Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick

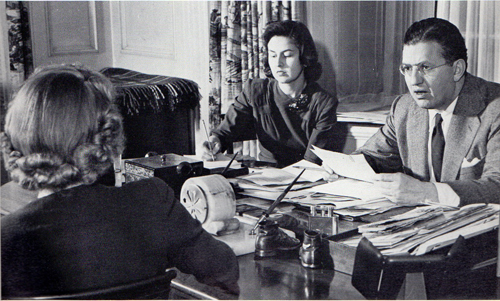

David O. Selznick dictating a memo in 1941. Secretaries are Virginia Olds (back to camera) and Frances Inglis.

DB here:

Tucked neatly within over 4500 archive boxes in Austin, Texas, are tens of thousands of items of information about how the Hollywood studio system worked. The trick is to find the ones you’re looking for…and the ones you didn’t know you should be looking for.

Those archive boxes are housed at the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas. This magnificent research library holds cultural records of inestimable value, from Whitman and Poe manuscripts to the papers of David Foster Wallace. Among the Center’s impressive film collections, the jewel in the crown is the David O. Selznick papers—a vast trove of material related to the career of the man who produced, some would say over-produced, Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, Spellbound, Duel in the Sun, and other classics of the Hollywood system.

Selznick has been studied from many angles, partly because his collection provides exceptionally full accounts of his activities. He kept, it seems, nearly everything, most famously memoranda. While chainsmoking cigarettes, swallowing amphetamines, writing amateur poetry, and revising scripts and visiting sets and critiquing rehearsals and watching rushes and retaking scenes and checking on rivals’ films, Selznick found time to dictate a blizzard of memos.

From his youth he loved to write memos–“I could sell an idea much better in written form than I could verbally”–and he became adept at dictating them. The results were precise, punchy, and often eloquent. Usually signed DOS (the O being a middle initial he bestowed upon himself), these communiqués could be lapidary (a one-liner asking if the cast is protected from sunburn) or epic. After getting Selznick’s dense, eight-page telegram explaining why Since You Went Away’s nearly three hours could not be reduced, a colleague replied: IF I WERE YOU I WOULD MAKE NO FURTHER CUTS IN SYWA. YOU MIGHT TAKE ABOUT TEN MINUTES OUT OF YOUR TELEGRAM.

In his later years Selznick contemplated publishing a collection called Memo Strikes Back. After he died in 1965, his son encouraged film historian Rudy Behlmer to make a compilation. The result, Memo from David O. Selznick (1972), is a superb collage portrait of the man’s personality and creative years. In the 1980s, the Ransom Center acquired the papers that Behlmer worked through, along with physical artifacts, including costumes from GWTW.

Me-mos, they were called by many, since they seemed to reflect the compulsive micromanaging of their creator. Directors and staff smarted under Selznick’s insistence that he control every creative decision. But for those of us coming afterward, Selznick’s criticisms, complaints, demands, reminiscences, agonies of frustration, and I-told-you-sos help us grasp the concrete problems of filmmaking.

Last week I went to Austin hoping to get some information about how Hollywood creators of the 1940s regarded the task of storytelling. DOS delivered as he did on the screen: splashily.

Paper traces

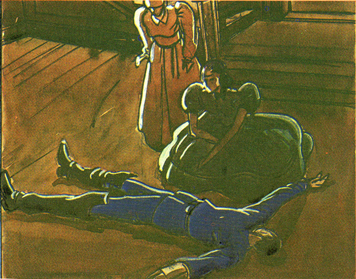

William Cameron Menzies production sketch for Gone with the Wind.

Most commentary on movies stops with the films as we find them. Critics who concentrate on producing interpretations are particularly inclined to play down primary-document research. “We already know,” a famous English critic once told me, “all we need to know.”

In my youth I mostly agreed. Criticism starts with watching and listening closely to what’s happening on the screen. But it doesn’t have to end there. That’s because doing systematic research into film depends on asking questions. And if we’re going beyond a single movie and asking questions about craft, norms, preferred practices, and regulative principles shaping a filmic tradition–in short, questions of film poetics–evidence from practitioners can help a lot.

Hollywood, for instance, has produced a rich array of published materials–interviews, trade coverage, promotion, technical papers–that offer evidence of what filmmakers thought they were doing. You have to read them with a jaundiced eye and be alert for rhetoric, but there’s still a lot to be found in Hollywood’s public presentation of its doings. There’s an even richer lode of unpublished script drafts, production memos, correspondence, transcripts of meetings, court cases, and the like. Mountains of such material remain locked up in studio files. This is what makes the paper collections at major universities, at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy, at the Museum of Modern Art, and at other institutions precious to those of us studying film history.

Collections like these are grist for the perpetual flow of celebrity biographies and accounts of Hollywood as a business. What, though, can they tell us about the history of film form and style?

Like some published material, these items can suggest how aware filmmakers were of their creative choices. When I was teaching, and the class focused on details of framing or cutting, some students were skeptical. “This is reading too much in,” they’d say. “The director couldn’t have intended that!” And it’s true that sometimes things we think were carefully planned came about through accident or sudden inspiration. Still, in other cases a document shows that filmmakers were consciously aiming at fine-grained effects.

Moreover, archive documents can indicate the array of creative options available—the extent to which one artistic choice is preferred over alternatives that wouldn’t work as well. If filmmaking is problem-solving, we learn about the costs and benefits of competing solutions. We gain a better sense of what can and can’t be done within a tradition when we glimpse filmmakers struggling to decide between expressive possibilities.

Yet another benefit of paging through archival documents is the recognition that we can’t neatly separate filmmaking as business from filmaking as an art. We commonly imagine a studio producer ordering a director to take the cheapest option, to trim costs in every way. Surely this happened a lot. Surprisingly often, though, the suits did and still do invest a lot in artistic effects, even innovative ones. When writing our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, we were struck by the power of the idea of the “quality film,” that mixture of novelty, showmanship, and high production values that justifies time and resources. A flamboyant crane shot, a complicated lighting scheme, a gorgeous musical score, flashy special effects—in the Hollywood tradition and others, these are appeals worth paying for, even if not every viewer appreciates them.

Perhaps above all, studying records can call our attention to aspects of the film that your initial impression didn’t pick out. A critic can’t notice everything. Examining collections such as Selznick’s, or those housed in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, have taught me that what appears effortless or perfunctory on the screen can be the product of intense thought, protracted debate, and hours of hard work. Once you re-tune your attention, even minor moments can be worth thinking about, if only because the filmmakers labored patiently over them.

Getting what you pay for

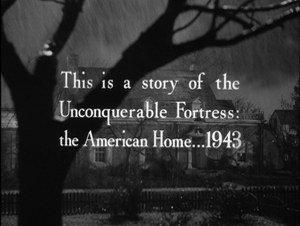

Since You Went Away (1944).

Selnick was a fussbudget on a scale that makes Schulz’s Lucy look laid-back. He sought control over every aspect of the film, from purchase of material through production, post-production, publicity, and distribution. Gone with the Wind’s volcanic success seemed to confirm the wisdom of his endless tracking of every detail. Because that tracking is made explicit, not to say vehement, in his memos and other correspondence, we get glimpses of Hollywood’s artistic strategies large and small.

Start small. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production, I wrote about the “rule of three”–the guideline that presses filmmakers to state important story information three times, preferably with variations (serious/ funny/ pathetic). I gleaned that precept from reading published work, and I could check it by studying the films. Still, further evidence is always welcome, so it’s nice to see a transcript of a story conference during the prolonged rewriting of Portrait of Jennie (1949). The hero, the painter Eben Adams, comes to a coastal town in search of his dream-girl, and DOS suggests:

In every scene he is to ask: “Do you remember a girl named Jennie Appleton?” Use rule of three–two [townfolk] do not remember her–the third one does. . . “Remember her well. . . pretty young thing with dark hair.”

More recently, I’ve been wondering whether studio screenwriters of the 1930s and 1940s were consciously adhering to something like today’s notion of a three-act structure. I’ve found scattered evidence from memos elsewhere that refer to a movie’s “first act” or “last act,” but nothing that indicates a commitment to an overarching three-part layout.

I haven’t found clear-cut evidence in DOS’s papers either, but in another story conference on Jennie, Broadway showman Jed Harris is reported as saying: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” In the finished film, Eben doesn’t search for the portrait, but Harris’s remark indicates that he had some sort of multiple-act structure in the back of his mind. He adds later: “The picture at this point is about 1/3 gone, and from here you have the machinery of trying to stop what is impossible to stop.” Far from definitive evidence, but teasing.

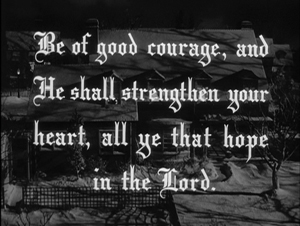

Now consider a medium-size example. Kristin and I have argued that many Hollywood films have a symmetrical opening-and-closing structure, often presented as an epilogue that mirrors the beginning. More recently I suggested that this bookend structure often displays an advance/ retreat pattern. At the start, the camera may move into a space or a character may come toward us; at the end, the camera may retreat and/or the characters may turn away or walk into the distance. On Since You Went Away (1944), Selznick sweated over ways to frame this panorama of the American home front. Early on he decided to start his film with an exterior view of the Hilton family home. This image dissolves to a closer view showing a star in the window, which indicates that a member of the family is in the armed forces.

Eventually Selznick decided to end the film by pulling back from a miniature of the house, with a single camera movement replacing the two unmoving shots that started things off. Anne is joyfully embracing her two daughters; they’re inserted as a matte into the upstairs window.

Selznick considered redoing the opening as a slow camera movement in to the window, but only if the miniature was good enough. Perhaps it wasn’t. And at one point he wanted the final shot to start with the star in the window, at least for purposes of the preview screening, “to parallel that at the beginning of the picture.” Again, that wasn’t accomplished, but his playing with possibilities reflects his tradition’s commitment to symmetrical openings and closings.

It would have been far cheaper simply to have ended the film on the three-shot of the women, shown at the top of this section. But Selznick wanted “a nice rounded feeling” in his epilogue, and he was prepared to pay for it. True, he was exceptionally finicky, but going to a lot of trouble and expense to get this formal rhyme was not unusual in studio practice. The hardheaded film business is willing to invest in vivid, emotionally gripping artistry identified with quality moviemaking.

Stylistic trends

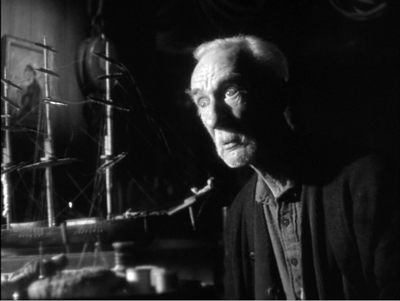

Portrait of Jennie (1949).

In broad terms, it’s fair to say that American studio films of the 1940s display a more self-conscious use of long takes, sustained camera movements, and deep-focus cinematography than we find in other eras. (Actually, it’s a trend we find throughout the world at the time, for reasons that aren’t well understood.) But these new techniques didn’t replace traditional analytical editing. They worked within it. Continuity cutting, established in America in the late 1910s, remained the dominant stylistic framework for filmmakers.

Citizen Kane‘s fixed single-shot scenes in depth were very unusual in cinema of the period. More commonly, deep-focus shots, like moving-camera shots, served as establishing framings or otherwise became part of conventionally edited sequences. This middling or compromise style can be found in dozens of films of the forties, and Selznick seems to have more or less consciously gone along with it.

He worried about what he called “cuttiness,” the tendency to break every scene into brief single shots of the players. Often, he suggested, a well-handled two-shot would work better. He told his editor on Since You Went Away to avoid “the conventional treatment of close-ups and reactions.”

It most definitely is not necessary always to treat every one of our scenes with dead center close-ups, and direct cuts or over-the-shoulder angles, when an intimate scene is played between two people.

He goes on to tell a second-unit director that a scene of a couple in a car could be played in one or two setups, perhaps in a single shot “if we could get an interesting composition on the two of them rather than a dead center two-shot on individuals.”

Selznick saw Hitchcock as an editing-biased director and so after signing him to make Rebecca (1940), he warned him and other members of the team to avoid over-cutting. Again, the preference was for a tight two-shot.

The new scene between the girl and Mrs. Danvers on the arrival at Manderley (Script Scenes 130A, 130N and 131) may be very cutty as described in the script, and perhaps ought to be protected in a close two-shot of ‘I’ [the heroine] and Mrs. Danvers, or some other angle that will keep us from playing it in too many short cuts.

In most cases, however, Selznick gave himself an out by treating faster cutting as an alternative. He consistently wanted coverage, as he indicates immediately for the Rebecca scene just mentioned.

However, I suggest we make the short cuts also, as this may be the best way of playing it after all. If we use the camera to move up to Mrs. Danvers for the finish, which is the way I think it should be used, then perhaps the first shot of her should be retaken also.

As the last sentence indicates, Selznick sometimes opts for camera movement to avoid cuttiness. Perhaps the American Hitchcock’s interest in tracking shots that follow characters, particularly glamorous women, through the set stemmed from Selznick’s belief in the power of occasional camera movements. He notes that a tracking shot introducing Alida Valli in The Paradine Case (1948) is too bumpy, asking why the staff couldn’t manage “something as simple as going up to a woman’s face, and then pulling back from it across a set, without the camera shaking in the manner of early silent pictures.”

Yet these longish takes aren’t to be the dominant stylistic approach. Sustained takes often block off choices in post-production. Producers, then and now, want coverage, and you didn’t have to be a micromanager like Selznick to want your directors to give you options for rebuilding scenes in the cutting room. We see this when Selznick objects to John Cromwell’s playing entire scenes in lengthy shots.

This is of course nonsense, since as often as not an incomplete take is better than the identical portion of a complete take. . . . It seems folly to spend hours getting a complete scene instead of just picking up those sections of the beginning or middle or end that have been fluffed.

Some directors resisted by shooting long takes without coverage. Hitchcock did this in one sequence of The Paradine Case and then promoted this “three and a half-minute take” to the Hollywood community, perhaps to make it harder for Selznick to change it. Nonetheless, Selznick cut the scene up. Once freed from Selznick, of course, Hitchcock was able to pursue the long-take option to extremes with Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949).

Despite wanting flexibility in editing, producers can be seduced by the prospect of “pre-cutting” a film–planning the shots so exactly that the film can be “pre-visualized.” The director can thus avoid taking shots that won’t be used. Selznick was proud of William Cameron Menzies’ precise production planning on Gone with the Wind, and this made him believe in the power of the storyboard. When he rewrote a script, which was often, he was inclined to have artists immediately prepare fresh drawings of sets and shots.

Hitchcock had promoted himself as someone who drafted a film on paper so thoroughly that shooting became efficient and predictable. Selznick was therefore startled when Hitchcock proposed a long shooting schedule for Rebecca. “In view of the many speeches he has made to me about how he pre-cuts a script, so as to shoot only necessary angles, it is a mystery to me as to how he could spend even 42 days.”

During shooting, DOS became furious with the pace of production, declaring Hitchcock “the slowest director we have had.” Hitchcock, he believed, was spending more time getting his few angles than directors who shot in normal fashion. Yet Selznick remained susceptible to the dream of pre-cutting. Some years later, he predicted that Since You Went Away wouldn’t take much time in the editing room because the scenes “will be camera-cut to an extra-ordinary degree, and putting it together should take no time at all.” The film’s editing occupied several months.

Selznick, then, was attracted to current trends of longish takes and the fluid camera, but like nearly all his peers he saw these as subordinate to the overarching demands of analytical editing, whether through traditional protection coverage or through “pre-cutting.” Something similar seems to have governed his interest in depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Peppered throughout the memos I examined are his concern for “foreground pieces,” props that can enliven a shot. A miniature sailing ship in Portrait of Jennie, he suggests, is too big for its placement in the shots as taken. “It would have been a far better foreground piece for another angle.” So it became such a piece, as the still surmounting this section indicates.

Of Since You Went Away DOS notes:

I think that lately we have been overlooking chances for good foreground and background planes in our set-ups. I don’t want to over-do this but of a lot of our shots could be much more interesting in this regard.

In particular he emphasizes the bronzed baby shoes introduced in the film’s opening, as the camera glides through the Hilton family parlor picking up traces of the departed father. A later scene, in which Anne writes a letter to her husband Tim, seemed the ideal chance to re-use that prop. “Photographically, I thought it would be much more interesting with the shadow of the shoes, or using the shoes as foreground pieces.” This composition, if it was shot, didn’t appear in the final film, but it shows once again that filmmakers can be aware of broader trends of their period, and that they’re willing to go to considerable trouble to join them.

A striking example of the insistence on participating in the deep-focus trend appears in the files around Spellbound. After arriving in America, Hitchcock occasionally produced some big-foreground depth images, as below in Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and in Notorious (1946).

Such compositions were rare in most films Hitchcock did under Selznick, but in Spellbound Selznick realized the value of keeping up-to-date. The most famous big foreground in the film (and in all Hitch’s work) is seen at the climax, when Dr. Murchison trains his revolver on Constance as she edges out of his office.

This bizarre shot is somewhat anticipated by a less aggressive setup. Constance hears over the radio that the police have tracked J. B. to Manhattan, and she goes into the next room to pack to follow him. The action is handled in a canonical post-Kane composition.

The production records make me wonder whether this shot (presumably using a larger-than-life clock and radio) was filmed under Hitchcock’s supervision. It may have replaced an even more complex shot that cinematographer George Barnes objected to. (I’m still gathering information on this.) In any event, Selznick realized that a minor transitional scene could be dynamized by a flamboyant, difficult-to-achieve image: a throwaway mark of quality.

Pendulum swings of innovation

Since You Went Away.

I’ll save other things I found for future work. Let me finish by talking about how Selznick’s “directing at a distance” shows a craftsman’s concern for novelty and pictorial storytelling.

Hitchcock famously shot the Old Bailey scenes of The Paradine Case with several cameras in an immense set. Selznick may have okayed this tactic on this occasion because it would speed up Hitchcock’s schedule. (Selznick had hoped it would take only one day; it took three for principal photography and several more for pick-up inserts.) But both before and after Paradine, Selznick was interested in extending multiple-camera shooting beyond its normal uses.

Multiple-camera coverage of ordinary scenes had a heyday in the early years of sound, but afterward it was usually reserved for unrepeatable action (fires, stunts, cars going off cliffs) or very big scenes. Selznick had deployed several cameras, including the lightweight Eyemos, during the dance at the airplane hangar in Since You Went Away. Like Welles, he also considered using the tactic for ordinary dramatic scenes. He writes in 1947:

I have long felt that sooner or later, probably when economic necessity dictates, this method of shooting will come into vogue, with far more time spent on rehearsal, far less time on shooting, enormous savings and better quality. I know that for years I have been discussing with Hitchcock my feeling that we could take a film of a particular type, thoroughly rehearse it, and shoot it in a week–and this is just what Hitch is planning to do on The Rope [sic].

Selznick anticipated the practice of multiple-camera television production. It’s intriguing to think of Hitchcock taking this idea and simply substituting one camera for many, creating another technical stunt that could be publicized.

DOS was sensitive to conventions and often sought to refresh them. For one back-projected scene of Portrait of Jennie, he advises Dieterle “to avoid the awful-looking, head-on, two-shot process setups and angle camera in different ways: perhaps with lower cameras, one shooting across Adams at Spinney and the other shooting across Spinney at Adams.” This echoes his concern for finding unusual angles on the process arrangement in Since You Went Away‘s driving scene. He likewise encouraged unusual staging, recalling

the love scene between Freddie March and Janet Gaynor in A Star Is Born, the one in which he takes her home the first night, after the kitchen scene, where the entire scene is played on Freddie’s back; and the love scene in Nothing Sacred in the crate after Carole Lombard has fished Freddie March out of the river. Both of these treatments enormously enhanced the value of these scenes, which shot conventionally would not have been necessarily so effective.

In the first instance, the conversation is handled by an unusually prolonged over-the-shoulder shot that doesn’t show March replying to Gaynor. In the second, the romantic dialogue is emphasized by the darkness of the crate and our inability to see either actor clearly.

Yet Selznick worried about becoming too “arty” as well. During the filming of Since You Went Away he confessed:

I feel that I am at least partially responsible for our increasing tendency to play scenes on people’s backs. . . . In Jane’s attack upon the colonel after the breakfast scene, we are on neither one principal nor the other, but on the colonel’s back and Jane’s back . . . In the church scene there has been talk of playing it on the three backs, but I have tried in the script to indicate that we should not do this.

Stark lighting is of course common in 1940s cinema generally, but Selznick favored it in the 1930s as well, in the shots above and more famously in Gone with the Wind. By the 1940s, Since You Went Away and Portrait of Jennie include scenes steeped in rich shadow areas, cast shadows, and silhouettes.

But here, as elsewhere, DOS’s urge for innovation was curbed by anxiety about going too far. In a memo to Cromwell on Since You Went Away, he wrote that “all of us (mostly myself) are overdoing the silhouette business. . . . Let’s from now on all use this silhouette effect very sparingly, and only when it’s absolutely indispensable to our mood.”

Perhaps what I’ve called his middle-of-the road approach was less a balance and more of a pendulum swing between extremes. He could sometimes foreswear the grand, almost monumental look of many scenes and demand something quieter. At the end of the day when Anne’s husband has left for war, she looks at his unmade bed.

She leaps up and wriggles into it, covering her face with the blankets, and starts to cry.

Commentators often fasten on the twin-beds convention as an example of the naive timidity of studio-era Hollywood. Yet every convention offers opportunities for expression. When Anne rises, the sight of one rumpled bed and one pristine one brings home the husband’s absence in a simple, powerful image, and her plunging into it directly conveys her longing to be in his arms.

I’m absolutely positive that this gag will not get over unless we see the two beds in the clear, one made up and one not made up, before she hops into the other bed. I think these two beds constitute good storytelling.

When the hard-bitten Ben Hecht saw Since You Went Away, he cabled Selznick: “It made me cry like a fool.”

You can certainly argue that Selznick the fussbudget was his own worst enemy. His micromanagement raised his budgets and drove away his collaborators. As the production values grew more inflated, it was hard to recoup costs, let alone turn big profits. Ten years after Gone with the Wind premiered, Selznick’s fiefdom lay in ruins. He withdrew from production, millions of dollars in debt. He wrote in a confidential 1948 memo:

In the final analysis it is my fault for two reasons: (1) my production methods; (2) my tolerance through the years of the wastefulness. . . . The most successful series of pictures ever made in the history of the business has produced profits which are perhaps not more than twenty per cent of what they should be.

Ideas matter in any domain, even in studying Hollywood. And not just the ideas of critics, historians, and theorists. The practicing artisans of the studio system had rich ideas about preferred ways to build plots, to shoot and cut scenes, to mix sound and add music. These norms were seldom stated outright. Were Selznick less interfering, less prone to hesitate between alternatives, less obsessed with minute details, we would not know as much about the workings of the system he sought to rule. He distilled into typescript and double carbons many notions that ordinarily went unstated. His plump files teem with ideas about how films were made, and how their creator thought they should affect audiences. Thanks to institutions like the Ransom Center, his work is preserved to enlighten us about filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

I’m very grateful to Emilio Banda and the rest of the staff at the Harry Ransom Center, who helped me during my visit. Thanks also to Steve Wilson, Curator of Film there, for advice. And of course thanks to my family–Diane, Darlene, Kewal, Kamini, Megan, and Sanjeev–who made our trip to Austin so enjoyable.

My quotations come from the memos I examined, as well as from other items in Rudy Behlmer’s Memo from David O. Selznick. I also drew on Ronald Haver’s David O. Selznick’s Hollywood (Knopf, 1980), the initial edition of which is surely the most gorgeous book ever published about the American film industry. Haver’s study is not only spectacularly illustrated but deeply researched, and it, like Behlmer’s, is indispensable for the study of the studio system. The Menzies production sketch is taken from the Haver volume.

No less indispensable is Leonard J. Leff’s Hitchcock & Selznick (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987). After sifting through both the Selznick collection in Austin and the Hitchcock collection at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, Leff produced a detailed account of the two men’s creative work. Hitchcock’s long take in The Paradine Case is promoted in Bart Sheridan, “Three and a Half Minute Take…,” American Cinematographer 27, 9 (September 1948), 304-305, 314.

Paul Ramaeker offers a subtle account of Portrait of Jennie as a “supernatural romantic melodrama” at The Third Meaning.

For more on 1940s stylistic norms, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema, chapter 27, and On the History of Film Style, chapter 6. The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema discusses Hitchcock in relation to trends of the period, concentrating on Rope and long-take options. On Citizen Kane and rationales for deep-focus cinematography, you can go here. I mention a bit about the fashion for the “fluid camera” in 1940s Hollywood in this entry.

William Cameron Menzies served as art director and more for Gone with the Wind, and he and was pressed into service ad hoc for later DOS projects. I think he may have influenced the shadow-drenched style of Since You Went Away and Portrait of Jennie. I wrote about Menzies’ work, and again about deep-space work in 1940s Hollywood, here and here. See also David Cairns’ enlightening essay in The Believer.

Since You Went Away: “I think that Miss Keon had better start preparing a script of retakes and additional scenes. I think we missed a wonderful opportunity in the Christmas scene in not having a shot from the angle of the family, or from the bottom of the stairs, of the Colonel going up the stars with Soda behind him.”

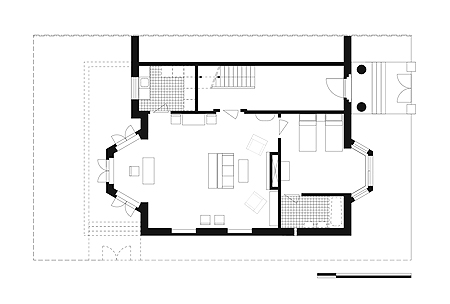

Auteurist on the sound stage

River’s Edge (1987).

DB here:

Last November, Joe Dante brought his brand of manic legerdemain to Madison. This year, his pal and contemporary Tim Hunter visited. Tim talked with us about directing, watched an abundance of movies (from 1930s Wellman classics to Hong Kong gunfests), and oversaw a screening of his 1987 classic River’s Edge. A genial presence and 110% cinephile, Tim was continually stimulating. A blog was a necessity.

Grinding it out

Hunter has made several theatrical features, most famously River’s Edge and The Saint of Fort Washington (1993), but for many years he has also been a free-lance director for top television series, mostly on premium cable. Unlike Dante, whose forte is grotesque comedy and satire, Hunter brings a strong sense of dramatic realism to both movies and television. Over twenty years and more than sixty episodes, he has directed major installments of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Dexter, Deadwood, Law & Order, Cold Case, and Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Apart from efficient craft, he brings to these projects a baby-boomer cinephilia. “I’m an old-school movie brat.” Born in 1947 (about a month before me), he grew up watching classic films. His father was a screenwriter, and in his application interview for Harvard, he won entrance, he thinks, with a rapid-fire analysis of Psycho. As an undergraduate, he ran film societies and made student films. He attended the AFI directors program in 1970 and began teaching film studies at UC-Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, he was writing screenplays. Over the Edge (1979), written with Charlie Haas, was sold to Orion and directed by Jonathan Kaplan. Soon Hunter was able to get backing for Tex (1982), his first directed feature.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a result, the key question—where to put the camera?—has to be settled swiftly. “You need an efficient plan.” Hunter likes to walk the set a day or two before production begins, in order to figure out his setups and actor blocking. The big decision is whether to used a fixed camera or a “moving master,” a tracking shot that reveals the players and the setting, but one that can be interrupted by closer views. He argues that performers prefer sustained shots. “The longer you can play it, the better for the actors.”

To sustain the shots, most dialogue scenes are covered by at least two cameras. That way the scene can be played out in something like real time, with each camera yielding a continuous take centered on one actor or another. The two camera takes can then be cut together into shot/ reverse-shot patterns.

You can see the efficiency of this. The “Perception” episode of Revenge (2012) contains about 780 shots in 42 minutes; of these, at least 350 are shots that repeat setups. A similar proportion can be seen in Hunter’s first episode of Twin Peaks from 1990; about half of the shots repeat earlier camera setups. Because of the time pressure, the director must stage the scenes with adequate coverage from two or more angles.

This can lead to a routine, zero-degree style: Little complex staging, more reliance on actors sitting or standing. Shoot master shot, reverse angles, and singles for reaction shots. Why not use long-held two-shots or fuller framings, as we find in classical Hollywood studio films? Breaking up the camera takes permits the editor to control when we see facial reactions, to tighten the rhythm, and to eliminate fluffed lines. Quick intercutting also supplies that pepped-up pace that, TV practitioners believe, keep viewers glued to the screen.

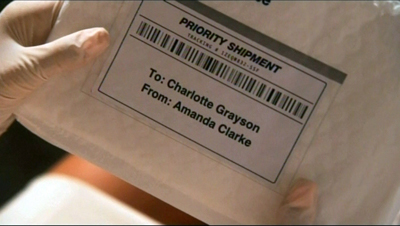

Hunter looks for ways to inject something different, often based on his tastes in classical cinema. For instance, he admires the melodramas of Minnelli and Sirk, so you aren’t surprised to see sudden high or low angles in moments of confrontation. In the “Perception” episode of Revenge, the script gave him a chance for “a Marnie moment.” The heroine Emily has prepared a video that reveals the wealthy Charlotte Grayson’s real parentage. She’s gratified when she sees the maid set the envelope at the foot of the staircase for Charlotte to notice.

Later, overhearing an emotional scene between Charlotte and her father, Emily repents her scheme and tries to retrieve the envelope before Charlotte can find it. Hunter points out that the scene gained suspense when he broke it up into “inserts and moving point-of-view shots.”

The result is a somewhat Hitchcockian byplay, as Emily, startled by the vengeful matriarch Victoria, drops the envelope and tries to keep her from identifying it.

Neatly, Victoria’s face slips into the low-angle view at the very end of the shot, preparing us for her sudden entrance when Emily turns around. And the envelope falling addressee-side down sustains the suspense.

Consciously arty

However much you inject your own emphases, Hunter explained, the director has to assess the visual style of each show and maintain it, so you “tailor your style to the show.” Homicide was 100% handheld, and for that you need a cinematographer who is master of that look. By contrast, Mad Men is more “pictorially precise” and harks back to the studio movies of the 1950s. (Jim Emerson has painstakingly analyzed the felicities of the Mad Men look in several blog entries and video essays.)

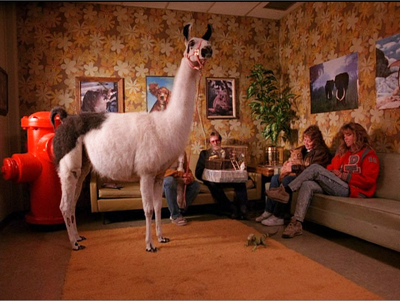

Another pictorially precise show was Twin Peaks, and Hunter’s contribution to the first season (episode four) was one of the most memorable. In that episode we meet Killer Bob’s intimate friend who’s introduced in a shot at once chilling and funny. “Keep your hands where I can see ’em,” snaps Sheriff Harry Truman, and we get this.

At other moments, in an echo of 1940s deep-focus, Hunter uses split-focus diopters to keep foreground and background plane crisp.

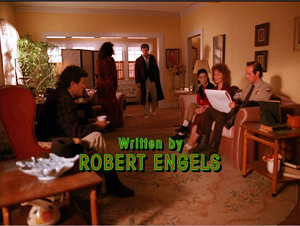

The opening displays the sort of calm assurance that Hunter could bring to a show that was, as he put it, “consciously arty.” A moving master takes us from a photo of the dead Laura to Deputy Andy sketching Killer Bob to Sarah Palmer giving her description; it ends on a framing of Donna, taking it all in uneasily. Donna won’t move or say anything in the scene, but this shot’s ending prepares for both the final shot and her expanding role in the episode’s plot.

In the course of the scene, Hunter supplies closer views anchored by a fixed master setup of the parlor.

When Leland Palmer comes in to say that his wife has had another vision, and when Sarah rises to describe it, we get a long-lens framing, presumably from the B camera aligned with the camera that supplied the master framing.

Sarah’s last gesture in the shot involves extending her palm and recounting her vision of a hand taking out a necklace from under a rock. This strikes Donna with particular force, because she and James have hidden Laura’s necklace the night before. The scene ends with a cut from Sarah to a framing of Donna like that at the end of the first shot. We track in on Donna as she turns away, and the scene ends.

Hunter has talked about getting ideas for this episode from watching Preminger’s Fallen Angel, which handles action in rather confined sets. The wild wall that puts Hunter’s camera behind the sofa allows him to emphasize the proximity of all the characters. Moreover, in this final framing, we can see one virtue of staging the scene for both the static establishing shot and the moving master. In the final moments, Sarah’s gesture can be seen, out of focus, behind Donna and on the frame edge. The surface action of the scene—Truman’s investigation, Sarah’s visions—is counterweighted by the covert action, Donna’s determination to solve the mystery herself.

Stylistic Peaks

Talking with a class in media production, Hunter remarked that story premises—the arresting or puzzling first few scenes—are fairly easy to invent. “Endings are hard.” He stressed that a good story needs a strong climax and resolution. Novels and short stories tolerate diminuendos and offhand closings, but movies need gripping wrapups. Adapting a piece of fiction, Hunter pointed out, may require you to “amp up dramatic tension for a climax.”

As he spoke, I thought about another of his contributions to Twin Peaks, the crucial episode (number 16) in which Leland Palmer, inhabited by Killer Bob, is seized and flung into a holding cell. There Bob-in-Leland rages, seethes, chatters, and laughs demonically. But once Bob abandons him, Leland collapses in agony as he confronts the fact that he has killed his daughter. As if this weren’t dramatic enough, it takes place during a deluge from the building’s fire sprinklers, set off by a cigarette in another room.

Hunter’s direction shows how stark imagery can enhance the actors’ performances. A kind of cleansing spray pours down on Palmer as he confesses, sobbing. Agent Cooper, the Dream Detective, holds him as if cradling a child. There are only four primary setups over about four minutes.

Instead of cutting quickly, Hunter lets the shots play out to emphasize the dialogue and especially the performances: Ray Wise as Leland, terrified that he may be damned, and Kyle MacLachlan as Cooper, whose daffy mysticism finds its reason for being as he guides the dying murderer “toward the light” and a reunion with his dead Laura (top of this section). The scene’s intensity is shaded by the perverse erotic overtones of Leland/Bob’s unholy passion for young girls and the moment when Leland, recalling being seduced by Bob, moans, “He came inside me.”

Minnelli, who set the climax of Some Came Running in a luminous carnival and in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse gave us the image of a man gripping his father in a soaking thunderstorm (above), might well have admired Hunter’s handling. It’s at once tactful (letting the actors act) and flamboyant (the shadows, the torrent of water). In Hunter’s hands Twin Peaks’ New Age quirkiness is cast off and the climax plunges us into pure, traumatic melodrama.

Meaning in the madness

Hunter shot River’s Edge in thirty days at a cost of $1.7 million. Built around Crispin Glover (suddenly hot after Back to the Future) and featuring the young Keanu Reeves and Ione Skye Leitch, it had early buzz. But it alienated the industry. Variety‘s 1986 Montreal festival review called it “an unusually downbeat and depressing youth pic.” By odd coincidence, that review ran alongside a review of Blue Velvet (“a must for buffs and seekers of the latest hot thing”), and both films were shot by Frederick Elmes.

“None of my features made any money,” Hunter says today. But River’s Edge has become a classic of 1980s independent cinema, an anti-John-Hughes teenpic and a sobering look at how kids really live.

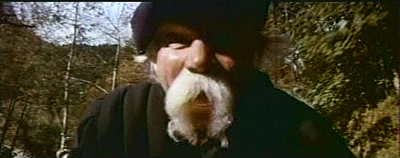

Its unglamorized treatment of high-school sex and drugs goes along with a bleak but nonjudgmental account of a moral blank at the center of kids’ lives. A young man has strangled his girlfriend Jamie, and he takes his pals out to see the body, twice. At first none of them reports the crime, and one, the perpetually hyper Layne, urges everyone to keep quiet. Two in the posse have qualms. Clarissa considers calling the police, and Matt in fact does. In the course of a day, a night, and the following day–a sort of grunge-and-amphetamine American Graffiti time frame—the kids circulate through their neighborhoods settling scores and responding to the threat of an investigation. The one adult in sync with the kids is Feck, a former biker and now drug dealer, who claims to have killed a woman years before.

At first glance the film looks wholly moralizing, with a 60s-era teacher trying to stir his class to political consciousness and a hardened cop squeezing Matt to admit something, anything about the crime. The stoned indifference of the kids to the murder of one of their friends–they don’t cry at her funeral–would seem to indict them as hopeless. But the adults driven to exasperation are hardly role models. The teacher is self-righteous, the cop bullying. Matt’s mother and her live-in boyfriend seem as concerned for their own lives, and their cache of weed, as they are for the kids. And the future? Tim, Matt’s little brother, is the first to spot the body but shrugs it off, and he wantonly drowns his sister’s doll. Eventually Tim will try to kill Matt.

Again, Feck sort of understands. His own drug-driven mania enables him to identify with the kids to whom he gives pot for free. But even he is startled by the hollowness of their lives. He confesses a despairing love for the woman he killed, but he sees no depth in the boy Samson, who strangled Jamie “because she was talking shit.” Feck’s madness is born of passion, Samson’s of annoyance and indifference (“She was all right”). Most of the men treat women, whom Layne calls “evil,” as disposable, and the motif of the dead girl–Jamie, the sister’s doll, and Feck’s inflatable sex doll–brings out the parallels between three generations. This is as bleak a vision of American life as we’ve had in contemporary cinema, and the kids’ amorality, festering in an old foothill community, can’t even be blamed on suburbia.

My friend JJ Murphy has written a superb analysis of River’s Edge, with attention to the craft of Neal Jimenez’s script. Here I want just to show how Hunter, working with more elbow room than in the TV projects, enriches his plot with a tightly shaped, classical style. Two scenes–not climaxes–will help me.

Matt’s brother Tim is playing a video game in the Stop-Go, and the clerk is dimly visible at the counter behind him. Then Samson enters in the background. This concise framing is the scene’s establishing shot, introducing all three of the scene’s characters.

One maxim of filmmaking is: Who is the scene’s anchoring character? Through whose awareness is the viewer experiencing the action? Here, it’s Tim. As Samson goes to the cooler and snaps out a can of beer, Tim watches as he lumbers down the aisle to the front counter.

Samson confronts the clerk, who asks for his identification. He refuses to give it and a quarrel starts, observed by Tim.

Now Hunter uses another classical technique. Like Hitchcock, he gives us something to listen to and something different to watch. As the quarrel at the counter grows more heated offscreen, we see Tim slip to the cooler and swipe two beers.

Actually, Hunter doesn’t show us a close-up of the beers, as we might expect. We see only Tim fumbling and his coat getting baggier. But we know he’s stealing, partly because he checks the security mirror.

Tim makes his way to the front of the store and steps out while the quarrel continues. This introduces a level of suspense, while also characterizing Tim as already a practiced shoplifter.

After a tug-of-war over the beer can, Samson angrily relents and makes his way out. In the parking lot Tim disappears and then reappears, perched on the hood of Samson’s car. The initial front-counter framing has “primed” Samson’s car as an innocuous part of the background in the earlier shot, so that it can be used now. Deep-space staging allows you to quietly set up elements to be activated later in the scene.

Samson leaves the shop scowling and goes to the driver’s seat, where he bends down as if seeing something.

Tidiness: Now we know that Tim’s momentary absence took place because he slipped the beers into Samson’s car. Hunter could have cut in a close view of two beer cans left on the seat, but instead he sustains the shot and lets us see Samson bring one into view, open it, and take a big swig. The beer swiping becomes no big deal, nothing out of the ordinary (as a close-up would have hinted). This sort of swift, small-scale flow of information keeps us waiting for more developments. Those come when Tim peers into the window and says, “Don’t mention it.” He adds, “I saw you this morning.” Samson: “Yeah?” Pause. Tim: “Got any dope?”

The whole scene establishes the tribal amorality and cohesion of the young crew. Tim takes the murder in stride. He swipes the beer not just to do a good turn to his brother’s friend but also in hope of scoring weed.

Samson is at first unresponsive but then, as if to acknowledge he owes the kid, tells him to get in. Tim loads his bike into the back seat. They will go see Feck.

This is the first time we’ve seen the exterior of the Stop-Go. Another film would have given us the conventional establishing gesture, a shot of the front, sign and all, as John pulled up. But in the interests of economy and forging an attachment to Tim, I think, the film starts the scene inside and gives us the exterior only when we need to see it, along with the physical action of loading the bike. Later, we’ll see the Stop-Go from comparable angles and we’ll be able to reorient ourselves.

The use of depth, the careful timing of character movements through the frame, and the overall economy of the sequence stand in contrast to the more heavily cut string of singles we get in “Perception” and even in the Twin Peaks episodes. Comparatively few setups are repeated. There’s no standard shot/ reverse-shot, and no over-the-shoulders. (Imagine how a conventional TV director would have cut up the confrontation with the clerk.) Hunter has constructed his eleven shots so that each one presents a compact body of information, and the shots interlock neatly.

The same conciseness and flexible use of depth can be seen when we return to the Stop-Go during the night scenes. Again, there’s no exterior establishing shot. Matt has come to buy beer at the shop, and there Samson and Feck find him. Hunter could have used the earlier counter setup to save time in shooting, but he recalibrates. A judicious over-the-shoulder framing kicks off this four-shot scene.

Matt is trying to buy a six-pack after hours, and the same blue-vested clerk forbids him. A reverse angle shows Samson coming in, followed by Feck with his sex doll Ellie.

After telling Matt to take the beer, Samson pulls Feck’s revolver. Matt is stunned. In the background, out of focus, Feck is making his way to the cooler.

At Samson’s insistence, Matt grabs the beer (and pays for it). As he edges out of the shot, rack focus to Feck turning to ask the clerk: “Do you have Bud in bottles?” End of scene.

Same setting as the first scene above, and something like the same trigger for conflict: the kids want beer, against the rules. And we have the same geography/ geometry, with the scene organized around the beer cooler, the counter, and the aisle between them. But Hunter has activated the space in a significantly different way. With a close shot he stresses Samson at the moment when he pulls the revolver, and he pays the scene off on a semi-comic note that doesn’t underplay Samson’s casual sociopathy.

The long lenses, the marked rack-focus, and other techniques are more characteristic of post-1960 filmmaking than of the studio years. But the demand for concise visual storytelling, layered with echoes of earlier character gestures, recasting previous dialogues and conflicts through new angles and cutting patterns–these are time-honored strategies. Hunter, like many another movie brat, learned the lessons of classical Hollywood moviemaking. Even in scenes of fairly low dramatic pressure like these, he shows the flexibility and richness of that tradition when it’s put to new uses.

Thanks to Tim Hunter for coming to Madison, Jim Healy for arranging the visit, Eric Hoyt for letting me sit in on his class, and Roch Gersbach for all his assistance.

The Mad Men mystique is engagingly chronicled in Matt Zoller Seitz’s columns in New York Magazine.

The best accounts of television aesthetics are those by Jeremy Butler: Television Style (Routledge, 2010) and Television: Critical Methods and Applications (4th ed., Routledge, 2012).

The review of River’s Edge can be found in Variety (3 Sept. 1986), p. 16. For a little anticipatory buzz, see “Sanford-Pillsbury Readying Pic on Teen Murder for Fall Release,” Variety (2 July 1986), p. 27. Roger Ebert’s review captures the wider response to the film at the time, adding: “This is the best analytical film about a crime since The Onion Field and In Cold Blood.”

Why don’t I write about television more often? The answer is here. For more on how post-1960 directors continued the classic studio tradition, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Dennis Hopper as Feck in River’s Edge.

The wayward charms of Cinerama

From Cinerama Holiday souvenir book, 1955.

DB here:

Two slumbering potential giants stirred in the last months of 1952, and as 1953 got underway the motion picture industry was faced with the greatest upheaval since sound films revolutionized the industry nearly 26 years ago.

Winfield Andrus, “3-D Finding Its Place,” The 1953 Film Daily Yearbook (New York 1953), 147.

Andrus was referring to 3D and to Cinerama, two technical marvels that promised to revive American filmgoing in the postwar era. In the short term, that didn’t happen. 3D died quickly, and Cinerama remained a novelty before expiring in 1962. But eventually 3D became viable, as the last decade has shown. Moreover, Cinerama’s impact was felt throughout the 1950s. Studios competed with it by introducing other widescreen formats, stereophonic sound, and extravagant roadshow productions. Cinerama, people are starting to point out, was a prototype of what Imax has become. Just as we’re now more interested in classic 3D (see my entry on the reissued Dial M for Murder), we ought to take another look at Cinerama in its more or less pure state.

Devoted aficionados like John Harvey of the New Neon Cinema in Dayton have kept Cinerama alive in theatres, and the challenge has been taken up by other venues. One of the most passionate advocates has been David Frohmaier, whose documentary Cinerama Adventure graced our Wisconsin Film Festival some years back. That documentary showed up on the 2008 DVD release of How the West Was Won, and it’s an essential, affectionate introduction to this most ungainly of film formats.

Now Frohmaier has brought us the 1952 film that started it all. This Is Cinerama has just been released by Flicker Alley, one of our most exacting and adventurous DVD publishers. The whole meticulous package–the film itself, presented in Frohmaier’s Smilebox display, along with an abundance of extras—offers a good chance to think about what Cinerama amounted to.

Cinerama had its ups and downs over a decade. Control of the technology and the venues shifted unpredictably, as did the revenues and profits. But I think that Cinerama’s unique accomplishment lies partly in its unintended consequences. Seeking to become the most realistic form of cinema yet known, Cinerama demonstrates how enjoyably un-realistic, even surrealistic, movies can be.

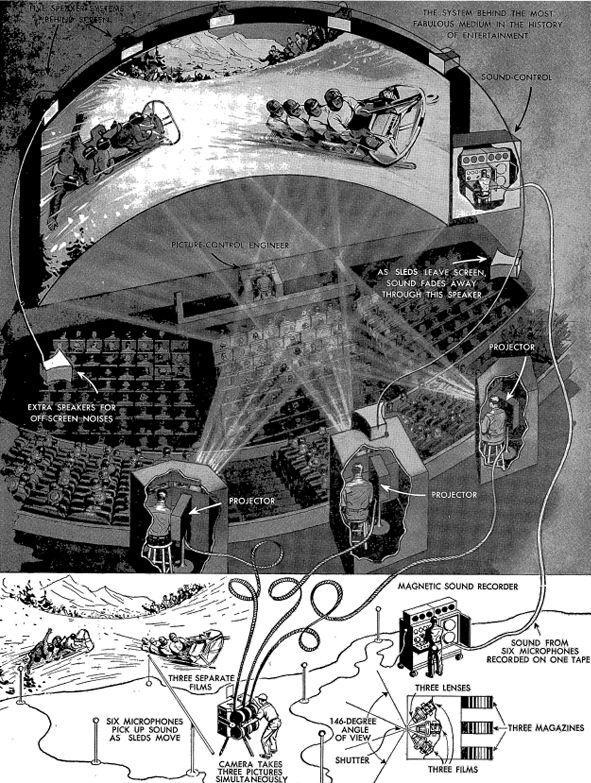

One hell of a demo

When This Is Cinerama opened at the Broadway Theatre in Manhattan on 30 September 1952, it presented itself as the ultimate package of new entertainment technologies. It was of course in color, which was still something of a rarity in motion pictures. It used stereophonic sound, with five speakers behind the screen and two in the auditorium. The screen itself was a wonder: it was seventy-five feet wide and about 23 feet high, bent in a 146-degree arc. That made the display span fifty feet. Later, some screens would be nearly a hundred feet long and over thirty feet high.

All who saw the film felt that this was an immersive experience. The goal, claimed Cinerama’s inventor Fred Waller, was to approximate what our eyes take in, including peripheral vision. Indeed, Waller claimed that our sense of depth in the world and an image depended on peripheral information. Anyone who has been in a wraparound theme-park attraction can attest to the fact that an image stretching to the edges of sight can provide a pretty compelling illusion, especially if the images carry us forward. You can undergo this illusion in Disney’s Circle-Vision 360°.

Cinerama’s colossal screen size and deep curve dictated a new approach to image-making. No standard 35mm frame could fill such a wide display without losing resolution. The scale of the show demanded three projectors, each trained on one-third of the screen. The image became a triptych, with thin overlaps or “blend lines” demarcating the panels. Naturally, all three had to be exactly aligned and kept in strict synchronization. If one film reel lost frames through a mishap, for future shows projectionists snipped the corresponding frames out of the other two reels.

The projectors were initially housed in separate booths, with a projectionist in charge of each. A fourth booth was given to the sound mixer (off to the right side in the above diagram), who oversaw the multiple track playback at each performance. Yet another staff member was in charge of monitoring the whole performance. Interestingly, the projectors were said to be placed level with the screen, in order to avoid any keystoning distortions of the display. But the diagram above, along with the Cinerama displays I’ve seen, position the projectors fairly high in the auditorium.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

To gain resolution, each frame on the film strip used about twice the image area of conventional film. Surprisingly, the image area wasn’t much wider than normal film but it was 1 1/2 times the normal height (that is, 6 perforations high rather than the usual 4). To allow more frame space, the soundtrack was played on a separate magnetic film reel. The resulting images yielded very high resolution.

These sprawling images came from three cameras interlocked into a single bulky unit. The lenses were angled at 48 degrees to one another, turned inward to cross at a precise focal point. The camera lenses, all purpose-made, had a focal length of 27mm–another factor that would yield some striking pictorial effects. All three lenses shared a common shutter and had interlocked diaphragms to ensure comparable exposure. Because flicker would be disturbing on such a wide display, particularly on the edge panels, the film ran at 26 frames per second rather than the usual 24. The aspect ratio varied between 2.6:1 and 2.77:1.

This Is Cinerama was what we’d today call a demo. Lowell Thomas, one of the backers of the process, noted that if they’d told a story with actors, the emphasis would be taken off Cinerama itself, which was “a major event in the history of entertainment.” “The logical thing,” Thomas remarked, “was to make Cinerama the hero.”

The result was a travelogue (a word Thomas hated). After Thomas’ prologue, the film proper opens with the famous ride on a plunging rollercoaster. Then come episodes devoted to the canals of Venice, some church choral music, Scottish pipers, Viennese boy choristers, Spanish dancers, and an excerpt from Aida performed at La Scala. During the intermission Thomas inserts another demo, this time of the surround-sound effects. (We have to remember that stereophonic sound was a big novelty at that point; stereo LPs came later.) The bulk of the second part is spent at the Cypress Gardens leisure park, providing images of handsome men and women at play and climaxing in some exciting water-skiing. This is sort of double product placement–not only promoting the park but also water skis, another Fred Waller invention. The film ends with an awe-inspiring flight crisscrossing America, from New York and the Pentagon to the Golden Gate Bridge, and back to the rugged terrain of the West and Southwest.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

Party like it’s 1952

As a novelty, This Is Cinerama succeeded, running for over two years in New York. The system was installed in big-city theatres around the country. At a time when the average price of a movie ticket was $.46, the high-end seats for a Cinerama feature cost $2.80, or $24.34 in today’s currency. The Cinerama organization produced four more episodic travel-centered pictures: Cinerama Holiday (1955), The Seven Wonders of the World (1956), Search for Paradise (1957), and Cinerama South Sea Adventure (1958). Another picture made in a rival three-panel technology, Windjammer (1958), wound up in Cinerama venues as well. By 1957, Variety announced, the first three releases had grossed $60 million worldwide.

The problem was that on those grosses, profits came to only $6 million. Eighty percent of the box office take was used up in operation of the theatres.Morever, the complexity and cost of a Cinerama system meant that very few venues existed; by 1959, there were about twenty screens in the US and another eight or ten abroad, and not all were operating. In addition, overall US movie attendance was dropping, from about 47 million weekly in 1954 to 32 million in 1959.

New management succeeded in opening many more Cinerama theatres on a franchise basis, but the company needed fresh product as well. A coproduction deal was struck with MGM to use the process on fictional features. The results were The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) and How the West Was Won (London premiere, 1962; US release, 1963). To expand the audience, these films were also released in anamorphic widescreen to non-Cinerama venues.

Both films won large audiences, but they failed to make a profit. Soon the company’s theatres began exhibiting 70mm film releases under the Cinerama brand. The films were shown on curved screens, but with single-lens projection. The first of these releases was It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963); eventually even 2001: A Space Odyssey (1967) would be exhibited in “Cinerama.” In the course of these years, the company was acquired by Pacific Theatres, where it still resides. Classic triptych Cinerama was gone.

I never saw it in its prime.

I did see How the West in its original anamorphic release, and that has stayed with me for a couple of reasons. First, I was moved by it. It’s kitsch in many ways, but there are several exciting and touching scenes. Moreover, even as a squeaky-voiced teen I recognized something genuinely weird about the way it looked. Its imagery haunted me, though I didn’t have ways to understand them. Many years later, writing portions of a book that became The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I couldn’t watch any of the Cinerama travelogues in archives. I had to content myself with watching pink, cropped 16mm anamorphic copies of How the West Was Won. In all, it was very hard to get a sense of what the thing looked like (let alone sounded like).

Not until 2003 did I see both This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won in the three-panel format, during a conference on widescreen cinema held at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England. That experience was wonderful, and it left me wanting to study the films more closely.

Now I can, and you can too. David Strohmaier has devised a transformation that captures the shape of a Cinerama projection. He calls it the Smilebox. The Flicker Alley DVD of This Is Cinerama is in Smilebox, as you see from my Venetian image above. Warner Bros’ 2008 Blu-ray release of How the West Was Won provides both a Smilebox version and a wider-than-CinemaScope letterbox version.

Through painstaking restoration by Greg Kimble and others, the films look clean and bright. Digital cleanup has regularized the color values from panel to panel and nearly eliminated the blend lines. The result conforms to what the makers would surely have preferred–a greater sense of uniform tonality, light, and space across the frame than surviving Cinerama images have.

For anybody interested in the history of American cinema, the Flicker Alley DVD is essential. It provides a long-missing chapter in the development of widescreen filmmaking. This Is Cinerama is a documentary that is also a document of postwar American pride, of film technology, and of the movie business. But I think it represents even more. For the most part neither Smilebox nor digital restoration has removed the peculiarities that, perhaps perversely, fascinate me about this unique format.

Nice big image you got here. Be a shame if anything happened to it.

Cinerama camera in a mock covered wagon for How the West Was Won.

Like any picture-making process, Cinerama captures the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. Unusually in the history of cinema, it does it with a semicircular array of cameras. The images from those cameras are projected on a corresponding semicircular surface, in the hope that they will simulate not only the spatial layout in front of those three lenses but also the way the world looks to us.

Fred Waller thought that his invention provided greater realism, because our vision subtends a horizontal arc wider than that of conventional camera lenses. Fred fell a few degrees short, though. Claiming that we take in about 160 degrees, he thought that 146 degrees was a good approximation, but our visual field is actually a bit wider than 180 degrees. (Without turning our head, we can roll our eyes.) More important, though, is the assumption that a faithful image of the world should try to capture the curvature of the image as it passes through the cornea to the retina. We see a bowed world, many have claimed, so our pictures should present the way things look.

Yet there’s a difference between visual sensation and visual perception. Even if the light from the world hits our photoreceptors in a partial or distorted way, what we see is regular and unified. On our retinas, near things loom large and distant things look tiny, but we’ve evolved to adjust to the distortions in early stages of vision and see things in normal size. A person ten feet away is twice as large on our retina as somebody twenty feet off, but that’s not the way they look. We don’t see our retinal image, any more than we see the wildly misshapen image of the world projected to brain areas. The eye is a part of the brain, and the brain reworks the stimulus–cleans it, enhances it, corrects it, straightens it out, and gives it a stability that isn’t there in the raw input.

For the most part, normal camera lenses approximate the way the world looks to us after our brain has processed visual signals. Most images show straight-edged walls and sidewalks, railroad tracks meeting at the horizon, proportional human beings. When Cinerama or other nonstandard image-making technologies present distortions to our eyes, we take them for what they are: not “what we really see” but rather pictorial displays creating distinct effects of their own.

Hence the irregular appeals of Cinerama. Suppose we’re not interested in seeing the world as it registers on our sensory system. Suppose we’re interested in exploring uncommon pictorial effects. If we suppose all that, we can have the sort of fun watching Cinerama that we get from this 1877 picture by Caillebotte (Paris Street, Rainy Day), a virtuoso reworking of geometric space.

Take image sharpness. In the 2003 Bradford shows, I was overwhelmed by just how precisely distant objects registered. This was partly due to the greater resolution of a bigger image area, partly to the use of wide-angle lenses with breathtaking depth of field in brilliant sunlight. I can’t illustrate some of the most dazzling effects here, including the sight of a very distant bathing beauty racing through a crowd and up to the foreground in the Cypress Garden sequence of This Is Cinerama. But if you have a large home theatre monitor or projected display, you might be able to spot her. Here I’ll just mention how the farthest stretches of the famous roller-coaster stand out crisply, and in big-screen projection, the people in the far distance do too.

Such short-focal-length lenses distort the visual field in predictable ways. For one thing, they make horizontal lines bow upward or downward. For this reason, Cinerama DPs were at pains to keep the horizon near the center of the shot and to avoid or cover contours parallel to the horizon. Linus Rawling’s canoe oar bends disconcertingly in the central panel even before it hits the blend line and shoots off on its own.

Verticals can get distorted as well. On the edges of each panel, human figures can look bulged, pinched, or oddly torqued.

Cinerama’s triptych format complicates perspective effects by welding three wide-angle images together. When presenting built environments, often each panel displays its own distinct vanishing point–sometimes central, sometimes angular, sometimes both. The results recall the Caillebotte picture, all acute angles and avenues flung out to left and right.

One cinematographer tells us that “special sets had to be built with curves and bends to rectify the false perspective inherent in three-camera systems.” But often we get contorted interiors. Dr. Caligari might feel at home in Lowell Thomas’ office.

The blend lines add their own constraints. From a distance, the Golden Gate looks very planar, but as our plane swoops nearer, the horizon remains flat while the bridge develops a couple of kinks.

For staged action, veteran cinematographer William Daniels warned that “We invariably consider the blend lines first, then plot and stage the action to suit the camera setup.” Most obviously, directors had to keep people away from the panel joins. We can see the unfortunate result in this image from This Is Cinerama. The gent on the far right is at once pinched and bulged, and the building in the B and C panels gets the Caillebotte treatment. Worse, a young Venetian man’s head on the blend line undergoes an unfortunate warping.

When a figure moves from panel to panel, the wide-angle distortions combine with the panel edges to create a faceted, almost cubistic space. Here’s the first anomaly I spotted when watching How the West Was Won as a kid in 1963.

As Linus is walking toward Mr. Prescott, James Stewart seems to stride diagonally forward a bit (in the A panel). After he pivots, he grows very large as he starts to walk straight (the B panel). , then stride diagonally into depth (the third panel). Each wide-angle lens makes people swell or shrink as they come to or from the camera, and with the creases supplied by the blend lines, scenes like this become attractively odd. With the panels ironed out, we see people taking strangely roundabout paths to one another.

The effect is even more noticeable in big action scenes, when horizontal movements that are really parallel seem to peel off from one another. During the Indian chase, the wagons are fleeing alongside one another, as a back-projection shows. But the more dynamic angle on the wagon teams creates an image that hits you like a cold shower.

To the audience in front of a curved screen, the movement in the second shot would have looked somewhat (but not entirely, I think) more linear. For us, we see a perspective we’ve never seen before, with wagons diverging from one another but neither getting smaller or larger. And how about the dizzy swerve that the pathway in panel C takes when it reappears in panel A?

The angled-triptych format obliged actors to adjust their performances in counterintuitive ways. “An actor in a side panel,” wrote Daniels, “cannot look directly at one in the center panel when speaking to him, but must cheat a little–direct his eyes a little behind the one in the center.” Here’s an example from The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm that stands out when seen in the flat format. Wilhelm is speaking to Greta from the C panel, but it seems that Laurence Harvey didn’t cheat his body quite enough. He seems to be speaking past her, an effect not helped by the disproportionate size of his body.

This Is Cinerama is obsessed with centering its action, but sometimes the center seems strangely off-kilter. With the water-skiing women shown earlier, the three cameras create a sort of hollow viewing station. Why do the flanking skiiers seem to be moving at angles to the central trio? Why do the ropes of the central skiiers fly off (jaggedly) to one side, rather than expand directly towards us, like train tracks?

As with the wagon teams, you have to imagine diagonal actions as rotated inward to parallel one another during projection. What you see is not what you’d get in the theatre. But also, what you see is something you’ve never seen in a movie before.

Most of these effects are heightened by the inability of the three-eyed monster to record close-ups. Because of the short focal length, the camera unit sat very near the actors: for a shot from the waist up, the central lens was between one-and-a-half and three feet away. Putting the camera so close necessitated lights being attached to the camera unit. But normally close-ups were avoided, so the human figures never dominate their locales. These movies are, more than most, about space–however buckled and bizarre that space might be.

Because of the panels, panning shots were to be avoided, but certain kinds of camera movement forward were welcomed. The signature Cinerama shot is the shot plunging toward the vanishing point–a boat rushing through the water, an aerial view banking toward the horizon. Even though the blend lines made shapes and edges wrinkle, this gigantic, embracing image streaming toward viewers gave a compelling illusion that they were hurtling forward.

The distortions are less visible from a perfect vantage point in a Cinerama auditorium–presumably, as close as you can get. Distortions on the display edges would be minimized by peripheral vision, which isn’t good at registering detail. Presumably some of the curvilinear shapes, like Linus’ oar, and those kinks across the blend lines, would be less egregious if viewed straight on. Watching from the front row in Bradford, I recall seeing these distortions, but they didn’t seem as vivid.

Naturally, not everybody in the auditorium has a perfect vantage point. In the original screenings, people who had sat on the sides complained that movement on the nearest flanking panel seemed to flow upward. Smilebox, which respects the overall geometry of the display, still yields disparities. Linus’ oar still curves, though not as pronouncedly.

My images here, and yours on your home screen, are unavoidably mapping a curved display onto a flat surface, so there will still be anomalies. If you want to try cutting down on them, sit close to the Smilebox display. I prefer to sit back and enjoy their weirdness.

They’re features, not bugs

What about the films themselves? Arguably no great film was made in the format, but all the releases probably have some admirers. I want to end by talking about the two I find most appealing.

Cinerama’s travelogues were episodic, designed to show off features of the process in different filming situations. The two fiction features had to highlight the process and tell a coherent, engaging story. They too tend toward the episodic, but they handle that option in different ways. And stylistically, both work against the official “rules” of the new format.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, an entertaining family film, employs a frame story. The brothers are assigned to write the family history of the local Duke. Jacob, an expert linguist, does his job dutifully, but Wilhelm plays hooky to find and write up fairy tales he hears. His zeal to collect stories leads to the loss of their commissioned manuscript, and he falls ill, during which several fairy-tale characters come to visit him. Eventually Jacob is honored by the Royal Academy, but it’s Wilhelm who gets enduring glory by being swarmed over by hordes of children anxious to hear his latest tale. Within this overarching plot, three of the stories are enacted using various special effects, including puppet animation. Some of these shots appear to have been shot in a non-Cinerama format and “paneled” afterward.)

It’s tempting to ascribe the frame story’s direction to Hollywood veteran Henry Levin and the embedded fantasies to co-director George Pal. To the connoisseur of Cinerama, those fantasy passages offer some delights. If anybody told Pal about the rules for shooting in the format, he ignored them. The fairy tales give us whirling camera movements, bumpy subjective shots, and frequent assaults on the audience in the manner of 3D. During a wild coach ride, the coachman hurls himself to and from the camera. Later, a knight’s bumbling servant slays a dragon in lunging close-up.

You can even take certain passages as sly parodies of the brand. The Woodsman in the first tale has hitched a ride on the back of the coach, and he stoops to look underneath. Cut to his point-of-view: an upside-down version of a signature Cinerama shot.

Whoever directed the frame story scenes, however, was fairly bold too, moving his actors in zigzag patterns more flamboyant than the blocking of How the West Was Won. And instead of the small, high sets recommended for the format, Wonderful World shoots in throne rooms and palace salons that seem to stretch on forever. In smaller sets, like the brothers’ cottage, their friend’s bookshop, and especially the lair of a witch, the compositions take advantage of crannies and oddly angled planes that enhance the exaggerated distances.

As in German Expressionist cinema, the distortions seem to suit an atmosphere of fantasy. There’s even a massive violation of one of the basic rules of Cinerama: avoid tilting the camera. High and low angles were likely to exaggerate any distortions in the panels. Yet Levin, or Pal, or both occasionally throw in expressive angles, most strikingly a low angle showing Wilhelm’s family and friends ascending to his sickroom.