can this guy get across a plank over this hole?’

Those who want films to focus only on higher things, big ideas or subtle emotions, miss the visceral dimension of cinema. It’s led critics to avoid analyzing musicals, cop thrillers, Asian martial arts films, and Eisenstein’s action sequences. (Ritual invocations of The Body notwithstanding.) The Battleship Potemkin, Police Story, The Raid: Redemption, and much other excellent cinema happily passes The Plank Test.

Does this make the film superficial? Nolan explains that even in the absence of characterization, suspense triggers involuntary, universal responses. Consider Tommy trying to run across the plank.

We care about him. We don’t want him to fall down. We care about these people because we’re human beings and we have that basic empathy.

In creating the suspense, Nolan went, as he puts it, “in a more Hitchcock direction.” That entails, for reasons we’ve talked about here and here, playing between restricted and more unrestricted point of view. Not only do we not see the GHQ strategizing, we aren’t taken into the enemy camp. From the start, when gunfire drives Tommy down the Dunkirk streets, the attacks come from offscreen. Only at the very end will a couple of blurry Nazi-shaped figures appear behind the captured pilot Farrier.

In the end, the key for me was reading a lot of firsthand accounts of the people who were there. It became apparent to me that the subjective approach — really putting the audience on the beach with the characters, putting them in the cockpit of the plane, putting them on one of the boats coming across to help — that was going to be the way to tell the story and get across this much bigger picture.

To drive home what it feels like to just barely get by, Nolan ties us tightly to Tommy the foot soldier, Mr. Dawson and his son Peter on their boat, and Farrier the Spitfire pilot, with side visits to Commander Bolton on the Mole. Sometimes he supplies optical POV shots, but more generally he simply confines us to what happens in these men’s ken. The result is both surprise–when the bullets or bombers appear–and suspense, when we cut between Tommy and other soldiers swamped below deck while Gibson struggles to open the hatch and free them.

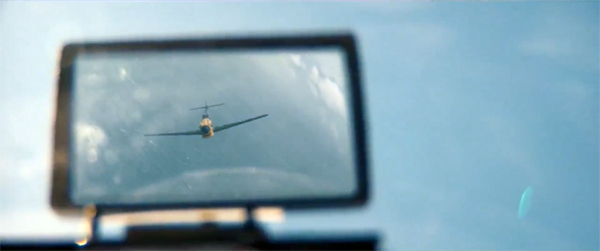

Even the clicking shut of a cabin latch–or not clicking it shut–generates tension, heightened by the ticking of Zimmer’s score. (At times I thought the pulse in my skull was synched up with the metronomic soundtrack.) The emblem of Nolan’s narrational strategy might be the pitiless shot surmounting today’s entry, showing Tommy flattened while bombs drop one by one behind him, coming inexorably closer to the foreground. Nolan turned superhero films, science-fiction films, and fantasy films into ticking-clock thrillers, and now he does it with a war movie.

The limiting of viewpoint links to some of Nolan’s perennial concern with subjectivity, I think, but it’s also there as a strain within the tradition of war fiction and film. Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front is like a diary, told in first-person present tense but with flashbacks in the past tense. Catch-22 is in long stretches tied to Yossarian’s jumbled memories of flight missions and hospital stays. Terrence Malick’s adaptation of The Thin Red Line, a film Nolan much admires, turns James Jones’ third-person novel into a lyrical fantasia on war as both a violation of nature and an extension of it, with flashbacks and brooding soliloquys. But in Dunkirk Nolan avoids the deeper registers of subjectivity he’s explored before–no memories, no dreams or fantasies, just brute happenings and the stubborn physical demands of earth and rock and water.

The viewpoint range isn’t as narrow as I’ve suggested, though. Nolan broadens his scope by cutting back and forth among the subjective stretches. Again, this is standard operating procedure in the Big Maneuver film. But that crosscutting was never like this.

Time out from battle

Dunkirk, sans credits, runs a little more than 99 minutes and consists of around 99 sequences. It’s very fragmentary. But then, so is a lot of war fiction. All Quiet consists of many fairly short scenes. Evelyn Scott’s vast novel The Wave (1929) surveys the US Civil War through over a hundred vignettes of the home front and the battlefront, involving characters mostly unaware of each other. William March’s Company K (1933) consists of 113 short segments, each bearing the name of one soldier and told in first-person by him (even if he dies in the course of the episode). Unlike what happens in The Wave, the men are mostly known to one another, and some actions are replayed through different viewpoints. A fancier sort of fragmentation goes on in Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (1948), which interrupts its scenes with flashbacks (“The Time Machine”) and sections called “Chorus.”

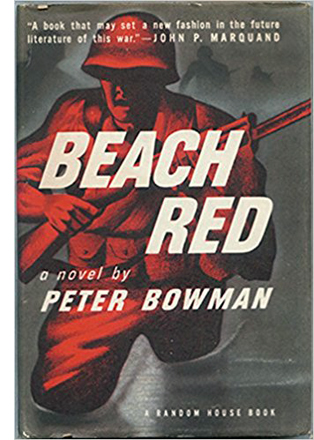

T he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

His novel is in blank verse, in stanzas of varying length but all conforming to a strict pattern. Each line is equal to one second of story time. Each chapter consists of sixty lines, or one minute of story time. And the book has sixty chapters, representing the hour in which the forces take the beachhead. Like Nolan, Bowman wants a deep, visceral subjectivity, and he aims at this through a frankly mechanical layout of his text. The rigid pattern seeks to force the reader to sink into time. Bowman explains:

I have tried to create a mood of inexorable regularity that would correspond to the subtle tyranny of the military timetable. . . . I have attempted to do for the eye what the ticking of a clock accomplishes for the ear. . . the relentless inflexibility of time itself.

The aching inching forward of time is stressed thematically too, which includes reflections like “Would there be armies if clocks had never been invented?” The book ends with the second-person narration (“You”) dying. Soldier Whitney reports: “There is nothing moving but his watch.”

Like Bowman, Nolan is interested in both the psychology of time and the problem of representing it in his artistic medium. I maintained in our book on Nolan that he isn’t only interested in shuffling chronology. I think that he’s particularly keen on exploring what the technique of crosscutting does to story time.

He has explained that he got the idea from Graham Swift’s 1983 novel Waterland.

It opened my eyes to something I found absolutely shocking at the time. It’s structured with a set of parallel timelines and effortlessly tells a story using history–a contemporary story and various timelines that were close together in time (recent past and less recent past), and it actually cross cuts these timelines with such ease that, by the end, he’s literally sort of leaving sentences unfinished and you’re filling in the gaps.

Crosscutting would become a central artistic strategy for Nolan, a way of shaping his other storytelling choices.

Admittedly, what strikes you first about Memento is its flagrant exercise in reversing story order. But that 3-2-1 sequencing is accompanied by a counterpoint, that of chronologically advancing time, 1-2-3 in the present. Backwards-moving sequences are crosscut with forward-moving ones. Likewise, the structure of Following stems from treating phases of a single action as different story strands which can be crosscut. And the shuffling of order in The Prestige comes from intercutting stretches of two characters’ lives in complicated polyphony.

In his last three films, I think that Nolan, intuitively or deliberately, has hit upon an important feature of conventional crosscutting. Nearly all crosscutting in fictional cinema presumes different time spans, or rather different rates of change, in the crosscut lines of story action. We presume that overall the actions are simultaneous, but at a finer level, they proceed at different speeds. Some parts of the action in one line are skipped over, while other actions in another line are prolonged.

This disparity can be seen in some of Griffith’s classic sequences. In The Birth of a Nation, the black soldiers are inches away from breaking into the cabin’s parlor while the Ku Klux Klan is riding to the cabin, but the riders are miles away. If both strands were on the same clock, the Klan would arrive much too late.

Crosscutting allows Griffth to skip over the distance that the Klan covers, so the riders arrive at the cabin “implausibly” fast. Correspondingly, the glimpses we get of the cabin stretch out the action “unrealistically.” To put it technically, we get ellipsis in one line of action, expansion in the other.

Nolan does the same thing in his crosscut sequences. Consider the passage in The Dark Knight when the judge opens the Joker’s fake message. One or two seconds in her timeline are stretched while Gordon’s conversation with Commissioner Loeb runs on a different clock, consuming several seconds. And when Harvey Dent talks with Rachel and is grabbed by Bruce, that action takes even longer.

To speak of different clocks is a bit misleading; we can’t think that the judge turns over the envelope in super-slo-mo. But the idea of different rates of unfolding is useful because it reminds us that crosscutting aims to convey an overall impression of simultaneity. When we look closer, we realize that the action in one story line can be slowed or accelerated while another story line is onscreen.

Nolan’s interest in this quality of crosscutting is literalized in Inception, in which embedded dream actions unfold at different speeds on different levels. In Interstellar, cosmology motivates crosscutting between slow and fast rates of change. In the first planet the astronauts visit, one hour is equal to seven years on earth, so characters literally live at different rates. The pathos of the film depends upon the fact that Cooper returns, barely aged, to his daughter, to find an old woman on her deathbed. But the differential also allows Cooper to appear to her as the ghost that she saw in childhood and, in circular fashion, set him off on his mission.

The war movie as puzzle film

Nolan notes for Interstellar.

For Dunkirk, Nolan found another way to highlight the rate differences secreted within crosscutting. Like Bowman in Beach Red, he lays down crisp time markers. Farrier’s combat sortie lasts one hour; Dawson’s rescue efforts at sea last one day; and events around the breakwater (the Mole) are said to consume one week. The actual evacuation ran longer, but Tommy and his pal aren’t the last to leave.

These three stretches of action could have been presented as separate blocks. We might have been attached first, say, to Dawson and his boat to attain a pitch of excitement during the bombing of the minesweeper. Then we could flash back to Tommy at the start, in a long lead-up to being rescued by Dawson. Finally we could cover the same events yet again by starting with Farrier’s aerial combats and tracing his fate. The film could have concluded with an epilogue showing Tommy and his pal safely on the train.

Interestingly, Kubrick explored this creative option to a limited extent in The Killing, his 1955 adaptation of Lionel White’s Clean Break. As in the novel, one string of scenes sticks with one participant in a racetrack robbery. Then we jump back in time, guided by a voice-over narrator (“About an hour earlier…”) and follow another man leading up to the situation we’ve already seen. Tarantino did the same block-shifting in Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown, and he (rightly) noticed it as a standard literary technique.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action. . . . Flashbacks, as far as I’m concerned, come from a personal perspective. These [in Reservoir Dogs] aren’t, they’re coming from a narrative perspective. They’re going back and forth like chapters.

But Nolan avoided block construction and went for braiding. He splintered his story lines and crosscut them. Events that are mostly taking place at different times are, as it were, laid atop one another and offset. Crosscutting en décalage, we might say.

I’m struck by how bold this is. A more conventional choice would be to confine the action to a fairly brief stretch of time, say two hours, with the rescue fleet arriving at the climax. There might even have been an effort to handle the action as occurring in “real time,” that is, with the duration of the scenes matching their duration in the story. In any event, Nolan could have crosscut his four men–Farrier in the air, Dawson and others at sea, Bolton and Tommy around the Mole–at the points when their activities are roughly simultaneous. If Nolan wanted to include earlier incidents, such as Tommy’s escape from the Germans or his efforts to board the Red Cross ship, those could have been presented as personalized flashbacks. Instead, all that material appears in chronological scenes, but on three distinct time scales.

Nolan set himself enormous problems with this choice. He chose to show the time frames without recourse to an onscreen calendar or clock; after the three initial titles indicating the places and the time spans, we get no more explicit markers. Then Nolan faced the problem of how, on a finer-grained level, to gather these fragments into a whole. He had to create parallels, and, eventually, convergences.

So early in the film, Tommy and Gibson run a stretcher to the departing Red Cross ship.

Cutting makes their urgency flow into that of Mr. Dawson hastening to cast off before the navy requisitions the Moonstone.

Forty-five seconds later Farrier’s team is sent to Dunkirk.

In story time, of course, these aren’t simultaneous at all. Tommy’s attempted escape happens days ahead of Mr. Dawson’s departure, which is hours ahead of Farrier’s mission. But Nolan, aided by Hans Zimmer’s endlessly propulsive score, has given all three primary roles in launching the film’s plot, the start of a time-gapped fugue.

That sort of primacy works at a higher pitch when two life-or-death situations are intercut. Tommy, Alex, and some other soldiers have rashly taken shelter in a fishing trawler, hoping that the tide will carry them away from the beach. But they get pinned inside by target fire. The tide has indeed pulled them out to sea, but the hold is taking on water–at the “same time” (not) that Collins, trapped in the cockpit of his ditched plane, is himself about to drown. The two scenes are intercut.

At the climax, the gestures of rescue are exuberantly crosscut: Dawson hauling on the oily survivors of the blasted minesweeper, the civilians helping the stranded soldiers clamber aboard their boats.

In this passage, Nolan daringly cuts single shots of Dawson’s Moonstone moving as if in sync with the impromptu flotilla, even though he’s some distance off; the crosscutting makes him visually one of the fleet near the Mole.

Crosscutting can also dial up the suspense by delaying the outcome of a line of action. Farrier’s dogfights are pretty much incessant, so cutting away from them to more placid action on the beach or in Dawson’s boat postpones their outcome. Nolan points to another advantage of intercutting the different periods:

You have three different intertwined storylines, and you have them peaking at different moments, so that the idea is that you always feel like you’re about to hit–when you’re hitting the climax of one episode of the story . . . then another one is halfway through and the other one is just beginning. So there’s always a payoff.

Nolan compares this to the “corkscrew” effect of the Shepard Tone in music, which David Julyan used in the drone soundtrack of The Prestige.

At other points, the crosscutting uses one line of action to explain another. While Tommy and Gibson take refuge in the second ship, the Shivering Soldier tells Dawson he refuses to return to Dunkirk because his ship was hit by a torpedo. Soon enough we see a torpedo rip open the ship and plunge Tommy, Gibson, and Alex into the night sea. And soon after that, when they try to clamber into a lifeboat, they’re told by an officer to stay in the water: it’s the Shivering Soldier, pre-PTSD. The contrast between his cool efficiency near the Mole and his spasm of cowardice on the Moonstone is another proof of war’s disastrous impact on warriors.

The lines of action, segregated by crosscutting, intersect eventually. Farrier’s teammate Collins ditches his plane and is rescued by Dawson; later Tommy will get on the Moonstone as well. These are staggered a bit in the film’s unfolding, having the effect of replays. At at least one point, though, I think that all three lines converge. One moment unites Farrier shooting down the German bomber, Dawson steering his ship away from the falling plane, and Tommy, dragged along underwater and hauled to the deck. Shortly the realms of Air and Mole converge when Bolton sees the German plane go down and his men cheer Farrier’s plane as it glides past.

After these moments are briefly pinned together (the script calls it the “confluence”), the time scales diverge again. The epilogue phase of the film resets each strand’s clock. The rescued men arrive at Dorset, and Tommy and Alex board a train at night. Back at the Mole, it’s still daylight and we can see Farrier’s plane burning in the distance. A day or so later in Dorset, the newspaper has published a tribute to George. Now we see Farrier days before, still within his allotted hour of story time, guide the plane down, step out, and set fire to it, as Tommy reads from Churchill’s speech.

Three viewings of the film weren’t enough for me to catch all the alignments, shifts, and echoes, the glimpses of things that take on importance only retrospectively. Early on, a distant shot of Collins’ downed plane briefly shows what turns out to be the Moonstone chugging towards it. On first viewing I was puzzled by Farrier’s view of a sinking private ship; only on the second pass did I realize that it’s the blue trawler that we’ll later see the young soldiers hiding in and fleeing from. And it’s likely, even with many pages of notes, that I’ve mistaken some of the juxtapositions that fly by. (The film averages about 3.3 seconds per shot, and sometimes we jump across story lines in a fusillade of alternations.) Like other puzzle films, the film demands rewatching and scrutiny, and it merits it.

In all, Nolan has taken the conventions of the war picture, its reliance on multiple protagonists, grand maneuvers, and parallel and converging lines of action, and subjected it to the sort of experimentation characteristic of art cinema. (As, in a way, Bowman’s time-grid in Beach Red anticipates the rigor of the Nouveau Roman.) Nolan exploits one feature of crosscutting: that it often runs its strands of action at different rates. He then lets us see how events on different time scales can mirror one another, or harmonize, or split off, or momentarily fuse. As a sort of cinematic tesseract, Dunkirk is an imaginative, engrossing effort to innovate within the bounds of Hollywood’s storytelling tradition.

The juxtapositions aren’t just fancy footwork, I think. In this film, because of the imminence of danger, heroism gets redefined as luck and endurance.

A cynic could call the movie Profiles in Cowardice. Tommy flees German bullets and instead of helping the French hold the barricades, he keeps running. The French boy steals boots and an identity in order to get off the beach sooner. He and Tommy try to slip on board a departing Red Cross ship as stretcher bearers. When that fails, they hide among the pilings. When the ship is hit, they leap into the water, the better to pretend to have been among the survivors and get a new ride. The Shivering Soldier wants to cut and run, and the soldiers who drift beyond the perimeter plan to use the blue trawler to carry them to safety, jumping the evacuation queue. All too often, despite acts of aid and comfort, it’s every man for himself.

At one point Alex claims “Survival’s not fair.” Too right. Mr. Dawson risks his and his son’s life to save a few men, while the lad George, who joined them on impulse and promised to be useful, dies before he can do much, accidentally killed by the Shivering Soldier. The closest the film comes to standard war-movie heroics is Farrier’s cutting down Stukkas. And he doesn’t make it back.

By plunging Tommy and his counterparts into almost unremitting peril, Nolan’s suspense tactics lower the bar for heroism, making us hope that they simply get away, somehow. Trapped on land and sea, you can’t fight dive bombers, U-boats, and marksmen squeezing in from the perimeter. At the end, the boys disembarking at Dorset are reassured that survival was enough. And thanks to Nolan’s crosscutting, individuals at different points in time are shown pulling together to make retreat its own victory.

I wrote nearly all this entry before I got a copy of the published screenplay. Reading Nolan’s conversation with his brother there enabled me to add the quotation about catching lines of action at different points (p. xxii). This conversation also considers the reasons Nolan omitted GHQ scenes (mentioning A Bridge Too Far) and adds comments about Hitchcock, early sound filming (some mistakes here), and The Thin Red Line (“maybe the best film ever made,” xiii). As far as I can tell, the screenplay is fairly close to the finished film until the climactic bombing of the minesweeper; at that point, the onscreen editing doesn’t completely match what’s on the page.

Speaking of climaxes, I should add that even though the film is in Nolan’s sense “all climax,” it also falls quite nicely into Kristin’s four-part structure. I think the midpoint comes when Tommy and his mates head to the blue trawler, starting a typical Development section.

My quotation from Tarantino comes from Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (New York: Applause, 1995), 69-70. The Nolan quotation about Waterland comes from Jeff Goldsmith, “The Architect of Dreams,” Creative Screenwriting (July/ August 2010), 18-26 (available, sort of, here).

On the tendency of war novels to play with time, it’s worth mentioning that Catch-22 may exemplify one weird possibility. The Yossarian plotline slips between past and present very fluidly, with some sentences containing several jumps to and fro. The Milo Minderbinder plot is linear, tracing Milo’s building of his empire in 1-2-3 order. But Milo’s progress appears at different moments in past and present in the Yossarian strand, so some critics have argued that the novel has a deliberately impossible time scheme. See Jan Solomon, “The Structure of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22” (1967) and, for rebuttal, Doug Gaukroger, “Time Structure in Catch-22“ (1970). Even if Catch-22 doesn’t actually do this, it remains a creative option that someone should try. Mr. Nolan?

Is the name of Dawson’s boat, the Moonstone, an homage to Wilkie Collins’ 1868 mystery novel? Collins tells the story through different character viewpoints and skips back and forth in time, using replays that gradually explain what’s going on. Mr. Nolan?

For more on block construction, especially in the work of Tarantino, see this entry. You can find more of our thoughts on Nolan’s work in our book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages (with lots more about crosscutting). See also our blog entries on Inception (here and here), “Superheroes for Sale,” and “Niceties,” and our online article (originally in Film Art) on sound in The Prestige.

Dunkirk (2017).

Ritrovato 2017: Drinking from the firehose

DB here:

Immense scale and teeming activity are nothing new to Il Cinema Ritrovato, the Cineteca di Bologna’s annual jamboree of restored and rediscovered films from all over the world. The scorching heat–90 degrees and more for the first few days–only makes it seem more intense than usual.

Kristin and I had to miss the last Ritrovato session, but we’re convinced that this nine days’ wonder is still the film-history equivalent of Cannes.

In one way, your choice is simple. You can follow one or two threads–say, the Robert Mitchum retrospective or the Collette and cinema one or the classic Mexican one, or whatever–and dig deep into that. Or you can skip among many, sampling several, smorgasbord-style.

In practice, I think most Ritrovatoians pursue a mixed strategy. Settle down one day for a string of, say, early Universal talkies and another day check out the restored color items. On off-days roam freely. The problem is you will always, always miss something you would otherwise kill to see.

At the start, I plumped for 1910s films, particularly Mariann Lewinsky’s reliable 100 Years Ago cycle. My other must was the Japanese films from the 1930s; half of the titles brought by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, were new to me. As of this writing, I haven’t seen those, but I have dug into the 1917 items. And I indulged myself with, no surprise, some gorgeous Hollywood things.

1917 and all that

Malombra (1917).

If you caught any of my dispatches from Washington DC earlier this year (starting here) you know I was burrowing deep into American features of the 1910s That complemented several years of archival work on European films of the same period. So of course the chance to sample 1917 features from Hungary, Poland, Russia, and elsewhere was not to be passed up.

Some superb ‘teens films I just skipped through familiarity. Gance’s Mater Dolorosa (1917), possibly the most patriarchal film in the thread, remains tremendously inventive at the level of silhouette lighting and continuity cutting (a huge variety of camera setups during the fatal love tryst). And one of the very greatest directors of the period, Yegenii Bauer, was represented by two of his last films, The Revolutionary and Towards Happiness. I’ve studied both elsewhere, in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and online. Even so, I found plenty to keep me busy.

One of the main threads was devoted to Augusto Genina, a director with an astonishingly long and prolific career. Probably best known for Prix de Beauté (Miss Europe, 1930), he started in 1913 and made his last film in 1955. His 1910s films confirm that Italy was producing many films of striking beauty and audacity in those years.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

In a similar vein is Addio, Giovenezza! (1918), adapted from a popular song. This one, screened in an open-air venue thanks to an arc-lamp projector, is another sad Genina tale. A careerist law student abandons his rooming-house maid for a social butterfly with a wardrobe to die for. Apart from one startling scene in a milliner’s shop, illuminated mostly by spill from the street, the lighting isn’t as daring as in Lucciola. Still, the poignant plot is again inflected by comic touches, proceeding largely from the hero’s nerdish fellow student. Genina redid the story again in 1927, and I’m hoping to catch that screening.

Malombra (1917), starring the diva Lyda Borelli, was by the great Carmine Gallone. (I’ve discussed La Donna nuda and Maman poupée hereabouts.) After moving into a castle, Marina becomes possessed by the spirit of the woman who died there. Our heroine’s job is to take revenge on the faithless husband. Flirtatious and iron-willed, Borelli dominates her scenes with shifts of stance, sudden freezes, rapid changes of expression, languorous arm movements, and, at one climax, a swift undoing of her hair that lets it all tumble wildly around her face. The print, needless to say, was superb.

In a lighter vein, if you wanted proof of the inventiveness of ‘teens Italian film, you couldn’t do better than Wives and Oranges (Le Mogli e le arance; 1917). This agreeably silly movie sends a bored young man to a spa populated by incredibly aged parents and a bevy of scampering daughters. With an avuncular friend, Marcello capers with the girls before settling on the most modest one as his wife. But her friends aren’t disappointed because our hero’s pals come for a visit and get roped into matrimony too.

Wives and Oranges has a remarkable freedom of narration. The film uses montage sequences with a fluidity that is rare at the time. To convey the boredom of Marcello’s daily routine, a string of quick shots is punctuated by changing clock faces. Later, the idea of finding one’s ideal love mate by matching halves of oranges is presented via an absurd montage of old folks, youngsters, babies, and just abstract hands, all wielding oranges.

Marcello’s paralyzing dilemma of choice is given as a nondiegetic insert of a donkey unable to decide between a hay bale and a bucket of water. These flashy devices keep us interested in a situation that, in script terms, is probably stretched too thin–although when things slow down you can count on the daughters forming a chorus line and zigzagging down the road or popping out from under the dinner table one by one.

Almost as lightweight was The War and Momi’s Dream (La Guerra e il sogno di Momi, 1917), by the great Segundo de Chomón, who moved among France, Spain, and Italy making fantasy films of many types. This one is largely meticulous puppet animation, in which a boy’s toys come to life and enact–at the height of the World War–their own combat.

Trick and Track marshall other toys to play out some seriocomic clashes, including a burning farmhouse and one astonishing shot of an entire town landscape, covered in a long camera movement. Again, there’s no underestimating the sheer technical audacity of Italian cinema of these days.

There’s always an exception, of course. The late David Shepard left us, among much else, Shepard’s Law of Film Survival: The better the print, the worse the movie. A good example is La Tragica fine di Caligula Imperator (1917), signed by Ugo Falena. It’s surprisingly retrograde for an Italian film of the period. Neither the staging (flat, distant) nor the cutting (minimal) nor the lighting (little modeling) is much in tune with contemporary norms. The problem may be the immense sets, which are indeed impressive but which seem to encourage the actors to a hard-sell technique.

The most amped-up is Caligula himself. Playing a mad Roman emperor often tempts any actor to gnaw table legs. But as an example of what a silent film really could look like, Caligula should be required viewing for anybody who sneers at Those Old Movies. If Christopher Nolan saw it, he’d demand to shoot on orthochrome nitrate.

Other 1917 features included The Soldier on Leave, from Hungary, and Stop Shedding Blood!, by the great Russian director Jakov Protazanov. The former was restored from a 17.5mm copy, the latter was missing the two central reels. The Protazanov in particular had some sharp staging in depth and rich sets.

In the same batch was Pola Negri’s screen debut in Bestia (1917, imported to the US as The Polish Dancer). In a fine copy, you could appreciate the bouncy but sultry screen presence that made her a star. And as often happens with films from anywhere in this period, the sets sometimes play peekaboo with the action. Pola, after a night out with her thuggish lover, sneaks back to her bed while her father snores in the background, caught in a slice of space.

Back in the USA

Kid Boots (1917).

The 1917 American entry was a strong, unpretentious Western by Frank Borzage, Until They Get Me. It’s missing some scenes in the middle, but it remains a forcefully quiet movie. The only gunplay takes place at the start, when a man racing to get to his wife in childbirth is forced into a gunfight. He kills the drunkard who provoked it, but by the time he reaches his home, his wife is dead. Now he must flee Selwyn, a mountie. Stealing a horse, he picks up an orphan girl fleeing an oppressive household. The rest of the film will intertwine the fates of the three, leading to a surprisingly civilized resolution.

Borzage is one of the many great directors–De Mille, Dwan, Walsh, Ford, Brown, King, Barker–who started doing features in the mid-teens. Most had long careers. They mastered the emerging norms of Hollywood continuity cinema and learned to deploy them with tact and precision. Just the timing of the reaction shots in Until They Get Me is worth study.

Frank Tuttle started in features a bit later, in 1922, but Kid Boots (1926), my first movie of the Ritrovato, showed complete mastery of comic storytelling. Eddie Cantor, a fired tailor, becomes amanuensis to Tom Sterling, a man-about-town in the throes of a divorce. The twist is that his wife, learning of Tom’s new inheritance, wants to halt the divorce by sharing his bed again. Eddie’s job is to keep the wife and the lawyers at bay until the divorce becomes final. Into this tangle plops perky Clara Bow in her first film after her breakout role in Mantrap (also 1926). You could watch her cock her chin and roll her eyes for hours. She steals the picture from Billie Dove.

The gag situations come thick and fast, with one high point being Eddie’s efforts to get Clara jealous by recruiting a strategically open door to help him pretend that his left arm actually belongs to Tom’s seductive wife. The whole thing culminates in a breathless chase on horses along a treacherous mountain pass. Eddie and all the others keep things lively, and Tuttle’s direction is exacting.

I strayed from the ‘teens again at Dave Kehr’s urging. Of Dave’s magnificent MoMA restorations, I caught William K. Howard’s Sherlock Holmes (1932). Apart from a wild-eyed Ernest Thesiger and an imperturbable Clive Brook, it boasts an abstract opening of silhouettes and confrontational close-ups and a conclusion of percussive flashes as Moriarty’s gang torches its way into a bank.

Ace cinematographer George Barnes had a field day with this one.

That was followed by Tay Garnett’s Destination Unknown (1933), a tense drama of a crisis on a bootlegging ship immobile on a windless sea. Hard, fast playing by Pat O’Brien and Alan Hale was offset by the leisurely presence of none other than Ralph Bellamy, aka Jesus of Nazareth. Don’t ask; just see it.

More from me, and Kristin, later in the week.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for a great deal of assistance on this entry. Thanks as well to the programmers and staff of the festival, especially Gian Luca Farinelli and Mariann Lewinsky.

The Ritrovato site is constantly updated. For our earlier Ritrovato communiqués, go here.

Malombra (1917; production still).

Grand motel

One Crowded Night (1940).

DB here:

If this blog got into the business of recommending movies to watch on TCM, I’d never get any sleep. TCM, an American treasure, runs so much classic cinema of great value that I can’t keep up.

Today, though, as we’re about to depart for Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I’m pausing to knock out a brief entry urging your attention to a minor release that exemplifies some of the trends I try to track in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. The film is no masterpiece, but it’s better than most of the stuff pumped into our ‘plexes, and it can teach us a lot about continuity and change in the studio years.

A few hours in Autopia

In trying to map out the storytelling options developed in the 1940s, I ran into one trend that looked forward to today’s network narratives. I use that term to pick out films that build their stories around the interaction of several protagonists connected by social ties (love, friendship, work, kinship) or accident. Nashville, Pulp Fiction, and Magnolia are some vivid prototypes. The most common form of network narrative back then was based on the Grand Hotel idea, where a batch of very different characters interact in one place for a short stretch of time.

The form comes into its own in the 1930s, as I’ve indicated in a blog on Grand Hotel (1932). That novel/ play/ film popularized the concept, and MGM ran with it under the banner of the “all-star movie.” It was picked up in other 30s films of interest, like Skyscraper Souls (1932, often run on TCM) and International House (1933). But whereas Grand Hotel was a big A picture, most of its successors were B’s—perhaps because such a plot offered an efficient way to use contract players in a short-term project.

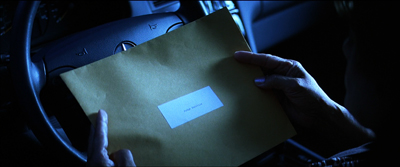

I suspect that’s what happened with One Crowded Night (1940), to play on TCM this Thursday, 22 June (7:30 EST). Dumped in the summer doldrums (back then, summer wasn’t a big moviegoing season), it garnered pretty unfavorable reviews. The big complaints were about the coincidences that get piled on. Wrote Bosley Crowther:

The long arm of coincidences does some powerful stretching for the convenience of film stories, but seldom has it been compelled so such laborious exercise as it is in RKO’s “One Crowded Night,” which opened yesterday at the Rialto. In a manner truly phenomenal, it drags together the assorted characters implicated in a multitude of small plots and dumps them, of all places, in a cheap tourist camp on the edge of the Mojave Desert.

It is pretty far-fetched. The Autopia Court, a speck on the flat, hot expanse, is run by a family whose main breadwinner, Jim, has gone to jail. He’s innocent, framed by Lefty and Mat—who show up by chance at Autopia. Meanwhile, a pregnant Ruth Matson gets off a cross-country bus to recover from heat stroke; she’s on her way to San Diego to meet her husband, a sailor.

Things get complicated fast. A trucker who comes through regularly wants to marry an Autopia waitress with a shady past. One of the thugs makes a play for the naïve waitress who’s fed up with this flea-bitten joint. But she’s worshipped by the gas jockey, who’s no match for the city hood.

The interweaving of lives is very dense. Guess who shows up, recently escaped from prison up north? When two detectives come through guarding an AWOL sailor, imagine who he turns out to be? And what if Doc Joseph, an amiable old fraud peddling a potion that cures everything, turns out to lend a helping hand?

No coincidence, no story. And especially in Grand Hotel plots, when people keep running into each other at just the right moment. Films aren’t about reality; one of the damn things is enough. Films are about giving us experiences, and this B picture seems to me quite satisfying—not least because it shows a relaxed but smooth pace almost completely unknown to modern cinema. It’s no small thing to tell so many stories in 66 minutes.

How work looks

Budget-challenged RKO makes a virtue of its limits. The film has a bleached, suffocating squalor. Dust and glare rise up. The outdoor set makes the motel complex look plausibly cheap. The diner is knotty-pine, and as dingy as you could ask. The countertop yields a solid thump when a plate of comfort food hits, and it’s easy to imagine it being gaumy to the touch. Greasy smoke sizzles up from a grill, blurring a poster advertising the good life and a cola that promises “Keep Cool.” And the shot of the disgruntled fry cook Annie owes nothing to pin-up standards.

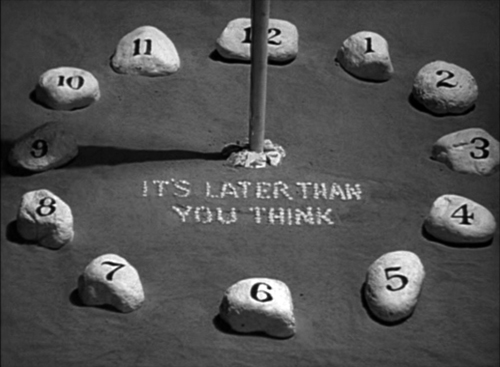

The film has that easy familiarity with the routines of working life celebrated by Otis Ferguson, who praised another film for its “reduction of the rambling facts of living and working to their most immediate denominator, to the shortest and finest line between the two points of a start and a finish.” We watch the Autopia staff briskly feed a busload of people during a ten-minute layover, fix up guest rooms, pour beers, wash dishes, scrub countertops, and pump gas—all the while an enigmatic sundial insists “It’s later than you think.”

With over twenty speaking parts, the film relies on swift, sharp characterizations. It’s lifted above the ordinary by the presence of the splendid Anne Revere, Hollywood’s embodiment of plain-speaking dignity, and the reliable Harry Shannon (aka father to Charles Foster Kane). Beloved blowhard J. M. Kerrigan plays the mountebank. Even a sweat-glistened Gale Storm (older boomers will remember her as TV’s My Little Margie) doesn’t do badly. The presence of so many character actors and bit players gives these people a worn solidity far removed from A-picture glamour. Everybody, young and old, looks fairly ill-used.

Irving Reis joined RKO after a brief but distinguished career in radio, where he created the much-lauded Columbia Workshop. One Crowded Night was his first screen credit at the studio. Renoir gets, deserved, credit for using deep-space compositions to suggest life lived in the background and on the edges of the shot’s main action. Reis, like many unheralded American directors, does the same thing. Network narratives encourage these juxtapositions, as story lines crisscross and characters react accordingly.

Reis went on to do more B pictures, as well as The Big Street (1942) and Hitler’s Children (1943). His later work includes Crack-Up (1946), All My Sons (1948), and Enchantment (1948; discussed hereabouts). He died young, in 1953. One Crowded Night shows him an efficient craftsman; Variety praised him for “development of the story’s many characters and juggling them through the many-sided yarn without confusion.”

The Grand Hotel formula would continue through the 1940s in Club Havana (1945), Breakfast in Hollywood (1946), and other low-end items. It would also yield a few A pictures, like Week-End at the Waldorf (1945, an explicit redo of Grand Hotel), Hotel Berlin (1945), and the hostage thriller Dial 1119 (1950). The format would go on to have a long life, right up to The Second-Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2015).

One Crowded Night, apart from its quiet virtues, served my book as a good example of just how pervasive certain models of storytelling became in the 1940s. Alongside the classic plot patterns of the single protagonist and the dual protagonist (often a romantic couple) other possibilities got explored. Some, like the Grand Hotel model, had been floated in the 30s and got revised in the 40s. Others took off on their own. All left a legacy—let’s call it a tradition—for the filmmakers who followed.

Thanks to TCM and its programmers for making this and thousands of other films available. But why not a version on Warner Archive DVDs? The Spanish DVD is pricy.

My quotations from Bosley Crowther come from “The Screen: At the Rialto,” The New York Times (27 August 1940), 17. The Daily Variety review appeared on 29 July, 1940, 3. Ferguson’s remark, on Joris Ivens’ New Earth, comes from “Guest Artist,” in The Film Criticism of Otis Ferguson, ed. Robert Wilson (Temple University Press, 1971), 126. For more on Ferguson, see my book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

Paul Guilfoyle and Anne Revere in One Crowded Night.