Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

When worlds collide: Mixing the show-biz tale with true crime in ONCE UPON A TIME . . . IN HOLLYWOOD

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Jeff Smith here:

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood might turn out to be the buzziest film of 2019. Some of this water-cooler talk is due to its unusual status within an ever-enlarging field of true crime stories. (Call it a “not quite true” crime story.) Indeed, the genre is hotter than ever thanks to a bevy of new podcasts, telefilms, and miniseries.

Industry analysts, though, are also keen to interpret Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office fortunes. As that rare big summer release that is neither a sequel nor a franchise title, it can be seen as a test of whether original content can survive amidst heavily marketed, presold tentpoles.

The lesson so far? To quote William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything.” In The Washington Post, one unnamed studio executive warned, “I don’t see any blue-sky meaning here.” The executive added, “This movie has assets that almost no other film has. That’s what drove it.” At least one of those assets is Tarantino himself, who is a brand, if not a franchise. Fans know what to expect in a Tarantino film, which is why the film is sui generis when it comes to this summer’s slate. Due to its unique IP, it can’t really be compared with films like Men in Black International or Spider-man: Far from Home. Yet thanks to Tarantino’s larger than life presence, it also isn’t Long Shot or Booksmart or Stuber.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is catnip to Tarantino nerds like me. It has the usual surfeit of references to obscure films and television shows. Some of these are deftly interwoven into the story itself. It boasts a carefully curated soundtrack that unearths “some-hits” wonders. It also contains scenes depicting nasty yet comical violence, a hallmark of Tarantino’s work ever since Reservoir Dogs.

At first blush, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would seem to be Tarantino’s most linear film. Yet it still displays certain continuities with his oeuvre in terms of story structure and technique. Although the film eschews the chapters and title cards found in Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, it still contains elements of what David calls “block construction.” In the case of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, it is all about threes. The plot is structured around three days in the winter and summer of 1969: February 8th, February 9th, and August 9th. Each “chapter” is introduced showing the date via superimposed text. And all three chunks of narrative crosscut among the activities of three actors – Sharon Tate, Rick Dalton, and Cliff Booth – as they try to adapt to changes in the film and television industries.

If all of this assures that you’d never mistake Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as the work of another director, other elements show Tarantino striking out in new directions. Chief among these is his mash-up of two normally distinct story types: the show-biz tale and the true crime yarn. Think of it as Singin’ in the Rain meets In Cold Blood. In what follows I outline some of the ways that Tarantino adapts his signature style to two well-established storytelling options: the multiple draft narrative and the network narrative. I also consider the effects Tarantino’s counterfactual history has on the conventions of the show-biz tale and the celebrity biopic.

My analysis contains major spoilers. If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, stop reading now!

My world and welcome to it

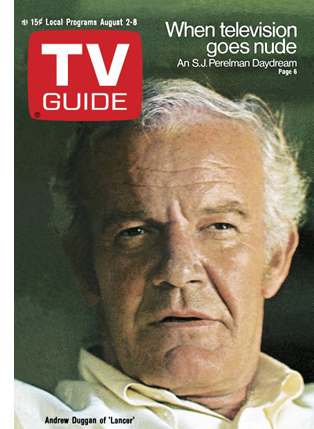

Quick trivia question: what actor was on the cover of TV Guide during the week that Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family? Sharp viewers of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should know the answer. We see Tate’s housemate, Woychiech Frykowski, reading that issue of the magazine as he watches Teenage Monster on late night television.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Tarantino’s film treats this little bit of pop culture ephemera as an uncanny coincidence. It simply becomes yet another way that he can intertwine the destinies of his three protagonists. But that brief shot got me thinking: did Tarantino start with the idea that he’d recreate whatever series was featured on TV Guide the week Tate was killed?

If so, Rick might have appeared just as easily as an aspiring cartoonist next to William Windom on the NBC sitcom, My World and Welcome to It. The show debuted just six weeks after Tate’s death. It is not unthinkable that NBC would have pushed for a cover on TV Guide in an effort to promote the premiere. Yet Tarantino’s counterfactual history in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would have been vastly different if that had been the case.

Did Tarantino really base his screenplay on this conceit? I doubt it. Lancer fits so snugly into the world that the director captures onscreen that it is not be so easily replaced. Tarantino seems to have a nostalgic fondness for the show, much as I did in my wasted youth. (I recall having a Lancer lunchbox at age six.) Production designer Barbara Ling describes the steps she took to recreate Lancer’s mix of Spanish/Western design. This involved adding adobe storefronts to the wooden ones, and substituting iron coils for wooden pegs on the saloon’s staircase. Ling added, “This was a [rich] cattle town and the buildings are two and three stories. It’s not Deadwood.”

Many critics have characterized Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as another hangout movie. This is Tarantino’s designation for a film that is leisurely paced, fairly light on plot, and mostly gives the audience a chance to spend time with the characters. Indeed, because of these qualities, reviewers often compare Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood to Jackie Brown, a film that Tarantino himself compared to Rio Bravo, which was Howard Hawks’ hangout movie.

The resemblances don’t stop there. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s three-headed protagonist bears certain similarities to Jackie Brown’s Jackie, Ordell, and Max.

Yet while watching Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I felt this film, more than any of Tarantino’s others, was an exercise in world-building. Normally we associate that term with sci-fi, fantasy, and comic book movies. It is especially important for transmedia properties where the fictional universe depicted exceeds the bounds of any individual film, television series, book, or video game.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is also an alternate history, a type of speculative fiction also common in sci-fi and comic book stories. The Avengers: End Game and Spider-man: Into the Spiderverse are both relatively recent examples. This suggests a loose affiliation between Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood and other blockbusters even as Tarantino tweaks that formula by situating his speculative fiction within the generic framework of true crime.

Tarantino largely avoids the industrial motivations behind these two narrative techniques commonly seen in tentpoles. Instead, he simply recreates the pop culture world of his youth. In doing so, the director’s real world, his “realer than real” universe, and his “movie movie” universe all collide.

Keepin’ it real (and realer)

As Tarantino has explained in interviews, the “realer than real” universe is an alternate reality close to our own where his fictional characters can intermingle with real people. The “movie movie” universe, on the other hand, is a more overtly fantastic world closer in spirit to comic books or exploitation films. The characters have unusual abilities or even supernatural powers. The “movie movie” thus downplays the realistic motivations usually found in the “realer than real.” In Tarantino’s oeuvre, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance exemplify the “realer than real.” Kill Bill and From Dusk to Dawn are instances of the “movie movie.”

Each universe features a web of connections that can link particular tales together. For example, Kill Bill’s Sheriff Earl McGraw and his son Edgar pop up in Death Proof. Similarly, Lee Donowitz, the cocaine-sniffing movie producer in True Romance, is purportedly the son of Sgt. Donny Donowitz, the “bear Jew” in Inglourious Basterds.

In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the most obvious references to these two Tarantino universes are the fictional brands he has created. During the end credits, we see Rick in a TV ad for Red Apple cigarettes. According to a Tarantino wiki, “ads or packs of these flavorful smokes” can be seen in The Hateful Eight, Inglourious Basterds, Planet Terror, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, From Dusk till Dawn, Four Rooms and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. (The latter is an obvious outlier. Yet the Red Apple nod was likely an in-joke related to Tarantino’s offscreen romance with Mira Sorvino, who played Romy.)

Similarly, Tarantino’s fictional fast food chain, Big Kahuna Burger, appears on a bus billboard in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. It previously was featured in a memorable scene in Pulp Fiction. (“That’s a tasty burger!”) But it had already debuted as a delicious snack devoured by Mr. Blonde in Reservoir Dogs. Big Kahuna later comes back in two other Tarantino films, From Dusk Till Dawn and Four Rooms, as well as Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.

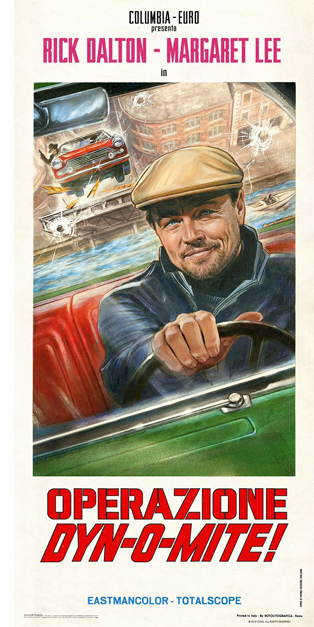

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Much of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes from the way Tarantino overlays these three universes to create a singular fictional world. For example, at one point we learn that Rick was considered for the role of Captain Virgil Hilts, the part played by Steve McQueen in John Sturges’ The Great Escape. Tarantino even inserts digitally altered footage of The Great Escape to show us a scene of Rick as Hilts. Since Rick claims he never met Sturges, this moment appears to represent an imagined version of the film that could exist in some type of alternate history. It invites us to consider how different Rick’s career might have been had fortune smiled upon him instead of McQueen.

To disentangle this knot, one must surmise that The Great Escape and Steve McQueen belong to both the real world and the “realer than real” world. Yet the scene of McQueen at the Playboy mansion and Rick describing his missed opportunity can only belong to the “realer than real.” And the character of Hilts himself exists only in the “movie movie” world. Hilts shares this status along with other characters Rick plays onscreen, such as Bounty Law’s Jake Cahill and The FBI’s Michael Murtaugh. After all, movie magic enables Cliff Booth to stand-in for Rick for scenes involving physical action. That two actors can play the same character within the same scene suggests that fictional personae in cinema have a unique ontological status quite different from the real world.

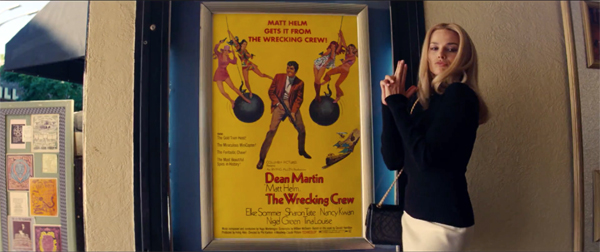

Arguably, the scene where Sharon Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew raises even more vexing issues about what is real and what is fictional. Unlike the clip from The Great Escape, the theatre screening shows the real Sharon Tate playing the character Freya in The Wrecking Crew. The fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate, along with the rest of the Bruin Theater’s audience. Yet, because Margot Robbie only pretends to be Sharon Tate for Tarantino’s camera, she doesn’t really watch herself playing the role. Obviously, Robbie belongs only to the real world. Yet Sharon Tate, as both an actual person and a fictional character, inhabits both the real world and the “realer than real world.”

Here the film indulges the Bazinian conceit that cinema has indexical properties. While making The Wrecking Crew, the film camera captured an imprint of the real Sharon Tate that preserved her being beyond the reaches of time and even death. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this moment is both joyful and sad. The viewer imagines the thrill that Tate feels in watching herself on the big screen, basking in the glow of incipient stardom. Yet the delight we experience is colored by our knowledge of what happened to the Sharon Tate seen falling on Dean Martin’s camera case. Unlike Robbie’s character, that Tate is doomed to a grisly death at the hands of psychopaths.

By film’s end, however, we are forced to reevaluate where Sharon Tate fits into Tarantino’s universe. When Cliff and Rick thwart the attack of Tex Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, and Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, both Sharon Tates appear to move solely to the realm of the “realer than real.” Like the fictional Sharon Tate played by Robbie, the actress who appeared in The Wrecking Crew also lives on in a parallel universe created by the forking of time. And the fate of that character remains completely undetermined. Now fully a part of the “realer than real,” Tarantino’s Sharon Tate might eventually snort cocaine with movie producer Lee Donowitz or bum a Red Apple cigarette from Pulp Fiction’s Mia Wallace.

Once she joins the “realer than real,” almost any fate you could imagine for Sharon Tate seems possible. And it is that sense of the actress’ unlimited horizons that gives the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its resonance. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time films always situated viewers in the realm of myth. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, on the other hand, evokes the fairy tale.

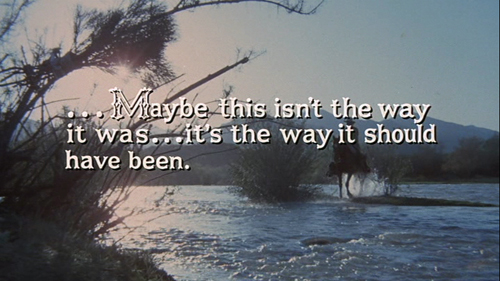

Tarantino is known for his experimentation with narrative, and the simplicity of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s “what-if” scenario could seem like a retreat from the formal play seen in his earlier films. Yet I’d argue that Tarantino’s merging of fact and fiction is even more audacious in certain respects. It strikes me as an unconventional example of what David calls “multiple draft narratives,” like Krzystof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance or Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gives us a second draft of history, albeit one where the key decision point is saved almost until the end of the film. And unlike Blind Chance or Sliding Doors, Tarantino doesn’t need to tell us what the different outcomes are for each of these tales. The first draft of history is one we already know.

In fact, the notion of multiple drafts offers a useful lens for all three films in Tarantino’s “counterfactual” trilogy. (The other two are Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained.) In Groundhog Day, Source Code, and Edge of Tomorrow, each iteration of the basic situation shows the protagonist inching toward his goals. They gradually progress to the point where they are able to alter destiny, either theirs or the world’s or both.

Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood all present images of history not as it was, but as it should have been. Such counterfactual histories run counter to the norms of speculative fictions that often present us with dystopian worlds we were lucky to avoid. (Think Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Robert Harris’ Fatherland, or Kevin Willmott’s “mockumentary” C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.) All of these stories depend upon our knowledge of the first draft of history. Yet Tarantino gives us second drafts that right particular historical wrongs in either small or large measure. In doing so, Tarantino gives us versions of history that are closer in spirit to his favorite movies. All three films in the “counterfactual” trilogy feature tidy resolutions. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, however, is even more self-conscious about the way Tarantino’s second draft of history takes the form of a “movie movie” climax. The realer-than-real version is the one we ought to prefer.

Paging Mr. Melcher, Mr. Terry Melcher…

If Tarantino’s conflation of fact and fiction evokes certain traits of the multiple-draft narrative, his vivid recreation of Hollywood circa 1969 illustrates another type of story popularized in American independent films and various art cinemas: the network narrative.

Tarantino has broached this form before in Inglourious Basterds. There he moves back and forth between three mostly independent storylines: 1) the Basterds’ guerrilla campaign against German soldiers, 2) Archie Hicox and Bridget von Hammersmarck’s initiation of Operation Kino, and 3) Shosanna’s plan to avenge her family’s deaths during the premiere of Nation’s Pride. SS officer Colonel Hans Landa threads through all three storylines. He orders the killing of Shosanna’s family in the opening scene. Later he shares apple streudel with Shosanna in a Paris café. Landa also investigates the scene where Hicox has been killed. In the climax, he interrogates Bridget in a scene that contains a grim allusion to Cinderella’s lost slipper.

Finally, Landa negotiates a deal with Aldo Raine’s superiors that guarantees his immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is obviously much less plot-driven than Inglourious Basterds. Yet, as noted above, it shares a similarity in the way it interweaves the stories of three characters: Rick, Cliff, and Sharon.

It’s frequently said that Hollywood is a company town. By situating all three characters within the film and television industries, Tarantino tacitly stays faithful to that truism. The protagonists’ shared profession also facilitates the kinds of attenuated links between stories commonly found in network narratives.

Part of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes in recognizing the “six degrees of separation” that join all of these people, both real and fictional, in the same entertainment ecosphere. Take, for instance, one decidedly minor character: actress and singer Connie Stevens, played by Dreama Walker. At the Playboy Mansion party, Stevens listens to Steve McQueen explain the romantic triangle that has Sharon living with her current husband, Roman Polanski, and her ex-boyfriend, Jay Sebring. Stevens, though, is the ex-wife of actor James Stacy, who played Johnny Madrid in Lancer. Stacy (played in our film by Timothy Olyphant) is Rick Dalton’s scene partner for the episode of Lancer that Dalton hopes can spur his comeback. Dalton is Sharon Tate’s neighbor on Cielo Drive, the same house that Charles Manson targets as the site of the “family’s” first murder. This circuit even loops back on itself. When Stacy and Dalton first meet on set, Stacy asks Rick whether it was true that he almost got a part in The Great Escape, the same part played by McQueen.

Two characters in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood serve as nodes that connect all three storylines together. The first is Cliff, Rick’s stunt man and gofer. Although not a resident at Cielo Drive, he spends a lot of time in Rick’s home and thus is privy to what happens in Sharon’s abode. This is especially evident when Cliff repairs Rick’s fallen TV antenna. The camera is aligned with him as he overhears Sharon playing a Paul Revere and the Raiders album. He also notices Charles Manson approaching the Polanski residence. Tarantino’s casting of Damon Herriman as Manson is likely an allusion to the television show, Justified. Herriman played Dewey Crowe alongside Olyphant.

Justified was also an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s “Raylan Givens” books. Tarantino has long admired Leonard’s work as a writer of both westerns and crime novels.

Employing a redundancy that befits Hollywood storytelling, Cliff gets linked to Sharon’s storyline in other ways. While working as Rick’s stunt man for an episode of The Green Hornet, he gets involved in a dust-up with Bruce Lee. Lee gave Sharon Tate some pointers on fighting as she prepared for her role in The Wrecking Crew. And in real life, the martial arts legend was recommended for the role of Kato on television’s The Green Hornet by Sebring, Tate’s former boyfriend.

Perhaps Cliff’s most important role in the film’s network involves his dalliance with Pussycat, one of the many young women who viewed Manson as a kind of guru. Cliff picks up Pussycat as a hitchhiker and gives her a ride back to the Spahn ranch. Having worked on the ranch back when it was an active production site, Cliff grows concerned for the safety of its owner, George Spahn. Cliff notices how the Manson clan has taken over and is troubled by its weird vibe. Determined to see George for himself, Cliff forces his way into George’s house over the objections of the Manson girls, especially Squeaky. George seems careworn, but Cliff finds that there is little he can do for him.

When Cliff sees a pocketknife sticking out of his front tire, he confronts Clem, one of Manson’s followers. The conflict becomes physical. Cliff breaks Clem’s nose with one punch and then proceeds to beat him to a bloody pulp.

This proves to be a dangling cause that gets resolved in the film’s climax when Cliff recognizes Tex, Sadie, and Katie as people he met at the Spahn ranch.

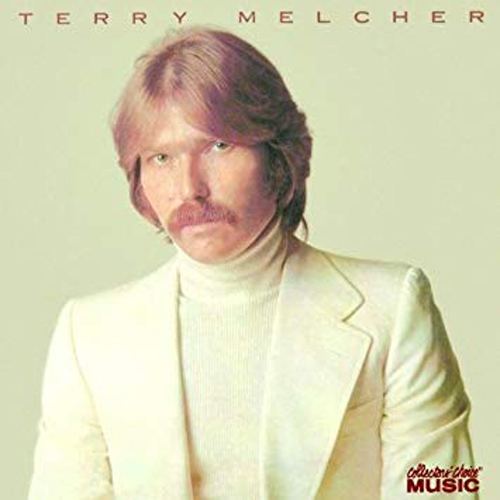

The other character who links the storylines together is one we never see: record producer Terry Melcher. Melcher is the “Terry” that Manson mentions when he visits Cielo Drive in the scene described above. Later, Tex reminds Sadie, Katie, and Linda that Charlie directed them to go to the place where Terry Melcher lived and kill everyone inside.

Although these are the only explicit references to Melcher, he is indirectly represented in several other aspects of the film. Here it helps to know a little about Melcher’s career and Manson lore. Even if Melcher’s name draws a blank, you likely know many of the bands he worked with: the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.

All these musicians crop up in one way or another in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Melcher’s last major credit of the 1960s was as producer of the Byrds’ Ballad of Easy Rider. When Rick berates Tex for parking his car on Cielo Drive, he yells, “Hey, Dennis Hopper! Move this fucking piece of shit!” Rick’s insult fits with his general disdain for hippies. But it also alludes to Easy Rider by comparing Tex’s look to that of Hopper’s character, Billy.

Two of the Mamas and the Papas – Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot – both appear in the party scene at the Playboy mansion.

We also hear the Mama and the Papas’ big hit, “California Dreaming” in a cover version by Puerto Rican singer José Feliciano. And when the car driven by Tex crawls up Cielo Drive, the music issuing from the Polanski residence is the Mamas and the Papas’ “12:30: Young Girls are Coming to the Canyon.” Even before Tex’s directive to the Manson girls, Tarantino has given us a subtle reminder that Melcher was Charlie’s intended, if indirect, target.

Finally, Sharon plays Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Good Thing” and “Hungry” on a hi-fi in her bedroom.

The choice of music is especially fitting since the band’s lead singer, Mark Lindsay, lived in the same house on Cielo Drive with Melcher and his then girlfriend, Candice Bergen.

Beyond these musical references, Melcher’s history with Manson informs Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in another way. Melcher recorded some demos of Manson’s songs, and even discussed making a documentary about Manson’s commune at the Spahn Ranch. In testimony at trial, Melcher said that any possibility of a record contract with Manson was sundered when Charlie asserted that he’d never join a musicians’ union. Manson’s staunch refusal was rooted in his desire to avoid entanglements with the establishment. Yet union membership was a condition for any contract with Melcher’s label, Columbia records. Another factor in Melcher’s decision was his assessment of Manson’s talent. Charlie couldn’t sing.

Although Melcher publicly stated that he only considered Manson’s musicianship, he privately expressed concerns about Charlie’s mental stability. These were heightened when he visited the Spahn Ranch and witnessed Manson in a physical altercation with a drunken stunt man. Tarantino more or less recreates this episode in his film, substituting Cliff for the unnamed stunt man and the hapless Clem for Charles Manson.

More importantly, Melcher is the son of screen legend Doris Day and stepson of agent/manager/producer Martin Melcher. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, he becomes the ideal, if absent, symbol of the combined worlds of music, television, and film that Tarantino so lovingly details.

How the West was lost

Los Angeles circa 1969 is presented as the epicenter of the American entertainment industries. It’s a place where a hairdresser like Jay Sebring rubs shoulders with action stars, TV cowboys, ingénues, film directors, and pop stars –and make $1000 a day to boot! The constant stream of hits from KHJ radio is as ubiquitous as the many movie posters, billboards, and theater marquees that feature Hollywood’s latest and greatest.

Tarantino’s press kit for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood makes reference to Joan Didion’s famous observation in “The White Album” that “the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community.” Most critics take Didion’s reference to the Sixties as shorthand for the end of the “peace and love generation.” Yet Tarantino’s slightly revisionist take suggests it’s not only the youthquake that died, but also a certain strain of Hollywood filmmaking that passed with it.

Although I don’t doubt their historical accuracy, the litany of titles that appear throughout Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels as curated as any of Tarantino’s music soundtracks. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, are films that entered the canon of great sixties cinema. Others, like The Night They Raided Minsky’s, are early films by directors who’d later achieve greatness. (In this case, William Friedkin, who won an Oscar in 1972 for The French Connection.)

But many, like Lady in Cement, Tora, Tora, Tora!, Krakatoa: East of Java, Mackenna’s Gold, C.C.& Company, and even The Wrecking Crew, are largely forgettable movies.

Tarantino clearly has affection for all of the drive-in theaters and Hollywood picture palaces where these titles played. But the titles themselves are evidence of the industry’s struggle to adapt to new tastes and a rapidly changing media landscape. Old-school show biz types, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, continued their success as singers and television personalities. But their careers as actors had functionally ended by 1969. And the efforts to keep them relevant often seemed either strikingly anachronistic or just plain weird.

In the opening scene of Lady in Cement, Frank Sinatra fights off a small school of sharks while he is examining the body of a nude woman who, like Luca Brazzi, sleeps with the fishes. And yes, the scene is as ludicrous as it sounds. If this is what became of Hollywood’s once great tradition, it is hard not to think we should just let it pass.

Yet, the fear of obsolescence also explains the oversize role that Tarantino gives to the Western as part of this changing landscape. True Grit and The Wild Bunch were among the summer of 1969’s biggest hits. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would eventually become the year’s top-grossing film. All three Westerns feature cowboy heroes that are either aging, outmoded, or both. They reminded contemporary viewers that horse riders would soon yield to horseless carriages, the lone bounty hunter would soon be supplanted by paramilitary detective agencies, and the humble six-shooter can’t match the lethal power of a Mexican army machine gun.

In retrospect, though, the popularity of the Western in 1969 represents the genre’s last gasp. Studios continued to make Westerns during the 1970s, but only three – Jeremiah Johnson, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and The Electric Horseman – would surpass $10 million in rentals in the entire decade.

On television, such long-running series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian had their last round-ups. The networks tried their hands at new Westerns, like Alias Smith and Jones (below), Hec Ramsey, Dirty Sally, and Lancer, but they were all short-lived. At the start of the 1980s, the genre was completely moribund. Subsequent efforts to recapture the Western’s former glory were mostly the equivalent of flogging a dead pony.

As a total cinephile, Tarantino is entirely aware of this aspect of the genre’s history. This is signaled quite explicitly in the decrepit condition of the Spahn Movie Ranch. Yet Tarantino also uses Rick’s career arc to signify its downward trajectory.

No character in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as strongly associated with the Western as Rick. His home is filled with collectibles like his Hopalong Cassidy coffee mugs. His walls are decorated with posters for The Golden Stallion and A Time for Killing. On set, he reads pulp oaters like Ride a Wild Bronc to relax between takes.

By using Rick to dramatize the twin declines of both Old Hollywood and its “bread and butter” genre, the narrative arc of Tarantino’s drugstore cowboy is one suffused with nostalgic melancholy. The key moment in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood occurs when Rick breaks down telling the story of Easy Breezy to Trudi Fraser, his Lancer co-star. He describes Easy “coming to terms with what it’s like to feel slightly more useless each day.”

The various threads of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s network finally knot together in the Manson family’s attack on Cielo Drive. At the moment of truth, it is telling that Rick reaches not for a firearm, but for the prop flamethrower he wielded in The 14 Fists of McCluskey. By recalling the moment when Rick shouts, “Anyone here order fried sauerkraut?”, Tarantino reminds us that violent spectacle and snappy quips will eventually replace the Western’s ritualistic showdowns.

Still, it is a musical allusion to the Western that gives Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its final grace note. Cliff and Rick have thwarted the Manson family’s attack. The ambulance takes Cliff to the hospital. Rick offers an explanation of what just happened to his neighbors. Jay recognizes Rick as television’s Jake Cahill. Via the intercom, Sharon invites him to come up for a drink. As Rick walks to the house, we hear the start of Maurice Jarre’s “Lily Langtry” [sic] from his score for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean.

John Huston’s film begins with an expository title shown below that highlights the western’s tendency toward self-mythology. It is especially apt for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s counterfactual history.

Jarre’s cue, though, appears in a scene where the renowned actress Lillie Langtry finally visits Judge Bean’s Texas town. Langtry is given a tour of the Bean’s house, now converted into a museum that also acts as a shrine to her. Bean worshipped Langtry, but tragically dies before he gets to meet her. Tarantino inverts both Huston’s sad ending and its dramatization of missed opportunity. By altering the course of history, the cowboy in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gets to be the real-life hero rather than the TV heavy. Rick also gets to meet the actress he’s admired from afar. Rick and Sharon are still both married to other people. But their chance meeting in the film’s epilogue feels more than anything like a dream fulfilled.

A star is unborn

In the previous section, I dwelt on the role of the Western in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood because of its symbolic significance in capturing a particular historical moment. But Tarantino borrows quite freely from another narrative prototype: the show-biz tale. In fact, while walking out of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I wondered aloud if it was Tarantino’s twisted take on A Star is Born.

Like A Star is Born, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood centers on a male performer whose career has started to decline and a female newcomer whose star is on the rise. Moreover, Rick’s drinking problems create an obstacle to his comeback in much the same way that alcohol contributes to the downfall of the male protagonists in all four versions of A Star is Born.

Tarantino, though, subtly alters this template in two ways. First, he depicts his two stars as neighbors rather than as a romantic couple. Secondly, he cleverly depicts Rick’s career arc as an inverse mirror of Sharon’s.

Tate was an Army brat who grew up in Europe. Her earliest work was as an extra in Italian films. She moved to Hollywood in 1962 and got her break playing Jethro Bodine’s girlfriend on The Beverly Hillbillies. In the mid-sixties, Tate made the move to films, appearing in Eye of the Devil and The Fearless Vampire Killers.

It was during production of the latter that Tate met her future husband, Roman Polanski. Tate’s role in Valley of the Dolls further enhanced her status as an “up and comer.” In 1968, Tate earned a Golden Globe nomination in the category of “Most Promising Newcomer — Female.”

In direct contrast, Rick’s career begins in Hollywood and ends in Italy. Rick enjoys early success with Bounty Law and The 14 Fists of McCluskey. But soon finds himself reduced to guest star roles on television. Against his better judgment, Rick agrees to star in four Italian quickies. Two of these are spaghetti westerns directed by Sergio Corbucci, a Tarantino fave who created the popular “Django” character. Rick returns to Hollywood but his future is uncertain. He could be the next Clint Eastwood, star of A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Or he could be the next Richard Harrison, star of $100,000 Dollars for Ringo and Secret Agent Fireball.

If this were all there was to the comparison, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But Tarantino hints at other parallels through a much more obscure and convoluted cinematic reference. An auteur as shrewd as Tarantino would undoubtedly remember that the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time” –used in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood under shots of Rick’s return from Rome – was previously featured in the opening sequence of Hal Ashby’s Coming Home.

The connection to Ashby’s film is strengthened by the casting of Bruce Dern as George Spahn, a role originally intended for Burt Reynolds. Early in his career Dern played Jane Fonda’s uptight, martinet husband in Coming Home. More importantly, during Coming Home’s climax, Dern’s character commits suicide by wading into the ocean to drown himself, just as James Mason does at the conclusion of George Cukor’s version of A Star is Born.

Which brings us back to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s controversial ending. Earlier I discussed the resemblance between its counterfactual history and multiple draft narratives. Here I want to discuss it as an illustration of the caprice of fame.

Much more than the endings of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, the climax of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels both resolved and unresolved. Hitler’s violent death in Inglourious Basterds surprised audiences who first saw it in theaters. Yet the historical record indicates that the Basterds simply saved Hitler the trouble of later killing himself and his wife, Eva Braun. At the conclusion of Django Unchained, the protagonist’s revolt clearly hasn’t ended slavery as a “peculiar institution.” But its story of personal revenge remains deeply satisfying.

The ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood left me with more questions than answers. I get it. Sharon Tate lives instead dying at the hands of the Manson family. Tarantino gives us the Hollywood happy ending that this story lacked in reality. But what’s next?

Do the deaths of Tex, Sadie, and Katie mean that Leno and Rosemary LaBianca also survive? Maybe. Perhaps the loss of three members of the cult might cause the others to reevaluate their loyalty to Manson. Perhaps Manson himself would reevaluate his plan to trigger a race war.

But maybe not. If Manson were the hero of Tarantino’s grindhouse climax rather than its villain, one could easily imagine the film running another twenty minutes with Manson vowing to get even. You might imagine it as something like the surprising “second climax” of Django Unchained. After mourning the loss of his compatriots, Charlie would proclaim. “The fires of Hell will descend upon the Hollywood hills. This time it’s personal.”

Perhaps the bigger question is whether Sharon continues to be the “It” girl during the next phase of her career. The allusions to A Star is Born suggest a steady upward trajectory. But the reality is that success depends upon a certain amount of luck. It is never assured. A few box office bombs and Sharon Tate might be reduced to the same sort of TV guest spots that Rick is doing.

In this way, the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood asks us to consider a potential paradox. Did Sharon Tate become more famous in death than she ever would have been in life?

The theme of talent tragically cut down in the prime of life is a hoary cliché of the celebrity biopic. Tarantino is smart to steer clear of it. Yet whenever we watch a film like Prefontaine, Beyond the Sea, or Lenny, one starts to wonder, “Would anyone bother to make this film if its subject had lived?”

To be sure, the totality of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood shuns any pat answer. Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas died at age 32. Initial reports said she choked on a ham sandwich in the midst of having a heart attack. I remember the media reports when Mama Cass passed in 1974. But does anyone who didn’t live through that moment?

James Stacy, star of Lancer, nearly died in a deadly motorcycle accident. (Tarantino hints at this fate by showing Stacy, sans helmet, riding his steel horse away from his trailer.) Stacy survived, but lost an arm and a leg as a result of his near fatal injuries. He eventually made a comeback in 1977 and even earned an Emmy nomination for his work on Cagney and Lacey.

Yet, if you mention James Stacy during dinner conversation tonight, I suspect your companion will ask, “Who?”

And then there is the scene where Pussycat and the other Manson girls walk past a large mural of James Dean in his iconic pose from Giant. Dean was certainly famous during his lifetime. But he became a legend at age 24 after his Porsche Spyder collided with another car, snapping his neck.

Would Sharon Tate have achieved stardom had she lived? God only knows. I certainly don’t. I do know one thing, though. Being a victim of the “crime of the century” preserved Tate’s image in popular memory with a vividness that very few human beings on this earth ever achieve.

Margot Robbie’s performance as Tate is extraordinary. She reminds modern viewers of the verve, spirit, and sensuality that Sharon brought to the screen. Yet it is the image of Tate as a tragically murdered heroine that Tarantino, like Mark Macpherson in Laura, appears to have fallen in love with. And it is this image that continues to haunt me some fifty years after Tate’s death.

Thank you to David and Kristin for their comments onf an earlier draft of this post. Thanks also to JJ Bersch and Maureen Rogers for letting me bounce some of ideas off them.

Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders remains the most comprehensive account of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Tom O’Neill, though, has spent the last 20 years investigating Manson’s crimes. His new book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the C.I.A., and the Secret History of the Sixties, claims that Bugliosi’s investigation was deeply flawed. Instead, his research suggests that Manson was a drug trafficker and C.I.A. operative. For O’Neill, the notion that Bugiliosi saved Los Angeles from a hippie death cult is wrong. The motive for the crimes was both simpler and more quotidian. All of Manson’s murders were the result of drug deals gone wrong. An interview with O’Neill can be found here.

The story that Terry Melcher witnessed a fight at the Span Movie Ranch between Charles Manson and a drunken stunt man sounds apocryphal. Yet it appeared in The Telegraph’s obituary for Melcher, which was first published in 2004. I haven’t been able to independently corroborate that story with another source. However, even if it isn’t true, it is part of Manson lore. I saw the same story repeated on at least three other websites. Doris Day’s death in May spawned the publication of a handful of articles about her relationship with Terry. They can be found here, here, and here. An brief overview of Melcher’s career as a record producer can be found in Rolling Stone’s obituary.

For those interested in learning more about Sharon Tate’s life, I recommend Sharon Tate: Recollection. It was written by Tate’s mother Debra. It also features a foreword by her husband, Roman Polanski.

Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood and Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls survey the momentous changes taking place in the film industry during the late 1960s.

Bruce Fretts provides a fairly thorough overview of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s voluminous pop culture references.

Several articles have also appeared that address different aspects of the film’s production. An interview with choreographer can be found here. Cinematographer Robert Richardson and production designer Barbara Ling detail their efforts to recreate the sets of the TV show Lancer here. Richardson also discussed Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s visual influences in a Hollywood Reporter podcast.

An interview with Mary Ramos, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music coordinator, can be found here. Guides to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music soundtrack can be found here, here, and here.

An analysis of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office implications is found here.

Finally, the release of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood has occasioned a number of think pieces that address aspect of the film’s counterfactual history and its identity politics. Here philosopher David Bentley Hart discusses the moral implications embedded in Tarantino’s counterfactual trilogy.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s gender politics is addressed here. The author, Aisha Harris, compares Tarantino’s depiction of Sharon Tate to other female characters in his filmography. Finally, zeitgeist readings of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in relation to the current political landscape can be found here and here.

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: More and more

Il Cinema Ritrovato Book Fair (photograph Margherita Caprilli).

Kristin here:

I mentioned in my entry on the African thread at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato that I filled in blank spaces in my program with a miscellany of intriguing films. Here are some of those films I saw, and others that David saw.

O Pão (1959)

Manoel de Oliveira’s first film, the gorgeous black-and-white documentary short, Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931. His last, Um Século de Energia, another documentary short, came out in 2015, the year of his death aged 106 (as did Visita ou Memórias e Confissões, a deliberately posthumous legacy film shot in 1982). That’s an 84-year career. I doubt any other filmmaker can claim as much.

Initially that career proceeded in fits and starts. He made more documentary shorts in the 1930s and then a black-and-white feature, Aniki-Boko (1942), during the war under an authoritarian regime. After the war he could not find funding and decided to study color filmmaking in Germany. During the 1950s he applied his resulting expertise to two documentaries: O Pintor e a Cidad (“The Painter and the City,” 1956) and O Pão (Bread). A beautiful print of the latter was shown in this year’s Ritrovati e Restaurati thread. It was to be his last film before he turned to feature filmmaking, though he never entirely gave up documentaries, particularly near the end of his life.

This hour-long film slowly follows the entire progress of bread, from wheat-fields to milling to baking to consumption. The images, whether in field or factory, are lovely, showing that Oliveira had indeed learned a great deal about color.

There is no voice-over narration, even during a lengthy scene in a large mill where technicians perform mysterious tests on samples of flour. The slow progression creates a soothing, almost mesmeric tone. Only toward the end does some social criticism emerge. A hungry urchin stealthily retrieves a roll dropped by a shopper, only to have it snatched away by a little street thug. Clearly bread, despite the lyricism of its production, is not for everyone.

Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Duvvum (1979)

Another must-see was Abbas Kiarostami’s early film, First Case, Second Case, also presented in the rediscovered-and-restored thread. Like Oliveira, Kiarostami began in documentary work. This remarkable film was started before the 1979 Iranian Revolution and finished after it–and then banned.

The film’s beginning rather resembles other Kiarostami openings, with a simple scene in a classroom. A teacher drawing the anatomy of an ear on a blackboard is interrupted by a knocking noise caused by one of his students. No one confesses or reveals who caused the noise, and the teacher suspends seven of the boys, who spend the next days in the hall outside the classroom.

This scene is revealed to be a 16mm film being shown to a succession of teachers, government officials, religious leaders, and the fathers of some of the boys. In the latter cases, some variant of the framing above is shown, with an arrow pointing to the son of the father being interviewed. Unseen, Kiarostami asks them the same question: did the boys do right in refusing to reveal who disrupted the class? Some of these interviewees became key figure in the Islamic Revolution. (Jason Sanders’ program notes for a screening of the film provide some information about this historical context.)

This “documentary” has of course been carefully staged. A page from Kiarostami’s script reveals how he designed the passing days of the boys’ suspension, with different ones standing or sitting each time. The illustration is from Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht’s blog entry on the film, where he credits First Case, Second Case with introducing the interview technique into the director’s work.

This first case shows the boys maintaining their refusal to identify the culprit. In a new scene, the second case, an alternative outcome shows one of the boys naming the guilty classmate to his teacher. Again, Kiarostami interviews many of the same people as to whether they believe the boy’s decision can be morally justified.

If not as charming as some of Kiarostami’s later work, First Case, Second Case contains a familiar combination of complexity and simplicity, as well as a fascination with people telling their own versions of events.

The film has been picked up by Janus in the USA, which should mean that it becomes available from Criterion on Blu-ray and/or its streaming service, The Criterion Channel.

Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

In recent years, Il Cinema Ritrovato has featured the films of a major Hollywood director as one of its main threads. This year it was Henry King. I managed to miss nearly all of his films. In part I feared that, since the auteur du jour is always one of the the more popular items in the program, the screenings would be crowded. Word of mouth suggested that they were.

Still, I had an afternoon free, and I wanted to guarantee myself a good seat for Varda par Agnès, showing later in the day. I went to an earlier screening in the same theater, and I was glad I did. Twelve O’Clock High is an impressive and entertaining film, if not an outright masterpiece.

Fitting into David’s set of innovations typical of the 1940s, the action is enclosed by a framing situation. A man we eventually discover was an American officer posted in England during World War II bicycles out into the countryside and visits the derelict remains of the military airport where he served. (Above, played by Dean Jagger in a role that won him a best-supporting-actor Oscar).

For a long time the story concentrates on General Frank Savage (Gregory Peck), who takes over command of an underperforming bomber unit in the same air station we saw at the beginning. He proves an absolute stickler for discipline, initially alienating the pilots he commands. Eventually he wins their respect, of course, and he learns to unbend a bit.

Eventually a series of air battles occur, with some very impressive and genuine combat footage, including aerial views of bombs exploding on their German targets. The film was presented in a nearly pristine 35mm print, which certainly contributed to my pleasure at having ended up at that screening somewhat by chance.

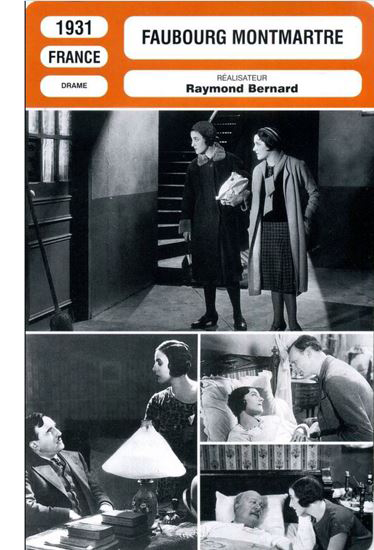

Faubourg Montmartre (1931)

I definitely planned from the start to see this film. I very much admire director Raymond Bernard’s 1932 World War I drama Wooden Crosses, his next feature after Faubourg Montmartre. Indeed, I had done a video on it for The Criterion Channel (“Observations on Film Art” #16 “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses“)

While a slighter film than Wooden Crosses, Faubourg Montmartre is quite stylish and technically impressive, considering that it was Bernard’s first sound film. In it he abandons his concentration during the silent era on historical epics (his best-known being The Miracle of the Wolves, from 1924).

Here he tackles a melodrama in a contemporary setting, centering around Ginette, a somewhat naive young working-class woman, played by popular star Gaby Morlay. She and her older sister Céline live and work in the titular district of Paris, the disreputable area of cheap entertainment and brothels. Céline works as a prostitute but tries to protect Ginette from such a life. Becoming more dependent on drugs, however, she nearly dupes Ginette into following her into prostitution.

Despite its grim setting, the film has many light moments, mostly provided by the amiable Morlay. It also contains some impressive musical numbers, one a variety number by Florelle and a café song about prostitution by Odette Barencey.

The film was yet another in the festival’s Ritrovati and Restaurati thread.

Georges Franju

There was an unaccustomed focus on documentaries this year, which presumably was the occasion for devoting a small thread to Franju. Of the thirteen shorts which he made or at least is tentatively credited with (most of them commissioned documentaries), eleven were shown. Judex, his fiction feature paying homage to the serial of the same name by Louis Feuillade, was also on the program.

I tried to see all the Franju shorts, since only Le Sang des bêtes (above) and Hôtel des Invalides are well-known in the US. The prints shown ranged widely in quality, some being in 35mm and some 16mm. En passant par la Lorraine was almost unwatchable, though most of the rest were in varying degrees acceptable.

The most interesting revelations were perhaps Mon chien (1955), a melancholy narrative based on the common habit of people abandoning their pets in the countryside. The amazingly callous parents of the little heroine dump her beloved German shepherd in the woods on their way to a vacation spot. The film follows the faithful animal’s trek home, only to find a locked house and a dog-catcher waiting. An empty cage signals that the animal was euthanized, with the voiceover of the girl calling forlornly for her pet. The other was Les poussières (1954), a lyrical survey of many kinds of dust generated in the world, ending in a strong anti-pollution message.

It was a pleasure to see this body of work brought together, but the screenings also demonstrate the pressing need to restore many of these films.

A Gabin tribute

DB here (with films I saw in boldface):

Jean Gabin has become emblematic of French cinema from the 1930s and after, so the several films devoted to him were welcome. Programmer Edward Waintrop included the classic Pépé le Moko (1936) but correctly assumed he didn’t have to show this crowd La Grande Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and Le Jour se Lève (1939). Edward’s catalog entry wisely emphasized how much Gabin owed to Julien Duvivier, an underrated director who helped the young actor find starring roles.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

In her book on popular song in French cinema, our colleague Kelley Conway has written a superb analysis of Cœur de Lilas, and you can find a clip of Gabin’s big musical number here. Director Anatole Litvak handles his performance in a long tracking shot that keeps our attention fastened on Gabin’s half-scornful, half-boastful mug as he spits out lines about his girlfriend’s bedroom calisthenics (“The rubber kid. . . She dislocates you”).

Gabin plays the third point of a love triangle in Cœur de Lilas, but he’s somewhat more central to the lesser-known Du Haut en Bas (1933), a sort of network narrative that reminds us that The Crime of M. Lange (1936) isn’t the only film tracing the tangled passions in a courtyard community. More easygoing here but still a force to be reckoned with, Gabin plays a footballer with his eye on an aspiring teacher forced to work as a maid. Other plotlines, including Michel Simon’s raffish wooing of his landlady, intermingle in this thoroughly agreeable movie by the great G. W. Pabst.

A generous sampling of Gabin’s later career included La Marie du Port (1949), Le Plaisir (1951), Maigret tend un piège (1957), and the brutal Simenon adaptation Le Chat (1970), the first film I saw on my first visit to Paris. En Cas de Malheur (1957), an efficient plunge into sex and crime by Autant-Lara, features Gabin as a prestigious but dodgy lawyer drawn to the pouting self-regard of Brigitte Bardot. In youth and age, as a sort of French Spencer Tracy, Gabin could exude both relaxed joie de vivre and stolid menace. An icon, as we say.

Americana, urban and rural

State Fair (1933).

Speaking of Spencer Tracy, it was a pleasure to see this Milwaukee native in a long-neglected racketeer drama. Quick Millions (released May 1931) arrived in the middle of the first big gangster cycle and was overshadowed by two Warners hits, Little Caesar (January 1931) and The Public Enemy (May 1931). As part of Dave Kehr’s welcome second Fox cycle, Quick Millions had its own pungent force.

It traces the familiar trajectory of a working stiff, trucker “Bugs” Raymond, who claws his way to the top of the mob. Thanks to blackmail and crooked labor maneuvers (“The brain is a muscle,” he tells his moll), he winds up triggering a spate of gangland killings that eventually swallows him up.

Quick Millions was noticed as one of the earliest films to find a smart tempo for talkies, one that relies less on long speeches than snappy scenes delivering one point apiece. The passage of time is signaled by changing license plates, and the ending is a shrug, shoving Bugs’ death offscreen and giving him none of the tragic flourishes of Little Rico or Tom Powers. For almost every scene, the little-known director Roland Brown finds an unexpected twist in visuals or performance . Who else would film a sidling George Raft jazz dance from a high angle and then supply inserts of his legs, from behind no less?

Fox found more success with a folksy Grand Hotel variant based on the popular novel State Fair (1932). Henry King’s 1933 film was planned as an “all-star” vehicle, and it did boast Will Rogers, Janet Gaynor, and Lew Ayres. An Iowa family heads to the fair, aiming for blue ribbons in pickle preserving and hog-fattening. The son has a surprisingly carnal affair with a trapeze artist, while the daughter meets a roguish reporter who makes her rethink her engagement to a hick back home. State Fair‘s script gives the plot a happier ending than the book did, but that’s not necessarily a problem; we want these kind souls to enjoy a bit of glory.

Henry King became famous for rustic realism with Tol’able David (1921), a model for Soviet filmmakers, and Ehsan Khoshbakht’s King retrospective reminded us that he worked this vein a long time. From 1915 Twin Kiddies (a Marie Osborne vehicle) to Wait ‘Till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952), this loyal Fox craftsman showed himself, like Clarence Brown at MGM, an adaptable director with an unpretentious gift for celebrating small-town life.

Still more, more…

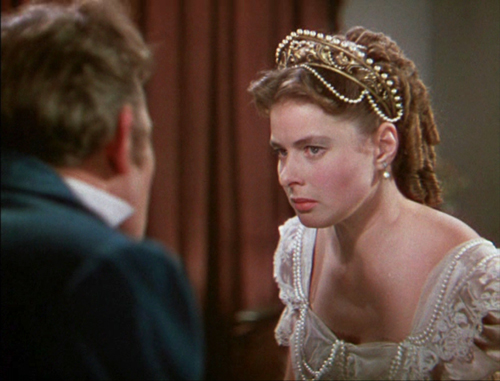

Under Capricorn (1949).

I could go on about other films, such as Zigomar: Peau d’Anguille (“Zigomar, the Eelskin,” 1912), Victorin Jasset’s forerunner of Feuillade’s delirious master-criminal sagas. (In one episode, an elephant’s trunk fastidiously picks the lock on a circus wagon and drags away a strongbox.) Our next entry will spend a little time looking at a neat Genina film from 1919. In the meantime, I’ll sign off by mentioning two other high points.

The pretty Academy IB-Tech print of Under Capricorn (1949) made me like the film quite a bit better than previous viewings. As ever, one high point was La Bergman’s virtuoso soliloquy admitting her guilt. Any other director of the time would have reenacted the crime in a flashback, but, in the shadow of Rope (1948), Hitchcock makes her squeeze out her confession in a ravishing single-take monologue running almost eight minutes.

Its power comes partly from the fact that the framing withholds the facial response of the man who loves her. He’s slowly understanding the depth of her devotion to her husband during penal servitude. “How did you live all those years?” he murmurs. How’d you think? Her glance flicks over him, in both guilt and defiance (above).

Finally, no film gave me more pure pleasure than the restoration of Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Sony archivist Grover Crisp explained that the original prints had all been made from the camera negative (!) and so he had no internegatives or fine-grain masters to work from. Nevertheless, this digital version, made in 4K with wetgate scanning, looked superb.

I tend to judge Boetticher westerns by the strength of the villains, meaning that Seven Men from Now (Lee Marvin) and The Tall T (Richard Boone) sit at the top of my heap, but it’s hard to resist the laconic dialogue Burt Kennedy supplied everybody in Ride Lonesome. And the antagonists facing Randolph Scott here–Lee Van Cleef (brief but unforgettable), Pernell Roberts (the good-bad rascal), and sweet-natured dimwit James Coburn (on his way to rangy knife-wielding in The Magnificent Seven)–add up pretty powerfully. Against them stands Scott as vengeance-driven Brigade, an unyielding chunk of sweating mahogany.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator. Thanks also to Dave Kehr, Grover Crisp, Mike Pogorzelski, and Geoffrey O’Brien for talk about many of the classics on display.

The entire Ritrovato ’19 catalogue, with full credits and essays, is online here. There are also videos of many events, including master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Quick Millions was remembered several years after its release for “the rapid rhythm of its continuity.” See Janet Graves, “Joining Sight and Sound,” The New York Times (29 November 1936), X4.

John Bailey’s introduction to Under Capricorn included a revealing short explaining the Technicolor dye-transfer process. For further information there’s the remarkable George Eastman House Technicolor research site and of course James Layton and David Pierce’s superb book The Dawn of Technicolor.

Kristin discusses Kiarostami’s landscape techniques in a Criterion Channel Observations entry. In American Dharma, discussed by David here, Errol Morris reveals that Twelve O’Clock High was an inspiration for Steve Bannon’s political career.

The Ritrovato program notes credit Fréhal as the working-class singer in Faubourg Monmartre, but Kelley Conway’s Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in French Film (linked above) identifies her as Odette Barencey, a lesser-known chanteuse of the period who resembled Fréhal.

Opening shot of Ride Lonesome (1959).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas, but docus as dramas

Making Montgomery Clift (2018).

DB here:

Our days and nights at our annual film festival would have been hopelessly frustrating if we hadn’t already seen several of the fine items on offer. At other festivals we caught Asako I and II, Ash Is Purest White, Dogman, The Eyes of Orson Welles, The Girl in the Window, Girls Always Happy, The Image Book, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Lucky to Be a Woman, The Other Side of the Wind, Peterloo, Rosita, Shadow, Styx, Transit, and Woman at War. As you can see, our programmers assembled a spectacular array of movies. Most of these we’d happily watch again, but there were so many new offerings we had to resist.

With this elbow room I could pay attention to three documentaries I’d been looking forward to. They had all the appeal of a fictional film, with keen plots and tricky narration and fascinating characters. It didn’t hurt that two were about world-class celebrities and the third appealed to my deepest conspiracy-theory instincts.

Heart of Glasnost

Werner Herzog’s Meeting Gorbachev was a surprisingly conventional effort for this legendarily odd filmmaker. As my colleague Vance Kepley remarked, Herzog typically makes documentaries of two types. He probes eccentric personalities (the “ski-flyer” Steiner, or a man trying to hang out with grizzly bears) or he treks into remote, dangerous landscapes (Antarctica, a swift-moving volcano, the fires of Kuwait).

But this portrait of Mikhail Gorbachev is neither. Herzog’s interview with the elderly but still vigorous Soviet leader is interrupted by biographical inserts tracing his career, his struggles, and his policies. Newsreel footage and other talking heads provide context in a mostly straightforward account of the man’s life and work. Only a story about tree slugs briefly diverts Herzog’s attention.

The film revives our appreciation of a politician many people have tried to bury. Gorbachev emerges as a thoughtful, upbeat man who tried to make the Soviet Union more democratic and open to the popular will, to create Communism with a human face. But he triggered events that cascaded too quickly. He broke up the USSR but also cleared a path for economic collapse and a corrupt kleptocracy. His suggestion for his tombstone inscription: We tried.

Herzog’s montages dramatize the breakdown of national borders, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the coup that destabilized reforms while Gorbachev was away from Moscow. The main principle of swimming with sharks in a bureaucracy is: Don’t tell anybody what you’re going to do until you do it. The 1991 unseating of Gorbachev by Yeltsin reminds me of a second: Don’t take vacations.

Meeting Gorbachev is actually a double portrait, because Herzog puts a good many personal feelings into it. He remembers the emotion he felt as Germany reunited. Gorbachev’s call for “a common European home” rouses him to recall his youthful Wanderjahr when he walked across the continent.

Although I don’t think the name Trump is mentioned, his shadow falls over the whole film. Portraying a sane, reasonable leader today seems virtually a bid for controversy. Gorbachev reminds us of the reductions in nuclear weaponry that he negotiated with Reagan and Thatcher. “People say that Reagan won the Cold War. Actually, it was a joint victory. We all won.” The idea of pursuing policies that benefit the whole world seems oddly old-fashioned right now.

When Herzog gives us a glimpse of a robotic Putin peering down into the casket of Gorbachev’s beloved wife, we’re forced to register what Russia has become, and how the US is now complicit with it. Maybe this film has more of the director in it than I initially thought. As Herzog dared to declare in an earlier film, Nosferatu lives.

Unmaking an icon

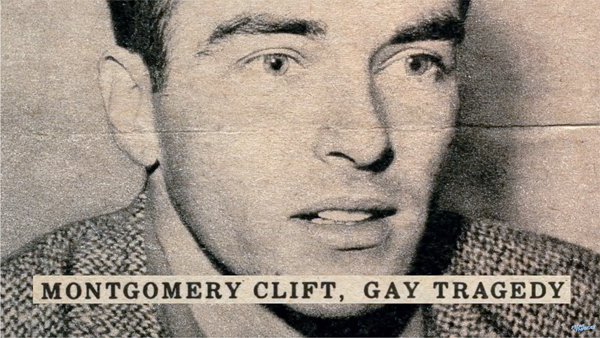

Whenever I see Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift kiss in A Place in the Sun, I think: Here are the two most beautiful people in the Western world. I’m not alone. Clift was one of Hollywood’s most celebrated stars after the war, partly because he didn’t easily fit the molds of either the old guard or the new.

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

In this context, Clift looks like cannon fodder. Put him alongside Lancaster in From Here to Eternity, and you’ll find it hard to believe he’s the prizefighter; in that movie, only Sinatra looks skinnier. Delicate, with an innocent stare and an angular body, a wide-eyed Clift takes over his debut film, Red River (1948), from the lumbering John Wayne. Hawks claimed he told Clift that if he quietly watched the action from behind his tin coffee cup, he could steal every scene.

Clift carved out a space all his own. Late in his career, the tremor in his voice and a wary tilt of the head gave him antiheroic quality, as in Wild River (1960). Not for him the over-underplaying of Brando or the unpredictable gestures and dialogue cadences of James Dean. He has his own method, not The Method.

One of the many merits of Making Montgomery Clift, a fascinating documentary by Robert Clift and Hillary Demmon, is that it triggers such thinking about the actor’s craft. Emerging from a hillock of papers, home movies, video tapes, and audio tapes, the film documents two dramas–that of Clift’s life, and that of the process through which complex human beings get flattened into media clichés. As a bonus, we reap many insights into how actors shape their performances, sometimes against the grain of the script they’re handed.

On the life, we learn that Clift was often a buoyant, bisexual fellow, not the brooding and moody figure of legend. He was also a demanding artist who turned down juicy parts. When he signed up for a role, he insisted on vetting the script and sometimes rewriting it. In split-screen Clift and Demmon present the page on the left, scribbled up with Monty’s notes and excisions, and then run the scene alongside. The excerpts they give us from The Search and Judgment at Nuremberg show how a committed actor can strip an overwritten scene down to an emotional core.

If nothing else, Making Montgomery Clift shows us how performances shape movies: the actor as auteur. But it’s exactly this analysis of craft that’s missing from most film biographies. Those doorstop volumes revel in scandal and exposés because publishers think that a straightforward account of hard-won artistry–the sort of thing we routinely get in biographies of composers or painters–doesn’t suit movies. The result is glamor, excitement, sad stories, and banal interpretations rolled into one fat book.

This is the other drama so patiently traced by Clift and Demmon. They show how two 1970s biographies set a mold for the Tragic Homosexual story that has dogged the Clift legend ever since. Just as the filmmakers pay attention to the movies, they provide close readings of passages in the books, and the evidence of sensationalism, inaccuracy, and offhand speculation is pretty damning. One description of Clift’s injured face after his 1957 car crash savors brutal detail. And it’s not just the ambulance-chasers; passages from John Huston’s autobiography also radiate bad faith.

Clift understood that cookie-cutter journalism would oversimplify him. Thanks to the endless tapes he and his brother Brooks made of their phone conversations, we hear his quick condemnation of “pocket-edition psychology.” There’s a continuum between the tabloid headline, the talk-show time-filler, the celebrity memoir, and the bulging star bio. All try to iron out the wrinkles. During the Q & A, Robert Clift talked about traditional biographies as exercises in taxidermy: “It feels so real because it’s dead.” Hillary Demmon remarked that they wanted to “open up Monty to more readings.”

Making Montgomery Clift proves that academic talk about the “social construction” of this or that isn’t hot air. The film ranks with Errol Morris’s Tabloid as combining a fascinating life story (full of, yes, drama) with a serious argument about how celebrity culture reduces that story to captions and soundbites. Let’s hope the film makes its way to wider audiences, in theatres and on disc and streaming services. It belongs in the library of every college and university, so that students can get acquainted with an extraordinary performer, appreciate the art of star acting, and witness how the media shrink people to less than life size.

In the crosshairs of history

Like other baby boomers, I’m a connoisseur of conspiracy theories. But we have an excuse. Today’s kids grow up with school lockdowns and street shootings; we had assassinations. Patrice Lumumba (1961), Medgar Evers (1963), John Kennedy (1963), Lee Harvey Oswald (1963), the Freedom Summer murder victims (1964), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King (1968), and Robert Kennedy (1968): this cavalcade of killings made political life seem a theatre of Jacobean intrigue.

Not the least of these was the 1961 death of the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammerskjöld. Hammerskjöld had pressed for peace in the Middle East and was a patient advocate for decolonization in Africa. En route to the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga, his plane crashed. For years many people, including former President Harry Truman, believed that the plane was shot down in order to murder Hammerskjöld.

So of course I had to see Mads Brügger’s Cold Case Hammerskjöld. It did not disappoint.

At first it seems cutesy, with the filmmaker dictating his findings to two African women typists, who occasionally turn to question him. He’s both pedantic and flamboyant (wearing white clothes to match the habitual outfit of a villain he will expose). In contrast there’s the veteran Hammerskjöld researcher Göran Björkdahl (on the right above beside Brugger). Björkdahl is a steady presence as the men question witnesses to the crash and then, crazily, set out to dig up the site. When they’re forbidden to do so, you might think that we’ve got another film about not making a film.

Instead, in the spirit of Morris’s Thin Blue Line, the story we’re investigating drifts into another story, and then another, as documents and witnesses and people who refuse to talk to the filmmakers lead to some appalling charges. Let’s simply say, to preserve the film’s shock value, that the Hammerskjöld case reveals SAIMR, a white supremacist militia for hire. The most horrifying claim about SAIMR and its leader is broached by a well-spoken mercenary purportedly haunted by guilt. His claim has been contested by researchers (as reported in the New York Times). Even if his charge doesn’t hold water, though, the existence of SAIMR seems well-documented.

We conspiracy theorists are often told that history proceeds by accident, not by intention. Yet some intentions succeed splendidly (viz. the killings itemized above), and some succeed by luck. Perhaps the darkest intentions chronicled in Cold Case Hammerskjöld were too crazy to be implemented. But that doesn’t lift responsibility from the feverish minds who dreamed them up, or from the institutions–perhaps mining companies, perhaps MI6 and the CIA–that gave them a hand. In an era when white supremacy has come on strong, Brügger’s film will remain the provocation it was intended to be.

One more entry will talk about still more films at this festival which so generously spoils us.

Thanks to film festival coordinators Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, Zach Zahos, and their dedicated staff for this year’s wonderful event.

Cold Case Hammerskjöld.

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things

From “The Killer,” Spirit Comics (8 December 1946), by Will Eisner and studio.

DB here:

This is my final effort to cram my latest book down the resisting gullet of the reading public. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling has just come out in paperback and I’ve been using our blog to trace out some relevant ideas that surfaced in recent books and DVD releases. The first entry dealt with some general issues, the second with popular culture’s drive toward variation, the third with craft and auteurism. This one has murder on its mind.

Noir as mystery and mystique

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

Crime looms large in Reinventing Hollywood. But I forsake the usual category of film noir. It didn’t exist as a concept for the filmmakers or audiences of the day. It’s the creation of critics, first overseas and then, much later, here at home. That doesn’t make the category invalid, though. Many art-historical categories (Baroque, Gothic) are later inventions, and those can be illuminating. Still, I think we gain some understanding if we situate our inquiry, for a time at least, at the level of what people seemed to be trying to do at the time.

Put it another way. By focusing on noir as the model of Forties narrative, we miss the ways in which the films we pick out under that rubric participate in wider trends. We miss, for instance, the new importance of mystery in all plotting of the period.

In the 1930s, mystery was mostly confined to detective stories. Think of your prototypical 1930s movie; it’s unlikely to have a mystery at its center. (Okay, maybe we’re curious about the identity of Oz the Great and Powerful.) In the 1940s, though, filmmakers began to scatter mystery devices into other genres. Mystery became a central storytelling strategy for personal dramas (Citizen Kane, 1941; Keeper of the Flame, 1943), romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan, 1945), war films (Five Graves to Cairo, 1943), social comment films (Intruder in the Dust, 1949), and domestic melodrama (Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Locket, 1946; A Letter to Three Wives, 1948). Some of what we call noir is part of this trend.

Over the same period, a fairly minor genre got promoted. Psychological thrillers can be traced back to Gothic novels and sensation fiction, but they became a distinct part of crime literature in the 1930s. They became an important genre for cinema in the 1940s, and so Reinventing Hollywood devoted a chapter to films like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

These aren’t canonical “noir” films, at least if your notion of noir stems from hard-boiled fiction. Some rely on the guilty-party plot exemplified in C. S. Forester’s novel Payment Deferred (1926), Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope (1929), and Anthony Berkeley Cox’s novel Malice Aforethought (1931). Less famous but just as interesting is the “woman-in-peril” thriller.

This was an upmarket version of romantic suspense novels associated in earlier decades with Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), one of the top-selling books of the 1940s, lifted the genre to respectability. Revisiting traces the wide-ranging variations that followed in film, fiction, and theatre. (An early draft of that chapter is elsewhere on this site.) Mystery is central to this subgenre. Who is endangering the protagonist? What are the real motives of the people around her, especially her lover or husband? Are her friends complicit? How will she escape?

The gynocentric thriller remains powerful in popular literature today. We’re currently in a rapid-fire cycle of it, typified by the work of Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn. Some of the books have come to the screen: Gone Girl (2014), The Girl on the Train (2016), and A Simple Favor (2018). The HBO series Big Little Lies (2017-on), turns a fairly satiric domestic-suspense novel into a heavier exploration of spousal abuse. I’ll be writing more about this cycle later (and giving a paper on it this summer), but let me note two recent examples. One takes its Forties sources for granted, the other flaunts them. Both are coming to a screen near you.

In Alex Michaelides’ new novel The Silent Patient Alicia Berenson, an emerging painter, is found guilty of shooting her husband. Because she seems in permanent shock and refuses to speak a word, she’s confined to a mental institution. There the ambitious young psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to ferret out why she remains silent. The narration alternates, Gone Girl fashion, between Theo’s first-person investigation and Alicia’s diary of events leading up to the killing.

It’s a spare tale narrated in a clumsy style that doesn’t distinguish the two voices. And it reminds us that if you become a character in a novel or movie, don’t get into a car. But it does show the persistence of Forties strategies.