Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Oscar’s Siren song 3: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Moana (2016).

DB here:

Our colleague and Film Art collaborator Jeff Smith is an expert on film sound, particularly music. He’s contributed several items to our site over the years (for example, here and here and here). Today he’s back with his annual survey of Oscar’s musical categories. He offers in-depth analysis of how the films’ scores and songs enhance the movies’ impact.

As I’ve done in the last two years, I’m offering another preview of this year’s nominees in Oscar’s two music categories: Best Original Song and Best Original Score.

This year, La La Land’s Justin Hurwitz is nominated in both categories. He is poised to join a small group of composers who won awards in each. Leigh Harline and Ned Washington first accomplished the feat in 1941 for Pinocchio. A.R. Rahman was the most recent. He won Best Original Score for Slumdog Millionaire and Best Original Song for its Bollywood inspired closer, “Jai Ho.” Remarkably, Alan Menken was a two-fister four separate times. His eight Oscar wins came from four of Disney’s animated musicals: The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), and Pocahontas (1995). (And I’ll bet you’re humming “Under the Sea” or “A Whole New World” to yourself just now.)

Will Hurwitz join this august group of composers? Hard to say, but I suspect he will since I am picking against him in one of these two categories.

Based on my track record, this likely bodes well for Hurwitz. As faithful readers know, in the past two years, I’ve gotten two right and two wrong as a prognosticator. A 50% success rate is not too good. But then again, in recent ceremonies, one of these two categories has reliably produced a surprise win. Two years ago, Alexandre Desplat’s The Grand Budapest Hotel upset Jóhann Jóhannsson’s The Theory of Everything for Best Original Score. A year later, Lady Gaga and Diane Warren came in as clear favorites for Best Original Song. But the award went to Sam Smith and Jimmy Napes for Spectre’s “Writing on the Wall.” Both of these awards confounded the conventional wisdom, and I suspect I was not alone in having a music award wreck my entry in the office Oscar pool.

Given my past struggles, I even considered taking an approach inspired by Seinfeld’s George Costanza: just pick the opposite of my natural preferences. Yet, even this only gets me back to a 50% success rate. So for better or worse, the predictions offered below are genuinely my best guess as to which nominee ultimately wins each award.

Best Original Score: Will fourteen be Thomas Newman’s lucky number?

Perhaps the most striking thing about this year’s nominees is the number of first-timers. Of the six people recognized in this category, only Thomas Newman has been nominated before. But Newman is very unusual in this regard. He has accumulated more than a baker’s dozen of nominations over the past twenty-two years and still has yet to win. Newman’s cousin Randy experienced a similar drought, but eventually won for Best Original Song for Monsters, Inc. on his fifteenth try.

Thomas Newman’s nomination this year is for Passengers and it represents the composer’s second foray into science fiction scoring. (His first was in Pixar’s 2008 film WALL-E, for which he received two nominations.)

When film composers say their goal is to fulfill the director’s vision, it reminds us that they do not write music for the sake of music. Their contributions are never meant to stand alone. Their theme writing, their selection of instruments, and the placement of their music are always dictated by the material they read in a script or that they see on screen.

And myriad choices typically flow from the composer’s first encounter with the work.

Do I strive for a big orchestral sound? Or do I go for something more intimate in the style of salon or chamber music?

Do I write a big theme that will carry through the entirety of the film? Or do I adopt a textural approach that emphasizes rhythm, harmony, and tone color more than melody?

Do I capture the varied moods and tones of individual scenes — a skill at which classical Hollywood composers excelled? Or do I try to envelop the drama in a single, sustained emotional color, one that endows even simple or ordinary actions with affective significance?

These questions are not easy ones. But Newman’s ability to consistently answer them has made him one of the most reliable and versatile composers in Hollywood.

In a Variety interview, Newman noted that he initially considered a common tactic for scoring science fiction films – that is, writing futuristic music for a futuristic setting. Newman opted instead “to play to the conventions of what a space movie would sound like.” And ever since John Williams’ score for Star Wars, space movies tend to feature a big orchestral sound.

Newman’s score features more than sixty string parts and thirteen brass. It also adds hefty doses of electronics and piano to these more traditional orchestral sounds. According to the composer, this lent the score a more contemporary edge.

Passengers’ music, though, functions “bigly” both in size and scope. Covering 96 minutes of the film’s 116 minute running time, Newman’s score also plays a wide range of moods and tones. Newman aimed to highlight the elements of loneliness, humor, and action that he felt were already present in Morten Tyldum’s “Adam and Eve in space” conceit.

Newman’s main title offers a window into his compositional techniques in Passengers. The cue begins fairly quietly with an electronic instrument playing a busy arpeggio figure. In another context, it might sound like a loop in an EDM track. Over time, though, the arpeggiated figure is subtly varied in rhythm and pitch with additional instruments thickening the music’s overall texture. The timbres at the start are rather light and airy, combining the “bell-y” sound of a Fender Rhodes with electronics imitating the sounds of strings and winds. After about two minutes, bass voices enter adding a sort of pulsing pedal tone that further grounds the cue’s minor key harmonies. A horn blast comes in about thirty seconds later, followed by a rising furioso string figure that briefly builds tension before suddenly peaking in volume and intensity. As the reverb and echo of this climactic chord fade out, the music returns to the light, airy sounds and arpeggios heard at the start.

Newman’s score and Guy Hendrix Dyas’s impressive production design (also nominated) are undoubtedly the best things about Passengers. But that likely won’t cut any ice with Oscar voters. Given the film’s tepid critical reception, it seems unlikely that Passengers will break Newman’s current losing streak.

Jackie: Dig the New Breed

Compared with Newman’s veteran experience, Mica Levi is positively a babe in the woods. Her only feature film experience prior to Jackie was on Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2013). Yet, thanks to her brooding score for Pablo Larrain’s unusual biopic, Levi is now one of only five women to receive a nomination for either Best Original Score or Best Original Song Score.

Levi’s approach to the compositional process on Jackie was unusual. She relied on her historical knowledge of the former First Lady and on Noah Oppenheim’s script. She submitted her score to Larrain without actually seeing footage of the film. Larrain himself ultimately decided on the music’s placement.

Levi’s score is largely built out of sustained chords, dissonances, and orchestral glissandi that, in the composer’s words, give you “this glooping and distortion and morphing…” These glissandi are particularly striking and unusual, but they work beautifully within the film’s dramatic context. Lots of film music has been written to capture a character’s sense of loss. What these glissandi add, though, is a sense of trauma to Larrain’s dramatic conception of the character. Jackie invites the audience to consider what it’s like to be a public figure and to have your beloved husband killed in the most shocking and bloody manner imaginable. The film dramatizes Jackie’s fight for Jack’s memory despite this numbing, almost crippling sadness. Levi’s music nicely reflects these feelings of psychic dislocation, even as Jackie struggles to scale a wall of government bureaucracy and protocol that stands in the way of her plans for the president’s funeral.

Aside from a couple of cues that Levi describes as “vapid,” the score sustains a mood that highlights the post-traumatic stress that lay just beneath Jackie’s public expressions of grief. This proves important insofar as the music provides a unifying thread to Jackie’s temporally fragmented structure. Larrain’s time scheme is bracketed by two interviews. The first is a television broadcast where Jackie gives viewers at home a tour of the White House. The second is a Time magazine interview with journalist Theodore H. White in which Jackie works to protect the JFK’s “Camelot” legacy. In between are several scenes situated either just days before or days after Kennedy’s fateful trip to Dallas. The structure is further stretched to accommodate flashforwards to Jackie talking with a priest and burying her two dead infants.

Larrain cuts freely between these points in time, creating a mosaic portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy as a figure of strength and grace. And Levi’s score not only supplies continuity, but also adds a consistent emotional undertone to the abrupt changes in cinematographic style apparent in individual scenes.

With music that is strikingly different from her earlier work on Under the Skin, Levi shows that, although Jackie is her first Oscar nomination, it will not be her last.

Moonlight: Mr. Mozart meets DJ Screw

Like Mica Levi, Moonlight composer Nicholas Britell is a relative newbie when it comes to the world of feature film scoring. Britell’s opportunity on Moonlight came thanks to his work with Brad Pitt’s production company, Plan B Entertainment. He scored two of the company’s most high-profile projects: 12 Years a Slave and The Big Short. When Plan B decided to put Barry Jenkins’ script into development, the company’s co-president, Jeremy Kleiner, sent a copy to Britell in order to gauge the composer’s interest.

Britell was struck by the “poetry” of Jenkins’s vision, which he believed was already evident on the printed page. In a follow-up meeting, the composer and director spent hours talking about films, music, and life. According to Jon Burlingame, Britell then sent a tape to Jenkins that contained an eclectic mix of styles “ranging from the Isley Brothers to Mozart.”

To my knowledge, Britell’s playlist was not used as a temp track, but it played much the same function as a vehicle of communication between composer and director. For Britell, these sample tracks gave Jenkins an impression of what he thought the film should sound like.

Britell arranged some cues for solo violin and piano as a correlate to the intimate mood established in Moonlight. Both instruments were closely miked, and these chamber-styled cues, thus, add a character-centric, arthouse ambiance to this tale of “boy n the hood.” Britell’s choice is quite fitting insofar as Jenkins acknowledges Claire Denis’s Beau travail and Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Three Times as major influences on his coming-of-age story.

Yet Britell also applied hip-hop production techniques to some of these tracks in order to reflect both the protagonist’s character change and Jenkins’s own interest in the genre. Some cues were remixed using a “chopped and screwed” approach. This technique was innovated Houston hip-hop artist DJ Screw and it involves slowing the music’s tempo to almost half its normal speed. An example of this is heard when Kevin punches Chiron to impress his friends. Here “Chiron’s Theme” is slowed down, dropping the pitch of couple of octaves, and then layered atop itself. One hears the mournful piano chords of Britell’s central musical theme intertwined with its own pulsing echoes, the latter sounding as though they’ve risen from the bottom of an abyss.

Britell supplements “Chiron’s Theme” with cues that take shape either as swirls of static, harmonic resonance or as shards of Ivesian dissonance. All of it is in keeping with the composer’s mostly minimalist approach. Britell’s great achievement on Moonlight comes from the way the music’s small, spare style nonetheless yields moments with outsized emotional impact.

Lion: Finding the ghost of John Cage in a shantytown in India

Dustin O’Halloran and Hauschka also earned their first nominations for their music for Lion. Unlike Jackie, though, where Mica Levi began work on the basis of the script, director Garth Davis didn’t even begin looking for composers until he locked picture. He approached O’Halloran and Hauschka with the idea that they would work as a team. Hauschka would compose for the first half of the film and O’Halloran would handle the second.

Davis eventually dropped this idea, though. Instead he opted for a more unified approach in which each composer’s contributions would be blended together. O’Halloran and Hauschka then spent three weeks sending ideas back and forth between their respective studios. Having progressed in this initial idea stage, the pair met up in Los Angeles and worked together to finish the score over the next eight weeks. As O’Halloran noted in an interview, “We had spent a lot of time in each other’s world, and the thought of us making music together was pretty exciting because we’d been friends for so long.”

Initially, Davis was drawn to Hauschka’s music based on the latter’s cutting edge work with the prepared piano. A prepared piano is one in which foreign objects are placed atop or wedged between the strings attached to the instrument’s soundboard. The presence of these unusual objects alters the piano’s usual timbre, often giving it a more percussive sound when its hammers strike the strings.

The prepared piano is usually associated with American avant-garde composer John Cage. As the story goes, Cage’s use of the prepared piano solved a problem that arose from his commission to write music to accompany Sylvilla Fort’s dance piece, “Bacchanale.” Cage initially planned to write for a percussion ensemble, but then substituted the prepared piano when he realized that the performance space was too small to accommodate a large group. In interviews, Hauschka notes that he was unaware of Cage’s precedent when he first began to play prepared piano. But when people kept asking about Cage after hearing him perform, Hauschka went back to the latter’s pioneering work and now counts himself a fan.

Davis had already envisioned the use of prepared piano for the scenes set in India. His idea was that the unusual tone colors of the prepared piano would supply a sound that is comparable to Indian music without duplicating the idiom wholesale. A good example of this balance between western and eastern musical elements is evident in the scene where young Saroo gets lost in a train station. In Hauschka’s own words, the prepared piano adds a repeated “tat-tat-tat” sound that conveys the character’s panic, particular when authorities round up all the homeless children.

For some of the film’s other scenes, O’Halloran provides a melancholy theme first introduced over the film’s opening images. It features a repeated arpeggio figure in the piano accompanied by rising and falling string harmonies patterned to cyclically fold back on itself.

As with Moonlight, Davis, O’Halloran, and Hauschka opted for a smaller, more intimate sound. They recognized that the film’s potentially melodramatic story of maternal separation didn’t need additional hype from the music. Such parsimony allows Lion to unfold with subtlety and grace, its strongest moments underplayed by O’Halloran and Hauschka’s quietly affective score. The music also reflects the protagonist’s complex motivations, balancing his drive to know with his desire to spare his adopted family from feeling rejected.

La La Land: Justin Hurwitz, revivalist

Damien Chazelle’s La La Land has already received ample coverage on this blog here, here, and here. To a certain extent, I have little to add to the excellent contributions made already by David (here and here), Amanda, Eric, and Kelley. Since much ink has already been spilled regarding composer Justin Hurwitz’s considerable contributions to the film, I’ll provide a few bits of historical perspective.

Hurwitz’s prime achievement, and the source of a lot of critical praise, is his skill in integrating the melodies of the numbers into score cues that perform more traditional dramatic functions. In this respect, Hurwitz is a throwback to an earlier period of film music history, one that emphasized theme writing over more texture-and-timbre oriented “sound beds” approach so common today.

For me, the role models for Hurwitz’s approach are not the studio composers sometimes associated with the musical as a genre, such as Lionel Newman or Andre Previn. He’s closer to early sixties composers who applied this integration of songs and scores in different genres. Henry Mancini is an exemplar of these techniques. He often began by writing the specific themes for his scores, and then adapted them to the verse-chorus-bridge patterns found in standard 16-bar and 32-bar song forms.

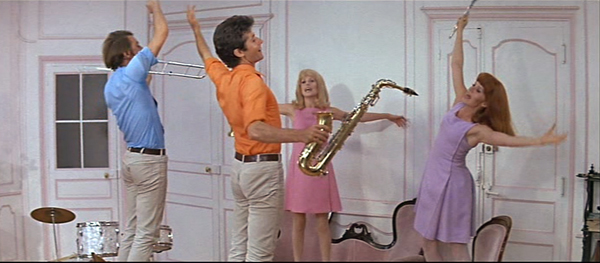

These skills are also evident in the music of Michel Legrand, whose scores for Jacques Demy are an acknowledged influence on La La Land. This “theme song and variations” strategy has become something of a lost art. In Legrand’s and Mancini’s work, one finds it not only in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and Darling Lili, but also in dramas, comedies, and capers like Summer of ‘42, The Pink Panther, and The Thomas Crown Affair.

Yet, although Mancini and Legrand are obvious role models, Hurwitz pushes this strategy even further than his predecessors. Not only is the score integrated with the songs, but the songs themselves are integrated with one another. After the lounge performance of “Mia & Sebastian’s Theme,” each new song they perform sounds like a subtle variation of its predecessor. The tempo and meter of the songs differ quite considerably. But they nonetheless seem to spring from the same Schenkerian ursatz, working through the same harmonic shifts, cadential patterns, and delicate shifts from minor to major.

Once La La Land’s concluding “dream ballet” begins, Hurwitz’s themes flow seamlessly into and out of one another. The recapitulation of motifs – both dramatic and melodious – feels completely cohesive and whole. This music’s organic unity is felt even despite the fact that it accompanies a time-shifting, synoptic, happily-ever-after fantasy.

All of Hurwitz’s tunes are cunningly effective earworms. By reprising all six of them in a final stylized depiction of the characters’ emotional journey, the dream ballet provides La La Land with the kind of musical climax that most film composers can only dream about.

And if you were one of Hurwitz’s Oscar competitors wanting to cry, “Foul!” I think you’d have a point. At various points in its history, the Academy has bracketed off music scores and song scores into separate categories. Their earlier existence is almost a tacit admission that voters are being asked to make apples-vs.-oranges comparisons.

For this year, at least, Hurwitz is likely to benefit from the fact that La La Land is something of a unicorn. During the past twenty years, lots of musicals have received recognition from the Academy. But in almost all cases, these have been either adaptations of successful Broadway musicals or weird pastiches of preexisting popular music. Consequently, they’ve always been excluded from consideration for Best Original Score. La La Land is, thus, not only an original screen musical, but one in which every cue and every tune is both new and infused with Hurwitz’s singular vision.

None of this would matter if the film didn’t deliver the goods. But La La Land does so in spades. You’ll find few films that combine its emotional heft, its topline production values, its formal sophistication, and its intricate relation to its generic heritage. As both a valentine to the City of Angels and perhaps the meta-musical to end all meta-musicals, La La Land is clearly the front-runner for Best Picture. And I expect Chazelle and company will collect an armful of hardware long before that final award is announced next Sunday night.

Prediction: Need you ask? It’s Justin Hurwitz all the way!

This is a very strong field and I admire the way all of these composers have experimented with technology and compositional techniques to defy convention. Yet they’ve also created work firmly tethered to important aspects of Hollywood tradition, especially in the ways their scores convey mood and character subjectivity.

Yet, although the piano plays a prominent role in the orchestrations and central musical concepts of all these scores, I’m picking the one that features an actual pianist as protagonist. Hurwitz’s expected win in this category is as close to a lock as these things get.

Best Original Song: Docs and tuners and toons, oh my!

As my header suggests, one of the most striking things about this year’s field is the fact that the songs represent particular niche markets within the industry. Documentaries and animated films occupy opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of their budgets and box office returns. But they are both aimed at demographic segments that are either a little or a lot narrower than the mainstream audience for the biz’s more traditional tentpoles.

And as we’ve already seen on this blog, musicals are one of those “they don’t make ‘em like they used to” genres that caters to more specialized tastes. This seems to be a change from, say, twenty to thirty years ago when Original Song nominees came from a variety of genres, including studio-produced action films, comedies, dramas, and fantasy films, in addition to those featured in Disney’s animated musicals.

Moreover, there is also plenty of star power in this year’s field. Justin Timberlake, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Sting are among this year’s nominees.

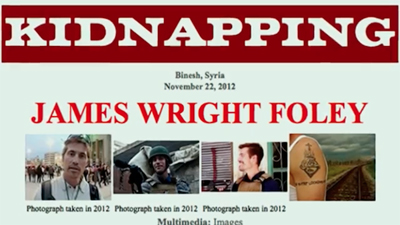

“The Empty Chair” was written by J. Ralph and Sting for Jim: The James Foley Story, a portrait of the journalist kidnapped and executed by ISIS terrorists. It continues the recent trend toward recognizing songwriters’ contributions to contemporary documentaries. Last year saw nominations for The Hunting Ground and Racing Extinction, the latter featuring another track co-written by J. Ralph. Two years ago, “I’m Not Gonna Miss You” was nominated from the music doc, Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me. This trend is likely to continue. According to Variety’s Jon Burlingame, seventeen of the ninety-one songs eligible for this year’s award came from documentary films.

In composing the lyrics, Sting drew lines from Foley’s letters home and from from reminiscences of his colleagues. Placed in the end credits, the song sums up what we’ve just seen. The empty chair is, of course, the place at the family table to which Foley will never return. As an encomium to the fallen journalist, the song reminds that Foley’s death leaves an empty place both in his family and in his profession.

The film’s subject matter is weighty and the song’s plaintive melody and spare arrangement nicely encapsulate its gravity. Yet the fact that the film is little-seen makes it an uphill climb in terms of collecting Oscar votes. All of the other nominees have received much greater exposure and are also more clearly integrated into the narratives of their films. This is a case where the nomination itself is the real award. Although “The Empty Chair” gave Sting his fourth nomination, he’ll have to content himself with the sixteen Grammy awards he’s already won.

Islanders and trolls (and not the Internet variety)

Justin Timberlake, Max Martin, and Shellback all received nominations for “Can’t Stop the Feeling!” from Dreamworks Animation’s Trolls. The film dramatizes the conflict that ensues when a group of ever-cheerful Trolls is kidnapped by the dour Bergen. The latter it seems only achieve happiness one day a year on Trollstice, an annual holiday where the Bergen feast on Trolls. Poppy and Branch, two trolls that survived the Bergen’s raid, set out to rescue their friends before it is too late.

“Can’t Stop the Feeling!” appears toward the climax in a scene where Poppy and Branch transform the Bergen’s holiday banquet into a big dance party. The song helps the Bergen realize that they can be happy every day of the year, not just on Trollstice.

Timberlake released “Can’t Stop the Feeling!” in May, about six months before the film’s debut. It went on to become the top selling song of 2016 racking up more than two million downloads. In writing it, Timberlake set out to create a modern disco song that would recall the ebullience and effervescence of the best dance music of the seventies. This proved important in matching its vibe to some of the older classics featured in Trolls, such as Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” and Earth, Wind, & Fire’s “September.”

In another year, the track’s enormous popularity and mad beats might easily carry the day. Yet, as a rule of thumb, feel-good songs haven’t fared too well in Oscar voting. There are exceptions, to be sure. In fact, the aforementioned “Under the Sea” and “Jai Ho” likely come to mind as fairly obvious examples. But, although feel-good songs are often nominated, the winners much more commonly are either love songs (“Take My Breath Away”, “Can You Feel the Love Tonight”) or “I Want” songs of the type David described as a typical element in Broadway musical song plots (“Fame”, “Glory”).

Indeed, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “How Far I’ll Go” from Moana is an almost textbook example of the latter. The song is featured in an early scene where the protagonist expresses her desire to explore the world beyond her Polynesian island, even though her duty to her tribe prevents Moana from sailing beyond the reef that her father’s decree establishes as a boundary.

Beyond its plot function, the song’s soaring chorus and uplifting key change beautifully express Moana’s hope and wonder about a distant world that she feels is her destiny. Miranda himself has said he went Method to connect to the character’s aspirations. He went back to his childhood bedroom to write the song. There Miranda recalled sensing a similar gulf in his own life between his love of home and family, on the one hand, and the inexplicable pull of a larger world beyond it, on the other.

With Moana conceived as the latest in a long line of Disney princesses, one could easily be cynical about the kinds of synergistic tie-ins that fuel the studio’s bottom line. But the film is tightly constructed and beautifully animated. Moreover, Miranda’s songs have the sort of wit and verve that makes him a worthy recipient of the torch passed on by Alan Menken, Howard Ashman, Tim Rice, Elton John, Stephen Schwartz, and Phil Collins. These songwriters spearheaded the resurgence of the animated musical and helped the Walt Disney Company rebuild itself from the ground up. With Miranda signed on to Disney’s reboot of The Little Mermaid, it appears that this is both the beginning of a beautiful friendship and the burnishing of an important legacy.

L. A. plays with itself: La La Land

The final two nominees come from La La Land. “City of Stars” is first heard when Sebastian is walking the boardwalk. It expresses his doubt about whether his budding relationship with Mia will end as yet another failed dream. This version of the song is low-key and a bit of a trifle. The song begins with a long, repeated piano vamp. The vibes and guitar then play its main motif before Sebastian eventually begins whistling its tune. And after one verse, the song comes to a tentative, softly longing cadence.

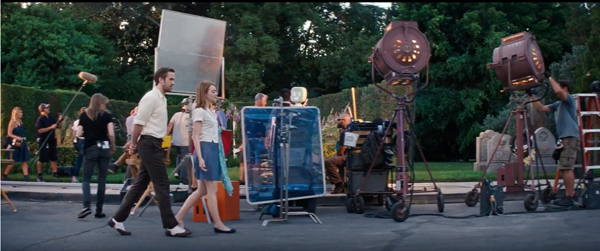

“City of Stars” returns, though, in a duet staged in Sebastian’s apartment. This is the version that Oscar voters likely will remember because it contains a more fully fleshed-out structure with verse, chorus, and bridge. Sung live on set by Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone, this rendition is a bit faster and contains a bigger emotional arc than the waterfront ersion. The lyrics begin just as they were when Sebastian sang them on the boardwalk. But lyricists Benj Pasek and Justin Paul add a new verse in which Mia refers to the couple’s first meeting in the club.

At this point in the story, the song appears to fulfill two functions. First, it takes stock of the couple’s relationship, encouraging the audience to revisit earlier scenes of the film. Secondly, and more importantly, the song encapsulates the intertwined dual plotlines so commonly found in classical Hollywood narratives. Here Mia and Sebastian seek the fulfillment of their professional ambitions in a way that matches the happiness they’ve found in their personal lives.

As Jenelle Riley notes in Variety, “City of Stars” has “become an anthem of sorts for the film.” And the big reason for this, I think, is that it best captures the film’s bittersweet tone. If you wanted to show someone a clip to give a sense of what the film is like, you’d probably pick the planetarium scene or perhaps the duet on “A Lovely Night.” But if you wanted to play something from the soundtrack to accomplish the same task, I suspect “City of Stars” is what you’d choose. The song won the Golden Globe a little over a month ago, and the fact that it’s been taken up as a stand-in for the film is a big reason why.

La La Land‘s second nominated song, “Audition (The Fools Who Dream)” is by contrast an iconic big number. As David pointed out in an earlier entry, in the Broadway musical song plot, this is usually a second-act showpiece that sets up the play’s final resolution. “Audition” serves a similar role in La La Land. It provides the key plot point that initiates the climax.

Furthermore, “Audition” evokes other “big numbers” from recent musicals. As an “actorly” moment for Emma Stone, it resembles Jennifer Hudson’s showstopper, “And I Am Telling You I’m Not Going” from Dreamgirls (2016), and Anne Hathaway’s heart-render, “I Dreamed a Dream” from Les Misérables (2013). As Kelley and Eric pointed out in last week’s blog, Stone’s performance was shot live just as Hathaway’s was a couple of years ago. The references to dreams in Stone’s and Hathaway’s songs offer a further connection..

Given its late appearance in La La Land, it doesn’t quite carry the same resonance that “City of Stars” has. Still, I think “Audition” will nonetheless play a part in Oscar voting by giving Stone a boost for Best Actress. Jennifer Hudson and Anne Hathaway both won Oscars for their roles. No doubt their “big numbers” helped their campaigns. Emma Stone seems poised to follow in their footsteps.

Prediction: I’m going out on a limb here, even though I definitely hear it creaking. “City of Stars” is the clear favorite, having already won awards at the Golden Globes and from several regional critics’ organizations. I think, though, there is a chance that “Audition (The Fools Who Dream)” acts like a third party candidate here, siphoning off just enough votes from “City of Stars” to allow a dark horse to win.

The dark horse? Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “How Far I’ll Go.” Given the potential for a La La Land sweep, this may not seem like the most rational choice. But I’ve stuck with the clear favorites the past two years without much success.

And there is an intuitive logic to support a surprise win for Miranda. Songs from Disney musicals have dominated the category, chalking up eleven wins since 1989. And Miranda has conquered all the other entertainment fields he’s entered. Why not the Oscars as well?

As I noted at the outset, Justin Hurwitz has a chance to join a small group of film composers who’ve taken home two or more Academy Awards in the same year. But Miranda has the opportunity to join an even more elite club, namely the EGOTs. (The term is an acronym for individuals who have won a Emmy, a Grammy, a Tony, and an Oscar.) After his extraordinary success with Hamilton, I predict that Miranda will add another trophy to his case.

But then again, maybe I’m just a fool who dreams of actually getting his Oscar picks right.

Very special thanks to Jon Burlingame, whose reportage has been extraordinarily insightful over the years. He has not only helped me in the writing of this blog, but his work also has informed my scholarly work on film music and film songs more generally. Burlingame’s own overview of the Oscar music nominees can be found here and here.

A hearty thank you as well to Eric Dienstfrey, who allowed me to bounce ideas off him and made some terrific suggestions in his own right.

Articles about the nominated composers abound on the internet. You can check an interview with Thomas Newman discussing his score for Passengers; an interview with Mica Levi on Jackie; two stories (here and here) about Nicholas Britell and Moonlight; two conversations (here and here) with Hauschka and Dustin O’Halloran about Lion. The Independent offers a track by track overview of La La Land’s soundtrack album. Justin Hurwitz also provides a summary of La La Land’s songs in this article from Variety.

Want to sample some of the nominated scores? YouTube offers the Passengers soundtrack, as well as an excerpt from the Moonlight soundtrack and a track from the Lion score. To get a sense of Mica Levi’s unusual glissandi technique, listen to the “Intro” of Jackie.

The coverage of the nominees for Best Original Song is almost as voluminous as that for Best Original Score. For a discussion of J. Ralph and Sting’s “The Empty Chair,” see this Variety article by Jon Burlingam, which also considers the increasing popularity of songs within the documentary format. This Los Angeles Times article discusses Justin Timberlake’s songs for Trolls, including “Can’t Stop the Feeling!”

On Indiewire Moana’s directors, John Musker and Ron Clements, discuss their collaboration with Lin-Manuel Miranda. Miranda’s own comments about his process on “How Far I’ll Go” can be found on the Trippin’ With Tara website.

For more on the development of “City of Stars,” see this Variety interview with Benj Pasek and Justin Paul.

Many of the nominated songs are featured in Youtube videos. “Can’t Stop the Feeling!” is here, and the scene from Moana featuring “How Far I’ll Go” is here. Lionsgate also has issued an official clip promoting “City of Stars.” It combines footage from both of the scenes in which it appears. “Audition (The Fools Who Dream)” is featured in a teaser trailer for La La Land.

For Jeff’s earlier Oscar music entries, go here and here.

P.S. 21 February 2017: Thanks to Fiona Pleasance for corrections! You can read her and her colleagues’ stimulating thoughts on La La Land at MostlyFilm. Their entry nicely fits with the discussions on our site.

Trolls (2016).

LA LA LAND: Singin’ in the sun

La La Land (2016).

DB here:

In our Film Studies program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, one of our aims is to integrate critical analysis of movies with a study of film history. Sometimes that means researching how conditions in the film industry shape and are shaped by the creative choices made by filmmakers. We also study how filmmakers draw on artistic norms, old or recent, in making new films. This effort to put films into wider historical contexts is something that you don’t get in your usual movie review.

Take, yet again, La La Land. Awards and critical debates continue to swirl around the surprising success of this neo-musical. Two entries on this blog have already considered what the film owes to 1940s innovations in Hollywood storytelling (here) and to more basic norms of movie plot construction and the classic Broadway “song plot” (here). But there’s plenty more to say.

Enter three Madison researchers as guest bloggers. Kelley Conway is an authority on the French musical from the 1930s to the present and author of an excellent book on Agnès Varda (reviewed here). She also gave us an earlier entry on films at the Vancouver Film Festival. Today, in an oblique rebuttal to some complaints about the principals’ singing and dancing in La La Land, she situates Damien Chazelle’s film within a trend toward “unprofessional” musical performance.

Eric Dienstfrey studies developments in acoustic technology and how those have affected the way movies sound. In his contribution, he traces how film’s recording methods shape the auditory texture of the numbers, with special attention to the soft boundary between diegetic (story-world) sound and non-diegetic sound.

Amanda McQueen is a specialist in Hollywood and TV musicals of the last fifty years. Here she considers how La La Land is designed to overcome audiences’ current resistance to “integrated” musicals. She proposes that it offers one way to revive the genre for modern Hollywood.

These experts take the conversation in new directions I think you’ll enjoy. They remind us that a movie coming out today automatically becomes a part of history; it’s just that the history is sometimes hard to discern. Along the way they show the virtues of thinking beyond the talking points put out by the PR machine or circulating endlessly in reviews. In my view, good film criticism involves ideas and information as well as opinions, and all three are on vivid display here.

Amateurism as authenticity

Everyone Says I Love You (Woody Allen, 1998).

Kelley Conway: For me, La La Land‘s references to classical Hollywood musicals and to the films of Jacques Demy provide a major source of its pleasure. (Sara Preciado’s video essay demonstrates the film’s homages) The film’s nods to other traditions remind us of something about the relationship between Hollywood and other national cinemas: mutual influence is the norm.

Directors associated with the French New Wave absorbed and subverted Hollywood genres. Hollywood directors of the late 1960s and ‘70s, in turn, were inspired by the narrative ambiguity and stylistic playfulness of the New Wave. Sometimes, the influence travels full circle in quite a direct way. John Huston’s Asphalt Jungle (1950) directly influenced Jean-Pierre Melville in the making of Bob le flambeur (1956), while Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs references both Melville’s minimalist gangster films and Hollywood heist films.

La La Land demonstrates a similarly rich exchange between Hollywood and France. In 1967, Jacques Demy’s Demoiselles de Rochefort paid loving homage to Hollywood films such as Singin’ in the Rain, West Side Story, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Chazelle’s film returns the favor, adopting the dancing pedestrians and location shooting of Demoiselles and the saturated colors, recitative, and downbeat ending of Parapluies de Cherbourg. Chazelle is equally smitten with classical Hollywood; La La Land brims with references to the choreography, costumes, and set design of Shall We Dance (1937), Singin’ in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), West Side Story (1961), and many others.

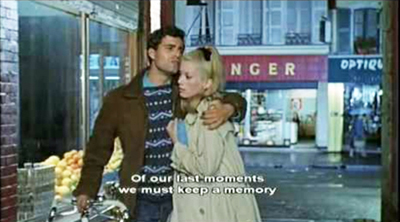

La La Land not only cites the style of other musicals, it also develops and tweaks narrative elements from older musicals in interesting ways. For example, Chazelle’s film, like Demy’s Parapluies de Cherbourg, thwarts the creation of the couple. In Parapluies, the Algerian war initially separates Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve).

Later, an unplanned pregnancy and her mother’s machinations push Geneviève to marry a wealthy jeweler. At the end of the film, when they run into one another at Guy’s gas station, they exchange only a few perfunctory words; Guy even declines Geneviève’s invitation to meet their daughter. There is neither anger nor the warmth of nostalgia in their exchange; just a delicately drawn emotional distance that leaves viewers feeling wistful.

In contrast, the relationship between Mia and Sebastian fails because they decide to put their romance on hold in order to pursue their dreams. “Where are we?” Mia asks Sebastian after her audition for the film role that will take her to Paris and launch her career. “We’ll just have to wait and see,” he replies. Five years later, he owns a jazz club and she has become an A-list actress, but she is married to someone else and has a child.

When they cross paths at his club, Chazelle supplements Demy’s delicate gas station meet-up with an exuberant fantasy montage, a kind of dream ballet often used in the classical Hollywood musical, in which the couple manages to stay together. The production number is full of invention and energy, combining animation, simulated home movie footage, a trumpet solo, and a tribute to the “Broadway Melody” number of Singin’ in the Rain. As Mia prepares to leave the club, she and Sebastian exchange tender glances and rueful smiles. She departs as he launches into his next song. The love is still there, the film suggests, but Sebastian and Mia chose art over love and they would probably make the same decision today. Different from Demy’s characters, Sebastian and Mia are not victims of implacable destiny, but committed artists. It’s an ending that feels fresh to me.

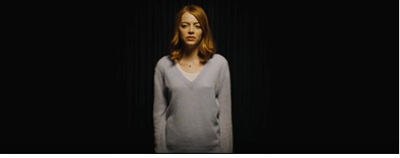

As Amanda McQueen reveals below, La La Land conforms to various trends in the 21st century musical. Consider just one element: song performance. Neither Ryan Gosling nor Emma Stone possesses a powerful, belt-it-out voice. Instead, much of the singing in La La Land is modest, thin, and breathy. Take, for example, the number “The Fools Who Dream,” a climactic moment in the film.

Asked by the casting director to tell a story, Mia begins a poignant monologue (“My aunt used to live in Paris…”) in a quiet speaking voice marked by a bit of vocal fry. She slowly moves into an a capella ballad and, after a few bars, is accompanied by piano. Eventually, the music swells, Mia goes big (“Here’s to the ones who dream…”), and then the song winds back down to the concluding notes, delivered a capella. The staging of the song – black background, circular camera movement, a big swell of emotion, a long take – is reminiscent of the splashy production number in Agnès Varda’s New Wave masterpiece Cléo de 5 à 7. But Stone’s voice reminds me of the wonderfully whispery, intimate singing voices of Birkin, Bardot, and Karina.

As Eric Dienstfrey points out below, the techniques used in the recording of the songs affect our impression of the story world and our sense of the film’s aesthetic achievement. In a Song Exploder podcast about the creation of this song, composer Justin Hurwitz emphasizes the difficulty of shooting this one-shot production number. He explains that Stone performed the song live on set, as opposed to lip-synching it. Hurwitz speaks of his struggle to keep up with Stone while accompanying her on set:

Because I was letting Emma lead the song, I was reacting to her. So a lot of times the piano is a little bit behind the vocal. It sounded like a recital or something where you know the singer is leading it and the piano is there to accompany. That’s what happens when two people make music together; things are not perfectly in sync. That’s why it feels musical and why it feels real and honest.

Directors of many recent film musicals similarly seek to create the impression of aural and emotional authenticity, either through non-professional singing or on-set recording. Woody Allen’s musical Everyone Says I Love You (1996) employs actors who are not professional singers, and Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001) uses the relatively modest singing talent of Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor in a mixture of playback and live recording. Likewise, publicity for Les Misérables (2012) made much of the fact that Anne Hathaway, Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe performed their songs on the set.

Christophe Honoré also tends to employ singing performances by non-singers. Here, in Dans Paris (2006), a couple breaks up over the phone while singing in a breathy, halting fashion.

For his musical Pas son genre (aka “Not My Type,” 2014), Belgian director Lucas Belvaux cast Emilie Dequenne (of Rosetta fame) as a karaoke-singing hairdresser who woos a philosophy professor. Belvaux insisted that Dequenne avoid taking lessons so as to preserve the imperfect quality of her singing voice. Here, Jennifer (Dequenne) and her pals rehearse the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love”:

There is, in fact, a broad spectrum of singings styles and capabilities used in contemporary film musicals. In La Captive (2000), Chantal Akerman employs an aria from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Two women sing to one another flirtatiously from their windows across an apartment courtyard without accompaniment. One woman is a trained opera singer, while the other, the film’s elusive female protagonist (Sylvie Testud), is untutored. The contrast in the women’s voices provides an unexpected pleasure.

The use of the modest singing voice by Chazelle and others to convey emotion and authenticity is quite different, for example, from Alain Resnais’ use of song in On connaît la chanson (aka “Same Old Song,” 1997). Here, fragments of songs spanning the history of twentieth-century popular French chanson are lip-synched by actors. Like Dennis Potter, whose Singing Detective (1986) inspired On connaît la chanson, Resnais foregrounds the artificiality of dubbing. This creative choice works against the traditional commitment in film musicals (and in sound cinema more generally) to the impression of fidelity and authenticity. Here, Josephine Baker’s delicate singing voice is grafted onto the body of a Nazi commander. The humor in non-synchronization loops us right back to Singin’ in the Rain.

Directors of contemporary film musicals did not pioneer the use of the untrained singing voice. As Jeff Smith reminded me recently in an email, “There is a long tradition of celebrating the raw, unpolished singing styles of rock and rollers, dating back at least to the time of Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan and Roger Daltrey, and using those marks of authenticity as a means of distinguishing them from pop performers.” Unlike the musicians of rock and punk, though, Chazelle doesn’t seem particularly interested in denigrating pop music. He clearly loves John Legend’s musical performances in La La Land and those 1980s pop tunes he pretends to mock.

Many have criticized La La Land’s singing, but in fact, Chazelle is operating well within the tradition of employing imperfect vocalization to connote realism and to convey emotional power. The modest singing voices add another dimension to Chazelle’s participation in the ongoing conversation between Hollywood and French cinema.

La La canned vs. La La live

Eric Dienstfrey: I agree with Kelley’s observations about the remarkable number of cinematic references in La La Land. For example, the opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” embeds a host of influences within Chazelle’s mise-en-scène. For me, this exit-ramp romp immediately recalled the ferry ride in Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort and the traffic jam in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend. Amanda McQueen, below, notes how the scene reminded her of the films of Vincente Minnelli. And as Chazelle himself indicates, one might even see traces of Rouben Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Thanks to such references, we can consider the significance of La La Land’s numbers as extending well beyond Justin Hurwitz’s melodies and Benj Pasek’s and Justin Paul’s rhymes. The film’s allusion to Rear Window, for instance, may encourage audiences to compare the onscreen chemistry between Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling to that of Grace Kelly and James Stewart. To catch these subtle references, filmgoers need to pay close attention to the camerawork, the staging, the costumes, and even the choreography. Similarly, we can discover new layers of meaning by analyzing its songs and their sound designs.

How many ways are there for sound technicians to record and mix a musical number? Quite a few, it seems. One basic way is to record the vocal performances live on the set. During the earliest years of talking pictures, this technique often required the presence of an on-set orchestra to provide accompaniment from behind the camera. More recent strategies, however, merely ask singers to wear small earpieces that play pre-recorded accompaniment.

Another option is for technicians to record the vocal performances in an acoustically controlled studio and then mix these recordings into the final film. Sometimes technicians will record the studio performance before filming, and then require actors to lip-synch to playback on the set. Other times, technicians will ask the singers to perform the song live on the set, but then use a studio recording in the final mix due to unforeseen circumstances.

In some instances, the set might be too noisy to record a clean vocal performance, or the dance number might be so physically demanding that the actor can’t help but introduce heavy breathing and other vocalized efforts. A live recording may be ideal, but the studio recording is often the more practical solution.

The musical numbers in La La Land display both recording techniques. Some were recorded live—such as “Fools Who Dream,” which Kelley discusses above—and some were recorded in a separate studio—such as “Another Day of Sun.” Steven Morrow, the film’s sound mixer, suggests that each choice was informed by various practical concerns. The acoustics along the exit ramp, for instance, reportedly made it too difficult to record live singing.

Such concerns even led to strange incidents where a single song would contain a mixture of both live and studio recordings. Morrow notes how “Someone in a Crowd” relies upon Emma Stone’s live recordings, while studio recordings were used for the other actresses. This decision to blend together live and studio recordings can become a storytelling device—say, if the director wants to create a contrast between two or more characters—but for most songs, the choice to use either technique is generally determined by shooting conditions and budgetary considerations.

Still, can the acoustical differences between live and studio recordings function beyond practical filmmaking needs? It is worth noting that both techniques parallel another cinematic binary: diegetic sound and non-diegetic sound. Diegetic sound commonly refers to all the dialogue, effects, and music that emanate from sources within the film’s setting, such as radios and footsteps. Non-diegetic sounds are those added to the story world as a form of commentary, such as a moody orchestral score. As many film scholars rightfully argue (here and here), the diegetic/non-diegetic binary is not perfect, but for the vast majority of films the distinction remains a useful initial categorization for sound’s narrative functions.

Musicals are an exception. In his groundbreaking study of Hollywood musicals, theorist Rick Altman argues that the clean distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound breaks down during moments when characters burst into song. Specifically, the interaction between diegetic singing and non-diegetic musical accompaniment lifts characters out of the story world toward fantastic settings. Consider Elvis Presley’s performance of “I Can’t Help Falling in Love with You” from Blue Hawaii.

Presley begins the song while accompanied by a small on-screen music box. But during his performance something interesting happens: the sound of the music box fades into the background while the drums and guitars of a non-diegetic orchestra magically appear. For Altman, this audio substitution is critical to understanding how the musical genre operates:

We have slid away from a backyard barbecue in Hawaii to a realm beyond language, beyond space, beyond time. […] We have reached a ‘place’ of transcendence where time stands still, where contingent concerns are stripped away to reveal the essence of things.” (66)

In other words, this dissolve from the music box to the orchestra tells us that Elvis… well… has left the building. He has transcended the purely diegetic universe of the film’s story-world reality, and has temporarily entered a non-existent space that is supra-diegetic fantasy.

Altman’s observations apply to La La Land as much as they apply to Blue Hawaii. When Mia and Sebastian sing “A Lovely Night” while searching for their cars, the non-diegetic accompaniment fades in and the two characters interact with the music through song and dance. In turn, Mia and Sebastian transcend Los Angeles and enter a supra-diegetic universe. This diegetic boundary crossing is punctuated further by their stroll through Hollywood’s hills, a vantage point which allows Mia and Sebastian to literally look down upon the city as they chart this transcendence.

Yet La La Land is more than just a pastiche of earlier musical traditions. It also demonstrates how different recording techniques can be thematically integrated within the film’s narration. Here we might once again compare the playback of “Another Day of Sun” to the live recording of “Fools Who Dream.” Both numbers are similar in their reliance upon non-diegetic musical accompaniment, yet the production process creates contrasting narrative implications.

“Another Day of Sun” was recorded in a studio, and the acoustical details of this studio environment—namely frequency response, microphone placement, reverberation time, and overall cleanliness of the recording—are remarkably distinct from the those of an outdoor location. These subtle textural differences produce the sense that the performers’ voices have left the diegetic space of the freeway and traveled to an unseen studio for the song’s duration.

“Fools Who Dream” has the opposite effect. It was recorded live, and throughout the scene the acoustical details that shape Stone’s voice never really change. The sonic signature of the room remains audible in her vocals from the time she introduces herself to the casting directors, to the time she finishes singing. As a result, Mia does not transcend the story world; instead, the non-diegetic piano and orchestra seem to materialize inside the room.

These two examples demonstrate how alternative recording techniques offer filmmakers different ways for characters and accompaniment to interact. Studio recordings specifically lift the vocals up toward the space of the non-diegetic accompaniment, whereas live performances can pull traditional musical accompaniment down into the story world. Both techniques defy the norms of realism, yet their production differences render each vocal performance with unique narrative weight. And for La La Land—a musical about two artists who wish to become famous stars while simultaneously remaining pragmatic and down-to-earth—the ways Mia and Sebastian interact with musical accompaniment can reveal if and when the characters are grounded in reality or lost in fantasy.

As criticism surrounding contemporary musicals would suggest, Hollywood routinely favors live performances over other techniques. Live performances are not only valued for being more authentic, they are harder to record and, thus, a more prestigious cinematic accomplishment. This preference for live recordings, however, need not dictate how all musicals are made. A creative integration of both live and studio recordings can open up storytelling possibilities for the sound technicians and directors who wish to innovate within the musical genre.

Yes, I know: it seems unlikely that many filmmakers will play with these acoustical parameters in their movies. Nonetheless, La La Land’s sound design points to the possibility that at least a few musicals will create rewarding experiences not just for visually minded historians, but for audiophiles as well.

A musical without quotation marks

Amanda McQueen: Much of La La Land’s critical reception has focused on its relationship to film musicals of the past. As Kelley, Eric and David have all noted, much of the film’s meaning derives from its citation and revision of film and stage musical traditions. But what’s the status of La La Land as a musical in the 21st century? How does this shape the film’s approach to the genre’s conventions?

The early 2000s witnessed a minor revival of the Hollywood live-action musical, a genre that had been considered box office poison for several decades. But despite the renewed interest in musicals, producers worried that contemporary audiences no longer accepted one of its key conventions: the integrated number.

Integration commonly refers to those moments when characters spontaneously burst into song to express feelings or advance the plot, usually accompanied by sourceless music, as Eric points out above. Not all musicals have integrated numbers, but many critics and scholars assume that integrated musicals constitute the genre’s core. Audiences, however, were assumed to find this particular break with cinematic realism both antiquated and alienating. Moviegoers would suspend disbelief to accept lightsabers, superheroes, and wizards, but someone walking down the street and singing—no way!

Fear of the integrated number has caused many contemporary musical films and television shows to distance themselves from this convention. Some musicals ensure the song-and-dance numbers are otherwise motivated. In Chicago and Nine (2010), all the songs are figments of the characters’ imaginations, while Dreamgirls (2006) transformed the integrated numbers of the Broadway original into diegetic stage performances.

Other musicals, including Enchanted (2007), The Muppets (2011), Annie (2014), and Pitch Perfect 2 (2015) opt for comic reflexivity, using integrated numbers to comment on their very artifice. The campy medieval musical Galavant (ABC 2015-2016) is perhaps the epitome of this technique. The lyrics of the second season’s opening number, for instance, address the series’ unexpected renewal (“Give into the miracle that no one thought we’d get”); the excessive repetition of the theme song in the previous season (“It’s a new season so we won’t be reprising that tune”); and a perceived lack of motivation for musical performance (“There’s still no reason why we bust into song”). The four-minute ensemble song-and-dance concludes with Galavant (Joshua Sasse) commenting with satisfaction, “See, now that was a number!”

Over the years, concern over audience acceptance of the integrated musical seems to have abated, particularly for Broadway adaptations. But it hasn’t disappeared, as La La Land’s critical reception makes evident. Articles on the film have routinely stressed that musicals are “an extinct genre,” that “some moviegoers may, no doubt, feel a little tentative about the genre,” and that musicals are no guarantee at the box office. Manohla Dargis’ review in The New York Times, aptly titled “‘La La Land’ Makes Musicals Matter Again,” discusses this issue at some length. She explains how “For decades, the genre that helped Hollywood’s golden age glitter has sputtered,” reappearing only in Broadway adaptations or diluted (read, non-integrated) forms, and that as a result, “Musicals have been for kids, for knowing winks and nostalgia.”

What perhaps feels so novel about La La Land is its sincere approach to the “old fashioned” integrated musical form. As writer/director Damien Chazelle told Hollywood Reporter:

On the screen, there is this big gap right now that you have to cross to do a musical. At least an earnest musical, where you’re not immediately putting quotation marks on it.

With its opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” La La Land unabashedly announces that this is an integrated musical, and it never qualifies that position. There are no cheeky winks at the camera, no characters asking why they’re singing to each other, and most of the songs function as pure expressions of thoughts and feelings. Mia and Sebastian are real people in a modern city, who just happen to be singing and dancing and falling in love. For Chazelle, “Another Day of Sun” functions as “a warning sign to people in the audience. If people are not going to be comfortable with it, they’ll leave right away.” La La Land thus almost dares audiences to accept and celebrate this unrealistic cinematic convention, and for a 21st century musical, that’s a somewhat rare approach to take.

Yet La La Land has its own methods of rendering the integrated musical acceptable for contemporary audiences. First, there is its obvious nostalgia. La La Land’s visual style—35mm, CinemaScope, long takes and long-shots scaled to choreography—and its many allusions create a critical distance, an awareness that this type of cinema is a relic of another age. It’s not so much a throwback to studio-era musicals as it is a modern version of the auteurist musicals of 1970s New Hollywood (most of which were also resistant to the traditional integrated number). Indeed, La La Land has been compared to Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) or Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart (1981).

I think it’s also akin to Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend (1971), which has a lighter tone and takes a similar approach to its citations. Russell updates Busby Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic stagings with color and widescreen, and Chazelle updates Vincente Minnelli’s sequence-shots with a Steadicam. Like The Artist (2011), which tutored modern viewers in the conventions of silent cinema, La La Land is an affectionate lesson in a mode of filmmaking that is not likely to return.

Then there’s the ending, in which Mia and Sebastian find success in their artistic pursuits, but only because they have parted romantically. As Kelley explains, La La Land owes its bittersweet ending to Jacques Demy’s Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). This gives the film a melancholy at odds with the studio era Hollywood musicals it so frequently references—films like An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), in which the couple lives happily ever after. By eschewing the union of its romantic couple, La La Land tempers the artifice of the integrated musical with a more realistic narrative, one that acknowledges that life does not always work out exactly the way we want. Such a conclusion is far more typical of American independent cinema than it is of the classical Hollywood musical.

Significantly, La La Land does give us a traditional happy ending, but through the device of the dream ballet. One of the most overtly stylized conventions of stage and screen musicals, dream ballets generally function to convey character subjectivity, and they allow for especially abstract mise-en-scène. La La Land tackles this generic trope with the same sincerity it displays in its handling of integrated numbers.

Set to a medley of the film’s musical themes, the sequence functions much like that in An American in Paris, arguably the most famous cinematic dream ballet. The sequence recaps the characters’ emotional journey and romantic relationship entirely through dance. Yet while the ballet in Paris shows a stylized version of what has actually occurred, La La Land’s presents an alternative reality where Sebastian and Mia stay together while also achieving their artistic goals. As Owen Gleiberman puts it in Variety, this “the very movie we would have been watching had ‘La La Land’ simply been the delectable old-fashioned musical we think, for an hour or so, it is.” In the end, though, the film affirms that Mia and Sebastian’s happily-ever-after is only a fantasy; when the dream ballet ends, the two part ways.

The first time I saw La La Land, I found myself daring Chazelle to subvert my expectations and use the dream ballet as a device to create a happy ending. Instead of concluding the fantasy sequence with a return to reality, I hoped the dream ballet would function to re-write the narrative. To my mind, turning the imagined world of the dream ballet into the characters’ actuality would have been an interesting twist on how this device usually functions. At the same time, it would have more radically embraced the integrated musical tropes the film otherwise celebrates.

Yet I suspect viewers would have found this ending contrived, and it would have been. La La Land’s critical and commercial success, I think, has depended on it keeping the model of the classical Hollywood integrated musical slightly at arm’s length. The film’s unique combination of nostalgia and realism is clearly resonating with modern audiences, but it’s also in keeping with the larger approach to the integrated musical in the contemporary moment. As long as film musicals are considered risky properties, certain forms of the genre will likely have to be relegated firmly to the past.

Kelley Conway is a Professor in our department and winner of a Distinguished Teaching Award. She has written Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in 1930s French Film (University of California Press), Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press), and essays on classical and contemporary French film. She is currently at work on a book about postwar French film culture.

Eric Dienstfrey is a doctoral candidate in our department. His dissertation traces how theories of acoustical fidelity shaped stereophonic technology from 1930 to 1959. Eric’s research interests include silent film musicians and the cultural history of dictaphones. He recently received the 2017 Katherine Singer Kovács Essay Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Amanda McQueen, a Faculty Assistant in our department, finished her Ph.D. in 2016. Her dissertation is titled “After ‘The Golden Age’: An Industrial History of the Hollywood Musical, 1955-1975.” It examines how the breakup of the studio system helped create several musical cycles, each aimed at a niche audience, and each designed to prolong the genre’s viability in the new marketplace. Apart from studying musicals on stage, screen, and TV, Amanda’s interested in media industries, film technologies, and genre theory and history.

Thanks as well to Jeff Smith for his comments on these entries. Watch for his annual blog entry (first two, here and here) analyzing the Oscar-nominated songs and scores.

La La Land.

How LA LA LAND is made

La La Land (2016).

The formal method is fundamentally simple. It’s the return to craft (masterstvo).

Viktor Shkovsky, 1923

DB here:

Not how it was made. We’ll get “The Making of La La Land” as a DVD bonus, and there are already behind-the-scenes promos.

No, this is about how it is made.

On this site, we mostly practice a criticism of enthusiasm. We write about what we like, or at least about films that intrigue us from the standpoint of history or aesthetics. Sometimes, what interests us intersects with a current controversy. Take La La Land.

Some of my cinephile friends disapprove of it. It swipes too much, they say, from classic studio musicals and the work of Demy, and it doesn’t live up to either model. But tastes change. I remember when the classic musicals that we venerate were considered fluff, and I recall how Demy’s films, especially Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, were held at arm’s length by many of my 60s pals. “He tries too hard,” a friend remarked. Some say that about Chazelle, and perhaps in a few decades La La Land will be remembered fondly.

In any case, I’m not aiming to denounce this ambitious, agreeable film. I’m more interested in asking how La La Land accords with the craft of studio musicals and Demy’s efforts. I’m also interested in tracing its affinity with a third tradition of song-and-dance: the Broadway show.

Along all three dimensions, I hope to take Shklovsky’s advice and ask about craft. La La Land is both derivative and original. Actually, most movies are, though in various proportions.

The song plot

If we want to understand how film form and style work, we can’t neglect the nuts and bolts of moviemaking. In trying to achieve particular effects, filmmakers have created craft traditions, favored options bounded by loose limits. Mostly these traditions grow up intuitively, as solutions that just feel right. In any case, behind the cluster of preferred practices we can often find principles of design and execution that can be made explicit.

A lot of what Kristin and I have been doing since the 1970s consists of trying to bring to the surface filmmakers’ underlying habits and conventions. Those help shape how viewers respond to films. We aren’t maniacs for systematization—art can’t be utterly systematized—but as analysts we want to discern patterns of story and style, what earlier entries have called schemas. And as historians we want to understand how patterns of story and style get passed down from earlier films, and passed around among contemporaries.

For example, some narrative schemas of American studio cinema are what I aim to lay bare in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. Without invoking the big guns of theory, I try to point out how craft traditions of plotting and narration got recast in those crucial years. A recent entry hereabouts tries to show the legacy of those years surfacing in current releases, La La Land included.

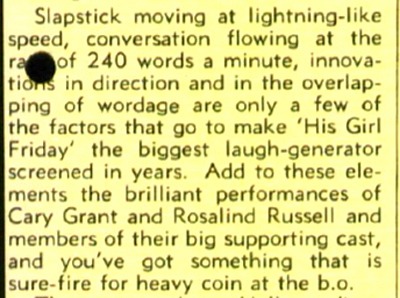

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

What Viertel brings to the table is the “song plot,” a sequence of musical numbers that has become conventional in Broadway shows. Often, of course, many numbers enhance the dramatic action, but sometimes they’re inserted for a change of mood or a burst of energy. The song plot both echoes the action plot and provides its own arc of pleasure, with musical numbers that may be more or less extraneous to the main action.

What makes Viertel’s anatomy of shows interesting is that even the narratively “irrelevant” numbers tend to occur in the same spot from show to show, and they have a common emotional quality. They aren’t just “spectacle interrupting narrative,” to use a film-studies commonplace. As spectacle, they have their own pattern, and that’s gratifying alongside the pleasures of the story. Viertel’s macro-schema is probably known to many insiders and fans, but it was all news to me, and it helps me understand the musical spine of this recent movie.

Hence today’s title, of an entry that is 100% spoiler-filled. I’ll consider La La Land as a classically constructed film. Then I’ll test its “making” against Viertel’s template of a musical. I conclude with some remarks on how analyzing these patterns highlights the movie’s variance from adjacent traditions.

From meet-cute to remeet, and re-remeet

Start with the Hollywood plot structure. Kristin has argued that even though mainstream American screenwriters sometimes claim to be following a three-act plot model, their craft practice often pushes them to a four-part schema. (She has discussed this here, and I’ve given examples here and here.) Specifically, the long second “act” is usefully thought of as two separate parts split by the film’s midpoint.

The conventional plot pattern consists of a Setup in which protagonists define their goals; a Complicating Action that redefines those goals; a Development that muddles, delays, or intensifies the goals; and a Climax that resolves them. These parts typically run 20-30 minutes, and films of varying lengths, long or short, can include more or fewer parts than these four. In most cases there will also be an epilogue or “tag.”

La La Land runs almost exactly 120 minutes, not counting the opening logos or the end credits. The Setup (running 25 minutes) establishes Mia and Sebastian as dual protagonists, caught in the midst of the initial traffic jam.

We then follow Mia through her day as a barista, her failed audition, her return to her apartment, and her agreement to go out to a networking party with her flatmates.

A flashback returns us to the traffic jam, and now we follow Sebastian to his apartment, where in a parallel to Mia’s day he makes coffee, rummages through unpaid bills, and talks with his sister. He goes on to his job as pianist playing Christmas music at a cocktail bar. Mia, who’s come in by accident, stands before him, moved by his switch into improvised jazz. But Sebastian is fired, and disgruntled, he coldly bumps past her.

The Complicating Action starts after Mia fails another audition. She goes to a pool party and sees Sebastian in the ensemble. She teases him, and they leave the party together. Although there’s friction between them, they start a friendship. They confess their dreams: she wants to be an actress and he wants to start a club that hosts classic jazz.

Mia absentmindedly agrees to go to a movie with him on a night she has a date with her boyfriend. But she’s haunted by Sebastian’s music and she finds him at the theatre, watching Rebel without a Cause. They go to the planetarium featured in the film and kiss. At the end of the Complicating Action, about 60 minutes in, Mia resolves to write a one-woman show for herself.

The Development is the stretch where backstory is introduced, obstacles create delays, and subplots intertwine with the main action. Since in La La Land the romance seems solid (there are no love rivals), and there are no secondary characters of consequence, the film is devoted to the other major plotline: the obstacles encountered in our couple’s quest for success. Those in turn affect the romance.

A Development also typically relies on montage sequences, and we get plenty here. Mia works on her show, while Sebastian is offered a chance to join his friend Keith’s combo. To stabilize his life with Mia, he takes the job.

Soon he’s on tour, and the band finds some success, though he’s compromising his principles. “Do you like the music you play?” Mia demands, and he evades answering. The crisis comes when a photo shoot delays his arrival at her premiere, which is a fiasco.

Mia declares: “It’s over”—meaning both her career and their affair. She goes back home. We’re at the 90-minute mark.

We’re ready for the Climax, which is often driven by a deadline. Sebastian takes the call asking Mia to audition, and he rushes her back to it. She gets the part, and the two of them decide to wait and see how their relationship develops.

Five years later, Mia is now a success. This seems an abrupt, even anti-climactic turn of events, coming only eleven minutes after the Climax started. Apparently, despite their declarations of undying love, the couple’s romance was never rekindled. We see Mia visit the café where she was once a barista and return to her hotel and her husband and daughter. Her activities are crosscut with glimpses of Sebastian alone in his apartment. In effect, this passage balances our alternating introduction to the couple during the Setup.

Mia and her husband drop in on a club that turns out to be Sebastian’s. Mia and Sebastian eye each other longingly. Mia watches him play Their Song, and this launches an apparently shared fantasy of an alternate-world climax and resolution.

There’s a replay of the two of them at the cocktail bar, but this time Sebastian doesn’t brush past her. They kiss passionately. After this what-if premise, the race to the audition is replayed in stylized form, and the trajectory of Mia’s career—going to Paris, finding screen success, forming a family—is reenacted with Sebastian as her mate. At the end, Sebastian, not her husband, is sitting with her in the club (listening in effect to himself), and they kiss.

This soufflé of flashbacks and fantasies ends the plot on the conventional romantic clinch. But the film’s tag, of course, is their return to reality and the sad smiles shared as she goes off with her husband. In all, this double climax/ resolution turns out to run almost thirty minutes, which would be unusually long for a non-musical.

As is customary in Hollywood narrative, motifs and parallels crisscross the film. The opening song on the freeway lays out hints of what is to come. The sequence alternates a woman singing about a career as a film star (“It called me to be on that screen”) and a man singing about a career honoring old music (“ballads in the bar rooms left by those who came before”). Anticipating the finale, the woman’s song includes mention of a boy seeing her on the screen and remembering that he knew her.

More parallels and rhymes follow. Mia nearly stands up Sebastian on their date; he misses her show. Each encourages the other to keep struggling. Mia’s blockhead boyfriend anticipates her eventual GQ husband, as if she has decided not to go for the edgy type Sebastian is. The motif of Mia’s beloved aunt, who inspired her love of movies and her urge to act, gets dramatized twice, once in her one-woman show and more successfully in her audition song, “Here’s to the Ones Who Dream,” which wins Mia the movie part.

So many things are doubled that it’s not surprising that the Setup parallels each protagonist’s day and establishes the crucial moment at the supper club. That too gets replayed—once in the real world, as she and her husband hear Sebastian’s performance of his tune for her, and once at the start of the fantasy projection of their future, which becomes a replay of her actual life with her husband.

So far, so classical. But—duh, as they say–La La Land is also a musical.

That’s the Broadway melodies