Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket

DB here, again:

We got a keen response to my entry on widescreen composition in Mad Max: Fury Road. Thanks! So it seemed worthwhile to look at composition in the older format of 4:3, good old 1.33:1–or rather, in sound cinema, 1.37: 1.

The problem for filmmakers in CinemaScope and other very wide processes is handling human bodies in conversations and other encounters (such as stomping somebody’s butt in an an action scene). You can more or less center the figures, and have all that extra space wasted. Or you can find ways to spread them out across the frame, which can lead to problems of guiding the viewer’s eye to the main points. If humans were lizards or Chevy Impalas, our bodies would fit the frame nicely, but as mostly vertical creatures, we aren’t well suited for the wide format. I suppose that’s why a lot of painted and photographed portraits are vertical.

By contrast, the squarer 4:3 frame is pretty well-suited to the human body. Since feet and legs aren’t usually as expressive as the upper part of the body, you can exclude the lower reaches and fit the rest of the torso snugly into the rectangle. That way you can get a lot of mileage out of faces, hands and arms. The classic filmmakers, I think, found ingenious ways to quietly and gracefully fill the frame while letting the actors act with body parts.

Since I’m watching (and rewatching) a fair number of Forties films these days, I’ll draw most of my examples from them. after a brief glance backward. I hope to suggest some creative choices that filmmakers might consider today, even though nearly everybody works in ratios wider than 4:3. I’ll also remind us that although the central area of the frame remains crucial, shifts away from it and back to it can yield a powerful pictorial dynamism.

Movies on the margins

Early years of silent cinema often featured bright, edge-to-edge imagery, and occasionally filmmakers put important story elements on the sides or in the corners. Louis Feuillade wasn’t hesitant about yanking our attention to an upper corner when a bell summons Moche in Fantômas (1913). A famous scene in Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) shows Griffith trying something trickier. He divides our attention by having the Snapper Kid’s puff of cigarette smoke burst into the frame just as the rival gangster is doping the Little Lady’s drink. She doesn’t notice either event, as she’s distracted by the picture the thug has shown her, but there’s a chance we miss the doping because of the abrupt entry of the smoke.

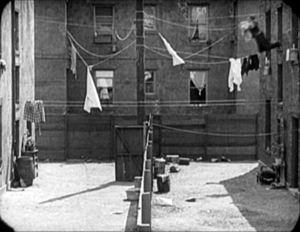

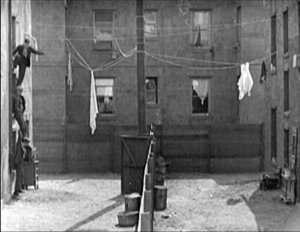

In Keaton’s maniacally geometrical Neighbors (1920), the backyard scenes make bold (and hilarious) use of the upper zones. Buster and the woman he loves try to communicate three floors up. Early on we see him leaning on the fence pining for her, while she stands on the balcony in the upper right. Later, he’ll escape from her house on a clothesline stretched across the yard. At the climax, he stacks up two friends to carry him up to her window.

Thankfully, the Keaton set from Masters of Cinema preserves some of the full original frames, complete with the curved corners seen up top. It’s also important to appreciate that in those days there was no reflex viewing, and so the DP couldn’t see exactly what the lens was getting. Framing these complex compositions required delicate judgment and plenty of experience.

Later filmmakers mostly stayed away from corners and edges. You couldn’t be sure that things put there would register on different image platforms. When films were destined chiefly for theatres, you couldn’t be absolutely sure that local screens would be masked correctly. Many projectors had a hot spot as well, rendering off-center items less bright. And any film transferred to 16mm (a strong market from the 1920s on) might be cropped somewhat. Accordingly, one trend in 1920s and 1930s cinematography was to darken the sides and edges a bit, acknowledging that the brighter central zone was more worth concentrating on.

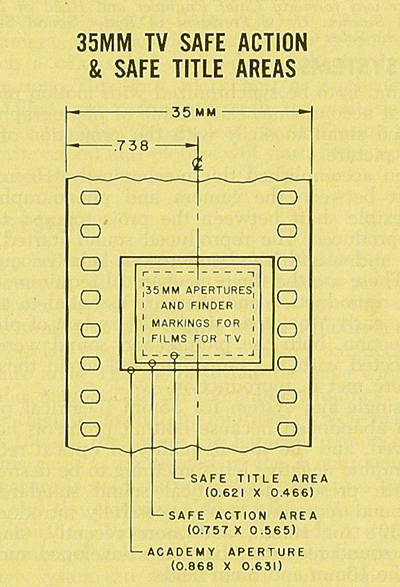

That tactic came in handy with the emergence of television, which established a “safe area” within the film frame for video transmission. TV cropped films quite considerably; cinematographers were advised in 1950 that

All main action should be held within about two-thirds of the picture. This prevents cut-off and tube edge distortion in television home receivers.

Older readers will remember how small and bulging those early CRT screens were.

By 1960, when it was evident that most films would eventually appear on TV, DP’s and engineers established the “safe areas” for both titles and story action. (See diagram surmounting this section.) Within the camera’s aperture area, which wouldn’t be fully shown on screen, the safe action area determined what would be seen in 35mm projection. “All significant action should take place within this portion of the frame,” says the American Cinematographer Manual.

Studio contracts required that TV screenings had to retain all credit titles, without chopping off anything. This is why credit sequences of widescreen films appear in widescreen even in cropped prints. So the safe title area was marked as what would be seen on a standard home TV monitor. If you do the math, the safe title area is indeed 67.7 % of the safe action area.

These framing constraints, etched on camera viewfinders, would certainly inhibit filmmakers from framing on the edges or the corners of the film shot. And when we see video versions of films from the 1.37 era (and frames like mine coming up) we have to recall that there was a bit more all around the edges than we have now.

All-over framing, and acting

Yet before TV, filmmakers in the 40s did exploit off-center zones in various ways. Often the tactic involved actors’ hands–crucial performance tools that become compositional factors. In His Girl Friday (1940), Walter Burns commands his frame centrally, yet when he makes his imperious gesture (“Get out!”) Hawks and DP Joseph Walker (genius) have left just enough room for the left arm to strike a new diagonal.

The framing of a long take in The Walls of Jericho (1948) lets Kirk Douglas steal a scene from Linda Darnell. As she pumps him for information, his hand sneaks out of frame to snatch bits of food from the buffet.

As the camera backs up, John Stahl and Arthur Miller (another genius) give us a chance to watch Kirk’s fingers hovering over the buffet. When Linda stops him with a frown, he shrugs, so to speak, with his hands. (A nice little piece of hand jive.)

The urge to work off-center is still more evident in films that exploit vigorous depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Dynamic depth was a hallmark of 1940s American studio cinematography. If you’re going to have a strong foreground, you will probably put that element off to one side and balance it with something further back. This tendency is likely to empty out the geometrical center of the shot, especially if only two characters are involved. In addition, 1940s depth techniques often relied on high or low angles, and these framings are likely to make corner areas more significant. Here are examples from My Foolish Heart (1950): a big-head foreground typical of the period, and a slightly high angle that yields a diagonal composition.

Things can get pretty baroque. For Another Part of the Forest (1948), a prequel to The Little Foxes (1941), Michael Gordon carried Wyler’s depth style somewhat further. The Hubbard mansion has a huge terrace and a big parlor. Using the very top and very bottom of the frame, a sort of Advent-calendar framing allows Gordon to chart Ben’s hostile takeover of the household, replacing the patriarch Marcus at the climax. The fearsome Regina appears in the upper right window of the first frame, the lower doorway of the second.

In group scenes, several Forties directors like to crowd in faces, arms, and hands, all spread out in depth. I’ve analyzed this tendency in Panic in the Streets (1950), but we see it in Another Part of the Forest too. Again, character movement can reveal peripheral elements of the drama.

At the dinner, Birdie innocently thanks Ben for trying to help her family with their money problems and bolts from the room, going out behind Ben’s back. The reframing brings in at the left margin a minor character, a musician hired to entertain for the evening. But in a later phase of the scene he will–still in the distance–protest Marcus’s cruelty, so this shot primes him for his future role.

At one high point, the center area is emptied out boldly and the corners get a real workout. On the staircase, the callow son Oscar begs Marcus for money to enable him to run off with his girlfriend. (As in Little Foxes, the family staircase is very important–as it is in Lillian Hellman’s original plays.) Ben watches warily from the bottom frame edge. Nobody occupies the geomentrical center.

Later, on the same staircase, Ben steps up to confront his father while Regina approaches. It’s an odd confrontation, though, because Ben is perched in the left corner, mostly turned from us and handily edge-lit. Marcus turns, jammed into the upper right. Goaded by Ben’s taunts, he slaps Ben hard. Here’s the brief extract.

The key action takes place on the fringes of the frame, while the lower center is saved for Regina’s reaction–for once, a more or less normal human one. Even allowing for the cropping induced by the video safe-title area, this is pretty intense staging.

The corners can be activated in less flagrant ways. Take this scene from My Foolish Heart. Eloise has learned that her lover has been killed in air maneuvers. Pregnant but unmarried, she goes to a dance, where an old flame, Lew asks her to go on a drive. They park by the ocean, and she succumbs to him. Here’s the sequence as directed by Mark Robson and shot by Lee Garmes (another genius).

In the fairly conventional shot/ reverse-shot, the lower left corner is primed by Eloise’s looking down at the water and Lew’s hand stealing around her.

Later, when Lew pulls her close, (a) we can’t see her; (b) his expression doesn’t change and is only partly visible; so that (c) his emotion is registered by the passionate twist of his grip on her shoulder. Lew’s hand comes out from the corner pocket.

Perhaps Eloise is recalling another piece of hand jive, this time from her lost love.

For many directors, then, every zone of the screen could be used, thanks to the good old 4:3 ratio. It’s body-friendly, human-sized, and can be packed with action, big or small.

Mabuse directs

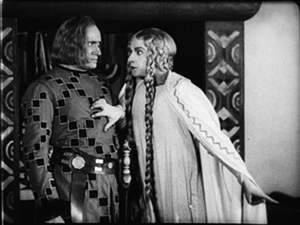

In other entries (here and here) I’ve mentioned one of the supreme masters of off-center framing, Fritz Lang. Superimpose these two frames and watch Kriemhilde point to the atomic apple in Cloak and Dagger (1946).

From the very start of Ministry of Fear (1944), the visual field comes alive with pouches, crannies, and bolt-holes. The first image of the film is a clock, but when the credits end the camera pulls back and tucks it into the corner as the asylum superintendant enters. (The shot is at the end of today’s entry.) Here and elsewhere, Lang uses slight high angles to create diagonals and corner-based compositions.

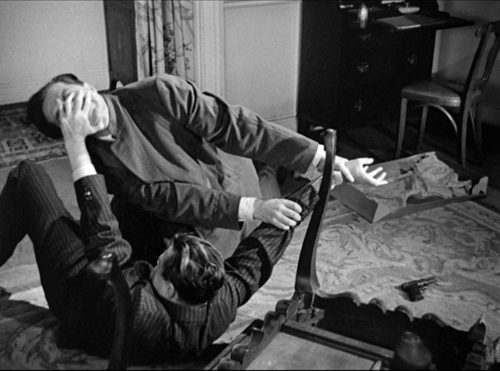

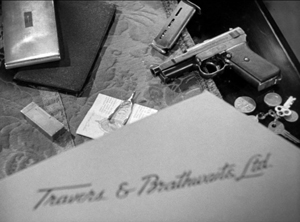

In the course of the film, pistols circulate. Neale lifts one from Mrs. Bellane (strongly primed, upper left), keeps her from appropriating it (lower center), and secures it nuzzling his left knee (lower right).

Later, Neale’s POV primes the placement of a pistol on the desktop (naturally, off-center), so that we’re trained to spot it in a more distant shot, perilously close to the hand of the treacherous Willi.

Amid so many through-composed frames, an abrupt reframing calls us to attention. Unlike Hawks and Walker’s handling of Walter in His Girl Friday, Lang and his DP Henry Sharp (great name for a DP, like Theodore Sparkuhl and Frank Planer) gives things a sharp snap when Willi raises his hand.

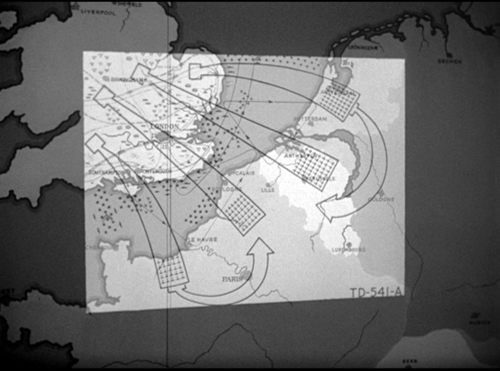

Lang drew all his images in advance himself, not trusting the task to a storyboarder. Avoiding the flashy deep-focus of Wyler and company, he created a sober pictorial flow that can calmly swirl information into any area of the frame. It’s hard not to see the stolen attack maps, surmounting today’s entry, as laying bare Lang’s centripetal vectors of movement. No wonder in the second frame up top, as Willi and Neale struggle in a wrenching diagonal mimicking the map’s arrows, that damn pistol strays off on its own.

Sometimes film technology improves over time. For instance, digital cinema today is better in many respects than it was in 1999. But not all changes are for the better. The arrival of widescreen cinema was also a loss. Changing the proportions of the frame blocked some of the creative options that had been explored in the 4:3 format. Occasionally, those options could be modified for CinemaScope and other wide-image formats; I trace some examples in this video lecture. But the open-sided framings in most widescreen films today suggest that most filmmakers haven’t explored the wide format to the degree that classical directors did with the squarish one.

More generally, it’s worth remembering that the film frame is a basic tool, creating not only a window on a three-dimensional scene but also a two-dimensional surface that requires composition–either standardized or more novel. Instead of being a dead-on target, the center can be an axis around which pictorial forces push and pull, drift away and bounce around. After all, we’re talking about moving pictures.

Thanks to Paul Rayton, movie tech guru, for information on 16mm cropping.

My image of the safe areas and the second quotation about them is taken from American Cinematographer Manual 1st ed., ed. Joseph C. Mascelli (Hollywood: ASC, 1960), 329-331. The older quotation about cropping for television comes from American Cinematographer Handbook and Reference Guide 7th ed., ed. Jackson J. Rose (Hollywood: ASC, 1950), 210.

I hope you noticed that I admirably refrained from quoting Lang, who famously said that CinemaScope was good only for…well, you can finish it. Of course he says it in Godard’s Contempt (1963), but he told Peter Bogdanovich that he agreed.

[In ‘Scope] it was very hard to show somebody standing at a table, because either you couldn’t show the table or the person had to be back too far. And you had empty spaces on both sides which you had to fill with something. When you have two people you can fill it up with walking around, taking something someplace, so on. But when you have only one person, there’s a big head and right and left you have nothing (Who the Devil Made It (Knopf, 1997), 224).

For more on the stylistics and technology of depth in 1940s American film, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), which Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, Chapter 27, and my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), Chapter 6. Many blog entries on this site are relevant to today’s post; search “deep-focus cinematography” and “depth staging.” If you want just one for a quick summary, try “Problems, problems: Wyler’s workarounds.” Some of the issues discussed here, about densely packing the frame, are considered more generally in “You are my density,” which includes an analysis of a scene in Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

Ministry of Fear (1944).

Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations

The Hateful Eight (2015).

DB here: Jeff Smith, our collaborator on the new edition of Film Art, is an expert on film sound. He has written earlier entries on Atmos and Trumbo.

The Academy Awards ceremony is upon us. Once again this year, I offer an overview of the two music categories: Best Original Song and Best Original Score. For the songs and some score cues I’ve provided links, so you can listen as you read.

This year’s nominees showcase music written in an array of musical styles for a wide range of narrative contexts. The composers and songwriters recognized for their work include some newcomers, some savvy veterans, and a pair of legends who have helped to define the modern film score.

As always, this preview is offered for non-sporting purposes. Anyone seeking insights for wagers or even the office Oscar pool is duly cautioned that they assume their own financial risks for any information they use. And since I was only half-right with last year’s prognostications, you might seek predictions from insiders at Variety and Entertainment Weekly.

Diversity in numbers: Best Original Song

Fifty Shades of Grey (2015).

When the Oscars were announced a few weeks ago, they made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Noting the lack of racial diversity among the acting nominees, social media exploded, creating #OscarsSoWhite as a popular Twitter handle to draw attention to the situation. After a cacophony of tweets and retweets, several celebrities weighed in. Will Smith and others suggested that they planned to boycott the ceremonies.

The nominees for Best Original Song, though, are a pretty significant exception to the OscarsSoWhite meme. Both the performers of these five songs and the topics they address reveal that Oscar voters haven’t entirely ignored the fact that films can be a force for social change.

The Weeknd’s breakout year on the pop charts has continued with an Oscar nomination for “Earned It” from Universal’s hit of last spring, Fifty Shades of Grey. The Weeknd’s “Can’t Feel My Face” has enlivened playlists all year long, but “Earned It” is a slow-burn soul ballad that accompanies Christian and Anastasia’s ride home after his mother interrupts their morning tryst. The song was co-written by the Weeknd, Belly, Jason “Daheala” Quenneville, and Stephan Moccio, and features a simple two-chord pattern on the piano that eventually builds toward a more harmonically adventurous string passage. According to Moccio, the song was intended to reflect a male perspective, hinting at the darkness lurking underneath Christian’s sexual peccadillos.

The Weeknd, Quenneville, and Belly are all Canadian. But considering that the Weeknd and Quenneville are of African descent and that Belly is of Palestinian heritage, their nomination offers a modest riposte to the criticism leveled at the Oscars for their lack of racial diversity. However, since their song appears in one of the more critically reviled films to receive a nomination, it seems unlikely that “Earned It” will take home the prize next Sunday.

Tuning up nonfiction films: Nominated songs from docs

Racing Extinction (2015).

Two other nominations come from recent documentary films, continuing a trend begun with last year’s nod to Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me. The first is for J. Ralph and Antony Hegarty’s “Manta Ray” from Racing Extinction, which examines the threat man poses to the survival of several bird species, amphibians, and marine animals.

Hegarty is only the second openly transgender person to receive a nomination, a quite pleasant surprise for fans of her work as a singer and songwriter. Hegarty initially made a splash in 2000 with the release of her band’s debut album, Antony and the Johnsons. Her breakthrough, though, came with the 2005 release I Am a Bird Now, which topped several critics’ year-end lists and won Britain’s prestigious Mercury Prize.

“Manta Ray” is a delicate waltz based upon a central theme from J. Ralph’s score for Racing Extinction. Although the song itself appears only over the closing credits, Ralph’s theme threads through the film, introduced during a key scene when a member of the filmmaking team removes a hook and fishing line from a manta ray’s dorsal fin. After the SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, commercial fishermen increasingly targeted manta rays since their gills were thought to have curative powers among practitioners of Chinese folk medicine.

Anchored by her soft, tremulous voice, Hegarty’s music has always exuded sensitivity and melancholy in almost equal measure. With Hegarty’s ethereal tones floating over Ralph’s simple piano accompaniment, “Manta Ray” not only captures the animal’s grace and beauty, but also hints at the tragedy of their steady decline.

Racing Extinction is not Hegarty’s first brush with Hollywood. Previously, her music was featured in James McTeigue’s V for Vendetta and in Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There. But given all the media attention to the Oscars, Sunday night will offer Hegarty a much bigger stage and a chance for the world to see her extraordinary gifts.

The other nominated song from a documentary is “Til It Happens to You,” which was written for Kirby Dick’s searing documentary on campus rape, The Hunting Ground. The film not only exposes college administrators’ efforts to cover up incidents of sexual assault, but also shows how two University of North Carolina rape survivors used Title IX legislation to draw attention to the problem.

“Til It Happens to You” brought Lady Gaga her first nomination and Diane Warren her eighth. Beyond the sheer star power brought by the pair, Gaga and Warren both have discussed their own experience as rape victims.

According to Variety, Gaga worried that the gravity of the film’s subject matter might not square with her outlandish diva persona: “I was very concerned that people would not take me seriously or that I would somehow add a stigma to it.” But her concerns appear to be unfounded. Warren reports that other survivors have reached out to her saying that the song and film is “making people feel less alone.”

Some of this reaction undoubtedly derives from the emotional gut punch delivered by the song’s lyrics. They not only describe the feelings of devastation felt by rape victims. They also express the difficulty of dealing with unfeeling bureaucrats and callous peers. The refrain of “Til It Happens to You” conveys the sense of isolation created by others’ inability to fully know what it’s like to walk in the victim’s shoes.

Licensed to Trill: The Spectre of Youth

Spectre (2015).

Jimmy Napes and Sam Smith’s “Writing’s On the Wall” from Spectre adds another notch to James Bond’s gunbelt. Four previous Bond films have received nominations for Best Original Song. And in 2013, British chanteuse Adele took home a golden statuette for the title track of Skyfall.

For me, the piece is well crafted, but falls somewhere in the middle of the Bond music pantheon. Not quite the peaks of Shirley Bassey’s “Goldfinger” or Paul McCartney’s “Live and Let Die.” But also not the dregs of Rita Coolidge’s “All-Time High” or A-ha’s “The Living Daylights.” “Writing’s On the Wall” is vaguely Bond-ish in much the same way that Smith’s smash hit, “Stay With Me,” contained strong echoes of Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.”

The last nominee is “Simple Song #3” from Youth. Of all the nominees, David Lang’s piece is the one most firmly integrated into the film’s narrative. “Simple Song #3” is featured at the end of Youth, performed onscreen by singer Sumi Jo, violinist Viktoria Mullova, and the BBC Concert Orchestra.

The song is a classic “Adagio” structured around a repeated descending string figure. Gradually, other instruments are added, creating patterns of shifting harmony that surge beneath Jo’s vocal line.

Although “Simple Song #3” doesn’t appear till the end, the song is mentioned at several earlier moments as the work of the film’s protagonist, Fred Ballinger (Michael Caine). Ballinger is a retired composer and conductor lured back to the stage by an invitation from the Queen to perform for Prince Philip’s birthday. According to Lang, the piece offers a window into Ballinger’s psychology. It balances both the aspirations of his youth with the melancholy of a life lived apart from the woman he loved.

Placed in the film’s climax, Ballinger’s work provides an emotional capstone that operates at several levels. Given the complexity of its narrative function, “Simple Song #3” is not so simple.

Prediction: As a longtime Antony and the Johnsons fan, I would be delighted to see Hegarty and Ralph making their acceptance speech on Sunday night. But it seems to be Lady Gaga’s year so far. After winning a Golden Globe for her work on American Horror Story: Hotel, singing the national anthem at the Super Bowl, and performing a tribute to David Bowie at the Grammys, Gaga will cap off a stellar start to the new year by walking home with Oscar on her arm. It will also provide career recognition to Diane Warren, whose music has graced more than 200 different films and television shows. After last year’s disappointment, Warren finally will get the opportunity to be forever “Grateful.”

Old White Men and Even Older White Men: Best Original Score

Sicario (2015).

The nominees for Best Original Score are a group of seasoned craftsmen who collectively have received more than seventy Oscar nominations and have written music for more than seven hundred feature films. At age 46, Jóhann Jóhannsson is the youngster of the group. Carter Burwell and Thomas Newman both turned sixty late last year. And John Williams and Ennio Morricone are both octogenarians.

Jóhannsson is nominated for his score for Denis Villeneuve’s drug war thriller Sicario. The Icelandic composer received a nod last year for The Theory of Everying, but lost out to Alexandre Desplat’s charming Euro-pudding score for The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The score for Sicario, though, couldn’t be more different than that for The Theory of Everything. Where Everything’s music was lilting and lyrical, Sicario’s is tense and ominous, emphasizing rhythm, timbre, and texture over more conventional structures of melody and harmony. Several cues are organized around pounding drum patterns punctuated by sustained, dissonant blasts of strings and low brass. In an interview, Jóhannsson recalled, “I think the the percussion came first, and then I started to weave the orchestra into it. Very early on I decided to focus on the low end of the spectrum—focus on basses, contrabasses, low woodwinds, contrabassoon, contrabass clarinets and contrabass saxophone.”

Other cues also emphasize percussive textures, but with the instrument sounds processed so that they sound driven to the point of distortion. Even a more restrained cue like “Melancholia” still maintains a quiet intensity, structured around a cyclic harmonic pattern played on acoustic guitar in a vaguely flamenco style. The score is brutally effective in capturing the mood of Sicario’s taut action scenes. In fact, for me, Jóhannsson’s score was, without question, the best thing in the film.

The Old Hands: Carter Burwell and Thomas Newman

Carol (2015).

Carter Burwell received his first Oscar nomination this January for his score for Todd Haynes’ Carol. Burwell got his start on the Coen brothers’ debut, Blood Simple (1984), and has been a regular collaborator ever since. He has also worked regularly with a number of other filmmakers, such as Charlie Kaufman, Spike Jonze, and Bill Condon. Given the rather quirky and absurdist tone found in many of their projects, Burwell’s great gift is to provide music that emotionally grounds the characters, finding notes of lyricism, melancholy, and pathos in the strange stories of lovelorn puppeteers, sex researchers, and bumbling kidnappers.

For Carol, Burwell tried to capture the peculiar mixture of passion and distance that characterizes Therèse’s initial attraction to Carol. Because Carol comes across as both elegant and a bit aloof, Burwell not only utilized ambiguous harmonies, but also “cool” instruments, such as piano, clarinet, and vibes.

On his website, Burwell identifies three main musical themes in his score for Carol. The first is a love theme introduced in the film’s opening city scene. It presages the relationship even before we’ve been introduced to the characters. The second theme underscores Therèse’s fascination with Carol. Says Burwell, “This is basically a cloud of piano notes, not unlike the clouded glass through which Todd Haynes and Ed Lachman occasionally shoot the characters.” The third theme captures the characters’ sense of loss when they are separated. Knowing that Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara would convey the characters’ pain in their performances, Burwell opted instead to use open harmonies (fourths, fifths, and ninths) to communicate their sense of emptiness.

Burwell orchestrated the music for chamber-size ensembles to maintain the sense of intimacy between the characters. Some cues feature as few as four instruments while others were performed by as many as 17 musicians.

Burwell’s spare, modest score is a departure from the style Haynes explored in his previous foray into this territory: his Douglas Sirk homage, Far From Heaven (2002). Elmer Bernstein’s score for that film was lush and emotionally expansive, aping Frank Skinner’s musical stylings in films like Magnificent Obsession (1954) and All That Heaven Allows (1955). Burwell wrote only 38 minutes of music. Yet it all is beautifully attuned to the film’s mood of quiet desperation.

Thomas Newman earned his thirteenth nomination for Bridge of Spies. (Insert Susan Lucci joke here.) Newman, of course, descends from film composing royalty as the son of the renowned classical Hollywood tuner, Alfred Newman. Yet, despite Newman the Younger’s distinguished career in Tinseltown, Newman the Younger has a long way to go to catch his pops. Alfred won nine Oscars and accrued more than forty nominations.

Newman’s music has graced some of the most beloved American films of the past three decades, such as The Shawshank Redemption, American Beauty, Finding Nemo, and Wall-E. Although he is known for his versatility, an NPR story on his score for Bridge of Spies notes that Newman has become known for passages that incorporate “quirky, layered piano writing and jagged string motifs.”

Newman and Spielberg save the score’s biggest moments for the film’s climax and epilogue. Indeed, more than half of the film’s score is backloaded into its last three cues, which together account for about 25 minutes of music. Displaying Newman’s full emotional range, “Glienicke Bridge” anxiously underscores the tense prisoner exchange that delivers Rudolf Abel back into Soviet hands. “Homecoming” features solo trumpet and oboe to convey James B. Donovan’s sense of validation now that his fellow commuters’ scowls of disapproval have turned to smiles of patriotic pride.

Newman’s score for Bridge of Spies is a very solid piece of work evincing the craft and refinement displayed by earlier masters like Jerry Goldsmith and John Barry. Yet the music’s modesty and conventionality make it the kind of score all too easy to overlook.

The Legends: John Williams and Ennio Morricone

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015).

Oddsmakers have tabbed our final two nominees, John Williams and Ennio Morricone, as the most likely to take home the big prize. The former is nominated for Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the seventh film in George Lucas’s series and the seventh scored by Williams. Coming 48 years after the composer’s Oscar win for the first Star Wars film, Williams’s music updates the neo-Romantic style he helped to revive in the 1970s. It also adds new themes for key new characters, such as Rey and Kylo Ren.

Williams wrote a massive amount of music for The Force Awakens. (Indeed, the 102-minute score is more than double that of Newman’s score for Bridge of Spies.) But very little of it simply replicates materials from the previous films. By Williams’s own count, only seven minutes of the score function as “obligatory” references to his own immediately recognizable themes.

As in his previous work, Williams shows enormous skill in juggling the various leitmotifs that are attached to the film’s dramatic personae, often moving a motif through different instrument combinations in order to vary the color and timbre of each cue. And Williams’s sure touch with this material undoubtedly enhances J.J. Abrams’ everything-old-is-new-again approach to The Force Awakens, a strategy that seems to have satisfied long-time fans, many of whom probably have dusty old compact discs of the composer’s earlier Star Wars scores.

The score for The Force Awakens earned Williams’s his fiftieth nomination and it is a fine addition to his already considerable oeuvre. Still, considering that Williams has won Oscars on five previous occasions and the been-there- done-that aspect of the enterprise, it is hard to believe that this score will bring the composer his sixth statuette. Thankfully for him, Williams’s reputation as one of the greatest composers to work in the film medium is already firmly secured.

That leaves just Ennio Morricone, the equally legendary Italian composer whose collaborations with Sergio Leone redefined the sound of the Western. Nearly fifty years after Morricone’s theme from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly topped U.S. record charts, Morricone garnered his sixth Best Original Score nomination for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight.

The film marked Morricone’s return to the genre after several decades of avoiding it. According to the composer, most directors who approached him simply wanted him to replicate the sound of his great Spaghetti Western scores. Morricone preferred to pursue projects that let him stretch in other directions.

Tarantino gave the Maestro a free hand in developing the score of The Hateful Eight, and Morricone responded with one of his best scores in decades. Aside from his characteristic use of vocal chants as rhythmic accents, the score for The Hateful Eight largely avoids the sort of psychedelic touches and extravagant tone colors found in his Spaghetti Western scores. Gone are the electric guitar, ocarina, whistles, and coyote yelps that established Morricone as a kind of musical meme. Substituted instead are much more conventional orchestral colors with the strings and wind sections taking prominent roles in The Hateful Eight.

Perhaps one reason for this move back to classical Hollywood convention is due to the hybrid qualities of Tarantino’s story. As Peter Debruge noted in his Variety review, The Hateful Eight is “a salty hothouse whodunit that owes as much to Agatha Christie as it does to Anthony Mann.” Morricone himself seems to concur. In an interview with Rolling Stone, the composer added, “Quentin Tarantino considers this film a Western; for me, this is not a Western. I wanted to do something that was totally different from any Western music I had composed in the past.”

Morricone’s score has a “theme and variations” structure that shows him adeptly changing his tempo, texture, and instrumentation to adapt his main theme to new dramatic contexts. His Overture provides the basic template for the score. The low strings and winds play a sustained minor chord that sneaks into the soundtrack. After a few seconds, the upper voices enter playing chords on the first and third beats of each measure to outline the basic harmonic progression of the main theme. Eventually an oboe will enter playing a repeated interval as a counterrhythm over the top of this pattern.

This gives way to the strings, which intone a serpentine diatonic melody that provides the spine for the rest of the cue. Gradually, Morricone introduces more instruments, such as vibes and brass, to vary the tone color and even adds a simple bridge section that consists of a series of soft, chromatically descending chords. After a brief restatement of the main melody, the cue finishes with a series of long sustained chords marked by shifting harmonies in the inner voices. The clarinet plays a fragment of the main theme before it eventually fades out. The cue never comes to the kind of climax that a traditional cadential structure would provide. Instead it simply unwinds itself.

The central theme is probably given its most elaborate treatment in the main title, “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock – Version Integrale.” A steady timpani pulse and a sustained pitch in the strings provide a pedal tone against which a new melody is introduced in the contrabassoon’s low register. This musical figure has a serpentine quality like the other, and it has been written to function as counterpoint to its predecessor at later moments when the two will be interleaved. Morricone gradually introduces more instruments to thicken the texture and even adds brass and pizzicato accents as embroidery atop the main theme. A hi-hat cymbal adds some rhythmic variety to the basic pulse of the timpani.

After a brief detour into some transitional material, the main melody returns, but now played by strings, xylophone, and muted brass instruments. The main musical figure continues to be restated with new ideas simply piled on top. As the music grows in both volume and intensity, Morricone adds trills and furious agitato string runs to create a cacophonous, but organized musical chaos. The cue climaxes with the melody played fortissimo in octaves by the violin section, soaring toward a sudden and abrupt stop. After a short pause, the contrabassoon quietly returns to play a brief musical coda that eventually fades to silence.

Morricone has long been a master of this type of musical structure. He’ll start with a simple musical idea, but then adds different countermelodies or obbligatos to vary its mood and tone. The ongoing accretion of elements creates the effect of a long crescendo that eventually finds release in silence. (For an earlier example of this kind of technique, see his cue for “The Desert” on The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly soundtrack.)

Beyond its purely musical effectiveness, though, “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock” exudes a roiling tumult that fittingly captures the sense of deception and distrust that will pervade Minnie’s Haberdashery. The musical mood remains mostly dark and ominous throughout, leavened only by the bright solo trumpet fanfare that underscores Sheriff Chris Mannix’s reading of Major Warren’s Lincoln letter.

Tarantino’s trust in the Maestro was amply rewarded. This is a score that no one but Morricone could produce. As was the case with Jóhann Jóhannsson’s score for Sicario, it seems to be the best thing about The Hateful Eight. Tarantino wanted a soundtrack album for one of his own films that he could proudly place alongside other Morricone albums in his collection. He got it and then some.

Prediction: The Maestro finally gets his due! Although Morricone received an honorary Oscar in 2007 for his “magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the art of film music,” none of his individual scores have received awards from the Academy. I expect that to change next Sunday night. In fact, betting odds put Morricone’s chances of winning an Oscar for Best Original Score at 1 to 5. That means that a five dollar bet will net you one dollar profit if you win. That is about as close to a sure thing as you are likely to find in the gambling world. And even I’m not dumb enough to buck that trend.

In truth, I would be happy to see any of these composers take home the Oscar. I’ve enjoyed their contributions to the art of film music for much of my adult life. But, for me, the only real question is this: How long will the standing ovation be as Ennio Morricone prepares to give his acceptance speech? I put the over/under at 65 seconds.

Variety offers overviews of the nominees for Best Original Song here and Best Original Score here. Both pieces include comments from the composers and songwriters competing for this year’s awards.

You can find interviews with nearly all of the nominees for Best Original Score: Morricone, Williams (here and here), Newman, and Johannsson. Carter Burwell’s notes on Carol can be found on his website.

Emilio Audissino’s book on John Williams offers a terrific overview of the composer’s career. For a study of Morricone’s compositional techniques and style, see Charles Leinberger’s monograph on The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly in Scarecrow Press’s series of Film Score Guides. My book The Sounds of Commerce includes a chapter on Morricone’s spaghetti western scores.

More on Morricone: The Maestro weighs in on the film scoring process in Composing for the Cinema: Theory and Practice of Music in Film, which is coauthored with Sergio Miceli. You can listen to the opening cue of the score for The Hateful Eight here.

P.S. 25 February 2016: Thanks to Peter Brandon for a correction concerning the Canadian identity of The Weeknd, Quenneville, and Belly.

LONDON, ENGLAND – DECEMBER 08: Composer Ennio Morricone is seen during a Live Recording for the H8ful Eight Soundtrack at Abbey Road Studios on December 8, 2015 in London, England. (Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Universal Music)

Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO

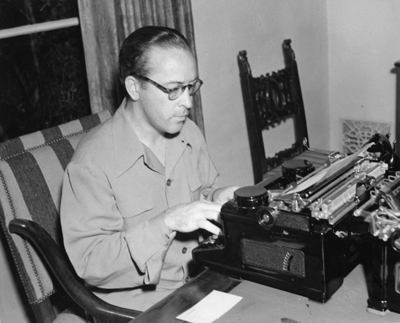

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo; John Frankenheimer and Dalton Trumbo.

DB here:

Who better to comment on the historical implications of Jay Roach’s Trumbo than our friend and collaborator on Film Art, Jeff Smith? He’s not only an expert on film sound, as he showed in his guest post on Brave, but he has written a book on the Hollywood blacklist. Jeff offers these observations on the film.

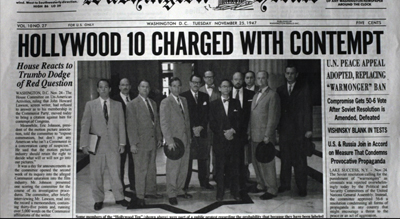

Last week, I was delighted to see that Bryan Cranston received an Oscar nomination as the star of Trumbo. Throughout the month of November, I was “johnny-on-the-spot” for local media interested in covering the new biopic about Dalton Trumbo. The story had a local angle. In 1962, Trumbo donated a large collection of scripts, notes, contracts, photos, and business correspondence to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Since then, scholars interested in the Hollywood blacklist have been making pilgrimages to Madison to probe Trumbo’s collection as well as the papers of five other members of the Hollywood Ten (Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner Jr., Herbert Biberman, Samuel Ornitz, and Alvah Bessie.)

I had done a lot of work with the collection, so I could do interviews with WMTV, WISC, The Wisconsin State Journal, and University Publications. Unfortunately I had not yet seen Trumbo, the Jay Roach film based upon Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography. I could talk about Trumbo’s life and career and the buzz I’d heard about the movie, but until it played Madison, I had to stay mum about the movie itself.

After a couple of weeks in distribution in limited release, Trumbo went wide just before Thanksgiving. Now that I’ve seen it, I am delighted to report that Trumbo merits every bit of the hype that surrounded it. To my mind, it is the best fictional film about the blacklist that Hollywood has yet produced.

Buoyed by a standout performance by Cranston, Trumbo is fast-paced and funny, and rather nimbly summarizes many of the political and industrial issues that led to the institution of the blacklist in 1947. It also showcases the effect that “unemployable” writers working on the black market had in undermining the rhetoric of the blacklist throughout the Cold War period. It became hard to say with a straight face that you were protecting American screens from the taint of Red propaganda when films secretly written by Communists were winning awards and topping the box office.

I was struck by some of the choices made by Roach and screenwriter John McNamara in bringing Trumbo’s story to the big screen. Although Trumbo’s career has been well documented by film scholars, Roach and McNamara faced the same challenges in adapting Cook’s biography that any filmmaker does in transforming a literary property into a classical narrative structure. How do you make Trumbo an active, goal-oriented protagonist despite the fact that he was the victim of historical circumstance? How do you deal with the welter of historical actors and subplots that populate Cook’s biography? How do you boil down a complex historical situation into a clear, transmissible narrative?

Witnesses, friendly and otherwise

Dalton Trumbo at work.

Like many contemporary Hollywood biopics, Trumbo doesn’t try to convey the full sweep of its subject’s quite colorful life. It omits reference to young Dalton’s Christian Scientist upbringing, his early toils in the Davis Perfection Bakery, or even the publication of his first story in 1933. Indeed, the film also makes only offhand references to Trumbo’s early achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. These are briefly acknowledged near the film’s start through a series of shots in Trumbo’s office at the Lazy-T Ranch that reveal his award for Johnny Got His Gun and his Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle.

Instead the film focuses on the period of Trumbo’s career during which the screenwriter became one of Hollywood’s sacrificial lambs at the altar of HUAC’s anti-Communism. When the film begins in the mid-forties, Trumbo was the most highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood, earning $75,000 per script. In today’s currency, that amounts to about $800,000 per picture, a remarkable sum for someone under studio contract.

Just a few years later, Trumbo would appear as an “unfriendly witness” during hearings conducted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in October of 1947. As a result, he’d eventually be convicted of Contempt of Congress charges and sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky.

Although HUAC was concerned about the potential subversion of American screen content, it was not, in fact, illegal to be a member of the Communist Party. It was, however, a criminal offense to advocate for the overthrow of the American government according to the provisions of the Alien Registration Act (aka the Smith Act) passed in 1940.

About six months after HUAC concluded their hearings on Hollywood, a dozen Communist Party leaders were indicted for Smith Act violations. Defendants insisted that political change in America could be accomplished through democratic process and constitutional principle. But prosecutors claimed these statements couldn’t be trusted since Communists employed “Aesopian language” and therefore did not really mean what they said. The attack proved successful and effectively criminalized membership in the Communist Party as a result. Since any individual’s denial of revolutionary rhetoric would be viewed with suspicion, you were likely seen as guilty of the Smith Act if you simply owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto.

Even before the Foley Square trials, as they came to be known, many of the Communist Party’s rank and file, including the Hollywood Ten, also feared that they would be prosecuted on similar grounds if they admitted their membership. This proved to be one factor that favored the Ten’s failed “first amendment” defense. True, they risked getting cited for Contempt of Congress. But that had the prospect of looking more dignified than simply being hauled off in cuffs on Smith Act charges.

When he returned from prison, Trumbo encountered an industry that wanted him, but not his name on the credits. Producers recognized his talent, and he continued to write through the circuitous network of fronts and pseudonyms. Trumbo would win two Oscars for his work as a black market screenwriter: one for the Gregory Peck/Audrey Hepburn classic, Roman Holiday (below) and another for a Disneyesque “boy and bull” story, The Brave One.

By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s name would once again grace movie screens as the credited screenwriter on Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and on Otto Preminger’s Exodus. This moment essentially ended what remained of the Hollywood blacklist. In moving from the limelight to the shadows and back again, Trumbo’s life had the kind of plot arc that Hollywood loves. It’s a story of redemption in which the hero overcomes overwhelming odds to regain the professional respect and recognition he’d been denied.

Although all of this suggests that Trumbo is a pretty conventional biopic, it’s quite unconventional in its treatment of the blacklist. As the late Jeanne Hall noted years ago, Hollywood’s representation of this dark chapter of its past was surprisingly evasive, getting on the right side of history but for all the wrong reasons.

Bad Faith in Appleton

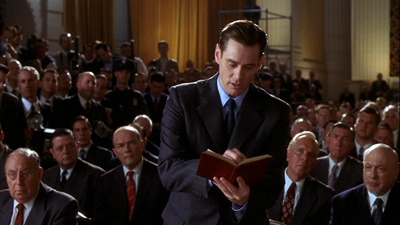

The Majestic (1999).

In titles like The Way We Were, The Front, and Guilty by Suspicion, filmmakers pulled a “bait and switch.” They substituted obvious cases of injustice for the much messier questions posed about HUAC’s abrogation of basic civil rights protections. The Hollywood Ten tried to defend themselves on First Amendment grounds, questioning whether HUAC itself had the right to invade their privacy or to limit their freedom of assembly. But in most of these earlier films about the blacklist, HUAC’s inquiry eventually entangles someone who was never a member of the Communist Party. In The Way We Were, the WASP-y Hubbell comes under suspicion for his relationship with the Jewish radical, Katie. In The Front, Howard comes under suspicion after selling black market scripts by Communist writers under his own name. Both of these instances present obvious cases of individuals wrongfully accused. They recruit our sympathies for characters that suffer as a result of HUAC’s tactics, but gloss over more fundamental questions about whether someone should be denied employment on the basis of their political beliefs.

No film, however, displays the equivocation evident in previous representations of the blacklist as vividly as Frank Darabont’s The Majestic. The protagonist, Peter Appleton, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has just been named by the committee. Distraught, he takes a drive out of Hollywood, but has an accident en route. Suffering from amnesia, Appleton finds himself in the small town of Lawson, California where is mistaken for Luke Trimble, a soldier killed in action some nine years earlier. Appleton becomes immersed in the Lawson community, helping his “father,” Harry, restore the small town theater that gives the film its title. Prompted by a combat film shown in the Majestic, Appleton regains his memory, and confides the truth of his situation to his new girlfriend. After his car is discovered, federal agents give Appleton a summons to testify about his Communist affiliations.

During the climax, Appleton appears before HUAC with the aim of clearing himself. Congressman Elvin Clyde confronts Appleton with evidence that he attended a meeting of the “Bread Instead of Bullets” club. Appleton pleads innocence, saying he only went because he was a “horny, young man” seeking to impress his date, Lucille Angstrom. Just as he is about to deliver his prepared statement purging himself of Communist associations, Appleton changes his mind. Instead he gives an impassioned speech that cites his First Amendment rights and denounces the investigation as a betrayal of America’s real ideals. Appleton saunters out of the hearing to the loud applause of onlookers. Yet Appleton’s lawyer later tells him that Angstrom is currently a CBS producer on Studio One, and his reference to her as a member of the Communist front organization is viewed as cooperation with the Committee.

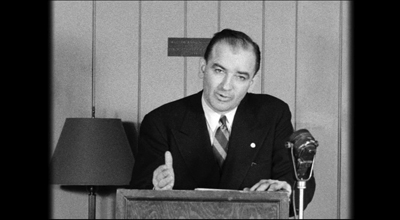

In The Majestic’s civic fantasy, the committee hearing revives the “wrongly accused” trope seen in earlier blacklist films. Worse, it shows its hero successfully using the First Amendment legal defense that had spectacularly failed when the Hollywood Ten used it during the 1947 hearings. Moreover, because Appleton is a political naïf, his inadvertent naming of names redounds to his benefit. Given the film’s hopelessly confused politics, perhaps there is unintentional irony in the fact that Appleton is also the name of the Wisconsin hometown of Senator Joseph McCarthy (below), the man synonymous with the Cold War’s anti-Communist campaign.

Trumbo, in contrast, doesn’t pull any punches. The film condemns HUAC’s activities not because it was prone to wild, unproven accusations like those of McCarthy, but rather because the very nature and essence of its inquiry was itself an abuse of power. The movie does nothing to deny Trumbo’s guilt. Indeed, the real-life Trumbo freely admitted it. In the 1976 documentary Hollywood on Trial, Trumbo described his reaction to his trial thusly: “As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since.”

Yet, while not excusing Trumbo’s actions, the film dramatizes the debilitating effects of being blacklisted, both in his professional and personal life. The burden of Trumbo’s black market work put a strain on his marriage and his family, all of whom were enlisted to perform services he himself could not do publicly.

The blacklist: More than Red-baiting

Besides providing a more accurate picture of Red-baiting and its effects, Trumbo also proves remarkable in making passing reference to some of the important secondary causes that eventually led to the blacklist. An early scene, for example, shows Trumbo (above) on a picket line during the vituperative Congress of Studio Union strikes that took place in 1945. Film historian Jon Lewis argues that one reason for the studio’s cooperation with HUAC’s investigation was that it served their interests in their long-term relationship with Hollywood’s craft guilds. Once Communists within the film industry’s labor unions became targets of government scrutiny, only the more moderate factions remained. Whether or not HUAC’s investigation was a direct cause, Hollywood did not experience another strike until more than four decades later.

Trumbo refers to another cause of the blacklist: anti-Semitism. Although it was something of a stereotype, Communists were popularly associated with European Jews. In fact, when Warner Bros. released I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, several moviegoers wrote studio head Jack Warner complaining that the film repeated the lie that all Jews were Communists. Said one Julius Newman of Roxbury, Massachusetts: “I demand that this dangerous, rotten, and libelous bit of propaganda be withdrawn immediately before some Jewish mother somewhere, gets her son’s skull cracked for Mother’s Day.”

The perception that anti-Semitism was an underlying cause of the blacklist was aided by the fact that three of the Committee were members of the Ku Klux Klan at the time of the 1947 hearings, including the Chair, J. Parnell Thomas. Moreover, in a speech before the House of Representatives, another HUAC member, Mississippi Democrat John Rankin, attacked members of the Committee for the First Amendment, who had lobbied on behalf of the Hollywood Ten. Rankin claimed that certain performers were suspect because their Anglicized names hid their actual Jewish origins:

One of the names is June Havoc. We found that her real name is June Hovick… Another one is Eddie Cantor, whose real name is Edward Iskowitz. There is one who calls himself Edward Robinson. His real name is Emanuel Goldenberg. There is another here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg.

Screenwriter John McNamara wrote a similar speech for Trumbo, but placed it in the mouth of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. When MGM boss Louis B. Mayer reminds Hopper that the legal situation was complicated by the fact that several of the Hollywood Ten had contracts, she responds:

Then how about I make crystal clear to my thirty-five million readers who runs Hollywood and won’t fire these traitors? How about I name names, real names? Like yours, Lazar Meir; or Jack Warner, Jacob Varner; Sam Goldwyn, Schmuel Gelbfisz.

The presence of Hedda Hopper in Trumbo hints at a third underlying cause of the blacklist: the role of the trade press and gossip columnists, who prosecuted and enforced it. Hopper was not alone in this endeavor. Publishers like Billy Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter and columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan “cheered” HUAC’s efforts from the sidelines. They also helped the enforcement of the blacklist once it was instituted, calling public attention to the surreptitious presence of banned writers on the black market.

All of these elements in Trumbo’s script make it a richer, more sophisticated depiction of the Hollywood blacklist than that offered by its predecessors. They also remind us that its operations were about more than just politics. Once the blacklist was established, studio bosses gained the upper hand in their dealings with labor, gossipmongers used rumor and accusation to fill column inches and sell papers, and anti-Semites exploited the common association of Communism and Jewish intellectuals to thwart activism among progressives, including those in the Civil Rights movement.

In sum, Trumbo offers a more nuanced sense of the various factors at play at the time of the blacklist than virtually all of its cinematic predecessors. This makes it all the more surprising then that the film nonetheless rewrites history in other ways. In an effort to both streamline and personalize its protagonist’s story, Trumbo invents new characters, revises the order of historical events, and shorts the achievements of other black market screenwriters who also contributed to the blacklist’s ultimate demise.

The eleventh member of the Hollywood ten

Although most film audiences expect that movies will generally portray historical events with some degree of accuracy, Hollywood cinema rewrites history all the time. Despite the fact that this is common practice, some films that take such liberties are hurt by negative publicity, especially around awards time. Recall the controversy surrounding Selma’s depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as an opponent of Martin Luther King’s famous march rather than as a “behind the scenes” ally. Some believe that the loud complaints coming from the LBJ camp cost director Ava DuVernay an Oscar nod.

Trumbo is no exception to this principle, even though it has been unusually forthright about the changes made to the historical record. My spidey senses were alerted to this during the movie when they introduced Louis CK’s character as “Arlen Hird.” I’d never heard of Arlen Hird.

Both in interviews and in an article in the New York Times, screenwriter John McNamara has acknowledged that Hird is a composite character, whose traits and experiences are based on five other members of the Hollywood Ten. Louis CK, for example, physically resembles the real-life Alvah Bessie, who, like the character, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish civil war.

Moreover, when Hird is in prison, he hears a radio broadcast of Edward G. Robinson’s “friendly” testimony. Robinson calls him “the top fellow who they say is the, uh, commissar out there,” a swipe that blacklist historians would immediately associate with John Howard Lawson. And sadly, like Samuel Ornitz, Hird dies after battling cancer, having never seen the blacklist come to its ignoble end.

As Nicolas Rapold observes in the Times, Hird is meant to stand in for other Communist screenwriters whose attitudes were more doctrinaire than Trumbo’s. Yet I believe the real purpose of using a composite character is to simplify the historical record to make it more digestible for the viewer. Rather than tracing out Trumbo’s relation to all of the eighteen other “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed by HUAC, McNamara opts to consolidate them into a single character. Such a decision makes some intuitive sense, since viewers would be hard pressed to keep tabs on a parade of many characters. By creating Hird as a composite, Trumbo’s interactions with him gain vividness and salience.

Still, McNamara’s narrative technique is merely one approach among a larger menu of options, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. He could have treated the Hollywood Ten as a group protagonist, who all share the same goal in legally challenging HUAC’s authority. Such a gambit, though, would have displaced Trumbo from the center of the story early on. That decision would have weakened the causal motivation behind his later emergence as a black market crusader.

Alternatively, McNamara could have dramatized Trumbo’s individual interactions with Bessie, Lawson, and Ornitz, et.al., using a superimposed title to identify each one. The gain in accuracy, though, would likely mean a loss of dramatic clarity and a mildly more self-conscious style of narration. More important perhaps, it also would make for a less emotionally engaging story. The film shows Hird confiding in Trumbo at the Lazy-T ranch, participating in the Ten’s legal strategy, serving his prison term, and undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The accumulation of these details provide for a more fully fleshed out character. There’s also the opportunity to feel empathy for Hird’s children at his funeral, an effect that couldn’t have been as focused if Hird’s problems were scattered among separate individuals.

None of this is meant to suggest that McNamara absolutely made the right choice in deciding to treat so many members of the Ten as a composite. Rather, it is simply the recognition that such a technique is the result of a deliberate choice and further that one creative decision can lead to a cascade of others. Had McNamara stayed doggedly faithful to the historical record, Trumbo would have been a different film, but perhaps not a better one.

Perhaps we should recognize that screenwriters often must adapt historical narratives in the same way that they adapt literature. And the same sorts of questions about fidelity will bedevil us as when films change details of our favorite novels and stories. Rather than being dogmatic in expecting that historical films stick close to the facts, maybe we simply should ask whether the film is faithful to the spirit of the historical record, especially when its creators are so open and honest about the changes they made. Such a stance would at least recognize the difficulties faced by screenwriters in balancing the weight of classical narrative conventions against the strict measure of historical accuracy. If, as many screenwriters argue, films differ from literature in their emphasis on conflict and action, then the decision in Selma to treat LBJ as an obstacle to Martin Luther King’s goal makes a certain dramatic sense. Here again, one can debate the merits of that creative choice. But at least we do so with a fuller understanding of why such choices are made in the first place.

Get me rewrite!

Besides creating composite characters, McNamara rewrites history in other ways. Perhaps the most obvious is when he creates a scene in prison between Trumbo and HUAC chair, J. Parnell Thomas, which never actually happened. True, Thomas was convicted on corruption charges and was sent to federal prison. But he served his term in Danbury, Connecticut rather than Ashland, Kentucky where Trumbo was incarcerated.

In this case, the real-life story proves more entertaining than what appears in the film. While at Danbury, Thomas encountered two other members of the Hollywood Ten – Lester Cole and Ring Lardner, Jr. — serving their time on Contempt of Congress charges. Upon seeing Thomas working in the prison yard, Cole made a wisecrack that led the former HUAC chair to respond, “I see that you are still spouting radical nonsense.” Cole’s sharp retort: “And I see you are still shoveling chicken shit.”

In other cases, McNamara revises the chronology of events. In the film, Trumbo first meets with the King Brothers, Frank and Hymie, just after he is released from prison. In reality, Trumbo started working for the King Brothers just weeks after his HUAC testimony. Almost immediately after being suspended by MGM, Trumbo did black market work on the screenplay for the King Brothers’ cult classic, Gun Crazy, using fellow writer Millard Kaufman as a front. With Kaufman serving as intermediary, the Kings likely did not know of Trumbo’s involvement. But the brothers began working directly with Trumbo shortly thereafter. In fact, Frank King personally visited the Lazy-T ranch just prior to the Trumbo’s departure for prison, offering to pay him $8,000 to write the script for Carnival Story.

Trumbo coyly acknowledges the screenwriter’s contribution to Gun Crazy by featuring posters of the film in several shots. But by revising the historical circumstances of Trumbo’s first involvement with the Kings, the film more or less denies him actual credit attribution, ironically engaging in the same sort of opportunism displayed by the producers who surreptitiously hired him.

McNamara’s most significant changes to blacklist history, though, involve omissions. Trumbo’s Oscar victory for The Brave One is well documented and the episode – both in the film and in real-life – neatly captures his role as industry gadfly. But the same year that the mysterious “Robert Rich” won the Academy Award for Best Original Story, Michael Wilson also was nominated for a project for which he was publicly denied screen credit.

Wilson had completed a first draft of Friendly Persuasion for director Frank Capra in 1946, but no film was made from the script until producer/director William Wyler took over the project in 1955. When it came time to determine the screenwriter credit, Wyler suggested that it go to Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West for their extensive revisions, including many rewrites completed on set during shooting. When Wilson became aware of this, he immediately protested Wyler’s decision and forced arbitration by the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild ruled in Wilson’s favor, but also reminded the film’s distributor, Allied Artists, that they could legally deny credit to any screenwriter who had failed to clear himself before HUAC. When Friendly Persuasion was released in 1956, its only writing credits read “From the Book by Jessamyn West.”

Despite a good deal of press coverage of the dispute, the incident might have been a mere blip on the cultural radar if not for the 1957 Oscar nominations. When they were announced, a film with no credited screenwriter unexpectedly received a nomination for a screenwriting award. And with public acknowledgement of Wilson’s contribution to Friendly Persuasion more or less verboten, the text of the nomination simply said the writer was ineligible under Academy rules.

Worried that a public victory by a blacklisted writer would give the industry a big ol’ black eye, the Academy reportedly instructed Price Waterhouse to excise the nomination from the Oscar ballots that were sent to voters. Yet, even though the Academy essentially rigged the vote against Wilson, Groucho Marx offered an incisive quip about Wilson’s situation at the Writer’s Guild Awards banquet held about two weeks before the Oscars. Said Groucho, “The Ten Commandments. Original story by Moses. The producers were forced to keep Moses’s name off the credits because they found out he had once crossed the Red Sea.” Given all the effort that went into preventing Wilson from receiving the award, Trumbo’s Oscar win as “Robert Rich” must have tasted even sweeter. The award was given in absentia by Deborah Kerr, and Jesse Lasky, Jr. accepted it.

Moreover, the Rich incident was hardly the last humiliation that the Academy would suffer. The very next year novelist Pierre Boulle received a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination for The Bridge on the River Kwai, which was based on his book. But Boulle had been a front for Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, who had taken the assignment as black market work for producer Sam Spiegel. When Boulle’s name was announced as the winner, the novelist was nowhere to be found. Instead, Kim Novak accepted the award on his behalf. But insiders knew exactly why Boulle was absent. As someone who wrote and spoke in French rather than English, his stumbling acceptance speech would have exposed the hypocrisy by which Foreman and Wilson were denied an award that they merited. (Sadly, neither Foreman nor Wilson would live to see their work duly recognized. In 1984, the Academy posthumously recognized them as the true authors of Kwai’s screenplay.)

Nathan E. Douglas = ?

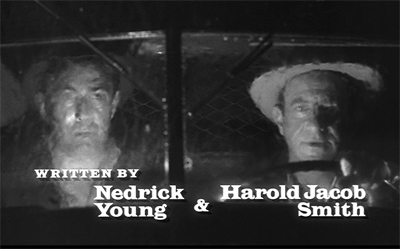

The original credits sequence of The Defiant Ones (1958) listed Nedrick Young as a coauthor under his pseudonym Nathan E. Douglas. He appeared in a bit part coinciding with his credit listing, along with coauthor Smith, in the cab of the truck. Video versions such as this have restored his name.

Things didn’t end there. The Oscar nominations in 1959 saw yet another brewing controversy regarding eligibility of a black market scribe. The writing team of Harold Jacob Smith and Nathan E. Douglas earned a nod for Best Original Screenplay for The Defiant Ones, even though the latter was a pseudonym for blacklisted writer Nedrick Young. If anything, Young’s participation in the making of The Defiant Ones was signaled by producer-director Stanley Kramer’s giving him a notable cameo in the film. During the opening credits, Young and Smith are both seen as prison guards riding in the front seat of a truck used to transport convicts. In a rather coy gesture, when the film’s writing credits are shown, Young’s pseudonym “Nathan E. Douglas” is superimposed over the man himself. Even though the general public didn’t know Young from Adam, his cameo made his participation an open secret in Hollywood.

During awards season, Young as “Nathan Douglas” collected a lot of hardware, including awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Writer’s Guild of America. With the nominations imminent, leadership within the Academy recognized that a third straight public relations disaster was in the offing. Just before Christmas in 1958, former Academy president George Seaton approached Young and Smith seeking assistance in overturning the Academy bylaw prohibiting blacklisted personnel from eligibility for awards. For his part, Trumbo himself stayed abreast of the situation and even rescheduled a media interview order to avoid fanning any flames of opposition from within the Academy.

On January 15, 1959, Seaton, Young, and Trumbo all got their wish as the hated bylaw was officially rescinded, passed by the Academy’s Board of Governors with near unanimous support. Two days later, Trumbo confirmed to newsman Bill Stout that he was, indeed, Robert Rich. On Oscar night a few months later, Young enjoyed the spotlight in a way that had been denied his predecessors. And when The Defiant Ones won the Oscar for the Best Story and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, Young strode to the podium along with Smith and offered a humble thank you. Ward Bond, one of John Wayne’s allies in the Motion Picture Alliance for American Ideals, observed: “They’re all working now, all these Fifth-Amendment Communists. We’ve just lost the fight. It’s as simple as that.”

Where does all of this backstory fit into the story told in Trumbo? As it turns out, nowhere. In choosing to concentrate on Trumbo’s story, the movie keeps all of this rich contextual material offscreen. As is often the case, the historical realities surrounding the end of the Hollywood blacklist were much denser, messier, and more complex than what can easily fit into a standard two-hour film. Classical Hollywood narrative, with its emphasis on goal-orientation and clearly motivated, causally linked events, tends to nudge screenwriters away from the sprawl more often found in novels or television miniseries. In the case of Trumbo, screenwriter John McNamara likely opted for the virtues of clarity and concision. He concentrated only on those incidents that directly involved the titular character, eliminating or minimizing anything that would detract from that narrative focus.

That being said, the creative choices of McNamara and director Jay Roach are, above all, choices. The screenplay for Bridge of Spies, for example, manages to convey something of the complex bilateral negotiations that linked the downing of U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers with the seemingly unrelated espionage case of KGB officer Rudolf Abel. One could imagine Roach and McNamara devising very brief scenes of Wilson, Foreman, and Young in their Academy imbroglios. Or alternatively, the film might have included Trumbo’s voiceover reading the text of his actual letters to Wilson, many of which commented on the perpetually changing conditions of the black market. As before, the inclusion of such material wouldn’t necessarily make Trumbo a better film. But it would make it a different one.

Although Dalton Trumbo led the fight against the blacklist, often using the industry’s greed, hypocrisy, and mendacity against itself in the process, my brief synopses of these other screenwriters’ Academy Award travails show that he was not alone. Many individuals taking small incremental actions led to the blacklist’s end. It wasn’t smashed; it crumbled through erosion. The fact that one of Hollywood’s “untouchables” was able to openly accept a major industry award made open screen credit a logical next step. Dalton Trumbo happened to be the lucky individual to regain his name without having to bow and scrape before HUAC. But even he knew it could just as easily have been Nedrick Young. Or Michael Wilson. Or Albert Maltz.

Come Oscar night on February 28th, if Bryan Cranston is lucky enough to hoist the Best Actor prize above his head, it will be a fitting tribute to a man whose struggles with this same institution helped to define him and his era. Yet an Oscar victory would also pay tribute to all those whose stories have not reached the screen, but whose grit and determination made Trumbo’s triumph possible. And Mr. Cranston, if you get to deliver that acceptance speech, be sure to remember all those unsung heroes that joined Trumbo in the fight.

Trumbo is based on Bruce Cook’s biography, which was first published in 1977. Readers should also check out Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo’s massive, exhaustively researched new biography, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical. Ceplair is also the co-author, with Steven Englund, of the standard work on the Hollywood blacklist itself, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics and the Film Community, 1930-1960. My book, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds, also considers Trumbo’s contribution to Spartacus.

Trumbo’s collection of correspondence, speeches, business papers, scripts, and photographs is held at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. A rich sampling of material from it is available here. Several of the photos in this entry come from the WCFTR collection. Go here to listen to excerpts from his HUAC testimony.

Excerpts from John Rankin’s infamous speech about Jewish actors in Hollywood can be found in Gordon Kahn’s Hollywood on Trial: The Story of the Ten Who Were Indicted. Trumbo himself commented on the role of anti-Semitism in HUAC’S investigations in The Time of the Toad: A Study in Inquisition in America.

Franklin Leonard interviewed John McNamara last November about his work on Trumbo for his Black List Table Reads podcast. Nicolas Rapold offers a useful guide to the individuals profiled in Trumbo, including its composite characters. If you’re interested, you can see actual footage of the announcements of various screenwriting awards at the Oscar ceremonies of 1957, 1958, and 1959.

For more on how adaptation works, see the thirteenth chapter of the new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming next week. That chapter is available for courses as an add-on to both the printed edition and the McGraw-Hill electronic edition.

Trumbo.

They see dead people

DB here:

Continuity editing was one of the great collective inventions of filmmakers. In the ten years after it crystallized in Hollywood around 1917, it was adopted around the world. The technique has hung on a surprisingly long time, rather like geometrical perspective in pictorial art. It’s so powerful that it’s hard to escape.

It’s powerful partly because it’s adaptable to a lot of narrative situations. It provides filmmakers what we can call a set of stylistic schemas, or routine patterns, that can be adjusted in various ways. Analytical cuts that take us into or back from the action, shot/reverse shots and eyeline matches, over-the-shoulder framings (OTS), and slight camera movements that set up reestablishing shots: these straightforward schemas can be used in an indefinitely large number of ways.

I‘ve been noticing this flexibility while writing (still!) my book on narrative strategies in 1940s Hollywood. In particular, I was looking at fantasy tales and the peculiar problems they pose for filmmakers. First, how do we represent ghosts, angels, and other visitors from the Afterlife? And how do we make sure that audiences understand that what we see isn’t necessarily what some of the characters onscreen are seeing?

Angels unawares

Our Town (1940).

On the first problem: Today we have CGI resources that allow Afterlifers to move freely among the living characters. These effects were much harder to achieve back then. The supernatural-fantasy genre developed its own conventions (yep, schemas). Most films resorted to presenting the Afterlifer in double exposure.

But superimposed characters can’t move easily among the clutter of furniture in a set. A supered ghost can’t go behind a sofa; the sofa will always be visible through it. You might resort to a traveling matte shot, as William Cameron Menzies did in Our Town (1940), when Emily revisits her family after her death. The shot (just above) is particularly flashy because the younger Emily is also in it.

Or you could pull off the remarkable trick in Earthbound (1940). Here a ghostly Warner Baxter settles comfortably into the middle ground and strides around behind furniture and other actors.

He can even give up his seat to an old lady and shift to another.

These effects were achieved by a technical feat that I don’t fully understand. (See the codicil.) But the trick wasn’t widely adopted, and most filmmakers opted for a simple expedient. Typically the Afterlifer shows up as a superimposition, but he or she gradually materializes and becomes a solid presence like all the other actors. This is from The Canterville Ghost (1945).

Then comes the second problem. Sometimes the living can see the spectre, but sometimes not. In Here Comes Mr. Jordan, the angel Jordan and Joe the prizefighter arrive from the Beyond and watch the murderous couple from behind. They aren’t visible to the living, but they’re just as tangible.

If a living character seems oblivious to the otherworldly guest, we’re to assume that the guest is invisible. Each film has to inform us of who can see what, and most films do—redundantly. The spook or divine messenger will explain that the living can’t see them, or that only certain characters can. (Sometimes children and animals can see them while grownup humans can’t.)