Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

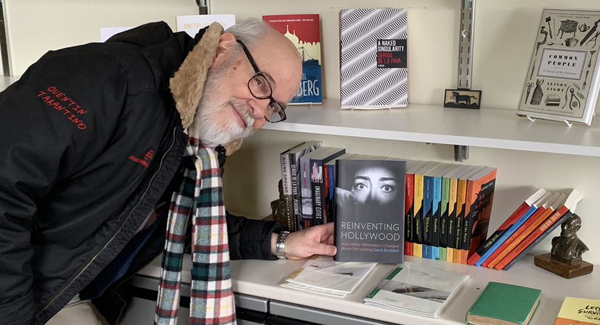

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Welcome to the Variorum

Happy Death Day (2017).

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted. I hope all these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

The first entry in this series is here.

Seeing Happy Death Day 2U reminded me of one of the central arguments of Reinventing. But before I get to that, let me talk about English drama of the years 1660-1710. No, really.

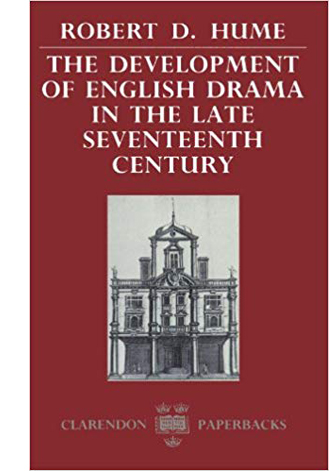

500 plays and more

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

Hume’s method was simple and drastic. He read all of the preserved plays publicly performed in London between 1660 and 1710. Along with revivals, pageants, translations, and adaptations, there were about five hundred “new” plays, and these he concentrated on. They included famous ones like Marriage à la Mode and The Way of the World, as well as many obscure pieces.

The result was The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1976). Its first part surveys the conventions and formulas found in subgenres of comic and serious drama (sentimental romance, horror tragedy, and many others). In the second part Rob traces the development of these types across the period.

From the standpoint of my research I was fascinated to see that Rob reveals a teeming set of variations on generic schemas. Characters, situations, and plot twists are mixed and matched. A plot based on romance leading to marriage commonly shows the couple outwitting blocking characters. Sometimes, though, the man must win the woman over. Or she must conquer him. Similarly, when extramarital seduction drives the action, a man may pursue a woman but

occasionally an amorous, often older woman is the pursuer (She wou’d if she cou’d; The Amorous Widow) or an ineffectual male, usually a henpecked husband, is a comic pursuer (Sir Oliver Cockwood in She wou’d).

In Planet Hong Kong I called this tendency of mass entertainment a “variorum” one, by analogy with editions that print all the versions of a major text.

Once a genre gains prominence, a host of possibilities opens up. Horror filmmakers are likely to float the possibility of demonic children, if only because the competition has already shown demonic teenagers, rednecks, cars, and pets. Similarly, once the male-cop genre is going strong, someone is likely to explore the possibility of a tough woman cop.

You might object that using the term “variorum” is just a fancy way to talk about the mechanical formulas of mass entertainment. But by putting the emphasis on variety within familiarity, the label points up the need for constant innovation, great or small. Fans of film genres readily recognize this churn, but what I began to realize is that it’s common as well in both folk narratives and more “industrialized” ones, like theatre and popular literature.

Monuments of scholarship like Hume’s Development remind us that the variorum principle is a primary engine of popular entertainment. The urge for novelty puts pressure on artists to try to fill every niche in the ecosystem, sometimes forcing competitors to strain for far-fetched possibilities. The wild treatment of noir conventions in Serenity is a recent example.

Beyond genre: Style and narrative

Cover Girl (1944).

Some time in the 1990s I began to realize that a lot of my research applies the variorum principle to domains outside genre. For instance, Figures Traced in Light and the last chapter of On the History of Film Style look at cinematic staging from this standpoint, showing how basic principles of staging got realized in many ways across film history. I applied the variorum principle to particular narrative techniques in some essays in Poetics of Cinema, considering the options of forking-path plots and network narratives.

Reinventing tries to trace a wide range of storytelling options as they consolidated in the 1940s. Rob Hume could study every preserved play, but I couldn’t do that for films. I managed to watch about 600. (Later entries in this blog series will mention some I missed.) Not surprisingly, I found the variorum principle at work in the narrative techniques on display.

I set out a couple of prototypes for the most common plots: the single-protagonist one (Five Graves to Cairo) and the plot based on a romantic couple (Cover Girl). Beyond those, I considered less common plot options, such as multiple protagonists and network narratives. Then I went on to consider narrational strategies that cut across all types. What strategies were available for mounting flashbacks, or expressing subjective states? In effect, I tried to reconstruct Forties Hollywood’s storytelling menu, largely independent of genre.

Another way to put this is that I was tracking norms. But the variorum principle shows that a norm isn’t just a mandate: Do this. Any normative practice is a cluster of stronger and weaker options.

These options lead to a cascade of further (normative) choices. Shoot a dialogue scene in a two-shot and you’ll need to adjust performances for viewer pickup. Shoot using a lot of close-ups and you’ll need to cut among your actors more frequently to keep everybody “in the scene”–that is, salient for the audience.

Choose a flashback and you’re forced to decide how far back to start it, what to include that’s relevant to the present action, and how to remind the audience of action that preceded the flashback. Of course you may also choose to try to make viewers forget, because you’ve misled them. That’s what happens in Mildred Pierce and Pulp Fiction.

Usually we find the variorum principle working among several films. What if creators put the principle to work within a single film?

The first day of the rest of your life

Every now and then filmmakers try out forking-path narratives. These plots, I suggest in this essay, trace out alternative futures for their characters. Blind Chance and Run Lola Run are prototypes, though there are plenty of examples earlier and later.

Sometimes the protagonist is dimly aware of the options. The protagonists of Blind Chance and Run Lola run seem to learn from their mistakes in the parallel lines of action. This can yield “multiple draft” narratives in which later story lines show characters struggling to achieve the best revision of circumstances they can.

I’d distinguish plots like these from Groundhog Day, which presents not alternative futures but identical replays of a specific time period. What makes each iteration different is that Phil, realizing he’s living the same day over and over, struggles to behave differently. This pattern has come to be called a time-loop narrative.

The time-loop and forking-path patterns usually provide only changes in the story-world elements of each track. Phil’s changing his routines takes place against a background of recurring situations. Similarly, the protagonist of Source Code gets to try out different ways to stop a train bomber.

What, though, if a looped or forking-path movie tried to survey several alternative genre conventions? That would give us a sense that the variorum idea has been swallowed up within a single film.

This happens, I think, in Happy Death Day. By now it’s not a spoiler to indicate that this slasher movie borrows the Groundhog Day premise and loops a single day in the life of mean girl Tree Gelbman. Each day she’s killed by a stalker in a babyface mask. Each time she dies, she awakes in the bed of Carter Davis, who brought her to his dorm room (without sexytime) to recover from a night of partying. As the days repeat, Tree becomes more desperate to avoid her fate and tries a variety of stratagems. They fail, until they don’t. In the course of them Tree learns to become a nicer person.

What’s interesting to me is that several variorum alternatives of the slasher genre are squeezed into this one film. The stalker kills Tree in a shadowy underpass, in a bedroom during a frat party, in her sorority bedroom, under a friend’s window, on a campus trail, and after chasing her through a hospital, a parking ramp, and a highway. She’s knifed, bludgeoned, hanged, run over, and stabbed with a broken bong.

Of course the shooting-gallery premise of slasher films often generates a string of variations across the film. Boyfriends, girlfriends, figures of authority, and passersby are dispatched by Jason or Freddie Krueger in ever more exotic ways. But in Happy Death Day, the sense of genre replay is heightened by Tree’s being the sole target of the ten variant homicides (one of which is a forced suicide). It’s as if we were watching a performer auditioning for screen tests in which she might be cast as one victim or another. But here the victim is always the Final Girl.

The comedy that haunts many slasher films is enhanced by the preposterous premise that Tree will survive. The deaths become vivid as replays by virtue of their tongue-in-cheek humor, as each slaying tries to outdo the earlier ones and as Tree sarcastically comments on her fate.

With the time-loop convention put into place by Groundhog Day, our interest goes beyond changes in the story world and concentrates more on narrative structure. We watch for scenes we’ve already seen, expecting them to be revised in surprising ways. The handling of the replays foregrounds film technique as well, as when in Happy Death Day Tree’s frantic walk across the quad after a late reset is rendered in distorted imagery reflecting her confusion. We register this as a variant on her earlier stride down the same route–hung-over, but not yet desperate.

One virtue of such repetitions for low-budget cinema is that the variant passages can be shot quite economically. You can save time on location by reusing camera setups, with the actors altering their performance, or their costumes and makeup. In the DVD bonus material, director Christopher Landon talks of following this production strategy. Why does low-budget cinema explore odd narrative options? They can come cheap.

Variants times 2 or 3

Happy Death Day 2U (2019).

A film series often self-consciously varies the story world that the continuing characters confront. In the studio era, Charlie Chan went to the circus and the opera, Mr. Moto got involved in a prizefight scheme, and Ma and Pa Kettle visited Waikiki. Today’s superhero franchises rely on fully-furnished, constantly changing story worlds. Back to the Future, though, launched a series that did more than present a story world that shifted from film to film. The trilogy self-consciously reorganized its plot structure and narration, with replays and alternative outcomes enabled by a time-travel premise. We’re expected to appreciate the altered replays as part of the film’s experience.

The sequel Happy Death Day 2U has just been released in that Dead Zone in which low-end American genre cinema flourishes. I have a lot to say about it, but it’s probably too soon. Still, it’s no spoiler to indicate that it offers a set of variants on the givens of the first film. For one thing, what caused the time loop of the original is now explained. The birthday motif gets elaborated via Tree’s backstory, with strong doses of sentiment. And suspects who were eliminated in the initial film step forward as plausible culprits in this one.

Just as important, there’s an added structural premise that gives the new entry an acknowledged affinity with Back to the Future II and other forking-path tales. To top things off, the second installment supplies a revised version of the outcome of the first one.

Although the sequel isn’t thriving at the box office, perhaps there will be a third entry.

I have the third movie and I have already pitched it to Blumhouse. Everybody is ready to go again if this movie does well. I keep shifting the tone, genre a little bit. The third movie I know is going to be a little different. It’s going to be really bonkers and really fun.

Bonkers or not, having another version would show that the Variorum never sleeps.

Two last points. First, a film I discussed last time, Confession (1937), internalizes the variorum impulse in a milder way, by replaying a key scene from a different character’s viewpoint. More unusually, Confession is a remarkably close remake of a German film, Mazurka, and thus constitutes a homegrown variation on the original.

Secondly, why study the variorum principle? Hume points out:

To insist on analyzing the famous writers and plays in isolation is a mistake: much may be learned by viewing them as they originally appeared–variably successful in the midst of a prolific, unstable, and rapidly changing theatre world.

So one argument is that we can best understand and appreciate masterful filmmaking against the background of normal practice. That seems right to me, but I think there are other good reasons to ask these questions.

For one thing, through bulk viewing of a lot of films, you may discover accomplished works. Many well-regarded films have gained their renown through accidents of release and critical reception. (His Girl Friday is one such.) Good films lurk in many crevices of film history.

I also think that the norms are of interest in themselves. They can show that craft practices harbor more variety than we sometimes think. Studying norms can also reveal offbeat possibilities that are sketched for future development. In Reinventing, I sometimes point to films, either obscure or awkwardly constructed or both, which anticipate trends to come. One example would be the strange, time-shifting exercise Repeat Performance (1947). It’s a Forties counterpart to Dangerous Corner (1934), a two-path plot looking toward more elaborate forking-path storytelling. It shows as well that rather unusual options can float around the edges of the variorum.

My quotations from Rob Hume come from correspondence and The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century, pp. ix and 129. Thanks to Rob for sharing the backstory of the book’s composition. Readers interested in his method can learn much more about it in his later study Reconstructing Contexts: The Aims and Principles of Archaeo-Historicism (Oxford, 1999).

This entry relies on a distinction among a film’s story world, its plot structure, and its narration. The idea is explained in this essay and applied to a single film in a blog entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. Plots with loops and forking paths are connected with the idea that “form is the new content” in films from the 1990s and after. I try to chart that ecosystem in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. See also this entry for a quick summary of early examples of multiple-draft plotting. For more on the virtues of Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, go here.

The following errors in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Oops.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Arrgh. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Doggone.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find goofs like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

Happy Death Day (2017).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Extra-credit reading and viewing

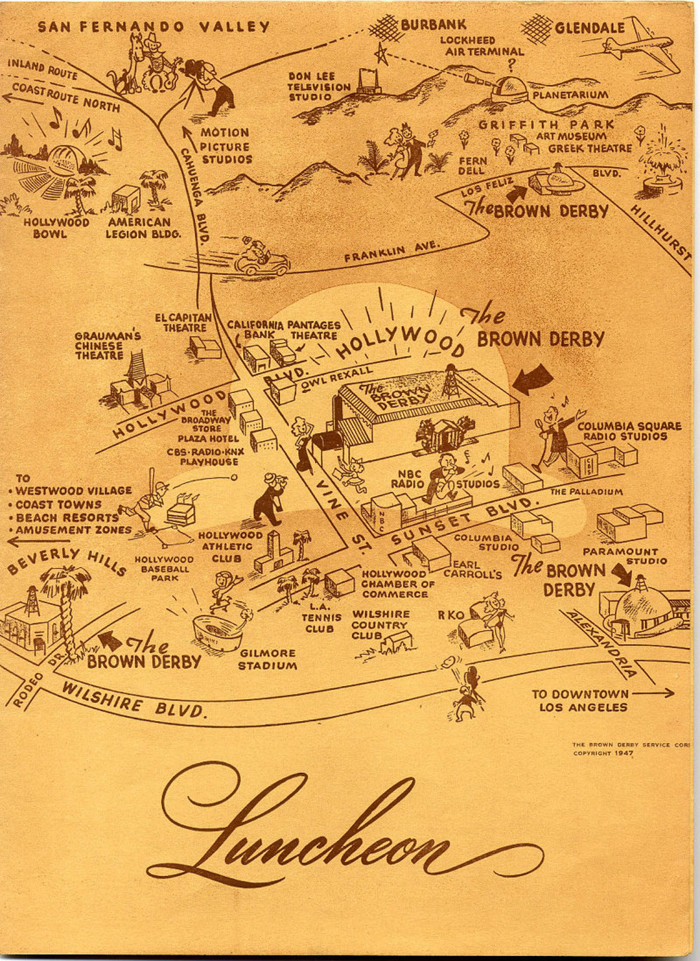

Brown Derby lunch menu.

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted at some point. I hope these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

Prosperity helps the movies

Lobby, Loew’s theatre, Rochester, New York, 1940.

Apart from studies of single creators, film historians have often sought to go macro, to tie the films to a broader cultural context. Elsewhere on this site I’ve criticized claims that films directly reflect national character, a zeitgeist, or a mood of the moment. There’s no denying that films bear the traces of the societies that make them. The question is how to understand that process—and how to explain it.

I vote for seeing cultural material as filtered through the constraints and choices of the institutions that filmmakers work in. Writers, directors, producers, and other participants (deliberately or unwittingly) pick out bits of cultural flotsam and reshape them. Buzzy ideas become plot premises. New technologies fulfill old functions. The newspaper-headline montages of the 1930s are replaced by shots of chyrons and cable news feeds today. Stereotypes become characters–sometimes unstereotypical ones. Not reflection, then, but refraction, with agents and social institutions recasting some trends that are out there.

But the macro level shapes cinema in another way: as a set of economic and technological preconditions. Around 1900, a society without a market economy and access to machine technology couldn’t have invented cinema. Before the smartphone, people living in certain countries lacked the infrastructure to access the Internet.

Historians sometimes distinguish between proximate causes—factors we can trace with some specificity—and distal causes, those more basic and pervasive preconditions that provide a background for the proximate causes. Along these lines, I wish I’d drawn on Robert J. Gordon’s 2016 masterwork, The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

Gordon proposes that the century from 1870 to 1970 saw five great clusters of technological innovations: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication systems. Most became feasible at the end of the nineteenth century, but they took some years to develop, starting to disseminate through the US population from 1920 onward. They peaked, he claims, by 1970 but a significant threshold was crossed around 1940.

Gordon proposes that the century from 1870 to 1970 saw five great clusters of technological innovations: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication systems. Most became feasible at the end of the nineteenth century, but they took some years to develop, starting to disseminate through the US population from 1920 onward. They peaked, he claims, by 1970 but a significant threshold was crossed around 1940.

Thanks to the Great Depression, FDR’s recovery scheme, and the start of World War II, both the American economy and most American lifestyles improved dramatically. Home electricity, refrigerators, washing machines, radios, telephones, central heating, cheap clothing, sanitation (no more horse droppings on Main Street), the rise of life expectancy, and the fall of infant mortality transformed everyday life. Most of these improvements were tied to the growth of cities. As Gordon puts it:

Except in the rural south, daily life for every American changed beyond recognition between 1870 and 1940. Urbanization brought fundamental change. The percentage of the population living in urban America—that is, towns or cities having more than 2,500 population—grew from 25 percent to 57 percent. By 1940, many fewer Americans were isolated on farms, far from urban civilization, culture, and information.

Reinventing Hollywood emphasized the boom in movie attendance that took off around 1940. Surely American migration to cities fed into this.

The growth of the film industry in the early and mid-Forties parallels a surge in everyday circumstances as well. By 1950, 92 percent of households had a motor vehicle. Penicillin and streptomycin had begun to drastically reduce instances of pneumonia, rheumatic fever, syphilis, and tuberculosis, while a new vaccine eliminated polio. And the rural population continued to dwindle, particularly when people were lured by the fat paychecks in war-related industries.

Did the diffusion of the major consumer technologies through American society directly affect the form and style of the films? No. Just as the struggle with the Axis didn’t demand flashback structure or voice-over narration, neither did the economic forces in society at large. But they did provide a basis for a leisure economy in which filmgoing could flourish, especially when the war cut down rival entertainments and provided more discretionary income. I discuss these processes at some length in Reinventing. Likewise, radio technology didn’t automatically create new narrational devices like voice-over and auditory flashbacks. Radio’s creative artists chose to develop specific techniques to achieve immediate ends. The rise in American standards of living is not a proximate cause but a powerful precondition for the 1940s surge in innovative storytelling. I could have signaled that factor more strongly.

Hanging out

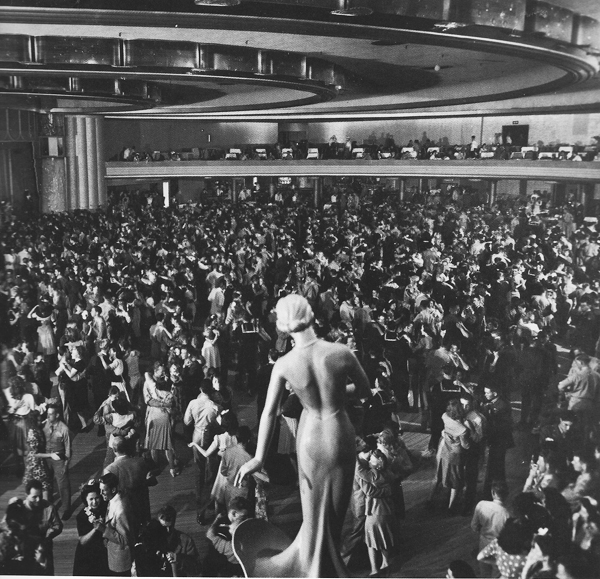

Hollywood Palladium Café.

If the bottom-up approach I tried out is to get anywhere, it needs to show that there’s a community of creators aware of what other folks are doing. Accordingly, the first chapter of Reinventing argues for the importance of Hollywood as bristling with social networks that facilitated cooperation within competition.

Formal organizations, which Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I traced out in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, include professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. These served as clearing-houses for filmmaking information. Reinventing adds in the more informal ties among personnel on the job or outside work hours (partying, playing cards or polo). In that era of loanouts and independent production, people who socialized might wind up working together.

I mention a few Hollywood hangouts, but now I wish I’d done more with the night spots that sprang up in the 1930s, most notably the Hollywood Derby, the Cocoanut Grove, and the Trocadero.

Most of the watering holes lingered into the Forties, when new attractions like Ciro’s and the Mocambo were added to the list. There were some more risqué ones, like Club Zombie and Florentine Gardens, which advertised topless/ bottomless performers. And there was the vast Palladium café, with a dance floor that could accommodate 7500 people.

These and many more venues are featured in magnificent photos in Jim Heiman’s Out with the Stars: Hollywood Nightlife in the Golden Era. Yes, everybody is shown smoking cigarettes.

I did edge into this area by discussing Breakfast in Hollywood (1946) as a network narrative. It features Bonita Granville, Zasu Pitts, Spike Jones, Nat King Cole, Hedda Hopper, and, I’m told, the mothers of Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford. The movie was a spinoff of a current radio show that broadcast from Sardi’s before moving to a dedicated venue on Vine Street. An enormous sign promised “Glorified Ham and Eggs from Pan to Mouth.”

The minimal switcheroo

Reinventing Hollywood surveys flashbacks, subjectivity, voice-over, ellipsis, multiple-protagonist plots, and other techniques. They were taken up widely and explored in various directions.

But they weren’t brand-new. Apart from voice-over, of course, these storytelling strategies appeared fairly often in the silent era. And although the 1930s largely swerved away from these strategies, they did pop up occasionally. I discussed several examples, such as The Power and the Glory (1933), The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), Peter Ibbetson (1935), and the crazed Poverty Row item The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

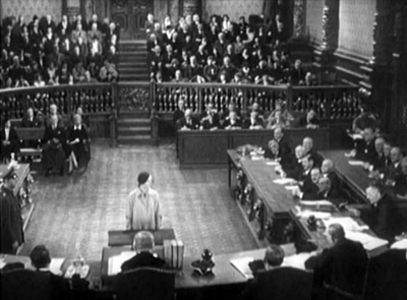

Tom Gunning reminded me of another important precursor. Confession (1937), a Warners melodrama starring Kay Francis, tells of a young woman becoming the prey of a suave but rapacious composer. When she leaves a supper club with him, he’s shot by the woman who has just performed a song. In the singer’s trial, she reveals that he seduced and abandoned her and that the young woman he tried to seduce is her daughter. The court goes fairly easy on her.

The tale is told through some devices that would proliferate in the 1940s. Voice-over monologue to let us in on a character’s thoughts? Check, although it’s very minimal. Flashback to illustrate trial testimony? Check, although that was already a fairly common option from the silent era onward. And a replay of events that show us an event from different viewpoints? Check, although another trial drama, the RKO Ann Harding vehicle The Witness Chair (1936) had pursued the same strategy. (It can be found as far back as The Woman Under Oath (1919), as discussed in an earlier entry.)

What makes Confession more interesting, as Tom also told me, is that it’s a maniacally close remake of Willi Forst’s Mazurka (1935). Here Pola Negri plays the avenging discarded lover. Joe May was a very talented director, but in Confession, he was content to copy the original scene for scene, and sometimes shot for shot. A portion of the German version’s first shot is re-used in the beginning of the American film.

The courtroom is one of several sets that are more or less replicated. Again, the Mazurka shot is first.

Both versions include a replay of an earlier scene. In the first instance, the daughter is unaware that her mother hovers in the hall outside. In the replay, we’re attached to the mother watching the young woman with her adopted mother. The parallel Mazurka sequences are on the top, the Confession ones below.

May’s remake supports a couple of points I made in the book. One source of Hollywood’s 1940s narrative ambitions was foreign cinema. French, German, and British films were exploring these techniques in the 1930s, and some relevant titles got exported to the US. A few were remade, with The Long Night (1947), based on Carné’s Le Jour se lève (1939), being one of the most famous. At the same time, some European directors, like May, started working in Hollywood. Julien Duvivier, for example, leaped into the new US trends with Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943).

Hollywood endlessly recycles material, as the new Star Is Born shows. Remakes weren’t as common then as they are now, but they did exist. We might see them as part of the process that includes the switcheroo, the habit of varying an existing premise or gimmick with a change that makes the thing look fresh. I suppose the most famous switcheroo comes in His Girl Friday (1940), where the male protagonist of The Front Page (1931) becomes a woman. Neatly, the name Hildy Johnson works both ways. Even Lydia can be seen as a switcheroo on Duvivier’s own Carnet de bal (1937). Everything, as we know, is grist for the Hollywood mill.

Most broadly, popular entertainment exemplifies what I call the variorum impulse, the urge to tweak or twist existing materials and devices. The aim is to produce something new that’s at once novel and familiar. More on the Variorum in a later entry.

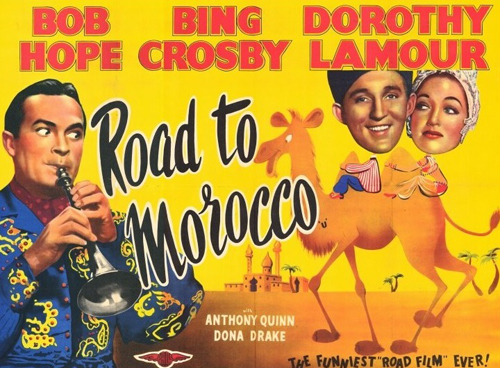

Bing and Bob

I’ve had reason to praise Gary Giddins elsewhere on this site, but I never got around to talking about the wonderful first volume of his biography of Bing Crosby. Now he’s come up with Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star: The War Years 1940-1946. Of course he deals with the musical career in definitive fashion, but just as important for me is his in-depth coverage of Der Bingle’s movies.

Reinventing, alas, devotes no space to Going My Way (1944), but after reading Giddins’ fifty pages on the film’s production, with sharp excursions into McCarey’s working methods and the tug-of-war about billing in the credits, I wish I had. It’s of course an extraordinary movie, loosely plotted and irresistible in its gentle momentum.

Reinventing, alas, devotes no space to Going My Way (1944), but after reading Giddins’ fifty pages on the film’s production, with sharp excursions into McCarey’s working methods and the tug-of-war about billing in the credits, I wish I had. It’s of course an extraordinary movie, loosely plotted and irresistible in its gentle momentum.

McCarey sold Crosby on the part as if he were peddling a modern High Concept project: “You’re going to play a hep priest.” Giddins carefully traces how the film took the country by storm and led to Crosby’s new, extraordinarily powerful contract with Paramount.

Bing enters my book in Chapter 11, as partner to Bob Hope in the zany Road films. These, along with other Hope vehicles, exemplify for me the acute movie-consciousness we find throughout the 1940s. Of course silent films and early talkies were often set among moviemakers (one of my favorites is Boy Meets Girl, 1938). But the theme shifted into higher gear in the 1940s and early 1950s, when we got films that exhumed Hollywood’s history (The Perils of Pauline, 1947; Singin’ in the Rain, 1952) and comic films that made fun of cinematic conventions. The latter is most wildly illustrated in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), but we get comparable cinematic in-jokes in the Road movies.

Giddins leads us behind the scenes, showing how the Road scripts, tentatively approved by the Breen Office, would get pulled apart during shooting and naughty bits of impromptu got shoved in in.

The writers aimed not only to make scripts funny but also to bamboozle censors. As Bing and Bob crisscrossed the set between takes, like fighters going to their corners, they would receive whispered zingers from personal gagmen, each star looking to unbalance the other; the constant comic rigor roused players and crew. Breen had no knowledge of the ad libs or how scenes would play.

Giddins is constantly throwing crosslights on these films. He shows, for instance, that the “high-velocity raillery” of The Road to Zanzibar (1941) owes something to producer Paul Jones, who had worked on Preston Sturges’ comedies. “The pace of the dialogue between crooner and comedian is impeccable, unforced, and funnier than the actual lines.”

To greater or lesser degree Giddins plumbs all the fourteen films Crosby made in these years, weaving them into the spectacular radio, touring, and recording career of one of the most popular stars in American entertainment. There’s plenty of sadness to go around too.

I could go on and on, as you know. After I finished the book I discovered George S. Kaufman’s 1945 play Hollywood Pinafore; or, The Lad Who Loved a Salary. It uses Arthur Sullivan’s score for H.M.S. Pinafore to mock the movie capital. Here’s a sample featuring the gossip columnist Louhedda:

Somehow all the weekly checks/definitely hinge on sex./ One man fills another’s shoes./Hard to tell whose baby’s whose./ Many autographs annoy/ Ella Raines and Myrna Loy./Goldwyn claims that all our ills/ Can be traced to double bills.

Et cetera. A bit labored, but cute.

Next time: Reinventing Hollywood and Happy Death Day 2U.

Thanks to Tom Gunning, Dan Morgan, Ally Nadia Field, Jim Lastra, Richard Neer, Jim Chandler, Mike Phillips, and Gary Kafer, as well as those who attended my lectures at the University of Chicago in January.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Yow.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. What a brain fart. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Sad!

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

UChi marketing guru Levi Stahl tweets: David Bordwell stops by the office but refuses to pose with his own book unless you also let him include Richard Stark’s Parker novels in the picture. It’s as close as I’ll get to greatness.

Oscar’s siren song: The return: A guest post by Jeff Smith

A Star Is Born.

As you probably know, Jeff Smith has been our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our Criterion Channel series “Observations on Film Art.” For the last few years (here and here and here), Jeff has offered his thoughts on the Academy’s music nominees. This time around, he concentrates on the songs.

Here’s a brief preview of the Best Original Song category in this year’s Academy Awards. I also include a prediction for this year’s winner. Of course, I’d be the first to admit I don’t even win my own Oscar pool. So you’ll want to take that into account before making any wagers.

A good old-fashioned tune

Mary Poppins.

The Academy has a long history of nominating songs from live action and animated musicals. This year is no exception.

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” from Mary Poppins Returns fits that bill, giving Disney a third straight nomination in this category. (“Remember Me” from Coco and “How Far You’ll Go” from Moana are the others.) Like the Sherman Brothers, who wrote songs for the original Mary Poppins, Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman derived inspiration from British Music Hall.

In fact, although actor Lin-Manuel Miranda insisted that he didn’t want his character to sound like Hamilton, Shaiman and Wittman wrote a patter section of “A Cover is Not a Book” for him, enabling Miranda to show off his unique skill set. With its tricky wordplay and fast pace, the classic patter song is a forerunner of the rhymes spat by rap and hip-hop artists. As Shaiman noted, “So we got very lucky there because we didn’t want to feel like we were pandering to the audience, to supply Lin with rap that would seem anachronistic.”

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” sits on the opposite side of the musical spectrum as a soft, mid-tempo ballad scored for strings and winds. Fans of the original Mary Poppins will note that it bears more than a faint resemblance to “Stay Awake.” Both songs are sung to the Banks children at bedtime in an effort to inveigle them to sleep. Whereas “Stay Awake” shows the über-Nanny using reverse psychology, “The Place Where the Lost Things Go” is a paean to memory, loss, and grief. The children’s mother has recently died and they further risk losing their beloved house. Mary Poppins reassures the children that they will be reunited one day with all their loved ones and that, in the meantime, their mother will forever have a place in their hearts.

The number is beautifully sung by Emily Blunt and it captures the sense of melancholy that gives Mary Poppins Returns its emotional heft. Still, it seems like a long-shot to take home the award. I admire Marc Shaiman’s work. He has written some absolutely iconic scores in the past, like The American President. And I’d love to see him recognized this Sunday, even if it is just for his phenomenal work on South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut. But I fear that an Oscar statuette with his name engraved upon it is also in the place where the lost things go.

When corn meets pone

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

The second nominee is David Rawlings and Gillian Welch’s “When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings.” It appears in the comically violent opening story of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. It is sung as a duet by the titular character and the Kid, a mysterious gunslinger dressed in black. Buster has just been shot dead in a duel. In the song, the Kid imparts some lessons learned from his short, rugged life as a cowboy with Buster chiming in to provide harmony. Kid’s grimly acknowledges that he will suffer the same fate as Buster. It is just a matter of time.

Rawlings and Welch are long-time collaborators, having worked together on the former’s debut album. Rawlings has also produced albums by Welch and by Willie Watson, who plays the Kid. Adding to the sense of family reunion is the fact that Welch provided the voice of one of the Sirens in O Brother Where Art Thou? Among those enchanted by the Sirens? You guessed it – Tim Blake Nelson, who plays Buster.

In an interview in Variety, Welch describes the absurdity of the original pitch the Coens made to her and Rawlings:

It was a pretty straightforward thing: “Well, we need a song for when two singing cowboys gun it out, and then they have to do a duet with one of ‘em dead. You think you can do that?” “Yeah, I think we can do that,” she laughs.

In crafting the song, Rawlings and Welch pull off a rather neat trick. They’ve created something evocative of the “singing cowboy” films that inspired the first segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Yet is also connects with a larger tradition of mournful ballads that are part of folk and country music history. A lilting Texas waltz, the number is sparsely orchestrated, relying largely on guitar, harmonica, and vocals. The lyrics also make reference to a “bindling sheet.” As Welch noted, the word “bindling” was something she and Rawlings made up as a gesture toward the Coens’ fondness for anachronistic language. Yet it also works as a clever allusion to the “white linen” that is wrapped around a dying cowboy’s body in “Streets of Laredo.”

As was the case with Mary Poppins Returns, this song perfectly blends music and narrative, beautifully capturing the darkly humorous sensibility characterizing the Coens’ career. The lyrics are solemn, but Tim Blake Nelson’s yodeling lightens the tone to keep it from seeming maudlin. If I had a vote to cast, this is where I’d put it. Yet my gut tells me that the Academy’s beacon will shine on one of the other nominees.

A song for one of the Supremes

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The third nominee, “I’ll Fight,” was written by Diane Warren, a longtime Academy favorite. The song represents Warren’s tenth nomination, but she has never taken home top honors. This year, in an ironic twist, she may lose out to former co-writer Lady Gaga. (The two were nominated for “Til It Happens to You” in The Hunting Ground.) Warren admits that “I’ll Fight” is another of her “call to arms” songs as she has turned more of her energies toward films that support social causes.

One can easily make a solid prima facie case for “I’ll Fight” as the song to beat. It features a strong, soaring vocal performance by Jennifer Hudson, a previous Oscar winner for Dreamgirls.

Warren’s melody and lyric capture the inspirational vibe that is found in several previous winners, most recently “Glory” from Selma. And, of course, Warren herself seems long overdue.

Even so, “I’ll Fight” has a number of things working against it. It is featured in a documentary, and documentaries usually don’t get the exposure of more mainstream releases. It appears over The RBG’s closing credits, which mostly restricts the song to a summative function. And, unlike “All the Stars” and “Shallow,” the song failed to chart, an indication that it didn’t get much exposure in the music marketplace. I feel confident that Warren’s opportunity to make an acceptance speech will come someday. But on Oscar night, she’ll once again be the “bridesmaid” rather than the “bride.”

The battle of the titans

Black Panther.

For me, the race comes down to the remaining two nominees: “All the Stars” from Black Panther and “Shallow” from A Star is Born. Both tracks have gotten extraordinary exposure outside the films in which they appeared. The former was a chart hit in 25 countries, garnering steady radio airplay and thousands of streams and downloads in the process. The latter arguably did even better, charting in 40 countries, selling nearly 600,000 downloads and accruing almost 150 million streams. Both songs are fueled by star power: hip-hop sensation Kendrick Lamar for “All the Stars” and pop diva Lady Gaga for “Shallow.”

Lamar has just the right profile to woo Academy voters, even those in the music branch for whom “big beatz” and “flow” seem like foreign concepts. He has won thirteen Grammy Awards as well as the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, becoming the first artist to do so from outside the domains of classical and jazz music. Billboard even compared Lamar to Shakespeare.

Although some music critics argue that “All the Stars” is not entirely typical of Lamar’s and SZA’s respective styles, it does fit beautifully with the overall vibe of Ryan Coogler’s pathbreaking film. The song begins with loping rhythms, electronic textures, and auto-tuned vocals. When Lamar drops the beat in the chorus, “All the Stars” gains intensity thanks to the layering of additional synthesizers and SZA’s melismatic topline.

The overall effect is one that neatly draws together Black Panther’s principal settings, being equal parts Wakanda and Oakland. The tension in the lyrics between the sung choruses and Lamar’s linguistic turns also restages the film’s central conflict: Prince T’Challah’s policy of peaceful co-existence vs. Killmonger’s thirst for violent world revolution. Appearing over the end credits, the number also works brilliantly with the shifting lines, shapes, and textures of the sequence’s graceful animation.

Lady Gaga, of course, supplies “Shallow” with its vocal fireworks. But she shares her nomination with three other collaborators, all of whom cut pretty large figures in the world of popular music.

Chief among them is superproducer Mark Ronson, who twirled the knobs on Gaga’s fifth album, Joanne in 2016. Ronson is perhaps best known for his smash hit, “Uptown Funk.” Yet, Ronson had already won three Grammy’s for his production of Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black long before he gave us his Bruno Mars earworm. Besides his production work for Gaga, Winehouse, and Mars, Ronson has collaborated with a “who’s who” of current stars and pop music legends: Adele, Lily Allen, Miley Cyrus, Kaiser Chiefs, Chance the Rapper, Janelle Monae, Duran Duran, Nile Rodgers, and Paul McCartney.

One of Ronson’s other songwriting partners, Anthony Rossomondo, shares the nomination for “Shallow.” Rossomondo is a guitarist and trumpet player who was a founding member of Dirty Pretty Things and toured with the Libertines as Pete Doherty’s replacement. Fans of British television might also remember Rossomondo as Pete Neon in The Mighty Boosh, the surrealist comedy series about a pair of failed musicians working in an alien shaman’s magic shop.

Rounding out the quartet of songwriters is Andrew Wyatt, still another songwriting partner of both Ronson and Gaga, who also penned tunes for Mars, Lil’ Wayne, Beck, Florence + the Machine, and former Oasis bad boy, Liam Gallagher. Wyatt also has previous experience writing for film. He composed four songs for the Hugh Grant/Drew Barrymore romantic comedy, Music and Lyrics, including the wonderful pastiche of eighties New Wave, “PoP! Goes My Heart.”

With so much musical talent on board, it is hard to see how “Shallow” could miss. Yet the song’s many virtues are enhanced by its perfect placement in the story. It was a lot to expect that one song could deliver something that a) pays off the romantic sparks of Ally and Jackson’s initial flirtation; b) signifies Ally’s leap of faith as she returns to the stage to complete Jackson’s arrangement of her song; and c) convince the audience that Ally could legitimately be the proverbial overnight sensation of the film’s title. “Shallow” delivers on all that and more.

The song begins with Jackson singing, “Tell me something, girl.” The first verse is sparely arranged for just voice and acoustic guitar. Jackson essentially baits Ally into claiming a spotlight he believes is rightfully hers. When Ally comes on stage, she begins the second verse in the lower part of her vocal register, adding a husky sensuality that captures the slow-burn of the couple’s simmering passions. Piano, violin, and pedal steel guitar slightly thicken the arrangement while maintaining the relatively soft dynamic level. An octave leap leads into the chorus, which Ally belts out with newfound confidence.

The lyrics serve as a metaphor for the character’s personal journey, her willingness to take the emotional and professional risks that Jackson had encouraged. This is Ally’s moment of self-realization. Yet it also foreshadows the relationship’s failure by previewing a future in which her stardom will overtake his.

This is followed by Jackson and Ally finally harmonizing together on the phrase, “In the shallow, the sha-ha-low.” Their voices blend, suggesting the consummation of their romantic connection onstage, if not yet in bed. Ally follows with a kind of vocal cadenza. No longer bound by lyrics, she sets free the “yargh” in her voice that rock critic Greil Marcus famously ascribed to Van Morrison’s Irish soul.

The addition of drums and bass enhance the big crescendo that leads into the final chorus. Jackson joins Ally at her microphone and the two finish the song with a final duet. The song is in G major, but ends on an E minor chord, another subtle hint of the sadness that ultimately consumes couple’s relationship.

As an Oscar nominee, “Shallow” has a lot to offer. It is a duet between a major movie star and a major star of the recording industry. It not only pays off a previous dangling cause, but also foreshadows later plot developments. Best of all, it takes the audience on an emotional journey that symbolizes the characters’ story arcs in microcosm. If the snatch of “Shallow” heard in the A Star is Born trailer proved surprisingly meme-worthy, the full performance of it in the film was indelible. Moreover, in a cheeky bit of self-mythologization, it invites viewers to consider “Joanne,” the flesh-and-blood being that sits just behind the Gaga mask.

Prediction: “Shallow”

I likely tipped my hand earlier, but I fully expect Lady Gaga and company to add Oscar to the Grammy and Golden Globe they’ve already won. If that happens, I’ll be content with the result, even if the memory of Tim Blake Nelson and Willie Watson’s duet tickles me every time I think of it. I’ve enjoyed Mark Ronson and Lady Gaga’s music for more than a decade. And if nothing else, an Oscar for Andrew Wyatt will balance the scales of justice. Back in 2008, I felt Wyatt was robbed when he failed to secure a nomination for a song Billboard called “the greatest fake 80s song of all time.” Well, if I see Wyatt clutching an Oscar come Sunday, you’ll hear a little PoP! go in my heart.

For an alternate take on this year’s music nominees, a real pop star from the eighties, Thomas Dolby, offers his perspective here. A report on a panel discussion at the Los Angeles Film School featuring several of the nominees can be found here.

Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman talk about their work on Mary Poppins Returns here and here.

Gillian Welch discusses working with the Coen Brothers on The Ballad of Buster Scruggs here and here.

Diane Warren offers her perspective on writing “empowerment anthems” here and here. A deep dive into Warren’s career can be found on a Hollywood Reporter podcast featuring the 10-time Oscar nominee.

Finally, much ink has been spilled about the process of writing “Shallow” for A Star is Born. You can read more here and here and here and here.

Jeff Smith has provided us many guest blogs related to film music, most recently his discussion of the score for True Stories.

Music and Lyrics (2007).

The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master class

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

DB here:

Craft isn’t everything in art, but it counts for a lot. Even when you’re going against tradition, you can’t just willy-nilly do whatever. You need to create a counter-craft (as Bresson, Brakhage, Ozu, and others showed us). Reviewers, in their urge to thump out quick judgments, often don’t address craft practice directly. So if we simply talk of the Coens’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs as a grim, occasionally grotesque and zany take on Western conventions, we’re apt to take for granted just what a trim, absorbing piece of sheer filmmaking it is.

It’s worth attuning ourselves to what Adam Gopnik called his collection of Robert Hughes’ writings: The Spectacle of Skill. Paying attention to that enhances our appreciation for what filmmakers accomplish, and maybe it can nudge aspiring filmmakers to consider things to try.

So, herewith a quick analysis of the very beginning of the film’s second episode. The whole piece is not as audacious as the title episode, and not as poignant as “Meal Ticket” or “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” It’s more of a light interlude. But we shouldn’t let its shaggy-dog payoff (“Your first time?”) make us think there’s anything slapdash about it.

There follow spoilers.

All the meanness in the Used-To-Be

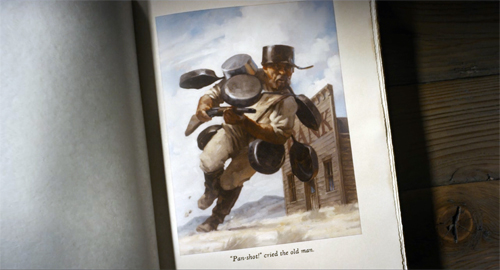

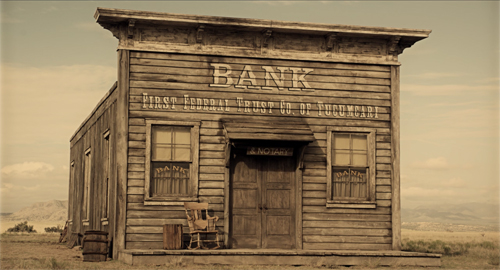

In the book that frames each tale, this one is called “Near Algodones.” As in the other episodes, an illustration prepares us for something we’ll see in the scene. The caption reads: “Pan-shot!” cried the old man.

Lesson 1: Make everything clear and simple, except what you want to suppress.

A master shot gives us the elemental situation: A bank, a well, and a lone rider with his horse.

These are the central components of the sequence. The isolation of the bank makes it a plausible target for a holdup. The geography will become important in the second stretch of the scene, while the well will provide cover to the Cowboy. His horse will prove notably reluctant to move.

Lesson 2: Attach the narration to a single character.

Throughout this episode, we’re “with” the Cowboy, not always through exact optical POV but more generally: our range of knowledge of the unfolding situation approximates his. This sort of restriction arouses curiosity (what’s going on in the bank?), as well as suspense and surprise (as we’ll see).

Lesson 3: Motivate new shots by offscreen sound.

Attachment to the Cowboy is reinforced by the play of his attention. Over the Leone-esque close-up we hear a creak. This motivates a cut to the bank’s hanging sign. As we hear a thump, he shifts his eyes; we see it’s caused by the bucket bumping against the well.

Lesson 4: Delay when you can.

Attachment doesn’t mean immersion. Instead of a shot from the Cowboy’s POV as he’s entering the bank, we get him pausing to size up the scene.

Only then do we get a shot of the bare bank and the teller’s windows, which (thanks to a wide-angle lens) seem impossibly far away.

Lesson 5: Let expectations go to work.

The holdup scenario, a convention of Westerns, is surely hovering in many viewer’s minds. When the Cowboy advances, we wait to see if our expectations pay off. You get suspense simply by having your actor move forward; what could be more economical?

Lesson 6: Prepare for later shots.

The tracking shot of the Cowboy’s boots and spurs might seem mere decoration, but it further delays his arrival at the window and sets up an important shot to come.

Lesson 7: Scale your shots according to the information they present.

Reverse shots are the workhorses of mainstream storytelling cinema. They are vehicles for character interaction, either based in dialogue or just the exchange of glances. The over-the-shoulder (OTS) version specifies the spaces the characters occupy, typically in a conversation. OTS framings also serve as a transition to closer views. Here the Cowboy’s goal in the scene is to learn how fortified the bank is against robbery.

After the opening stretch of purely visual storytelling, dialogue takes over. For us to grasp it better, the OTS framings give way to singles, which enlarge the teller’s performance and the Cowboy’s reactions.

The geezer’s chatter joins the motif of flowery monologues and eloquent bafflegab we’ll encounter throughout the film. The framing also lets us enjoy the performance, which suggests that this scatterbrain might be an easy mark. He does, however, mention that he has put down one attempted robber and “shredded the legs” of another.

The climax of the exchange is the Cowboy’s drawing his pistol and the teller’s explanation that he has to stoop to get “the large denominations.” The result is more shot-scale calibration: We need a single to see the gun looming (an OTS wouldn’t be as punchy), but the reverse shot can be OTS because we need to see how the teller’s stooping maneuver is concealed from the Cowboy. We are still attached to him and what he knows–or doesn’t know.

Another benefit: as variants of framings we’ve seen before, these let us quickly grasp what’s new in them (brandishing the pistol, ducking down).

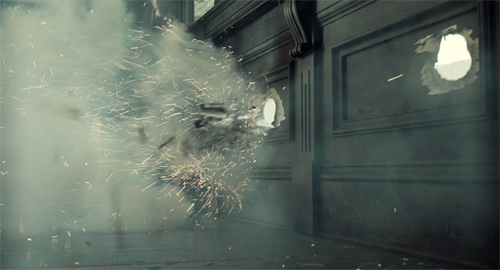

Lesson 8: Use a cut, a crisp gesture, or a discrete sound to arrest attention.

Actually, the next shot does all three. The Cowboy tries to peer over the till, and a shot shows him taking a step forward as we hear a click. This framing pays off the shot of striding boots we saw in Lesson 6.

Within the same shot, the front of the teller’s window is blasted open. The Cowboy jumps sideways as another hole explodes, then another.

We’re back to visual storytelling. Now we understand why the teller has “shredded the legs” of another would-be robber. When the debris clears, a camera tilt shows that the Cowboy has sprung to the counter.

A mini-spectacle of skill: Handling the three blasts and the Cowboy’s evasion in a single percussive shot.

Lesson 9: Stagger the reveals.

Alexander Payne once remarked: “Whenever you can do a reveal, do it.” Here we have a suite of reveals, but they’re handled in a simple, cogent way.

When the Cowboy crouches on the counter, we have several questions. Is the teller going to fight? What created the blasts? And will the Cowboy get to the money?

These questions are answered, purely pictorially, in the shots to come. First, from his perch the Cowboy sees the partly open door. The teller has escaped, but because we’re restricted to the Cowboy’s perspective, we don’t know where he’s gone.

Just as one concise shot showed us the gunblasts and the Cowboy’s leap to the counter, now his descent and landing, followed in a single tilt, reveals the teller’s infernal machine: a row of shotguns poised to fire.

Another director would have devoted a POV shot to this revelation, but here it’s provided without fuss or forcing, as we follow the Cowboy’s crouch. He barely reacts and smoothly sets about finding the money. He grabs it in a single crisp close-up. And another cut takes us to the doorway, as the Cowboy hopes a view outside will reveal where the teller has gone.

Once more a POV is recruited, but it shows how much our protagonist doesn’t know.

The elements we were given at the start–bank, well, horse–are laid out again, from the opposite angle. Thanks to the clarity of presentation, we fully understand that the old teller is hiding somewhere (probably with his lauded scattergun) and the Cowboy has to make a run for it. But to where?

There are other things to talk about here, such as the homages to Leone (the mention of Tucumcari from For a Few Dollars More, the creaking of the sign recalling Once Upon a Time in the West‘s operatic opening). Perhaps the device of the book owes something to William S. and Mary Hart’s Pinto Ben (1919).

But we’re so used to considering the Coens pasticheurs that these allusions don’t interest me as much as the compact finesse of their style.

The rest of this scene will depend on reworking the narrative, auditory, and pictorial elements we’ve already encountered. You could go through that, and indeed the rest of the film, and trace the artisanal precision on display. (Let alone the sheer boldness of certain depth shots.) And the Coens are expert at using visual ideas for humor, as in the later scene when the Cowboy’s horse, browsing for more grass to nibble, stretches his noose-rope to the limit (see top image).

But I think I’ve said enough to indicate how rich an apparently straightforward handling can be. When we speak of careful pacing; when we think of building a scene; when we think of a movie that’s easy and graceful to follow, what Otis Ferguson called “a smooth clear line”–this is what we’re talking about.

There’s plenty of spectacle here, what with landscapes and gun blasts, but there’s another sort of spectacle as well: the quiet virtuosity of craft. You don’t see it that often these days, so when we encounter it, we should acknowledge it.

For another study of the Coens’ technique, see Jim Emerson on No Country for Old Men.

Other blog entries celebrate this sort of precision. See, for example, this analysis of Panic in the Streets, or the mind-boggling visual engineering of Fritz Lang (here and here). Otis Ferguson’s ideas about smooth cinematic storytelling are discussed in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

My first impressions of Scruggs, after seeing a magnificent big-screen presentation in Venice, are here. Netflix and Annapurna are to be congratulated for backing this movie, but it really deserves a wider theatrical release than it got. At least, please give us a Blu-Ray!

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).