Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Innovation by accident

DB here:

The old drama is being reenacted before our eyes, and as often happens, Harvey Weinstein plays the villain. The American release version of Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, which has cut and changed the original, is being decried as a travesty, the dilution of an artist’s original conception in the name of what somebody thinks will sell.

I take up The Grandmaster in another entry. For now, I just want to point out the archetype goes back long before Harvey came on the scene. A screenwriter or director comes up with a fresh approach to telling the story. But a producer rules it out as something the audience won’t buy, or even understand. Moral: In Hollywood, the creative force is stifled by a money person who insists on doing things as usual.

The 1940s in Hollywood was an era of narrative innovation. It gave us weird dream sequences and insane protagonists and subjective point of view and byzantine flashbacks and talking houses and complicated replays of action we thought we understood. While working on a book on this era, I’ve begun to wonder what the limits of innovation might be. What could make the boss tell the filmmaker that a particular narrative choice just went too far?

Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy production

A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

One example I found was purely anecdotal, but nifty nonetheless. In preparing the screenplay for Out of the Past (1947; aka Build My Gallows High), screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring wanted to have the story told by a deaf-mute boy. Apart from the fact that the boy plays a minor role in the opening of the film as it was finished, the idea of someone who cannot hear or speak serving as narrator proved to be something of a stretch for the time. Mainwaring reports that the idea was rejected.

That’s the kind of thing I wanted to find. Yet my searches sometimes came up with cases where the producer’s notes actually resulted in improvements. Take A Letter to Three Wives (1949), justly praised as one of the best films of the 1940s.

John Klempner’s original novella (published in 1945) and novel (1946), both titled A Letter to Five Wives, obviously involved two more couples. After some other writers had drafted versions, Vera Caspary was assigned to prepare a treatment. Probably with the input of producer Sol Siegel, she eliminated one couple. Her adaptation already contains much of what is distinctive about the movie as we have it. Instead of the many distributed flashbacks in the originals, the treatment consolidated them into three lengthy ones. At Siegel’s suggestion, Caspary brought the three women together on the boat. To Fox studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck we apparently owe the idea that one woman, Deborah, would be the primary vehicle of our sympathy and would initiate and resolve the mystery of whose husband has defected. Above all, Caspary’s treatment includes the unforgettable voice-over of the never-seen Addie Ross.

When director Joseph L. Mankiewicz saw Caspary’s final adaptation, in effect “A Letter to Four Wives,” he declared he “looked upon the Promised Land” and quickly turned it into a screenplay. After reading Mankiewicz’s screenplay, Zanuck intervened again , demanding that another wife be lopped off. Mankieiwicz called this “an almost bloodless operation.”

It’s probably irrelevant that A Letter to Three Wives won that year’s Academy Awards for best screenplay and best direction. Even if it hadn’t been honored, after reading the original tales and Caspary’s adaptation, I have to conclude that the film is the best version of the lot. I suppose it partly goes to show the old rule that bad or so-so books can make very good movies. (Exibit A: The Birth of a Nation; Exhibit B: The Magnificent Ambersons; Exhibit C: The Godfather. Defense rests.) But clearly, the cuts and changes demanded by Siegel and Zanuck improved the property. The “creatives”–Klempner, Caspary, Mankiewicz–were by force majeure steered toward good results.

You can argue, though, that no written version of the film tried to be innovative, except perhaps for the device of Addie’s spectral presence. And Mankiewicz declared himself happy to make the adjustments. What about cases in which genuinely bold ideas were curtailed by the powers above? So I looked into two titles that, when released in the producers’ cuts, were denounced by their writer-directors.

Two years after Preston Sturges finished and cut his film about the discovery of ether anesthesia, Paramount producer B. G. “Buddy” DeSylva supervised and released a reedited version called The Great Moment (1944). Sturges noted of the film:

It is coming out in its present form over my dead body. The decision to cut this picture for comedy and leave out the bitter side was the beginning of my rupture with Paramount. . . The dignity, the mood, the important parts of the picture are in the ash can.

A second example is a more famous release, Twentieth Century-Fox’s All About Eve (1950). After the success of A Letter to Three Wives, Zanuck allowed Joseph L. Mankiewicz to film his three-hour screenplay as a “shooting draft.” When Zanuck saw the result, he insisted on cutting it to 138 minutes.

Throughout his life Mankiewicz was an angry man. His interviews and writings excoriate mothers, film festivals, doctors and nurses, Michelangelo Antonioni, television, the American male, theatre operators, Graham Greene, the AFI, PBS, Richard Nixon, Dennis Hopper, The Untouchables (film version), British craft unions, and other malefactors. High on the list was Darryl F. Zanuck. Long before the Cleopatra debacle, Mankiewicz was already carrying a grudge because Zanuck removed a replayed scene from All About Eve. He definitely didn’t consider that a bloodless operation.

Zanuck had final cut and he got bored with the same scene shot from different points of view.

Here, I thought, were sterling examples of creators bumping up against what was impermissible. Yet the more I looked, the more I found that the situation couldn’t be reduced to the daring director versus the philistine producer. I was forced to consider the possibility that the producers’ changes yielded not timid conformity but instead some unpredictable results–things that were themselves novel, in intriguing ways. The suits hadn’t intended to do something bold, yet in revising and patching up the films shot by two venturesome directors, they actually found themselves pulled in new directions.

Call it inadvertent innovation. Not surprisingly (this is the 1940s), it involved flashbacks.

Which great moment?

Kitty Foyle (1940).

By the early 1940s, movie flashbacks adhered to several conventions that we still recognize. Typically, we’re given a situation, the narrative Now, in which a character is recounting or simply remembering past events. We then move to those events, a shift often signaled by a track-in, a musical cue, a dissolve or other optical effect, and/or sounds from the next sequence mingling with the spoken transition. We may hear the voice-over remarks of the lead-in character at times during the action we see. Once the flashback action is complete, we return to the present, with the character who launched the flashback finishing the testimony or closing off the memory. And if the film includes several flashbacks, they are typically presented chronologically, so that the earliest events from the past are shown before later ones.

Kitty Foyle (1940) offers a clear example. In the present, Kitty recalls her romances. As they develop, we return to the present at key moments to gauge her reactions. For the sake of clarity, the romances themselves are shown to us in 1-2-3 order, tracing the events that lead up to the crisis that launched her memory journey.

Not all flashbacks respect chronology, though. Citizen Kane’s first flashback traces Kane’s career as the banker Thatcher knew it. His recollections show us Kane as a child, a young man, and then a much older man forced to sell his newspaper empire. The next flashback, as recounted by Kane’s business manager Bernstein, takes us back to show Kane as a young man assuming control of his first newspaper. Several years before Kane, Sturges had composed a script based on similarly shuffled chronology. The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard, presents an old man recalling episodes in the life of tycoon Thomas Garner, and those are presented out of 1-2-3 order. (I analyze that film here.)

Sturges was confronted by the problem of order in preparing Triumph over Pain. This project would tell the story of Dr. W. T. G. Morton, the popularizer of surgical anesthetic. Biographical films about scientists and inventors had become a successful cycle in the late 1930s, but Sturges wanted to stay fairly close to the facts. The problem was that Morton’s story couldn’t lead easily to a triumphant finale. Sturges noted dryly:

Dr. Morton’s life, as lived, was a very bad piece of dramatic construction. He had a few months of excitement ending in triumph and twenty years of disillusionment, boredom, and increasing bitterness. . . . To have a play you must have a climax and it is better not to have the climax right at the beginning.

Accordingly, Sturges had somehow to rearrange portions of Morton’s life.

Since [the writer] cannot change the chronology of events, he can only change the order of their presentation.

The title Sturges gave to his final version, Great without Glory, indicates its tone. A quasi-documentary prologue hails the modern benefits of anesthesia. We move to the late 1800s, when Morton’s friend Eben Frost finds a medal given to Morton now sitting in a pawnshop. He brings the medal to Morton’s widow Elizabeth, and as they sit in her parlor, the film’s first long flashback starts. It presents the public celebration of Morton’s triumph, as he and Eben are driven through the crowded streets.

The ensuing scenes trace the aftermath of his discovery—the fact that he could not patent it, his efforts to build a business on sale of ether bottles, a bout of illness, and then his receiving the medal while he is plowing on his farm.

Sturges’ version returns to the narrating frame, as Eben examines some more personal memoirs that Elizabeth has written. The second flashback initiates the play with chronology. It traces events leading up to the action we saw completed at the start of the first one. The plot takes us back to the couple’s courtship, the first years of Morton’s dentistry practice, and his arduous experiments with ether. He finds prosperity using it on his patients. Challenged to demonstrate his invention in a public surgical operation, he realizes that his demonstration will show his rivals his trade secret. He is about to leave the operating theatre when he sees the patient: a girl about to have her leg amputated. Unable to let her face agony, he turns back to reveal his discovery to his peers.

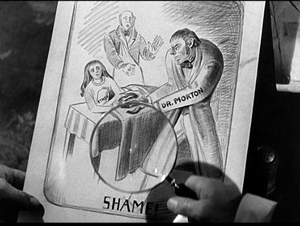

The plot’s true climax is Morton’s gesture of sacrifice. Sturges encourages us to see it as a contrast to the way the press and his profession vilified him. During the first flashback, a newspaper cartoon shows Morton preying on innocent patients, as typified by a girl on a gurney.

Sturges expected us, I think, to recall this image when Morton decides to help the girl. In his life, the cartoon came later, but showing it early in the film lets Morton’s gesture serve as a rebuke to those who are going to hound him.

After revealing Morton’s sacrifice, Great without Glory provides a bitter epilogue. The film ends with a return to the framing situation in Elizabeth’s parlor. Eben rises sadly, leaving Elizabeth alone.

Sturges could simply have built his film around Morton’s early life and his successful discovery, ending before the decades of poverty that followed. Instead, by focusing his biopic around our failure to appreciate and reward selfless research, he wanted to praise a man who achieved greatness but not the long-lived veneration accorded Edison or Pasteur. Yet showing Morton’s fall from grace after the crowd’s acclaim meant that the high point of a science biopic would be accomplished far too early in the plot. What we today call the “darkest moment”—Morton’s rejection by his public and his poverty—would come too soon. When Sturges showed his cut to his friend John Seitz, a great cinematographer, Seitz asked: “Why did you end the picture in the second act?”

According to Sturges, Buddy DeSylva said the same thing. He was already hostile to Sturges, and after some mixed preview results he set about reshaping the picture. The result is a good example, I think, of unintended innovation.

DeSylva did, as Sturges indicated, “leave out the bitter side” in certain respects. He lopped off the final scene showing the mourning of Eben and Elizabeth. The Great Moment doesn’t return to the narrating frame set up from the start of the picture. This is a little disconcerting structurally, but it wasn’t unknown at the period. Guest in the House (1944), Dillinger (1945), and other films “forget” the fact that they began with a character recalling the past.

Nor did DeSylva start the plot with Sturges’ prologue and narrating frame. He offered something immediately upbeat: Morton and Eben descending to the cheering crowd and riding through the streets to acclaim. This action, surprisingly, takes place during the credit sequence.

By inserting the moment of Morton’s triumph at the very start of the movie, before we have even seen a flashback to it, or indeed even know who these people are, DeSylva seems to illustrate the film’s title. Our first impression is that Morton’s great moment is the public recognition of what the crowds’ placards announce is his conquest of pain.

Only after this “flashforward” does the release version settle down to something roughly like Sturges’ structure. Eben discovers the medal, brings it to Elizabeth, and elicits her recollections. Some of the scenes are rearranged from Sturges’ version; the placement of one, showing Morton sick in bed, seems calculated to lead in to his death (as it doesn’t in the Sturges cut). The newspaper cartoon is there, ready to form a parallel with the climax. As in the Sturges version, a return to the narrating frame shows Eben and Elizabeth in the present launching the second big flashback. With other alterations, we go through the couple’s romance and marriage, culminating in the discovery of ether and the prosperity of Morton’s practice.

DeSylva retains Sturges’ climax: the scene when Morton must choose whether or not to reveal his trade secret to his competitors in the public demonstration. Seeing the girl praying on the gurney, he decides to do it. The film ends with him striding into the operating theatre, about to share his discovery. It is here that DeSylva halts the film, without, as we’ve seen, returning to the frame featuring Eben and Elizabeth.

Both locally and more broadly, the effect is curious. Now Morton’s great moment is revealed, as Sturges wished, as the moment of his self-sacrifice, not the moment of his celebrity. But more strangely, without the final frame situation, the film ends just before the opening credits sequence. We could easily imagine the credits as an epilogue, with Morton’s entry to his colleagues dissolving to the parade in his honor before the final fade-out. Instead, the film halts and wraps back around itself like a Möbius strip: the last thing we see immediately precedes the first thing we saw.

I’m not trying to make this movie Memento or Primer, but there is something uncanny about the release cut’s looped structure. Sturges created a story that was depressing but tidy (prologue, carefully framed flashbacks, epilogue). DeSylva, unable to rewrite Morton’s history and apparently reluctant to junk the project, made the story more upbeat but also more untidy. Trapped by Sturges’ design, he re-carved it in a uniquely peculiar shape.

Sturges’ bold stroke was to switch the two chronological blocks of Morton’s life and to make us sense the injustice of Morton’s fleeting fame. DeSylva wanted to avoid the grim epilogue in the present and end on an upbeat note. But he did retain the split chronology, so that the contrast between obscurity and fame remains. He inadvertently innovated by making the opening credits preview a scene far ahead in the plot, and then letting the ending twist back to it. By playing the title over the parade, the release version shifts us across two moments, and meanings, of greatness: celebrity and self-sacrifice.

Did Buddy set out to be daring? I don’t think so. He faced constrained solutions whichever way he turned, just like us most of the time. More on this matter at the end.

As easy as C-A-C-B-C-B-C

As I mentioned, flashbacks usually sit comfortably in a frame, a well-established present situation that we depart from and return to. The shifts in and out of the past can be eased by various devices, one of which is a voice-over representing the character. The voice-over may be objective, as when a trial witness is testifying, or subjective, representing the “inner voice” of the person remembering what we have in the flashback.

Again, however, a film built out of flashbacks has many options. Coming to direction in the mid-1940s, Joseph L. Mankiewicz was in a position to try his own riffs on current experiments in storytelling.

So, for instance, in House of Strangers (1949), he frames a flashback without a voice-over. The camera coasts up a stairway to a window at night; dissolve to the window in daytime, and pull away to reveal the earlier scene. Our understanding of the time shift is aided by the comparison on the musical track: a phonograph record of a passage from the opera Martha fades out, and in the flashback, the Monetti family patriarch, now alive, is singing it.

Similarly, A Letter to Three Wives (1949) supplies the symmetrical structure in shifting from Deborah to her anxious memories and then back again.

But the voice-over varies from the usual. Instead of hearing her voice asking herself, “Is it Brad?” we hear the voice of Addie Joss, who also narrates the film. The suburban wives’ obsession with their rival, who may have run off with one husband, has allowed her to burrow into each woman’s consciousness. (In addition, her voice merges with the chugging of the ship to create distortions courtesy of Sonovox.)

House of Strangers is built around one long flashback; A Letter to Three Wives gives us three parallel ones. All About Eve yields yet another variant. Three characters at a banquet recall their experiences with Eve, the dazzling young actress to be given an award. There will be several flashbacks following Eve’s career chronologically and skipping from one remembering character to another. Given this plan, Mankiewicz’s long version planned for one moderate experiment and one fairly daring one.

The moderate experiment was to eventually eliminate the visual anchoring of the frames. He had planned to start with very clear bookends around the flashbacks and then gradually discard framing scenes. For instance, after Addison DeWitt’s voice-over introduces the other characters, including Margo and Karen sitting at his table, Karen’s voice-over intervenes. We leave the banquet to flash back to her meeting Eve.

In Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of the film, we then return to the banquet in the standard bookend fashion. Karen looks over at Margo much as Addison had looked at her. We hear Margo’s voice-over, and then her flashback is launched. Mankiewicz planned, in all, three of these base-touching intervals in the banquet. The later flashbacks are simply signaled by voice-overs only, interweaving the memories of Karen, Margo, and Addison as Eve rises in the theatre world. In short, Mankiewicz wanted to replace block flashbacks with “polyphonic” ones, but only after careful preparation.

The more daring experiment, and the one whose loss rankled for years, was the idea of replaying Eve’s famous “applause” monologue. We’re at Margo’s party, and several characters are perched informally on the staircase. Addison and Bill, Eve’s fiancé, have argued about the nature of the theatre. Then Eve launches on a brief but impassioned ode to the joys of acting. Applause amounts to “waves of love coming across the footlights and wrapping you up.” Mankiewicz wanted this to follow a scene between Karen and Eve in Margo’s bedroom. Introduced by Karen’s voice-over, this scene shows Eve pressing Karen to help her become Margo’s understudy. Following this, Eve’s monologue can be seen as a warm testimony to her dedication to the theatre—a confession that Karen watches dotingly from a higher step.

At this point, Margo enters from the kitchen and confronts Eve before insulting the other guests and flouncing off to bed.

Instead of showing this scene’s aftermath, Mankiewicz wanted to break chronology and skip back to the beginning of the party, with Margo’s voice-over now introducing things. After some scenes showing her efforts to get Eve out of her life, she was to stalk out of the kitchen and hear in the hallway the end of Eve’s monologue.

They [Margo and Lloyd] exit into the dining room. As they open the swinging door, the CAMERA REMAINS in the doorway. Margo and Lloyd walk toward the stairs. In the b.g., Eve is talking to the group.

How much she says is dependent on how long it takes Margo and Lloyd to reach her.

EVE (in the b.g.): Imagine,,, to know, every night, that different hundreds of people love you… They smile, their eyes shine—you’ve pleased them, they want you, you belong. Anything’s worth that.

Just as before, she becomes aware of Margo’s approach with Lloyd. She scrambles to her feet….

MARGO: Don’t get up. And please stop acting as if I were the queen mother.

And as Margo speaks—or before—we FADE OUT.

By following Margo’s efforts to cast Eve out, the effect of hearing part of the monologue is to confirm Margo’s suspicions that Eve’s demure obedience conceals her desire to compete on the stage.

What Mankiewicz wanted, it seems, was to use a replay for a new purpose. In Mildred Pierce and other 1940s films, the replaying of an action fills in missing material, usually with the purpose of dispelling a mystery or providing a surprise. Here the replay contrasts two characters’ reactions: Karen finds Eve’s speech touching, Margo finds it threatening. Most replays enhanced plot, whereas this emphasized characterization (which in turn advanced the plot).

Or might have. Zanuck, as we saw, cut it out. The incisions left some little scars, as you can see from the discontinuities in the final version. Eve, her trance broken, glances up and sets her expression into standard Alert-and-Deferential Eve mode, as if Margo were coming right at her. Then she gets to her feet. All this apparently happens well before Margo rounds the corner of the doorway.

So Zanuck eliminated Mankiewicz’s boldest step. But, in a reciprocal movement, he found Mankiewicz’s flashback anchorings over-cautious. Zanuck’s version simply cut out all the returns to the banquet except for the very last one.

One consequence is to give greater saliency to the final portion of the banquet ceremony, which has been halted, as if by magic, during Addison’s address to us. Other effects of Zanuck’s excisions waft through the whole film. The floating voice-overs that Mankiewicz had painstakingly prepared (according to the Rule of Three) now emerge at the very start. Voices slip in and out of scenes, more or less tied to what each speaker could have known at that point but never given the sharp boundaries of the standard blocked-and-framed flashbacks.

These floating voice-overs point ahead to the freedom our filmmakers have enjoyed since the 1990s. We no longer demand that explanatory voice-overs be anchored in any Now; they can braid together as ongoing commentaries on the action. From Hollywood to Wong Kar-wai, filmmakers take for granted that they can discard bookended narration in the way Zanuck did. Mankiewicz objected to Zanuck’s habit of cutting scenes “from peak to peak to peak.” But the boss, who always liked his movies fast-paced, explained: “I am way ahead of you and so will the audience be.”

The choice cascade

There’s a lot more to be said about these films and filmmakers, and I hope to develop some of those ideas in my book. For now, there are some interesting lessons.

First, in filmmaking, once you’ve made certain choices, others follow and some become forced on you. What historians of technology call “path dependence” comes into play. Just as computers use fundamentally the same QWERTY keyboard that came into being with early typewriters, initial choices about a project set limits to what you can do. A trajectory makes certain outcomes more likely than others, and it’s hard to reverse.

Once Paramount committed to releasing some version of Sturges’ Pain project, DeSylva had to work with the split chronology somehow. But Hollywood tradition demanded an uplifting ending, so one had to be salvaged, even if that meant snipping off the return to the frame story. Similarly, once Mankiewicz commits to presenting Eve’s ascent from the perspective of three outside observers, certain narrational processes didn’t need as much redundancy as he loaded in. Likewise, Mankiewicz’s prized replay didn’t create path dependency. It was a branch off the main line and could, as Zanuck saw, be lopped off.

Second, in a routinized film industry, we ought to expect that conflicting demands and changes of plan will yield not only well-wrought plots and narration, but also partial, fractured, even discordant narrative patterns. Snafus and compromises are part of the process.

Finally, film techniques seem innovative only in relation to the norms of a period. Most of the narrative strategies employed by Sturges, DeSylva, Mankiewicz, and Zanuck would have probably seemed startling in the 1930s. By the 1940s, such experiments seemed fresh but comfortable additions to a growing repertoire of storytelling techniques. The studios’ solutions were feasible because some flexibility had already emerged in handling frame stories and voice-over transitions.

The history of film forms springs from creative choices made by individuals within institutions. Those decisions have consequences, intended or not. Sometimes the producers don’t suffocate new things; sometimes they create them. If only by accident.

Don’t worry, though. I won’t be making such arguments about The Magnificent Ambersons.

Daniel Mainwaring mentions his plans for Out of the Past in Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s, ed. Patrick McGilligan (University of California Press, 1988), 199.

On A Letter to Three Wives, my comparison of Caspary’s adaptation with Mankiewicz’s shooting script was enabled by the Caspary collection at the Wisconsin State Historical Society. Thanks to Mary Huelsbeck and the staff of the SHS for helping me access Caspary’s papers. Mankiewicz’s remarks about the process and Zanuck’s request to delete one wife are quoted from Robert Coughlan, “15 Authors in Search of a Character Named Joseph L. Mankiewicz,” a 1951 Life magazine article available in Joseph Mankiewicz Interviews, ed. Brian Daugh (University Press, of Mississippi Press, 2003), 17. Caspary was inclined toward modular plotting, as is shown in detail in A. B. Emrys’ Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011).

Brian Henderson provides painstaking comparisons among various versions of Sturges’ scripts and the final version of The Great Moment in Four More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (University of California Press, 1995), 241-360. My quotations from Sturges come from James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), pp. 171-172. Another robust biography is Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (University of California Press, 1994). Essential as well is the autobiography Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges, ed. Sandy Sturges (Simon & Schuster, 1990).

Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of All About Eve has never, to my knowledge, been published. It is available on the Internet, God knows how, here. My extract is from p. 74. A screenplay closer to the finished film was published in 1951 by Random House. It is reprinted in More About All About Eve: A Colloquy by Gary Carey with Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Random House, 1972). Mankiewicz’s regrets over Zanuck’s deleting the replay are expressed in Andrew Sarris, “Mankiewicz of the Movies [1970],” in Dauth’s Mankiewicz Interviews, 31. The characterization of Zanuck’s “peak to peak to peak” cutting can be found in Sam Stagg, All About “All About Eve” (St. Martin’s, 2001), 171. Zanuck’s remarks about being ahead of his director’s screenplay are quoted in Mel Gussow, “The Lasting Allure of ‘All About Eve,'” New York Times (1 October 2000), AR13.

Two lively and careful critical studies are Kenneth L. Geist, Pictures Will Talk: The Life and Films of Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Scribners, 1978) and Bernard F. Dick, Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Twayne, 1983). Charyl Bray Lower and R. Barton Palmer’s Joseph L. Mankiewicz (McFarland, 2001) is an indispensable guide to the director’s work and writings about it. Both Sturges and Mankiewicz are discussed with polemical relish in Richard Corliss, Talking Pictures:Screenwriters in the American Cinema (Penguin, 1995).

I’m grateful to Laura Russo and particularly John C. Johnson of the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center of Boston University. Mr. Johnson kindly supplied valuable information about the version of the All About Eve screenplay held in the Bette Davis collection there.

Another case of the suits’ laying down demands to which a director responds creatively involves the final shot in Bill Forsyth’s wonderful Local Hero. Details here.

Finally, this entry is one in a series of spinoffs of my ongoing work on narrative in 1940s and early 1950s Hollywood. A gathering point for related blog entries is here, and a relevant web essay is here. As a coda to these 1940s films, it’s worth noting that in The Barefoot Contessa (1954) Mankiewicz did get to mount a replayed flashback scene, and in the 1960s he prepared a screenplay of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet that would have presented several characters’ perspectives on the central action.

All About Eve.

Screenplaying

Design by Christina King.

DB and Kristin here:

Two years ago DB reported on the gathering in Brussels of the Screenwriting Research Network (here and here). This year, thanks to our colleagues J. J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, our department hosted the conference. Again, it was chock-a-block with stimulating papers. We also introduced our visitors to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which houses thousands of screenplays. It wasn’t all work, either. Participants were spotted lingering at our lakeside terrace or making their way through the cafes and saloons lining State Street. We believe it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all.

Since there were simultaneous sessions, nobody could attend everything, and we can’t run through all the papers we heard. (So do consult the program for more information.) Herewith, some highlights that set us thinking.

In the key of keynote

Larry Gross and Jon Raymond.

The four keynoters encapsulated the conference’s very wide range. In a workshop keynote Jill Nelmes, Editor of the Journal of Screenwriting, offered a historical survey of screenwriting research in all media, with special emphasis on television. The Big Hollywood Movie was covered by Kristin, whose paper, “Extended How?” examined the ways in which directors’ cuts and extended editions handle the multi-part structure she posits as a foundation of contemporary Hollywood. We won’t say more here, since she may turn it into a blog for this site.

Larry Gross had already started off the conference with a bang by taking us to Japan. Larry has written 48 HRS, Streets of Fire, Geronimo, True Crime, and other mainstream studio pictures, as well as television episodes, TV mini-series, and independent films like Prozac Nation and We Don’t Live Here Anymore. He also writes outstanding film criticism for Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and other journals, and he teaches screenwriting at New York University. Scott Macauley’s informative March interview with Larry is at Filmmaker Magazine.

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

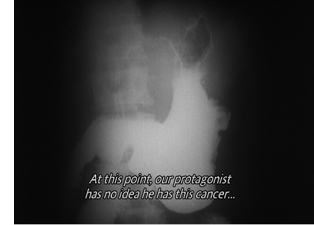

He illustrated his ideas with an in-depth examination of Kurosawa’s Ikiru. He had long thought the film “an official liberal-humanist classic,” until a course with Annette Michelson at NYU showed him that there was a lot to ponder there. Specifically, Kurosawa starts by telling the audience the end of the story: Watanabe will die of cancer. But he doesn’t know that, and neither do all the people he encounters. The strategy denies us a lot of suspense, so to hold our interest Kurosawa must engross us by delineating his relations with his colleagues, with the mothers petitioning for the neighborhood sump to be drained, and with the stray people he meets casually on his night out.

Larry showed how carefully Kurosawa played off the characters’ indifference, misunderstanding, and lack of awareness. In particular, the neighborhood wives display to Watanabe what Maurice Blanchot called “the ignorance and spontaneity of true affection.” Ikiru’s refusal to explain what it means typifies a kind of cinema that asks the audience to share the burden of understanding. “Ikiru understands how a screenplay can be composed with the audience.”

Jon Raymond’s keynote carried things to independent US film. Jon has become famous for a novel (The Half-Life) and short stories (Livability), as well as for his screenplays for Kelly Reichardt’s features. The most recent, the forthcoming Night Moves, is currently in competition at Venice. The teaser title of Jon’s address, “Screenwriting as Earth Art,” turned out to be a reference to the fact that most of his stories take place in the vicinity of his home. He has found satisfaction by composing on familiar ground.

In younger days Jon tried painting and filmmaking; a Public Access feature based on the comic strip Crock turned out to be “a movie best experienced in fast forward.” But he found that writing offered the most creative satisfaction. At the same time, while assisting Todd Haynes on Far from Heaven, he met Kelly Reichardt, who was looking for a property to adapt on a small budget. The result was Old Joy, “a New Age western,” in which two men display the violence latent in the new passive-aggressive masculinity flourishing on the Coast. Jon believes that Reichardt’s handling created a cinematic parallel to the dense intricacy of a short story.

In later collaborations, Jon mapped his patch of Portland in other ways. Seeing the annual migration of workers to Alaskan canneries, and hearing the train whistles wafting through his neighborhood, he created the story that became Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (above). Reichardt began adapting the story to film before he had finished writing it. Similarly, Jon merged the booming housing market of the 2000s and the history of the Oregon Trail into a project that paralleled today’s gentrification with nineteenth-century colonization. Reichardt turned his screenplay into Meek’s Cutoff, a “desert poem” that completed what some have called their Oregon Trilogy. For Jon, the trilogy constitutes an alternative regional history, one that traces the process of “sowing the land with failure, betrayal, and humiliation.”

Plots and no plots

The Adventures of André and Wally B (1984).

More than most areas of filmmaking, screenwriting reminds us of the institutional framework surrounding most creative work cinema. Scholars studying the screenplay are naturally often pursuing the endless revisions, refusals, and rethinks that a film goes through in the preparation phase. It’s easy to see this as a one-versus-one struggle, but in many cases the process takes place within a social environment possessing its own roles and rules.

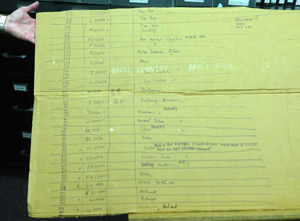

Ian MacDonald offered an excellent example in his study of the work processes behind the UK television soap opera Emmerdale. He proposed that we replace model of industrial film production as an auto factory with that of a carpet factory. Instead of the TV episode being seen as a discrete unit, like a car, it should be conceived as an ongoing fabric woven of many threads. In Emmerdale and other series, the unit of production isn’t the episode but rather the story line. Each episode is sliced out of a much bigger stretch of ongoing patterns. Ian illustrated this with the writers’ planning chart that was mounted on the wall.

The vertical column represents scenes, marked off as episodes. The characters are color-coded cards connected by solid liness that weave their way through the scenes. These waves are the melodies; the scenes are the bar-lines. In each episode, two or three characters are given prominence, while the subordinate ones contribute their harmonies. Ian’s discussion reminded me of how Hong Kong filmmakers did much the same thing in the 1980s: plotting films reel by reel and color-coding certain elements—gags, fights, and chases—to make sure that each reel had its share of attractions. This is the sort of insight into structure that institutional research can yield: Structure is these people’s business.

Other Hollywood studios envy Pixar for to its appealing, carefully structured stories. Richard Neupert showed how that tradition goes back to the earliest years at Pixar. Even in demo films which were made to show off technological innovations, the makers tried to reveal how computer animation, even in its early, simple form, could create engaging tales. At a period when computer animation could only render smooth, simple shapes, the Pixar team found appropriate subject matter, with highly stylized characters in The Adventures of André and Wally B and Luxo, Jr.

Remarkably, these tiny films have balanced “acts.” Each is 80 seconds long and has a key action at exactly 40 seconds in: the entrance of Wally B and the moment when the little Luxo lamp jumps on a ball. Similarly, Red’s Dream‘s parts run 50-100-50 seconds. This care in timing continued with the features: Toy Story’s midpoint comes when Woody finally shifts strategies, realizing he has to work with Buzz. And what about Pixar’s perceived slump in recent years? someone asked during the question session. Neupert pointed out that Pixar’s founders have aged, and there may no longer be quite the sense of excitement and discovery pushing the team to surpass others and themselves.

Sometimes institutional traditions come into conflict. Petr Szczepanik’s talk traced in meticulous detail how screenplay development in Czechoslovakia was altered in the years from 1930 to the 1950s. Czech filmmakers developed their own system of moving from theme and story germ to final screenplay. But with the Communist takeover there came the demand to add the Soviet model of the “literary screenplay,” a detailed specification of scenes, dialogue, and the like. Filmmakers resisted this, preferring the customary and more flexible “technical screenplay” that was largely the province of the director. Petr mentioned new screenwriting trends pioneered by Frank Daniel that gave directors the authority to modify the literary format. By the late 1950s, filmmakers had found ways to make the literary screenplay a less rigid blueprint for filming.

Back in the USSR, the screenwriting institution found even the literary screenplay a difficult basis for mass output. Maria Belodubrovskaya’s talk focused on “plotlessness” as a rallying cry and term of abuse in the 1930s-1940s Soviet film. There were long debates about whether “themes” sufficed to make a film or whether you needed strong plots in the Hollywood vein. Film-policy supervisor Boris Shumyatsky urged the latter course, and the popular success of Chapayev (1934) seemed to support his case. By the late 1930s, though, Shumyatsky was purged and the tide turned against strong plots. Film executives found a concern with plot too “Western” and “cosmopolitan,” and annual film production became based on themes rather than stories. Most provocatively, Masha suggested a lingering influence of Soviet Montage storytelling, which based films on vivid but loosely linked episodes. She illustrated her case with an analysis of Pudovkin’s In the Name of the Motherland (1943), with its diffuse lines of action and sudden reversals and omissions.

Back we go

Scarface (1932).

Naturally, Madison wouldn’t be Madison without strong papers on the history of cinema, and many conference presentations suited the tenor of the joint.

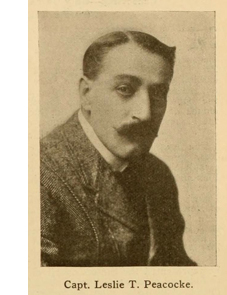

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen surveyed Peacocke’s contribution to the emerging scenario market. Peacocke believed that successful screenwriting couldn’t be taught, but he could give hints about developing original stories, thinking in visual terms, and practical craft maneuvers like snappy names for characters. During the Q & A, Stephen added that a great deal of Peacocke’s rhetoric was aiming to raise his own profile in the industry. In conversation afterward, Stephen praised the Media History Digital Library and Lantern (flagged in an earlier blog) for immensely helping research into early film. Here, for example, is Peacocke’s 216-item dossier on Lantern.

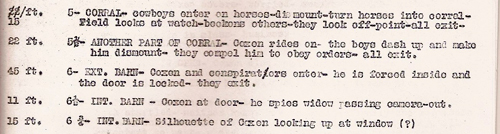

Andrea Comiskey argued that for the same period, we can study scripts and extrapolate craft practices that otherwise go undocumented. Her focus was the disparity between what manuals like Peacocke’s said and what actually got jotted down in working scenarios. Studying several screenplays from the American Film Company of Santa Barbara, she found that the manuals’ recommended stylistic approach was revised in the course of shooting.

The manuals proposed that each scene would be built out of a lengthy single shot (called, confusingly, a “scene”) which could at judicious moments be interrupted by an “insert.” An insert was usually a letter or piece of printed matter read by the characters, but it might also be a detail shot of a prop, hands, or an actor’s face.

In preparing scenarios, the writers assigned numbers to each “scene,” as the manuals recommended. But Andrea found that in the filming, the director and cameraman added shots, breaking down the action into more bits. This was, in effect, a move away from the strict scene/insert method and a shift toward what would become the classical continuity system. To maintain a paper record for the editor, the interpolated shots would be recorded and labeled in fractions. Instead of a straight cut from 6 to 7, the filmmakers might wedge in 6 ½, 6 ¾, and so on. Here’s an extract from Armed Intervention (1913), courtesy Andrea.

Strange as this sounds to us today, it was preferable to renumbering the shots, which could cause confusion. (Is shot 17 the original 17 or the later one?) The fractions kept the footage consistent with the scenario across the production process. So it turns out that (as usual?) filmmakers were a bit ahead of the screenplay gurus, even back in the 1910s.

Lea Jacobs asked a question about the transition from silent to sound film: How did filmmakers manage the pacing of dialogue? Silent movies had great freedom of pacing, while the shift to talkies seemed to many filmmakers to slow things down. Lea’s research indicated that two strategies for speeding things up emerged: creating shorter scenes and shortening dialogue passages within them. She reviewed how these ideas emerged in Hollywood’s own discourse in the 1930s and in certain films. In the first years of sound, scenes were rather long (often because they were derived from stage plays) and speeches were similarly extended. But in the 1931-1932 season, she argued, short scenes and quicker repartee became more common.

She traced the process in three films of Howard Hawks, from the stagy Dawn Patrol (1930) through The Criminal Code (1931), which opens in the new style but then turns to longer sequences, and then to Scarface (1932). The gangster film shifted toward shorter scenes and more laconic dialogue than did other genres, and Scarface displays this in full flower. Tony Camonte’s takeover of the South Side beer trade is presented in six harsh, violent scenes that add up to little more than three minutes. Workers in the sound cinema, it seems, were soon pushing toward that rapid tempo we identify with the 1930s.

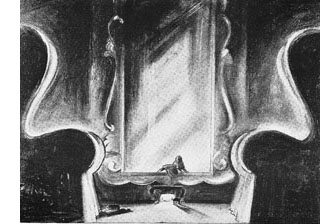

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Spielberg used sketches in addition to a screenplay from the start. Duel, surprisingly enough, was supposed to be shot in a studio, but the director insisted on working on location. The sketches he made for it do not resemble a traditional storyboard but instead are like pictorial maps framed from an extremely high angle. He also plotted out the paths of the vehicles with overhead views of the roads. The storyboards for Jaws were done from the novel at the same time that the script was being written, just as Menzies had done with Gone with the Wind. (The same thing happened with Jurassic Park.) Storyboards were vital, among other things, for telling the crew which of the four versions of the shark would be used. One fake shark had only a right side, another a left, and which one was needed depended on the direction the shark was crossing the screen. The speakers distinguished between the “working” storyboard and the “public” one. The public one is what sometimes get published, but it usually has each image cropped to remove the information about the shot (e.g., who will work on it) noted underneath.

Brad Schauer contributed to a roundtable on the American B film back when The Blog was in its infancy. He has been researching the role of B’s in the industry for many years, and he brought to our event some new ideas about them in the postwar period. His paper, “First-Run and Cut-Rate” showed that there were still plenty of theatres showing double bills in the 1950s and 1960s (DB can confirm it), and the market needed solid, 70-90 minute fillers. One answer was the “programmer,” or the “shaky A” that featured somewhat well-known talent, color, location shooting, and familiar genres (Westerns, swashbucklers, horror, crime, comedy, and science fiction). Shot in half the time of an A, with budgets in the $500,000-$750,000 range, programmers fleshed out double bills and sometimes broke into the A market.

What does this have to do with screenwriting? Brad decided to test whether Kristin’s ideas about four-part structure (here and here) held good with programmers. Looking at several, he came up with a plausible account that films like Battle at Apache Pass and Against All Flags simply compressed the four parts into short chunks, typically running fifteen to twenty minutes. In The Golden Blade, Rock Hudson formulates his goal (revenge) two and a half minutes into the movie.

Too few things happen?

La Pointe Courte (1955).

In most films, Agnes Varda said, “I find that too many things happen.” How can screenplay studies move beyond Hollywood’s jammed dramaturgy to consider the more spacious sort of storytelling we find in “art cinema”?

Colin Burnett offered a general overview of art-cinema norms that is somewhat parallel to our and Janet Staiger’s The Classical Hollywood Cinema. To a great extent, of course, “art films” differ from classically constructed films. They can be more ambiguous, more reflexive, more stylized and at the same time more naturalistic. They often replace a tight causal chain with episodic construction and nuances of characterization. The protagonists may have complex mental states; they may have inconsistent goals, or no goals at all; they may be passive; they may have shifting identities.

Yet Colin argued against claims that art films lack narrative altogether. “Art films offer reduced scene dramaturgy, rarely its complete absence.” They possess structuring devices comparable to Hollywood acts. A film’s large-scale parts may be based on a character’s development, on changes in space or time, or on variations of action and/or reaction. A question was raised as to whether such a broad category as art cinema could be characterized in such ways. Given the enormous range of types of films made in the Hollywood tradition, however, it seems possible that the art cinema could be described in a similar fashion. (For our thoughts on the matter, go here and here.)

A great many art-film strategies can be seen as stemming from modernism in literature and the other arts. As if offering a case study illustrating Colin’s argument, Kelley Conway focused on La Pointe Courte. Varda’s first film is now coming to be considered the earliest New Wave feature. But Varda wasn’t the prototypical New Waver. She wasn’t a man, she wasn’t a cinephile, and she took her inspiration from high art, not popular culture. A professional photographer who loved painting and literature, she brought to this film (made at age 26) a bold awareness of twentieth-century modernism. The result was a striking juxtaposition of stylization and realism, personal drama and community routine. In La Pointe Courte, we might say, neorealism meets the second half of Hiroshima mon amour.

Inspired by Faulkner’s Wild Palms, Varda braided together two stories. While families in a fishing village live their everyday lives, an educated couple work through their marriage problems in a long walk. Remarkably, Varda had not seen Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy. After supplying background on the production process, Kelley focused on matters of performance. She explained how Varda, well aware of Brechtian “distanciation,” made the couple’s dialogue deliberately flat. By contrast, the villagers’ lines, through scripted, were treated more naturalistically. La Pointe Courte emerges as an anomie-drenched demonstration of how little you need to make an engrossing movie.

To script or not to script (or to pretend not to script)

Maidstone (1970).

The SRN embraces research into the absence of a script as well. At one limit is the work of avant-gardists like Stan Brakhage. John Powers’ “A Pony, Not to Be Ridden” discussed how non-narrative filmmakers used paper and pencil to organize their work, much as a poet might make notes on a draft. John’s examples were three films by Brakhage, each developed out of sketches and jottings assembled after shooting but before editing. Unconstrained by any script format, Brakhage had to invent his own version of storyboarding and screenplay notes.

Compilation filmmakers also discover their structure in the process of collecting and sifting material. Documentarist Emile de Antonio, whose collection resides in our WCFTR, had to build his screenplay up after he had assembled some material. “A script won’t be ready,” he remarked, “until the film is finished.” Vance Kepley’s paper showed that In the Year of the Pig was the result of a massive effort of “information management.” De Antonio sought out press clippings, sound recordings, and news footage and then had to create an archive with its own system of labeling, cross-references, and easy access.

De Antonio started with the soundtrack, which was itself a montage of found material, and then created a “paper film,” cutting and pasting vocal passages and descriptions of images. At the limit, he charted his film’s structure with magic-marker notations on large strips of corrugated cardboard, as Vance illustrated.

One panel session took a close look at improvisation in fiction features. Line Langebek and Spencer Parsons gave a lively paper with the innocuous title “Cassavetes’ Screenwriting Practice.” Explaining that Cassavetes did use scripts (“sometimes overwritten”), and he relied on actors to help create them in workshop sessions, they proposed thinking of his work as exemplifying the “spacious screenplay.” Their ten principles characterizing this sort of construction include:

Write with specific actors in mind. Use a “situational” dramaturgy rather than a rise-and-fall one. The work is modeled on free jazz, with moments set aside for specific actors. Even minor actors get their solos. Shoot in sequence, so that emotional development can be modulated across the performances.

Line and Spencer’s precise discussions cast a lot of light on the specific nature of Cassavetes’ creative process and pointed paths for other directors. They added that the spacious screenplay is really for the actors and the director; the financiers should be given something more traditional.

Norman Mailer called Cassavetes’ films “semi-improvised.” He tried to go further, J. J. Murphy explained in “Cinema as Provocation.” Mailer wanted his three films Wild 90, Beyond the Law, and Maidstone to be completely improvised, utterly in the moment. “The moment,” he proclaimed, “is a mystery.” Mailer opposed the “femininity” he claimed to find in Warhol’s films, so he encouraged his male players to indulge their machismo playing gangsters, cops, and aggressive entrepreneurs. J. J., whose book on Warhol stressed the psychodrama component of the films, finds Mailer no less devoted to having his players work out their problems through unrestrained behavior. The climax of Maidstone, in which an enraged Rip Torn begins to strangle Mailer, becomes the logical outcome of Mailer’s needling provocation of his actors. How ya like the mystery of this moment, Norman?

Within the Hollywood industry, improvisation is identified strongly with Robert Altman’s films, but Mark Minnett‘s “Altman Unscripted?” shows another side to his work. Focusing on The Long Goodbye, Mark finds that the film doesn’t vary wildly from the script. The principle plot arcs aren’t changed, although Altman decorates them by letting minor characters inject some novelty. He encouraged the guard who does impressions of Hollywood stars, and he gave latitude to Elliott Gould, whose improvisation elaborates on the issues of trust and bonding that are embedded in the script. Some scenes are condensed or altered, as often happens on any production, but the Altman mystique of freewheeling, anything-goes creativity isn’t borne out by the film. Altman’s characteristic touches are built around what’s “narratively essential,” as laid out in the screenplay.

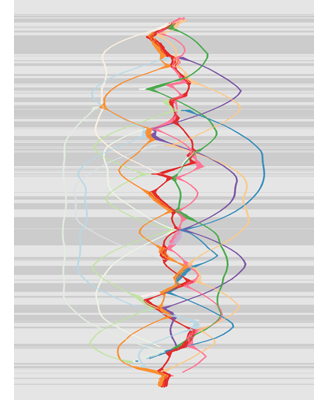

We learned a lot more at the conference than we can cover here. For example, Jule Selbo brought to our attention Sakane Tazuko, a woman screenwriter-director in 1930s Japan. Rosamund Davies explored the ways in which transmedia storytelling could enhance historical dramas. Carmen Sofia Brenes traced out how different senses of verisimilitude in Aristotle’s Poetics might apply to screenwriting. We learned of a planned encyclopedia of screenwriting edited by Paolo Russo and a book on the history of American screenwriting edited by Andy Horton. Not least, there was Eric Hoyt, whose “From Narrative to Nodes” showed how digitized screenplays could be used to graph character action and interaction over time. (A nice moment: When asked if his analytic could be rendered in real time, he clicked a button, and the thing moved.) Once more we’re in the x-y axes of Emmerdale and In the Year of the Pig, but now in cyberspace. Eric’s results on Kasdan’s Grand Canyon appears here on the right, but only as an enigmatic tease; he will be contributing a guest blog here later this fall.

In other words, you should have been here. Next time: October in Potsdam, under the auspices of Kerstin Stutterheim at the Hochshule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf.” DB was at this magnificent facility last year for another event, and we’re sure–to coin a phrase–a hell of a time will be had by all.

Thanks very much to J. J. and Kelley, as well as to Vance Kepley, Mary Huelsbeck, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey of the WCFTR. Special thanks to Erik Gunneson, Mike King, Linda Lucey, Jason Quist, Janice Richard, Peter Sengstock, Michael Trevis, and all the other departmental staff that helped make this conference a big success.

Thanks also to Noah Ollendick, age 12, who asked a smart question.

P.S. 4 Sept: Thanks to Ben Brewster for a correction!

J.J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, conference coordinators.

The enemy next door

Left: Original caption: “Enforced farewell–These Japs wave farewell to relatives as they leave for Manzanar reception camp” (Los Angeles Times, 24 March 1942, p. B). Right: Advertisement for Samurai (Fitchburg [MA] Sentinel, 23 January 1946, p. 5).

DB here:

World War II never goes away, as the current attention given to Hollywood’s relation to Nazi Germany indicates. Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler and Ben Urwand’s The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler trace how the American studios responded to the rise of Nazism and the launching of hostilities. While working on 1940s Hollywood, I ran across two films that deal with another member of the Axis. They remind us of some painful incidents in our history, and they show how inflamed patriotism can burst into racial panic and oppressive public policy.

Call it a mass migration

Soon after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, there arose a fear that saboteurs were at work in America. No solid evidence of this was demonstrated, but the most powerful decision-makers were not in a mood to be tentative. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to demarcate areas from which anyone could be excluded. The Pacific coast was declared such a zone.

In early 1942, the US Army rounded up 110,000 California residents of Japanese ancestry and sent them to what were called concentration camps. (At that point the term simply meant a camp in which enemy populations were “concentrated.”) The evacuees were dispersed to makeshift camps throughout California, as well as in Wyoming, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington state.

Some of the internees were first-generation immigrants, but about 90,000, were citizens. A 1942 government documentary film presents the “relocation” process as necessary for national security, and it shows the evacuees accepting, in a spirit of patriotic submission, the need for such measures. In the film the evacuees effortlessly re-create their communities in their new locations.

Bizarre as it sounds today, the film takes pride in showing that a democracy can create humane concentration camps. But a reading of Richard Lingeman’s Don’t You Know There’s a War On? points up some things the film doesn’t say. The film doesn’t mention that the people rounded up were forced to abandon their homes, businesses, and farms and were permitted to take only what they could carry. (Newspapers often described the relocation as “voluntary.”) The film doesn’t show that the relocation centers were jerry-built, some by the inmates themselves, and were often located in harsh climates. The camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, was subject to sandstorms, blizzards, and subzero temperatures. Nor does the documentary note that the camps were enclosed in barbed wire and watched over by armed guards in security towers. Nor does the documentary show that, because Japanese-American farms produced 40 percent of the California vegetable crop, rival growers pressed for the internment and then snapped up the displaced farmers’ lands at what Lingeman calls “eviction–sale prices.”

The Japanese weren’t unique in undergoing internment; other ethnic groups were subject to investigation, confinement, and relocation. But no other minority was subjected to such a comprehensive roundup. It’s estimated, for example, that about 11,000 German-Americans, innocent or suspected, were interned–a significant violation of their rights, but nothing on the scale of Japanese internment. White people of European extraction, German-Americans had become pillars of American society, and were very numerous. (They were and remain the largest U. S. minority self-identified by descent.) Japanese-Americans, a much tinier and more vulnerable minority, were more easily marked as potentially alien to American values.

Late in 1942, the government began resettling Japanese-American internees outside the camps, spreading them to several states. In December of 1944, partly as a result of a Supreme Court decision the government could not consign “concededly loyal” citizens to camps, authorities declared that the west coast was no longer a war zone. But fears of Japanese espionage didn’t subside, as we can see from a 1945 independent film called Samurai.

Pledged to the God of War

Samurai shows an adopted Japanese boy growing into a traitor and spy. In September 1923, Mr. and Mrs. Morrey rescue Kenkichi from the ruins of the Tokyo earthquake and bring him home to San Francisco. While attending school and assimilating into American society, Kenkichi secretly visits a Buddhist temple where the priest inculcates him in the martial tradition of Bushido, the way of the samurai. Studying to be a doctor, Kenkichi becomes a proficient painter. At the same time, he swears to live and die by the sword, repeating the priest’s pledge that “The God of War presents the key to eternal life!”

The unsuspecting Morreys send Kenkichi to Italy and Germany for his studies, and the priest exhorts him make contacts that will train him as a secret agent. Back in America he begins painting abstract landscapes that conceal military information in coded form–a strange version of that motif of paintings and portraits that winds through 1940s American cinema (The Two Mrs. Carrolls, Suspicion, The Ministry of Fear). When the painting is abstract and nonrepresentational, it usually suggests that the painter may be mad.

Telling his parents that he will be a curator of Asian art, Ken goes to Tokyo and there, at the Black Dragon Society, he decodes his paintings. The Dragon Society’s leader suspects that his visitor is an American spy, but the doubts are dispelled when Kenkichi alters photos from Shanghai to appear that the Japanese are aiding the Chinese. Ken further proves his loyalty by murdering a journalist. He is assigned to the unit of General Sujiyama as a full-fledged spy.

Back at home, Kenkichi tells his priest of his mission, and shows what his reward will be: When the Japanese take over the west coast, he will become governor of California. Explosives are smuggled in, and Japanese farmers (“another link in the chain,” the voice-over narrator tells us) are coordinating domestic spies and saboteurs. The Morreys’ younger son Frank discovers Ken’s plot and tips off the police, while Kenkichi tries to convince the parents that he’s a double agent—before stabbing his father to death. Meanwhile, the invasion has been synchronized with the Pearl Harbor attack. At the climax, the temple priest realizes that his spy network has been arrested and his plan has failed. He commits ritual suicide, but Kenkichi, after brandishing the long samurai sword boldly, doesn’t follow the warrior’s way and instead flees to the beach. There he’s shot down by the police.

Premiered in New York in August 1945, after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Samurai seems to have gotten a very limited release. It’s a cheap production, filled out with montages of newsreel footage, feeble special effects (the back-projection of the Kanto earthquake is especially jarring), and minimalist studio sets. Chinese actors, some with prior Hollywood experience, played the Japanese characters. The device of Kenkichi’s coded paintings seems to be borrowed from illustrative examples of espionage techniques filed as evidence in the 1942-1943 Dies Committee investigation. The We-want-your-white-women motif is made salient in a scene in which Ken and General Sujiyama disport with women captives. Ken toys with a blonde before tripping her.

During the same scene, a Chinese woman fights off the General’s advances before tearing up the Japanese flag. As was typical of the period, the Chinese were presented as courageous and defiant in the face of the Japanese invasion.

Samurai was planned in 1943 under the title “Confessions of a Japanese Spy,” an echo of Warners’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy of 1940. According to the AFI entry, another working title was Orders from Tokyo. Producer Ben Mindenburg supplied the story, and the director Raymond Cannon (who worked intermittently at Fox, Monogram, and elsewhere) is credited with the screenplay. Scenes suggesting rape of the General’s captive women displeased the Production Code Administration. The picture was awarded a PCA seal eventually, so perhaps some portions were omitted.

110,000 people inconvenienced

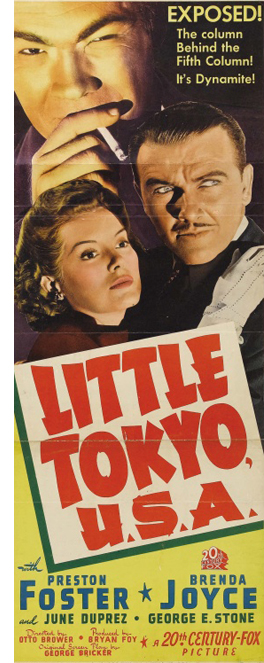

As a minor independent production with small circulation, Samurai can be dismissed as an outlier. It apparently wasn’t reviewed in Variety, but the New York Times called it “an example of opportunistic filmmaking . . . lurid and sensational. At this late hour, a motion picture should do something more than just shout, ‘The Japanese are brutal, scheming beasts.’” Yet three years before, in summer of 1942, Twentieth Century-Fox released a B-film that is hardly less virulent, and the Times, though finding it a “mediocre melodrama,” paid homage to its authenticity in pinpointing “details about incidents of espionage plotted in Los Angeles’s Japanese colony.”

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Steele’s investigation is blocked when he can’t find the radio used by one of the gang to receive instructions from Tokyo. Takimura murders Teru, Hendricks’ Japanese mistress, and Steele is framed for the crime. Steele is in prison when Pearl Harbor is attacked. As “dangerous aliens” are rounded up, he escapes and finds Takimura’s hideout. Mavis, who has been skeptical of Steele’s suspicions, is taken captive by the gang. Takimura finds Steele hiding out in the city morgue. But when they confront Steele he springs a trap of his own: cops burst in and seize the conspirators. The film concludes with Mavis broadcasting the need to stay vigilant.

If Samurai crudely employs techniques of current semidocumentary (voice-over narrator, newsreel footage, some location shooting), Little Tokyo, USA remakes the G-man film into an affair of domestic espionage. We get the familiar frame-ups, the silhouettes and night streets, and the montages of headlines and police dispatches. Given how supple Fox’s B-pictures often were in the 1930s, with the Moto and Chan films and the Sherlock Holmes series, this is a very routine affair. The major Japanese villains are played by Caucasians in Yellowface; even the ubiquitous Abner Biberman (in the poster at right) is recruited to look Japanese.

Unlike Samurai, Little Tokyo, USA indicates that there are loyal Japanese-Americans like Steele’s friend Oshima. Nonetheless, the film buys wholly into the notion of a pervasive Japanese menace. A voice-over prologue presents this as a “film document,” and provides a montage of Japanese men photographing industrial and military sites much like those Kenkichi scouted in Samurai. More subtly, after Pearl Harbor, members of Takimura’s gang are shown putting up signs in their shops claiming to be patriotic citizens—something that many innocent Japanese-Americans did to forestall reprisals. Takimura even establishes a charity that purportedly finances the building of bomber planes.

Beyond spreading a general mistrust, the film aims to justify Japanese-American internment. To do this, it has to show that, as the prologue’s voice-over puts it, before Pearl Harbor Americans had been lulled into a false sense of security by “the mouthing of self-styled patriots.” So we meet several characters who exhibit fatal naivete. Early in the film, Mavis’ broadcast voices her hopes for peaceful negotiation with the Japanese. After Japanese-Americans protest Steele’s investigation, his superior claims:

The Japanese are peaceful, harmless, industrious citizens. They’re loyal too—most of ‘em. ‘Course there may be some rats in the bunch, but that’s nothing to get excited about. I was reading only this morning that 93 percent of the vegetable crop of California is in the control of the Japanese.

Steele replies:

Yeah, I know. They’ve got farms right next to all the airplane factories, and the dams, and the oil-storage concentrations.

He goes on to claim that the farmers lose money, but they’re subsidized by funding from a Tokyo bank.

On the other side, Takimura warns his gang that internment is what he fears most. “Mass evacuation will defeat our operation here.” Fortunately, he remarks confidently, evacuation will be blocked by Japanese civic groups and “certain sympathetic American interests.” This phrase casts anyone who might object as an unwitting tool of the Axis.

A new problem arises when the film must admit that not all 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the coast could be Fifth Columnists. So, like the government documentary, and like the LA Times news photo of grinning men bound for a resettlement camp, Little Tokyo, USA treats the innocent evacuees as accepting internment in a cheerful spirit. It’s proof of their patriotism and their contribution to the war effort. Here are the film’s final scenes, including some documentary footage of relocation and the empty streets of Little Tokyo.

At the denouement Steele punches Takimura (“That’s for Pearl Harbor, you slant-eyed–“) and Steele’s captain abandons his misplaced sympathy by clobbering the “squarehead” Hendricks. In the final scene, Mavis, her eyes now open, uses her broadcast to explain the need for some to sacrifice.

And so in the interests of national safety, all Japanese, whether citizens or not, are being evacuated from strategic military zones on the Pacific Coast. Unfortunately, in time of war the loyal must suffer inconvenience for the disloyal.

As happens today, those calling for sacrifice from others usually give up nothing themselves.

I offer no fancy analysis of these humdrum films. It simply seemed to me that, on the eve of the anniversary of the US bombing of Nagasaki, it would be worth remembering how quickly Americans in a state of war could find enemies among civilians overseas and in our cities here. Among us today there are many who would happily call for some American minority to be rounded up, locked up, sent away, put out of sight somehow. Look around you, as Resnais and Cayrol remind us in Night and Fog, and you will see the eager faces of future jailers.

Thanks to the staff of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium for permitting me to view Samurai. On the role of race in the Pacific War, see John Dower’s War without Mercy. The Dies Committee, later known as the House Un-American Activities Committee, produced a report on Japanese espionage that makes astonishing reading. Here is one passage:

California, with its mild climate and extraordinary agricultural resources, delighted the industrious Japanese. In fact, some of their vernacular newspapers went so far as to call California ”the New Japan.” They were not content to remain day laborers, as had the Chinese, but rapidly acquired their own land, or leased farm land which they frequently worked to depletion. Their women worked alongside the men in the fields for long hours, often with their babies strapped to their backs. Whole towns became Japanese, the native white population gradually leaving areas where the Japanese settled, since competition with them was so difficult if not impossible. They were assertive and aggressive, and did not achieve the reputation for honesty and faithfulness that was enjoyed by the Chinese. California fearfully envisioned the complete control of her agricultural land by the acquisitive Japanese, and became thoroughly aroused. Feeling ran high, but there was little of the violence against the Japanese which had unfortunately marked the agitation for exclusion of the Chinese.

The New York Times review of Samurai appeared on 24 August 1945, p. 7. Variety‘s review of Little Tokyo, U.S.A. appeared in the issue of 8 July 1942, p. 8, and the Times review was published on 7 August 1942, p. 13.

Interestingly, the documentary Japanese Relocation appropriates portions of Virgil Thomson’s scores for Pare Lorentz’s documentary The River (1938), and I think I heard a bit from The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) as well. Presumably the government owned the rights.

Every day brings a fresh example of highly-placed and lunatic bigotry against immigrants to the US. Consider this. Or this.

The photograph below of a Nagasaki in 1946 is from the National Archives; I have taken it from the site About Japan. The quotation at bottom is from Life magazine, 20 August 1945, 27.

Seventy-five hours after the world’s first atomic bombing, an interval marked by President Truman’s demand for unconditional surrender, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, shipbuilding port and industrial center. This bomb was described as an “improved type,” easier to construct and productive of a greater blast. It landed in the middle of Nagasaki’s industries and disemboweled the crowded city. Unlike the Hiroshima bomb, it dug a huge crater, destroying a square mile–30% of the city.

When the bomb went off, a flier on another mission 250 miles away saw a huge ball of fiery yellow erupt. Others, nearer at hand, saw a big mushroom of smoke and dust billow darkly up to 20,000 feet and then the same detached floating head observed at Hiroshima. Twelve hours later Nagasaki was a mass of flame, palled by acrid smoke, its pyre still visible to pilots 200 miles away.