Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

No coincidence, no story

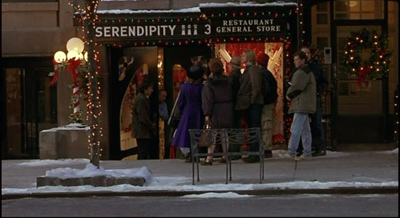

Serendipity.

DB here:

I’ve been thinking about coincidences lately. Watching Hong Kong movies can do that to you.

Hong Kong vs. Hollywood?

Initial D; I Corrupt All Cops.

In Initial D (2005, Andrew Lau Wai-keung and Alan Mak Siu-fai, script by Felix Chong Man-keung), the protagonist Takumi is dazedly in love with the seductive schoolgirl Natsuki. Takumi’s pal Itsuki is out with another girl when he spots Natsuki riding out of a “love hotel” with an older man. Itsuki tells his pal. This leads to a major crisis, in which Takumi’s faith in Natsuki is shaken.

Then there’s I Corrupt All Cops (2009) from the indefatigable writer-director-producer-actor Wong Jing. (Many wish he were far more fatigable.) Unicorn, a corrupt, brutal police officer, has just been savagely beaten by gamblers who once were his allies. He staggers to a street stall and nearly collapses, spitting blood into his congee. Then he glimpses his girlfriend getting out of a rich man’s car. In the next scene, when he visits her apartment, he finds his boss, the even more corrupt cop Lak, in her bed. His realization that he can trust no one pushes him to join the police anti-corruption unit.

True, the coincidences play different roles in the two movies. In Initial D, there might be an innocent explanation for Natsuki’s visit to the hotel. Perhaps Takumi’s friend even mistook another girl for her. So we may be inclined to suspend our judgment and wait for more information about whether she’s actually being unfaithful. In I Corrupt All Cops, Unicorn’s suspicions about his girlfriend’s disloyalty are immediately confirmed; instead of suspense, we get surprise, in the form of the revelation of who her lover is.

But in each case, a major plot movement is triggered by sheer accident. Itsuki wasn’t spying on Natsugi’s assignation; he was trying to talk his date into the love hotel. Unicorn wasn’t suspicious of his girlfriend, he just happened to be across the street when she came home. Each coincidence is also a matter of timing: Had either man come a few minutes later to the location, he wouldn’t have learned the big secret. In retrospect, we are likely to think that the screenplays of Inital D and I Corrupt All Cops are using chance rather than causality to move their action forward.

Granted, Hong Kong films are generally weak in plot construction. Even the lauded films of Wong Kar-wai are built out of casual encounters and unpredictable turns of events. The old Chinese maxim “No coincidence, no story” might seem to give accidental revelations a high place in this cinema. But Hong Kong films aren’t outstanding offenders. When you start to look, you find that films in different traditions are no less committed to coincidence. After all, Rick in Casablanca notices the vast implausibility of what’s just happened: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

One precept of Hollywood screenwriting has been that coincidences are permissible when you’re setting up the narrative. Indeed, they’re often necessary: Circumstances have to come together in some way to launch an extended action. A sudden rainstom brings boy and girl together under the same awning, creating the cute meet, and things can build from there.

But, the Hollywood wisdom goes, don’t use a coincidence to develop or resolve the plot. Consider another Hong Kong film, Infernal Affairs (2006, directed by Lau and Mak, with script by Chong). Chan the undercover cop has come in from the cold. While officer Lau is out of his office, Chan is poking idly around Lau’s desk. There he finds the envelope on which Chan himself once scribbled a correction.

That envelope was in the hands of the gang that Chan joined. If Lau has that envelope, he must be the triad mole in the police force. This recognition triggers the film’s climax: Chan flees police headquarters and sets out to unmask Lau’s treachery.

You would think that if Hollywood filmmakers were anxious to avoid such a timely accident, the Infernal Affairs remake known as The Departed (directed by Martin Scorsese, script by William Monahan) would find another way for Billy Costigan to discover that Colin Sullivan is the mole. But no. Billy notices the telltale envelope sticking out from a pile of papers on Sullivan’s desk.

The different ways the two films drive the discovery home to the audience merit a closer look than I can spare here. My point is that the handy coincidence of the police mole leaving this damning clue for his adversary to find is used without apology in the Hollywood movie. And like its counterpart, the scene sets off the movie’s climax. You could even argue that Infernal Affairs supports its revelation a little better. Billy accidentally glimpses the crucial envelope, but Chan is actively browsing Lau’s desk, perhaps because after years spent among triads he doesn’t trust anyone .

So you have to wonder. Maybe filmmakers in many traditions have accepted the Chinese maxim. Moreover, contrivance of this sort doesn’t seem to damage a film’s reputation. (Many critics considered The Departed one of the very best US films of 2006.) More generally, we seldom feel such coincidences to be arbitrary or forced. Maybe screenwriters and directors have found ways to mask the coincidental tenor of such scenes.

As with our earlier Inception entry, we’re in the realm of motivation.

The roots of coincidence

Most story actions result from characters’ choices, purposes, reactions, plans, and the like. These factors create patterns of cause and effect. Chan/Billy didn’t just mosey into Lau/ Colin’s office: He came in because he thought it was safe to break his cover. We accordingly worry for him because we know, as he doesn’t, that he’s far from safe.

Everyone seems agreed that a plot can’t replace all causal connections with a string of coincidences. If everything happens by convenient accident, then we can’t form any expectations about what will happen next. And without expectations, our cognitive and emotional engagement with the story is likely to be slight. Moreover, designing a story packed with coincidences isn’t that hard. Children do it all the time. But most artistic traditions thrive on their constraints. If anything at all can happen to advance or conclude your plot, you’re playing tennis without a net. The interesting challenge for a storyteller in traditional forms is to create a pattern of incidents that arouses our curiosity, builds up suspense, and presents surprises that turn out to be, in retrospect, cunningly prepared for—all the while playing on our emotions.

Yet, and again: No coincidence, no story. Sometimes, the plot’s forward momentum needs encounters and discoveries not planned by the characters. So how can these convenient accidents be made to serve narrative craft?

Well, what is a coincidence anyway? At the least, it’s a matter of converging incidents, as the name implies; but surely it involves more.

I wake up one morning and ask, “I wonder what my sisters are up to? I haven’t heard from them in a while.” Nothing important is happening in the family, no health crises or upcoming reunions. I just wonder how the girls are. So I reach for the phone, but before I can dial I get a call from Diane (the Texas sister). I say, “What a coincidence! I was just going to call you.”

This sort of thing happens. But not all the time. Not even most of the time. The thousands of things that flit through our day almost never match up so nicely. And we don’t notice it when they don’t match up, because we don’t expect them to. The non-coincidences of everyday life go unregistered because they’re so pervasive.

On those rare occasions when things do sync up, we notice. In The Evolution of God, Robert Wright puts it well:

It makes sense that human brains would naturally seize on strange, surprising things, since the predictable things have already been absorbed into the expectations that guide them through the world; news of the strange and surprising may signal that some amendment of our expectations is warranted.

We usually attribute such coincidences to chance. But humans aren’t very good at thinking about chance. If the coincidence seems meaningful, as many do, we’re always tempted to consider it the result of some secret force. Did I send out invisible thought-waves that Diane somehow picked up? Did fate, or God, make her call me? In general, when we notice patterns, we look for causes. The phone-call convergence is a pretty minimal pattern, but even there we might be tempted to find a cause.

I hang up on Diane and the phone rings immediately. It’s Darlene (the peripatetic sister). “I was just trying to call you, David, but the line was busy.” This is getting weird. The pattern heightens and may prompt a stronger impulse to search for causes. Do we three siblings mind-meld in some mysterious fashion? (If so, though, why do we need phones?) It’s just a coincidence, highly improbable but, out of all the times we three think about one another and make phone calls, not impossible.

I believe that narrative artists in all media are practical psychologists. They trigger and exploit and heighten our ordinary ways of making sense of the world. Philosophers and statisticians have sophisticated ways of thinking about chance, but they needed special training to get beyond our folk psychology. Artists take us as we are.

Stories can use coincidences because we accept them. They are the sorts of things that sometimes happen, and so, as Aristotle argued, they are fit subjects for plot-making.

The poet’s task is to speak not of events which have occurred, but of the kind of events which could occur, and are possible by the standards of probability or necessity (Poetics, Chapter 9).

Here Aristotle points to two sorts of possible events. There are events that we expect to happen as a necessary result of earlier events; this corresponds to some notion of causality. Then there are events that are merely probable—things that are likely to happen.

But how likely is my call from Diane and the followup from Darlene? Aren’t these examples of what Aristotle dismisses as “the arbitrary and fortuitous”? Not necessarily, because for Aristotle too the storyteller is a practical psychologist. Things that seem unlikely, he says, can be motivated by reference to people’s beliefs or to the fact that improbable things are likely to happen occasionally.

Irrationalities should be referred to “what people say,” or shown not to be irrational (since it is likely that some things should occur contrary to likelihood) (Poetics, Chapter 25).

In sum, how do you motivate a coincidence? Aristotle recommends two tactics, which I could use if I were writing a story featuring the felicitous phone calls. People say that members of a family have a special affinity that can cross time and space. And anyhow, stranger things have happened.

Narrative norms

SPL.

Aristotle suggests a third motivational tactic as well. He says that unlikely things may be resolved “by reference to the requirements of poetry.” Poetry here refers to any verbal artform, just as poet refers to the maker of literary works in general. So what are the “requirements” of storytelling?

Most minimally, a plot needs an inciting incident. If I were a fictional character, my lucky phone calls might kick off a plot in which my sisters and I, feeling a new and mysterious bond, set out on road trips to meet somewhere. The telephone contrivance would correspond to the Hollywood dictum that coincidences are permissible at the outset of the plot.

Many commentators on Aristotle take his mention of poetic “requirements” to involve more specific conventions, especially those of different genres. We’ve long known that certain kinds of art works permit things that would be forbidden in other kinds. A children’s movie is unlikely to show chainsaw dismemberings, unless Eli Roth has been given a producing deal at Pixar. This idea of genre fitness or decorum has implications for coincidences too.

Clearly, coincidences flourish in comedy. The innocent young man trapped in a lady’s boudoir will have to hide under the bed because her husband bursts in at an awkward moment. In the long chase sequence through old Hong Kong in Project A (1983), Jackie Chan keeps bumping into his superior officer. Sometimes Jackie is set back by the encounter, but once the officer inadvertently rescues him. David Lodge writes: “Audiences of comedy will accept an improbable coincidence for the sake of the fun it generates.” His novel Small World culminates in a pile-up of coincidences in which an airline check-in clerk happens to give the heroine a copy of The Faerie Queene at the precise moment she needs to check a literary reference.

This is all highly implausible, but it seemed to me that by this stage of the novel it was almost a case of the more coincidences the merrier, provided they did not defy common sense, and the idea of someone wanting information about a classic Renaissance poem getting it from an airline Information desk was so piquant that the audience would be ready to suspend their disbelief.

Melodrama is another genre that relies on coincidences, particularly those that bring bad luck. (Think of Rock Hudson’s cliff-edge fall in All that Heaven Allows.) Likewise, I think that the revelations of the incriminating envelopes in Infernal Affairs and The Departed are partly motivated by genre conventions. In undercover tales, the detectives have to be alert for any physical items that might betray them or offer clues. So the envelopes are something that the hypersensitive narc could plausibly fasten onto. (Why the envelopes are left lying around in the first place is another part of the story, which I’ll come to.) Similarly, Initial D is partly a teenage romance, and we know that such films require an obstacle to happiness; that’s what Itsuki’s accidental discovery provides.

There’s another “requirement” of poetic art that can motivate coincidence, and it cuts across different genres. In Wilson Yip Wai-sun’s SPL (2005), a brutal martial-arts fight in a nightclub ends with the gangland chief Wong Po hurling Inspector Ma through a window far above the street.

Down below in a waiting car are Wong Po’s wife and baby son, the only things in life he loves.

Care to have a guess where Ma lands?

This is a coincidence motivated by poetic justice: The brutal Wong Po has inadvertently killed his wife and child. Serves him right!

As we might expect, Aristotle anticipated poetic justice too. He remarked that there was a special sense of fitness when the statue of a murdered man toppled over on his killer.

Three dimensions of narrative

Casablanca.

In an essay in Poetics of Cinema I argued that we can think of any narrative as having three dimensions: the story world, the macrostructure of the plot, and the narration–the flow of information as it’s presented, moment by moment, in the film. Each of these dimensions can motivate coincidence, and each answers to what Aristotle calls “requirements” specific to narrative art.

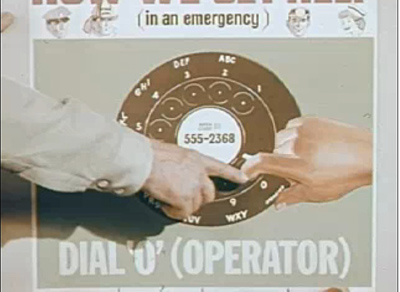

Say you want two characters to meet without making a rendezvous. One way is to establish that each has a routine. Jack stops for coffee at Starbuck’s every morning on the way to work; so does Jill. Sooner or later, it’s plausible that they will run into each other. The appeal to routine is probably behind the unlucky coincidence in I Corrupt All Cops. After being beaten, Unicorn staggers to the food stall across from his girlfriend’s apartment house–evidently on his way to call on her.

Another sort of story-world motivation involves characterization. In Initial D, it’s not implausible that the randy Itsuki would be hanging around outside a love hotel. Given his personality, he’s more likely to see Takumi there than other, more upright characters would be. In Infernal Affairs, Lau is a cautious mole, but he has no reason to hide the telltale dossier because he thinks it would be meaningless to anyone else. (Lau can’t know that Chan is the one who scribbled the corrected spelling on the envelope.) Lau’s studied nonchalance lets him stack papers on his desk without concern that this one is particularly revelatory.

Coincidence can also be motivated by the overall plot structure. If you start your film by alternating scenes showing two characters living their lives separately, you make it easier for your audience to accept what might otherwise seem a chance meeting between them later. After all, if they aren’t going to have some interaction, why are they both in this story? Sleepless in Seattle provides a clear-cut instance, although here the conventions of the romantic comedy genre also insist that the couple will get together. (Vera Chytilová’s Something Different of 1963 shrewdly defeats the expectation aroused by this sort of alternating construction.)

Likewise, a flashback structure can motivate coincidences. If we’ve seen the outcome of an action, even implausible events leading up to it can seem more natural. At the start of The Big Clock (1945) we see a hunted man hiding in a vast clock mechanism that surmounts a skyscraper.

In a long flashback, we see what led up to Stroud’s plight. Fired from his magazine job, he meets up with a blonde woman who takes him bar-hopping. They wind up in her apartment, but she hurries him out just as his boss Janoth comes in. Stroud watches Janoth go into the woman’s apartment.

The encounter isn’t wholly accidental. We know, as Stroud does not, that the woman is Janoth’s mistress, and she knows Janoth is coming to visit her. Nonetheless, what happens next leads to Stroud’s being fingered for murder. Stroud has pretty bad luck, but the opening frame story of his flight retroactively motivates his presence at the crime scene; we wouldn’t have the clock scene unless it proceeded, as Aristotle might say, by necessity from something pretty serious. The order of presentation coaxes us to accept whatever led up to the opening situation.

The story world and the plot macrostructure can do only so much. Sometimes coincidences need more fine-grained motivation. Here’s where narration, the patterned flow of information, comes in. If a cowardly cowboy is just about to leave the saloon when the bullying gunfighter enters, it can seem less stage-managed if we show, beforehand, the gunfighter riding into town with his minions. It doesn’t make the encounter more plausible in the story world, but it prepares us to find it more plausible: the two paths seem to converge. Here crosscutting accomplishes on the small scale what alternating scenes can do for macrostructure.

An even simpler tactic is to have someone announce that what’s happening is extremely unlikely. Lodge points out the audacity of Henry James in The Ambassadors when he presents a major moment through a character who reflects, “It was too prodigious, a chance in a million. . . ” This is the equivalent of Rick’s comment about Ilsa dropping into his gin joint. A frank admission of a coincidence can pull you through.

It was meant to be

Many of these motivating factors can work together with a more sweeping one. Recall that we’re sometimes tempted to consider everyday coincidence the result, or sign, of forces larger than we can comprehend–God, karma, fate, the Sibling Affinity Frequency. A narrative can motivate its coincidences by suggesting that they are working out an elusive but powerful pattern. Somehow, coincidence is just the hand of destiny. The French film known in English as Happenstance (2000) provides an example, but so does Serendipity (2001).

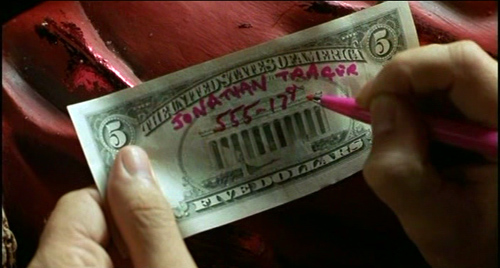

Jonathan and Sara meet cute in Manhattan, but mishaps separate them. They never learn each other’s identity. Years later, Sara is in San Francisco living with a musician, while Jonathan is about to get married. Vaguely dissatisfied and fretful, Sara returns to Manhattan to find Jonathan. Meanwhile, just before his marriage, he sets out to find her. Each one thinks that recapturing the love that flared up in one magical night would be worth one last effort.

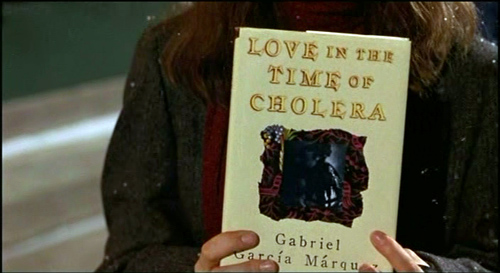

How do they find one another? Clues, plus coincidences. Jonathan starts to track Sara through a sales receipt for gloves she bought when they first bumped into each other. Sara returns to the Waldorf and visits “their” café in hope of finding some connection to Jonathan. But a lot of luck is involved too. Jonathan confirms Sara’s location thanks to her inscription in a used copy of Love in the Time of Cholera–a copy that his fiancée gives him, no less. By chance she bought Sara’s copy. Correspondingly, Sara finds the $5 bill Jonathan signed years before in her friend’s purse. Her friend got it as change at the café. The characters take purposive action, but they achieve their goals through coincidences.

These coincidences are simply outrageous. How can we motivate them? At the beginning of their magical night Sara announces that she believes that happy accidents are in fact controlled by fate. If she and Jonathan are meant to be together, things will arrange themselves the right way. She tells him this as they have coffee in her favorite café, Serendipity.

So Sara mounts some tests of their cosmic compatibility. She insists they leave the café separately: if they’re destined to remeet they will. Jonathan leaves his scarf behind, and she finds it, so they’re back together. She writes her contact information on a scrap of paper, but it blows away. “Fate’s telling us to back off,” Sara warns. Jonathan writes his phone number on the fiver, but she then pays for something with it, saying that if it returns to her, she’ll call him. In exchange, she’ll write her information in the Márquez novel and give it to a used bookshop; if he finds it, he can call her. Finally, at the Waldorf Astoria, each one is to get in a separate elevator car, pick a floor, and see if they’re in synch. It’s this test that leads him, through problems of timing, to lose her.

What motivates the cascade of coincidences, then, is the film’s starkly announced theme. In love, favorable coincidence is just serendipity; the film puts its operating procedure in Sarah’s mouth. To make your coincidences seem plausible, then, make your movie explicitly about how coincidences can be read as destiny.

But the theme doesn’t work on its own. Several of our other principles of motivation help out. For one thing we have Aristotle’s notion of common opinion: “What people say” about true love is that a couple is somehow meant for each other. In addition, of course, this is a romantic comedy, a kind of film that depends on separating and uniting lovers. We’d be very surprised, not to say disappointed, if these two didn’t wind up together. Genre helps motivate the way coincidences help out the couple.

Perhaps most interestingly, the “requirements of art” in Hollywood dramaturgy include a symmetrical play with motifs and character traits. Each lover is given a token—$5 bill, Márquez novel—and certain locales gain significance through repetition (Bloomingdale’s, the Waldorf, Serendipity, the skating rink). At the start of the film, Sara is the romantic, while Jonathan is more pragmatic. After a few years as a psychotherapist, however, she no longer trusts in fate. But by searching for her, Jonathan becomes a passionate believer in signs, reading everything around him as a possible trace of her presence. His pursuit of a love that defies likelihood moves his friend, the journalist Dean, to write a hypothetical obituary:

Even in certain defeat the courageous Trager secretly clung to the belief that life is not merely a series of meaningless accidents or coincidences. Uh-uh. But rather it’s a tapestry of events that culminate in an exquisite, sublime plan.

That plan is worked out through a traditional plot symmetry. Sara had found Jonathan’s scarf in the café at the start. At the climax, he discovers her jacket on a bench overlooking the ice rink where they shared their first date. (She had gone back there in a nostalgic mood earlier in the day.) Now, coming back for her jacket, she reunites with Jonathan. Hollywood’s use of tokens and props to develop the drama fits nicely with the theme of fate’s good offices. You could say that the vicissitudes of destiny are recruited to motivate some principles of classical plot construction.

Time out

You may dislike all the films I’m mentioning (Serendipity?! That’s a movie for wimps!). But my purpose here isn’t evaluative. I want to explore some principles that are used to make stories hang together, more or less. The same principles are present in what we sometimes call art films, from Bicycle Thieves to The Headless Woman. Coincidences abound in these movies, often motivated as the randomness of life, or n-degrees-of-separation, or mysterious larger forces that create correspondences (Paris nous appartient, the Three Colors trilogy of Kieslowski). Appeal to realism, to folk psychology, to genre, to thematic significance, and to formal unity can be found in virtually all narrative cinema. Here as elsewhere, I’m just trying to make such principles explicit and study how they work.

In thinking about those principles, I’m struck by one more way in which narratives need coincidences. What makes a story intriguing, or even worth paying attention to?

Here’s a story. I got up this morning, had breakfast with Kristin, went to school to take some frame enlargements from Hong Kong films, and dropped off the slides at a lab before coming home. Technically, it’s a story, but you yawned halfway through. To be engaging, stories need a remarkable situation or twist—a lover betrayed, a man pursued for a crime he didn’t commit, a cop discovering that his savior is his worst enemy, people who meet and fall in love and then lose one another.

We need, in short, something out of the ordinary. Coincidences, popping out from the bland backdrop of everyday life, can provide an uncommon event. At the start of a plot, they launch the action. At intervals, and with the proper motivation, they can be invoked if they liven things up. The effect may go back to the strangeness that Robert Wright suggests that we’re always on the lookout for.

Granted, the effect of motivation is to make coincidences seem less strange than they might otherwise seem. Most of these factors work to give the coincidences a sort of causal boost. Itsuki sees Natsuki because he’s at the love hotel, Chan/ Billy notices the envelope because he’s an alert cop, Jonathan and Sara get together again because they follow up clues and try really hard and anyhow an unseen hand (causally) shapes their fate, and so on. The coincidences are often covered by a causal alibi. That suggests that what’s most coincidental in these situations is timing.

Most movie coincidences run on tight schedules. A few moments later, Itsuki wouldn’t have seen Natsuki leave the love hotel; Unicorn wouldn’t have caught his wife with his boss; Chan/ Billy wouldn’t have found the telltale envelope; and so on. As the film unrolls, we want our extraordinary events tied to close shaves, barely missed messages, and revelations taking place under a ticking clock.

Every moment in filmic storytelling seems to bristle with possibilities of convergence and revelation. The sort of actions that make stories interesting are even more gripping if they take place under time pressure. Very often, if a key event had happened slightly earlier or later, there would have been no coincidence. And movies, unrolling at a pace to which we all submit, are well-suited to arouse our interest with turns of events that might, just barely, have been very different. Perhaps we accept the power of good or bad timing because, to recall Aristotle, “people often think” things like this: If I had missed that train, I would never have met my soul mate. . . .

Clearly, though, timing is a tale for another occasion.

My thanks to Ben Brewster for discussing these ideas with me and reminding me of the Chinese adage. That precept is briefly discussed in Kam-ming Wong, “‘No Coincidence, No Story’: The Esthetics of Serendipity in Chinese Fiction,” International Readings in Theory, History and Philosophy of Culture (St. Petersburg, Russia: EIDOS, 2003), Vol.16, 180-97.

My references to the Poetics come from Stephen Halliwell’s edition, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), pp. 40, 42, and 63. My extracts from David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction (New York: Viking, 1993) are from his section on coincidence, pp. 149-153.

Hilary P. Dannenberg’s book, Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) includes many intriguing ideas about coincidence. Her focus is the “coincidence plot” in which people realize they’re related to one another. Some of her arguments are presented in more compact form in her article, “A Poetics of Coincidence in Narrative Fiction,” Poetics Today 25: 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 399-436.

P.S. 31 September: In a study of The Pledge, film scholar Gary Bettinson has a valuable discussion of how coincidence can be motivated to resolve a plot. It’s available here.

Serendipity.

INCEPTION; or, Dream a Little Dream within a Dream with Me

Kristin here:

Inception reminds me of the common claim that Hollywood films are no longer character-centered. Special effects and slam-bang action supposedly have replaced character traits as the basis for storytelling. Now, here is a contemporary film released as a summer tentpole film and definitely successful in box-office terms. It crossed the $200 million domestic gross figure on Tuesday, August 3. Yet the nearly universal complaint, for those who don’t like the film, or some aspects of the film, is that we don’t get to know the characters.

If modern tentpoles have generally neglected characterization, that must be a convention by now. Why would people expect to find rounded characters? Is this complicated/complex (take your choice) intellectual film aimed at adults ironically going to prove that the critics of modern Hollywood blockbusters have been right all along?

I agree that the characters in Inception, apart from Cobb, the protagonist, are barely assigned traits. Ariadne, for example, does not return to join Cobb’s team as its architect because she has some personal goal or trait that inclines her to want to do so. It’s just that everyone who experiences the possibilities of shared dreams gets hooked.

But if there’s little characterization, is Nolan substituting something interesting in its place—apart from the usual computer-effects and spectacle? The first time I saw the film, I suspected he is, but for a long time I couldn’t figure out what. As a result, I did not really enjoy it until the point where the van breaks through the railing on the bridge and starts to fall. That’s pretty far into the film, 104 minutes in a roughly 140-minute film, not counting the credits. The van’s beginning to fall also marks the end of what we’ve called the Development portion of the film and the beginning of the Climax. (See here and here and here.)

At that turning point, it dawned on me that Nolan has elevated exposition of new premises to the main form of communication among characters. Discussion of their personal relationships, hopes, and doubts largely drops out. As the Russian Formalists would say, exposition, usually given early on and at wide intervals later in a plot, becomes the dominant here. That’s an unusual enough tactic to warrant a closer look.

We grasp most of the characters by the types of premises they provide. Yusuf is the man who understands how to manipulate the sedatives that will allows the team to progress deep enough into Fischer’s subconscious to plant the idea. Oh, yes, and he has a cat. Robert Fischer is the man who thinks his father despised him, so he is susceptible to the team’s machinations to plant the idea in his subconscious. (Saito says that Fischer has a “complicated” relationship with his father, but it’s actually just the opposite: a single trait, which is all that’s needed to establish his part in the action.) He also seems to be very concerned with security, since his subconscious conveniently peoples the dream levels with bodyguards who provide obstacles, fatally wound Saito, and force the van off the bridge, among other functions.

The characters’ goals, apart from Cobb’s, arise from the premises of the dream-sharing technology. Of course, they want to get paid, but that’s assumed. Their actions all arise from the need to keep doing what they must to sustain the dreams and later from the need to improvise solutions to unforeseen problems that seem to violate the rules they have previously known. Why they need the money, whom they go home to when off-duty, how they got into this business, and all the other conventions of Hollywood characterization, are simply ignored. Even Saito’s claim that Maurice Fischer’s corporation is dangerous to the world because it controls so much of its energy sources is simply assumed to be true. Our possible suspicions that Saito himself might really be the more dangerous tycoon, out to eliminate a powerful rival, might add a little complexity. The film, however, never hints at such a possibility.

Ariadne is somewhat different in her function. As in so many Hollywood films, there are two lines of action. First, there is the attempt to perform inception in Fischer’s subconscious. Second, there are Cobb’s related goals of getting back to his children but also of holding onto his dead wife through his visits to his projection of her in dreams. No one besides Ariadne fully understands Cobb’s obsession with Mal and hence she alone sees the danger it poses to the team. Ariadne lives up to her ancient namesake, guiding us through the maze of the Cobb’s obsession by acting as an expository figure in that storyline.

That is presumably why she doesn’t simply tell Arthur, who is much more experienced than she is in sharing dreams, about Cobb’s dangerous obsession. Instead, she decides to go into the dream levels as part of the team to keep on eye on Cobb—thus allowing her to continue as a privileged witness and transmitter of vital information about that storyline.

Each new premise creates a link in the chain of actions, and for the most part the actions are governed by the rules, or apparent rules of the dream-sharing machine, the sedatives, the levels, the characters’ respective skills, and all the other factors.

The narration constructs its causal chain by being nominally omniscient. For short stretches of the film we may be “with” Ariadne and Cobb or Mal and Cobb and witness them having personal conversations, most dramatically when Cobb fails to talk Mal out of leaping to her death. These moments provide the main alternative to the exposition-ridden dialogue, and they are a very small portion of the overall speech in the film. Yet the narration arches over all, stitching together the series of causes by moving us among the levels, catching at exactly the right moment the critical action (Arthur is putting a stack of dreaming people into an elevator) or dialogue (Cobb is asking Ariadne where she designed a route bypassing the labyrinth in the hospital).

Once I realized that this film’s plot concerns fiendishly complicated action that requires almost constant exposition from the characters, I enjoyed the rest of it. I saw it a second time and enjoyed it even more. I certainly don’t understand the entire plot, and I suspect that’s partly because, despite the nearly constant revelation of premises, there were a few left out. For one thing, just how does Eames, the “forger,” manage to change into other people? (No mention of polyjuice potion or anything else.) I can understand how he might do it in his own dreams, but the one dream where he doesn’t change is his own. Even the guides to Inception that have already been posted on the internet don’t answer every question. (Here and here are two examples of many.) Perhaps when the DVD comes out, the answers will be forthcoming—more of them, but probably not all.

In the meantime, I don’t see why we should get annoyed because Inception doesn’t contain rich, fully rounded characters. It’s clearly a puzzle film that takes the usual complicated premises of a heist movie and pushes them to extremes. Accepting the flow of nearly continuous exposition may remove some of the frustrations viewers face. After all, there’s no rule against it.

DB here:

When an actor comes to me and wants to discuss his character, I say, “It’s in the script.” If he says, “But what’s my motivation?”, I say, “Your salary”.

Alfred Hitchcock

Forget dream stuff for a while. Yes, Nolan says he was interested in dreams, especially lucid dreaming. Yes, he claims that the precision of detail in the film was an effort to suggest how “real” dreams feel when you’re having one. And yes, critics have defended the films’ dream worlds as realistic, or attacked them as phony substitutes. All interesting points and worth exploring, but not my focus at the moment.

And forget videogames. I leave that stuff to the experts, such as several members of our Wisconsin Filmies listserv. They have kindly pointed out many analogies and disanalogies. (See the coda for specifics.) And of course there’s no shortage of commentary about the film’s ties to gaming, or dreaming, on the Net.

My focus instead is motivation. Not the sort that Hitchcock and Bergman talked about, but rather the idea that any artwork needs to justify certain elements or strategies it presents.

Motivation beyond Bergman

You want your movie to have musical numbers. How to justify them in your story? Many early musicals simply make the characters show-business types, so we see them rehearsing and performing numbers for the audience. Other musicals cast that “realistic” motivation aside and let the characters sing and dance wholly for one another. But then those films were appealing to a sort of motivation familiar from opera, where characters simply burst into song or dance without realistic motivation. We accept this type of artifice too because that’s just what this genre of film permits—the way that horror films include monsters that are unlikely to exist in the real world.

The notion of motivation turns a lot of our usual thinking about cinema inside out. Usually we think that something is present in order to support what the film “says.” But actually a lot of what we find in films is motivated, either by genre or by appeal to realism, in order to give us a particular narrative experience.

For a couple of decades, some American cinema (both Hollywood and indie) has been launching some ambitious narrative experimentation. We’ve seen “puzzle films” (Primer), forking-path or alternative-future films (Sliding Doors), network narratives (Babel, Crash), and other sorts. This trend isn’t utterly new—there are earlier cases, especially in the 1940s—but it seems to have been accelerating in recent years, particularly after Pulp Fiction (1994). Christopher Nolan has participated in the trend as well, with Following and Memento.

The film industry encourages some degree of innovation. Novelty can attract attention, and perhaps audiences too. Yet, as I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It, such innovations are counterbalanced by traditional storytelling maneuvers. These make sure that audiences aren’t entirely lost. For example, Memento’s backward structure requires very explicit signposting of the transitions, highlighting objects or gestures we’ve seen in the previous time-slice to link them to the next one we see. At the same time, these experiments can pay off financially: a complex narrative that balances enigma and understanding can lure audiences to revisit the multiplex or buy the DVD for further scrutiny. Remember, we are all nerds now.

Memento illustrates a couple of ways in which Hollywood efforts at innovation are controlled by tradition. First, you can motivate a film’s formal play through genre conventions. A science-fiction film, for instance, can invoke time travel or alternate universes. Doc’s time machine in the Back to the Future series motivates a fairly unusual play with cause and effect, particularly in the second installment. Likewise, mystery and detective stories pioneered the “lying flashback,” when people give false testimony about a crime (as in Crossfire). The possibility that a film noir will encourage complicated narration (an optically subjective first-person narrator in The Lady in the Lake, a dying narrator in Double Indemnity, a dead one in Sunset Blvd.) helps us recognize that Memento is an experiment in that tradition.

Second, you can motivate formal experiment through the movie’s appeal to some widely-believed law of life, a common-sense realism. Uncanny coincidences in movies like Serendipity and Sliding Doors are justified by the notion that fate or spiritual harmony can bring soulmates together. Six Degrees of Separation’s plot exploits the idea of social networks. Likewise, the backward progression of Memento’s plot is partly justified by the clinical condition of short-term memory deficits. I grant you, why this ailment supports a reverse-chronology tale is a bit puzzling—but that may only suggest that we’re ready to overlook flimsy justification if the novelty is piquant enough. A little motivation can go a long way.

So we ought to recognize that Inception is relying heavily on motivation from these two sources, genre and commonsense realism. Science fiction grants the possibility of entering people’s dreams through a futuristic technology. Likewise, we have all experienced dreams, so the film can appeal to folk wisdom about them. I suggest, though, that the purpose of the film not to explore the dream life but rather to use the idea of exploring the dream life to justify creating a complex narrative experience for the viewer. That is the purpose of the film; the dreams operate as alibis.

Interestingly, traditions outside Hollywood don’t require these sorts of motivation for narrative experiments. Last Year at Marienbad is perhaps the supreme example of a purely artificial construct, which can’t be justified by genre or subject/theme. I’d argue that Kieslowski’s Blind Chance, Buñuel’s Obscure Object of Desire, van Dormael’s Toto le héros, and other films of a highly artificial cast either ignore or cancel both realistic and generic motivation. They present themselves as experiments in storytelling, pure and simple. Another art-cinema motivational ploy invokes psychological realism, as in Fellini’s 8 ½. This is less daring than the blunt-artifice option, and so has been more easily adapted to mainstream storytelling.

One more point about the New (or now Not-So-New) Narrative Artifice. Strategies that seemed striking in the pioneering films are quickly mastered by others. Innovations are copied, and the learning curve is steep. By now anybody can create a fairly coherent network narrative or forking-path tale. Artistically ambitious filmmakers want to press further. So how can you create fresh experiments in storytelling today?

Architecture beyond Ariadne

If you decide to organize a film in sharply distinct plotlines, you have two problems. First, how do you combine them? What will be the overall architecture? Second, how do you fill in the chain of actions?

Consider combination first. You can create parallel plotlines, as in Intolerance’s assembly of four different historical periods or in Vera Chytilová’s Something Different, in which two women living at the same moment lead very different lives. You can create branching or forking-path plotlines, as in Run Lola Run. You can link stories through a simple overlap, as in Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, or by letting them pass through the same place; the inn in Wong’s Ashes of Time functions as a sort of node that gathers together the destinies of different characters.

One sort of plot construction that hasn’t been explored deeply in recent years is actually one of the oldest. The embedded story, or the tale-within-the-tale, dates back at least to The Odyssey. In the standard case, we have one level of story reality, and in that a character tells a story that takes place earlier and elsewhere. Typically the embedded story is pretty extensive, with its own structure of exposition, development, crisis, and climax. You can of course multiply the stories, as in The Arabian Nights, The Decameron, and The Canterbury Tales.

Sometimes the framing story is merely a backdrop, though usually that has its own dramatic impetus: Scheherazade tells a story each night to postpone her death. Often, though, the framing situation carries the main interest. In Don Quixote, readers are tempted to skip the tales told by people whom the knight and Sancho encounter, in order to get back to the real story, the relationship of the central pair.

The “discovered manuscript” convention of nineteenth-century fiction was an equivalent of this pattern, a sort of novel-within-a-novel. Some experimental fiction has exploited the embedded story; I think of Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. The principle of embedding has been found in cinema too, of course. Citizen Kane is the classic example, since it embeds recounted stories (most of the flashbacks), a written text (Thatcher’s memoirs), and even a film-within-a-film (News on the March). Many of the embedded stories we find in films are presented as flashbacks, and those are usually motivated by a character recalling or telling another character about past events. (See our blog entry “Grandmaster Flashback” for some more discussion.)

The task of the author is to motivate the story’s presence through relevance to the framing situation. Why insert the tale in the first place? Most commonly, it involves some of the same characters we find in the surrounding story world, as in a flashback. In that case, the embedded tale supplies new information about plot or character. It may also provide a parable or counterpoint to what’s happening in the surrounding situation. In The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931), a woman is about to leave her husband, but she changes her mind when a family friend tells her, for the bulk of the movie, about the sacrifices made by the husband’s mother.

Some researchers might argue that the purest instance of this format is one in which the characters of the overarching frame story don’t participate in the embedded tale. Classic instances like the Mahabhrata are often studied as compilations. A partial instance in cinema is the country-house frame story of Dead of Night, in which some characters recount stories that didn’t involve them. Here the frame story arouses considerable interest in its own right.

Once you allow the possibility of an embedded story, some storyteller will ask: Why not embed a story into the embedded story? And so on. Calvino’s novel does this, suggesting the possibility of that infinitely extended series we see when somebody stands between two mirrors and the image is multiplied forever. (Inception gives us such an image when Ariadne summons up mirrors on a Parisian street.) Hollywood filmmakers experimented with multiple embedding in some flashback films of the 1940s. In The Locket and Passage to Marseille, there are flashbacks within flashbacks. More daring, and closer to Calvino, is Pasolini’s Arabian Nights, in which one character recounts a tale in which he encounters another character, who recounts his tale, and so on.

Here, I think, is the accomplishment of Nolan’s film. The general absence of complicated embeddings today (at least since The Matrix) presents an opportunity for an ambitious moviemaker. Inception constitutes an extended experiment in what you can do with a nested plot structure, motivated by the dream-invasion premise.

The Dream team

Nolan adds a new wrinkle. Instead of recounting or recalling stories, the characters enter worlds “hosted” by one of their number and furnished by another. The movie introduces this strategy to us obliquely. After the prologue in which Cobb confronts a very aged Saito in Limbo (which I think you can take as either a flashforward or a symptom of their collaborative dreaming at the moment), we are plunged into layers of embedding. In the real world, Cobb, Arthur, and the architect are dreaming with Saito on a train; we later learn that this is an audition to test Cobb’s extraction skills. They dream that they are in an apartment where Saito meets his mistress. But in that apartment they are sleeping, and dreaming that they are in a luxurious mansion where Cobb is trying to discover Saito’s secrets. That effort is disrupted by Mal, Cobb’s ex-wife, and the dream world collapses.

What’s tricky is that Nolan doesn’t establish these layers of embedding in customary order. The flashback tradition leads us to expect to move from outside to inside, like peeling an onion: from the train to the apartment to the mansion. Instead, we are first shown the mansion, and we get glimpses of the apartment. That tactic hints that the apartment is the primary level of reality in the fiction. But in the apartment Saito notices discrepancies in the carpet, making him realize he’s dreaming. Only then does Nolan shift to the external frame, the four men on the train, minded by a young Japanese passenger.

This has been our first training exercise, and it turns out to be based on surprise: We weren’t aware of how many embedded plotlines were in play. In the film’s terms, the dream session on the train went down two levels. Cobb says he can go down three, and that forms one goal for the team.

Later exercises are simpler, involving only shared dreams rather than embedded ones. That’s because these dreams operate as tutorials, as when Cobb shows Ariadne how dreamworlds are constructed and populated (though the framing situation is deleted at the outset–another, if milder, surprise). The dreams also function as psychological probes, as when Ariadne learns that Cobb’s unresolved problems with his wife are expressed in her eruptions into whatever dreamworld is conjured up. These études have to be relatively transparent if we’re to understand all the premises of this game. Similarly, our introduction to Limbo is given not through dream-penetration but through a good old flashback, when in the first-level dream world Cobb confesses to Ariadne that he and Mal built their own dreamscape there. Limbo changes the rules of the game to such an extent that we shouldn’t have to worry about who’s dreaming what for whom; a straightforward piece of visual exposition does the trick.

The most intricate embedding takes place in the final seventy-five minutes, most of the second half of the film. Instead of a train, a plane. Instead of four dreamers, six: the target young Fischer, plus all the members of the team, including Ariadne, who will monitor Cobb’s subconscious. Each team member hosts one story world, the other members enter it, and Fischer gets to populate it. Yusuf the chemist hosts the rainy car chase that leads to the van’s descent to the river. Arthur the point man hosts the hotel scene in which Cobb accosts Fischer. Eames the Forger (or rather the imposter) hosts the snow fortress siege, in which Fischer is induced to confront his dying father (thinking he is entering the dream of the family confidant Browning). Finally, to pursue Mal, Cobb and Ariadne plunge into the beachfront/ metropolis zone of Limbo constructed by the couple during their dream days. It’s then revealed that Cobb brought about his wife’s idée fixe by planting the idea that dreams could become reality; this showed him, with tragic consequences, that inception could work.

So we have five levels: the plane trip embeds the rainswept chase, which embeds the hotel, which embeds the snow fortress, which embeds the Limbo confrontation. The nested structure is recapitulated in the burst of shots showing Ariadne snapping awake in each level up to the submerged van (dream level 1).

Indeed, I think that one prime purpose of Nolan’s fancy structure is to foster such little coups. The Ariadne passage is cinematically simple—just a string of quick, graphically matched close-ups—but in context arresting. Of course that context displays a clockwork intricacy. What Nolan has done is created four distinct subplots, each with its own goal, obstacles, and deadline. Moreover, all the deadlines have to synchronize; this is the device of the kick, which ejects a team member from a dream layer. With so many levels, we need a cascade of kicks.

The last forty-five minutes of the film become an extended exercise in crosscutting. As each plotline is added to the mix, Nolan can flash among them, building eventually to four alternating strands—with additional crosscutting within each strand (in the hotel, Cobb at the bar/ Saito and Eames in the elevator/Arthur and Ariadne in the lobby). Each level has its own clock, with duration stretched the farther down you go. One thing that has long struck me about classical crosscutting is that in one line of action time is accelerated, while in another it slows down. The villains are inches away from breaking into the cabin/ the hero is miles away/ the villains are almost inside/ the hero is just arriving. I wonder if Nolan noticed this aspect of the crosscutting convention and built it into his plot, supplying motivation (that word again) by stipulating that different dream levels have different rates of change.

Another clever touch is what Nolan doesn’t include in the orgy of crosscutting: the framing situation in the first-class jet cabin. Once we leave that, we don’t see it again for about seventy minutes. I think we tend to forget about it, so that Cobb’s startled expression upon finally awakening mimics our own realization that all the intense physical action has been enframed by this quiet, stable situation.

I think that structurally, if not stylistically, the climax is a virtuoso piece of cinema. It recalls Griffith’s Intolerance, which also intercuts the climaxes of four plotlines, and supplies crosscut lines of action within each line as well. Here, one might say, is one way to innovate in the New Narrative Artifice: Create something like the Intolerance of the twenty-first century.

Possible, and not that unstable

The film is shameless in its regard for cinema, and its plundering of cinematic history. What’s fun is that a lot of people I talk to come up with very different movies that they see in the film, and most of them are spot-on. There are all kinds of references in there.

Also like Griffith, Nolan has hit upon some ways to make his innovation user-friendly. For one thing, as most viewers have noticed, he situates his levels in very different locales: rainy, traffic-filled city versus eerily vacant metropolis; cushy hotel versus more Spartan one; beach versus mountains. This allows us to keep oriented during even the most rapidly cut portions. More subtly, Nolan has, deliberately or not, respected the limits of recursive thinking, or metacognition.

As shrewd members of a very social species, we are all good at mindreading, figuring out what other people are thinking. I know that Chelsea admires Hillary. We’re good at moving to the next level too: I know that Chelsea believes that Hillary wants to monitor Bill. And I know that Chelsea believes that Hillary suspects that Bill is smitten with Monica. If you drew this situation as a cartoon, you’d have one thought bubble inside another inside another, and so on—like the Russian-doll structure of the climax of Inception.

It turns out that our minds can’t build these nested structures indefinitely. We hit a limit.

Peter believes that Jane thinks that Sally wants Peter to suppose that Jane intends Sally to believe that her ball is under the cushion.

Robin Dunbar, whose example this is, suggests that most adults can’t handle so much recursion. His experiments indicate that the normal limit is at most five levels—just what we have in Inception (four dream layers plus the reality frame). Add more, and most of us would get muddled.

The filmmaker’s second big problem with modular plotting, I mentioned near the start, is how to fill in the plotlines. Let me suggest a general principle, at least for storytelling aimed at a broad audience: The more complex your macrostructure is, the simpler your microstructure should be. In Memento, the high degree of redundancy between memory episodes and the unusually heightened transitions help us track the backward layout of scenes. Similarly, all four episodes of Intolerance culminate in a race to the rescue—a device that was by 1916 immediately legible for audiences.

Genre plays a role in simplifying the modules too. Our efforts to make sense of Memento are helped by film noir conventions like the trail of clues, the deceptive allies, and the maneuvers of a femme fatale. Likewise, Griffith used the conventions of current genres to fill in the plotlines of Intolerance. The Christ story can be seen as a recasting of the many pious Passion plays of the first years of cinema. The Babylonian story and the Huguenots’ story rely on the established conventions of the costume pictures, including the French and Italian features that were popular at the time. (Capellani, discussed in an earlier entry, was one master of this genre.) And of course Intolerance’s modern story is pure melodrama, showing a young family pulled apart by the forces of urban poverty and bluenose reform. Griffith wove together not only four epochs but several genres.

So does Nolan in Inception. He recruits the conventions of science fiction, heist movies, Bond intrigues, and team-mission plots like The Guns of Navarone to make the scene-by-scene progression of the plot comprehensible. The iterated chases and fights keeps us grounded too, though you might wonder why Fischer’s subconscious projections all seem to have leaped out of a Bruckheimer picture. And of course you’ve seen many of the other images before, from the Paris café to the luxury hotel bar. Shamelessly clichéd, the image of kids playing in the sunlight immediately evokes fatherhood and family in any film.

I’ve already argued that the comparatively transparent training and exploration sessions in the middle of the film help us keep our bearings. Another handhold is the convention of the new male melodrama, the husband or boyfriend trying to come to terms with the death of his woman. The simple action movie, from Death Wish to Bad Boys, uses vengeance to ease the man’s torment. The more “serious” plot makes the man responsible in some degree for the woman’s fate. The emotional temperature rises as the male protagonist tries to fight his feelings of guilt, turning it outward to a perpetrator (as in The Prestige) or inward (as in Memento, and Shutter Island). The under-plot of Inception, driven by Ariadne’s curiosity, gradually reveals to us that Cobb gave Mal the fatal idea of dwelling in dreams.

Moreover, the rise of fantasy, science-fiction, and comic-book movies has brought a new interest in creating “worlds” with their own laws. Once you have Superman, you need a secret identity and Kryptonite and well-placed phone booths, not to mention a host of constraints on what can and can’t happen. Comic books supply not only a world furnished with characters and settings but also rules about conduct, morality, even physics. George Lucas, in his youth more of a comic-book reader than a cinephile, took over this principle of construction for Star Wars. Of course this idea of richly furnished, rule-governed worlds has been elaborated more fully in videogames. My point is that contemporary viewers are ready to ride with this as another convention of contemporary virtual-world storytelling, and this habit simplifies our pickup of the rules governing Inception’s embedded stories.

In sum, as ambitious artists compete to engineer clockwork narratives and puzzle films, Nolan raises the stakes by reviving a very old tradition, that of the embedded story. He motivates it through dreams and modernizes it with a blend of science fiction, fantasy, action pictures, and male masochism. Above all, the dream motivation allows him to crosscut four embedded stories, all built on classic Hollywood plot arcs. In the process he creates a virtuoso stretch of cinematic storytelling.

I could find faults. As in The Dark Knight, Nolan’s action scenes are clunky and distressingly casual in their composition and cutting. He is much better at mind games than spatially precise physical activity. Some dialogue could be pruned too. (What are you doing here? He loved you–in his own way. Something is happening…as we speak.) And I haven’t even posed the interpretive issues. Find a sympathetic young woman to exorcise the demonic wife you can’t quite abandon. Find a new father figure (Japanese mogul) to replace the old one (Brit architect). Use the spinning top to exemplify both change and stability, childhood and maturity, and/or the unending flux of narrative. As Kristin hints, the whole thing might actually be complicated rather than complex; instead of a dense but coherent cluster of principles we might have a shiny contraption, bolting on new premises as it hurtles along.

Nonetheless, if current excitement about this movie is any measure, Nolan has pulled off the big balancing act. The film is redundant and familiar enough to let most of us follow the main trajectories on the first pass. Yet it’s enigmatic, elliptical, and equivocal enough to keep many of us talking about it. . . and watching it again. Recidivism, thy name is Inception.

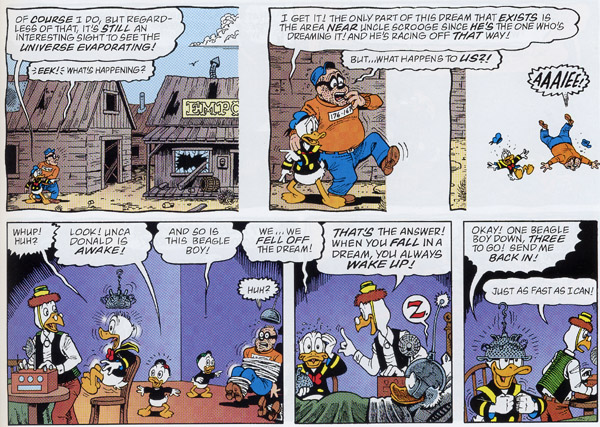

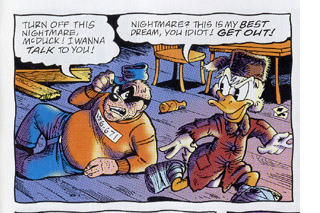

Based on Uncle Scrooge? That’s rich!

Kristin back again:

There has been much suggestion on the internet, sometimes in jest, sometimes in earnest, sometimes half in jest and half in earnest, that Nolan got the idea for Inception from an Uncle Scrooge comic story with a shared-dream premise, “The Dream of a Lifetime!” Nearly all postings on this subject date this comic, created by Don Rosa, to 2002. Yes, “Dream” first appeared in 2002—in Danish. It came out in the U.S. in the May, 2004 issue of Uncle Scrooge (Gemstone #329). In 2006, it was reprinted in Rosa’s book, The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck Companion.

A download of “The Dream of a Lifetime” is available online, but it is missing a page, so I’m not linking it here. The Companion volume is out of print but can still be purchased here. It contains Rosa’s “The Making of ‘The Dream of a Lifetime!’” “The Dream of a Lifetime” is included in the tenth and final volume of a series reprinting all of Rosa’s duck stories chronologically by their original appearance. The “Behind the Scenes” section at the back leads off with a revised version of “The Making of ‘The Dream of a Lifetime!'” Here Rosa mentions the theory that Inception was based on his comic tale. He saw the film only after reading about this on the internet and being skeptical of fans’ claims. His comment upon seeing the film is “And … whoa … I was no longer so dismissive of those internet theorists. There are so many elements in Inception that match aspects of my story very closely! Ah well–no matter.” (p. 175)

If Nolan got the idea from the Rosa tale, which seems unlikely, he certainly developed upon and changed it considerably. In fact, there are more significant differences than similarities.

First, the similarities:

1. In “The Dream of a Lifetime!” several people enter the dream by being hooked up to a machine. Here it’s a radio-controlled device invented by Gyro Gearloose, who intended for it “to help psychiatrists examine the dreams of their patients.” (Gearloose was created in 1952 by Carl Barks to provide whatever wacky invention his plots required.) The receivers are metal colanders wired as antennae and worn on the heads of the people sharing the dream.

2. Waking up from visiting the dream is triggered by falling (see below).

3. Characters in reality can attempt to insert objects or situations into the dream by making sounds or presenting objects for Scrooge to smell, though this usually goes comically wrong. This somewhat resembles the premise that the jolts of the van in the first dream level of Inception cause earthquake-like rumbles in the second level and so on.

4. The characters frequently explain to each other how the shared-dream technology works. Rosa makes this humorous in part by starting the story with Scrooge dreaming and the Beagle Boys arriving in his money bin with the Gearloose equipment, which they have already stolen. He then makes the exposition deliberately clunky and obvious. One of the stupider Beagles asks, “Sure … uh … tell me again how it works?” There are then several panels of explanation as the group arranges the equipment to enter the dream. As they are about ready, one remarks, “But I’ll explain later” how they will get Scrooge to tell them the combination to his vault.

5. All of the characters who enter Scrooge’s mind are aware that they are in a dream, as is Scrooge, who has had each of these dreams many times.

Now, the differences:

1. There is a single dreamer throughout, and Scrooge remains in his own bed.

2. There is only one level of dreaming, and Donald, who enters the dream to foil the Beagle Boys, returns at intervals to the bedroom to report progress and plan strategies.

3. Spatially, the dream extends only a short distance around Scrooge. If the characters move too far from him, it fades out, which Rosa represents by having portions of the panels go white. The Beagle Boys exit the dream, one by one, by falling into the white void (see below).

4. Scrooge’s dreams are essentially flashbacks, though they are altered by the other characters who enter the dreams. The plot passes through a series of seven recurring dreams, all based on real adventures Scrooge has had in the distant past. Each of the seven dreams derives from situations in Rosa’s The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck series. (The one-volume edition of this series is out of print, but it still is available in a two-volume version, here and here.) These dreams take place out of chronological order, and Scrooge’s age changes with each new dream. (The stories are “The Vigilante of Pizen Bluff,” #6, Scrooge age 23; “The Dreamtime Duck of the Never Never,” #7, age 29; “The Master of the Mississippi,” #2, age 15; “The Empire Builder from Calisota,” #11, age 45; “The Buckaroo of the Badlands,” #3, age 15; “The Last of the Clan McDuck,” #1, age 10; and “Hearts of the Yukon,” #8C, age 31.)

5. The rules are relatively simple. Crucially, Scrooge may be any age within the current dream, but he, being the main dreamer, recognizes Donald and the Beagle Boys.

5. The rules are relatively simple. Crucially, Scrooge may be any age within the current dream, but he, being the main dreamer, recognizes Donald and the Beagle Boys.

6. “Dream” is designed to be funny, as when the Beagle Boys keep complaining that they’re in a nightmare, while Scrooge thinks of them as pleasant dreams. This is normal life to such an adventurous character.

It should be clear that the complexity of Rosa’s story originates not from the shared-dream structure, which is fairly straightforward. Rosa is more interested in finding a way to rework some of the scenes from his earlier biographical Scrooge comics. The whole Life and Times project originated from Rosa’s working method of teasing out minutiae about Scrooge from the original Carl Barks stories and then concocting sequels or prequels to them. Life and Times is an attempt to use all the mentions of past events, relatives, locales, and dates to devise a biography of Scrooge. “Dream of a Lifetime!” carries that modus operandi one step further.

The other big difference between “Dream” and Inception is that a reader who was not familiar with the seven earlier stories would miss much of what goes on in “Dream.” It was written for McDuck aficionados as a sort of game of recognition. For those who do recognize the seven situations referenced, “Dream” is quite easy to follow. For those who don’t, it must seem complicated and mysterious, most crucially since they won’t recognize Glittering Goldie, Scrooge’s lost love, in the opening “private” part of the dream.

In contrast, Inception is self-contained and tries for a very different sort of game of comprehension with the viewer, one which would not be aided by knowledge from other Nolan films.

“Dream” is also recognizable to fans as another of the “trick” stories that Rosa has written occasionally. These are not linked to Barks’s stories but develop some simple premise that allows Rosa to play with time and space in virtuoso fashion. These include “Cash Flow,” where the Beagle Boys buy an anti-friction ray-gun (Uncle Scrooge, Gladstone #224); “The Beagle Boys vs. the Money Bin,” (Uncle Scrooge, Gemstone #325), where the Beagle Boys find a map of the money bin; and my favorite, “A Matter of Some Gravity” (Walt Disney’s Comics, Gladstone, #610), where Magica de Spell buys a wand that turns gravity sideways for Scrooge and Donald.

In short, if Nolan ever saw “Dream of a Lifetime!” it could only have given him a few ideas out of the many that went into Inception.

DB coda:

For more discussion of the art of Christopher Nolan, see his category on the right-hand side of the page. We have an analysis of sound in The Prestige in the ninth edition of Film Art: An Introduction, and there we discuss the film’s narrative strategies as well.

Despite not caring for the movie, Jim Emerson has been assembling a wide-ranging and long-running dossier on Inception, with many comments. Scroll down the several entries here. Likewise visit David Cairns, who makes the necessary Anthony Mann comparison. The Wikipedia entry on the film is information-packed, and it includes several helpful links.

Our UW informants suggest that videogames having affinities with Inception include Assassin’s Creed II, Meigakure, and Shadow of Destiny. Thanks to Jason Mittell, Tim Palmer, Evan Davis, Leo Rubinkowski, Ethan de Seife, Edward Branigan, and Andrea Comisky for suggestions. See also Kirk Hamilton’s “Inception’s Usability Problem.”

On fourth-and fifth-level mindreading, see Robin Dunbar, The Human Story: A New History of Mankind’s Evolution (London: Faber, 2004), pp. 45-52. Dunbar’s study found evidence suggesting that women are better at tracking recursive mental states than men are.

Jan Simons offers an analytical survey of writing about New Artifice in an article here. For interpretations of particular films within the trend, see Allan Cameron, Modular Narratives in Contemporary Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) and Warren Buckland, ed., Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009). I try to lay out some narrative principles governing such films, including Memento, in The Way Hollywood Tells It and in the essays “Film Futures” and “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance” in Poetics of Cinema.

PS (17 December 2010): We have a rethink of Inception in this later entry.

[November 29, 2018: I have updated the section on Don Rosa’s “The Dream of a Lifetime!” by removing or updating dead links, correcting one error, and adding a few remarks on Rosa’s updated making-of essay on the comic. (KT)]

John Ford, silent man

John Ford on the set of Air Mail (1932).

DB here:

This is the busiest installment of Cinema Ritrovato I can recall. We scarcely have time to sleep, let alone blog. The coordinators Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée have outdone themselves in offering something for everybody, from early films to postwar French and Italian rarities up through a tribute to Stanley Donen and special screenings of The Leopard and Metropolis. Our attention has been riveted by the 1910 programs and an extensive collection of films directed by Alberto Capellani, a little-known master of silent film.

One headliner is the early Ford series: all his surviving silents, plus a selection of rarely-seen talkies. The first one screened, The Black Watch (1929), concentrates on intrigue in the Khyber Pass during World War I. Captain King is assigned to India while the rest of his Scots regiment is sent to Europe. In India, King masterminds the defeat of the forces of Yasmani, a woman who has been taken as sort of a goddess by her followers. The central section, involving Yasmani’s passion for King and his betrayal of her, seems to me sketchy and rushed; Ford’s real interest, not surprisingly, is in the rites of comradeship among the Black Watch. Twenty-two of the film’s 91 minutes are taken up with the opening dinner celebrating the regiment, conducted while King gets his assignment. Since his mission is secret, he abandons his comrades and suffers their opprobrium. A bookended sequence at the close shows him returning to the Watch as, in the trenches of war, they hold another dinner, complete with ruffles and flourishes.

Some of the central portion was directed by Lumsden Hare, but it too has some striking moments, perhaps most memorably the display of Yasmani’s powers when she conjures up an eerie vision of the European battlefield in a glowing crystal ball. The war sequences have the dank Expressionist look that Murnau brought to Fox and that Ford exploited in Four Sons (1928). There are as well touching train-station farewells between brothers and between father and daughter, all of which seem very Fordian. Overall, Ford finds ways to avoid the multiple-camera shooting common to early talkies, often using offscreen dialogue during reaction shots.

Also fairly free of multicamera work was The Brat (1931). Like many talkies derived from a creaky Broadway play, it entices us with a “cinematic” curtain-opener. Cops (including the young Ward Bond) hustle perps into night court, all captured in a flurry of high and low angles, bursts of deep space, and swift tracking shots. Afterwards things slow down, enlivened by some social satire (the pretentious novelist writes with a quill pen), a few sight gags (an artist’s muscled model who discovers he’s been rendered in a faux-Cubist image) and an all-in grappling fight between a society dame and a girl from the other side of the tracks. According to Ford, the fight got its impact from the fact that the actresses couldn’t stand each other.

The first silent Fords were introduced by Joe McBride. “When the real West ended,” Joe remarked, “the cinematic West began.” Born soon after the closing of the frontier, Ford was fascinated by cowboys and Native Americans. Early filmmakers were to a surprising extent celebrating the stoic Indians uprooted and forced to give up their way of life, and this resonated with Ford. The elegiac quality we find in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and other late films, Joe suggested, was already there in the genre. Ford’s own first Westerns, thanks partly to the presence of Harry Carey, carry an air of resignation to history. Even the fragmentary sequences surviving from The Secret Man (1917), in which Harry must sacrifice his freedom to save a little girl, have a severe melancholy.

Hell Bent (1920) has long been famed for its flashy, unrepeatable shot: A carriage pulled by horses tumbles into a ravine; the camera tilts down to follow the crash; and then the horses, freed at the top, come hurtling back into the frame to pass the wreckage. Otherwise the film is consistently agreeable, suffused with Fordian camaraderie among drunks and respect between hero and villain. This last element is starkly dramatized when Harry and his adversary, having wounded each other in a gun duel, must crawl through the desert together.

On my first viewing, I didn’t see in Hell Bent the inventiveness and grace notes I admire so much in Ford’s first feature, Straight Shooting (1917). As we’ve mentioned before, this film shows a mastery of the classical Hollywood style that emerged in the late 1910s. It bears comparison with William S. Hart films of the period, high points of filmmaking craft. Late in the plot Ford give us a shootout with ever-tighter framings that could have come out of Leone.

Whether Ford invented this particular piece of cinematic rhetoric we can’t say; too many silent films are lost. But coming from a 23-year-old filmmaker in his first feature, this remains a remarkably assured use of the continuity editing system for 1917.

Ford’s debt to Griffith has often been noted, and in this movie it turns up in unexpected ways. At one point Joan tenderly puts away the plate her dead brother had used, as if to preserve it. Later, Ford recalls the gesture when the cabin is under siege and bullets blow apart other plates on the sideboard. But Ford has already quietly suggested an association between brother Ted and Cheyenne Harry; as Joan kisses the plate before putting it away, Ford cuts to Harry outside, and then back to Joan slipping the plate into a drawer. Using the then-current technique of a “ruminative cut”, the editing suggests that Joan may also be thinking of Harry, and he of her. The idea of Harry replacing Ted is made explicit at the end when Sims plaintively asks Harry, “You be my son.”

The Griffith influence is particularly acute in Straight Shooting’s climax, when the farmers are under siege in the Sims cabin. Horsemen gallop around the cabin as hired gunmen pepper it with bullets. Meanwhile, Cheyenne Harry has persuaded Black-Eyed Pete’s gang of outlaws to rescue the settlers, and Ford gives us a rousing passage of rapid crosscutting. It’s a canonical last-minute rescue, straight out of the climax of The Birth of a Nation (191t5).

Or more particularly, I think, out of The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1914). Griffith commonly staged interior scenes with doors at the left and right of the frame, letting actors play laterally. The strategy can be considered somewhat theatrical, in that we never see the “fourth wall” that would in reality enclose the characters.

But this leads to problems when you want to show your characters surrounded. In Elderbush Gulch, the settlers are besieged by encircling Indians. At one point, Griffith cuts from the exterior of the cabin to the interior, and to convey the sense of enclosure he has one of the settlers firing “through” the fourth wall, as if over the heads of the audience!