Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Seed-beds of style

The Hunt for Red October.

DB here:

Seminar, orig. German (1889): A class that meets for systematic study under the direction of a teacher. From Latin seminarium, “seed-plot.”

I retired from full-time teaching in July of 2005. Since then, while writing and traveling (both chronicled on this website), I’ve done occasional lectures. But this fall I tried something else. At the invitation of Lea Jacobs here at Madison, I collaborated with her on a graduate seminar called Film Stylistics.

It was a good opportunity for me. I had a chance to learn from Lea, Ben Brewster, and the students and sitters-in. The class also enabled me to test and revise some ideas I’d already explored, while garnering new ideas and information. I helped plan the sessions and pick the films, but I had no responsibilities about grading. I hope, though, to read the students’ papers at some point after the term is over.

Our goal was to introduce students to studying style historically and conceptually. We focused on group styles rather than “authorial” ones because we wanted to explore particular concepts. How useful is the concept of group norms in understanding broad stylistic trends? Can we explain stylistic change through conceptions of progress toward some norm? Does the model of problem and solution help explain not only a particular innovation but also the group’s acceptance of it? How viable are notions of influence in explaining change? How much power should we assign to individual innovation? Can we think of filmmaking institutions as not only constraining style (through tradition and conformity) but also enabling certain possibilities—nudging filmmakers in certain directions? Does stylistic study favor a comparative method, one that encourages us to range across major and minor films, as well as different countries and periods?

These are pretty abstract questions, so we wanted some particular cases. Lea and I picked three areas of broad stylistic change: the emergence of widescreen cinema in the 1950s, the arrival of sync-sound filming in the late 1920s, and the development of analytical editing or “scene dissection” in the 1910s and 1920s. We tackled these areas in this order, violating chronology because we wanted to move from somewhat hard problems to the hardest of all: Why did filmmakers in the US, and soon in other countries, move toward what has become the lingua franca of film technique, continuity editing?

The results of our research on these matters will emerge over the next few years, I expect. In the short term, during my final lecture Tuesday I went off on what I hope wasn’t too much of a tangent. I got interested in one particular kind of cut, and it led me to see, once more, how different filmmaking traditions can make varying uses of apparently similar techniques.

More cutting remarks

My concern was the axial cut. That’s a cut that shifts the framing straight along the lens axis. Usually, the cut carries us “straight in” from a long shot to a closer view, but it can also cut “straight back” from a detail. What could be simpler? Yet such an almost primitive device harbors intriguing expressive possibilities.

Axial cuts aren’t all that common nowadays, I think. Today’s filmmakers prefer to change the angle when they cut to a closer or more distant setup. But such wasn’t the case in the cinema of the 1910s and 1920s.

In the heyday of tableau-based staging, 1908-1918 or so, filmmakers seldom cut into the scene at all. European directors especially tended to shape the development of the action by moving actors around the set, shifting them closer to the camera or farther away. The most common cuts were “inserts” of details, mostly printed matter (letters, telegrams) or a photograph. But when tableau scenes did cut into the players, the cuts tended to be axial: the framing moved straight in to enlarge a moment of performance. Here’s an instance from the 1916 Russian film Nelly Raintseva.

During the mid-1910s, American films moved away from the tableau style toward a more editing-driven technique. This approach often relied on more angled framing and a greater penetration of the playing space, of the kind we’re familiar with today. But axial cuts hung on in American films, even in quickly-cut scenes. Lea pointed out some nice examples in Wild and Woolly (1917), especially those involving movement. In the example below, the first cut carries us backward rather than forward, and the second is a cut-in, but both are along the lens axis.

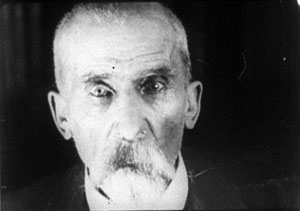

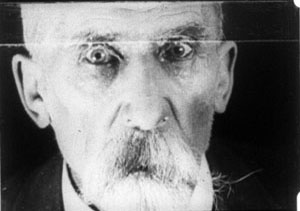

During the 1920s, axial cuts become a secondary tool of the American filmmaker, who now had many other camera setups available. But Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s, who adopted many American techniques in the name of modernizing their cinema, seemed to see fresh possibilities in the axial cut. For instance, in Dovzhenko’s Arsenal (1929), it becomes a percussive accent. The astonishment of a bureaucrat under siege is conveyed by a string of very fast enlargements.

The Soviets called such cuts “concentration cuts,” a good term for the way they make a figure seem to pop out at us. From being a simple enlargement (in tableau cinema) or one among many methods of penetrating the scene’s space (in Hollywood continuity), the axial cut has been given a new force, thanks to adding more shots and making them quite brief.

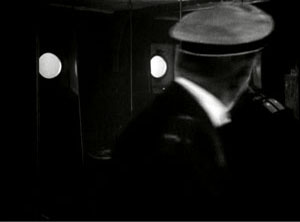

This aggressive method for seizing our eye—Notice this now!—has appeared in modern filmmaking too, as in this passage from Die Hard (1988).

Here the axial cut is clearly subjective, rendering John McClane’s realization that he can use the Christmas wrapping tape in his combat with the thieves. Director John McTiernan employed the device again in The Hunt for Red October (1990). The frames surmounting this entry show the heroes suddenly being fired upon.

It seems likely that many modern directors became aware of this device from seeing Lydia’s discovery of the pecked-up body of farmer Dan in The Birds (1963). Hitchcock knew Soviet montage techniques, so maybe we have a chain of influence here. In any case, the somewhat overbearing aggressiveness of the concentration cut has often been parodied on The Simpsons. Here’s a recent example.

By the law of the camera axis

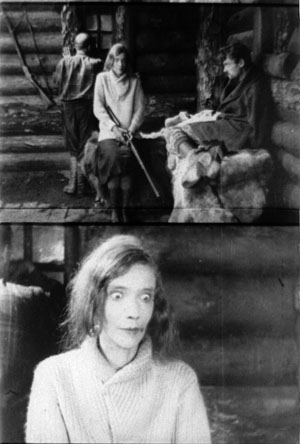

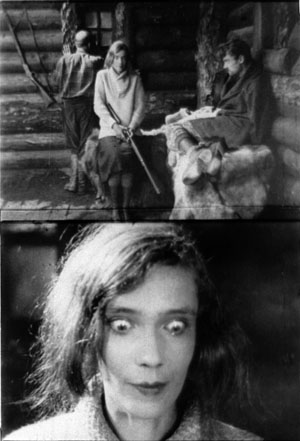

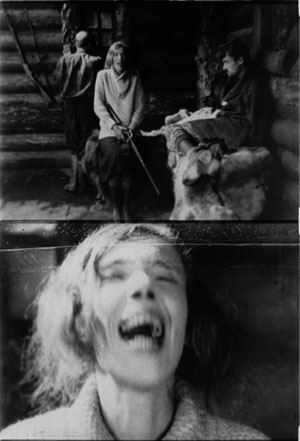

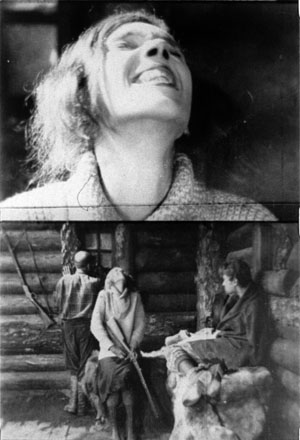

Axial cutting can be used more pervasively, as a structuring element for an entire scene. This is what Lev Kuleshov does in a climactic moment of By the Law (1926). Edith and her husband have kept the murderer at rifle point for days, and the strain is starting to show. She becomes hysterical, and Kuleshov uses a ragged rhythm of stasis and movement to convey it. First he cuts straight in from a master shot to a medium shot of her. I reproduce the frames from the film strip, for reasons that will become obvious.

Then Kuleshov cuts straight back to the master setup. Again he cuts in, but to a closer view of Edith as she becomes more frenzied.

Cut back once more to the long shot, but only for fourteen frames. That shot is interrupted by a shot of Edith already laughing crazily, her head tipped back.

The shot of her laugh lasts only five frames, and this mere glimpse, combined with the blatant mismatch of movement, makes the onset of her spell all the more startling. When we cut back to the long shot her face and position now match.

The abrupt quality of her outburst would not have been as striking if Kuleshov had varied his angle. As the earlier examples show, when only shot scale changes and angle remains the same, the cuts can be very harsh, and Kuleshov accentuates this quality with a flagrant mismatch.

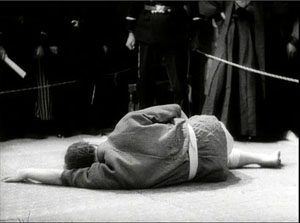

Akira Kurosawa likewise used the concentration cut to provide salient moments throughout his work; it almost became a stylistic fingerprint. At several points in Sugata Sanshiro (1943) he uses the device in the usual popping-forward way. But he varies it during Sanshiro’s combat with old Murai. He reserves dynamic, often elliptical cuts for moments of rapid action, and then he uses axial cuts for moments of stasis or highly repetitive maneuvers. In effect, the moments of peak action happen almost too quickly, while the moments of waiting are emphasized by cut-ins.

So at the start of the match, a series of axial cuts, linked by dissolves, present the fighters in a slow dance. But the ensuing throws are editing briskly. When old Murai is thrown and lies gasping on the mat, axial cuts accentuate his immobility. Kurosawa adds a rhythmic urgency on the soundtrack. After each cut-in, we hear the voice of Murai’s daughter, either offscreen or in his thoughts: “Father will win.” “Father will win.” “Father will surely win.”

The matching of lines to the editing is at work in the Simpsons parody too, in which the Comic Book Guy’s words are heard in tempo with the concentration cuts. “You. Are. Acceptable.”

Montage and the axial cut

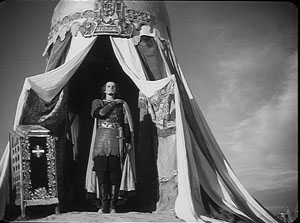

By now it’s easy for us to see that one scene from Alexander Nevsky (1938) opens with a series of axial cuts, out and in.

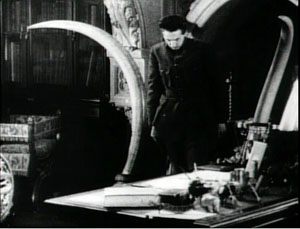

But why would Eisenstein, master of montage, regress to such a primitive device? He had occasionally used axial cuts in his silent films, as when we see Kerensky brooding in the Winter Palace in October (1928).

And Potemkin‘s famous cuts in to the Cossack slashing at the camera (that is, the baby, the old lady) are axial. (These cuts are pastiched by Eli Roth and Tarantino in Inglourious Basterds.) At the limit, Eisenstein toyed with the axial cut by moving the figures around during the shot change. In Potemkin, the ship’s officer reports to the captain that the crew has refused to eat. The captain leaves one shot and climbs the stair before Eisenstein cuts in to show him leaving again. The repetition would not be so perceptible if Eisenstein had varied the angle.

In the 1930s, Eisenstein began thinking about the axial cut as a basic structural element of a scene. In both his theory and practice, he promoted the axial cut to a level of prominence it hadn’t seen since the days of the tableau. Usually the cuts involve static subjects, like most of Kurosawa’s, but he still exploits the cut-ins to create vivid, if spatially impossible effects. At one point our popping in closer to Ivan the Terrible is doubled by him majestically and magically popping out of his tent to meet us, like a thrusting chess piece.

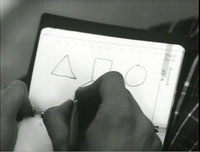

The new primacy of axial cutting comes from Eisenstein’s idea that “montage units” could powerfully organize the space of a scene. He thought that you could imagine filming a scene from only a few general positions, but then varying camera setups within each of these orientations. The montage unit was a cluster of framings taken from roughly the same orientation, as in the Pskov and Ivan scenes.

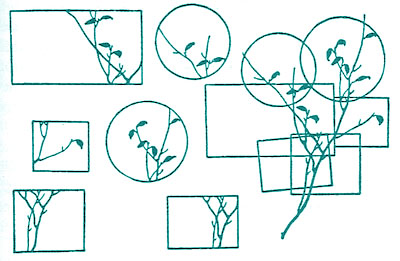

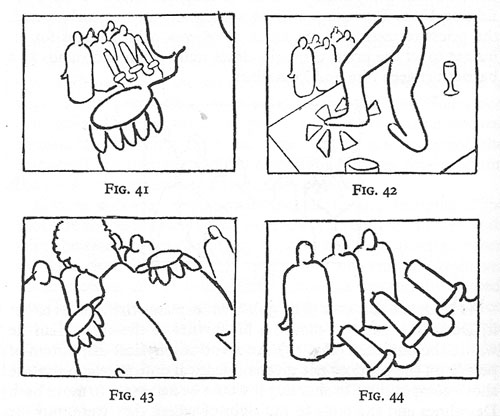

The idea may derive from his study of Japanese art, shown further above, in which he explored how a single image of a cherry branch could be chopped up into a great variety of compositions. In his course at the Soviet film school, he illustrated with a hypothetical scene of the Haitian revolutionary Dessalines holding his enemies at bay at a banquet. After imagining a master shot from the farthest-back position in the montage unit, Eisenstein proposes a series of dynamic closer views.

Eisenstein didn’t think that each scene had to be handled in a single montage unit. You could create two or three predominant orientations, with shots from each woven together. Or you could gain a sudden accent when a stream of setups from the same unit was interrupted by one from a very different angle. These ideas he put into practice throughout Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible.

Why? Eisenstein thought that combining shots taken from roughly the same orientation yielded a musical play between constant elements and variation. Each shot shows us something we’ve seen before but also something new, the way a bass line or sustained chords can continue underneath a changing melody. Eisenstein was convinced that this flowing weave of visual elements gave the spectator a deeper involvement in the film as it unfolded—an involvement akin to that found in Wagnerian opera.

The axial cut is a good example of how even a simple stylistic choice harbors rich creative possibilities. It also shows how a technique can change its impact in different filmmaking traditions. In the tableau tradition the axial cut was for the most part an abrupt enlargement heightening a moment of strong acting. In the early days of Hollywood continuity it became one editing option among many, and its power was somewhat muted. For the Soviets, concentration cuts could be multiplied and joined with fast cutting and big close-ups. The result could jolt the viewer by italicizing a face or an object–a purpose that has been taken up by contemporary Hollywood. For Kurosawa, the technique offered a way to contrast extreme movement and extreme stillness. And for Eisenstein, it suggested a global strategy for weaving visual elements into an immersive whole.

The protean functions assumed by this simple device remind us of how much there is yet to discover about film style. Despite all our discoveries over the last three decades, we have only begun. The name is apt: A seminar is where things start.

For more on the staging strategies of the tableau style, see On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, as well as blog entries here and here and here and here. You can find examples of emerging Hollywood continuity techniques in this entry on 1917 and this one on William S. Hart and this one on Doug Fairbanks. Sugata Sanshiro is at last available in a good DVD version from Criterion as part of its big Kurosawa box. Eisenstein’s ideas about the axial cut are explained in Vladimir Nizhny, Lessons with Eisenstein, trans. and ed. Ivor Montagu and Jay Leyda (New York: Hill and Wang, 1962), Chapters II and III. In The Cinema of Eisenstein I try to show how these ideas are employed in the Old Man’s late films.

Seated: Leslie Debauche, Lea Jacobs, Rebecca Genauer, Pam Reisel, Amanda McQueen. Standing: Karin Kolb, Andrea Comiskey, Ben Brewster, John Powers, Tristan Mentz, Heather Heckman, Aaron Granat, Jenny Oyallon-Koloski, Jonah Horwitz, and Booth Wilson. Evan Davis had to leave early.

Daisies in the crevices

DB here:

If you wanted a prototype of some unique visual pleasures of 1930s cinema, you could do worse than pick this innocuous image. It’s perfunctory in narrative terms, merely telling us that Sylvia Day is calling on Bill Smith. Beyond its plot function, though, it’s fun to see. We can enjoy the unfussy modern edge of the doorjamb, the curve of the manicured thumb, and soft highlights bringing out the hand and knuckles.

Above all, there is that starry gleam at the top of the doorbell. Who needs it? It’s just a doorbell. Why take so much trouble lighting a throwaway shot?

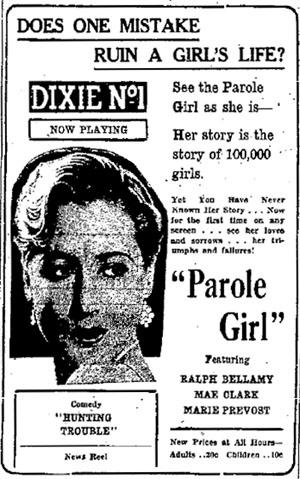

Add to this that Parole Girl (1933) is a program picture, and from Columbia, no less—the Poverty Row studio that had yet to break through with It Happened One Night (1934). We learn from Bernard F. Dick’s deeply-researched book on Harry Cohn that the budget for Parole Girl would have been about $250,000, when MGM B’s were running about $400,000. Why spend money on a shot like this?

Because that was the standard of good-looking moviemaking at the time. Most problems of converting to talkies had been solved, so films were regaining not only the fluent narration but the sparkling imagery of 1920s cinema. Under Cohn’s leadership, Columbia was trying to compete with the bigger studios’ movies, and looking classy was one way to do it. Recently I spent a day or so watching four titles, and I was reminded how pictorially sophisticated and refreshing low-end Hollywood can be. These movies also offer us an unusual window into what was already characteristic storytelling strategies of classical Hollywood. But there will be spoilers ahead too.

Welcome to 1933

As so often, I have TCM to thank. Since their Jean Arthur tribute of 2007, they have been running a generous number of Columbia titles (all restored by the master hand of Grover Crisp). By including less-known 1930s items along with classics like The Awful Truth and the Capra titles, they continue their mission of serving American film culture every hour.

Lea Jacobs has convinced me that it’s useful to think of studio releases in those days as filling a season running from Labor Day to Memorial Day rather than a calendar year. Studio heads planned budgets and production schedules according to that time frame, like network TV broadcasters now. Unlike today, summer was not a big release period, maybe because of the competition of other leisure activities, maybe because with air-conditioned movie houses people would come watch anything thrown on the screen. In any case, the big pictures were saved for fall, winter, and spring.

So my frame of reference is the 1932-33 season. Columbia ushered in the new year with its best-remembered film of the season, Capra’s Bitter Tea of General Yen (6 January). The studio probably considered Washington Merry-Go-Round (15 October), Virtue (25 October), and No More Orchids (15 November) to be A projects, but the large output of Westerns, the absence of historical pictures, and the relative dearth of stars in this output confirm the studio’s status as a Poverty Row company.

My movies come from the winter and spring of 1933. Each was shot in two to three weeks and each runs about seventy minutes.

Air Hostess (15 January, directed by Albert Rogell) tells of the daughter of a WWI ace who marries a reckless young pilot. Trying to build a new type of plane, he shops his business plans to a rich woman investor, who tries to seduce him.

In Child of Manhattan (4 February, directed by Edward Buzzell), a wealthy widower falls for a taxi dancer and takes her as his mistress. When she becomes pregnant, he marries her. But the baby dies soon after birth and the wife flees to Mexico for a divorce while the husband tries to track her down.

In Parole Girl (4 March, directed by Edward Cline), a department store executive sends a woman con artist to prison. She vows revenge. When she gets out, she seduces the executive, although he’s unaware of who she is.

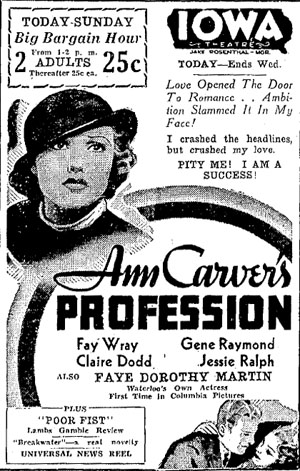

Ann Carver’s Profession (26 May 1933, directed by Buzzell) centers on a couple torn by career rivalry. After being a gridiron hero in college, the husband is failing as an architect. Meanwhile, his wife is becoming a celebrated trial lawyer. Eventually the husband leaves the household and takes up with a floozie, who winds up strangled. His wife must defend him against the murder charge.

For connoisseurs of naughty pre-Code movies, there are the usual attractions of double beds, extramarital sex, peekaboo negligees, and risqué dialogue. Child of Manhattan goes the farthest, perhaps because it’s an adaptation of a Preston Sturges play. “You’re a fascinating little witch,” says the millionaire. “Did you say witch?” the dancer asks. This is the same girl, played by perky Nancy Carroll, who thinks the man is trying to feel her up when he slips a thousand-dollar bill into her garter. Later she recalls her mother’s advice: “Never, ever walk upstairs in front of a gentleman.” And when she confesses to her Texan admirer in her mangled pronunciation, “I’m a courtesian,” he pauses and replies, “Well, religion doesn’t make any difference with me.”

Despite such pleasant moments, and two screenplays credited to Robert Riskin and Norman Krasna, these movies won’t win prizes for imaginative scripting. The tone is often uncertain, with comic banter clashing with scenes of melodramatic sacrifice. The long arm of coincidence becomes elastic. In Parole Girl, the heroine happens to meet the offending executive’s first wife in prison. During the taxi dancer’s stay in Mexico, she runs into the cowpoke who had wooed her aggressively in Manhattan. In Ann Carver’s Profession, the husband’s girlfriend accidentally strangles herself. Yes, you read that correctly.

Still, you have to give points for speed. Only Parole Girl has unusually quick cutting, at an average of 6.6 seconds per shot, but the overall pace of most of the plots is pretty rapid. (The exception is Child of Manhattan, whose lumbering dramatic rhythm is echoed in an average shot length of sixteen seconds.) Playing far-fetched action fast makes it less noticeable and more forgivable. Today any movie that can tell a moderately interesting story in a little more than an hour feels like a triumph. You can watch two of my pictures in the time it takes to groan your way through Funny People. And in these movies, the opening credits flash by in less than fifty seconds. Those were the days when crafts people under contract didn’t have to be acknowledged, and there were no executive producers.

Apart from Capra, whom do we remember as a Columbia director? Probably not my three guys. Albert Rogell, director of Air Hostess, began directing in the early 20s and worked for Columbia, Tiffany, Monogram, RKO, Universal, and Paramount. A prototypical B filmmaker, he signed over a hundred films in twenty-five years. Edward Buzzell was somewhat more prominent. After Ann Carver’s Profession, he left Columbia for Universal and eventually moved to MGM, where he directed (as if that were possible) the Marx Brothers in At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940), as well as helming Song of the Thin Man (1947). Like Rogell, Edward Cline (Parole Girl) skipped among studios; like Buzzell, he landed on his feet with comedian comedy, steering W. C. Fields through You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man (1939), My Little Chickadee (1940), and other vehicles. In all, studio artisans, yes; auteurs, no.

Two Joes and a Ted

Parole Girl

If you’re interested in how Hollywood tells its tales, there’s a fair amount to chew on in these modest releases. The scripts tend to obey Kristin’s four-part model, adapted to very short running times, with the key turning point taking place midway through the film. Despite the coincidences, the characters’ goals and changes of heart tend to be planted early. In Ann Carver’s Profession, Ann’s intense ambition and Bill’s swaggering overconfidence prepare us for the crisis in their marriage, when each is unwilling to compromise.

As for performances, perhaps the very speed of production forced actors to play naturally. True, Fay Wray is a bit arch as Ann Carver, but Gene Raymond as her husband moves convincingly from boisterousness to self-doubt. In Child of Manhattan, John Boles, trying to mingle with the little people, can be stiff, but Nancy Carroll has pep, and Buck Jones as her cowboy swain adds a welcome dose of naive gallantry. All three show how important distinct voices had already become: Boles mellifluous, Carroll up and down the scale, Jones slow and sincere. Reliable Columbia regular Ralph Bellamy shows up in Parole Girl, but more memorable is the performance, or rather presence, of Mae Clark. When she comes back from prison bent on vengeance, she’s a glowering figure in her stylishly chopped hairdo.

As for performances, perhaps the very speed of production forced actors to play naturally. True, Fay Wray is a bit arch as Ann Carver, but Gene Raymond as her husband moves convincingly from boisterousness to self-doubt. In Child of Manhattan, John Boles, trying to mingle with the little people, can be stiff, but Nancy Carroll has pep, and Buck Jones as her cowboy swain adds a welcome dose of naive gallantry. All three show how important distinct voices had already become: Boles mellifluous, Carroll up and down the scale, Jones slow and sincere. Reliable Columbia regular Ralph Bellamy shows up in Parole Girl, but more memorable is the performance, or rather presence, of Mae Clark. When she comes back from prison bent on vengeance, she’s a glowering figure in her stylishly chopped hairdo.

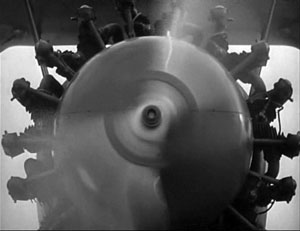

The films make fluent use of storytelling devices that predate the 1930s but are forever associated with that decade. Sequences are linked through headline montages and wipes, recently made possible by the optical printer. There are more elaborate techniques too, particular the visual or auditory hook connecting scenes. We’re not surprised to see commonplace instances, as when a note pad listing an apartment number dissolves to that number on the door. In Air Hostess, however, a spinning propeller gives way to a roulette wheel, and this association does a little more work, linking Ted Hunter’s reckless flying to his gambling and his general tendency to take risks.

In Child of Manhattan, as Madeleine resolves to leave her husband after the death of her child, she tearfully shakes a baby rattle, and this dissolves to marimbas in a nightclub, swiftly turning her pathos into her effort to start a new life with a Mexican divorce.

But what is perhaps most striking about these films is their photography. Ten minutes into Air Hostess, the first one I watched, we get a lovely sustained track into a sunny airfield, our view guided by the walkway wheeled up to a plane door as passengers step out.

The relaxed play of light and shadow in this geometrical shot yields one of those fugitive visual delights that classic cinema so often supplies.

What’s it doing in a Columbia programmer? This Poverty Row studio realized that they could give their pinched budgets an upscale look with polished cinematography. Accordingly, you can argue that the biggest talents on the Columbia lot were the directors of photography. Our four films were shot by ace DP’s.

Joe August (Parole Girl) was the grand old man. He filmed some of the best-looking hits of the 1910s, including Ince’s Civilization (1916) and a great many William S. Hart movies (including Hell’s Hinges, 1916). In the 1920s and up to 1932 he worked at Fox on films by Ford, Hawks, and Milestone. At Columbia August would shoot Borzage projects like Man’s Castle (1933) before moving to RKO for Sylvia Scarlett (1936), Dance, Girl, Dance (1940), and the flamboyant All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil and Daniel Webster, 1940).

Another Joe, somewhat younger, was no less gifted. Joseph Walker, the DP of Air Hostess came to Columbia early and soon teamed with Capra; he would shoot twenty movies with the director, including the splendid American Madness (1932), a particular favorite of mine. Walker stayed loyal to Columbia, shooting Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), Penny Serenade (1941), and on and on—returning to Capra for the independent production It’s a Wonderful Life (1947). Walker also patented an original zoom-lens design.

Ted, sometimes known as Teddy, Tetzlaff was another Columbia loyalist, and he certainly cranked them out. Hawks’ The Criminal Code was one of eleven movies Tetzlaff was credited with in calendar 1931. But by the spring of 1933 he seems already to have become a free lance, eventually working at Paramount on a string of classics (Easy Living, Remember the Night, Road to Zanzibar), then RKO (The Enchanted Cottage, Notorious), and occasional jobs back at Columbia. Tetzlaff became a director as well, remembered chiefly for the cult classic The Window (1949).

No wonder my four films dazzle, even on TV. According to Bob Thomas’s biography King Cohn, Columbia took special care to create a phosphorescent look through careful processing that enhanced the DPs’ efforts. Hence not only the sparkle on a door buzzer but glowing applications of then-standard edge lighting. Hence as well the use of striped shadows to suggest venetian blinds, a convention we associate with the forties but here in precise array (Child of Manhattan, Parole Girl).

Trust Joe Walker to provide a little of that striped texture with a fuselage.

Hence too some striking depth. Here is the next-to-last shot of Walker’s work in Air Hostess, the sort of fancy aperture composition that crops up surprisingly often in the 1930s.

Tetzlaff, first in Child of Manhattan and then Ann Carver’s Profession, seems to be fooling around with faces and elbows.

Probably the most visually and narratively complex of my films from spring 1933 is Ann Carver’s Profession. It’s possible that it was Columbia’s equivalent of an A production: Gene Raymond was a mid-range star known for a few Paramount and MGM pictures, and Fay Wray’s King Kong had premiered a week before filming started. Whatever the cause, Ann Carver has more complex plotting and more consistently inventive visuals than the three other titles.

From the very start, when gridiron hero Bill promises to provide for Ann the waitress, we get the sort of offhand flash that I like in 1930s movies. As Bill follows Ann into the kitchen, she’s framed in a swinging door and the camera moves closer to pick up their clinch.

Once they’re married, the circle has become a rectangle, and trouble is on the way.

There are fancy mirror shots, pov constructions that lead characters to the wrong inferences, and examples of the big-foreground compositions that would come to prominence in the 1940s.

The trial recesses; crane up to the clock; spin the hands to cover a couple of hours; crane back to the trial resuming. Or start with Bill’s girlfriend, passed out and garroted by the necklace that has snagged on a leering chair carving. Dissolve to Bill’s night on the town, before ending that fuzzy montage with a dissolve back to the chair carving.

Bill didn’t kill her, but the pictorial logic makes him almost magically responsible, with the carving mocking him for what’s to come.

Above all there is one of the most laconic (and cheaply filmed) courtroom montages I’ve ever seen. A string of witnesses testifies, and after a newspaper pops out the first one, we get a fusillade of extreme close-ups, cut very quickly.

Just as striking is the coordinated sound montage, which reduces the testimony to clipped sentences, then phrases (“”Four-thirty!” “Quarter to five!” “Both of ‘em!”), then single words (“Drunk!” “Drunk!” “Strangulation!”), all damning Bill. Why take us through all the rigamarole—people sworn in and questioned at length—when you can give the essence of it in twenty-eight shots and twenty-five seconds?

My 1933 quartet contains no great film; perhaps none is worth more than one viewing. But what I learned from watching ordinary movies for our Classical Hollywood Cinema book is borne out by my soundings here. We can enjoy seeing a well-honed system steering us through a story, especially when gifted people like Teddy and the two Joes are shifting the gears. We can appreciate the opportunities for grace notes in what some call formula filmmaking. And we can see that this lowly studio, making films ignored in traditional histories, has something to teach filmmakers today: proud modesty. A film can radiate pride in being concise, in exercising a craft, and in telling a story that hurtles forward while shedding moments of casual beauty.

Most critical writing on early 1930s Columbia pictures focuses on Frank Capra, but there is good general background in Bernard F. Dick, The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row: Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009). My mention of budget levels comes from his discussion on pp. 119-120. An older, citation-free but still helpful biography is Bob Thomas, King Cohn (Beverly Hills: New Millennium, 2000). In-depth information on Joseph Walker as a Columbia cinematographer is available in Joseph McBride’s excellent biography Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 189-215. Walker’s engaging autobiography supplies nothing specific to these films, but he sprinkles technical information among its anecdotes. See Joseph Walker and Juanita Walker, The Light on Her Face (Los Angeles: ASC Press, 1984).

On 1934 as the end of naughtiness, see Tom Doherty’s Pre-Code Hollywood. For a skeptical account of the idea of Hollywood “before the Code,” see Richard Maltby, “More Sinned Against than Sinning [2003],” in Senses of Cinema here, and essays in “Rethinking the Production Code,” a special issue of The Quarterly Review of Film and Video 15, 4 (1995), ed. Lea Jacobs and Richard Maltby.

If you’re interested in more complicated narrative strategies in films of this period, try our entry “Grandmaster Flashback.” For another take on low-budget 1930s films, there’s our entry on Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan.

Class of 1960

DB here:

By now most people accept the idea that 1939 was a kind of Golden Year of cinema. You know, Rules of the Game, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, that movie about the Civil War, etc. TCM has even made a movie about 1939. On this site Kristin and I have talked about earlier wonder years, like 1913 and 1917. So in planning this year’s Bruges week-long Zomerfilmcollege (aka Cinephile Summer Camp), Stef Franck and I discussed building my lectures around a single year. I proposed 1941, but he countered with 1960.

1960 was a logical choice in providing spread for the whole program. At Bruges we intertwine several threads of lectures and screenings, and this year we had silent films (The Cat and the Canary, The Wind), Hollywood’s cinema of emigration (Florey, Siodmak, Ophuls, etc.), and contemporary Korean film. All in 35mm, of course. So picking 1960 filled in another area.

As so often happens, a contingent choice came to seem a necessary one. By the time I opened my mouth to introduce The Bad Sleep Well, I had convinced myself that 1960 was another watershed year. Consider these releases:

Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti), La Dolce Vita (Fellini), L’Avventura (Antonioni), Le Testament d’Orphée (Cocteau), Plein Soleil (Clement), À bout de souffle (Godard), Les Bonnes femmes (Chabrol), La Verité (Clouzot), The Bridge (Wicki), Wild Strawberries (Bergman), The Devil’s Eye (Bergman), Lady with the Little Dog (Heifetz), The Letter that Wasn’t Sent (Kalatozov), The Steamroller and the Violin (Tarkovsky short), The Teutonic Knights (Alexander Ford), Innocent Sorcerors (Wajda), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Reisz), Tunes of Glory (Neame), Sergeant Rutledge (John Ford), Psycho (Hitchcock), Spartacus (Kubrick), Elmer Gantry (Brooks), 101 Dalmatians (Disney/ Reitherman), The Magnificent Seven (Sturges), Exodus (Preminger), Home from the Hill (Minnelli), Comanche Station (Boetticher), Verboten! (Fuller), The Bellboy (Lewis), The Young One (Buñuel), TheYoung Ones (Alcoriza), The Shadow of the Caudillo (Bracho), Devi (Ray), The Cloud-Capped Star (Ghatak), This Country Where the Ganges Flows (Karmakar), Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin), The Back Door (Li Han-hsiang), Enchanting Shadow (Li Han-hsiang), The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin), Desperado Outpost (Okamoto), Spring Dreams (Kinoshita), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Naruse), Daughter, Wives, and Mother (Naruse), Cruel Story of Youth (Oshima), The Sun’s Burial (Oshima), Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima), The Island (Shindo), Pigs and Battleships (Imamura), Sleep of the Beast (Suzuki), and Fighting Delinquents (Suzuki).

We didn’t show any of them.

Several factors constrained our choices, including the availability of good prints with Dutch subtitles, or at least English ones. We also didn’t want to run too many official classics. And we fudged a little for pedagogy’s sake. We had to include a Godard, but instead of À bout de souffle, we picked Le Petit soldat—made in 1960 but not released until 1963. The World of Apu was released in 1959 in India, though it made its world impact in the following year. Lola was finished in 1960 but released in early 1961. A dodge, but I wanted a Nouvelle Vague counterpoint to Godard, and it fit well with the Ophuls thread, and—well, it’s Demy. In any case, we wound up with a list of outstanding movies.

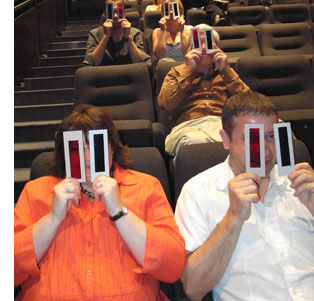

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

All in all, quite a week. My sessions ran from 9:00 AM to 12:30 or 1:00 PM, with the film embedded. After lunch, there were more talks and screenings, usually winding up at about 1:00 AM. Other speakers included Kevin Brownlow, Tom Paulus, Steven Jacobs, Muriel Andrin, Egbert Barten, and Christophe Verbiest (linking his talks on contemporary Korean film to the absolutely nuts 1960 Kim Ki-yong melodrama The Maid). The locals’ lectures were in Dutch, but these worthies are fluent in English, so sharing meals with them allowed me to catch up with their ideas.

Pegging a batch of movies to a single year can seem gimmicky, so I treated the films as exemplifying different trends, many of which started before 1960 and have continued since. I concentrated on trends within world film culture, though in several cases those were tied to still broader social and political developments. Above all, the 1960 frame allowed me to do the sort of comparative work I enjoy.

Generations

My first grouping was “Twilight of the Masters.” This allowed me to develop the idea that, remarkably, people who had started making films in the 1910s and 1920s were still active in the 1960s—and often making films that recalled their youthful efforts. Renoir revisited La Grande illusion in The Elusive Corporal, and Dreyer returned to his origins in tableau cinema through the staging of Gertrud.

In this connection, Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, his final movie, revisits his Mabuse cycle in the way his previous films for Artur Brauner revise the “sensation-films” he wrote for Joe May (especially The Indian Tomb). Drawing on some ideas in my online essay, “The Hook,” we studied Lang’s crisp transitions between scenes. From this angle, 1000 Eyes is a sort of encyclopedia of ways you can connect scenes (visual link, auditory link, association of ideas, etc.). The transitions whip up a breathless pace and steer past some plot holes, and sometimes they generate a level of mistrust, implying story possibilities that don’t turn out to be valid.

Testament’s motif of eyes and vision became expanded to television surveillance in 1000 Eyes. There might even be an oblique connection between the Hotel Luxor’s panopticon and the rise of television ownership in Europe at the period. Here, as ever, cinema doesn’t have good things to say about TV.

Twilight of another, not quite so old master: Late Autumn by Ozu. I reviewed some features of Ozu’s style and then analyzed the film as a multiple-character drama. Ozu and his collaborator Noda Kogo split up the plot in order to present different characters’ attitudes to the central situation: the question of a daughter’s marriage. The plot ingeniously withholds information about the attitude of Akiko, the mother, by deleting certain scenes that would clarify it. Here too, the old master recalls earlier films by having characters discuss their college flirtations, which invoke scenes from Days of Youth and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?

Both Billy Wilder and Akira Kurosawa furnished me with a second generational cohort. I know, probably nobody in his right mind would see common features between these two directors. But desperation can fuel audacity. Both emerged during the late 1930s, began directing in the 1940s, and enjoyed a string of great successes in the 1950s; but both fell on harder times in the 1960s. Both became accusatory living legends, haunting local industries that had kept them from working.

Leading up to The Apartment, I considered Wilder’s contribution to two trends. First, the industry had hit the doldrums. In Europe television and new leisure lifestyles were not yet the threat they would become, but in America, the industry needed to pull its audience away from the TV set and the barbecue. Wilder proved skilful in using Hollywood’s turn to sex as the basis for his cynical comedies. The Lubitsch touch, a worldly appreciation of the oblique approach to matters of sex, was replaced by something harsher. In Wilder’s world, there are mostly sharks and shnooks, those who take and those who are taken.

Second, I situated Wilder as a leading figure in the emergence of the writer-turned-director in the 1940s (Sturges, Huston, Brooks, Fuller, Mankiewicz, etc.). This encouraged me to probe his dramaturgy, and so we analyzed the taut structure of The Apartment’s plot. It has rightly been recognized as a model screenplay, making us sympathize with a careerist covering up his bosses’ infidelities, all the while whetting our interest by shifting the range of knowledge away from the protagonist at key moments. It also displays a nice interweaving of motifs that function both dramatically and metaphorically (especially Miss Kubelik’s hand mirror). Of course at the end I had to run a clip showing the influence of The Apartment on the opening of Jerry Maguire.

By the mid-1960s, however, Wilder was pushing his luck, especially with Kiss Me Stupid. In The Apartment he wanted to make “a movie about fucking,” and he predicted that some day people would do the deed onscreen. But having glimpsed the promised land of the 1970s, he was unable to enter. Despite some worthy efforts, notably The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, he haunted Hollywood as a major director who had outlived his moment.

Human, all too human

Kurosawa’s international fame came largely through the growth of the film festival as a prime institution of international movie culture. This situation let me sketch in the importance of festivals in bringing directors like him to world recognition. (By the way, Richard Porton has just brought out an informative collection of thoughts on film festivals.) With The Bad Sleep Well, I was able to talk a bit about something that is often forgotten—Kurosawa’s efforts in social, even political cinema. From Sugata Sanshiro, a tribute to Japanese martial arts, and The Most Beautiful, the loveliest movie you’ll ever see about girls making lenses for gunsights, up through Occupation projects like No Regrets for Our Youth and Scandal, Kurosawa engaged with political subject matter. Ikiru and I Live in Fear made this side of his work even more salient in the 1950s.

The Bad Sleep Well’s attack on corporate corruption sits well with this tendency. It considers the “iron triangle” of Japanese politics, the collusion of bureaucrats, politicians, and private industry—particularly the building industry, whose livelihood depends on bids for government projects. Still, it’s hard to believe that while Kurosawa made the film, and while Ozu made the serene Late Autumn, students were fighting police in the streets over the US-Japan security treaty. That turmoil surfaced in Oshima Nagisa’s demanding and formally daring Night and Fog in Japan.

The movie is shot with Kurosawa’s usual muscularity, including virtuoso compositions in what he called, following Toland, “pan-focus.”

The film’s twists also seemed to me worth examining. The protagonist is a minor presence in the first scenes, and his reticence in the beginning is mirrored in the finale, when he simply vanishes and his pal has to tell us what happened to him. Such a daring structure, reminiscent of the abrupt midway break in Ikiru, gives the film an almost Brechtian discomfiture, as well as highlighting the secondary characters’ rather perverse reaction to the hero’s fate.

Kurosawa was widely called a “humanist” director, and this concept sheds light on what we might call the “international film ideology” pervading festivals in the 1950s. In various areas of social and philosophical thought, a notion of humanism emerged out of disillusionment with the “age of ideology” that had engulfed the world in war. Several thinkers declared that the age of religious dogma and social collectivism, either Nazi or Communist, was over. Now what mattered were the features that drew people of all societies together, and the prospect of enlightened social action based on those commonalities—tolerance, respect, and a belief that people ultimately took individual responsibility for their communities. Catholics, Communists, and people of all stripes scrambled to call themselves humanists. As Dwight Macdonald, former Trotskyite, put it, “The root is man.”

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

Film festivals embraced this universalism, pointing to the great films of Italy’s Neorealist trend as proof of cross-cultural communication. Although these films often scored specifically Italian political points, they could also be seen as human documents speaking to audiences anywhere. Who could not empathize with Ricci and his son in Bicycle Thieves (named at the 1958 Expo as the third-greatest film ever made)?

The turn to humanism helps answer a puzzling question: Why Satyajit Ray? Virtually no Europeans had ever seen a film from India. What enabled a director from this country to achieve worldwide renown? And why not other Indian directors of his era, such as Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak? All of these had to wait many years for discovery by European tastemakers.

For one thing, Ray was highly westernized himself. He was a child of the Bengali Renaissance, a virtuoso in many fields (he composed music, drew with facility, wrote detective stories and children’s books), and an admirer of European cinema. A stint assisting Jean Renoir exposed him to one of the greatest of Western filmmakers. A viewing of The Bicycle Thieves determined him to make films. He was skeptical of imitating Hollywood, which had been a prime inspiration for Hindu cinema. He criticized Bollywood’s reliance on schematic romance and musical numbers. If any Indian director was to make the move to the festival circuit, it would be him. (You can argue that other non-European filmmakers who made it into the fold were the most “western”—Kurosawa, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, etc.).

Just as important, Ray’s stories suited the humanist program. Whereas Ghatak and Sen made politically charged films, Ray concentrated on the individual. In The World of Apu, social conditions are shown, but as a background to the development of personality and psychological tensions. At the film’s start, students are holding a street march demanding political rights, but they are offscreen, a backdrop to Apu’s meeting with his old professor as he gets his letter of recommendation. What follows is a drama of artistic failure, blossoming love, and a young man’s confused growth to maturity and responsibility.

It’s a simple story, rendered lyrical through constantly developing imagery: Apu stretched out prone, the famous grimy window curtain, and a cluster of visual motifs I hadn’t noticed on previous viewing. Ray’s concise direction links the torn curtain in Apu’s room to the famous (Langian?) transition from a movie screen to a carriage window, the cluster unified by associating Apurna with male children. Thanks to Andrew Robinson’s book on Ray, we know that in the carriage scene she is already thinking of the son she will bear.

It’s easy to romanticize this handsome, happy-go-lucky hero. I think the College participants thought I was a little hard on Apu, since I treated him as far from the “conscientious and diligent” young man his professor wrote of. Surely his idealistic-novelist persona is sympathetic. But if he is to grow as the film suggests, he must have failings, and Ray shows them to us—dreamy indolence, self-centeredness, even poutiness. The film is a character study, a sort of Bildungsroman tracing how Apu learns his place in his world. Our discussion after this film was particularly rich, with one participant suggesting that in accepting his son he isn’t abandoning his art entirely, but giving it human significance: He promises to tell Kajal stories.

Ray came to directing in middle age, a somewhat rare option. So too did Gillo Pontecorvo, but the latter made many fewer films. Although Kapò, isn’t as strong a movie as our other entries, it did allow us to talk a bit about coproduction, about European cinema’s relation to World War II, and about what came to be known as the morality of technique.

European coproductions are another fundamental part of the 1960 landscape, and they illustrate how economic considerations penetrate artistic choices. (Why are American and Italian actors in the “German” film 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse? Why do we find Anouk Aimée in 8 ½ and Jeanne Moreau in La Notte? Follow the money.) For the Italian production Kapò, the primary roles are taken by an American (Susan Strasberg, playing the heroine Edith) and two French actors—the concentration camp translator played by Emmanuelle Riva and the heroic Soviet soldier played by Laurent Terzieff. The film was shot in Yugoslavia.

The story centers on a young Jewish girl who, in order to survive Nazi internment, passes herself off as a Gentile and becomes a camp commandant, whipping other prisoners into line. Other Italian films of the period, notably Rossellini’s Generale Della Rovere, were dealing with issues of conscience during the war, but Kapò was apparently the first fictional feature in Western Europe to confront the Holocaust since Alessandrini’s Wandering Jew of 1947. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossod and stood trial the following year, and after Kapò came a few other films addressing the camps, notably Wajda’s Samson (1961) and Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965). So the film had a strong contemporary resonance; after its US release, it would be nominated for an Oscar.

One reason Stef and I picked Kapò was the controversy around Jacques Rivette’s accusation in Cahiers du cinéma that for a particular tracking shot Pontecorvo deserved “the most profound contempt.” The film, as Rivette indicates, is dominated by an already compromised conception of realism: grimed faces, make-up that hollows cheeks, somewhat ragged clothes, moderately shabby bunks. The shot shows the body of Theresa hurled against the electrified barbed wire, with the camera coasting slowly toward it. Her silhouette is almost classically composed, with the hands artfully pivoted and standing out against the sky. For Rivette this pictorial conceit is virtually obscene.

It seems to me that Rivette’s essay sought in part to reply to those who thought that Cahiers’ policy amounted to pure formalism. In calling for an ethics of technique, Rivette argues that artistic choices which might seem to be in the service of correct politics can betray a deeper immorality: using a historical cataclysm as an occasion for a safe realism and self-congratulatory flourishes. Similar complaints could be lodged against Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg and Stone’s World Trade Center. And because for the Cahiers team artistic cinema was an expression of a creator’s vision, the morally maladroit traveling shot brands the director as a man of bad faith.

Rivette isn’t saying that film artists shouldn’t try to represent historical trauma. He simply argues that other paths could be taken. For instance, Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour acknowledge that some events cannot be encompassed by normal understanding, and the form of each film enacts an effort to understand, not a fixed conclusion. What we see in Night and Fog is “a lucid consciousness, somewhat impersonal, that is unable to accept or understand or admit this phenomenon.” For Rivette, Pontecorvo seems convinced that romantic love and self-sacrifice can overcome Nazism, albeit with some help from the Red Army. He tries to explain, even prettify, an event that cannot be understood within the usual humanistic categories.

New Wave, still new

Lola.

Godard’s Le Petit soldat is far more preoccupied with uncertainties, even confusions, than Kapò is. 1960 saw an extraordinary number of former colonies, especially in Africa, gain independence, and during that year the Algerian war of resistance was spreading to Europe. Godard’s central character Bruno is working with the OAS vigilantes dedicated to killing Algerian terrorists, but when he meets the lovely Veronica Dreyer he decides to leave politics behind and flee with her to Brazil. Perhaps “decides” is the wrong word, since his actions are impulsive: he abruptly shies away from committing a political assassination, and he abruptly abandons his colleagues. But he’s captured by FLN terrorists and, in the film’s most famous sequences, tortured. At the end, he commits the assassination, not knowing that Veronica, herself in league with the Algerians, has been captured by his pals and killed. But his final voice-over is almost a shrug, and his act of murder takes on the flavor of an existentialist acte gratuite.

Le Petit soldat doesn’t offer heroic figures, as Kapò does in Theresa and the Soviet soldier. Nor does it allow us to sympathize much with the egotistical, capricious Bruno. The texture is more disjunctive, littered with the usual digressions and citations. Since the film was shot in Geneva, there’s a persistent motif of Swissness, with citations of Paul Klee. A sneaky one I never noticed before: the seduction game Bruno plays is modeled on the three fundamental shapes in the Bauhaus basic course, which Klee taught.

Having experimented with discontinuous imagery in À bout de souffle, Godard in his second feature turns his attention to the soundtrack, creating one of the most minimalist ones I know. If Bresson whittles down his soundtrack to a spare but recognizable realism, Le Petit soldat goes a step further, scrubbing out nearly every noise until we’re almost watching a silent film. Traffic scenes lack traffic noises, with only a car horn or a bit of dialogue breaking in. One passage on a train could almost be a sound loop.

The strategy of suppressed sound is carried to a paroxysm in the torture scenes, with the clink of handcuffs and the soft tapping of typewriter keys highlighted and bits of music played spasmodically…but no sounds of pain. Only during the rushed and almost throwaway climax, is something like a plausible city ambience heard. In a dichotomy that will be familiar throughout Godard’s work, there’s a split between image (Bruno is a photographer, and in the early part of the film he takes snapshots of Veronica in her apartment) and sound (the political factions rely on telephones and tape recorders, and the OAS thugs trick their way into Veronica’s apartment through sound recording).

In all, Le Petit soldat isn’t exactly fun but it’s exhilarating in its bursts and unexpected frictions. Next time somebody tells me that Godard’s technical innovations have all become commonplace, I’ll point to this film of 1960, which would be daring and demanding if released tomorrow.

Fun, albeit grave, is what Lola is all about. It takes formal artifice far beyond realism, creating a sort of non-musical musical. (It has one number, and even that is a sketchy rehearsal.) As geometrical as a minuet, its plot plays out in a hall of mirrors, where characters share names, pasts, and sentiments. The sailor Frankie and the wandering Michel, both in love with Lola, are blonde giants. Lola is actually named Cécile, and the little girl of the same name seems in some ways an early version of her, while Cécile’s mother has a dash of Lola in her past.

Roland starts out as the protagonist, but as he warms and cools and warms to Lola, the story momentum shifts to others. There’s Lola of course, and young Cécile who strikes up a friendship with Frankie, and Cécile’s mother who yearns a bit for Roland, and Michel, who left Nantes years ago and has lived in another movie, specifically, Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1952). Here the structure of the plot unfolds the network of relationships among people, linked mostly by casual encounters across a few days. The last section accordingly consists of a series of farewells, as if the story can end only by breaking ties of affection.

In surveying these films, I was struck by how much most of them owed to the growth of postwar institutions of film culture, and how strong those institutions remain. Coproductions and subsidies were feeding a massive buildup of European cinema. Contrary to what you might expect, as attendance cratered from the late 1950s onward, the number of European films produced went up. The EU countries still overproduce, releasing nearly 1200 theatrical features in 2008.

Film festivals were promoting not only universal humanism; they were also packaging films under rubrics of authorship or the New XXX Cinema and the Young ZZZ Cinema. 1940s Neorealism, aka “New Realism in Italian Cinema,” seems to have been, once more, the prototype. Festivals must make discoveries and emphasize novelties. At the same period film schools taught professional standards, and film archives showed classics and gave postwar filmmakers a more secure sense of the medium’s history. Lang, Ozu, and Wilder weren’t dependent on such institutions, but younger filmmakers were. And still are.

1960 is an arbitrary data point, but it stands out as an extraordinary year for quality. In addition, picking it as a benchmark allowed me to think about some important trends of the period. What probably didn’t show through my lumbering PowerPoints, with their charts, diagrams, and frame enlargements, was how much I learned from my Bruges stay. One of the deep satisfactions of teaching is remembering, no matter how confidently you declare your claims, how much more there is to know. Of things cinematic there is no end.

We also asked participants to read Serge Daney’s essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò.” Daney’s elaborate exercise in autobiography, irony, and moral reflection could not be plumbed in the time at my disposal, there or here. But it did help me understand Rivette’s argument. In preparing my lectures, I also owed a debt to some excellent books, notably Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity; Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye; Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism; and Richard Brody, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As ever, the invaluable documentation provided by the print editions of Screen Digest over the years enabled me to compile my tables of attendance, releases, and the like.

Late Autumn.

P.S. 3 Aug: Stef has posted snapshots from our Zomerfilmcollege here.

P.P.S. 3 Aug: This helpful correction from Roland-François Lack on Le Petit Soldat:

One small point: the organisation Bruno works for cannot be the O.A.S., which wasn’t active until the end of 1960.

He is working, rather, for ‘La main rouge’, a government sponsored counter-terrorist agency run by a Colonel Mercier (hence the name of Bruno’s associate).

Nice! Thanks.

The Bologna beat goes on

Guy Borlée, Festival Coordinator for Cinema Ritrovato, in a pas de deux with Moira Shearer.

DB here:

Like most film festivals, Cinema Ritrovato is many festivals. There’s so much on offer you can carve out your own mini-fests. You may meet a friend for lunch and learn that you two have seen none of the same movies. So here are some titles from my sampled version of Ritrovato.

1909 and a little later

Le Trust (Feuillade, 1911).

As Kristin pointed out in our last entry, we spent a lot of time in the 100 Years Ago thread. Things were definitely changing on screens in 1909. True, you still had your costume picture with suspiciously insubstantial walls and props, your gimmicky special-effects comedies (e.g., The Electric Policeman), and your chase films with people falling over and getting up and running on, endlessly.

But you also had powerful movies like Capellani’s L’Assommoir, discussed by Kristin, and charming ones like Charles Kent’s Vitagraph Midsummer Night’s Dream. There were crime films like Tell Tale Blotter and An Attempt to Smash a Bank, with its peculiar slow reverse tracking shots linking the lobby and the banker’s office. There was Cowboy Millionaire, which presents the always-edifying spectacle of a buckaroo bringing his uncouth pals to the big city. There were wonderful Film d’Art items, not least Le Retour d’Ulysse, which had the most rapid editing pace of any 1909 film I clocked. There was even a lifelong romance told through the fate of two pairs of shoes (Roman d’une bottine et d’un escarpin).

Louis Feuillade was one of the finest directors of the 1910s, but most of his earlier work that I’ve seen doesn’t suggest his mature storytelling skills. Of the 1909 Feuillades on display in Bologna, the two I found most intriguing were La Possession de l’enfant, about a divorced wife who kidnaps and raises her child in poverty, and La Bouée, a touching tale about a fisherman’s family about to lose everything. But the cherry on the sundae for me was a pristine print of a 1911 Feuillade, part of Eric de Kuyper’s program of films about financial crises. My man Louis did not fail me.

In Le Trust, a businessman indulges in a bit of corporate espionage. He hires a detective (the sinister René Navarre) to kidnap an inventor and squeeze a secret formula out of him. The detective resorts to some unusual methods, such as hiring an actor to dress in drag and impersonate a rival’s wife. The inventor is kidnapped but outwits his captors with a trick that could have come straight out of Les Vampires. The plot’s outrageous surprises are played straight and brisk, and we can see Feuillade moving toward the compact, inventive staging of Fantomas and Tih-Minh. How could Le Trust not be my favorite movie of the week?

Tsars, Commissars, and Jews

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Véra Tcheberiak (1917) is probably more important for its subject matter than its fairly simple technique. The two-reel film was the third to treat a famous case of anti-semitic hysteria under the Tsar. In 1913, a Jew named Beilis was charged with ritual murder of a Christian child, and it became Russia’s Dreyfus affair.

More elegantly directed was Evgenii Bauer’s worldly, somewhat cynical Leon Drey (1915) which retains its fascination. (I wrote about its staging in an earlier entry.) But its intertitles still need to be restored.

Two later films were strongly marked by Soviet montage influence. In The Five Brides (Piat Nevest, 1929-1930), a shtetl is threatened with a pogrom by a gang of bandits. The band will spare the citizens if five virgins can be offered to their leaders. Director Aleksandr Soloviev accentuates this dramatic situation with every trick in the montage playbook: fast cutting, low angles, handheld shots, dynamic graphic conflict, and even explosions and bursting waves as Red partisans ride to the rescue. The final moments are missing, but there is plenty to savor, including an emotionally complex scene in which the elders decide to sacrifice their five virgins and suffocate a young man who is trying to stop them. The film was revised for Russian release, but we saw the original Ukrainian version.

No less engaging, though a little more formulaic, was Remember Their Faces (Zapomnite ikh litsa, 1931). A young Jewish worker devises a machine to speed the work of a tannery, but his efforts are blocked by saboteurs and anti-Semites. In a slap to the New Economic Policy, the chief villain is a private entrepreneur who wants to make the tannery uncompetitive. The scenes in which Beitchik is casually bullied by young thugs are quite strong. The final moments, when the bullies won’t even let Beitchik leave town unmolested, present the stirring image of the Komsomol youths marching to rescue him. Such support did not materialize behind the scenes: the film encountered censorship at every stage and was given a modest release.

Despite a 1927 Party directive ordering films treating anti-Semitism as a threat to socialism, both The Five Brides and Remember Their Faces encountered obstacles at every turn, largely on the grounds that the Party was given too small or too passive a role. In a fine book accompanying the series, Valérie Pozner supplies details of how the films were censored and suppressed.

Capra, company man

Donald Sosin gives us Scott Joplin’s “Wall Street Rag” (1909), uncannily appropriate today.

One of the highlights of this year’s Ritrovato was the Capra series, featuring his surviving silent work and several early sound pictures. We were also lucky to have Joe McBride, professor, critic, and UW alum, there to introduce many sessions.

I didn’t attend the talkies, having seen the batch except Rain or Shine (1930), but several of the silents grabbed my attention. Most seemed to be attempts by Columbia to hitch a ride on the bigger studios’ successes.

The Way of the Strong (1928) is a post-Underworld exercise in hoodlum redemption, graced by vigorous action, swift cutting (4.3 sec ASL by my count), and nice juggling of recurring props (mirrors, pistol barrels, a book devoted to great lovers). And the plug-ugly hero is truly ugly, none of your Hollywood fake-ugliness; a face only a blind girl could love. Submarine (1929) is a take on the What Price Glory plots analyzed by Lea Jacobs in her recent book. Two amiable sides of beef brawl and drink their way through navy life until a woman comes between them. The sexual rivalry is compelling, and the suspense during a stifling undersea rescue is admirably sustained. The Younger Generation (1929) owes something to the back-to-your-roots impulse of The Jazz Singer. Based on a Fannie Hurst story, it tells of a Jewish family that rises into society because of the son’s business acumen; in the process, class snobbery makes them increasingly unhappy.

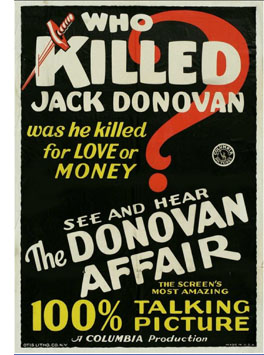

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

The movie was made in both silent and sound versions. Our print was silent, but it had no intertitles. At first blush it seemed to be the sound version without its track, sort of a 000% talking picture. The print’s average shot length is 9.3 seconds—too long for most late silents, but typical of some early talkies. Yet this did not look like any 1929 American talkie I have seen.

It had silent-film lighting, some huge lip-sync close-ups, and very smooth cutting. Except for a couple of moments, it lacked the jerky reframings, the long-lens imagery, and multiple-camera coverage typical of shooting from booths, the common practice of early talkies (and the talking sequences of The Younger Generation). Capra’s setups sat well inside the action, as was the case in 1920s silents and as would be the case in single-camera sound films a few years later.

Crazy as it sounds, I had to wonder if we were seeing a copy of the silent version made before titles were inserted! This is very unlikely. But if this was indeed an early talkie version, Capra was able to shoot sound with a fluidity that directors at bigger firms didn’t display—and in a rented studio at that, if the AFI Catalogue is to be believed. On the road and away from my research base, I can’t investigate further, but if you know more about the Donovan Affair affair, feel free to correspond and I’ll add postscripts.

Whatever the provenance of that Library of Congress print, the other silent/ early sound Capras have been admirably buffed by Sony’s Grover Crisp and Rita Belda (another Wisconsinite). The prints’ sparkle and sheen prove that even a minor-league studio (which Columbia was then) could turn out gorgeous imagery, thanks in no small part to cinematographers like Joseph Walker and Ted Tetzlaff.

Miscellany

The Lewinsky Dog surveys the climactic battle in Karadjordje (1911).

Be Patient! Department: Anke Wilkening, who was among those announcing the discovery of a new Metropolis print last year, gave us an update on the restoration process. The archivists are nearly done integrating the Argentine footage into the whole. Next comes the cleanup phase—awkward because the original Argentine print was heavily scratched and what we have is a 16mm copy and cropped for sound at that.

So far, the restored footage is clearly making secondary characters like Josaphat and the “Thin One” more prominent. But even the Argentine print is lacking things known to us, as three clips illustrated. Getting everything in some order will take time. Anke promises another report next year.

Box sets routinely attract attention at Bologna’s annual DVD awards, and this year things went according to form. The top prize went to Joris Ivens, Wereldcineast, a vast assembly of rare work by the Dutch filmmaker. Another generous package, Flicker Alley’s Douglas Fairbanks set, won best silent-film box set. (We have an entry on it.) Two more big collections, GPO Film Unit Collection vol. 2 (BFI) and Treasures from American Archives IV (Film Foundation) triumphed in the Sound Film and Avant-Garde categories.

Other winners: the two Vampyr releases (Eureka and Criterion) and Berlin, Symphony of a Big City (Munich Filmmuseum) for their rich bonus materials; Vittorio De Seta’s documentary collection Il Mondo Perduto (Feltrinelli Real) and two studies of Pasolini’s La Rabbia (Raro) in the Rediscovery category. Cinema Ritrovato wisely acknowledges that DVD producers are contributing powerfully to research into film history and are making rarities available to viewers who live far from festivals, archives, and cinematheques.

Not heralded—in fact, just sitting on the counter at the ticket booth—were still other DVDs, this time from Serbia. Sharp-eyed Olaf Müller pointed them out to me, and I’m grateful he did. Two volumes from the “Film Pioneers” series include a set of newsreels and, happily, the 1943 Innocence Unprotected (which Makavejev “decorated” in his revised version of 1968). A third disc consists of Karadjordje; or, Life and Deeds of the Immortal Duke Karadjordie (1911). This is the first Serbian and Balkan feature, and is thus, as the box text indicates, “one of a kind.” Same goes for Cinema Ritrovato itself.

Gian Luca Farinelli and Peter von Bagh, two more we have to thank for a great festival.

Just in time for Bologna, the historical journal 1895 has published a splendid special number on Le Film d’Art, ed. Alain Carou and Béatrice le Pastre. Feuillade’s Le Trust is available on the Gaumont early years DVD set and will soon be released on a Kino set drawn generously from the Gaumont collection. Keep your eyes open for early Capra features on Turner Classic Movies; several have run there recently.