Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Industrial strength

Edith Head costume sketch for To Catch a Thief. From Edith & Oscar: A Costume Exhibit, WCFTR website.

DB here:

Until the 1970s, academics interested in film seldom paid close attention to Hollywood as an industry. Some economists and historians of law were beguiled by the sight of an oligopoly eventually dismantled by Supreme Court decree. But these scholars weren’t particularly interested in the products of the studio system.

People interested in the movies took three positions. The most dogmatic, voiced by one of my grad-school professors, ran this way: “Money doesn’t matter.” That is, art will always triumph over business. If a movie is good, the circumstances of its making are irrelevant. And we study only good movies, so we needn’t consider the business.

Another view acknowledged the importance of the industry but saw it as a vague, overarching force. Creative artists were seduced by it or struggled against it. A powerful director like Chaplin or Hitchcock could control his work to a considerable degree. For the less powerful, the studios (along with censorship agencies) were barriers to creative work. They forced directors to bow to the demands of moguls or a debased public.

The third view was largely celebratory. The studios represented a wondrous confluence of talent at every level, from script to music, and the System mysteriously spun out marvels of drama, comedy, and spectacle: Hollywood as Gollywood. Researchers in this tradition ferreted out as much information as they could about the old days, infusing encyclopedic ambitions with fan enthusiasm.

What came to be called “Wisconsin revisionism” or “the Wisconsin Project” proposed some alternatives.

Auteurist in the archive

Corner of WCFTR office area. Photo: Mary Huelsbeck.

When I came to UW–Madison to teach in 1973, I was an auteurist with a taste both for Hollywood and foreign cinema. I knew relatively little about how the studio system functioned. Its machinations were simply factored out of my consideration. Directors, from Hitchcock and Hawks to Dreyer and Mizoguchi, were what loomed in my consciousness, and I wanted to spend my life studying what they had accomplished.

But contact with students, faculty, and campus personalities at Madison changed my thinking. There was The Velvet Light Trap, a defiantly unofficial magazine that ran special issues on all manner of non-auteur subjects, especially studios, periods, and genres. There were ambitious film societies like Fertile Valley and the Green Lantern, showing offbeat items. There were smart, well-informed grad students. There was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which housed thousands of prints, the center of my lustful thoughts both day and night. The WCFTR also housed vast archives of papers, scripts, photos, and other documents of Hollywood’s golden era.

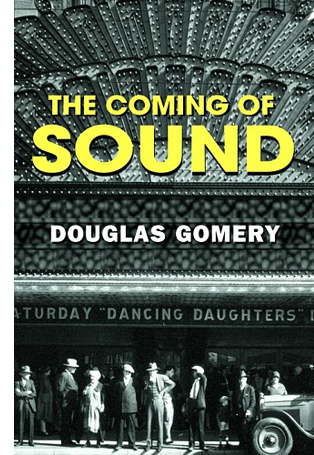

Then there were Professor Tino Balio and Dissertator Douglas Gomery. My conversations with them, both in and out of the office, showed me that there were fruitful questions to be asked about the nature and conduct of the studio system. These two scholars, I think, more or less invented the rigorous historical study of Hollywood as a business enterprise.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Tino, who was presiding over the WCFTR, became another premiere scholar of filmmaking as a business. His books, anthologies, and book series brought immense attention to our collection of material on United Artists, Warner Bros., and RKO. He taught courses in the history of the industry, both survey courses and in-depth seminars. I think I learned more sitting on examination committees with him than I had in many of my grad-school lectures.

Many of the research questions asked by Tino, Doug, and their peers didn’t concern the movies themselves. Some did, though. I remember Cathy Root’s study of stars as strategies of “product differentiation.” More broadly, in the 1970s and early 1980s, some of us suspected that the Hollywood system of production, distribution, and exhibition could affect what then was called “the film text.”

As a result, Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I tried to show how Hollywood’s mode of production did more than simply limit gifted artists or yield pop-culture diversions. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), we tried to understand how the organization of production shaped work routines, technology, adjacent institutions, conceptions of quality, and other factors that did impinge on how the films looked and sounded. Over the years these aspects of filmmaking practice took off on their own, becoming somewhat detached from the industrial conditions that created them. When the studio system faded away in its classic form, the community’s notions of narrative construction, stylistic expression, professional practices, and other factors hung on. The economics changed, but the aesthetics persisted.

Now there are many people working to show how industrial factors interact with filmmakers’ creative choices. Kristin and I have continued these explorations in books and blog entries, extending them to other periods (e.g., the 1910s, the New Hollywood, the 1940s). I like to think that much of our work over the last decades has tried to blend the careful empirical and explanatory work of Tino, Doug, and others with the analysis of art and craft typical of film criticism. We can ask some questions that cut across the over-simple Art/Industry split.

Let a thousand projects bloom (motto, People’s Republic of Madison)

This exercise in autobiography was triggered by some recent events. One is the spiffy new website for the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Under its recent director Michele Hilmes and current director Vance Kepley, the Center has gotten a new jolt of energy. It’s promoting its vast collections in an attractive way and is starting to spotlight some that weren’t well-known. The selections are bolstered by informative program notes by Maria Belodubrovskaya, Booth Wilson, and others.

Certainly the Center’s heart, for historians of Hollywood, is the United Artists collection. This assembles United Artists business records from 1919-1965, scripts and stills from Warner Bros. and RKO, and several thousand film features, shorts, and cartoons, mostly from 1928 to 1948. Then there are the hundreds of named collections, provided by individual donors. The refurbished website calls attention to several of them: the personal and business correspondence of Kirk Douglas (some items now digitized), the Blacklist collection (six of the Hollywood Ten represented), the dazzling array of Edith Head’s costume designs (okay, I’m going a bit Gollywood). There are records for Otto Preminger, Walter Wanger (the basis of Matthew Bernstein’s biography), and Shirley Clarke. The restored Portrait of Jason was discovered in her collection.

Lately, needing information on Guest in the House (1944), I turned to the WCFTR screenplay by Ketti Frings. Her name looks like a Scrabble hand, but she turns out to be a fairly significant screenwriter, contributor to The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), Dark City (1951), and By Love Possessed (1961). Some other day I must get around to prowling in the papers of Vera Caspary, an extraordinary person who is far more than the author of Laura (though I’d be happy just being that).

Beyond Hollywood, the Center holds major collections of Russian cinema and, more recently Taiwanese cinema. And if you must leave cinema behind for theatre, you can investigate Eugene O’Neill, George S. Kaufman, and many other luminaries. In sum, a resource to make you happy for decades.

A career and a conference

The expansion of the Center owes everything to Tino Balio, who served as director in its crucial years. It was he who acquired the UA treasures and many of the named collections. Access to the UA papers enabled him to write the definitive history of the company, but it also created a huge spillover effect: dozens of research projects were nourished by his pursuit of this collection—which came to us at a time when virtually no universities, not even those in LA, were seeking Hollywood corporate records.

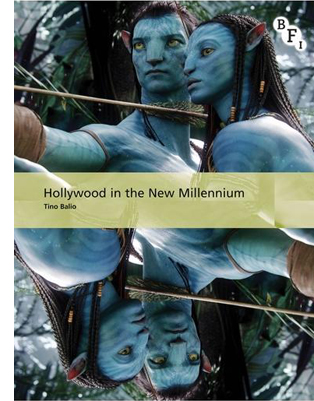

So it’s fitting that, as the WCFTR redesigns its public profile, we see the publication of Tino’s Hollywood in the New Millennium.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

Hollywood in the New Millennium charts the trends that characterize the last fifteen or so years of the American film industry. It surveys financing, production, distribution, exhibition, ancillary markets, and the independent realm. Tino analyzes the ways in which new technologies have changed all these areas, mostly to the benefit of the bottom line, but he also recognizes that technology can undermine the business, especially in the hands of what he calls “the I-want-it-for-free consumer.”

He surveys studio policies, attempts at synergy, and viral marketing. He traces the rise and fall of executives and is especially strong on the emergence of the overriding strategy of the tentpole picture aimed at teenagers and families. Since all studios belonged to entertainment conglomerates, the constant demand was for large-scale profits. For all its financial excesses, the tentpole strategy, Tino argues counterintuively, was an austerity measure.

By the decade’s end, every studio was in the tentpole business. Although the costs of producing and marketing such pictures were enormous, they were the only types that could perform on a global scale and generate significant returns. . . . The sure thing was a good hedge against a dying DVD business, the fragmentation of the audience, and the unknown impact of the internet and social media on Hollywood marketing practices.

In short, you could not ask for a more concise, reliable map of where Hollywood is today. The bibliography is expansive enough to inspire other researchers to dig into both printed and online sources.

Tino has exercised a remarkable influence on two generations of film scholars, but in an almost surreptitious way. Now every film student learns about the structure and conduct of the film industry, but few know that Tino played a pivotal role in making this sort of knowledge central to academic film study. Now in his mid-seventies, Tino has left a peerless legacy of research.

Speaking of research, our campus will be hosting a major conference that includes the WCFTR as a key component. The Screenwriting Research Network International is holding its annual gathering here on 20-22 August. I attended the Brussels SRNI conference two years ago and wrote about it here and here. I think it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all. This is a stimulating bunch, and anyone interested in filmmaking would benefit from attending.

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

The scholars are no less stellar and include Kathryn Millard, Richard Neupert, Jill Nelmes, Steven Maras, Riikka Pelo, Eva Novrup Redvall, Nate Kohn, Ronald Geerts, Andy Horton, Ian Macdonald, and a great many more. Go here for a complete program. You will be impressed.

Needless to say, among the guests are many UW alumni: Patrick Keating, Colin Burnett, Maria Belodubrovskaya (currently a faculty member too), Brad Schauer, Mark Minett, Mary Beth Haralovich, and David Resha. All of them have been steeped in archival research, centrally at WCFTR. Also home-grown are the conference organizers, J. J. Murphy (who blogs here) and Kelley Conway, who is finishing her book on Agnès Varda after immersion in that great lady’s personal archive. Another faculty member, Eric Hoyt, is curator of the remarkably full and free Media History Digital Library; expect him to divulge newer-than-new research sources and methods. I’ll crowd into the act with a paper tied to my 1940s book.

All in all, I see a pleasing continuity from my salad days, through forty years of teaching and viewing and writing, to this moment: a new Balio book, a sparkling shop window for the Center, and new generations of researchers eager to show that The Industry and The Art of Cinema aren’t always that far apart.

Earlier memoirs of Mad City culture in the 1970s-80s are here and here.

For more on the origins of Wisconsin revisionism, see my introduction to Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992) and this entry. We have a blog entry on Tino’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens here.

On the remarkable Vera Caspary (Wisconsin’s own) see not only her fine thrillers Laura and Bedelia but also her Bohemian autobiography The Secrets of Grown-Ups (McGraw-Hill, 1979).

Thanks to Steve Jarchow, CEO of Here Media and Regent Entertainment, for his many years of support of the WCFTR’s activities.

Kelley Conway, Tino Balio, and Lea Jacobs; Madison, WI September 2011.

On the more or less plausible sneakiness of one Preston Sturges

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944).

DB here:

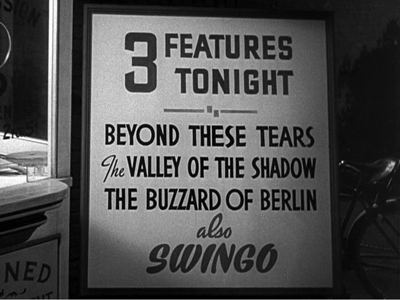

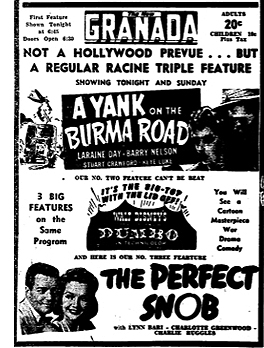

It’s no news that Preston Sturges occasionally mocked the film industry. Exhibit A is Sullivan’s Travels (1941), in which a director of escapist comedies decides to switch to serious social commentary. Sturges’ movie starts with a parody of a violent Hollywood climax that ends with two men plunging to their death. Next we’re told that Sullivan’s previous triumphs are Hey, Hey in the Hay Loft, Ants in Your Plants of 1939, and So Long, Sarong. At a later point we see a somewhat more somber triple feature:

“Swingo” is Sturges’ equivalent of Screeno and other 1930s Bingo-like games designed to lure audiences into theatres.

These gags are pretty straightforward. While working on my book on Hollywood in the 1940s, I found that The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) offers us something less obvious and more peculiar.

Three big fake features

Norval Jones (Eddie Bracken) has taken Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) out on a date. They’ve told her highly combustible father (William Demarest) they’re going to the movies. Actually her plan is to sneak away and celebrate with soldiers about to be sent overseas. She convinces Norval to cover for her and to loan her his car. Trudy is gone all night. Drunk, pregnant, and now married to an elusive Ignatz Ratzkiwatzki, she drives up to find Norval sleeping curled up in the foyer of the movie house. In the two scenes around the Morgan’s Creek Regent theatre, Sturges wedges in some barely noticeable jabs and in-jokes.

Start with what’s playing. Four posters are in the foyer around the box office. One is sitting on an easel turned largely away from us. The other three are mostly blocked by actors, partially framed, or thrown out of focus. But by freezing the film we can make out the titles of these three fakes.

The most visible film is Chaos over Taos, clearly a Paramount release.

You can also make out The Private and the Public, which also bears the Paramount logo. Its poster is behind Norval. Much harder to discern is the title of the third feature on the program, Maggie of the Marines. It’s barely visible for a few frames, glimpsed over Trudy’s right shoulder.

Knowing Sturges’ penchant for playfulness, we can see two of these as parodies of Paramount releases. The Private and the Public seems clearly a reference to The Major and the Minor, directed by Billy Wilder and released in early fall of 1942. Sturges began shooting Morgan’s Creek in October of that year and finished in early 1943, so he would have been well aware of the Wilder film. As an extra fillip, the star of The Private and the Public is listed as Fred McMany, a reference to Paramount star Fred MacMurray.

Then there’s Chaos over Taos. The title is weird enough, relying on an eye-rhyme and being so tough to pronounce that no studio would ever choose it. The star names, Armando Torez and Maria Robles, don’t suggest any Paramount contract players to me, but this was the period when Hispanic and Latino stars began to headline Hollywood movies: Carmen Miranda, Lupé Velez, and Cesar Romero are the most famous. Emphasizing Latin American plots, players, and locations was part of Hollywood’s contribution to Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy. The effort was seen most famously in Disney’s wonderful Saludos Amigos cartoon (1942) but also in a series of Fox musicals with cities named in the titles (Down Argentine Way, That Night in Rio, Week-end in Havana). Chaos over Taos could be Sturges’ dig at a then-current trend in political correctness and at another studio’s production cycle. As for the genre, Chaos/Taos is a flyboy movie and Paramount made several of those—three B-films in 1941 alone (Flying Blind, Forced Landing, and Power Dive, all featuring Richard Arlen).

What then of Maggie of the Marines? It’s likely that Sturges grabbed the title from an October 1942 news story about a dog that wandered into a marine camp in the Panama Canal. Details are at the bottom of today’s entry. We can imagine the sort of heart-warming comedy it might have been, as long as Sturges wasn’t at the helm.

Etc., etc., and etc.

Finally, there’s a matter of exhibition. Just as in Sullivan, the theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek proclaims a very long show: “3 Big Features Tonight, Short Subjects, Newsreel, and Boxo” (another mockery of Screeno). Norval tells Trudy that the whole shebang is scheduled to end at about 1:10.

Unlike the bill of fare in Sullivan’s Travels, the long show at Morgan’s Creek motivates plot action. Trudy uses the pretext of a long triple feature to get her father’s permission to stay out late. But it may not be too much to see in Sturges’ interest in triple features another contemporary reference.

Triple features emerged in the mid-1930s, partly because of high output from the studios and partly because of competition among exhibitors. Dan Goldberg wrote in Variety in 1938:

In a wild scramble for immediate returns without any thought to the outcome, the exhibitors have tried freaks and stunts rather than policy and operation. There have been double features, triple features, bank nite, screeno, keeno, bingo, and giveaways of all kinds, including dishes, flatware, linenware, framed pictures, wall plaques, etc., etc., and etc. There are many houses around here [Chicago] which are getting a 15c and 20c admission and giving away merchandise valued at 11c and more.

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

Triples were evidently less popular with audiences than duals. Perhaps people weren’t willing to spare such a big block of time, or they suspected that the lesser items on the bill weren’t worth watching. Jeff Smith suggests to me that adding a B to an A looks like a bonus, but two or three Bs look like a dumping ground. Interestingly, when Trudy tells Norval she plans to skip out on him, he protests: “I won’t do it! I won’t sit through three features all by myself.” Trudy asks plaintively: “Couldn’t you sleep through a couple of ’em?”

While Sturges was preparing Morgan’s Creek, he might well have noticed some Variety stories tracing a controversy about triple bills in the Midwest. A chain in St. Louis had shifted to this policy, and to retaliate a rival chain began four-hour shows consisting of two features and sixty minutes of shorts. In late 1940, a civic group, the Better Films Council of Greater St. Louis, put pressure on exhibitors to oppose long programs. The Council claimed that such bills were “a physical and mental strain on children and young people,” and that family-appropriate films were sometimes accompanied by “adult” ones. Getting no cooperation from the theatre circuits, the Better Film Council announced in early 1941 that it was going to introduce state legislation to ban triple features. This effort evidently came to nothing.

As if in response to bluenose worries about long programs, Sturges gives the lucky Morgan’s Creek patrons a movie banquet that ends in the wee hours. And ironically, Trudy would have suffered less “physical and mental strain” in the days and weeks thereafter if she’d gone to the movies and not kissed the boys goodbye. The Regent’s absurdly inflated program may be Sturges’ dig at both a contemporary trend and those who fretted about it.

Watching me rake these apparently innocuous frames, you may be asking: Is David going all Room-237 on us? Actually, I see today’s entry as in the spirit of an earlier one, which also has an enigmatic Sturges connection. I’m interested in the moments when Hollywood is talking to itself.

We tend to think that the studios made movies to communicate with the public, and that’s surely true. But we tend to forget that filmmakers were sometimes talking to each other. In the Zanuck-produced Hollywood Cavalcade (1939), a romance of silent-era moviemaking, director Don Ameche turns down Rin-Tin-Tin for a project. The obvious joke is that the pooch became a big star, but how many viewers would appreciate the in-joke that Zanuck launched his career at Warners writing scripts for Rinty? Did the public know that Slim and Steve, the nicknames swapped between Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not, were the ones used by Hawks and his wife? Would ordinary moviegoers catch the reference to Archie Leach in His Girl Friday or notice Jed Leland’s column in the newspaper in The Magnificent Ambersons?

Some would have. Moviegoers of the day were better-educated than the populace in general, and the biggest fans went several times every week. But even if the audience missed these bits, the filmmakers’ peers might not. These movies were made by youngish people who liked to have fun–sometimes at each other’s expense—and nothing is more fun than very esoteric in-jokes.

The problem is that these other examples are highlighted in dialogue, but some of Miracle‘s in-jokes are almost completely buried. They’re more akin to the current vogue for Easter Eggs in sets and props. Unlike the recent instances, though, Sturges’s hints are hard to catch during projection, and he couldn’t have counted on viewers mulling over them frame by frame, as our directors can.

Perhaps he intended to show those posters more fully but had to forego that option during filming or cutting. Or perhaps he included them just for his own amusement–that is, not for the general public, nor even for his peers, but merely for the pleasure of putting in things that only he and his team knew about. If that seems implausible, let me ask: If you could do it, wouldn’t you?

The fourth poster, after some fiddling with the Skew and Perspective tools in PhotoShop, reveals itself as another aerial adventure: Eagle something…. Eagle Blood, maybe? For an example of a drama using real film titles in its movie marquees, see this entry.

On duals and triples, see “Triple Features Seen as Nabes’ Salvation,” Variety (22 January 1935), 3; Dan Goldberg, “Chicago Merry-Go-Round,” Variety 24 October 1938, p. 21; “Now It’s Duals, with Vaudeville, At the Loop Oriental,” Variety (25 January 1939), 5; “Single-Billing Idea Up Again But Practically It’s Still NSG,” Variety (26 August 1942), 13. On the St. Louis controversy, see “Better Film Council Queries St. L. Exhibs on Duals and Triples” Variety (23 October 1940), 21, and “St. Louis Group Seeks to Outlaw Triple Features,” Variety (26 February 1941), 21.

The embedded ad for a triple feature comes from The Racine Journal-Times (11 July 1942), 8.

No need to write me about the most obvious in-joke in Morgan’s Creek: the fact that it incorporates two major characters from The Great McGinty (1940) and doesn’t even bother to credit the actors. Cheeky, this Sturges fellow.

From The Daily Gazette (Berkeley , California, 19 October 1942).

Scoping things out: A new video lecture

A Star Is Born (1954).

DB here:

Cripes! It’s video-lecture fever!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, we do have something new for you.

A video analysis of constructive editing showed up last fall, and a rather long one called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” was posted earlier this year. Now comes one on the aesthetics of early CinemaScope in the US.

It’s a new version of a talk now retired from the lecture circuit and snugly cached on the web. I’m hoping both viewers and filmmakers will be interested in this, particularly in its analyses of staging and composition. The piece makes a more general argument about how new technologies offer both advantages and constraints.

“CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses!” runs about fifty minutes. It’s our first one in HD, so it looks pretty nice on many displays. It could be shown in classes, and I’d be happy if teachers wanted to use it. As with our earlier entries, it’s also available on Vimeo here, where you can leave feedback if you want.

I’m also providing the chapter on Scope from Poetics of Cinema. Think of the lecture as the DVD and the chapter as the accompanying booklet. You can go to the essay if you want to dig deeper into the subject, see other examples of what I’m talking about, or learn the sources for my arguments.

By the way, if you’re interested in the art and craft of widescreen cinema, I’ve posted a web essay on Hong Kong anamorphic here.

As usual, I’m very grateful to my creative tech wranglers Erik Gunneson, who produced the video, and Peter Sengstock. Thanks as well to our web tsarina Meg Hamel.

I’ll have to suspend production of these video lectures for a while, but Kristin and I are hoping to float another novelty soon, perhaps in the next couple of months.

Thanks for everyone who has supported our work through Tweeting, Facebooking, linking, or just telling their friends.

Wild River (1960). From 35mm frame.

“We didn’t have a sense that VERTIGO was special”: Doc Erickson on classic Hollywood

Rear Window (1954); illuminated transparency used to create the lens reflection.

Note: This entry was nearly finished when Roger Ebert died on 4 April. I had intended to send it to him in advance. I think he would want me to post it as I’d planned–just before this year’s Ebertfest.

DB here:

On 17 April, about 1500 people will gather at the Virginia Theatre in Urbana, Illinois, for a celebration of movie love known as Ebertfest. Among Ebertfest’s many guests will be C. O. “Doc” Erickson.

This genial man, who visits Ebertfest each year, is a Hollywood veteran. He was production manager for Alfred Hitchcock, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, Anthony Mann, Roman Polanski, and Ridley Scott. In later years he was associate or executive producer on Chinatown, Urban Cowboy, Popeye, Blade Runner, Looking for Bobby Fischer, Groundhog Day, Kiss the Girls, Windtalkers, and many other projects.

In short, he was an eyewitness to film history. During our visits to Ebertfest Kristin and I have often talked with Doc about his career, and last year I interviewed him for an hour. I thought it was time we set down some of the things we’ve learned. I’ve supplemented Doc’s remarks to us with quotations from Douglas Bell’s 2006 detailed, book-length interview with him.

Setting the scenes

Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Doc began working for Paramount Pictures in December 1944, a year after his graduation from the University of Illinois—Champaign-Urbana. This young man, not yet twenty-one, stepped into the studio that would harbor, across the next few years, The Lost Weekend, The Blue Dahlia, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Unconquered, I Walk Alone, A Foreign Affair, Sorry, Wrong Number, The Big Clock, The Heiress, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, Sunset Boulevard, and several Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Martin and Lewis comedies.

Initially he worked on estimating the budgets for back-lot and set construction. Doc’s unit would try to give the director some leeway. “Ultimately, it wasn’t [a director’s] fault if the set went over budget. . . . We had to try to get enough money in there so that it wasn’t going to go over budget, because then we’d catch hell.” Then Doc and his colleagues would monitor the building of the set to make sure that the specifications were followed and the budget was adhered to.

Doc moved to stage management and supervision, which required him to plan how a production’s sets were arranged in a sound stage. Four or more sets would have to be fitted together, jigsaw-fashion. Doc would try out arrangements by shifting cutout sets on something like a bulletin board, marked with entrances, walls, and power sources. This was called “spotting the sets.” Spotting was much easier in the days of overhead lighting; lighting from the floor, which became more common as the decade went on, posed extra problems.

Once used, the sets might be dismantled, with different departments rescuing what they could use again. A whole set might be saved for another picture (“fold and hold”). B-pictures recycled sets from A pictures. At the other extreme, ornate interior sets might use units drawn from luxurious houses that had been dismantled. From New York mansions came pieces that were shipped to Hollywood and resassembled to create a salon or ballroom.

Paramount’s back lot included big standing sets, including a train station with some cars on the track. “Then, of course, you had pieces of the train in the scene dock, that could be dragged out and assembled on the stage.” A street at the south end of the lot was used for Westerns and featured a mountain that blocked the view of the adjacent RKO studio.

I’ve long been struck by the fact that articles from the classic period seldom talk about the look of sets for ordinary rooms. So I asked: What colors would be found on the sets in black-and-white movies? Doc smiled. “Black and white—or rather, shades of gray.” Sometimes a bit of green would be added. (I’ve read that sometimes snow was painted yellow to make it dazzle.) Pause and think about how hallucinatory it must have looked: actors moving through a three-dimensional black-and-white movie.

The crew was expected to average fifteen to twenty setups per day, at a period when shooting a top-line feature took anywhere from seven to twelve weeks, or even more. The Paramount policy was to press ahead and finish with a set quickly, even if not every shot was taken. Retakes were likely to be close views of the actors and could be picked up later without need for the full set. This flexibility was feasible because most productions were still shot inside the studio walls. Despite the trend toward location shooting in the late 40s, Doc says, “We weren’t off the lot very much.”

The 1940s saw the rise of the hyphenate filmmaker, and this trend was vigorous at Paramount. The studio roster boasted screenwriter-directors Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and several director-producers, including Cecil B. DeMille, Mark Sandrich, Mitchell Leisen, and John Farrow. At Paramount, Doc recalls, “The director was king.” No wonder that one of the most kingly figures of the period wound up there for several years.

A step up

The Misfits (1961).

Doc had moved into the role of assistant unit production manager for Secret of the Incas (1954), directed by Jerry Hopper and starring Charlton Heston and Robert Young. His new job involved managing the day-to-day work of filming as a liaison between the production office and the shoot. A production manager works closely with the assistant director to keep the work on schedule and within budget.

When Hitchcock made his five-picture deal with Paramount and was preparing Rear Window, his assistant director, Herbert Coleman, found that all Paramount’s established production managers had been assigned. Coleman asked Doc to take the job, and Hitchcock approved. Doc’s experience with budget estimating and set supervision made him a natural choice for promotion.

Doc supported Hitchcock on several films, becoming a guest at the director’s home and traveling with him. After finishing Vertigo, Hitchcock shifted to studios that had their own personnel for production management. Hitch offered Doc a place on his television series, but Doc moved on to other Paramount pictures: “I wanted to remain in the feature film world.” He worked in Manhattan with Sidney Lumet on That Kind of Woman (1959). Doc admired Lumet’s meticulous planning of every shot, as well as his insistence on table readings of the whole film before shooting.

Doc then teamed up with John Huston. In 1959 Huston was trying to launch The Man Who Would Be King, and for location scouting he took Doc and other team members on a forty-day trip around the world, paid for by Universal. But that project was put on hold. Doc went on to manage production for The Misfits (1961), Freud (1962), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). On the latter two films, Elizabeth Taylor lobbied for Montgomery Clift—winning on Freud, losing on Reflections. (Brando got the part.)

Knowing my interests, Doc pointed out some of Huston’s directorial touches, including some striking uses of deep space. In the image above, Montgomery Clift’s quarrel with the rodeo judge is framed in the car window while Marilyn Monroe frets that he could have died in his fall from the bull. Doc also thinks that Huston showed adroit staging in the Reflections scene showing Brian Keith wiping lipstick off his mouth while Elizabeth Taylor, in the back seat, uses the rearview mirror to help her repaint her lips.

The movie industry was pushing toward ever more spectacular projects, and Doc sometimes went epic. After a production manager on 55 Days at Peking (1963) quit, the film’s editor, Robert Lawrence, suggested Doc. The film’s direction was credited to Nicholas Ray, but the bulk of the footage was shot by Andrew Marton. There followed Doc’s stint on The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). He recalls Anthony Mann’s excellent eye for composition. The most tangled production was Cleopatra (1963), which had begun shooting in 1960 and was plagued with constant delays. Doc was there for the last eight months of shooting, up to August 1962. He worked under Lewis Merman, the Fox production manager (“one of the greatest human beings I’ve ever known”). Merman was also known as Doc, so the production had both a Big Doc and a Little Doc. It needed even more docs.

Hitch

For my current research I asked Doc a lot about 1940s studio practices, but I couldn’t avoid touching on what everybody asks him about. How was working with Hitchcock? Hitchcock productions have been chronicled in detail by many writers, so I’ll just pick some bits that Doc brought out for me.

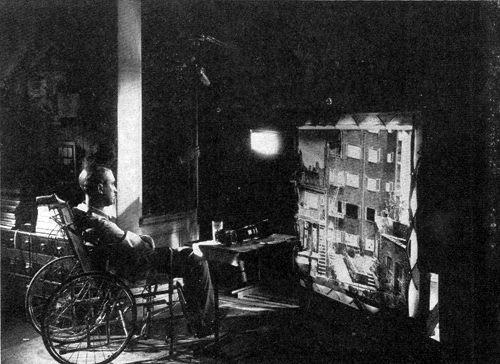

On Rear Window (1954), Doc’s expertise in squeezing sets into a sound stage came in handy. The script demanded that the camera be confined to Scottie’s apartment and that we see only what could be seen from that room. Remarkably, Doc recalls no matte shots being used on the production. The apartment, the courtyard outside, and the apartment building opposite were all installed on a single stage.

Doc was struck by the lighting limitations of this complex and confined set. The color film stock was quite slow, and so illumination levels were very high. He told Douglas Bell:

We had to pour so much light into those apartments, up where Raymond Burr was, it almost put him on fire. It was terrible. Or you would never be able to see him, from where we were shooting. . . . But today it would be nothing, it would be a cinch.

Lens length was also a problem because the camera couldn’t easily simulate the telephoto view of the apartment across the courtyard. Doc found a way to mount the camera outside the window to get a little closer to the opposite building and suggest the enlargement provided by Scottie’s long lens.

Hitchcock had claimed he would need only twenty-four days to shoot Rear Window, but it ran to thirty-six, and its cost was considerably beyond what he had estimated. So great was Hitchcock’s standing in the industry that Paramount didn’t object, knowing the result would be a major picture. Doc was on the set every day. Hitchcock would position the actors and frame the shot, but then return to his chair to watch.

Hitchcock liked Doc and picked him again for To Catch a Thief (1955). For this they left the studio and shot on the Riviera for several weeks—Doc’s first location shoot. After the on-site filming was finished, Hitchcock returned to Paramount for studio scenes and Doc stayed to oversee helicopter shots of the roadways with special-effects specialist Wallace Kelly. The team followed the famous Hitchcock lists and storyboards for such second-unit footage.

Without a break Hitchcock drafted Doc for The Trouble with Harry (1956). Originally to be set in England, the story was transposed to New England. Despite some location work, there were a surprising number of studio exteriors (as are quite obvious to our eyes today). Doc supervised the building of woods on Stage 14, but then scattered around leaves brought in from Vermont and New Hampshire.

Doc was involved in scouting locations in Marrakech and London for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), along with assisting Coleman and Hitchcock in the usual way. Hitchcock clashed with John Michael Hayes on the project, and according to Doc, Steven Derosa’s account of the contretemps in Writing with Hitchcock does justice to the complexity of the situation.

Doc’s memories of the master’s next production, Vertigo, are detailed, but they and other participants’ accounts are chronicled in Dan Auiler’s Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic. What I found surprising were two of Doc’s responses to the project. Doc found that the production went very easily. He thinks that was because he had learned so much about location shooting with the overseas demands of To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much. My second surprise: “We had no sense that Vertigo was special.”

I’m out of step with the world’s critical consensus. I wouldn’t consider Vertigo the best film of all time, or even the best film by Hitchcock. (My votes would go to Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho. All seem to me perfect, endlessly exhilarating pictures.) To a great extent, I think that American Hitchcock never stopped being a 40s director, so I tend to see Vertigo as an uneven mix of plot elements and visual ideas from that wild era. Good as the film is, I think, the expository scenes are rather flatly filmed and lack the flair that Hitchcock brought to such scenes in his earlier films.

But thanks to the undeniable brilliance of many other scenes, along with the revolution of taste promoted by the Cahiers du cinéma critics and the long suppression of the film (making it a sought-after treasure), Vertigo has become a holy grail of obsessional cinema. Its plot premise has fed cinephiles’ fantasies. In the history of taste, a fairly creaky tale of murderous deception has become the ultimate vessel of filmic fascination. One hero’s delusion now epitomizes all movie-made illusion.

Give Doc the last word: “When we finished Vertigo, we never thought of it as being the film that everybody thinks it is today. It’s become bigger than life itself.”

Thanks to Doc Erickson for affable and informative conversations.

Being mostly interested in the Old Hollywood, Kristin and I didn’t question Doc about his work of more recent decades. Those activities are covered in Douglas Bell’s extensive interview, recorded in An Oral History with C. O. Erickson (Los Angeles: Academy of Motion Picture Arts, Margaret Herrick Library, 2006). I’ve drawn much information from this volume. I thank Jenny Romero, Special Collections Department Coordinator at the Herrick Library, for facilitating access to it, and to Kristin for examining it for me during her recent visits to Los Angeles.

For a detailed account of the division of labor on 55 Days at Peking, see Bernard Eisenschitz, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, trans. Tom Milne (Faber, 1993), 378-389. Andrew Marton, who took over the shoot after Nicholas Ray was dismissed, estimated that sixty to sixty-five percent of the finished film was his work. See Andrew Marton Interviewed by Joanne D’Annunzio: A Directors Guild of America Oral History, 413-418.

Herbert Coleman’s book The Hollywood I Knew: A Memoir: 1916-1988, revisits his AD work with Hitchcock in considerable detail, and many of the anecdotes he recounts involve Doc Erickson. For more on the production of Hitchcock’s films, see Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light and Bill Krohn’s Hitchcock at Work.

Without any planning, the last six months or so have been this blog’s Hitchcock period. The entries include items on Dial M for Murder (screened at the Toronto International Film Festival last September), on David O. Selznick, on the first Man Who Knew Too Much, and on the rise of the suspense thriller during the 1940s. On Lumet, for whom Doc also worked, you can see this entry. The production photographs in today’s entry are taken from Arthur S. Gavin, “Rear Window,” American Cinematographer 35, 2 (February 1954), 76-78.

Kristin and Doc Erickson, Ebertfest 2009.