Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

What-if movies: Forking paths in the drawing room

Dangerous Corner (1934).

DB here:

We habitually indulge in what-if thinking. What if you hadn’t gone to that particular school, met those specific friends, lived in that particular place? Your future would have been very different, in ways you sometimes speculate about. Here is Brian Eno explaining how he found his career:

As a result of going into a subway station and meeting Andy [Mackay], I joined Roxy Music, and as a result of that I have a career in music I wouldn’t have had otherwise. If I’d walked ten yards further on the platform or missed that train or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now.

We think this way on a small time-scale too. If you had left that damned parking lot a little earlier, you wouldn’t have had the fender-bender you had down the street.

Just as flashbacks exploit our common-sense intuitions about memory, other narrative strategies tap our habit of what-if thinking. Some movies evoke alternative but parallel fictional worlds. The most recent what-if movie I know is Edge of Tomorrow, whose tagline and video release title, Live Die Repeat, sums up its premise. I thought it was an ingenious use of the format, although the ending left me puzzled. Earlier on this site I wrote about a more intriguing example, Duncan Jones’s Source Code. Sometimes I call these “multiple-draft” plots because they keep revising the action until it comes out right.

Hong Sangsoo has explored the what-if possibility with unusual energy, but he’s less explicit about setting up the structure than Hollywood films are. With his movies, sometimes you don’t realize you’re in a parallel-world plot until you notice repetitions of action with tiny differences. (We have entries on Hong here and here and here.)

Some years back I wrote an essay, “Film Futures,” in which I analyzed the what-if, or “forking-path” narrative. That essay, revised for the book Poetics of Cinema, is now available on this site. It explores several examples: Kieślowski’s Blind Chance, Tykwer’s Run Lola Run, Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be Number One, and Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors.

One Hollywood experiment in this vein was a film version of J. B. Priestley’s 1932 play, Dangerous Corner. I mentioned the play in the essay, but I wasn’t then aware that a film version had been made by RKO in 1934. (To add an extra sting to my ego, it was sitting in our massive collection of RKO movies on campus.) I learned of it just recently when it aired on Turner Classic Movies, a national treasure I have celebrated before. The film quickly showed up online at Rarefilmm, and probably elsewhere.

In the essay, my approach was to treat these films as a sort of genre. What conventions rule them? What motivates the forking-path format—a science-fiction device such as a time machine, or fortunetelling, or something else? How do they tap our what-if thinking? Dangerous Corner lets me test my proposal on a new instance and offer a trailer for a new online essay.

As with any comprehensive narrative analysis, there are spoilers.

They have been here before

Darkness. We hear a gunshot and a woman’s scream. The stage lights come up and reveal some women in a drawing room listening to a radio play, “The Sleeping Dog.” Soon they’re joined by their male partners. An inadvertent remark by one of the women starts a cascade of confessions. The couples reveal a seething mass of illicit affairs, drug addiction, and repressed sexual desires.

As a result of the frenzy of truth-telling, the husband who set the process in motion lurches offstage and shoots himself. Darkness descends; a woman’s scream. When the lights come up, we are back in the drawing room. The broadcast play is at the same point as before. This time things go differently, and music from the radio fills the room as the couples enjoy a banal evening.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

In the course of evening number one, all sorts of naughtiness are revealed. Martin, much loved by all, is revealed to have been a thrill-seeking drug addict with whom Robert’s wife Freda has been having an affair. Olwen is secretly in love with Robert. Gordon’s wife Betty is Charles’s mistress. Gordon in turn is in love with Martin, and we’re to understand they’ve had an intermittent gay affair. Martin has died not by suicide but by accident, when Olwen was struggling to escape from his attempt to rape her. In all, the three publishers’ private lives would suffice for a steamy best-seller.

The point of Priestley’s play is that revealing the truth is a risky business, like driving around a dangerous corner. He uses the forking-path format to suggest the harm of revealing things best kept hidden. Hence the radio play’s title, a reference to letting sleeping dogs lie. For Priestley, however, the parallel-worlds conceit was more than an artistic device. He insisted that Dangerous Corner not be regarded as a dream play but rather “a What Might Have Been.” It proceeded from Priestley’s deep interest in time, which he saw as not merely the linear, “once-and-for-all” track of daily life.

Our real selves are the whole stretches of our lives, and . . . at any given moment during those lives we are merely taking a three-dimensional cross-section of a four-, or multi-dimensional reality.

The same interest in time as split or looped is seen in his 1937 plays Time and the Conways and I Have Been Here Before.

The film version of Dangerous Corner makes some important changes. As you’d expect for a film of the 1930s, the gay plotline and the drug addiction are excised. The character of Charles (Melvyn Douglas) is made more virtuous. He is revealed as the thief, as in the original, but here he has stolen the bonds to help Betty pay off gambling debts. She is no longer his mistress but a friend he is protecting. In addition, Charles is shown pursuing Ann (the play’s Olwen), who turns aside his proposals of marriage. At the end of the film, she agrees to marry him, providing a romantic wrapup.

The first seventeen minutes of the film establish the Charles-Ann courtship and present portions of the play’s backstory. We witness the three men discovering the theft of the bonds, and soon we watch Charles’ discovery of the dead Martin. An inquest declares the death a suicide, and a year passes. Now begins the play’s opening situation, with the women in the parlor. But there’s no longer a radio play running; instead, they’re listening to music before they hear a gunshot. That turns out to be the result of Robert’s firing his pistol into the garden to show it off to Gordon and Charles.

Coming into the drawing room, the men pair up with the woman and banter with their guest, the novelist Maude Mockridge. (She’s in the play as well.) The radio becomes important when Gordon goes to it to tune in some dance music, but the tube fails and, as he puts it, “I guess we’ll have to talk.” From then on the film follows the general contours of the play, and I think it exemplifies the conventions of forking-path plots pretty well. What are those conventions?

Using the correct fork

In the essay I start by suggesting that the action in forking-path plots is understood to be linear. Within each track, there is a smooth progression of cause and effect. Both play and film obey this condition through the simple chronology of scenes, but it’s also controlling the puzzle of the missing bonds, which is eventually explained by detective-story logic. Charles admits to taking them, and in the film Betty further explains that he did it to cover the gambling debts she wouldn’t confess to Gordon.

Linearity is also reinforced by a simple either-or switch. In the film’s tell-all version, Gordon can’t play dance music on the radio because there isn’t a spare tube for the radio set. Then begin the exposures of all the peccadilloes. In the alternate-reality version, there is a spare tube in the drawer, and so the exposures can be averted. Tube there: certain things follow. Tube not there: other things follow. Each chain of events proceeds without break or further splitting.

The radio tube is part of the film’s use of a second principle, what my essay calls signposting. If we’re to understand that there are alternative plotlines, we need some clear markings. In the film, we get several.

First there is the “reset” moment in the second version, when we return to the women moving to the French windows and hearing Robert’s firing of the pistol into the garden. That is a pure replay. What follows reiterates the action we saw earlier: The men joining the women, the radio announcing the time, and the initial chat before the signal fails and Gordon looks for—and this time, finds—a fresh radio tube. He thoughtfully reiterates the split for us. Dancing with Betty, Gordon says: “If Freda hadn’t had that spare radio tube, there wouldn’t have been any dance music, and then—well, anything might have happened.” As I suggest in the essay, characters in forking-path plots often get quite explicit about the what-if premise.

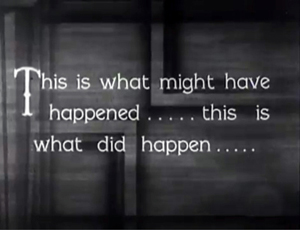

More unusual is the film’s use of intertitles as signposts. Robert, overcome with despair by the results of his relentless demand that everyone confess, runs to his room and shoots himself. The screen goes dark, with traces of smoke. Then we get this title:

At face value, this intertitle says that the stretch of time in which the characters exposed their private lives (the first “This”) is fictitious, while the amicable, truth-concealing version we’re about to see (the second “This”) is veridical.

Is this a bit of hand-holding for an audience that wasn’t prepared for the forking-path device? It does have that function, and to our taste it’s probably too explicit signposting. But it’s more interesting than it appears, because it reverses an intertitle that appears in the film’s opening.

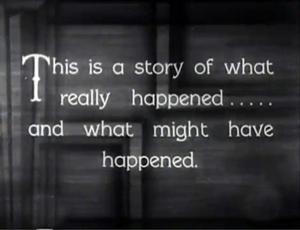

Before the action starts, we get this expository title.

Even without knowing how the film will develop, we are invited to imagine a two-part structure. After seeing the whole film, we can see that this puts the dual worlds on the same footing. The phrasing could be suggesting that the cascade of admissions we’ll see is what really happened, while the smooth social veneering of the final scenes was only an alternative possibility. At the climax, we’ll see the second title as a revision of this slightly puzzling one, which now might seem a bit of playful misleading.

But I think this first title is ambiguous in an intriguing way. The film really has three parts. First there are the 1933 events outside the drawing room, involving the robbery and Martin’s apparent suicide; these scenes aren’t in the play. Next block is the first, confessional versions of the 1934 evening. The third part is the alternative, calm version of the 1934 evening. From this angle, the first title is telling us that the 1933 section leading up to the crucial evening is “what really happened,” and that is indeed the case. We don’t get alternative versions of the robbery or Martin’s death. Accordingly, the sordid first iteration of the evening, the film’s second part, becomes “what might have happened.” In a weird way, the title is accurate about the first two chunks of the plot.

In other words, I’m suggesting that the titles fit the film’s structure as follows. The first title is in red, the second in green.

“This is a story of what really happened…”: The 1933 section.

“…and what might have happened.”/“This is what might have happened…”: First, scandalous version of 1934 evening events.

“…this is what did happen.”: Second, banal version of 1934 evening events.

Anyhow, two versions of the evening are quite enough for us. We can imagine more, but in films we never really encounter the radical plurality of multiple worlds. The physics of a true multiverse would offer indefinitely many variants, including ones in which any particular person doesn’t exist. In some worlds, Gordon would be married to Ann, Robert would court Betty, Charles would be a terrier, and so on. But—and here’s my third principle of such storytelling—the usual forking-path plot revisits essentially the same story world with the same characters, relationships, and settings, and most of the same actions. I call it the principle of intersection.

Intersection assures that we don’t get overwhelmed by having to meet a raft of new characters, figure out new settings or time periods, and generally reorient ourselves with each path we’re led down. Forking-path plots, from A Christmas Carol to It’s a Wonderful Life, keep things simple for us by changing very a few features of their rival worlds. Despite Priestley’s belief that each instant of our lives opens up many alternatives, that gigantic exfoliation of actions is very hard to dramatize and even harder for us to keep track of. So in both play and film, we have the same small world, with only a few differences. That works to the plot’s advantage, because those small differences—the radio works/ it doesn’t work, the cigarette box attracts attention/ it doesn’t—can be given enormous importance.

More rules

A fourth principle of forking-path plots involves the use of cohesion devices—elements of story or narration that smoothly link scenes. Cohesion devices are mid-sized examples of Hollywood’s love of continuity on every scale: cause and effect across the whole plot, foreshadowing of a later scene by an earlier one, hooks between sequences, and at the finest grain, shot-to-shot matching. Accordingly, each path in a forking plot ought to lead us along as easily as a normal plot would.

The essay mentions appointments and deadlines as common cohesion tactics. These aren’t very prominent in either the play or the film version of Dangerous Corner, chiefly because the forked action takes place in such a limited time span. But other devices, such as dissolves and fades, help the parts stick together. In the film a flashback dramatizes what Ann says took place on the night of Martin’s death in a way that fits tidily into the overall arc of the plot.

More interesting in the film are the parallels, a common byproduct of forking-path construction. At a macro-level, the two or three or however many paths are sensed as equivalent, variant versions that the viewer is invited to liken or contrast. And both our play and film reiterate the parallels among the couples; the visiting novelist Maude Mockridge says in the film that Charles and Ann should marry and complete the perfect symmetry set up by the “snug” pairings of the two other couples.

In the course of the first night’s exposures, hidden parallels are brought to light. Ann is mutely in love with Robert, who is mutely in love with Betty. Both the Freda-Robert marriage and the Gordon-Betty one are revealed as loveless. In the play, more parallels are piled on: Both Freda and Gordon have Martin for a lover, while Charles keeps Betty as his mistress.

Since parallels invite us to note contrasts, we can see that Phil Rosen (never accorded the status of an auteur) has somewhat altered things during the replay portion of the climax. Some variations in framing mark the second version as different from the first.

Mostly the purpose of the new angles in the replay is to highlight Charles and Ann, preparing us for their romantic alliance on the patio. The first version makes them small and far off-center left; the second emphasizes them much more, with the high angle enlarging and centering their flirtatious encounter.

My two last principles are also borne out in the film version of Dangerous Corner. One says that the last path traced presupposes the others. By that I mean it can take the earlier iterations as already read.

One result is that later versions of events can presented more briefly. When an alternative reality runs through bits we’ve already seen, we don’t need to see the full original version. This happens in the second fork of the film, which takes less than three minutes to get us to the crucial split—when Gordon discovers the fresh radio tube and tunes in the dance music. The first iteration of the evening’s events took almost five minutes to get us to the same point. This may seem a minor difference, but such intervals matter in a movie whose action consumes only sixty-two minutes on the screen.

Moreover, one time-saving passage shows the importance of the first iteration as setting up the situation. In the first version, Maude the novelist inquires about Martin, and she bends over a portrait photo of him.

This shot is less for her than for us, introducing the character whom we’ll see in Ann’s flashback. During the second version, we don’t get the full discussion between Maude and Freda, and we aren’t shown the photo. The narration assumes that after the flashback Martin is vivid enough in our memory. What replaces the insert of Martin is a reverse shot of Freda, describing Martin.

Now that we know she was Martin’s mistress, we’re in a position to appreciate how her dialogue and expressions conceal their relationship.

Similarly, the first version stresses the cigarette box that Ann inadvertently says she recognizes. The second version contents itself with a long shot, because now no one will question her about it.

The sense that the last path we see presumes the others has a more interesting side effect. Sometimes we get the sense that in the last go-round the character is mysteriously aware of the other paths she or he has taken. This happens in Sliding Doors and Run Lola Run, when each heroine seems to have learned from her experiences in the parallel worlds. And multiple-draft films like Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow make this learning process essential to the action. The premise is illogical, but narratives often violate logic.

Something similar happens in the film (but not the play) of Dangerous Corner. Alone with Charles on the patio, Ann accepts his marriage proposal because the cigarette box she saw at Martin’s, now in Freda’s hands, made her realize she’s “been a fool.” We have seen the flashback in which she fought off Martin and accidentally killed him. The flashback isn’t in the play, and it’s especially interesting because presumably that scene really did take place, in both paths. That is, the evening orgy of confessions is one hypothetical alternative, but the manner of Martin’s death a year before, revealed in this path, is an actual event. It’s as if reliving Martin’s attack during the first path has made Ann appreciate Charles’s genuine love for her.

My seventh principle also bears on the last path we encounter. It’s a simple one: We take the final path as the correct one. Since endings are typically the place where all is revealed, we’re prepared to accept the last reiteration as what really happened. (This can be reinforced by a character’s learning curve, such as Ann’s.) Dangerous Corner is a good example.

I think we’re urged, by the second intertitle but also by the overall arrangement of the parts, to see that the quiet maintenance of civility predominated during that evening. The more sordid alternative, though given at much greater length, is what’s under the surface but what will never be acknowledged. The truth of the theft and Martin’s death, along with all the love affairs and animosities spilled out in the first version, will never be brought to light.

Other factors give the second version more weight. There are the shots I mentioned that stress the Ann-Charles relationship more, but for me the clinchers are more structural than stylistic. For one thing, both Ann and Charles play the role of raisonneur–the character(s) who explains the action and articulates central themes of the piece. In both the first path and the second, Ann echoes Priestley’s notion of our limited knowledge, saying that we prefer half-truths to the complete, factual account, the one that only God knows. And in both paths Charles warns against telling the truth, as it presents a “dangerous corner” that could lead to a smash-up. No other characters reflect so fully on the consequences of letting everything out.

Another structural factor involves the film’s beginning and the ending. The 1933 section starts with a scene in which Charles calls on Ann and once more asks him to marry her. Thanks to the primacy effect, this pair of characters becomes more salient in what follows than the married couples do. As a result, the epilogue, set on a terrace like the first one, harks back to the indubitably actual, pre-fork opening.

The fact that the movie ends with the creation of a couple, the uniting of the two characters who are the most self-aware and sympathetic throughout the film, reinforces the sense that this is the “real” outcome.

I hope you’ll read the whole essay. My purpose is to understand the dynamics of a small but increasingly common body of films. Forking-path films ask us to construct stories in unusual ways, but we quickly learn what guidelines to follow. Once the format exists, filmmakers take up the challenge of mastering it, stretching it, applying it to new material. (Edge of Tomorrow was sometimes considered Groundhog Day Goes to War against Aliens.) As filmmaking practice develops, we can track contemporary experiments and relate them to earlier efforts they are based on.

In addition, it’s worth knowing that a fairly sophisticated filmic treatment of the format appeared eighty years ago. In the essay, I find even earlier examples. And in a period when every movie seems at least 130 minutes long, it’s nice to encounter one that offers so much narrative complexity in about half that running time.

More generally, I think that probing this body of film shows the value of systematically studying narrative formats of any type. We’re used to talking about genre as a fluctuating body of conventions, but we should also study conventions that cross genres—conventions of story worlds, plot structure, and narration. These conventions can prod us to execute some unusual mental moves. Filmmakers are practical psychologists, and they’ve learned how to tease and tickle our minds. What-if movies are just one example of how norms and forms guide our understanding of story.

My first quotation from Priestley comes from Three Plays and a Preface (Harper and Brothers, 1935), ix. The second comes from Two Time Plays (Heinemann, 1937), ix.

In production, Dangerous Corner seems initially to have replaced Priestley’s what-if premise with more of a whodunit plot, while incorporating subjective sequences. According to a Variety review of an 83-minute cut before release, the explanations offered for Martin’s death by the various men are followed by something fairly unusual.

Surprise and twist, with increasing suspense, are accomplished through a shift from the factual elements to subjective processes on the part of the three women most closely related–as wives or sweethearts–with the suspected men. An innocent revolver shot precipitates the terrific speculations as each woman wonders if her man has killed himself in an adjoining room (Daily Variety, 13 September 1934, p. 3).

By the final release, however, the film had lost twenty minutes, and the result was the version we have. I haven’t seen versions of the screenplay, but I bet they’d be interesting. We’re left with other what-if questions, this time about the production of the movie itself.

Some of the basic concepts I employ here and in “Film Futures” are explained in the essay “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” online here. That essay is in turn applied to The Wolf of Wall Street in this blog entry.

Dangerous Corner (1934).

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

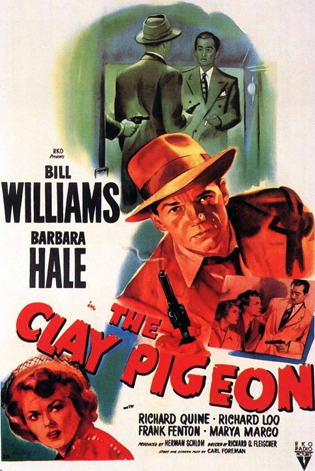

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).

Gone Grrrl

Gone Girl.

DB here:

How are contemporary movies, even this weekend’s releases, indebted to earlier traditions? Sometimes Kristin and I tackle this question. We’re not (I hope) trying to impress you as connoisseurs of esoteric knowledge. We’re definitely not trying to play down a movie’s originality by yawning and shrugging and murmuring “We’ve seen it all before.” Instead, as historians of film forms and styles, we’re interested in the ways that current movies reconfigure techniques that have been circulating across cinema history.

A lot of those techniques involve storytelling. So we’re obliged to study narrative conventions and innovations across the decades. And since cinema isn’t sealed off from other media, we’re curious about how films borrow narrative devices from other arts. The borrowing isn’t only one-way, of course; cinema has influenced storytelling in other media too.

Mystery and suspense stories have long attracted people who study narrative (“narratologists”) because such fictions depend almost completely on storytelling subterfuge. True, other genres can include false leads, or misleading ellipses, or questionable flashbacks, or strange point-of-view switches. But mystery-based plots require them in a way that science-fiction or romance plots don’t. In mystery stories, characters keep secrets from each other and the author must keep secrets from the audience as well.

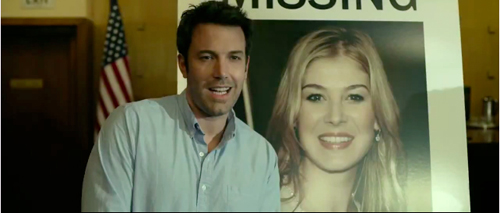

Which brings us to Gone Girl.

Detective stories and thrillers are one-off demos of narrative trickery, so studying them can teach us something about how we understand stories. We’ve made a stab at showing this elsewhere on this site (see our codicil). But now comes a flagrant instance of narrative manipulation that has set people talking ever since Gillian Flynn’s novel was published.

That novel and the film she wrote and David Fincher directed throw into relief how popular narratives revise devices from earlier traditions. As narratologists in training, we’re keen as well to understand how the film creates its particular effects. I can’t answer all such questions here, but I offer some thoughts on the film’s storytelling strategies, with notes on how those adapt earlier ones.

Of course beyond this point there are spoilers for Gone Girl. I also heedlessly spoil Leave Her to Heaven, both book and film.

Two plots for the price of one

The domestic thriller usually involves a couple living together—a husband and wife, or in modern times a pair of lovers. The conflict might center on them or on a third threatening figure. A very common option focuses the plot on either a murderous husband or a murderous wife.

Gone Girl, both novel and film, starts with a classic murderous husband situation. Amy disappears. She has made her husband Nick discontented and angry, and he has started an affair with one of his students, Andie. Thanks to a crucial ellipsis in showing the first day, what Nick has been doing during Amy’s disappearance is skipped over. When Amy vanishes, apparently leaving a pool of blood behind, Nick is the prime suspect.

If your plot centers on a murderous husband, you have a choice. You can let the audience in on his plans, as in Rage in Heaven (1941), Conflict (1945), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), and, much more recently, Safe Haven (2013). But Gone Girl doesn’t unequivocally show that Nick has killed Amy, or even plotted to kill her.

The second alternative for handling a murderous-husband situation is to keep it mysterious, chiefly by confining us to the wife’s range of knowledge. This ploy was made famous in Francis Iles’ novel Before the Fact (1932) and in Hitchcock’s adaptation Suspicion (1941). The premise is: I think my husband is trying to kill me. The 1940s crystallized this plot format in films like Secret Beyond the Door (1948) and Sleep, My Love (1948), and it survived for decades, in films from Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) to Side Effects (2013).

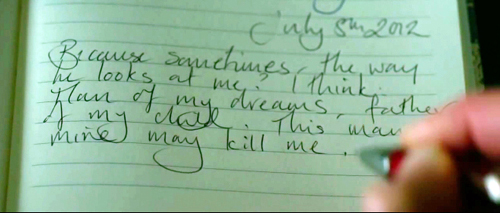

The first half of Gone Girl uses Amy’s diary entries to present the familiar arc of suspicion. The Dunnes’ marriage frays and she becomes increasingly frightened. Just before their fifth anniversary she buys a gun for self-defense. In her last entry she records her fear that he will kill her.

Nick looks pretty guilty at first, but with the whiff of doubt, another convention kicks in. That’s the one that film scholar Diane Waldman has called the “helper male.” If there’s another man nearby able to rescue the wife and play the role of a future romantic partner, then the husband is likely to be exposed as villainous. Examples are the Hollywood version of Gaslight (1944) and Sleep, My Love. If no helper is visible, then we’re likely to have a plot based on the wife’s misperception of the husband, as in Suspicion and Secret Beyond the Door. In Gone Girl’s first half, Amy seems to have no recourse to a helper male. This fact might dissolve some suspicion attached to Nick. Maybe, some viewers might ask, Amy was indeed abducted by a third party?

So much for the convention of the killer husband. A second type of domestic thriller, rarer than the first, centers on a homicidal woman. She shows up in the great Vera Caspary’s novel Bedelia (1945; made into a British feature in 1946) and in such films as Ivy (1947), A Woman’s Vengeance (1948), and Too Late for Tears (1949).

An especially shocking 1940s specimen of the killer wife is the cool, irresistible Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (novel 1944, film 1945). At first, Ellen wishes no harm to her husband Dick; she just wants to eliminate anybody with whom she’d have to share him. She lets his little brother drown, and, fearing that her unborn child will come between them, she flings herself downstairs and induces a miscarriage. Eventually, though, she turns her wrath on Dick. (Ellen’s most extreme tactic I’ll save for later, as it looks forward to Gone Girl.)

An especially shocking 1940s specimen of the killer wife is the cool, irresistible Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (novel 1944, film 1945). At first, Ellen wishes no harm to her husband Dick; she just wants to eliminate anybody with whom she’d have to share him. She lets his little brother drown, and, fearing that her unborn child will come between them, she flings herself downstairs and induces a miscarriage. Eventually, though, she turns her wrath on Dick. (Ellen’s most extreme tactic I’ll save for later, as it looks forward to Gone Girl.)

What is exceptionally clever about Gone Girl, again both novel and film, is that its second half replaces the murderous-husband schema with a revelation of Amy as a spider woman. Angry with Nick’s failure to sustain the role of the man she wants him to be, she has elaborately prepared an apparent murder that will lead police to suspect him. Here Flynn revives an old reliable of mystery plots, the faked death.

Amy has dovetailed three sets of clues for the police. There are clues she leaves in the treasure hunt, a little-girl game she obliges Nick to play every anniversary. This time, though, the hints point to uncomfortable aspects of their relationship. A second array of clues—imperfectly cleaned bloodstains, obviously faked signs of abduction, big credit-card purchases in his name—make Nick seem a lying killer. Then there is Amy’s faked diary, which she arranges to appear at just the moment that would harm him most. The diary entries initially coax us toward the Suspicion situation, seeming to provide a record of a wife’s growing apprehension of danger.

Knowing that a dead body will clinch the uxoricide case against Nick, Amy initially considers doing away with herself and letting the corpse be found in the river. Interestingly, this vindictive-suicide motif is the extreme tactic Ellen Berent pursues in Leave Her to Heaven. She poisons herself and sets up her sister Ruth, who’s in love with Dick, as her murderer. Like Amy, she has left a damning testament behind: a letter that will lead the police to arrest Ruth. Like Amy, Ellen has dropped a judicious trail of clues prepared well in advance.

So Flynn’s novel and screenplay shrewdly couple two thriller plot schemes, the murderous husband and the lethal wife. As an extra fillip, once Amy has been robbed by the desperate Jeff and Greta, she calls rich Desi Collings and convinces him of the threat Nick supposedly represents. In effect, Amy re-launches the lethal-husband scenario and recruits Desi as her helper male. Of course in most such plots, the helper male rescues the woman from peril. Here she is the peril.

Thank you, Mr. Griffith

So far I’ve talked mostly about what I called, in an earlier entry and in an online essay, the story world. But I couldn’t keep clear of two other dimensions of film narrative: plot structure and narration. I’ll talk about these more now.

I’ve indicated that Flynn’s novel breaks fairly neatly into two halves, splitting when Amy reveals that she hasn’t been kidnapped or killed. (“I’m so much happier now that I’m dead.”) The film, though, is a little less tidy.

As recidivist readers of this site know, Kristin has proposed that for decades Hollywood feature films have tended to break into several distinct parts that don’t fully correspond to the three acts of screenwriting manuals. The core structure for a normal feature involves four parts. Kristin labels these the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax, with a brief epilogue tacked on. They’re determined by turning points that alter the goals that the characters pursue, and they tend to run twenty-five to thirty minutes or so.

Kristin argues in Storytelling in the New Hollywood that short films can delete a middle chunk, and long films can iterate one. For instance, she finds that Amadeus has two Development sections. Picking up on this, I proposed in The Way Hollywood Tells It that The Godfather (a very long movie) has not only two Developments but two Complicating Actions.

The film version of Gone Girl offers an interesting extension of the basic pattern. The film runs 144 minutes without credits. I divide up the first 126 minutes according to major turning points.

Setup. After the prologue close-up of Amy, she goes missing and Nick begins to conceal things from the police (roughly the first half hour).

Complicating action, in which the main character conceives a new goal. Now that public opinion casts Nick as the killer and Andie becomes another secret he must conceal, he must try to convince all he’s innocent. He fails. Boney summarizes the case against him at about 60 minutes in. Then he discovers the luxury goods stuffed into his sister Margo’s shed and he realizes that he’s been set up.

Development, in which backstory is provided, the protagonist confronts more problems, and many delays are set up. As Amy drives away from town and assumes a new identity, her Cool Girl monologue confirms for us that she has framed Nick. She hides in the motor court and strikes up an uneasy friendship with Greta and Jeff. While Nick engages Tanner Bolt as attorney and learns of Amy’s earlier framing of O’Hara, Amy calls Desi Collings for help. Nick has agreed to go on Sharon Schieber’s show.

Once we learn that Amy has faked her diary and loaded it with lies, we follow her stratagems after the first day. Gradually her life on the road syncs up with the progress of Nick’s situation, so that via crosscutting they eventually watch the TV coverage simultaneously.

Development sections tend to run a little long, and this one needs a chunk of backing-and-filling to explain Amy’s scheme. This part ends, I think, around the 104-minute mark, when Andie at a press conference confesses her affair with Nick while Amy accepts sanctuary at Desi’s lake house. Now Nick must take the initiative and fight back, while Amy must concoct a new plan for her new circumstances.

Climax: Here a plot culminates in success or failure, goals definitely achieved or not. Nick does well in his Sharon Schieber interview, but almost immediately the police discover the loot in Margo’s shed and confront him with the diary. He’s arrested. It’s his darkest moment so far. Meanwhile, Amy has become Desi’s prisoner. But Nick’s TV performance has convinced her that he’s ready to resume playing her ideal man. Accordingly, with typically surgical preparation, she kills Desi and returns home, announcing her escape from sex slavery. She comes back at about the 126-minute mark.

Were this a normal film, things would end here, with the couple restored; we’d need only a gloating tag showing humiliated police. Amy’s revelation of her scheme at 65:00 would then become a neat midpoint. But the film has almost twenty more minutes to run.

Is this section a protracted epilogue? Some viewers seem to take it as such, and to find it draggy, but it’s structurally necessary. I think it’s fruitful to see Gone Girl as having two climaxes.

Two climaxes for the price of one

The double climax in Gone Girl, I think, occurs because the film has a tandem structure from the start. The first hour alternates scenes involving Nick’s search for Amy with brief flashbacks triggered by shots of Amy writing in her diary. The diary supplies what we initially take to be exposition about their meeting, falling in love, getting married, losing their jobs, and moving to Missouri. These past scenes are sandwiched in between present-time scenes of the inquiry into Amy’s disappearance. The Griffith of Intolerance, not to mention the Christopher Nolan of The Prestige, would enjoy the extent to which book and film rely on large-scale crosscutting between protagonist and antagonist.

The duplex story lines lead to two turning points, one assigned to each major character. At 65 minutes, Nick’s discovery of the fancy purchases in Go’s shed changes his goal: He now must prove that Amy has set him up. At the same juncture, the revelation that Amy is on the road sets up her new goal of escape—at first, she thinks, to suicide but then to a life free of Nick, who seems safely en route to the death house.

Given the dual line of action, we have a first climax that puts Nick in jail and shows Amy killing Desi, which ends her flight. Her return provides a first phase of resolution for the overall action: Back home, she spins a new narrative for the media, one in which she “fought her way back” to her husband.

But we don’t have full resolution. Nick still has the goal of proving that Amy faked her disappearance, and now he must also show that she murdered Desi in cold blood. In addition, his rage against his wife’s frame-up threatens to make him the homicidal husband she painted in her diary. Will he be driven to kill her, as he sometimes indicates he’d like to? Meanwhile, Amy’s goal of reunion isn’t fully achieved. She still must evade punishment (Boney the cop is suspicious) and she must also persuade Nick to back up her rigged story of his abusive and spendthrift ways.

So a second climax shows Amy thwarting Nick’s goals. She blocks his efforts to reveal the truth and won’t allow a divorce. She retained Nick’s stored semen when they were trying to conceive a child, and she has impregnated herself. She will keep his son from him if he tries to make trouble. Nick accepts her frame-up and the couple become, as he says in their final TV interview, “partners in crime.” If you assume that Nick is the film’s protagonist and Amy the antagonist, we have that rare mainstream movie in which the antagonist wins.

Some critics have called the book and the film Hitchcockian, and film geeks will notice the midpoint giveaway as similar to that in Vertigo. More generally, the complicit couple exemplifies the transfer-of-guilt dynamic we find in Shadow of a Doubt, Strangers on a Train, and other of the Master’s films.

But this last quality isn’t unique to Hitchcock, or Flynn-Fincher. In Leave Her to Heaven, Dick becomes an accomplice to Ellen’s act of drowning his brother. He keeps quiet for the sake of the child he thinks she is carrying. As a result, the novel gives us a passage that could come straight from Gone Girl, on the page or on the screen.

And she said in serene and level tones: “But you lied to protect me, so—we share the guilt. That binds us together. We can never escape that now.” After a moment she added: “So we must go on together, wearing a mask for the world, being honest only with ourselves.”

Look who’s talking, or not

In both film and novel, Gone Girl’s large-scale plot patterns—the wedged-in diary entries, the ABAB attachment to characters, the cross-stitched timelines—are enhanced by choices about narration. I take narration to be not only voice-over sound but the moment-by-moment flow of story information. That flow is regulated by cinematic techniques, orchestration of point of view, and kindred strategies.

Now we encounter some differences between film and literature as storytelling media. For instance, in the novel the parallel plotlines are rendered in first-person narration, alternating accounts from Nick and Amy. Amy’s fourteen diary entries are motivated as the sort of things one enters in a private journal, whereas Nick’s aren’t presented as him telling anyone his tale. When Amy’s diary is revealed as a hoax, she continues to recount events, and still in present tense, as if she couldn’t shake the habit. Nick, however, continues to tell us what happened in the past tense. This sort of difference is rather hard to achieve in film, unless you have two continual voice-over narrators. This option Flynn and Fincher decline, probably in the interests of clarity.

Both the alternation and the variation in tense have a long novelistic past. Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) switches between chapters in third-person narration in the present tense and chapters in first-person past. The device of alternating viewpoints was picked up in twentieth-century modernism (notably Faulkner’s books) and popular genres as well. A simple example is Philip MacDonald’s 1933 mystery, X v. Rex, which switches between first-person letters written by a serial killer to the police and third-person accounts of the efforts to track him/her down. Somewhat fancier is Anita Boutell’s Death Has a Past (1939), which takes a series of scenes transpiring across one week and sandwiches among them bits of a confession written by the killer afterward—“flashforwards,” in effect.

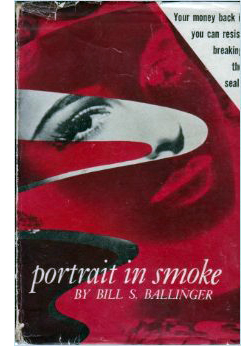

To go back to Leave Her to Heaven, Ben Ames Williams’ original novel alternates chapters filtered through the consciousness of husband, wife, brother, and sister, although all are treated in the third person. At about the same time, mystery writer Bill S. Ballinger gained notoriety for alternating chapters told from two characters’ viewpoints in two different time frames. Examples are Portrait in Smoke (1950) and The Tooth and the Nail (1955), the latter of which also toggles between first- and third-person discourse. More recently, in novels like Rebel Island (2007), Rick Riordan has intercut first- and third-person chapters.

To go back to Leave Her to Heaven, Ben Ames Williams’ original novel alternates chapters filtered through the consciousness of husband, wife, brother, and sister, although all are treated in the third person. At about the same time, mystery writer Bill S. Ballinger gained notoriety for alternating chapters told from two characters’ viewpoints in two different time frames. Examples are Portrait in Smoke (1950) and The Tooth and the Nail (1955), the latter of which also toggles between first- and third-person discourse. More recently, in novels like Rebel Island (2007), Rick Riordan has intercut first- and third-person chapters.

Journals and assembled documents have been one standard way that classic novels have been organized, and shrewd writers have exploited many possibilities. I think of the moment in The Woman in White (1860) in which a long and engrossing account written by a character in peril is revealed, only at the end, as being read by her adversary. More specifically, a major Flynn trick—the discovery that the diary mixes reliable accounts of events with false ones—has one major precedent. It occurs in a famous 1938 mystery novel that, for once, I will not spoil by naming. Here the diary in the first section is intended to be found by investigators and to cover up the identity of a killer.

This isn’t to call Flynn unoriginal; she has come up with a new variant of these narrational conventions. The point is simply that once you work in the realm of the mystery thriller, you will probably be seeking out ways to mislead the reader, and some of those stratagems will have a kinship with your predecessors. More generally, all narrative traditions exfoliate. Storytellers are constantly experimenting with new ways to engage us, and it would be surprising if two authors, both bent on achieving similar effects, didn’t occasionally hit on similar devices. Just as Flynn welded together two domestic-murder plot premises, she recast traditions of shifting, unreliable narration.

In the novel, the two first-person accounts, Nick’s and Amy’s, restrict our knowledge to each one’s perspective. Which isn’t to say that each is transparent. Nick will sometimes report his dialogue with the speech tag, “I lied.” This teases us to wonder what he’s holding back from the cops. Interestingly, confessing lies makes him a more reliable narrator, because he’s confiding in us. This has the effect of making us trust his claims about wanting children, not beating up Amy, and so on. By contrast, Amy’s chipper narration seems completely open about her feelings, but many of those entries are revealed as part of her murder masquerade. Her unreliability, though, seems chiefly confined to the diary entries; once she’s on her own, she seems to be reporting her sociopathic reactions sincerely.

Because the novel restricts us to the two main characters, we can’t know what’s happening outside their ken. Something similar happens to the attached viewpoints in Leave Her to Heaven, in which Dick and Ruth only gradually learn how his wife Ellen plotted to make her death seem to be murder. In adapting the novel to film, screenwriter Jo Swerling respected the novel’s systematic attachment to characters to a surprising extent.. First we are mostly with Dick, but at crucial points we’re given blocks of scenes organized around Ellen. Unlike the book, the film version shows us her executing her plan to implicate Dick and Ruth in her death. Here, for instance, Ellen puts arsenic in the sugar bowl that Ruth will use to sweeten Ellen’s coffee.

The film Gone Girl doesn’t give Nick a pervasive narrating voice as the book does, and we aren’t wholly restricted to his range of knowledge. On several occasions we watch the police making discoveries that he’s not aware of. Crucially, we see them find the diary some days before they tell him about it. As so often happens, mainstream film introduces some unrestricted narration, which yields suspense rather than surprise. Amy narrates the eight diary entries which introduce flashbacks, some of which turn out to be false ones. But once she finishes her Cool Girl monologue after the big turning point, we don’t, I think, hear her voice-over again.

Nick’s voice-over enters only twice, with carefully symmetrical effect. The film’s first shot is a close-up of Amy turning toward us as a hand strokes her head. Nick’s voice talks of wanting to split open her skull, unspool her brain, and find the answer to married folks’ perennial questions. “What are you thinking? What are you feeling? What have we done to each other?”

Most broadly the shot has the effect of rendering this beautiful woman mysterious. It also suggests a violent impulse in an uncaring, obtuse male—the sort of scenario that would lead to the murderous-husband plot that hovers over the film’s first hour. The final shot of Gone Girl repeats the close-up, and Nick asks his questions again but adds, “What will we do?” Now we know how devious that brain is, and how much justified anger the man speaking may be feeling toward her. Perhaps, after the movie ends, he will be ready to kill her. The two shots, unanchored in story time, bracket the movie with the central duality that the plot and the narration will enact: a potentially murderous man and an innocent-appearing but lethally dangerous woman.

There’s much more to be said about the film and the novel. I haven’t touched upon Flynn’s subject matter—what we might call Yuppies 2.0, the brain-entitled Net-enabled cool kids—and her theme of marriage as a struggle to play the role your partner cast you in. Issues like these have ingeniously set readers talking about marriage’s putative dark side and how men can feel “picked apart” by dazzling, demanding women. For my money, the presence of this brilliant, beautiful Crazy Lady, another legacy of the 1940s, favors Nick’s side of things. He’s a weasel but not as dangerously nuts as his wife. Your mileage may vary, for reasons I attribute to Hollywood’s perennial urge to cover every bet on the board.

We’d also want to consider the novel’s style, which offers caffeinated versions of Product Placement Realism and Vivid Writing, in both male and female registers. The screen version loses this aspect of the novel, and we get instead Fincher’s calm, polished direction. Too many shots of vehicles pulling up to buildings, I suppose; but if everybody laid out scenes as slickly as Fincher does we wouldn’t complain so much about our movies. I admired in particular the virtuoso sequence accompanying Amy’s Cool Girl monologue. Her eloquent rant runs underneath a crisp replay of her scheme and then supplies a montage of her trip and her change of identity, with glimpses of female types illustrating her diatribe. This passage is a good example of the crackling pace of the movie, which, thanks to smooth hooks and concise exposition, rushes along at just the speed of our comprehension.

Consider as well the economy of a single moment, when Greta and Jeff steal Amy’s money. At one level, the couple serves purely a plot function, one typical of a Development section: new problems, often overcome, serve to delay the climax. (Another plot construction would have had Amy simply lose her money and call Desi right off, shortening the movie by quite a bit.) The confrontation in the motel also serves a thematic function, contrasting Amy’s sheltered life with another social level she both detests and fears, as well as giving us another couple to compare with Amy and Nick. (Interestingly, in the Greta-Jeff pairing, it’s the woman controlling the man.) The moment I have in mind, the instant when Greta slams Amy’s face against the wall and says, “I don’t think you’ve really been hit before,” fulfills even more purposes. The whack (a) shows that Amy’s new identity is easier to see through than she thinks; (b) reminds us that her diary reports of being beaten by Nick are false; and (c) engenders a certain sympathy for her, invoking the classic woman-in-peril situation. This tight packing of implication and emotion into an instant is characteristic of classical studio storytelling. It exemplifies the unfussy efficiency celebrated by Otis Ferguson and Monroe Stahr.

My purpose here has simply been to indicate that we can usefully understand any plot as a composite of possibilities that surface in other plots. In a way, I’m revisiting ideas floated in my Shklovsky/Sondheim entry months ago. Again, this isn’t to put down Gone Girl as formulaic. Instead, it’s to suggest that any narrative we encounter in the mass-market cinema (and probably in other forms of filmmaking) is part of an ecosystem, a realm offering niches for many varieties—including hybrids.

Thanks to Kristin, David Koepp, and Jeff Smith for conversations about Gone Girl.

For comprehensive accounts of mystery and detective fiction, visit Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website. Relevant to today’s entry is my web essay, “Murder Culture,” and my entry comparing Safe Haven and Side Effects. Film Art: An Introduction includes a section on various forms of the thriller in Chapter 9. And don’t get me started on the relation between Gone Girl and one of my favorite domestic thrillers, Double Jeopardy.

The distinctions among story world, plot structure, and narration that I use here are explained in two other items: the chapter, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” in Poetics of Cinema, available on this site; and the analysis of The Wolf of Wall Street illustrating that argument.

Diane Waldman outlines the role of the helper male in her article “‘At last I can tell it to someone!’ Female Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23, 2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more on four-part plots, go to Kristin’s entry here and the essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” I’ve argued in another entry that popular novels can be built upon the four-part structure Kristin outlines, and it’s interesting to compare them with film versions that follow the same template. My examples were The Ghost Writer and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Fincher version). I think that Flynn’s novel is built on a five-part armature roughly comparable to that of the film. As for double-climax plots, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that In Cold Blood is another instance of this structure.

A more intricate use of diary narration in film is Nolan’s The Prestige, which derives from the even more intricate deployment of it in Christopher Priest’s original novel. We discuss the film in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction, and there’s a bit about the novel here.

Why so much emphasis on the cat in the film of Gone Girl? I suspect it’s at first a place-holder for the vanished Amy. Nick strokes the kitty as he strokes Amy’s head in the opening and closing shots. Seeing the cat tiptoe near broken glass (“You haven’t got a clue, have you?”) provokes Nick to solve the final clue in the treasure hunt. One shot, after Amy has returned, includes both wife and cat perkily welcoming Nick to breakfast. The cat is oddly matched eventually by the robot dog that Amy orders in Nick’s name. As a result, when Ellen Abbott gives Nick a robot cat, we have matching mechanical pets. Sort of like the human couple at the end.

Gone Girl.

Zip, zero, Zeitgeist

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014).

DB here:

The silly season always seems to catch me off guard. This time I got the word in a New York Times feature, “The Moviegoers.”

Here two writers, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, conduct an email conversation about recent films. You may have thought that the Times already has a large stable of movie reviewers, headlined by Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott. But mainstream movies are very accessible (as opposed to, say, serial music or Baroque architecture), so nearly everybody has something to say. And because nobody knows what counts as expertise in movie reviewing, why not bring on two of the commentariat? Once you become a public intellectual, what you say about anything is interesting.

Granted, both participants in the dialogue, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, have been movie reviewers. Mr. Bruni wrote for the Detroit Free Press, and Mr. Douthat currently covers film for the National Review. Through some process yet unexplained, these movie reviewers became second-string social and political pundits for the Times. That would seem a step up, so why put them back in the reviewing game?

The rationale is supplied in the series introduction, which talks of the plan to discuss “movies, pop culture, television, and other real-world distractions.” The Times style guardian might want to pause on the last phrase: Are these phenomena distractions in the real world (as in “real-world opportunities”)? Or are they distractions from the real world? I think the writer means the latter, which translates into this: Politics is the important stuff, mass art is a lightweight diversion. And we all need diversion, especially a newspaper aiming to attract readers under fifty.

So we have two Op-Ed columnists taking a break from serious matters in order to shoot the breeze about summer releases. In “Two Thumbs Up…Yer Arse.” Charlie Pierce, our fouler-mouthed Mencken, has exposed some curious assumptions about poverty displayed in the Moviegoers’ first round of chitchat. What interests me here is another aspect of the column, which showcases one standard move that many reviewers make.

The problem for serious people like Mr. Douthat and Mr. Bruni is this. If movies are “real-world distractions,” why spend any time talking about them? More specifically, why should political pundits talk about them? The obvious answer: Somehow these products of popular culture open a window into what’s really going on. Mr. Douthat:

In this sense I do think moviemakers are tapping into the American psyche, but I also think they’re replicating a flaw of the American political debate. I’m not sure we’ll get very far by painting the rich as morally hopeless people who must be subverted, vanquished, overtaken.

And when Mr. Bruni asks, “Tell me about the trend that made you happy, and (speaking of political allegories) whether you like ‘Apes’ as much as everyone else,” Mr. Douthat replies:

There was something poignant about watching “Apes” against the backdrop of the mess in the Middle East and of the war in Israel and Gaza, because it’s a disturbingly good allegory of reciprocal mistrust, asking the right questions about how peace ever reigns when combatants can’t bring themselves to forgive error, to take the first step, to turn from the past and focus on the future, to start afresh. It’s a disturbingly good allegory about corrupt leaders, too: how they whip up fervor in the service of their own ambition; how we rise and fall based on the clarity and wisdom with which we choose them.

You may want to reply that if this is what the Times wants, you will undertake to supply them with 3000 words of it every day at reasonable rates. But put aside the banalities about politics. I’m interested in the suggestion that movies can bear traces of the national psyche, or reflect national debates we’re having right now, or provide inadvertent “allegories” of contemporary history.

These ideas enjoy an astonishing popularity. They are staples of movie journalism. The trouble is that they don’t hold up.

Reflections on reflectionism

That mass entertainment somehow reflects its society is, I believe, the One Big Idea that every intellectual has about popular culture. The notion shapes the Sunday Times think piece about how the movies of the last few months capture the current Zeitgeist (or one a while back). It informs the belief that we can define periods in American popular art by presidential eras–Leave It to Beaver as cozy Eisenhower suburban fantasy, Forrest Gump as an expression of Clinton-era post-Cold-War isolationism. Reflectionism may be the last refuge of journalists writing to deadline, but it’s also found in the industry’s talk about itself. “Oscar Best Pic Contenders Reflect America’s Anxieties,” Variety announced last winter.

The threat of circularity. Behind this Big Idea is an assumption that cinema, being a “popular art,” tends to embody some state of mind common to the millions of people living in a society. The very idea of a massive mind-meld like this seems implausible. America’s anxieties and our national psyche? The anxieties of the 1% are not yours and mine, and I doubt that even you and I share a psyche.

The argument easily becomes circular. All popular films reflect society’s attitudes. How do we know what the attitudes are? Just look at the films! We need independent and pretty broadly based evidence to show that the attitudes exist, are very widespread, and have been incorporated in films. And it won’t do to simply point to the same attitudes surfacing in TV, pop songs, mass-market fiction as well, because that just postpones the problem of correlating the attitudes with groups of living and breathing people.

Critics seem to assume that if a film is successful at the box office, it must reflect the audience’s inner life. Yet the sheer fact of a movie’s popularity doesn’t prove that these attitudes are out there. Just because Spider-Man (2002) was a huge success doesn’t mean that it offers us access to America’s national mood or hidden anxieties. People spend time with a piece of mass art for many reasons: to kill an idle hour, to meet with friends, to find out what all the fuss is about. After the encounter, consumers often dislike the art work to some degree, or they remain indifferent to it. Since people must buy the movie ticket before they experience the movie, there can’t be a simple correlation between mass sales and mass mood. You and lots of others may be suckered into going to a film you dislike, but just by going you’ve already been counted as among those who support it. Doubtless many people enjoyed Spider-Man. But it’s very difficult to say how many.

And did all of the patrons who enjoyed it do so for the same reasons? That remains to be shown, and it’s hard. We know that a movie may appeal to several audiences at once, packaging a range of appeals. In fact, it’s a strategy of the film industry to produce movies that contain fuzzy messages, contrary attitudes, and something for nearly everybody. Must we find reflections of cultural needs in every aspect of a movie that might appeal to somebody?

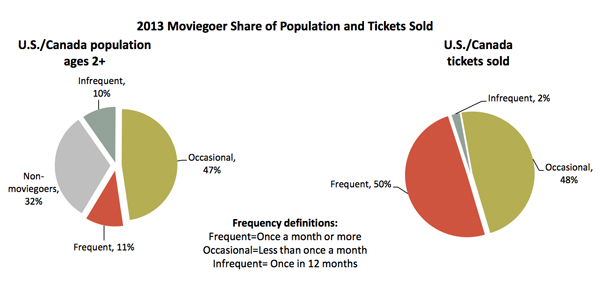

Movies are narrowcasting. The film audience is a skewed sampling of the population. According to industry statistics, about one-third of Americans over the age of two never go to the movies, and another ten percent go once a year.

Another 40% go “occasionally”–less than once a month. It turns out that the heavy moviegoers, those going once a month or more, are currently just 11% of the population. Take Dawn of Planet of the Apes. Assuming an average ticket price of $8 and no repeat viewings, at most about 25.5 million Americans and Canadians have seen the movie. That’s about 7% of the countries’ total population. We would need to tell a pretty full story about how the mental life of 350 or so million people gets into movies seen by a thin, self-selected slice of the population.

Moviegoers are atypical of the population in other respects. Since the beginning, Hollywood cinema has catered to the middle class. Moviegoers have been younger, better educated, and better-off economically than non-moviegoers.

The real mass medium of our time is network television (as radio was before). On one night, a single episode of The Big Bang Theory can attract 19 million viewers. A film that had that viewership across an opening weekend would take in over $150 million. That is $50 million more than the latest Transformers movie garnered at its debut. If Messrs. Douthat and Bruni want to take the national temperature, they should watch TV–ideally, the ads on the Super Bowl (shown to 112 million viewers).

Actually, you can argue that television really is a more reliable barometer of mass tastes, not just because of its prevalence but because TV viewing depends on recidivism. People may not know they’ll like a movie before they attend, but they tune in to shows that have proven to satisfy them. Still and all, mass taste is not the national psyche.

The long road from the White House. A primary prop for reflectionists is politics. Talk about an American film of the 1950s and sooner or later someone will invoke the reign of blandness that was (purportedly) the Eisenhower administration. But why do we assume that the population’s mind set switches its course whenever a new President is elected? Many voters stubbornly adhere to the same values election after election; others vote in order to throw out a rascal and aren’t at all satisfied with the newcomer.

There couldn’t be a direct tie between elections and moviegoers’ attitudes. About thirty percent of today’s audience consists of people too young to vote. The most reliable voter turnout is among the over-forty-five set, which until recently constituted only about twenty percent of moviegoers. Of course, maybe movies reflect the attitudes of non-voters, or people who are indifferent to politics. But then why identify periods of political history with periods of movie history?

Reflectionists have always been reluctant to offer a concrete causal account of how widely-held attitudes or anxieties within an audience could find their way into art works. What precise story could we tell to explain how changing the occupant of the White House can affect popular culture? How exactly does a party platform or a candidate’s charisma or the new administration’s policies seep into Hollywood movies for the multitudes?

Movies’ crystal ball. If there ever were a dominant mood at large in the land, it would be very difficult for that mood to find its way into a current movie. There’s often a lag of several years before a script gets to the screen. Many of the films released in 1997, though read as responding to current crises, were bought as projects in 1993 and 1994. Dawn of Planet of the Apes was begun in 2011, written through 2011-2012, and began shooting in April of 2013–all before the current standoff between Israel and Hamas.

Maybe the moviemakers are somehow in touch with political forces before they crystallize? One critic has proposed that films can have this prophetic power. Puzzled that no Obama-era movies had emerged by 2012, J. Hoberman suggests that the most “Obama-ite” ones came out before Obama was elected:

The longing for Obama (or an Obama) can be found in two prescient 2008 movies—WALL-E (the world saved by an endearing little dingbot, community organizer for an extinct community) and Milk (portrait of another creative community organizer—not to mention a precedent-shattering politician who, it’s very often reiterated, presented himself as a Messenger of Hope).

This is nearly a miracle. Somehow these filmmakers sensed that Americans (well, 53% of the people voting) were yearning to be led by a community organizer. But how specifically could the filmmakers have arrived at that prescience? In fact, they would have had to be long-range prophets. Milk began as a 1992 project, and the final version of the script was prepared in 2007. The Pixar adepts started talking about WALL-E in 1994 and began drafting scripts in 2002. Why don’t we ask filmmakers to predict our next president right now?

Pick and choose. Of all the films of the summer, Bruni and Douthat settle on a few. Of all the hundreds of 2008 films, two presage Obama. This selectivity is typical of the reflectionist approach, which typically ignores the range of incompatible material on offer.