Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

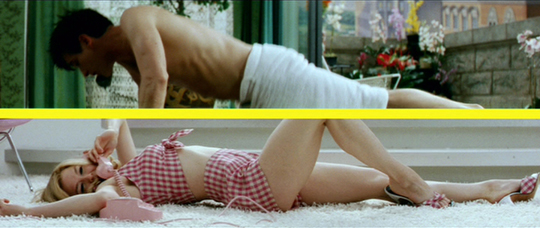

Fantasy, flashbacks, and what-ifs: 2016 pays off the past

La La Land.

DB here:

After I see a new movie, I like thinking about its ties to film history. This isn’t a matter of sneering, “They did it better in the old days,” though often that’s true. Rather, I like exploring how our films both rely on and swerve from the traditions they invoke.

I’m not talking only about movies that self-consciously point at Hollywood’s past, as La La Land does. Every new release participates in film history—and sometimes changes it. Most critics don’t have the space or inclination to point this up, but those of us who study film as an art can. Looking closely at form and style makes the past present to us in a vivid way.

Students are taught that in the 1910s Griffith took crosscutting to a new level, and true enough. But it’s not often mentioned that crosscutting has remained a permanent expressive option for filmmakers today. Very often they use it as Griffith did: to build tension, especially in a chase or a race against time; or to highlight narrative parallels, as he did in Intolerance. What excites young audiences in the work of Christopher Nolan, for example, are in large measure smart elaborations on principles that go back a hundred years.

This isn’t to complain that Nolan isn’t original—originality in the strong sense is very rare—but rather to point up an overarching dynamic of continuity and change across the history of the art. We understand what Nolan’s doing better when we see how he recasts inherited techniques, as when Inception takes parallel crosscutting to a kind of limit in its embedded dreams.

My upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, is an effort to refine an argument I made in The Way Hollywood Tells It: that major narrative techniques of contemporary cinema got consolidated in the 1940s. The techniques I have in mind include general principles like non-chronological plotting and subjective probing of character’s experience, as well as particular devices like flashbacks, voice-over, and fantasy scenes.

I say “consolidated” because many of those strategies can be found sporadically in the silent era and the 1930s. Forties writers and directors adapted them to the sound cinema, made them popular, and explored them in ways that go beyond most earlier instances. These filmmakers added a body of resources to the classical tradition: after the 1940s, later filmmakers could develop the techniques in fresh ways. There were new colors on their palettes.

I talk about several films, and among those I significantly spoil The Shallows, Manchester by the Sea, The Birth of a Nation, Nocturnal Animals, Moonlight, and La La Land. But you should be able to skip the films you fear I’ve overshared on.

Schemas and their sneaky ways

Reinventing Hollywood argues that we can understand the process as one of schema and revision. I borrow from E. H. Gombrich the idea that a schema is a pattern handed down by earlier artists that becomes a point of departure for those who follow.

For example, shot/reverse-shot cutting is a stylistic schema, going back to the 1910s. Every professional filmmaker knows how to execute it, though some will find fresh ways to use it. The Shallows, a summertime thriller from the talented director Jaume Collet-Serra, uses it in orthodox ways throughout.

Most filmmakers apply the shot/reverse-shot schema to phone conversations as well. But here Collet-Serra innovates (mildly) by using cellphone technology to give us a phone conversation with a redoubled shot/reverse-shot pattern. The editing schema is given within a single frame as Nancy talks with her father.

This isn’t, I think, a mere gimmick. For one thing, we’re primed for it by the scene of Nancy’s arrival, when she browses through photos of her dead mother. Those are delivered to us as paste-ups in the same frame, rather than as optical POV shots of Nancy’s phone. Soon after, still during her ride to the beach, we see an instant message from her friend.

So the pseudo-shot/reverse-shot has been prepared for by these other displays of her screen. We’re ready for this to be an intrinsic norm of this film. Later we’ll get the ticking-clock deadlines through inserts of of her watch.

More generally, the film as a whole tightly restricts us to Nancy’s experience. Nearly everything we see and hear is filtered through her consciousness. (The film’s momentary detours from her range of knowledge work to maximize suspense, in the manner of the bomb under the table.) During the phone conversation, cutting back to her father at home in Galveston would have made him a more important character. As it is, the narration keeps the emphasis on her situation and the beautiful but menacing landscape, the “perfect beach” that she needs to conquer as her mother did.

Shot/reverse-shot is a schema for handling stylistic options. I suggest that there are narrative schemas too, tried-and-true storytelling patterns that filmmakers can repeat, reject, or revise. Novelty builds on familiarity. As Damien Chazelle describes La La Land: “I’m trying to hark back to certain old traditions but hopefully show you something you haven’t seen before.”

For the viewer, schemas supply a certain predictability. We’re used to the back-and-forth of shot/reverse-shot cutting. Likewise, we expect a flashback to supply background information that clarifies the situation in the present. In the American studio tradition, a filmmaker who revises a schema needs to give us enough of the pattern to make us realize the alterations. The Shallows‘ revision of shot/reverse-shot is clear to us because, given our knowledge of FaceTime/Skype technology, we can grasp the images as diagrammatic presentations of a familiar editing pattern. Similarly, we can sense a flashback even when it’s quick or cryptic, and we anticipate that things will clarify later. The dynamic of familiarity and novelty will work only if the the new twist plays off something recognizable.

Back in September, I noted that almost every film I was seeing seemed indebted to 1940s storytelling, but I talked only about Sully. Today I go wider and look at several 2016 films, both pop and prestigious, that rely on methods of roundabout storytelling that coalesced back then. We’re so used to these methods that we tend to forget their debts. By analyzing how our writers and directors draw on this tradition, we better understand their roots in film history–and their genuine contributions to changing it.

In her, and his, shoes

One of the most taken-for-granted narrative strategies is that of subjectivity. Here filmmakers use images and sounds to reveal a character’s mind and senses. The main schemas have become very familiar.

Today we scarcely notice optical POV shots or fantasy imagery. They were common in silent film, became less common in Hollywood in the 1930s, and grew very common in the 1940s. The sustained optical POV of Lady in the Lake (1947) is one instance, and so are the protracted dream and delirium sequences in psychological films like Spellbound (1945) and The Lost Weekend (1945).

Go back to The Shallows and you’ll find plenty of POV shots. When Nancy regains consciousness after the climax, we get a mixture of optical viewpoint and imaginary shots, when she first sees Carlos and then “sees” her mother’s approval of her courage.

Dreams are another common device for rendering subjectivity. They became commonplace in the psychoanalytical films of the 1940s, and have been used ever since to probe the more or less unconscious impulses of our characters. We’re let in on characters’ dreams in A Quiet Passion, Hacksaw Ridge, and Kubo and the Two Strings.

Both visions and dreams become important motifs in The Birth of a Nation. Early in the film, the child Nat Turner, who has been called “a leader and a prophet” by an elder slave, dreams of himself in tribal paint running through a forest. Later, grown-up and developing a sense of himself as a rebel against oppression, he re-experiences the dream, only now the child encounters himself as an adult, who moves to protect him. The child becomes father to the man.

These plunges into subjectivity run along with images of Nat’s revelation: an angel he sees at moments of greatest torment, on the whipping block and on the gallows.

On the second occasion, the figure is more fully revealed as an angel, and she seems ready to embrace him. The nocturnal spirituality of the opening has been counterbalanced by something like Christianity, but it’s hardly the white folks’ version: Nat sees a dark angel.

Frames and breaking frames

Moana.

Subjectivity can also shape our sense of time, thanks to flashbacks. Very common nowadays is the brief flashback representing a sudden memory. In Allied, a shot of Max and Marianne on their rooftop bed-sit in Casablanca comes when Max is recalling their mission, after he’s learned she might be a German spy. A parallel device is the auditory flashback, as when a character recalls earlier lines of dialogue, which might not be accompanied by imagery from the past scene. Several of these films drop in sonic flashbacks, which serve as reminders to the audience as well as recollections for the characters.

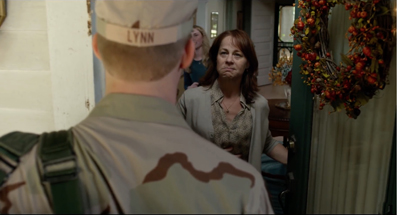

A subjective push into the past can take over the whole structure of the film. This happens when big stretches of the plot are presented through flashbacks to events that characters tell or remember. A fairly pure case is Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. It intercuts three time periods: the present, as Billy and his comrades in arms visit a Thanksgiving football game; Billy’s return to his family two days before the game; and the more distant events of Billy’s tour of duty in Iraq, culminating in the death of his beloved sergeant Shroom.

Throughout the film we’re largely restricted to what Billy experienced in both present and past.

In most films, though, flashbacks don’t represent memories. Often a flashback is initiated as a character’s recollection or testimony, but it presents events that a character didn’t know about. In these cases, the film has it both ways–subjective when it wants us to feel with the character, but wider-ranging when the extra information can yield suspense or another perspective on what the character knows. This happens in Jackie, in which Jacqueline Kennedy tells a journalist about the JFK assassination and its aftermath. We mostly adhere to what she could have seen and heard, but some incidents occur outside her ken. The interview situation motivates the return to the past, and that’s usually what we find in these partly subjective flashbacks.

The flashback technique was fairly common in Hollywood’s silent era but rarer in the 1930s. It emerged as a major creative option in the Forties; there are more flashbacks in 1944 feature releases than in all of the Thirties. Nowadays most films, even Moana, resort to it. (Maui’s boasting song “You’re Welcome” reviews his gifts to humanity.) Virtually every film I mention today employs at least one flashback–a testimony to the enduring power of this storytelling norm.

Since even the most personal flashbacks tend to stray from what characters could have witnessed, it’s not surprising that today we commonly have completely “objective” flashbacks. The plot simply jumps to and fro through time without the alibi of character memory. Hollywood has occasional early instances (Beau Geste, 1927; A Man to Remember, 1938; Confidence Girl, 1952; The Killers, 1955), but the “external” flashback is rare before the 1960s. Over the decades, filmmakers and audiences became comfortable with the flashback that simply admits itself as such. The time shift may be signaled by a title (“Two Days Earlier” in Billy Lynn), but some films find other ways to announce the flashback.

A simple example is Ben-Hur. Steered by a voice-over narrator (who will turn out to be a character in the film), the opening shows the start of a chariot race in a Roman Circus. Two young bravos swap lines that arouse curiosity: “You should have stayed away.” “You should’ve killed me.” “I will.” Then the race starts, the camera pans left to follow it, and the shot dissolves (a graphic match) to an image of two horsemen racing around a rock.

They are youthful versions of the competitors we’ve just met, and we’ll learn that Messala is Judah Ben-Hur’s adopted brother. The rest of the plot follows the friends’ careers that lead them to the fateful chariot competition. And that opening stretch is replayed when the flashback catches up with the frame situation. We’re reintroduced to the Circus, and identical shots show them exchanging the same lines we heard at the start.

This sort of overlapping return to the frame is common when the flashback consumes a large chunk of the film. One traditional schema, used in Ben-Hur, presents the frame story as a situation in crisis. This serves to grab our attention, to raise questions, and to hold the outcome of present-time events in suspension while the backstory clicks in.

The crisis structure is seen in Hacksaw Ridge, when after glimpses of a ferocious battle we see the protagonist rushed along on a stretcher. Thanks to a title, “Seven Years Earlier,” we shift to the past in another “objective” flashback. Eventually we’ll loop back to the wounding and rescue of Doss at Hacksaw Ridge.

The earlier versions of Ben-Hur didn’t resort to flashback construction. Similarly, Sergeant York (1941), which has similarities to Hacksaw Ridge, relies on straightforward chronology. The crisis schema became popular in the 1940s (e.g., The Big Clock, 1947), but it’s even more common now than it was then.

So is a willingness to put flashbacks inside flashbacks. Hacksaw Ridge‘s main flashback breaks its own chronology to show scenes of domestic violence in Doss’s youth. The main flashback of Ben-Hur plays host to embedded flashbacks too. The large-scale Chinese-box construction of 1940s films like The Locket (1946) and Passage to Marseille (1944) is still uncommon, but brief flashbacks wedged inside a long-term one pose no problems for current audiences.

Ben-Hur and Hacksaw Ridge set up the Now situation straightforwardly and at some length. At the opposite extreme is the present-time opening of Don’t Breathe: a slow swoop down to a barren street along which a man drags a young woman’s body. A second shot isn’t very informative about him or her, and the two shots consume only 63 seconds.

Probably most viewers forget about this cryptic but intriguing crisis situation until it’s repeated at the climax–the shots in reverse order, the woman more clearly visible, and the two shots clipped to a mere nine seconds. This is compact storytelling.

The Shallows sets up its Now through attachment to a minor character. A little boy finds a video camera on a helmet floating in the surf. He plays the footage and, seeing a shark attack recorded there, runs to get help.

Later the boy’s discovery is shown again, and now we’re in a position to appreciate its importance. But like the opening sequence of Mildred Pierce, this prologue has omitted key information: the boy’s replay of Nancy’s recorded plea for help. At the climax that footage, which we’ve seen her make, is is now re-run for us as the boy watches it. Again the boy is shown running for help. This overlap brings us up to the original Now.

At the start there was an enigmatic rack-focus to the buoy in the distance. In the replay, while the boy studies the video, we see Nancy bobbing there, waiting for the shark to attack.

This scene, incidentally, shows how a flashback structure can take the sting out of a convenient coincidence. If something unlikely–the boy discovering the camera in time to help the heroine–is shown before the main action, then it doesn’t seem as out-of-nowhere as it would if presented in straight chronology. After seeing the somewhat cryptic opening, we might even be looking forward to the revelation, as presumably some viewers are when a scene in the flashback introduces the surfer with the camera helmet.

Interestingly, neither Don’t Breathe nor The Shallows resorts to a title announcing the transition from Now to the past. Can it be that our genre pictures can live with a little less redundancy than our Oscar bait?

Strands, mosaics

Jackie.

Filmmakers never tire of tweaking flashback conventions. A more subdued variant of the crisis setup is used in Manchester by the Sea. Joe Chandler dies and his brother Lee, working as a maintenance man in Boston, is summoned back home to Manchester. These scenes alternate with episodes from the past, out of order, showing the brothers’ relationship and Joe’s eventual death. The crisis comes about fifty minutes into the plot, when in a lawyer’s office Lee learns that Joe wanted him to take custody of his son Patrick and move back to Manchester.

Lee’s resistance to this plan is explained in another string of flashbacks that show the disintegration of Lee’s marriage, the death of his children, and his attempted suicide. He has left the town behind and lives in self-inflicted pain and isolation.

At this point, the film reverts to chronology in the Now. The drama pivots around Lee forging a relationship with Patrick and coming to terms with his past. Only two brief flashbacks break up the story line, and those relate to Joe’s disappointment at Lee’s retreat from the world into a menial job. If the first half had been presented chronologically, we would have lost the sharp contrast between Lee’s scowling reluctance to reach out to Patrick and the more vigorous, emotionally open man he once was. Hollywood films may not excel at portraying gradual character change, but flashbacks allow a sharp sense of Before and After that can suggest how humans remake themselves in response to events.

The mosaic quality of the flashbacks dotting Manchester by the Sea can be seen to a lesser extent in Jackie. Here there are four principal strands of time to be interwoven, with glimpses of others. One strand involves the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath–the public ceremony of the display of his body and his burial in Arlington. Another involves Jackie’s consultation with a priest some time after JFK’s death, discussing her plans to bury their first two children, who died as babies, alongside him. A third strand, temporally pre-assassination, presents her famous 1962 tour of the White House. Finally there’s her post-assassination interview with a reporter who asks her questions about her role as First Lady and her handling of the horrific Dallas tragedy. We also get glimpses of the 1960 inauguration ball and Pablo Casals’ 1961 concert at the White House.

The film opens with the reporter calling on Jackie and the two settling down for their talk. He’s a bit provocative and probing, she’s guarded and self-censoring. The somewhat odd angle of the shot/reverse-shot framings, with her eyeline only a little off-center and sometimes straight at the camera, conveys an eerie ceremonial stiffness.

The reporter’s interview seems to be the frame for the flashbacks. Not only does their meeting occupy the normal position of a framing situation, but we’re aware that another schema triggering flashbacks is a testimony situation. In court, in a police station, at home quizzed by a reporter: These often set up a flashback narrative. The probing-reporter schema was crystallized in the 1940s with, of course, Citizen Kane (1941) but also with earlier films like The Escape (1939), Edison the Man (1940), and The Great Man’s Lady (1941).

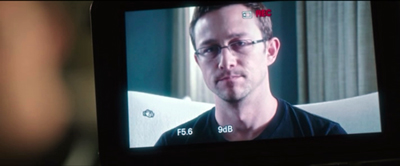

Snowden is a good contemporary example of the reporter-interview frame. Long blocks of flashbacks are enclosed within a ticking-clock situation in the present. Snowden retells his life, in chronological order, for Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald.

The film’s narration is largely tied to his range of knowledge during those periods, especially when suspense is at stake. We get plunges into subjectivity when he’s struck by epilepsy, and much optical POV cutting, notably when he downloads the NSA files as officials mill around outside his cubicle. As often happens in classical filmmaking, the narration widens its perspective to provide montages of news reports and reactions to Snowden’s revelations by his associates around the world.

Snowden tidily frames its past episodes by the present-time action before and after the big interview. The final scenes, and the credits, show the consequences of his whistle-blowing in the days and years afterward. But Jackie revises the testimony schema in an unusual way.

As the film goes on, it’s revealed that the reporter’s interview with Jackie isn’t the ultimate Now. The last events in the story chronology are Jackie’s consultation with the priest and the burial of her children. But from about 45 minutes onward, the priest’s attempts to console her are intercut with the interview. They are, in other words, flash-forwards.

They’re initially concealed as such because they follow Bobby Kennedy’s suggestion, in the assassination’s aftermath, that Jackie talk to a priest. That cue inclines us to assume that the priest’s advice is given during her final days in the White House. Only when the reporter phones his editor and says Jackie intends to bury the children beside Jack, and when Jackie tells the priest that the reporter’s story went around the world, are we aware of the burial scene’s place at the very end of story chronology.

This is a cogent example of schema revision: a frame that doesn’t enclose everything that, by convention, it should. One effect is to make the burial of the children an unexpected climax–a revelation of how much death this woman has seen, and a counterpoint to the glittering image of “Camelot” on which the film closes.

So where you put your flashbacks turns out to be crucial. Had the flashbacks to Lee’s tragic mistakes in Manchester come earlier, we’d probably be less sympathetic to him than we are; by the time of their arrival, we’ve seen his long-term suffering and are prepared to have a complex judgment of him. The timing of flashbacks also shows to good effect in Nocturnal Animals.

Most of Nocturnal Animals is dominated by another device for braking chronology: the embedded story. Here a plot involving new characters is wedged within the main story. Novels have done this for some time, as when a character discovers a manuscript that opens a story world containing a completely new cast. In the comic book Watchmen, the story Marooned is read by a minor character in the main plot.

In films of any period, such discrete embedded tales are rare. In the 1940s, the chief variant involves dream plots: the protagonist falls asleep and the dream consumes the bulk of the film, as a long flashback might. The main character might retain her identity, as Dorothy does in The Wizard of Oz (1939), or the dream character might be a new persona, as in Du Barry Was a Lady (1943), where Red Skelton becomes King Louis XV. Either way, an alien story world is opened up.

Nocturnal Animals contains an elaborate embedded story. Art-gallery owner Susan Morrow is in the dumps; her chi-chi friends are cold and her husband is having an affair. She receives the manuscript of a novel from her first husband Edward. Over some days Susan reads this harrowing pulp exercise set in west Texas, and it’s dramatized for us in chunks. interspersed with her daily routines.

At first we might think that the novelistic sections are “objective” presentations of the scenes, a parallel fictional world. But about 45 minutes into the film, we get a flashback to Susan meeting Edward at the start of their romance. (Actually, it’s a re-meeting; they had crushes on each other years before.) Thereafter flashbacks to their courtship and their marriage are interspersed with more stretches of the novel. Tony, the hapless, somewhat spineless protagonist of the novel, is played by Jake Gyllenhaal, who also plays Edward.

The flashbacks invite us to find a dose of subjectivity here. Is Susan reading the novel as a portrayal, deliberate or unwitting, of Edward’s feelings of inadequacy in their marriage? She cheated on Edward with the man who became her second husband, so she may also be projecting her own guilt onto the terrifying fate of Tony’s wife–interestingly, not played by Amy Adams, the actress portraying Susan.

In Nocturnal Animals, the frame is neater than in Jackie; at the film’s end we return to Susan’s present life. But an ambiguous ending asks us to consider how fully we have entered into her imagination.

There’s a more drastic revision of the flashback schema, or rather the audience’s presuppositions about it, in Arrival, which I’ve talked about here. But interesting flashbacks with a 40s flavor are also at work in James Schamus’s Indignation, analyzed here.

Strands or blocks?

I think these examples show that it can be useful to think about film narrative from the standpoint of craft. Since the filmmakers made choices, what rationale justifies them choosing what we have rather than what we might have had?

For example, it would have been perfectly possible to arrange the time-layers of Jackie or Manchester by the Sea as blocks, separate chapters (perhaps given titles or dates) rather than as interwoven strands. Similarly, Nocturnal Animals could have shown us Susan’s marriage to Edward as one block, then her life with her second husband, and then the embedded novel as one long stretch. Thinking about how these alternatives would alter our experience can give us insight into the benefits and costs of the choices the filmmakers went with.

Block construction became a somewhat popular storytelling option in the 1940s. Long flashbacks balanced against one another can create blocks, as in Citizen Kane and A Letter to Three Wives (1948). Similar were “chaptered” films like Holiday Inn (1942) and Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) and the episode-based films Fantasia (1942), Tales of Manhattan (1942), Flesh and Fantasy (1943), and others. Welles, always alert to trends, planned such a structure for It’s All True.

2016 has given us two pure examples of block construction, both of considerable interest. The most visible one is Moonlight, which tells its character-centered story in three phases of the life of Chiron: his boyhood, his teenaged years, and his early adulthood.

The sections are announced by titles: Little, Chiron, and Black. The first two stretch over several weeks and show Chiron bullied by other kids and neglected by his crack-addicted mother. He also encounters helpers, at first the easygoing drug dealer Juan and his girlfriend, and later his schoolmate Kevin, who in the second episode is forced by the other boys to beat Chiron. The final episode unfolds in a single night. Chiron, now called Black and grown to be a powerful man, has become a drug dealer and is filmed somewhat parallel to Juan.

Black visits a diner where Kevin works. Tentatively their affection and sexual yearning for one another are rekindled.

As with any creative choice, there are trade-offs. Moonlight‘s sharply-edged episodes refuse a smooth arc of action; they sample his life and deny us a clear “coming of age” process. There are gaps between the stories, and the one between the second and the third episodes is crucial. We’re left to imagine what happened to Chiron that turned him into the muscled, tough Black. Perhaps the fight that got him sent out of school–the moment when he fought back at the main bully–marks his turning point. Surely too his prison experiences shaped his transformation, but we neither see those nor hear him tell about them. Director-screenwriter Barry Jenkins has left us to note the vivid change in character without supplying what Henry James called the “weak specification” of all the events that shaped him. Block construction has left empty spaces for our imagination to fill.

Another fairly pure case of block construction is Paterson. (I discuss it briefly here.) The plot consists of a week’s worth of events, broken into days starting on Monday. We follow Paterson the bus driver on his daily rounds of going to work, doing his driving, coming home to his wife, walking their dog, and sometimes paying a night visit to a local tavern. Some incidents are variants of others, such as the morning conversations with Donny, Paterson’s supervisor, or the glimpses of different sets of twins around town.

The daily blocks are marked, at least initially, by a title stating the day of the week, but this pattern is varied: No titles for the weekend. Another marker is the opening shot of each segment showing Paterson and his wife in bed from straight above them.

This image varies too, with different compositions and shot scales each morning, and in one case, Paterson alone. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes explains that each day changes:

So there’s a routine. He’s going to leave and return to the house at the same time every day, so it’s going to look the same. I said to Jim [Jarmusch, the director], “It might be nice to have some gentle differences between them, to define one day from the next.” That became our task, finding ways of keeping things visually interesting without going too far.

Today block construction often calls forth the sort of stylistic tagging pointed out by Elmes. The same differentiation of visual textures is found in flashbacks. A funny example occurs in Sausage Party, when Firewater explains how the Non-Perishables created the myth of humans as kindly gods. The framing situation in the present is given in chiaroscuro imagery with thick volumes and plausible (for a cartoon) depth. The flashback to humans’ slaughter of the groceries is rendered in a screeching, retro/headcomix style and an abstract space.

This style is maintained for the fantasy version that Firewater and his cronies concocted to keep the groceries from panicking. Then we return to the narrating frame.

Not gentle differences here: glaring ones, suitable to comic exaggeration.

Something in-between operates in several of the films I’m considering. In Café Society, two cinematographic styles differentiate between the major locales, Hollywood and New York. Jackie‘s post-asssassination flashbacks are filmed in a free-camera style distinctly different from the locked-down, planimetric shots of the interview and the more studio-bound images of the TV filming of the White House Tour.

Likewise, Nocturnal Animals assigns three different “looks” to its three levels. DP Seamus McGarvey explains that Susan’s present had to be “colorless, [with a] low-contrast anemic aspect to it.” The story within the story is “colorful, more primaries.” The flashbacks to Susan’s and Edward’s marriage have a softer, glowing texture.

Visually tagging blocks, fantasies, and flashbacks wasn’t uncommon in the silent era, when filmmakers marked them with vignettes and soft focus. These optical devices, along with distorting lenses, were occasionally used in the sound era too, along with occasional shifts between color and black-and-white (The Wizard of Oz; Portrait of Jennie, 1949). On the whole, differentiating strands or blocks became a firm craft convention somewhat later, from the 1980s on. I talk about how that happened in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Ooh-La-La Land

Believe it or not, I haven’t exhausted the debts of 2016 movies to Hollywood in the Forties. There is, for instance, the device of voice-over, so common in that decade, which reappears in various guises, most notably that of the gossipy narrator of Café Society. There’s also the strategy of confining the bulk of the film’s action to a single location, which became notable in Angels over Broadway (1940), Lifeboat (1944), Rope (1948), and The Time of Your Life (1948). That method, common to low-budget thrillers, was ingeniously exercised in 10 Cloverfield Lane, The Shallows, and Don’t Breathe. In another entry I’ve discussed how Sully uses the device of replay that became common in the 1940s.

La La Land sums up several of the tendencies I’ve mentioned. It displays block construction, with sections labeled Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter… Five Years Later. The film’s first section uses the flashback technique too. After we follow Mia out of the traffic jam and to the party and the piano bar, the narration jumps back to the traffic jam and tracks Sebastian through his day up to the moment he pounds out jazz at the piano. This brings them together. As she’s about to compliment him on his playing, he brushes past her and leaves. At about 25 minutes in, this is the turning point ending the film’s first part.

The rest of the film traces their other coincidental meetings until they fall in love, try to maintain their relationship, and ultimately break up. They re-meet at Sebastian’s club, with Mia now married to a courteous side of beef. As the two look at each other and Sebastian takes over the piano to play their love theme, the film skips back to the first piano-bar encounter. Instead of passing Mia, though, Sebastian grabs her and they kiss.

Now the narration posits an alternative story line in which they marry, become parents, and still have success. This what-if scenario is rendered in stylized settings, accompanied by moments of dance.

Like the visual tagging of blocks and flashbacks, this sequence needs to abstract its settings, theatricalizing them so they’re set off from the real-world locales in which our characters have also been singing and dancing.

La La Land revisits a schema that was explored a little in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood: the alternative-universe story line created by forking paths. I’ve talked about the clearest early example, the 1934 film adaptation of the play Dangerous Corner. It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) did it negatively: Imagine a universe without you (or George Bailey). A little-known instance from that period is Repeat Performance (1947), which offers its actress-heroine a narrative reset like that to come in Groundhog Day (1993), Run Lola Run (1998), Source Code (2011, talked about here), Edge of Tomorrow (2014), and many other media texts, including comics.

Again,the schema is creatively reworked. The past the couple might have had is played out with parallels to the real-world life that Mia found. The result is an epilogue balancing the traffic-jam prologue–these people, unlike the gridlocked drivers, have found their success in Show Biz–but at the cost of love. By showing us what might have been, the final sequence provides something both wistful and satisfying.

I regret missing certain films this year, particularly Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, which seems to constitute an intriguing instance of block construction merged with a minimal network narrative. I look forward to catching up with it. And I’ve confined myself to Hollywood and off-Hollywood films, but I could easily have stretched the boundaries to include Elle (flashbacks), I Am Not Madame Bovary (block construction), Sieranevada (confined-space shooting, discussed by Kristin), Julieta (flashbacks, voice-over, etc.. etc., discussed in another entry), and many other imported films. These narrative strategies now belong to contemporary movie storytelling as a whole.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Thinking along these lines has made my 2016 moviegoing all the more fun. And a happy 2017 to you too.

E. H. Gombrich explains the concept of the schema throughout Art and Illusion, particularly in Chapter V and on pp. 313-314.

My quotation from Damien Chazelle comes from Mark Dillon, “City of Stars,” American Cinematographer 98, 1 (January 2017), 57. The same issue’s story “Quotidian Vision,” by Iain Marks, includes the remark from Frederick Elmes (p. 22). Seamus Garvey’s comments on the visual styles of Nocturnal Animals comes from Carolyn Giardina, “Beginning First in the Darkness, Then Moving toward the Light,” Hollywood Reporter, Awards no. 1 (December 2016), 48; apparently not available online. In the same article Vittorio Storaro talks about differentiating New York and Hollywood pictorially in Café Society.

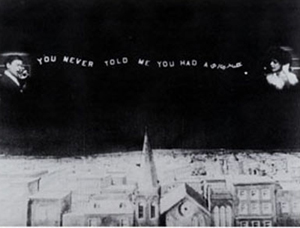

The cellphone conversation in The Shallows is an interesting turn back to a much older schema for representing phone conversations, using split screen. The first one below is is from College Chums (1907). We’ve seen similar phone-call diagrams since then in Pillow Talk (1959), Bye Bye Birdie (1963), and Down with Love (2003, also below). Everything comes back eventually.

Other discussions of stylistic schemas hereabouts are in entries on lipdubs, shot/reverse-shot cutting, and Wes Anderson’s narrative worlds.

There’s another flashforward in these films: La La Land embeds a montage of the couple’s creative work in their “City of Stars” duet at the piano. Another, smallish block, it anticipates the looped construction of the final fantasy epilogue.

Snowden: Yet another revision of the shot-reverse shot schema, adapted for what John Dean called “telephonic communication.”

Friendly books, books by friends

Moses and Aaron (1974).

DB here:

When the stack of books by friends threatens to topple off my filing cabinet, I know it’s time to flag them for you. I can’t claim to have read every word in them, but (a) we know the authors are trustworthy and scintillating; (b) what I’ve read, I like; (c) the subjects hold immense interest. Then there’s (d): Many are suitable seasonal gifts for the cinephiles in your life (which can include you).

Happy birthday, SMPTE

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

It includes survey articles on the history of film formats, cameras and lenses, recording and storage, workflows, displays, archiving, multichannel sound, and television and video. There’s even an overview of closed-captioning. The issue costs $125 for non-SMPTE members, and it’s worth it. Many libraries subscribe to the journal as well.

A highlight is John Belton’s magisterial “The Last 100 Years of Motion Imaging,” which includes twenty-two pages of dense timelines of innovations in film, TV, and video. They stretch back beyond 1916, to 1904 and the transmission of images by telegraph. John’s article is provocative, suggesting that we might think of digital cinema as returning to film’s origins in handmade images for optical toys.

Lucas predicted that digital postproduction brought film closer to painting, and for more and more filmmakers that prediction is coming true. I was startled to learn that 80% of Gone Girl was digitally enhanced after shooting.

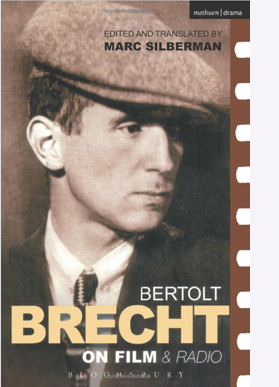

Yes, sir, that’s our BB

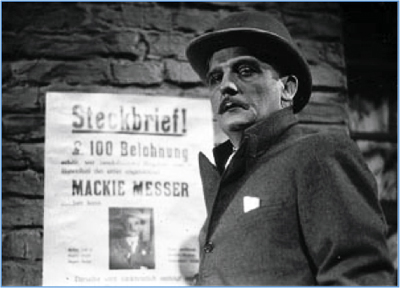

Die 3 Groschen-Oper (1931, G. W. Pabst).

During the 1970s, Bertolt Brecht’s name was everywhere in film studies. He epitomized what an alternative, oppositional, or subversive cinema ought to be. Cinema, even more powerfully than theatre, was a machine for producing illusions. So in his name critics objected to happy endings, plots that tidied up reality, characters with whom we ought to identify, messages that masked the real nature of bourgeois society. Films made all these things seem part of the natural order of things.

The Brechtian antidote was, as people used to say, to “remind people they were watching a film.” This was done by rejecting what he called the Aristotelian model and replacing it with the “alienation effect”: a panoply of distancing devices like intertitles, characters addressing the camera, actors confessing they were actors, and a display of the means of cinematic production (including shots of the camera shooting the scene).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

Brecht became part of Theory. In French literary and theatrical culture of the 1950s, his ideas on staging and performance had claimed the attention of Roland Barthes and other Parisian intellectuals. Godard was alert to the trend early, it seems; he had fun in Contempt (Le mépris, 1963) citing the two BB’s (the other was Brigitte Bardot, bébé), and letting Lang quote a poem by his old collaborator and antagonist. By the time Anglo-American film theorists were ready for semiotics, Brecht was offering support. Didn’t his anti-illusionism chime well with the belief that all sign systems were arbitrary and culturally relative?

My summary is too simple, but then so were many borrowings. Soon enough any highly artificial cinematic presentation might be called “Brechtian,” though usually minus the politics. In the academic realm, Murray Smith’s book Engaging Characters (1995) pointed out crucial weaknesses in the anti-illusionist, anti-empathy account. By then, the certified techniques were becoming part of mainstream cinema. Thereafter, we had Tarantino’s section titles and plenty of movies breaking the fourth wall. Brecht might have enjoyed the irony of using the to-camera confessions of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) bent to support cynical swindling. Isn’t The Big Short (2015) a sort of Hollywoodized lehrstück (“learning play”)?

Brecht’s writings should be read and studied by every humanist and certainly everybody interested in film. They’re clear, blunt, and often sarcastic.

This beloved “human interest” of theirs, this How (usually dignified by the word “eternal,” like some indelible dye) applied to the Othellos (my wife belongs to me!), the Hamlets (better sleep on it!), the Macbeths (I’m destined for higher things!), etc.

Now Marc Silberman, our colleague here at Madison, has completed a trio of books that make the master’s work available. Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio includes essays, scripts, and the Threepenny Opera lawsuit brief. There’s also Brecht on Performance and a complete revision of that trusty black-and-yellow volume dear to many grad students: Brecht on Theatre. The latter two collections Marc worked on with collaborators. All are indispensible to a cinephile’s education. As Brecht imagined a bold political version of music he called misuc; can we imagine a cenima?

From BB to S/H

Speaking of Straub and Huillet, every decade or so somebody comes out with a book about them. This time we have to thank the admirable Ted Fendt, in the twenty-sixth volume in the series sponsored by the Austrian Film Museum (as well as the Goethe Institute and Synema). Like the Hou Hsiao-hsien volume (reviewed here), Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet is fat and full of ideas and information.

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

Starting things off is a lively and comprehensive survey of the duo’s careers by Claudia Pummer, with welcome emphasis on production circumstances and directorial strategies. The book wraps with a detailed thirty-page filmography and a substantial bibliography.

My thoughts about S/H are tied up with their earliest work, when I first learned of them. So I loved, and still love, Not Reconciled (1965) and The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. I also have a fondness for Moses and Aaron, Class Relations (1983), From Today until Tomorrow (1996), and Sicilia! (1998). I find others out of my reach, and several others I haven’t yet seen. People I respect find all their work stimulating, so I suspect it’s really a matter of gaps in my taste.

Whether you like them or not, they’re of tremendous historical importance. Without them, Jim Jarmusch and Béla Tarr, and of course Pedro Costa and Lav Diaz, would not have accomplished what they have. And especially in December 2016, we ought to find their unyielding ferocity inspiring. Remember them on Dreyer: “Any society that would not let him make his Jesus film is not worth a frog’s fart.” Brecht would have approved.

Stone’d

To the minimalism of Straub and Huillet we can counterpoint the maximalism of Oliver Stone, the most aggressive tabloid American director since Samuel Fuller (although Rococo-period Tony Scott gives him some competition). After two books on Wes Anderson, Matt Zoller Seitz has brought us a booklike slab as impossible as the man’s films. Can you pick it up? Just barely. Can you read it? Well, probably not on your lap; better have a table nearby. Does its design mirror the maniacal scattershot energy of films like JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), and U-Turn (1997)? Watch the title propel itself off the cover.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The whole thing comes at you in a headlong rush. Amid the pictorial churn and several essays by other deft hands, we plunge into and out of that stellar interview, mixing biography and filmmaking nuts-and-bolts. Matt gets deep into technical matters, such as Stone’s penchant for rough-hewn editing, as well as raising some big ideas about myth and autobiography. There are occasional quarrels between interviewer and interviewee. Out of the blue we get remarks like “Alexander was not only bisexual, he was trisexual,” which was not redacted.

The book’s very excess helps make the case for Stone’s idiosyncratic vision. Matt’s connecting essays, along with the vast visual archive he’s scavenged and mashed up, made me want to rethink my attitude toward this overweening, sometimes crass, sometimes inspired filmmaker. He now seems a quintessential 80s-90s figure, as much a part of the era as Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Stone emerges as a resourceful defender of The Oliver Stone Experience, articulating a radical political critique with gonzo verve.

Rhapsody in white

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

This period piece is in its own way as wild as an Oliver Stone movie. From its opening cartoon of Paul himself as a Great White Hunter bagging a lion, it’s a virtually self-parodying account of how a black musical tradition got netted, trussed up, and caged for the swaying delectation of white audiences. (No need to mention the irony of the name of our King.)

Along the way we have some straight-up songs (including some by Bing Crosby) spread among extravagant dance numbers. The Universal crane gets a workout as well. The music is infectious, the performers sweating to please, and the restoration–coming, I hope, to your screen soon–finally shows what two-color Technicolor could do. This is the definitive version of a film too often known in cut versions with shabby visuals and sound.

The book is an in-depth contextualization of the film, the studio, and the tradition of musical revues, both on stage and in film. It records the production and reception, with rich documentation throughout. The story of assembling the restoration is there too, and it’s a saga in itself. David is one of the moving spirits behind the online Media History Digital Library and its gateway Lantern. James is Manager of the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center at the Museum of Modern Art. Their collaboration has given us both a lush picture book and a serious, always enjoyable piece of scholarship. Their book proves the value of crowdsourcing: funded by online subscription, it was self-published. In this and much else, it can be a model for film historians pursuing questions that commercial and university presses might find too specialized. The result is a model of ambitious research, writing, and publishing.

Visiting Radio Ranch

Gene Autry in The Phantom Empire (1935).

For about thirty years I’ve been arguing that one fruitful research program in film studies involves what I call a poetics of cinema: the study of how, under particular historical conditions, films are made to achieve certain effects. This program coaxes the researcher to analyze form and style, study changing norms of production and reception, and consider how filmmakers work in their institutions and creative communities, with special focus on craft routines, work methods, and tacit theories about the ways to make a movie.

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

Scott traces production practices and conventions, focusing in particular on two dimensions. First, to a surprising degree, serials rely on the conventions of classic stage melodrama, such as coincidence and more or less gratuitous spectacle. Second, the serials are playful, even knowing. Like video games, they invite viewers to imagine preposterous narrative possibilities, not only in the imagination but also on the playground, where kids could mimic what they saw Flash Gordon or Gene Autry do.

Matinee Melodrama investigates the implications of these dimensions for narrative architecture, visual style, and the film and television of our day. Scott closes with analysis of the James Bond series, the self-conscious mimicking of serial conventions in the Indiana Jones blockbusters, and the Bourne saga, and he shows how they amp up the older conventions. “Like the contemporary action film generally, the Bourne movies participate in a cinematic practice vigorously constituted by studio-era serials. That is, they blend melodrama with forceful articulations of physical procedure in scenes of pursuit, entrapment and confrontation.”

Poetics, frank or stealthy

The Red Detachment of Women (1971).

Scott’s book acknowledges the poetics research program, and so, even more explicitly, does a new collection edited by Gary Bettinson and James Udden. The Poetics of Chinese Cinema gathers several essays that usefully test and stretch that frame of reference.

One standard challenge to the poetics approach is: How do you handle social, cultural, and political factors that impinge on film? I think the best way to answer this is to treat these factors as causal influences on a film’s production and reception. More specifically, in the production process, what we now call memes function as materials—subjects, themes, stereotypes, and common ideas circulating in the culture or the filmmaking institution. In the reception process, they provide conceptual structures that viewers can use in making their own sense of the films that they’re given. And such materials will necessarily include other art forms; films are constantly adapting and borrowing from literature, drama, and other media.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Tradition is a key concept in poetics, and the editors explore important ones in their own contributions. Gary Bettinson studies the emergence of Hong Kong puzzle films in works like Mad Detective (2007) and Wu Xia (2011). Are they simple imitation of Hollywood, or are they doing something different? Gary shows them to have complicated ties to local traditions of storytelling. Jim Udden focuses more on stylistics in his account of Fei Mu’s 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town, remade by Tian Zhuangzhuang in 2002. By examining staging, cutting, and voice-over, Jim shows that the earlier film is in many ways more “modern” than it’s usually thought and is somewhat more experimental than the remake.

It might seem that the “model” operas and plays of the Cultural Revolution, epitomized in The Red Detachment of Women (1971) would resist an aesthetic analysis; they’re determined, top-down fashion, by strict canons of political messaging. But Chris Berry’s contribution shows that they’re amenable to close analysis too. Like Soviet Socialist Realism, they may be programmatic in meaning, but not in every choice about framing, performance, cutting, and music. Indeed, the fact that people both inside and outside China (me included) still find them pleasurable probably owes something to their “Red Poetics.” And in true Hong Kong fashion, many filmmakers in that territory plundered those soundtracks with shameless, drop-the-needle panache.

I should probably add that I have an essay in this collection too. It’s called “Five Lessons from Stealth Poetics,” and it surveys things I’ve learned from studying cinema of the “three Chinas”: Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. What attracted me were the films themselves, but in exploring them I was obliged to nuance and stretch the poetics approach. Readers of this blog know the trick: in talking about particular movies, I also try to show the virtues of the approach I favor. In other words, stealth poetics.

This is a good moment to pay tribute to Alexander Horwath, moving into his final nine or so months of directing the Austrian Film Museum. He has been a major figure in European film culture, through his inspired programming and leadership in publishing the books and DVDs issued by the Museum. We’re very grateful for all he has done for us and for film historians around the world.

P.S. 11 December 2016: Thanks to Mike Grost for a title correction and John Belton for a name correction!

King of Jazz (1930).

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”