Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101

Premium Rush (David Koepp, 2012).

DB here:

After nine years, over 700 entries, and many essays and other stuff, this contraption of a website has started to intimidate us.

If we’re intimidated, you might be flabbergasted. Although a set of categories sits on the right to guide your exploration of this tangled databank, those too loom large and discouraging. So we’ve decided to tidy up by–how else?–adding another entry.

We’ll occasionally offer a stripped-down guide to our writing on certain topics. We’ll steer you to entries that we think represent the core of our thinking on a problem, and then add some that probe more deeply, for those who want to go beyond the basics. Since one of our areas is narrative theory and analysis, a good first effort, we thought, would be to produce a sort of DIY syllabus that systematically surveys the topic as we’ve explored it. And since we’ve often written about classical Hollywood storytelling, and since many of our readers are interested in that…well, the syllabus sort of wrote itself.

We call these ideas open secrets of storytelling because by and large they aren’t acknowledged in the screenplay manuals that aspiring writers read. In most cases, we’ve had to devise our own concepts and terms, based on watching hundreds of movies. Yet these observations are wide open, available in our books and on this site.

Now comes our chance to pull them together. The result isn’t an utterly comprehensive theory of classical Hollywood narrative, but it does give a fair sampling of the range of questions we’ve tried to answer about it. The topics, linked to essays and blog entries, are arranged in three layers.

The most basic layer is an array of key ideas about story worlds, plot structures, and strategies of narration. These ideas are introduced in the first entry, “Understanding film narrative: The trailer.” Discussions of other basic concepts follow. Just reading the entries pegged to those topics, you could get a solid sense of what we’re aiming at. For most of those, we also propose a film you might view to test how the ideas work.

At a second level, for some topics we include some entries that dig deeper. They’re either more complex and advanced, or they provide some historical background.

Finally, after we’ve reviewed the key topics, we add a batch of case studies that use several of the tools we’ve laid out. These are usually very deep dives into particular films. They aim to show how the analytical ideas can bring out distinctive features of particular movies. The case studies are pretty wide-ranging, but they tend to hover around specific problems, such as adaptation or the creation of fantasy worlds.

How could you use this resource? A teacher in high school or college could draw on it as a partial syllabus or just a thumbnail list of supplementary material for a course. Teachers using Film Art: An Introduction could treat it as a supplement to our section of Chapter 3 on classical narrative. Or a student might find an idea for a paper in this vicinity.

Since we’ve always tried to link film studies and filmmaking, we hope that practitioners might be interested too. For example, an aspiring screenwriter could take this as a weekly reading/viewing agenda, treating it as a free course in story analysis. General readers who simply want to know more about the mechanics of cinematic storytelling should find something provocative here too. For everybody: Feel free to use it as Narrative Analysis 101.

We thank our many loyal readers of this blog, as well as the many more who have just dropped by once or twice. Your continued interest has helped us keep going.

Open Secrets of Hollywood Storytelling

The basics

Understanding film narrative: The trailer. Suggested viewing: The Wolf of Wall Street.

Advanced: Three Dimensions of Film Narrative: Narration, plot structure, and story worlds. Suggested viewings: The Godfather, Jezebel.

Advanced: Stories beget stories. Suggested viewing: American Hustle.

Actions and agents

Introduction to classical plot structure. Suggested viewing: Many possibilities listed.

Historical background: Is there a 3-act structure?

Action films: Did spectacle kill classical plotting? Suggested viewing: Mission: Impossible 3.

Advanced: Block construction. Suggested viewing: Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction.

How many protagonists? Suggested viewing: The Big Short.

The importance of coincidence. Suggested viewing: Serendipity.

Narrative parallels among characters and periods. Suggested viewing: Julie and Julia, Enchantment.

Advanced: Fine-grained parallels between scenes. Suggested viewing: The Prestige.

Time shifts: How flashbacks work. Suggested viewing: The Power and the Glory.

Advanced: Time shifts without flashbacks. Suggested viewing: Exodus.

Advanced: Nested flashbacks. Suggested viewing: Passage to Marseille, The Locket.

Historical background: Flashbacks and plot problems. Suggested viewing: The Great Moment, All about Eve.

Replays. Suggested viewing: Mildred Pierce.

Advanced: The auditory replay. Suggested viewing: Sudden Fear.

Network narratives. Suggested viewing: Grand Hotel.

Forking-path plotting. Suggested viewing: Source Code.

Advanced: Film Futures. Suggested viewing: Sliding Doors.

Historical background: What-if narratives. Suggested viewing: Dangerous Corner

Beginnings and endings: Molly Wanted More. Suggested viewing: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Silence of the Lambs.

Telling more or less

Visual storytelling. Suggested viewing: Mission: Impossible.

The hook between scenes. Suggested viewing: Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler; National Treasure.

Narration: omniscient versus restricted. Suggested viewing: Cloverfield.

Historical background: Hitchcock, suspense, and surprise.

Alignment and allegiance. Suggested viewing: House by the River.

Character subjectivity, optical and mental. Suggested viewing: The Silence of the Lambs.

Historical background: Subjectivity and sound. Suggested viewing: Nightmare Alley, The Fallen Sparrow.

Voice-over narration. Suggested viewing: All about Eve.

Advanced: Dead narrators. Suggested viewing: Laura, Confidence.

Historical background: Inner monologue. Suggested viewing: Strange Interlude.

Case studies in narrative analysis

These are exercises in film criticism that utilize several of the tools laid out above.

Boyhood and Harry Potter: The actors’ lives as part of the narrative.

Eastern Promises: Thematic echoes in an auteur’s narratives.

Gone Girl: Suspense and thriller conventions in fiction and film.

Gravity: Narrative innovation within mainstream cinema.

Inception: Goals and parallel construction; managing multiple plotlines.

Moonrise Kingdom: How to make a modern fairy tale (with some help from merchandising); furnishing alternative worlds.

Premium Rush: How goals and deadlines create tight construction.

Side Effects and Safe Haven: Fragmentary flashbacks and patterns of suspense.

Slumdog Millionaire: Adapting a novel to classical norms.

The Bourne Ultimatum: Plotting across franchise installments.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer: Classical structure in genre fiction.

The Hobbit: Adaptation and length; adaptation and change.

The Magnificent Ambersons: How to manipulate time without flashbacks.

The Prestige: Using sound to enrich flashback construction.

The Walk: Each act a different genre.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: Elliptical narration: The viewer’s responsibility.

As we write more entries relevant to narrative, we’ll revisit this DIY syllabus.

Needless to say, we consider these matters more closely in several of our books. See The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, by Kristin, Janet Staiger, and me, and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. For my part, there’s Narration in the Fiction Film and The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. I’m at work on a book on narrative innovations in 1940s Hollywood, the central source of much that we encounter in today’s films.

Pick your protagonist(s)

Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015).

DB here:

We’re used to sorting movies by periods, genres, and the individuals associated with them (stars and directors especially). But we can also distinguish films by their styles and narrative forms. So there’s not only a “film noir” style but other group styles, like the tableau approach seen in the silent cinema, or the deep-focus one of Hollywood in the 1940s-1950s. Similarly, we can think about types of storytelling strategies.

Someone might object that at least genre and other categories are in filmmakers’ minds, whereas it’s unlikely that any American in the 1940s set out to make a film noir as we understand it. (That term, and category, came from France, and somewhat after the fact.) Similarly, Ford probably didn’t think he was making a “classically constructed” Western in My Darling Clementine; he was just making a Western.

One reason we might construct these categories is to bring out the principles that filmmakers seem to follow intuitively. Perhaps no screenwriter ever thought explicitly about scene hooks, but the device is common enough to suggest that they believed the device was a useful tool.

Besides bringing out the regularities of filmmakers’ craft in certain times and places, constructing categories allows us to understand the creative choices they face. Maybe you handle a scene in a two-shot or in several reverse-angled singles. Both are permitted, each has certain advantages, and filmmakers spontaneously choose among these alternatives.

In effect, we’re reconstructing the menu of options available to filmmakers in certain times and places. If we do it carefully, we gain understanding of what each option can yield, and what certain filmmakers can achieve if they try something new.

Kristin and I have been in this game for decades, and our work on norms of film form and style has surfaced in our books, lectures, and blog entries. One set of analytical categories we’ve proposed is based on how movies use their protagonists. I was struck by how many films at end of 2015 and the start of 2016 illustrate a range of options currently available.

It turns out that these options are of long standing; they’re another example of how even recent movies owe a lot to the classical Hollywood tradition. That’s not to say, though, that they might not revise or tweak that tradition. Some filmmakers are innovative by temperament, and besides, there are career rewards when innovations come off. (Just ask the maker of Pulp Fiction.)

The categories depend on determining which character(s) can function as protagonist(s). That depends on the goals, the obstacles to the goals, and the relationship between the goal-striving character and other characters and story lines. Traditionally, in a two-hour Hollywood feature, a principal goal is articulated in the first half-hour or so. Kristin has argued that after this “Setup” portion comes others: a “Complicating Action” (also lasting about half an hour) that changes the goal and in effect creates a new setup; a “Development” which consists of delays, backstory, and fresh obstacles to the goal; a climax that resolves the issue; and an epilogue (screenwriters called it a “tag”) that confirms a certain stability in the situation. The major parts roughly divide the film into quarters, contrary to three-act accounts.

So today I look over the protagonist menu, based on some current offerings. Of course there are spoilers.

One, with benefits

Daddy’s Home.

Take as a baseline the movie organized around one protagonist. A clear example from this holiday season is Daddy’s Home. Stepdad Brad (Will Ferrell) has read all the touchy-feely parenting books and applies their lessons to raising the kids he has inherited by marrying Sara. But Dusty (Mark Wahlberg), Sara’s charming and macho ex, returns from his mysterious life in espionage and rapidly takes over the household. In an escalating series of mishaps, Brad proves unable to live up to the hip and edgy things that Dusty dreams up for the kids.

The climax comes when Brad, after showering Megan and Dylan with presents, gets drunk at a basketball game and humiliates them all with a public confession of inadequacy and a pair of unguided free throws. Eventually the battle of the two parenting styles—comforting versus edgy—is resolved when at a father/daughter dance Ward’s nonviolent, somewhat goofy, approach to conflict tamps down an explosive confrontation with a father spoiling for a fight.

The classic situation is established: our protagonist has an antagonist. Dusty is an infighter who seizes control of every situation. As you’d expect, Dusty is winning the race for the kids’ affection during most of the film; even Sara seems to be feeling some of her old attraction to him. As the antagonist, Dusty makes his intentions clear about two-thirds through the film: He will not give in. This precipitates Brad’s suicidally expensive efforts to shower his kids with presents. Deeply shamed, he moves out. Dusty seems to have won.

But Dusty has a weakness. He can’t manage the drab daily responsibilities of parenting—making the kids’ lunches, driving them to school—that Brad enjoys shouldering. At the climax, Dusty has gained respect for Brad and soon remarries, becoming the devoted father of a stepchild. In a traditional comic reversal, he must confront the kid’s birth father, who is a bigger thug than he ever was.

Daddy’s Home reinforces our alignment with the protagonist Ward through his voice-over narration, though at the end the integration of the two families is given by letting Dusty and Sara chime in too. The emphasis on Ward, his confrontations with Dusty and his kids, and the hilariously bad advice offered by Ward’s boss (a classic sidekick role) fulfill a common template for one kind of classical plotting. The protagonist comes to the plot with his goal already decided on, and he has to defend it against a tangible threat.

There’s another option: letting the protagonist discover the goal in the setup. And there’s the possibility of presenting not a single powerful antagonist like Dusty but several. These forces in various ways take on the task of blocking the protagonist’s goal.

Some critics have thought David O. Russell’s Joy somewhat messy, but I think that’s partly because the film spreads the antagonist function across many vivid secondary characters. In my view, as Bernie Sanders might say, the plot remains pretty classical.

The Setup establishes Joy’s life as a disaster. Her childhood dreams of creativity have been forgotten after years with her dysfunctional family and the demands of her children and job. Around the half-hour mark, Joy’s wounds from cleaning up a broken wine glass send her into a dream in which she rebukes herself for her passive life. She wakes up and starts designing a miraculous mop. If her initial goal was simply muddling through, her new goal revolves around transforming her life by creating and marketing this product. This new goal sets the key for the Complicating Action.

At the film’s midpoint, Joy convinces the producer overseeing the Quality Value Channel to add her mop to the offerings. The Development section consists of more obstacles and some triumphs, so that eventually sales take off. But her family butts into her business and plunges her into bankruptcy. This, her darkest moment, is overcome when she confronts her Texan partner and threatens to take him to court for the fraud she has discovered. She pays off her debts. In the epilogue, we see her as a successful businesswoman helping other struggling inventors.

This, of course, is just the film’s spine. In the course of this plot, Joy discovers she has reserves of courage, determination, and a sense of her own worth. Weaving through it all is the voice-over narration of her grandmother who not only fills in information for us (even from beyond the grave) but also serves as a prod for Joy to persist in her desire to make things of value. There’s also a clever opening showing a soap-opera performance in the manner of Straub/Huillet; it’s later replayed in normal TV terms.

Joy has allies—her ex-husband and a loyal friend—but she faces many antagonists, an array of family and predatory business people. Where Joy most alters the traditional plot layout, I think, is in its refusal to include a story line involving romance.

Most Hollywood plots are double-stranded: a line of action about romantic love, and another line, usually about work. Joy doesn’t revive her marriage and instead concentrates on her fulfillment of her dream. Having seen Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle, we might expect Joy (played by Jennifer Lawrence) to hook up with the QVC producer played by Bradley Cooper, but it doesn’t happen. Still, Joy remains a nice example of the plot focused on one protagonist who struggles against a range of antagonists, each contributing particular obstacles. A comparable example from recent releases would be Bridge of Spies.

It takes two

Carol.

Alternatively, there’s the dual-protagonist plot. Two characters share a goal, or have complementary ones, and they work together. They may also come into conflict about it or about other matters. Often they’re a male/female romantic pair, as in the classic His Girl Friday, but they may also be male/male (The Other Guys) or female/female (The Heat). I’m told that Star Wars: The Force Awakens eventually settles into a dual-protagonist plot, but one example I’ve seen is Sisters.

At the start our protagonists are characterized as unhappy and incomplete. Maura (Amy Poehler), a divorcée, is oversolicitous and lonely; Kate (Tina Fey), a single mother, is irresponsible and frequently jobless. Neither sets out deliberately to improve her life, but they are put out on that path after learning that their parents have sold the family home. Screenplay manuals call this the “inciting incident.”

An encounter with the house’s snobbish purchasers convince the sisters to relive their wild high school days by inviting their old classmates to a wide-open party. They switch roles: Maura vows to become the wild girl she always hoped to be, and Kate agrees to become, for that night, the prudent one keeping an eye on things. At first the party is a boring affair, as their Gen-Xer friends have become staid parents, but at the midpoint, with the arrival of some serious drugs and a tattooed side of beef named Pazuzu, things explode.

The Development section is woven out of running gags, including a would-be party animal, a mean-girl rival crashing the event, a hunk attracted to Maura, and Kate’s efforts to keep in cellphone communication with her daughter Haley, who has nothing but disdain for her scatterbrained mom. The climax is precipitated when, having utterly trashed the house, Kate learns that actually she was to get the money from the sale. More seriously, Maura has secretly acted as a surrogate parent for the elusive Haley. The denouement presents a series of resolutions whereby the parents forgive their daughters, the house is rehabbed, and the sisters accept the need to sell the place and grow up. A tag shows the family united at—when else?—Christmas.

In Sisters, the intertwined lines of action yield goals around one the house-based line of action (preserving the house, trashing it, rehabbing it), but other goals emerge around love. Maura gets a boyfriend, Kate wins her daughter’s love, and both reconcile with their parents.

Sisters exemplifies how dual-protagonist films can show characters sharing a goal and still clashing with one another. Here, as in most such films, one of the pair may help the other, work against the other, or keep the other in the dark. Accordingly, so that we can appreciate all the schemes, misunderstandings, and screw-ups, dual-protagonist films tend to supply a wide range of knowledge. In Sisters, for instance, we know, as Maura and Haley and the parents do not, that Kate has lied about getting a new job.

By contrast, a single-protagonist film can restrict our knowledge to the hero or heroine, so that we share the suspense and surprise coming their way. Daddy’s Home restricts us almost completely to what Ward knows; Dusty is constantly surprising him with new subterfuges to win the kids’ love. Similarly, Joy is the center of consciousness in her film. True, we have the Grandmother’s voice-over supplying information, but it doesn’t really break with Joy’s range of knowledge. Grandma could have tipped us off early that about the Texan’s scam, but we learn of it only when Joy does.

In this way, plot structure interacts with what in literature is called point of view, or narration in the broad sense. Carol provides a striking example.

Patricia Highsmith’s original novel presents a single-protagonist plot. Therese, vaguely dissatisfied with the men in her down-at-heel bohemian milieu, falls abruptly in love with a wealthy wife and mother. Highsmith rigorously retains our attachment to Therese, so that we never know more than she does. She gets glimpses of Carol’s unhappy life with her husband Harge, her love for her daughter Riddy, and her struggle to obtain a divorce that will let her share custody of the girl. After Therese and Carol’s compromising road trip to Middle America, Carol returns to New York and the legal proceedings Harge is conducting. He has proof of Carol’s lesbian affair and intends to use it against her. But Therese learns of the progress of the case through letters and phone calls. Several chapters showing Therese simply waiting in Sioux Falls for news furnish some of the dread-filled suspense that Highsmith would generate in her crime novels.

The film displays the traditional four-part structure. The drive west is launched at the midpoint, just when Therese’s boyfriend Richard denounces her as infatuated with Carol. The couple’s trip, trailed by a detective tape-recording their lovemaking, serves as the Development. Interestingly, the book has a similar array of incidents, with the same plot point serving as the pivot to the second half. As I’ve argued before, popular fiction sometimes displays the same plot architecture we find in cinema.

But just following the four-part template doesn’t mean that the film and the novel are congruent. Carol shows how choices about narration can reshape plot structure. Apart from some changes in the original situation (e.g., Therese is now an amateur photographer rather than a set designer for stage productions), screenwriters Phyllis Nagy and Todd Haynes have made a crucial decision. They have expanding our access to Carol’s story line.

Events that are “off-page” in the novel are fully dramatized in the film, and we witness action that Therese never learns of. Harge, a vaguely pathetic presence in the book, is more fully characterized, and as an angry patriarch at that. We get scenes of Carol with Riddy, with her former lover Abby, with her in-laws, and particularly with her lawyer, who’s helping her fight for custody. Crucially, the screenplay supplies a climactic scene not in the book, when Carol yields to Harge’s demands and refuses to condemn her affair with Therese. Something like this must have occurred in the book too, but it’s presented sketchily and at a remove, recounted to Therese by Carol and Abby.

By creating a wider-ranging narration, Carol turns a single-protagonist book into a dual-protagonist film. The two women share the same goal, romantic union, and the narrational patterns balance their individual efforts to achieve it.

But wait, someone might say. Nagy and Haynes have added a flashback structure to the book, triggered by the early scene showing Therese leaving Carol after their meeting at tea. We watch Therese go to a party in a cab, and her morose face behind the rain-streaked window suggests that she’s recalling how she met Carol. Doesn’t this device respect the restricted narration of the book?

Actually, no. In classically constructed films, extended flashback passages are seldom restricted to the character doing the remembering. Against all realism, flashbacks include material that the recollecting character doesn’t or couldn’t witness. In line with this convention, Therese’s flashback includes a lot of scenes she doesn’t know about. The memory-flashback’s main purpose in a Hollywood film isn’t to represent character memory but to justify shifting the order of events. There’s more discussion here.

Perhaps one aim in showing rather than telling Carol’s story was to give Cate Blanchett a bigger part, but it has an important function for us as viewers. It avoids a climax portion that would show, almost Bresson-style, Therese simply killing time and waiting. Instead, by being transported to Manhattan and seeing what Carol is struggling against, we can appreciate Carol’s profound sacrifice for Therese. Carol is a somewhat remote and mysterious character in the book, but she’s delineated far more precisely in the film, largely because of these scenes.

Because Carol’s story line is fleshed out, we have a stronger sense of Therese’s mistake when, returning to New York, she declines Carol’s offer to resume their affair. (In the book, other factors shape Therese’s choice, including an ominous portrait that she seems to recognize from her childhood.) We know Carol to be more courageous than Therese believes she is, which makes the young woman’s decision not to reignite their affair more regrettable. This choice doesn’t block the screenplay from offering, when the flashback has ended and looped back to the present, a modified form of the book’s somewhat hopeful conclusion.

Multiple choices: Men (and women) on a mission

Spotlight.

There can be more than two protagonists, of course, so it’s convenient to have the general category of multiple-protagonist films too. Two common sorts show up in our year-end Hollywood releases.

One is what we might call the mission-team movie. Again, goals define the options. A group of characters, all more or less equal in importance, devote themselves to achieving a single goal. This is a common feature of combat films, though we find it in peacetime too. Classic examples are heist films like The Asphalt Jungle, sports films like A League of Their Own, crime films like Johnnie To’s The Mission, and numberless road-trip films.

Spotlight exemplifies the mission-team plot. As in a combat film, there’s a hierarchy: the chain of command runs from publisher to editor in chief to managing editor to section editor, and then to the grunts. The Boston Globe’s new editor Marty Baron puts an investigative team, called Spotlight, on a story about pedophile priests. Three reporters under Robby Robinson (Michael Keaton) unravel a story that ultimately implicates nearly a hundred priests and reveals many more victims.

As in a heist film, each reporter is given a specialty. Mike Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) concentrates on getting information from the no-nonsense lawyer who is suing the Church on behalf of dozens of victims. Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy) scans the record and discovers a telltale pattern of priests’ assignment to parishes. Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams) focuses on finding and interviewing victims. Robby runs interference with their superior Ben Bradlee Jr. and pursues his own hunches, including the role played by a retired attorney who’s one of his golfing buddies.

Through our old friend crosscutting, each protagonist is given separate scenes in which their skills are revealed and new information emerges. What’s common to the team members is tenacity and dedication to work (they put in long days and weekends). In addition, all were raised Catholic and feel with greater force the ways in which lawyers and the Church have covered up these crimes. In particular, the interpersonal style of Sacha, warm and empathetic, is contrasted with that of Mike, who tends to be more truculent and easily provoked.

The progress of the investigation falls neatly into the four-part structure, bracketed by a prologue (a 1976 incident in which a priest’s crime is covered up) and an epilogue that celebrates the success of the project and reminds the audience of the ongoing problem with priestly pedophilia. In the Setup, the reporters believe that the story is fairly limited until the spokesman for a victims’ organization provides them some evidence of wider criminality.

The Complicating Action consists of the discovery of over a dozen pedophiles, which raises the prospect of many more. Robby also senses a deep story here, based on the conspiracy of silence he’s confronting in the Church’s social circle. A complicating action often resets the initial goal, and this one does just that. Now Baron tasks the team with not merely exposing individual priests, but showing that the Church officials knew of the crimes, covered them up, and created a mechanism for perpetuating them.

The Development uses the paper trail discovered by Matt to pinpoint likely offenders, so now the team seeks out priests rather than victims. More obstacles pile up, including the unwillingness of victims to testify and the 9/11 attack, which slows the release of the story. All the while, the Spotlight team has been waiting for a court decision to unseal crucial documents that would prove the Church’s full knowledge of events. Mike learns that the lawyer Garabedian has used a counter-suit to bring some of those documents to light, but they are mysteriously missing from the court archives.

Delay, a common feature of Development sections, stretches things out. Finally Mike finds the court documents and they support the story. The climax consists of the team deciding on when to reveal the story so as to maintain their scoop and, to seal the deal, Robby getting his attorney friend to confirm their list of names. As in All the President’s Men, the press has to be characterized as taking every opportunity to back up its exposé with an abundance of evidence. The epilogue shows the Spotlight team, back at work on a Sunday, fielding phone calls from yet other victims—and Robby feeling contrite because back in 1993, he could have followed up a lead and did not. Again, the effort is to portray the press as both idealistic and fallible.

I said that the characters in a mission-team plot are “more or less equal in importance” because we often find that some are more prominent than others—they become “first among equals.” You could argue that the Ocean’s Double-Digit films, though dependent on teamwork, give primary emphasis to Danny, Rusty, and Linus. Still, there’s considerable time spent on the secondary members of the team, and often they turn out to be more central to the main action than they might appear. In Spotlight, the characters Robby, Mike, and Sacha are the most prominent (given the stars, no surprise), with Matt getting slightly less screen time and featuring in fewer dramatic confrontations. As we’d expect, though, Matt plays a crucial role in advancing the mission. The editor Baron, also downplayed compared to the others, not only launches the investigation but also serves as the wise leader who guides their strategy.

Again, the double line of action is less visible here. Mission-team plots often eliminate romance (combat films again) or introduce some love interest when a spouse or lover finds a protagonist too dedicated to the mission, or when the romance is part of the mission (as in Ocean’s Eleven and Twelve). Here there’s a hint that Mike’s dedication to investigative reporting has led to separation from his wife, but those circumstances aren’t worked out to create a love-related story line. It’s as if the journalistic crusade is proceeding on enough fronts not to need distracting subplots.

It’s the end of capitalism

The Big Short.

If the mission-team movie is characterized by a rigorous focus on the group’s common goal, another sort of multiple-protagonist movie is more diffuse and tangled. I’ve called it a network narrative. It features several more or less equal protagonists pursuing different goals, but connected through kinship, friendship, employment, or coincidence in ways that affect their individual fates. The film aims to trace out the links and nodes in the network, all the while pushing forward to create new connections.

Nashville, Pulp Fiction, and TV series like The Wire exemplify this method of construction, but these sprawling networks are only one option. The groups linked can be more limited. Consider The Big Short (based on a book that’s itself a network narrative).

When the film starts, you might think that the awkward hedge-fund manager Michael Burry (Christian Bale) is the protagonist. In the first ten minutes he cryptically outlines his hypothesis that the US mortgage system is fundamentally flawed, and he formulates a plan to exploit it. But then the narration switches to Mark Baum, a hedge-fund manager deeply critical of the banking system.

For several minutes, the narration alternates scenes of each man’s activities, with an emphasis on Burry’s plan to bet against housing bonds and Baum’s inability to come to terms with his brother’s suicide. At the 25-minute mark, Baum’s team gets a misdirected call from stock trader Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) and they learn from him that Vennett’s bank is selling collateralized debt obligations.

Through a vivid demonstration with building blocks, Vennett illustrates how the rating agencies have overvalued poor housing risks.

The Complicating Action starts by introducing two more protagonists, Charlie Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Wittrock), who run a small investment company. By chance they find Jared’s presentation and decide to check out its strategy of shorting the housing market. Aided by the retired banker Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt), they get the credentials to buy in.

Their efforts are intercut with Burry’s tracking the market and with Baum’s team visiting Florida, where they discover that indeed house values are under water and mortgage brokers are snapping up unqualified buyers en masse. And the men learn that the rating agencies are routinely lying about the quality of the packages on the market. In the meantime, as mortgage defaults grow, mortgage bonds puzzlingly rise in assigned value.

The next turning point, launching the Development, is triggered by the decision of several protagonists to visit a Los Vegas forum on securitization. Baum’s team is instructed by Vennett to simply watch, and they learn about CDOs, though Baum can’t resist challenging the complacency of the banksters he meets. Meanwhile, guided by Rickert, the inexperienced Geller and Shipley hit on a new angle: to bet upon not just the low-rated packages but the A and AA ones. The men leave Vegas convinced that the market will collapse. Soon, though, we get the ups and downs characteristic of a Development, as it seems that our protagonists are all going to lose their shirts.

But their efforts to bet against the US economy pay off when mortgage companies start failing. This initiates the climax. The banks and investment houses struggle to contain the damage, chiefly by shifting the losses to their customers, and soon everyone wants the default swaps our protagonists have bought so cheaply. All wind up rich but disillusioned with the system. As in Spotlight, The Big Short’s epilogue concludes with texts indicating what happened to the protagonists afterward, and hinting that the system could topple once more.

You could imagine The Big Short as a different film, focused around one protagonist and making the others helpers, rivals, or walk-ons. But as a network narrative, it suggests the sheer sweep of financial corruption, as well as a range of response to it, from cynical acceptance (Vennett) to boiling outrage (Baum).

What enlivens the film, and makes it look and feel quite different from Spotlight, is its narrational texture. First, it’s recounted in voice-over by the least emphasized character, Vennett. Second, the film allows characters to address the camera occasionally, like Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street, and they sometimes explain that what we’re seeing in the film wasn’t exactly what happened in real life (below left). Third, there are capsule sequences in which unlikely experts like Margot Robbie and Anthony Bourdain explain esoteric financial concepts.

One insert comes from Selena Gomez and economist Richard Thaler. (Get his fine book Misbehaving!)

Throughout, the dramatic scenes are interrupted by flash montages of musical numbers, TV commercials, and glimpses of cheerleaders, overpriced houses, and people living under bridges. This gonzo style, reminiscent of the fragmentary montages of Oliver Stone’s JFK and Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, matches the “glum exuberance” of the heroes. They’re simultaneously pumped and appalled. Like the reporters in Spotlight, they keep thinking they’ve hit the bottom of the cesspool only to learn that it’s muck all the way down. This style extends the cross-sectional aspect of the protagonists’ network by suggesting the ripple effects of the subprime crisis.

There are other classical narrative models on display in recent releases. Steve Jobs is a single-protagonist film, but one rendered through block construction. The Hateful Eight seems to me a network narrative in the Grand Hotel mold: several major characters, with initially unrelated goals, converge on a limited space. There conflicts and alliances develop. In addition, more nodes and links in the network are revealed through a flashback. One pattern I haven’t seen this season is what Kristin calls the parallel-protagonist plot, as in The Hunt for Red October and Amadeus. Here two characters with different goals come to learn of one another, chiefly because one becomes fascinated with the counterpart.

I offer these sketches in a descriptive, analytical spirit. Nothing in what I’ve said indicates whether the movies are good or bad. This is like analyzing a fugue or a sonnet: the form is more or less fixed, but each work will handle it somewhat differently. Some will handle it skillfully, some not. And a fuller analysis of even the weakest of these films would show how the classical format encourages filmmakers to devise parallel scenes to show character change (such as the tea-time meeting in Carol), find motifs that develop and pay off (like Mike Burry’s increasingly maniacal drumming), and create call-backs to details that seemed unimportant earlier but that take on bigger roles in the action later (like the dance-fight in Daddy’s Home). It’s also pretty remarkable that the four-part format can be adapted to different roles for protagonists.

What advantages flow from sorting films by narrative strategy instead of by genre or director or period? We can see unexpected continuities between current filmmaking and older traditions. We can show how different principles of plot architecture allow different opportunities for characterization and thematic implication. We can trace how commitment to one sort of plot can open up further choices about point of view and other narrational matters. And once we’ve detected the basic similarity between certain storytelling strategies, we can go on to appreciate the differences film by film.

This is a project in what I’ve called the poetics of cinema. You can learn more about it in the book of that title. A chapter from the book, on the theory of film narrative I propose, is on this site, and there’s a blog entry introducing it. In each of these I consider three major dimensions of cinematic storytelling: narration, plot structure, and the story world. Today’s entry suggests that one feature of the story world, the protagonist, can be shaped by a tradition of plot structure and some features of narration.

For more on the four-part model of plot structure, see Kristin’s entry “Time Goes by turns” and her book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood. I’ve offered some analyses along these lines as well, in for instance “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” “Gone Grrrl,” and “Birdman: Following Riggan’s orders.” I discuss network narratives briefly in this entry and at length (no surprise) in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema.

Naturally, thinking about protagonists and plot structure isn’t the only way we can analyze movie storytelling. For other tools, see the category Narrative strategies.

Daddy’s Home (Sean Anders, 2015).

THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth

DB here:

By now everybody knows that Tarantino’s forthcoming The Hateful Eight was shot on film in the Ultra Panavision 70 format. This anamorphic widescreen process yields a projected aspect ratio of 2.76–in a word, humongous. An early version of it, MGM Camera 65, was employed on Ben-Hur (1959), but Panavision quickly developed a new generation of cameras and renamed the process. It wasn’t heavily used; supposedly Khartoum (1966) was the last film shot in the format.

The process by which Tarantino, ace cinematographer Robert Richardson, and the enthusiastic boffins at Panavision revived Ultra Panavision 70 is detailed in the current American Cinematographer (alas, not yet online). The production is an extraordinary tale. But what about exhibition? Luckily, the widescreen fans among us can glean a lot about that from veteran projectionist Paul Rayton’s interview with Chapin Cutler, co-owner of Boston Light & Sound. It was the task of Chapin and his team to find over 100 projectors, refurbish them, test them, and set them up in theatres all over America.

Chapin is a legendary figure in movie exhibition. Trained as a projectionist during his college years, he and Larry Shaw have made BL&S one of the very top companies for installation and maintenance of theatre projection equipment. He has supervised theatrical setups at festivals (Sundance, Telluride, TCM), industry gatherings (CinemaCon), and at some of the world’s top-notch theatres.

He’s more than a professional’s professional: He loves film and prides himself on delivering a powerhouse show. He was a natural choice for a movie geek like Tarantino to arrange the roadshow screenings of The Hateful Eight.

Chapin has discussed the nearly military precision necessary to fulfill Tarantino’s mandate in The New York Times and The Boston Globe. You should read these pieces for essential background. When Chapin added some new information courtesy of the listserv of the Art House Convergence, I jumped at the chance to include you in the audience. I know that many of our readers are keen to devour whatever they can learn about this film, one of the year’s major American releases.

So here are Chapin’s notes on how you prepare and ship out 100+ 70mm film prints.

For those of you that are interested in these things, attached is a picture of our “platter farm” in Valencia CA. This is where all the prints are being made up.

The space before, in Academy ratio.

The space after, in sort of Ultra Panavision.

We are getting the prints as 1000 ft. loads, so we have to assemble 20 rolls to make a print up.

About 90 of the prints will be made up for platter operation and shipped totally assembled. The prints are being ultrasonically welded so that it is one continuous piece of film; no splices. The remaining prints are going out for reel to reel houses.

On the right of the frame above you can see part of one of the shipping cases. It is 5 ft. x 5 ft. by 1 ft. thick. When loaded, it weighs about 400 lbs. On the platter next to it, there is a partially disassembled platter reel. With the reel full, out of the box, the film and reel weigh about 250 lbs. Four people can easily lift it onto a platter deck.

We have a dedicated team of four folks working 7 days a week to get this done.

All this makes you appreciate the effort behind the scenes that makes this remarkable enterprise work. (So far, there have been a couple of problematic press screenings, but a dozen or so other shows–notably last night’s SAG screening at the Egyptian–have gone off perfectly.) Whatever you think of Tarantino as a filmmaker (I like him), he deserves credit for exposing a new generation to the volcanic fun of a roadshow presentation. And we should thank Chapin, the guru with the bandit mustache, as well.

Photo credits: Chas. Phillips.

The Hateful Eight.

Talking THE WALK

Kristin here–

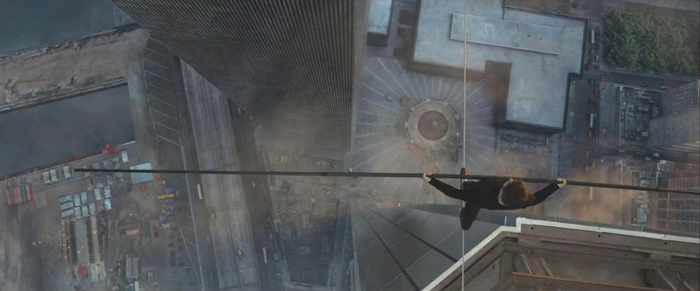

David and I saw Robert Zemeckis’ The Walk the day after it opened. The screening was 3-D Imax, since the film originally opened only in Imax theaters and went wider on October 9, already with the odor of box-office failure wafting over it. We enjoyed it. It’s not an undying masterpiece, but it’s certainly better than many of the reviewers seem to think. In particular, they largely ignore the first portions of the film and imply (or outright state) that you should sit through them because the climactic sequence, protagonist Philippe Petit’s very high-wire walk between the Twin Towers in New York is worth it. David Rooney’s review for The Hollywood Reporter boils down the dismissive attitude toward the early portions: “The film’s payoff more than compensates for a lumbering setup, laden with cloying voiceover narration and strained whimsy.” Peter Debruge’s Variety review is an exception, dealing with the earlier scenes insightfully.

The view from Lady Liberty

I was surprised to see that Matt Zoller Seitz, one of our best reviewers, gave The Walk a mere two and a half stars. Starting to read his review, I was expecting that he might dismiss the early part of the film as too lightweight and comic to balance the spectacular set-piece of Petit’s performance or something of that sort. Instead, his primary objection to the film is the voiceover and sometimes to-camera narration delivered by Petit, who is shown as standing atop the torch of the Statue of Liberty. More specifically, the film opens with a tight close-up of Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit staring directly into the camera against a pale-blue background and saying “Why?” What follows, he says, is to explain why he made his famous walk. The camera then pans to an extreme-long shot of the World Trade Center, pulls abruptly back to reveal the Statue of Liberty (above), and cranes up to Petit standing on the torch.

The rest of the film consists of a series of flashbacks told from this imaginary space, for surely we are not to imagine that Petit ever really climbed the torch. Like it or not, a certain whimsical tone is set up concerning the process of his telling his tale. The film returns to this narrating situation at intervals, usually only for a single shot and usually for a transition into a new scene, with what Petit says in the fantastical present bleeding over into that scene to set it up.

Seitz’s objections to the narration are two. First, he sees it as an attempt to, in a sense, “sell” us The Walk through the enthusiastic tone of the narration. Second, he considers the narration to be redundant, adding almost nothing to the visuals. His prime example of the latter is the scene in which a seagull briefly hovers over Petit and his voiceover comments on its sudden appearance.

The idea that the narration was annoying or redundant never occurred to me when I watched the film for the first time. After reading Seitz’s review, I considered writing this entry and went back to see the film again. I still didn’t find the narration problematic. I think that it contributes to The Walk in a variety of ways. Possibly some of it could be cut, but most of it functions in ways that go beyond what is conveyed through images and dialogue.

Take the seagull scene. Without narration, it could create suspense. Just before it appears, Petit has lain down on the wire, and the voiceover speaks of the serenity of the sky and clouds. Suddenly the bird is hovering right above our hero. The logical reaction would be to worry that it’s going to strike him, break his concentration, somehow threaten him. The voice continues: “Then, something appears. An apparition! A bird. This bird is looking at me! I feel this silent threat.” (The bright-red rims of the bird’s eyes may be a subjective rendition of Petit’s reaction.) The threat he feels, however, is not that the bird will harm him. Instead, he is “invaded by doubt” and decides that it is time for him to end his walk. His narration is not telling us simply that a bird has appeared, but that he takes it to be some sort of symbol of threat. It marks a turning point in the Walk, one which we can only grasp because he tells us that it does. If he had not spoken, what would we have? Presumably Petit seeing the bird, getting up, and continuing his walk. Perhaps he would have a look of doubt on his face, and the music might go into a minor key. Still, we would not know specifically that the bird has caused him to decided to end his walk, because he does not do so for some time after that point. The narration is not simply redundant.

More generally, I think the narrating situation and the treatment of the story as a series of flashbacks with occasional voiceover have two major functions. First, the narration clearly establishes that Petit survives the Walk. Sure, a lot of people walking into the theater know that the historical Petit did survive it and is still alive. Some of us are old enough to have seen or heard news coverage at the time, while others may have read his memoir To Reach the Clouds, upon which the film is based, or seen James Marsh’s 2008 documentary, Man on Wire. Younger moviegoers may have read infotainment coverage of Zemeckis’ film. But there are undoubtedly also people entering the theater knowing nothing about Petit. For them, the film needs to establish his survival if they are not to watch the Walk sequence in constant suspense over whether the protagonist will survive it. The very first word he speaks, “Why?” deflects us from anticipation of the Walk as a spectacular stunt to a curiosity about its significance.

Second, Petit-as-narrator sets the tone for the film, a tone which would perhaps be sufficiently conveyed by the visuals, the action, and the music in some scenes, but not, I think, in others. The tone is light and comic and enthusiastic in the first half of the film, though it shifts later, for reasons I’ll get to in a minute.

Third, the narration helps to break the parts of the film into three separate genres: a romantic comedy (the first half hour), a suspense film (from roughly 30 minutes to 86 minutes), and a lyrical, psychological character study thereafter. The narrational tone changes with each, from ebullience to simple reportage to reflective inner monologue.

David and others have suggested that overall The Walk is structured somewhat like a heist film. In heist films there is emphasis on planning and preparing, with everything explained ahead of time and in intricate detail. The long process of the lead-up is as much the point, or more so, than the actual moment of the theft. (In the review linked above, Debruge points out that “Much of what made ‘Man on Wire’ so thrilling was the fact that Marsh had approached Petit’s story like a caper film.”)

Even though Petit’s goal is not to steal some fabulous treasure from a seemingly impregnable location, his Walk is technically a crime. Still, it is a crime that he cannot conceal, and unlike the masterminds in heist films, he presumably is resigned to the fact that he will certainly be arrested. And unlike in the heist film, there is no planning for an escape and no escape scene. Petit will triumph as long as he completes the Walk before the arrest.

Yet some critics, whether or not they like the film, have ignored or dismissed the rest of the film and focused on the climactic walk as if it is (or should be) the whole film. Some of them, at least, want to treat The Walk as a suspense-filled action film. Yet this is not simply an action film with a boffo climax. Why, though, separate a film into acts in three genres? I think it is because the film wants to clear away the more obvious conventions of a Hollywood films of this type during the early portions of the film. These then drop away in order to allow the Walk sequence to be pared down, without romance and with muted suspense, to a lyrical focus on the peace and beauty of Petit’s perambulations back and forth above the city.

The rom-com

During the first half of the film Petit courts Annie, charms Rudy into helping him, and finds two other “accomplices” to help him fulfill his dream. It’s all a bit like Amélie in tone, with a hint of Jules and Jim in the music. We have to be won over by Petit to some extent if we are to take an interest in anything about the Walk except the facts that the man made it from one Tower to the other and back a few times and that it sure looks great in 3-D Imax.

Some critics clearly weren’t won over. Others were. Debruge points out, “Say what you will about the accent, but Zemeckis and co-writer Christopher Browne have captured Petit’s voice — the real, honest-to-God way he expresses himself — and by channeling that, the actor successfully wins us over from the outset, hanging out in the Statue of Liberty’s torch.” If my own reaction is any indication, one can find Petit a bit hard to take at times and still consider his narration, Lady Liberty’s torch and all, an asset to the tale.

In describing classical Hollywood cinema, David and I have repeatedly pointed out that films in this tradition usually have two plotlines, one a romance and the other to do with work or danger or some sort of project. These two plotlines tend to be connected, with the romance somehow linked to whatever else is happening in the protagonist’s life.

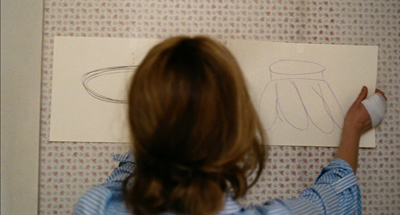

In The Walk, the romance is there, but it is minimized. The development of the attraction between Petit and Annie is squeezed largely into the first quarter of the film. It moves very quickly once we get past the meet-cute antagonism between them over Petit’s stealing the audience listening to Annie’s street singing. Almost immediately they are in a cafe, sipping wine and discussing his dream over a little improvised model (above left), and then in his apartment, with more wine by candlelight and discussion of the dream over a photo of the Twin Towers. The two seem already to be a couple. It’s as if the romance progresses offscreen, in scenes that we don’t witness–the first kiss, the moving in together.

Annie raises no objections to Petit’s crazy goal, as one might expect her to. There is little sense of how much time has passed. All we know is that Annie urges Petit to fulfill his dream, and she becomes his first accomplice. For the rest of the film, she will be little more than first among the accomplices and an onlooker to the preparations and the Walk. Apart from a quick kiss and her loyal overnight vigil outside the Towers as Petit and the other accomplices invade the buildings and set up for the Walk, Annie has almost nothing to do during the preparations for the Walk and the Walk itself. She does, however, get to characterize the lyrical part of Petit’s achievement. Later, when Barry remarks now New Yorkers love the Trade Towers, Annie adds that Petit has brought them to life for people and given them a soul. The romantic plotline is further undercut almost immediately, however, when Annie unexpectedly leaves Petit to return to France and find her own dream.

During the first half of the film, Petit’s narration is humorous, bumptious, perhaps a little too ingratiating, depending on your taste. He might seem a bit annoying and capricious, as young men often are in rom-coms. The implication may be that the quirks of his personality are part and parcel of the genius and drive that allow him to perform the feats he does, as his cocky little smile upon being arrested for walking between the towers of Notre Dame suggests. (Note that Barry, who eventually becomes the “insider” accomplice once the team arrives in New York, says he had witnessed Petit’s Notre Dame walk, and sure enough, there he is in the back of this shot and visible in another view of the crowd watching.)

If Petit is selling anything, it’s not the film but himself, and we do not need to like him to admire him.

The suspense film

Petit and his accomplices to go New York at roughly the midway point of the film, and The Walk segues temporarily into a suspense film. Where one might expect the Walk itself to be the section designed to ramp up suspense in the audience (as many critics did), the more conventional suspense-generating actions are more prominent in the preparation for it, which constitutes the third quarter of the film. This takes place from 55 to 86 minutes. It begins at the airport, with a comic scene of a customs official reeling off the contents of Petit’s equipment containers (above). When he asks what the equipment is for, Petit cheekily replies that he’s planning to use it to walk between the Twin Towers. The official unconcernedly allows him through.

Soon the tone becomes more serious, as Petit visits the Towers and is overawed and intimidated to the point of feeling that his plan must be abandoned. Standing in the lobby of the South Tower, he speaks of feeling that there is no way to get to the top. Immediately a service door behind him swings open, a worker appears and greets them, and the man departs, leaving Petit to investigate the room beyond, discovering a stairway to the top.

Soon he emerges on the top of the building, tries teetering over the void on a projecting metal girder, and is clearly ready to take up his dream again.

Eventually the tone of the Development turns more tense, as Petit obsessively goes over the plan with his accomplices and the day of the “Coup” approaches. Late on the night before the group invades the Towers, Petit awakens and nails shut the “coffin,” a crate containing the equipment, and expresses his doubts to Annie. Ebullience has become dead seriousness, though Petit determinedly avoids referring to death.

Once the actual invasion of the Towers begins, the tone ratchets up the tension and the delays typical of a Development portion occur. Although the team’s fake delivery truck is admitted to the loading docks, a lack of access to the elevators nearly scuttles the plan. Once Jeff and Petit are on the unfinished upper stories of the South Tower, a guard interrupts them as they unload their equipment in the unfinished upper stories of the South Tower. They end up hiding for fours astride a metal girder above an unfinished elevator shaft extending down so far that we can’t see the bottom. Jeff, who suffers from a terror of heights, becomes our identification figure briefly, as he suffers through this ordeal. Later, once they are on the roof in the dark of night, a guard comes up with a flashlight and nearly bumps into Jeff before being lured away to a lower floor by a colleague offering to share a pizza.

As dawn approaches, the threats to the success of the Walk continue. An arrow is shot from one Tower to the other to begin the process of hauling the wire across teeters on the corner of the building. The bracing wires are loose, and Petit must drag a terrified Jeff onto the side of the roof to help tighten them. At dawn, a mysterious man in a suit visits the roof, apparently just for the view, and sees them. After a nerve-wracking face-off, he ultimately leaves without challenging them.

Interestingly, during this face-off, Petit picks up a length of pipe. After the man leaves, Petit seems shocked to find that he has been holding it in a potentially threatening fashion. This is the only hint we ever get of the lengths to which he might go to make his dream succeed.

There is also a good deal of exposition in this section of the film, part of it accomplished by the narrating voice, setting up for what will happen during the Walk. As a result, we don’t need to be told about the technical details during the Walk itself. There is, however, a fairly long stretch with no voiceover leading up to the silent confrontation with the mysterious man. After he leaves, Petit’s narration notes, “And that was the moment in my adventure that I call ‘the mysterious visitor.'”

This last incident works in with the many other bits of good luck that have allowed Petit to accomplish his dream, including the fortuitous opening of the stairwell door mentioned above. It adds a touch of suspense, as well as realism. Such things do occur–and in this case, really did occur.

The lyrical walk

Romance and suspense having been presented and set aside, the film defies convention by switching into lyrical mode. In a conventional film, the grandeur of the mise-en-scene would become a terrifying void (especially in 3-D) into which we constantly fear Petit will fall. Instead, to a large extent because of the narrating voice and the music, we instead follow Petit’s exhilarated reaction and his every shift of mood. For instance, when he stands with one foot on the wire and pauses before beginning his Walk, subjective mist gathers (see bottom). It conveys his sense of the rest of the world disappearing and his attention focusing entirely on the wire. His voiceover describes all this. Would we otherwise perhaps take this mist to be an actual passing cloud?

Similarly, when he finishes the first crossing and starts back, would we understand why if we had only the image and music? Or when he kneels during the return trip to the South Tower, would we grasp that he is saluting the wire, the Towers, and so on, if his narrating voiceover did not tell us?

There are details that set up some suspense but are at the same time tied to Petit’s emotional reactions. He remarks that one of the the cavaletti holding the bracing lines onto the wire being upside down. This seems initially to be used as an occasion for Petit to mention his gratitude to Rudy, though it also sets up for the later moment when the plate threatens to buckle under the strain–a moment which ultimately comes to nothing.The detail shot of Petit’s shoe during this scene sets up some suspense, in that a small, wet patch of blood suggests that he may later be endangered by the wound from stepping on a nail. Later we see more blood on the shoe, but the wound in fact never causes him to falter. In this close shot, the shoe also conveys a visceral sense of the moment of the walk and reminds us of the practice that has gone into it, imprinting a channel where the wire has pressed into his foot.

Of course, we are unable entirely to view the scene without suspense, as our bodies naturally react to the strong illusion of height created by the extraordinary CGI imagery and the 3-D. The word “suspense,” after all, derives from the notion of dangling in space. Yet the film constantly backs us away from such jitters in part through the soothing voiceover.

Suspense also returns to some extent just after the salutes, when the police appear, initially on the South Tower end of the wire. An even greater threat, a police helicopter, eventually appears.

These authorities offer or threaten to help Petit off the wire, endangering him in the process. His evasive maneuvers and defiance create humor that somewhat dispels the suspense. Ultimately, by tossing his balance pole at the outstretched hands of the startled police, Petit manages to clear the way for a triumphant exit from his Walk. This conclusion assures that he controls the entirety of his feat, despite the fact that he is immediately arrested. The applause of the workmen on the lower levels as he is escorted out confirms his triumph, as does the praise offered by one of the arresting officers (seen at the left below). The voiceover description of his later minor “punishment” of performing a lower-wire act for children in Central Park confirms that he has successfully defied even the law.

Zemeckis, classical director

While Zemeckis has a reputation as a master of the action set-piece, he can also construct a tight classical narrative. Seeing The Walk a second time for the purpose of writing this entry, I realized that the script is very carefully put together to set up for everything that will happen, both causally and in terms of information.The arrest in Paris makes it clear to us that Petit will face a similar punishment after his Trade Towers Walk. Petit’s fall from the wire in the circus tent and Rudy’s emphatic advice that the last three or four steps are the most dangerous foreshadows the similar moment at the end of the Walk where Petit momentarily looses control and his trembling makes the wire itself shake. In many cases, the voiceover plays a vital role in setting up things to come.

Perhaps it’s not as perfectly put together as Back to the Future, but then, few films of the past decades in Hollywood are.

As David noted during our first viewing, the film also has a good, old-fashioned Hollywood visual motif. Round shapes are contrasted with straight lines, the round ones being associated with Petit’s early ground-based entertainment career and the lines with his high-wire acts. The lines may be obvious to viewers, as when Petit draws a line between the Towers in an image, or less so, as in the scene where an arrow is tested as a means for starting the process of sending the wire from on Tower to the other.

Unfortunately none of the video material currently online shows portions of the street-entertainment scene of the film’s early section, so I can provide no images of the round items. These include the perfect chalk circle that Petiti draws to delineate his performance space, the top hat in which he collects coins, the red-and-white candy mint, his unicycle’s wheel, the ring under the White Devils’ tightrope in the circus tent, the arch in the same ring that frames Petit when he juggles to impress Rudy, and the umbrella he uses to shelter Annie in a sudden rain shower.

Such imagery disappears in the second half, apart from repeated overhead shots of the circular fountain on the ground between the Towers, often with the lines of the wire and the balance bar juxtaposed with it (see top). It recalls Petit’s initial performance space on the ground and subtly reminds us of how far, and high, he has come since then. (During their first meeting, Annie remarked of Petit’s tightrope, “That was the lowest high-wire I’ve ever seen.”)

In the end, the answer to the original question, “Why?” is that “There is no why.” When Petit sees a beautiful place in which to place his wire, he feels compelled to do so. His motive is not to show off his derring-do or to spice up his life with risk-taking. His is an aesthetic compulsion, and the Walk is referred to a number of times as an artwork. The form of the film reflects that compulsion.

The last lines of the film return to the Towers themselves. Petit narrates over a shot of himself returning to visit the top of the Towers, telling us that an official gave him a pass to visit it. We return to the torch atop the Statue of Liberty, where he looks at the card and says, “He wrote on it ‘Forever.'” This could have been told visually, I suppose, but it would have meant close-ups of the card, probably a second person on the roof to whom Petit could explain his card–something, at least, more elaborate and less effective than simply having him tell us this information. A pan moves us toward the Towers, gleaming in the sunshine until the slow fade-out that conveys the fact that for the Towers, forever was cut brutally short. That final salute, at least, seems to have pleased everyone.

As I said at the outset, The Walk is not necessarily a masterpiece, but it is far better than some of the reviews would claim. Seeing the film a second time, I enjoyed it more and found new things to notice, which is always a good sign. I did not find the voiceover narration annoying during either viewing, and it isn’t really dispensable. The film is worth seeing, and its extraordinary climactic scene will suffer greatly from being seen on a video screen.

The Wire provides another example of a phenomenon which David discussed in relation to Paul Greengrass’ United 93: our inability to wholly suppress a feeling of suspense even when we know the outcome of an event. Simply seeing Petit on the wire high above the ground to some extent creates an involuntary state of tension.