Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone

DB here:

August’s final weekend fizzled. Ray Subers of Box Office Mojo writes:

The Expendables 2 repeated in first place on what was easily the lowest-grossing weekend of 2012 so far: the Top 12 added up to $83.8 million, or 12 percent less than the previous low (Feb. 3-5).

This late-summer slot is usually a problem. Here’s Subers on last year’s situation, which included Hurricane Irene.

The weekend as a whole . . . is poised to be one of the slowest of the year, hurricane or no. . . . This crop of new releases [Columbiana, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, Our Idiot Brother] is modest at best, though Irene has given Hollywood a convenient excuse.

With few exceptions, both winter and summer have stretches which make it hard for new releases to make headway. January through March and mid-August through September are forbidding Dead Zones. Is it a vicious cycle? Do audiences stay away at these times because most releases have little appeal? Or do the distributors treat these months as dumping grounds because people tend to stay away?

Some years back, I pointed out that often these barren months yield some good, unpretentious fruit. This is the realm ruled by our B films–the action pictures, romcoms, modest dramas, and low-budget fantasy and science fiction that give the theatres minimal reasons to stay open. Often the Dead Zone can yield modest, interesting movies that escape the hyperbole that surrounds bigger productions. My example in 2008 was Cloverfield, which actually made decent money in wintry down times. Last year, there were Lone Scherfig’s One Day, Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, and probably others I missed.

I saw only one new release in the 24-26 August window, Premium Rush. It seems to me one of the best mainstream movies I’ve seen this year, and its weak performance ($6 million on the weekend) just shows that you can’t judge by box-office numbers. I found it much more enjoyable as a movie, and more intelligent in its grasp of storytelling and audience uptake, than Marvel’s The Avengers (opening weekend $207 million) and The Dark Knight Rises ($424 million), the two hulks looming over the season.

If Truffaut is right that cinema gives us beautiful people who always find a parking space, Premium Rush is pure cinema. The gallery of characters presents hip youngsters of Benetton gorgeousness (white guy/ African American guy/ Hispanic woman/ Chinese woman/ Indian guy) up against a middle-aged white guy with an ominously overhanging lip that makes him look both stupid and perpetually peeved. Needless to say, Michael Shannon has fun with this. And the couriers always find a place to lock their bikes.

It’s also a real Manhattan movie, which is to say it invokes welcome prototypes: frantic bustle, fast talk, quarrelsome strangers, good cops, bent cops, dumb cops, collisions born of congestion, chance encounters that become significant, violence courtesy of a mafia (Chinese), and moments of casual kindness. We’re all Saroyans when it comes to the Big Apple. We endlessly sentimentalize this city in our movies, and they’re probably the better for it.

But to make a more analytical case that this is a smart, well-put-together movie, I must indulge in spoilers, which are coming right up.

Bike boy

Premium Rush is short: 83 minutes and 49 seconds, not counting credits. That’s also about the length of G-Men, The Ghost Goes West, Holiday, Shopworn Angel, Phantom Lady, The Dark Mirror, Pitfall, The Suspect, Baby Face Nelson, and the 1953 War of the Worlds. I’m not proposing length as a yardstick of value, only noting that our two-hour-plus blockbusters have forgotten what you can do in short compass.

In many B-pictures, both now and then, brevity can encourage you squeeze diverse possibilities out of a simple situation. In Premium Rush, the central situation exemplifies the screenwriter’s old adage: Swamp your protagonist with problems. Here they come fast.

At 5:17 pm, Manhattan bike messenger Wilee is assigned to pick up an envelope from Nima, a Chinese woman who works at Columbia University. He’s immediately pursued by a cop, Robert Monday, who wants what’s in the envelope. At the same time, Wilee and his girlfriend Vanessa, also a messenger, are quarreling because he missed her graduation ceremony. A heavy make is flung Vanessa’s way by Manny, an African American Adonis who’s Wilee’s only rival in virtuoso biking. And at intervals Wilee, who shoots through traffic with suicidal glee, is in the sights of a bulky bike cop. All jammed together we have a free-spirited protagonist who’s quit law school because he loves to ride, a love triangle, a sinister cop, and a mystery: What’s in the envelope? By 7:00 pm all is resolved.

The film displays the classic Hollywood double storyline–romance problems and work problems, intertwined. Still, the plot isn’t as linear as I’ve just implied. I think that the film exemplifies clever ways of working with the four-part structure that Kristin has identified as common in Hollywood features. (That’s discussed here and here and here.) My timings aren’t as exact as I’d like, but I think they’re decent approximations.

Setup (0-ca. 28:00)

After the flash-forward prologue, set at 6:33 pm, and the brief exposition of Wilee’s world view, we see him picking up the envelope at 5:17. It’s addressed to Sister Chen in Chinatown and it must arrive by 7:00.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

Complicating action (ca. 28:00-48:00)

A plot’s second stretch is often a complicating action, something that changes the protagonist’s goals. Originally Wilee wanted to fulfill the delivery; now, with things getting dangerous, he decides not to. He goes back to Columbia to return the envelope to Nima.

At this point we get a flashback explaining that the ticket is a token from a Chinese crime lord, whom Nima has paid with her savings. In the meantime, Monday finds a new stratagem. Instead of trying to catch Wilee, he calls the messenger service and, citing the number on the receipt he has wrested from Nima, he changes the dropoff point. Raj, the dispatcher, gives the order to Manny, Wilee’s rival, and Manny fetches the envelope moments after Wilee has returned it.

We’re at about the midpoint of the film when Nima explains that the money is payment for her son’s illicit passage to America. Now Wilee is faced with a classic choice for an American protagonist: To mind your own business, or to risk your life and livelihood to help someone in distress. He chooses to be a hero, and that means catching up with Manny.

Development (48:00-64:00)

The development section usually doesn’t radically change the premises of the plot. Instead, it’s used to define character further, flesh out secondary aspects of the situation, rework motifs, build suspense, and, surprisingly, simply delay the conclusion. Premium Rush offers a good example of several of these functions. Pedaling frantically after Manny, Wilee phones him and offers him money to give him the envelope. Manny could have accepted, and that would initiate the climax right away.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

This section builds to a pile-up that ends with what we saw at the film’s beginning: Wilee sailing across the frame and landing on the pavement. Dazed, he remembers meeting Vanessa at a bar, where he won a prize as top messenger–the prize being the bike he’s been riding. Each of the three sections we’ve seen includes a flashback, but this is the first one presented as a character’s memory.

Climax (64:00-83:49)

One sign of a climax is this: We know everything we need to know. We know what the ticket means, what all the characters want, and what the stakes are. Now we just have to watch their plans work. In the ambulance, Wilee is suffering from cracked ribs, and Monday bends over him, whacking the ribs to make him talk. Wilee admits that he’ll tell everything if he can get his bike back. This is the make-or-break moment: The hero has to find a subterfuge that will accomplish his goal. Recovering the bike will allow him to retrieve the ticket.

The film has relied on crosscutting throughout, but now the technique expands and accelerates. Nima heads for Chinatown. Wilee’s bike is taken to the police impound facility, but Vanessa has followed it there and gets inside. Soon Wilee arrives with Monday, who searches Manny. Inside, Wilee and Vanessa recover the ticket and escape, courtesy of some very flashy bike-riding. They split up: Wilee to deliver the ticket, and Vanessa to assemble a flashmob.

From the start, during Wiley’s voice-over exposition, we’ve been aware that the couriers form a sort of countercultural community, and a very early scene showed bikers stopping to help fallen comrades. (Good old foreshadowing.) Now, as Wilee goes to deliver the ticket, he faces Monday, who has again caught up with him. The messenger community appears and Monday realizes he can’t fight them all. He’s killed by a Chinese gang member, introduced in part 2 and seen en route to the Chinatown showdown.

Wilee delivers the ticket to Sister Chen, and she phones the snakehead in China to report that the boy’s passage has been paid. Nima thanks Wilee, and in a canonical wrapup Vanessa and Wilee embrace. A brief epilogue echoes the beginning by showing Wilee back whizzing through the streets. “Can’t stop. Don’t want to.”

In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, Kristin points out that a film of 80-90 minutes might have only three parts, each 20-30 minutes long. I prefer my layout because it lets each of the first three sections have its own flashback, and it highlights the midpoint–the crucial moment of choice for Wilee. But proponents of a three-act structure would claim that their model accounts for the movie too. The setup would then run to the point at which Wilee escapes from the police station and calls Raj to tell him he wants no part of the deal; the complicating action would consist of Manny’s pickup and the ensuing chase; and the climax, as with my breakdown, would start when Wilee confronts Monday in the ambulance. In this respect, I think Premium Rush would be an enjoyable film to use in teaching some different approaches to Hollywood dramaturgy.

Personal velocity

From another angle, the first three parts (or two, if you insist) are themselves flashbacks from the opening shots. We’re introduced to Wilee as he sails against the sky in slow-motion, hurled from his bike and en route to hitting the pavement. Then in a kind of prologue the narration takes us back to him enthusiastically pedaling through the streets at 5:10 that day. His voice-over confides his love of biking, his refusal to use gears or brakes, and his preternatural ability to avoid collisions. In Wait Frank Partnoy shows how well-practiced athletes slow down their perception of time, giving themselves 200 milliseconds or more to decide how to return a tennis serve or a cricket shot. Thanks to CGI that plays out Wilee’s options within a split second, we see that he has that gift.

You can criticize voice-over exposition like Wilee’s as lazy screenwriting, and sometimes it is. But given the time pressure, both in the story’s deadlines and by the movie’s length, it creates a concise lead-in that sets the rapid pace of the little adventure we’re going on. The same pace informs the layout of the situations.

During the prologue, Vanessa gets concisely characterized. Nearly sideswiped by a cab, she punishes the driver by using her bike chain to amputate his outside mirror. Six minutes into the movie, Wilee gets his assignment; three minutes later he’s picking up the package. A minute or two after that, he’s accosted by the cop Monday. Then we’re off on a swift chase scene, shot and cut with a precision and economy largely missing from the two movie hulks mentioned above. The many stunts–most of them practical ones, not CGI-created; and many quite funny–keep you riveted to the screen. Likewise, the cascade of deadlines gives every scene a time pressure that’s only enhanced by hairbreadth escapes and near-misses in traffic.

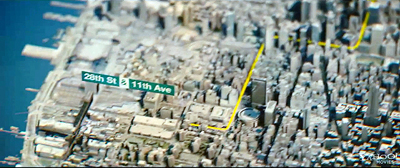

Rapid pacing lets you slip smart things in casually, like the fact that Monday goes by the alias of Forrest J. Ackerman. The use of vaguely Googleized 3D maps, with Wilee’s route traced in yellow and his hypothetical zigzags in white, keeps us oriented briskly. Wilee’s swift, insolent repartee yields comic motifs, which I won’t spoil by specifying. Even the product placement has a jokey quality: these purportedly cool kids are stuck in a Columbia movie, so they all must use Sony Ericsson cellphones (1.8 % global market share last year).

The film employs the redundancy necessary to the Hollywood tradition, but in quickfire fashion. So, for instance, we learn in little bursts that Wilee rides without gears or brakes: he tells us, then later we see his handlebars and axles in close-up, still later Manny mocks his Old School simplicity, and then we see close-ups of Manny’s high-end gear. Finding fresh ways to repeat information is a measure of craft skill. You don’t just restate it; you do it once in words, then images, then contrasting images, and so on. But you can do it all so fast it doesn’t seem redundant. The payoff occurs when Vanessa, warned by Wilee that using brakes will kill her, has a serious crash. In one brief shot she angrily whacks off her brakes, bringing herself closer to his hell-for-leather ethic. Blink and you might miss it.

The film’s use of some common current conventions, like impersonal flashbacks that jigsaw together earlier events in different lines of action, adds to the sense of compression. The replays that show how the lines knot together are quick and simple. Above all, I congratulate director David Koepp, who also wrote the film with John Kamps, on avoiding the obvious. Lesser minds would have called our hero Road Runner and made the futile cop the Coyote figure. Wilee the biker combines the Coyote’s cosmic persistence with the Road Runner’s speed and vocalizations. Joseph Gordon-Leavitt’s grinning giggle comes pretty close to a meep-meep.

Above all, the film’s momentum comes from a plot motored by deadline-driven chases. No other medium can render the exhilaration of sheer headlong velocity. From the early 1900s up to today, cinema is drawn toward people, animals, and machines hurtling across the screen. Vanishing Point, Speed and Premium Rush are tapping the appeals exposed by great chases like those in Keaton’s Cops and The General and less-known Harold Lloyd masterpieces like Girl Shy and For Heaven’s Sake. I sometimes complain about post-1960s Hollywood, but I’ve got to admit that the revival of flamboyant set-piece chases in Burt Reynolds and Clint Eastwood movies, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the action-adventure movies that followed have paid big dividends. Screen action doesn’t have to be rapid, but when it is, and when it involves a race against time, it can be transporting. Sometimes you just want a movie to move.

True, the summer comic-book sagas shift their bulk, but leadenly. When these zeppelins accelerate, they often burst into disjointed imagery. Premium Rush could be a textbook in how to give fast action a clean, cogent profile. When we see energetic movement that’s coherent, unpretentious, and inventive, gracefulness comes along as a bonus. You get another blossom in the Dead Zone.

Assuming that the summer ended on 26 August, Indiewire offers its analysis of summer trends. The most striking news: Overseas box office is about 2/3rds of the total.

Business over Labor Day weekend, which might also be counted as the end of summer, was somewhat stronger, with one robust win (The Possession, at $21 million). Box Office Mojo‘s report from 2 September doesn’t even mention Premium Rush, which is projected to finish Monday with a total to date of about $13.5 million. See also Leonard Klady’s summer wrapup at Movie City News.

Kristin discusses the structural patterns of mainstream American movies in the first chapter of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and offers many examples in later chapters. I test it on more recent cases in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

P.S. 4 September 2012: Thanks to a tweet from K. J. Hargan, I learn of a suit from a writer claiming that the movie is based on a novel he wrote in 1998. [2013 update: The plaintiff lost the case in April.]

P.P.S. 5 September 2012: David Koepp has written me with more information about his goals in making the film.

Nothing about Premium Rush was easy. The extreme nature of the work on the city streets, the physical risks to the actors and stunt performers, and our determination to find our entertainment value in real physical performance rather than CG work (except in certain obvious situations where it was played for laughs) all raised the degree of difficulty in their own way.

But one of the most gratifying things about your analysis was your appreciation of our structure, and how hard we worked to make a film of breathless brevity, in the great tradition of B pictures for decades. I realize that, as far as aesthetic criteria go, “short” doesn’t sound like a terribly high-minded one, but to me it was an essential guiding principle and a hard one to pull off. Your understanding of the value of a brisk pace and a tight running time made me smile, and your respect for the amount of love and effort some of us put into genre work is much appreciated.

Many thanks to David for the kind note.

Nolan vs. Nolan

DB here:

Paul Thomas Anderson, the Wachowskis, David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and other directors who made breakthrough films at the end of the 1990s have managed to win either popular or critical success, and sometimes both. None, though, has had as meteoric a career as Christopher Nolan.

His films have earned $3.3 billion at the global box office, and the total is still swelling. On IMDB’s Top 250 list, as populist a measure as we can find, The Dark Knight (2008) is ranked number 8 with over 750,000 votes, while Inception (2010), at number 14, earned nearly 600,000. The Dark Knight Rises (2012), on release for less than a month, is already ranked at number 18. Remarkably, many critics have lined up as well, embracing both Nolan’s more offbeat productions, like Memento (2000) and The Prestige (2006), and his blockbusters. Nolan is now routinely considered one of the most accomplished living filmmakers.

Yet many critics fiercely dislike his work. They regard it as intellectually shallow, dramatically clumsy, and technically inept. As far as I can tell, no popular filmmaker’s work of recent years has received the sort of harsh, meticulous dissection Jim Emerson and A. D. Jameson have applied to Nolan’s films. (See the codicil for numerous links.) People who shrug at continuity errors and patchy plots in ordinary productions have dwelt on them in Nolan’s movies. The attack is probably a response to his elevated reputation. Having been raised so high, he has farther to fall.

I have only a welterweight dog in this fight, because I admire some of Nolan’s films, for reasons I hope to make clear later. Nolan is, I think all parties will agree, an innovative filmmaker. Some will argue that his innovations are feeble, but that’s beside my point here. His career offers us an occasion to think through some issues about creativity and innovation in popular cinema.

Four dimensions, at least

First, let’s ask: How can a filmmaker innovate? I see four primary ways.

You can innovate by tackling new subject matter. This is a common strategy of documentary cinema, which often shows us a slice of our world we haven’t seen or even known about before—from Spellbound to Vernon, Florida.

You can also innovate by developing new themes. The 1950s “liberal Westerns” substituted a brotherhood-of-man theme for the Manifest-Destiny theme that had driven earlier Western movies. The subject matter, the conquest of the West by white settlers and a national government, was given a different thematic coloring (which of course varied from film to film). Science fiction films were once dominated by conceptions of future technology as sleek and clean, but after Alien, we saw that the future might be just as dilapidated as the present.

Apart from subject or theme, you can innovate by trying out new formal strategies. This option is evident in fictional narrative cinema, where plot structure or narration can be treated in fresh ways. Many entries on this blog have charted possible formal innovations, such as having a house narrate the story action, or arranging the plot so as to create contradictory chains of events. Documentaries have experimented with a film’s overall form as well, of course, as The Thin Blue Line and Man with a Movie Camera. Stan Brakhage’s creation of “lyrical cinema” would be an example of formal innovation in avant-garde cinema.

Finally, you can innovate at the level of style—the patterning of film technique, the audiovisual texture of the movie. A clear example would be Godard’s jump cuts in A Bout de souffle, but new techniques of shooting, staging, framing, lighting, color design, and sound work would also count. In Cloverfield and Chronicle, the first-person camera technique is applied, in different ways, to a science-fiction tale. Often, technological changes trigger stylistic innovation, as with the Dolby ATMOS system now encouraging filmmakers to create sound effects that seem to be occurring above our heads.

I see other means of innovation—for instance, stunt casting, or new marketing strategies—but these four offer an initial point of departure. How then might we capture Nolan’s cinematic innovations?

Style without style

Well, on the whole they aren’t stylistic. Those who consider him a weak stylist can find evidence in Insomnia (2002), his first studio film. Spoilers ahead.

A Los Angeles detective and his partner come to an Alaskan town to investigate the murder of a teenage girl. While chasing a suspect in the fog, Dormer shoots his partner Hap and then lies about it, trying to pin the killing on the suspect. But the suspect, a famous author who did kill the girl, knows what really happened. He pressures Dormer to cover for both of them by framing the girl’s boyfriend. Meanwhile, Dormer is undergoing scrutiny by Ellie, a young officer who idolizes him but who must investigate Hap’s death. And throughout it all, Dormer becomes bleary and disoriented because, the twenty-four-hour daylight won’t let him sleep. (His name seems a screenwriter’s conceit, invoking dormir, to sleep.)

Nolan said at the time that what interested him in the script—already bought by Warners and offered to him after Memento—was the prospect of character subjectivity.

A big part of my interest in filmmaking is an interest in showing the audience a story through a character’s point of view. It’s interesting to try and do that and maintain a relatively natural look.

He wanted, as he says on the DVD commentary, to keep the audience in Dormer’s head. Having already done that to an extent in Memento, he saw it as a logical way of presenting Dormer’s slow crackup.

But how to go subjective? Nolan chose to break up scenes with fragmentary flashes of the crime and of clues—painted nails, a necklace. Early in the film, Dormer is studying Kay Connell’s corpse, and we get flashes of the murder and its grisly aftermath, the killer sprucing up the corpse.

At first it seems that Dormer intuits what happened by noticing clues on Kay’s body. But the film’s credits started with similar glimpses of the killing, as if from the killer’s point of view, and there’s an ambiguity about whether the interpolated images later are Dormer’s imaginative reconstruction, or reminders of the killer’s vision—establishing that uneasy link of cop and crook that is a staple of the crime film.

Similarly, abrupt cutting is used to introduce a cluster of images that gets clarified in the course of the film. At the start, we see blood seeping through threads, and then shots of hands carefully depositing blood on a fabric (above). Then we see shots of Dormer, awaking jerkily while flying in to the crime scene. Are these enigmatic images more extracts from the crime, or are they something else? We’ll learn in the course of the film that these are flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of another suspect back in Los Angeles. Once again, these images get anchored as more or less subjective, and they echo the killer’s patient tidying up.

Nolan’s reliance on rapid cutting in these passages is typical of his style generally. Insomia has over 3400 shots in its 111 minutes, making the average shot just under two seconds long. Rapid editing like this can suit bursts of mental imagery, but it’s hard to sustain in meat-and-potatoes dialogue scenes. Yet Nolan tries.

In lectures I’ve used the scene in which Dormer and Hap arrive at the Alaskan police station as an example of the over-busy tempo that can come along with a style based in “intensified continuity.” In a seventy-second scene, there are 39 shots, so the average is about 1.8 seconds—a pace typical of the film and of the intensified approach generally.

Apart from one exterior long-shot of the police station and four inserts of hands, the characters’ interplay is captured almost entirely in singles—that is, shots of only one actor. Out of the 34 shots of actors’ faces and upper bodies, 24 are singles. Most of these serve to pick up individual lines of dialogue or characters’ reactions to other lines. The singles are shot with telephoto lenses, a choice exemplifying what I called the tendency toward “bipolar” lens lengths in intensified continuity–that is, either very long lenses or fairly wide-angle ones.

Fast cutting like this need not break up traditional spatial orientation. In this scene, there are a couple of bumps in the eyeline-matching, but basically continuity principles are respected. As Nolan explains on the DVD commentary, he tried to anchor the axis of action, or 180-degree line, around Dormer/Pacino, so the eyelines were consistent with his position, and that’s usually the case here.

I can’t illustrate all the shots here, but despite its more or less cogent continuity, the scene seems to me choppy, uneconomical, and fairly perfunctory in its stylistic handling. Nolan makes no effort to move the actors around the set in a way that would underscore the dramatic development. Because of the rapid editing, characters’ lines and gestures are cut off or unprepared for. There is no effort to design each shot, à la Hitchcock, to fit the line or reaction of the actor. Most shots are excerpted from full takes, all from the same setup. The most obvious example is the setup that pans to show Dormer as he comes in, stops, and reacts to the conversation. Thirteen shots are taken from that setup (not necessarily the same full take, of course, as the last frame here shows).

In Nolan’s recent films, this avoidance of tightly designed compositions may be encouraged further because he’s shooting in both the 1.43 Imax ratio and the 2.40 anamorphic one. There remains a general tendency toward loose, roughly centered framings.

Somebody is sure to reply that the nervous editing is aiming to express Dormer’s anxiety about the investigation into his career. But that would be too broad an explanation. On the same grounds, every awkwardly-edited film could be said to be expressing dramatic tensions within or among the characters. Moreover, even when Dormer’s not present, the same choppy cutting is on display.

Consider the 23 shots showing Ellie greeting Dormer and Hap as they get off the plane. Again we have full production takes broken up into brief phases of action (it takes five shots to get Dormer out of the plane), with an almost arbitrarily succession of shot scales. When Ellie leaves her vehicle to go out on the pier, the action is presented in nine shots.

We can imagine a simpler presentation—perhaps after an establishing shot, we track with Ellie down along the dock (so we can see her smiling anticipation), then pan with her walking leftward into a framing that prepares for the plane hatch to open. Arguably, the need to show off production values—the vast natural landscape, the swooping plane descending—pressed Nolan to include some of the extra shots. They don’t do much dramatically, and the strange cut back to an extreme long-shot (to cover the change to a new angle on Ellie?) may negate whatever affinity with her that the closer shots aim to build up.

Swedish sleeplessness

Magic Mike.

Want an up-to-date comparison? Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike has a quiet, clean style that conveys each story point without fanfare. Soderbergh saves his singles for major moments and drops back for long-running master shots when character interaction counts. His cuts are just that; they trim fat. He doesn’t resort to those short-lived push-in camera movements that Nolan seems addicted to. He doesn’t waste time with filler shots of people going in and out of buildings, or aerial views of a cityscape. Soderbergh can provide an unfussy 70s-ish telephoto long take of Mike and Brooke walking along a pier and settling down at a picnic table in front of a Go-Kart track while her brother Adam materializes in the distance. In a single year, with Contagion, Haywire, and Magic Mike, Soderbergh has confirmed himself as our master of the intelligent midrange picture. To anyone who cares to watch, these movies give lessons in discreet, compact direction.

For a more pertinent contrast case, we can go back Insomnia’s source, the 1997 Norwegian film of the same name written and directed by Erik Skjoldbjaerg. Here a Swedish detective, vaguely under suspicion for an infraction of duty, comes to a town on the Arctic Circle for a murder investigation. The plot is roughly similar in its premise, but the working out is quite different, and I can’t do justice to it here. Let me mention just two points of contrast.

First, the cutting is less jagged. Skjoldbjaerg’s film comes in at ninety-seven minutes, about fifteen minutes shorter than Nolan’s, and its cutting rate is much slower, around 5.4 seconds. That means that many passages are built out of sustained shots, particularly ones showing the detective Jonas Engström walking or sitting in a brooding, self-contained silence. Also, this version finds ways to convey several bits of information concisely, in carefully designed shots. For a straightforward example: We see Engstrom’s eyes open, as he’s unable to sleep, and then he lifts his head. Rack focus to the clock behind him.

Nolan uses several shots to get across a comparable point.

As for subjectivity, Skoldbjaerg is just as keen to get us inside his detective’s head as Nolan is. At times he uses the sort of flash-cutting Nolan employs, so we get fragmentary reminders of the fog-clouded shooting. But Skoldbjaerg doesn’t tease us with unattributed inserts (Nolan’s flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of a suspect), and he never suggests, via images of the murder and its cleanup, that his detective can imagine the crime concretely. Instead, Skoldbjaerg often evokes his character’s unease through camera movements that upset our sense of his spatial location. The camera shows Engstrom striding into a room…and then swivels rightward to show him in his original location, as if he’s sneaked around behind our back.

Then Engstrom turns, and we hear a footstep. Cut to a shot showing that the sound is made by him, walking in another room.

I’m not going to suggest that Skoldbaerg innovates more radically than Nolan does, though most viewers probably are more startled by these devices than by Nolan’s. I think that the original Insomnia’s stylistic gamesmanship owes something to other precedents, going back to Dreyer’s Vampyr. What I find more interesting is that Nolan had available the prior example of these strategies from his Nordic source, and he still chose to go with the more conventional, cutting-based options.

The editing-driven, somewhat catch-as-catch-can approach to staging and shooting is clearly Nolan’s preference for many projects. He doesn’t prepare shot lists, and he storyboards only the big action sequences. As his DP Wally Pfister remarks, “What I do is not complicated.” Comparing their production method to documentary filming, he adds: “A lot of the spirit of it is: How fast can we shoot this?”

Throwing it against the wall

We can find this loose shooting and brusque editing in most of Nolan’s films, and so they don’t seem to me to display innovative, or particularly skilful, visual style. I’m going to assume that his strengths aren’t in the choice of subjects either, since genre considerations have kept him to superheroics and psychological crime and mystery. I think his chief areas of innovation lie in theme and form.

The thematic dimension is easy to see. There’s the issue of uncertain identity, which becomes explicit in Memento and the Batman films. The lost-woman motif, from Leonard’s wife in Memento to Rachel in the two late Batman movies, gives Nolan’s films the recurring theme of vengeance, as well as the romantic one of the man doomed to solitude and unhappiness, always grieving. If this almost obsessive circling around personal identity and the loss of wife or lover carries emotional conviction, it owes a good deal to the performances of Guy Pearce, Hugh Jackman, Christian Bale, and Leonardo DiCaprio, who put some flesh on Nolan’s somewhat schematic situations.

You can argue that these psychological themes aren’t especially original, especially in mystery-based plots, but the Batman films offer something fresher. The Dark Knight trilogy has attracted attention for its willingness to suggest real-world resonance in comic-book material. Umberto Eco once objected that Superman, who has the power to redirect rivers, prevent asteroid collisions, and expose political corruption, devotes too much of his time to thwarting bank robbers. Nolan and his colleagues have sought to answer Eco’s charge by imbuing the usual string of heists, fights, chases, explosions, kidnappings, ticking bombs, and pistols-to-the-head with sociopolitical gravitas. The Dark Knight invokes ideas about terrorism, torture, surveillance, and the need to keep the public in the dark about its heroes. Something similar has happened with The Dark Knight Rises, leaving commentators to puzzle out what it’s saying about financial manipulation, class inequities, and the 99 percent/ 1 percent debate.

Nolan and his collaborators are doubtless doing something ambitious in giving the superhero genre a new weightiness. Yet I found The Dark Knight Rises, like its predecessor, unable to bear the burden. It seemed to me at once pretentious and confused in a manner typical of Hollywood’s traditional handling of topical themes.

The confusion comes into focus when journalists, needing an angle on this week’s release, look for a coherent reflection of that elusive, probably imaginary zeitgeist. I think that most popular films don’t capture the spirit of the time, assuming such a thing exists, but simply opportunistically stitch together whatever lies to hand. Let me recycle what I wrote four years ago.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). . . .

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do that. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Since I wrote that, Nolan has confirmed my hunch. He says of the new Batman movie:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Just to be clear, I don’t think the just-telling-a-story alibi is bulletproof. The cultural mix on display in a movie can still exclude certain ideological possibilities, or frame the materials in ways that slant how spectators take them up. My point is only that we ought not to expect popular movies, or indeed many movies, to offer crisp, transparent visions of politics or society. Thematic murkiness and confusion are the norm, and the movie’s inconsistencies may reflect nothing more than the makers’ adroit scavenging.

Subjectivity and crosscutting

Nolan’s innovations seem strongest in the realm of narrative form. He’s fascinated by unusual storytelling strategies. Those aren’t developed at full stretch in Insomnia or the Dark Knight trilogy, but other films put them on display.

One way to capture his formal ambitions, I think, is to see them as an effort to reconcile character subjectivity with large-scale crosscutting. Nolan has pointed out his keen interest in both strategies. But on the face of it, they’re opposed. Techniques of subjectivity plunge us into what one character perceives or feels or thinks. Crosscutting typically creates much more unrestricted field of view, shifting us from person to person, place to place. One is intensive, the other expansive; one is a local effect, the other becomes the basis of the film’s enveloping architecture.

The Batman trilogy has plenty of crosscutting, but as far as I can tell, subjectivity takes a back seat. Nolan’s first two films reconcile subjectivity and crosscutting in more unusual ways. Following takes a linear story, breaks it into four stretches, and then intercuts them. But instead of expanding our range of knowledge to many characters, nearly all the sections are confined to what happens to one protagonist, and they’re presented as his recounted memories in a Q & A situation.

Likewise, Memento confines us to a single protagonist and skips between his memories and immediate experiences. Again what might be a single, linear timeline is split, but then one series of incidents is presented as moving chronologically while another is presented in reverse order. Again, the competing time trajectories aren’t presented as large blocks but are fairly swiftly crosscut.

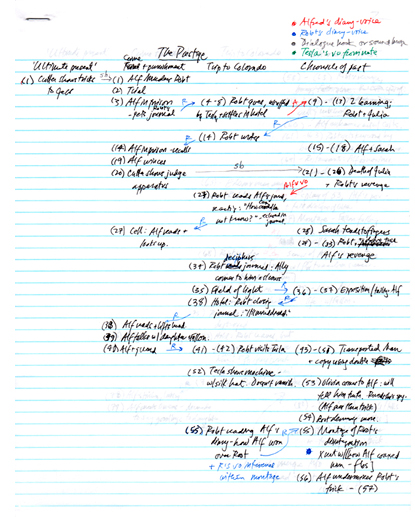

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

With Inception, subjectivity takes the shape of dreaming, and the crosscutting is now among layers of dreams. The embedding that we find in The Prestige is now carried to an extreme; in the long, climactic final sequence a group dream frames another dream which frames another, and so on, to five levels. Once again, these all get intercut (although Nolan wisely refrains from reminding us of the outermost frame too often, so that our eventual return to it can be sensed more strongly).

Kristin and I have written at length about these strategies in earlier entries (here and here). To recapitulate, Kristin found Inception‘s reliance on continuous exposition a worthwhile experiment, and I argued that the lucid-dreaming gimmick was simply a motivational strategy, a pretext for connecting multiple plotlines through embedding rather than parallel action. My point in the first essay is summed up here:

As ambitious artists compete to engineer clockwork narratives and puzzle films, Nolan raises the stakes by reviving a very old tradition, that of the embedded story. He motivates it through dreams and modernizes it with a blend of science fiction, fantasy, action pictures, and male masochism. Above all, the dream motivation allows him to crosscut four embedded stories, all built on classic Hollywood plot arcs. In the process he creates a virtuoso stretch of cinematic storytelling.

My later thoughts tried to survey the breadth of Nolan’s development of formal strategies. Here’s my conclusion:

From this perspective, Inception marks a step forward in Nolan’s exploration of telling a story by crosscutting different time frames. You can even measure the changes quantitatively. Following contains four timelines and intercuts (for the most part) three. Memento intercuts two timelines, but one moves backward. Like Following, The Prestige contains four timelines and intercuts three, but it opens the way toward intercutting embedded stories. The climax of Inception intercuts four embedded timelines, all of them framed by a fifth, the plane trip in the present. For reasons I mentioned in the previous post, it’s possible that Nolan has hit a recursive limit. Any more timelines and most viewers will get lost.

The Dark Knight Rises hasn’t dulled my respect for Nolan’s ambitions. Very few contemporary American filmmakers have pursued complex storytelling with such thoroughness and ingenuity.

Nolan has made his innovations accessible, I argued, by the way he has motivated them. First, he appeals to genre conventions. Following and Memento are neo-noirs, and we expect that mode to traffic in complex, perhaps nearly incomprehensible plotting and presentation. He has called Inception a heist film, and what many viewers objected to—its constant explanation of the rules of dream invasion—is not so far from the steady flow of information we get in a caper movie. In the heist genre, Nolan remarks, exposition is entertainment. Further, the separate dreams rely on familiar action-movie conventions: the car chase that ends with a plunge into space, the fight in a hotel corridor, the assault on a fortress, and so on.

But I should have mentioned another method of motivation–one that helps make the films comprehensible to a broad audience. In some cases the formal trickery is justified by the very subjectivity the film embraces. It’s one thing to tell a story in reverse chronology, as Pinter does in Betrayal; but Memento’s broken timeline gets extra motivation from the protagonist’s purported (not clinically realistic) anterograde memory loss. (We’ve already seen a lot of amnesia in film noirs.) Subjectivity is enhanced by the almost constant voice-over narration, reiterating not only Leonard’s thoughts but what he writes incessantly on his Polaroids and his flesh.

In The Prestige, each magician’s journal records not only his trade secrets but his awareness that his rival might be reading his words, so we ought to expect traps and false trails. And in Inception, the notion of plunging into a character’s mind becomes literalized as a dream state. Once we accept the conceit of controlled dreaming, we can buy all the spatial and temporal constraints the dream-master Cobb sets forth. As with Memento, Nolan creates a set of rules that allow him to crosscut many different time lines. In each film, the subject matter—memory failure, magicians’ enigmas, controlled dreaming—serves as an alibi for both subjectivity and broken timelines.

Synching story and style

Can you be a good writer without writing particularly well? I think so. James Fenimore Cooper, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, and other significant novelists had many virtues, but elegant prose was not among them. In popular fiction we treasure flawless wordsmiths like P. G. Wodehouse and Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, but we tolerate bland or clumsy style if a gripping plot and vivid characters keep us turning the pages. From Burroughs and Doyle to Stieg Larsson and Michael Crichton, we forgive a lot.

Similarly, Nolan’s work deserves attention even though some of it lacks elegance and cohesion at the shot-to-shot level. The stylistic faults I pointed to above and that echo other writers’ critiques are offset by his innovative approach to overarching form. And sometimes he does exercise a stylistic control that suits his broader ambitions. When he mobilizes visual technique to sharpen and nuance his architectural ambitions, we find a solid integration of texture and structure, fine grain and large pattern.

Here’s a one-off example. Nolan has remarked that he’s mostly not fond of slow-motion simply to accentuate a physical action, or to suggest some mental state like dream or memory. Inception motivates slow-motion by another of its arbitrary rules, the idea that at each level of dreaming time moves at a different rate. Here a stylistic cliché is transformed by its role in a larger structure, as Sean Weitner pointed out in a message to us.

Memento displays a more thoroughgoing recruitment of style to the purposes of guiding us through its labyrinth. The jigsaw joins of the plot require that the head and tail of each reverse-chronology segment be carefully shaped, because they will be reiterated in other segments. Within the scenes as well, Nolan displays a solid craftsmanship, with mostly tight shot connections and an absence of stylistic bumps.

He can even slow things down enough for a fifty-second two-shot that develops both drama and humor. Leonard has just shown Teddy the man bound and gagged in his closet, and Teddy wonders how they can get him out. In a nice little gag, Leonard produces a gun from below the frameline (we’ve seen him hide it in a drawer) and then reflects that it must be his prisoner’s piece. This sort of use of off-frame space to build and pay off audience expectations seems rare in Nolan’s scenes.

The moment is capped when Leonard adds, “I don’t think they let someone like me carry a gun,” as he darts out of the frame.

The straightforward stylistic treatment of Memento‘s more-or-less present-time scenes, both chronological and reversed, is counterbalanced by the rapid, impressionistic handheld work that characterizes Leonard’s flashbacks to his domestic life and his wife’s death (in color) and his flashbacks to the life of Sammy Jankis (in black-and-white). Nolan shrewdly segregates his techniques according to time zone.

If anything, The Prestige displays even more exactitude. Facing two protagonists and many flashbacks and replayed events, we could easily become lost. Here Nolan doesn’t use black-and-white to mark off a separate zone. Instead he relies more on us to keep all the strands straight, but he helps us with voice-overs and repeated and varied setups that quietly orient us to recurrent spaces and circumstances. Here Nolan’s preference for cutting together singles is subjected to a simple but crisp logic that relies on our memory to grasp the developing drama.

I’ve discussed these stylistic strategies in another entry and in Chapter 7 of Film Art. More generally, they serve the larger dynamic of the plot, which creates a mystery around Alfred Borden, hides crucial information while hinting at it, invites us to sympathize with Borden’s adversary Robert Angier (another widower by violence), and then shifts our sympathies back to Borden when we learn how the thirst for revenge has unhinged Robert. To achieve the unreliable, oscillating narration of The Prestige, Nolan has polished his film’s stylistic surface with considerable care.

Midcult auteur?

Trying to specify Nolan’s innovations, I’m aware that one response might be this: Those innovations are too cautious. He not only motivates his formal experiments, he over-motivates them. Poor Leonard, telling everyone he meets about his memory deficit, is also telling us again and again, while the continuous exposition of Inception would seem to apologize too much. Films like Resnais’ La Guerre est finie and Ruiz’s Mysteries of Lisbon play with subjectivity, crosscutting, and embedded stories, but they don’t need to spell out and keep providing alibis for their formal strategies. In these films, it takes a while for us to figure out the shape of the game we’re playing.

We seem to be on that ground identified by Dwight Macdonald long ago as Midcult: that form of vulgarized modernism that makes formal experiment too easy for the audience. One of Macdonald’s examples is Our Town, a folksy, ingratiating dilution of Asian and Brechtian dramaturgy. Nolan’s narrative tricks, some might say, take only one step beyond what is normal in commercial cinema. They make things a little more difficult, but you can quickly get comfortable with them. To put it unkindly, we might say it’s storytelling for Humanities majors.

Much as I respect Macdonald, I think that not all artistic experiments need to be difficult. There’s “light modernism” too: Satie and Prokofiev as well as Schoenberg, Marianne Moore as well as T. S. Eliot, Borges as well as Joyce. Approached from the Masscult side, comic strips have given us Krazy Kat and Polly and Her Pals and, more recently, Chris Ware. Nolan’s work isn’t perfect, but it joins a tradition, not finished yet, of showing that the bounds of popular art are remarkably flexible, and imaginative creators can find new ways to stretch them.

Box-office figures for Nolan’s films are compiled from Box Office Mojo. For detailed critiques of Nolan’s style, see Jim Emerson’s entries archived here; Jim’s video essay dissecting one Dark Knight action scene is here. A. D. Jameson’s essays on Inception are here and here.

Nolan discusses the background to Insomnia in John Pavlus, “Sleepless in Alaska,” American Cinematographer 83, 5 (May 2002), 34-45. My quotation about subjectivity comes from pp. 35-36. By the way, Insomnia does create a moment of tense quiet during the longish dialogue between Dormer and the killer Finch (Robin Williams) on the ferry: some sustained two shots give the adversaries time to size each other up (and Pacino gets an occasion to execute some business with an iron pole). Although the setup is broken by some irrelevant cutaways to the passing vistas, perhaps to cover faults in the takes, the sequence shows something of the sustained calm that we find in moments in Memento and The Prestige.

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for the Wally Pfister link.

Umberto Eco’s 1972 essay, “The Myth of Superman,” appears in his book, The Role of the Reader. Portions are available here. One relevant passage is this: “He is busy by preference, not against black-market drugs nor, obviously, against corrupt administrators or politicians, but against bank and mail-truck robbers. In other words, the only visible form that evil assumes is an attempt on private property” (p. 123; italics in original).

Dwight Macdonald’s 1960 essay is available in Masscult and Midcult. A pdf is online here. Macdonald seems to have softened his demands a bit in later years. He praised 8 1/2, softcore modernism for sure, as Shakespearean in its vivacity. “The general structure–a montage of tenses, a mosaic of time blocks–recalls Intolerance, Kane, and Marienbad, but in Fellini’s hands it becomes light, fluid, evanescent. And delightfully obvious.” The essay is reprinted in Dwight Macdonald on Movies, pp. 15-31.

J. J. Murphy has a detailed analysis of Memento in his book Me and You and Memento and Fargo. I discuss the film’s contribution to complex storytelling trends in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 74-82, where I also discuss the notion of intensified continuity editing. We analyze The Prestige‘s narrative, narration, and sound techniques in Film Art: An Introduction (ninth ed., pp. 298-307; tenth ed., pp. 298-306).

P.S. 19 August: Thanks to Guillaume Campreau-Dupras for correcting a film title.

PS 27 August: Thanks to the many bloggers and tweeters who linked to this entry!

The tireless A. D. Jameson has posted another probing critique of Nolan’s Bat-saga, this one concentrating on TDKR, here. While making serious points about Nolan’s use of expository dialogue and the confused politics of the film, the essay also contains some good jokes.

I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading

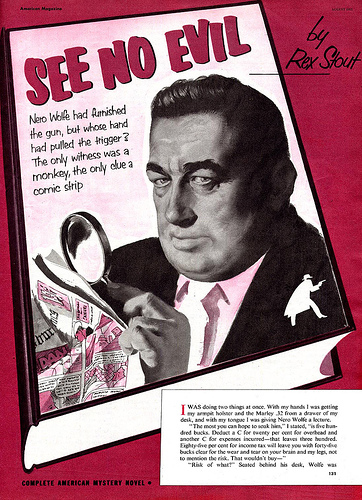

Thornton Utz illustration for Rex Stout novella from American Magazine, 1951. Obtained from the excellent site Today’s Inspiration.

DB here:

Over the next few months, I’ll be traveling with a talk on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. The ideas I’ll propose are destined for a book about narrative norms during that period. Mystery fiction is important to that lecture, but I don’t have room there to supply much background about the relevant conventions. So I’m sketching in this background here, for people who might hear the talk somewhere or who might just be curious. Consider this as another experiment on the blog, using the web to supplement a lecture.

Although the lecture is mostly about cinema, this entry is mostly about novels and plays. But I’ll mention film here and there, and you’ll notice that some of the books and plays I mention were adapted for the screen.

A mega-genre

The first half of the twentieth century saw an explosive expansion in genres built around mystery and suspense. The most obvious genre is the detective story. In the wake of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, a great many writers developed and elaborated on the idea of the master sleuth, the genius of observation and reason. Central to this tradition was the puzzle that could be solved by careful noting of clues and meticulous reasoning about them, supplemented by a good knowledge of human nature or local customs. The author needs to keep us in the dark about both the crime and the detective’s chain of reasoning; hence point-of-view figures like Watson, who can be appropriately confounded, relay the detective’s cryptic hints, and marvel at the final revelations.

Readers quickly learned the conventions, so writers had to innovate constantly. Sometimes a writer was original on more than one front. For example, R. Austin Freeman created a revamped Holmes surrogate in a scientific criminologist, Dr. Thorndyke, while also creating a new narrative structure: that of the “inverted” tale. The first section of the story follows the criminal who commits the crime; the second part details how Thorndyke, using evidence and inference, solves it.

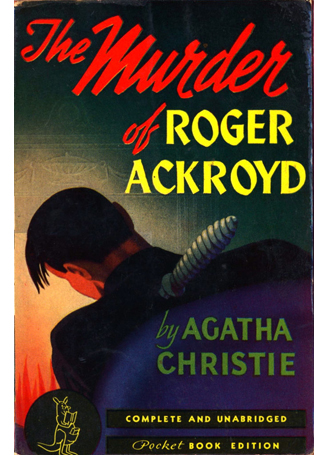

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

It’s hard for us to conceive today how massively popular these puzzle books were. Van Dine’s first novels were bestsellers comparable to Jonathan Kellerman’s books today. Just as important, the detective story was granted quasi-literary status. Magazines and newspapers that wouldn’t dream of reviewing romance or adventure fiction devoted space to detective stories, sometimes even setting up separate columns or sections for reviews. It was believed, rightly or wrongly, that whodunits had a more intellectual readership than Westerns or science fiction.

At about the same time, according to the standard account, a counter-current was swelling. In the pulp magazines of the 1920s, the “hard-boiled” detective emerged as an alternative to the master sleuth. The prototype is Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op in stories through the late 1920s, to be followed by Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930). Strikingly, Hammett and other hard-boiled writers don’t wholly abandon the basic idea of solving a mystery through some sort of reasoning. The differences have to do with realism. The crimes, however, aren’t usually fantastical ones like the Locked-Room problem; the killings tend to be mundane. If the white-glove detective’s only real opponent is a master criminal like Professor Moriarty, the hard-boiled detective faces off against organized crime, or at least people who commit murder outside upper-crust parlors and remote country houses. Clues are less likely to be physical, and more psychological, depending on bits of behavior or flashes of temperament. Raymond Chandler and others took the hard-boiled initiative into the 1940s, and the brute detective, who solves crimes with boldness, insolence, and a pair of fists, occasionally supplemented by torture, found bestseller status in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1947) and subsequent novels.

I’d argue that some writers could blend the master-mind detective and the tough guy. Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason was one such hybrid, though leaning closer to the hard-boiled model. Rex Stout solved the problem neatly by creating two detectives: the insolent legman Archie Goodwin serves as a hard-boiled Watson to sedentary Nero Wolfe. But on the whole, historians tend to assume that the Holmesian superman and the puzzle-dominated plot were swept aside by the rise of the tough-guy detective solving mysteries that were grittier and more “realistic” than what had preoccupied Golden Age writers.

Two other major developments are typically highlighted by historians. There was the police procedural, perhaps initiated by Lawrence Treat’s V as in Victim (1945), and explored with great ingenuity in the novels of Ed McBain. There was also what Julian Symons has called the “crime novel,” the story of psychological suspense, with Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950) serving as a good example. Both of these genres have proven popular to this day (CSI as a procedural, the films of De Palma as psychological thrillers).

A tree and its branches

Like most histories hovering fairly far above the ground, the standard account traces some main contours of the landscape but misses some interesting byways. By taking Doyle as the prototype, this account tends to identify mystery fiction with detective plots in the Holmes mold. But mysteries come up in other forms.

The standard account has trouble accommodating the development of the spy genre, which often involves solving a crime, but less through abstract reasoning than by putting the hero through hairbreadth adventures. Think for instance of The 39 Steps, both the 1915 novel and the 1935 film.

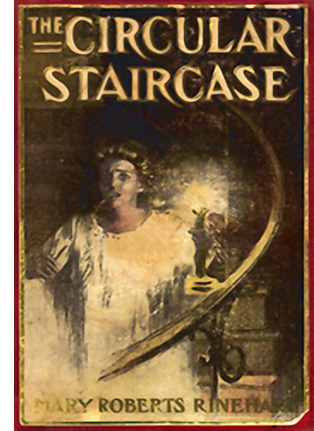

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

Jane Eyre is an obvious source for Rinehart and her successors, and perhaps the association with women’s writing in general made historians and practitioners of the Golden Age mock the revived Gothic as too feminine, too far removed from the bluff masculine camaraderie of 221 B Baker Street. The Gothicists had their revenge: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) outsold every other mystery novel of its time and sustained a cycle of new sensation novels by Mabel Seeley (The Chuckling Fingers, 1941), Charlotte Armstrong (The Chocolate Cobweb, 1948), and Hilda Lawrence (The Pavilion, 1946). The genre is maintained today by Mary Higgins Clark, Nicci French, and many other writers.

So mystery and detection formed a broader tradition than literary historians sometimes acknowledge. Another marginal form was the suspense thriller. Again, we can point to a woman: Marie Belloc Lowndes, author of The Lodger (1913). An early instance of the serial-killer plot, it’s also a tour de force of point-of-view; unlike the film versions, it restricts itself quite rigorously to what certain secondary characters know. Choices about narration and viewpoint are no less crucial to the thriller than to the Great Detective tradition.

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

I personally am convinced that the days of the old crime puzzle pure and simple, relying entirely upon plot, and without any added attractions of character, style, or even humour, are, if not numbered, at any rate in the hands of the auditors. . . The puzzle element will no doubt remain, but it will become a puzzle of character rather than apuzzle of time, place, motive, and opportunity. The question will be not “Who killed the old man in the bathroom?” but “What on earth induced X, of all people, to kill the old man in the bathroom?”

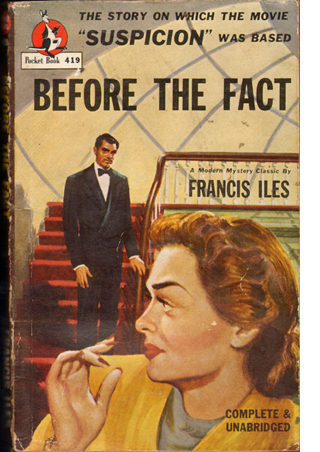

Cox went on to test his premises in Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932). Both trace the schemes of wife-killers, but the first novel is told from the husband’s standpoint and the second from the wife’s. The latter book opens:

Some women give birth to murderers, some go to bed with them, and some marry them. Lina Aysgarth had lived with her husband for nearly eight years before she realized that she was married to a murderer.

There followed other domestic-crime psychological novels, notably Richard Hull’s The Murder of My Aunt (1934).

Sometimes suspense thrillers have a solid mystery at their center; this is common when the protagonist is a potential victim. Other thriller plots in effect present the first half of a Freeman “inverted” story, concentrating on the criminal’s execution of a crime and the resulting efforts to escape punishment. Both possibilities were on display in British stage plays of the 1920s and 1930s. In a sense Cox was beaten to the punch by Rope (1929), Blackmail (1929), and Payment Deferred (1931). Later examples are Night Must Fall (1935) and the woman-in-peril dramas Kind Lady (1935) and Gaslight (1938). Many of these plays were made into films.

The novel of suspense really came into its own in the 1940s, when it started to incorporate abnormal psychology. Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gaslight, provided an influential novel as well, Hangover Square (1941). Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis, who mined this nightmarish vein, achieved posthumous cult status because, again, of the spell of film noir. Other suspenseful students of mania were Dorothy B. Hughes (In a Lonely Place, 1947), Charlotte Armstrong (The Unsuspected, 1945; Mischief, 1951, filmed as Don’t Bother to Knock), and Elizabeth Sanxay Holding (The Blank Wall, 1947, source of The Reckless Moment). Chandler called Sanxay Holding “the top suspense writer of them all.” We shouldn’t ignore the influence of Simenon’s romans durs, which were being translated and respectfully reviewed throughout the war years.

Yet another new wrinkle on the mystery thriller was the genre of courtroom novels. The Bellamy Trial (1927), which begins when the trial does and restricts itself almost completely to what transpires in the courtroom, popularized the pattern. Stage plays of the 1920s adopted the pattern too. The format proved irresistible for early talkies, as in adaptations of The Bellamy Trial (1929) and Thru Different Eyes (1929) and the radio-inspired Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932). Cox, who seemed to try his hand at every current trend, gave his own twist to the juridical mystery in Trial and Error (1937).

Most of these novels focused on the trial proceedings from the perspective of the defendant, but a few concentrated on those sitting in judgment. The Jury (1935), by Gerald William Bullett, characterizes the jurors singly before they gather and then shows the trial from their standpoints before taking us into the jury room to hear the arguments. Bullett’s novel finds an equally engrossing complement in Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve (1940). There were also Eden Philpotts’ The Jury (1927) and George Goodchild and C. E. Bechhofer Roberts’ The Jury Disagree (1934). We can immediately recognize the teleplay and film Twelve Angry Men as an updating of this minor line.

Merging and markets

The family tree of mystery, then, grew many branches in the 1920s and 1930s—the pure puzzle, the hard-boiled investigation, the spy story, the revised Gothic or sensation novel, and the suspense thriller, often of a psychological cast. Unsurprisingly, the genres began to mingle. Cox was perhaps the writer most interested in hybrids, but John Dickson Carr tried his hand at the thriller as well (The Burning Court, 1937), as did Agatha Christie in And Then There Were None (aka Ten Little Indians, 1940).

The process sped up during the 1940s, when writers began blending crime-solving with psychological suspense. We can get a sense of how the protagonist-in-peril side of the thriller melded smoothly with the enigma-based investigation by looking at the jacket copy of a fairly ordinary entry, Alarum and Excursion (1944):

Bit by bit, a gesture here, a sound there, Nick Matheny pieced together the awesome puzzle of the accident that had sent him to a sanitarium with traumatic amnesia. One by one he reconstructs, he probes the cirumstances of the explosion in his factory, the disappearance of his weak but beloved son, his wife’s strange attitude toward the new management of the business, and the status of the new synthetic fuel formula, which was so urgently needed.

As the dreadful picture unfolds itself, Nick escapes from the sanitarium to ferret out the sinister changes that have disrupted his business and brought his active life to an abrupt close.

Virginia Perdue, author of He Fell Down Dead, skillfully handles the difficult flash backs in this unusual psychological drama. There are many scenes where the tricks of thought, the tenseness of apprehension, the visions through the deserted streets of blacked-out memory poignantly work their stealth upon the mind of the reader.

Alarum and Excursion wasn’t adapted into a film, but reading this spoiler-filled jacket copy you can easily imagine the movie.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

As mystery genres proliferated, their popularity soared. Contrary to what historians imply, the puzzle novel with a brilliant sleuth was far from defunct. Christie’s Poirot and Sayers’ Wimsey retained their fame into the 1940s, significantly outselling Hammett and Chandler. Ellery Queen’s novels are not read much today, so it’s hard to imagine a time when over a million copies of them were in print. More generally, the public’s appetite for mystery novels and radio plays was intense. In 1940, 40 % of all titles published were mysteries, and in 1945, an average four radio shows devoted to mystery were broadcast every day, each drawing about ten million listeners.

Small wonder, then, that Hollywood came calling. Curiously, the master detectives popular with the reading public wound up in B-film series (Charlie Chan, Ellery Queen) or remained unexploited in the 40s (Nero Wolfe, Perry Mason). What came to the fore, as being more suitable for the dynamic medium of film, were the hard-boiled heroes of Hammett and Chandler. Because the rise of hard-boiled adaptations fed clearly into film noir, they have attracted the most attention. But mutating alongside them, and becoming at least as lucrative, were the films shaped by the updated Gothic and the psychological thriller. Variety noticed the trend in fall of 1944.

Plain murder as a film frightener is passé. Been done too long in the same old way. Theatregoers actually can yawn in the face of manslaughter as it’s been perpetrated for the whodunits during the past year or more. . . . The newer type of horror pictures, invested with psychological implications, deal with mental states rather than melodramatic events. . . . The typical tale in the new genre crawls with living horror, is eerie with something impending, and socks its suspense thrill well along toward the middle of the story instead of doing the crime victim in at the beginning and then building a whodunit and a detective quiz as the element of suspense.

The piece doesn’t respect today’s genre distinctions. Apart from using the term “horror” in a way we wouldn’t, the author lumps together suspense thrillers like The Lodger, Hangover Square, The Uninvited, and The Suspect; the Gothic Gaslight (“a perfect example of the new approach”); and spy thrillers The Mask of Dimitrios and The Ministry of Fear. Even Jane Eyre is included, without irony. (Surprisingly, Double Indemnity from spring 1944 isn’t mentioned.) Still, the article acknowledges that mystery had strong audience appeal and that while the classic whodunit had had its day on the movie screen, films could be given new energy by other literary trends.

Mystery as artifice

Mystery is the only genre I know that makes narrative strategies as such central to its identity. A musical, a Western, or a science-fiction saga can be presented in linear fashion, telling us everything step by step, and still retain a genre identity. But a mystery plot can’t be presented straightforwardly. The writer must manipulate plot structure and narration to some degree.