Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

The wayward charms of Cinerama

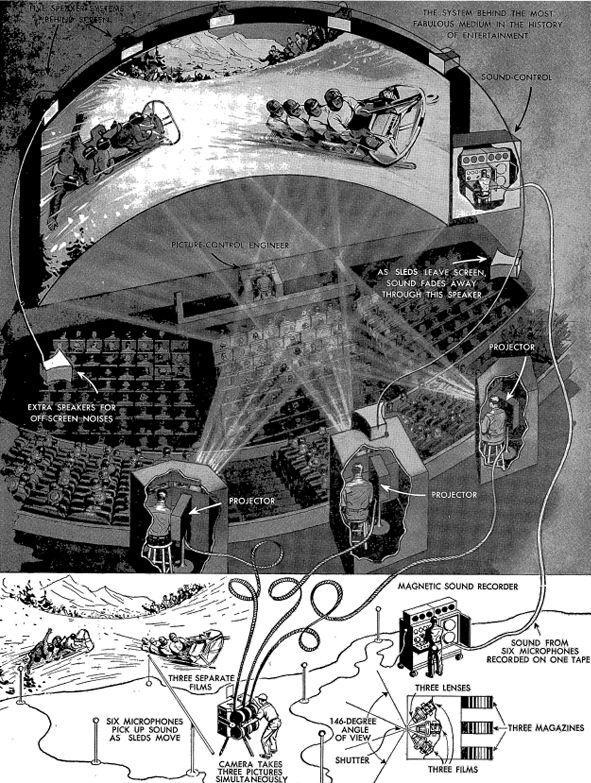

From Cinerama Holiday souvenir book, 1955.

DB here:

Two slumbering potential giants stirred in the last months of 1952, and as 1953 got underway the motion picture industry was faced with the greatest upheaval since sound films revolutionized the industry nearly 26 years ago.

Winfield Andrus, “3-D Finding Its Place,” The 1953 Film Daily Yearbook (New York 1953), 147.

Andrus was referring to 3D and to Cinerama, two technical marvels that promised to revive American filmgoing in the postwar era. In the short term, that didn’t happen. 3D died quickly, and Cinerama remained a novelty before expiring in 1962. But eventually 3D became viable, as the last decade has shown. Moreover, Cinerama’s impact was felt throughout the 1950s. Studios competed with it by introducing other widescreen formats, stereophonic sound, and extravagant roadshow productions. Cinerama, people are starting to point out, was a prototype of what Imax has become. Just as we’re now more interested in classic 3D (see my entry on the reissued Dial M for Murder), we ought to take another look at Cinerama in its more or less pure state.

Devoted aficionados like John Harvey of the New Neon Cinema in Dayton have kept Cinerama alive in theatres, and the challenge has been taken up by other venues. One of the most passionate advocates has been David Frohmaier, whose documentary Cinerama Adventure graced our Wisconsin Film Festival some years back. That documentary showed up on the 2008 DVD release of How the West Was Won, and it’s an essential, affectionate introduction to this most ungainly of film formats.

Now Frohmaier has brought us the 1952 film that started it all. This Is Cinerama has just been released by Flicker Alley, one of our most exacting and adventurous DVD publishers. The whole meticulous package–the film itself, presented in Frohmaier’s Smilebox display, along with an abundance of extras—offers a good chance to think about what Cinerama amounted to.

Cinerama had its ups and downs over a decade. Control of the technology and the venues shifted unpredictably, as did the revenues and profits. But I think that Cinerama’s unique accomplishment lies partly in its unintended consequences. Seeking to become the most realistic form of cinema yet known, Cinerama demonstrates how enjoyably un-realistic, even surrealistic, movies can be.

One hell of a demo

When This Is Cinerama opened at the Broadway Theatre in Manhattan on 30 September 1952, it presented itself as the ultimate package of new entertainment technologies. It was of course in color, which was still something of a rarity in motion pictures. It used stereophonic sound, with five speakers behind the screen and two in the auditorium. The screen itself was a wonder: it was seventy-five feet wide and about 23 feet high, bent in a 146-degree arc. That made the display span fifty feet. Later, some screens would be nearly a hundred feet long and over thirty feet high.

All who saw the film felt that this was an immersive experience. The goal, claimed Cinerama’s inventor Fred Waller, was to approximate what our eyes take in, including peripheral vision. Indeed, Waller claimed that our sense of depth in the world and an image depended on peripheral information. Anyone who has been in a wraparound theme-park attraction can attest to the fact that an image stretching to the edges of sight can provide a pretty compelling illusion, especially if the images carry us forward. You can undergo this illusion in Disney’s Circle-Vision 360°.

Cinerama’s colossal screen size and deep curve dictated a new approach to image-making. No standard 35mm frame could fill such a wide display without losing resolution. The scale of the show demanded three projectors, each trained on one-third of the screen. The image became a triptych, with thin overlaps or “blend lines” demarcating the panels. Naturally, all three had to be exactly aligned and kept in strict synchronization. If one film reel lost frames through a mishap, for future shows projectionists snipped the corresponding frames out of the other two reels.

The projectors were initially housed in separate booths, with a projectionist in charge of each. A fourth booth was given to the sound mixer (off to the right side in the above diagram), who oversaw the multiple track playback at each performance. Yet another staff member was in charge of monitoring the whole performance. Interestingly, the projectors were said to be placed level with the screen, in order to avoid any keystoning distortions of the display. But the diagram above, along with the Cinerama displays I’ve seen, position the projectors fairly high in the auditorium.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

To gain resolution, each frame on the film strip used about twice the image area of conventional film. Surprisingly, the image area wasn’t much wider than normal film but it was 1 1/2 times the normal height (that is, 6 perforations high rather than the usual 4). To allow more frame space, the soundtrack was played on a separate magnetic film reel. The resulting images yielded very high resolution.

These sprawling images came from three cameras interlocked into a single bulky unit. The lenses were angled at 48 degrees to one another, turned inward to cross at a precise focal point. The camera lenses, all purpose-made, had a focal length of 27mm–another factor that would yield some striking pictorial effects. All three lenses shared a common shutter and had interlocked diaphragms to ensure comparable exposure. Because flicker would be disturbing on such a wide display, particularly on the edge panels, the film ran at 26 frames per second rather than the usual 24. The aspect ratio varied between 2.6:1 and 2.77:1.

This Is Cinerama was what we’d today call a demo. Lowell Thomas, one of the backers of the process, noted that if they’d told a story with actors, the emphasis would be taken off Cinerama itself, which was “a major event in the history of entertainment.” “The logical thing,” Thomas remarked, “was to make Cinerama the hero.”

The result was a travelogue (a word Thomas hated). After Thomas’ prologue, the film proper opens with the famous ride on a plunging rollercoaster. Then come episodes devoted to the canals of Venice, some church choral music, Scottish pipers, Viennese boy choristers, Spanish dancers, and an excerpt from Aida performed at La Scala. During the intermission Thomas inserts another demo, this time of the surround-sound effects. (We have to remember that stereophonic sound was a big novelty at that point; stereo LPs came later.) The bulk of the second part is spent at the Cypress Gardens leisure park, providing images of handsome men and women at play and climaxing in some exciting water-skiing. This is sort of double product placement–not only promoting the park but also water skis, another Fred Waller invention. The film ends with an awe-inspiring flight crisscrossing America, from New York and the Pentagon to the Golden Gate Bridge, and back to the rugged terrain of the West and Southwest.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

Party like it’s 1952

As a novelty, This Is Cinerama succeeded, running for over two years in New York. The system was installed in big-city theatres around the country. At a time when the average price of a movie ticket was $.46, the high-end seats for a Cinerama feature cost $2.80, or $24.34 in today’s currency. The Cinerama organization produced four more episodic travel-centered pictures: Cinerama Holiday (1955), The Seven Wonders of the World (1956), Search for Paradise (1957), and Cinerama South Sea Adventure (1958). Another picture made in a rival three-panel technology, Windjammer (1958), wound up in Cinerama venues as well. By 1957, Variety announced, the first three releases had grossed $60 million worldwide.

The problem was that on those grosses, profits came to only $6 million. Eighty percent of the box office take was used up in operation of the theatres.Morever, the complexity and cost of a Cinerama system meant that very few venues existed; by 1959, there were about twenty screens in the US and another eight or ten abroad, and not all were operating. In addition, overall US movie attendance was dropping, from about 47 million weekly in 1954 to 32 million in 1959.

New management succeeded in opening many more Cinerama theatres on a franchise basis, but the company needed fresh product as well. A coproduction deal was struck with MGM to use the process on fictional features. The results were The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) and How the West Was Won (London premiere, 1962; US release, 1963). To expand the audience, these films were also released in anamorphic widescreen to non-Cinerama venues.

Both films won large audiences, but they failed to make a profit. Soon the company’s theatres began exhibiting 70mm film releases under the Cinerama brand. The films were shown on curved screens, but with single-lens projection. The first of these releases was It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963); eventually even 2001: A Space Odyssey (1967) would be exhibited in “Cinerama.” In the course of these years, the company was acquired by Pacific Theatres, where it still resides. Classic triptych Cinerama was gone.

I never saw it in its prime.

I did see How the West in its original anamorphic release, and that has stayed with me for a couple of reasons. First, I was moved by it. It’s kitsch in many ways, but there are several exciting and touching scenes. Moreover, even as a squeaky-voiced teen I recognized something genuinely weird about the way it looked. Its imagery haunted me, though I didn’t have ways to understand them. Many years later, writing portions of a book that became The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I couldn’t watch any of the Cinerama travelogues in archives. I had to content myself with watching pink, cropped 16mm anamorphic copies of How the West Was Won. In all, it was very hard to get a sense of what the thing looked like (let alone sounded like).

Not until 2003 did I see both This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won in the three-panel format, during a conference on widescreen cinema held at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England. That experience was wonderful, and it left me wanting to study the films more closely.

Now I can, and you can too. David Strohmaier has devised a transformation that captures the shape of a Cinerama projection. He calls it the Smilebox. The Flicker Alley DVD of This Is Cinerama is in Smilebox, as you see from my Venetian image above. Warner Bros’ 2008 Blu-ray release of How the West Was Won provides both a Smilebox version and a wider-than-CinemaScope letterbox version.

Through painstaking restoration by Greg Kimble and others, the films look clean and bright. Digital cleanup has regularized the color values from panel to panel and nearly eliminated the blend lines. The result conforms to what the makers would surely have preferred–a greater sense of uniform tonality, light, and space across the frame than surviving Cinerama images have.

For anybody interested in the history of American cinema, the Flicker Alley DVD is essential. It provides a long-missing chapter in the development of widescreen filmmaking. This Is Cinerama is a documentary that is also a document of postwar American pride, of film technology, and of the movie business. But I think it represents even more. For the most part neither Smilebox nor digital restoration has removed the peculiarities that, perhaps perversely, fascinate me about this unique format.

Nice big image you got here. Be a shame if anything happened to it.

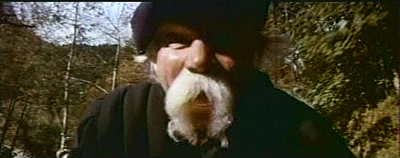

Cinerama camera in a mock covered wagon for How the West Was Won.

Like any picture-making process, Cinerama captures the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. Unusually in the history of cinema, it does it with a semicircular array of cameras. The images from those cameras are projected on a corresponding semicircular surface, in the hope that they will simulate not only the spatial layout in front of those three lenses but also the way the world looks to us.

Fred Waller thought that his invention provided greater realism, because our vision subtends a horizontal arc wider than that of conventional camera lenses. Fred fell a few degrees short, though. Claiming that we take in about 160 degrees, he thought that 146 degrees was a good approximation, but our visual field is actually a bit wider than 180 degrees. (Without turning our head, we can roll our eyes.) More important, though, is the assumption that a faithful image of the world should try to capture the curvature of the image as it passes through the cornea to the retina. We see a bowed world, many have claimed, so our pictures should present the way things look.

Yet there’s a difference between visual sensation and visual perception. Even if the light from the world hits our photoreceptors in a partial or distorted way, what we see is regular and unified. On our retinas, near things loom large and distant things look tiny, but we’ve evolved to adjust to the distortions in early stages of vision and see things in normal size. A person ten feet away is twice as large on our retina as somebody twenty feet off, but that’s not the way they look. We don’t see our retinal image, any more than we see the wildly misshapen image of the world projected to brain areas. The eye is a part of the brain, and the brain reworks the stimulus–cleans it, enhances it, corrects it, straightens it out, and gives it a stability that isn’t there in the raw input.

For the most part, normal camera lenses approximate the way the world looks to us after our brain has processed visual signals. Most images show straight-edged walls and sidewalks, railroad tracks meeting at the horizon, proportional human beings. When Cinerama or other nonstandard image-making technologies present distortions to our eyes, we take them for what they are: not “what we really see” but rather pictorial displays creating distinct effects of their own.

Hence the irregular appeals of Cinerama. Suppose we’re not interested in seeing the world as it registers on our sensory system. Suppose we’re interested in exploring uncommon pictorial effects. If we suppose all that, we can have the sort of fun watching Cinerama that we get from this 1877 picture by Caillebotte (Paris Street, Rainy Day), a virtuoso reworking of geometric space.

Take image sharpness. In the 2003 Bradford shows, I was overwhelmed by just how precisely distant objects registered. This was partly due to the greater resolution of a bigger image area, partly to the use of wide-angle lenses with breathtaking depth of field in brilliant sunlight. I can’t illustrate some of the most dazzling effects here, including the sight of a very distant bathing beauty racing through a crowd and up to the foreground in the Cypress Garden sequence of This Is Cinerama. But if you have a large home theatre monitor or projected display, you might be able to spot her. Here I’ll just mention how the farthest stretches of the famous roller-coaster stand out crisply, and in big-screen projection, the people in the far distance do too.

Such short-focal-length lenses distort the visual field in predictable ways. For one thing, they make horizontal lines bow upward or downward. For this reason, Cinerama DPs were at pains to keep the horizon near the center of the shot and to avoid or cover contours parallel to the horizon. Linus Rawling’s canoe oar bends disconcertingly in the central panel even before it hits the blend line and shoots off on its own.

Verticals can get distorted as well. On the edges of each panel, human figures can look bulged, pinched, or oddly torqued.

Cinerama’s triptych format complicates perspective effects by welding three wide-angle images together. When presenting built environments, often each panel displays its own distinct vanishing point–sometimes central, sometimes angular, sometimes both. The results recall the Caillebotte picture, all acute angles and avenues flung out to left and right.

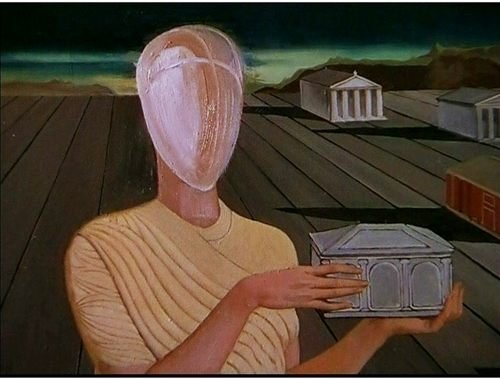

One cinematographer tells us that “special sets had to be built with curves and bends to rectify the false perspective inherent in three-camera systems.” But often we get contorted interiors. Dr. Caligari might feel at home in Lowell Thomas’ office.

The blend lines add their own constraints. From a distance, the Golden Gate looks very planar, but as our plane swoops nearer, the horizon remains flat while the bridge develops a couple of kinks.

For staged action, veteran cinematographer William Daniels warned that “We invariably consider the blend lines first, then plot and stage the action to suit the camera setup.” Most obviously, directors had to keep people away from the panel joins. We can see the unfortunate result in this image from This Is Cinerama. The gent on the far right is at once pinched and bulged, and the building in the B and C panels gets the Caillebotte treatment. Worse, a young Venetian man’s head on the blend line undergoes an unfortunate warping.

When a figure moves from panel to panel, the wide-angle distortions combine with the panel edges to create a faceted, almost cubistic space. Here’s the first anomaly I spotted when watching How the West Was Won as a kid in 1963.

As Linus is walking toward Mr. Prescott, James Stewart seems to stride diagonally forward a bit (in the A panel). After he pivots, he grows very large as he starts to walk straight (the B panel). , then stride diagonally into depth (the third panel). Each wide-angle lens makes people swell or shrink as they come to or from the camera, and with the creases supplied by the blend lines, scenes like this become attractively odd. With the panels ironed out, we see people taking strangely roundabout paths to one another.

The effect is even more noticeable in big action scenes, when horizontal movements that are really parallel seem to peel off from one another. During the Indian chase, the wagons are fleeing alongside one another, as a back-projection shows. But the more dynamic angle on the wagon teams creates an image that hits you like a cold shower.

To the audience in front of a curved screen, the movement in the second shot would have looked somewhat (but not entirely, I think) more linear. For us, we see a perspective we’ve never seen before, with wagons diverging from one another but neither getting smaller or larger. And how about the dizzy swerve that the pathway in panel C takes when it reappears in panel A?

The angled-triptych format obliged actors to adjust their performances in counterintuitive ways. “An actor in a side panel,” wrote Daniels, “cannot look directly at one in the center panel when speaking to him, but must cheat a little–direct his eyes a little behind the one in the center.” Here’s an example from The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm that stands out when seen in the flat format. Wilhelm is speaking to Greta from the C panel, but it seems that Laurence Harvey didn’t cheat his body quite enough. He seems to be speaking past her, an effect not helped by the disproportionate size of his body.

This Is Cinerama is obsessed with centering its action, but sometimes the center seems strangely off-kilter. With the water-skiing women shown earlier, the three cameras create a sort of hollow viewing station. Why do the flanking skiiers seem to be moving at angles to the central trio? Why do the ropes of the central skiiers fly off (jaggedly) to one side, rather than expand directly towards us, like train tracks?

As with the wagon teams, you have to imagine diagonal actions as rotated inward to parallel one another during projection. What you see is not what you’d get in the theatre. But also, what you see is something you’ve never seen in a movie before.

Most of these effects are heightened by the inability of the three-eyed monster to record close-ups. Because of the short focal length, the camera unit sat very near the actors: for a shot from the waist up, the central lens was between one-and-a-half and three feet away. Putting the camera so close necessitated lights being attached to the camera unit. But normally close-ups were avoided, so the human figures never dominate their locales. These movies are, more than most, about space–however buckled and bizarre that space might be.

Because of the panels, panning shots were to be avoided, but certain kinds of camera movement forward were welcomed. The signature Cinerama shot is the shot plunging toward the vanishing point–a boat rushing through the water, an aerial view banking toward the horizon. Even though the blend lines made shapes and edges wrinkle, this gigantic, embracing image streaming toward viewers gave a compelling illusion that they were hurtling forward.

The distortions are less visible from a perfect vantage point in a Cinerama auditorium–presumably, as close as you can get. Distortions on the display edges would be minimized by peripheral vision, which isn’t good at registering detail. Presumably some of the curvilinear shapes, like Linus’ oar, and those kinks across the blend lines, would be less egregious if viewed straight on. Watching from the front row in Bradford, I recall seeing these distortions, but they didn’t seem as vivid.

Naturally, not everybody in the auditorium has a perfect vantage point. In the original screenings, people who had sat on the sides complained that movement on the nearest flanking panel seemed to flow upward. Smilebox, which respects the overall geometry of the display, still yields disparities. Linus’ oar still curves, though not as pronouncedly.

My images here, and yours on your home screen, are unavoidably mapping a curved display onto a flat surface, so there will still be anomalies. If you want to try cutting down on them, sit close to the Smilebox display. I prefer to sit back and enjoy their weirdness.

They’re features, not bugs

What about the films themselves? Arguably no great film was made in the format, but all the releases probably have some admirers. I want to end by talking about the two I find most appealing.

Cinerama’s travelogues were episodic, designed to show off features of the process in different filming situations. The two fiction features had to highlight the process and tell a coherent, engaging story. They too tend toward the episodic, but they handle that option in different ways. And stylistically, both work against the official “rules” of the new format.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, an entertaining family film, employs a frame story. The brothers are assigned to write the family history of the local Duke. Jacob, an expert linguist, does his job dutifully, but Wilhelm plays hooky to find and write up fairy tales he hears. His zeal to collect stories leads to the loss of their commissioned manuscript, and he falls ill, during which several fairy-tale characters come to visit him. Eventually Jacob is honored by the Royal Academy, but it’s Wilhelm who gets enduring glory by being swarmed over by hordes of children anxious to hear his latest tale. Within this overarching plot, three of the stories are enacted using various special effects, including puppet animation. Some of these shots appear to have been shot in a non-Cinerama format and “paneled” afterward.)

It’s tempting to ascribe the frame story’s direction to Hollywood veteran Henry Levin and the embedded fantasies to co-director George Pal. To the connoisseur of Cinerama, those fantasy passages offer some delights. If anybody told Pal about the rules for shooting in the format, he ignored them. The fairy tales give us whirling camera movements, bumpy subjective shots, and frequent assaults on the audience in the manner of 3D. During a wild coach ride, the coachman hurls himself to and from the camera. Later, a knight’s bumbling servant slays a dragon in lunging close-up.

You can even take certain passages as sly parodies of the brand. The Woodsman in the first tale has hitched a ride on the back of the coach, and he stoops to look underneath. Cut to his point-of-view: an upside-down version of a signature Cinerama shot.

Whoever directed the frame story scenes, however, was fairly bold too, moving his actors in zigzag patterns more flamboyant than the blocking of How the West Was Won. And instead of the small, high sets recommended for the format, Wonderful World shoots in throne rooms and palace salons that seem to stretch on forever. In smaller sets, like the brothers’ cottage, their friend’s bookshop, and especially the lair of a witch, the compositions take advantage of crannies and oddly angled planes that enhance the exaggerated distances.

As in German Expressionist cinema, the distortions seem to suit an atmosphere of fantasy. There’s even a massive violation of one of the basic rules of Cinerama: avoid tilting the camera. High and low angles were likely to exaggerate any distortions in the panels. Yet Levin, or Pal, or both occasionally throw in expressive angles, most strikingly a low angle showing Wilhelm’s family and friends ascending to his sickroom.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm solves the problem of the episode film by giving us a frame story. How the West Was Won solves it by a more threaded structure. A family saga creates branching stories that show three generations of kin participating in the winning of the frontier. The story acknowledges, briefly, the conquest of indigenous peoples–the “liberal Westerns” of the 1950s haven’t been ignored–but slavery doesn’t play a significant role. This is a story of white people.

The Prescott clan sets out on the Erie Canal, but on the rivers all but two of them lose their lives. The warm, slightly romantic Eve settles with the trapper Linus Rawlings on a farm in Ohio, while her sister Lilith ventures west. Eve’s son Zeb joins the Union forces in Civil War and later moves west with the railroad, eventually becoming a marshall. Lilith joins a wagon train, takes up with a gambler, inherits a worthless mine in California, and reunites with her lover on a riverboat. They become entrepreneurs investing in the railroad system. Near the end of the century, Lilith loses her fortune and joins Zeb, now retired, and his wife and children. But before they can settle down on Lilith’s inherited Arizona ranch, Zeb has to settle a score with a bandit who intends to rob a train. The film falls into sections specified in the credits–The Rivers, The Plains, and so on–but not in the film, though the parts usually end with fades.

Marker might note that How the West Was Won revives the piety and chauvinism on display in This Is Cinerama. The Prescott women found a kind of holy family, bound, as one song puts it, “for the Promised Land.” Some writers thumb through the phone book to get names for their characters, but screenwriter James R. Webb seems to have favored the Old Testament. Eve, living up to the positive side of her name, becomes the first woman of the new land. In forcing Linus to become a farmer, she helps turn the wilderness into a garden. Lilith, whose name associates her with sexuality and demonic possession, becomes a dance-hall girl and eventually a millionairess, but she has no children. At the end she returns to her nephew, Zebulon, named for her father; in the Old Testament he is the founder of a tribe. And Zeb has named his daughter Eve. The family abides in an endless cycle, its members replacing one another and its history intertwined with the full flowering of the United States.

The film ends with the sort of God’s-eye views that conclude This Is Cinerama, but emphasizing the modern West, with its dams, roads, cities, even whorls of traffic. Interestingly, in the place of the forward rush of the earlier film, these aerial shots pull us backward, the classic mark of the end of a story. But the finale of the epilogue carries us forward once more, under the Golden Gate Bridge and into a sunburst over the Pacific. Since women have played a central role, no surprise that the final lyrics of the choral accompaniment celebrate heroes as “every mother’s son.” This country has reached its natural limit; beyond is heaven, and the chorus tells us, here at last is the Promised Land.

Most scenes are handled briskly, but with little nuance beyond what the actors bring to the story. The spectacle remains appealing, the music infectious, and the imagery always impressive–especially when it’s a little whacked out, as in my examples above and many other scenes of the film. Like The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, this has shown that Cinerama can be edited rapidly. This Is Cinerama has only a little more than two hundred shots, but Wonderful World has a thousand, and How the West Was Won has over eleven hundred. The chapters of the latter yield some striking results: most average between eight and nine seconds, but John Ford’s Civil War segment averages nearly fifteen seconds, while the climactic Outlaws segment averages about five seconds.

That climactic sequence, directed like most of the film, by Henry Hathaway, makes splendid and varied use of the format. Despite a heavy reliance on back projection and several shots that seem not to have been made in the three-camera process, this monumental remake of The Great Train Robbery is a showcase for how Cinerama could create exciting action through staging and editing. To the advantages of Cinerama–forward drive, looming landscapes, and immersive sound–Hathaway and editor Harold Kress add percussive cuts of logs sliding this way and that, along with painful stunts, including one showing a man flung off a train and into a cactus.

By contrast, the Civil War sequence shows how a director can triumph over an inflexible format by relying on expressive stasis. Ford the pictorialist will carve striking compositions out of the constraints of Cinerama. He exploits the depth of the 27mm lenses, sometimes stationing all his figures in the central zone, as if he’s trying to preserve the 1.37 aspect ratio. At other moments he confines the action to a single flanking panel.

Sometimes Ford simply ignores the triptych format in order to split the frame in half or, say, two-fifths. He also gives his actors postures, props, and gestures that allow them to underplay. With Ford, even fresh-minted junior stars like Carroll Baker and George Peppard can give performances of gravity.

Ford’s creative choices stand out most strongly in two scenes set on the farm. In the first, Linus Rawlings has gone off to battle, and his son Zeb is itching to follow. Eve, now old, accepts with weary sadness that he will have his way. There’s a Griffithian two shot of Eve and Zeb on the porch, her arms dangling wearily and her right hand rising and falling as she asks Zeb about whether he’ll get a uniform. The hell with Cinerama, Pappy seems to say: Just fill up half the frame with the cabin to keep us fastened on the couple.

After a quick embrace, Eve dashes into the house. A porch shot that is virtually a Fordian doorway framing shows Zeb leaping with joy before he turns, sees something in the house, and halts in his tracks. Ford needn’t show us Eve’s grief. This is the most tactful shot in the whole film.

Soon enough Ford will recall this scene. Zeb has left for the war. Eve, kneeling at the family plot, prays to her father before slipping behind the rail. Her face is hidden, but her hands again express her resignation, and prefigure her death. She was never the same, her other son will say, after Zeb left.

These homestead passages are echoed by a scene at the end of the Civil War segment. Back from the war, Zeb learns of his mother’s death from his brother Jeremiah. The two sit on the porch sharing a dipper of water and recalling their father. Zeb rises to go, they shake hands, and we get another muted Fordian moment. Why move your actors when you can pose them?

Now the old director, a master of depth since the 1910s, bends this newfangled format to his own ends. Zeb leaves the frame, comes back in the far distance, and is finally blocked by the farmhouse, leaving Jeremiah quietly weeping.

That’s how you handle this busy, noisy new contraption, Ford seems to say. Dwell on moments of stillness and pathos. Use handshakes, embraces, a drooping black shawl. Keep the action in a well-defined zone. And treat this as a silent movie.

The most comprehensive account of Cinerama’s development is Thomas Erffmaier’s 1985 Northwestern Ph. D. thesis, The History of Cinerama: A Study of Technological Innovation and Industrial Management. Also invaluable are John Belton’s Widescreen Cinema (Harvard University Press, 1992) and Robert E. Carr and R. M. Hayes’ Wide Screen Movies (McFarland, 1988), usefully supplemented by Daniel J. Sherlock’s emendations here. A good older work is Michael Z. Wysotsky, Wide-Screen Cinema and Stereophonic Sound (Focal Press, 1971). Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale put This Is Cinerama into the context of postwar blockbusters in Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010), Chapter 7. On the Web, restorer and cinematographer Greg Kimble provides a thorough and well-illustrated account of Cinerama at In 70mm.

Chris Marker’s “Le Cinérama” appeared in Cahiers du cinéma no. 27 (October 1953): 34-37.

Cinerama grew out of Fred Waller’s experiments with gunnery-training displays during World War II, as Strohmaier documents in Cinerama Adventure. Waller discusses this work in “Cinerama Goes to War,” New Screen Techniques, ed. Martin Quigley, jr. (Quigley, 1953), 119-126. This collection includes other pieces of value on Cinerama, 3D, CinemaScope, and other new technologies. It would be interesting to know if Waller’s efforts influenced, or were influenced by, psychologist J. J. Gibson’s comparable wartime experiments with aerial training films. Gibson’s ideas about how we grasp space through “optical flow” and centered perspective have obvious parallels with the Cinerama process. Waller was said to have been influenced by another psychologist, Adelbert Ames, Jr., one of the founders of 1950s “New Look” psychology. Waller’s belief that our peripheral vision was more important than stereopsis in determining depth echoes Ames’ hypothesis that convergence and binocular disparity were overrated as depth cues.

Greg Kimble provides a thorough overview of the making of How the West Was Won in a 1983 article for American Cinematographer, available here. I’ve drawn as well on William Daniels’ article “Cinerama Goes Dramatic,” American Cinematographer 43, 1 (January 1962): 28-29, 50-54. Also useful was Darrin Scott, “Panavision’s Progress,” American Cinematographer 41, 5 (May 1960): 302, 304, 320-322, 324. My quotation about readjusted sets comes from Scott’s piece.

Three-panel Cinerama features can be seen occasionally today at the Pictureville Cinema in Bradford, the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles, and the Seattle Cinerama.

Simultaneously with This Is Cinerama, Flicker Alley has published a lavish Smilebox version of Windjammer, also prepared by David Strohmaier. That’s a whole other story.

P.S. 5 October: You never can tell. Jim Emerson forwards me this Indiewire report by Len Maltin on a new short made in three-panel Cinerama.

How the West Was Won.

TIFF: More than movies

Audiences gather for screenings at the Bell Lightbox, hub of the Toronto International Film Festival.

DB here:

Around midnight tonight, the crowds packing the Toronto International Film Festival will disperse, leaving the city full of memories of another extraordinary year. I’ve been back in Madison for this last week, but my few days at TIFF remain on my mind. This is partly because along with the films came a lot of ideas, opinions, and information. At any festival, fraternizing with audiences, critics, and programmers is one fine way to get that stimulation. It happened after some of the Wavelengths section’s short-film programs. Here are Raymond Phatanavirangoon and Bob Koehler outside the Art Gallery of Toronto, where their Devo retro-stylings raised our conversation to a new level.

More structured sessions delivered too. Out of my 4-plus days at the Toronto International Film Festival, I set aside about one and a half for industry panels and filmmaker Q & A’s. Let me tell you a little of what I learned.

From Assayas to Asia

TIFF: Where programmers meet stardom.

The talkfests I attended shed light on both film artistry and film business-making. Central to the first area was the master class with Olivier Assayas, hosted by Brad Deane.

Assayas, a charming fellow, talked fluently about how Something in the Air (discussed here) bears traces of his youth. During the 1970s, high-school kids were “footsoldiers of the cultural war of the time.” He recalled his affinities with the artistic side of the counterculture, as opposed to the extremes of the political activists, some of whom, being aligned with Maoism, refused to recognize the Cultural Revolution as “disaster on a demented level.” Yet this shouldn’t be taken as apolitical aestheticism; Assayas has been a vigorous advocate for the work of Situationist Guy Debord.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas doesn’t undertake elaborate rehearsals, instead coming to the set each morning and describing the shots they’ll make. He wants to take account of the evolution of the film as it’s been developing. He doesn’t fully block the shots. He sketches each one in longish takes that, as the actors expand on the action, “add layers” to what he’d initially planned. Alternatively, he cuts up the long takes and combines pieces of them. For Something in the Air, he relied on stable and wide framings, partly in reaction to trends toward handheld shots and close-ups, partly because he used the crane to create a “floating,” more lyrical circulation through the space.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Eli Roth (left), another kid who grew up with Kung-Fu Theatre on TV, was bowled over years later by Korean and Japanese thrillers like Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Now Roth is producer and co-writer of The Man with the Iron Fist, directed by RZA–who is, according to Roth, letter-perfect on his kung-fu film knowledge. “We wanted to do a movie like we saw as kids on Saturday afternoon.” But production values in the genre have swollen since the old days. The project is using the Hengtian studio’s vast replica of the Forbidden City. RZA, Roth says, expected The Last Emperor to be a kung-fu movie, so this is his attempt to make things right.

Tom Quinn, Co-President of the Weinstein Company’s RADiUS division, had similar affinities. As he pointed out, East Asian countries have strong local markets and so can build a base in genre cinema. With quantity comes quality. While working at Goldwyn and Magnolia, Quinn handled US distribution for The Host, Pulse, Tears of the Black Tiger, and most recently 13 Assassins, along with many other titles. Ong-Bak, on view at TIFF in 2004, was a particular triumph for him, yielding over a million dollars in its first weekend of release and eventually garnering $4.5 million in the US. Even the heavy piracy of Ong-Bak Quinn takes as a positive sign, “a validation of the film’s value.”

Bill Kong, a legendary Hong Kong producer and a force behind Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, along with Stephen Fung, director of Tai Chi 0 (above), filled out the panel. Overall, the discussion ranged widely, but one question kept cropping up. Why is it that Western films are widely popular in Asia, but Asian cinema is almost completely a niche market in the West? I didn’t hear a clear answer (though I’d start an answer with Western racial prejudice).

Kong noted that Asian filmmakers don’t have high expectations about penetrating the US market, but other panelists were more hopeful about crossover projects. Quinn pointed out that the festival circuit built an audience, and Roth thinks that Tarantino has been a major player in making Asian film more popular, especially with the Kill Bill duet. The fact that Russell Crowe plays a major part in The Man with the Iron Fist suggests that things may be changing.

Bigger than Bollywood

Mira Nair.

The East/West dynamic was also the focus of two other panels. “India: Lessons from Bollywood and the Independents” brought together a nearly all-female group of experts to discuss local financing and wider distribution. All were agreed that it was necessary to convince the world that Indian cinema was bigger than Bollywood. As director Dibakar Banarjee put it: “We need to open the third eye.”

The local industry has a certain comfortable inertia. A film might cost only $150,000, but it can collect 90% of its production costs upon its opening run, said Shailja Gupta, who has been both a director and production executive. Foreign distribution is a major risk at this budget level. So how does a project, particularly an independent film, get international traction?

Coproductions are an obvious path, and while they are still rare, the trend is emerging. The Indian government’s National Film Development Corporation Ltd. has helped with coproductions since 2006, says Nina Lath Gupta, NDFC Managing Director. Such enterprises are rare and mostly involve France or Germany. By establishing the Film Bazaar in 2007, the NDFC acknowledged the importance of marketing as well as financing, and this is getting local filmmakers acquainted with the need to think more globally.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Mira Nair, distinguished director of Salaam Bombay and Monsoon Wedding, has long enjoyed worldwide exposure, of course. She shared her thoughts on how filmmakers could follow their visions and still, as she put it, “put bums on seats.” That’s accomplished by not worrying about distribution but devoting energies to creative choices–such as she undertook in The Reluctant Fundamentalist, her first foray into the thriller genre.

During the India panel, moderator Meenakshi Shedde asked if China might become a coproduction partner for local films. This is currently not happening, but the question reflects the significance of the People’s Republic on the global film scene. Earlier in the day, a panel on “Financing Between Asia and the West,” moderated by Patrick Frater, concentrated mostly on China as the leading edge of the region. Once more, the question of coproductions was central.

“Coproduction is a reality now for global filmmaking,” declared Peter Shiao, CEO of Orb Media Group. But the power of China in the new media landscape has created a false optimism among Western entrepreneurs. Shiao warned newcomers that coproductions can’t be fulfilled in good faith with perfunctory gestures, such as including a Chinese actor in a secondary role. (The Expendables 2 was mentioned in this connection.) Aspiring filmmakers need to grasp and follow the China Coproduction Film Office regulations straightforwardly.

Solid coproductions are rare, agreed Bruno Wu, founder and chair of many top Chinese media groups. He pointed out that what works in China won’t necessarily work in the rest of the world, but what works in the rest of the world is likely to work in China. So the Chinese investor needs to look at projects that will play internationally. He gave as examples his firms’ deals with Justin Lin and John Woo, who have reliably won global audiences. Along similar lines, Stuart Ford, founder and CEO of IM Global, suggested that a good alternative to coproduction involves soliciting equity investment from China for Western films. For example, Chinese investors in Paranoia, a $40 million production, acquired mainland distribution rights as part of the deal.

The soundness of investing in Western films seems borne out by local box-office figures. Seventy percent of China’s market receipts come from English-language imports; the several hundred domestic films produced earn only twenty percent. And theatrical receipts provide, according to Peter Shiao, ninety percent of a film’s earnings. Windows in the Western sense don’t exist, and there’s no legitimate home video market. Gradually local filmmakers are experimenting with Western ancillary tactics; Painted Skin: The Resurrection recently tried out apps and games.

China-based Video on Demand is more promising. In a few years, Wu expects there to be several million addressable HD cable homes, and providing entertainment on demand might provide a way around the national quota system for film import. There is no quota restraining VOD distribution, and as it takes hold, it might reduce piracy.

A killer app? (as in killing off business?)

Jonathan Sehring and Winnie Lau at the VOD panel at TIFF, 9 September 2012.

Speaking of VOD, in early September I signed up. I did it partly because there was one title I needed to see immediately: Keanu Reeves’ Side by Side, the documentary about the digital vs. film controversy. More abstractly, I had been learning a little about VOD when I recast and expanded my blogs on digital exhibition for Pandora’s Digital Box, and I was curious about how VOD worked in practice.

After a period of turmoil, the US film industry has integrated VOD into its system of non-theatrical ancillaries. Before, we had DVD and Blu-ray, both rental and retail, along with movie channels like HBO and Sundance available on subscription cable. Eventually movies would show up on basic-cable channels. There was also “pay per view” via cable, a one-off transaction now known as Pay TV VOD.

Now, the internet has expanded the options.

*Electronic Sell-Through (EST) allows the consumer to download a film and own it. This service is available through iTunes, Amazon, and other outlets.

*iVOD (internet VOD) is a one-off rental, to be run immediately or within a specified time period. To check the 1.77 aspect ratio on Dial M for Murder, I rented it for 24 hours on iTunes.

*Subscription VOD (SVOD), which you get with Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and other providers. This option provides a library of titles available at any time for a monthly fee. SVOD is comparable to cable-television subscriptions, and it’s becoming very popular, as all-you-can-eat options tend to be.

In addition, another option hovers over the business:

*Premium VOD (PVOD) consists of a one-off rental available sooner than the traditional home-video window. The transmission would be via cable or satellite, not the Net, and the price point has typically been $30 for one viewing. The studios tried out PVOD with DirecTV in 2011, with apparently unencouraging results. Worse, last year’s Tower Heist fracas, during which Universal planned to put the film on PVOD 30 days after theatrical release, triggered threats of boycotts from exhibitors. PVOD, however, is likely to reappear at some point because it can offset losses from the declining DVD market.

No surprise, then, that one industry panel was called “VOD Killed the DVD Star.” The session assembled major players in that domain to discuss the present situation and the prospects for the future.

Much of the panel’s time was devoted to explaining why filmmakers needed to be flexible about accepting VOD as a legitimate complement to or substitute for theatrical release. VOD, they insisted, shouldn’t be seen as a dumping ground for weak or narrow-interest films. The reason: The consumer is king, and consumers want everything on demand.

Winnie Lau, Executive Vice-President for Sales and Acquisitions at Fortissimo, said that companies now recognized that consumers should be able to see a film on whatever platform they want. Given the high costs of a theatrical release, that option isn’t justifiable for many films. Philip Knatchbull, CEO of Curzon Artificial Eye, put the case more strongly, declaring that with the consumer in control, notions like windows and “on demand” are losing their usefulness. His view suits a company that, like IFC, has integrated video and theatrical distribution with theatre ownership and HD delivery. There are, he suggested, only home cinema and public cinema, and everyone in the film value chain should be aiming to reach millions of screens.

Tom Quinn of RADiUS was working for Magnolia when in 2005 Mark Cuban experimented with a multiple-platform release of Bubble. “His vision,” Quinn recalled, “was to make films available whenever people liked.” The Bubble experiment was problematic because it came out on film and on DVD simultaneously, but Quinn said that “the hotel VOD numbers were through the roof.” This summer, after twelve months of preparation, RADiUS has issued its first VOD titles, and Bachelorette, released earlier in September, won notice for earning about half a million dollars in its first weekend.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

Burns was satisfied with the results and built a production model around VOD. The cast and crew work for free and collectively own the film. Budgets can be low; he claimed last year that Newlyweds cost only $100,000. Payments are deferred, and if a film breaks through, everyone makes money. His last three films, he reported, did. He compared the business model to that of an indie band. VOD gets his work to the people who watch HBO, Showtime, AMC. “That’s our audience.”

Burns is an unusual instance, since as one panelist pointed out, he has established his own brand. Still, other VOD releases can break out. The most widely publicized example is Margin Call, with about $4.5 million on VOD. Jonathan Sehring, President of IFC and Sundance Selects, was a pioneer of alternative platforms, and he remarked that 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days did better on VOD than in theatrical release (where it grossed $1.2 million). In a recent interview, Sehring indicates that the recent IFC release About Cherry as doing as well as Bachelorette on VOD and other revenue streams.

It seems, then, that these and other industry decision-makers see VOD as offering two avenues, depending on the film. VOD can provide a new window, to be added before or after or during theatrical release. Alternatively, VOD can replace theatrical, as it has done for Burns (who will still occasionally give a film like the upcoming Fitzgerald Family Christmas brief theatrical play). With this option, many films, both domestic and imported, will never see a theatrical release but they might make money on the less costly VOD platform.

The problem for the second strategy is finding a way to make the film stand out from the thousands of titles available in cable and VOD libraries. A theatrical release provides the “shop window,” as Knatchbull called it, but without that, the film needs other salient features–big stars or cult buzz–to attract the home viewer.

Despite the panel’s title, the guests didn’t predict that VOD would displace discs. In fact a couple of panelists agreed that DVD and Blu-ray would be around quite a while. Quinn (left) confessed that as someone who grew up with VHS he would always be collecting his favorite films on physical media.

There’s something else to consider: some dramatic disparities between VOD and DVD consumption. The differences are spelled out in a recent IHS Screen Digest report.

On one hand, the VOD audience has grown rapidly. The report counted transactions–buying a movie in any form–and came up with striking figures for the world’s top five regions.

2007: DVD retail and rental: 2.7 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 14.8 million transactions.

2011: DVD retail and rental: 2.58 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 1.4 billion transactions (nearly all SVOD).

The Screen Digest team estimates that 2012 will see an even bigger burst in online VOD, totaling 3.4 billion transactions, with nearly all that via subscription. (I’m in there somewhere.) By contrast, physical media sales and rentals are predicted to fall further, to 2.4 billion transactions.

The disparity lies in “monetization.” We have some access to weekend box office grosses, but almost none to income from DVD and VOD, so comparison is difficult. Still, everyone knows that DVD purchase and rental, along with pay TV licensing, yield the bulk of film revenues. In another research report, Screen Digest estimates that in the US the 2012 surge in VOD will yield only $1.72 billion. DVD will yield $11.1 billion, nearly ten times the VOD transactions. Even with the declining retail and rental prices of discs, VOD yields much less per transaction than DVD does, especially with subscription services leveling out the cost to consumers.

So did VOD kill, or at least wound, the DVD star? When measured in transactions, yes. In revenues, no. Moguls pay off their Ferraris in dollars, not transactions, so it seems that VOD would have to expand colossally, or raise prices, or both, to come close to achieving the returns of DVD.

It’s conceivable that VOD will cannibalize other windows, if you’ll excuse the mixed metaphor. DVD transactions were going downhill before the rise of VOD, but perhaps VOD will accelerate that plunge. iTunes already charges up to $20 for EST downloads of a new release. As consumers become used to storing their movie and TV collections digitally, the convenience of EST could hurt DVD sales.

Moreover, VOD has always threatened the theatrical market. That’s why exhibitors cried foul when Premium VOD was tried. But box-office grosses overall remain robust because ticket prices are constantly rising and 3D and Imax rely on upcharges. These revenues offer studios a good reason to maintain strict windows, at least for their most successful releases. Still, studios are very likely to continue to press for PVOD. And indie distributors have embraced VOD release exuberantly. Foreign and indie titles released on VOD before or during the theatrical run may steal business from art houses.

In sum, VOD might shake up the other platforms quite a bit. If your analogy is the music business, theatrical and DVD formats stand in for albums, while VOD is the online force that lowers consumers’ sense of a fair price point. There’s some discussion of raising prices for some iVOD and Pay TV VOD offerings to parity with theatrical ticket prices. I wonder if consumers will sit still for that. As a novice VOD’er who likes going out to see movies big, I probably wouldn’t. Unless Hulu’s Criterion library discovered a lost Mizoguchi.

Assayas’ autobiography A Post-May Adolescence has just been published in English translation. It includes two essays on Debord. At the same time, an anthology of critical essays on Assayas, edited by Kent Jones, has appeared in the sterling Austrian Film Museum series.

Patrick Frater reports on the TIFF Asian Film Summit at Film Business Asia.

My statistics on the progress of VOD come from “Movie Consumption Stabilizes,” IHS Screen Digest (April 2012): 95-98, and “Online Movie Consumption in the US,” IHS Screen Digest (May 2012): 116. See also Andrew Wallenstein’s Variety story, where we learn that Netflix’s subscription model is beating the pants off the competition. Thanks to David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest for further information.

As before, thanks to my Toronto hosts Cameron Bailey, Brad Deane, Christoph Straub, Andrew McIntosh, Andrea Picard, and all their colleagues.

TIFF leaves an indelible mark: The ankle of Crystal Decker, Marketing Manager of Well Go USA Entertainment, US distributor of Tai Chi 0.

P.S. 17 September: Thanks to Anuj Mehta for correction of a misspelled name.

“Indie blockbuster franchise” is not an oxymoron

Kristin here:

The Cannes Film Festival continues even as I type. Much of the wheeling and dealing at the market that accompanies the festival is being driven by two franchises that few people outside the film industry think of as independent films: the Twilight and Hunger Games series. Indie blockbuster franchises aren’t common. In fact, there had previously been only one, but its parallels to these contemporary franchises reflect a recent major shift in international independent distribution.

True or false, The Lord of the Rings is an indie film

In May of 2001, I, as a Tolkien fan since high school, was resolutely ignoring the production of a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, going on in New Zealand. The first part of the trilogy was to be released in December, and there was widespread skepticism in the press, both popular and trade, and among fans and industry insiders concerning the possibility of the film’s being a success. Another fantasy adaptation, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, looked likely to be the hit of the Christmas season, eclipsing New Line Cinema’s expensive gamble.

Then came New Line’s Cannes event of 2001. Over a three-day weekend, the studio presented an elaborate program to reveal the film. On Friday night there was a screening of a 26-minute preview of footage from all three films, with an extended portion of the Mines of Moria scene in nearly completed form as its centerpiece. Even cast and crew members present, as well as top New Line officials, had not yet seen any of the film’s finished footage until that screening, and they were overwhelmed. Jaded reporters cheered and asked to have the preview re-run. Extra screenings had to be arranged. A series of press interviews were held, and a lavish party complete with sets and props from the film was held in a chateau. Suddenly the popular press was full of infotainment pieces predicting that the trilogy would be a blockbuster hit. Fan webmasters invited to the event posted enthusiastic, even ecstatic reports.

Variety’s report of the preview screening is the first article about the film that I remember reading. It began:

It’s hard to imagine a more relieved group of distribs gathered into one place than the collection who’d just finished watching a 26-minute film from New Zealand that cost $270 million.

The enthusiastic response from distribs, exhibs and worldwide press to the screening of footage from New Line’s “Lord of the Rings” at Cannes Olympia theater means that foreign companies that bet the farm on the three-year franchise now have cause for confidence they’ll recoup their investment–with coin to spare. […]

In marketing meetings after the screenings, NL execs told distribs that the target is for all of them to outdo the previous top grosser in their territory. In some countries, that’s going to mean spending as much again on P&A [prints and advertising] as they did to buy the films in the first place, but at least now that seems more like an opportunity than a terrifying risk.

Rolf Mittweg, at the time head of New Line’s international marketing and distribution, noted: “My Japanese distributor said he had a knot in his stomach for the whole year, and now it has dissolved.” [Adam Dawtrey, “Will ‘Lord’ ring New Line’s bell?” 21-27 May 2001, pp. 1, 66.]

This considerably intrigued me, and it was probably the first step in the long path that ended with me writing The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood.

What Variety was referring to, it turned out, was the twenty-six independent distributors from various territories around the world who were forced by New Line, if they wanted LOTR, to pay large sums up front for the film, sight unseen. That in itself wasn’t odd, since independent films were commonly financed in part by pre-sales to international distributors, often on the basis of a script or a star attached to the project. The difference here was that the chosen twenty-six had to pay a lot (as much as $8 million for the larger European territories) for all three feature-length parts of the film. If the first one flopped, the second and third would be almost worthless. Small wonder they were nervous going into the Cannes event.

As everyone knows, LOTR went on to enormous success, with the third installment becoming only the second film to cross a billion dollars in worldwide grosses (the first having been Titanic in 1997).

Many people would be surprised to learn, however, that LOTR was not the product of one of the major Hollywood studios. It came from an independent company, New Line. True, New Line was at that point owned by Time Warner, but it operated as an independent film producer-distributor. That is, it didn’t receive financing for its films from its parent company but through pre-sales–pretty much the definition of an indie establishment. It was also a studio that thrived in part because it stressed franchises, notably the Nightmare on Elm Street, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Rush Hour, and Austin Powers films. Successful though these were, LOTR was a step up for New Line, both in terms of prestige and budget. It was perhaps the first indie blockbuster franchise.

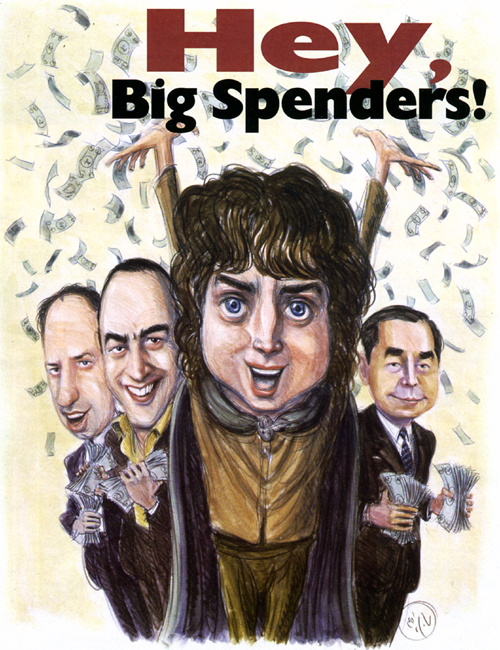

It was such a blockbuster, in fact, that LOTR helped pull the international independent and foreign-language film market out of a major slump that had begun in mid-2000 in the wake of over-production in the late 1990s. The crises in the Brazilian and Argentinian economies in 1999, the bursting of the dotcom bubble in mid-2000, and the 9/11 attacks in 2001 worsened the decline. I won’t go into detail here. (You can read a more thorough account in Chapter 9 of my book.) Suffice to say that the crisis happened to be at its worst when The Fellowship of the Ring came out in mid-December, 2001. During the first half of 2002, there were slight signs of a recovery, but the accumulating income from the film and also from the summer release of the DVD strengthened it considerably. By the time of the American Film Market in early 2003, The Hollywood Reporter ran the caricature above and declared, “With his quest to save Middle-earth from the Dark Lord, the intrepid hobbit might have helped rescue the annual event from the clutches of a global recession.”

As a result, the lucky 26 distributors were able to buy more at the AFM and other important indie sales venues. Reporting from Cannes, Variety declared, “The global bonanzas of ‘Lord of the Rings’ is playing its part in driving big-budget pre-sales.” Screen International said New Line was “buoying the indie market with The Lord of the Rings.” Sales and pre-sales of indie films were up. Small companies could afford to buy more desirable films than in the past. For example, SF Film in Denmark (a branch of Sweden’s AB Svenska Filmindustri) was able to acquire Million-Dollar Baby, a film that previously would have been beyond its means. A few of these companies also used their LOTR money to produce local films or to open art-house cinemas.

The problem was, the film had only three parts. New Line’s next attempt at a blockbuster franchise would knock the biggest supplier of indie films to foreign distributors entirely out of the market.

The New Line void

On December 7, 2007, The Golden Compass was released, the first in an intended trilogy based on the “His Dark Materials,” a trio of prize-winning books by another English author, Philip Pullman. With a reported production budget of $180 million, the film grossed about $70 domestically, though it managed $372 million worldwide.

On March 28, 2008, four years and four weeks after The Return of the King won eleven Oscars, Time Warner announced that New Line would be absorbed into Warner Bros. Entertainment as a genre unit. Its domestic distribution and international sales activities would be dissolved. The top executives of the international sales wing, Rolf Mittweg and Camela Galano, who had helped put together the enormously complex group of foreign distributors who largely financed LOTR, would soon be out of jobs. The fact that the change came less than two months before the Cannes Film Festival led trade papers to assess New Line’s importance as a supplier to the international independent market and to speculate on what companies might step into the void left by its departure.

(For my own analysis of what the loss of New Line product would mean for the indie market, see “Filling the New Line gap,” from November 6, 2008.)

Shortly after the March announcement, Screen International editor Mike Goodridge looked back at the impact of Peter Jackson’s trilogy on the distributors who released it abroad:

The success of the three films for the international partners cannot be overestimated. Nor can the fact they, more than anybody involved, took a huge risk on the trilogy. The risk paid off. The Greens at Entertainment [UK distributor], the Hadidas at Metropolitan [French distributor] and others genuinely shared in the profits of one of the box-office phenomenons of of the last 20 years. It was the international buyers’ dream. Instead of losing money on studio cast-offs, they had a hefty piece of a trilogy which grossed nearly $2bn outside North America. [“The End of the Line,” 7 March 2008, p. 6.]

Goodridge points out that although The Golden Compass, New Line’s intended first entry in the “His Dark Materials” trilogy, had not done well in North America, its box-office abroad was likely to hit in the region of $300 and speculated that if it did, “Warner Bros. will be hard-pressed to deny production to a sequel.” [p. 8]

This optimistic view generously assumes that Warners would want to reward New Line’s old customers abroad by making the two remaining films in the trilogy despite a possible repeat of the first installment’s lackluster domestic gross. Instead, Jeff Bewkes had no interest in keeping up alliances with those loyal distributors, since by investing in the production of films up front, those distributors got to keep most of the box-office takings in their respective countries. As Bewkes said, “With the growing importance of international revenues, it makes sense for New Line to retain its international film rights and to exploit them through Warner Bros.’ global distribution infrastructure.” (For more on the international implications of the absorption of New Line, see this piece on my Frodo Franchise blog.)

Goodridge quotes San Fu Maltha, head of Dutch distributor A-Film (which had the LOTR trilogy for the Netherlands): “New Line was one of the supplier of major films. For [the distributors,] it was, if not a lifeline, an important source.” New Line films from 2007 that had done well abroad included Hairspray, Rush Hour 3, and The Golden Compass. Earlier hits had been entries in the franchises that had traditionally driven New Line’s success: the Austin Powers series, the Nightmare on Elm Street series, and so on. Goodridge concluded that Summit and Overture would be major sources of quality films for the foreign market.

In early May, 2008, with Cannes looming, Variety ran a story about the opportunities opened by New Line’s departure from the market. The subtitle suggests how big the change was perceived to be: “Opportunities Rock: Fresh contenders eager to join international indie scene’s new world order.” The story speculated on the various independent sales groups that will be at Cannes and which ones might be strong enough to replace New Line: QED, with W, District 9, and A Perfect Getaway; Essential Entertainment, with My One and Only; The Film Department’s Law Abiding Citizen and The Rebound.

Swart also noted changes in two major suppliers to the indie market. Summit was growing, having opened its own domestic distribution wing. It “is chasing studio ambitions, which seems to have taken the main emphasis off foreign sales.” Mandate (notable for Juno and the Harold and Kumar sequels) had been acquired by Lionsgate in September, 2007.

Cannes also provided the occasion for a second in-depth analysis of the New Line void by Screen International. Author John Hazelton suggested that New Line’s regular supply of six to eight films to its regular distributors overseas benefited international indies as a whole:

Many sales executives, in fact, go further and suggest that by boosting the fortunes of the distributor partners with which it had ongoing output or package deals—companies including the UK’s Entertainment, France’s Metropolitan, Australia’s Village Roadshow and Spain’s Tri Pictures—New Line effectively elevated the independent international industry as a whole. Other sellers benefited, for example, when the New Line distributors reinvested profits from The Lord Of The Rings and Rush Hour movies—or from last Christmas’ The Golden Compass—in the acquisition of non-New Line films.

Hazelton quotes Steve Bickel, president of The Film Department’s international wing: “New Line provided a great service to all of us because they helped make strong companies that we’re now able to sell to.” The author also presciently singles out Summit and the newly merged Lionsgate and Mandate as “leading the field of remaining big picture suppliers,” noting that both companies had recently expanded into domestic distribution and were signing output deals in some foreign countries.

The article refers to The Weinstein Company and The Film Department as promising new players. Relativity, having produced Atonement, Evan Almighty, Baby Mama and Pineapple Express, was moving for the first time into international sales at Cannes. Other companies are mentioned as possibilities. Hazelton concludes:

On its own, Relativity probably will not fill the gap created by the disappearance of New Line from the business that A Nightmare On Elm Street, The Mask and The Lord of the Rings helped build. And neither will any of the other sales companies or producers now eyeing the fresh demand for upscale product from international buyers. But between them, the new entrants, growing boutiques and established players will be trying fill the New Line-shaped void appearing on the international sales landscape.

Reporting that autumn on the American Film Market, Screen International noted that The Weinstein Company had sold five films to Entertainment, formerly supplied by New Line. These included The Reader, Zack And Miri Make a Porno, and Piranha 3-D. Relativity had closed multi-year output deals with several overseas distributors, including former New Line customers Village Roadshow (Australia, New Zealand, and Greece) and Alliance Films (Canada). Neither company, however, would be the one to release the second indie blockbuster franchise.

From New Line to New Moon

In 2008, the world was in a global recession brought on by the financial crisis of 2007. But even as the trade press was speculating on which company or companies would replace New Line, help was on the way. Summit’s release of Twilight came in November of the same year, and although it did not make as much as the three following films in the franchise so far released, it grossed nearly $393 million internationally, $200 million of that outside North America. A healthy take for a film reportedly budgeted at $37 million.

The modest title did not indicate that Twilight was the launch of a franchise, though obviously Summit was hoping that it would be. The subsequent entries were more forthright and more lucrative: The Twilight Saga: New Moon (November, 2009, nearly $710 million worldwide), The Twilight Saga: Eclipse (June, 2010, about $700 million), and The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 1 (November, 2011, just over $705 million), with the final installment due out in November of this year.

On the occasion of the second film’s release, Mike Goodridge of Screen International noted that the franchise’s success echoed that of a certain earlier series:

Distributed in major territories by companies which had signed to output deals with Summit Entertainment for its in-house productions, the first film, Twilight, was a sensation buyers were hardly anticipating when they made the initial deals. [….] Seeing E1 Films take nearly $20m in the UK, SND in France scoring $17m, Eagle in Italy $14.3m and Aurum in Spain $13.7m last weekend brought back the heady days of The Lord of the Rings openings.

Goodridge also pointed out: