Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

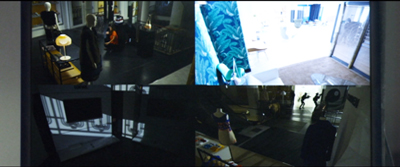

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.

Movies in the mountain, and on the machine

DB here:

I’m back in Madison from 2 1/2 months in Washington, DC. under the auspices of the John M. Kluge Center, where I was this year’s Chair of Modern Culture. This kind appointment allowed me to pursue my research into 1910s American film style, than which nothing could be more fun. Along with that were some extramural activities. The most spectacular one was our Kluge field trip into the most overwhelming media archive in the world–the bulging-biceps caped crusader of film, TV, and sound preservation.

Treasures under Mount Pony

Dr. Strangelove could have come up with the idea. If the Russians attack the US, better have a deep underground vault for storing a few billion dollars to replenish currency supplies on the East Coast. So in the Culpeper, Virginia countryside build a gigantic secret bunker. Include facilities for housing 500 or so personnel to keep the government, or what was left of it, running for a month. Add amenities like a pistol range and refrigeration units to cool cadavers that couldn’t be buried outside. Getting assigned here in nuclear winter would definitely count as subterranean homesick blues.

This super-secret complex was completed in 1969. It boasted foot-thick concrete walls and was surrounded by barbed wire and machine-gun nests. By 1992, the bombs had failed to fall, so the complex was decommissioned and eventually offered for sale. After a major grant to the Library from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, a long-time friend of American film history, the building was transferred to the Packard Humanities Institute . The facility was renovated thanks to over $260 million of Packard and Congressional funding. A lot, yes, but in 2017 dollars that comes to about $402 million, and Beauty and the Beast has scared up about twice that over the last couple weeks.

The renovation turned this vast bank vault/bomb shelter into the world’s most colossal and up-to-date media storage and preservation facility. Opened in 2007, the National Audio-Visual Center is also known as the Packard Campus. Its collection of films, videos, and audio records, along with posters and documents, come to over six million items sitting on ninety miles of shelving. With 80 per cent of it sunk below ground, it was designed to be an exemplary green building, with a vast gardened roof.

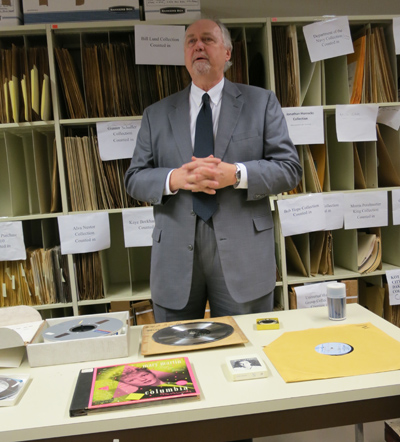

Thanks to the energy of Kluge Center director Ted Widmer and his colleagues, we had a chance to visit the place. Greg Lukow, Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus, and Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image section, led us in a labyrinthine, carefully organized three-hour tour of the dazzling facility.

I can’t convey all that we learned about conservation of film, TV, sound recordings, and digital media. Rest assured that the hundred-plus people working away here in state-of-the-art conditions are striving mightily to save media artifacts for you and me and our heirs. Here are some high points.

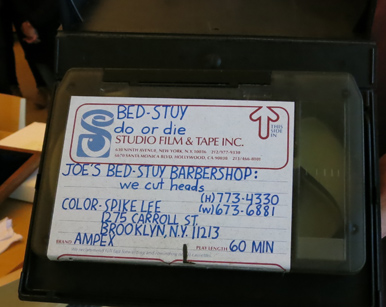

Mike introduced the visitors to the moving-image formats of the media conserved at the facility, everything from film and videotape to Digital Cinema Packages. Spike Lee’s first film, as a copyright deposit, is there too, on Ampex tape.

Sound isn’t neglected, as Greg offered a comparable overview of all the audio formats, including cylinder and wire recording. Yes, 8-tracks are also involved. On the right you see the Scully Lathe, a gleaming bad boy that cut disks. Used from the 1930s into the 70s it’s being brought back with the new interest in vinyl records.

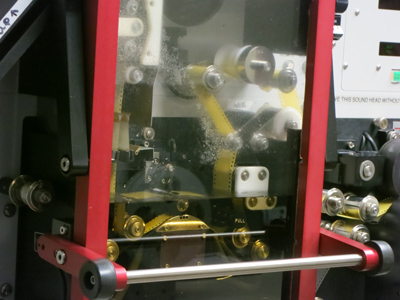

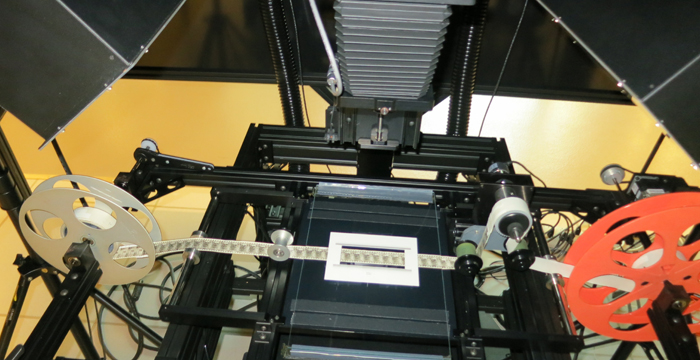

We visited several lab and restoration rooms, including one for wet-gate printing and another for migrating VHS tapes to digital files. Since the latter has to be done in real time, robots are recruited for the job, busily gliding up and down ranks of cassettes.

Of course we had to stop by film vaults, kept a chilly 39 degrees. On the left we see some of the holiest of holies, nitrate vaults. It looks like a Spanish Civil War prison, rows and rows of heavy doors. The vault on the right contains master safety film elements, on both acetate and polyester stock.

What’s a trip to an archive without despoiled artifacts? On the left, a flaking glass-based 16-inch lacquer instantaneous disc from the NBC radio collection. “Instantaneous” means that it was a recording of a live broadcast, and so was probably unique. On the right, we have decomposed nitrate film.

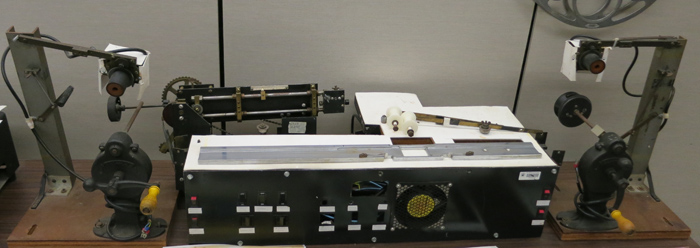

Of enduring interest to cinephiles is the famous paper print collection. Film companies of the earliest years submitted to the Library movies on rolls of paper, to be copyrighted in the manner of still photographs.To be preserved and screened, those had to be turned back into films. During the 1950s that task was fulfilled by Kemp R. Niver in a home-made rig.

He transferred some 3,000 titles to 16mm–not the ideal format, but better than nothing. Some results were fuzzy and jumpy, but many came out okay. I watched several during my stay, including The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914).

Since then, some excellent 35mm prints have been made from the paper prints, and still more success has been found with digital remastering, which can correct for misaligned frames on the original paper copies.

It was good to learn that film copies of new releases are still being submitted for copyright deposit. An impeccable print of Get Out arrived while I was there, and of course 35mm advocate Christopher Nolan wouldn’t miss a chance to save Inception and other of his works.

But I was dismayed to learn that a great many companies, taking advantage of a loose requirement about what counts as a deposit copy, are submitting DVDs, Blu-rays, and even DVD-R versions of their films. If they can’t submit a print, they should at least provide an unencrypted DCP. Otherwise, scholars and audiences of the future will encounter the digital equivalent of the crawling, scraped deterioration we see with film.

101 movies

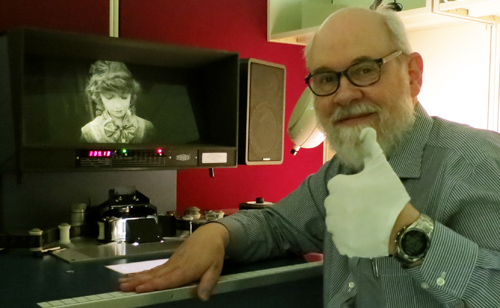

Fortunately for me, 1910s films are still available on film. Viewing prints of films stored at Culpeper are shipped to the James Madison Building in the District. There, in the Moving Image Research Center, they may be viewed on my old friend, the flatbed machine known as a Steenbeck. Every day a Steenbeck patiently awaited my depredations.

The staff of the Reading Room were just superb in helping me order titles and dig up information about them. Above you see the team I worked with: Dorinda Hartmann, Rosemary Hanes, Josie Walters-Johnston, and Zoran Sinobad.

I learned an enormous amount from them, and I enjoyed talking movies with them during our breaks. Others who helped me greatly were Karen Fishman, Research Center Supervisor, MBRS Division; Alan Gevinson, curator of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting; and David Pierce, Assistant Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus.

My mission was to see as many American fiction features from the 1910s as I could. This was the period when a five-reel film (ca. 60-70 min.) became a dominant format, though shorts and longer films were also being made. I’ve spent about a decade watching largely European films of the period in various archives and in Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, with results I’ve occasionally discussed on this blog. A visit to the LoC nicely complemented my Continental and Nordic explorations. Although several American films from the period are available on DVD, I’ve tried to see even those in film copies. (Why? Tell you later.)

For a time I was joined by James Cutting, perceptual psychologist extraordinaire, who enthusiastically wanted to watch these old movies. His presence helped me a lot, sharpening my attention to things in the images. Here’s James, skewed, during our nighttime trip to Chinatown for food and Get Out.

In all, across 42 business days (had to take days off for holidays and inauguration), I saw 101 films, 98 from my period and three others for other projects.

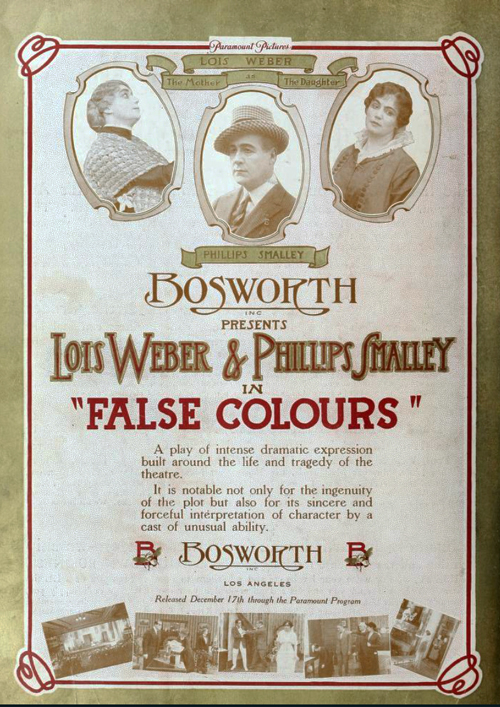

Not all the films survive complete. Some lacked one or more reels. That’s a great pity in the case of Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s False Colours (1914), Sunshine Molly (1915), and Idle Wives (1916); William deMille’s The Sowers (1916); William Desmond Taylor’s Ben Blair (1916); and many other stunning projects I got a glimpse of. But a little is better than nothing, as I’ve tried to show in an earlier entry and hope to show in later ones.

A few portions that remained were plagued by deterioration. Usually, that consists of ameba-like creatures swarming over the image. Some decadents wallow in these miasmas, especially on tinted prints. (See Lyrical Nitrate and Decasia.) Me, I can’t romanticize turning a 1910s drama or comedy into a 1960s abstract film. I want to see the story and the style, dammit.

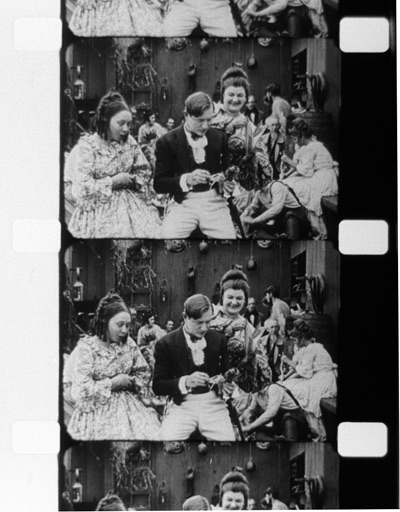

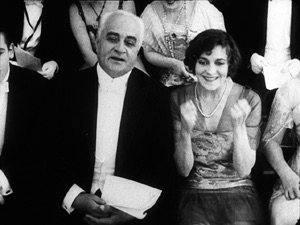

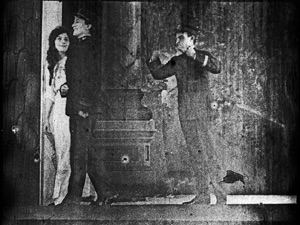

Another form of deterioration yields a ghostly, scraped-off image. Sometimes the decay changes from shot to shot, presumably because at some points the shots were segregated for tinting and toning. Here’s The Caprices of Kitty (Smalley, 1915), with Elsie Janis watching a play. In a gag on celebrity, she’s also an actor on stage (and in drag). After the nice shot of her and her father in the audience, the stage shot makes you shudder.

A first effort to clean it up with Photoshop helps, but still…Makes you remember why all that effort on the Packard Campus is necessary.

Of course a great many copies I watched were gorgeous. Orthochromatic film, with a ton of light dumped on the sets, yields images with incredibly rich gray scales. (My Ilford photochemical black and white couldn’t capture that range.) When we saw this parlor shot from By Right of Purchase, a 1918 Norma Talmadge melodrama, James blurted out, “Clutter!” A connoisseur of dense images, James later ran it through his algorithms and found that it had a spectacular degree of clutter.

Filigreed clutter is another big reason to like the 1910s, and archives like the LoC team are keeping it visible for us.

Deterioration isn’t the only insult these movies suffer. There’s the degradation of them in oft-copied versions. Compare this shot, from Reginald Barker’s splendid William S. Hart film The Bargain (1914), with the image you get if you buy the bootleg DVD.

Shot scale changes because of video cropping, facial expressions become unreadable, the eyes go dark, and that mounted trophy in the back just disappears. Of course things go a lot better with a video version of a film restored by the Culpeper crew (Moving Image Curator Rob Stone in particular). Olive Films has just released Wagon Tracks (1919), a fine William S. Hart film, on a very pretty Blu-ray derived from a tinted Library of Congress restoration.

So it can be done well, though I still prefer to study a 35 print, preferably untinted. Call me cranky.

The Packard Campus visit brought home to me how much effort is spent saving our film heritage. That heritage includes films that are little-known, but deserve better recognition. Watching with me, astonished by the technical ingenuity and wide-ranging experimentation rushing past us, James was reminded of the Cambrian Explosion, that period of origin and rapid diversification among earthly organisms.

It’s an intriguing analogy. A mere dozen years yielded “our cinema,” as I’ve argued in this video lecture–the sturdy prototypes of moviemaking today. Yet along with enduring models of story and style came a cascade of ingenious novelties that weren’t taken up much. The 1920s, for all their innovations, tended to prune away some of the more eccentric but intriguing tendencies that burst out in the 1910s. In my next entry on the subject, I’ll offer some examples.

I owe a tremendous debt to the John W. Kluge Center for supporting my stay at the Library of Congress. Thanks especially to Ted Widmer, Director of the Center, and his colleagues Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello. Also I enjoyed enlightening conversations with Peter Brooks, in residency at the Center, and the other Kluge Chairs Timothy Breen, Jose Casanova, and Wayne Wiegand, all embarked on fascinating projects.

Thanks also to all the staff at the Packard Campus, who enthusiastically shared information about their work habits. We’re grateful to Greg and Mike for spending so much time with us.

The digital spoor on the Packard Campus leads far and wide; a Google search will yield you many nifty items. The 2007 plans for the facility are reviewed in this information-packed presentation by Greg Lukow. For something more recent, try the Wired visit by Brian Gardiner. On the digitizing side, see Boing Boing’s extensive coverage, including an interview with Greg. There’s a good half-hour C-span documentary tour led by Mike Mashon. Mike’s blog Now See Hear! offers updates on current Campus events.

Tony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait (McFarland, 2000) remains the essential source on U.S. film preservation. It has some good anecdotes about Kemp Niver, including one involving a pistol and Raymond Rohauer. Criterion has a nifty little film on wet-gate restoration of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935).

If you’re interested in film research, you need to read James Cutting’s sweeping big-data studies on film. A good summing up of part of it is “Narrative Theory and the Dynamics of Popular Movies.” There’s interesting commentary on it here from a psychologist and here from a screenwriter (who clings to the three-act model). James’s book on the formation of the canon of Impressionist painting has been invoked in Derek Thompson’s book Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction (Penguin, 2017), 23-26.

For more on visual clutter, see this paper on clutter and visual search, of which Tim Smith, master of eye movements, is a co-author; and two papers specifically on movies, by James, one with Kacie Armstrong: here and here.

DB makes Lillian bashful in The Lily and the Rose (1915).

Waldo Lydecker, James Schamus, and 1910s movie storytelling

Laura (1944).

DB here (in DC):

Over the next two weeks I’m involved with several events during my stay at the John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. If you’re near Washington, do consider coming to one or all of these doings.

First up is a screening of a sparkling restored print of Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944), at the gorgeous Packard Campus Theater in Culpeper, Virginia on 8 March. The show, a new addition to the Theater’s spring schedule, starts at 7:00 pm, a half-hour earlier than the customary time. I’ll be giving a brief introduction.

On the following Monday, 13 March, the Kluge Center will host “James Schamus on Philip Roth and the Art of Adaptation.” After a screening of James’s directorial debut Indignation, he will participate in a discussion with the audience. I’ll play moderator. The event will take place at 3:00 pm in the Pickford Theater, on the third floor of the Library’s Madison Building, 101 Independence Ave. S.E.

James, professor at Columbia and producer and writer of many important American and Chinese films, needs no introduction to this blog’s readership. (Above, he’s with frequent collaborator Ang Lee.) We’ve celebrated his work here, and I discussed the admirable Indignation just last summer. This upcoming session should be an exhilarating afternoon.

Lastly, I’m giving a talk, “Studying Early Hollywood: The Search for a Storytelling Style.” It develops some of the issues I’ve floated in my books, other lectures, this video lecture, and most recently this blog entry. The talk is set for 4 pm. on Thursday, 16 March. It takes place in room 119, a magnificent venue on the first floor of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St. S.E.

All these events are free and open to the public, and you don’t need tickets.

Being at the Kluge Center has been very stimulating, and my research into 1910s visual style has benefited hugely from access to the LoC’s film collections. These three events are wonderful ways to wrap up a stay that has gone by all too fast. If you’re in the vicinity, come by and say hello.

Thanks to the many people who have made these events happen: At the Kluge Center Ted Widmer, Mary Lou Reker, Dan Turello, Travis Hensley, and Emily Coccia; at the Packard Campus Greg Lukow, Mike Mashon (initiator of many things), and David Pierce.

More information on the Packard Campus Theater is here. A summary of James’s vast career is here.

The Packard Campus Theatre. Photo by Glenn Fleishman.

Anybody but Griffith

Motion Picture News (19 December 1914), 148.

DB here:

For almost two months, I’ve been in Washington, DC at the Library of Congress. The John W. Kluge Center generously appointed me Kluge Chair in Modern Culture. This honor has enabled me to work with the enormous collection of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division to sustain my research in American narrative cinema of the 1910s.

I wanted to go more deeply into an area I mapped out in the video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” and in the books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. The general question was: How did the norms of storytelling technique develop between 1908 and 1920? More specifically, I hoped to trace out an array of stylistic options emerging for the feature film. What range of choice governed staging, framing, editing, and kindred film techniques?

Theatre, but through a lens; painting, but with movement

If you’ve seen that lecture, or just followed this blog from time to time, you know that I’ve sketched out two broad stylistic trends operating at the period. One, celebrated as a breakthrough for a hundred years, involves the development of continuity editing. That trend was explored by several historians of early film, including Kristin in the book we did with Janet Staiger, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960.

Critics and historians who saw editing as the essence of cinematic technique called the second trend “theatrical” and regressive. Directors in that trend supposedly simply planted the camera in one spot and let it run, recording performances and not bothering to cut up the scene into closer views. This “tableau” tradition was superseded by an editing-based style–and, many thought, a good thing too.

Over the last twenty years, however, scholars have reappraised that apparently static and passive camera. Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster’s trailblazing book, Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (1997) traced film’s many debts to theatrical plotting, set design, and especially performance. In a parallel series of articles, Yuri Tsivian proposed that the “precision staging” of the 1910s had deep affinities with traditions of painting and visual culture. Lea, Ben, and Yuri showed that the tableau tradition offered rich creative choices to filmmakers.

For my part, I was concerned to explore how ensemble staging worked in a moment-by-moment fashion to call the viewer’s attention to key aspects of the action. Editing does that by cutting to closer views. In the tableau method, emphasis arises from composition, movement, and other pictorial strategies.

In light of all this research, it seems clear that during the 1910s the tableau strategy developed into a powerful expressive resource. After Figures Traced in Light (which found the tradition still alive in directors like Angelopoulos and Hou), I continued to collect examples of creative staging at this early period. The results led me to analyze films by Yevgenii Bauer, Danish directors, and other Europeans.

Evidently the tableau persisted until 1920 or so in Europe, especially Germany, but the editing-centered option had already become dominant in America. But how long, and in what ways, did tableau methods hang on in the US? Or was the switchover quite quick? By 1917, Kristin had posited, continuity editing had crystallized as the primary storytelling style. I thought I’d try some depth soundings of the period.

Evidently the tableau persisted until 1920 or so in Europe, especially Germany, but the editing-centered option had already become dominant in America. But how long, and in what ways, did tableau methods hang on in the US? Or was the switchover quite quick? By 1917, Kristin had posited, continuity editing had crystallized as the primary storytelling style. I thought I’d try some depth soundings of the period.

Since my time was limited, I had to focus. Charlie Keil’s superb Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking 1907-1913 (2001) analyzed a great many films of that phase in depth, particularly with respect to editing techniques. So I thought I’d start with 1914 and simply try to see as many features from that year as I could. I then would sample items from later years. My only rule was to watch films that aren’t part of the canon–no Griffith, Chaplin, Fairbanks, Pickford, Fatty et al. I did, however, try to see rare things by Lois Weber, Reginald Barker, and other well-regarded filmmakers.

What did I come up with? I’m still watching and thinking, but let me share a few items that excite me. Clearly, despite plenty of audacious editing, the tableau technique was alive and well in America in 1914-1915. And the more I see, the more I’m inclined to rethink the terms under which I value Mr. D. W. Griffith.

Tableau trickery

A simple illustration of how a fairly distant tableau can vividly guide our attention shows up in The Case of Becky (1915), directed by Frank Reicher.

Before an audience, the sinister hypnotist Balsamo hypnotizes Becky. From a deck of cards he has selected the ace of hearts, and in her trance she has to find it. There’s almost no movement in the frame: Balsamo stays frozen, as does Becky, except for her one hand flipping over the cards.

No need for a close-up: With Balsamo as still as a statue, every viewer will be watching that tiny area of the screen occupied by her hands, and we wait for her to find the ace. When she does, Balsamo accentuates her minimal gesture by twisting his arm and freezing into another pose.

Is this, then, simply filmed theatre? Not really. First, many tableau framings, like the Case of Becky instance, put the actors closer to us than stage performers would be.

Just as important, the perspective view of the camera yields a chunk of space very different from that of proscenium theatre. In cinema, for instance, depth is more pronounced, and actors can be shifted around the frame to block or reveal key information. This isn’t pronounced in the Case of Becky example because the two characters are more or less on the same plane and the background is covered by curtains. But consider this shot from The Circus Man (1914), by Oscar C. Apfel.

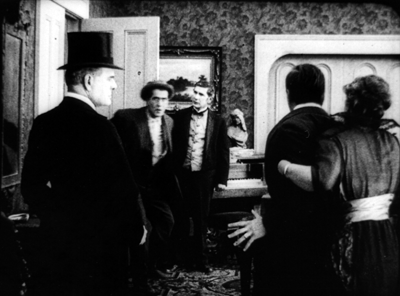

The circus owner Braddock has been sent to prison for murder and attempted robbery, a plot engineered by Colonel Grand. Now Braddock has served his sentence, and in a scene too complex to trace entirely here (but maybe in a later entry), he bursts in past the butler to confront Grand. Here’s what we see.

Such a scene would be inconceivable on the stage because of the audience’s sightlines. People sitting in the left side of the auditorium couldn’t see Braddock’s entrance, because he’d be concealed by Grand, who’s standing in the foreground left. Audience members on the right side of the auditorium couldn’t see Braddock either, because Mrs. Braddock and David are standing on the right foreground.

The shot makes sense from only a very limited number of points, only one of which is occupied by the camera. Maybe a few people in the center of the theatre would have a fairly clear view of such an action, but as we’ve seen with The Case of Becky, they wouldn’t be so close to the players.

The sheer fact of optical projection means that cinematic space is narrow and deep, while stage space is broad and (usually) fairly shallow. On the stage, players tend to be spread out laterally, allowing for many sightlines. Cinematic staging can be deep and diagonal.

On the other hand, the tableau shot isn’t perfectly analogous to a painting. While the lens chops out a perspectival pyramid in three dimensions, the movement in the frame creates a two-dimensional flow–a cascade of planes and edges very different from what we’d get in a painting. This flow can be used to reveal or conceal bits of space as the action develops.

You can see this compositional flow clearly in an earlier phase of the Circus Man sequence. Before Braddock bursts in, David has been arguing with Colonel Grand in the foreground. David’s and Grand’s heads occupy the area that Braddock will soon claim. Just before that entrance, Mrs. Braddock pulls David back a bit to the right, and Grand recoils fractionally to the left. This creates a hole that Braddock can come into (as above).

This sort of slight shifting is akin to what we see in the astonishing poorhouse sequence of Victor Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), analyzed here. Clearly the Americans were executing the same sort of choreography as the Europeans, which turns the static image of a painting into something more dynamic, a sort of micro-dance.

Flo and flow

The married couple Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley are responsible for a little masterpiece of early cinema, Suspense (1913), which I’ve discussed here. It’s become a classic largely because its audacious close-ups and cutting seem to anticipate classic Hollywood style. But seeing, or sort of seeing, two other films by Weber and Smalley suggest that they were no less adept at the tableau method.

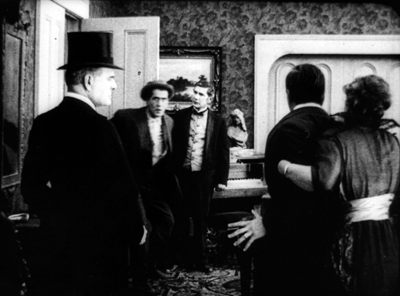

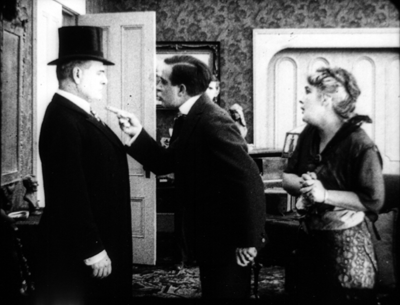

I say “sort of seeing” because the copy of Sunshine Molly (1915) was so deteriorated that in long stretches only faint outlines of the people and locales were visible. The plot was pretty clear, but the images were so blotchy that only a few furnish clear frames. Still, it would seem to have been quite a good film. With False Colours (aka False Colors, 1914), two or three reels were missing. But what was there was pretty spectacular, and one scene is really striking if you’re interested in staging.

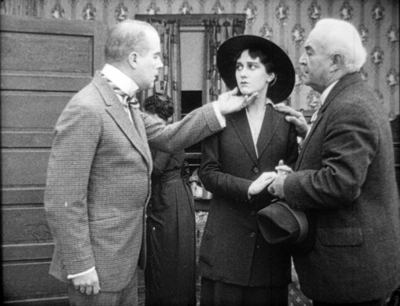

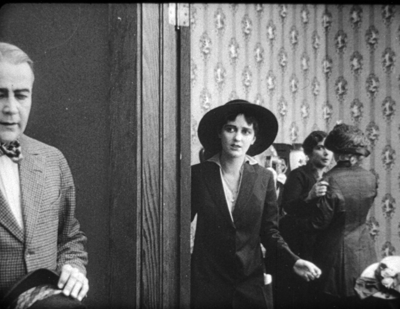

As with The Circus Man, at first glance things look stagebound. Dixie’s long-separated father comes to the foreground where she stands waiting with the theatrical manager. He abandoned her as a baby, and now that she’s found success as an actress she spurns him.

But no stage arrangement could yield the layout we get in this shot. While father and daughter and manager occupy the “forestage,” we see Flo, who has impersonated Dixie in an effort to get the father’s money, step into the gap. (Flo is played by Lois Weber.)

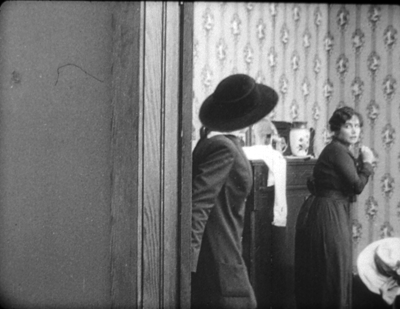

Thanks to the depth of the “cinematic stage,” we get what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis”–not just two layers of space, as in The Circus Man, but action and reaction in depth, as we wait for the foreground action to develop. That action hits its high point when the father touches Dixie’s chin.

This gesture partly masks Flo, who briefly turns away as well. The emphasis falls firmly on the father’s contrition. Dixie still refuses him, and so he says farewell, re-exposing Flo turning in the background.

As he departs, so that we get the full force of his encounter with Flo, Dixie turns from the camera. We must concentrate on the moment in the background when the imposter shows remorse for having won the love of the man she deceived.

At the door

You might object: “But David! Those examples are still very stagebound. The Case of Becky shot is itself on a stage, and the others, despite all their depth, show boxlike rooms from straight on. They seem firmly tied to a proscenium concept. Shouldn’t we expect something more natural?”

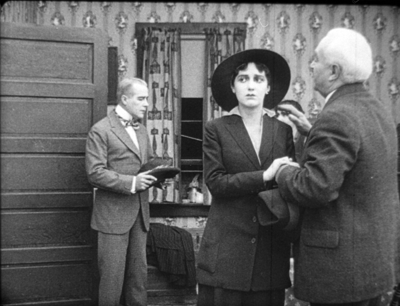

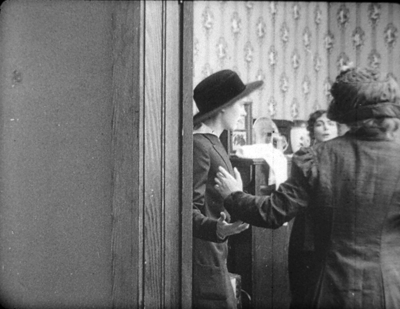

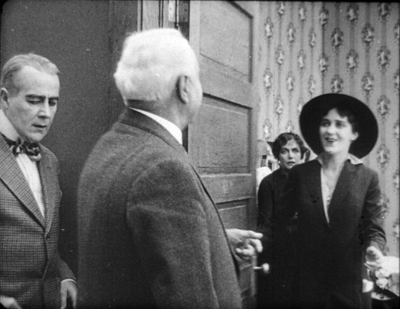

Fair enough, so I submit this earlier phase of the False Colours scene. This time we have a doorway, framed diagonally, that cuts off a lot of playing space. And we see obliquely into a corner of a room, not straight on to a back wall. Yet you still get an interplay of faces and bodies, carrying to a daring extreme the blocking-and-revealing tactics we’ve seen in The Circus Man and in the later phase of the False Colours scene.

Dixie comes to Flo with Flo’s mother. At this point Flo recognizes Dixie as the daughter she’s been impersonating and is deeply ashamed. You won’t be surprised by the dazzling precision of the frontal placement of Flo, no matter how far she is from the camera.

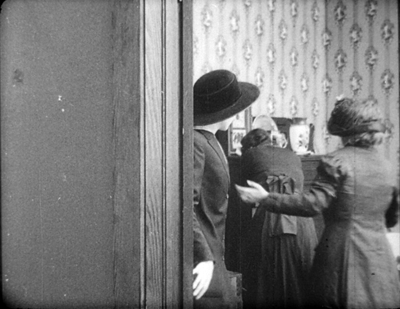

Flo is consoled by her mother, and Dixie shuts the door discreetly.

But why so much empty space on the left of the door? Because now the theatre manager is coming, and the framing shows us what Dixie doesn’t know: Her father is standing there alongside the manager.

There’s a moment of suspense before the father hesitantly steps to the doorway and Dixie sees him for the first time in seventeen years.

He blots out everything but her reaction, until Flo’s face slides into visibility. Cornered, she’s terrified to be confronting the man she has deceived.

The father’s valet has obligingly slid into the left to balance the frame, but he stands as frozen as the hypnotist Balsamo had been, looking patiently downward, to make sure we concentrate on the pitch of drama taking place in the distance. This is as purely “cinematic” a scene as anything involving editing.

And who needs close-ups?

Griffith is a great director, but other filmmakers of his period were exploring cinematic possibilities he didn’t consider. Their editing is often more subtle and careful, and the exponents of the tableau style achieve a pictorial delicacy mostly at variance with his work.

More and more, this Founding Father of Hollywood seems to me an outlier–an eccentric, raw, occasionally clumsy filmmaker who went his own way while others refined a range of stylistic practices. I’m starting to think he favors a brute-force approach, in both physical action and the evocation of sentiment. The result is powerful, but… Well, I’m reluctant to say it, but after my two months of immersion in Anybody But Griffith, he’s starting to seem somewhat crude.

I’m tremendously grateful to the John W. Kluge Center, and particularly its director Ted Widmer, for enabling me to conduct this research under its auspices. A special thanks to Mike Mashon of the Motion Picture Division, and all the colleagues who have been helping me in the Motion Picture and Television Reading Room: Karen Fishman, Rosemary Hanes, Dorinda Hartmann, Zoran Sinobad, and Josie Walters-Johnston.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema is available for download here.

For our blog entries relevant to the tableau tradition, go here. Lois Weber made many other important films, notably Hypocrites (1915), Where Are My Children? (1916), Shoes (1916), and The Blot (1921). See the exceptionally detailed Wikipedia entry for more information.

False Colours (1914).