Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Watch those hands; or, Burt, Jean-Luc, and Bill come to Cinephile Summer Camp

Nouvelle Vague (1990).

DB here:

At this year’s Summer Film College in Antwerp, Peter Bosma pointed out that the event seems to be a unique mixture.

Films are screened from morn to midnight: this time, 38 films across 6 days and two half-days. But it’s not exactly a film festival, as there are no new releases.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

Moreover, the films cluster around two or three major themes. This year we had Late Godard (fourteen titles, counting episodes of Histoire(s) du cinema) and the career of Burt Lancaster (eleven). In addition, there were nightly showcases called “Masterworks in Context,” which included one surprise film, title undisclosed. But unike most movie marathons, the Summer Film College introduces screenings with lectures and discussions. This year there were fourteen sessions, each running about ninety minutes. These are serious, intensely informative talks—very far from the usual brief introductions one gets at festivals or in art house warm-ups.

So is it an educational enterprise? Definitely, but without assignments, tests, or grades. It’s designed to serve Flemish-speaking professors and students, but also civilians who are just interested in a weeklong package of film and film talk. The event helps forge a community of film appreciation.

Finally, there’s often a guest filmmaker on hand, usually related to the main threads. This time it was Bill Forsyth, who directed Burt in Local Hero. That film was screened, along with Bill’s wonderful Housekeeping.

So what would you call the College? I once called it Cinephile Summer Camp, and that still seems accurate in evoking the sense of fun and camaraderie that pervade the place. We don’t all get mosquito bites, but after a week you come to enjoy seeing familiar faces and talking with them about what they’re seeing. Just as when you go to summer camp, you get to stay up late. But at no summer camp I ever attended did we drink so much beer.

JLG/SJ/DB

The principal speakers were Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers, who covered Burt, and Steven Jacobs on Late Godard. The Masterworks in Context shows were introduced by several guest speakers, including Lisa Colpaert (excellent on I Walked with a Zombie) and Vito Adriaensens (covering both Murder! and Vampyr). For Pollyanna, Bruno Mestdagh of the Cinematek staff explained the process of restoration. I played utility infielder, offering one talk on Burt and three on JLG.

How often do you get to see 35mm prints of Une femme mariée, Passion, Je vous salue Marie, Détective, JLG/JLG, Eloge de l’amour, and Nouvelle Vague? The Godard series, which ended with a 3D show of Adieu au langage, was a high point of my summer viewing. Back home I had prepared by rewatching all Godard’s features from Sauve qui peut (la vie) onward, but my video homework didn’t prepare me for the way the big screen amps up their prickly, seductive power.

I don’t speak or read Dutch, so I missed many subtleties in Steven Jacobs’ talks, but thanks to Power Point I could figure out the main points. Few lecturers can pack so much information and ideas into ninety minutes.

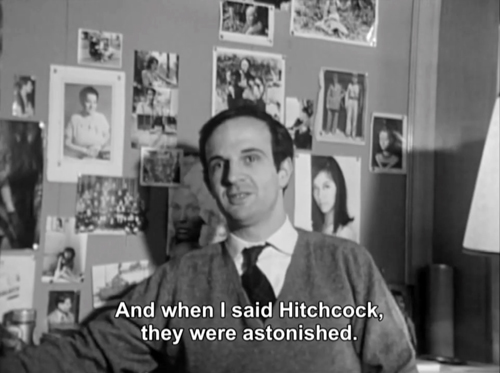

We had no way of knowing how familiar the audience was with Godard, early or middle or late, so Steven started with an orienting talk on JLG’s pre-1980 work (above). He swiftly reviewed key aspects of Godard’s New Wave period, traced his shift toward “a critical cinema” between 1967-1969, and explored the move into his Marxist phase. Along the way, he stressed the way cultural developments like auteur theory, Pop Art, Maoism, Brechtian theatre, and semiotics shaped Godard’s films. Particularly acute was his discussion of the “one image after another” sequence in Ici et ailleurs (1975). In all, the talk was an ideal prelude to Une femme mariée, which pointed up so many motifs of the later work: the focus on the couple, the emphasis on media-based images, and the persisting shadow of the Holocaust.

Steven is an art historian at University of Ghent; he earlier appeared on this blog as co-author of the imaginative book The Dark Galleries. After tracing Godard’s return to mainstream cinema and his move to Rolle, Switzerland, Steven focused on that splendid example of JLG the painter, Passion. Steven has written eloquently on the film in his Framing Pictures, and here he widened his focus to discuss its relation to other films centered on the tableau vivant, like Pasolini’s La Ricotta and Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting.

You’d expect that Steven would have a field day with Histoire(s) du cinema, and he did. Unlike most Godardophiles, I’m not wild about this series of video essays. I can’t take them as serious studies in film history, and too often I sense he’s just playing around. (Enough with the stroboscopic flashes, okay?) But Steven obliged me to rethink them by showing how they fit into the Postmodern art scene, especially the video art movement after the 1970s. He pointed out the central importance of the Hitchcock episode and the series’ constant concern with the Holocaust, often in dialogue with Shoah. Citing Godard’s claim that video taught him to see cinema in a new way, Steven suggests that the format also created a tenor of paradoxical melancholy. It’s as if JLG’s experiments with this new technology drove him to celebrate the death of the cinema he knew.

My three talks on Late Godard tried to ask something that I didn’t find many traces of in the literature. What are these films doing with (or against) narrative? I think that the focus on JLG as “film essayist” has sometimes obscured the fact that he has long insisted that he needs stories. Yet he seems to have no interest in the craft of storytelling as we understand it. He avoids dense exposition, careful foreshadowing, well-timed revelations, and cumulative climaxes. He tends to spoil the narrative expectations he sets up.

As a result, his plots—for his films have them—are distressingly opaque. Exactly what happens in a Late JLG film is often difficult to determine. I’m always surprised when discussions of these late films provide capsule plot summaries, for the very difficulty of arriving at these should claim our attention. As just one instance, many critics seeing Adieu au langage for the first time thought the film centered on one couple. It centers on two. But the fact of that mistake ought to interest us enormously: What in the film’s presentation made it difficult to follow the basic situation? Are there strategies Godard follows in creating his apparently willful obscurity?

Godard’s unique strategies of storytelling are carried down into felicities of visual and verbal style. Again, I think that critics haven’t sufficiently acknowledged just how strange and opaque the surfaces of these movies are. For one thing, characters are unidentifiable from scene to scene, thanks to camera setups that cut off their faces, wrap them in shadow, or leave them offscreen altogether.

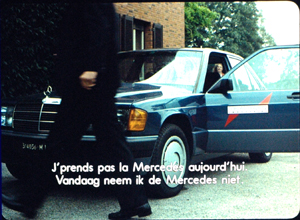

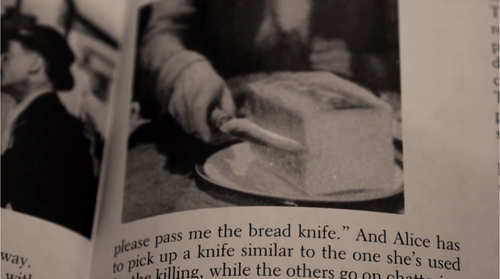

I’ve touched on these matters earlier (here and here), but just as a quick example, consider this shot from the opening of Nouvelle Vague. It has to be one of the most oblique introductions to a protagonist we can find in cinema.

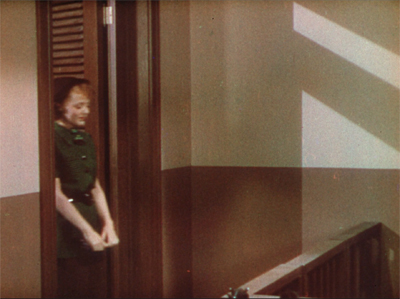

Corporate owner Elena Torlato Favrini strides out of her mansion past her chauffeur while taking a transatlantic call. Any other director would favor us with a close view of her, perhaps tracking as she cuts a swath through her entourage. Instead we get a shot framing her chauffeur climbing out of their Mercedes.

As he crosses in front of the car, we hear her on her cellphone. She can be glimpsed fleetingly in the background, through the car window.

She approaches us, becoming briefly visible as she passes the car, but when she stops, she’s decapitated. We don’t get anything like a good look at her, and the locked-down camera refuses to reframe her. Instead, the framing emphasizes her slipping on her gloves.

The gesture ties into other imagery in the film. A little before this shot, there’s an isolated shot that establishes hands as a major motif in the film. But we should also notice that this fairly abstract shot also presents the gesture of Elena slipping on a glove. Or rather, it almost presents it, as the shot is abruptly chopped off just as the gesture begins.

So slipping on the glove, started in an earlier shot, is finished at the Mercedes. But just as important, the visual idea of a hand gesture broken by a cut resurfaces at the climax. When Richard Lennox helps Elena out of the water, the action is also incomplete. Only five frames show him grabbing her arm before a cut interrupts the action.

Another filmmaker would have held the image on that triumphant grip, but Godard denies us this little burst of satisfaction. Of the five frames in this bit of the shot, there is just one frame showing Richard’s hand seizing her. Godard again spoils a solid narrative effect. But he does narrative in his own way, with the broken-off gestures counterpointed by the hands that do meet at other points in the film.

Every scene in Nouvelle Vague, and most scenes in Late JLG, seem to me to be built on one or more fine-grained pictorial and auditory ideas like these. Those ideas can seem perverse, as in the chauffeur scene: why let us see his face but play down Elena’s? He’s not a major character; we don’t even learn his name until the film’s final moments. Unhappily, this peculiar instant of comparison is lessened in the 1.66 version of the film available on DVD. That image suppresses the driver’s face no less than Elena’s, losing Godard’s peculiar version of “gradation of emphasis.”

All the more reason to try to see these films in their full-frame glory, as I’ve argued before.

BL (Beautiful Loser)/AB/TP

Criss Cross (1949).

With big tousled hair, unadulterated sinew, and teeth gleaming like a Pontiac grille, Burt Lancaster came to fame in the late 1940s. He belonged to a new cohort of actors quite different from the 1930s Debonairs (William Powell, Melvyn Douglas, Cary Grant) and the Bashful Boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart). Yet the new lads were also at variance with the rugged Ordinary Joes (Cagney, Bogart, Tracy, Gable).

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

Of the group, Burt had probably the strongest A-list career overall. He fostered a great variety of projects. Who else of his generation appeared in films by Visconti and Malle? What other unflinching liberal was prepared to play a US general bent on a coup (Seven Days in May) or a conspirator behind the Kennedy assassination (Executive Action) or an obstinate officer fighting in Vietnam (Go Tell the Spartans)? He portrayed a renegade officer demanding the revelation of the brutal policy behind the Vietnam War (Twilight’s Last Gleaming). His closest rival and frequent costar Kirk Douglas didn’t enjoy such a vigorous and prestigious twilight. Only Brando kept beating him to the prize: Burt wanted to play the lead in Streetcar Named Desire and The Godfather. Unpredictably, he wanted as well to play the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman.

I had had only slight interest in Burt as a star before this edition of the Summer School. But listening to the talks, seeing the films, and preparing my contribution made me realize how extraordinary an actor he was, and how important in Hollywood postwar history. Burt was well-served by the fine lectures offered by Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers.

Anke provided an in-depth survey of how Burt and the Brawny Gang brought to a new level the culture of male athleticism—on display in Fairbanks and Valentino, developed further in the body-building craze of the 1930s, and culminating in what one 1954 magazine article called Hollywood’s “Age of the Chest.” She brought in forgotten pin-up boys like Guy Madison and pointed out how Burt and his peers paved the way for Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis. Anke went on to specify Burt’s beefcake persona, established in The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and locked into place in The Crimson Pirate (1952), which we saw. In her followup talk next day, she surveyed Burt’s place in the industry. He was one of the few stars to supervise a successful independent production company, Hecht Hill Lancaster (earlier, Norma Productions and Hecht Lancaster).

Tom moved on to consider Burt’s star charisma. He traced how Burt adjusted his authoritative image to different roles—the con man, the confident leader, the embittered idealist. Tom was especially good at analyzing Burt’s acting technique, tying it to particular trends in theatre and film of the time and pointing up the physicality of his performance of specific, precise tasks. Given the standard situation of rigging a bomb, he contrasted Burt’s meticulous finger work in The Train (1964) with that of Kirk going through the motions in The Heroes of Telemark. Tom even spared some time for Burt’s diction—a quality that really popped out when we watched Elmer Gantry (1960).

In a later lecture, Tom surveyed “Late Burt,” and his relation to political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He followed that with a revealing account of Burt’s relation to the trend of “Mexican Westerns” launched in the 1950s. Another arc in Burt’s career: from Vera Cruz (1954) to Ulzana’s Raid (1972), with The Professionals (1966) in between. That we saw in another gorgeous print.

I could go on a lot more about Tom and Anke’s lectures, but I don’t want to give away too much. The talks contained so much original research and discerning analysis of both the films and trends within film history that I’m hoping Tom and Anke will lay these ideas out at book length. Part “star study,” part film criticism, part industry history, their lectures were exhilarating.

My own contribution was minimal, a talk on First-Phase Burt. The Brawny guys were well-suited to the trend toward hard-boiled movies, those crime pictures we later decided to call “noirs.” Those weren’t usually suitable for older players (though there were some makeovers, such as Dick Powell and Fred MacMurray). To fill these roles came Alan Ladd, Glenn Ford, Dana Andrews, and Richard Widmark, along with the beefcakes. At the same time, “independent” producers within the studios began contracting their own new talent and loaning it out. Burt was signed by Hal Wallis at Paramount, who also had Kirk Douglas, Wendell Corey, and Lizabeth Scott in his stable. Films like Desert Fury (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) were Wallis package projects.

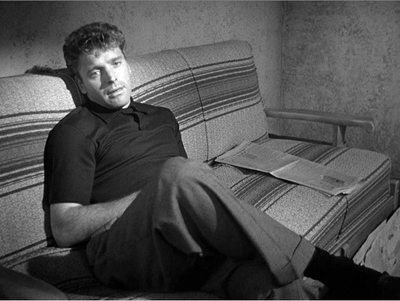

Hired straight from the stage with no film experience, Burt debuted as the Swede in The Killers (1946), on loanout to Mark Hellinger at Universal International. Burt benefited from a galvanizing entrance. Lying on a bed in the dark, refusing to flee the hitmen on his trail, Burt is a shadowed, curiously languid torso in a tight undershirt.

Only after a beat do we see something else: massive hands rubbing a weary head. Soon that head is revealed.

As the killers burst in, the whole image comes together.

Has a Hollywood beginner ever been given such a gift as this opening?

With this onscreen wattage, it’s all the more striking that this young discovery is curiously absent from his early films. He’s onscreen for only a third of The Killers’ running time, and not even half of Brute Force (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number. The film Wallis wanted to be his debut, Desert Fury (1947), gives him only twenty-three minutes out of ninety, and in the second male lead at that. All My Sons (1948) puts him in an ensemble drama. I Walk Alone (1948), the Norma production Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), and another Universal project, Criss Cross (1949) start to make him a proper, central protagonist. By then, he is ready to become the star attraction of the swashbuckling films.

Moreover, in his early phase, he mostly plays losers. Not the brightest guy in the room, he’s easily suckered by a femme fatale in The Killers and Criss Cross. He makes amateurish mistakes at crime (Sorry, Wrong Number) and, coming out of prison, he is the last to realize the rackets have gone corporate (I Walk Alone). At the start of Kiss the Blood he punches a man too hard and kills him. He’s caught and whipped and imprisoned, and when he comes out he stumbles back into crime again. He’s shrewd enough to set up a prison break in Brute Force, but so doggedly determined is he to reunite with his girl on the outside that he launches a suicidal bloodbath.

When he finally catches on to his fate, we get expressions ranging from stupefaction to anguish (The Killers, Criss Cross).

He even cries (All My Sons, Kiss the Blood).

Loser or winner, when he is onscreen, he has the outlandish physical presence of the born star. Most obvious is a physique (Kiss the Blood, Brute Force).

Even his back, featured with a prominence we get with few other actors, is straining against a drenched prison uniform (Brute Force) or a tailored suit (Criss Cross).

The face was a cameraman’s dream; it could be craggy or somber, thoughtful or tormented (The Killers, Brute Force x2, Criss Cross).

He can be stiff-armed and zombielike coming out of prison in Kiss the Blood, but he can also gamely cock his elbows, ready to spring, like Cagney and Cary Grant (I Walk Alone).

The enormous hands, which look likely to crush a skull (Criss Cross) or rip apart a phone cord (Sorry, Wrong Number), could be surprisingly delicate, tentatively touching his girlfriend’s wheelchair or laying down plans like playing cards (Brute Force).

In The Killers he makes skillful use of those hands, pocketing his busted one or spreading out the scarf given him by the treacherous Kitty.

Easily taken in by Kitty’s plan, he seems to have a qualm when his gripping embrace relaxes and the fingers splay in hesitation.

This sort of handwork would become crucial, as Tom pointed out, to Burt’s performance style, particularly in The Birdman of Alcatraz.

“I’d never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s,” Norman Mailer once said. You can see what he meant.

Again, though, the actor is in control. Some years back I wrote that eyes by themselves aren’t very expressive: the eyelids, eyebrows, and mouth tell us more. I still think that’s right, but Burt manages to convey the sense of the beast at bay with remarkable control of just the eyeballs. He seems to be looking for an escape hatch without moving his head an inch.

While Burt was playing losers, his counterpart Kirk Douglas was often playing heels—cynical manipulators who stomp on everybody else, as in I Walk Alone. Sometimes Kirk learns his errors (Young Man with a Horn, 1950) but several roles of the period, in Out of the Past, Champion, and Ace in the Hole, make him a glib villain or tawdry antihero. Somewhat later Burt explored this characterization too, notably in Vera Cruz, Elmer Gantry, and The Rainmaker (1956). How did he shift from the beautiful loser to the fast-talking con artist?

I think there are hints from the start. In The Killers, after he’s washed up as a fighter, the Swede goes in for street crime. When he confronts his old friend the cop, Lancaster brings those arms and hands into play. In his enormous unstructured topcoat, he lifts his fists up to his waist. It’s both the businessman’s getting-down-to-brass-tacks sweep, but also a kind of puffing up, exposing that massive frontal expanse. Little Sam Levene can grasp his lapels, but he doesn’t stand a chance against this.

Burt uses the same imperious gesture when, in Sorry, Wrong Number, he’s trying to bully a company employee into joining a crooked deal.

In these noir movies, his intimidation of others won’t put him ahead of the game. But perhaps these arm movements begin to sketch a more flamboyant loser like Gantry. By striking what actors used to call an “attitude,” Burt could start to build an entire character: a hell-for-leather charlatan.

Seeing the films, listening to Tom and Anke, and studying Lancaster’s work on my own brought home to me again the importance of the details of performance and the presence of a star. These movies would be utterly different if Mitchum or William Holden played the Burt parts. Our actors don’t wear masks or Hazmat suits. We’re powerfully affected by what they bring to the character in voice, body, face, and gesture—the expressive dimensions of cinematic presence.

BL/JLG/BF

College coordinators Lisa Colpaert and Bart Versteirt, flanking Bill Forsyth.

What do Burt and JLG have in common? For one thing, some images from Criss Cross in Histoire(s) du cinema 1a (see above). For another, Bill Forsyth.

With the success of Gregory’s Girl (1981), Bill was invited by David Puttnam, then at Columbia, to make a Scottish movie with a couple of American actors. The result, Bill says, now looks to be a “soft-core environmental movie.” Local Hero (1983) remains much loved, and for good reason. It makes nearly all of today’s multiplex raunch look adolescent. It has a tone of civility, an embrace of eccentricity, and a genuine interest in people reminiscent of Ealing comedies. For me it’s a masterpiece of sweet, light-hearted art.

Local Hero feels loose and leisurely, but it’s actually a very economical movie. The first few minutes should be studied by screenwriters interested in tight exposition and fast attachment to a protagonist. It’s peppered with sidelights on its central drama, such as the Russian’s song about how “even the Lone Star State gets lonesome.” That neatly sums up the situation of the yuppie sad sack MacIntyre (“I’m more of a Telex man”) learning about village life. As usual, I was moved by Mark Knopfler’s plangent score, the electronic overtones meshing with the pulsations of the Northern Lights.

Burt’s role is that of CEO deus ex machina. Having assigned Mac to buy a Scottish seacoast town for an oil refinery, Mr. Happer eventually descends in his chopper and decides to establish a laboratory there instead. Burt’s crisp delivery and tight fingerwork are still on display at age seventy. The other actors don’t use their hands as much as he does–partly so they’re not distracting us from him, I suspect, but also because newer-style Hollywood acting doesn’t encourage it. In any case, as usual Burt uses his acrobat’s sense of physicality to intensify his performance. Even clasping his hands behind his back tells about the character’s authoritative dignity.

Bill learned that Burt regretted not doing more comedy, so he wrote the mogul’s part with him in mind. Burt signed on eagerly. He showed up on the set with a full beard, hoping Bill would let him keep it; they compromised on a mustache.

Bill had worked mainly with teenage actors on That Sinking Feeling (1979) and Gregory’s Girl, so Burt was really the first adult performer he ever directed. Across their three weeks together, Burt demanded nothing, except that he wanted to loop his dialogue. Bill preferred not to loop, and as it turned out only one scene needed to be rerecorded.

Burt and Bill skipped lunch in order to prepare the next scene, becoming “lunch bums.” Bill remembers Burt hanging out with the other actors and chatting with extras. He freely made fun of Bill’s accent: “”He speaks no known language.” He told Bill: “I don’t know what you’re saying, but I know what you mean.”

Bill talked as well about his own career. Starting out in the days before home video, he learned dialogue and pacing by audio taping classic films. (Sounds like a good idea to me.) He became a performer’s director. “The only thing I’ve ever said to a cameraman is: ‘Accommodate the actors.” He quoted Burt approvingly: “The space in front of the camera is the actor’s space.”

What’s the connection to JLG? It turns out that Godard was the director Bill most admired in his salad days. During the 60s he sated himself on art cinema, especially New Wave imports. When he saw Pierrot le fou, he left the theatre stunned. Godard became “the master. He still is, for me.”

Accordingly, Bill’s earliest cinema efforts were in an avant-garde vein. One piece, puckishly called Film Language, started with ten minutes of black leader while a text by Beckett was read out. Another, Waterloo, included a vast ten-minute shot in which the camera left one household, climbed into a car, rode a great distance, and ended up in another home. The film played at the Edinburgh film festival to an audience of 200. By the end three viewers were left. “I’d moved my first audience.”

Bill remarked that he sometimes regrets not sticking with experimental media. Today, he says, he might be a video-installation artist. A teasing idea. But we should be grateful that we got his features. I don’t know if Jean-Luc would agree, but I bet Burt would.

Thanks to Bart Versteirt, Lisa Colpaert, and their colleagues for a great week. Thanks as well to the participants, whose willingness to take on anything we threw at them was very encouraging. And a farewell to two friends who have projected films at every Summer Film College I’ve attended over the last sixteen years: Esther Dijkstra and Joost De Keijser. They have helped make the event the splendid enterprise it is.

Peter Bosma’s informative book Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives is available here.

A detailed “index of references” for Histoire(s) du cinema is provided by Céline Scemama.

Our first encounter with Bill Forsyth was at Ebertfest. For more on actors’ handiwork, try this entry.

An eager crowd of campers awaits Adieu au langage.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Back to the future (of movies)

DB here:

The Teatro Comunale of Bologna is an eighteenth-century opera house that was launched by a premier of a work by Glück. It has hosted massive productions of Wagner, Rossini, and Verdi, and was a favorite venue of Toscanini’s. Elegant and imposing, with box seats and an orchestra pit, it makes you feel like you’re in Senso or Liebelei.

In some years Cinema Ritrovato has secured the Teatro for gala screenings of silent films, complete with orchestral accompaniment. One show of Lady Windermere’s Fan was a delight. In another year, the hammering Meisel score for The Battleship Potemkin nearly blasted me out of my seat. I was sitting up front.

This year it was Rapsodia Satanica (1917) that got the Comunale treatment. This apparition has lost none of its exuberant morbidity, and we got to watch it with the original Pietro Mascagni score. Timothy Brock found that the original orchestra parts were lacking hundreds of tempo changes, because Mascagni himself conducted during screenings and never inserted them. Through careful testing against the film, Brock managed to create a score that brought a packed Communale audience to its feet cheering. One more testament to the power of 1910s cinema.

1915 and all that

Assunta Spina (1915).

I tried, really tried, to see other wonders from all the places and periods on display at this year’s overstuffed Ritrovato. But because of my love of ‘teens films, both American and not, I kept coming back to as many items from that era as I could squeeze in.

There was, centrally, the series Cento Anni Fa (A Hundred Years Ago), curated by Marianne Lewinsky and Giovanni Lasi. 1915 was, of course, a decisive year in American cinema, to be forever identified with Griffith’s monumental The Birth of a Nation. Standard histories would have it that this was the stroke that revealed the artistic power of cinematic storytelling. Griffith’s colossus was naturally very influential, but it wasn’t an isolated accomplishment. Earlier films, such as Weber/Smalley’s Suspense (1913), and other 1915 films–De Mille’s The Cheat and Walsh’s Regeneration in particular–are more typical stylistically of what Hollywood silent cinema would turn out to be.

Add to this list another 1915 item. If film history were an exercise in fairness, Reginald Barker would be recognized as one of the directors who set American filmmaking on its “classical” road. Working under Thomas Ince’s supervision, Barker showed a flair for economical framing, frequent changes of setup, and bold cutting within scenes. His Typhoon (1914) is at many moments more nuanced in its analytical editing than Birth.

1915 was a fine year for Barker. He turned out the long-praised The Italian (shown in the series), as well as the dynamic Civil War drama The Coward, along with superb William S. Hart westerns like On the Night Stage.

So The Despoiler, another Barker from 1915, did not disappoint. It survives only in a cut-down French print, but it still packs a sensational punch.

The original, according to a contemporary review, involves a border war in which troops invade a small town. The leader of the dark-skinned horde fastens on one beautiful woman, who has taken refuge in a nunnery. She is about to sacrifice herself to save the others, when the colonel learns that she is his own daughter. She is saved, and at the very end the whole thing is shown to have been a dream. The French version Châtiment (“Punishment”), painstakingly restored by the Cinémathèque Française in 2010, was modified to fit propaganda demands of the war period. Here the daughter really gets raped, and she shoots her attacker. The colonel turns his troops loose on the nunnery, but halts them in time when he realizes who the victim is. No dream stuff here.

Barker’s style is fluid, and he builds great suspense when the daughter, barely recovered, prepares to shoot her ravisher with his own pistol. The scene has judicious depth staging, as when the soldier lies drunkenly on the cot but he’s blocked by the woman’s gradual decision to use the weapon. At the proper moment she swivels aside to reveal his head lolling in the background.

The match-on-action when the woman turns and pulls up her sleeve is more perfect than many such cuts in Griffith’s films. She then strides to the background to give us a full view of her target.

A brief shot of the daughter’s attacker is replaced by a 3/4 view of her drawing a bead on him, with Jesus taking her side.

Other countries’ 1915 output wasn’t ignored. We got Denmark’s Revolutionary Wedding, proof that August Blom had not given up the somewhat rigid version of the tableau style he had used in Atlantis (1913). More florid were the Italian offerings. Assunta Spina (lovingly restored by Bologna’s own Cineteca and now available in a DVD), is a classic of the nation’s silent cinema. It was treated to a carbon-arc projection one evening in the courtyard. The less-known but no less flamboyant Il Fuoco (“The Fire”) is a melodrama about a rich woman who destroys a naive, passionate painter.

The two films are famous for showcasing the divas Francesa Bertini and Pina Menicelli respectively. But they’re just as important as powerful illustrations of the variety of 1915 pictorial styles. Assunta Spina is a triumph of tableau staging. By contrast, the opening of Il Fuoco, detailing the first encounter of the owl-woman and the burly artist, is as rigorous a piece of editing that I’ve seen anywhere at the period. Assunta Spina fills the frame with layers of depth (above and first still below). Il Fuoco makes play with bold optical POV, especially when the painter is transfixed by his languid model.

To which one can only say: Zowie.

Bluebirds of happiness

Back in the 1980s I wanted to see some films from Universal’s Bluebird Photoplay series. It had been accepted wisdom that the Bluebirds were among the first American films seen in Japan, and accordingly they had influenced Japanese filmmakers. My searchings led me merely to fragments at the Library of Congress. But today, according the Ritrovato’s indispensable catalog, about thirty complete titles have been found in archives. The most famous, Lois Weber’s Shoes (1916), screened at Bologna in 2011.

The Bluebird franchise was identified with feel-good stories, often rom-coms centered on women and derived from fiction by women. Mariann Lewinsky points out that the unit was a training ground for Rudolph Valentino, Mae Murray, Tod Browning, Rex Ingram, and several other notables. A striking number of Bluebirds were directed by women, in particular Elsie Jane Wilson. About 170 films were produced under the logo, and Hiroshi Komatsu’s catalogue entries confirm that they had a powerful impact on Japanese fans and filmmakers.

Four Bluebird titles, all discovered at the French CNC archive, confirmed the ingratiating charm attributed to the brand. Little Eve Edgarton (1916) centers on a botanist daughter who’s whip-smart in science. Her father tries to marry her off to an older colleague, but she resists. The Love Swindle (1918) is more elaborately plotted. The main couple meet cute during a comic home invasion, in which Diana Rosson proves better at defeating hungry tramps than Dick Webster, who gets conked out trying to protect her. After a date, Dick decides Diana’s too modern and highbrow for him. Diana, undaunted, takes a room in a pension and masquerades as her own impoverished sister, Miranda. Dick naturally falls for Miranda.

Here again, the polish and inventiveness of ‘teens Hollywood comes through. Stylistically, we find nearly everything characteristic of classical presentation: scene analysis, angled shot/reverse shot (though no over-the-shoulders), surprising camera movements, expressive low and high framings. In narrative terms, our heroines conceive goals and pursue them tenaciously. Rosamond in The Dream Lady (1918) even makes a list of her four aims in life. Getting a house is surprisingly easy; marrying a real gentleman takes a little longer.

There are as well ambitious storytelling gambits. At one point in The Dream Lady, an orphan girl imagines that she has a mother and lives in nice surroundings. Director Elsie Jane Wilson cuts freely between the girl’s fantasy and Rosamond looking in on her. One startling cut matches on the girl’s gesture of flouncing her ribbon, taking us between dream and reality. (It’s actually a cheat–wrong arm–but perhaps the change of angle covers the disparity. Sort of like here.)

Then there’s the plot of The Little White Savage (1919). It starts with a circus boss and his sidekick telling customers how they acquired a star attraction, a wild girl purportedly from an island on no maps. The flashback yarn is absurd from the get-go, and it gets wilder as it proceeds, as the heroic sidekick somehow goes from he-man adventurer to pious parson. In a surprisingly salacious passage, Minnie, escaped from the sideshow, hops into the clergyman’s bed. They squeeze and nuzzle unashamedly as nosy townsfolks watch in horror.

It’s all a tall tale, of course, confirmed when the frame story reveals Minnie as simply a cute modern girl. The Confession (Fox, 1918), hinged on a more serious lying flashback and may have supplied the premise for The Little White Savage. Again we find the 1910s as an era of fertile innovation. “Its breezy bold difference makes it worthwhile,” wrote a critic of this Bluebird release. “What Paul Powell and scenarist Waldemar Young have done here is the sort of adventure that makes screen progress.”

A bigger-budget Universal release served as pendant to the Bluebirds. Lois Weber’s Dumb Girl of Portici (1916) was a collaboration with dancer Anna Pavlova. A truncated version had long lain at the British Film Institute, but Geo Willeman and Valerie Cervantes found a 16mm print at the New York Public Library. That enabled them to create a very pretty, nearly-complete version, which now concludes with a lengthy Pavlova dance. The super-production, now running nearly two hours, was based on Daniel Aubert’s 1828 opera and offers some ambitious spectacle.

As a prestige entry with crowd scenes, lavish sets, and one of the stage’s top stars, it’s about as far from the humble Bluebirds as you can get. It’s notably stiffer and less dynamic too; what is it about costume pictures that makes for an academic approach? Still, The Dumb Girl of Portici and the Bluebirds exemplify the ways in which filmmakers of the period laid down many paths of exploration for the future.

The devil you know

I first saw Rapsodia Satanica some years back during a Brussels visit. I liked it fine, but seeing it with tinting and hand-coloring, on the big Comunale screen, with a live orchestra convinced me that it really needs its score. The plot is thin, but with the music throbbing along with its heroine’s seductive pirouettes and mournful drifting, the whole thing makes powerful cinema. It was in fact billed as a “Cinematic-Musical Poem,” suggesting that here lyricism will dominate.

With the score tightly matching fluent acting, I’m reminded of a point Kristin made some years ago. She wrote about the ‘teens as an era in which many directors opened up new domains of cinematic expressivity. Having developed effective methods of storytelling, they began looking for techniques that would deepen the emotional impact of the action. Rapsodia satanica is practically a case study for this tendency.

Countess Alba sells her soul to regain youth. One of her suitors kills himself, the other flees. She winds up alone on her estate. This simple story is elaborated through many techniques of mise-en-scène. There are the dancelike performances; Satan practically coils himself around his victim’s calf. There are the costume changes, as Alba moves from her heavy dowager dress to diaphanous veils in her voluptuous phase, and then, in her solitude, a simple shift. When she thinks the surviving lover is about to return, she wraps herself in the veils she wore before. Even the hand-coloring adds impact; as in the pair of stills below, often Alba’s dress is the only colored mass in the shot.

The hallucinatory images gain both precision and passion from the soaring score. Our heroine sells her soul to Satan in exchange for a return to youth. The moment when she sheds her elderly skin and emerges, like the butterfly we’ll see later, as a ravishing beauty is accompanied by a motif that exfoliates just as lushly. An offscreen pistol shot is prepared by a driving crescendo, but the orchestral outburst is still startling. The countess registers the realization that one lover has killed himself, and diva Lyda Borelli synchronizes her attitudes with that climax: body clenched at first, then sliding toward a more doleful pose.

At forty-two minutes, Rapsodia Satanica is practically, as Gian Luca Farinelli remarked in his introduction, an experimental film. Its unsettling use of multiple mirrors, trapping the heroine in fractured reflections, sets up Charles Foster Kane’s zombie-like passage through his palace. The film’s second part, in which the heroine drifts through landscapes and enormous rooms, looks forward to the American “trance films” of the 1940s and the Cinema of Walkies, from Neorealism and Antonioni to Tarkovsky. In all, the film lets us recognize the persistence of some trends across film history, and appreciate that the 1910s are not as far away as they might seem.

Thanks to Guy Borlée and Cecilia Cenciarelli for help with this entry.

The immense catalogue of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, essential for background to the screenings, can be purchased here. There’s a pdf for reading or downloading here. These folks think of everything.

For contemporary accounts of The Despoiler, see the Lantern pages here and here. The Cinémathèque Française webpage provides a detailed explanation of the restoration. The Photoplay review of The Little White Savage is here.

You can read more about Bluebirds at Adrian Curry’s “Poster of the Week” site on mubi, from which I took the Bluebird logo above. Be sure to scroll down to enjoy the gorgeous designs on display.

For more on why the ‘teens are crucial, see the Vimeo talk, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” On continuity editing, you might start here; on tableau staging, here. Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds., Film and the First World War (1995).

Rapsodia Satanica.

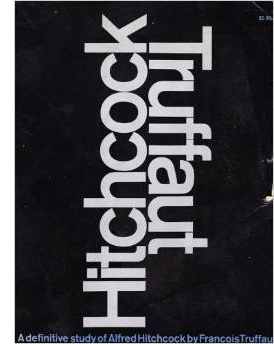

TRUFFAUT/HITCHCOCK, HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT, and the Big Reveal

Photo by Philippe Halsman.

I’m going through a Hitchcockian period; every week I go and see again two or three of those films of his that have been reissued; there’s no doubt at all, he’s the greatest, the most complete, the most illuminating, the most beautiful, the most powerful, the most experimental and the luckiest; he’s been touched by a kind of grace.

François Truffaut, letter, 1961

DB here:

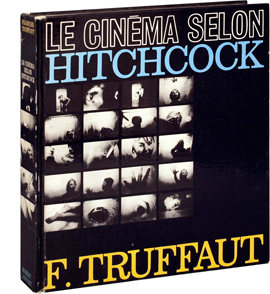

In June of 1962, François Truffaut wrote to Alfred Hitchcock proposing a lengthy interview. Hitchcock agreed, and Truffaut materialized in Los Angeles in August, with his translator and collaborator Helen Scott. After six days of discussion, Truffaut had accumulated, he claimed, fifty hours of tape. Over the next four years the tapes were transcribed, the book was edited, and extra sessions were recorded to cover the films Hitchcock made in the meantime. The result was published in France in late 1966 and a year later in an English translation.

Energetic scholars have recently discovered that the finished book bears signs of massive cutting, compression, and recasting of the conversation. It seems that Hitchcock approved something like the final version, but on this director we want everything. Eventually we will want a complete transcription, but with some tapes still missing, that isn’t possible for now. But we do have some tapes, and just as important, we have the book known in English as Truffaut/Hitchcock.

What Truffaut called his “Hitchbook” is now the subject of fascinating documentary by Kent Jones. Premiered at Cannes, Hitchcock/Truffaut was so successful that an extra screening was scheduled to meet the demand. Why so much interest? Of course, Hitchcock remains a filmmaker known to everyone. But we should also recognize that the Hitchbook was one of the most important books on film ever published.

Popular material treated with intelligence

Alfred Hitchcock, who is a remarkably intelligent man, formed the habit early—right from the start of his career in England—of predicting each aspect of his films. All his life he has worked to make his own tastes coincide with the public’s, emphasizing humor in his English period and suspense in his American period. This dosage of humor and suspense has made Hitchcock one of the most commercial directors in the world. . . . It is the strict demands he makes on himself and on his art that have made him a great director.

François Truffaut, review of Rear Window, 1954

The film’ s title is an impudent reversal: “Hitchcock/Truffaut” puts first things first, a dialogue between a master and his adoring admirer.

At first glance, this is a clips-plus-talking-heads doc. But that impression doesn’t do it justice. For one thing, many of the clips are fresh ones, drawn from rarely shown Hitchcock films. These tease us with their unfamiliarity, like a gallery of less-known pictures flanking a hall of masterpieces.

Moreover, the film’s perspective is far more sophisticated than what we usually find in the genre. Hitchcock/Truffaut respects its viewers enough to summon up suggestive and subtle links between sequences, between image and commentary. Often there’s no title marring the images, so they stand out with a hallucinatory purity. Often a clip starts to play before the commentary kicks in, all the better to let the imagery strike us in its integrity; only then do we get the connection to what came before. The extracts are the prime movers, with the text snapping into place to catch up.

The speed and precision of Hitchcock’s movies are paralleled by the swift opening of Jones’s film, which introduces the main themes. As shots from Sabotage are intercut with the book’s flipping pages, we hear a chorus of voices. These belong to our talking heads, and the heads are full of ideas. Remarkably, all the commenters are film directors. It’s a top-tier lineup, of Movie Brats (Scorsese, Schrader, Bogdanovich) and younger talents David Fincher, James Gray, Wes Anderson, and Richard Linklater. From overseas come Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Olivier Assayas, and Arnaud Desplechin. There are no academic experts, no journalists or friends or family. Everything, we quickly learn, is going to be about cinema as art, craft, and vocation.

Immediately, as if reenacting Family Plot, the film shows how two paths crossed. A quick summary of each man’s career leads to that six-day week in 1962, overseen by the beaming Helen Scott, and our film launches itself into the depths.

We learn of Hitchcock’s urge to outwit the audience, and his thoughts on plausibility. He reviews matters of technique, from image size to the expansion of time. How do you handle actors? How do you give your film a shape? About halfway through, the questions go bigger, and the Cahiers concerns preside. Is M. Hitchcock a Catholic artist? (He gives his answer off-mike.) Is his work haunted by guilt, even Original Sin? (“Yes,” he murmurs.) Don’t the plots enact a transfer of guilt? Don’t they exhibit the logic of dreams?

At one level, Hitchcock/Truffaut is a fine introduction to the issues in French film writing about the Master, articulated most fully by Desplechin. But the Americans bring in plenty of insights as well. Fincher and Scorsese track changing acting styles of the 1940s and hint at the problems those caused for Hitchcock. Schrader notes the recurring fetish-objects (keys, handcuffs) and points out that Vera Miles (Hitchcock’s choice for Vertigo) could never have carried off Kim Novak’s painfully sluttish turn.

Two extended sequences are devoted to Vertigo and Psycho. These allow Jones and his co-screenwriter Serge Toubiana to knot together all the major themes. Vertigo encapsulates the dream elements, and through careful editing Hitchcock/Truffaut turns Hitchcock’s interview remarks into a commentary track under key sequences. Meanwhile, the filmmakers riff freely on what we see. What about Judy’s story? asks Fincher. Scorsese finds “a sense of loss and melancholy.” Judy’s stepping out of the bathroom yields what Gray calls “the single greatest moment in the history of movies.”

But Vertigo wasn’t a huge success, especially for a filmmaker who aimed at arousing the mass audience. The movie that exemplified “pure film,” Hitchcock says, was Psycho. Again our filmmakers are powerfully eloquent about its creative choices (pacing, framing, point-of-view) and, above all, its devastating shocks. It was, says Bogdanovich, “the first time that going to the movies was dangerous.” Psycho’s stupendous popularity, Truffaut remarks in the last edition of the book, made it the capstone of the Master’s career. “I am convinced that Hitchcock was not satisfied with any of the films he made after Psycho.”

Many reviewers of Hitchcock/Truffaut have fastened on moments in the interviews when Hitchcock expressed doubt. Should he have veered off from controlling the “rising shape” of every story? Should he have been “more experimental”? Should he have paid more attention to character rather than situation?

Such questions were raised in Truffaut’s 1983 addendum, but I’m not convinced they’re valid. They presume that plot is less valuable than character, and that thriller plots are somehow intrinsically thinner than other kinds. Truffaut offered the best defense of the power of a gripping intrigue when he suggested that a disciplined format didn’t make things shallow. He suggested that following Hitchcock’s example could be fruitful.

Don’t tell me that it would be inferior or vulgar. Just think of Shadow of a Doubt and Uncle Charlie’s thoughts: the world is a pigsty, and honest people like bankers and widows detest the purity of virgins. It’s all there, but inserted into a framework that keeps you on the edge of your seat.

Hitchcock put it another way: A good film, he remarked, consists of “popular material treated with intelligence.” And that intelligence can take chances. Shadow of a Doubt, Lifeboat, Rope, Rear Window, Psycho, and Family Plot are among Hollywood’s great experiments.

The Figure in the carpet

Storyboard image for Psycho.

My initial aim in undertaking [Truffaut/Hitchcock] was not to make the best-seller list, but to influence and shake up the smug attitudes of the New York critics.

François Truffaut, letter, 1967

Truffaut/Hitchcock had been out for a year when I got my copy in December 1968. Why did I wait? No paperback edition, and the hardback cost a princely $10. That’s about $70 in today’s currency.

That sturdy copy has followed me around ever since, and now, nearly fifty years later, I still find it stimulating. I can’t think of another book on the cinema that has had its influence. Let me count some ways.

It changed tastes. Truffaut tells us that he decided to do the book when he learned that American critics considered Hitchcock as merely a popular entertainer. Not all reviewers needed convincing, though. Robert Sklar found it “likely to become a classic book on the art of the film. . . . No book before this one has made a better case for Hitchcock’s genius or for the French ‘author’ theory of film directorship.”

In the pages of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther had long treated Hitchcock as a talented purveyor of suspense who sometimes gave good value (Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Vertigo) but who too often favored wildly implausible plots (Strangers on a Train) and “slow buildups to sudden shocks that are old-fashioned melodramatics” (Psycho). Yet the Times granted Truffaut/Hitchcock two admiring reviews. One by Eliot Fremont-Smith declared that Hitchcock had turned out “a surprising number of perfect or nearly perfect movies.” Arthur Knight praised Truffaut’s careful preparation for the encounter and celebrated Hitchcock’s almost unique control over his projects. His films were at once technically adept, emotionally exciting, and bristling with what Truffaut called “moral dilemmas.”

In the pages of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther had long treated Hitchcock as a talented purveyor of suspense who sometimes gave good value (Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Vertigo) but who too often favored wildly implausible plots (Strangers on a Train) and “slow buildups to sudden shocks that are old-fashioned melodramatics” (Psycho). Yet the Times granted Truffaut/Hitchcock two admiring reviews. One by Eliot Fremont-Smith declared that Hitchcock had turned out “a surprising number of perfect or nearly perfect movies.” Arthur Knight praised Truffaut’s careful preparation for the encounter and celebrated Hitchcock’s almost unique control over his projects. His films were at once technically adept, emotionally exciting, and bristling with what Truffaut called “moral dilemmas.”

As Sklar indicates, Truffaut/Hitchcock gave aid and comfort to auteurists. If you wanted to make a case for creative artistry in Hollywood, Hitchcock was the logical point man—a cinematic virtuoso and a director whose films were instantly recognizable. Andrew Sarris’s first Village Voice review set the tone: Psycho indicated that “the French have been right all along.” The English critics of Movie followed with vigorous analytical essays, while Robin Wood’s probing thematic study Hitchcock’s Films (1965) may have helped establish an audience for Truffaut’s book. Truffaut predicted in 1983 that “By the end of the century, there will be as many books written about him as there are now about Marcel Proust.” The prophecy may well have been fulfilled, and in a new century the literature seems to be swelling even faster.

The book affected tastes in another way, I think. It appeared when French filmmaking enjoyed great prominence in America. Unlike what happened in later decades, in the 1960s and early 1970s we could see virtually everything being made by Truffaut, Varda, Chabrol, Demy, Resnais, Bresson, Rohmer, Melville, and other major filmmakers; Godard sometimes gave us three a year. There were middlebrow hits too, like Sundays and Cybèle (1962) and A Man and a Woman (1966). It seems hard to believe now, but in 1966-1967, twelve numbers of Cahiers du cinéma were published in a handsome English-language edition. Just as important, the year 1967 brought America not only Truffaut’s book but Hugh Gray’s translation of Bazin’s What Is Cinema?

For years afterward, France set the tone for both arthouse distribution and serious cinephilia. Importers brought us La Cage aux Folles, Tous les matins du monde, Amélie, Ma vie en rose, and other vessels of Gallic charm and profundity. Journalists and programmers stalked through French festivals searching for the next big auteurs. Later, academics learned about semiology, neo-Marxism, and Lacanian psychoanalysis from their Parisian counterparts. To this day, critics beg their editors to send them to Cannes and academics beg presses to consider another book on Deleuze. The Hitchbook helped establish France as the home of adventurous thinking about cinema.

Master and disciple

I’d like everyone who makes films to be able to learn something from it, and also everyone whose dream it is to become a filmmaker.

François Truffaut, letter, 1962

It influenced filmmakers. Jones’ documentary highlights the Hitchbook’s enduring power for generations of directors. Wes Anderson says that his copy has fallen to tatters; Fincher read his dad’s over and over, marveling at how the layout of images made the editing patterns apparent. For the young Gray it was “a window into the world of cinema.” The book, says Scorsese, gave courage to a generation: “We became radicalized.” It showed that he and his cohort “could go ahead.”

The book’s impact came from its insider aspects. As Schrader points out, we already had many books about the art of cinema, but Hitchcock shared secrets of craft. How did he get particular effects, like Foreign Correspondent’s plane crash, with the ocean bursting straight into the cockpit? Hitchcock had views on what made film art (montage, mostly) but he also knew, as Fincher puts it, what made it fun. The flagrant virtuosity which Hitch’s detractors attacked was a powerful stimulant for 1960s filmmakers. The chef has taken us into the kitchen and revealed his recipes.

Take camera placement. Many of today’s moviemakers and TV directors are fairly indifferent to the niceties of framing. Scorsese crisply shows how important the high angle is in Hitchcock’s work. You can read it thematically (God looking down) but it’s also elegantly functional. In Topaz, Scorsese points out, the camera’s deviation from the straight-on view is unsettling, and it accentuates the defector’s eye movements. An unexpected, queasily close high-angle is practically a Hitchcock signature, as here from The Man Who Knew Too Much and North by Northwest.

Beyond their craft, Hitchcock films yielded a personal vision of the world. That vision wasn’t a matter of messages articulated in clunky dialogue (vide Stanley Kramer). Hitch’s personality soaked into the very textures of his plots, his characterizations, and above all his attitude toward the story and the audience. The Cahiers critics had found individual expression in the Hollywood studio product, and Hitchcock’s world revealed some fairly sordid corners.

He was obsessed with looking, duplicity, doubles, and hidden identities. Some of his characters, such as Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt and John Brandon in Rope, are suave sociopaths. In Notorious, the putative hero is a cynical bully, while the Nazi he’s stalking is a gentle and charming husband. A detective obsessed with a woman manages to kill her twice; a husband who wishes his wife dead gets what he wanted. The plots pass harsh judgment on momentary slips, like looking out your back window, listening politely to a loopy train passenger, or placing imaginary racetrack bets. If Ben Jonson lifted sardonic misanthropy to the level of art, why couldn’t Hitchcock?

It’s as if the Movie Brats and those who followed were scoping out the realities of the business they were entering. I think they took hope from a man who made a great deal of money working with stars, flummoxing producers (Selznick in particular), embracing new technologies (sound, widescreen, even 3D), and managing to put an idiosyncratic spin on forced-march projects. It’s easier to reconcile the one-for-them-and-one-for-me dynamic when you remember what Hitch made of assignments like Rebecca, Dial M for Murder, and (even) Topaz. By letting Hitchcock explain the commercial pressures he faced, and the ways he found to dodge or work within them, Truffaut must have given young filmmakers a conviction that they could do personal work in the industry.

Pictures that work hard

The interest of the book will lie in the fact that it will describe in a very meticulous fashion one of the greatest and most complete careers in the cinema and, at the same time, constitute a very precise study of the intellectual and mental, but also physical and material, “fabrication” of films.

Francois Truffaut, letter, 1962

It influenced film criticism too. For one thing, it confirmed the interview as a legitimate critical tool.

Truffaut didn’t invent the cinephiliac director interview, of course. Cahiers and Movie undertook interrogations of directors; Pauline Kael notably mocked Movie for asking Minnelli about a crane shot. But after the revelations of Truffaut/Hitchcock, people who wanted to put movies down couldn’t automatically assume that directors were inarticulate. Yes, they’d recycle their favorite stories, usually mythical; yes, they knew ways to dodge the hard questions; but get them going on craft and you stood a chance of learning something. The god of cinema dwelled among the details, and Hitchcock spread out details with solemn largesse.

Sarris had displayed some of the possibilities in his Interviews with Film Directors (1967 again!). But that book republished interviews already out there. Truffaut’s through-composed marathon showed the power of the interview format as an analytical probe. Today, nobody would think of writing about a filmmaker without consulting published interviews—or better yet, trying to wangle a fresh one. The book-length interview has become a genre, as in the X-on-X series from Faber and Faber and, more lavishly, Matt Zoller Seitz’s books on Wes Anderson.

Furthermore, despite Truffaut’s insistence on Hitchcock’s commitment to “pure cinema,” the book gave new credence to a quasi-literary approach to film criticism. Truffaut repackaged the Cahiers thematic interpretations of Hitchcock. A film’s true meanings were elusive; they had to be unearthed. Films could now be read. Once we could find Catholic guilt in Strangers on a Train and an omniscient, perhaps bemused deity in a high angle, why not extend the strategy to other filmmakers? It seems to me that Truffaut/Hitchcock was a major step toward our apparently endless efforts to find hidden meanings in popular filmmaking.

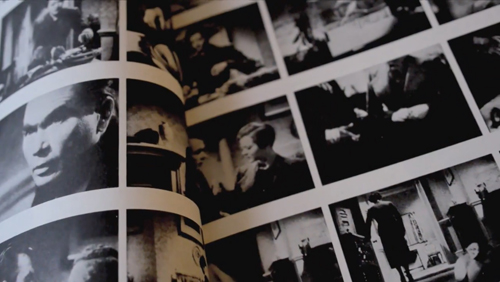

To his credit, Truffaut understood that such reading had to be very close. He needed pictures. His correspondence details his demand that the illustrations “correspond exactly to Hitchcock’s own comments on the film.” Truffaut shrugged off any worries about permissions. Film books of the day, when they included pictures, used production stills—photos taken on the set, which seldom corresponded to what was on the screen. Truffaut used some production stills, but he took pride in packing in genuine frame enlargements, actual images from film prints. I can think of only one earlier author who systematically deployed actual frames to illustrate points of technique: Sergei Eisenstein, in The Film Sense (1943) and Film Form (1949).

To his credit, Truffaut understood that such reading had to be very close. He needed pictures. His correspondence details his demand that the illustrations “correspond exactly to Hitchcock’s own comments on the film.” Truffaut shrugged off any worries about permissions. Film books of the day, when they included pictures, used production stills—photos taken on the set, which seldom corresponded to what was on the screen. Truffaut used some production stills, but he took pride in packing in genuine frame enlargements, actual images from film prints. I can think of only one earlier author who systematically deployed actual frames to illustrate points of technique: Sergei Eisenstein, in The Film Sense (1943) and Film Form (1949).

Today, when hundreds of websites run clips and framegrabs, we need to remember just how bold and tenacious Truffaut was. He borrowed 35mm prints from studio archives and spent three days in London making stills from the British titles not available in France. He could then provide meticulous shot-by-shot presentations of sequences—central to proving the artistry of a man who put editing at the center of film art. The original French edition flaunted its production values, slugging frames from the Psycho shower sequence across front and back cover.

Once Truffaut made such displays thinkable, film criticism could become more analytical. Enterprising writers got hold of prints, projected them incessantly or studied them on editing machines. Most notable was Raymond Bellour, whose 1969 analysis of The Birds (below) pushed analysis to an unprecedented degree of exactitude.

Throughout the 1970s, film critics became more adept at this shot-by-shot study. It was one hallmark of my generation of academic film writers, especially in dissertations. That group included Ted Perry at Iowa (in a dissertation on L’Eclisse, 1968) and NYU scholars Fred Camper, Paul Arthur, and Vlada Petrić. P. Adams Sitney’s trailblazing Visionary Film (1974) brought this sort of scrutiny to the avant-garde tradition. I followed the same line in my 1973 monograph on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and in my 1975 dissertation on 1920s French cinema.

Throughout the 1970s, film critics became more adept at this shot-by-shot study. It was one hallmark of my generation of academic film writers, especially in dissertations. That group included Ted Perry at Iowa (in a dissertation on L’Eclisse, 1968) and NYU scholars Fred Camper, Paul Arthur, and Vlada Petrić. P. Adams Sitney’s trailblazing Visionary Film (1974) brought this sort of scrutiny to the avant-garde tradition. I followed the same line in my 1973 monograph on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and in my 1975 dissertation on 1920s French cinema.

French scholars were following Bellour’s lead, and a significant school of textual analysts emerged. The BFI magazine Screen opened up similar avenues with Stephen Heath’s 1975 analysis of Touch of Evil. A few teachers started to incorporate frame enlargements as slides for lecture courses. Kristin and I did, while inserting frame enlargements into our publications. We may have been the first to publish a film aesthetics textbook, Film Art (1979), relying on actual shots, not production stills.

Studying films shot by shot was difficult, requiring 16mm or 35mm prints and machinery like analysis projectors and flatbed viewers. To document the shots, you had to take frame enlargements with a bellows and a still camera. By the time videotape and laserdiscs came along, intensive study was far easier. Not until we got DVD technology, though, was it simple to make decent frame grabs to illustrate critical pieces.

Now everybody does what Truffaut did. But let’s remember that we analysts, along with nimble video essayists like Seitz, Kevin B. Lee, and Tony Zhou, owe a debt to Truffaut’s obstinate insistence that “quoting” a film, even partially, allows us to understand it more deeply.

Looking in his direction

This book on Hitchcock is merely a pretext for self-instruction.

François Truffaut, letter 1962

Given Truffaut’s deep admiration for the Master of Suspense, we’ve long assumed that he tried to learn from him. Like Hitchcock, he cared very much about evoking a response from his audience, and he sought as well to master the disciplined technique that could create precise effects. As early as The 400 Blows, he had Hitchcock in mind, as he confessed in the interview.

The recent availability of the 1962 tapes enabled Hitchcock scholar Sidney Gottlieb, in an article teasingly titled “Hitchcock on Truffaut,” to explore portions of the conversation in which Hitchcock comments on a key passage in Truffaut’s film. Truffaut tells Hitchcock of the moment when Antoine Doinel and his schoolmate, playing hooky, catch his mother kissing her lover on the street. Antoine rushes off and she guiltily turns away, telling her lover that her son has recognized her. Hitchcock, who apparently hasn’t seen the film, asks about Truffaut’s intention and tries to visualize the scene.

Jones’ film smoothly incorporates the sequence, letting the men’s voice-over discussion provide a gloss. The passage allows us to pinpoint some important aspects of Hitchcock’s discipline.

Truffaut is shooting on location, with a camera that’s often very far from the action. We see the boys walking right to left in an extreme long shot, and then we cut to another extreme long shot, in which Antoine’s mother and the lover are embracing by a Métro entrance. They are centered, but there’s a great deal of city life in this frame as well, so one can easily miss them. Even if we notice the couple, we can’t clearly recognize the woman as the mother.

In order to make clear what’s happening at the Métro entrance, Truffaut gives us two further shots of the couple. The first conveys only the act of kissing; we can’t really identify the characters. The second shot reveals that the woman is Antoine’s mother.

Truffaut indicates to Hitchcock that he was short of footage, but there’s also the problem of shooting on location. Truffaut could have cut directly from the extreme long-shot to reveal the mother (that is, from my second shot to my fourth). But that would have been rather disjunctive, and without the railing in the third shot we wouldn’t know the characters’ orientation very clearly. The shot of the railing indicates that we’re roughly opposite to the angle taken in the extreme long shot. Still, the whole series—three shots needed to establish that the mother has a lover and is kissing him—is somewhat uneconomical.

Having given us important information about the mother’s affair, Hitchcock might have made us wait longer, raising suspense about whether Antoine would discover the illicit couple. Instead Truffaut cuts immediately to a panning shot of Antoine and his pal passing and looking more or less to the camera. That’s followed by a shot of the mother seeing Antoine and turning abruptly away. The boys also turn away and hurry off.

We’re in the familiar territory of constructive editing and the Kuleshov effect. There’s no establishing shot that includes all the dramatic elements. Similarity of locale, the exchange of glances, continuity of sound effects, and the concept (they see each other) knit the shots together.

Again, though, there’s a certain roughness to the effect. The second shot of the mother looking into the camera seems to be roughly Antoine’s point of view, but that camera setup has already been given us as an “objective” shot of her kissing her partner. Apart from the eyeline, there isn’t any marker of the second one as subjective—such as a sidelong camera movement that might correspond to Antoine’s walking viewpoint. POV shots can be slippery in classical filmmaking, so it’s not exactly an error, but Truffaut gave up the chance for a more nuanced variant.

The couple’s placement remains a little vague in this shot too, again because there’s no railing to orient us. If the mother is more or less blocked by her lover (her back is to the railing), her later glance at Antoine must fall quite far down the sidewalk on her left. But when he passes he’s further up the sidewalk, on her right. Yet he’s supposedly looking more or less directly at her.

Put it another way. In the physical terms given by earlier shots, the lover’s back would hide the mother from Antoine until he was quite far down the sidewalk on her left. He’d have to turn back to see her. Yet the boy seems to be looking at her from a position more or less opposite her, in effect “through” the lover’s back.

Plainly we get the point of the scene. But there’s a certain roughness to the presentation. That may be why Truffaut felt he needed the return to the railing setup to show the mother turning away, followed by an explicit underscoring of what just happened through dialogue.

Hitchcock, a little sadly: “I would’ve hoped that there was nothing spoken.”

Truffaut admitted to Hitchcock that he didn’t have enough footage and was forced to intercut the shots too much. “In the cutting room it was absurd. . . . It was less good than if I’d thought it out beforehand. Then I would have had a variety [of shots].”

In the interview Hitchcock goes on to remake the sequence at one remove. He suggests that we could start with Antoine walking and markedly seeing the mother. Then we see her turn, “looking in his direction.” The boy turns away, then she turns away. Simple and straightforward.

To get a concrete example, consider how Hitch directed a scene of one person catching another by surprise. In Stage Fright, the blackmailing maid Nellie Goode has come to the garden party to squeeze more money from Eve Gill. Hitchcock shows us that Nellie is present and then shows Eve and Ordinary Smith approaching unawares in a distant shot—more or less from Nellie’s optical standpoint.

Thus the shot of the person seen is anchored in relation to the person seeing. After a reverse angle on Nellie, with the long-shot scale more or less matching its mate, we get a shot of Eve noticing Nellie.

We have another piece of constructive editing, but we scarcely notice the absence of a master shot. The geography is crystal clear, not least because of the marked eyeline. And now, as in Truffaut’s scene, an objective framing becomes subjective. We get a parallel series of shots, one setup showing Nellie advancing, the other a tight framing just on Eve, who halts Nellie by signaling with her eyes and mouth. On the couple, the framing has gone from long-shot to two-shot to single.

When Nellie stops, puzzled, Eve launches her plan to send Smith off to her girlfriends. Eve leaves, Smith follows, and we’re back to Nellie watching in annoyance.

Bare-bones though it is, this sequence is more complicated than Truffaut’s, because the third party, Ordinary Smith, mustn’t be allowed to notice Nellie. We take it for granted that the mother’s lover doesn’t recognize Antoine, but Eve must actively distract Smith. Moreover, there is dialogue running throughout this action, as Smith chatters away to charm Eve. So we have the familiar Hitchcock technique of playing banal dialogue in counterpoint to suspenseful imagery.

Everything that happens—Nellie waiting in ambush, the exchange of looks, the fluttering expressions on Eve’s face, the policeman’s obtuseness—is rendered fully. The functional precision of this simple passage shows why Hitchcock liked shooting in the studio. He could control all his angles, eyelines, and shot scales exactly. Truffaut had to make do with what he could grab on a very busy location. Still, as he points out, he compensated somewhat by the very tightly controlled scene later in 400 Blows, when Antoine’s parents come to school. There the closed conditions of the classroom allowed a sharper articulation of glances and camera angles. It’s no set-piece, but it’s a tidier piece of work, somewhat Hitchcockian.

The Truffaut thriller

Mississippi Mermaid (La Sirène du Mississippi).

I have adapted too many novels, especially American novels. Oddly enough, it has become quite clear that (with the exception of Jules et Jim) my intentions have been better understood when I have filmed such original screenplays as Les 400 Coups, Baisers voles, L’Enfant sauvage, and La Nuit américain than when having filmed Irish and Goodis.

François Truffaut, letter, 1974

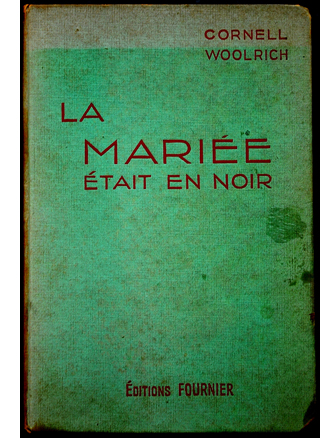

Mystery novels were popular in France well before World War II, and films prefiguring the tone of noir cinema, such as Pépé le Moko and Le jour se lève, began to appear in the late 1930s. The Nazi occupation, by shutting off American films, stimulated the French industry, which during the war produced some important films of crime and suspense. Over the same years Simenon, who wrote both detective stories and psychological thrillers, became a respected literary figure. But it was not until the postwar period that the roman noir became a major literary trend. That was partly due to new publishing initiatives like the Série Noire collection (established 1945), which translated a great many American and English crime writers, and the Fleuve Noir series (1949), which cultivated French authors. Within this lively milieu, the team of Boileau and Narcejac achieved fame with novels that became the sources for Les diaboliques and Vertigo.

The burst of translations of American authors in the 1940s and 1950s paralleled the postwar flood of US films, including films noirs. Truffaut, like his Nouvelle Vague friends, grew up reading crime fiction and watching Hollywood thrillers. He was fourteen years old when Double Indemnity was released in Paris, and twenty-two when Rear Window was. Over those same years crime writers like Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis were being translated in French editions. Writing of Woolrich, whom he knew under the pseudonym William Irish, Truffaut recalled:

The burst of translations of American authors in the 1940s and 1950s paralleled the postwar flood of US films, including films noirs. Truffaut, like his Nouvelle Vague friends, grew up reading crime fiction and watching Hollywood thrillers. He was fourteen years old when Double Indemnity was released in Paris, and twenty-two when Rear Window was. Over those same years crime writers like Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis were being translated in French editions. Writing of Woolrich, whom he knew under the pseudonym William Irish, Truffaut recalled:

The cinephiles of my generation knew Irish before they had read a single line of his, because many of his novels and short stories were the basis of the bizarre and fascinating films of the forties and fifties, such as Jacques Tourneur’s The Leopard Man, Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady, Roy William Neil’s Black Angel, John Farrow’s Night Has a Thousand Eyes, Ted Tetzlaff’s The Window, and especially one of the best if not the best Hitchcock film, Rear Window.

Truffaut came to admire the novels’ authors for their modesty, their professionalism, and their ability to create, behind a pulp surface, “free works” that opened onto sadness, dream worlds, and lost memories.

No wonder, then, that when the young directors sought to make films of wide popular appeal, they turned to noir. If you wanted to generate emotion in a wide audience and to tackle a project that posed formal and technical challenges, some version of the thriller seemed a promising way to go. Claude Chabrol, co-author of a book on Hitchcock, built his career on suspense films, sometimes adapted from English-language authors. More notoriously, Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in USA was an unrecognizable rendering of a crook novel by the great Donald Westlake. As late as 1986 Godard undertook to adapt a James Hadley Chase novel for French television.

Truffaut turned to American thrillers when he wanted a change of pace from his dramas. Naturally the spirit of Hitchcock hovered over such projects. By looking at some problems he faced, we can get another angle on what he learned, or did not learn, from the Master.

As Truffaut became more wedded to shooting in studio conditions, he might have handled scenes with a degree of Stage Fright precision. But he had a predilection for lengthy takes, with fairly open horizontal staging covered in simple, lateral camera movements. Often shooting in anamorphic widescreen, something Hitchcock never did, Truffaut needed to fill up the horizontal expanse, Fluid panning and tracking from a fair distance seemed a good solution. But that meant sacrificing Hitchcock’s urge to build scenes out of details, tight shots of facial expression or close-ups of significant props.

If Truffaut needs a detail, he may accentuate it with an abrupt close-up. In The Bride Wore Black, Julie Kohler wants to be alone with her victim. When the victim’s friend brings her a drink, she dumps it into a flower pot, signaling that he should take off.

Much later, the friend casually waters his own African violet. (Did he inherit his dead friend’s plant?) The gesture reminds him of where he’s seen the woman before. The cut-in detail functions as a sort of flashback for us.

The example indicates Truffaut’s inclination to use close-ups of faces and objects to punctuate the master shot—a more traditional and conservative choice than Hitchcock’s urge to build an entire scene out of bits.

Truffaut confronted larger narrative problems in the thriller genre. One involves the protagonist. In the classic thriller, as opposed to the detective story, the protagonist is either the criminal, the victim, or a bystander drawn into the intrigue (as in Rear Window). And typically our range of knowledge roughly corresponds to that of the protagonist.