Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

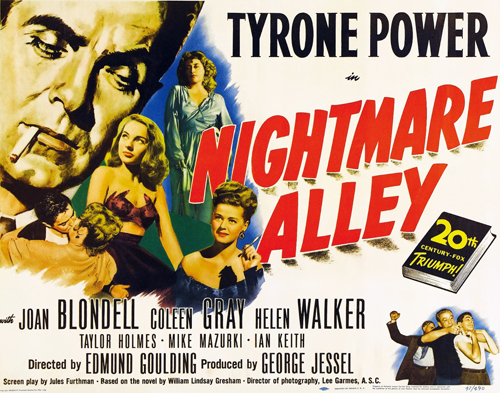

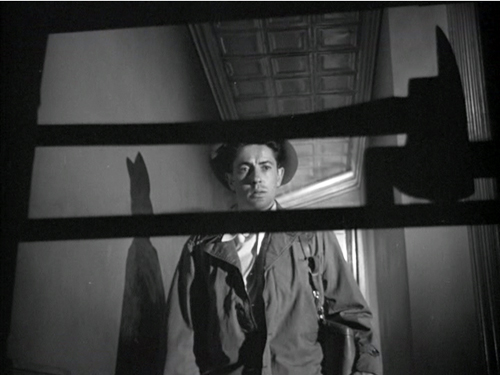

NIGHTMARE ALLEY: Do we hear what he hears?

DB here:

In the 1940s, American cinema turned wildly subjective. Visions, daydreams, nightmares, optical and auditory POV, inner monologues, flashbacks, and stream-of-consciousness montages were popping up everywhere. Sometimes these techniques rendered what it felt like to be the character at that moment. At other times, they were occasions for gags, or padding, or spikes of emotion, or flamboyant spectacle.

Sometimes they were just weird.

Siren song

One of the most intriguing passages in Forties films comes at a climactic moment in Nightmare Alley (1947, the year I was born). Spoilers ahead.

Stan Carlisle has been involved in a complicated swindle with the help of psychologist Lilith Ritter. He has entrusted her with $150,000 in cash extracted from their mark. When the plan goes wrong, he reclaims the money and heads for the railroad station to meet his girlfriend Molly.

In the cab en route to the station, Stan discovers that the wad of cash Lilith has given him consists of 150 singles. He returns to her apartment to confront her. There Lilith suddenly goes coldly clinical, declaring that Stan is deluded. Just as he thinks he killed a man in Texas, and he has imagined that she’s involved in his swindle. She denies any collusion with him, but does hint that she could get him indicted for the killing.

Since he has been growing more anxious, her calm stream of lies unnerves him. And since she records all her sessions with her patients, she has his first visit as a confession to the Texas killing. She has been careful to never record their swindle plot.

As Stan gets more panicky, we hear a police siren. He reacts, but Lilith does not. She claims not to hear it; she says he’s just imagining it, like everything else. When she offers to take him to a hospital, he pulls away and flees, without his money.

Here’s the scene.

Is the siren objectively in the scene, or is it in Stan’s head?

Lilith says she doesn’t hear the siren, so it might be subjective, manifesting Stan’s guilty conscience. And all the psychologist’s talk about hallucinations may have induced one in him. But the siren isn’t distorted in the way most auditory imaginings are; it seems plausibly part of the story world. And many viewers (including me, on my first viewing) assume that Lilith or her servant Jane has called the police, and the cops are now arriving. Lilith could be pretending not to hear the siren in order to convince Stan he’s loco. She does tell him to stay for a sedative.

There are several oddities here besides the siren. For one thing, Jane has made her entrance keeping Stan covered with her pistol. When Stan and Jane leave the bedroom, we see Jane hovering in the background.

As Lilith comes out she cocks her head screen left, signaling to Jane, and swivels the pistol firmly toward Stan.

Once Stan and Lilith get into their argument, though, Jane is no longer seen or heard. She’s last glimpsed as a sleeve on its way offscreen.

We never see Jane definitely exit the room. Is she there or not? Did Lilith’s head gesture mean “Stand over there to keep him covered” or “Go off and call the police”? The film’s continuity script (typically a transcript of the editor’s version with dialogue and effects but without music) says only “Jane crosses and exits scene.” That could mean she leaves the room or merely leaves the frame.

Moreover, we learn from cinematographer Lee Garmes, who shot Nightmare Alley, that Goulding preferred clearly signaled entrances and exits.

He had no idea of camera; he concentrated on the actors. He had the camera follow the action all the time. He was the only director I’ve known whose actors never came in and out of the sideline of a frame. They either came in a door or down a flight of stairs or from behind a piece of furniture. He liked their entrances and exits to be photographed. I like that; they didn’t just disappear somewhere out of the frame-line as they so often do.

“Disappear somewhere out of the frame-line” is just what Jane does.

Jane’s presence or absence matters because of the quarrel that ensues. When Lilith announces her betrayal of Sam, we might expect the muscular Stan to attack her, slapping her around like the good noir sucker he is. But he meekly takes her assault. True, he’s coming apart, but maybe he’s holding back partly because Jane still has him covered from offscreen. That assumption seems validated at one point, when Stan’s nervous glance sharply off right suggests that she’s still there with her pistol. It’s after that glance that he warns Lilith not to call the cops.

Of course he could be imagining Jane in another room calling the police. On the other hand, if we assume that Jane remains offscreen, Lilith’s cool story about Stan’s breakdown becomes motivated as a performance in front of a witness who can back her up.

Maybe the handling of Jane is just clumsy direction on Goulding’s part? Or just conciseness? Still, there’s that siren. If Jane is in the room all the while, and we don’t hear her telephone the cops offscreen, the siren can’t be the result of a call for help. And it’s not clear that Lilith had the time to phone the police after Stan left the bedroom.

So maybe the siren is indeed in Stan’s head. Or if it’s objectively in the story world, then maybe it’s just a coincidence. (Chicago has plenty of sirens.) In this case, Lilith takes advantage of the siren to weaken Stan’s grip even more. A further complication: The siren cuts off as Stan flees, but there’s no indication that the cops have arrived outside. And in another oddity, we see Lilith turn slightly toward the camera when she denies hearing the sound. Is this a mark of evasion, like blinking?

In sum: The siren is either subjective or it’s objective. If it’s subjective, it’s at variance with most subjective sound of the period in not being signaled clearly as such. If it’s objective, it’s either the result of somebody calling the cops from offscreen, or it’s just coincidental.

Which is it? Usually a Forties film is pretty explicit when we’re in a character’s head, if only in retrospect (e.g., the staircase “death” in Possessed, 1947). Nightmare Alley seems to fudge things here.

When being a geek isn’t chic

Am I over-thinking this? The commentators on the Eureka! DVD, noir experts Alain Silver and James Ursini, puzzle over the siren too. I think that when Lilith denies hearing it, most viewers feel a bump: after all, we hear it too. But soon, I think, most of us take it as a real siren and assume that Lilith seizes on it as another way to convince Stan he’s breaking down. As for Jane, we just forget about her.

Look at the overall film, though, and the subjectivity possibility gains a curious strength. The siren can be taken as part of a peculiar pattern running through the film. To show you what I mean, I need to rehash a fairly complicated plot. Bear with me.

Stan Carlisle, an ambitious carnival worker, is conducting an affair with Zeena, the fortune-teller, while her partner Pete sinks into alcoholism. Stan accidentally kills Pete by giving him a bottle of wood alcohol instead of moonshine. Partnering with Zeena, Stan masters a code system for a mind-reading act. Soon he has left Zeena behind and married the carnival entertainer Molly, who becomes his confederate in a ritzier nightclub mentalist act. But Stan is plagued by memories of Pete’s death. He visits a psychologist, Lilith, to whom he tells his guilt feelings.

Stan conceives a grand scheme to turn faith healer, using his skills at illusion and fake spiritualism. (“The spook racket: I was made for it.”) He manages to deceive the rich Ezra Grindle, who asks to see his deceased lover. The scheme, in which Molly impersonates a spirit, fails and Stan has to flee, hoping to take with him the money he’s already wormed out of Grindle. Lilith blocks that in the scene I’ve excerpted.

Stan leaves Molly and begins to spiral downward into drunkenness. By the film’s end he’s ready to take on the job of the geek, the subhuman carnival freak who bites heads off chickens. Originally Stan had despised the geek, but now, in order to be guaranteed a bottle a day, he declares: “I was made for it.” Only Molly’s tender concern holds out hope Stan might claw his way back.

I said the plot was complicated, but it rests on a set of fairly simple substitutions. The opening situation gives us two couples, Zeena and Pete, Molly and the strong man Bruno. Initially Stan was odd man out, paralleled by the geek (also on the fringes of the action). Stan replaces Pete as first Zeena’s lover and then her stage partner. But once Stan knows the mentalist codes, he can replace Zeena with Molly, whom Bruno surrenders. Later Zeena and Bruno will form a couple. In Stan’s rise, Molly gets replaced by Lilith, his partner in crime, if not in romance. When Stan’s swindle fails, he goes on the run, alone again. Pete was established as one step up from geekdom; without Molly, he said, he’d be a geek. Now Stan becomes the new Pete. Drinking around a campfire with bums, he even repeats Pete’s cold-reading spiel word for word and gesture for gesture, with a bottle of booze as the crystal ball.

Stan finally sinks to the bottom, willing to serve as a carnival geek for the standard bottle a day. Molly now plays Zeena to the new Pete.

The pattern of sound leading up to the siren scene centers on the geek. In the crucial scene in which Stan gives Pete the rubbing alcohol, the geek’s cries punctuate the action as he dashes around in the distance; like Pete, he needs his daily bottle. But we hear those cries three more times later, when the action has left the carnival. The cries are displaced from their original source, and more insistent on each appearance.

The first time, they’re very faint. Zeena and Bruno have called on Stan and Molly in their nightclub dressing room. Zeena has brought out her Tarot deck and seeing Stan’s future she warns him not to try the big thing he’s contemplating. (It’s the fleecing of the grieving Grindle.) Worse, her cards bring up the Hanged Man, the same card that Zeena turned up for Pete. Once the association with Pete has returned, it’s hard to exorcise.

Angry, Stan forces Zeena and Bruno out, and as he stands at the door, with the music rising, we can hear the distant cries of the geek. In the next scene, the association with Pete is strengthened. Stan is getting a massage and the smell of the rubbing alcohol reminds him of the night of Pete’s death. Now, more strongly, we hear the geek.

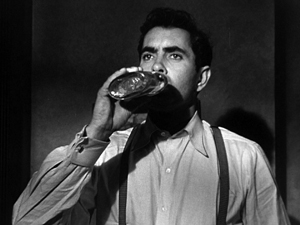

The motif-cluster is Pete’s death/Hanged Man/rubbing alcohol/the geek. This is brought back again, most obviously, when on his downward path Stan is holed up in a hotel room and instead of eating starts to guzzle a bottle of gin.

The compulsive drinking, along with Stan’s disheveled life, marks another stage in his conversion into Pete, and the geek’s cries are heard most plaintively now.

So what do we make of the geek’s cries in these scenes? If we take them as subjective, as Stan’s auditory flashbacks or imaginings, then the siren moment gathers a new force. If we’ve had access to Stan’s mental soundscape earlier, maybe we have it again when he “hears” the police coming. After several instances of subjective sound, we’re more prepared to take the siren as subjective too—and to wonder a bit about it even after we’ve concluded that it’s probably objectively in the scene.

That feint would be an interesting storytelling maneuver in itself. Yet other factors complicate things.

The geek goes Greek

In 1940s movies, there’s plenty of subjective sound. Often we understand that a sound is subjective by virtue of its acoustic quality; it may be given extra reverb or distorted in other ways. We also take it as subjective because the sound clearly isn’t coming from the scene. We often remember it from prior scenes and so treat it as an auditory flashback. But there are visual cues for subjective sound too. The two primary ones are a close view of the character whose mind we’re in, and an expression on the character’s face that indicates some intense feeling.

In The Fallen Sparrow (1943), Kit recalls his months in a Spanish prison chiefly through the scraping limp of one of his captors passing in the hall. When we’re given access to that acoustic memory, we get fairly close shots of Kit’s agitation.

In an interesting parallel to Nightmare Alley, when Kit is with Whitney, he thinks he hears the scraping footbeat again.

It might be a genuine offscreen sound, since we have reason to believe that his torturer has followed him to New York. (In the climax, the sound will be actual, not imaginary.) But at this point Whitney says she doesn’t hear the noise, and neither do we. This indicates that Kit is imagining it. The filmmakers faced a problem comparable to that in the Nightmare Alley scene. If the sound had played for us as well as for Kit, and Whitney said she didn’t hear it, the options are three: we’re in Kit’s head, though she isn’t; it’s real and she truly didn’t hear it; or it’s real and she’s lying (as Lilith may be). We couldn’t be absolutely sure we were in Kit’s head if the sound had been included, but when it’s not on the track, we know he’s hallucinating.

There are several norms to consider here. First, typically the close shot is timed to coincide with the subjective sound, indicating that the character registers the sound when we do. That happens in The Fallen Sparrow, but not in Nightmare Alley. We notice the siren before Stan does, which suggests that it’s objective.

Second, the shot isolating the character favors our taking a sound as subjective. But when another character is in the shot, it’s harder to construe as subjective. Accordingly, in The Fallen Sparrow, the shot that includes both Kit and Whitney inclines the filmmakers to treat the shot as objective and the sound as purely private, as inaudible to us as it is to her. In Nightmare Alley, the siren does indeed start over a close-up of Stan, but it continues over a reverse-shot of Lilith and soon enough, over a shot of the two of them.

Finally, our sense of subjectivity depends partly on the intrinsic norm each movie sets up. In The Fallen Sparrow the scraping footstep takes its place in long stretches of inner monologue which vocalize Kit’s thoughts. Because we’ve had intimate access to his mind, we’re likely to accept the footstep we hear as subjective as well. But Nightmare Alley doesn’t include inner monologues. We never access Stan’s stream of thought, so the geek cries are the only moments we might be plunging into his mind–at least, until (perhaps) the siren scene.

The siren scene hangs uncertainly between subjectivity and objectivity, tilting toward objectivity but also casting some doubts on it. What about the geek sounds? They’re even more complicated. They seem to hang between subjectivity and–well, something else.

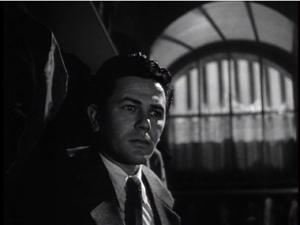

Take the first instance. Stan is at the doorway and the camera tracks in to him as the musical score emerges. The geek noises slip in, and Stan pauses, as if reflecting.

That seems like a fairly standard cue for subjectivity: Stan has associated the Tarot cards and Pete’s death with the geek’s cries. Because of the faintness of the noise (some people seem not to notice it, as if the score nearly drowns it out), the narration might even be hinting that Stan’s memory of the night of Pete’s death is barely conscious.

In the light of the later occurrences, I’d propose another possibility. Given that we’ve never been in Stan’s head before, the sound might be more addressed to us than to him, reminding us of an association he doesn’t sense at all. This moment might almost be the film’s way of taking us aside and flagging a motif that will develop later–and in ambiguous ways.

In the rubdown scene, we see Stan, anxiously reacting to the smell of alcohol, in a fairly close view as the geek’s cries are heard.

In great anxiety, he leaps off the rubbing table. But perhaps he’s reacting just to the smell of alcohol, not to his memory of the geek. Again, the geek sounds are smoothly merged with a burst in the musical score.

Most characters who hear imaginary sounds report them to the people around them. But Stan hasn’t said anything, as far as we know, to Molly about twice hearing the geek. When Stan tells Lilith of the two earlier scenes during his therapy session, he mentions only being disturbed by Zeena and the cards, and the way the alcohol reminded him of Pete.

He doesn’t mention hearing the geek’s cries. So again we might ask if these cries aren’t subjective but rather something like a nondiegetic score–the soundtrack reminding us of something Stan isn’t remembering.

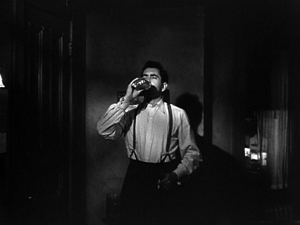

The last recall of the geek’s cries is presented while Stan is gulping gin. The noise starts in a medium shot before the camera retreats to a distant view.

If the cries make him feel tormented, he doesn’t give much sign of it. And if we were supposed to penetrate his mind, where the geek noises might reside, the camera would typically track in more tightly (as it does in The Fallen Sparrow). Instead, it withdraws, again raising the possibility that the geek’s shrieks are a commentary, not a recollection. Perhaps the cries are more like the Greek chorus warning us of an outcome to which the protagonist is oblivious.

What are we left with? Mixed signals, I think. The geek’s cries and the police siren hover in a space that many films worked within but seldom treated so freely. The cries can be taken as subjective, but they lack robust cues for that function. In other respects, they suggest expressive commentary. As the alcohol reminds Stan of Pete’s death, the cries do the same for us, while prophesying Stan’s fate. And the siren, while probably objective, makes us hesitate partly because we’re not sure the police have been called and partly because we’ve had ambivalent sound cues earlier. For a moment it might seem to be, as Lilith says, Stan’s first full-blown hallucination.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley duly notes the siren’s sound, and the geek’s cries are noted in the scene of Pete’s death. But there’s no mention of geek cries in any of the three scenes I’ve considered. Perhaps director Edmund Goulding shot the film without planning to include the geek sounds at all. Perhaps they were added in postproduction. Someone late in the production process may have decided to anticipate Stan’s final degradation through ever more vivid echoes of the poisoning scene. Nightmare Alley would become an example of innovation by last-minute intervention.

Usually a 1940s film respects the distinctions, the either/or options, that are offered by the era’s stylistic menu. Accordingly, a sound is clearly objective or clearly subjective. But sometimes a film oscillates between the choices, or blurs the distinctions among them. We’re most familiar with this slipperiness when music shifts between being diegetic (sourced in the story space) and being nondiegetic (added to the story world “from outside”). This sort of looseness can be found elsewhere in 1940s storytelling. A film may start with one narrator and end with another, or none, or an uncertainly identified one. A flashback may never close, or loop back to its beginning without returning to the frame story. The outliers coax us to study how the ordinary cases work and note how much we take their conventions for granted.

We can learn as much about storytelling strategies from the ambivalent films as from the trim and polished ones. And in a movie called Nightmare Alley, we can’t regret that the haunting wail of the geek wafts through it as both a reminder of death and an anticipation of destiny. Its shape-shifting sound fits a movie that wants to unsettle us.

Fussbudget film analysis: I was made for it.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley is available as a pdf file on the Eureka! DVD of the film.

Lee Garmes’ remark about explicit entrances and exits is quoted in Charles Higham, Hollywood Cameramen (Thames & Hudson, 70), 49-50. For background on the making of the film see Matthew Kennedy, Edmund Goulding’s Dark Victory: Hollywood’s Genius Bad Boy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 241-252. There’s a detailed and intriguing psychoanalytic interpretation of the film at Randomaniac.

Actually, the scene in The Fallen Sparrow is a little more complicated than I indicate here, but I didn’t want to get into the weeds. The essential point holds, though: when one character thinks that a sound is veridical, and another character is present but doesn’t hear it, the filmic narration can confirm or disconfirm or ambiguate the source of the sound.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin, Jeff Smith, and Jim Healy about the film. Woody Haut’s lengthy discussion of the film for the Eureka! disc is reprinted on his website.

I discuss extrinsic and intrinsic norms of narration in Chapters 4 and 8 of Narration in the Fiction Film.

For other example of fruitful anomalies in the period, see “Innovation by accident,” “Twice-Told Tales: Mildred Pierce,” and the Laura discussion in “Dead Man Talking.”

Sometimes a reframing…

Side Street (1949).

DB here:

…just knocks you out.

“It can only be fully recommended to those who have a deep and morbid interest in crime.” Snooty judgments like this made Bosley Crowther the critical joke of generations. Today film lovers wear their deep and morbid interest in crime as a badge of honor. Especially when the crime is covered by Anthony Mann.

In Side Street (1949), Joe Norson has lost his business and works part-time as a postman while he and his wife await their first child. Having come back from war and wanting to give Ellen a good life, Joe is tempted to steal money he’s seen lying around the office of a crooked attorney. He grabs a folder containing what he thinks is a couple of hundred dollars; instead, it holds $30,000 of blackmail money. The woman who chiseled the money out of a businessman turns up dead, and the police are investigating. When Joe naively loses the money and sets out to recover it, he’s drawn into the murder, tracked by the gang, and targeted as a prime suspect by the police.

Variety and Crowther chided the screenwriters for a sketchy plot, and the complaint is somewhat fair. Joe is an unusually weak protagonist. He botches both his theft and his cover-up, leaving a trail that’s easy for the killer and the cops to trace. Because Joe is fairly passive and on the run, and he has to follow his clues in a fairly linear manner, and his schemes to fight back come to almost nothing, the action is filled out by scenes of the gang and the police tracking him.

What partly compensates for the plot’s problems is the bold location shooting. As part of the semi-documentary trend of the period (the film opens and closes with worldly-wise voice-over narration from the Homicide Captain), Side Street presents itself as a story rooted in urban reality. And indeed it is a triumph of location shooting. The characters visit a bank, Greenwich Village, Bellevue Hospital, and many neighborhoods. The final chase, with Joe trapped in a taxi with the killer and pursued by three cop cars, is a tour de force of geometrical shot designs that make city canyons part of the drama.

Mann has long been praised for integrating the forces of nature into the action of his Westerns, but this film shows his flair for cityscapes too.

Given the constraints of location filming, the freedom of Mann’s camera is all the more arresting. This time he’s not working with John Alton, the cinematographer most in tune with his baroque sense of light and framing. But Mann still gets punchy results from ace DP Joseph Ruttenberg. There is nothing quite so staggering as Alton’s framing of Claire Trevor and the cabin clock in Raw Deal, let alone the Grand Guignol imagery of Reign of Terror, but Ruttenberg does give us plenty of nicely dense compositions, exploiting the verticals and apertures available on location. There’s also a neatly discreet shot of a revolver peeking out from behind a door in distant long-shot; the shadow supplies the telltale shape.

Mann is a post-Kane filmmaker. Like nearly every Forties director of dramas, he learned from Toland and Welles that it’s fun to shove the action into the viewer’s face. The high angles of the city are counterbalanced by steep, low setups both inside and outside. Mann never met a “Russian angle,” or a ceiling, he didn’t like.

When the lens is more or less straight on, the frame can be tight and actors’ heads are packed into the frame like cantaloupes in a supermarket display.

In motion, the camera isn’t safe. Actors rush past the lens or thrust themselves straight at it.

When Joe flings himself out of a car, prepare to find yourself in the middle of traffic, with a truck rushing at you (a stunt done in real space, not against a back-projection).

Yet even studio-shot back-projections retain vigorous, immersive depth.

Mann’s visual dynamism, complete with aggressive foreground and distant depth, hits a high point in the dialogue-free scene that’s the topic of today’s sermonette. Joe hasn’t planned to steal the money, but circumstances lure him on. The lawyer’s out of his office, and the door has been left ajar. Joe earlier saw the money put into a file drawer, and as Joe prepares to slide the mail under the door, the cabinet stands temptingly in the foreground.

He impulsively heads for the cabinet, pauses before it, and then—thanks to an abrasive cut—grabs the handle violently. The drawer is locked. He recovers himself, almost grateful that he’s blocked, and he lurches out the door. No theft today, apparently.

Outside, Joe seems to be going on his way, but the long shot shows a barrier, like a railing in the foreground. It seems about as innocuous as the car hood we saw when Joe went in the building.

As Joe approaches, the camera tilts up to follow him and he stops, staring. He’s framed before what’s now revealed as a fire axe.

Another director—Hitchcock, perhaps—would have handled this with a medium-shot of Joe leaving and looking off, followed by an optical POV shot of the axe. Or you could show him leaving in the foreground, with the axe mounted in the distance; he glances back, sees it, and decides to go fetch it.

By contrast, Mann’s approach yields a sharp one-two snap: Joe approaches/ he stops. We see the axe, but almost by accident; the reframing is just following Joe’s movement. And we don’t need to see any more of the thing but its distinctive shape—its pure axe-ness given in silhouette. Rudolf Arnheim, who always advocated pictorial simplicity, would be pleased.

After a beat, in an abrupt cut, Joe grabs the thing.

He lunges down the corridor back to the office and starts to break into the cabinet. Now his violent adventure begins.

Crime I’m not so sure of, but with bodacious filmmaking like this, who wouldn’t acquire a deep and morbid interest in cinema?

It’s been too long since our last “Sometimes…” entry. For the others see: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…”

Bosley Crowther’s review of Side Street is “The Screen: New Crime Story,” New York Times (24 March 1950), p. 29.The Variety reviews, more or less identical, are in Daily Variety (22 December 1949), p. 3, and Variety (28 December 1949), p. 6. The Times covers the shooting of the climactic chase in “Taxi Acrobatics in Wall Street” (8 May 1949), X5.

For more on the postwar cinema’s love affair with vigorous depth staging and depth of field, see this entry on Bergman and Antonioni, this entry on Toland and depth of field, this entry on Manny Farber’s objections to Huston, this entry on dense staging, and this entry on Wyler’s staging in The Little Foxes. For much more see Parts Three and Four of our Film History: An Introduction, Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Side Street.

Dead man talking

Confidence (2003).

DB here:

“So I’m dead.”

At the start of Confidence we hear Jake Vig’s voice as we see him lying bloodied on a pavement. As the protagonist of a neo-noir, Jake recalls the classic start of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). There Joe Gillis (an echo of gigolo?), floating face-down in a swimming pool, begins to recount his stay as a kept man of faded film star Norma Desmond. That opening has become a touchstone for the grim fatalism of film noir, as well as a mark of daring screenwriting. The guy telling the story is dead! How cool is that?

Anybody interested in how films tell stories has to be interested in narrators, those figures—either mere voices or tangible characters—who recount, recall, or replay the story action. And anybody interested in Hollywood film knows that such narrators are hallmarks of a giddy period of cinematic innovation, as recognizably “1940s” as flashbacks, moody subjective sequences, and twisty plots. In that era we find narrators well outside that terrain known as noir. Romantic dramas, family sagas, comedies, Gothics, musicals, and other genres made ample use of voice-over commentary, and it didn’t always suggest a doom-laden atmosphere.

Still, dead narrators seem to be pushing things. They flout realism (How can a dead person tell anything?) and they raise problems of logic (To whom is this person speaking?). Is it a chatty corpse (Wilder originally wanted a morgue opening introducing Gillis) or an ethereal spirit divorced from the dead body?

Dead narrators turn up surprisingly often in the 1940s. During this period, as I’ve argued on this site and in the book I’m working on, many storytelling techniques we take for granted coalesced. There emerged a rough menu for handling them, and ambitious filmmakers played with several possibilities. That play didn’t stop in the Forties; we still have new versions of flashbacks, subjectivity, and the like. So let’s look at posthumous narrators in the Forties, with some glances at a trio of more recent efforts.

As a non-dead and highly reliable narrator, I must warn you of spoilers ahead.

Guiding spirits

The Human Comedy (1943).

Most simply, posthumous narration can be motivated as letters (Letter from an Unknown Woman) or diary entries (Thatcher’s journal in Citizen Kane). Similarly, Heaven Can Wait (1943) gives us a dead man explaining episodes from his life to an inquisitive official in the afterlife. The more flagrant cases, however, involve dead narrators who recount the entire film we see in voice-over, as in our prototype Sunset Boulevard. Knowing that the protagonist is dead at the start shifts our attention to how he or she will die.

Posthumous narrators go back a fair bit. In literature, Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) presents the ruminations of the town dead, in the manner of the cemetery climax of Our Town (1938 play, 1940 film). Wilfred Owen’s poetic monologue “Strange Meeting” (1918) presents soldiers reuniting in Hell, ending with the poignant line, “Let us sleep now….” Addie Bundren, the dead mother of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), narrates portions of the novel from her coffin. In a pulpish pastiche of Faulkner, Kenneth Fearing’s mystery novel Dagger of the Mind (1941) includes a chapter narrated by a man who’s been murdered. Radio drama also included voices from the beyond. Examples include “Ghost Ship” (1940), with a victim recounting his own murder, and Norman Corwin’s “Untitled” (1944), which reveals the narrator to be a dead soldier.

In film, World War II brings forth the prospect of dead servicemen returning to tell their tales. “I am Matthew Macauley,” says a face superimposed over imagery of radiant clouds. “I have been dead for two years. But so much of me is still living that I know now that the end is only the beginning.” This is indeed a beginning, of The Human Comedy (1943). Having died in the war, Matthew will guide us back to his hometown and his household’s daily routines.

Matthew’s voice-over goes on to introduce his family members, including son Marcus on duty in the army. After a scene in which a spectral Matthew joins his wife at her work, his voice discreetly retires. It recurs only twice before he and his now-dead soldier son faintly enter to watch the family welcome their new member, Marcus’s pal Toby.

“You see, Marcus, the ending is only the beginning.” Matthew’s address to us has become piece of fatherly advice.

The dead narrator of The Human Comedy never intervenes in the action on earth, but an all-seeing intelligence exercises more authority in The Seventh Cross (1944). Seven prisoners escape from a concentration camp, and Ernst Wallau’s narration launches the film. During the escape sequence he rapidly introduces each of his comrades.

Fairly soon all but one are captured and executed on crosses planted in the prison yard. The first man to be crucified is Wallau, our narrator. After he is killed, his voice-over continues: “I was dead. I could see.”

Wallau’s commentary chiefly follows his friend George Heisler, who manages to elude the Gestapo while the other escapees are found and killed. Wallau’s narration continues through the film, chronicling not only the fates of the other men but probing Heisler’s state of mind. Wallau tells us what Heisler is thinking, guides us into his memory, notes things that Heisler has forgotten, and even informs us what other characters will do in the future. Confronted with this numb, almost mute character, we need the continual commentary of Wallau to give access to his inner life.

Wallau is that rare voice-over narrator who flaunts his omniscience. Being dead, he has total access to our world and can witness anything happening there. Despite Wallau’s godlike power, in good Hollywood tradition his narration attaches itself chiefly to Heisler. But here that restriction reflects simply Wallau’s foreknowledge, signaled at the start, that only Heisler will survive. The question becomes: How?

The answer comes through Wallau’s goading Heisler to find faith in others. At the start, Heisler is close to despair, and his flight stems from sheer instinctual survival. At the film’s midpoint, all his comrades have been killed, and Wallau’s long-term escape plan has failed. Heisler can’t any longer mechanically follow his mentor’s instructions. He must forge a new goal, seize the initiative, and learn to trust people. He must learn what Wallau told him from the start: there remain traces of humanity in Germany.

As Heisler’s hopes grow and his network of allies expands, Wallau’s prodding voice-over subsides. It reappears near the end, at the moment Heisler realizes how much he owes others. Heisler speaks of his debts, and Wallau murmurs in antiphony the names of those who have helped him, including some Heisler has never met.

Now that Heisler has joined the struggle with full commitment, Wallau can vanish. “Goodbye, George Heisler. I can leave you now.”

Ghostly narrators like Wallau and Matthew Macauley call to mind the nosy angels and spooks of so many 40s films. Those have their counterparts in radio dramas like “Good Ghost” (1948) and the parodic mystery novel Dead to the World (1947), with a dead detective narrating his efforts to solve a case.

As usual, a lot depends on timing of information. If we learn that the narrator is dead at the start, as in the films just mentioned and in Scared to Death (1947), a certain amount of the action can seem foreordained. Alternatively, there can be a surprise. Radio plays, it seems, tended to reveal their dead narrators as a twist ending. With less fanfare, a film can simply seem to forget the opening commentary. The Gangster (1947) is initially narrated, without a frame situation, by the crooked protagonist. As a result, we expect him to survive. Yet he dies in the course of the action. The filmmakers faced a problem: To return to the narration at the end or not? To revive his voice-over might suggest that he endures in some supernatural realm. Instead, an impersonal external voice takes over to balance the opening.

With the convention of the dead narrator in place, a film could flirt with the possibility that the initial voice we hear has no living source. The opening credits of Woman in Hiding (1950) strongly suggest that a betrayed wife, racing down a hillside at night before crashing over an embankment into a river, has been killed. Her commentary rises up during a scene of the police dragging the river, and she seems to be mocking her husband from beyond the grave.

Is this a female variant of Joe Gillis’ voice-over? Watch the whole movie to find out.

In the same year as Woman in Hiding, Sunset Boulevard gave us another voice from the Beyond. If the film’s technique seems less original coming after a string of dead narrators, at least it can be credited with making the narrator the protagonist (unlike The Human Comedy and The Seventh Cross) and for using the device in a full-blown A picture (unlike Scared to Death and The Gangster).

In sum, the dead-narrator technique became a schema, a pattern which filmmakers could simply copy, as in Scared to Death, or tweak, as in the apparently dead narrator of Woman in Hiding. Wilder offered his own variant on the schema. We tend to remember his as the prime example, maybe even as the first one. But it often happens in the 1940s that the originality of a noteworthy film stems from a revision of a schema that was already in circulation, not only in film but in other media.

The weekend Laura died

Occasionally, the variety of options at the period sets up more dissonant relations. Laura (1944) is probably the most famous example.

Vera Caspary’s original book is divided principally into first-person blocks recounted by bon vivant Waldo Lydecker, detective Mark McPherson, and magazine editor Laura Hunt. Early versions of the screenplay attempted to capture multiple-viewpoint narration through flashbacks and voice-overs. What happened to this structure, however, reveals a process we’ll encounter elsewhere: fiddling with the film in post-production yielded some startling, perhaps unintended novelties.

Laura Hunt has apparently been murdered by a shotgun blast to the face. When the film starts, McPherson is calling on her mentor Waldo Lydecker, an effete columnist and radio commentator. McPherson lets Waldo accompany him on his inquiries before the two retire for a dinner at the restaurant Laura loved. There, via flashbacks and voice-overs, Lydecker recounts Laura’s rise to prominence. (In a scene cut from the final film, there’s an indication that Waldo’s tale is partly false—an early instance of a lying flashback.) The other characters’ flashbacks and voice-overs were abandoned in production, so the rest of the film is rendered objectively.

We later learn that the original victim was not Laura, which makes Laura either a new suspect or a target for the killer’s second try. At the climax, it’s revealed that Waldo is the culprit; he concealed the gun in an antique clock that he had given Laura. While his pre-recorded program is broadcast, he returns to her apartment and tries to kill her. Laura eludes him and as he wildly fires his gun, he is shot by McPherson’s team.

What makes the finale curious is the film’s framing device. The first scene starts with Waldo’s voice-over: “I shall never forget the weekend Laura died.”

This appears to cast the entire film as a flashback, starting with McPherson’s visit to Waldo. Within that flashback to the weekend, we have further flashbacks–that is, Waldo’s dinner-table explanations to McPherson. Such Russian-doll embedding is found elsewhere during the 1940s. At the end of the evening, when Waldo leaves, the camera lingers on McPherson and we become attached to him for nearly all that follows.

In screenplay drafts, this last shot would have initiated Mark’s voice-over narration, which would constitute a chunk parallel to Waldo’s. This is further evidence that Waldo’s string of flashbacks, including his opening voice-over, functions to write finis to “his” section of the film. But in the finished film, without McPherson’s voice-over block, Waldo’s initial voice-over hangs there, apparently framing the whole film. It would have been easy simply to cut that commentary and retain the opening camera movement revealing McPherson browsing among Waldo’s treasures, perhaps with some more nondiegetic music. Then Waldo’s offscreen admonition would bring in his voice for the first time. After this, Waldo’s later flashbacks and his voice-over narration would become neatly nested and perfectly conventional.

Clearly, decision-makers wanted to retain Waldo’s ripe commentary to open the film; it has expository value, and it introduces a very intriguing character. But we don’t hear that enveloping voice again, so for the rest of the film we might take Waldo’s remarks as akin to those that open Rebecca (1940) or Flamingo Road (1949). In these films and many others, a reminiscing character voice introduces the story action from an unspecified point in time and space. And the plot’s shift to McPherson’s activities seems to suggest that the whole opening stretch, including Waldo’s initial recounting, should be taken as a unit, “his” section of the film. So when Waldo is shot down and starts to die, we might have a situation like that of The Gangster, where the narrator is killed in the course of the action he introduced, and the film forgets what started it all.

Instead, Laura takes the option that The Gangster avoided: it brings back the dead man’s voice. After Waldo collapses, there’s a cut to McPherson and Laura leaving the frame. As the camera moves in on the shattered clock face, we hear, “Goodbye, Laura. Goodbye, my love.”

The line might be taken as Waldo’s dying words spoken offscreen, except that the line is miked far more closely than his speech earlier in the scene, when he’s actually closer to he camera. In its acoustic texture, this unsituated sign-off formally balances the unsituated opening. But it also raises the possibility that the dead Waldo has launched the whole story and now bids Laura farewell from that realm wherein defunct narrators dwell.

The opening does hint that something otherworldly is going on. A tart, suave voice wells up from sheer darkness, perhaps a noir equivalent to the sunny eternity from which Matthew Macauley speaks in The Human Comedy. Yet for a dead narrator, Waldo is either ill-informed or misleading. He speaks of “the weekend Laura died.” But if he lived through the events of the film, he knows that she did not die. Of course, his fib helps the film mislead us; the first half presupposes that Laura was the victim. If we remember that an unused scene was going to reveal that his flashback tales to McPherson contained lies, we may conclude that Waldo is as unreliable in death as he was in life.

Some of these inconsistencies apparently spring from late decisions in production. The original ending, as scripted and shot, lets Waldo survive. As he’s led off, he says, “Thank you for everything, my dear. . . You’re all I’ll be thinking of—till Time stands still—for me. Goodbye, Laura.” The speech is heard offscreen as the camera pans and holds on the clock.

Fox production head Darryl F. Zanuck was dissatisfied with many aspects of this conclusion and so a new version was filmed. In that version, Waldo is shot and dying. We see him speak the same lines, and only then does the camera pan to the clock. The release version, with Waldo’s simpler, closely miked farewell over the shot of the clock, was evidently decided on still later.

For what it’s worth, both the original shooting script and the revision distinguish between lines marked as “WALDO (narrating)” and “WALDO’s voice” for offscreen delivery. In neither version are Waldo’s dying lines marked as “narrating.” And in neither do we get an indication of the final camera movement that lets Laura and McPherson leave the shot in order to target the shattered clock face. Yet we do have a sonic texture in the last lines that is closer to a narrator’s voice.

In sum, while presenting a haunting conclusion—the clock was Waldo’s gift to Laura, and the shattered face recalls his first victim—the soundtrack firmly reminds us of the opening. Do we have a dead narrator? Some cues are there, but they’re sketchier than those in other films of the era. (For one thing, in those films, the narrator tells us he or she is dead.)

The unexplained return of Waldo’s voice, now gentle, has a surprising poignancy. Because of its loose ends, the final moments become more evocative, and more poetically enticing, than the tidy, explicit wrapup of Sunset Boulevard. In such ways, Laura’s final moments provide an eccentric revision of the dead-narrator schema. The result may have encouraged filmmakers who followed to risk inconsistency for the sake of powerful immediate effects.

In an earlier entry, I traced how studio pressures made the narration of Preston Sturges’ The Great Moment oddly off-balance. Evidently something like this happened with Laura. In the pressure to get a film finished and out the door, to retain striking bits that may ultimately not make sense when put together, Hollywood filmmakers can innovate by accident.

Dead men tell no tales

Auto Focus (2002).

Once the dead-narrator schema was available, Forties filmmakers were able to tweak it in various ways. And the changes didn’t end then. To see how the same process of schema and revision has continued, consider three much more recent examples.

Paul Schrader’s Auto Focus is a straightforward case. Bob Crane’s voice-over appears early in the film, though not at the very start, and recurs six times before the final scene. The brief comments punctuate Crane’s career decline and his descent into sex addiction. As happens with The Seventh Cross and other films using voice-over narrators, the second half employs the device less intensively than does the first. It’s as if in a film’s Development section we’re expected to be absorbed enough in the action not to need explanation, and we’re sufficiently primed to know what the important issues are.

When Crane’s head is bashed in by his companion in sexual buccaneering, we have a case comparable to The Gangster: the narrator doesn’t survive. Crane’s voice has been silent for 28 minutes, so we might assume that we’ve lost his voice-over. But it returns over his bloody body, recounting in an offhand way the aftermath of his death. His voice remains as perky as it has been early in the film, in both his commentary and his explanations to his wives. “I’m a normal guy,” he has insisted, and his bland wrapup shows him insouciantly unaware of the implications of living and dying as he did. He can’t condemn his killer. “He was a cool guy in his way. . . . Men gotta have fun.”

Martin Scorsese’s Casino (1995) reworks the dead-narrator schema in more complicated ways, in the process borrowing other 40s conventions. During that period, multiple-narrator films became quite common. Again we have a prototype—Citizen Kane (1941)—but again it wasn’t alone. Trial films featuring flashbacks that dramatize testimony had become fairly common in the 1930s, and a couple of detective films (e.g., Affairs of a Gentleman, 1934; Thru Different Eyes, 1942) used flashbacks to present different witnesses’ versions of events. It would become a staple of crime films like The Killers (1946). Julien Duvivier’s Lydia (1941) transposed the multiple-narrator technique to the melodrama, while The Affairs of Susan (1945) applied it to romantic comedy. Mankiewicz, who seems quite obsessed with the strategy, deployed it in A Letter to Three Wives (1949), All about Eve (1950), and The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

A less common 1940s convention is the replay—the passage that repeats a scene, usually in flashback and usually including information not shown in the first pass. The most famous example is Mildred Pierce (1945), which I’ve fretted at for years (in this entry and this video). We can find less crucial replays in, again, Kane (Susan’s opera debut) and in more obscure films like Beyond Glory (1948).

Casino draws on the replay and the multiple-narrator format and blends them with the dead-narrator one. The film innovates in a couple of striking ways. First, in 1940s multiple-narrator films, the individual narrations are presented in blocks; a solid chunk from one voice, another from another. True, we see some leakage in All about Eve, but basically the narrators’ tales are kept distinct. Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi’s script for Casino hops between two principal narrators, Ace Rothstein (Robert de Niro) and Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci).

Ace and Nicky’s voice-overs are mostly very brief, tagging a cascade of episodes tracing each man’s rise in Vegas, with equally fleeting flashbacks to their origins. The first twenty minutes toggles ten times between the two men’s clipped commentaries. This stretch constitutes a sort of training session, preparing us for the rapid switches in viewpoint that will dominate the film. Again, though, the voice-overs will subside for stretches in the middle, when the scenes become more fully developed. As a momentary, almost twitchy variant we get one extra voice-over—that of a go-between who, in a freeze frame, decides not to tell the mob boss about Nicky’s betrayal of Ace. Significantly, the film’s third major character, Ginger McKenna (Sharon Stone), is allotted no voice-overs.

So Scorsese and Pileggi have fractured the 1940s voice-over schema. But the to-and-fro commentaries I’ve mentioned come after an opening sequence that seems to announce that one of these wise guys is already dead. The first scene shows Ace being blasted out of his car by a bomb. A sprawling body, as if ejected from the explosion, floats through the opening credits. And Ace’s next voice-over launches the film’s cascade of flashbacks by saying they come from the period “before I got myself blown up.” We seem to be in the full-fledged presence of a dead narrator.

We are, but it’s not Ace. At the film’s climax, it will be Nicky who dies at the hands of his own crew. In replays of the car explosion, it’s revealed that Ace actually survived the blast. By 1995 Scorsese and Pileggi could revise the 1940s schema by splitting the narrators and misdirecting our expectations: the apparently living narrator is the one who will die.

What, finally, of Confidence? Jake’s admission that he’s dead fits snugly into the tradition we’re considering, especially since it’s a voice-over initiating a flashback. That flashback takes us to the moments before his execution at the hand of the triggerman Travis.

In those moments Jake explains how his team of grifters accidentally took money belonging to a gang boss and how they proposed to repay him with an even bigger con job. That central story action, itself peppered with backstory exposition, is interrupted by returns to the opening execution situation. Jake’s first voice-over, apparently addressed to us, is differentiated by sonic texture from his explanations to Travis, but when his voice leads us to the past, it has the same degree of auditory presence. In effect, it’s the same confusion of narrating levels that’s promoted in the first long stretch of Laura.

At the climax of Confidence, we see Jake shot not by Travis but by the moll Lily. Travis flees, and so does she. Now we’re back to the opening situation, and a replay of Jake’s opening line, “So, I’m dead.” He seems to sign off. But now more flashbacks reveal that Jake and Lily have staged her gunplay and that the whole scheme has been a very long con. The team reunites and goes off with their millions. Confidence has appealed to our knowledge of the dead-narrator convention to fake us out: the story action won’t end with his death because he’s stage-managed it.

Jake lied about being dead. But so did Ace when he referred to being “blown up.” So did Waldo, maybe. And so do those films that don’t signal that the protagonist has fallen into a dream or a reverie. Actually, narratives are incorrigibly deceptive and full of secrets. You can’t even trust dead guys.

As ever, we’re reminded that modern filmmakers inherit a vast tradition of narrative schemas. Those can be reiterated or revised in unpredictable ways. The tradition is kept alive and engaging, as long as novelty is balanced with familiarity, innovation with redundancy. (Let the narrators explain, throw in some replays,) The way Hollywoood tells it is always indebted to the ways Hollywood told it.

For more examples of dead narrators see the Wikipedia entry and TV Tropes. Long as they are, these lists tilt heavily toward contemporary examples, where posthumous narration seems very common. One reason I posted this entry was to acknowledge older instances of this convention.

Ray Collins was a well-known radio voice as well as a Welles Mercury player. As both Matthew Macauley and Wallau, he seems to have been the go-to man for reliable supernatural voice-over. He had a long Hollywood career, but most baby boomers remember him best as Lieutenant Tragg in the Perry Mason TV show.

I’m indebted to Neil Verma for information about the posthumous narrator in radio plays. Neil also mentions “The Hitch-Hiker” (1942), and these episodes of Quiet, Please: “Inquest” (1947), “In Memory of Bernadine” (1947), “Anonymous” (1948), and “I Always Marry Juliet” (1948). (Listen to any of these here.) Filmgoers probably encountered more dead narrators on radio than on film. Neil’s book, Theater of the Mind, is an excellent account of 1930s and 1940s radio narrative.

The shooting script of Laura is available here. The revised ending is included as well. See also the detailed comparison of the two endings by Despina Veneti at Preminger Noir. The first analysis of the different versions was, I believe, carried out by Jacques Lourcelles in “Laura: Scénario d’un scenario,” L’Avant-scène du cinéma no 211/212 (July-September 1978), 5-11. This publication includes a French-language transcript of the film as we have it, along with cut portions. A detailed account of Laura’s production is provided by Chris Fujiwara in The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (Faber and Faber, 2008), pp. 36-48. I’m grateful to Jeff Smith for his advice about the sonic texture of Waldo’s voice-over.

The narrational issues raised by Laura go beyond the deceased Waldo’s voice. In the film’s most famous scene, McPherson is becoming obsessed with the dead Laura and, after drinking heavily, he falls asleep in her apartment. The camera tracks slowly in on him as he drops off. There’s the noise of a door from offscreen, and Laura walks in. McPherson is astonished. Laura, released the same week as The Woman in the Window, might seem to be hinting that Laura has been revived in McPherson’s dream.

Kristin has traced the numerous dialogue motifs that reinforce this possibility. Yet most films of the 1940s mark a dream sequence very explicitly (e.g., wavy superimposed lines, dissonant music) or at the least with a dissolve and a close-up or track-in reinforcing the shift to subjectivity. Laura provides only two cues, the sleeping character and the track-in. But as Kristin indicates, these and other factors keep the dream option a possibility for a first-time viewer. See “Closure within a Dream? Point of View in Laura,” Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988), 162-194. Kristin’s essay also offers a comprehensive discussion of the shifts in Waldo’s narration.

The presence of dead narrators would seem to pose a problem for those scholars who believe that in a movie every narrator must have a narratee on the same logical level. For these theorists, film narrators are part of a symmetrical system of communication among personified entities. Those entities are either embodied in the text (McPherson is Waldo’s narratee in the restaurant) or implicit in the very logic of narrative itself. No narrator without a narratee! According to this line of argument, there must be a narratee as dead as Waldo listening to his opening voice-over, but being very, very quiet.

In contrast, I’ve argued that films, and possibly all narratives, are freewheeling and illogical in their use of markers of communication. Films may mimic only parts of a communicative circuit in order to achieve specific effects. In provoking experiences in readers, films seem to me to rely on psychology, not ontology. I float this argument in this chapter of Poetics of Cinema. See also this blog entry.

Earlier entries have touches on the schema-and-revision dynamic of style and story in Hollywood. See for examples my discussion of 1913 films, a consideration of 1940s style, some remarks on walk and talk, a piece on high-school lipdubs, a discussion of replays, and the entry on Gone Girl. Searching “schema” will bring up more. A roundup of entries on peculiar 1940s narratives is here. I analyze narration in All about Eve here. For more on the debt of modern film to 1940s innovations, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Casino.

How he (mostly) got away with it: Matthew H. Bernstein on Preston Sturges

DB here:

Matthew H. Bernstein is a long-time friend and a superb scholar. His biography of Walter Wanger has become a classic of Hollywood business history, and his many books and articles have refined our sense of American cinema. When we learned of his research into Sturges (a favorite of this blog), we were happy to propose that he do a guest entry. Here’s the lively, trailblazing result.

How should films portray sex and marriage? Hollywood’s Production Code, established in 1930, set forth some definite ideas.

Sex

The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing. . . .

Scenes of Passion

They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown . . .

Seduction or Rape

They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

They are never the proper subject for comedy.

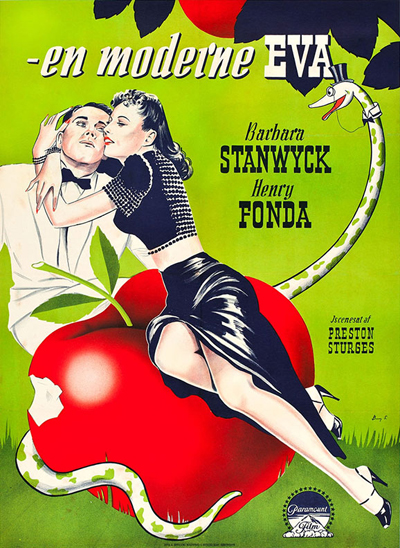

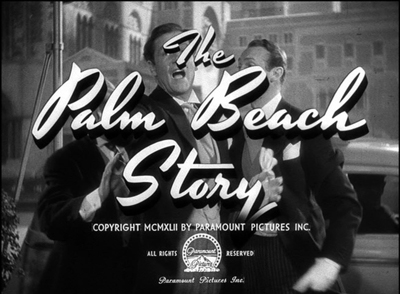

Those of us who savor Preston Sturges’s great romantic comedies of the 1940s—The Lady Eve (1940), The Palm Beach Story (1942) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944)—admire them in part for their violation of just about all these tenets. They are full of “suggestive postures” like the lengthy chaise longue scene in The Lady Eve. Their central topic is often the seduction of men by women (The Lady Eve, The Palm Beach Story and arguably Miracle). References to extra-marital sex, contemplated or accomplished, abound. And all three films ridicule “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” into the ground. Film critic Elliot Rubinstein once observed, “If Sturges’s scenarios don’t quite invade the province of the flatly censorable, they surely assault the border outposts, and some of the lines escalate the assault into bombardment.”

The Production Code Administration, on paper and in practice, was particularly obsessed with regulating the depiction of female sexuality on screen. Yet Sturges’ attacks on conventional morality are launched by heroines: con artist/card sharp Jean/Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve, the hard-headed Gerry Jeffers (Claudette Colbert) in The Palm Beach Story and the naïve man-bait Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. They are all variants of what Kathleen Rowe has called the “unruly woman,” characters who create “disorder by dominating, or trying to dominate, men,” and being “unable or unwilling” to stay in a woman’s traditional place. Mary Astor’s much-married Princess Centimilia/Maude in The Palm Beach Story deserves an honorable mention here too.

True, by each film’s conclusion, the Sturges heroine agrees to get or stay married. She fulfills the conventions of romantic comedy and the stipulations of the PCA. Yet in each film the path to a proper end looks so much like a roller-coaster ride that the significance and sanctity of marriage come to seem ridiculous.

How did Sturges get away with so much? A look behind the scenes at the negotiations around The Lady Eve can help us understand his strategies. It also shows that the Code was more flexible and fallible than we often realize.

Convolutions in the Code

Sturges had one advantage at the outset. He worked in a genre that was already testing the limits of the Code. Granted, the PCA in 1934 aimed to regulate film content in every genre. None, however, flaunted, even parodied, the strictures of the Code more thoroughly than screwball comedy did. Rubinstein puts it well: “The very style of screwball, the complexity and inventiveness and wit of its detours around certain facts of certain lives, the force of its attack on the very pieties it is pledged to sustain, cannot be explained without recognition of the censors. Screwball comedy is censored comedy.“

By the end of the 1930s, filmmakers were pushing hard against censorship. Romantic comedies were growing more risqué by the month, as shown by 1940 releases like My Little Chickadee, The Philadelphia Story, The Road to Singapore, Too Many Husbands, The Primrose Path, Strange Cargo, and most especially, This Thing Called Love. A sort of arms race took place, and Sturges, emerging as a writer-director in 1940, benefited from this escalation.

Just as important is a fact that many fans of Hollywood still don’t realize. We like to think that daring filmmakers were charging boldly against an iron wall, with chief censor Joseph Breen and his associates setting forth implacable demands. But the administration of the Code was not a mechanical, totalitarian affair. It was most often a matter of negotiation.

Releasing Hollywood’s product, even risqué films, benefited all parties involved. If the Code were enforced with absolute rigidity, the industry would suffer. Some films would have to be abandoned. Then urban audiences would have found the safely released product pallid, and critics would have complained about bland output. Then as now, edginess sold, and at least some audiences were eager for it.

Accordingly, Breen and co. recognized that the Code could not be applied ruthlessly. Indeed, historians Lea Jacobs, Richard Maltby and Ruth Vasey have shown that the PCA, like its forerunner the Studio Relations Committee, often helped filmmakers find ways around the most stringent policy demands. Through a give-and-take, censors and filmmakers could settle on scenes and lines of dialogue that could avoid public outcry. No one flaunted and taunted the PCA as well as Sturges, yet Breen and co. often helped him find ways of rendering suggestive situations without baldly transgressing the Code.

One typical filmmaker/PCA tactic that favored Sturges was an appeal to ambiguity. Far from being inflexible, the staff recognized that not every viewer picked up on a lewd line or suggestive situation. Some viewers would find no innuendo in a sexually-charged scene. (The 1940s critic Parker Tyler referred to this as “the Morality of the Single Instance.”) For example, in The Lady Eve, there’s a fade-out from Charles’s and Jean’s passionate embrace in the bow of the ship at night to the fade in of the ship’s prow slicing through the ocean the next morning.

That passage would suggest to the naïve viewer that they kissed for a while and went to their cabins separately. After all, in the morning we find Jean getting dressed in her stateroom and talking with her father. Then we see Charles on deck alone, waiting for Jean.

But the sophisticated viewer would understand that the earlier fade-out indicated what Joseph Breen routinely called “a sex affair.” (The ocean spray on the fade-in could be seen as a very subtle extra touch.) Crucially, Jean’s later statement to Hopsy after she is unmasked as a cardsharp sustains both readings. “I’m glad you got the picture this morning instead of last night, if that means anything to you . . . it should.” When self-regulation was well-calibrated—and this was a moment-to- moment, scene-by-sceene, film-by-film achievement—there was wiggle-room that would let innocent viewers remain innocent while letting sophisticated viewers feel sophisticated.

Apart from the increasing eroticism in screwball comedy and the willingness of the PCA to work with filmmakers to allow double layers of meaning, Sturges benefited from good timing. During this period, Breen grew more permissive in his application of the Code. He never explained why, but the late-1930s bombardment of questionable material was probably one cause. Breen was pretty exhausted after seven years of trying to accommodate the filmmakers’ increasingly outré ideas. He was so tired that he temporarily resigned in Spring 1941.

Sturges’ circumvention of the Code also depended on his personal qualities. Clearly he was a persuasive negotiator. The PCA correspondence shows Breen and his successor, Geoffrey Shurlock, rescinding countless directives they initially gave him to eliminate dialogue lines or bits of action. It’s likely that the PCA admired Sturges’ comic gifts and thus gave him greater room to maneuver than other directors enjoyed. (Much the same thing happened when the Studio Relations Committee had given leeway to Ernst Lubitsch prior to 1934.) Sturges also employed a tactic of overkill. In his scripts and in the scenes as finally staged and shot, he created so many potential infractions of the Code that to challenge each one would reduce the film to rubble, or reduce Breen and co. to stress-induced madness.

Still, Sturges played the PCA game. His convoluted plots stuck to the letter of the Code, always finally coming down on the side of pure romance and happy marriage. But they wreaked havoc with its spirit—often with the PCA’s sanction. By the premiere of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Sturges was relentlessly mocking the PCA’s regulations. It’s likely, I think, that the PCA was for the most part in on the joke.

After negotiations, which grew more elaborate with each title, each Sturges romantic comedy received a seal. The films made it through partly because of the PCA’s quixotic mandate, partly because the Code’s requirements had been loosened, and partly because of Sturges’ extraordinary skill in exploiting the Code. These are the crucial reasons Sturges got away with it. Along with his prolific comedic imagination, he was often aided by the very body that was supposed to be censoring him.

Once the Sturges film was released, the PCA staffers could wearily pat themselves on the back for a job well done. Yet critics’ reviews, complaints from state censor boards, and letters of protest from ordinary viewers indicate that the agency often badly misjudged how the films’ moral tone would be received. The PCA’s dual mandate—to try to give filmmakers the maximum freedom to create risqué situations but at the same time to uphold the Code–was a tightrope walk. With Sturges and other filmmakers, the agency lost its balance. Sometimes the PCA didn’t diminish the sexual dimensions enough, and sometimes the agency did not even notice elements that could give offense.

There were signs already, in the reaction to the 1940 burst of sexier films like The Primrose Path and This Thing Called Love. Local informants had asked MPPDA attorney Charles C. Pettijohn, “Doesn’t Mr. Hays have any influence with the producers any more, and has that fellow Breen out there killed himself or has he just been compelled to walk the gangplank?” Unlike the PCA staff, who had worked day by day to tone down an audacious script and had faced the charms of a persuasive filmmaker, local censorship boards reacted solely to a finished Sturges film. They merely saw what was on the screen. Many did not like what they saw.

Up the Amazon for a year

The PCA correspondence concerning The Lady Eve is surprisingly brief. Before the film was completed and a seal was granted, Breen sent only two letters to Luigi Luraschi, Paramount’s liaison on censorship. They strikingly illustrate how cooperative Breen could be when it came to scenes regarding illicit sex.

When he read Sturges’s first complete script of 7 October 1940, Breen had objections to many “questionable lines of dialogue.” Breen warned Sturges and Luraschi against anything “suggestive” in the scene between Muggsy and Lulu as they say their farewells before departing the expedition. In this brief exchange, Mugsy stiffly tells her “So long, Lulu…I’ll send you a post card” as she demurely (looking down) places a lei over his neck. This brief exchange directly undercuts Hopsy’s just-spoken, high-minded farewell to the Professor: “This is the way I’d like to spend all my time…in the company of men like yourselves…in the pursuit of knowledge.”

While it’s difficult to imagine Muggsy as a sexual partner to anyone, the woman’s downcast face and her gift of a lei could be seen to suggest her heartbreak.

Jean’s later, rapid-fire description of Hopsy’s many female admirers in the Main Dining Room of the S.S. Southern Queen originally contained comments about women who were “a little flat in the front” or “a little flat behind. ” These were cut because they were too physiologically specific about the female form. We hardly miss them, as Jean was permitted to deliver plenty of color commentary, as she detailed the women’s futile attempts to attract Hopsy’s attention.

However, Breen wrote the word “in” alongside certain demands he had made for eliminations in his 9 October letter, indicating that Sturges and Luraschi had persuaded him to relent. For example, Breen eventually accepted this exchange from Jean and Charles’s first evening together. Charles has suggested they go dancing:

Jean: Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?

Charles (after a pause): You’re certainly a funny girl for anyone to meet who’s just been up the Amazon for a year.

Jean: (after a pause): Good thing you weren’t up there two years.

Breen’s next letter (21 October) on Sturges’s revised script expressed satisfaction with all the changes made, noting that Jean’s line about heading to bed “will be delivered without any suggestive inference, or reaction.”

In the finished film, there is nothing arch about Stanwyck’s thoughtful, almost parental delivery of the first line, spoken as she looks straight ahead and then looks down to stub out her cigarette before she turns to face Charles. Likewise, her delivery of the second line is wry and mildly mocking yet almost compassionate. Still, the connotation remains that Jean is suggesting they sleep together. Instead, the couple proceeds to Charles’s cabin to meet his snake Emma.

Breen was particularly concerned about other allusive dialogue. At the Pikes’ party, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore) explains to Charles a fictionalized version of Jean’s family history which resulted in the existence of two sisters, one a lady, one a cardsharp. (Sir Alfred will later describe this as “Cecilia or the Coachman’s daughter, a gaslight melodrama.”) Breen insisted that Sir Alfred’s tale include a line indicating that Jean’s mother divorced her elderly earl before taking up with the groom “Handsome Harry” and giving birth to Jean. That way Jean’s birth would not seem illegitimate. Sturges obliged. Yet he somehow persuaded Breen to retain this later portion of the Alfred-Charles exchange, also alluding to an adulterous affair.

Charles: They [Jean and Eve] look exactly alike!

Sir Alfred: We must close our minds to that fact…as it brings up the dreadful and thoroughly unfounded suspicion that we must carry to our tombs, you understand…as it is absolutely untenable…that the coachman, in both instances…need I say more?

Why did Breen let Sturges keep in this suggestion that Handsome Harry was the biological father of both sisters, perhaps as the result of adulterous affairs? It is hard to say. True, the offending line concerns a “suspicion” voiced by Sir Alfred, rather than a fact. But Charles immediately affirms its likelihood: “But he did, I mean, he was, I mean…” before being shushed for the nth time by Sir Alfred. Here again, Breen consented to Sturges’s use of questionable material.

Breen’s greatest objection in his initial letter concerned pp. 70-74 of the first submitted script, which suggested “a sex affair.” “Inasmuch as this is treated without the proper compensating moral values, it is in violation of the Production Code, and will have to be eliminated entirely from your finished picture.”

The offending pages outlined a scene between Charles and Jean set on the deck of Jean’s cabin at the end of their first evening together. Just previously, Jean has caught Charles and her father the Colonel (Charles Coburn) playing double or nothing. Charles would then be called away to receive from the ship’s purser the incriminating photo of Jean, the Colonel and Gerald. Charles would then return to the gaming room table and the dialogue exchange with Jean about all women being adventuresses. Then Charles would ask Jean if they can go down to her cabin. There, Charles lights Jean’s cigarette; he “struggles to say something” but Jean tells him, “Kiss me,” and he obeys. (“He crushes her in his arms” as she “sinks back against the chaise longue.”) The film would then cut to a shot of the rail of Jean’s deck and of “the moonlit water beyond. A lighted cigarette arcs over the rail and down into the water. FADE OUT.”

This version presents Charles sleeping with Jean even though he knows from the purser’s photograph that she’s a cardsharp. As Brian Henderson notes, this arrangement of events would make Charles a cad, far worse than the hypocritical prig that he is in the finished film. Sturges eventually solved the problem by having Charles learn of Jean’s duplicity on the morning of their third day together at sea. But before Sturges made this change, Breen’s October 9 letter directed that Charles could not speak the line about going down to her cabin; that the scene could not play out on Jean’s private deck; and that “it would be better to have the embrace with the couple standing up.” The shot of the cigarette thrown over the railing also “should be omitted, on account of its connotations.”

In response, Sturges watered down the offending scene of passion and relocated it to the bow of the ship, where (in a reworking of a scene he had always envisioned) Charles recites his “I’ve always loved you” speech and they eventually embrace as the scene fades out. This created the PCA-approved ambiguity about what transpired sexually between them.

Here, Sturges’s solution to a problem of plot and characterization went hand in hand with the double-meaning practices of the Production Code. Sturges must have written the passionate private deck scene knowing full well that Breen would demand its elimination or transposition. His immediate agreement to revise it was likely a bargaining ploy to earn Breen’s goodwill to bank against other PCA objections.

When Sturges cut the cabin deck setting and the prone postures of pp. 70-74 from the first submitted script, he also saved a crucial part of Jean and Charles’s penultimate exchange as they enter Jean’s cabin.

Charles: Will you forgive me?

Jean: For what? Oh, you mean…on the boat…the question is, will you forgive me?

Although Breen accurately predicted that this bit of dialogue would “probably be acceptable” if the earlier scene “is cleaned up,” for now, Breen stated that their exchange had to be cut “by reason of its reference to the aforementioned sex affair.” In other words, Breen, not unreasonably, read Jean and Charles’s dialogue as referring only to their sleeping together, rather than to everything that transpired between them on the S.S. Southern Queen, including Jean’s duplicity and Charles’s narrow-mindedness. Forgiveness is of course a key issue in the drama of The Lady Eve.

Hix Nix Sexy Pix

The MPPDA issued its seal on 26 December 1940. Released in mid-March 1941, The Lady Eve passed the censors without cuts in Chicago and the states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. However, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania were a completely different story.

Some local censors demanded deletions of elements Breen had highlighted. Ohio and other localities objected to Sir Alfred’s dialogue about the fantasy fatherhood of Jean and Eve (“as it is utterly untenable that the coachman in both instances. . . .”). But most of the eliminations concerned elements Breen and his team had not commented upon. Among these were (again for Ohio, initially) Sir Alfred’s summary recap of the tale to Jean the next morning: “So I filled him full of handsome coachmen, elderly Earls, — young wives, and the two little girls who looked exactly alike.”

Other targets were Jean’s wisecracks. When Jean and Charles return from her stateroom after changing her shoes, the Colonel archly comments, “Well, you certainly took long enough to come back in the same outfit.” Jean’s reply–“I’m lucky to have this on. Mr. Pike has been up a river for a year”—offended Pennsylvania. Ohio objected to Jean’s comment, “That’s a new one, isn’t it?”, when Charles invites her into his cabin to see Emma.

Yet another instance concerned Charles’s exchange with Eve during their wedding night train ride. He is asking about her previous marriage to Angus.

Charles: When they brought you back, it was before nightfall, I trust.

Jean: Oh, no.

Charles: You were out all night?

Jean: Oh, my dear, it took them weeks to find us. You see, we’d make up different names at the different inns we stayed at.

Though Jean and Angus were married, the implication of using false names at a hotel (which Sturges would recycle for Trudy and her unknown husband in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek) was the deal-breaker for Ohio. Of course, one possible connotation of Eve’s many pre-Charles couplings is that not all of them were marriages. (If they were, this imaginary Eve is an early version of the Princess in The Palm Beach Story, another figure who satirizes conventional marriage.) Yet Breen’s only comments on this scene concerned Eve’s nightgown and particularly the scene’s blocking—that Eve’s revelations of her previous marriages occur away from the bed and that the bed be deemphasized throughout the scene.

Sturges must have made the case that there was no room to have the actors sit elsewhere. Meanwhile, Breen was distracted from what Jean was saying by where she was when she said it.