Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Another Bologna briefing

More notes and notions from Cinema Ritrovato, all from DB:

Could you make a movie today about a farm girl who becomes a concert pianist under the sway of a womanizing egomaniac? The slightly nutty I’ve Always Loved You (1946) displays Frank Borzage’s usual faith in the way lovers communicate by spiritual ESP, this time aided by Rachmaninoff. Borzage talked the low-end Republic studio into this expensive project, and the result, though marred by strained performances, looks great in a glowing restoration by UCLA. A teenage André Previn darts through, and for once someone playing the piano onscreen (in this case Catherine McCloud) looks skillful. (The playback renditions were those of Arthur Rubinstein, credited as “the world’s greatest pianist.”) The title is perfectly ambiguous, since it could refer to any character’s attitude toward almost any other.

Travel delays prevented Ben Gazzara from introducing the fine print of Anatomy of a Murder. Too bad. It would be fascinating to hear how he developed his disturbing portrayal of an accused killer under Preminger’s notoriously dictatorial direction. But Gazzara did participate in an interview with Peter von Bagh that led into a screening of a beautiful restoration of Jack Garfein’s The Strange One (aka End as a Man).

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

He said that he loved Hollywood acting of the studio era: Gable, Grant, Tracy, and Stewart remain fresh and modern. When he saw Meet John Doe, he realized that Gary Cooper used his own version of the Method: “He did very little, but he did everything.”

Gazzara said that seeing Faces (1968) drew him to Cassavetes. “I was mesmerized. I was so jealous. I thought, I’ve gotta work with this man.” A year later he made Husbands. Cassavetes was very supportive, always “waiting for surprises.” He was laughing in enjoyment behind the camera, encouraging his players. “All you did was safe, and you could do no wrong.”

The Strange One, set in a Southern military academy, was Gazzara’s first film. He was offered the part of the cadet who eventually leads a revolt against the Machiavellian cadet Jocko De Paris. But Gazzara said that he wanted to play DeParis because “he got all the laughs.” George Peppard wound up with the good guy role. Though the film seems to me confused on several dimensions, Gazzara revels in the showy part of a soft-spoken, eminently reasonable sociopath. As in Anatomy of a Murder, he makes gently menacing use of a cigarette holder.

In the early 1930s, Japanese companies explored the possibility of exporting their films to Europe and the US. One result of these initiatives was Nippon: Liebe und Leidenschaft in Japan, a 1932 German compilation created by Carl Koch. It originally consisted of three films from the Shochiku studio, condensed and supplied with German intertitles. The original films were silent, so, oddly enough, synced Japanese dialogue was added.

In the version screened here, only two episodes were presented. What beauties they were! Since many of the 1920s and 1930s Japanese films that survive look quite weatherbeaten, it was wonderful to see, in the print from the Cinémathèque Suisse, how gorgeous quite ordinary movies from this era could be.

The first story, Kaito samimaro (orig. 1928), deals with a young samurai rescuing his beloved from the clutches of a corrupt priest. Brisk and beautifully shot, it came to the sort of frothing swordplay climax typical of the period—rapid cutting, dynamic tracking, and slashing assaults aimed at the camera. Kagaribi (1928), about a young vassal betrayed by his corrupt lord, likewise ended with a protracted action scene capped by a jolting climax. A prolonged tracking shot follows the young man’s former lover as she backs away from him, but then we cut to a full shot. With a single stroke he kills her, jaggedly ripping a paper door in his follow-through. Both stand motionless for a moment before she falls. A conventional finish, but no less eye-smiting for that. For more on the power of this action-cinema tradition, see an earlier entry on this site.

There are no fewer than ten flashbacks in the 1950 Swedish film Flicka och Hyacinter (Girl with the Hyacinths, above). Peter von Bagh’s Bologna programming has often highlighted Nordic work that’s little known outside the region, such as this engrossing post-Kane exercise in probing a dead person’s life. Teasingly directed by Hasse Ekman, the interlocking flashbacks would be savored by today’s puzzle-film aficionados, and the movie’s equivalent of Rosebud is genuinely surprising. The twist would never have been permitted in Hollywood of that era.

Kristin and I hope to post one more entry, probably soon after Ritrovato’s final session on Saturday. Lots more to report–Lubitsch, Borzage, Chaplin (of course), etc. For now, a glimpse of the official names of the Cineteca’s two screening rooms…

Cinema bolognese

Cinema Ritrovato, a festival of rediscovered and restored films, is now in its twenty-first year. We visited its two previous installments, and we found it one of the most hugely enjoyable festivals on the calendar. Where else can you see films from 1907, Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955), and a tribute to Ben Gazzara in a single week? Then there are the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, which attract hundreds of locals. The city plays host magnificently, with plenty of fine restaurants and perpetually cheerful people.

Mounting hundreds of screenings and panels is an enormous effort, but Gianluca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, Peter von Bagh, and all their colleagues have made it look easy. (The word sprezzatura comes to mind.) Here are our impressions from the first half of the event.

The home base is the Cineteca di Bologna, the local film archive. It’s located in a wide, quiet courtyard. It houses a large library and meeting rooms, along with two cinemas. During the festival, the Lumiere 1 auditorium specializes in silent screenings with piano accompaniment, while Lumiere 2 presents sound films. Widescreen titles and big events are reserved for the Arlecchino, a big, comfortable commercial theatre built in the era of roadshows and CinemaScope.

Organizing such a mixed program is more difficult in certain ways than presenting an event involving contemporary films, which are moving through the festival circuit already. Ritrovato must find good prints of titles that fit the year’s themes and also coordinate the ongoing efforts of archives that are restoring films.

A good example is a remarkable project overseen by Alexander Horwath of the Austrian Film Museum. One of the most famous lost films in US history is Josef von Sternberg’s 1929 movie The Case of Lena Smith. In 2003, Japanese scholar Komatsu Hiroshi found a fragment, in very good condition, in China. On the basis of this, Horwath and his collaborators created a wonderful book that reconstructs the film. It includes a detailed shot breakdown (based on one published in Japan during the film’s release), along with gorgeous stills, script extracts, summaries of critical reception in various countries, and essays about the film’s place in history.

The fragment, previously screened at the Giornate del Cinema Muto last fall, was tantalizing. Lena and her friend Pepi are in the Prater, Vienna’s dazzling amusement park, and they are eyed by two young officers. The women watch some of the sideshow entertainments before darting away, the officers in pursuit. Several of the shots evoke the heady atmosphere of the park, with prismatic, superimposed images of the sideshow attractions and—typical von Sternberg—a spinning ride providing pulsating visions of the crowd.

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

One of the threads of this year’s festival is the early US career of Michael Curtiz. The Strange Love of Molly Louvain (1932) is an energetic Warners crook melodrama. Starring Ann Dvorak and the ever-annoying Lee Tracy, the film displays Curtiz’s characteristically staccato direction. The scenes with hard-bitten reporters use overlapping dialogue in a manner that prefigures His Girl Friday. Rarer was The Third Degree (1926), an early instance of Europe’s “International Style” infiltrating Hollywood. For his first Warners project, Curtiz fills an implausible mother-daughter melodrama with cloudy superimpositions, canted angles, florid tracking shots, oddball angles, extreme close-ups, and frantic montages played with prismatic lenses. Richard Koszarski gave an amusing and helpful introduction. (DB)

One attractive constant of the Ritrovato is a series of short films from 100 years ago. Thus when we first attended in 2005, there were groups of shorts from 1905. As we progress through the early years of the current century, we go in parallel through the early years of the previous one. Each day one or two small groups of 1907 films have been shown, grouped by country or genre. These included some familiar items, like the poignant Le Bagne des gosses (“Children’s Prison,” Pathé) and the amusing British chase film, That Fatal Sneeze (directed by Lewis Fitzhamon). I have run across references to early Westerns made in Europe but had not seen any from this early period. Les Apaches du Far-West (produced by Pathé) is as unauthentic as one might predict, with the cowboys riding on English-style saddles and the shoot-outs with the Apaches taking place in bucolic fields and woods that are clearly in France, not the West. (KT)

A major new initiative for international film preservation was announced in May at the Cannes Film Festival. The World Cinema Foundation was founded by Martin Scorsese, and its advisory board contains such major filmmakers as Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Walter Salles, and Wim Wenders. The goal is to restore films made in nations that lack the archival facilities to do so locally.

The Moroccan Transes (El Hal, 1981), directed by Ahmed El Maanouni, is the new foundation’s first restoration, and it was introduced by the director and by its producer, Izza Genini. The titles crediting Giorgio Armani, Cartier, and Qatar Airlines as sponsors raised some surprised laughter in the audience, but if Scorsese and his colleagues can draw funding from such sources into film restoration, all the better. Transes is partly a concert film and partly a history of a band that became popular in the 1970s by expressing young people’s frustrations and rebelliousness. The big concert that begins and ends the film is exhilarating in its depiction of the crowd’s enthusiasm—but chilling as well as soldiers patrol the audience and occasionally suppress the more demonstrative spectators. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Our first visit to Italy for a film festival was in 1986, when Le Gionate del Cinema Muto, in Pordenone, presented a vast retrospective of Scandinavian cinema from the pre-1919 era. One of the major revelations was that alongside Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström, there was a third great Swedish director during the silent era, Georg af Klerker. The event also brought home to the audience one of the great tragedies of cinema history, the loss of many of Stiller’s and Sjöström’s films in an archive fire in the 1940s.

Every now and then, another film by one of these masters surfaces. This year the Ritrovato festival showed Madame de Thèbes, a 1915 Stiller film. As too often happens, the surviving copy, a French release print discovered by Lobster Films, was incomplete. The Svenska Filminstitutet has filled it out by inserting still shots created from copyright frames deposited at the Library of Congress and by replicating the original Swedish intertitles and letters. The result, full of sumptuous decor and extravagant plot twists, gives as good an approximation of the original as is now possible. It’s one more indication that the 1910s Swedish cinema was one of the glories of the silent era. (KT)

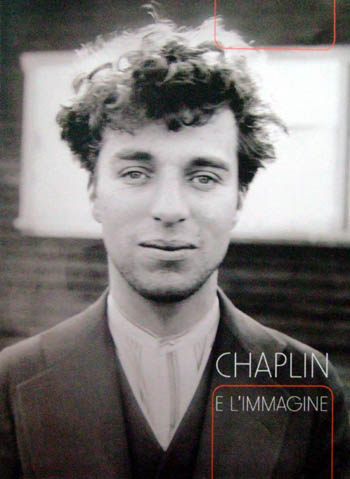

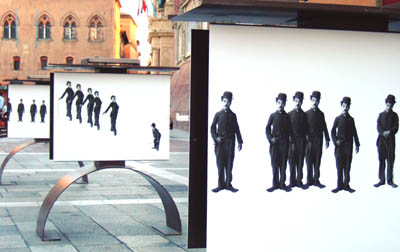

The festival has a close relation with the Charlie Chaplin estate; this is the place to come for the latest in Chaplin restorations and scholarship. Every year the festival mounts a tribute, including a superbly designed book on some aspect of Chaplin’s career. This year’s volume is a collection of rarely seen pictures, and its cover carries one of the most melancholy and haunting portraits of Charlie I’ve ever seen (up top).

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

A cloud was cast over our visit by the news of the death of Edward Yang (Yang Dechang). We admired his films and discussed them in Film History: An Introduction and my Figures Traced in Light. Edward was a likeable, tough-minded fellow. His films explored the effects of urbanization and politics on everyday life in Taiwan. He made his breakthrough to a broad international audience with Yi Yi (2000), but his other films, particularly Taipei Story (1985), The Terrorizers (1986), and A Brighter Summer Day (1991) are to me even more important. It’s a great loss that these aren’t easily available on DVD. When I get back to Madison and have access to pictures from my encounter with Edward in Kyoto in 1997, I hope to write a more adequate tribute. (DB)

Intensified continuity revisited

DB here:

We’re just beginning to understand the history of film forms, but some trends in Hollywood already seem clear. During the late 1910s American filmmakers synthesized an approach to cinematic storytelling that relied on continuity editing, the practice of breaking a scene into matched shots in order to highlight character action and reaction. In the years that followed, this editing strategy became the dominant approach to mass-market filmmaking across the world. Many historians and theorists believed that editing was the essence of cinema itself.

When sound arrived in the late 1920s, the technology was difficult to master and consumed a lot of production time. It would have been easy for American filmmakers to shoot every scene from a single position, but instead they used multiple cameras to cover the action, much as three-camera TV handles sitcoms now. This made filming cumbersome and limited the lighting choices, but filmmakers wanted to preserve the option of cutting to closer views and fresh angles as the scene developed. Continuity editing continued through the 1930s and well beyond, with filmmakers refining it in various ways.

The strategy has proven remarkably robust. Today’s mass-audience films, from all over the world, adhere to the principles and particulars of continuity editing. Not many artistic styles, in any medium, have had such a long run.

These ideas are developed in more detail in things that Kristin and I have written. (1) Most recently my book The Way Hollywood Tells It tries to track shorter-term changes in the continuity style. I found that one handy way to do this was to look at remakes. Remakes allow us to keep story factors somewhat constant and focus on differences in visual technique. Today’s blog looks at parallel scenes from two films, an original and a remake, in order to illustrate what I’ve called “intensified continuity”—the editing style that comes to dominate American films after 1960 or thereabouts.

Dear friend….

In Ernst Lubitsch’s wonderful Shop around the Corner (1940) Kralik (James Stewart) works in a Budapest gift shop with Klara (Margaret Sullivan). They quarrel constantly. But each has an anonymous pen pal, and the relationship is growing into love. Unfortunately, we learn early on, they’re writing to each other.

On the day they’ve agreed to meet face to face, Kralik is fired. He and another salesman Pirovitch (Felix Bressart) trudge to the café where Kralik is to meet his secret friend. Kralik can’t bear to face her now that he has no job, so he wants Pirovitch to deliver a note saying he can’t come. Still, his curiosity makes him ask Pirovitch to look in the window and describe her. Pirovitch tries to soften the blow, but he has to admit that the young woman waiting with a copy of Anna Karenina and a red carnation is Klara.

Angry, Kralik takes back the note and decides to let her wait. But after Pirovitch is gone, he returns to the café and meets her—not divulging his identity, but trying some conciliatory moves.

In the silent era, Lubitsch was one of the greatest exponents of continuity editing. You need only look at The Marriage Circle or Lady Windermere’s Fan to see his quiet virtuosity. (Kristin’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood devotes a chapter to his cutting.) But in Shop around the Corner Lubitsch uses only two shots to present Kralik’s and Pirovitch’s conversation outside the café. A fairly distant tracking shot follows the two men to the window, then we get a very lengthy shot of the two men outside. It starts with Kralik instructing Pirovitch to check on what his correspondent looks like.

Another director would have given us point-of-view shots showing what Pirovitch sees, along with his reactions. Instead, Lubitsch keeps the emphasis on Kralik, who’s responding to Pirovitch’s reports. Consequently, Kralik’s reactions aren’t given in cut-in close-ups but rather in the prolonged two shot.

This allows both performers to act with their bodies. Bessart’s shoulders relax, for instance, when he spots Klara, as if he’s slightly recoiling. Stewart’s reactions are more varied; he leans forward eagerly and nods as Pirovitch finds the woman. He slumps, then tugs his hat when Pirovitch mentions Klara.

Kralik looks in to see for himself, and collapses a bit. He eventually relaxes when he wryly accepts the fact that his pen pal is his quarrelsome coworker.

Visually, it’s a simple scene, but it shows the power of the unvarnished two-shot.

After the two men separate, Lubitsch shifts the scene inside and gives us another sustained shot as the anxious Klara talks with a waiter. Instead of crosscutting to Kralik returning outside, Lubitsch creates a humorous shot by letting his head drift into the window behind Klara.

When Kralik goes in to meet Klara, he doesn’t tell her that he’s her pen pal, so narrationally speaking, the knowledge is unbalanced. He and we know more than Klara does, which makes her unhappiness more pathetic. It’s a wonderfully textured scene, partly because we know that each one’s annoyance with the other masks disappointment and anxiety. As the action develops, there’s somewhat more cutting, but even Lubitsch’s closer views often keep both in the frame. He saves his closest shots for the most intense exchange, when Klara mockingly refuses Kralik’s efforts at friendship. The scene will end on a painful note, with each wounding the other with hurtful remarks.

AOL buddies

As you probably know, The Shop around the Corner was remade as You’ve Got Mail. There are some important story differences. The two protagonists have other partners, and Joe Fox owns a bookstore chain that is crushing the children’s bookstore owned by Kathleen Kelly (Meg Ryan). But the parallel scene in You’ve Got Mail is remarkably similar to the one we’ve just been examining.

The sequence starts with Joe and his assistant Kevin (Dave Chappelle) approaching the coffee shop, and Joe is apprehensive—not because like Kralik he’s out of a job but because of the upheaval that meeting his email correspondent could cause in his personal life. Like Kralik, he asks his friend to peer in the window to check her out.

But Nora Ephron handles the scene quite differently than Lubitsch did. She breaks all the dialogue into several shots, mostly favoring one actor (either over-the-shoulder shots or what are called singles). The process starts during the men’s approach to the café.

Once they arrive, the staging stations Joe at the foot of a flight of stairs and Kevin at the top, so a sustained two-shot isn’t really in the cards. The pattern is that Kevin reports what he sees, and in reaction shots we see Joe’s response.

When each man looks inside, unlike Lubitsch Ephron supplies point-of-view shots of Kathleen.

Joe reacts vindictively when he learns his email correspondent is his adversary, and he returns to punish her, but not before we’re taken inside the café and watch Kathleen wait for her correspondent. Even her encounter with another customer, somewhat similar to Klara’s chat with the waiter, is broken into three shots.

When Joe arrives, his conversation with Kathleen is handled in variations of shot-reverse shot, often in fairly tight framings. Again, the closer framings accentuate the bitter insults the characters exchange.

You’ve got cutting

Both scenes run almost exactly the same length: 8:48 in Shop, 8:42 in You’ve Got. But the initial portion, showing the two men on the sidewalk, consumes only two shots in the Lubitsch and 41 shots in the Ephron. That means that Lubitsch’s average shot in the scene runs about 82 seconds, while Ephron’s runs about 4.1 seconds!

The same disparity arises in the section of the scene taking place in the café. In Shop, 14 shots treat the action inside, but in You’ve Got there are 84! Lubitsch’s shots in this portion average about 21 seconds, still very lengthy, while Ephron’s are almost exactly the same as in the earlier portion, coming in at 4.3 seconds. We tend to think that only high-octane action sequences are cut quickly, but today’s dialogue scenes are cut fast too.

In both films, actors’ line readings are very important, but in Shop, the performances include sustained passages of body language. In You’ve Got, actors act mostly with their faces. Whereas Ephron gives us singles from the start (Kevin and Joe’s approach), Lubitsch saves his close shots for the encounter between his squabbling romantic couple. There’s an effect of gradation, with the cutting building the scene visually toward a high point, that isn’t provided by Ephron.

Oddly, the modern film is less subtle than the older one. Lubitsch uses no nondiegetic music in the scene, but Ephron inserts conventionally comic music as Kevin and Joe approach and we get sorrowful music when Kathleen leaves the café in tears. Although many people think that old movies are hammy and overplayed, here it’s just the opposite. Stewart performs subtly, but Hanks, whom many take as today’s Jimmy Stewart, plays broadly, gesturing in extremis and at one point shaking the brownstone’s railing. The Lubitsch scene also makes use of dramatic pauses to a greater extent than Ephron does.

The redundancy is seen as well in Ephron’s reliance on cutting and singles. Nearly every line or reaction in the You’ve Got sequence gets a shot to itself. This isn’t unique to this film; every remake I’ve examined is cut faster than its original. Fast cutting, down to 2 or 3 seconds per shot on average, and a reliance on OTS’s and singles typify today’s intensified brand of continuity.

Silent films were cut quite fast—in America, around five seconds per shot was common—but the arrival of sound slowed down the editing pace. The good people at Cinemetrics are building a database tracking this trend, among others. But since the 1960s, things picked up in American cinema, and today it isn’t uncommon to find films with average shot lengths of 2-4 seconds….and not just action movies. Likewise, such cutting operates in conversation scenes, making it more likely that the shots are singles rather than two-shots or ensemble framings.

This “intensification” of traditional continuity tactics, I’d argue, dominates mainstream moviemaking today, and not just in the US. Such cutting can sometimes be found in the 1930s and 1940s too, but then it was one possibility within a broader range. The Lubitsch example adheres to the principles of continuity editing, but it allows for more variety of camera distance and pacing.

I don’t denounce intensified continuity as such; some films, most recently David Fincher’s fine Zodiac, make intelligent use of it. Still, with this as the dominant approach, the director’s range of choice has narrowed. When contemporary directors lengthen a take, it’s usually to create a virtuoso traveling shot. A simple framing like the one outside the cafe in Shop is very unusual nowadays. The sustained two shot is practically an endangered species.

Why? What led to these changes between the studio era and contemporary cinema? A cynic would say that, contrary to Steven Johnson, audiences have gotten dumber and need more emphasis on character action and reaction to follow what’s going on. But in The Way Hollywood Tells It I suggest that there are many factors at work in this stylistic change. The book also provides more details of other techniques characteristic of today’s intensified continuity.

(1) In particular Kristin’s Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis, our sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (written with Janet Staiger), and our Film Art: An Introduction.

Charlie, meet Kentaro

DB here:

Echoing an earlier virtual roundtable on this blog, I want to write about my two favorite B film series, now available in handsome DVD boxed sets. Both series were mounted at 20th Century-Fox, both were adapted from genre fiction, and both seem very much of their time: lots of exotic Orientalia, and probably too many middle-aged men in tiny mustaches and broad fedoras. But to my mind these films offer brisk, unpretentious entertainment, solidly crafted and surprisingly subtle. They also allow us to trace some changes in the ways movies were made across the 1930s.

There’s another reason for this blog. Tim Onosko, a friend of Kristin’s and mine, recently died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Tim was an extraordinary figure, as you can find here. He was central to Madison film culture for forty years, and in his various creative activities, he shaped everything from The Velvet Light Trap to Tokyo Disneyland. He and his wife Beth also made a documentary, Lost Vegas: The Lounge Era. Tim and I enjoyed talking about the two series I’ll be mentioning. He loved these films, as he loved all films and popular culture generally, with a sharp-eyed dedication. So this is a small effort at an homage to Tim.

The Hawaiian and the Japanese

Charlie Chan, a Hawaiian police inspector of Chinese ancestry, became famous in a series of six novels by Earl Derr Biggers, from The House without a Key (1925) to The Keeper of the Keys (1932). Chan novels were brought to the screen at the end of the 1920s by Pathé and Universal, but for Behind That Curtain (1929) Fox took over the franchise. Warner Oland, a Swedish-born actor who had often played Asians, settled into the lead role in Charlie Chan Carries On (1931). He played Chan up through Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo (1937), then fled Hollywood under peculiar circumstances and went to Sweden, where he died soon afterward.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Each series echoed its mate. Tim claimed that in an early Chan, a character is reading a Moto story in the Saturday Evening Post, though I’ve never found that scene. When Charlie’s Number One Son turns up to help Moto in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938) it’s revealed that Charlie and Moto are old friends. There’s a more elegiac moment in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) when a theatre displays a poster for the Chan series—perhaps as well serving as an homage to the recently deceased Warner Oland. Despite Oland’s death, the Chan series continued until 1949, with Sidney Toler in the role, but with Lorre’s departure the Moto films ceased.

Having a Caucasian actor play an Asian protagonist was common at the time. Today, it seems condescending or worse, but we should recognize that the films featured Asian actors as well, often in significant roles. The most visible example is Keye Luke as Charlie’s highly Americanized son. Forever blurting out “Gosh, Pop!” Luke is a lively and likable presence.

Just as important, the portrayal of the detectives is remarkably free of racism. Charlie and Moto are clearly the quickest-witted characters, and both prove resourceful in all kinds of ways. Moto’s judo subdues thugs twice his size, and Charlie is up-to-date in the new technologies of detection.

The scripts go out of their way to show both men skilfully handling the prejudice they encounter. In Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936), a blatantly racist cop (William Demarest) who calls Charlie “Chop Suey” is mocked incessantly by everyone, most gently by Charlie. Moto excels at pretending to be the stereotypical Asian (“Ah, so!” “Suiting you?”). And both our protagonists are sympathetic to others who are in minorities. Charlie is notably unwilling to participate in guying black servants as the whites do, and Charlie Chan at the Circus (1936) shows his keen sympathy with the “freaks,” treating them with quiet courtesy. The Moto series presents a Japanese who doesn’t seem to share his country’s goal of ruling Asia. In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he enjoys a respectful friendship with a Chinese family of declining fortunes.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

Looks and looking

We can learn a lot by studying the two main actors’ performance styles. The plump Oland plays Chan as stolid but not ponderous. He floats across a room and gravely circulates among suspects, giving the films their deliberate pacing. Oland’s drawn-out delivery and pauses were due, people say, to his acute alcoholism, but he never seems to be struggling to find his lines. Charlie is at pains to be unobtrusive, modest, and tactful; his characteristic gesture is a simple one, letting the fingertips of one hand grasp one finger of the other.

He is a loving father, doting on his many children (all in tow in Charlie Chan at the Circus). Although Number One Son may exasperate him, you would go far in films to find as warm a portrayal of a father’s affectionate efforts to curb an impulsive boy. See Charlie Chan at the Olympics (1937) for the casual byplay between Charlie and Lee, now an art major and a member of the swimming team. Lee’s bubbling energy gives Charlie’s imperturbability even greater gravitas.

The short and slim Lorre plays Moto as a suave man-about-Asia, hand thrust casually into his trouser pocket. Moto is an art connoisseur, a graduate of Stanford (class of ‘21), and a master of many languages. Lorre, so easily caricatured at the time and now, hit on a brilliant idea: He didn’t give Moto stereotyped tricks of pronunciation. Unlike Oland, he didn’t usually drop articles or compress syntax.(2) Lorre just played the part in his lightly accented English, as he would in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. He added a soft-spoken delivery, a modest smile, and a trick he may have picked up from Marlene Dietrich–ending his sentences with a slight upward inflection, turning every statement into a polite question.

Reaction shots of suspects are a convention of these movies, but after several cuts show us everybody looking shifty, the reverse shots of our heroes show us that they miss none of this byplay. (3) Charlie is alert, but he hides his penetrating view behind a bland courtesy. As Moto, Lorre presents a more aggressive intelligence. Peering through round spectacles, those bug eyes, panic-stricken in M, can now become pensive or bore into a suspect. Charlie needs the force of law, but Moto, who usually acts alone, is dangerous by himself, and Lorre’s horror-show pedigree serves him well in giving his hero’s stare a sinister edge.

Listening and looking

You can argue that Oland and Lorre, coming to their parts only a few years after sound had arrived, helped Hollywood develop a wider array of acting styles. We historians of Hollywood have rightly praised gabby comedies like Twentieth Century (1934) and It Happened One Night (1934) for finding a performance technique suited to sound films, particularly in the wake of technical improvements in acoustic recording. If movies had to talk, we think, they should really talk, fast and hard and heedlessly. In this church our Book of Revelations is His Girl Friday (1940).

Lorre and Oland, like Karloff and Lugosi, remind us of the virtues of being gentle, spacious, and deliberate. This isn’t a reversion to those hesitant, strangled mumblings of the earliest talkies. Rather, the movies’ plots surround our Asians with rapid-fire duels of cops and reporters, snapping out “Say!” and “Hiya, sister!” and “Watch it, wise guy!” and “Don’t be a sap!” Against clattering percussion Moto and Charlie deliver a melodic purr.

Some people still believe that in Citizen Kane Welles and Gregg Toland introduced American film to steep low angles, tight depth compositions, and noirish lighting. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I’ve argued that the Gothic, somewhat cartoonish look of Kane synthesized and amplified trends that were emerging during the 1930s. The Chan and Moto films are wonderful places to study these visual schemas.

E

E

In Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935, above), cinematographer Charles G. Clarke (whom Kristin and I interviewed for the Hollywood book) offers flashy depth and silhouette effects, and nearly all the Chan films have moments of clever staging. Charlie Chan at the Opera, above, is particularly engrossing, with its huge set (recycled from the A-picture Café Metropole, 1937). The same film, incidentally, contains scenes of a fictitious opera, Carnival, composed by Oscar Levant. This was an ambitious gesture for a B film and looks forward to Bernard Herrman’s Salammbo sequences of Kane.

The Motos are even more remarkable. You want wild angles? Venetian-blind shadows? Telltale reflections in eyeglasses? Swishing bead curtains? Twisted expressionist décor? You’ve come to the right place.

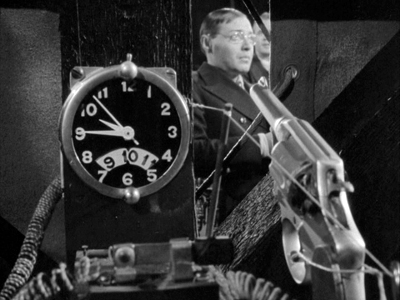

Some late thirties Fox sets seem to have been stored in Caligari’s Cabinet. Watching these films, it becomes clear that Kane applied the moody technique of crime and horror films to ambitious drama. One bold setup in Mr. Moto’s Gamble looks like a dry run for a Toland big-foreground composition (done here, as often in Kane, through special-effects). I like this shot so much I used it in Figures Traced in Light.

Yet all this creativity took place within severe constaints. These were B pictures, running under seventy minutes and shot in a month or so. Three or four would be released each year. They shamelessly used stock footage, leftover sets, and the same players in different roles from film to film. (Watch for Ray Milland, Ward Bond, and others on the way up.) The boys in the Fox cutting room seem to have enforced a remarkable uniformity: most of the Chans in these DVD sets, regardless of director, contain between 600 and 660 shots, while the faster-paced Motos average between four and six seconds per shot. The actors created hurdles too. Oland sank even further into drinking while the high-strung Lorre was addicted to morphine and periodically retired to sanitariums to recover. Those were the days; rehab wasn’t yet a matter for infotainment.

The Fox DVD boxes are model releases. The prints are well-restored (better on the second sets than the first) and filled with astute, informative supplements. We get a lot of detail about production matters, including why Oland left Hollywood. There is welcome biographical background on master minds like Sol Wurtzel and Norman Foster. I still want to know more about James Tinling, though; his direction of Mr. Moto’s Gamble and Charlie Chan in Shanghai (1935) belies his reputation as a hack.

“The cinema is not dangerous,” Moto reassures the Siamese tribesmen about to be filmed in Mr. Moto Takes a Chance (1938). Immediately, the woman who’s being filmed dies. The adventure begins. Who can resist movies like these? They have kept me happy since my childhood, when I watched them on Sunday afternoon TV. They can keep your children, and you, happy too.

For some good reading, see John Tuska, The Detective in Hollywood (Doubleday, 1978); Charles Mitchell, A Guide to Charlie Chan Films (Greenwood, 1999); Howard M. Berlin, The Complete Mr. Moto Film Phile: A Casebook (Wildside, 2005); and Stephen Youngkin, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre (University Press of Kentucky, 2005).

For more on Charlie, click here. Charles Mitchell has a nice wrapup on Kentaro here.

(1) The involvement of an innocent romantic couple was a convention of slick-magazine fiction of the day (both the Chan and Moto novels were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post), and it recurs throughout mainstream detective fiction of the 1930s. Most writers of the period wrestled with the problem of how to make the couple interesting. See Carter Dickson/ John Dickson Carr’s short story, “The House in Goblin Wood,” for a brilliant handling of the device.

(2) As many commentators have noted, Charlie doesn’t speak pidgin English; he seems to be mentally translating. Interestingly, the generation gap is apparent here too, since Number One Son speaks peppy and perfect American slang.

(3) One hyperclever moment in Mr. Moto’s Gamble gives us the usual rapid-fire array of single shots of discomfited suspects but neglects to show us the real culprit.