Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Back in Bologna

The newly restored version of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly on the Piazza Maggiore.

Kristin here-

This year, the main complaint about Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival held by the Cineteca Bologna, is that there’s too much to see. With three venues playing films against each other, plus the 10 pm screenings each evening in the Piazza Maggiore, there’s no way to see everything. Some people complain that the conflicts are becoming worse-but I remember these same complaints about the over-abundance of films coming in previous years as well. Yes, it’s frustrating at times, but being offered more films than one can watch is a problem a lot of people would love to have. Basically one either chooses a couple of threads to follow through or just goes to whatever appeals in any given time slot.

According to the 2009 festival’s newsletter, there were 810 attendees, including 557 from outside Italy.

This year there have been several main focuses: a retrospective of Frank Capra’s silent and early sound films; a portion of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse’s program of Jewish-themed Russian and Soviet cinema from the 1910s to the late 1940s; a selection of color films from the early years of the twentieth century to the 1960s; a survey of the work of Vittorio Cottafavi; the annual “100 years” program, this time from 1909; the sea films of Jean Epstein; the silent Maciste films; and many other items.

Even between the two of us, we could not take in nearly all of the riches on offer, so here’s some of what I managed to see, with David’s report to follow.

An annual hundredth birthday

Each year the festival has a thread of programs of films from one hundred years earlier. This tradition started in 2003, when Tom Gunning was asked to put together groups of films from 1903. Thereafter Mariann Lewinsky took over as programmer for these threads. In recent years, her choices have been supplemented by small groups of films chosen by individual national film archives. This year Tom programmed the 1909 Griffiths and a group of other U. S. titles.

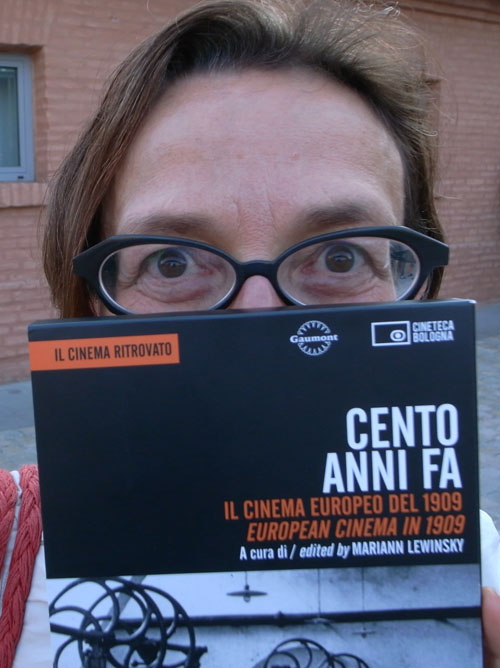

Maybe it’s just my impression, but the hundred-year packages seem to gain in prominence and popularity each year. Presumably in response to such popularity, the festival has just released a DVD with a selection of 22 shorts from this year’s 1909 program: Cento anni fa: Il cinema Europeo del 1909/European cinema in 1909 (running two hours and twenty minutes and presented below by Mariann). It contains only about a fifth of the roughly 100 films screened, but many of the others are available in online archives. DVDs of previous years’ programs are in the works, with 1907 soon to come. The DVD and other publications of the festival are available here.

I managed to see most of the 1909 programs but obviously can mention only a sampling. Undoubtedly the highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

French director Alfred Machin contributed two excellent dramatic films, both involving windmills: Le Moulin maudit (also on the DVD) and, in the program of early color films, L’Ame des moulins. Comedy stars were represented by two Cretinetti films and a strange Max Linder film in which he becomes Amoreux de la femme à barbe (“Infatuated with the Bearded Lady”).

There were a great many documentaries giving glimpses into the world of 1909. Airplanes were much in  evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

Mariann watched a great number of 1909 films in order to make her selection. Her experience convinced her of what many of us feel, that this was a turning point for the development of film art, though perhaps not as dramatic a one as 1913. Apart from L’Assommoir, Griffith’s The Country Doctor could be pointed to as evidence that the year saw films of a greater complexity and beauty than had previously been released. Griffith may no longer be quite the lone giant of the pre-1920 era that film historians have portrayed. Still, there are touches in The Country Doctor that no other director could have conceived, such as the early shot of the central family strolling through a field of tall grass that hides everything except the doctor’s top hat floating above the stalks.

Reaching 1909 raises the question as to how long these 100-year anniversary programs can continue and what form they should take. With fiction films getting longer in years to come, particularly in Europe, there emerges a problem of including enough of them to give a sense of a single year without having the programs expand even more. Perhaps non-fiction films will figure as an increasing proportion of this thread-with more Lewinsky dogs inadvertently captured for posterity.

A garland of color films

Two programs of early color films demonstrated the various processes: hand-coloring with stencils, tinting, toning, and attempts at photographic color. The only really successful of the latter were two 1912 shorts using the Gaumont system, which provided images in sharp, reasonably true color.

I caught only a few of the features in the color thread. Victor Schertzinger’s Redskin (1929), in two-strip Technicolor, was a beautiful print. Despite its implausibly happy ending, this story was a sophisticated look not only at racial tensions between whites and Indians but also at equally divisive tensions among Indian tribes. Like the other occasional films of the early decades that show the action from the Indians’ standpoint (Griffith’s The Red Man’s View figured in the 1909 program) are remarkably sympathetic to their culture. The color portrays not only the beautiful desert landscapes of the American Southwest but also Navaho blankets and Pueblo sand paintings.

Toward the end of the week, when people asked me what my favorites had been so far, I forgot to mention Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, which had played way back on the opening Saturday. It has a reputation as a bizarre film, and I wasn’t expecting much beyond some glowing color images of two beautiful stars, Ava Gardner and James Mason. But I was pleasantly surprised by its well-handled fantasy tale of the Flying Dutchman visiting a contemporary Spanish seaside resort and finding his true love. In particular a lengthy flashback to the Dutchman’s original crime has a degree of stylization and intensity that allow it to avoid seeming absurd. The tale has an other-worldly quality that recalls some of Powell and Pressburger’s films-enhanced by the presence of cinematographer Jack Cardiff handling the Technicolor.

Unfortunately Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954) failed to similarly avoid a sense of the absurd in its overheated Tennessee William pastiche set on an isolated farm in the West. Lumbering dialogue lays out explicitly all the tensions among the members of the central family, exacerbated by the depredations of an elusive puma and a visit by the younger brother’s potential fiancée. The reason for its presence in the festival, though, was its color scheme. Wellman set out to make a “black and white film in color,” as the program describes it. Both the snowy landscapes and the interiors are dominated by white, black, and flesh tones, with the sole exception-the Robert Mitchum character’s bright red coat-disappearing from the action partway through.

Not only silents need restoring

Martin Scorsese’s influence hovers over the festival and the Cineteca Bologna. One of the two screening rooms in the Cineteca’s building is the Scorsese (the other being the Mastroianni). In recent years, films from the institution that Scorsese founded, the World Film Foundation, have been screened here. The WFF is dedicated to restoring and preserving films from countries whose archives might lack the resources to handle such major projects. This year’s presentations were Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (The Wave, 1936), Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia (known in English as The Night of Counting the Years, 1969), and Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The foundation also aided in the editing of Ingmar Bergman’s home movies into Images from the Playground (Stig Borkman, 2009).

I had seen The Night of Counting the Years in one of the faded 16mm copies that have long been the only form in which this Egyptian classic was available. The new copy is a vast improvement, finally revealing why this is considered perhaps the great Egyptian film. It is based around a true story from 1881, when a powerful tribe on the west bank at Luxor discovered a cave containing a huge cache of royal mummies and funerary goods that had been hidden away by ancient priests to preserve them after the extensive robbing of their original tombs. The tribe started selling items gradually on the illicit antiquities market, but one of its members revealed the location of the cache to the authorities, allowing them to salvage most of the mummies and their grave goods. The film was beautifully shot on location in the desert and temples of the west bank and provides a meditation on why the young man might have acted against the apparent best interests of himself and his family.

A 1991 Edward Yang film might not seem an obvious candidate for restoration, yet the complete version of A Brighter Summer Day was barely rescued from oblivion. The original negative does not exist, and the print materials on the shorter version were discovered to be moldy. Rescuing these and combining footage from both versions has resulted in a pristine new print of Yang’s greatest achievement. An in-depth look at Taiwanese society a decade after Chiang Kai-chek took over the island, it follows a middle-class boy drawn gradually into gang violence. The new version, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, looked great on the big screen in the Arlecchino.

This and that

A brief tribute to Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast included Laughter, the director’s first sound film. A romantic comedy, it stars Frederick March as a witty young composer aspiring to marry a wealthy society woman against her father’s wishes. The film has touches of Holiday and Design for Living, both films yet to be made. Laughter confirms d’Abbadie Arrast’s reputation as a good but lesser filmmaker in the Lubitsch mold.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

Demonstrating that history repeats itself, Belgian film scholar Eric De Kuyper programmed a selection of titles dealing with financial speculation and crisis. These included perhaps the best of several items from Louis Feuillade shown during the week, Le Trust ou les batailles de l’argent (1911). It stars René Navarre, who would soon play Fantômas, as an unscrupulous detective, and the action is more in the thriller mode than a serious depiction of French finances. Also included was a 1916 German feature, Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange”), with a fine performance by Asta Nielsen as a woman more successful in finance than in love.

More to come from David, on Capra, DVD awards, and personalities glimpsed by a roving camera.

For our previous Cinema Ritrovato entries, see here for 2008 and here, here, and here for 2007. For a thorough discussion of dogs in early film, with comments by Mariann Lewinsky, see Luke McKernan‘s authoritative entry here. On the occasion of Edward Yang’s death in 2007, David offered an homage to him and A Brighter Summer Day here.

Pierced by poetry

DB here:

If I had a time machine, I’d zip over to Japan between 1924 and 1940. I’d trade a year of my life here and now for a year there and then.

Why? First, because the world I see in the movies of that period holds an irresistible fascination for me. I’d like to walk through Ginza, take a train to a spa, wander through Asakusa, have tea at the Imperial Hotel, hike around the temples of Kyoto. Second, if I could go back, I could see all the films I will never see—the lost Ozus and Mizoguchis, of course, but also the films we don’t even know are important.

For Japanese cinema in the 1920s and 1930s was one of the triumphs of world cinema. That era produced not only the two directors who are arguably the very greatest but also a host of talents you can’t really call “lesser.” The bench had depth in every position.

There are good reasons for this burst of genius. Quantity affects quality, but not the way snobs think: The more movies a country makes, the more good ones you’re likely to get. Although Japan had only a little more than half the US population, before 1940 it turned out about as many features as America did.In 1936, both countries released about 530 domestic productions.

The Japanese directors who started in the 1920s had, like Ford and Walsh in their salad days, to feed this audience. We tend to forget that even exalted figures entered the industry as high-volume producers. Mizoguchi averaged about ten releases per year in his first three years, Ozu about six. Everyone’s pace slowed with the coming of sound, but the sheer volume of movies pouring from studios big and small reminds us that young directors had plenty of opportunities to hone their skills.

Probably the most startling instance is Shimizu Hiroshi. In a career that ran from 1924 to 1959, he’s credited with directing 163 films. The earliest one of his that I’ve seen is Seven Seas Part I; this 1931 feature was his seventy-fifth. “Next year,” he remarked in 1935, “I’m going to make only three films the way the company wants me to, and in exchange I can make two films that I want. I want a little more time. I’m too busy right now.” As things turned out, he signed seven films in 1936.

The great bulk of his work, 139 titles, falls before 1946. Fewer than two dozen of these seem to survive. With only about 17% of the films available, we have to keep our generalizations modest. Who knows what we would find in Love-Crazed Blade (1924) or Flaming Sky (1927) or Duck Woman (1929)? Shimizu contributed to a series, the “Boss’s Son” or “Young Master” films, of which only his first, The Boss’s Son at College (1933) seems to survive. What would we find in The Boss’s Son’s Youthful Innocence (1935) or The Boss’s Son Is a Millionaire (1936)?

Luckily, we’ve wound up with some extraordinary movies, not a clunker among the ones I’ve seen. If only a smattering of 1930s and 1940s titles is available, we should be happy that it was this smattering. Shimizu had concerns in common with Naruse Mikio and Ozu Yasujiro, but he established his own world, a rich tone, and a simple but subtle visual idiom. Along the way, he created some of the most heart-rending films in world cinema.

From the city to the spa

Shochiku talent at Izu hotspring, July 1928: Ozu Yasujiro (left), Shimizu Hiroshi (third from left), and screenwriters Fushimi Akira and Noda Kogo. Ozu and Shimizu were 23 years old.

Once more, all hail Criterion. TheTravels with Hiroshi Shimizu DVD collection released this spring includes Japanese Girls at the Harbor (1933), Mr. Thank You (1936), The Masseurs and a Woman (1938), and Ornamental Hairpin (1940). They were previously released on an expensive Japanese set (with English subtitles), but Criterion’s Eclipse series offers them at a more reasonable price, along with brief but helpful notes in English by Michael Koresky.

The collection’s title highlights the image of Shimizu that emerged in the 1980s. The films that struck Western critics then were typically shot outside the usual big cities (Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka), in the mountains and seaside towns of the Izu peninsula. John Gillett’s 1988 National Film Theatre program, the first extensive survey of Shimizu’s work outside Japan, was entitled “Travelling Man.” Not only did Shimizu take his crew on the road, thanks to the expansion of the railway system, but he also exploited what became known as his signature technique: lengthy tracking shots down a road, following characters walking toward us.

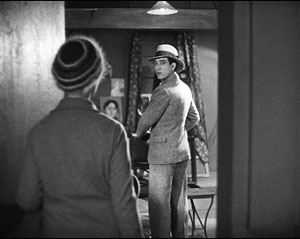

Like Ozu, Shimizu worked in modern-day genres (gendai-geki), from slapstick comedies to college sports films. Most of what survives from before 1936 are social dramas of families, friendship, and fallen women. Seven Seas (1931-1932) deals with class conflicts, as a poor girl marries into a rich family and discovers that her husband is a bounder. Eclipse (1934) centers on the failure of young people from the countryside to succeed in a recession-hit Tokyo. The title of Hero of Tokyo (1935) is ironic, in that the stepson who abides by a mother held in disgrace by her other children, winds up destroying her last scrap of respectability. In Japanese Girls at the Harbor, two schoolgirls are driven apart by one’s passion for a young man. After a violent confrontation, she becomes a prostitute and her estranged friend winds up marrying him.

The Shochiku studio deliberately pursued a female market, and these tales of family intrigue and endlessly suffering mothers, wives, and daughters offer obvious figures of sympathy. Less predictably, the films simmer with criticism of modernizing Japan. They focus on the corruption of the upper classes, the collapse of traditions in the countryside, and the uprooting of the extended family.

Most significantly, Shimizu’s films indicate quite explicitly that Japan’s growing prosperity in the 1910s and 1920s was built on the backs of the rural poor, particularly the young women who flocked to textile mills, city shops, and brothels. Like many films of his contemporaries, Shimizu’s urban films mix sentiment and comedy with a harsh appraisal of social tendencies. I’d bet that we’d find both qualities in his Stekki garu (1929), a film apparently about the current craze for “walking stick girls,” women whom men hire to accompany them on strolls.

The manager Kido Shiro summed up the Shochiku spirit in the formula “smiles mixed with tears.” Ozu offered this blend in films like I Was Born, But… (1932) and Passing Fancy (1933), but there are precious few smiles in Shimizu’s surviving early thirties output. Then he took to the road.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

The easygoing plots echo the movies’ production process. Shimizu wasn’t an obsessive planner. Whereas Ozu sketched every shot and checked the composition through the camera, Shimizu wrote minimal screenplays and seldom budged from his chair, even when the camera was traveling. He shot quickly, making up dialogue as needed and giving actors the most cursory direction imaginable. (“Run.”) Yet this wasn’t a high-pressure situation. Some days, uncertain about what to do, Shimizu would shut down the shoot and take people swimming.

Tears and smiles

I don’t want to leave the impression that Shimizu was careless; below I’ll try to show that he set himself some powerful storytelling problems. And his relaxed manner yielded a unique mixture of traditional drama and more vagrant appeals. Take Mr. Thank You, my pick for the crown of the Criterion set.

It’s a road movie, although the trip runs only twenty miles. A rickety bus winds through the mountains around the Kawazu region of Izu, an area of hot springs and tiny villages. The handsome, kindly young driver is known only as Mr. Thank You (Arigato-san) because whenever he forces walkers off the road he waves and calls his thanks. He has earned the devotion of people in the region, who entrust him with messages and duties on their behalf. On this particular day, his bus is carrying a stuffy real-estate agent; a wisecracking moga (modern girl); and a young girl whose mother is accompanying her to Tokyo, where she is to be sold into prostitution. Other passengers—wedding guests, lonely old men—get on and off in the course of the trip.

The bus stops often, and the encounters give us vignettes of the deteriorating life of the countryside. We hear of the magic attractions of Tokyo, reported by a prosperous woman about to get married. A Korean woman working on road construction asks Mr. Thank You to visit her parents’ grave, reminding us that this oppressed minority has contributed its sweat to the new Japan. Counterbalancing these stabs of pure feeling are simple running gags, such as one involving rude auto drivers who insist on passing the bus. And across the trip, the fate of the girl draws ever closer.

The moga (evidently a hooker) becomes our raisonneur, commenting on everyone’s motives, denouncing hypocrisies, flirting with Mr. Thank You, and eventually offering advice on how to save a life. Shimizu fills his film with talk and music, but in quieter moments imagery takes over: shimmering valleys below zigzag mountain roads, tunnels and forests and glimpses of steep paths along which road workers trudge. Within the bus, point-of-view is channeled fluidly. At one point we watch the moga watching the driver watching the girl. The climax of the action is simply omitted, yielding a quick, upbeat coda. In sum, Mr. Thank You radiates the cheerful, compassionate resilience of its namesake.

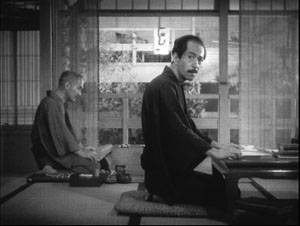

The mixture of tears and smiles is present as well in The Masseurs and a Woman. In Japan, blind people traditionally have taken up the trade of massage. So we start on the road, tracking back from two masseurs feeling their way along. The gags start immediately, with one praising the view, but poignancy comes just as fast: “It’s a great feeling to pass people who can see.” And again a gag undercuts it: “I bumped into some horses and dogs, though.” Shimizu sets up his brand of incidental suspense—uncertainty about matters of no dramatic moment—when the two begin to guess how many people are advancing to them. Eight and a half? We wait and, when the shot comes, we quickly count to check.

This seesawing between humor and pathos defines the tone of the whole film. Once the men arrive at the inn, we’re introduced to several guests, and a notably piecemeal plot: an aborted romance, a mysterious theft, and the attraction of one masseur toward an enigmatic woman. On the light side, students who tease the blind get extreme massage makeovers, reducing them to hobbling the next morning in a parody of the blind men’s halting gait. Shimizu assures their humiliation by head-on shots of modern girls hiking into the midst of them. And of course the blind-guy jokes multiply when several masseurs are trying to navigate a room or a street. Again, the film is over before you know it, leaving that Shimizu tang of chance encounters and what-if possibilities.

Blind masseurs play a minor role in another spa movie, Ornamental Hairpin (1941), but an almost-begun romance is there as well. Two women, Okiku and Emi, pass through an inn, and after they’ve left Emi’s hairpin jabs a young soldier’s foot. He will spend the rest of the story recovering his ability to walk. Emi returns to the inn and joins its summer guests: a cranky professor, a grandfather and his two pesky grandsons, and a married couple.

“Pierced by poetry,” says Nanmura casually about his wound, but the professor extrapolates on the phrase, trying to weave a romantic plot out of the accident. Shimizu declines to share the fantasy. A bit like Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday, the film is threaded with mundane vacation routines that become running gags, overwhelming what we expect to shape up as a courtship.

Bronzing in the sun and helping Nanmura recover his ability to walk, Emi comes to believe that she has found happiness. She has fled Tokyo and wants to start fresh. But her past, either as wife or kept woman, is kept vague. In two remarkable scenes, one a phone conversation and the other a dialogue with Okiku, her situation is sketched. We start to fear that her man will even come looking for her.

But these bits of conventional plotting are drop away among prolonged scenes of spa gossip and lazy pastimes. The most suspenseful sequences are devoted to Nanmura’s gradual recovery—a sort of deadline, since when he walks again, he will leave. If ever a climax refused to arrive, it’s during the last ten minutes or so of Ornamental Hairpin. The moments of pathos or conflict we would ordinarily see are skipped over, and the surroundings of “minor” scenes become infused with regret.

Shimizu’s ramblings through Izu didn’t lead him to abandon his probing of urban anomie, as we can see in Forget Love for Now (1937). (This must be one of the great Anglicized Japanese titles. I rank it with Blackmail Is My Life and Go, Go, Second-Time Virgin.) And at the same time he consolidated that talent for which he was best known in his lifetime: the exploration of childhood. Children in the Wind (1937), Four Seasons of Children (1939), and Introspection Tower (1941) offer unsentimental portrayal of boys’ rituals and their tenacity in the face of hardship. Shimizu founded an orphanage after the war, and he employed some of his charges in postwar films like Children of the Beehive (1948). Shochiku’s second boxed set, also with English subtitles, gives us the first three I’ve mentioned, plus the schoolteacher drama Nobuko (1940).

East meets West, and North meets South

Ornamental Hairpin.

Japanese film studios differed from their American counterparts in encouraging directors to cultivate individual styles. Kido supposedly fired Naruse by saying, “We don’t need two Ozus.” While Shimizu is not as daring or meticulous a stylist as Ozu, he managed to cultivate a visual approach that, however straightforward, was capable of delicate refinements.

In general, the Shimizus we have conform to trends in Japanese films of his period. His silent films from the years 1931-1935 adhere broadly to the Shochiku house style, using plenty of cuts and single framings of individuals. Most of the surviving silents have average shot lengths between 5 and 6 seconds, completely normal for both Japanese and US silent movies.

More remarkable is the number of dialogue titles, which make up between 24% and 44% of all shots. This would be exceptional for an American film of the 1920s. Other Japanese films, particularly Mizoguchi’s, are heavy with intertitles, but Shimizu took the trend somewhat farther. The preponderance of dialogue titles may owe something to the presence of both American and a few Japanese talking pictures at the time, which justified more spoken lines. In addition, at this period the influence of the benshi, the vocal accompanist to silent films, was waning, and the movies were becoming more self-sufficient in their narration. The hundreds of titles flashing by in Shimizu’s films would specify the scene’s action and curb the benshi’s urge to improvise.

Shimizu’s silent films that survive also contain several instances of a technique I’ve called the “dissolve in place.” The camera setup remains fixed, but one or more dissolves convey the changes in the space across a period of time. It’s commonly used to show long periods; in A Hero of Tokyo, the family’s growing poverty is shown through dissolves that gradually remove the furniture they’re been forced to sell. The technique can be seen in American silent films, a major source for most Japanese directors. Here’s a lovely example from Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star (1929), as the partly paralyzed Tim struggles to climb onto his crutches.

Shimizu often goes a little further by matching the figures precisely across a dissolve. In The Boss’s Son at College, the hero comes home but then sneaks out in his bare feet, and the dissolves concentrate on the reversal of movement, first upstairs, then down.

Again, this device was used by other Japanese directors, even Ozu in some early works, but Shimizu seems to have clung to it longer than most.

In general, Shimizu’s silent films don’t borrow his pal Ozu’s more idiosyncratic techniques. Shimizu doesn’t employ intermediate spaces to link scenes, or create elaborately disruptive transitions, or embed characters in 360-degree shooting space. Sometimes he offers mismatched eyelines in reverse shots, but these don’t usually cultivate the graphically exact alignment we find in Ozu’s editing. Still, Shimizu does often construct a scene’s space in a distinctive way.

For one thing, he will stage many scenes in long shot or even extreme long shot. Within that sort of shot, he’s often drawn to deep perspective, often with a central vanishing point. This is most apparent as a visual motif throughout The Boss’s Son at College.

More interestingly, his fascination with perpendicular depth governs staging and cutting. Imagine a line stretched straight out from the camera lens. By 1935 this lens axis has become Shimizu’s lifeline, his equivalent of the surveyor’s level. Rather than filling the foreground with a big figure or a face or prop, and rather than spreading his depth items wide across the background, he will pack the most important people along the center axis, like crystals growing out from a string. Here are instances from Japanese Girls at the Harbor and Eclipse.

Shimizu’s co-workers have testified that he cared little for the 180-degree rule. Like many Japanese filmmakers, he played fast and loose with it. Instead of an axis running between the characters, he was more concerned with the axis of the lens itself. He often respects that by cutting from one shot to a point (along the axis) 180 degrees opposite.

He also respects the lens axis by cutting straight in and out. In Hero of Tokyo, the mother learns that her husband has pulled a swindle and fled; then the officials leave her alone with her children. Shimizu simply enlarges and shrinks her systematically along the axis. He takes us to the other side of the group for the climax, when her birth children pull away from her stepson. We see no other camera positions in the scene.

This patterning is less abrasive than it might appear because intertitles are sandwiched in among these shots. It’s an intriguing strategy for thrifty filmmaking, since it requires only a rudimentary set, but it also offers a simple way to inflect the drama. Similar axial cuts, though not cushioned by titles, can be found in the shooting scene of Japanese Girls at the Harbor (which may owe something to French and Soviet cutting experiments of the period).

The depth stretching out from the camera lens is crosscut by another plane, perpendicular to it. This plane is often a patterned surface—windows, grillwork, a bedstead. Again, instead of Mizoguchi’s or Ozu’s angular foregrounds, we have an east-west axis slicing through the shot. The frames become boxes, and the characters play out their dramas within the cells of a grid, as in Seven Seas Part II and Japanese Girls at the Port.

Here again, Shimizu is relying on a device that other directors were using at the time. Many compositions of the 1930s play peekaboo with characters and setting. Here’s a flamboyant example from First Steps Ashore (Shimazu Yasujiro, 1932).

So instead of defining space through exaggerated foregrounds, plunging diagonals, or curvilinear edges, Shimizu goes Cartesian on us. His most distinctive layouts rely on two dimensions, one running straight into depth, the other running left to right. The result is a discreet, foursquare style well-suited to concise storytelling (and presumably, to turning out films quickly). Shimizu’s peers indulged in flashier shots, but his persistent choices yield a quiet variant of that continuity system that was already the lingua franca of world cinema.

Hitting the road

What about the sound films? Many Shimizu films still rely on distant planes of depth, as in this shot from Children of the Wind, when, after the father’s arrest, the boys’ buddies arrive at a far-off vantage point.

Interiors will sometimes be given the axial-cutting treatment, as in this passage from Ornamental Hairpin.

And now the crosscut horizontal plane often gets actualized as rooms gliding by the lens in lateral tracking shots. But in general, interior scenes in this 1941 film aren’t as strictly organized as in the silent films. This corresponds to a general move toward more orthodox technique in Japanese films of the period.

Something more original happens in the outdoor traveling shots. Now Shimizu’s beloved camera axis finds tangible expression in the highway. His much-vaunted tracking shots up and down the road translate the silent films’ axial depth into forward and backward movement, and characters, again organized in relation to the axis, are presented with a new simplicity and directness. Rather than being a one-off device, the road shots seem to be a development of the Cartesian coordinates that Shimizu has experimented with in the interior spaces of his silent films.

Star Athlete offers some remarkable examples of the push-pull effects built around the axis—tracking back from advancing characters, or tracking toward retreating ones. But Shimizu’s most thoroughgoing exploration of the camera axis in transit takes place in Mr. Thank You. The first thirteen shots lay out a stylistic matrix, with variants dropped in to prepare us for more compact expression later.

Shot 1: A long shot of the bus approaching.

Shots 2-4: We get the bus’s point of view of the road, with road workers in view; head-on shot of the driver calling “Thank you!” as the men step back; and the bus’s pov of the road receding, with the workers resuming. Dissolve to:

Shots 5-7: Bus’s pov of horsecart ahead; reverse angle of driver calling, “Thank you!”; bus’s pov of cart receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 8-9: Bus’s pov of men toting wood; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of men receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 10-11: Bus’s pov of women carrying bundles; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of women receding. Dissolve to:

Shot 12: Bus’s pov of chickens in road. They scatter as we get closer.

Shot 13: Long shot of bus going into the distance as we hear, “Thank you!”

The cycles move from three-shot clusters to two-shot clusters to a single shot, and a gag at that. (This driver even thanks poultry for traffic courtesy.) As another touch, Shimizu’s prized dissolves-in-place are recalled when the pedestrians approached from the back transform themselves into figures dwindling into the distance.

The same insistence on rectilinear framing takes place on the bus. Using 180-degree reversals, Shimizu creates a remarkable variety of shot scales in the cramped space of a real vehicle, always obeying his self-imposed geometry–facing either forward or backward.

As the trip gains emotional intensity, Shimizu will vary his treatment of these principles. For example, the middle section’s emphasis on forward movement will be counterbalanced near the end by a string of shots of passengers already off the bus, passing into the distance as we roll away.

In Shimizu, compact storytelling is matched by a pictorial strictness that doesn’t seem forced or stiff. After all, people do tend to line up to face one another in depth, and roads and buses do seem to run in two directions. Poetry in language demands strictures of meter, rhythm, rime, and the like, for these can pressurize expressive energies. Shimizu’s films present a disciplined lyricism: powerfully oblique emotions are shaped by simple but rich techniques of storytelling and style.

Most of my information about Shimizu’s work habits comes from essays and interviews in Shimizu Hiroshi: 101st Anniversary, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong: Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2004). For more on Shimizu’s surviving silent films, see William Drew’s penetrating essay in Midnight Eye. Alexander Jacoby offers a sympathetic career overview atSenses of Cinema. For a filmography, see Jacoby’s A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day Stone Bridge, 2008). Isolde Standish reviews Shochiku’s studio policies in Chapter 1 of her A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film (Continuum, 2005).

Noël Burch was one of the first Western writers to appreciate Shimizu’s artistry. His indispensible 1979 book To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema is available in its entirety here. The Shimizu chapter, concentrating mainly on Star Athlete, starts here. I offer discussions of stylistic trends in Japanese cinema in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1988), available in toto here, and in two essays in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 337-395.

You can find passionate conversations about Shimizu and the release of these DVDs at the Criterion Forum. See especially the comments of Michael Kerpan.

Virginia Theatre on our minds

Left to right: Kristin, unidentified ardent moviegoer, Erik Gunneson, and Meg Hamel.

Kristin here–

A year ago, those of us attending Roger Ebert‘s Film Festival were forced to do without the presence of the moving force at the center of this lively annual event. Still in therapy from his health crisis of 2005, Roger fell and broke his hip. Characteristically, he struggled to convince his doctors that he could take an ambulance to Champaign/Urbana, but their caution prevailed.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Roger went onstage at intervals during the festival, and he made his first appearance to introduce the opening night’s film, the director’s cut of Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace and Music (1970). Thanks to dedicated software, Roger tapped out messages on a laptop and pushed a button. A voice with a British accent conveyed his words of welcome to us and to director Michael Wadleigh. Then Roger retired to the back of the theater, where a comfy chair is reserved throughout the festival for him.

Michael Wadleigh, Jocko Marcellino, and Dale Bell discuss Woodstock.

From the perspective of nearly forty years, Woodstock has become both a record of remarkable musicians in their prime and a valuable document of the youth culture of the late 1960s. I was a junior at the University of Iowa at the time of the concert, only about five months away from taking my first film course and changing the direction of my education from tech theater to cinema studies. Working on props and make-up for productions every night, I was only dimly aware of the concert or the film that followed.

I also admit I don’t know much about pop music. I kept asking David “Who’s that?” Jefferson Airplane, The Who, Joe Cocker, and others were just names to me, not people whose appearance or music I recognized. But I could appreciate the remarkable way in which the filmmakers were able to capture live performances: the fluidity of multiple, 16mm cameras filming onstage only feet from the performers, the maintenance of focus even when events were recorded at night in less than ideal lighting conditions, and the excellent sound recording.

The screening heralds the release of the new version on DVD on June 9. Amazon has it on pre-order in 3-disc Blu-ray and DVD boxes, as well as a 2-disc set. The third disc has some making-of featurettes and about two hours of additional concert footage left out of even this extended version. I can’t imagine anyone who wants a compilation of performances by this remarkable group of musical talent settling for the smaller set.

Von Sternberg and Jannings, round one

The Alloy Orchestra has become a fixture at Ebertfest. This year’s silent film was Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command. I hadn’t seen it in thirty years or more, and it’s better than I remembered it being. Of course, seeing a gorgeous print on the big Virginia screen with an excellent musical accompaniment does it more justice than an old 16mm copy. Von Sternberg’s images were luminous, and his depiction of silent filmmaking as accurate as anything you’ll see on the screen.

In von Sternberg’s autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, he spends most of the six pages devoted to The Last Command badmouthing star Emil Jannings, with a brief sidetrack to badmouth William Powell. Presumably he’s talking about their behavior on the set, since their performances are both impressive, with Jannings emoting away and Powell as stone-faced as Buster Keaton. Von Sternberg reports that he and Jannings vowed never to work together again. Maybe winning the first Academy Award as best actor changed Jannings’ mind, for a few years later he invited von Sternberg to direct him and Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. The rest, as they say, is history.

Drawing on their usual range of odd percussive objects, including a bedpan, the Alloy group provided a lively score. With Chicago Tribune critic Michael Phillips as moderator, Guy Maddin and I joined the orchestra members for a discussion afterwards. One of them hinted to me backstage that a score for Docks of New York might be in the offing, which would round off the von Sternberg series perfectly.

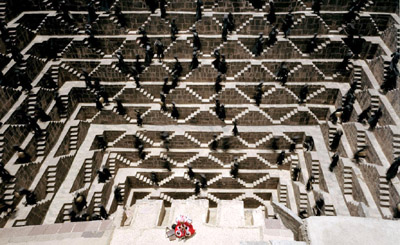

Saturday matinee

Last year the festival presented Tarsem Singh’s The Cell, with its delirious production design by Eiko. Tarsem’s 2008 follow-up, The Fall, got less attention in theatres, not having a star like Jennifer Lopez to carry it with audiences. It’s a complex fantasy set in a hospital during the silent-cinema era. There a suicidal, injured stuntman telling the tale of a band of mythical heroes bent on revenge to a seven-year-old girl with an arm cast. Her visions of the narrated events, set in spectacular landscapes and exotic buildings, mutate as she insists on changes in the story. The Fall was distinctly a crowd-pleaser, at least for the indefatigably enthusiastic audience in the Virginia Theater. Its Romanian child star, Catinca Untaru, is now twelve, and she proved an articulate charmer as she answered questions after the screening.

Ramin Bahrani with Catinca Untaru and her family.

The next film was Sita Sings the Blues, a marvelously imaginative animated feature by Nina Paley. I had seen the film two weeks earlier at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it was a treat to see it on the big screen again. It’s available for download in various formats here. I had the pleasure of moderating the discussion afterward, and I like the film so much that I’ll be blogging on it separately, including a transcript of the Q&A.

Tattling and bullying

DB here:

A Belgian friend, the late Michel Apers, admired American films above all others. One of the reasons, he explained, was that our films analyzed our political system with uncommon clarity. No other national cinema, he claimed, focused so insistently on the mechanisms and purposes of government, on the duties of citizenship, and on the dilemmas of public life. Not wanting to seem too chauvinistic, I said that we often failed to fulfill our nation’s ideals. “Of course,” he said. “But at least you have ideals. And your films show that it is not easy to live up to them.”

Michel’s remarks reminded me that we do have a tradition of politically critical films: 1930s films opposing lynching and hate groups, 1940s films about political corruption, still later movies like Twelve Angry Men and The Best Man and The Manchurian Candidate. Directors who contributed to this tradition include John Ford (Young Mr. Lincoln, The Last Hurrah), Otto Preminger (Advise and Consent especially), and Alan J. Pakula (All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, Rollover, The Pelican Brief).

Rod Lurie’s favorite film is All the President’s Men, which ought to tell you where his heart is. He made The Contender (2000), a subtle drama about a woman nominated for Vice-President. It has the trappings of a political thriller (the conspiracy at its heart echoes Chappaquiddock, as well as Blow-Out), but that’s just the bait for its serious questions. Graced by a warm but steely performance by Joan Allen, The Contender asks whether a woman in politics is held to a higher standard of sexual conduct than a man would be.

I thought of Michel Apers’ remarks when I watched Lurie’s Nothing But the Truth (2008) at this year’s Ebertfest. The plot revolves around a reporter, Rachel Armstrong (Kate Beckinsale), who outs covert CIA agent Eric van Doren (Vera Farmiga, her of the admirably crooked smile). Rachel refuses to divulge her source and goes to jail. Again, there’s a mystery to draw us through the plot: Who is the source? But more important is the problem of whether a reporter should be forced to name sources in a case that breaches national security. It’s the sort of issue that Preminger or Pakula would have loved to tackle.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

While the debate plays out, Rachel languishes in jail, her family and career dissolving. The case has some analogies to the Valerie Plame incident, but Lurie stressed that the film takes on a similar situation but not comparable characters. He was inspired as much by Susan McDougal’s tenacious loyalty to Bill Clinton.

The film’s secret about Rachel’s source is no mere Macguffin. It provides a powerful supplementary reason for Rachel’s silence, yet it doesn’t wholly excuse it. The film’s last scene leaves you wondering whether Rachel exploited her source. The film’s last shot suggests that she’s wondering too. That shot also wraps up a visual motif that hangs Rachel’s face on one extreme edge of the 2.40 frame, making her look precarious and vulnerable.

All in all, Nothing But the Truth is a sober, unsensational, gripping film about the press’s rights and obligations. It’s not surprising that Lurie was a professional journalist. During the Q & A, the questions were probing and he responded with rapid-fire, well-shaped sentences. There was good humor as well. After Lurie promised to tell us who slept with whom on the shoot, he paused and said: “All I’ll say is that Alan Alda was a complete slut.”

The opportunity for ordinary moviegoers to talk with such gifted and committed filmmakers makes Ebertfest one of the great film festivals on this continent. Roger’s urge to communicate with as many people as possible naturally inclines him toward creating communities, and the folks who gather annually in the Virginia Theatre form one of the most genial and generous group of movie lovers I’ve ever encountered.

Niceties: how classical filmmaking can be at once simple and precise

DB here:

A film academic once complained that I was too preoccupied with “formalistic niceties.” So here I go again. But read no further if you haven’t seen Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige.

Dueling magicians: The film’s premise might be considered high-concept. In turn-of-the-century London, two young conjurers launch their careers with different attitudes toward their craft. Robert Angier favors audacious showmanship, while Alfred Borden is committed to finding a trick that will baffle the experts. Their rivalry is ignited when Alfred accidentally kills Angier’s wife during a dangerous underwater stunt. Their struggle peaks around each one’s supreme trick: transporting himself from one point to another instantaneously.

The item that attracts my attention today is established in the film’s opening sequence. As the voice of Cutter (Michael Caine) explains a magic trick’s three acts, we see a climactic confrontation between the competitors. Hoping to discover Robert’s secret, Alfred watches the Real Transported Man performance from the audience.

As Cutter’s narration mentions “a man,” the camera picks out Alfred in the crowd. Cut to Robert onstage, a shift that establishes the two as our protagonists.

What interests me is the view of the bearded Alfred: a medium-shot framing him nearly in profile facing right. This framing will be repeated, but varied, when Alfred’s voice-over diary entry introduces both him and Robert as apprentices, working as audience shills for another magician:

We were two young men at the start of a great career—two young men devoted to an illusion, who never intended to hurt anyone.

The new shot parallels the introduction of Alfred in the first scene, but varies it. Again we see Alfred in the audience, but now without a beard, and the camera tracks rightward to show Robert in another row.

In this sequence, our protagonists are connected by a camera movement rather than the cut employed in the opening. The two men’s reactions—Robert grinning (his wife is onstage), Alfred more pensive—add to the characterizations that we will see played out.

This simple camera motif gets varied further in the course of the film. The disastrous immersion illusion that drowns Robert’s wife is initiated by another tracking shot of the two men in the audience, a variation of the earlier shot.

The new combination starts with Robert and ends on Alfred. At this point, not only are the two men linked but they replace one another. If you want to push your luck, you could say that this variant quietly affirms the film’s overall dynamic of substitution (doubles, twins, clones).

Earlier, a contrasting way of showing the men in an audience is given us when they attend a performance of the wizard Chung Ling Soo. Cutter provides a dialogue hook, warning Robert that “the blokes at the ends of row three and four” can see him kissing his wife’s leg.

Cut to our protagonists, sitting at the end of a row watching the Chinese magician.

A nicety: Now the men are sitting side by side and facing left rather than right. Just through camera placement and character position, we know we’re in a different performance, one in which our apprentices play no role.

As they study the trick, Nolan gives us another characterizing shot: Robert is amazed, but Alfred grins: He’s worked out Chung’s secret.

What would have happened if Nolan had framed the men sitting apart and/or facing to the right? For an instant we might have thought we were back in the act they shill for. Simple but reiterated differences assure immediate comprehension: medium shot/ long shot, looking rightward/ looking leftward, men in different rows/ men in the same row. Just as the repeated framings of their own act clarify the situation, so do these little polarities. Call it redundancy, if you like, but it’s also precision and economy.

With Julia’s death, the men become enemies. But each will still slip into the audience of the other’s performances. From now on, the magician is always on the right, the onlooker on the left. Nolan and company could have handled their rivalry in camera setups that exactly mimic the early ones. Instead, a new pattern of parallels comes into play, building on the earlier ones but different enough to heighten the symmetries.

The new pattern is set up by restricting our range of knowledge. First, we are attached to Alfred when he performs his bullet catch in a barroom theatre. Robert, seeking vengeance for Julia’s drowning, steps up to spoil the trick, but we don’t know he’s there until Alfred does, and then it’s too late.

Similarly, we’re restricted to Robert’s range of knowledge when he tries to execute his disappearing dove trick. Only when Alfred is about to trigger the collapsing cage—killing the dove and wounding a lady from the audience—does Robert realize that his adversary has struck back.

Another nicety: The two shots of each man in similar disguises, seen in 3/4 view, reset the stylistic parameters. But the image of the bearded Alfred is given extra punch through a tilt up from his missing fingers–the result of the parallel, bullet-catch scene before.

The whole pattern shifts yet again when Robert sneaks in to watch Alfred’s Transported Man illusion. We get a shot of him (in a beard again) that fuses two of the cues from the earlier scenes: He’s in the audience, as in the early sequences, but he’s shown from an angle congruent with that of the earlier beard shots.

And perhaps we can take the shot of Robert at home, telling of his amazement at Alfred’s illusion, as an echo of the initial prototype: A magician staring intently rightward at a dazzling trick played out offscreen, but now in memory.

Robert returns from Colorado with the Tesla-designed “Real Transported Man,” and Alfred’s visit to watch the stunt reworks the givens of this pattern yet again. Alfred is seated, minimally disguised, in the standard audience spot looking right, but he is not in profile and the camera position is much closer than before. The answering shot of Robert onstage recalls the gesture we saw at the film’s outset and anticipates what we will see when that opening scene is replayed, with the wicked Alfred climbing onstage.

At the close of the trick, yet one more variant: Robert appears in the rear balcony and the crowd all turns to watch him off left.

After a glance back, Alfred turns away, looking right–the first time any character has flinched from the performance. His puzzlement is mixed with anger (at last a trick he can’t see through), a less charitable response than we saw in Robert’s stunned fireside recollection of Alfred’s Transported Man.

The things held constant, such as camera placement and position in the locale, set off the differences in characters’ disguises and reactions, while this shot carries faint echoes of our very first view of Alfred during Cutter’s voice-over monologue. That view, and its answering shot of Robert in the spotlight, will recur when Robert’s pseudo-death is replayed.

Nolan’s audacious film is built out of more marked parallels than these, but I wanted merely to highlight the ups and downs of one small pattern. Many films work varied repetitions like these into their shot-by-shot texture. Back in the 1930s, Eisenstein saw this possibility clearly, as I try to show in my book on his work. In the 1960s and 1970s, Raymond Bellour called our attention to such patterns in films by Hitchcock, Hawks, and Minnelli. His collection of essays The Analysis of Film includes pioneering studies of how fine-grained such things can become.

I wouldn’t go as far as Bellour does in seeing varied repetition as the motor force of classical filmmaking, but it surely plays an important role. What he takes as a manifestation of pure textual difference I’m inclined to psychologize: these differences help the audience understand, usually without awareness, the ongoing narrative dynamic and have the extra payoff of creating tacit narrative parallels. But from either perspective, object-centered or response-centered, studying such microforms is enlightening. It’s a way to understand films as wholes, dynamic constructions that shift their shapes across the time of their unfolding. Moreover, by examining things this closely, we can try to understand not only how this or that film works, but how this or that film relies on principles distinctive of a filmmaking tradition. Consider this another plug for poetics.

I’d add that such principles neatly fuse two pressures: toward narrative coherence and comprehension on the one hand, and toward production efficiency on the other. It’s cheaper and easier to repeat camera setups if you can. Artistic economy and financial economy can work together, nicely.

Speaking of repetitions….