Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

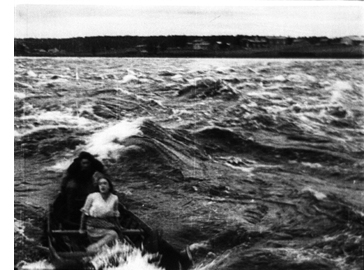

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

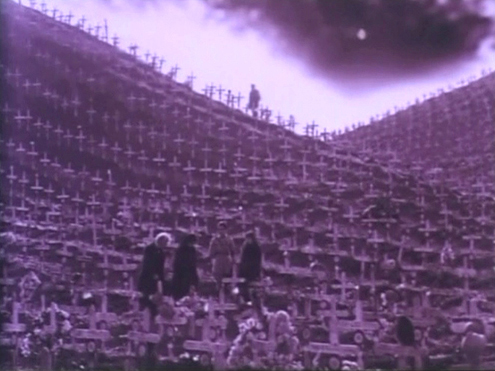

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

Dante’s cheerful purgatorio

Twilight Zone: The Movie.

DB here:

When will we baby boomers relax our chokehold on popular culture? Never, if the enthusiastic response to Joe Dante’s visit to Madison last weekend is any indication. A showing of Gremlins (1984) packed the house. A screening of his Twilight Zone: The Movie episode brought fans forward with DVD slipcases to sign. College kids reminisced about watching The ‘burbs with their dads and Explorers with their buddies (all on video, of course).

Although steeped in classical Hollywood, intimately acquainted with the most obscure output of the studios, Dante hasn’t abandoned the present. He shoots TV shows, webisodes, and the 3D feature The Hole (still awaiting a US release). He hosts a website, Trailers from Hell, in which directors comment on other directors’ works using a trailer as a point of departure.

His films, from Piranha (1978) and The Howling (1981) to the present, by way of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) and Matinee (1993), combine the gonzo spirit of the 1960s with a good-natured reverence for the past. Particularly movies. Particularly crazed, tasteless movies. Like Spielberg and Peter Jackson, he’s a fanboy. “Most filmmakers are kids at heart,” he says. “And all actors are.”

Unlike Spielberg and Jackson, though, Dante keeps politics close to the surface. His films sustain the baby-boomer hope that you can squeeze cultural critique into a genre project. Everybody knows that the Gremlins movies are subversive trips into the shadows of bourgeois normalcy. Has a shiny kitchen blender ever been used more efficiently?

The Gremlins pictures and The ‘burbs are valentines compared to Homecoming, Dante’s installment in the series Masters of Horror. This asks a simple question: Suppose that all the soldiers killed in combat were able to come back and vote? Is that a powerful lobbying group or what? When resurrected vets of Iraq start stalking to the polls, an Ann Coulter lookalike tries to stop them. Run on cable in 2005, this left-wing zombie movie slashes to ribbons pious platitudes about war’s costs. It’s required viewing for all 2012 presidential candidates.

Don’t crowd me, Joe

Dante began his career as a collagist. That’s not too fancy a name for a man who, with his friend Jon Davison, collected the ephemera of the great age of 16mm. TV shows, ads, and movie trailers swept out of local stations went into their archives. In time these and other glories of late-night TV found a new life, like a monster stitched together out of morgue remains. The strategy was simple. Dante and Davison rented five or six 16mm sub-B features and projected stretches of them, in rough order but jumbled together. The movies were interspersed with reels of clips.

The Movie Orgy played college campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Orgy lasted about seven hours, and its auteurs urged viewers to drift in and out. “Go get a pizza whenever you want. You won’t miss a thing.” Eventually Schlitz hired them to take it around the country and sold beer at the screenings.

When Dante began working for Roger Corman’s company—cutting trailers, thereby tapping his skills as a collage-maker—The Orgy was suspended. But some years ago the footage that he could find was transferred to digital and played at the New Beverly. It found a new success. Dennis Cozzallo has a lively tribute from 2008 here. Needless to say, we had to have The Orgy for Dante’s visit to Madison.

Affection for the detritus of the media takes many forms. After watching too many campus simpletons (both students and profs) laugh mockingly at Fritz Lang and John Woo movies, I’m opposed to condescension. I suspect Camp in its disdainful form. I don’t like people demonstrating their sense of superiority to the trash their parents and grandparents enjoyed. Knowingness leaves you with nothing.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

Moreover, in sequence after sequence, there’s a quality of astonishment that doesn’t make us feel superior. Take one exemplary moment of dépaysment. If you and I tried to be naive or trashy, we couldn’t come up with this.

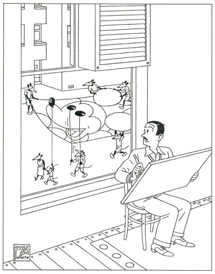

Andy Devine hosted a kiddie TV show, Andy’s Gang, which featured Froggy the Gremlin (Plunk your magic twanger, Froggie!), the cat Midnight, and Squeeky the mouse (played by a hamster). About an hour into The Orgy, Andy induces Midnight to play a miniature pipe organ while Squeeky accompanies him. Cut to a deep-focus shot of what seems to be a slightly drugged cat locked in place and rhythmically pawing the offscreen keyboard. In the background Squeeky, apparently clamped within a mechanical mouse body, bangs a tiny bass drum. Andy sings along tunelessly. The song is “Jesus Loves Me.”

You don’t laugh, you gape. It’s like one of our local attractions, The House on the Rock: What’s disturbing is not that it’s done poorly, but that somebody thought of doing it at all.

The form of The Orgy—and it does have a form, of sorts—is to open with openings and end with endings. Several of the movies get started in the first half hour (Dante and Davison love opening credits) and we’re given enough of the plots to become curious. Most prominent are Attack of the 50-Foot Woman and Speed Crazy, the latter receiving a loving dissection highlighting, and repeating to the point of obsession the heel protagonist’s tagline, “Don’t crowd me, Joe.” Eventually the guy and his flashy sports car wind up crowded, all right–crowded into a ravine.

More TV episodes and movies get added as the hours roll by, and by the end we’re facing Armageddon. Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, New York, DC—every major city is under attack by some alien or giant monster. Sky King has to dump dynamite for some reason, Superman has to save Lois from a pistolero. A sort of amphetamine Intolerance, The Movie Orgy cuts together all these climaxes, which include The End titles that are far, far from signaling the end.

The clip from Andy’s Gang reminds us that the piece is somewhat misnamed. It’s a Movies And TV Orgy. More specifically, it’s a Movies On TV orgy. The structure of the whole shebang imitates a long stretch of television ca. 1955-1960. Over lunch Dante recalled watching Million Dollar Movie as a kid in New Jersey, seeing a feature shoehorned into a ninety-minute slot and chopped up by commercials. The Orgy replicates the jagged tempo of switching among three or four channels, glimpsing variant commercials for Colgate toothpaste or Raleigh cigarettes, catching a bit of this movie and then a bit of that one. With all its kid shows from my youth (The Lone Ranger, Lassie, Mighty Mouse, etc.) in endless eruption and interruption, it’s a baby-boomer time capsule. Puncturing this evocation of childhood are the clips scavenged from teenpix and Dick Clark’s dance show, Vietnam, Nixon’s Checkers speech, and film-society icons like the Marx Brothers, Fields, and Abbott and Costello. The late sixties counterculture breathes more fully in some clever fake ad spots. In one, a crucifix starts to wobble as the carved Jesus struggles to free his hands.

Dante claims that he and Davison were inspired to find out about the popular culture that shaped their parents’ generation. But nearly everything we see filled the airwaves during our younger days as well. The Movie Orgy in its current form seems to me a zestful celebration of the world our generation saw when we flopped on our bellies, propped our chins in our hands, and stared at the tumultuous world inside a black-and-white (not color) TV (not video) set (not monitor).

We cartoon characters can have a wonderful life

Dante the collagist leaves his fingerprints all over another film he screened here. When Spielberg launched his Amblin company, he hunted for directors who could make family entertainment in a genre format. Dante, who had already started Gremlins, was invited onto the omnibus Twilight Zone project. After the fatal accident on the Landis set, the studio backed off and it become “a movie they wanted to make but didn’t want anything to do with.” This gave Dante wide latitude and made him think, mistakenly, that studio suits always leave directors alone.

For this episode, Dante wanted to do an original story but Warners insisted that it had to be based on an episode of the TV series. He went back to the original Jerome Bixby story, which Dante and Richard Matheson reworked to add cartoons as a running gloss to the comic horror. The pseudo-family of demonic little Anthony inhabits a house that is half cartoonland, half-PoMo-Caligari. Saturated colors, occasionally striped with noir shadows, provide another Dante caricature of family domesticity, but now cartoons comment on the action. When Helen steels herself to eat, the dog on the screen behind her is doing the same.

The crisscrossed shadows of the corridors are replayed in the sawtooth walls pursuing Bimbo.

The collage principle gets developed further in Dante’s use of the soundtrack. The Movie Orgy uses no new sound work; the clips are just spliced together. But for the Twilight Zone episode, let loose in Warners’ classic archive, Dante could weave in Carl Stalling music (reorchestrated for stereo by Jerry Goldsmith) and a rich mélange of daffy sound effects.

The TV is incessantly on. The cartoons running in the background supply whizzes, boinks, and thuds that jarringly punctuate the conversation between puzzled teacher Helen Foley and the family that Anthony holds in his magical grip. “This is Helen,” says Anthony, introducing her to Uncle Walt and his sister, as we hear a smash from the TV set. The cartoon tracks comment on the action too. As the family settle down in front of the tube, the elders dote on Helen and we hear a Stalling rendition of “Ain’t She Sweet?” Dinner is served to the tune of “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic.” And when Helen discovers her burger has been slathered with peanut butter, the visceral image is underscored by warbling winds that rise when she lifts the bun. Eisenstein, for reasons given here, would have loved the moment. The whole sequence plays out as live-action animation, with naturalistic dialogue and effects given a creepy overlay by the cartoon track. Is Helen Foley’s last name part of the gag?

Dante, impresario of the comic grotesque, finds his inspiration in popular culture, the more wacko and inept the better. The comedy may come from childhood silliness, the grotesque from childhood fears. They say we baby boomers will always be just big kids, and Dante accepts this with a grin and a darkly cheerful eye.

Many thanks to the resourceful Jim Healy for arranging his friend Joe Dante’s trip to Madison. Thanks as well to the Cinematheque, the Marquee, and the Chazen Museum of Art for hosting the screenings.

John Carradine in The Movie Orgy.

Play it again, Joan

“The happy heart loves the cliché.”

–Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) in Sudden Fear.

Sometimes your audience gets what you’re saying faster than you do. Years ago, after I gave a lecture in a class at Columbia University, a grad student came up and said: “What you’re doing is looking for the conventional side of unconventional films and the unconventional side of conventional films.” I’d say it’s not all I try to do, but the student’s chiasmus does capture a lot of what interests me.

It’s especially on target for Hollywood cinema. I don’t understand criticisms of Hollywood for not being realistic. It’s a highly stylized, artificial cinema, only a few notches above ballet or commedia dell’arte. Some of our best critics, like Parker Tyler and Manny Farber and Geoffrey O’Brien, have understood this. All the artifice will demand plenty of conventions, yes, but there are always filmmakers ready to treat them in fresh ways. And the churn is swift. American studio cinema is constantly finding new variations on its traditional forms, formats, and formulas.

Do-overs are allowed

Sleep, My Love

Take replays. The repeated sequence has become so common in our movies that nobody much notices it any more. We’re quite used to seeing an earlier action revisited. Often the replay simply serves to remind you of what happened, as when clues to a mystery are given in fragmentary flashbacks. The replay may also aim to get you absorbed in a character’s mental life. John, the hitman in John Woo’s The Killer, is traumatized by the fact that he blinded an innocent woman during a contract hit, and the moment of her wounding haunts him.

Sometimes, however, we get multiple-draft replays, in which the second version significantly alters the first. A common gambit is to have the second version show more of what happened, as in the money drop in Jackie Brown. Other cases show contradictions, as when conflicting testimony is dramatized in flashbacks. The most recent version I’ve seen occurs in The Debt, when the central 1966 section of the film concludes by showing what really happened when Dr. Vogel slashed Rachel and fled. In such cases the replay becomes less a true repetition and more of a revision, a new version questioning or canceling what we’ve seen before.

The idea isn’t new. You can find the replay in various forms in trial films of the 1930s, as I’ve discussed here. But the replay really came into its own during the 1940s. Directors and screenwriters experimented with the device as part of a broader initiative, burrowing into new niches in the ecosystem of classical narrative.

In those films, it’s common for replayed scenes to show an incident haunting the protagonist, as when the tormented bride of The Locket is assailed by memories as she walks down the aisle. Sometimes a flashback fills in information that was cunningly omitted from the earlier version, as in Mildred Pierce. And we also have competing accounts of what happened, as variant replays furnish multiple drafts. The most famous example is probably Crossfire.

By 1950, Joseph Mankiewicz could dream up one of the most daring experiments of the period, one that anticipated the repeated scene in Persona. For All about Eve, Mankiewicz planned to present Eve’s memorable monologue about the power of theatre twice: first through the sympathetic eyes of Karen (Celeste Holm), then from the perspective of the bitter Margo Channing (Bette Davis). What would viewers and other filmmakers have made of it? But Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck ordered the replay dropped, for reasons I speculate about in this entry’s codicil.

Mankiewicz’s unseen experiment with Eve’s “Audience Aria” reminds us that replays affect the soundtrack too. The most common use of replays is probably auditory, that line of dialogue that flits through a character’s consciousness—an auditory flashback, in effect. “Who knows what you may do the next time?” asks the sinister voice of the psychiatrist as Alison (Claudette Colbert) totters up the stairs in Sleep, My Love (1949). Several snatches of dialogue can flow together to recall a host of earlier scenes. In The Hard Way (1943), on another staircase, Katie (Joan Leslie) becomes distraught as bits of dialogue spoken by several characters flash through her mind.

More unusual is the audio replay in Duvivier’s wonderfully stylized Lydia (1941). A flashback to a ball is introduced by Lydia’s voice-over, recalling the splendid ballroom with its mirrorlike floors and the “divine aggregation of musicians, hundred of them, I think.”

But then her old lover corrects her memory and we get a flashback showing a more modest ballroom with a small ensemble.

Over these later shots, however, we hear bits of Lydia’s earlier description of the big ballroom and troops of musicians, in contrast to what we see. The sound flashback functions as a wry narrational commentary on Lydia’s stubborn romanticism.

Purely auditory replays tend to be subjective, but could we have an objective one? And can it promote surprise and suspense? As we say in Wisconsin, you bet. (Not you betcha.)

The replay machine

A lighthearted instance appears in The Pajama Game (1957). Sid Sorokin (John Raitt) , the new superintendant at the Sleeptite Pajama Factory, is falling in love with Babe Williams (Doris Day), the no-nonsense head of the labor union’s Grievance Committee. He sings into his Dictaphone about her in the song, “Hey, There (You with the Stars in Your Eyes).”

At the end of the song’s first section, he plays it back and then comments sourly on the lines he’s just sung. By the end, he’s joining himself in a duet, harmonizing nicely.

This instant playback wasn’t a cinematic invention, though. The same number, including the Dictaphone gimmick, was employed in the original Broadway production.

The Dictaphone, which used both wax cylinders and plastic belts for recording, was a popular device for businesses. Erle Stanley Gardner employed it for dictating many of his novels. A competitor to the Dictaphone was the SoundScriber, a late 1940s device using vinyl phonographic discs. The SoundScriber figures in a more sustained and suspenseful replay scene a few years before The Pajama Game.

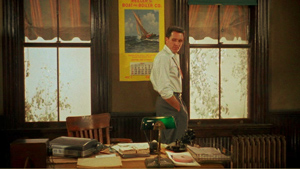

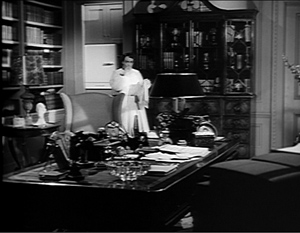

In Sudden Fear (1952), Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) is a prosperous playwright who has outfitted her office with a SoundScriber. She uses it for dictating plays and correspondence. One evening before a party, euphoric after her new marriage to the handsome actor Lester Blaine, she meets with her attorney to prepare a new will. He proffers a draft that assigns a modest sum to Lester, but she considers it insulting. She switches on the SoundScriber and dictates a new will, one leaving all her estate to Lester.

But we’ve had our suspicions about Lester, since he’s played by Jack Palance, an actor with more juts to his facial planes than a Giacometti bust. Our fears are confirmed after Lester hooks up with his old girlfriend Irene (Gloria Grahame). When they learn that Myra is making a new will, they believe she’s going to give the bulk of her estate to a foundation.

On the evening of the party, as she starts dictating her new will, the guests arrive and she descends to meet them. Irene and Lester slip away and meet in Myra’s study. Fade out on Lester closing the door.

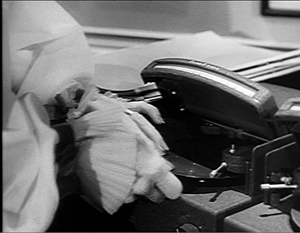

Next morning, Myra return to her study and discovers she left her SoundScriber on all night. She hits replay and listens to herself bequeathing all her money to Lester. This is the replay that launches the big action. As she’s about to switch off the machine, she hears the conversation starting between Lester and Irene. The microphone, left on accidentally, has picked up their plotting.

The couple is still under the false impression that the new will leaves Lester penniless. We hear him declare his contempt for Myra while caressing and embracing Irene. They start planning to kill her before she can sign the new will.

The SoundScriber scene gives us two plot developments, past and present, simultaneously. The recording fills in the gap left by the fade-out: Now we know what happened behind those closed doors. On the visual track, we can watch Myra’s developing anxiety about the couple’s murder plot but, more piercingly, we register her realization that Lester has never loved her.

Across seven minutes, Joan Crawford executes a carefully modulated solo performance, for the most part with no accompanying score. Meanwhile, Palance and Grahame get to act viva voce. And David Miller’s direction scales and times things nicely. I won’t try to analyze the very end of the scene, let alone its frenzied aftermath. I just want to trace the dynamics of the double-layered time scheme the replay machine gives us.

Joanie, more than shoulders

The recorded scene develops from the lovers’ frustration with keeping up a false front, then to their suspicion that Irene will cut Lester out of her will, then to the mistaken belief that she’s just done so, and finally to their decision to kill her. Myra’s playback scene proceeds, I think, in four stages as well. Myra starts out placid and almost giddy in her love for Lester. She’s abruptly shocked and disenchanted when she learns he doesn’t love her; her stomach churns. A third phase consists of her discovery that Lester and Irene intend to kill her, and she devolves into sheer panic. The last phase, of which I’ll show only a bit, initiates a search for a way to defend herself.

Myra comes in euphoric. As she replays her dictation of the night before, she strolls around her study, going far back to the distant refrigerator for a glass of milk and then coming forward. She seems to savor hearing again her own declaration of her devotion to Lester.

Myra’s circuit around her study isn’t just filler: it etablishes the rear area for use later. But now, as she’s about to turn off the recording, she hears Lester’s voice: “What’s up?” She backs up a little, bumping the desk as she realizes that there’s more on the disc. This recoil, as a performance decision, will get magnified in the course of the scene. Then Miller cuts to a reaction shot.

The first of several optical point-of-view shots gives us a close view of the twin SoundScriber units (good for product placement too). Myra has set the milk down on the console.

As we hear Lester venting his contempt for her, Myra’s eyes fill with tears. Worse, he adds that he’d like to tell her he never loved her for a moment. “I’d like to see her face.” He can’t, but we can; in the closest shot yet, she looks right at us. Hollywood can be brutal.

She turns away and, seen from a new angle by the desk, she advances toward us. On the track, Lester is pitching woo to Irene. Myra realizes that he lusts for this other woman. She sighs. Listen closely and you can hear her emit a soft whimper as well.

Another cut to the SoundScriber as Lester says he dreams of holding Irene: “I don’t know how I stand it, not being with you.” On these last few words, cut to Irene, turning away in shame.

She rushes back, having heard enough. A low angle shows her about to switch off the horrible recording when Irene is heard noticing the attorney’s draft of the will on the desk. “It’s the will!” Myra freezes, accentuating the line, and then starts to turn when Lester begins to read the draft.

Having hidden her face from us for a little while, Miller’s direction makes the next close view all the more powerful. (Note the eyebrow work.) Lester’s reaction to the will proves it’s been about the money all along. As he curses Myra, she doubles over grabbing her stomach. This, I take it, is the high point of the scene’s second phase–a sheerly physical reaction to Lester’s cynical betrayal of her love.

Phase three starts, I think, when Irene is heard purring, “Suppose she isn’t able to sign it on Monday.” The line is heard over a shot of the machine, and not a POV at that. The visual narration cunningly delays, by just a few seconds, Myra’s reaction to Irene’s hint. The cut shows her listening, stunned. Lester agrees with Irene. “I’d get it all! Why not?”

Myra turns, as if in disbelief, and a closer view of SoundScriber underscores Irene’s response: “Lester, I have a gun.”

This triggers the scene’s big movement: Myra’s retreat from the recording. Back to the extreme long shot, low angle, as she hurls herself toward the rear wall and sidles along toward the refrigerator, taking refuge behind the chair. The lovers discuss how to arrange an apparent accident, all the while kissing and declaring their love. Lester exclaims, “I’m crazy about you! I could break your bones!” as only Jack Palance could say it.

Again we get an optical POV shot, but now from Myra’s position across the room as Lester muses on “a nice little accident.” And in the cut back to Myra, we hear Irene say, “We’ll work something out. I know a way.” The recording needle is stuck in a groove, and we hear her say it again: “I know a way.” Music comes up for the first time, shifting the action to a new pitch.

I know a way. This mechanical glitch, I think, pushes fear into panic. The tightest close-up yet of the spinning disc is a sort of mental subjectivity: It’s not what Myra sees exactly, but an expression of her being riveted by insistent, maniacal repetition of Irene’s assurance: I know a way. Myra rushes out of the shot and hurls herself into the bathroom to vomit. All the while we hear, again and again: I know a way.

The couple’s plotting has driven Myra out of the room, as the music rises and nearly suppresses Irene’s “I know a way.” In a closer view of the bathroom, Myra staggers to the sink and splashes water on her face, while the record still spins and Irene’s voice taunts her.

But now we get the start of a new phase, with Myra trying to seize the initiative. In a burst of anger she rushes back to the machine, switches it off, and fumblingly takes out the disc. By the time she does so, we’ve heard Irene’s “I know a way” thirty-one times. Talk about hammering the audience.

Myra grips the disc, proof of the criminal conversation, and….

…But my analysis has gone on too long. It’s reasonable, although mean, to stop with the end of the replay. The rest of the sequence builds on what we’ve heard and seen, developing Myra’s efforts to defend herself.

I should note, though, that there follows a hallucinatory sequence in which we get not only perceptual subjectivity, like the POV shots, but also mental imagery and sounds as well. That sequence also includes auditory flashbacks of the usual sort, Myra’s anxious memories of things that Lester and Irene said on the SoundScriber recording. They’re replays of a replay, if you want to get fancy about it.

Conventioneering

In a way this scene is just a variant of a common storytelling convention: Someone accidentally overhears a key piece of information, in an adjacent room or over the phone. But the sequence shrewdly recasts this convention in ways that pay off on many dimensions. We get the suspense attached to the lovers’ mistaken belief that Myra will cut Lester out, and we get Myra’s reaction to it. That reaction is compounded of her sense of betrayal, her disillusion, and her realization that she’s in danger. Had she been eavesdropping on their conversation, she could have burst in on them and denounced their misreading of her will. As it is, she must helplessly listen to them unfold their plans.

After more than a decade of female Gothics–aka”woman in peril” movies, aka I-think-my-husband’s-trying-to-kill-me movies–from Suspicion and Gaslight to Woman in Hiding, Miller and his colleagues found a fresh way to put a lady in a cage. Schema and revision, a key process in the history of any art form, allows ingenious artists to remake what tradition hands them. Twenty years later, Francis Ford Coppola and Walter Murch would build an entire movie, The Conversation, around the audio replay and its possibilities for objectivity and subjectivity. Over and over, the unconventional burrows inside the conventional.

After this film, Joan Crawford became a spokesperson for SoundScriber. (See below.) Who would know better than she the advantages of the gadget? Perhaps Joan even had a stake in the firm. Such fruitful synergy wouldn’t be unknown in Hollywood. Jack Webb found the Teleprompter so useful in shooting Dragnet episodes that he invested in the company.

On All About Eve and Zanuck’s purging of the replay of Eve’s monologue: I suspect that it was a forced byproduct of another decision Zanuck had taken. The film consists largely of flashbacks, and Mankiewicz had intended to move through them by shifting from one character to another. At the awards dinner the flashbacks begin with Karen, and then another block of them, grounded in Margo’s memories, was to take up later episodes in Eve’s ascent to stardom.

But the film ran very long, so Zanuck cut the framing portion at the dinner that would have introduced Margo’s flashbacks. The result is that in Karen’s flashback, we occasionally hear Margo’s narration of certain episodes Karen didn’t witness. But once we’ve lost Margo’s narrating frame, then it becomes quite difficult to justify re-hearing Eve’s ruminations on theatre from anything approximating her point of view. I suspect that consistency of this sort played a role in Zanuck’s cutting Eve’s monologue. Plus it was a pretty daring move on Mankiewicz’s part. And the film is already pretty long. The fullest account of the changes, though still not as specific as I’d like, is in Sam Staggs’ All About All About Eve (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001), 170-172. As Staggs points out, Mankiewicz did work differential-viewpoint flashbacks into The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

Sudden Fear is available on a so-so DVD transfer from Kino Lorber.

The interplay between film and fiction in the 1940s is fascinating, and we can sometimes find rough equivalents between techniques. Here is a stream of auditory flashbacks in Steve Fisher’s novel I Wake Up Screaming (1941), ending with the protagonist’s inner monologue.

I’d remember Lanny Craig saying: “They crucified me . . . it was because of Vicky Lynn!” And the night Robin Ray said: “She’d laugh, see, and it was like Guy Lombardo’s band playing.” And Hurd Evans: “I only get two hundred and fifty a week.” Tick-tock, the faceless clock on Sunset. “It’s possible to build a case out of nothing,” the assistant district attorney said. Where was Harry Williams? If he’d been murdered, where was his body?

By the end of the thirties, of course, such montages were already heard in radio programs as well.

Joan Crawford was also a spokeswoman for Pepsi-Cola, having married the man who became the company’s CEO. This image comes from a nifty survey of her endorsements available here.

Catching up 99%

Clash by Night.

DB here:

Amplifications, corrections, and updates have been piling up over the last couple of months, and we began to realize that simply appending postscripts to older entries probably didn’t register with many readers. Judging by our stats, revisiting older entries isn’t a priority for most of the souls whom fate throws our way. So here’s some new information about older posts.

*I wrote about Jafar Panahi‘s This Is Not a Film at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Today Variety reported that an appeals court has upheld Panahi’s sentence of six years in prison and a twenty-year ban on travel and filmmaking. His colleague Mohammad Rasoulof’s jail sentence was reduced to a year. Panahi’s attorney says that she will appeal the decision to Iran’s Supreme Court. Be sure to read the Variety story for some background on the despicable treatment of other filmmakers, notably a performer who, merely for acting in a movie, was sentenced to a year in jail and ninety lashes.

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*At Fandor, in response to Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Ali Arikan wrote a penetrating and personal essay that I wish I’d had available when I wrote my review at VIFF.

*Tim Smith‘s guest entry for us, “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD,” was a huge hit and went madly viral. At his site, Continuity Boy, he has posted a new, no less stimulating entry on eye-scanning. It shows that we can track motion even when the moving object isn’t visible!

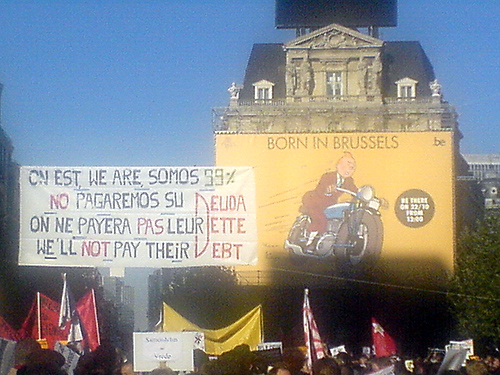

*During my trip to Brussels in early September for the conference of the Screenplay Research Network, I stole time to visit the superb Galerie Champaka for the opening of its show dedicated to Joost Swarte (above). Longtime readers of this blog know our admiration for this brilliant artist, so you won’t be surprised to learn that I had to get his autograph. The show, consisting of work both old and new, was also quite fine; it’s worth your time to explore the pictures, such as the one revealing how Disney was inspired to create Mickey (above). Thanks to Kelley Conway for taking the shot, and to Yves for taking this one. And special thanks to Nick Nguyen (co-translator of two fine books, here and here) for alerting me to the show.

*An update for all researchers: Now that we have online versions of the Variety Archives and the Box Office Vault, we’re happy as clams. (But what makes clams happy? They don’t show it in their expressions, and their destiny shouldn’t make them smile.) Anyway, to add to our leering delight, we now have the splendidly altruistic Media History Digital Library, which makes a host of American journals, magazines, yearbooks, and other sources available in page-by-page format, ads and all. You’ll find International Photographer (too often overshadowed by American Cinematographer), The Film Daily, Photoplay, and many more. Get going on that project!

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

And while we’re on silent cinema, Albert Capellani is in the news again. Kristin wrote about this newly discovered early master after Il Cinema Ritrovato in July. A recent Variety story discusses some recent restorations and gives credit to the Cineteca di Bologna and Mariann Lewinsky.

*My entry on continuous showings in the 1930s and 1940s attracted an email from Andrea Comiskey, who points out that when Barbara Stanwyck and Paul Douglas go to the movies in Clash by Night (above), she prods him to leave by pointing out, “This is where we came in.” Thanks to Andrea for this, since it counterbalances my example from Daisy Kenyon, which shows Daisy about to call the theatre for showtimes. And since posting that entry, I rewatched Manhandled (1949). There insurance investigator Sterling Hayden hurries Dorothy Lamour through their meal so that they’ll catch the show. He apparently knows when the movie starts. So again we have evidence that people could have seen a film straight through if they wanted to. It’s just that many, like channel-surfers today, didn’t care.

*Finally, way back in July, expressing my usual skepticism about Zeitgeist explanations, I wrote:

I’m still working on the talks [for the Summer Movie College], but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different? In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

David Cairns, whose excellent and gorgeously designed Shadowplay site is currently rehabbing Fred Zinnemann, responded by email:

Firstly, I find the start of WWII being equated with Pearl Harbor a little American-centric. Much of the world was already at war when that happened. Secondly, it could certainly be suggested that the two films you cite WOULD have been different without a world war. Billy Wilder and Robert Siodmak were comfortably making films in France before Hitler’s invasion drove them to a new adopted homeland. Those movies might well have happened without WWII, but they would probably have had different directors.

Thanks for this. Your points are well-taken. Not only was I America-centric, but I neglected to point out that before Pearl Harbor America was more or less directly involved in the war. Even though America wasn’t yet in the war in late 1941, a lot of the economy was on a war footing and the industry was already benefiting from the rise in affluence among audiences.

Your point about the particular directors is reasonable too. I think I chose bad examples. All I wanted to indicate was that the Hollywood system continued to function as usual, particularly with respect to narrative strategies. For instance, Chandler wrote the screenplay for DOUBLE INDEMNITY (and apparently was responsible for the flashback construction), and as you say, had another director handled it, at the level of narration it might well have been the same. UNCLE HARRY is a harder case for me, I admit! Maybe I should have chosen THE BIG SLEEP and MURDER, MY SWEET!

David replied with his usual generosity:

That’s OK! BIG SLEEP and MURDER MY SWEET definitely work! Plus any number of non-flag-waving musicals, westerns, swashbucklers (though there’s a little propaganda message in THE SEA WOLF at the end) and certainly comedies and horror. . . .

And then there’s KANE and AMBERSONS.

Better late than never–something you can say about all these updates.