Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

The ten best films of … 1929

Lucky Star

Kristin here:

As 2019 fades away, it’s time once more to look back ninety years at some great classics. This series started somewhat by accident, when we wanted to celebrate the pivotal year 1917. That was when the stylistics of the Classical Hollywood filmmaking system, which had been slowly explored for several years, finally clicked into place and became the norm in the American studios.

After that, our series became a regular and surprisingly popular feature. The point is partly just to have some fun and partly to call attention to great films that have remained obscure and/or difficult to see.

For past entries, see: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, and 1928.

After the riches of the 1920s silent film, 1929 stands out as an anomalous year. The transition to sound was under way internationally, but different countries proceeded at different paces. The new technology often was not amenable to maintaining the freedom of cinematographic and editorial style achieved during the height of the silent cinema. There are arguably not as many indisputable masterpieces from this year as from previous ones–but there are some.

Oddly enough, truly major films from this year seem to have suffered a great deal from a lack of access, both in distribution of prints and release of good (or even any) copies on home-video formats. In part I want to draw attention to the shocking neglect of some great movies.

The list is dominated by Hollywood and especially the USSR, for opposite reasons. The American studios were well into sound production, and some of the top directors found tactics for using the new technique in imaginative ways.

In the USSR, on the other hand, silents reigned. Moreover, the great directors were not lured away to work in America, as so many European filmmakers were. (For example, Murnau’s career was nearly over, and he released no films in 1929.) Thanks to them, the golden age of silent cinema continued on.

A great year for the Soviet Montage movement

The General Line (aka Old and New, dir. Sergei Eisenstein)

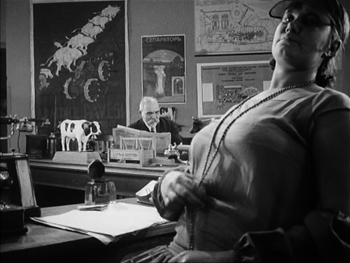

The General Line is probably the least of Eisenstein’s four silent features. The earlier films were all set before or on the very day of the 1917 Soviet Revolution, and they all have a vigor and a sense of political fervor that The General Line can’t quite match. Instead, it’s about policy, specifically the portion of the First Five-Year Plan devoted to the collectivization of private farms. Eisenstein adopts an odd tactic for dramatizing the need for such a drastic overhaul of life in the countryside. He presents a single protagonist for the first time, Marfa, a poor peasant working her land alone and without a horse for the plowing.

She becomes convinced that the answer to her and her neighbors’ plight is to create a cooperative dairy for the village. But throughout, Marfa has few allies and encounters opposition from both the local wealthy Kulaks and the poor peasants, who are portrayed as ignorant, greedy, and even violent in their determination to retain full ownership of their farms and livestock. Marfa is too weak to succeed without the support of the local government agronomist and a few like-minded farmers. The task of collectivization seems too overwhelmingly difficult to ever succeed.

In retrospect, we know about the systematic exile and execution of the Kulak class and the famines that resulted from government tactics over the coming decade. It is unpleasant to see Eisenstein, however unwittingly, providing propaganda for Stalinist policies.

Still, Eisenstein is Eisenstein, and The General Line is as formally daring as his earlier work. Apart from dramatic angles and rapid, jarring cutting, he experiments with extreme contrasts of elements within the frame by using depth compositions. These exploit wide-angle lenses and create impressive deep-focus images. In the shot above, Marfa is dwarfed by a pampered bull in the near foreground, and in a third plane beyond her we see the grotesquely fat Kulak lolling in the sun on his porch.

Other compositions create even greater contrasts. On the left, Eisenstein provides an image of bureaucratic indolence, official red-tape being a favorite (and apparently approved) satirical target for Soviet filmmakers. On the right frame, there’s a suggestion of the power of the collective’s new bull, who will sire a generation of calves.

Despite the grimness of the situation, Eisenstein manages to slip in an unusual amount of humor, and The General Line is quite entertaining.

The best DVD version I know of is the French one from Films sans frontiers, which is still available from Amazon France. The print in Flicker Alley’s “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film” is somewhat grayed out in comparison. Unfortunately this important set seems to be out of print. Flicker Alley rents The General Line online here.

New Babylon (dir. Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

This masterpiece by Kozintsev and Trauberg is all too little known. Information on the internet tends to come more often from musicologists, since Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the original musical accompaniment, rather than from film scholars. Many viewers have heard recordings of the score but not seen the film itself.

Kozintsev and Trauberg were the leading members of the FEKS (“Factory of the Eccentric Actor”) filmmaking group, based in Leningrad rather than Moscow. As the name suggests, the practitioners aimed not at realism, but at the grotesque, the comic, and the appeal of popular rather than high art.

New Babylon deals with the Paris Commune of 1871, a brief period when workers took over the French government. It was seen as a forerunner of the Soviet Revolution.

The title refers to a giant Parisian department store, which also seems to be in the business of putting on patriotic operettas about the current war with Germany. The store’s owner and patrons, as well as the performers in the operettas (see above) represent the bourgeoisie, while the workers who staff the store and create its products eventually rebel and run the doomed revolutionary government.

Again there is a heroine who represents the people, though she is unnamed, being known only as the shop assistant. She begins as a naive girl selling lacy clothing at the New Babylon and ends by becoming a militant revolutionary, standing atop a street barricade made up of the contents of the store–with the lace becoming bandages.

In keeping with its eccentric nature, the film mixes broad humor in the depiction of the bourgeoisie with grim tragedy as the defenders of the commune are shot in street fighting or tried and executed. The FEKS directors came from experimental theatre, but they also mastered the art of editing. New Babylon contains virtuoso sequences of crosscutting that sharpen the class struggle at the heart of the film.

New Babylon was restored in a joint venture by Dutch and German broadcasting channels and released, with the Shostakovich score, on DVD. There are Dutch and German versions, as Nieuw Babylon and Das neue Babylon respectively, which are out of print. We have the former. These retain the Russian intertitles, and, despite what the covers say, there are English and French optional subtitles as well as Dutch and German ones. (The booklet, however, is only in Dutch or German.) The quality is acceptable, but this film really needs a better restoration and Blu-ray release. It seems evident that the aspect ratio used in the current release crops the image to some extent.

Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov)

I need say little about this film, since it has been widely seen, praised, and discussed. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when many academic film scholars were obsessed with “self-reflexive,” or, less redundantly, “reflexive” films, Man with a Movie Camera was the great film. The result was, perhaps, that this admittedly very fine film was over-hyped. Nowadays it is as likely to be studied for the fact that Vertov’s wife, Elizaveta Svilova, created the very flashy Montage-style editing as it is for its reflexivity.

She is even seen doing so. At a number of points brief scenes of her examining, sorting, and splicing shots, which are subsequently seen in motion or in freeze-frames.

The film is a documentary, showing the filming, assemblage, and projection of a city symphony along the lines of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, of two years earlier. Vertov’s version sort of a day in the life of Moscow (and glimpses of other cities), also beginning with the city waking up and going to work. Here, however, we see cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman (Vertov’s brother), with his camera and tripod traveling around the city, climbing factory smokestacks, filming from moving cars, and so on. Although many shots are straightforward documentary images, others use special effects, such as split-screen in the opening shot on the right below.

The film is available (as The Man with the Movie Camera) in Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray of Vertov’s main surviving silent and early-sound films.

Arsenal (dir. Aleksandr [or Ukrainian, Oleksandr] Dovzhenko)

Ukrainian director Dovzhenko came somewhat late to the Montage movement, contributing Arsenal in 1929 and Earth in 1930. When I was in graduate school, these were classics that everyone saw, mainly because 16mm prints were circulating. Now I wonder how many students and cinephiles see them. The standard print that has been released on DVD by a number of companies is quite poor: dark, low-contrast, cropped (though not as badly as the End of St. Petersburg version I complained about in our 1927 list).

Arsenal begins with the return of Ukrainian troops from World War I, with an emphasis on the decimation and impoverishment of the rural countryside with the loss and mutilation of many farmers. Only well into the film are we introduced to Timosha, the stalwart young representative of the proletariat who weaves through the film but does not really become a conventional protagonist.

Dovzhenko has come to be viewed as the poet of the Montage movement, and many of the scenes, especially early on, are more grimly lyrical than part of a straightforward causal chain of events. There is also a touch of what we would now call “magical realism,” as in two scenes where horses speak to their masters. Dovzhenko also employs a wide range of Montage techniques: canted shots (as above); very rapid, rhythmic cutting; jump cuts; compositions with very low horizon lines (below); and so on.

Given the importance of Arsenal, it is a shame that the old copies have not been replaced by high-quality, restored DVDs and Blu-rays. The images here are taken from the best release I know of, Image Entertainment’s old DVD. I’ve boosted the brightness and contrast, but the result is still not ideal, and the DVD is long out of print. (It’s worth seeking out, since it has a commentary track by our friend and colleague Vance Kepley.) The best version I have found is on YouTube, using the Film Museum Wien print. It’s not cropped and has a brighter, less contrasty image (on the right in the comparison above); the subtitles are in French.

Hollywood on the verge

I presume that some readers will expect to see the two official classics of early sound Hollywood, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade and Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause. Probably in the days of Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957) these were some of the rare films from the period that could be seen. They also were by major directors. Looking at them again, though, I don’t feel that they’re up there with the films below.

The Love Parade has the problem of dire sexual politics, the point being that while wives are naturally subservient to their husbands, a man put in the same position is entitled to be upset. That’s what happens when a court official, played by Maurice Chevalier, marries the queen of the mythical kingdom of Sylvania, played by Jeanette Macdonald in her screen debut. Moreover, we’re expected to find humor in a comic subsidiary plot where the official’s valet does a courtship duet with a maid, slapping her around a bit and apparently sexually abusing her in some fashion offscreen. Beyond that, though, there is a gaping plot hole that undermines the whole thing. The official is portrayed as nothing but a serial seducer, and yet when Sylvania is in financial difficulties, overnight he comes up with a brilliant plan to solve everything. In addition, after seemingly obsessed with sexual matters, he becomes bored with his marital position as the queen’s boy toy.

Applause displays rather clumsy camera movements that gave it cinematic flair in an era of clunky camera booths. But it simply seems to me not a very good film otherwise. Thunderbolt effortlessly runs rings around it.

Thunderbolt (dir. Josef von Sternberg)

Decades ago, when I taught the basic survey film-history course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one could still rent Thunderbolt in 16mm. I showed it the week we studied the coming of sound. Returning to it now, I still think it’s the greatest early Hollywood talkie that I’ve seen. Here’s a film that came directly after von Sternberg’s string of silent masterpieces (not counting, unfortunately, the lost The Case of Lena Smith), and before one of his best-known works, The Blue Angel.

I’m baffled by the fact that it has never been available on DVD or Blu-ray. Fans share dreadful copies of the old VHS release or off-air recordings. Fortunately Turner Classic Movies aired it some years ago, and we have a watchable, if occasionally glitchy, homemade DVD.

The plot bears a vague resemblance to that of Underworld. A tough crime boss, nicknamed Thunderbolt (again played by George Bancroft), learns that his mistress is secretly seeing a young man and plans to marry him. The resemblance stops there, however. In an attempt to invade the young man’s apartment and murder him, Thunderbolt is finally caught and sentenced to death. Much of the rest of the film takes place in perhaps the strangest death-row prison ever portrayed on film.

Von Sternberg treats sound as a gift, not an obstacle. He cuts from cell to cell, all beautifully lit and composed, while offscreen a seemingly endless supply of singers and instrumentalists perform everything from “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” from a black soloist to a group of singers rendering barbershop-quartet style renditions like “Sweet Adeline” to a classical group that seems to be passing through. Sometimes we see the source of the music, sometimes we don’t. The music doesn’t seem to have much to do with the dramatic action but perhaps reflects the eccentricities of the warden–Tully Marshall chewing the scenery even more than usual.

Speaking of music, the film also includes an early scene with Thunderbolt and his mistress visiting a Harlem nightclub. The prolific black actress Theresa Harris, in her first known role, sings “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” Now that’s using early sound well.

Thunderbolt isn’t quite up to the level of Underworld or Docks of New York. Fay Wray and Richard Arlen make a blander couple than Evelyn Brent and Clive Brook in the former film. Still, it’s a major work in von Sternberg’s career. Let’s hope one of the DVD/Blu-ray companies finally makes it available.

Lucky Star (dir. Frank Borzage)

I well remember the astonishment and delight of the audience at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1990 when the previously lost Lucky Star was shown in that year’s Borzage retrospective. A print had recently been discovered at the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now the EYE Film Institute Nederlands).

Lucky Star was originally released in silent and part-talkie versions. The restored print was of the silent version, which was lucky indeed. Having seen how awkward and distracting the recently restored talking sequences in Paul Fejos’s Lonesome are, one can only cringe at the thought of similar scenes being inserted into Borzage’s lovely film.

Lucky Star again pairs Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, who had been firmly fixed as the ideal romantic couple by 7th Heaven and Street Angel.

There can be few, if any films of this period where the romantic leading man spends most of the narrative in a wheelchair. Tim has suffered a grievous injury fighting in World War I, and he and Mary, a young farm girl, fall in love. Mary’s mother insists that there’s no future with a disabled man and forces her to agree to marry a sleazy, bullying soldier. Such prejudice against a “cripple” is the main underlying theme of the film.

The development of the plot is surprisingly leisurely. The first half consists largely of Mary’s visits to Tim and his attempts to help her overcome some of the slovenliness and petty dishonesty stemming from her family’s extreme poverty. There is no real goal or conflict until the intrusion of the rival soldier about halfway through. The charm of the two characters and the actors playing them carry the action effortlessly.

As with 7th Heaven, the studio-built sets are remarkable, in this case representing entire houses set amid rolling woodlands. (See top.) The acting is splendid as well. Farrell in particular is quite convincing as a man who is paralyzed from the waist down. One remarkable shot lasting 2 minutes and 40 seconds has him struggling to leave his wheelchair and use crutches instead before finally falling into the foreground. The framing remains steady until a reframing downward at the end.

Lucky Star is one of the films included in the 2008 box, “Murnau, Borzage and Fox.” So far that invaluable set is still available. Otherwise one can find English and French DVDs of it as imports.

Hallelujah (dir. King Vidor)

For the first time, a mainstream director (Vidor was at the top of his game after enjoying a huge hit with The Big Parade in 1925) and MGM, one of the Majors of Hollywood, acknowledged that a gripping melodrama could be just as entertaining with an all-black cast as an all-white cast. That is, entertaining to those outside the deep South, where exhibitors refused to play the film, robbing it of its chance to become profitable.

Well established as a classic of both early sound cinema and African-American cinema, Hallelujah retains its entertaining quality. It is easy from a modern perspective to dismiss it as racist or dependent on stereotypes. But I think that put in the context of 1929, the film was as progressive as one could expect in the day.

Vidor had long cherished the project and gave up his salary to get a greenlight from MGM. The crew was racially mixed, including an assistant director, Harold Garrison, who was black. More importantly, the musical director, responsible for the many musical numbers, was Eva Jessye, the first widely successful black female choral conductor. A few years later she would participate in the premiere of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts, and alongside George Gershwin, she was musical director for Porgy and Bess.

Vidor shot the exteriors in the Memphis area, hiring local black preachers to consult on the religious scenes, including the river baptism. He accepted changes from his cast when they found their dialogue not ringing true. In short, he struggled to be as authentic as he could.

The casting was done with particular care. Zeke was originally to be played by Paul Robeson, the most respected black performer of the day, but he was unavailable. Instead Daniel L. Haynes, a notable stage actor, got the part through having understudied Robeson in the original production of Showboat. Haynes gives Zeke a buoyant appeal that maintains sympathy for him despite his vulnerability to temptation. Nina Mae McKinney, also coming from a stage career, did the same for the seductress Chick.

Hallelujah does not have the technical polish of a film like Thunderbolt, to a considerable extent because Vidor chose to shoot so much of it on location. The tracking shots during the opening number, “Oh, Cotton,” are certainly impressive for a 1929 film. There is also some impressive night shooting during Zeke’s chase after the escaping Chick.

Hallelujah is available on DVD from the Warner Brothers Archive Collection. Unfortunately the company has chosen to put a boilerplate warning at the beginning that essentially brands Hallelujah as a racist film:

The films you are about to see are a product of their time. They may reflect some of the prejudices that were common in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These depictions were wrong then and they are wrong today. These films are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed. While the following certainly does not represent Warner Bros.’ opinion in today’s society, these images certainly do accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.

I don’t think this description fits Hallelujah, but it certainly sets the viewer up to interpret the film as merely a regrettable document of a dark period of US history. Warner Bros. demeans the work of the filmmakers, including the African-American ones. The actors seem to have been proud of their accomplishment, as well they should be.

Sound and silence

Blackmail (dir. Alfred Hitchcock)

Long ago, when I first saw Blackmail, I thought it was a pretty mediocre, clumsy film. Luckily I have learned quite a bit about cinema since then and can appreciate Hitchcock’s clever use of sound–beyond just the famous “knife … knife … KNIFE” scene.

There’s the sequence where the blackmailer saunters into the tobacco store run by the heroine’s parents. He starts forcing her and her policeman boyfriend to pamper him with an expensive cigar and a good English breakfast. As he eats, he whistles “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” successfully annoying the boyfriend even further (above).

Earlier in this scene, Hitchcock presents a leisurely long take as the blackmailer performs an elaborate examination of said expensive cigar. His byplay generates suspense in us about whether he will get away with his tactic, as well as suspense in the father as to just when he is going to pay for that cigar.

The scene works well enough in the silent version of the film, but the little sound effects and muttered comments of the blackmailer make it a combination of tension and humor that wouldn’t come across without the sound. It also makes a nice contrast with the extended scene of the heroine in the artist’s studio. There the veiled threat of his seduction attempt and her naive reactions create a genuine suspense with no humor.

In contrast, there are passages of fast cutting that help avoid the stagey quality of much early sound cinema. The opening police raid and the later chase after the blackmailer through the British Museum’s Egyptian rooms (see bottom) both employ this tactic effectively.

By the way, I always thought that the giant pharaonic head in the shot where the blackmailer slides down a chain must have been a process shot, with a smaller head blow up for effect. Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray disc of the film, though, shows the label under the head well enough to reveal that it’s a cast of one of the giant heads of Rameses II from his temple at Abu Simbel (see bottom). Casts aren’t much in favor in most museums these days, so it’s no longer on display.

Pandora’s Box (dir. G. W. Pabst)

Fritz Lang, who has appeared quite regularly on these lists, released only The Woman in the Moon, his least interesting 1920s film, in 1929. Expressionism was over. In contrast, Pabst filled in with perhaps his most popular film, Pandora’s Box.

The film derives from a pair of Expressionist plays, Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, by Frank Wedekind. The first play had been filmed in 1923, as Erdgeist with Asta Nielsen as Lulu, and directed by Leopold Jessner in the Expressionist style. It survives but is among the most difficult Expressionist films to see. Pabst combined the second half of Earth Spirit and the entirety of Pandora’s Box for his version.

The play and film both depend on the central character being played by someone who can simultaneously Lulu’s conflicting traits: her vivacious joy in living, her strange mix of generosity and selfishness, her egalitarian attitude toward others, and her naive amorality. American star Louise Brooks was perfectly cast, as were the supporting roles, including veteran Expressionist actor Fritz Kortner as the wealthy publisher who is keeping Lulu as his mistress at the film’s beginning.

Although the source material would lend itself to Expressionist designs, Pabst went for a more modern, streamlined look, as in Lulu’s apartment (below) and the luxurious home of Dr. Schön.

Pandora’s Box was issued on DVD by The Criterion Collection but is now out of print. We can hope for a Blu-ray version.

Wild and tame surrealism

I’m dividing the tenth slot for two very different short films that were in their own ways experimental masterpieces that had a considerable lasting influence.

Un chien andalou (dir. Luis Buñuel)

Few if any trends in cinema have been so dominated by a single film. Surrealism was still a concentrated movement in the late 1920s, before it diffused out internationally to become a permanent option for experimental filmmaking. With Salvador Dalí as scriptwriter, Buñuel managed to create a loose narrative centered around displaying constant incongruous juxtapositions and inexplicable occurrences. It also aimed to offend, with the opening eye-slitting, the attempted rape, and the cavalier treatment of the clergy.

Un chien andalou, being short and in the public domain, is widely available online and on DVDs issued by small companies. I haven’t seen the BFI’s Blu-ray of L’Age d’or and Un chien andalou, but that would seem to be the best bet for quality.

The Skeleton Dance (dir. Walt Disney, animator Ub Iwerks)

The Skeleton Dance is a much tamer film than Un chien andalou, a humorous, entertaining treatment of the disturbing subject of death. (Nevertheless, it was reportedly banned in Denmark as being too macabre.) The subject was apparently suggested to Disney by composer Carl Stalling, whom the director approached to do music for two earlier Disney films. Stalling was interested in creating films based on musical themes, and The Skeleton Dance became the first of Disney’s “Silly Symphonies” series.

Stalling eventually moved on to Warner Bros.’s animation unit, where he composed the music for two series modeled on (and parodies of) the “Silly Symphonies”: the “Merry Melodies” and the “Looney Tunes.” Thus The Skeleton Dance helped inspire three of the great animated series of the 1930s and beyond.

The cartoon has only the loosest of plots, running (much as the “Night on Bald Mountain” episode in Fantasia would) through the eerie events of a night through to the calming effects of dawn. The opening features a frightened owl (below left) and a howling dog, but the main “characters” are four skeletons that leave their graves to dance and cavort. Iwerks showed off his virtuoso skill, with the complex figures of the skeletons moving in circles so that they crossed over each other, as in the circular dance in the image above. He also uses two basic techniques of animation, stretch and squash, to turn the rigid bones into lively, pliable figures (below right).

The Skeleton Dance is included in the “Walt Disney Treasures: Silly Symphonies” DVD set, now out of print.

Compilations of Carl Stalling’s brilliantly zany (and surrealistic) music for the “Merry Melodies” and “Looney Tunes” were released on CDs as “The Carl Stalling Project” Volume 1 and Volume 2. Remarkably and deservedly, these are still in print after many years. If you do not already own these, hasten to buy yourself a belated Christmas present.

Conclusion: Acknowledging two notable events

The year saw Buster Keaton, who has figured so prominently in these lists, make his final silent feature, Spite Marriage. A pleasant film, but one which does not reach the heights of his great comedies earlier in the decade. Second, the earliest surviving film of Yasujiro Ozu, Days of Youth, dates from 1929. Although not top-ten material, it already displays his unique style. Assuming we continue this annual list, it will not be long before Ozu begins appearing on it.

There’s an ongoing controversy over versions of New Babylon. Specialist Marek Pytel has noted that a number of scenes were cut from the film after its premiere, thus making the new version impossible to synchronize with Shostakovich’s score. The missing footage having been rediscovered, Pytel has constructed a new print and synced it with a piano version of the score. His website on the restoration of the original version is here. Ian McDonald has written an extensive series (in three parts, here, here, and here) analyzing in complex detail the evidence for and against Pytel’s claims. Among those is Pytel’s statement that Trauberg told him that the initial version is the one that he and Kozintsev would consider definitive, while at other times the director said that the edited version as released is the preferred one.

Pytel also has claimed that Kozintsev and Trauberg wanted the musical score to be recorded and added to the film; he argues that the film should be run at 24 fps and used that running time in the small number of live performances that have so far been the public’s only access to his version. The very low-resolution clip from Pytel’s version that he posted on Youtube, however, shows the action to be distinctly too fast at 24 fps. Perhaps Kozintsev and Trauberg would have accepted this faster action in exchange for a musical track, but it would have been quite distracting.

The standard version on the Dutch/German DVD seems to me to be running at the correct, slower speed, with the music reasonably well synced.

Whether or not the standard version is the preferred one, it has long been the one we have, and it is quite brilliant as it stands. Being episodic, it does not show signs of being incomplete, though obviously one would wish to see the extra footage in the Pytel version to be able to judge.

Our friend and colleague Ian Christie, noted historian of Russian and Soviet cinema, discusses the historical context of New Babylon in a short video essay.

Blackmail.

Not just a Christmas movie: DIE HARD on the big screen

Die Hard (1988).

DB here:

It’s been quite a fall season for UW–Madison film culture. There were visits from avant-garde legend Larry Gottheim, New York Times co-chief film critic Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston (Senior VP of Mastering at Disney), and Julia Reichert, whose American Factory is now routinely turning up on ten-best lists. The semester’s first screening at our Cinematheque was Kiril Mkhanosvsky’s Give Me Liberty, a Milwaukee movie also gracing year-end best lists. Our programs included restored films by African pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, retrospectives of Reichert and Kiarostami, a 3D double feature of Revenge of the Creature and Parasite (no, the other one), a program of early women directors in America, a selection of films conserved by the Chicago Film Society, and a miscellany ranging from Olivia and Near Dark to Tropical Malady and Red Rock West.

Travels to festivals, partly covered in our blog entries, forced us to miss too many of these shows. But we couldn’t miss the final one: Die Hard (1988).

It’s a film I’ve admired since I first saw it in summer of 1988. I’ve taught it in many classes, but never written about it. Seeing it again, in a pretty 35mm print from the Chicago Film Society, has made me want to say a few things as my final blog entry for this busy year.

The man between

Think-piece pundits like to say that Hollywood movies are about good guys versus bad guys. But usually things are more complicated. Very often the good guy is an outsider caught between two large-scale forces, good or bad or both–the cattle ranchers versus the townspeople, or the mob versus the cops. Often the protagonist is an outlier, forced to solve the problem using means that respectable social forces can’t.

Call it the problem of the House Democrats. When the lawbreaker can’t be brought to justice, how do you make him pay? The answer is one that William S. Hart movies provided in the 1910s. We need a “good bad man,” a rogue agent who knows the scheme from the inside but is willing to do the right thing. Which means that he has to be flawed too, a little or a lot, and that he can eventually reform.

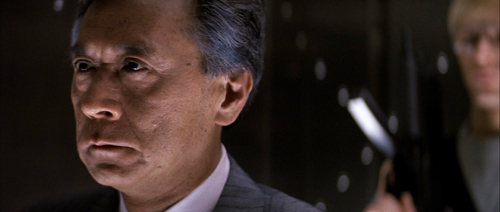

In Die Hard, the forces of law and order line up as the Los Angeles police and the FBI. The threat is Hans Gruber’s gang, posing as terrorists but actually planning to rob the Nakatomi Corporation of $640 million in bearer bonds and kill lots of hostages in the process. The naive TV broadcasters support both, recycling official scenarios of how hostage-taking works and reinforcing the gang’s masquerade as a terrorist group.

The contrasts are marked. The forces of order are American, in alliance with a Japanese company, while the attackers are Europeans. At the start, we hear American music (the rap played by the limo driver Argyle), but Hans hums Beethoven. The cops’ technology notably fails, as when the assault vehicle and a helicopter are consumed by firepower. But the gang’s hi-tech expert Theo can crack the vault, assisted by Hans’ plan to push the Feds to cut the building power.

Above all, the forces of social order are strikingly inept, while the gang is ruthlessly efficient. Unlike the police, who “run the terrorist playbook,” Hans boasts that he has left nothing to chance. The cops can’t imagine an adversary that exploits the official by-the-book procedures. As for the business types, Takagi’s calm bluff and Ellis’s freewheeling jargon can’t cope with a gang leader who doesn’t get the Art of the Deal.

Clearly, America and Japan need help. That appears in the form of John McClane, the cop from the East Coast trapped in Nakatomi Plaza.

McLane is the man between, spatially and strategically. He witnesses the action from inside the skyscraper, and bit by bit he figures out the gang’s real scenario. And he’s caught between both forces. The gang tries to find and kill him, while the cops refuse to recognize him as an ally. Confronting Karl’s brother early on teaches McClane that he can’t play by procedure. (“There are rules for policemen,” says a thug who doesn’t believe in rules.) The LAPD’s ineptitude shows that McClane can’t expect help on that front. So he must become almost as reckless as his adversary, though in a virtuous cause. This principally means blowing stuff up.

McClane isn’t totally without resources. He has as helpers Al, the desk cop who comes on the scene and sustains his morale, and Argyle, who’s there to play a crucial role at the climax. But mostly he’s alone in facing problems. He needs weapons. He needs shoes. He needs to protect the hostages, most of all his wife Holly, who has climbed up the corporate ladder. (In another movie, she would be the in-between protagonist.) To keep Holly from becoming a bargaining chip, McClane needs to hide his identity. And he needs to figure out the gang’s ultimate plan, of seeding the rooftop with explosives that will destroy the building and cover their escape.

John’s solutions are notably low-tech. While the police and the gang depend on advanced firepower and computer finagling, McClane lashes an explosive to a desk chair and uses a fire hose as a rope. He has to improvise shoes by taping a maxi-pad to a bleeding foot. No holster for your automatic? How about some Christmas wrapping tape? And don’t forget to taunt your adversaries with Yankee wisecracks.

In the course of this drama, the very physical McClane becomes a model for his allies. Holly punches the reporter who revealed John’s identity, and Argyle cold-cocks Theo at the point of getaway. Most dramatically Al kills the revived Karl when he’s about to plug McClane. The people in between take up arms.

McClane and his allies solve the House Democrats’ problem. Law can’t be lawless, even in protecting itself. Business, always aiming at the bottom line, has to give up principles. (“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks.”) These forces of social order are inefficient, trusting, and superficial. They can’t stand up to sheer brutal onslaught. In a crisis they will fold, or simply choose the nuclear option: agents Johnson and Johnson are ready to lose a big chunk of hostages.

McClane is a mediating figure that permits the film to show you can be strategically lawless for the sake of lawfulness. The fly in the ointment, the monkey in the wrench, screws up plans on both sides, but for the benefit of everyone else.

The Big Dumb Action Picture isn’t so dumb

This thick array of thematic parallels would be interesting in itself, but it gets worked out through precise storytelling. There was a time when critics knocked action movies as simply ragbag assortments of fights, chases, and explosions. Die Hard, I think, changed ideas of just how well-wrought an action picture could be. About 53 minutes of it consist of physical action (including people sneaking around), leaving almost 70 minutes for other stuff: suspense, changing goals, surprise information, attention to parallel plotlines, and little moments like the thief pilfering candy just before an ambush.

The film typifies tidy classical Hollywood construction, beginning with an arrival (the jet) and ending with a departure (the McClanes in a limo). In between we get a big dose of the classic double plotline, romance and work. Holly’s job at Nakatomi threatens their marriage, and John takes on a temp job, that of fighting the gang, which also endangers the couple’s efforts to reconcile.

For every Superman, there’s a Kryptonite, and here the protagonist’s flaws include his fear of heights (set up in the second shot, reiterated throughout) and, more importantly, his resistance to Holly’s independence. By the end, he’s learned a lesson. The film’s streak of male sentimentality allows John to ask his wife’s forgiveness for blocking her career ambition. She’s ready to compromise too, reassuming his last name when she meets Al. The characters we care about change, at least a little. That could be the motto of most classical Hollywood plots.

As usual, we get crosscutting among several lines of action. John’s arrival is crosscut with Holly at work fending off Ellis, and in the rest of the film the gang’s stratagems are intercut with the cops’ plans and McClane’s efforts. At various points, five or six actions are alternating with one another.

All these escalating situations cluster into distinct parts, the four that Kristin has argued for as typical of Hollywood architecture.

The Setup runs about 33 minutes, culminating in the murder of Takagi and Hans’s promise that he can open the vault.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup, coalesces around John’s goals of communicating with outsiders, avoiding capture, and attacking the thieves when he can. Through many chases and fights, the gang seeks to block all these efforts. The lines converge when John shoots Marco and tosses his body onto Al’s car. He gains the bag with the detonators, giving him the upper hand. Then the TV reporter gets involved, the cops arrive, and John is ordered to wait. Things seem to be stabilized.

After this midpoint, the Development supplies what Kristin calls “action, suspense, and delay.” Officer Dwayne Robinson arrives, pitting himself against Al and McClane. We can regard the police assault, Ellis’s clumsy attempt to broker a deal, and the arrival of the FBI men as a series of delays that endanger the stability of the standoff. At the end of this section, John meets Hans (posing as an escaped hostage): now both men know each other. And in the firefight that follows, John loses the detonators. Hans declares, “We’re back in business,” and the original plan can go forward.

The last twenty-five minutes constitute the Climax, launched by McClane’s “darkest moment.” He seems utterly beaten. Picking glass shards out of his feet, he gives Al a message for Holly over the CB radio. Al tells of his own burden, the accidental shooting of a child. The stakes are now very high.

Rapid crosscutting shows John finding the bombs on the roof and fighting with Karl, while the FBI helicopter attacks the building and Hans discovers that Holly is John’s wife. John stampedes the hostages down the stairs off the roof and escapes the strafing from the chopper before it blows. Argyle dispatches Theo, while John finds the surviving gang members in the atrium and shoots Hans, who falls to his death.

In the Epilogue, Al and John meet, Al dispatches Karl, Holly socks the newsman, and John and Holly drive off with Argyle.

These parts present a tight, logically building plot composed of swiftly changing situations. Along the way we encounter a great many motifs that create echoes or contrasts. Everyone notices the Rolex, at first a symbol of Holly’s talents but also of corporate swagger; only by unfastening it can they let Hans drop from the window. When Argyle floats the possibility that Holly will rush back into John’s arms for a movie ending, John murmurs: “I can live with that.” Agent Johnson speaks the same line, but for him it means an acceptable level of civilian casualties.

Holly’s unmarried name, Gennero, shows how a motif can develop in relation to the drama. At first it’s a sign of pride in her own identity (typical corporation, Nakatomi has misspelled it on the touch screen). Her name-change triggers the couple’s quarrel, but it has another narrative use: It conceals John’s identity from Hans. And at the end he introduces her to Al as Gennero but she reasserts her love by correcting him: “Holly McClane.”

Then there are differences of class and country. Hans reads Forbes, but McClane the US boomer references Roy Rogers and Jeopardy. (Hans is so unplugged from pop culture he thinks John Wayne was in High Noon.) Argyle the former cab driver and Al the cop know the downside of city life, but so does John the New York detective, who adapts Roy’s trademark phrase to the mean streets: “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker.”

Even a conventional Hollywood gesture, that of attacking a picture of a loved one, acquires a nifty plot function. Annoyed at John, Holly slaps down the family portrait on her shelf. Good thing too, because otherwise Hans would have seen it during the invasion. We’re reminded of that picture when in a moment of quiet John looks at the same snapshot in his wallet. Only after Hans has encountered John is he able to flip the portrait back up and realize that Holly is the “someone you do care about.”

There are lots more felicities like these–so many that I’d consider Die Hard a “hyperclassical film,” a movie that’s more classically constructed than it needs to be. It spills out all these links and echoes in a fever of virtuosity. Hard to believe that the makers started shooting without a finished script.

Intensified continuity, personalized

Die Hard is a good example of a stylistic approach I’ve called “intensified continuity.” It’s a modification of the classical method of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. Here director John McTiernan and DP Jan de Bont tweak that approach in distinctive and powerful ways. You can find examples all the way through the movie, but I’ll draw most of my illustrations from the first hour, when the stylistic premises get laid out for us.

Cutting speeds accelerated sharply in Hollywood films from the 1960s onward, and for its time, Die Hard was a rapidly-cut movie. The average shot runs just under five seconds, about what you’d get in a 1920s silent film. By today’s standards, which fall more in the 3-4 second range (even for movies outside the action genre), it’s a bit sedate.

One factor that increases the cutting pace is a greater reliance on singles and close-ups. These are tighter than we’d expect in most studio films of the classic era.

Even in close-up, the shots aren’t snipped free of their surroundings, thanks to the wide frame and layers of focus–both important in the film’s overall style, as we’ll see.

Likewise, intensified continuity exploits a greater range of lens lengths than we’d find in studio films of the classic era. We get wide-angle shots like those above along with telephoto shots throughout. Here the long lens is used to pile up people around Holly, and an even longer lens shows her optical viewpoint on the bandits in the office.

And there’s a free-roaming camera, thanks chiefly to Steadicam technology. But interestingly, Die Hard avoids some of today’s most common camera movements, such as shooting a fixed conversation with a sidewise or circular tracking shot. These would become more common in the 1990s.

McTiernan thought a lot about his camera movements, as he explains in interviews and the commentary track on the DVD. He wanted to shape spectators’ attention, to use camera movement to nudge things into view. “The audience’s eye wants to go with you.” Accordingly, more than in many contemporary films, Die Hard‘s camera movements have a shape: they end on a point of information.

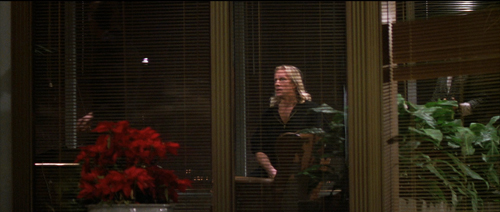

Sometimes it’s just a quick pan, doing duty for a cut. At other times, the reframing is a gentle nudge that prepares for a new scenic element, as when Holly enters her office.

In shooting Predator (1987), McTiernan wanted to cut moving shots together, but his editor resisted. For Die Hard, he refilmed his camera movements at different rates so that two would match. A good example is when Karl’s brother strides carefully into an area under construction. The camera tracks with him, but when he turns to find the source of a whining noise, the arcing movement at the end of one shot is picked up in the next as the framing circles to reveal the saw.

That reveal is given, characteristically, in rack focus. I could have added rack focus as another featured technique of intensified continuity. McTiernan and de Bont take it very far, making Die Hard one of the great rack-focus movies. The image is constantly shifting focus to guide our attention to the changing layers of the scene.

This neat, compact presentation not only preserves the commitment to long-lens close-ups we find in intensified continuity. The technique also gives each rack focus the snapping force of a cut. (And you don’t need to build big sets.) Needless to say, the rack-focusing wouldn’t work if McTiernan hadn’t committed himself to staging his action in depth. More on this below.

Staging in ‘Scope

Die Hard finds ingenious ways to “let the audience’s eye go with you” in the widescreen format. Sometimes it’s a matter of classic edge framing. Thanks to a low angle, John and Holly converse along a wide-angle diagonal.

Sometimes McTiernan reverts to a technique not enough directors use nowadays: blocking and revealing. In classic cinema that was usually a technique reserved for long shots, when actors could move aside as part of ensemble. Die Hard applies blocking and revealing to the tight framings of intensified continuity.

A thug in an elevator checks his weapon, pivots for an instant, and then moves aside to show the elevator arriving at the target floor.

Here again a rack focus helps. The moment reiterates the importance of the thirtieth floor in the skyscraper’s geography.

When Hans finds the body of Karl’s brother, we can study his expression. He flips the victim’s head to reveal a gunman, who looks to Hans before he says his line.

In a neat touch, the thug’s mouth isn’t shown. Today a director would probably show his whole face, but, really, who cares? The careful framing keeps him a secondary character, and a future target of McClane. And no need to rack focus on him, which would give him unwonted importance. All we need to remember him is that he’s the thug with long hair.

I can’t refrain from using one audacious example from late in the film. John and Hans have met, and Hans has revealed himself by targeting John with the pistol McClane has given him. In reverse shot, John reveals that it has no bullets and grabs it away from Hans.

But the pistol, and that gesture, have concealed the elevator behind them. When the pistol is knocked down, the elevator light pops on in the background. Our attention snaps to it, aided by that characteristic ping we hear throughout the movie (another motif).

The crisp turn of events, given visually and sonically, gets ampified by the acting. McClane’s cockiness turns to panic and Hans gets the upper hand. (“Think I’m fucking stupid, Hans?” Ping. “You vere saying?”)

The most bravura rack-focus comes during the climax, when the firehose reel whizzes down behind McClane and he realizes that he’s being dragged through the shattered window.

The coordination of the long lens, camera movement, staging, and racking focus is especially rich when Hans drifts among the hostages searching for the man in charge. He recites Takagi’s life history as he passes from one possibility to another (including, comically, Ellis).

At the climax of the passage, McTiernan’s staging-in-layers sets up Takagi, Karl, and Holly before Takagi takes charge. Briefly blocked by Hans, he admits his identity by stepping out from behind and into focus.

McTiernan isn’t done. A reverse shot of Hans finishing his spiel (“…and father of five”) punctuates the suspense. McTiernan buttons up this passage by returning to his “moving master” shot and having Karl shove Takagi out.

That clears the way for us to see Holly’s reaction. A beat dwells on her as she shifts her eyes to Hans, foreshadowing her conflict with him at the climax.

This sort of layering of faces popping in and out of visibility has precedents in earlier cinema, chiefly of the “tableau” period of the 1910s. McTiernan has, I think, spontaneously rediscovered for modern times what William C. de Mille was up to in the party scene in The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). (For more on that, go here.)

Of course McTiernan also has to work with the 2.35:1 anamorphic format, which enables him to spread his layers out more. That format also allows some remarkable compositions, such as the one surmounting today’s entry. The cut to the shot of John in Holly’s office uses the abstract splash painting (seen here for the first time) as a visual analogy for the explosion of gunfire offscreen at the same time.

McTiernan and de Bont constantly find striking but cogent images, thanks to lighting as well as color and format. Here’s McClane on top of an elevator peering through the perforated grille; his POV is a striking but still informative composition. the cut between the two provides a little punch of contrasting light and shade.

There are felicities like these feathered all through this remarkable movie, but the momentum of storytelling never flags. This remains a masterpiece of Hollywood filmmaking.

Thanks to our readers for following us this year. Kristin will be weighing in soon with her annual list of best films from ninety years ago. In the meantime, HO-HO-HO.

Madison owes an enormous debt to our Cinematheque team: programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Zach Zahos, as well as veteran projectionist Roch Gersbach. Santa should reward them. You can too by visiting the Cinematheque’s Podcast, Cinematalk. There you’ll find conversations with Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston, and James Runde.

For lots of background on the making of this film and the four sequels, there’s Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History by Ronald Mottram and David S. Cohen. At rogerebert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz has a discerning appreciation on the occasion of the film’s twenty-fifth anniversary.

Jake Tapper has provided the definitive analysis of Die Hard as a bona fide Christmas movie.

McTiernan (with whom I share an alma mater) provides very good DVD commentaries (even for Basic). Prison also seems to have given him some pronounced political views. Alas, the website he created as a platform for them is apparently no longer available. Word is that McTiernan is preparing a new film, Tau Ceti 4, with Uma Thurman. A videogame promo is purportedly signed by him.

Of other McTiernan films, I also much admire The Hunt for Red October (1990). The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) seems to me better directed than the original, and The 13th Warrior (1999), despite being taken out of his hands, remains a pretty interesting film. (Name another Hollywood movie in which a Muslim poet visiting Northern Europe is justly appalled at its barbarism.) Nomads (1986) also has its good points.

I discuss the issues of narrative and style raised here at greater length in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. You can also search “intensified continuity” for blog entries hereabouts. On CinemaScope aesthetics, see this entry and this video.

Die Hard (1988).

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

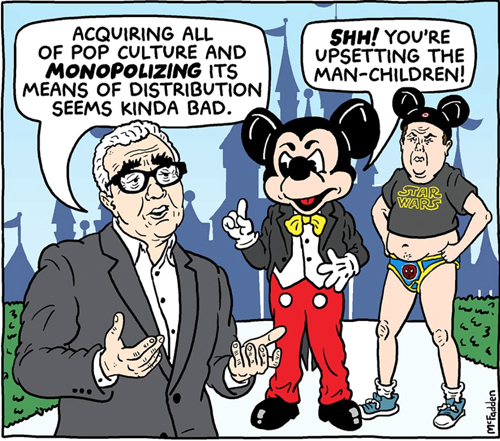

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

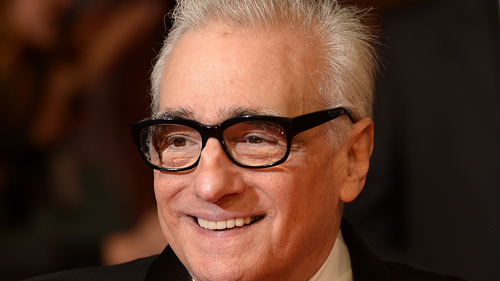

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

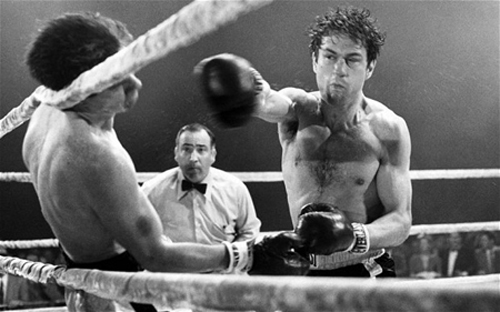

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

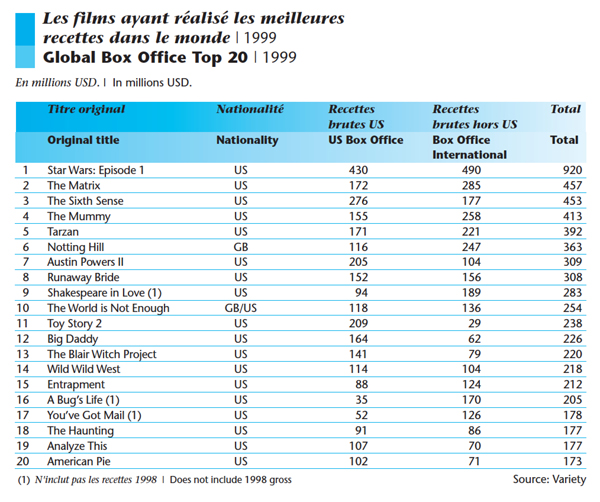

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

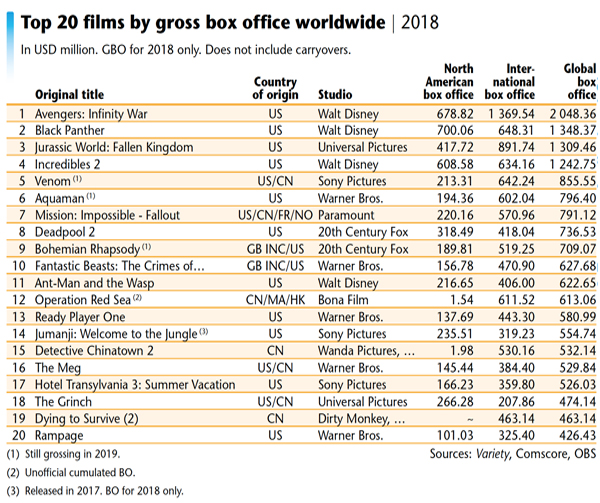

Now consider the 2018 situation.

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.