Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks

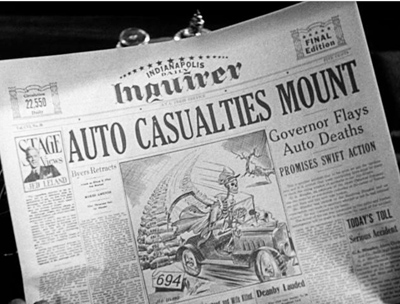

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Trigger warning: This blog is about Quentin Tarantino, Walt Disney, and Henry James. Those who find violent analogies disturbing should avoid what follows.

DB here:

Every narrative film is made out of parts. Normally they just whisk by us, but sometimes our attention is called to them as parts. Occasionally, we sense that the whole movie is made out of large-scale chunks.

Take Pulp Fiction (1994). It consists of scenes grouped into larger blocks, some marked by fade-ins and outs and others with titles, like chapters in a book. The diner opening is set off as a unit before the credits. The ensuing visit of Jules and Vincent to the apartment of the welshing punks is ended in a fade-out. We then get a section tagged “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife.” After that portion fades out, there follows a sequence introducing the young Butch as a boy, presented with his father’s gold watch. Then Butch, now grown up, heads out to the boxing match. Another fade, and we get a title, “The Gold Watch.”

That could be seen as simply a belated chapter head for the entire Butch section, boyhood and prizefighting career. Or it could mark the start of another, much longer block: the aftermath of the fight and Butch’s flight from Marcellus Wallace. Either way, the sense of a film composed of large-scale parts is very strong. As the film goes along, we realize that each block tends to concentrate on certain characters and provide distinct, sometimes overlapping, stretches of time.

For many viewers, I suspect, Pulp Fiction was their introduction to strategies of block construction in movies. Those of us studying film history had seen it in various guises before, but seldom so cleverly and explicitly worked out as in Tarantino’s film. And I’m not sure even film historians realized how much Tarantino owed to earlier traditions.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I suggested that some of the experimental trends in 1990s-2000s cinema were indebted to Hollywood in the 1940s. This is especially evident in the neo-noir films of those years, like The Underneath (1995), The Usual Suspects (1995), and Memento (2001). Now that I’m writing a book on that earlier period, I realize that studying the 1990s films, has led me to think about something that I hadn’t noticed—how interested 1940s filmmakers were in building movies out of blocks.

Turns out that the 1940s was a kind of golden age of block construction. And Tarantino serves especially well to illustrate how that strategy can be put to use in modern times. In fact, his work is a fairly comprehensive layout of the creative possibilities of the format.

Building blocks

Some basic options for block construction were laid out fairly early in the silent era. The most famous instance was Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), which sampled four historical periods, each harboring its own distinct story. He then crosscut the four epochs, building to four “simultaneous” climaxes at the end of the film. Griffith managed to secure an unprecedented level of suspense by alternating portions of his blocks.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

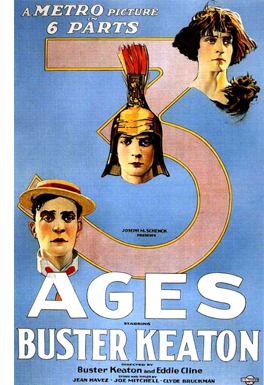

Directors who wanted to achieve the same comparison among different historical periods took the more obvious option and laid each separate story out, one after the other. We see the result in Dreyer’s Leaves from Satan’s Book (1920), Lang’s Der müde Tod (Destiny, 1921), and The Three Ages (1923), Buster Keaton’s parody of Intolerance. So this construction by integral blocks of time, laid end to end, was useful for comparing several self-contained stories.

Can you get the same sort of effect when sections of the same story are separated out in blocks? Yes, you can. The classic example would be parallel flashbacks. In Citizen Kane, an ongoing present, the reporter Thompson’s investigation, brackets long flashbacks that serve as parallel architectural parts—trips to the past, showing Kane as seen by others. We’re coaxed to compare Kane’s actions at different points in his life, as well as the various sides of him seen by his associates.

Here, as sometimes happens, the blocks are marked off not only by time period but by varying viewpoints. The alternation between the present and long stretches of the past, focused around one character and then another, characterizes many 1940s flashback films, such as The Killers (1947) and A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

Tarantino made alternating block construction the basic principle behind Reservoir Dogs (1992), which shuttles between the aftermath of a botched robbery and the planning that led up to it. One model he has acknowledged is Kubrick’s The Killing (1955), which itself transposed into cinema the overlapping point-of-view blocks that were present in Lionel White’s source novel Clean Break.

Elsewhere on the blog I’ve talked about how flashbacks can be nested inside one another, like Russian dolls. Examples from the 1940s include Passage to Marseille (1944) and The Locket (1946), and these lengthy sections surely count as blocks. Here the blocks serve less to compare dramatic situations than to fill in backstory. The blocks are lumps of exposition. In addition, blocks also can usefully delay events, creating suspense and padding the plot to its proper length. (Form often follows format.)

Tarantino embedded flashbacks within flashbacks in Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) for just these purposes. Let’s assume that the early sequence (Chapter One) showing the Bride attacking and killing Vernita, her second victim, is a benchmark for the narrative present. That ends with her reading her list of targets. Chapter Two, which follows, initiates a flashback going back several years. In the course of that, the Bride escapes from the hospital and sets out to kill O-Ren, who’s her first victim. And in the course of that long flashback, framed by the Bride lying in the Pussy Mobile, we get a nested one, dubbed “Chapter Three: The Origin of O-Ren.” That eight-minute anime fills in the life story of the queen of the Tokyo underworld before we return to the Bride’s quest for her.

The anime sequence is closed off by a return to the Bride recovering in the Pussy Mobile.

The flashback-within-a-flashback supplies exposition, creates a parallel to what we’ve seen at the film’s start (Vernita’s little daughter discovering the Bride’s murder of her mother), and sharpens our curiosity about the Bride’s trip to Japan. We stay in that Japan-related flashback for the rest of Vol. 1. The plot won’t take us back to the present, after the Bride’s killing of Vernita, until the black-and-white beginning of Vol. 2.

A trickier Chinese-boxes structure appears in Reservoir Dogs. The present-time situation is the gathering of the surviving hoods in the warehouse. There are flashbacks to the planning stages of the holdup, each attached to one man’s viewpoint and tagged with his alias.

In the flashback attributed to Mr. Orange, the police mole, we start with him identifying himself to the tortured cop in the warehouse. We move to the past, when Mr. Orange meets a contact in a diner and explains that the gang took him in. That leads to a nested flashback showing him at his audition.

To gain the gang’s trust, Mr. Orange tells a heavily rehearsed fake anecdote about evading the cops during a drug swap. And even that gets an embedding: the false anecdote is presented visually, as a scene in a men’s toilet.

Then we come out of the nested flashbacks in proper order: back to the meeting with the gang, then to the diner, and several scenes later, back to the present situation in the warehouse.

A lying flashback is embedded in a flashback that’s itself embedded within a flashback. The whole shebang becomes a complex block labeled “Mr. Orange.”

Most flashback films use the trips to the past to revisit characters known to us in the present. But some films use the flashback option to tell independent stories. Forever and a Day (1943) is a biography of a house, supplying a history of the house from its origins to its sufferings during the Nazi bombing of London. An even clearer example is Tales of Manhattan (1943). It traces how a coat of tails is passed down the social pecking order, from an elegant actor to a sharecropping community. No characters tie the episodes together, only the coat and some thematic motifs. Again, the blocks encourage us to contrast how different social classes use the tailcoat.

I don’t find Tarantino picking up this circulating-object idea, but it has been reused in Twenty Bucks (1993), American Gun (2006), and other films. Somewhat in the same spirit, though, is Tarantino’s Death Proof, the second feature in Grindhouse (2007). The first half of the original theatrical release concerns four young women who are targeted by Stuntman Mike, a free-range master of vehicular homicide. All the women are killed, but in the second half Mike meets his match in a quartet of car-crazy film staffers, one of whom is a stuntwoman while another is an expert driver. Mike is like the coat of tails in Tales of Manhattan: the only link between the film’s episodes.

Flashbacks can, of course, be much briefer, and when they are they don’t usually have the heft of blocks. But when a scene is replayed as a flashback, both the replay and the original scene can stand out. The flashback replay of the murder of Monty in Mildred Pierce (1945) gains a certain solidity, since it reveals things that were suppressed (and fudged) in the first go-round. (Go here for the entry and the analytical video discussing these scenes.) Another example is the conflicting testimony that includes a lying flashback in Crossfire (1947).

Pushing beyond his predecessors, Tarantino tries a more elaborate replay in Jackie Brown (1997). He presents the shopping-mall money exchange three times, from different characters’ attached viewpoints. The side-by-side replays make the whole money drop stand out as a block, as does the chapter title (“Money Exchange: For Real This Time”) and the length (over twenty minutes). A practice session for the exchange forms a parallel block, with its own introductory title (“Money Exchange: Trial Run”).

Episodic memories

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

If flashbacks, played once or many times, provide the most common sorts of blocks, big or small, there are other possibilities. You can, for instance, build your plot out of chronological but independent blocks within the same locale and time frame. Three Strangers (1946) is a straightforward example.

A woman invites two men into her apartment and suggests they share the price of a sweepstakes ticket. They will then reunite on the day the ticket falls due to see if they’ve won. After the men agree, the plot follows all three separately, with long blocks devoted to each. Their stories don’t intersect. There is a little bit of crosscutting among them, but the characters don’t reunite until the climax.

The advantage of this diverging-reconverging construction is that you can tell several stories, each with its own dramatic arc, within a larger frame that brings them all to a decisive conclusion. If you pull it off, it can deepen characterization (we spend more time with the protagonists) and perhaps mark you as a virtuoso. A flashy example is Mystery Train (1989), which provides the moment of the story lines’ convergence as a sound rather than a face-to-face encounter.

The risk of this format is that some separate stories may seem less interesting than the others. An ordinary film moves along quickly enough that we can wait out tiresome characters or situations, but in this construction we’re stuck for a while. This cost-benefit analysis may be one reason that most Hollywood plots try to integrate their story lines fairly tightly. That way you can keep the audience aware that each scene has consequences for everything that follows.

Tarantino uses the parallel block device in Inglourious Basterds (2009). Here two main story strands—Shosanna’s efforts to elude Colonel Landa and the mission of Aldo Raine’s combat team—develop independently in lengthy scenes. There’s some alternation, but the plot lines don’t converge until the movie theatre conflagration. Interestingly, both Three Strangers and Inglourious Basterds fill out their dimensions by including minor subplots (the adventure of Archie Hicox developing its own interest in Basterds).

The simplest version of block construction lets one distinct story episode follow another. The most common case is the Hollywood musical, which contains numbers, either as stage performances or as sung-and-danced scenes. Each number tends to have an internal coherence and sharp boundaries that make it a detachable unit. (So detachable that it can stand on its own in documentaries like That’s Entertainment! of 1974 and its sequels.)

One musical that includes larger-scale segments—quite big blocks,, actually–is Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). The plot consumes about a year in the life of a family, and it opens with a candy-box title card specifying “Summer 1903.” It’s followed by two more seasonal chapters, identifying autumn and winter of the year, before we get “Spring”—a title with no date, suggesting a kind of eternal renewal that will solve the characters’ problems. Within each of these blocks, events typical of each season, including Halloween and Christmas, reinforce the sense of these as varied sections.

This sort of explicit chaptering in the 1930s-1940s is usually reserved for films framed by opening pages of a book, as in Salome, Where She Danced (1945).

Often, as in Salome, the book frame is dropped from the rest of the movie, although it might reappear to provide closure.

New forms of self-conscious chaptering became prominent in later years, as with the quotations announcing sections in Hannah and Her Sisters (1985). Most of Tarantino’s films use chapter titles to some extent, with the Kill Bill movies providing the most elaborate examples. Those films are presented as two “volumes” containing ten distinct “chapters.” Some are bulked out by flashbacks, some aren’t, but all these chapters become prominent through sheer length. Chapter Nine, which settles the fates of both Budd and Elle Driver, runs almost half an hour, and the final chapter lasts over forty minutes.

Moreover, the chapters, as in Pulp Fiction, aren’t arranged in 1-2-3 order, so we’re invited not only to compare parts but figure out their chronology. The very first chapter teases us with this problem.

The circled 2 is explained when we understand that Vernita is the second target on the Bride’s list.

Still other forms of big-chunk construction came into prominence in the 1940s. Think for instance of what were called “episodic” films, movies that inserted separate stories, often thematically connected, into a general framing structure. For example, the team that gave us Tales of Manhattan also produced Flesh and Fantasy (1943). The situation is of two men discussing superstition in a library. One takes down a book of stories and we see, enacted, three tales of the fantastic. At the end we return to the library.

This cinematic anthology was sometimes called an omnibus film, and it proved very popular around the world; examples are Dead of Night (UK, 1945) and the many Italian and French collections (e.g., The Seven Deadly Sins, 1952; Spirits of the Dead, 1968). It persisted for decades in the US (New York Stories, 1989; Night on Earth, 1992) and internationally (Paris, je t’aime, 2006). Tarantino’s contribution to the genre was Four Rooms (1995). The framing situation is that of a hotel, and three other directors contributed episodes showing what happens to various guests.

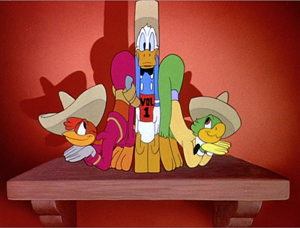

Walt Disney exploited block construction in all these ways during the 1940s. He filled out a live-action film with embedded stories (Song of the South, 1946) and interspersed cartoons with travelogue footage (Saludos Amigos, 1942). The all-animated Three Caballeros (1944; above) assembled several South American tales by means of a frame story showing Donald Duck getting gifts from below the border and dancing with his amigos. (This is a brilliant movie, as I suggest in this ancient but ageless post.)

By contrast, Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948) give their animated musical numbers only minimal framing.

Most famous of the Disney anthologies, of course, is Fantasia (1941). Here a program of classical pieces is illustrated in cartoon sequences. The frame is provided by Leopold Stokowski at the podium and Deems Taylor, a famous music popularizer, supplying radio-style commentary in the breaks. Strange though it sounds, Tarantino (along with Robert Rodriguez) does something similar when he gives us two exploitation features, Planet Terror and Death Proof, surrounded by trailers and ads. Just as Disney posits a mock trip to the concert hall, Tarantino reimagines a night at a drive-in or an inner-city movie house.

What about Django Unchained (2012)? I think Tarantino has done something clever here. At what seems to be the climax, Dr. Schultz is killed and Django, after a fierce gunfight, is recaptured and sold to slave traders. The drama seems to be finished. But then the movie starts over, and a twenty-five-minute stretch of new action shows Django escaping the traders and returning to Candyland to wreak his revenge. Tarantino has tacked on a second, lengthy ending; block structure yields a calculated anticlimax.

Modern, middlebrow, mysterious

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

Quentin Tarantino, 1993

Where did the 1940s impulse toward block construction come from? In classical Hollywood cinema, I see two primary literary sources: modernism and its offshoots in “mild modernism” (what Dwight Macdonald called “midcult”); and mystery fiction.

Fictional tales had long been broken into segments, and chapter divisions are of course very old. Assembling tales out of blocks likewise has antecedents as far back as ancient Egypt, Homer, and the Bible. Epistolary and found-manuscript fiction gravitated naturally to block arrangement. Dickens gave Little Dorrit (1855-1857) a balanced two-part layout, and he built Bleak House (1852-1853) on alternating segments in two narrative voices.

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

There was the ‘fun’ . . . [of treating the actions as] sufficiently solid blocks of wrought material, squared to the sharp edge, as to have weight and mass and carrying power; to make for construction, that is, to conduce to effect and to provide for beauty.

Likewise, The Awkward Age (1899) was conceived as a situation to be illuminated by different characters, or “lamps,” each participating in a single social occasion. Consequently the contents as a series of chapters (or “books”) with character titles (not unlike what Tarantino did in Reservoir Dogs): “Lady Julia,” “Little Aggie,” “Mr. Longdon,” and so on.

This sort of explicit geometry was sometimes taken up by modernist writers. Faulkner breaks The Sound and the Fury (1929) into large parts determined by place, time, and character narrators. John Dos Passos intercuts chunks of different sorts of texts (news stories, “camera-eye” views) to create the trilogy USA (1930-1036). Other modernists avoided tagging sections but made sure to give each one a blocklike singularity, as Joyce famously does with the chapters of Ulysses. Each one is keyed to a section of Homer’s Odyssey, a time of day, a symbol, and so on, and treated in a different literary technique.

Middlebrow writers, who tried to make modernism more user-friendly, seized on block construction. A prime example is Thornton Wilder’s Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), which traces three parallel stories of people who died on the bridge when it collapsed. Less famous is Rex Stout’s fascinating How Like a God (1929), which alternates two sorts of blocks: one in italics, past tense, third-person narration, and labeled with letters of the alphabet; a second in roman type, present tense, second person (“You…”), and given a numerical order. The labels and fonts help us figure out the chronology of the story (and grasp the thoughts of the main character). Kenneth Fearing’s mildly modernist novel The Hospital (1938) borrowed from Dos Passos in shifting viewpoints among many characters, even objects, and his Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) anticipates Pulp Fiction in drastically shuffling discrete blocks out of story order.

At a more popular level, mystery fiction developed its own strategies for block construction. As a genre, mystery and detective stories are dedicated to formal play with narrative options. (Hence their interest for us narratologists.) Mysteries are frankly artificial, even gamelike, and so seek out ways to trick us.

The love of artifice often yields embedded stories, as in A Study in Scarlet (1887), and plays with point of view (famously, Christie’s Murder of Roger Ackroyd, 1926). While Dickens and James were testing block construction in the “serious” novel, Wilkie Collins was developing the “casebook” format: a collection of documents—letters, testimony, discovered manuscripts—that served as a series of blocks. Dracula (1897) also helped popularize the format. It was revived in Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace’s The Documents in the Case (1930) and Perceval Wilde’s Design for Murder (1941). And just as Stout had made typography and chapter headings formal devices, so did mystery writers use them to build suspense and their readers (e.g., Anita Boutell, Death Has a Past, 1939).

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

Trends in high, middlebrow, and “low” literature like crime stories had a large impact on 1940s cinema. Just as important, this formal play with narrative conventions, including block construction, continued for decades, right up to the present. Most pertinent to Tarantino is the trend toward rigorous construction we find in crime fiction from the 1960s onward.

My own favorite example is Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake), who conceives nearly all his novels in a rigid four-part format. Tarantino seems to prefer Elmore Leonard and Charles Willeford. He isn’t given as much credit for his bibliophilia as his cinephilia, but it’s evident that he has thought a fair amount about how to bring literary techniques into cinema.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action.

For example, in Rum Punch, the source novel for Jackie Brown, Leonard’s chapter-breaks usually shift our attachment from one character to another, and the new chapter may insert backstory at the start. Leaving Jackie Brown’s deal with the Feds hanging, Chapter 14 starts with Melanie sunbathing and thinking about her past. A chunk of exposition, like a film flashback, explains how she became “the tan blond California girl.” Tarantino was unusually sensitive to fiction writers’ switches in time and viewpoint, and he clearly admired the opportunities opened up by solid chapter-length blocks.

I’m not suggesting that Tarantino spends his weekends perusing Henry James or Thornton Wilder. It’s just that techniques similar to theirs have pervaded popular literature. Indeed, they were already at play in one popular genre that has always used literary artifice to shape our experience. To this day, as in King’s 11/22/63, mysteries and thrillers use block construction to promote suspense, play with alternative possibilities, make us reevaluate story situations, and engage us in a game of self-conscious form.

Sometimes current developments put the past in a new perspective. The emergence of “minimal music” (Glass, Reich, La Monte Young) suddenly showed Satie’s ideas about repetition to be more fertile than most of us had thought. Similarly, Tarantino’s work forced me to think about contemporary storytelling strategies, but it also asked me to consider more distant sources of those trends.

Studying film history is valuable for its own sake; it’s just damn interesting. Needing further justification, sometimes historians go on to say, especially to students: We study history to better understand the present. That’s surely true, but so is this: We study the present to better understand history.

Henry James’ discussion of block construction is in “Preface to The Wings of the Dove” in The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces (New York: Scribners, 1934), 296. Tarantino’s comments about novels and films come from Graham Fuller, “Answers First, Questions Later,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 53; Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (Applause, 1995), 69.

A useful discussion of how chapter divisions relate to plot is Philip Stevick, “The Theory of Fictional Chapters,” in The Theory of the Novel, ed. Stevick (The Free Press, 1967), 171-184. You can sample it here.

Neo-noir encouraged many filmmakers to explore block construction. Three quick examples: Soderbergh in Out of Sight (1998; from a Leonard book), Christopher Nolan in Following (1998), and Shane Black in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005, which split up into chapters corresponding to one popular screenplay formula). Nolan proved keenly interested in this compositional approach; see our ebook, Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. More recently, Wes Anderson’s films deploy some tricky versions of block construction.

Block construction is also apparent in comic books, and Tarantino is clearly an aficionado of those traditions too. That influence should be taken into account for a fuller analysis of his narrative techniques. Also, too: The influence of Godard, especially in the “tardy” title insertions coming after the segment has started (e.g., one way to take “The Gold Watch”).

The expanded, stand-alone feature version of Death Proof displays block construction in filling out the “missing reel” portion of the first story and creating a new block, a ten-minute scene of the second “girl posse” at a convenience store. The scene starts with Stuntman Mike before shifting to the young women. It makes Mike even more a connecting link between the film’s two episodes, while Mike’s stalking and spying fulfills Tarantino’s claim that Death Proof is a slasher movie.

Embedded stories or flashbacks exemplify what researchers call “ring construction.” Bill Benzon has explored this in many critical analyses, as here with the 1954 Godzilla/Gojira.

For more on Inglourious Basterds, see our entry here and as revised in Minding Movies. We analyze the money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction. Kristin discusses the titles and segmentation of Hannah and Her Sisters in Chapter 11 of Storytelling in the New Hollywood.

Thanks to participants in the 2014 conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image for their comments on some of the ideas presented here. Thanks also to Matthew Bernstein, biographer of Walter Wanger, for in-depth discussion of Salome, Where She Danced.

Grindhouse (2007).

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS: A usable past

Hellzapopppin’ (1941).

DB here:

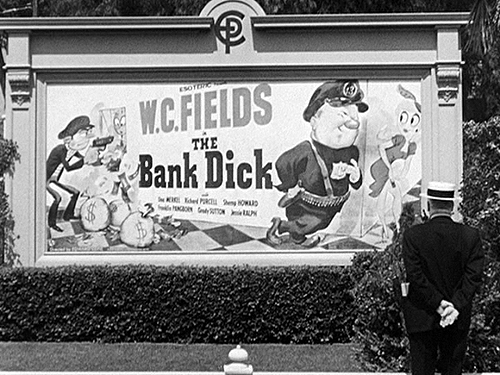

By now everybody is used to allusionism in our movies—moments that cite, more or less explicitly, other films. But we tend to forget that movies have been referencing other movies for a long while. One classic form is parody, as when Keaton’s The Three Ages (1923) makes fun of Intolerance (1916). Another example occurs in Me and My Gal (1932). Spencer Tracy tells Joan Bennett that he just saw a movie called “Strange Innertube,” and then Raoul Walsh gives us a comic version of the inner monologues used in Strange Interlude (1932).

Some allusions are in-jokes that sail by most viewers. Almost everybody notices when Walter Burns (Cary Grant) in His Girl Friday mentions that a character played by Ralph Bellamy looks like “that fella in the movies—you know, Ralph Bellamy.” Probably fewer people catch the later line, Walter’s threat to the authorities: “The last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.” Grant’s real name, of course, was Archibald Leach.

Week-End at the Waldorf (1945) is a sort of updating of Grand Hotel, so when one character remarks that a plot twist “is straight out of the picture Grand Hotel,” we probably catch the self-reference. But the other character piles on the allusions by replying: “That’s right. I’m the baron, you’re the ballerina, and we’re off to see the wizard.” Did people notice MGM congratulating itself twice? And you wonder how many viewers catch the spoiler in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), released only four months after Citizen Kane. Chic Johnson spots a Rosebud sled hanging outside an igloo and remarks, “I thought they burnt that.”

At the beginning of the 1940s, two novice directors seemed to be bringing fresh air to Hollywood cinema. Preston Sturges and Orson Welles were identified with innovative approaches to genre and storytelling. So we might expect them to inject something new into this practice of alluding to other movies. I think they did.

Consider a particular strategy that Sturges and Welles toyed with. Today, we enjoy it when a director treats characters in non-sequel films as sharing a fictional world. Tarantino imagines shifting his characters or brand names (e.g., Red Apple cigarettes) from movie to movie.

When I sell my movies, I retain the rights to characters so I can follow them. I can follow Pumpkin and Honey Bunny or anybody and it’s not Pulp Fiction II.

Jackie Brown (1997) features Michael Keaton as FBI agent Ray Nicolet, who also appears, played by Keaton, in Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998). The tactic fitted these directors’ adaptations of novels by Elmore Leonard, who tends to carry over characters from book to book.

It’s a bit surprising to see this impulse in Sturges and Welles too. The governor and the political boss in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) are McGinty and the Boss in The Great McGinty (1940), and they’re played (uncredited) by the same actors. A newspaper glimpsed in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) contains a column, “Stage Views,” by drama critic Jed Leland, a major character in Citizen Kane (1941).

Today fans are used to spotting things that most viewers might not get, but in the early 1940s, it was rarer. I’ve proposed earlier that sometimes Hollywood’s creative community is addressing not the broad audience but its own members, perhaps letting dedicated outsiders “overhear” the conversation. One example would be the nearly-hidden jokes that can be wedged into the background or on the edges of the action. In an entry about a year ago, I considered how sequences around the small-town movie theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek carry barely-noticeable jabs at current films, mostly those by Sturges’ home studio Paramount. And Luke Holmaas has pointed out to me that Hail the Conquering Hero contains a billboard advertising Morgan’s Creek—a sort of joking product-placement. Today, I want to suggest that Welles moved onto the same terrain but followed even more circuitous paths.

The past, not recaptured

Make pictures to make us forget, not remember.

Comment card from first preview of The Magnificent Ambersons, 1942.

The Magnificent Ambersons is, everybody knows, a film about the past. Its story action begins around 1885 and concludes just before World War I. Most of the plot concentrates on the decline of the Amberson family, due partly to financial mismanagement and the willful pride of Isabel Amberson’s son, George Minafer. Parallel to that decline is the development of the town into a city and the rise of the automobile company founded by Eugene Morgan, a failed suitor for Isabel’s hand. A major turning point comes when, after Wilbur Minafer’s death, Isabel is left a widow. She’d like to marry Eugene, but she declines because George is opposed. At the same time, George tries to win Eugene’s daughter Lucy. After the death of Isabel and her father Major Amberson, the family is destitute and George must find a way to support his aunt Fanny. Struck by a car, George is hospitalized, and only then does he reconcile with Eugene and Lucy.

After weak previews, the film was drastically recut, and some new scenes were shot. The original version has not yet been found, so we’re left with a ruined masterpiece. Still, there’s enough there to let us appreciate Welles’s effort to make sense of a crucial period of American history. Old money was giving way to modern, technology-driven fortunes; Eugene’s auto company is the Dell Computers of its day. The film also evokes changes in urban life, with shifting property values and rising pollution shown as consequences of progress. It’s the most downbeat of the “nostalgia” cycle of the 1940s, which includes Strawberry Blonde (1941), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Centennial Summer (1946).

Many other films have sought to present the past, recreating the settings and costumes and props of an era. But Ambersons is about pastness. It conveys a melancholy recognition that things are always changing, that we struggle to make sense of events only after it’s too late to affect them. It’s a film centered on missed opportunities and what might have been. Eugene might have married Isabel when they were young, but his drunken serenade turns her against him. If George weren’t such a prig, he might have reconciled himself to Isabel’s remarriage; only at the end, kneeling in prayer, does he seem to realize how his stubbornness cheated many people of happiness. The original ending would have shown Eugene visiting Fanny in a boarding house, with her long and unspoken love for him counterpointing his suggestion that he’s been true to Isabel.

Ambersons carries its sense of an unrecoverable past into the very texture of its telling. At first, the aura of things gone by is given by Welles’ voice-over narration. In affectionate comedy he introduces us to habits and routines of an era of streetcars and changing men’s fashions. After Eugene’s botched serenade, the townsfolk add their voices to the chorus with comments on the scandal. More backstory is given when George is shown growing from a spoiled boy to an arrogant young man. Our narrator recalls “the last of the great Amberson balls.” Eugene arrives, a widower, bringing his daughter Lucy, and George begins to court her that night.

Now the narrator’s past-tense explanation withdraws for some time. Instead, characters take up the burden of narrating the past. “Eighteen years have passed,” says Isabel’s brother Jack at the ball. “Or have they?” Before Eugene dances with Isabel, he remarks that the past is dead. Unfortunately, it won’t stay buried. The old romance between Isabel and Eugene will be rekindled, and bad business decisions and George’s spendthrift ways catch up with the family.

Welles’s plot construction relies on ellipsis. The scenes skip over major story events—Wilbur’s death, the decline of the family fortune, Gene’s second courtship of Isabel, and Isabel’s death. So much occurs offscreen that we are left to play catch-up. We must listen to characters report on what has just happened, or reflect on the more distant past. The film is built on recollection and reaction. We don’t see Fanny at Isabel’s deathbed; she simply flies out of the room to embrace her nephew: “She loved you, George.” We don’t see George and Isabel on their European trip; we learn of it from the doleful Uncle Jack, who thinks that Isabel is falling sick. This refracted narration allows Jack to voice his concern—he’s probably the one Amberson whose judgments we trust—and Gene to display helpless, rigid sorrow at the news.

One of Ambersons’ most famous scenes, the long take of George and Fanny in the kitchen, is characteristic. Under her questioning, he explains that Gene and Isabel were starting to reunite at his college graduation. A peppy nostalgia movie would have shown us that cheerful moment on the campus, but Welles channels the information through George’s insensitive report and Fanny’s uneasy questions—and the scene climaxes with her breaking down in tears. As ever, melancholy wins out. As a result of George’s telling, Fanny will plant the suspicion that gossip about Isabel has been destroying the family’s good name.

Similarly, another film’s finale would show the reconciliation of the young lovers, George and Lucy, in the hospital. Instead Welles’ original script presents that moment through Eugene’s somber report of it to Fanny in her boarding house. (In the version we have, we get the report in the hospital corridor.)

Sometimes, the gaps in time and action are abetted by the studio’s reediting. In the present version, we learn about Aunt Fanny’s failed investments later than in the original version. But even then the information would have been presented after the fact. On the whole, the sense of the sadly unalterable past is built into Welles’ screenplay. As each scene unfolds, we get news about what has happened in the gap since the last scene, or what has happened years before. At the railroad station, Uncle Jack, about to depart, recalls a woman he left here long ago. “Don’t know where she lives now–or if she is living.” Here the pastness he evokes is familiar to us from earlier in the film: “She probably imagines I’m still dancing in the ballroom of the Amberson mansion.” At the limit, Major Amberson’s garbled fireside reverie takes us back to the origins of life: “The earth came out of the sun, and we came out of the earth . . . so–whatever we are must have been in the earth.” Now the past is primeval.

Retro as remembrance

Welles enhances the aura of pastness through specific film techniques. Critics have rightly been alert to creative choices that carry over from Citizen Kane: looming sets, drastic deep-focus cinematography, low angles, chiaroscuro, and long takes, often employing splendid camera movements. But the film displays some unique choices that are, historically, anachronistic.

The most noticeable old-time technique concludes the idyll in the snow. Jack, Fanny, Lucy, and George are riding in Eugene’s horseless carriage. This, one of the few scenes that doesn’t replay the past in its conversation, is given special treatment as a moment out of time. The iris out that concludes the scene is something of a visual equivalent to the old song the riders sing, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

Similar is the vignetting that softens the edges of the opening sequences, starting with the first shot showing the streetcar stopping for the lady of the house.

Welles’ visual techniques aren’t faithful to the period when the story action takes place. Assuming that the snow idyll occurs around 1904, the iris wouldn’t have appeared in films of that time. And the earlier period of the streetcar shot and changing men’s fashions probably predates the invention of cinema. But by 1942, these techniques were associated with silent film generally and give a cinematic tinge of “oldness” to the action.

I say “by 1942” because recent years had made intellectuals especially conscious of film history. Several books, notably the 1938 translation of Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s Histoire du cinéma (translated as The History of the Motion Picture) and Lewis Jacobs’ sweeping The Rise of the American Film (1939) had concentrated on the stylistic innovations of Porter, Griffith, and other pioneers. With some theatres reviving silent classics like Caligari and The Birth of a Nation, cinephiles in urban centers had some opportunities to see silent movies. Most notably, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library was founded in 1935 and under the curatorship of Iris Barry, began building a permanent archive and screening retrospectives.

MoMA also assembled many films into traveling 16mm programs that could be rented by schools, museums, libraries, and other institutions. Silent films also circulated in 8mm and 16mm prints from private companies like Kodascope and Castle Films. Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, silent comedies were the most popular; Chaplin reissued The Gold Rush in a sound version in 1942. Welles’s interest in silent slapstick is shown in the recently discovered pastiche, Too Much Johnson (1938), which evidently owes a good deal to Entr’acte (1924), a MoMA-canonized classic.

Ambersons offers other, less obvious allusions to old cinema. One cluster of them comes during George and Lucy’s stroll along the sidewalk. George, somewhat petulantly, is insisting that his trip abroad with his mother may last a long time. “It’s goodbye, Lucy.” Angling for a declaration of devotion from her, he gets brittle, agreeable indifference. When he has stalked off, we learn that she is actually quite shaken by the prospect of separation. Watching the dramatic interplay in this long traveling shot, we are probably not likely to pay attention to the posters the couple pass outside the Bijou theatre.

The advertisements announce movies that could have played the Bijou in 1912. The ones in the rear of the lobby are impossible to make out, and there’s one outside I can’t be sure of. (See the codicil.) Raking the frames on DVD and on a good 35mm print, I’ve been able to discern The Bugler of Battery B (1912), Her Husband’s Wife (aka, How She Became Her Husband’s Wife, 1912), Ten Days with a Fleet of U.S. Battleships (1912; in the foyer), and The Mis-Sent Letter (1912). There were several Jesse James films circulating in 1911-1912, but one two-reeler named for the bandit (at the bottom of the second frame here) seems a likely candidate.

These casual background details betray extraordinary fussiness on the part of Welles and his colleagues. Few viewers would pay attention to all the posters, and very few viewers would realize that they’re all from the same year. It’s one thing to include authentic automobiles from the era, as car fanciers would be sure to spot mistakes. But 1912 two-reelers? It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the filmmakers put the posters in to satisfy themselves. (If you’re skeptical, I’d ask: If you’d thought of it, wouldn’t you do it?)

There’s more. The most prominent hoarding advertises a Western, The Ghost at Circle X Camp (1912), from Gaston Méliès. Surely the name also evokes Gaston’s brother Georges, by then an established pioneer of film history and a figure doubtless known to Welles. Is this a sideswiping tribute from one magician-cineaste to another?

There’s also a deliberate anachronism. Tim Holt, who plays George, was the son of action star Jack Holt. A lobby card over the box office announces “Jack Holt in Explosion.”

I can find no trace that such a film existed. Moreover, films of that era seldom identified the main actors in advertising, and in any case Holt was not a featured player in 1912. In order to create an in-joke/homage, Welles seems to have prepared a poster for a fictitious film—as Sturges did with Chaos over Taos and Maggie of the Marines in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

Perhaps the most sneaky allusion comes at the very end. After the florid voice-over credits for technical contributions, Welles intones: “Here’s the cast.” Medium-shots of the actors dissolve into one another as the voice-over identifies them. The images recall photographic portraits from the nineteenth century. They also seem to be a variant of those 1930s opening credits that catch the players in shots extracted from the movie to come. Still, there’s something peculiar about these.

Some of the actors look straightforwardly out at us, as we’d expect.

But others turn their heads slightly or shift their gaze, toward or away from us.

Sometimes the shift is tiny, as with the Joseph Cotten cameo. But the tactic is made into a joke when Tim Holt, staying in character, snaps his glance furtively to the camera.

Why these fillips? Here’s my conjecture. Some 1910s films, from both America and Europe, introduced their casts with shots of the actors standing as if on a theatre stage. The actors then looked to left, then right, pretending to take in all sides of a live audience. Here’s an example from Reginald Barker’s The Wrath of the Gods (1914), featuring actor Thomas Kurihara.

None of the 1910s examples I know was framed as closely as Welles’s shots are. But I surmise that Welles offered a modernized variant of a minor silent-film convention. If this is right, it has to be an allusion more far-fetched than even the ones Sturges supplied.

Maybe I’ve gone too far. Once filmmakers start playing these games, overreach is a constant temptation. In any case, I think there’s enough evidence that Welles, like Sturges, was invoking early film history as a way of reinforcing the overall pastness-strategy of his film.

I’d go further and speculate that Welles’s obsessively pinpointed allusions may have stirred a competitive spirit in Sturges. Now we can see the Miracle of Morgan’s Creek tracking shot past the movie house posters as a variant, two years later, of the angle Welles chose for his long take.

And perhaps the audacious inclusion of footage from The Freshman (1925) at the start of The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) was sparked by Welles’ virtuosically faked newsreel in Citizen Kane. As the two boy wonders from the East took advantage of the biggest train set a kid could play with, they may have egged each other on.

For more on the practice of allusionism and world-building see The Way Hollywood Tells It. Thanks to Ben Brewster for information on Jack Holt’s career. My quotation of the Ambersons preview card comes from Simon Callow’s Orson Welles vol. 2: Hello Americans (Viking, 2006), 87.

The Holt and Méliès posters are mentioned in the cutting continuity in Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction (University of California Press, 1993), 214. Alas, the other posters aren’t specified.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster’s illustration, which we can glimpse more fully in a later phase of the shot, shows a man thrashing an American Indian while a woman stretches out her arms in the cabin in the background. At first I thought the first words are The Car, but I can find no film from the period that begins with that phrase. (It would fit more closely with Ambersons thematically than most of the other titles, but in fact “car” wasn’t then a common term for automobile.) Then I thought it was The Coin Box Girl, but again no such film seems to have existed, and that title is hardly in keeping with the illustration. Any ideas?

Yes, I know. Welles would have had a good big belly laugh at these efforts.

P.S. 10 June: I’ve been pursuing some readers’ leads about the still-mysterious poster. In the meantime, Joseph McBride has has corresponded with me with more ideas and information about Ambersons. Joe is the author of many books, including What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career, Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless, and Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit, a meticulous study of those two murders. He is one of the world’s top Welles scholars, so naturally I’m happy to pass along his thoughts.

AMBERSONS is my favorite film, as you probably know, even in its partly ruined state. I think all your analysis is acute, and I like your focus on the self-conscious awareness of pastness that Welles conveys and dissects in the film. The film is redolent of Welles’s youth and even more so of the period before he was born (the period for which I find most of us are most nostalgic). Nostalgia was considered a neurosis in the pre-modern era, a sign of inability to adjust to reality rather than the warm-and-fuzzy state it’s thought of being today. There’s a deep melancholy throughout the film, even if Welles, good magician that he is, distracts us with misdirection via comedy in the beginning while simultaneously laying the seeds of destruction and foreshadowing George’s “comeuppance,” etc.

Last month I was at the Welles conference in Woodstock, Illinois, which has preserved much of its nineteenth-century flavor, including the Opera House where Welles put on TRILBY (but most of the Todd School for Boys he attended is gone). That town and its main square, with bandstand and Civil War monument, seems very Ambersonian as well. I have always seen AMBERSONS as Welles’s most deeply personal film, and his claim that Eugene Morgan is partly based on his father (and that Booth Tarkington knew his father) is noteworthy, as is George Amberson Minafer’s evil-twin resemblance to the young George Orson Welles.

I would only add to your insights that there was much more about the loss of the Amberson fortune in the full version of the film (you allude to that a bit), even though, as you intriguingly note, Welles employs an elliptical style throughout. Welles’s use of ellipsis is Lubitschean (he considered Lubitsch a “giant”), although used for somewhat different reasons, Welles doing so mostly to condense the story in witty ways (and, as you observed to me, focus on characters’ emotional reactions to offscreen events, in the manner of Henry James) and Lubitsch to evade censorship while providing subtle rather than blunt treatments of sex. And some of Lubitsch’s German films, as you know, start with specially posed head shots of him and his main actors, somewhat similar to what Welles does at the end (though he teasingly keeps himself out of frame, partly to stress the voice aspect and also to keep the identification of himself with George stronger). Tim Holt gazing accusingly at us in the end credits is startling — maybe it’s not only to keep him in character but also to say, “I’m you.”

Welles is terrible (archy, corny, and putting on a phony kid voice) as George in the radio version, which, however, is much like the film in some ways. During the night devoted to radio in the 1978-79 “Working with Welles” seminar I co-hosted for the AFI at the DGA Theater, Welles’s longtime associate Richard Wilson and I ran the first ten minutes of the radio show as the soundtrack for the film imagery, and it worked amazingly well. Welles’s use of ellipsis in the film recalls his radio work, in which he and his writers would condense a large novel into one hour, etc. The vignettes at the opening of AMBERSONS are very much drawn from radio. He sold the project to RKO’s George Schaefer by playing the radio show, though the fact that Schaefer fell asleep before the end might have given them pause.

Welles said he included the “Jack Holt in EXPLOSION” gag did to please Jack when he visited the set. Jack was an action star for Capra before AMBERSONS and turns up in THEY WERE EXPENDABLE, in the scene in which John Ford pays homage to his high school teacher Lucien P. Libby by naming a boat after him. Another of those in-jokes that permeate even classic Hollywood, as you say. Mr. Libby influenced Ford’s portraits of Lincoln and other folksy politicians as humorous storytellers.

Welles’s early films show a keen awareness of film history and culture, more than he would let on later he knew at that young age. He described THE HEARTS OF AGE to me as a spoof of THE BLOOD OF A POET and LA CHIEN ANDALOU. TOO MUCH JOHNSON is full of film influences and allusions (I think I sent you my essay on the film from Bright Lights. And KANE has its share of in-jokes, such as Gregg Toland interviewing Kane on board a ship and Kane responding with his first words in the film after “Rosebud” — “Don’t believe everything you hear on the radio.”

Thanks to Joe for corresponding.

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941).

Caught in the acts

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005).

DB here:

If you’re interested in how films tell stories, I think that you’re interested in several dimensions of narrative. Those include the story world (characters, settings, action), narration (how story information is parceled out as the film unrolls), and plot structure (the arrangement of parts).

Plot structure matters because a movie’s parts, like parts of a song or a symphony, help shape our experience. Just as a “curtain line” makes us return after intermission, a cliff-hanging climax to a TV episode makes us tune in next week–or click to continue, if we’re binge-watching. Accordingly, storytellers reflect on how to chop up and lay out sections of their plots. Novelists fret over chapter divisions, TV writers massage their scripts to allow for commercial breaks, and playwrights map action into acts.

The idea of act-structure has passed into commercial screenwriting as well. Just when that happened is hard to say, but certainly by the 1980s scriptwriters consciously broke their screenplays into big chunks. That trend was largely the result of Syd Field’s 1979 book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, although some of his points had been anticipated in Constance Nash and Virginia Oakley’s Screenwriter’s Handbook (1974). From these books came the idea that a feature film script had a three-act structure, measured by time segments (30 minutes/ 60 minutes/ 30 minutes). The prototype was a 120-minute film, with each script page running about one minute of screen time. Field fleshed the model out by noting that “plot points” at the ends of acts one and two turned the conflicts in a new direction. Although other writers argued for other templates, and Field’s model was refined (what’s the “inciting incident” in Act One?), versions of the three-act model still rule the international film industry.

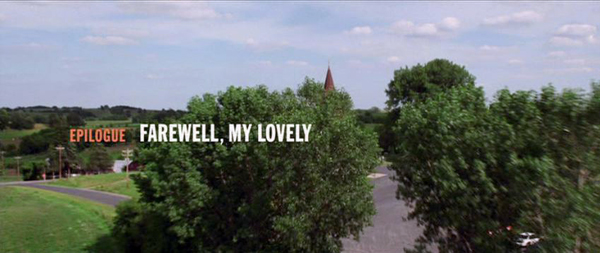

Field presented his anatomy as an analysis of hit films like Chinatown and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He suggested it as a template for a successful plot. As Field’s book gained prominence, his guidelines gave production companies an heuristic for triaging submissions. Now a story analyst could simply check pages 25-35 and 55-65 for turning points, and “incorrect” scripts could be discarded immediately. (But see P.S. below.) Through a feedback cycle, the Field model became a guide to both screenwriters and industry decision-makers. Inevitably, the whole thing got mocked. The day-by-day structure of Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang parodies Field’s scheme, and it closes with a self-conscious epilogue. “So,” says the narrator, “that’s pretty much that….”

To what extent, though, was the three-act structure employed in earlier eras? Field’s original edition drew its examples from current hits, but he implied that classics would display the same underlying architecture. Kristin, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, claimed that four parts were more common than three, and she supported her analysis with examples from films from the silent era and the classic studio years.

But film analysis depends on your perspective. In any movie you can find patterns different from the ones I find, and each of us can make persuasive cases. It would be valuable to know whether American screenwriters in the studio system consciously worked with an act-based model. If they did, what assumptions did they make about the length and organization of each act?

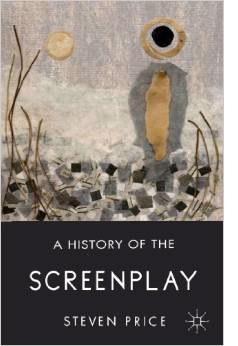

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

For some time, I’ve held the same view. I couldn’t find any script draft broken into acts. Some veteran screenwriters admitted using a three-act model in plotting, but their testimony came long after the era. So, for instance, Philip Dunne says he used a three-act organization for his 1940s screenplays, but he makes the claim in an interview published in 1986. Billy Wilder says he “wrote [Charles Boyer] out of the third act” of Hold Back the Dawn (1941), but the remark comes in an interview given decades later. There’s always the possibility that older writers, newly aware of the Fieldian template, were projecting it backward onto their work—assuring us that they conform to contemporary standards, or even asserting precedence.

Similarly, we can’t rely too much on secondary sources. True, screenplay manuals, from at least 1913 onward, have recommended a three-part structure, purportedy corresponding to Aristotle’s idea that a plot must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But this rests on a misunderstanding. As I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle isn’t talking of acts; ancient Greek plays didn’t have act divisions. And almost none of the manuals use the term “acts” to describe the parts.

Richard Brooks’ novel The Producer (1951), about a weak-willed executive trying to do the right thing, offers some hints along similar lines. He mentions that a screenplay should run to 120 pages, confirming the canonical length that Field proposes. Likewise, Brooks obliquely appeals to Aristotle.

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter has to create a beginning, a middle and an end, and all the dialogue.

Perhaps there’s an intentional irony in the fact that Brooks’ Hollywood exposé is itself broken into three parts, labeled “The Beginning,” “The Middle,” and “The End.”

Unlike many authors of manuals, Brooks was an established screenwriter, and we might expect his novel to refer to acts. It doesn’t. But Lewis Herman, a minor scribe with three screen credits (including Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation), does. His 1952 manual declares that a feature-length film is built upon “a three-act theme outline.” The context suggests that the Hollywood studios demand this as a step toward developing a full screenplay. Herman usefully illustrates the outline with a hypothetical example.

Still, manuals or novels aren’t ironclad sources for studio practice. Better would be contemporaneous evidence from memos, story conferences, and similar unpublished documents. Claus Tieber has done extensive research into such sources and has found no discussions of three-act structure. I’ve found a few, but they’re fairly sketchy.

Overseeing Casablanca, Hal Wallis told Michael Curtiz, “The Epsteins have agreed to deliver the film’s ‘second act’ the following day.” Darryl F. Zanuck mentioned the “last act” in correspondence about Viva Zapata! and On the Waterfront. Supposedly John F. Seitz asked Preston Sturges about the flashback structure of The Great Moment: “Why did you end the picture on the second act?” As I noted in an earlier entry, David Selznick’s papers record a story conference on Portrait of Jennie in which Jed Harris remarks: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” He adds that at this point the film “is about 1/3 gone.” This suggests that some practitioners thought of the parts as roughly equal in length. (Kristin’s model proposes that this was the case.)

It may be, of course, that three-act structure of some sort was so ingrained in studio writers’ habits that they didn’t have to discuss it explicitly. Field was addressing aspiring screenwriters who wanted inside knowledge, but as intuitive craft workers, the old contract writers wouldn’t be likely to spell out rigid rules about length and dramatic patterning.

Since corresponding with Steven for his book, I’ve found that one screenwriter explicitly invoked three-act structure in his working notes. And I’m embarrassed not to have noticed it earlier.

Coupling, recoupling, and Joe Breen

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham.

NICOLAS: Marriage has its phases–its acts–like anything else. This is another act, that’s all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, screenplay for Infidelity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career was mostly a fiasco. Thanks to temperament, a mentally disturbed wife, bouts of breakdown and alcoholism, and an implacable industry, he worked his way down the hierarchy to unemployment. From July 1937 to his death in 1940, he earned screen credit for just one film, Three Comrades (1938). He also started, but didn’t finish, the best Hollywood novel I know, The Love of the Last Tycoon (aka The Last Tycoon). I think it spells out some features of the Hollywood aesthetic with special vividness.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

Back in the present, to ramp up his mood, Nicolas decides to hold a party in the country estate he had more or less abandoned. At the same time, Althea rekindles her friendship with a former suitor, Alex. She can’t arouse herself to passion, though, and Alex leaves her. As she drives more or less hysterically to the estate where the party is in full swing, Nicolas is wandering through his mansion among the shrouded furniture.

At this point, because of objections from the Production Code office, Stromberg halted Fitzgerald’s work on the screenplay. Aaron Latham’s biography tells us that Fitzgerald had planned to present a reconciliation, in which a photographic trick presents Althea seeing herself as Iris and thus forgives Nicolas. But this ending would suggest that the husband’s sin went unpunished. Fitzgerald suggested an alternative, but this too was rejected by Joseph Breen. He tried to redraft the script later in 1938, but the project dissolved.

Fitzgerald had systematically studied Hollywood releases, even filing plot synopses on index cards. Accordingly, the Infidelity screenplay we have shows an awareness of 1930s storytelling conventions: montage sequences, wordless scenes, and revealing visual detail. We learn that Nicolas’ ardor is cooling when we notice that he has stopped opening Althea’s letters. Fitzgerald’s acquaintance with current trends led him to a thumbnail characterization of Althea’s friend Alex:

He is the type played by Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth–handsome, attractive, worthy, thoroughly admirable, but somehow too heavy in manner to grip the sympathy of an audience if playing opposite a man of charm.

Occasionally, voice-over dialogue in the present is matched with images in the past, in the manner of Sturges’ “narratage” in The Power and the Glory. (See our entry here.) And the large-scale flashback structure, leaving a key action in the present suspended for nearly an hour, anticipates a mode of construction that would be common in the 1940s.

Despite its up-to-date air, the plot of Infidelity creaks a bit. It relies on a great many coincidences and introduces rather late a major menace, a sinister surgeon who seems slated to play the disruptive role of George Wilson in Gatsby. But what’s of special interest to us is a schedule of work that Fitzgerald sent to Stromberg during the planning stages.

Fitzgerald groups his scenes into clusters, and alongside each one he notes a date on which he expects to complete it. Since each scene usually runs only a couple of pages, the groupings present a feasible day-by-day timetable. These clusters of scenes are gathered into eight “sequences,” labeled with Roman numerals. In the 1930s, a “sequence” meant, according to screenwriter Frances Marion, “a series of scenes in which the action is continuous without any break in time.” Each of Infidelity‘s sequences presents a unified phase of the action and is more or less continuous in time, although there are some ellipses as well.

Here’s the news: Fitzgerald’s timetable assembles the sequences into acts. Sequences I through IV are labeled “FIRST ACT 45 pages.” Sequences V through VIII are labeled “SECOND ACT 50 pages.” Sequence VIII is continued to form “THIRD ACT 25 pages.”

The first act establishes the loveless marriage and launches the flashback. While Althea is away, Nicolas re-encounters Iris. Meanwhile, as Althea and her mother are on their way home, they conveniently run into her old beau Alex. Their departure for the United States ends this setup. In the screenplay Fitzgerald has typed: “The First Act may be said to end here.”

The second act develops the conflict to a point of crisis. Althea returns a week early to find Iris at breakfast with Nicolas. She resigns herself to a loveless union. Back in the present, he plans the party and at the instigation of Althea’s mother Alex starts to woo her. But he abandons Althea, and by chance she’s found by Dr. Borden, whom she starts kissing. In the notes for Sequence VIII, Fitzgerald cryptically ends the act on an alternation between the couples:

CUT TO husband and back to old beau [Alex]

[Alethea] with beau [Alex]

Crisis with beau and switch [to the surgeon, Dr. Borden?]

CUT TO husband

After presenting this alternation in scenes, the manuscript concludes:

Full shot of a bedroom, large and luxurious like everything else in this house. Soft lighting, everything covered with cloth or canvas.

Nicolas Gilbert is standing in the middle of the floor.

Close shot of Nicolas.

This is presumably the end of the passage labeled “CUT TO husband.” In the Stromberg schedule, this last portion marks the end of Act Two. Act Three isn’t in the canonical version of the screenplay.

A couple of final points about the structure. Although the screenplay is estimated at 120 pages, its proportions don’t conform to the Field paradigm. At 25 pages or minutes, the third act is short. This is a characteristic of both modern and older Hollywood climax sections. But Act One was projected to be very long at 45 pages, and Act Two approximates it at 50. Fitzgerald’s layout is perhaps more characteristic of a stage play, which can afford a longish exposition and equivalent second act. In the script version we have, both acts run equivalent page lengths.

Fitzgerald may have expected some trimming and compression at later stages. In The Producer, Brooks’ protagonist notes that a 120-page script would usually be cut down to 90 minutes because exhibitors wanted films at about that length. It’s true that few films of the studio era run to two hours.

Set aside brute measurements. What, in Infidelity, makes an act a coherent unit? Not a specific span of time. Act One breaks off partway through the flashback, and Act Two ends before the evening party does. The first act ends when we know a crisis is coming: Althea is returning home early and hasn’t told Nicolas, whom we’ve seen flirting with Iris. Act Two ends at another high point. Nicolas confronts the emptiness of his life without his wife, and nearby Althea is heedlessly making love to a stranger with dubious designs. We could easily imagine the script as a stage play, with a curtain ringing down on each of these teasing situations.

In sum, we have one clear-cut case of a studio screenwriter laying out his plot in three acts. We can’t generalize from a single instance, of course, and we would need many more pieces of evidence to consider this a widespread writing strategy. Perhaps Fitzgerald isn’t typical. Did his relative inexperience as a screenwriter make him rely on a theatrical template that others could do without? Did he employ it more as a rhetorical device to convince Stromberg that the plot was firmly constructed? Still, taken with the reminiscences of Dunne, Wilder, et al. and the sketchy mentions we have in production records, the Infidelity project suggests that some conception(s) of three-act structure were operative in the studio period.

Needless to say, we’ll need even more evidence before we can begin to consider whether the filmmakers’ craft practice matches the structural patterns that today’s analysts disclose in the films. The search continues!

The Fitzgerald outline is reproduced on pp. 161-162 of Aaron Latham, Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood (Viking, 1971). This book is not only a stimulating account of the novelist’s Hollywood years but also a helpful view of the movie colony’s culture. My discussion relies upon the version of Infidelity published in Esquire 80, 6 (December 1973), 193-200, 290-304. It is available in a digitized version here. The original manuscripts are in the University of South Carolina library.

Philip Dunne’s remarks about three-act structure are in Pat McGilligan, Backstory (University of California Press, 1988), 158. Billy Wilder’s remarks come in George Stevens, ed., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (Knopf, 2006), 316. (In the same interview Wilder claims that Some Like It Hot has four acts.) Richard Brooks’ The Producer (Simon & Schuster, 1951) is worth reading for its almost documentary survey of the process of production at the period. Lewis Herman’s Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films (World, 1952) is an unusually detailed guidebook.

On Wallis’ memo about Casablanca‘s second act, see Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Visual Design Program of Casablanca,” Post Script 9, 3 (Summer 1980), 38. For Zanuck’s comments see Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years at Twentieth Century-Fox, ed. Rudy Behlmer (Grove, 1993), 173, 226. Seitz’s remark to Sturges about The Great Moment is quoted in James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt, Brace, 1982), 172. There’s more discussion in our blog entry on The Great Moment.

I take Frances Marion’s definition of “sequence” as a bundle of scenes from her How to Write and Sell Film Stories (Covici-Friede, 1937), 373. Tamar Lane offers a comparable definition in his New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936), 123. Interestingly, Lane adds that some scenarists think of each sequence as moving toward a high point, like an act in a play; but this seems only a rough analogy, and the comparison entails that a script would have several more “acts” than three. Steven Price suggests that the “sequence” as an extended script segment emerged in the silent period and hung on in some sound screenplays; see A History of the Screenplay, especially 63, 115-116, and 153-157. At the same time, “sequence” could refer to a single brief segment, as in “action sequence” or “montage sequence.”

Thanks to Steven Price and Claus Tieber for correspondence about act structure. Claus has a relevant case study of Grand Hotel, “‘A Story Is Not a Story But a Conference’: Story Conferences and the Classical Studio System,” in Journal of Screenwriting vol. 5, no. 2 (2014): 225-237. More generally, I’m grateful to researchers at the Screenwriting Research Network for what I’ve learned from their conferences in Brussels in 2011 and in Madison in 2013.

Other entries on this site have considered act structure. Kristin explains her model, based on goal formulation and injections of new information. She expands on this as it affects character subjectivity and point of view. I illustrate her model with reference to what is supposedly the most wayward and narratively fragmented modern genre, the action picture. I offer some general reflections on how the four-part structure informs not only current films but best-selling novels. For a more general discussion of the dimensions of film narrative, you can download this chapter from my Poetics of Cinema. Also, too: there’s the precept that form follows format. Finally, I consider modern trends in screenplay construction, including act structure, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

After a while you see the triplicate scheme everywhere. In Case History of a Movie (1950), p. 30, Dore Schary says that Charles Schnee turned in the script of The Next Voice You Hear in thirds. Acts? I’ll have to get back to you.

P.S. 19 May 2014: In reply to this post, Greg Beal comments that my discussion of rejecting screenplays based on Field’s plot points is inaccurate.

My claim was, I now think, an overstatement. I should not have suggested that the absence of canonical plot points would be sufficient to doom a screenplay. Naturally, I realize that the analyst would still be obliged to write fuller coverage. I meant simply that the Field template could set up expectations that the script wasn’t written to standard. Other factors would surely be taken into account in a final decision. The larger point, that three-act structure along Field’s lines shapes analysts’ judgment, remains to be determined.

My most concrete evidence for the saliency of the three-act, plot-point model in this production context comes from two manuals by story analysts. T. L. Katahin’s Reading for a Living: How to Be a Professional Story Analyst for Film and Television (Blue Arrow, 1990) recommends that analysts look for three acts, including a ten-page initial setup followed by a development and two further acts that forward the protagonist’s goals. But Katahin doesn’t propose exact page counts for further twists.

More specific is Jennifer Lerch’s 500 Ways to Beat the Hollywood Script Reader: Writing the Screenplay the Reader Will Recommend (Simon and Schuster, 1999). In following the three-act layout, she suggests that Act One, the setup, be consummated between pages 20 and 30 (ideally consisting of two scenes 10-15 pages each). Act 2, as per Field, is said to run long, up to pages 80-90, and typically consists of four to eight sequences (each 10-15 pages or so). This act is said to lead to a point of no return, the pivot-point for Act 3.