Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Unsteadicam chronicles

DB again:

A spectre is haunting contemporary cinema: the shaky shot.

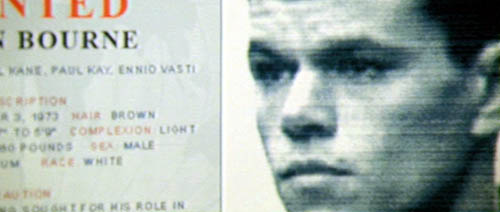

Viewers have been protesting for some years now. I recall friends asking me why the images were so bumpy in Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives and Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark. The Bourne Ultimatum, this summer’s wildest excursion into Unsteadicam, has put the matter back on the agenda.

If you drop in at Roger Ebert’s website, you’ll find many annoyed comments from readers about what one calls the Queasicam. The writers make shrewd points about the purpose and effects of director Paul Greengrass’s technique. I’ll try to add some historical perspective and a little analysis.

From whose Bourne no traveling shot returneth

First, what exactly are we talking about? Some viewers and critics think the jarring quality of the movie proceeds from rapid editing. The cutting in Bourne Ultimatum is indeed very fast; there are about 3200 shots in 105 minutes, yielding an average of about 2 seconds per shot. But there are other fast-cut films that don’t yield the same dizzy effects, such as Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (1.6 seconds average), Batman Begins (1.9 seconds), Idiocracy (1.9 seconds), and the Transporter movies (less than 2 seconds).

As for the series itself, The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, was edited a tad slower, averaging 3 seconds per shot. The second entry, The Bourne Supremacy, also signed by Greengrass, was as fast-cut as this, coming in at 1.9 seconds. People noticed the rough texture of the second one, but it didn’t arouse the protests that this last installment does. Something else is up.

Partly, it’s not the pace of the editing but the spasmodic quality of it. Cuts here seem abrasive because they interrupt actions and camera movements. Pans, zooms, and movements of the actors are seldom allowed to come to rest before the shot changes. This creates a strong sense of jerkiness and visual imbalance.

Still, a lot of the film’s effect has to be laid at the handheld camera. The technique in itself, however, shouldn’t shock us. The handheld aesthetic has been with us a long time. There were silent-era experiments with the technique by E. A. Dupont (Variety, 1925) and Abel Gance (Napoleon, 1927). It recurred sporadically after that, but in mainstream cinema handheld shooting became common in 1960s films as different as The Miracle Worker, Seven Days in May, Dr. Strangelove, and the dramas of John Cassavetes. Today, many films from Asia and Europe as well as the US rely on the device all the way through. The Danes call it the “free camera,” and I write about it here. The trend is so widespread that it’s been satirized: In the Danish comedy Clash of Egos (2006), when an ordinary workman gets a chance to direct a movie, he insists that the camera be put on a tripod, and the cinematographer complains that he hasn’t done this since film school. Directors nowadays tell us that they are in search of energy, a moment-by-moment spiking of audience interest. You can get it through fast cutting, arcing camera movements, sudden frame entrances, the nervousness of the handheld shot, or all of the above.

Roughhouse

I think the upsetting qualities of the visuals in The Bourne Ultimatum derive principally from the particular way the handheld camera is used. Several of Ebert’s writers complain that the camerawork made them nauseated, and there seems little doubt that the shots are bouncier and jerkier than in much handheld work. Adding to the effect is the fact that Greengrass often doesn’t try to center or contain the main action. Sometimes, as in a fight scene, the camera is just too close to the action to show everything, so it tries to grab what it can. At other times Greengrass pans away from the subject, or shoves it to the edge of the 2.40:1 frame. In the standard technique of over-the-shoulder reverse angles, we see one character’s shoulders in the foreground and the primary character’s face clearly. Greengrass likes to let a neck or shoulder overwhelm the composition as a dark mass, so that only a bit of the face, perhaps even just a single eye, is tucked into a corner of the shot. This visual idea was already on offer in The Bourne Supremacy.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I described contemporary films as employing “intensified continuity,” an amplification and exaggeration of tradition methods of staging, shooting, and cutting. (I explain a little about it in this blog entry.) What Greengrass has done is to roughen up intensified continuity, making its conventions a little less easy to take in. Normally, for instance, rack-focus smoothly guides our attention from one plane to another. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, when Jason bursts into a corridor close to the camera, the camera tries but fails to rack focus on his pursuer darting off in the distance. The man never comes into sharp focus. Likewise, most directors fill their scenes with close-ups, and so does Greengrass, but he lets the main figure bounce around the frame or go blurry or slip briefly out of view.

Essentially, intensified continuity is about using brief shots to maintain the audience’s interest but also making each shot yield a single point, a bit of information. Got it? On to the next shot. Greengrass’s camera technique makes the shot’s point a little harder to get at first sight. Instead of a glance, he gives us a glimpse.

Although this strategy is more aggressive in this third Bourne installment, we can find it as well in Supremacy. An agent pulls a document out of a carryon bag, and for an instant we can see the government seal. In the next shot the agent bobs in and out of the frame, as if the camera can’t anticipate his next move.

Later in Supremacy, the camera jerks across a computer display and suddenly focuses itself, evoking the jumpy saccadic flicks with which we scan our world.

Greengrass claims that his creative choices were influenced by the cinema-vérité documentary school and cites as well The Battle of Algiers, which helped popularize the handheld look in the 1960s. At other times he says that the style is subjective: “Your p.o.v. is limited to the eye of the character, instead of the camera being a godlike instrument choreographed to be in the right place at the right time.” But our point of view isn’t confined to what Bourne or anybody else sees and knows. The whole movie relies on crosscutting to create an omniscient awareness of various CIA maneuvers to trap him. And if Bourne saw his enemies in the flashes we get, he couldn’t wreck them so thoroughly.

The Bourne Ultimatum belongs to a trend of rough-edged stylization sometimes called run-and-gun. The film has been described as bare-bones but it’s actually quite flashy. All the crashing zooms (accompanied by whams on the soundtrack), jittery shots, drifting framings, uncompleted pans, freeze-frame flashbacks, and other extroverted devices call attention to themselves. You can find earlier instances in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and U-Turn, along with stretches in Michael Mann’s latest films. In milder form you find the style on display in TV crime shows, as well as in the notorious docudrama The Road to 9/11.

The most extreme practitioner of this style is probably Tony Scott. From Spy Game through Man on Fire, Domino, and Déjà vu, he has taken this aesthetic in delirious directions. His framing is often restless, as if groping for the right composition. In this shot from Domino, the camera starts a bit too far to the right, shifts left to frame Frances a little better, zooms back hesitantly, then finally stabilizes itself as he grins at the Motor Vehicles worker.

A single shot may give us not only changes of focus but jumps in exposure, lighting, and color; sometimes it’s hard to say whether we have one shot or several. The result is a series of visual jolts, as in Man on Fire.

Scott, trained as a painter, pushes toward a mannered, decorative abstraction, aided by long-lens compositions and a burning, high-contrast palette. For Supremacy, Greengrass adopted a toned-down version of Scott’s approach, while in Ultimatum, he favors drab surroundings and steely colors. Still, both men’s approaches to run-and-gun are frankly artificial, and both remain within the premises of intensified continuity. Of the Waterloo Station sequence Greengrass says: “It has got a sense of energy.”

The Bourne coverup

There’s one more function of Bourne’s style I want to consider. In an earlier post, I quoted Hong Kong cinematographers’ saying about the shaky camera. The handheld camera covers three mistakes: Bad acting, bad set design, and bad directing. It’s worth considering, as some of Ebert’s correspondents do, what Greengrass’s style may serve to camouflage. One suggests that because the cutting doesn’t let the viewer reconstruct the fights blow by blow, anybody can seem to be a superhero if the filming is flurried enough.

Just as important, the director who is just (apparently) snatching shots doesn’t have to worry about building up performances slowly; s/he can simply give us the most minimal, stereotyped signals in facial close-ups. Lengthier shots let the actor develop the character’s reactions in detail, and force us to follow them. Classic studio cinema, with its more distant framings and longer takes, lets you follow the evolution of a feeling or idea through the actor’s blocking and behavior. The villain in the average Charlie Chan movie displays more psychological continuity than the nasty agents in Bourne Ultimatum.

Moreover, run-and-gun technique doesn’t demand that you develop an ongoing sense of the figures within a spatial whole. The bodies, fragmented and smeared across the frame, don’t dwell within these locales. They exist in an architectural vacuum. In United 93, the technique could work because we’re all minimally familiar with the geography of a passenger jet. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, could anybody reconstruct any of these stations, streets, or apartment blocks on the strength of what we see? Of course, some will say, that’s the point. Jason himself is dizzyingly preoccupied by the immediacy of the action, and so are we. Yet Jason must know the layout in detail, if he’s able to pursue others and escape so efficiently. Moreover, we can justify any fuzziness in any piece of storytelling as reflecting a confused protagonist. This rationale puts us close to Poe’s suggestion that we shouldn’t confuse obscurity of expression with the expression of obscurity.

The run-and-gun style is indeed visceral, but let’s be aware of how it achieves its impact. I’ve argued in Planet Hong Kong that the clean, hard-edged technique of classic Hong Kong films allows extravagant action to affect us viscerally; by following the action effortlessly, we can feel its bodily impact. We’re shown bodies in sleek, efficient movement that gets amplified by cogent framing and smooth matches on action. But in the fancy run-and-gun style, cinematography and sound do most of the work. Instead of arousing us through kinetic figures, the film makes bouncy and blurry movement do the job. Rather than exciting us by what we see, Greengrass tries to arouse us by how he shows it. The resulting visual texture is so of a piece, so persistently hammering, that to give it flow and high points, Greengrass must rely on sound effects and music. As a friend points out, we understand that Bourne is wielding a razor at one point chiefly because we hear its whoosh.

What else does the handheld style conceal? Since the 1980s, in many action pictures the cutting has become so fast, and often capricious, that we can’t clearly see the physical action that’s being executed. That complaint is justified in Bourne Ultimatum, certainly, but here the style also seeks to make the stunts seem less preposterous. Instead of showing cars crashing and flipping balletically, Greengrass barely lets us see the crash. All the conventions of the action film are smudged in Bourne Identity, as if a sketchy rendering made them seem less outlandish. In a Hong Kong film, Bourne in striding flight, grabbing objects to use as weapons without missing a beat, would be presented crisply, showing him executing feats of resourceful grace. But many viewers seem to find this sort of choreography outlandish or cartoony. So when Bourne plucks up pieces of laundry and wraps them around his hands to protect them when he vaults a glass-strewn wall, Greengrass’s shot-snatching conceals the flamboyance of the stunt.

Finally, I’d argue that the style camouflages something else: plot problems. I’m not talking about the hero’s indestructibility, which is a given in this genre. John McClane in Die Hard 4.0 survives about as much mayhem as does Jason Bourne. But there are some howlers here that, because of the rapid pace and the just-barely-visible action, are somewhat muffled. By whisking the action past us and forcing us to keep up, the film doesn’t allow us to dwell on its holes and thin patches.

The plot, praised by so many, is actually a very simple one: Find Guy A, but when he’s killed, locate the clues that will lead you to Guy B, etc. until you get to Mr. Big. The mechanics of how the clues are pursued remain obscure. (Skip ahead to the next paragraph if you haven’t seen the movie.) Why would an all-powerful CIA operation house its key players in offices that can easily be watched from a neighboring building? How does Bourne get into Noah Vosen’s office, past all the security? Is the revelation of Bourne’s identity and his training regimen really much of a surprise? The wrapup, showing the bad guys exposed by the press and punished by government investigation, seemed risible, not only because of the current inability of either press or congress to right any wrongs, but because I had no idea to whom Pamela Landy has faxed the incriminating documents. “You can’t make stuff like this up,” remarks one sinister agency boss, but many, many films have done so.

I’m not against handheld styles as such, and even Late Tony Scott Rococo can have its virtues. Yet I find the style as practiced by Greengrass to be pretty incoherent and nowhere near as engaging as most critics claim. It just seems too easy. But then, I think that certain standards of filmmaking craftsmanship have pretty much vanished, and the run-and-gun trend is one more symptom of that. Given the praise heaped on The Bourne Ultimatum, however, things are unlikely to change. Next time you head to the movies, you might want to bring your Dramamine.

Thanks to Vance Kepley and Jeff Smith for engaging discussion about The Bourne Ultimatum.

The Bourne Supremacy.

PS: I’ve done a followup entry on the Bourne series, elaborating on these points and adding some new ones.

PPS: One more, I hope final, cluster of comments on Ultimatum, this time on the plotting.

PPPS 5 January 2008: Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style; thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to this.

PPPPS 22 September 2008: This blog post and its mates have stimulated critical discussion in Spain. Manuel Garin has a lengthy piece on the Unsteadicam style in Contrapicado.

Summer camp for cinephiles

Bruges, Belgium is a tourist haven. This reconstructed medieval city boasts museums, canals, cafes, an impressive town square, and other attractions guaranteed to keep credit cards flowing through. It’s a wonderful place to stroll in the sunshine, shop, or watch windmills slowly spin.

In alternating summers, though, Bruges plays host to people who prefer to sit in the dark. This strange cult includes professors, students, and cinephiles from all walks of life. For a small fee Belgians and Netherlanders can plunge into eight intensive days of viewing, lectures, and discussions. While tourists shuttle by unsuspecting, the devout are gathered to watch such items as Rebel without a Cause, the entire Niebelungen, and Destroy All Monsters.

It’s the Zomerfilmcollege, funded by the Flemish side of the Belgian government and run by the Flemish Service for Film Culture in partnership with the Royal Film Archive. In English we’d call it Film Summer Camp. There are no papers or grades. It’s a college in the original sense, a gathering of minds for purposes of deepening knowledge and expanding ideas.

It’s held in the Lumière cinema, a central three-screen moviehouse specializing in arthouse fare (and, for part of our stay, The Simpsons Movie). On the ground floor is a cozy bar, which also serves the lunches and dinners for the collegians. The whole building, like the atmosphere of the event, is unpretentious and welcoming.

Typically there are two principal courses and a sidebar. This year, one course was on Fritz Lang, the other was on widescreen film, and the sidebar was devoted to the French cinematographer Henri Alékan (La Belle et la Bête, Wings of Desire). The schedule is fairly full. At 9:00 AM there’s a lecture, followed by a film screening, then lunch. After lunch, another lecture and another screening. Dinner follows at about 6:30, and evening events follow, with a film or special presentation at 8:00 and then at least one more film afterward. All films are in 35mm prints.

A real workout

Kristin and I had been lecturers here several times, but this year I came alone. The Lang cycle was to have been handled by Tom Paulus, who gave us Hawks last time, but illness kept him away. He was replaced by several other fine Flemish scholars: Hilde D’haeyere, Steven Jacobs, and Roel Vande Winkel. They supplied lectures on Lang and architecture, on his relationship to the German “street film,” on his relation to the Nazi regime, and on his American work. The retrospective gave a good sampling, running from the Dr. Mabuse films (1922) to Moonfleet (1955; very nice print). For Alékan, there was the filmmaker/ archivist/ novelist Eric DeKuyper, for whom Alékan shot A Strange Love Affair (1984), and the Belgian professor Muriel Andrin, who incisively introduced us to visual influences on Alékan’s aesthetic.

Most lectures are in Dutch, but fortunately for me some are conducted in English. In previous years I’ve lectured on modern Asian film, Hollywood in the 1970s, and the history of film staging. This year my topic was anamorphic widescreen. The talks grew out of my research for an essay to appear this fall in my collection Poetics of Cinema.

The week is now about three-quarters done, and I’ve had a great time. Using clips and slides, I started with a block tracing CinemaScope in the US, with my main examples being Rebel, River of No Return, Moonfleet (intersecting with Lang), The Girl Can’t Help It, and Compulsion. Tonight we’ll get our example of modern usage of the widescreen with a showing of Three Kings.

The next three sessions concentrate on non-US usage of the anamorphic format. Le mépris screened today and will be discussed tomorrow. Oshima’s The Catch will represent a Japanese approach. On Sunday, we end with Johnnie To Kei-fun’s The Mission as illustrating one Hong Kong approach. By nice synergy, To’s Election and Election 2 are playing on other Lumière screens, so collegians can sneak off for some extracurricular viewing.

I enjoy visiting the college, and not just because I like to lecture. A schedule of screenings negotiated by what’s available in a good print from the archive or a distributor forces me to confront films I haven’t studied before. Even for those I know pretty well, seeing them big and beautiful can stimulate new musings. And as any teacher will tell you, even going back over familiar material shows you something fresh.

No lack of scope

For example, I had always loved the way Nicholas Ray used deep space to link his young protagonists in the police station at the start of Rebel. But this time I noticed how Dean’s performance was fitted to the wide frame: He begins the movie prone and pretty much ends there.

I also noticed how Jim’s gesture of covering the toy monkey at the start is echoed by his and Judy’s protective covering of Plato, and by the climax when Jim’s father covers him.

Viewers more familiar with Rebel than me have probably noticed these rhyming gestures and attitudes, but finding them on my own, innocently if you like, fueled my interest in teaching a film I had never studied closely.

Likewise, I wasn’t aware that the glasses motif in Compulsion is linked to imagery of blinding light, a kind of supernatural authority that not only points to the guilty party but also leads the monstrous, pathetic Judd to mercy. The dynamic is given diagrammatically in the closing and opening credits.

My previous post was about watching movies small and super-slow; now I’m reaping the advantage of watching films big and normally. Today, watching Godard’s Contempt on the screen I was able to enjoy those motifs of color, light, and composition that move almost musically through every Godard film (See top of entry.) I was able to identify some more citations (the novel adorning BB’s fanny is John Godey’s noir Frapper sans entrer) and feel the full force of the bold geometry of the framings. I hadn’t noticed before that the first image of the table lamp in the apartment sequence prepares, inversely, for the villa steps in Capri.

And I’d never noticed before how the last time Paul sees Camille, at the rocky outcropping that overlooks the seascape, she becomes that nymph seen in Lang’s rushes and identified as Penelope of the Odyssey.

Perhaps Camille is Penelope for Paul, but not necessarily for us. One task of the film is surely to make us suspicious of neat parallels between contemporary and classical culture; what Godard gives us graphically he often qualifies or negates elsewhere in the film. (1)

I expect to have some further fun with The Catch and The Mission, both of which will look splendid on the Lumière screen.

I turned sixty on the day I showed Rebel. Being here, though, I don’t feel so old. I have to keep up with the collegians and the dedicated archive team–Stef, Tim, Vico, Esther, and Joost. Their energy turns a medieval city into an exuberant adventure in cinema.

(1) After preparing my lecture, I discovered a wonderful website on citations in Godard, with special focus on Le mépris.

The Zommerfilmcollege gang, in 2.35 Scope. Photo by Esther Dijkstra.

Fantasy franchises or franchise fantasies?

Kristin here–

While David is watching films in Brussels, I’m back in Madison, overseeing some house renovations, moving into the publicity phase of The Frodo Franchise in anticipation of its release, and generally enjoying a chance to catch up on my reading.

I’ve also finally tackled one of those “someday we really must …” projects. Not surprisingly, a considerable portion of our home is given over to storing books, journals, file folders, DVDs, videotapes, laserdiscs, negatives, and slides. For all too long a heap of old magazines has been sitting on the floor in the aisle between two of our bookshelves, on the assumption that someday we really must triage these and file the clippings in subject folders where we might actually have a chance of finding them.

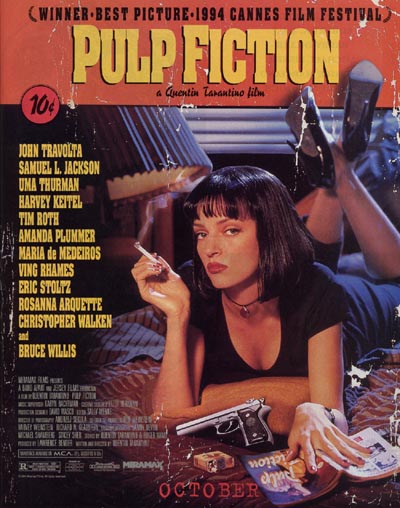

Most of these magazines are old issues of Premiere, mainly from the 1990s. Premiere ceased publication as of April, and I can’t say that I miss it greatly. It had slid distinctly by then, but back in the nineties it was actually pretty good. (J. Hoberman was writing regularly for it!) Every issue I’ve examined so far has at least one item worth saving, and sometimes two or three.

These issues aren’t in chronological order, so the first stack I scooped up to look through was a random batch, with the October 1994 issue on top. It featured a  big close-up of Brad Pitt on its cover. He was just on the brink of becoming a star, being best known to that point for his supporting roles in Thelma and Louise and A River Runs Through It. He had just finished Interview with the Vampire.

big close-up of Brad Pitt on its cover. He was just on the brink of becoming a star, being best known to that point for his supporting roles in Thelma and Louise and A River Runs Through It. He had just finished Interview with the Vampire.

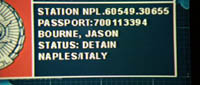

What interested me more was an ad that greeted me as I flipped the first few pages: the famous fake-worn-dust-jacket ad for Pulp Fiction. Odd that I had happened to begin with an issue from the season when one of the most influential films of the past two decades was being touted in preparation for its October release.

Indeed, the April issue happened to contain Premiere’s “Ultimate Fall Preview.” Naturally I got sucked into checking out what other films had been released that season. Given all the complaints these days about franchise films dominating Hollywood and pushing out the worthwhile films, I wondered just how good the good old days were.

To get a sense of what was going on in 1994, let’s start with the 10 top-grossing films of the year. Based on Box Office Mojo’s list of domestic grosses (in unadjusted dollars), they are: Forrest Gump, The Lion King, True Lies, The Santa Clause, The Flintstones, Dumb and Dumber, Clear and Present Danger, Speed, The Mask, and Pulp Fiction.

From our current perspective, the lack of franchise films on this list is striking. Only Clear and Present Danger, the second film starring Harrison Ford as Jack Ryan, belongs to part of an exiting series. The only film in a long-established franchise that came near the top was Star Trek: Generations at #15. Other sequels appear further down the top 50: The Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult (#23), City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly’s Gold (#32), Beverly Hills Cop III (#34), and Major League II (#45). No wonder sequels got a bad reputation!

On the other hand, several films in the top 10 spawned sequels: The Santa Clause, Dumb and Dumber, Speed, and The Mask. (Dumb and Dumber and The Mask both had their sequels considerably delayed by New Line Cinema’s inability to meet Jim Carrey’s skyrocketing salary demands and his resultant departure from the studio.)

In 1994, Hollywood was still in the early days of the franchise trend. After Batman in 1989, its sequel, Batman Returns, had come out in 1992, but that wasn’t enough to establish a pattern. Jurassic Park had appeared the year before but hadn’t yet seen a sequel. Aliens (1986) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) had both appeared seven years after the first films, suggesting that there was not exactly an automatic impulse to generate franchises. In fact, in 1994 we might expect to find Hollywood relatively untainted by franchise fever. Hence it should also very different from Hollywood today—if it’s true that franchises drive out other films. If all the anti-franchise critics are right, 1994 should also be a distinctly better year for auteurist fare, art-house movies, and stand-alone popular films.

What do we find in Premiere’s fall preview? In some ways it looks like a strong season. Apart from Pulp Fiction and Interview with the Vampire, there are Tim Burton’s Ed Wood, Robert Altman’s Prêt-à-Porter, Woody Allen’s Bullets over Broadway, Luc Besson’s Léon (aka The Professional), Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption, and Alan Rudolph’s Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle. Notable as well are Quiz Show and Nell. Buried in the “Also in Season” box at the end are Frederick Marx’s documentary Hoop Dreams, Clerks (with Kevin Smith not even mentioned), and Krysztof Kieslowski’s Red.

Alongside these films, though, there are the usual forgettable items: Junior (the Arnold Schwarzenegger-gets-pregnant comedy), Little Women, Disclosure, The Pagemaster, Radioland Murders and a bunch of other films that don’t get watched much anymore.

Putting aside the huge blockbusters of 2007, the fall season of 1994 doesn’t look all that different from the kind of fare Hollywood puts out now. Many of the same auteurs are with us. Burton is making Sweeney Todd (again with Johnny Depp). Allen continues to direct at his usual fast clip, albeit now in Europe. Besson promises more “Arthur” animated features. Darabont’s Stephen King adaptation, The Mist, is due out in November. Jordon’s thriller, The Brave One, starring Jodie Foster, is announced for September. Smith’s Clerks II came out last year. Tarantino tried to find inspiration by moving from dime novels to grindhouse movies, this time without success. The influence of his 1994 classic, however, is still very much with us. Even the unexpected success of Hoop Dreams is echoed by the recent vogue for documentaries. We have lost some of our major directors since 1994, of course, including Altman and Kieslowski, and Rudolph seems finally to have ceased being able to fund his eccentric independent films.

Is the fall season of 1994 typical? Premiere also used to run a chart of the year’s major releases called “Critics Choice,” which used a one-to-four-stars system to show how favorably each film was received by fifteen popular reviewers. Looking at the rest of 1994’s more memorable films, we find more familiar current directors , including Spike Lee (Crooklyn), the Coen Brothers (The Hudsucker Proxy), Ron Howard (The Paper), Oliver Stone (Natural Born Killers), John Waters (Serial Mom), Ben Stiller (Reality Bites), Zhang Yimou (To Live), Bille August (The House of the Spirits), Ang Lee (Eat Drink Man Woman), Kenneth Branagh (Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), Ken Loach (Ladybird Ladybird), James Cameron (True Lies), Robert Zemekis (Forrest Gump), Peter Jackson (Heavenly Creatures) and on, and on. Steven Spielberg would be there, too, if Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park hadn’t both come out in 1993. There is also the smattering of adorably eccentric (Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert) or beautifully acted (The Madness of King George) English-language imports of the sort that find an audience each year—not to mention the unclassifiable Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould. And 1994 was no richer in subtitled fare than recent years have been: apart from Red and To Live, the only other notable foreign-language import is Queen Margot.

I don’t want to push the similarities between this randomly chosen season and the current Hollywood situation too much. There certainly are some differences. The rise of blockbuster franchises has changed the pattern of releases, with the big series films occupying the summer and Christmas seasons. It’s interesting, for example, to note that the year’s top grosser, Forrest Gump, was released in July (a week before True Lies), while today it would probably be given a fall slot. That’s just a matter of timing, though. Even there we have distributors using counter-programming for smaller films, some of which inevitably become surprise successes, like The 40 Year Old Virgin.

So just what is it that got pushed out by franchises?

(For more on sequels and franchises, see the May discussion by the Badger squad and Henry Jenkins on the third Pirates of the Caribbean film. A lot of comments have been added to the latter since I first linked it. I see that Henry’s post was also cited by Lee Marshall in an article in the June 22, 2007 issue of Screen International, “The People’s Choice.” Marshall makes the point that reviewers who lambaste big franchise films often do so in a condescending way that implicitly criticizes the public for liking them.)

Arrivederci Ritrovato

The three chiefs of Cinema Ritrovato: Peter von Bagh and Gianluca Farinelli strategize, while Guy Borlée does some heavy lifting.

Our last days at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato were as busy as the first ones. Inevitably, choices, choices. Invasion of the Body Snatchers in a rare SuperScope print, or Asta Nielsen as Hamlet? Emilio Fernandez’s melodrama Enamorada (1946) or a 1907 version of Little Red Riding Hood, with a big dog playing the Wolf? You can’t see it all, but we offer some notes on some of the choices we made.

I can’t say that I am a great fan of Frank Borzage’s films of the 1930s and 1940s. For me his great period was the mid- to late 1920s. 7th Heaven (1927) somehow manages to climb beyond its blatant sentimentality, much as the hero and heroine ascend the stairs of their tenement apartment house, and earns our emotional investment in their transcendent love. For me, Lazybones (1925) and Lucky Star (1929) were the revelations of the Borzage retrospective during the 1992 Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone. It is a true pity that both remain largely unknown.

Borzage’s No Greater Glory (1934) was shown in a stunning print supplied by Sony Columbia. It didn’t fall into any of this year’s themes but was simply one of the “Ritrovati & Restaurati” items. The film deals with rival youth gangs in Budapest who organize themselves along strict military lines. Purportedly an anti-war tale, it manages to make the self-imposed discipline and even gallantry of the boys seem almost redemptive. I found the young hero, a scrawny but brave lad who struggles to be worthy of promotion within the ranks of his chosen gang, a bit too calculated to tug at the heartstrings. Still, it was entertaining, and the print showed it—and especially Joseph H. August’s cinematography—off to the best possible advantage. (KT)

While Kristin was watching Borzage, I decided to revisit Ilya Trauberg’s Goluboi Express (1929), one of the least known of the Soviet Montage films. Like Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia, it’s an attack on Western imperialism. Chinese, many sold into servitude, are packed into the rear cars of the train, while colonialists loll around up front. Two western soldiers of fortune attack a Chinese girl, and a young Chinese tries to defend her. This launches a prolonged battle and chase while the train roars on. By 1929, Trauberg had absorbed the lessons in cutting taught by Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, and he adds his own imaginative touches. The taut construction and torrential editing (over 1400 shots in less than an hour) create an electrifying experience.

This particular version is an intriguing rarity. In his introduction, Bernard Eisenschitz explained that Soviet authorities persuaded Abel Gance to distribute the film in France. Gance recut it to avoid censorship, and he commissioned musical accompaniment by Edmund Meisel, the experimental composer who scored Battleship Potemkin. Meisel’s score amplifies and sharpens Trauberg’s hammering visuals. (DB)

The book room was running for only about half the festival, so I was glad I nabbed my consumer durables early. Many high points, including a fascinating DVD collection of Marey films, but the most memorable, if only because of the struggle to carry it back home, is This Film is Dangerous. Published by the International Federation of Film Archives, this colossal book appears to present everything you wanted to know about this incendiary filmstock. It includes discussions of how nitrate came to be an ingredient of film, how the nitrate preservation movement (“Nitrate won’t wait”) started, case histories of restorations, poems in praise of nitrate, a chronology of nitrate fires, and an anonymous contribution called “Nitrate Pussy.” In all, virtually a film geek’s bathroom book, although its bulk demands a large lap. It doesn’t yet seem to be available on the FIAF website, but it should be soon.

Speaking of swag and plunder, Dan Nissen of the Danish Film Institute kindly gave me a copy of their latest DVD publication, the first of several volumes devoted to Jørgen Leth. It’s a handsome production and sure to increase interest in the man behind The Perfect Human and the target of Lars von Trier’s painstaking abuse in The Five Obstructions. It’s available at the DFI website. (DB)

Although Michael Curtiz’s 1929 epic Noah’s Ark has been shown at various festivals in recent years, I somehow had always managed to miss it. Perhaps this was just as well, since the print shown in Bologna as part of the salute to Curtiz is longer than most and has the original sound restored from the Vitaphone records. (More often the film has been shown in its silent version.) Piecing together bits from several release prints held in different archives, something approximating the 1929 release version has been reassembled and matched to the sound. The credits in the program—“Print restored by YCM laboratories, funded by Turner Entertainment Company and AT&T in collaboration with La Cinémathèque Française and The Library of Congress”—hints at the complexity of the task.

Like The Jazz Singer and other early talkies, Noah’s Ark has long stretches of purely musical accompaniment. At intervals, though, characters suddenly start speaking, usually at the lugubrious pace typical of performances at the dawn of sound. The effect is startling, especially when the transition happens within a scene. Such switches proved jarring to the reviewers of the day, but the chance to see a film hovering between silent and sound can be fascinating to a modern viewer. The pacifist message of Noah’s Ark reflects a general anti-war sentiment in Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s—a healthy reminder of a day when the majority of good, patriotic Americans could take a dim view of warfare. The film’s ending, in fact, optimistically declares that the Great War had put an end to all wars. (KT)

Having written a book on Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, I was particularly interested in a dossier on the director. It included a reconstruction of Die Flamme (1922), of which only one reel survives, using publicity photos, set designs, and descriptive intertitles. Though still short at only 44 minutes, this version gives a good sense of the plot, which was certainly not evident from the existing footage.

We have long known that Lubitsch’s intended first project in Hollywood was to be a version of Faust with Mary Pickford as Marguerite. That fell through, but it went far enough that screen tests were made. Twelve minutes of tests for a series of actors trying out for the part of Mephistopheles were shown. These were not exactly a revelation, but they do shed light on this transitional moment in the director’s career. (KT)

What do we do with a terrible movie by a sublime filmmaker? I’d argue that at least three directors achieved greatness in the years before 1920: D. W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade, and Victor Sjöström. Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), and Sons of Ingmar (1919) remain deeply moving and cinematically inventive. Sjöström moved smoothly from the fixed camera, long-take “tableau” style of the early 1910s to profound mastery of continuity editing on the US model only a few years later. He continued into the 1920s with such key American films as The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

So it’s saddening to report that A Lady to Love (1930) is a turkey. Edward G. Robinson, in full hambone overreach, plays an Italian-American grape farmer who seems to be flourishing despite the Volstead Act. Tony brings a down-at-heel waitress from the big city to be his wife, and she grows to love him, despite a little indiscretion involving Tony’s best friend. The sort of inert stage adaptation that gave talkies a bad name, A Lady to Love is solely for completists (of which Cinema Ritrovato boasts many). It was Sjöström’s last Hollywood picture. (DB)

The programs of 1907 films continued to yield treasures. Max Linder’s career got going that year, and he had not yet settled into the debonair, top-hatted persona that would within a few years become so familiar. In the simple and not terribly funny Débuts d’un patineur, he plays a novice ice-skater reduced to tears at by the film’s end, and in the more amusing Pitou bonne d’enfants Linder is a bumbling soldier who loses a baby confided to his care by his nursemaid sweetheart. The same program contained Louis Feuillade’s ever-popular Le Thé chez la concierge, where the guests start carousing so loudly that they drown out the bell rung by tenants trying to get into the house.

There were many early attempts to record synchronous sound, though all too often the accompanying discs have been lost even if the image track survives. The 1907 films contained a few such, but one, La Marseillaise, had its singer’s original voice, remarkably clear and perfectly synchronized. The result was an unusually poignant and vivid sense of a link to a hundred-year-old performance, an immediacy that went beyond what most silent films can convey, wonderful though they might be.

A familiar but welcome short was La course aux potirons (“The Pumpkin Chase”), one of the great entries in the very familiar genre of the day, the chase film. Special effects allow a wagon-load of pumpkins (looking like they were probably constructed from old tires) to bounce along city streets, up a chimney, and through windows, followed by the usual growing group of passersby. The inclusion of a donkey, duly hauled through the windows and up the chimney, makes the whole pursuit far funnier than in most such films.

Finally, the inclusion of a series of films about bomb-throwing anarchists, another common genre of the day, reminds us that the current international situation is not altogether a new one. (KT)

The DVD awards singled out efforts to making unusual cinema available in the DVD format. The top prize, Best DVD, was won by the Ernst Lubitsch collection, from Transitfilm and the Murnau Stiftung (available, with some variations, on Kino in the US). The committee commended it as “a model in the elegant packaging of rare materials in a form that is certain to attract new audiences.”

Anke Wilkening of the Murnau Stiftung accepts the award for best DVD.

Other awards: L’amore in città (Minerva, Italy), Best discovery; Seven Samurai (Criterion, US), Best Extras; the series on German cinema published by the Munich Film Archive, Best Series; and Akerman films of the 1970s (Carlotta, France), the French Naruse set (Wild Side) and the British Naruse set (Eureka), Best Box Sets.

Peter von Bagh commented that DVD producers are continuing the traditional work of film archives, and they often go beyond what archives can afford to tackle. Ironically, we sometimes find ourselves in the position of having excellent DVD versions of films that don’t exist in equally good prints. (DB)

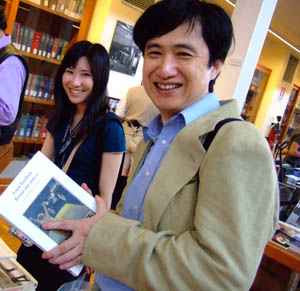

Finally, some snapshots. Glancing around the book room, you’ll see Sawako Ogawa and Hiroshi Komatsu pouncing on items.

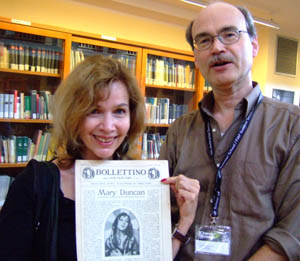

Not to be left behind, Janet Bergstrom and Richard Koszarski display Janet’s find.

Every year, Frank Kessler‘s birthday occurs during Ritrovato; this year was his fiftieth, and so Sabine Lenk made it a special treat.

At another meal, Danish film archivist Thomas Christensen, who really ought to know better, fends off the camera’s magical powers.

Same meal: shellfish and pasta sacrificed in a good cause.

Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and Kristin sample gelato. Later I ate the one in the middle.

On the final evening, the film cans are wheeled out. Ci vediamo l’anno prossimo!