Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

The compleat screenwriter: David Koepp gives notes

DB here:

Regular visitors will know of my interest in David Koepp, screenwriter (Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds) and director (Ghost Town, Premium Rush). In 2013 I wrote an entry based on a long interview he kindly gave me.

Back in March of this year, David visited UW—Madison. It’s not strictly his alma mater; he left us to finish up at UCLA. Still, he retains ties to Wisconsin and recalls that while he was here he was inspired by our vast film society scene and some courses in the film and theatre departments. Across 2 ½ days he shared his experiences in a variety of settings, including Q & A’s after screenings of War of the Worlds, The Paper, and Ghost Town.

David is a craftsman who thinks about what he does. I’d call him an intellectual screenwriter if I didn’t think that made him sound more cerebral and austere than he actually is. He’s a vivacious, articulate presence: a born teacher, endowed with wit and good humor. During his visit he threw out plenty of ideas. Some are valuable for aspiring screenwriters, and others are intriguing guides for those of us who study movies.

Career paths

David Koepp and Maria Belodubrovskaya, 12 March 2015.

Starting out: If you want to write screenplays, a post at an agency isn’t ideal. It will, though, help you if you want to become a producer. Likewise, writing coverage can sensitize you to story, but it’s usually not the best route to becoming a screenwriter. It is a good path to becoming a creative executive.

Try to find a job that lets you write every day. A physically exhausting job makes you want to come home and zone out at night, when you should be writing.

Working from models: David learned a great deal from Kasdan’s Body Heat script. He recommends reading the first page of Hemingway’s novel To Have and to Have Not for a strong example of how character and story can co-exist and both start with strength and urgency.

David also urges writers to study plays, especially modern works by Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. [In the discussion, I failed to sell Chekhov as an alternative.]

Prepare for ups and downs, no matter how far you advance. Failure can encourage you to quit, but failure is endemic to the job and must be confronted the way an athlete learns to deal with injury. You must be resilient. “It’s dealing with failure that defines you as a person.”

Creative failures are, oddly, easier to handle if you’re directing because then the decision was yours. You understand how and why the mistakes were made. It’s harder to live with when you feel your script was in perfectly good shape and a director screwed it up or failed to express it clearly.

Maintaining a career

Death Becomes Her (1992).

“The first responsibility of an artist is to pay your rent.”

“Your ideas are your currency.” Talking about your script too much is a mistake. Keep your ideas to yourself as long as you can; otherwise you lose the need to write the script.

The time to talk is at the pitch meeting. It’s a bit disagreeable, but it forces you to have a clear-cut plot. “Until you tell it, you probably don’t have meaningful command of it.” Practice once or twice with a friend before the pitch, but not so many times that it becomes rote.

“Everything after the word no is white noise.”

Your first collaborator is the producer. Take seriously the problems he or she points out, but don’t automatically accept the solutions offered. Other voices are there to raise questions and point out problems, but not to solve them. Don’t let them take that job away from you; you’ll lose your voice.

The trick is to get your vision into the screenplay so that the director and the producer see it as you do. A good script is “all about clarity.” You can’t include camera directions, but every page should have a strong, simple image, briefly expressed. For example, in Death Becomes Her, Meryl Streep is teetering at the top of the stairs, before her husband pushes her down them. The script says: “She hovers there, like Wile E. Coyote at the top of a cliff.” It wasn’t a camera direction, but it called up a certain style in the mind of the reader, and, eventually, the director.

Read your dialogue out loud, playing all the parts.

Be prepared to have to write some things by committee, but, again, listen to the problems pointed out and think about the suggestions. But never let them fix your problems or take command of your story for you. It will lose its distinctiveness. The adage is: “No one of us is as dumb as all of us.”

The creative process

“Appeasing the audience gods”: Who will want to see your story?

The writer’s trance: “You get lost in it if it’s going well.” Play music, especially soundtracks to movies with a similar feel.

David’s steps:

*Thinking: “collecting string,” coming up with ideas on your own.

*Research: reading, interviewing, going on site. For The Paper, David and his brother visited a newsroom and got stories from journalists.

*Outlining: 3 x 5 note cards consisting of the obligatory scenes (“small, unintimidating chunks of story”). The cards can be arranged into five or so columns, corresponding to beginning, middle, and end. The card array gets turned into a prose outline (10-25 pages), with dialogue. “This is the heavy lifting.” At this point, the cards have served their purpose and you probably don’t return to them.

*First draft: Basically, something you can revise from. Those revisions should be successively shorter, so the story is never obscured by excessive description, no matter how well-written. “Scripts are not about pretty writing.” Be ready to cut. “You need less than you think you do.”

The 3-act structure is like musical scales, “something you can embrace or something you can rebel against.” But without some sort of structural approach, “it is all forest, no trees.”

Hollywood rewards success, but it also expects repetition of success. Your job is to try to do something different as frequently as possible. “I tried to write in every genre that interests me.”

Over twenty-seven years, David wrote about thirty scripts. Of them, roughly two dozen got made. Of that number, nine were originals. The most successful original was Panic Room, which was born from two ideas: the popularity of “safe rooms” in urban mansions, and the claustrophobia he once experienced when trapped in a small domestic elevator in a Manhattan townhouse.

Adapting a novel: In adapting, he first writes up an outline of the book itself, as written, to internalize its its structure, before creating the movie’s structure. Don’t worry about imitating the prose texture, especially passages presenting mental states. Film is about images and sounds, visible behavior and speech. But you can be faithful to the spirit of the novel. The War of the Worlds, though an update, respects Wells’ ideas and characterization.

Don’t pass up chances to use your craft; any job can be fun. Some assignments are painting, some are carpentry.

Rewrites may be imposed by studio staff or stars (who often push for a better or bigger role). You have to fight your way through them, taking what can help and talking your way out of ideas that can hurt. “Everything is a negotiation.”

In the shooting phase, the writer is often in a black hole, with nothing much to do. You needn’t be on the set, but do have to stay available if something needs to be done.

Studying film

The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997).

What would David study if he were an academic? “I’d love to take a course that traces influences, such as the connection between Shaw Brothers and Tarantino. In other words, get away from traditional categories of genre and national cinemas and focus on conections of thought and style between apparently diverse filmmakers.”

Would he focus on directors rather than screenwriters? Yes, because the director is “the overriding creative force.” Today a screenwriter needs a director’s support to get a film done. Moreover, directors “have a degree of control you can’t imagine.” They shape performances, tone, imagery, and sound, and they often govern script rewrites. David was struck seeing You Can’t Take It with You on stage and then noticing how Capra’s film version made the play’s amiable patriarch into a capitalist villain–a characteristic Capra touch.

Accordingly, major directors like Fincher become obstinate about details. “You have to be belligerent. There’s no other way.” David was present when Spielberg couldn’t get the overhead shot he wanted in The Lost World: Jurassic Park. The plan was to frame raptors rushing through tall grass from above, so that all we see are trails converging on the fleeing people. But on the first visit to the location, the grass wasn’t tall enough. “If I don’t have the grass,” said Spielberg, “I don’t have a shot.” Tall grass had to be replanted and the shot taken later. [DB: I think that shot is borrowed, somewhat clumsily, in the Wachowskis’ Jupiter Ascending.]

Producers also can control the process. Accordingly, David would also study ones with strong identities like William Castle and Sam Spiegel.

David’s affinity is for classic Hollywood. As a kid watching on TV, he liked horror films and Sherlock Holmes movies. He likes modern films in the classic tradition. When he was 14 he saw Star Wars soon after Jaws, and these had strong impact on him. The only comparable phenomenon today, he thinks, is the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

On noir, especially Snake Eyes

Snake Eyes (1998).

What made him write so many noirish thrillers? Probably his childhood; your tastes are formed between 14 and 24. He experienced the darkness and paranoia of the 1970s, intensified by the fact of his parents divorcing. An important influence was Rosemary’s Baby as well, a film he still reveres.

Filmmakers love noir, but don’t describe your project as a noir. Studios hate the term. They believe it doesn’t sell. Panic Room isn’t a noir, the producers were told; it’s like “an Ashley Judd movie.” [Presumably before that became a problematic term too.—DB]

The morality of noir is tricky. You can have unsympathetic protagonists, but be careful handling the bag-of-money movie. You can’t reward greed. “You can’t get away with the money.” In The Killing, the money has to blow away. True Romance was less powerful, ending with the kids on the beach dancing and rich. This concern isn’t mainly about morality, just an ending that satisfies.

David wrote Carlito’s Way as a 30s Warners gangster film, with a characteristic downbeat ending. Hence the need to lead the audience to expect a dying fall: A flashback and the voice of a “nearly-beyond-the-grave narrator.” The whole movie takes place in an instant.

In Snake Eyes, David welcomed the noirish formal problem of telling the same story three times, as in Rashomon. The tripled presentation would have occupied Act 2. What about the optical POV switches? Typically, shots aren’t fully scripted, and they weren’t here: the POV angles were De Palma’s choice.

Originally the film had a classic noir flashback structure. The opening would show flood waters after the storm, with floating chips, playing cards, and a blackjack table. Then the main story would take us into the past. The climax, back in the present, was to have been a fight in the water with Sinese trying to drown Cage.

As for giving away a key element midway through: David thought it would work. (Hitchcock did it in Vertigo.) But audiences didn’t like it. They seem to feel uncomfortable knowing something big that the main character doesn’t. But what about a movie like Ransom, which also reveals the villain? Not such a problem, says David, because if you show a character lying, you should do so quickly—not hold off for many scenes and reveal it a fair distance from the climax.

“This is the fun part of storytelling: What do we tell ‘em, and when?” [DB: In Film Art, we put it this way: “Who knows what when?”]

Envoi

What about the writers’ tasks in the late phases of preproduction? As I was finishing this entry, David sent a dispatch from Inferno, Ron Howard’s latest Dan Brown adaptation. After moving from Budapest to Florence to Venice, the production starts shooting tomorrow. David writes:

David Koepp visiting the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, with Vance Kepley, Director; Amy Sloper, Head Film Archivist; and Mary Huelsbeck, Assistant Director.

They had time for everything then

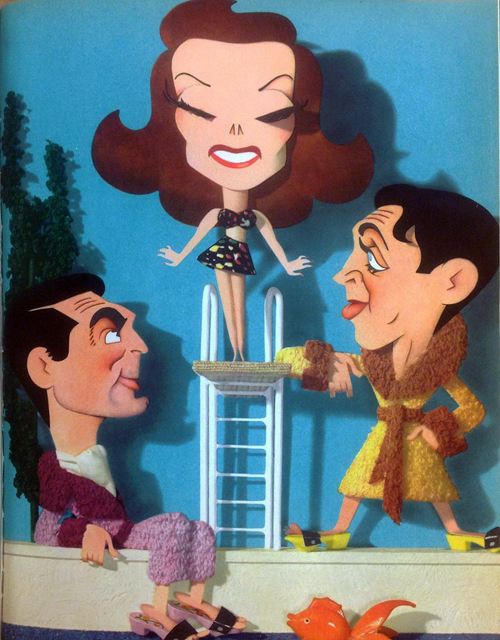

Advertisement for Woman of the Year. From Hollywood Reporter (23 April 1942), 5.

During the 1940s, MGM promoted some of its top pictures with unique illustrations. The artist would make cutout caricatures of the stars, dress them in fabrics, and then prepare little shallow-relief scenes, with props made of wood, carpets, and other stuff. Above, the microphones seem made of metal and plastic, and Tracy’s coat has real buttons attached. Below, the men’s slippers are three-dimensional, as is the toy goldfish and, I suppose, the diving board.

The little tableau would then be photographed, in luscious color. Some were printed with elaborately embossed borders.

I say “the artist” because he or she goes unidentified on these advertisements. The only signature is an enigmatic “K”; in the image above, it’s on the tiny baseball at the bottom. If anyone knows who K is, or can supply further background, please correspond.

Interestingly, these charming images continued to be published from time to time through the early years of the war. I’m afraid my reproductions don’t do them justice, but you get the idea.

Damn, but film research is fun.

P.S. 24 April 2015: Ask and ye shall receive. Alert reader Mark Schoenecker writes:

I’m sure you’ve already received correspondence naming the identity of the mysterious MGM illustrator responsible for those distinctive 3D paper sculpture pieces from the 30s and 40s — but in case you haven’t, his name is Jacques Kapralik. I’m an illustrator myself and have always been vaguely aware of the existence of these cut-out posters. What I didn’t know was that one man was behind them. I’d assumed it was a style prevalent during that era. It wasn’t until I found myself drawing my own series of caricatures in a similar vein that I decided to track down the originals online to see if I was remembering them accurately.

Here is a link to the most interesting article I came across: https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/movie-poster-of-the-week-the-jacques-kapralik-archive

I should’ve known that the indispensable MUBI would have something on this. It’s a fine piece of work by Adrian Curry, showing that Kapralik did movie title sequences as well. Be sure to check the links in that entry and the comments. The University of Wyoming holds Kapralik’s collection, and an online finding aid gives access to many of his beauties.

Many thanks to Mark for clueing me to this. You should immediately check Mark’s own lively, dry, and sometimes scathing, caricatures here. Who else thinks of drawing Dorothy Kilgallen and Korla Pandit?

Advertisement for the The Philadelphia Story. From The Hollywood Reporter (31 December 1940), 7.

1932: MGM invents the future (Part 2)

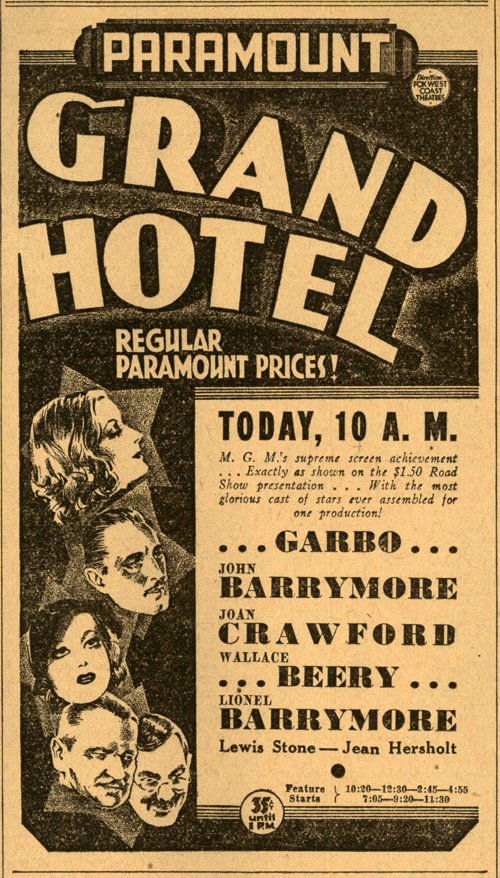

Courtesy John McElwee and his gorgeous, informative site Greenbriar Picture Shows.

DB here:

The inner monologue, as a report of a character’s immediate thoughts, seems to have been rare in 1930s films; it became more prominent in the 1940s. But the second big MGM narrative innovation of 1932 was almost instantly influential, redone and nearly done to death in the decades that followed. Even before the film was released, the idea of a “Grand Hotel plot” had gripped both the public and professional storytellers. And it never went away.

In the Strange Interlude entry, I mentioned that what’s usually of interest to us when we try to track the history of film forms is not the first time something is done but the moment when it becomes recognized as an active option. It stands forth as a strategy that can be copied, standardized, and revised. The Grand Hotel idea itself wasn’t utterly new, but the novel, play, and film of that title crystallized it as a distinct choice on the filmmaking menu.

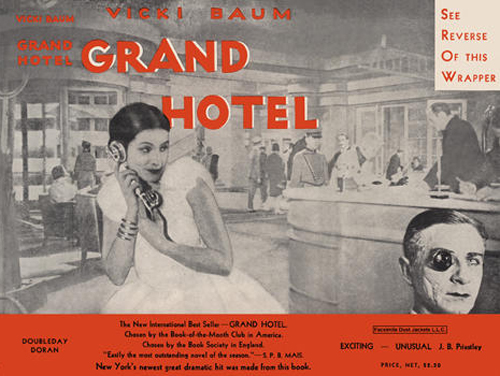

The book: Only approximations

Vicki Baum, an emerging German novelist, launched Grand Hotel as a magazine serial. It was published in book form in 1929 as Menschen im Hotel and became a huge seller. The following year saw Baum’s international breakthrough. In January a stage version opened in Berlin. It migrated to Broadway in November and enjoyed huge success. Meanwhile, a British publisher brought out an English translation. In February of 1931, Doubleday published an American edition. That month Baum arrived in Hollywood to work on the screenplay for what she called her “star-studded wedding cake.”

The central story remains constant in all the media versions. Three men converge in Berlin’s Grand Hotel, each with his own aims. Baron von Gaigern is a penniless aristocrat who has taken to theft. The provincial bookeeper Kringelein has been diagnosed with a fatal disease, so he has vowed to enjoy the good life before he dies. He demands a costly room and plans to wine, dine, and gamble his savings away. The business mogul Preysing is there to meet with potential partners in a big business deal. Preysing, it turns out, is the owner of the company employing Kringelein.

The men’s plans pull two women into their orbit. There is the glamorous but fading dancer Grusinskaya. She meets the Baron when he slips into her room to steal her pearls; during that night of sexytime they fall in love. Then there is the stenographer Flaemmchen, who takes a liking to the Baron but who is dominated by Preysing. He has hired her to record his deal-making, and he soon invites her to be his mistress. Add in secondary characters like the porter Senf, who at the start is waiting for news of his wife’s delivery of their baby, and Dr. Otternschlag, a disfigured war veteran who drifts around the lobby mournfully observing life.

The men’s plans pull two women into their orbit. There is the glamorous but fading dancer Grusinskaya. She meets the Baron when he slips into her room to steal her pearls; during that night of sexytime they fall in love. Then there is the stenographer Flaemmchen, who takes a liking to the Baron but who is dominated by Preysing. He has hired her to record his deal-making, and he soon invites her to be his mistress. Add in secondary characters like the porter Senf, who at the start is waiting for news of his wife’s delivery of their baby, and Dr. Otternschlag, a disfigured war veteran who drifts around the lobby mournfully observing life.

The novel’s action consumes three days and nights, with an epilogue on the morning of the fourth day. Each major character undergoes a crisis triggered by meeting others in the hotel. Preysing catches the Baron in his apartment, bent on robbery. In beating the Baron to death, Preysing ruins his life; he is arrested and his family leaves him. Flaemmchen, about to go off with Preysing, attaches herself to Kringelein and vows to help him recover his health. Grusinskaya, who has left Berlin for her tour date in Prague, calls the Baron’s room in vain, unaware that she will never see him again.

The book offers several attitudes toward the interwoven destinies. There is that of the grim Dr. Otternschlag, who sees in the lobby’s revolving door a ceaseless cycle of mundane suffering. “Always the same. Nothing happens. . . . And so it goes on. In—out, in—out.”

The bellboy looks at the same door and sees endless variety: “Marvelous the life you see in a big hotel like this. . . . Always something going on. One man goes to prison, another gets killed. . . .Such is Life!”

The omniscient narration provides another attitude, seeing in the door an image of life’s ephemeral, fragmentary quality.

The revolving door twirls around and what passes between arrival and departure is nothing complete in itself. Perhaps there is no such thing as a completed destiny in the world, but only approximations, beginnings that come to no conclusion or conclusions that have no beginnings.

All three musings represent, we might say, alternative ways of reading the novel: as an eternal return, a varied pageant of human drama, or scattered glimpses of incomplete lives.

Play and film: Call waiting

National Theatre production, New York 1930.

The novel spreads the action to the theatre, a casino, and an airplane flight, but the stage version confines itself wholly to the hotel. The play begins with a coup de théâtre for which Baum claimed the credit. Preysing, Kringelein, the Baron, Flaemmchen, and Grusinskaya’s maid Suzanne are introduced in a line of telephone booths, each making a quick phone call. The light in each booth flashes on and off as each one speaks. The pace builds until each speaker is “intercut” rapidly with another. Baum claimed that this pulsating sequence drove the opening-night audience to a frenzy of applause. Snazzy as it is, the prologue serves as crisp exposition, literally spotlighting nearly every major character, with Suzanne acting as a proxy for the dancer Grusinskaya. Then the revolving stage whisks us to a broad view of the lobby teeming with guests and staff.

The novel can proceed in a fragmentary way, shifting from one character to another, but the play contrives a more fluid rhythm of encounters. At the start, several characters assemble at the front desk, and after a “cutaway” to Grusinskaya’s room, we’re back in the lobby with Flaemmchen, the Baron, and Kringelein chatting while Preysing and his colleagues head off to their conference. Later all the major characters except Grusinskaya, who’s often marked as separate from the others, meet in the hotel bar and grill. At the conclusion, as characters depart, overlapping encounters carry Flaemmchen out the door with Kringelein, and Grusinskaya leaves for Prague wondering why the Baron has failed to meet her. The spatial concentration of the play squeezes the characters’ trajectories together more tightly than the novel does.

The film does much the same thing. When head of production Irving Thalberg bought the rights to Baum’s novel, he had to buy the stage rights as well, and so MGM funded the Broadway production. It garnered over a million dollars in its first year.

Claus Tieber points out that having seen the play, Thalberg insisted that the bits that pleased the Broadway audience had to stay in the film. No wonder that the film sticks close to the stage version. Although sequences are added, they seem in the spirit of the play’s swift pace. An American critic had described the book’s rapid changes of scene as like a film: “interlocking adventures, a little too easily linked perhaps, flit from screen to screen [shot to shot?].” Baum agreed:

I realized what had made my Grand Hotel, the novel and the play, a world success: it was probably the first of its kind to be written in a sort of moving picture technique. By now [1964] that’s the oldest of old hats, but in those days the kaleidoscopic effects, brief ever-changing scenes, flashes, staccato dialogue, were new, surprising, and exciting…on the stage. On the screen, I felt, this technique was the usual old stale shopworn thing.

In a crucial expansion of both book and stage show, the film emphasizes the telephone switchboard, marking the hotel as the crossing point of many destinies. After Preysing has beaten the Baron to death with a phone receiver, the switchboard is ominously stilled at the climax.

The prologue shows other protagonists making calls, but Grusinskaya, because of her isolation from the others, works the phone in the bulk of the film. Her final call for the Baron goes unanswered, heard only by his dog.

The play had enhanced the women’s roles, and the film goes farther by casting two top stars, Greta Garbo as Grusinskaya and Joan Crawford as Flaemmchen. With three strong male leads—Wallace Beery as Preysing, Lionel Barrymore as Kringelein, and John Barrymore as the Baron—the film became an ensemble drama that gave more or less equal weight to five characters. Accordingly it became known as the first “all-star picture.” On its tenth anniversary Variety proclaimed that it “disproved the contention that no picture could support a huge all-star cast.”

Even putting the cast aside, Grand Hotel crystallized a narrative option that had been emerging, more or less explicitly in the years before.

Networks and cross-sections

We can think of the Grand Hotel format as one variant of what I’ve called network narratives. Putting it generally, these are films that shift our attention across several somewhat linked characters and their projects.

Most films we encounter have a single protagonist, accompanied by helpers and facing some number of antagonists. Other plots have dual protagonists, perhaps cops who are buddies, or a man and a woman in a romantic relationship. A few films may have three protagonists, like Letter to Three Wives.

Another variation is the film with several protagonists, each given roughly equal weight. Usually the multiple protagonists share a goal, as in combat films, where they are united in a common mission. But when we have multiple protagonists pursuing different, largely unrelated goals, we have what I’m calling a network narrative.

What makes all these characters part of the same network? Any social relation. They might be relatives, friends, co-workers, classmates, neighbors, ex-lovers, or whatever. Also, mere proximity can connect characters; maybe they’re in the same hospital room or conference meeting or just in the same town.

As the film unfolds, we come to understand the array of characters and their connections. We follow one, then another, and we watch new relationships form. Sometimes hidden relationships are revealed to create a surprise. Some connections are distant, of the n-degrees-of-separation variety. The characters’ various purposes may run parallel, or they may intersect and clash—all more or less accidentally. Most plots of any sort are connected by causality, but network narratives are once tight (because of the pressure of the characters’ goals) and loose (because social ties can flow in many directions).

The advantage of the network approach is to yield a cross-section of life denied to more traditional linear narrative. Such plots can present, as Joseph Warren Beach puts it, a “comprehensiveness of view” that becomes “a composite picture of many distinct lives.” But the strategy raises problems too. The idea of a network narrative invites a dizzying expansion. X meets Y, who’s married to Z, the friend of A, who works with B, and pretty soon your story world is growing out of control. You need to constrain it somehow.

One way, as in Slacker, is just to sample one string of the network, moving from node to node. This generates a sort of “slice of life” plot, in the manner of Naturalist theatre. That snatches a few episodes from central characters’ lives without the customary setups and resolution. Bernard Shaw noted that “The moment the dramatist gives up accidents and catastrophes, and takes ‘slices of life’ as his material, he finds himself committed to plays that have no endings.” In film, we might think of one prototype of Neorealist cinema, The Bicycle Thieves. Baum’s framing narration of Grand Hotel, with its musing on stories without clear-cut beginnings or resolutions, tries for the same sense of what Zola called “a fragment of existence.”

Some of the literary models, such as The Lower Depths, accept a slice-of-life approach, without traditional climaxes and resolutions. Modernist writers pushed this possibility further, very open-textured networks. Dos Passos’ USA trilogy (1930-1936) is one example. Evelyn Scott’s The Wave (1929) presents seventy episodes from the Civil War, each concentrating on a different individual, although some characters reappear in sections devoted to others. A comparable strategy rules William March’s Company K (1933), with its 131 vignettes of World War I, with each soldier’s scene narrated in first person. Again, some characters reappear, but the network is largely a dispersed one.

Novels with well-defined protagonists occasionally strayed into a more lateral, open-textured approach. One example is the Wandering Rocks section of Ulysses, which fleetingly probes the minds and actions of about a hundred Dubliners moving through mid-afternoon. In Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), a sudden noise from a car stuck in traffic, followed by an airplane swooping above, causes various members of a crowd to think stray thoughts. Like Joyce, Woolf momentarily broadens the frame to register the reactions of characters unconnected with the protagonists, except by being present outside Buckingham Palace at the same moment. Only space and time create this network, and it’s ephemeral.

Bring us together

Given our appetite for linear narrative, some storytellers are bound to seek ways to tighten things up. Can we graft normal plot development—goals, conflicts, rising tension, climaxes, and resolutions—onto the network idea?

Yes. One way is to create the network through a circulating object, as in Tales of Manhattan, Au hasard Balthasar, American Gun, Twenty Bucks, or The Earrings of Madam de…. Sometimes the result will be episodic, but other times there will be a rising tension and a conclusion to at least some lines of action.

The most common way to constrain the network is to multiply the connections within the group. That is, don’t make the network loosely woven. So X meets Y, who’s married to Z, the friend of A; but A works with X, who is the cousin of B, who has been having an affair with Y, and so on. In other words, you create a “small world” defined by several connections among all the participants.

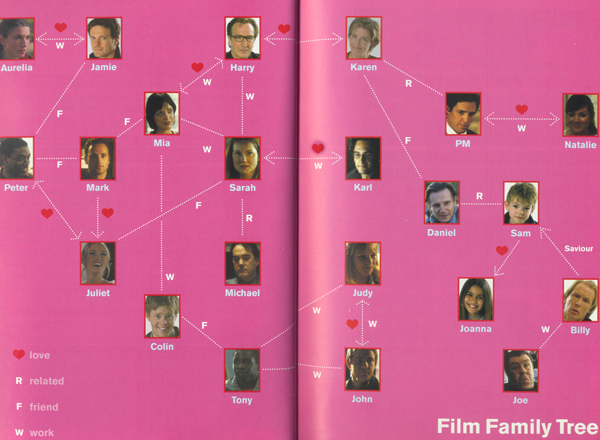

This small-word model is common in novels that create network narratives. Dickens, Balzac, and other writers have created complex degrees-of-separation plots. It’s likewise the pattern for most network narratives on film: several connections link many of the nodes. Here’s a diagram for Love Actually.

This chart is oversimplified because it doesn’t account for other relationships. Colin, for example, as the sandwich delivery boy, interacts with several of Harry’s employees. Still, at a glance you can see a fairly tight network.

Another way to constrain the network is to set limits of space and time. Slacker, like Mrs. Dalloway, explores a network established by spatial proximity; when we leave one character we pick up another nearby. The circulating-object option often presumes that the characters share a locale. Love Actually limits its intertwined stories to London, and still further to the Christmas season there. Louis Bromfield’s 1932 novel Twenty-Four Hours follows its Manhattan ensemble through one full day. (Compare that unlamented recent release, Valentine’s Day.) A 1938 British film, Bank Holiday traces several people across a weekend at a seaside resort.

The space can be more radically limited, as in Waldo Frank’s book of interconnected short stories City Block (1922). Perhaps influenced by Frank’s book, Elmer Rice wrote and staged Street Scene, a 1929 play that weaves together the lives of people living in a tenement. Their relationships are played out on the building stoop and the street in front. The play was filmed in 1931, and perhaps if it had been more successful, or had featured many big stars, we’d be talking about “Street Scene plots” rather than Grand Hotel ones.

Buildings are ideal for tying story lines together. Zola’s novel Pot-Bouille (1882) confines its action largely to an apartment house and the people who live there. Gorky’s play The Lower Depths brings together several characters in a flophouse. Inns, taverns, and hotels are natural points of convergence, and travelers naturally bring story action along with them. This is the narrative convention of l’auberge espagnole, based on the idea that in a Spanish inn you bring your own food.

When we have mostly strangers interacting in a constrained time and space, and when those interactions lead to traditional conflicts and resolutions (avoiding the slice-of-life pattern), we can speak of “converging-fates” narratives. Grand Hotel became the great prototype of converging-fates plotting.

Baum modernized the auberge espagnole idea by concentrating the action in a luxury hotel. She understood that these surroundings could motivate the chance meetings that propel the plot. She wasn’t alone. At the time her book was published, there were other “hotel” novels, notably Arnold Bennett’s Imperial Palace (1930). Whereas Bennett emphasizes the hotel staff and its routines, Baum concentrates on the guests. She motivates her comparisons across classes by making Kringelein a poor man having a final fling and making the Baron a penniless aristocrat keeping up appearances.

Baum showed how filmmakers who wanted an ensemble plot could bypass the sort of fragmentary, open-textured network seen in Dos Passos, The Wave, or Company K. She showed how to build more tightly integrated situations, with intersecting characters, each pursuing his or her goals and unexpectedly affecting other characters. The whole dynamic would take place in a rigorously confined setting and a sharply bounded period of time. The disparate story lines, knotting in certain scenes, would build to a climax. In Grand Hotel, all the characters’ fates come together when Preysing kills the Baron. Flaemmchen, terrified, rouses Kringelein and brings him into the crisis.

In such ways, a network narrative could become a variant of classical plotting, complete with exposition, conflict, crisis, and climax. Now Baum’s claim that the book traces mere fragments of life seems to be camouflage. Each protagonist’s fate has a linear logic; it’s just that the lines intersect.

If you’re a modernist, you find this a dilution of strong brew. You deplore the way fiction writers and moviemakers adapt avant-garde techniques to middlebrow taste. Yet if you’re a mainstream filmmaker, you can see that absorbing these techniques freshens up the norms. The crisscrossing destinies create an urgent pace, a new openness to chance and accident, and an invitation to imagine a patterning beyond that of straightforward single- or dual-protagonist plotting. Hollywood may feed on more “advanced” storytelling, but it doesn’t simply iron out the difficulties; in absorbing the techniques, it enriches its own traditions.

Thalberg predicted this change when the film was in production.

I don’t mean that the exact theme of “Grand Hotel” will be copied, though this may happen, but the form and mood will be followed. For instance, we may have such settings as a train, where all the action happens in a journey from one city to another; or action that takes place during the time a boat sails from one harbor and culminates with the end of the trip. The general idea will be that of a drama induced by the chance meeting of a group of conflicting and interesting personalities.

The last sentence isn’t a bad encapsulation of the converging-fates schema.

Hotel franchising

Thalberg was right, of course. Grand Hotel, in all its incarnations, encapsulated a narrative option that was irresistible. By 1955 Kenneth Tynan paid tribute to the fertility of the idea.

No literary device in this century has earned so much for so many people. Unite a group of people in artificial surroundings—a hotel, a life-boat, an airliner—and, almost automatically, you have a success on your hands.

Baum compared herself to the sorceror’s apprentice, who couldn’t stop her creature from splitting and rushing off in all directions. Critics detected traces of the novel and play in Translatlantic (1931), Union Depot (1932), and Hotel Continental (1932), all released before the MGM vehicle. These films do confine most of their action to a single setting, but they don’t multiply protagonists to the same extent as the original. A 1932 play, Life Begins, is closer to Baum’s model, finding converging destinies in a maternity ward. Some suspected that the 1932 film, released in May, was Warners’ effort to compete with Grand Hotel, premiering in April but not going wide until summer and fall.

MGM imitated itself in another 1932 release, Skyscraper Souls, which applied the formula to an office building. Faith Baldwin’s original novel Skyscraper focused on a working-girl romance, but the screenplay expanded the plot. A great many characters working in the skyscraper get involved in love affairs, a stock swindle, and an aborted jewelry theft. As with Grand Hotel, all the action transpires in one building.

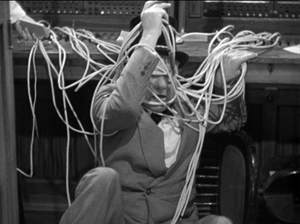

Like Strange Interlude, Grand Hotel inspired parody. In Paramount’s International House (1933) various personalities converge on a hotel in Wu-Hu, China, to buy the rights to Dr. Wong’s “radioscope” (aka TV). W. C. Fields, Stuart Erwin, Bela Lugosi, Franklin Pangborn, Cab Calloway, Rudy Vallee, George and Gracie, and the notoriously torrid Peggy Hopkins Joyce enliven the proceedings. There’s an allusion to the hotel switchboard in the original film when Fields gets tangled up in phone cables. He’s also flummoxed by Gracie Allen.

After one of Gracie’s non sequiturs Fields asks: “What’s the penalty for murder in China?”

A curious parallel surfaced in Die Wunder-bar, a German play premiered in February 1930, just a month after the opening of Grand Hotel’s stage version. Transposed to film, it became an Al Jolson vehicle, Wonder Bar (Warners, 1934). It has a fairly coherent threads-of-destiny plot. Flirtations, suicides, and musical numbers (including one with Al in blackface, of course) fill out action occurring in a single day. There was also Die Uberfahrt, a 1932 novel by Gina Kaus, translated as Luxury Liner and filmed under that title by Paramount in 1933. Variety called Wonder Bar “a ‘Grand Hotel’ of a Paris boite-de-nuit,” and Motion Picture Herald called Luxury Liner “Grand Hotel on a steamboat.”

The Grand-Hotel-on-an-X formula became a catchphrase, like Die-Hard-on-an-X of years later. We associate the phrase “Grand Hotel on wheels” with Stagecoach (1939) because that was used in its publicity. But reviewers had applied that phrase earlier, to Streamline Express (1935) and Time Out for Romance (1937)—the former involving a train, the latter an automobile convoy. The British import Rome Express (1933) was “Grand Hotel on a train” and Mitchell Leisen’s fine Four Hours to Kill (1935), set in a theatre lobby and lounge, became “Grand Hotel in miniature.” Fifty-four Ames Street, a screenplay apparently never filmed, was said to be “a sort of Grand Hotel in a New York apartment house.” Producers interested in Saroyan’s play The Time of Your Life saw in its tavern locale and migrating flocks of characters “an all-star vehicle somewhat along the lines of ‘Grand Hotel.’”

One critic worried that Winter Carnival (1940) was tantamount to “Grand Hotel on skis,” but F. Scott Fitzgerald, sweating over the script, had worried that it couldn’t be “a group picture in the sense that Stagecoach was, or Grand Hotel.” It had, he noted, “no sense of destiny.” That sense was much stronger in One Crowded Night (1940), an RKO B that I’m fond of. It might be called “Grand Motel,” as it brings together a preposterous number of plotlines at a desert auto court.

The Grand Hotel paradigm did not rest. The original film was remade, in more complicated form, as Week-End at the Waldorf (1945). There were other variants of the template—famously Lifeboat (1943) and Hotel Berlin (1945), less notably Ulmer’s Club Havana (1945) and the PRC cheapie The Black Raven (1943). Life Begins was redone as A Child Is Born (1940), and at the end of the decade Harry Cohn expressed interest in remaking it again. The play Flight to the West (1940), set on an airplane, showed Elmer Rice contributing to the trend.

By 1943, a Variety columnist was admitting that there was a tradition behind it all. “Ever since Boccaccio rounded up a herd of characters in his Decameron, dramatists have been utilizing the restricted space idea to make their stories more compact.” What he did not say was that most of Grand Hotel knockoff movies had been B-pictures.

Baum bitterly resented what had happened to her most famous work. “Countless cheap imitations and adaptations gave it a bad name. . . It all quickly became a mechanical toy. A formula, to be bought and sold on the supermarket.” That didn’t stop her from ringing changes on her model. Her play Pariser Platz 13 (1930), set in a beauty parlor, and her novel Martin’s Summer (1931), tracing a drama among strangers at a vacation resort, inevitably recalled her breakthrough work. She mined the vein again with Hotel Shanghai ‘37 (1939) and Hotel Berlin ’43 (1944). Things became risible when Variety announced that she was preparing a (never-filmed) screenplay called Grand Central Market, based on an idea by a busboy in the MGM commissary. But perhaps she wouldn’t have minded the jeers that she was milking her most marketable idea. “I know what I’m worth: I am a first-rate second-rate author.”

Catch them coming or going

The Grand Hotel converging-fates format got recycled for decades, in movies from The V.I.P.s and Hotel to Four Rooms and Auberge Espagnole. Network narrative as a general trend came back in a big way in the 1990s. In an essay for Poetics of Cinema, I counted some 148 examples just from the period between 1994 (Pulp Fiction, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Ready-to-Wear, Chungking Express, Exotica) and 2006 (Bobby, Colossal Youth, Selon Charlie), by way of Do The Right Thing, Magnolia, Sunshine State, Wonderland, and Happiness. Filmmakers, mostly non-Hollywood ones, revived and reformatted the old template. They could cunningly resolve some story lines, and so satisfying our fondness for closure, while also leaving some unresolved, and so satisfying our belief in realistic “slices of life.”

Although I should be fed up with such plots, I still find them intriguing. They can yield mystery, as we’re teased about the possible connections among the characters; their network pattern can be revealed or obscured by flashbacks, subjective sequences, frame stories, forking-path patterns, and other devices, as in Go and Once Upon a Time in Triad Society 2. The format can really test the ingenuity of a screenwriter.

Still, network plots pose unique problems. One is figuring out all the interactions in situ. How do you weave everything together? Apart from kinship and friendship, the easy links are chance encounters, merely passing in the street, watching somebody on TV, or, most desperate of all, the traffic accident. (Crash is only the most egregious instance.) Finding fresh ways to hook up your nodes is quite a challenge, as is devising a satisfying payoff for at least some of them.

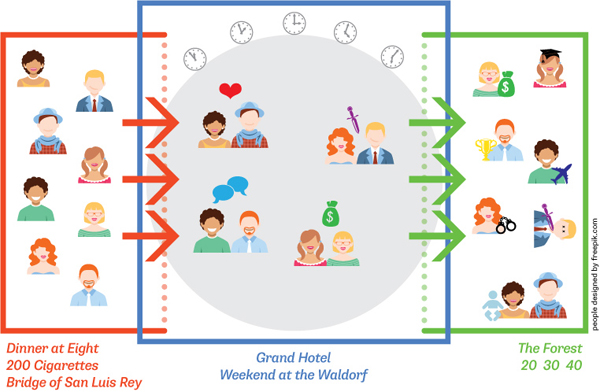

Another problem is more specific to the converging-fates option: the choice of “point of attack.” Taken just as geometry, the plot can be seen as having three phases. Here’s an infographic courtesy of our web tsarina Meg Hamel. On the left, the characters are independent. In the center–a closed environment like a hotel, or a more porous one like a holiday season–they are drawn together. They circulate and interact. On the right, we see them dispersing, all changed in one way or another.

The question is: Where do you cut into this process to start and end your plot? Some films, like In Which We Serve, try to trace the whole process more fully. We see it in a more spacious form in The Great Race and Cannonball Run. Perhaps The Rules of the Game would be another instance.

But most films of this ilk concentrate on the convergence, the central circle of interaction we see in Grand Hotel. That’s what we find in Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame, The Uchoten Hotel, Drive-In, Health, The Yacoubian Building, Monsoon Wedding, et al. Often there’s a time pressure too, as the clocks in the graphic indicate.

Or you the screenwriter could shift a step back and base your plot on the action before the characters commingle. My red block indicates a plot concentrating on this early phase. The dotted line indicates our seeing a little bit of the convergence.

The prototype is probably Dinner at Eight, a 1932 play made into a 1933 film (yes, also by MGM). The comic plot traces several couples invited to a dinner party. Some of them have one-off encounters before the big night, but the plot depends on the eventual convergence of everyone. The film stops just as the assembled guests step into the dining room. A modern parallel is 200 Cigarettes, which intercuts several guests on their way to a party. Again, we don’t see the party directly, but in an epilogue a montage of snapshots gives us some glimpses.

Probably the most famous example of pre-convergence plotting is the novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Thornton Wilder uses a flashback construction to trace the lives of the characters. At the start we learn that the bridge collapsed, killing them all, and then via an inquisitive priest we are taken back to the events that brought them to the same fate. By contrast, Claude Lelouche’s Il y a des jours…et des nuits saves the moment of convergence for a traffic tieup at the very end of the film.

Alternatively, you could build your plot at the other end, as indicated by my green box. Your story action begins with the dispersal of the characters who have already converged, though perhaps you show something of their encounters before they split up.

This is the rarest option, I think. One example is Benedict Fliegauf’s The Forest, which shows several people leaving a train station and proceeding on to their parallel, and fairly mysterious, lives. A more heavily motivated example is Sylvia Chang’s film 20 30 40, which initially brings three women together as passengers on an airplane flight before sending each off to her own pursuits. Although they live in the same neighborhood and their activities are intercut, the women never meet. Two films I haven’t seen seem to follow this parallel-dispersal pattern. In Urlaub auf Ehrenwart (Leave on Word of Honor, 1938), a commander gives his men leave for a day on their way to the front, and the plot follows each one’s experiences. It was adapted into a Japanese film, The Last Visit Home (Saigo no kikyo, 1945).

As with any plot scheme, the closer you look, the more variations and extensions you see. Sometimes it’s useful to see any one plot as a reconfiguration of other plots. The network principle–itself a threading of goal orientation, conflict, and other narrative devices–can be a beautiful meeting point of story possibilities. One reason I think filmmakers like these plots is that, somewhat like mystery stories, they are narrative to the nth degree. How many situations, characters, and unexpected connections and analogues can you squeeze into a single movie? It’s a challenge.

What crystallized in an MGM prestige production of 1932 seemed a fresh approach to film narrative. Even in the opportunistic ripoffs of the following decades, we can sense an excitement in tinkering with a new storytelling pattern. And of course some variants still seize us today. Just ask the audience making its way to The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, or the young hipsters immersed in the mini-library that is Chris Ware’s Building Stories. Lately we haven’t seen many network movies, but I expect another wave. Like it or not, some story ideas never die.

My information about Vicki Baum’s career comes from Lynda J. King’s Best-Sellers by Design: Vicki Baum and the House of Ullstein (Wayne State University Press, 1988). I drew my Baum quotations from two curiously different editions of her memoirs, I Know What I’m Worth (Joseph, 1964) and It Was All Quite Different: The Memoirs of Vicki Baum (Funk and Wagnalls, 1964). The reviewer who called Baum’s novel cinematic was Herman Ould in “Experiments in Technique: Vicki Baum and Arnold Zweig,” The Bookman 79 (November 1930), 132.

Claus Tieber analyzes the Grand Hotel story conferences in “‘A story is not a story but a conference’: Story conferences and the classical studio system,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (2014), 225-237. In correspondence Patrick Keating has shared with me a story conference concerning Skyscraper Souls (MGM, 1932), in which the participants discuss transitions between scenes. Should the film cut from one plotline to another, or use camera movements, or have the characters link to one another? The filmmakers discuss Grand Hotel as a model for handling the problem. Thanks to Patrick for the information.

Joseph Warren Beach provides a helpful survey of experiments in mainstream fiction of this period in The Twentieth Century Novel (Appleton Century Crofts, 1932). I’ve drawn upon his chapter “The Breadthwise Cutting.” Shaw’s remarks on the slice-of-life plot are in his Preface to Three Plays by Brieux (Brentano’s, 1913), xv-xvi. In The Writing of Fiction (Scribners, 1924) Edith Wharton comments that English novelists of the early nineteenth century favored the “double plot,” a form that presented “two parallel series of adventures, in which two separate groups of people were concerned, sometimes with hardly a link between the two” (81). She considers this a “senseless convention,” but it seems to me another means of creating a network narrative. Sometimes the nodes connecting the groups become clear only gradually. There may be even a dose of mystery, as in Our Mutual Friend; the reader is encouraged to wonder how the two ensembles might be hooked up.

The diagram of the network in Love Actually comes from Peter Curtis, Love Actually (St. Martin’s, 2003), 6-7. Although at least one story line in the film doesn’t get fully resolved, Curtis is committed to a classical model: “I thought I’d like to have a go at writing that kind of film–to see if it was possible to write a film with nine beginnings, nine snappy middles and nine ends.” He declared himself inspired by Nashville, which I’d argue has a much looser texture and treats its story lines largely as slices of life.

Kenneth Tynan’s remark comes from his 1955 essay “Thornton Wilder,” reprinted in Profiles, selected and edited by Kathleen Tynan and Ernie Eban (Random House, 1995), 106. My citations of critical commentary on various films comes from the Hollywood trade press, as indexed in Lantern. Thalberg’s remark on Grand Hotel‘s likely influence is quoted from “Producer Discusses Pictures,” New York Times (3 May 1931), X6. Peter B. High discusses The Last Visit Home in his The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 485-487.

My fullest treatment of network narratives is in Poetics of Cinema, in the essay “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance.” To the same subject Peter Parshall devoted an insightful book, Altman and After: Multiple Narratives in Film, which I plug here. A search of our site with “network narrative” as the key phrase will turn up several remarks on the format.

P.S. 23 March 2015: Thanks to Antti Alanen for a correction: I had accidentally written that Pot-Bouille was by Balzac, not Zola.

P.P.S. 31 March 2015: Rewatching Skyscraper Souls, I added a paragraph about it, which better sets up Patrick Keating’s information in the codicil. It’s a pretty good movie, in some ways more complex than Grand Hotel.

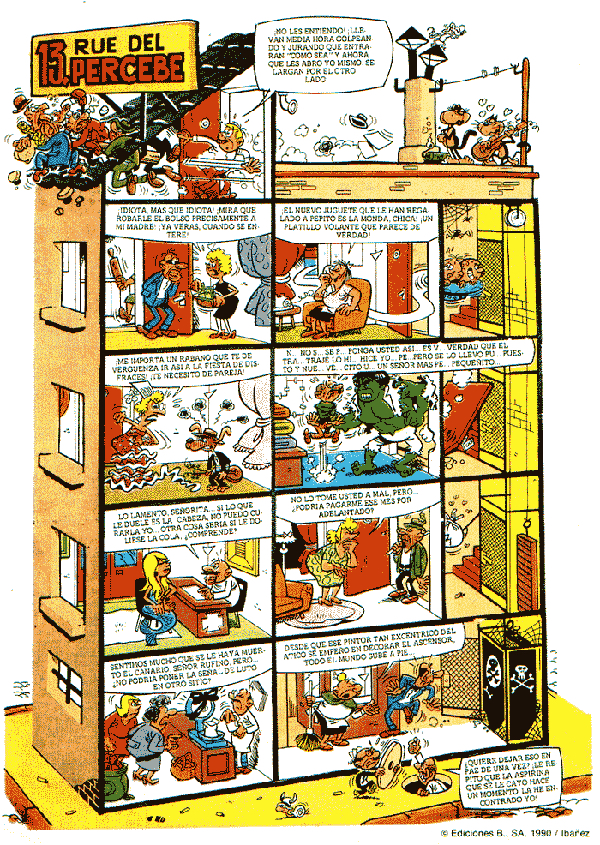

Francisco Ibáñez, 13, rue Percebe. With thanks to Vicente J. Benet.

1932: MGM invents the future (Part 1)

DB here:

Seldom can we point to a moment when a movie convention is born. When, exactly, did crosscutting for suspense start? (Not, apparently, with Griffith.) What was the dissolve first used to convey the passage of time? What film first updated us on story developments by whipping newspaper headlines up to the camera?

We’re rightly discouraged from asking such questions. For one thing, we probably can’t answer them; too many films are lost. And what may matter is not the first time a technique is used but the process by which it becomes normalized and widespread. That’s when it achieves significance in the history of film forms.

Still, occasionally we might be able to pinpoint a crystallizing moment, when the convention assumes a distinct identity. The problem then becomes tracing the uptake, the process that makes the convention standardized enough to be understood by audiences.

In working on Hollywood narrative conventions of the 1940s, I’m drawn to moments in earlier decades when certain storytelling devices seem to emerge, although maybe only in partial or bastardized or confused forms. Here’s an example.

We don’t usually look to the MGM of this period as a hotbed of innovation. We think of it as the star-glutted studio that under Irving Thalberg turned out plump, well-upholstered productions of classics like David Copperfield (1935) and Romeo and Juliet (1937). Yet the search for prestigious productions led two releases of 1932 to become benchmarks of cinematic storytelling. Those two films launched conventions that are still with us.

The one I’ll consider today involves voice-over sound. I’ll examine a second one in a later entry.

The voice within

The Fallen Sparrow (1943).

Like most terms of craft, voice-over has several meanings.

In one usage, voice-over is what we hear when a narrator recounts information during a flow of images. An external, voice-of-God commentary like that opening The Roaring Twenties (1939) is one example.

Or a character in the story may be recounting what happened in the past. As we see a flashback, we hear the voice of the character in the present. Perhaps the character is talking with another character, or writing a letter or diary entry.

In each of these conventions, the voice-over sound isn’t coming from the action onscreen. We don’t see a source in the scene, and typically we don’t see the external narrator speaking, or the character who is hosting the flashback. Moreover, the sound has a different timbre; it’s miked more closely and without ambient effects. Another cue that the voice is “over” rather than “in” the images is the choice of verb tense. In a flashback, a character narrator will use the past tense to describe the action we’re seeing, and usually an impersonal narrator will as well.

There’s another type of voice-over, though. Here the voice is not sensed as “over” the action but “in” it. The voice is representing a character’s thoughts at the moment. The cues for this are likewise pretty clear and redundant. Again the voice is closely miked. It accompanies a medium or close shot of a character, and the words are spoken by the character’s own voice. But the character’s lips aren’t moving.

We understand that the sound represents the thoughts in the character’s mind. Using the literary term, we can call this convention interior monologue. Unlike voice-over commentary, the interior monologue is marked by the present tense. The character will refer to himself or herself with the pronouns “I” or “you.” In the sense I mean, the character isn’t a narrator; the character’s thoughts are what is narrated, by the convention I’ve picked out.

Both conventions of voice-over are strongly associated with Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. Call Northside 777 (1948) opens with the external narration of a detached, documentary-style voice.

In the year 1871, the Great Fire nearly destroyed Chicago. But out of the ashes of that catastrophe rose a new Chicago. A city of brick and brawn, concrete and guts, with a short history of violence beating in its pulse.

The narrator goes on to describe a crime that took place in 1932.

The Fallen Sparrow (1943), by contrast, starts in a train compartment, with Kit McKitrick opening his suitcase, taking out his gun, and looking out the window. As the train goes into a tunnel, the windowpane becomes a mirror, as above.

Over this image we hear Kit’s inner monologue.

All right. Go on. Let’s have it. Can you go through with it? Have you got the guts for it? Or did they knock it out of you? Made you yellow?

The screenplay’s indications are as follows: “Kit stares at the reflection of his own eyes. Softly, barely audible over this, though Kit’s lips do not move:…” There follows a slightly longer version of the voice-over text.

The inner monologue is a venerable literary technique, used in novels for decades, and plays for centuries as the soliloquy and the aside. So you’d think that early American sound filmmakers would have adapted it quickly and without fuss. Actually, they don’t seem to have done so.

You can find auditory flashbacks (another device some would call voice-over). In City Streets (1931) while Nan stands by the bars of her cell we hear a fragment of an earlier conversation. To venture outside Hollywood, there’s the famous example from Hitchcock’s Blackmail (1929) in which the heroine seems to hear “Knife!” emerge from casual breakfast talk with increasing volume. Here, I’d suggest, we’re getting an impressionistic filtering and exaggeration of a word that’s repeated in the action of the scene. Both passages are subjective, but neither is an interior monologue. And both are rare examples in early sound cinema.

Hence the interest of Strange Interlude, which MGM made in the spring of 1932.

Thinking out loud (very)

It’s based on a 1928 play that won Eugene O’Neill his third Pulitzer Prize. Like many of O’Neill’s projects, the drama was massive and experimental. It consists of nine acts lasting five hours, with a dinner break after the fifth act. The production was surprisingly successful, running over a year on Broadway and touring to packed houses around the US.

The action seems fairly skimpy for such a long play. At the start, Nina Leeds is grieving over the wartime death of her beloved Gordon. An older friend of the family, Charles Marsden, is secretly in love with her. Nina plunges into nursing work at a veterans’ hospital, and a doctor there, Ned Darrell, is concerned about her careless promiscuity. Darrell himself is attracted to Nina but resists falling in love with her. Instead he suggests that she consider marrying Sam Evans, a bright but good-hearted college boy she’s seeing.

She does, but she learns from Sam’s mother that there is a strain of madness in the family, and if they have a child, the lunacy is likely to be passed along. The mother brazenly suggests that Nina find a new partner and pretend the love child is Sam’s. The target father becomes Dr. Ned, and of course he and Nina fall in love.

The sexy situation surely drew notice; there were censorship rows in some cities. In addition, the play’s undertones attracted an audience who was starting to hear about Freudian theory. The men are all displacements and substitutes for Gordon; Nina even names her son for her dead sweetheart. At the end, when Nina relaxes in Charlie’s arms, she confusedly calls him “Father,” which is all an up-to-date 1920s intellectual needed to hear.

The formal innovations of Strange Interlude stem from what some critics considered O’Neill’s urge to create a “novelistic” drama. This explains not only the play’s extreme length, but its span of over two decades. Years pass between acts. O’Neill sought, he claimed at the time, to trace the complete history of a woman’s life, in a way that would show facets of the “Eternal Woman”: innocence, passionate youth, early marriage, infidelity, motherhood, and eventual acceptance of old age.

Another facet of O’Neill’s “novelistic” ambitions was the expansion of the old-fashioned theatrical aside into a string of inner monologues. A character speaks his or her thoughts aloud, and while the other characters can’t hear them, we can. All the major characters are given at least one passage of inner monologue. A great many of these run very long, over a page in the play script, and they were largely responsible for the vast length of the show.

Like a novel, the play gives us omniscience, gaining access to several characters’ minds. The thematic thrust of the device was that we often think things that are the opposite of what we say. We wear “verbal masks.” The inner monologues tell us about the characters’ real thoughts, and these tumble together in contradictions and associations. Here’s a short example from the first scene, when Nina’s father complains to Charlie that Nina has become a brittle young thing.

PROFESSOR LEEDS (absent-mindedly). Yes.

(Arguing with himself.) Shall I tell him? …no…it might sound silly…but it’s terrible to be so alone in this…if Nina’s mother had lived…my wife…dead!…and for a time I actually felt released!…wife!…helpmate…now I need help!…no use!…she’s gone!…

This passage is tame compared to the fleeting feelings and contradictory attitudes that scamper through Nina’s monologues. The effect is to suggest characters whose surface politeness conceals both shameful secrets and volcanic feelings.

As you’d imagine, there were problem making these interludes work onstage. The solution hit upon was to have the silent characters freeze in place while the “thinking” character delivered the monologue and moved freely around the set. The difficulties were compounded when O’Neill packed a series of monologues close together; at some moments, characters’ monologues seem to reply to each other. The choreography of the first productions must have been something quite dazzling and may account for the play’s success with audiences.

On the track of monologue

Strange Interlude was one of several Broadway properties bought by Irving Thalberg and his story editor Samuel Marx. There were censorship constraints, so that Nina is no longer promiscuous and doesn’t abort her and Sam’s child. Still, in the film she does bear Ned’s child, and they mislead Sam into believing he’s the father. The plot is propelled by the lovers’ reunions at long intervals and their hesitation about revealing their secret to Sam, to Charlie, and to the grown-up Gordon. They rekindle their passion but decide not to run off or tell Sam the truth. If Nina is punished at the end, it’s because she’s never able to join Ned as his life partner.

Strange Interlude was one of several Broadway properties bought by Irving Thalberg and his story editor Samuel Marx. There were censorship constraints, so that Nina is no longer promiscuous and doesn’t abort her and Sam’s child. Still, in the film she does bear Ned’s child, and they mislead Sam into believing he’s the father. The plot is propelled by the lovers’ reunions at long intervals and their hesitation about revealing their secret to Sam, to Charlie, and to the grown-up Gordon. They rekindle their passion but decide not to run off or tell Sam the truth. If Nina is punished at the end, it’s because she’s never able to join Ned as his life partner.

The script cuts the action down to fit a 112-minute running time, largely by dropping or condensing monologues. Very long speeches in the play become two or three lines in the film. There remained the question of how to present the monologues on film. In the early talkie days, people weren’t certain what to do.

MGM publicized the menu of options being considered. Director Robert Z. Leonard largely rejected the play’s tactic, that of having the thinking character turn slightly to the audience and speak in a different tone of voice. For a time, the production team thought of using superimpositions. A ghostly double of one character would appear at the proper moment and utter the thoughts while the tangible character stayed silent. Alternatively, Leonard considered having the ghostly doubles entirely replace the actors during the monologues. Given the pace at which the monologues bounce around the scene, the superimpositions would have been throbbing in and out pretty often.

The solution was the one that’s obvious to us. We simply see the thinking character and hear his or her thoughts, more closely miked, while the actor’s lips don’t move. Why did Leonard and his colleagues even consider other options? Partly because rerecording was not yet established as reliable enough to allow inserting lines, some mere interjections, into the flow of the recorded dialogue.

In production, the problem was solved in a mind-boggling way. The film was shot twice. The first go-round recorded the entire text, dialogue and monologue, for each scene. The dialogue was timed to fractions of a second. Then the monologue portions were transferred to phonograph discs. Then the film was rehearsed and re-shot, with the discs used as playback guides for the actors’ pauses. And the playback was recorded on the set, with the dialogue.

When the film was finally cut, the cleanly recorded monologues from the first go-round were cut into the shots of the actors thinking. They were amplified and, I think, spruced up a little in mixing to yield a more intimate sound field. Often they’re whispered, or at least delivered in a subdued tone.

Today the technique looks fairly conventional, at least at any given moment. At the time it seems to have struck observers as a novelty. “It is a technique admirably suited to the audible screen,” remarked the New York Times critic, musing, “I wonder whether these spoken private thoughts will inspire another picture with them?” Variety mocked Strange Interlude as a critic’s picture, a natural for “discourses on academic analyses of the contemporary ‘art of the cinema.’”

Both opinions strike most of us as deeply wrong. Today Strange Interlude looks a misbegotten monster, opposed to nearly everything we would celebrate about Hollywood sound cinema. Just when films were starting to pick up the pace, this movie goes lugubrious. Perhaps in the theatre O’Neill’s monologues wrap the action in a rhetorical micro-dramas, but in the film they expose the plot as a relentless tango of bourgeois self-absorption. The monologues drain the film of curiosity, suspense, surprise, and affect. There is no mystery in it. Everything is said, every question answered in advance. It must be one of the most absolutely explicit films ever made.

Yet if we argue that poor works of art can have worthy historical influence, I’d submit Strange Interlude as Exhibit A. Its purpose was misguided, and it bungled achieving even that, but it threw up an important convention that would eventually enhance cinematic storytelling.

Keep it to yourself, and to us

As a novelty, the filmic inner monologue ran risks. The Los Angeles Times critic worried that the movie version could confuse people who hadn’t seen the play. The ballyhoo for the release talked it up as “the first to pioneer in a new field of the talkie; namely, the presentation on the screen of hidden thoughts as well as the regular spoken dialogue.”

To assist viewers with the convention, the film has a foreword implying that we won’t see lip movements.

In order for us fully to understand his characters, Eugene O’Neill allows them to express their thoughts aloud. As in life, these thoughts are quite different from the words that pass their lips.

The opening scene immediately reinforces the point. Charlie walks down the street, greeting a one-legged soldier. This reassures us by displaying normal dialogue.

Charlie comes to the camera and pauses at the gate, musing aloud, “This pleasant old town, dozing. What memories it brings back.”

Then we get the film’s first inner monologue. His voice clear, his mouth closed, Charlie eyeballs the camera in a confiding way no one else will in the film. “Queer things, thoughts. Our true selves! Spoken words are just a mask to disguise them.”

The device is bared. It has been sharply contrasted with external dialogue and spoken monologue, and the theme of hidden thoughts is blatantly announced. Soon enough, after embracing Nina, Charlie’s voice-over reminds us: “How she’d laugh if she could only read my thoughts.” In the film’s first moments, its unusual sound device is flagged with Hollywood’s customary redundancy.

Throughout the film, Charlie is the only character who will occasionally play to the camera, in an echo of the stage production. The gesture reflects his role as an ineffectual observer of the Nina-Sam-Darrell triangle. In the film’s first sequence, which corresponds to the play’s first act, Charlie is also a crucial force for exposition, getting the lion’s share of inner speeches. In earlier plans for the play, he was intended as a chorus or stage manager.

So the film introduces its narrational device very explicitly. But as a film it offers a chance to coordinate the dialogues more tightly than was possible on the stage. With one character speaking while the others freeze, there was an inevitable slackening of pace. The movie camera, however, can isolate the thinking character. We can’t see what the offscreen characters are doing, so often they more or less cease to exist during the monologues. Concentrating on one character, we forget the others.

Probably O’Neill intended the fragmentary quality of some of the monologues as an equivalent of the stream-of-consciousness technique that Joyce had brought to literature with Ulysses in 1922. But by linking voices in a fairly linear way, Strange Interlude achieves the effect of an older novel in the Balzac-Dickens-Tolstoy line. In these works the omniscient literary narration shifts among characters within a scene. The film firms up this sense of gliding from mind to mind by isolating characters in singles, cueing us to expect a monologue at any moment. Sometimes, however, the film dares to interweave its dialogues and monologues within a sustained shot. At one point an aside from Nina in a two-shot is echoed by one from Charlie; she passes the ball by lowering her eyes, while he lifts his head.

The interpolations become quite fast and precise, as you can see from this extract.

It seems to me that film uses the technique more judiciously than the play does. After Charlie’s ruminations have provided exposition, Nina and Ned, the furtive lovers, get most of the monologues. Occasionally the drama adds new characters, such as Sam’s mother and the little boy Gordon, who seems to intuit Nina’s guilty thoughts. The film stages some climaxes as a ping-pong game of monologues, often without the cushioning of dialogue bits.

Here the characters seem to be conducting telepathic conversations.

But enough about me

Today the inner-monologue technique in Strange Interlude seems at once familiar and peculiar. I think that’s because the convention, in both fiction and film, didn’t develop along the choral lines the play and film laid down.

Today novelists are advised to stick to only one point-of-view character per scene. A current manual warns: “If you simply jump from head to head as the mood strikes you, the voice becomes a fractured mess.” Manuals of O’Neill’s time gave the same advice. Critic Clayton Hamilton admitted that a viewpoint could shift from scene to scene or chapter to chapter (the so-called “limited omniscience” technique) but he stressed that within a scene, the author should stick to rendering only one character’s viewpoint.

This is what we have come to expect in mainstream cinema. Not only inner monologues but all channels of subjectively tinted information are usually slanted toward one character per scene. So a film might have several point-of-view characters in its overall running time (e.g., Psycho), but any given scene is likely to be anchored around one.

When inner monologue doesn’t do this, comedy can result. Cuddling on a sofa in Me and My Gal (1932), Danny and Helen discuss a picture he remembers as “Strange Innertube.”

Ten years later, in A Yank on the Burma Road, the same gimmick was yielding flat-footed comedy.

Perhaps because it seemed a bit silly, very few 1930s filmmakers seem to have picked up the inner monologue device for serious drama. When they did, the multi-voiced version seems more common. In The Life of Vergie Winters (1933), the main characters attend a political rally, and each one gets a bit of interiority.

Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town (1938) not only presented a commenting narrator in the form of a stage manager, but included a scene of a wedding ceremony that assembled thoughts issuing from the minister (played by the Stage Manager) and the bride’s mother. For the 1940 film version, other characters’ inner monologues were added.

Both Vergie Winters and the Our Town film also include moments focused on a single character’s inner monologue. Still, it’s remarkable how few films of the 1930s pick up on device at all. I speculate that storytellers became more comfortable with it as it became more common on radio late in the decade. The strategy was emphasized by Orson Welles and especially Arch Oboler. By 1939 Oboler was building entire plays out of what he called “stream of consciousness” technique. Soon the inner monologue as we know it started to be heard in talk-filled films like Angels over Broadway (1940) and noirish tales like The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940).

Perhaps it took radio to teach filmmakers the dramatic power of the inner monologue. It was certainly suited to many genres, from crime and suspense stories to melodrama and even comedies. Since it crystallized in the 1940s, the technique, while rare, has never really gone away. Ingenious filmmakers, from Resnais to Wong Kar-wai, have revived and revised it.

More generally, I suspect we should thank radio and the stage, including plays as ungainly as Strange Interlude, for urging filmmakers to try for more. These models pushed narration beyond the momentary shove and tug of character-in-a-situation and overlaid a speaking voice that undertook the task of remembrance, commentary, and confession. Novelistic cinema, of a certain kind, was launched.

A later entry will consider another convention launched by an MGM movie in 1932. But you have probably figured out what that is.

A big thank-you to Michele Hilmes and Shawn Vancour for helpful guidance in the literature of radio. I’ve also learned from Neil Verma’s Theatre of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama (University of Chicago Press, 2012). Thanks as well to Kat Spring and Luke Holmaas for suggestions on 1930s sound.

On the staging of the play, see Philip Moeller, “Drama Makes Regular Stops,” Los Angeles Times (17 March 1929), C14. O’Neill’s novelistic intentions are discussed in “Origin of Drama Traced,” Los Angeles Times (3 March 1929), C16-C17.

I mention Ulysses as an influence, but surely O’Neill read Virginia Woolf, Ford Madox Ford, and other modernists too. The idea of a split-vocalizing character was explored in earlier avant-garde drama. One precedent which O’Neill might have known is the “monodrama” of Nikolay Evreinov. Eisenstein points out the parallel in his memoirs (Beyond the Stars, BFI/ Seagull, 1995), 521. (Thanks to Yuri Tsivian for the lead.) Joseph Wood Krutch defends the play’s novelistic introspection in The Nation (15 February 1928), 192. In all, Strange Interlude strikes me as an amalgam of the older novelistic tradition with the emerging stream-of-consciousness technique. Some, probably including me, would call the play a piece of middlebrow modernism.

On the making of the film, see “Filming ‘Interlude,’” New York Times (13 March 1932), X6 and Edwin Schallert, “Mute Stars to Speak Words,” Los Angeles Times (9 March 1932), 7. Lea Jacobs points out that re-recording practice in Hollywood faced problems of exact timing. Not until 1935, with the advent of “push-pull” tracks and click sheets, could filmmakers control in postproduction the tight interweaving of sources that Strange Interlude created through playback in production. See her Film Rhythm after Sound: Technology, Music, and Performance, discussed in an earlier entry. On Thalberg’s strategy of buying Broadway hits, see Mark A. Vieira’s Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince (University of California Press, 2010), 161-198.

The New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall reflected on the inner-monologue technique in “At the First Night of a Worthy Film” (11 September 1932), X3 and “The Screen: Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Strange Interlude’ Is Engrossing and Compact in Film Form” (1 September 1932), 24. The ballyhoo mentioned comes from Sid Grauman, who claimed he was going to embed a print of the movie into a wall niche of his theatre as a permanent memorial. See “‘Interlude’ Print to Be Sealed in Theater,” Los Angeles Times (23 July 1932), A7. The Variety review comes from 6 September 1932, 15.

The inner monologue is one type of what we call in Film Art “internal diegetic sound.”

Loyal Marxians will recall Groucho’s address to the audience in Animal Crackers (1930): “Pardon me while I have a strange interlude.”

Arch Oboler employs “stream-of-consciousness” in some of his 14 Radio Plays (Random House, 1940); his glossary explains the device as “Thoughts in the mind of character; method of delivery should be quiet, semi-monotone, with far less coloring than ‘conscious’ speeches” (257). The definition would cover flashbacks, but clearly some of Oboler’s 1939 plays such as Baby and The Ugliest Man in the World use the inner monologue. The former is printed in 14 Radio Plays, and the script of latter is available here. Go here to listen to both.

It seems clear that critics’ demand that viewpoint be restricted for an individual scene, however much it may shift between scenes, stems from the influence of Henry James. James argued for the unity and power of a limited point of view, often conceived as “seeing” the action from a certain character’s “vantage point.” “There is no economy of treatment without an adopted, a related point of view,” he writes in the preface to The Wings of the Dove. “I understand no breaking up of the register, no sacrifice of the recording consistency, that doesn’t rather scatter and weaken.”

What Joseph Warren Beach called “the well-made novel” trend that followed James placed great emphasis on this economy. See Beach’s neglected but astute The Twentieth Century Novel: Studies in Technique (Appleton Century Crofts, 1932). My paraphrase of Clayton Hamilton comes from Materials and Methods of Fiction (Doubleday Page, 1917), 1228-129. The contemporary advice I quote is in Sandra Newman and Howard Mittelmark, How Not to Write a Novel (Penguin, 2008), 164.