Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

A variation on a sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film

Kristin here:

On April 21 a young Spanish film student uploaded his remarkable little film, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 onto Vimeo. There it languished, like so many contributions to the internet, good and bad. In the first four months of its presence on the site, it attracted 17 views.

Then, on August 17, Variation was viewed twice and earned its first “Like.” (One has to be a member of Vimeo to Like a film, so one cannot assume that none of its viewers to that point had enjoyed it.) That first Like, and perhaps both views were by Kevin B. Lee, best known for his many video essays on classic films. (See here for an index; I contributed the commentary for the La roue entry.) Over the next week and a half there were five additional views, four on August 28. I suspect some or all of these last ones were repeat visits by Kevin, since on August 31 he was the first to post an essay on Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 (hereafter Variation), along with some information on its maker, Aitor Gametxo.

The immediate result was a flurry though not a stampede of views: 33 on August 31, along with a second Like; and 15 on September 1, with a third Like. One of those views and the third Like were mine. On September 2, there were 12 views, dwindling to 2 on September 3 and 1 on September 4.

(Among the viewers after the Fandor entry was Evan Davis, University of Wisconsin-Madison film-studies alumnus, who read Lee’s blog, watched the film, and passed the links along to us. Thanks, Evan!)

It’s a pity that more attention has not been paid to this charming, clever, and informative film. Not only would people enjoy it, but it could easily be used as a tool for those teaching, or indeed researching silent cinema. So here’s my bid to help it go viral.

Variation is a found-footage film based on Griffith’s American Biograph one-reeler The Sunbeam, made in December, 1911, and released on March 18, 1912. It is not among the most famous of the nearly 500 one- and two-reelers Griffith directed at AB between 1908 and 1913, but it’s better known than most. In the opening, a sick mother dies, and her little girl, thinking her mother is asleep, goes out into the hallways of their working-class apartment building. She tries to find someone to play with, but everyone rebuffs her until she manages to charm two lonely people, a bachelor and spinster, who live opposite each other on the floor below the child’s home.

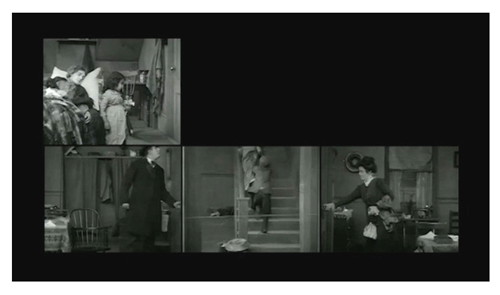

Aitor noticed three key things about the film. First, the action takes place in a very limited space, with the three apartments and hallway all close to each other. Second, the doorways through which the characters pass between these rooms are on the edges of the screen, so that when they exit through the doorway in one shot and after the cut enter the space on the other side of the doorway, there is often a sort of elusive match on action formed (what I termed a “frame cut” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, p. 205 and figures 16.36 and 37). Third, and perhaps most importantly, Griffith was intercutting actions that were happening simultaneously, so that at many of the cuts, he jumped from the end of an action in one space back in time to catch up with what had been happening in another space. At times he would jump back twice if simultaneous actions were happening in three spaces.

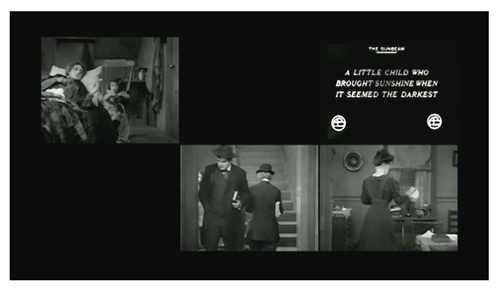

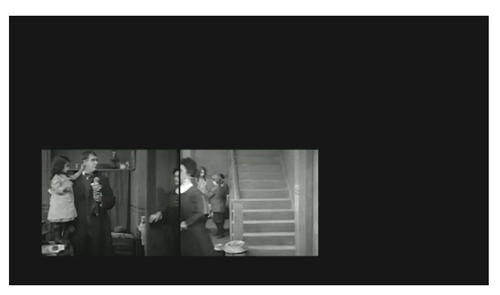

Aitor has taken the individual shots and redone them, putting them into a grid of six small frames, three on the bottom and three at the top. Scenes in the child’s upstairs apartment are shown only in the upper left, the top of the stairway in the upper center, and the two apartments on the ground floor at the sides, with the hallway and bottom of the stairs between them. (See above.) These are roughly the actual positions these spaces occupy in relation to each other in the building represented in the film. The shots run in their true temporal relations, so that there is no jumping back.

I suggest that before reading further, you watch The Sunbeam, especially if you have never seen it before. It would be impossible, I think, to entirely follow the story just from seeing Variation. The shots are so reduced in size to fit into the grid that small but important gestures and details get lost. Here is the original film, from YouTube.

With Aitor’s kind permission, we present his take on Griffith’s one-reeler. (The Sunbeam runs about 15 minutes, but due to the simultaneous presentation of many shots, Variation is only about 10 minutes.) Click on the “Vimeo” logo in the lower right corner for a larger image:

A fascinating film, isn’t it? I think many viewers would reach the end of Variation and wish that the same sort of presentation could be created for other films–at least, early ones that are short enough to make such rearrangement viable. Kevin Lee is enthusiastic about the idea: “Imagine this multi-dimensional, real-time approach being applied to footage from other films, as a way of not just mapping out scenes in a movie, but also gaining insight into filmmaking technique.” It might be possible, but the six-rectangle grid used here would not work for very many films. Aitor has chosen the ideal film for such an approach. Not only are there a limited number of significant characters, but they also live in the same building, with three rooms and a hallway, all viewed from the same direction, making them fit perfectly into a “doll-house” style scene.

Had Griffith not routinely shot directly toward the back wall in all his sets, placing the shots directly side by side across the grid would not work, at least not so neatly. Many other directors of this era were exploring shooting into corners and having doorways for entrances and exits centered at the rear. Perhaps filmmakers like Aitor could still place different shots side by side, but the actors’ movements from one space to another would not be so smooth. One of the attractions of Variation is that those movements are smooth, and as a result the action plays as if it were part of a continuous, “real” film.

Even other Griffith films shot in the style of The Sunbeam would be far more difficult to lay out on a similar grid. Longer rows of more rectangles would need to be added, or the upper row would have to represent actions taking place at a distance and the lower one actions taking place within a building. (I’m thinking here of something like The Lonely Villa, where action in a series of contiguous rooms is intercut with the husband’s race from a distant locale back to his house.) The placement of the bachelor’s room opposite the spinster’s, on either side of the hallway through which all of the minor characters pass, is crucial to Aitor’s project. A complex film with many characters and locales might create a grid with rectangles too small to be grasped by the viewers. Ways of indicating techniques like flashbacks would have to be devised. And of course, not all films contain simultaneous action.

Variation has some technical disadvantages. The titles appear in the upper right corner of the screen, since no locale opposite the child’s apartment is ever shown. The titles are small and difficult to read, and since they pop up simultaneously with the action, it’s almost impossible to read them anyway. One cannot tell where the titles originally came in the flow of shots, though one can always check the original film. Another problem is the cropping of the images on all four sides. The DVD copies are somewhat cropped, and more of the image is eliminated in the Variation frames; the action of the little heroine hiding a hairpiece in the spinster’s home, an important motivation for later action, can barely be grasped because it is so small a detail and happens at the very bottom of the frame; in the DVDs it can be clearly seen.

The Griffith Project and our knowledge of his techniques

I do not intend by any means to diminish what Aitor has accomplished when I say that the three main techniques he works from have been known to Griffith scholars for years. Variation offers a new way of examining and explaining those techniques.

Griffith has, of course, been one of the most closely studied filmmakers in history. A vast summary of and contribution to the research on Griffith was recently compiled by “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” film festival in Pordenone, Italy. From 1997 to 2008, the festival mounted a nearly complete retrospective of Griffith’s work, hampered only by those films which still exist only as negatives or in other forms that could not be projected. A team of experts divided up the work and wrote extensive program notes for every single film Griffith made, whether it was shown at the festival or not. The notes, some more general essays, and Griffith’s writings were edited into twelve volumes jointly published by the festival and the British Film Institute (1999-2008). I had the privilege of contributing notes to most of the volumes, and although I cannot claim to know Griffith’s entire œuvre intimately, I got to know the films assigned to me quite well and learned a great deal about his methods.

The program notes for The Sunbeam were written by Griffith specialist Russell Merritt (Volume 5, 2001). As these excerpts from his description of the film’s setting indicate, the doll-house arrangement of the sets in The Sunbeam were distinctive, but not atypical of Griffith’s approach:

This was the second of Griffith’s three December tenement films (falling between The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls); spatially it is his simplest. Griffith uses only five setups (fewer than half what he works with in The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls.), but far from feeling cramped or monotonous, the three rooms and two hallways spaces seem perfectly designed for the playful romps, the practical jokes, and the unfolding of the gentle love story.

By 1911, the Griffith apartment set had developed a personality of its own, or more precisely, had become both distinctive and flexible enough to accommodate a broad range of narratives. Griffith’s planimetric style, with the camera always aimed straight on into the back wall with at least one side of the room aligned to the margin of the frame, had become as much a Biograph signature as the last-minute rescue, the fade-out, parallel editing, and the stock company of actors [….] In The Sunbeam, the familiar hallway and one-room apartments turn into something resembling a row of a child’s wooden blocks or the rooms in a child’s dollhouse, albeit with a dead mother in the garret. In each space, whether the hallway, the spinster’s apartment or the bachelor’s one-room across the hall, there is something to play with or play upon. The prank with the string stretched across the hallway literally links the two apartments and provides the perfect center of a the film–a gag that depends upon the mirror symmetries of the rooms and the tug-of-war actions of the two incipient sweethearts. (p. 196)

For the prank with the stretched string made symmetrical spatially as well as temporally, see below.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book Theatre to Film (1997) points out that cutting among multiple adjacent interior rooms was typical of Griffith’s work in this period: “By early [1911] a film like Three Sisters has a climactic sequence of 28 shots alternating between three set-ups–long-shot views of three rooms, a kitchen, a hall, and a bedroom, which movements from room to room that coincide with cuts establish as side by side.” (p. 189) My own notes for The Griffith Project volumes discuss adjacent sets and room-to-room movements using frame cuts. (See the end of this entry for a list.)

Griffith’s use of editing to convey simultaneous events, as well as to portray thoughts and flashbacks has been extensively discussed in the literature on the director.

What is remarkable is that a 22-year-old film student has noticed these devices and found a simple, elegant method to demonstrate what we already knew, but with greater precision and vividness than could be done with prose analysis. To experts, that is what should make Aitor’s film so appealing.

For example, the precision of Griffith’s matches on action at the frame cuts is illustrated time and again in Variation:

Were it not for the fact that Griffith’s camera is closer to the action in the smaller hallway set than it is in the two outer rooms, the spinster’s move through the door would almost appear to be a single smooth glide. Unless one freezes the frame, as I have done here, some of these movements look uncannily continuous.

For those teaching or reading Film Art: An Introduction, Variation also provides a clear example of story time versus plot time. Griffith’s The Sunbeam presents us plot time, with its jumps backward to cover all the action in multiple locales. Aitor’s film presents story action as we ordinarily would reconstruct it only in our minds. Usually we describe story action with synopses or outlines. To see it played out in real time is a rare treat.

The filmmaker

Aitor has a blog, which contains primarily many lovely still photographs taken in Spain, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. It offers, however, minimal information about him. Kevin Lee wrote to ask him for information, which is included in the Fandor entry linked above. I also emailed Aitor with some questions to further contextualize Variation, and he provided a short summary of his background and his interest in Griffith.

My name is Aitor Gametxo. I was born in Bilbao in 1989 and have been living in Lekeitio. I started the Communication and Film degree in the University of the Basque Country, but I moved to the University of Barcelona to finish it this year. I’m currently living and working in Barcelona, and I’m going to do a “Creative Documentary” masters degree this upcoming year. I really enjoy taking pictures of everyday things and places, as a way of reporting reality. I also love film, specially documentaries, found footage films and cinema-essay pieces. I honestly believe in the power films have to make us think about things. Not only because of the topic the film is about, but also about the way in which the film is made (a kind of dialectics between Bill Nichols’ expository and reflexive modes). I love watching old (and odd) films and thinking about things that are different from the purpose they were created for. (As I told Kevin) we are able to take some footage which is temporally and geographically unconnected to us and remodel, or refix, or remix… it, giving birth to another work. This is the way I see the found-footage praxis.

About this particular film, The Sunbeam, I watched it for the first time just before doing the variation. I knew other works made by Griffith, such as “Intolerance” (quoted in several film history books). But this was unknown for me, so that the first watching was crucial. While I was enjoying it, I was wondering what the place where it was shot looked like. I suddenly imagined it as a two-floor house, where the characters cross in some moments. Also the doors were essential to fix one part with another. This was the main idea where I worked on. It was great fun doing it.

The result is this variation in real-time action of the classic work where we can see how Griffith worked on. It’s like returning back to Griffith’s mind, to the first idea, as he imagined one hundred years ago (!) how The Sunbeam would look like. This is the magic of cinema.

My contributions to The Griffith Project‘s program notes for the Biograph years are these. In Volume 2, January-June 1909: Those Boys; The Fascinating Mrs. Francis; Those Awful Hats; The Cord of Life; The Brahma Diamond; Politician’s Love Story; Jones and the Lady Book Agent; His Wife’s Mother; The Golden Louis; and His Ward’s Love. In Volume 3, July-December 1909: Lines of White on a Sullen Sea; In the Watches of the Night; What’s Your Hurry?; Nursing a Viper; The Light That Came; The Restoration. In Volume 4, 1910: A Child’s Faith; The Italian Barber; His Trust; His Trust Fulfilled; The Two Paths; and Three Sisters. In Volume 5, 1911: The Lonedale Operator; The Spanish Gypsy; The Broken Cross; The Chief’s Daughter; A Knight of the Road; and Madame Rex. In Volume 6, 1912: The Unwelcome Guest; The New York Hat; My Hero; and The Burglar’s Dilemma. In Volume 7, 1913: The Hero of Little Italy; The Perfidy of Mary; and A Misunderstood Boy.

Like the other contributors, I found myself dealing with a few famous films (e.g., the wonderful Lines of White on a Sullen Sea) and others that were largely unknown. Each little cluster of titles assigned to us consisted of films that had been made sequentially, so that each of us could get an intensive look into Griffith’s work over the course of a few weeks. It proved to be a rewarding way of approaching the study of the director. The general editor for the series was Paulo Cherchi Usai, assisted by Cindi Rowell.

The Sunbeam is also available in the U.S. in two DVD sets: Image’s “D. W. Griffith: Years of Discovery: 1909-1913” and Kino’s “D. W. Griffith’s Biograph Shorts Special Edition.” (The discs can also be bought separately.)

Despoiling the movies

The Denton Record-Chronicle (28 December 1947).

DB here:

The last line of Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon is “When it comes to modern combat tactics, you’re both babies compared to me.” If you haven’t seen the film, does knowing that ruin it for you? Suppose I went further and identified the character who spoke the line, or the immediate circumstances, or the action leading up to it? Would knowing these things ruin your pleasure? Or would it give you a different sort of pleasure?

Who doesn’t come to Casablanca knowing about “Here’s looking at you, kid,” or “Play it, Sam,” or “Round up the usual suspects”? You likely saw the ending of King Kong in compilation films before you saw the whole movie, yet you probably still watch it with enjoyment. I saw Potemkin’s Odessa Steps sequence many times, on an 8mm reel I bought as a kid, before I saw the whole movie. I still enjoy Potemkin, possibly more than many who see it for the first time. Yet people complain about trailers that tell too much, and critics who give plot twists away. Accordingly, it’s been a convention of fan and Net writing that if you’re going to give away major story information, you alert readers with the word “spoiler.”

Surely people want to know something about a film’s story. Viewers clamored for the most basic information about Super 8. And evidently many moviegoers would feel less disgruntled about The Tree of Life if they had known in advance a little bit more about what they would encounter. It seems we want to know about the story’s basic situation, but not too much about how things develop. Say: bits from the first half-hour or so, up to the beginning of the Second Act (or what Kristin calls the Complicating Action). Beyond that, we want things kept quiet. Above all: Don’t tell the how things turn out in the end.

I’ve been driven to think again about spoilers after Jonah Lehrer reported on an experiment with literary texts. On the whole, readers in the study reported enjoying a short story somewhat more if they knew the ending in advance. Jim Emerson has provided his characteristically stimulating commentary on this finding, and his readers, surely among the most reflective in the online film community, have supplemented his thoughts.

This discussion overlaps with a question I raised a while back on this site. How can we feel suspense if we know a story’s outcome? One standard answer, which would apply to spoilers too, is that even with foreknowledge, we’re interested in how that turn of events comes about. This possibility is invoked by some of Jim’s readers, and it seems plausible, especially if one is a connoisseur of storytelling. How, we ask, does the narrative engineer this or that twist?

My further proposal in the blog entry was that our mind’s intake of narratives is modular in some respects. Part of us reacts as if we were encountering the events fresh, without knowledge of what is coming up. The analogy was to standing on a balcony overhanging a precipice. You know that you cannot fall, but when you imagine yourself falling, you feel a twinge of fear all the same.

The same might be true of consuming a narrative. One of our mental systems, fast but fairly dumb, reacts to things as they come, while secure knowledge hovers more distantly in the background. I suggested as well that the way that something is presented–say, with fast cutting or sweeping music–can override our knowledge and kindle a basic, more visceral response.

Today’s entry tackles the matter of foreknowledge from a different angle. It’s worth remembering that many people who went to the movies in the 1920s through the 1950s willingly subjected themselves to spoilers.

This is where we came in?

Chicago Daily Tribune (4 January 1948).

While the American studios developed their storytelling strategies in the 1920s and 1930s, movie exhibition became a big business. In 1935, eighty million Americans went to the movies every week. The historical high point was 1946-1948, when annual attendance hit 4.7 billion. But how did all those people see the movies? More specifically, did they watch them from start to finish?

We’re so used to showing up at a definite time for a screening that it’s hard to imagine a period when many viewers would simply drop in to what were called “continuous admissions” or “continuous performances.” In major cities, the film programs, complete with newsreels, cartoons, trailers, other shorts, and even a second feature, would run steadily with only brief intermissions. You could drop in any time.

When the houses filled up, prospective viewers would have to wait in line outside or in the lobby until someone left. Then an usher would show the next patron to the empty seat. Meyer Levin’s novel The Old Bunch describes a group of friends waiting forty-five minutes before just getting into the lobby of a Chicago theatre in the 1920s.

Some of the viewers would depart during the main or second feature. Naturally, the patrons admitted in medias res would see the end of a movie before they caught up with the beginning, perhaps some hours later. Hence the phrase, “This is where we came in,” meaning, “Now we’ve seen the whole picture and can leave.”

After Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, a few readers asked why we hadn’t talked about continuous admissions. The practice would seem to explain a lot about the redundancy of Hollywood storytelling. Hyperexplicit exposition, the Rule of Three (say everything important thrice), and the habit characters have of reminding us of their relations to each other (“Gee! You’re the swellest sister a guy ever had!”)—all this would seem to be aimed at a viewer who might well have come in halfway through and need orienting to basic plot premises.

We knew about continuous performances, of course, but we didn’t discuss them because we could find no evidence that filmmakers took these conditions into account when designing their stories. In reading Hollywood screenplay manuals, technical journals, and the like, I didn’t find anyone commenting on the exhibition practice. My colleague Lea Jacobs, who has scanned Variety very comprehensively for the 1920s and 1930s, can recall no mentions of it affecting production policies.

When you think about it, screenwriters and directors couldn’t really do much to bring a latecomer up to date. You can’t keep reiterating story premises and recapitulating all that went before, and still move the plot forward. Better to tell the story straightforwardly and assume, as a default, that under ideal circumstances people would see the whole film from scene one onward. The same assumption governs TV writing, despite viewers’ channel surfing and foreplay with the remote.

Still, during the Golden Age of Hollywood a significant population consumed movies knowing how the story turned out before they saw the beginning. Ask people of my generation or older, and you’ll usually hear: “Oh, we went whenever we wanted. We never tried to find the showtimes.” My childhood moviegoing memories are dim, but I recall being dropped off at the Elmwood Theatre by my parents when they went to town. I’d go in during the movie (I do recall The Sad Sack, 1957) and watch until my mother or father fetched me out. It’s very likely that adults drifted in at odd times as well.

There’s harder evidence that some people preferred convenience to coherence. In 1950 Twentieth Century-Fox announced that All About Eve (1950) would be screened only in “scheduled performances.” No one would be seated after the film began. Premiering at Manhattan’s Roxy Theatre, Eve ran for a week under the new policy. It failed. People hadn’t heard about the new rules, showed up late, and weren’t admitted. The results were angry lines outside and empty seats within. The practice was halted and Eve screened in continuous performance. The Hollywood Reporter attributed the failure to “the public’s deeply ingrained habit of going to a movie show at any desired hour, when most convenient or on impulse.”

In other words, many people were encountering what we call spoilers all the time, and it didn’t seem to bother them. So you wonder: Is watching a movie straight through, as we mostly do today, a newer, more “disciplined” mode of consumption?

It’s showtime

Daisy Kenyon.

It’s obvious that the custom of just dropping in didn’t guarantee a nonlinear movie experience. With a double-bill house, even if you dropped in arbitrarily, you would see one feature or the other in a single gulp. And assuming a three-hour program and a 90- or 95-minute A picture, your odds of walking in during the shorts or the B film were about fifty-fifty.

But were people obliged to drop in willy-nilly? Could they have seen the movie straight through if they wanted to?

There’s considerable evidence that parts of the audience did want to see the movies in linear fashion.Consider the early attenders. And many cinemas filled up quickly just before the show started. Coming in when the theatre opened seems a fairly clear indication of wanting a linear experience. True, early attenders would probably have to sit through a newsreel, trailers, and other shorts, but many people enjoyed those too. Further, since double-bill houses screened the A picture first, knowing that custom could guide your decision about when to come in.

Could patrons have gained specific information about when the movies were screening? There’s a widespread belief that theatres didn’t publicize showtimes. But that’s not the case.

First, the box office almost always posted a schedule breaking down the program. Sometimes cardboard clocks with movable hands indicated showtimes. Patrons might see the schedule when they arrived, or while passing the theatre during the day. Knowing the schedule, you didn’t have to go straight in. If you bought your ticket while the feature was running, you could linger in the lobby. Probably some viewers were reluctant to enter if the feature they wanted to see was just ending.

Second, there were newspaper advertisements. This evidence is varied and intriguing, full of unexpected quirks. First, I took a look at late 1940s ads for the Elmwood, my hometown venue. These ads are mostly bare-bones. They list the movies, all double features, with three changes a week (films played Friday-Saturday, Sunday-Monday, and Tuesday-Thursday). The theatre doesn’t supply its phone number, probably because many families in our area didn’t have phones until the late 1950s. Showtimes are seldom mentioned. Doubtless townfolks knew by local custom what the showtimes were, and there was no need to advertise it in newspapers or handbills (which were still around in the 1950s). One September 1949 item specifies opening and closing hours:

Matinees Daily 2:00

Evenings 7:00 to 11:30

Sundays and Holidays Continuous 2:00 to 11:30

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

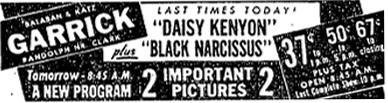

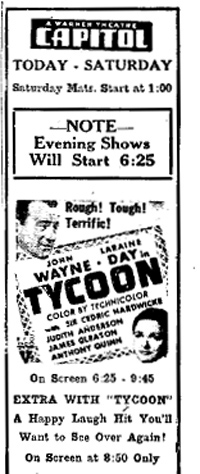

But some ads in other towns get a little more specific. “2 COMPLETE SHOWS 9:30 & 12 MIDNITE,” blares the Colonia of Norwich, New York in 1947. This indicates the starting times for the newsreel, cartoon, and ads, which all preceded the main feature. But since many theatres began their screening at 6:00, the accompanying ad from the Capitol, of Dunkirk, New York in 1948 seems to be saying that after all the shorts and ads, Tycoon hits the screen at 6:25. That movie ran a little over two hours, so there was time for filler leading up to the Happy Laugh Hit (presumably a revival). More unequivocal is the ad for Daisy Kenyon at the very top of this entry, which specifies when the feature starts. Again, the theatre probably opened at 1:00 and brought in the evening crowd at 7:00. That left fifteen minutes or so for pre-show material, including the color cartoon and “Global News”.

In short, some newspaper ads tell us only the theatre’s operating hours, while others specify showtimes. This sort of variation goes far back. The Olean (New York) Evening Herald advertised the Strand Theatre as “showing continuously 1 to 11 daily,” with no showtimes mentioned. On the same page we find specific starting times listed for a rival theatre’s showings of Fairbanks’Mark of Zorro (1921).

For special occasions, the scheduling could be quite exact. If you happened to be in Middletown, New York, on New Year’s Eve of 1947, you could welcome in “Kid 1948” at a gala show starting at 7:00 and ending “some time in 1948.” But not just “some time”: The State’s plan has a military precision.

Daisy Kenyon at 7:00 – 9:29 – 12:01

Comedy “Skooper Dooper” at 8:38 – 11:08

Terrytoon Cartoon “Silver Streak” at 9:12 – 11:42

Community Sing at 9:19 – 11:49

Latest Pathe News at 8:56 – 11:26

The ad goes on:

No seats reserved – No waiting in line. Come any time from 6:30 until 11:20 and see a complete show—Stay as long as you like! Come in one year—Leave the next!

The rival Goshen Theatre likewise provided a detailed schedule of its New Year’s Eve attractions, an astonishing four features plus cartoons. The show, broken into 9 “units,” started at 7:00 and ended at 1:00 in the morning, concluding with an “Exit March.” Why don’t movie theatres have exit marches any more?

Apart from ads specifying showtimes, we can glean other hints that at least some viewers preferred to know when to arrive to catch a film from the beginning. Some newspapers published lists of starting times. The New York Evening Post printed an extensive “Movie Clock” covering over eighty theatres. A Schenectady paper did the same thing under the rubric “Showing Today. What the Theatres Are Advertising.” You can find a similar feature in papers from Portland and Council Bluffs. Movie houses were often a small-town newspaper’s biggest and most reliable advertising source, so many editors were ready to oblige theatre managers.

Movie ads also sometimes included the theatre’s phone number, so people could call to check showtimes. Access to telephones was still spotty then; recall that the infamous Gallup Poll of 1948 misjudged Dewey’s chance for victory, partly by relying on phone surveys. But by 1945 there were about 16 million residential phones for a population of 140 million, so the middle-class people sought by exhibitors, then as now, might well be able to call up the movie house.

That is, in fact, what Daisy Kenyon does at one point in her movie. Having decided to go out with her girlfriend, she checks the phone number of the theatre she wants to visit and starts to call to check on showtimes. (She’s interrupted by a call from the mysterious Peter Lapham.) The scene seems to model one set of urban filmgoing habits.

Historian Douglas Gomery reminds us that there were many different sorts of theatres–first-run and subsequent-run, big downtown houses and neighborhood venues, rural ones, art houses, and so on. I’ve tried to capture some of this variety in my exploratory sample, but there are many fine-grained differences. Moreover, roadshow pictures often played to strict schedules, selling tickets for specific performances, and people adjusted their schedules to that regime for Gone with the Wind and other blockbusters. Perhaps the All About Eve fiasco came from people thinking this new film, in black-and-white and offered at regular admission prices, was not an event film like the usual roadshow attraction.

In all, it’s hard to generalize about viewing patterns. But it seems fair to say that in many circumstances viewers could, if they wanted, avoid seeing a movie’s ending before the beginning.

Which means that, then as now, we find different viewing styles. Today we have the Planners, who Tivo their cable television offerings, and the Grazers, who hop from channel to channel and watch in medias res. (We also have the Gleaners, who sample items at their leisure via the net. But there doesn’t seem to be an equivalent option in classic theatrical film viewing.) Several of Jim Emerson’s cinephile readers point out that they appreciate spoiler alerts in a web review because they want the choice between knowing and not knowing. It seems that in many circumstances movie houses offered 1940s viewers that same option.

Exhibition history is far from my specialty, so I’d welcome information from researchers who’ve studied this question more systematically. In the meantime, I’m grateful to Kristin, Ben Brewster, Lea Jacobs, Vance Kepley, Betty Kepley, John Huntington, and Virginia Wright Wexman for discussion with me. A special thanks to Douglas Gomery, who shared detailed information in emails and phone conversations.

For a comprehensive history, see Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992). See also Gregory A. Waller, Moviegoing in America: A Sourcebook in the History of Film Exhibition (Wiley-Blackwell, 2001) and Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema (University of Exeter Press, 2007), ed. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen. Allen has mounted a beautiful online archive devoted to moviegoing in North Carolina.

A useful older source, though not focused on the 1940s, is Frank H. Ricketson, Jr., The Management of Motion Picture Theatres (McGraw-Hill, 1938). Ricketson advocates three hours as a maximum program time.

The motion picture theatre has a constant drop-in trade, and the patron who catches the feature after it has started does not want to sit through a seemingly endless program to see the part that he has missed. The tendency today is to present shows that are too long (p. 121).

It’s possible that as an employee of Fox Theatres, Ricketson was pushing the then-common industry view that double features were undesirable. Fewer films on the bill allowed more turnover during the day and favored the higher-profit A pictures.

Information about All About Eve‘s “scheduled performance” policy comes from the American Film Institute Catalog. See also “Business on ‘Eve’ at Roxy Jumps After Scheduled Showings Cut,” Boxoffice (28 October 1950), 50, available here. Linda Williams argues that Psycho‘s exhibition policy helped create the custom of consuming a movie straight through. See her “Discipline and Distraction: Psycho, Visual Culture, and Postmodern Cinema,” in “Culture” and the Problem of Disciplines, ed. John Carlos Rowe (Columbia University Press, 1998).

My analogy to standing on a precipice comes from Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror.

Two final points I couldn’t squeeze in elsewhere. First, to a large extent, spoilers are a function of different sorts of movie talk. In daily conversation, we’re reluctant to tell too much to friends who haven’t yet seen the film. Journalistic film reviewers seek not to reveal the ending, of course, but they’re also obliged to write about many scenes in an oblique way. (“After a string of preposterous coincidences…”) Net writers seem to model their comments on conversation and professional reviews, although some rascals delight in telling innocent readers everything that happens. We might call them spoilersports.

By contrast, academic writing assumes that the reader has seen the film, or is willing to let details be divulged for the sake of some larger point. Occasionally bloggers adhere to this standard. Readers of J. J. Murphy’s blog know that he doesn’t refrain from synposizing a plot to give depth to an analysis. I’ve done the same thing here on many occasions, but sometimes I feel the need to signal spoilers, particularly for current releases or films that depend on big twists. For some reason, I think that older films are fair game for full-blown discussion, even though many of our readers are less likely to have seen Enchantment than Source Code.

Second point, pure digression: In 1947, Richard Hull published Last First, a mystery novel dedicated “to those who habitually read the last chapter first.” The opening chapter does provide the story’s ending, but as you’d expect there’s a trick. The chapter is written so obliquely that you can’t really tell who is doing what to whom. At least I can’t.

P. S. 18 May 2012: Two more items that I’ve run across relevant to the this-is-where-we-came-in problem. First, this dialogue exchange from Ellery Queen’s serial-killer novel of 1949, Cat of Many Tails. The murder victim, one investigator says, “left for a neighborhood movie. Around nine o’clock.” The other asks, “Pretty late?” The reply: “She went just for the main feature.” This suggests that in Manhattan, it wouldn’t be impossible to know when the main feature played for the last time–either from the newspaper, from a phone call, or just from custom.

It seems that indeed late shows of the A picture were common. A 1939 Variety article, “‘Bad’ Scheduling Squawk” (27 December 1939, 5, 47) indicates that often the “No. 1 film” was put on at awkward hours, and viewers objected. “Too often, it is declared, a customer will call the theatre, only to learn the film he or she wants to see goes on at a time that interferes with dinner, or it’s on the last show, so late that getting out would be around midnight or thereabouts. Result, under theory, is that the customer doesn’t go at all.” Again, we find some evidence that the public could find out when a movie played by phoning, and that at least some patrons cared enough to see the picture through from the start. This piece from 1939 suggests that these options were available at least in some towns throughout the 1940s. Presumably, this practice was prominent in theatres not controlled by the studios, since the B picture was a flat-rate rental but the No. 1 feature was a percentage booking. The more tickets you could sell for the B, the bigger the exhibitor’s share of receipts.

P.S. 21 May 2012: The Wisconsin Project never sleeps. Alert Ph. D. researcher Andrea Comiskey sends me 1939 ads from the Olympia in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the Fox in Billings, Montana. Both lists start times for both features, A and B, with the Fox including the start times for cartoons and newsreels too. The heading is, bluntly, “When to Come Today.” As per the above addendum, the Fox runs the A picture last, and quite late (around 10 PM).

P.P.S. 1 February 2021: Ran across this in John O’Hara’s novel Butterfield 8 (1935):

“What are we up to this afternoon?”

“Oh, whatever you like,” she said.

“I want to see ‘The Public Enemy.'”

“Oh, divine. James Cagney.”

“Oh, you like James Cagney?”

“Adore him.”

“Why?” he said.

“Oh, he’s so attractive. So tough. Why–I just thought of something.”

“What?”

“He’s–I hope you don’t mind this–but he’s a little like you.”

“Uh. Well, I’ll phone and see what time the main picture goes on.”

“Why?”

“Well, I’ve seen it and you haven’t, and I don’t want you to see the ending first.”

“Oh, I don’t mind.”

“I’ll remind you of that after you’ve seen the picture.”

Daisy Kenyon. Daisy and her friend, tracked by Peter and watched by a waiter, have apparently gone to a revival house–and one not playing pictures from Fox, the studio behind Daisy.

Puppetry and ventriloquism

“I thought they burned that.” Hellzapoppin (1941).

DB here:

Coming back from my five-week stay in Europe (known in the Midwest as Yurrrp), I watched two releases I’d missed in the spring. Neither one was of outstanding quality, to put it mildly, and both were limited by “having been formatted to fit” the 4 x 3 airplane screen. Still, I was struck by how much both were like the 1940s movies I’d just been talking about with eighty participants in the Antwerp Zomerfilmcollege.

Of course the films’ look and feel were quite different, with Bouncycam and fast cutting instead of the rock-steady compositions and more sedate pace of the 40s films. But since I’d been concentrating on narrative matters, both of the recent releases chimed with my concerns in the course.

For one thing, both relied on flashbacks. Battle: Los Angeles used the technique casually. After a brief prologue showing our squad in a helicopter heading into a firefight, we get a title, “Enemy contact minus 24 hours.” This takes us back to the previous day, when the aliens’ attack seemed merely a meteor shower. We get to meet the Marines’ team in the usual vignettes of guys buddying around, planning their futures (one grunt is getting married soon), and nursing their woes (ageing, or mourning a slain brother). Why couldn’t these twenty minutes of exposition be given at the outset? Do the makers think we’re too impatient to wait for the first alien onslaught? Do they think we don’t know that the whole premise of the movie is an interplanetary assault on LA? In any case, the flashback is over by the sacred 25-minute mark, and we’re plunged into the ongoing action, starting with the team’s effort to save some civilians trapped in the combat zone.

Limitless used a more extended flashback. It follows what I called in Antwerp the “crisis” architecture, whereby the plot begins at or near the action’s climax and then moves back to the point at which the main story action begins. A prototype of the structure is The Big Clock (1948). Accordingly, Limitless opens with the protagonist about to leap off a high-rise terrace while his enemies pound at the door of his apartment. Then we return to his origins as a grungy wannabe writer, and the bulk of the film moves toward the critical point shown in the opening.

Limitless also reminded me of the 1940s’ penchant for rendering character psychology through subjective film techniques. After Eddie Morra takes the mind-enhancing drug, his world becomes distorted and we get unusual angles on him.

But Eddie’s head trips have precedents in the frenzied dream sequence of an early film noir like The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940). A frantic rehearsal montage in Blues in the Night(1941), with its shots from the “viewpoint” of a piano keyboard, pushes the pictorial envelope further than the comparable shot in Limitless.

Today’s digital technologies make it easier to go for extreme effects, but wild imagery is nothing new, especially when it’s motivated as representing extreme subjective states.

Of course flashy storytelling, including time-juggling and subjective images and sounds, can be found in cinema before the 1940s. But in that era they became more prevalent, in effect a “new normal.” And very quickly filmmakers sought to push them further, with results that linger today. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I try to argue that the flagrant artifice of 1940s films was revived in the 1990s and 2000s. Citizen Kane is in a way the ultimate “puzzle film,” with one clue to the meaning of Rosebud tucked away in a minor set. The narrative gymnastics of The Hudsucker Proxy, Pulp Fiction, Memento, The Matrix, Inception, Shutter Island, and many other movies hark back to the revisions of storytelling traditions that crystallized fifty years earlier.

Unelected affinities

It’s not just that the two airborne movies chimed with what I’d been screening. Anyone who teaches art or literature is familiar with what we might call the cluster-surprise effect. When you assemble a batch of books or plays or films to make up a semester course, you start to notice affinities you wouldn’t have spotted if the artworks hadn’t been set side by side.

To a greater degree than usual, cluster surprises arose within the movies I screened for the Belgian Zomerfilmcollege. I’ve participated in these summer movie camps before, but seldom have I had such a sense of interconnections among the films we watched. It’s as if the makers were talking to each other, or at least looking over their shoulders at what their compadres were up to.

To some extent, convergence was to be expected. The films were picked to illustrate storytelling innovations in 1940s Hollywood films, so that guaranteed some overlap. Moreover, I’ve elsewhere suggested that filmmakers are making movies as much for each other as they are for the general public. My most recent instance was in a peculiarly recurring ad for ale.

So I probably shouldn’t have been as surprised as I was. Still, I was initially ready to notice changes within individual directors’ outputs, such as Welles’ development from the quietly controlled pressure of The Magnificent Ambersons to the narrative fireworks of The Lady from Shanghai. What I didn’t expect was the crosstalk among Ford, Mankiewicz, and Siodmak in their handling of flashbacks, or the way that the elegant methods of characterization found in A Letter to Three Wives set off the opacity and contradictory behaviors of the love triangle in Daisy Kenyon.

I need to think more about how the films we screened, plus the hundred or so others I’ve been watching in the spring and summer, can illuminate our understanding of creative choices facing filmmakers then (and today). Some of this thinking will eventually surface in more extended writing, I hope. For now, here are three ideas about 1940s storytelling, sparked by the sheer juxtaposition of interesting movies.

Of course there are spoilers. The films most vulnerable to spoilage are Laura, The Killers, All About Eve, and Sunset Blvd. Maybe you can use your parafoveal abilities to skip the passages that deal with ones you haven’t seen.

Art as artifice

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

The 1940s highlight a basic feature of Hollywood cinema, and indeed most popular traditions I know. Artifice, often self-conscious artifice, usually rules. It’s most evident in crazy comedy (see way up top), but even dramas seldom yield what people usually think of as realism.

Imagine a continuum between surveillance-camera video at one extreme and ballet or commedia dell’arte at the other. Hollywood lies much closer to the stylized side than to the documentary-recording side. This tradition is heir to a host of conventions derived from painting, drama, vaudeville, opera and operetta, prose fiction, and, by the 1940s, radio. All of the resources of these arts are brought together for the sake of telling a compelling, moving story, and anything that works is fair game.

Take one technique that became robust in the 1940s, the voice-over narrator. Some theorists claim that every narrative must have not only a narrator but a “narratee,” somebody who is listening to the story being told. Yet in most situations we haven’t the foggiest idea who the narratee would be.

At the start of The Magnificent Ambersons, Welles’ ripe baritone tells us things about the town, the family, and long-gone fashions. At the start of All About Eve (1950), the urbane Addison DeWitt promises to give us the dirt on the young woman’s rise to stardom. The cases are significantly different. Welles creates what we might call an external narrator, one who isn’t participating in the events we witness. Addison is a character narrator, one who exists within the story and plays a role in the action. In either case, though, we can ask: To whom is the narrator speaking?

Addison isn’t addressing other characters, even in retrospect; we never see anyone listening to his tale. Welles’ voice-over narrator can’t be addressing the characters because he isn’t in the story world at all. So who’s listening? Before you say, “Well, they’re addressing us, the audience,” remember that both these narrators are fictional beings. They don’t exist in our world and we don’t exist in theirs. In daily life, if you said your nonexistent friend told you of his adventures, we’d tend to wonder about you, and we’d certainly place little credence in the events reported.

In art, though, no problem. It’s simply a convention—a piece of artifice—that lets us accept the voice-over as a mimicry of a conversational situation (a person speaking to another) and delete the part that assumes a tangible listener. So the commonsense answer is right. These narrators are speaking to us. In fact, everything in a fiction film is addressed to us. If you want an ontologically tidy answer: The actual filmmakers are the storytellers, the actual viewers are the audience, and everything else is smoke and mirrors, or puppetry and ventriloquism.

You can put it more generally. As often happens, the movie summons up a familiar schema from ordinary life, the conversation, but revises it for artistic purposes. The film draws on certain features of reality but deletes others, retaining just enough salient bits to prompt our understanding. Filmmakers can assemble, in the manner of collage, pieces of standard social interactions for particular effects. Our response depends on the patterns that are formed, not on the reality status of the bits or of what is left out. We concentrate on the effect, not the means used to trigger it.

The same thing goes for the narrator’s range of knowledge. In literature, the “I” narrator typically cannot report things she doesn’t know about. If something happens that she couldn’t witness at the time, she’s obliged to explain how she learned about it subsequently. But internal filmic narrators often lead us into moments, or entire sequences, that they weren’t present to witness. In The Killers (1946), Nick Adams tells the insurance investigator Riordan that Ole the Swede encountered a mysterious man from his past, but given Nick’s position at the rear of the car, paying no attention to the encounter, he couldn’t have observed the way Ole intently avoids meeting the driver’s eyes.

Huw, the narrator of How Green Was My Valley (1941), didn’t see, and may not have known about, his sister Angharad’s visit to Reverend Gruffyd.

Yet the scene, played out between the two near-lovers, is given to us within the narration established as Huw’s.

By convention, then, filmic narration allows a lot of leeway to a character narrator. Again, a realistic situation, someone reporting on what they know, is treated in a partial, stylized fashion for the sake of sharpening the effect. We’re more curious after noticing the driver’s frowning look at Ole, whether or not Nick could have strictly seen it. We’re more intensely involved with the emotion of the Angharad/ Gruffyd romance than if we simply saw Huw learning about her visit later.

Proteus in Hollywood

Once a convention is put in place, somebody is bound to play with it. A one-off example occurs in Ambersons, when we get this exchange on the soundtrack:

Gossip: They’ll have the worst spoiled lot of children this town will ever see.

. . . .

Narrator: The prophetess proved to be mistaken in a single detail merely. Wilbur and Isabel did not have children. They had only one.

Gossip: Only one! But I’d like to know if he isn’t spoiled enough for a whole carload.

(Interestingly, Welles doesn’t present this exchange in his 1938 radio version of the novel.) Likewise, the opening of Eve is trickier than I indicated, partly because Addison’s narration is accompanied by a freeze-frame at the moment the award is presented.

Since a few years before this, It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) showed angels freezing time and commenting on George Bailey’s dreams, you have to wonder if Mankiewicz isn’t endowing Addison with a supernatural power.

Addison will, by the end of the film, be utterly in control of Eve.

The 1940s and early 1950s see an immense amount of experimentation with narrators. Narrators can lie about what they report. They can be dead (Scared to Death, 1947; Sunset Blvd, 1950), otherworldly (the angels in It’s a Wonderful Life), non-human (the house in Enchantment, 1948), or of uncertain status (Woman in Hiding, 1950).

A good example of the high artifice of the period comes in Laura (1944). The film is introduced by Waldo Lydecker’s voice-over, remembering “the weekend Laura died,” and remarking on the detective Mark McPherson, wandering through Waldo’s art collection. Waldo’s voice-over, describing events in the past, might seem to assure us that he survives the ensuing story.

Fairly soon Waldo’s voice-over reappears, but it doesn’t frame the overall fiction. As he explains his relationship with Laura to McPherson, we get episodic flashbacks showing Laura’s rise (and, true to form, including events Waldo couldn’t have known about). At the end of their evening together, the film’s narrational weight shifts visibly to Mark, showing him in an uncharacteristically tight close-up watching Waldo depart.

The absorption of Waldo’s voice into the overall texture of Mark’s investigation invites us to forget that Waldo initiated the film, and that he in fact fed us false information. (Laura didn’t die that weekend.) So the ending, in which Waldo falls before policemen’s pistol blasts, comes as a new surprise. The camera tracks away from him murmuring, “Goodbye, Laura”, past Laura and Mark, to the shattered clock face that recalls what Waldo’s shotgun did to Laura’s surrogate.

Over this image we hear Waldo’s voice: “Good night, my love.” From one angle, the line could be considered Waldo’s offscreen dying words, continuing his murmured farewell to Laura. Yet the last line is closely miked in the manner of the opening voice-over, suggesting a voice from beyond the grave. Was Waldo narrating the first scene from the same place? Is this a tale told by a corpse? The ending is equivocal, hovering between the two possibilities.

Again and again, the films we saw fractured tidy patterning. Addison’s voice-over narration in All About Eve gives way to that of another character, Karen Richards. After he glances at her, a cut presents her voice-over taking up the burden of introducing us to the young Eve in a flashback.

How to explain this tag-teaming, except as pure artifice, a new wrinkle in a convention that by 1950 had become second nature to filmmakers and viewers?

In The Killers, the dying crook Blinky is questioned by two investigators. No problem about narratees here; he speaks to them. But the film makes a new problem for itself. Blinky is too far gone to respond to questions. All he can do is mutter phrases from the past. Yet the film’s narration dramatizes his ravings, presenting the scene he invokes as fully as any other.

Is this what his listeners are imagining? No; it’s just a stretching of the conventions surrounding the character narrator. After several orthodox voice-overs earlier in the movie, we can assume that Blinky’s babble will be translated into solid scenes, as more articulate talk has been earlier. Again, plausibility is flagrantly violated; who could construct a coherent set of actions, let alone a legal case, out of fragmentary phrases? But who cares? Blinky is a device to get us into the past, and the filmmakers assume that we’ll follow the most slender lead they offer.

Meir Sternberg has articulated a powerful case that there are no “package deals” in verbal art. Any narrative or stylistic device can fulfill a wide range of functions, and any functions can (with sufficient motivation) find expression in many different techniques. To take a filmic example, a dissolve can indicate a passage of time, but sometimes a dissolve (say from a long-shot to a closer view of a character) suggests continuous duration. And a cut may indicate continuous time, but it can also indicate that a stretch of time has been skipped over, as throughout Resnais’ Muriel. Sternberg calls this the Proteus Principle, “the endless interplay between form and function.”

Along these lines, conventions within a tradition can be seen as the most probable fit between form and function, the ones we expect because we’ve seen them in other films. In studio-era Hollywood film, dissolves usually signal a passage of time, and cuts within scenes usually indicate continuity. But those functions are local and subject to revision. Likewise, a voice-over narrator is unlikely to talk with the characters, except in the case of comedy. For Welles to try it in a drama was a bit daring, but it simply shows that there is room, if the filmmaker proceeds carefully, to stretch the convention. (It had already been stretched in both the play and film versions of Our Town.)

Collaborative competition

How to explain these fractures of form? Invoking a Zeitgeist explanation—wartime trauma, postwar dislocation—seems to me a desperate measure, for reasons I’ve outlined elsewhere. In the Antwerp sessions, I suggested some other explanations, which I hope to justify at greater length another time. For now, let me propose just one factor that seems to me to have contributed to the wilder side of 1940s storytelling.

The famous opening of E. H. Gombrich’s Story of Art—“There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists”—is open to many interpretations. One is that art history is driven by the human dispositions of the image-makers. Those dispositions include rivalry. In his 1974 essay “The Logic of Vanity Fair,” Gombrich further explores the role of competition among artists. In many traditions, they may try to raise the stakes, seeking to outdo others in virtuosity. I’d add that such artists either try to beat their predecessors and contemporaries at their own game, or to invent a game in which a newcomer can excel. Later in his career Gombrich suggested an analogy to ecology: some artists fight for the same niches, others adapt themselves to unexploited ones.

From this standpoint, I’d suggest that a close-knit world like Hollywood encouraged competition among its creators. In the period I’m concerned with, some ambitious Hollywood filmmakers (not only screenwriters but also directors, cinematographers, and their colleagues) saw voice-over narration as an opportunity to innovate. The technique may have arisen partly because people were used to it from radio, and it offered advantages in efficiency and low cost. Detour (1945) shows that a fairly static, cheaply shot scene can be energized by extensive voice-over. Ambitious filmmakers could make this still-emerging technique more forceful, more mysterious, more evocative. The cost of this effort was some violation of realism and an occasional violation of tidy form.

In just a few years, we go from Welles’ external narrator being sassed by a gossip to Mankiewicz’s character narrator passing the expository ball to another character. We see a community of creators pushing each other to revise a schema they inherited, to test its limits and find new effects it could create. I think that this “collaborative competition” operates in other innovations of the period, such as the long take, the flashback, deep-focus cinematography, and sound manipulations.

Something like this creative community still exists. Urges to compete through innovation (or to revive older conventions) seem to drive some of our filmmakers. The impulses assume a feeble form in Limitless and Battle: Los Angeles, but at least these program pictures remind us that competition isn’t only financial; it’s also artistic. The pressure to come up with a fresh revision of a familiar schema is, if anything, keener today than in the 1940s. Insidious has to top Paranormal Activity, which itself revised a traditional formula in fresh ways.

The snag is to do something that we haven’t seen before. That’s tough when you come at the end of the line that includes filmmakers like Ford, Hitchcock, and so many others. This is the problem of belatedness, and some day it will get a whole entry of its own.

Two especially strong books on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s are Thomas Schatz’s Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s (University of California Press, 1997) and Dana Polan’s Power and Paranoia: History, Narrative, and the American Cinema, 1940-1950 (Columbia University Press, 1986). By presenting a detailed overview of industrial developments, Schatz supplies a vivid context for studying artistic trends. Polan, focusing on an immense range of films, aims to explain their formal and thematic qualities from a broadly Foucauldian perspective. Here “discourse” assumes an immense power over the way the films look and sound, and the motive force behind the discourse is largely, though sometimes obliquely, World War II.

In addition, I should pay tribute to Sarah Kozloff’s fine Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (University of California Press, 1988). Kozloff includes concise, sensitive analyses of How Green Was My Valley and the opening of All About Eve. For the latter film, she traces Addison’s narrational power in some detail. Needless to say, my thinking has also been influenced by Kristin’s essays on Laura and Stage Fright, to be found in her collection Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988).

For more information about Mankiewicz’s plans for All About Eve, including a scene replaying earlier action with different significance, see Gary Carey, More about All About Eve (Random House, 1972), 56-58. According to Carey, Mankiewicz shot this and other material that was excised in the editing stage. The version of the screenplay printed in Carey’s book clearly isn’t the shooting script (it seems to be close to a transcript of the finished film), and it does contain the passages I’ve considered: the freeze-frame (p. 127) and the moment in which the narrational voice slips from Addison to Karen (p. 128). This published version is widely available online in various formats; the typescript copy available here carries the tag “Shooting Draft” and doesn’t contain the scenes that Carey claims were dropped in postproduction.

My quotation from Meir Sternberg comes from “Narrativity: From Objectivist to Functional Paradigm,” Poetics Today 31, 2 (Fall 2010), 594. Gombrich’s essay, “The Logic of Vanity Fair: Alternatives to Historicism in the Study of Fashions, Style and Taste,” appears in his collection Ideals and Idols: Essays on Values in History and in Art (Phaidon, 1979), 60-92.

In my Antwerp talks I approached questions of form and style in the 1940s by trying to reconstruct the creative problems and solutions arising within the filmmaking community. For me, filmmakers working within institutions are the most proximate agents of stability and change. For examples of this approach, see my chapters of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, The Way Hollywood Tells It (which considers the problem of belatedness), and my analysis of Mildred Pierce in Poetics of Cinema. My critique of Zeitgeist or mood-of-the-moment explanations can be found in Poetics of Cinema, 30-32.

You can sample how I’ve tried this approach out in pieces on this site. For instance, this entry examines artistic competition through the example of high-school lipdubs, this one talks about our appetite for artifice, and this one discusses how Cloverfield solves the problem of point of view in a monster movie. This essay on actors’ eye behavior develops the idea that filmic conventions often remake, in streamlined form, familiar aspects of social interaction. I hope to develop my case for the 1940s more thoroughly at some future point.

Zomerfilmcollege, Antwerp (July 2011). For more on this event, see earlier entries here and here.

Unquiet silents

DB here:

It happens every year: the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna is offering something for everyone. It’s officially dedicated to film history, but its organizers understand that history includes today. This year you can watch films from 1898 (Gaumont shorts) to 2011 (The Actor, hot from Cannes). Silent cinema is given its due, but so are films from the 1930s-1950s, with glimpses of the 1960s (Petri’s The Assassin, the new La Dolce Vita) and 1970s (Kevin Brownlow’s little-seen Winstanley).

The director retrospectives alone are overwhelming. We have a chance to watch great swatches of films by the celebrated Alice Guy, the underappreciated Luigi Zampa, the effortlessly lyrical Boris Barnet, and the still-being-discovered master of the 1910s, Albert Capellani. Oh yeah, then there’s a guy called Hawks, with a complete set of all his surviving silents filled out with little items like Twentieth Century, Tiger Shark, and thanks to Grover Crisp a lab-fresh restoration of Only Angels Have Wings that had even hard-core Ritrovato veterans gaping.

Not to mention sidebars dedicated to images of socialism and utopia, the development of color cinema, and the annual “100 Years Ago” series curated by Mariann Lewinsky, who brought a stunning array of 1911 films into our ken. With Ayn Rand’s gospel of egoism and selfishness finding ever more adherents these days, a screening of the original Italian version of We the Living (Noi Vivi) reminds us that, contrary to the evidence of this year’s Atlas Shrugged, you can make a pretty good movie from one of her books. (Of course the great Rand adaptation is the out-sized Fountainhead.) In the evenings, on the Piazza Maggiore, items like The Thief of Bagdad and Taxi Driver regale a thousand people or more.

In short, a feeding frenzy for the cinephile. We’ve been here before; you can read reports from the last four years in the category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato. But this time things are even more intense. A fourth venue has been added, the ample and modern Cinema Jolly, so the decisions about what to see are even more pressing.

Kristin has concentrated her viewing on the 1910s, although so far she’s found time for Wind Across the Everglades and an episode of Barnet’s charming Miss Mend. (She wrote about the Flicker Alley DVD of this here). Her upcoming blog entry will concentrate on Capellani. For now, I find that a mere two films give me something to chew on.

From talky silents to talking movies

Upstream.

Ford and Hawks are very different directors, but two 1927 films, both made at Fox, allow us to see their work blending into a broad trend.

Upstream, recently rediscovered and shown to admiring audiences around the world, takes place largely in a boarding house for struggling vaudevillians. A knife-thrower is in love with his assistant, who is in love with a self-centered ham hired to play Shakespeare. Among the roomers are a declining classical actor and the song-and-dance brothers Callahan and Callahan, one of whom is Jewish. The ham accidentally becomes a star, in the process forgetting the girl he once wooed. But her marriage to the knife-thrower is threatened when the ham returns to the boarding house.

The film has the drawling, anecdotal quality of many Ford comedies. The plot is simple, but it’s decorated with character bits and an overall tone of self-aware corn. The latter was enhanced in the Ritrovato screening by the brash musical accompaniment designed by Donald Sosin, with him on piano and Guenter A. Buchwald on violin. Sosin, like Ford, knows hokum when he sees it, and both know that you must revel in it.

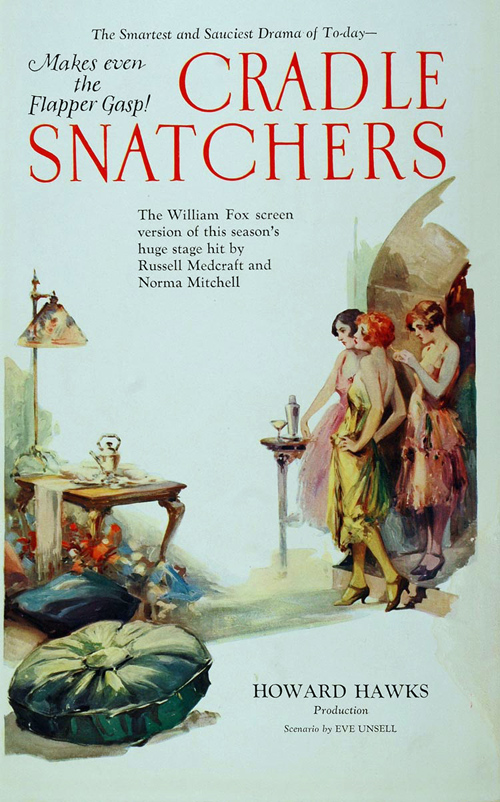

Cradle Snatchers, Hawks’ third film, shows a trio of cheated wives exacting revenge on their philandering husbands. The women arrange for three penniless college boys to pretend to court them so that their husbands can become jealous. Even though some portions are missing, the first reel is intact, and it’s instructive. Instead of opening with the women’s plight, as the source play does, the film starts with the fraternity brothers and mostly anchors our viewpoint to theirs. Variety noticed.

Probably the most remarkable angle of transplanting this “smash” comedy to celluloid lies in the manner in which the three college youths have been duplicated. As a screen threesome they overshadow the women who play the neglected wives. . . Each of the male youngsters does exceptionally well and Hawks has directed them splendidly.

Once Hawks turned it into a male-centered plot, he could indulge in the gay-play that would crop up in his later work. A title points out that “When a roommate takes a girlfriend, he becomes only half a roommate.” One of the boys hangs up on his girlfriend in order to chat up a sexy dame strolling by, but she turns out to be a frat brother in drag (the same Sammy Cohen playing Callahan frère in Upstream). Still, the gags provide equal-opportunity innuendo, as when Louise Fazenda flounces in from a massage and is asked “What have you been doing?” She replies: “I’m not doing, I’ve been done.”

Visually the films are remarkably similar. Removed from Monument Valley, Ford doesn’t give us vistas, deep focus, or even scenes organized around doorways. At home in sparky comedy, Hawks doesn’t provide the graceful, pell-mell staging we get in Twentieth Century and His Girl Friday. Instead, we have classical American silent technique, already by the early 1920s quite polished (as can be seen in the 1922 Ritrovato entry from another master, The Real Adventure by King Vidor).

This silent technique turns out rather talky. Dialogue titles constitute seventeen percent of the shots in Upstream and sixteen percent of the shots in Cradle Snatchers. This isn’t a late 1920s development, since The Real Adventure contains nearly twenty percent dialogue titles. Why are these figures interesting?

The 1920s, the era of the “mature silent cinema,” led many filmmakers and critics to expect that filmmakers would shift toward purely visual methods of storytelling. Keaton’s Our Hospitality (1923), Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924), and Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925) remain dazzling exercises in getting maximum impact from the flow of images, with dialogue titles adding another layer of dramatic interest.

Ideally, the aesthetes thought, one could make a film entirely without titles. German films like Der letzte Mann (1924) are the most famous examples, but there were American experiments along these lines too, such as The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921). The arrival of sound threatened this trend toward “purely cinematic” narration. Now, critics fretted, filmmakers would be forced to rely on language to make dramatic points. The visual side of cinema would be secondary to “theatrical” methods.

Actually, however, alongside the consummate pictorial storytelling of Keaton, Lloyd, Lubitsch, and others, something else was happening. During the 1920s, quite a lot of American cinema became dependent on language. This happened, paradoxically, because of what critics then and since called the increasingly “cinematic” qualities of movie storytelling.

Not having either Cradle Snatchers or Upstream available for illustration, here’s an example from a film not playing here. In Henry King’s Winning of Barbara Worth (1926), Holmes the engineer is calling on Barbara before he sets out on a mission. He tells her that he plans to go back east, and he’d like her to join him. He’ll be back in a week for her decision.

At the purely imagistic level, the scene is presented in standard continuity, with a long shot establishing the kitchen, then a series of reverse-angle medium-close shots of Holmes and Barbara as they talk flirtatiously.

The conversation is interrupted by a cutaway to Abe outside, coming in the gate, which serves as a transition to a two-shot of Holmes and Barbara.

It’s from that framing that Holmes leaves, and she lingers at the doorway.

But the scene is even more broken down than this. Of its twenty-eight shots only eighteen are images; the other ten are dialogue titles. They are sandwiched in between the tight singles of Holmes and Barbara, as here:

In effect, breaking the scene down “cinematically” into close views of each character may seem to pull cinema away from theatre. Yet it works to frame and underscore each line of dialogue. The pattern is speaker/ title/ speaker. Even the more distant shots, like the opening establishing shot and the final two-shot framing, are broken up by inserted titles.

Across the 116 seconds of the passage, nearly 36% of the shots consist of dialogue. Of course this proportion wouldn’t be sustained across the whole film, since many sequences are filled with physical action and have no conversation. But in this and many other films American directors were creating a silent-film dramaturgy that incorporated dialogue into the texture of the cutting. Dialogue titles became editing units that could maintain a rapid pace and, combined with legible singles and two-shots, made for cogent storytelling.

This is what happens in Upstream and Cradle Snatchers. They are dialogue-driven vehicles (one a short-story adaptation, the other taken from a play), and both Ford and Hawks, idiosyncratic stylists in other genres and at other times, accept the dominant norms of their moment for these projects. These films employ speaker/ title/ speaker cutting, the singles and firm two-shots, and the careful eyeline matching. In fact, Ford uses a clever “impossible” eyeline match when the ham star looks up from the dinner table and the answering shot shows the distraught Gertie in her room upstairs, looking down, as if at him.

So were films like Upstream, Cradle Snatchers, The Real Adventure, and The Winning of Barbara Worth “preparing” for sound? In the sense of underscoring dialogue, yes. But the detailed breakdown into singles was not the most common option in most talkie scenes, at least in US cinema. (Japan is another story; cf. Ozu’s 1930s films.) The default for most scenes was the two-shot framing, with characters conversing within a sustained shot. This strategy is present at the end of our Barbara Worth scene, and it can be found throughout 1920s cinema. In other words, given the choices already established during the 1920s, sound-era filmmakers usually preferred the two-shot over singles. Accordingly, the cutting rate slowed down in most sound cinema. (The over-the-shoulder shot, a sort of single-plus, was another fairly rare option in the 1920s, but that too came into its own in the talking film.)

As often happens, Hollywood style offers a menu, with some options becoming more common at different periods. For sound filming, directors relied upon what had been an alternative option in the silent era, the two-shot. They saved singles for key moments. Today, with the dominance of what I’ve called intensified continuity, we seem to be back in the late 1920s. Filmmakers are inclined to present a line of dialogue with a tight single of the speaker, as happens in the Ford, Hawks, Vidor, and King films–but this time, of course, sync sound does duty for the intertitles.

This is one of the things that Ritrovato does best—provoke you into seeing new connections and trying out fresh ideas. Of course, it shows you a wonderful time in the process.

Kristin’s 2010 blog entry on Capellani is here. She will update it and write a new one after she’s assimilated the Ritrovato experience. The Variety review of Cradle Snatchers is from 1 June 1927, p. 16. We discuss dialogue intertitles in American cinema throughout The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), particularly in the chapters written by Kristin.