Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

A man and his Focus

James Schamus on State Street, hailed by local livestock.

DB here:

“I wish,” one of my students said during a James Schamus visit to Madison back in the 1990s, “I could just download his brain.” Probably many have shared that wish. James is an award-winning screenwriter who has become a successful producer and head of a studio division, Focus Features (currently celebrating its tenth anniversary). No one knows more about how the US film industry works than James does. Yet he’s also deeply versed in the history and aesthetics of cinema. He teaches in Columbia’s film program, and his courses involve not filmmaking but film theory and analysis. How many people who can greenlight a picture have written an in-depth book on Dreyer’s Gertrud?

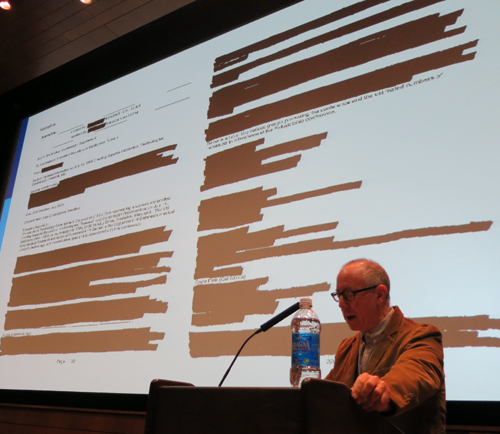

James came to campus last month for our Wisconsin Film Festival. His official event, sponsored by the University Center for the Humanities, was a talk called “My Wife Is a Terrorist: Lessons in Storytelling from the Department of Homeland Security.” That was quite an item in itself, tracing how James’ wife Nancy Kricorian discovered that she had a Homeland Security file. Pursuing that led him to broader meditations on digital surveillance in modern life. If he’s invited to present this in a venue near you, you’ll want to catch this provocative tutorial in how to read a redacted document.

While he was here, James spent a couple of hours in J. J. Murphy’s screenwriting seminar, and of course I had to be there. Herewith, some information and ideas from a sparkling session.

All battleships are gray in the dark

Hulk.

“This is not writing,” Schamus said. By that he meant that a screenplay isn’t parallel to a piece of creative writing, an autonomous work of art. Nobody ever walked out of a movie saying, “Bad film, but a great script.” In this he echoed Jean-Claude Carrière at the Screenwriting Research Network conference I visited back in September. A screenplay is “a description of the best film you can imagine.”

What sort of description? For certain directors, sparse indications are best. Collaborating with Ang Lee, Schamus knows he must under-write. Lee doesn’t want a movie that’s wholly on the page: “Ang wants to solve puzzles.” But for a studio project, the screenplay has to be airtight, since it functions as an insurance package for any director the producers hire. “A script has to be a battleship that no director can sink.”

James pointed out a bit of history. Back in the 1910s Thomas Ince rationalized studio production by using the script as the basis of all planning—budget, schedule, locations, and deployment of resources. The same happens today, with the Assistant Director breaking down the script for different phases and tasks of production. But on a studio project not everything is tidily planned in advance. Scripts can be rewritten during shooting or even later. Sometimes there are “parallel scripts”: stars can hire writers who spin out “production rewrites” to be thrust on the director. James, who has prepared the screenplay for Hulk and done his share of uncredited rewrites on other big films, speaks from experience.

Independent companies rely on screenplays too; Focus is writer-friendly. But in this zone of the industry, the writer needs to create a “community” around a script idea—a director or group of actors and craft people that support it. These are as valuable as a polished screenplay in getting a film funded.

What about the current conventions, like the three-act structure? James rejects the Syd Field formula. He thinks that the writer will spontaneously devise some intriguing incidents and arresting characters without recourse to beats, arcs, and plot points. “You can’t have half an hour go by without giving your characters something to do, or to shoot for.”

He also suggests that the writer’s second draft should be an exercise in rethinking the whole thing. “Don’t write your second draft from the first-draft file.” In your redraft, use flashbacks, play around with structure, or tell the action from a different point of view. This will engage you more deeply with the material and show you possibilities you hadn’t imagined. In terms I’ve floated in various places: take the same story world, but recast the plot structure or the film’s moment-by-moment flow of information (that is, its narration). Or try choosing a different genre. For The Wedding Banquet, James turned the original script, a melodrama, into a situation derived from screwball comedy.

Down in the mosh pit

Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

James has been both an independent producer, in partnership with Ted Hope at Good Machine during the 1990s, and a specialty-division producer with Universal for Focus. The moment of passage for him came when, rewriting Ang Lee’s first feature, Pushing Hands, James realized that he had to get the whole project in shape for filming. After that, and The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman, producing followed naturally.

When James started, a single person could cover most producer duties on an indie film, but now it’s very difficult. Finding material, gathering money, signing talent, checking on principal photography and post-production, planning marketing and distribution across many platforms, tracking payments after release—it’s all a daunting task for one individual. Today an indie movie may list seven to twenty producers. Some probably helped by finding money, some worked especially hard to get material, and a few just slept with somebody.

A traditional producer’s job is to keep the budget under control. Today, with digital filming making special effects cheaper, screenwriters and directors think naturally of more elaborate visuals. This can work with something like Take Shelter, James suggested, but on the whole he thinks that directors shouldn’t jump to extremes. He recalled that using “handcrafted effects” cut the original budget of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by a third, and that led to more unusual creative results, like outsize sets and in-camera trickery.

The “independent cinema” scene has always been quite varied. Again James had recourse to history: in the 1960s both United Artists and Roger Corman were labeled independents. The artier independent side developed through the infusion of foreign money and new technology. From the 1970s onward, overseas public-television channels invested in US films by Jarmusch and others, while cable and home video needed product and so financed or bought indie projects. The video distributor Vestron, for instance, could not acquire studio films, so, armed with half a billion dollars, the company began generating its own content. In the same era, pornography was shot on 35mm, and many crafts people learned in that venue and transferred their skills to independent cinema.

Today, however, the indie market is both more fragmented and more fluid. The spectrum space between tentpole Hollywood and DIY indies is being filled by net platforms and cable television. James pointed to the ease with which Lena Dunham moved from Tiny Furniture to the HBO series Girls. Downloading and streaming add to the churn. IFC and Magnolia distribute films, but these companies are owned by cable channels and hold theatrical venues as well. They acquire scores of new films a year, using theatrical releases to get reviews that can support VOD and DVD. Focus can tier its marketing in similar ways, using DVD and VOD outlets to lead viewers to content online under the rubric Focus World.

These new “paramarkets,” James suggests, are porous, overlapping, and still evolving. Traditional windows, he says, have become a mosh pit.

James had a lot more to say, and I expect to be referencing more of his ideas on VOD in a blog to come. But this gives you a taste of the energy and breadth of his thinking. He’s constantly busy but never less than enthusiastic and generous. He always has time to share ideas about anything, from politics to cinephilia. The most exhilarating thing about talking with him is that you know more excellent work lies ahead.

Apart from titles I’ve already mentioned, James Schamus’ screenplays include The Ice Storm, Ride with the Devil, Taking Woodstock, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Lust, Caution, Films that he produced and/or distributed include Poison, The Brothers McMullen, Safe, Walking and Talking, Happiness, The Pianist, 21 Grams, Lost in Translation, Shaun of the Dead, A Serious Man, Coraline, Brokeback Mountain, The Motorcycle Diaries, Eastern Promises, Atonement, Reservation Road, In Bruges, Milk, Sin Nombre, Greenberg, The Kids Are All Right, The Debt, Pariah, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy…and plenty more.

Schamus provides a video review of the top ten Focus titles chosen by viewers for the company’s anniversary.

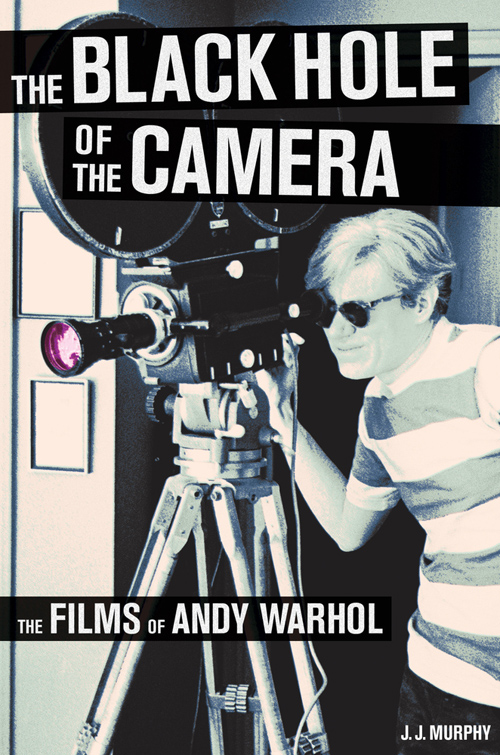

J. J. Murphy blogs about screenwriting, the avant-garde, and independent film here. His most recent book is The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol.

More on the concepts of story world, plot structure, and narration can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in my book Poetics of Cinema. A brief account is here.

James Schamus lecturing, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for the Humanities, 19 April 2012.

Once more, Mad City movies

Night and the City.

DB here:

It’s been a busy time in Madison, at least for me. KT is in Egypt, peering at shards of statues and documenting earlier Armana excavations. I’m at home, having missed the Hong Kong International Film Festival (doctor’s orders) and wistfully wishing I’d been there for the tribute to Peter Chan Ho-sun (check out Fred Ambroisine’s interview at Twitchfilm) and a chance to see—Don’t say whoa!—Keanu Reeves, who was there with Side by Side, his new film on digital cinema (snif).

Instead of traveling, I’ve been doing other stuff. There were, and still are, last-minute checks and fixups on the new edition of Film Art. I went to some movies–Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, The Hunger Games, The Raid: Redemption, Carnage, 21 Jump Street—as well as screenings at our Cinematheque. Late at night I’ve been watching 1940s films for a long-range project. Most frantically, I’ve been working on a little e-book to be finished, I hope, in three weeks. It will be available on this site, ludicrously cheap, you will want one for sure, I bet, well, why not? More about it later.

In the meantime, Madison has hosted some remarkable visits. I’ve already mentioned Lynda Barry’s delightful presentation of Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. I must also mention two other dignitaries that illuminated our lives this spring.

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

More recently, we were visited by Schawn Belston, an old friend who’s Senior Vice-President of Library and Technical Services at Twentieth Century Fox. Our Cinematheque is running a string of Fox restorations, and Schawn brought along a stunning print of the lustrous noir classic Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950).

There’s a nifty story behind that print. Schawn and archivist (and Badger) Mike Pogorzelski discovered an original camera negative in the Movietone News vault in Ogdensburg, Utah. When they struck our print (directly from the neg) and showed it to Dassin a few years ago, he wept with pleasure.

Schawn found another version of unknown provenance. On the basis of the first reel, which he screened for us, this seems to be a British version, with a different voice-over narrator, varying footage and cutting patterns, and a lighter, more romantic score. As Schawn pointed out, this plays more slowly and is more of a melodrama than a thriller; it also makes the Richard Widmark character a little more sympathetic, I thought. Nobody has yet discovered why this version was made.

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

*Lots of filmmakers are still finishing on film, but the plan is to make no prints available to US theatres after 2012. About 300 prints of current titles will still be made for the world market.

*Both Fuji and Kodak are still making film stock, even new emulsions, but the decline in usage will raise prices. A 35mm print now costs $4000, a 70mm print runs $35,000 and up.

*Storage problems are immense. The studio wants to save all the raw footage; in the case of Titanic, that comes to 2.5 million feet. Which version of the film has priority for the shelf? Typically, the longest cut, often the first preview print.

*All studios are still making 35mm negatives for preservation, typically from 4K scans. Ironically, their soundtracks, usually magnetic, can’t match the uncompressed sound of the files on a Digital Cinema Package (DCP).

*”Film is the most stable medium, but the preservation practices for it are the most vulnerable.”

*Nearly all film restoration is digital now, so the best way to show the results is probably digitally. That also makes for standardized presentation and less wear and tear on physical copies.

*Most classic films in a studio library are not available on DCP. If an archive or cinematheque or theatre wants one, there are ways to make on-demand DCPs. But it’s not cheap. A 2K scan runs $40,000; a 4K scan, somewhat more. Schawn opts for 4K because a digital version should be the best possible. It might be the last chance to make one!

*Films stored on digital files must be migrated frequently. Sometimes that’s done through “robotic tape recycling.” But there are problems with the constantly changing formats and standards. The Movietone News library was originally digitized to ID-1, a high-end broadcast tape format from the mid-1990s, so that material will need to be copied to something more current.

*Schawn believes that objective criteria about color, contrast, and other properties need to be balanced with concern for the audience’s experience. By today’s standards, original copies of Gone with the Wind and The Gang’s All Here look surprisingly muted. But to audiences of the time, they probably looked splashy, because viewers saw so few color movies. Restorers and modern viewers have to recognize that perception of a film’s look is comparative, and the terms of the comparison can change.

Schawn’s point was made after his visit with our Cinematheque show of the restored copy of Chad Hanna (Henry King, 1940). For a Technicolor film, it had a surprising amount of solid black, and not just in night scenes. We’re used to “seeing into the dark” via today’s film stocks and digital video formats, and we probably identify Technicolor with the candy-box palette of MGM musicals on DVD. We sometimes forget that chiaroscuro was no less a resource of color film of the 1940s than of black-and-white shooting of the period. A leisurely, charmingly unfocused story with a radiant Linda Darnell (she lights up the dark) and Fonda at his most homespun, Chad Hanna was good in itself and an education in color style circa 1940.

Schawn’s visit, like Tony’s, was informative and plenty of fun. We want to see both again soon.

Up next, as Robert Osborne would say: Some picks for the Wisconsin Film Festival, which launches Wednesday.

Thanks to Jim Healy, Cinematheque programmer, for arranging Schawn’s visit and the Fox retrospective.

Chad Hanna. Not, emphatically not, from 35mm; from Fox Movie Channel.

Bringing to book

Artists and Models.

Blushing from Bryce Renninger’s generous article about us and the new edition of Film Art can’t keep us from offering another of our occasional entries devoted to new books we like. Get ready for lots of peekaboo links.

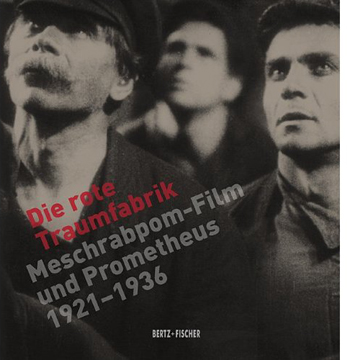

The rise of the Soviet Montage film movement of the 1920s and western countries’ knowledge of those films came about largely because of Germany. After pre-revolutionary film companies fled the Soviet Union, taking much of the country’s film equipment with

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

There was a direct link between Soviet and German socialist film production and distribution that is too little-known today. In 1921, Willi Münzenberg forms the Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (the IAH, known in Russia as Meschrabpom), based in Berlin. In 1924, the organization founded a film studio in Moscow, Rus. A year later, a sister company, Prometheus, was formed in Berlin. Both produced films, and they cooperated in distributing each other’s output.

Meschrabpom-Russ produced many of the familair Soviet classics: early on, Polikuschka and Aelita, and later the films of Pudovkin (including Mother and The End of St. Petersburg) and Boris Barnet (including Miss Mend and House on Trubnoya). Prometheus produced films highly influenced by the Soviet exports, both in terms of style and subject matter. These included Leo Mittler and Albrech V. Blum’s Jenseits der Strasse, Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück, and, mostly famously, Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ottwald’s Kuhle Wampe oder wem gehört die Welt.

Prometheus, not surprisingly, disappeared in 1933. Meschrabpom-Russ continued until 1936.

A retrospective at the Internationale Filmfestspiele in Berlin in 2012 has occasioned a comprehensive, beautifully designed catalogue, Die rote Traumfabrik: Meschrabpom-Film und Promethueus 1921-1936. With numerous expert essays and beautifully reproduced illustrations, both in color and black and white, of posters, production photos, film frames, and documents, this is the definitive publication on the subject. Even those who don’t read German will be able to use the extensive filmography and the biographical entries on the directors and other people involved in the making of the films. The illustrations make this the perfect combination of academic study and coffee-table art book. (KT)

Closer to home, our friends have been very busy. From Leger Grindon, a deeply knowledgeable specialist in American film, comes Knockout: The Boxer and Boxing in American Cinema. The prizefight movie isn’t usually discussed as a distinct genre, but after reading this comprehensive and subtle study, you’ll likely be convinced that it’s been remarkably important. While discussing movies as famous as Raging Bull and as little-known as Iron Man (no, not that one; this one comes from 1931), Leger also introduces you to the finer points of genre criticism. The way he traces basic plot structures, key iconography, and historical patterns of change is a model of how thinking in genre terms can illuminate individual films.

Then there’s Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin. Ethan de Seife goes beyond the usual recounting of peculiar, often lewd gag moments to treat Tashlin as not only a gifted director but a representative figure in 1940s-1950s American cinema. Ethan traces how Tashlin became a program-picture director who never acquired the status of auteur, at least in the eyes of the studio system. The book situates Tashlin in the context of the Hollywood industry, both the cartoon shops (Tashlin did animation work for both Disney and Warners, among others) and the live-action production units. There’s as well a fascinating chapter on Tashlin’s influence on directors as different as Joe Dante and Jean-Luc Godard, who coined the adjective “Tashlinesque.” A blend of critical analysis, cultural commentary, and industry history, Tashlinesque is surely the definitive book on this cheerfully dirty-minded moviemaker. Ethan maintains a lively blog here.

Not strictly about cinema, but a book that’s indispensible for film researchers, is James Cortada’s History Hunting: A Guide for Fellow Adventurers. A founding member of the Irvington Way Institute, Jim is at once an IT guru, a historian of computer technology, and a scholar of Spanish history, particularly of the Civil War. History Hunting, the fruit of forty years of spelunking in archives, museums, and the world at large, is an enjoyable handbook on doing historical research. It ranges from help with genealogy (case study: the colorful Cortadas, from Spain to the US) to suggestions about how to frame a doctoral thesis. Jim reminds us that the historian must turn into an archivist: the materials you collect are documents for future historians to use. You are, to use the new buzzword, a curator. Jim provides a welter of practical suggestions along with his own tales of the hunt. Jim devotes part of a chapter to Kristin and me, which just goes to show his impeccable taste in neighbors.

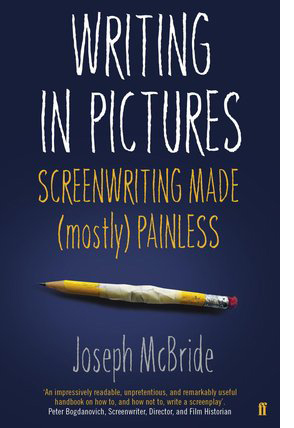

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

One of the most original aspects of Writing in Pictures is Joe’s emphasis on adaptation. This is sensible because (a) a great many films are adapted from other sources (today, even comic books); (b) a professional screenwriter is often called upon to reshape an earlier script draft by another writer; and (c) adapting a preexisting source swiftly gets the novice screenwriter thinking about the relative strengths of verbal and visual storytelling. Joe takes us through the script-building process step by step, each time reworking London’s story “To Build a Fire.” Somewhat like the European “conservatory” approach to film education, McBride’s emphasis on organic interaction with classic traditions is something new, even radical, in the world of American screenplay education.

Then there’s Film and Risk, edited by the boundlessly prolific and enthusiastic Mette Hjort. Probably the most conceptually bold cinema book of the year, it assembles several scholars and filmmakers to assess how films and filmmakers deal with risk. The subject is of course broad. There’s risk in performance; risk in breaking stylistic boundaries; risk within film institutions (such as producing); risk in social and political contexts such as facing censorship; environmental risks, as in the costs that filmmaking exacts from the natural world; and even the risks of viewing movies—exposing yourself to horrifying or depressing stories and images. Film scholars like Hjort, Paisley Livingston, and Jinhee Choi mingle with film producers and industry observers to reflect on how cinema takes chances.

Our colleague J. J. Murphy has been researching and teaching the films of Andy Warhol for years, and today–literally, today–his monograph The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol comes out from the University of California Press. This is the most comprehensive, in-depth study of Warhol’s filmmaking that has ever been published, and of course a must-have for anyone interested in experimental film or the American art scene.

The ideas are fresh, especially the explorations of Warhol’s debt to psychodrama. At the same time, The Black Hole of the Camera clears away many misconceptions about Warhol (no, Sleep and Empire are not single-shot films) while also offering detailed information about and analysis of little-known stunners like Outer and Inner Space. There are several pages of color frames, which remind you that Warhol was as good at color as Tashlin was. JJ maintains a remarkable blog on independent cinema and is a leading figure in the Screenwriting Research Network.

Not a book, but a publication of great value: Three major researchers have collaborated on a cogent, nontechnical review of experimental investigations into film perception. All of the authors have had face time on this site. Dan Levin has executed breakthrough experiments on “change blindness”–how we miss discontinuities and anomalies in everyday life. (On another dimension, Dan’s film Filthy Theatre is coming up at our Wisconsin Film Festival.) James Cutting, a venerable figure in visual perception research, has ranged across many key areas in his consideration of cinema. He also wrote a wonderful book, available free here, on Impressionist painting. And Tim Smith, virtuoso eye-tracker, is author of one of our all-time most popular blog entries, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.”

With three top talents, you’d expect the collaborative paper to be a triumph of synthesis, and so it is. It supplies the best case I know for why we cinephiles should welcome psychologists who test the ways we watch movies. It should be required reading in every film theory course in the land. Access to the published paper requires a purchase or a library subscription, but you can read the preprint version here. Check in at Tim’s blog Continuity Boy for plenty of videos exploring his research (DB).

Finally, we’re sometimes asked why we don’t allow comments on our blog. The simple answer is that we’re not nearly as good at responding to comments as John Cleese is.

The cover of Joe McBride’s book pictured above is from the Faber & Faber edition, which makes a better still than the US edition from Vintage. Same good stuff inside, though.

John Ford and the CITIZEN KANE assumption

Kristin here:

A few days ago I was reading the February 24 issue of Entertainment Weekly. I started subscribing to EW during the days when I was working on The Frodo Franchise. Being a Time Warner publication, it tended to feature The Lord of the Rings a lot (Time Warner also owns New Line Cinema). I was trying to keep track of the popular-press coverage of the film, and EW was a helpful source. It also used to be a bit more substantive in those days. In recent years it has become more fluffy. Still, it’s handy for reading over lunch or when brushing one’s teeth.

Turning to page 66, I found Chris Nashawaty’s “The Most Overrated Best Picture Winners.” The double-page spread was slathered with photos of My Fair Lady, Out of Africa, Gandhi, The King’s Speech, and Shakespeare in Love. (The piece is online, but as a gallery rather than an article, lacking the introduction.)

I like putdowns of overrated and/or over-rewarded films as much as anyone, so I settled in to read. I was shocked, however, to find that the first film on the list was How Green Was My Valley.

I happen to think the How Green is one of the very greatest American films. Probably no Best Picture winner in the history of the Oscars has been a more fitting recipient of that award. Why lump it in with Shakespeare in Love?! (I think you know what’s coming.)

Nashawaty gives his reasons. He admits that How Green has three pluses going for it: “It’s got beautiful cinematography, John Ford as a director, and a three-hankie plot about a Welsh mining village.” He goes on: “The minuses: mismatched accents and the still-outrageous fact that it beat Citizen Kane.”

Mismatched accents as a reason not to win Best Picture? The notion belittles the brilliant ensemble acting in Ford’s film, with Donald Crisp, Sarah Allgood, Barry Fitzgerald, Maureen O’Hara, Walter Pigeon, and many others giving fabulous performances, career bests in some cases. It is a joy to watch them interact. Of course most of these people sound more Irish than Welsh, but frankly, who cares?

By the way, I’m assuming Nashawaty means the mismatch of Irish accents to a Welsh setting, not a miscellany of accents among the cast, which is common in Hollywood films. Besides, isn’t accuracy of accents—think Meryl Streep—one of the criteria used to judge the very Oscar-winners that Nashawaty is decrying? I’ve never seen Gandhi, but I’ll bet Ben Kingsley did a heck of an authentic accent. Accents are one of the easiest aspects of performances to notice, so it’s not surprising that they are so often a factor in Oscar-nominated and -winning roles.

But it’s not really the accents that bother people about How Green. No, it’s really the “beat Citizen Kane” part that grates on film fans. Quite possibly it has led them to dismiss or undervalue one of Ford’s greatest films.

I’m going to be heretical and say that How Green deserved to win over Kane.

For years Kane has been sitting atop many lists of the greatest films of all times, including polls of professional film critics. The notion that Kane really is the greatest film of all time has become so engrained that people seem seldom to question it. Back when that idea arose, critics were unaware of the films of Yasujiro Ozu, probably the world’s greatest film director to date. Play Time was for years ignored and only recently has begun to be recognized for the masterpiece it is. With the rise of film restoration in the 1970s and the spread of film festivals and retrospectives, we now know vastly more about world cinema than we did before. Yet Kane has settled into its top slot for many people, including entertainment journalists. I can think of many films I would rank above Kane.

No doubt it’s a great film, with a marvelously tricky plot, another great ensemble of actors, splendidly distinctive cinematography, and innovative special effects masquerading as cinematography. It was hugely influential at the time and remains so to this day. Of course, Welles has declared time and again that he learned filmmaking by watching Stagecoach over and over, so Kane would probably not be as good as it is without Ford’s influence. Not that such influence proves that How Green is better than Kane, but it shows Welles’s respect for Ford. More on that below.

Middlebrow and proud of it

I think another reason why How Green tends to be dismissed as merely the film that cheated Kane out of its best-picture Oscar is that it is resolutely middlebrow. Indeed, in that way it fits in with all the other films Nashawaty writes about. They’re all resolutely middlebrow, too. Middlebrow films are for those people who look down upon popular genres and want to feel they’re seeing something worthwhile.

Despite this attitude, most of the great American films fit into popular genres: Keaton’s The General (or substitute your favorite Keaton film), Kelly and Donen’s Singin’ in the Rain, and Hitchcock’s Rear Window (or, if you will, Shadow of a Doubt or Notorious or Psycho). This is one thing that the auteur theory, somewhat indirectly, taught us. Howard Hawks’s modern reputation rests partly on his ability to waltz into any American genre and make one of its best entries. The Godfather is technically a gangster film, but one could argue that by taking it from a bestseller and making it into a glossy A picture, Coppola pushed his film into the middlebrow range far enough for the Academy to dub it Best Picture—twice. The one Best-Picture winner of recent decades that arguably did thoroughly deserve the prize was a serial-killer thriller, The Silence of the Lambs. I think a lot of people were surprised that the strait-laced Academy members could accept such subject matter in a nominee, let alone a winner.

Like Hawks, Ford moved easily among genres and excelled at least once in every one he touched. He made arguably the greatest war film ever, the underrated They Were Expendable, and the greatest Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (or Stagecoach or My Darling Clementine). He also pulled the turgid middlebrow genre of the 1930s biopic into greatness with Young Mister Lincoln. There’s no doubt that Ford was an uneven director, and arguably his worst films arose from his attempts to go for middlebrow respectability. The Fugitive is almost unwatchable in its pretentiousness, and the mid-1930s brought forth such items as Mary of Scotland and The Informer. But starting in 1939, he produced an almost unbroken string of masterpieces and near masterpieces, culminating in They Were Expendable and My Darling Clementine.

We should recall also that Welles himself adapted a middlebrow bestseller for the film he made directly after Kane: The Magnificent Ambersons. Had the studio not meddled so extensively with it, it probably would have been one of the American cinema’s great middlebrow classics, fit to sit alongside How Green.

Earned sentimentality

Welles himself probably would have felt honored by that comparison. In a 1967 interview he described his taste in films:

Old masters—by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. With Ford at his best, you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in a real world—even though it may have been written by Mother Machree.

In other words, Welles recognized that sentiment did not take away from the brilliance of Ford’s best work, and How Green is definitely in that category. Welles was too big an egotist not to have been annoyed at losing the Best Picture award to Ford, but he probably understood why How Green won better than most people do today. Today, apart from groups of women who go to see heartwarming female-oriented fare, audiences tend to shy away from sentimentality.

To his credit, Nashawaty lists sentimentality as a plus for How Green. (“Three-hankie plot” has a dismissive ring to it, but I’ll chalk that up to the requirements of infotainment journalese.) But I’m sure that many people who underrate How Green do so because it’s essentially a family melodrama where everything starts out in an Edenic state and the situation slowly goes downhill to a distinctly unhappy ending for all concerned. A lot of people simply dismiss sentimentality in all its manifestations, presumably as too naive, hitting us below the belt for an easy emotional appeal. In this day and age, it is much easier to admire cynicism than unembarrassed emotion. Despite its subject matter of environmental depredation by greedy companies, How Green is resolutely focused on the joys and sorrows of the family. Kane is cynical in a very modern way. Yet I cannot believe that we care nearly as much about the characters in Kane, even Susan, as we do in How Green.

Sentimentality is not a bad thing in itself. Sure, it’s an easy thing to evoke. Easy sentimentality is banal and cloying because there’s so little underpinning it except conventional romance and cute babies and long-suffering mothers and the like. Then there is what I call earned sentimentality. (A similar distinction is often made between sentiment and sentimentality.) Films with this quality are rich with original characters and situations that might make even a viewer who dismisses easy sentimentality pull out a hankie. The sentimentality in Chaplin’s films sometimes achieves this, and his Little Tramp character has been widely praised over the decades for his mastery of this emotion. Even those who dismiss sentimentality can forgive Chaplin, since humor usually undercuts the cloying quality just a bit. In a less obvious way, Harold Lloyd sometimes proves himself a master of sentimentality, as in The Kid Brother. And earned sentiment is not dead. It pervades Big Fish, another film that has been underrated or at least largely forgotten, perhaps in part due to its sentimentality. It has eccentrics galore and an original plot idea, but it doesn’t have that edgy, weird quality that sophisticated viewers treasure in Tim Burton’s work. There’s even sentimentality in the Wallace & Gromit films, though again humor makes the emotion palatable. Art cinema has its own sentimental masterpieces: Bicycle Thieves, Jules et Jim, Tokyo Story, Sansho the Bailiff, Distant Voices, Still Lives, and the list could go on and on. True, all these films are grimmer in part or in whole than the average Hollywood film, but so is How Green.

By the way, Welles himself delivers one of the sublime sentimental passages of world literature in the heartbreakingly nostalgic “chimes at midnight” speech in Falstaff, which has other passages of the same emotion. The Magnificent Ambersons is a sentimental film of a different sort.

For my money, How Green earns its sentimentality as well as any film ever made.

On everyone’s syllabus

You may be asking at this point, if How Green is so fantastic, why didn’t Bordwell and Thompson use it as their central example of a narrative film in Film Art? Why is Kane in that spot? There’s a simple answer to that: Kane is a very teachable film, and How Green, to say the least, is not. Our challenge was to find a film that most teachers used, or would happily start to use, and that demonstrated many concepts about film narrative and style that we wanted to describe.

Some films are just more teachable than others. They use a lot of different techniques, both stylistic and formal, in a way that students can notice. Hitchcock is probably the most teachable director overall, and I would bet that his films show up on introductory-film-class syllabi more often than any other director’s. It’s just that with Hitchcock, there’s no one film that’s self-evidently more useful for teachers than others. I sometimes think that one could almost write an entire introductory textbook using nothing but examples from Lang’s M. There are other classics like that. But Kane beats them all: a complex but clear flashback structure, obvious and varied technique, a complex soundtrack born of Welles’s radio experience, and examples of many things teachers want their students to learn about. It’s a classical Hollywood film, but it has touches of art-cinema ambiguity about it. It’s entertaining, at least to motivated students, so they’re likely to pay attention rather than dismissing it. They may come into the class knowing that it’s a revered classic and hence be interested in seeing it. It may even reconcile them to watching black-and-white films.

How Green, however, is difficult to teach. David has found this to be true. Our colleague Lea Jacobs occasionally offers a seminar on Ford, and How Green is among the most challenging films by a director whom students tend to be slow to warm up to. She attributes this partly to changing tastes and partly to the subtlety of the style of its cinematography. It’s very hard to make students, and indeed almost anyone who isn’t already a believer, see why How Green is a masterpiece.

Kane is not only teachable, but it’s highly conducive to analysis, and no doubt these two traits are closely related. David’s first widely seen article was a study of Kane, and I wrote the sections of chapters in Film Art dealing with it. I don’t mean that it’s simple; Kane is a complex film that has provided material for many different essays and books. But How Green has so many ineffable qualities that it resists cold, precise analysis. It has been one of my favorite films for over three decades, and occasionally I have contemplated writing something in-depth about it. I can’t, however, think what one could possibly write. One would just have to throw up one’s hands and say, “You either get it or you don’t.”

It reminds me of when I was nearing the end of my undergraduate career. I didn’t “get” Godard. I found his work pretentious and boring. But given how many people whose opinions I respected admired Godard, I persisted. I think I suffered through seven features, and at about number eight (Weekend), I got Godard. Maybe Ford, at least for his non-Western films, is somewhat the same sort of challenge. I’ve written analyses of two of Godard’s more difficult films, Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie). I’m still scared to try to deal with How Green.

(Stagecoach is much easier. For several editions of Film Art we included an analysis of it, which I wrote. Eventually it got replaced, but it’s still available here.)

A few hints

Since I doubt I will ever thoroughly analyze How Green, here I’ll offer just a few hints as to why it deserved to take home Best Picture and leave Kane an also-ran.

Nashawaty mentions the beautiful cinematography. Arthur C. Miller was 20th Century-Fox’s A-list cinematographer, having shot some of the Shirley Temple films in the 1930s, films that kept the studio afloat during the Depression. He teamed with Ford only on Tobacco Road and How Green, though he apparently helped with Young Mr. Lincoln uncredited. Miller won his first Oscar for How Green, his second for Henry King’s The Song of Bernadette (the main virtue of which is it looks a lot like How Green), and his third for Anna and the King of Siam. Few of Miller’s non-Ford films like The Ox-Bow Incident and Gentlemen’s Agreement are watched much today. He did lens somewhat minor films by major directors (Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, Preminger’s Whirlpool), but he is less famous than he deserves.

Just a few examples. How Green contains some of the same techniques that are so admired in Kane, but in a less flamboyant fashion. Deep focus, for example:

Admittedly, the people at the right rear are slightly out of focus, but the shot was done in-camera. No special effects.

The interiors of How Green have a distinctive touch: patches of light on the ceilings. Implausible, when you start to think about where the light must be coming from, but beautiful nonetheless. Miller (or at least Fox) almost had a patent on this way of lighting a room. With Kane getting so much credit for adding ceilings to sets, we should remember that Ford has done so in Stagecoach and does it here as well. It’s not as in-your-face as Kane’s ceilings, but it’s an example of the subtlety that pervades How Green. The first shot (below) is part of the series of scenes at the beginning setting up the happy home life of the large and relatively prosperous Morgan family; the father is about to dole out allowances to his sons on payday. The second comes much later, as the last two grown sons prepare to depart abroad in search of work after the mine has declined.

Kane is admired for both its long takes and its dynamic editing. Ford seldom used either. He held a shot long enough to be effective but not long enough to turn into showing-off. Take the scene after Angharad’s marriage to the wealthy mine-owner’s son. Mr. Gruffydd, the minister whom she actually loves, has performed the ceremony. As has been pointed out many times, Ford filmed the final shot without doing any close views to be cut in later. (Indeed, most of How Green was edited in the camera by Ford, so that most of the footage he shot ended up on the final version. It was his way of keeping control over his film.) By happy accident, a breeze caught Angharad’s veil, sending it soaring and twisting through the shot. Perhaps it was a reflex gesture on the part of the actor playing the mine-owner’s son, but he reaches out and holds the veil down as his bride climbs into the coach; it perfectly captures his cold, proper nature. For a split second before the coach pulls away out right, Angharad glances back toward the church, where Gruffydd remains inside. Once the coach is gone, Ford holds, and Gruffydd appears on the hillside at the rear, watching and then turning to go inside. No cut-in mars the perfection of the shot.

There’s one of the hankie moments. I get tears in my eyes during this scene, partly out of sympathy of the sundered couple and partly from aesthetic pleasure. If ever there was a single shot that exemplifies Ford’s combination of sentiment and discretion, this is it.

The last of these five frames belongs to the visual motif that appears in the opening sequence, as Angharad waves to her father and Huw on the beautiful distant hillside (see above), as well as in the final scene, where Angharad struggles in her fine clothes across a similar hillside, swathed in smoke, to reach the mine after the disaster that traps her father (see below). Such moments create a quiet measure of the gradual degradation of the valley and the dwindling of the family’s happiness.

Did Ford realize how brilliant this shot was? We can be confident that Welles was well aware of how daring and wonderful his techniques in Kane were. It shows in the film. With Ford, one can only suspect that he knew exactly what he had accomplished here and elsewhere.

Another thing How Green shares with Kane is a flashback structure. It largely consists of one big flashback told by the protagonist, not a series of embedded stories by witnesses. Nevertheless it’s unusual, since we never come out of the flashback. The tale opens with the valley in severe decline, the village nearly deserted, and the hero about to depart for a better life. We witness the decline of his family as he grows, gets educated, and opts to follow his father and brothers into a job in the mine. By the end his elder brothers have scattered all over the world, his father is dead, and we don’t know what has become of his mother and sister. (One plausible assumption is that his mother has recently died, prompting his departure in the opening scene.) Yet the ending gives us a series of shots of the family as they had been in their prime, with the protagonist-narrator declaring, “Men like my father can never die.” Like Kane, it is a film about the power of memory, but in this case the power to comfort rather than to baffle.

One thing that makes How Green stand apart from some of Ford’s other films is that it for once controls the director’s penchant for mixing in broad humor. His stable of supporting actors playing minor characters who love to drink and fight can be trying. There is a particularly ill-advised moment in The Searchers when, after the epiphanic moment when Ethan has lifted Debbie as if to kill her and then embraced her, Ford cuts to the Ward Bond character having a wound on his posterior dressed, to the derision of his comrades. That Ford should undercut such a scene with a vulgar moment of comedy combines with another flaw or two in the film keep if off my list of Ford’s very best films. And much though I love the first three-quarters of The Quiet Man, that climactic brawl just goes on and on.

In How Green, the characters Dai Bando and Cyfartha provide humor, but they are held in check. They play reasonably significant roles in the action, helping Huw deal with the school bullies and his sadistic teacher. Many of the family scenes involve amusing moments as well, moments that arise naturally from the situations and have no air of mere comic relief. In screenwriter Philip Dunne’s introduction to the published version of his screenplay, he finds fault with several scenes and actors. Maybe he’s right that the scene when the mine owner visits the Morgan family is played for broad comedy, but it’s not as broad as elsewhere in Ford’s work. Luckily Ford’s brother Francis does not return for yet another of his bit parts as a drunk.

In 1972, when Ford was dying of cancer, the Directors Guild held an evening gathering to honor him. He was asked to choose one of his films to be projected, and he named How Green. He had consistently said he considered it his finest film.

There’s no budging Kane

I doubt that the notion of Citizen Kane as the Greatest Film of All Time will go away anytime soon. Changing (and unchanging) tastes are reflected in the decadal Sight & Sound poll of critics concerning the ten greatest films of all times. They started in 1952 and have continued to 2002, with another due this year. The lists reflect the fact that apparently critics can somewhat agree on the greatest older classic, though fashions in these come and go, but they cannot agree on much of anything that has been made since 1970:

1952

- 1. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 2. City Lights (Chaplin)

- 2. The Gold Rush (Chaplin)

- 4. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 5. Intolerance (Griffith)

- 5. Louisiana Story (Flaherty)

- 7. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 7. Le Jour se lève (Carné)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 10. Brief Encounter (Lean)

- 10. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

1962

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 3. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 4. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 4. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 7. Ivan the Terrible (Eisenstein)

- 9. La terra trema (Visconti)

- 10. L’Atalante (Vigo)

1972

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 4. 8½ (Fellini)

- 5. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 5. Persona (Bergman)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 8. The General (Keaton)

- 8. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 10. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 10. Wild Strawberries (Bergman)

1982

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Seven Samurai (Kurosawa)

- 3. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly, Donen)

- 5. 8½ (Fellini)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 7. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 7. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 10. The General (Keaton)

- 10. The Searchers (Ford)

1992

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 4. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 5. The Searchers (Ford)

- 6. L’Atalante (Vigo)

- 6. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 6. Pather Panchali (Ray)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 10. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

2002

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 3. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 4. The Godfather, parts I and II (Coppola)

- 5. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

- 7. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Sunrise (Murnau)

- 9. 8 ½ (Fellini)

- 10. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donen)

There is much that could be said about these lists. Most readers will probably be astonished to see Bicycle Thieves at the head of the first list, with Kane not even present. Brief Encounter above La Regle du jeu. Louisiana Story, of all things, and Le Jour se léve. By 1962, tastes had changed. Italians won the day, with three films, while Eisenstein, whose Ivan the Terrible, Part 2 had finally been released in 1957, had two films chosen. Two French films and two American. But it was in this year that Kane appeared, immediately bouncing to number one, a position from which it has never budged. I suspect it will sit atop the 2012 list, simply because now so many critics assume it’s the best film ever–and even if they don’t assume that, they won’t be able to agree on an alternative.

Ford has had only one film on the lists, The Searchers, in 1982 and 1992. For a time it was the Ford film du jour, until in 1992 Hitchcock zipped past it with Vertigo, which settled into the second spot after Kane in 2002. Mizoguchi has been on only one list, in 1972 with Ugetsu Monogatari. Ozu’s first film to became well known in the west didn’t make the list until decades later, in 1992, and yet despite the discovery of Late Spring and Early Summer and An Autumn Afternoon, Tokyo Story remains the Ozu film. Tati has never appeared on the list. Neither has Bresson. I’ll buy the idea that critics are out there voting for Bresson like mad, but all for different films. But Play Time, surely one of the very greatest films ever made, should be easy to converge around. Finally, the only post-1970 film on here (and not by much) is the Godfather pair. I was still working on my master’s degree when the first one came out.

I suppose by now, with so many smaller countries starting to make movies and so many festivals making them widely available, it becomes impossible to anoint new classics in the way critics used to. Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy, in whole or in part, would seem to be such a classic, but there are so many great competing films. Does one have enough perspective to choose more recent films when others, like Sunrise, have stood the test of time? Play Time is 45 years old now, and I think it’s a greater film than most of those on the 2002 list–certainly including the number one. Possibly it will make the list this year.

Why is Kane so fixed at the top, when other films move up and down and ladder, and some appear and disappear? Perhaps the simple assumption that if it has been up there so long, it must really be the greatest film ever made.

I think this business of polls and lists for the greatest films of all times would be much more interesting if each film could only appear once. Having gained the honor of being on the list, each title could be retired, and a whole new set concocted ten years later. The point of such lists, if there is one, is presumably to introduce people who are interested in good films to new ones they may not have seen or even known about.

Such an approach is not wholly unthinkable. Each year the National Film Registry maintained by the Library of Congress chooses 25 films deemed to be national treasures worthy of special priority in preservation. There’s probably some assumption that the best films were on the early lists and that each new 25, especially coming annually rather than at longer intervals, must be of less interest than its predecessors. But on the whole it’s a pretty egalitarian exercise, one that treats all kinds of films as fair game, not just fiction features, and it really does draw attention to obscure films that deserve to be better known. Given how many films have been made in the USA, it will be a long time before the Registry is scraping the bottom of the cinematic barrel. The entire world could supply so many more.

At any rate, I don’t insist that justice will not be done until How Green or some comparable Ford masterpiece appears on Sight & Sound‘s poll, any more than I would say that it’s having won the Best Picture Oscar proves that it’s a great film. I think we all know that the whims of the Academy members are hard to fathom, then and perhaps even more so now. But why call it overrated just because it beat Kane for that dubious honor? If anything, How Green is underrated for that very reason. Had it been made in a different year and won the Oscar against some other films that weren’t Kane, would it be any better or worse?

If you have never seen How Green and are not wholly opposed to earned sentimentality, give it a try. Just make sure you have at least three hankies handy.

PS March 8, 2012. Our friend Antti Alanen points out that Maureen O’Hara said the shot with the veil was carefully planned. She disagrees with Philip Dunne’s claim that the wind catching it was a happy accident, as Joseph McBride recounts in Searching for John Ford:

Dunne thought Ford had “one of the greatest strokes of luck a director ever had” when the wedding veil suddenly caught a gust of wind and billowed behind Mareen O’Hara as she walked down the steps from the church. O’Hara recalled, “Everybody said, ‘Oh, that Ford luck! How wonderful that was! What an effect it has!’ Rubbish! It wasn’t ‘Ford luck.’ It was three wind machines placed by John Ford, and I had to walk up and down those steps many times while he worked out that the wind machine would do exactly that.” As she climbs into the carriage, the ator playing her husband, Marten Lamont, reaches out to catch her veil. Dunne thought, “The man shouldn’t have touched it when the veil spiraled up. My God, what a shot! Luckily, Joe LaShelle, who was the operator, just gave it a little tilt with the camera.” I told Dunne I thought the gesture of restraining the veil (probably planned by Ford, like the rest of this meticulously composed shot) is an eloquent metaphor for the repressiveness of Angharad’s loveless marriage. “Well, I guess so,” the screenwriter responded. “I didn’t think beyond that. I said, ‘My God, you get a break like that, you leave it alone.'” (p. 332)

PPS March 11, 2012. Thanks to Przemek Kantyka for pointing out that Ugetsu actually figured on the 1962 and 1972 lists.