Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

“Indie blockbuster franchise” is not an oxymoron

Kristin here:

The Cannes Film Festival continues even as I type. Much of the wheeling and dealing at the market that accompanies the festival is being driven by two franchises that few people outside the film industry think of as independent films: the Twilight and Hunger Games series. Indie blockbuster franchises aren’t common. In fact, there had previously been only one, but its parallels to these contemporary franchises reflect a recent major shift in international independent distribution.

True or false, The Lord of the Rings is an indie film

In May of 2001, I, as a Tolkien fan since high school, was resolutely ignoring the production of a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, going on in New Zealand. The first part of the trilogy was to be released in December, and there was widespread skepticism in the press, both popular and trade, and among fans and industry insiders concerning the possibility of the film’s being a success. Another fantasy adaptation, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, looked likely to be the hit of the Christmas season, eclipsing New Line Cinema’s expensive gamble.

Then came New Line’s Cannes event of 2001. Over a three-day weekend, the studio presented an elaborate program to reveal the film. On Friday night there was a screening of a 26-minute preview of footage from all three films, with an extended portion of the Mines of Moria scene in nearly completed form as its centerpiece. Even cast and crew members present, as well as top New Line officials, had not yet seen any of the film’s finished footage until that screening, and they were overwhelmed. Jaded reporters cheered and asked to have the preview re-run. Extra screenings had to be arranged. A series of press interviews were held, and a lavish party complete with sets and props from the film was held in a chateau. Suddenly the popular press was full of infotainment pieces predicting that the trilogy would be a blockbuster hit. Fan webmasters invited to the event posted enthusiastic, even ecstatic reports.

Variety’s report of the preview screening is the first article about the film that I remember reading. It began:

It’s hard to imagine a more relieved group of distribs gathered into one place than the collection who’d just finished watching a 26-minute film from New Zealand that cost $270 million.

The enthusiastic response from distribs, exhibs and worldwide press to the screening of footage from New Line’s “Lord of the Rings” at Cannes Olympia theater means that foreign companies that bet the farm on the three-year franchise now have cause for confidence they’ll recoup their investment–with coin to spare. […]

In marketing meetings after the screenings, NL execs told distribs that the target is for all of them to outdo the previous top grosser in their territory. In some countries, that’s going to mean spending as much again on P&A [prints and advertising] as they did to buy the films in the first place, but at least now that seems more like an opportunity than a terrifying risk.

Rolf Mittweg, at the time head of New Line’s international marketing and distribution, noted: “My Japanese distributor said he had a knot in his stomach for the whole year, and now it has dissolved.” [Adam Dawtrey, “Will ‘Lord’ ring New Line’s bell?” 21-27 May 2001, pp. 1, 66.]

This considerably intrigued me, and it was probably the first step in the long path that ended with me writing The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood.

What Variety was referring to, it turned out, was the twenty-six independent distributors from various territories around the world who were forced by New Line, if they wanted LOTR, to pay large sums up front for the film, sight unseen. That in itself wasn’t odd, since independent films were commonly financed in part by pre-sales to international distributors, often on the basis of a script or a star attached to the project. The difference here was that the chosen twenty-six had to pay a lot (as much as $8 million for the larger European territories) for all three feature-length parts of the film. If the first one flopped, the second and third would be almost worthless. Small wonder they were nervous going into the Cannes event.

As everyone knows, LOTR went on to enormous success, with the third installment becoming only the second film to cross a billion dollars in worldwide grosses (the first having been Titanic in 1997).

Many people would be surprised to learn, however, that LOTR was not the product of one of the major Hollywood studios. It came from an independent company, New Line. True, New Line was at that point owned by Time Warner, but it operated as an independent film producer-distributor. That is, it didn’t receive financing for its films from its parent company but through pre-sales–pretty much the definition of an indie establishment. It was also a studio that thrived in part because it stressed franchises, notably the Nightmare on Elm Street, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Rush Hour, and Austin Powers films. Successful though these were, LOTR was a step up for New Line, both in terms of prestige and budget. It was perhaps the first indie blockbuster franchise.

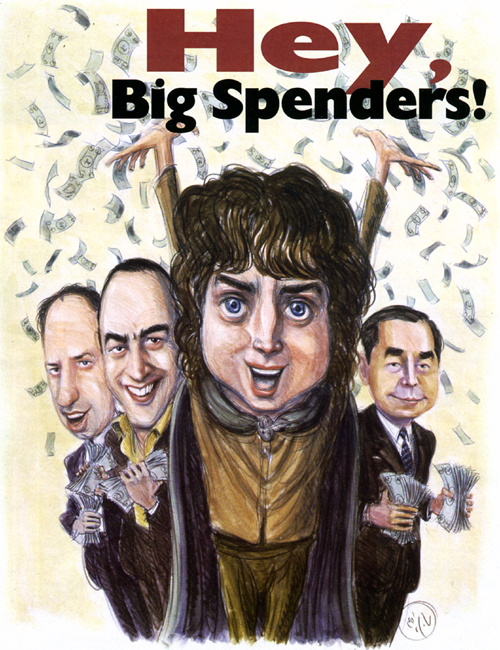

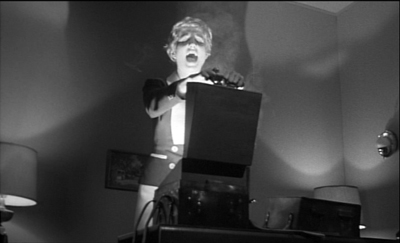

It was such a blockbuster, in fact, that LOTR helped pull the international independent and foreign-language film market out of a major slump that had begun in mid-2000 in the wake of over-production in the late 1990s. The crises in the Brazilian and Argentinian economies in 1999, the bursting of the dotcom bubble in mid-2000, and the 9/11 attacks in 2001 worsened the decline. I won’t go into detail here. (You can read a more thorough account in Chapter 9 of my book.) Suffice to say that the crisis happened to be at its worst when The Fellowship of the Ring came out in mid-December, 2001. During the first half of 2002, there were slight signs of a recovery, but the accumulating income from the film and also from the summer release of the DVD strengthened it considerably. By the time of the American Film Market in early 2003, The Hollywood Reporter ran the caricature above and declared, “With his quest to save Middle-earth from the Dark Lord, the intrepid hobbit might have helped rescue the annual event from the clutches of a global recession.”

As a result, the lucky 26 distributors were able to buy more at the AFM and other important indie sales venues. Reporting from Cannes, Variety declared, “The global bonanzas of ‘Lord of the Rings’ is playing its part in driving big-budget pre-sales.” Screen International said New Line was “buoying the indie market with The Lord of the Rings.” Sales and pre-sales of indie films were up. Small companies could afford to buy more desirable films than in the past. For example, SF Film in Denmark (a branch of Sweden’s AB Svenska Filmindustri) was able to acquire Million-Dollar Baby, a film that previously would have been beyond its means. A few of these companies also used their LOTR money to produce local films or to open art-house cinemas.

The problem was, the film had only three parts. New Line’s next attempt at a blockbuster franchise would knock the biggest supplier of indie films to foreign distributors entirely out of the market.

The New Line void

On December 7, 2007, The Golden Compass was released, the first in an intended trilogy based on the “His Dark Materials,” a trio of prize-winning books by another English author, Philip Pullman. With a reported production budget of $180 million, the film grossed about $70 domestically, though it managed $372 million worldwide.

On March 28, 2008, four years and four weeks after The Return of the King won eleven Oscars, Time Warner announced that New Line would be absorbed into Warner Bros. Entertainment as a genre unit. Its domestic distribution and international sales activities would be dissolved. The top executives of the international sales wing, Rolf Mittweg and Camela Galano, who had helped put together the enormously complex group of foreign distributors who largely financed LOTR, would soon be out of jobs. The fact that the change came less than two months before the Cannes Film Festival led trade papers to assess New Line’s importance as a supplier to the international independent market and to speculate on what companies might step into the void left by its departure.

(For my own analysis of what the loss of New Line product would mean for the indie market, see “Filling the New Line gap,” from November 6, 2008.)

Shortly after the March announcement, Screen International editor Mike Goodridge looked back at the impact of Peter Jackson’s trilogy on the distributors who released it abroad:

The success of the three films for the international partners cannot be overestimated. Nor can the fact they, more than anybody involved, took a huge risk on the trilogy. The risk paid off. The Greens at Entertainment [UK distributor], the Hadidas at Metropolitan [French distributor] and others genuinely shared in the profits of one of the box-office phenomenons of of the last 20 years. It was the international buyers’ dream. Instead of losing money on studio cast-offs, they had a hefty piece of a trilogy which grossed nearly $2bn outside North America. [“The End of the Line,” 7 March 2008, p. 6.]

Goodridge points out that although The Golden Compass, New Line’s intended first entry in the “His Dark Materials” trilogy, had not done well in North America, its box-office abroad was likely to hit in the region of $300 and speculated that if it did, “Warner Bros. will be hard-pressed to deny production to a sequel.” [p. 8]

This optimistic view generously assumes that Warners would want to reward New Line’s old customers abroad by making the two remaining films in the trilogy despite a possible repeat of the first installment’s lackluster domestic gross. Instead, Jeff Bewkes had no interest in keeping up alliances with those loyal distributors, since by investing in the production of films up front, those distributors got to keep most of the box-office takings in their respective countries. As Bewkes said, “With the growing importance of international revenues, it makes sense for New Line to retain its international film rights and to exploit them through Warner Bros.’ global distribution infrastructure.” (For more on the international implications of the absorption of New Line, see this piece on my Frodo Franchise blog.)

Goodridge quotes San Fu Maltha, head of Dutch distributor A-Film (which had the LOTR trilogy for the Netherlands): “New Line was one of the supplier of major films. For [the distributors,] it was, if not a lifeline, an important source.” New Line films from 2007 that had done well abroad included Hairspray, Rush Hour 3, and The Golden Compass. Earlier hits had been entries in the franchises that had traditionally driven New Line’s success: the Austin Powers series, the Nightmare on Elm Street series, and so on. Goodridge concluded that Summit and Overture would be major sources of quality films for the foreign market.

In early May, 2008, with Cannes looming, Variety ran a story about the opportunities opened by New Line’s departure from the market. The subtitle suggests how big the change was perceived to be: “Opportunities Rock: Fresh contenders eager to join international indie scene’s new world order.” The story speculated on the various independent sales groups that will be at Cannes and which ones might be strong enough to replace New Line: QED, with W, District 9, and A Perfect Getaway; Essential Entertainment, with My One and Only; The Film Department’s Law Abiding Citizen and The Rebound.

Swart also noted changes in two major suppliers to the indie market. Summit was growing, having opened its own domestic distribution wing. It “is chasing studio ambitions, which seems to have taken the main emphasis off foreign sales.” Mandate (notable for Juno and the Harold and Kumar sequels) had been acquired by Lionsgate in September, 2007.

Cannes also provided the occasion for a second in-depth analysis of the New Line void by Screen International. Author John Hazelton suggested that New Line’s regular supply of six to eight films to its regular distributors overseas benefited international indies as a whole:

Many sales executives, in fact, go further and suggest that by boosting the fortunes of the distributor partners with which it had ongoing output or package deals—companies including the UK’s Entertainment, France’s Metropolitan, Australia’s Village Roadshow and Spain’s Tri Pictures—New Line effectively elevated the independent international industry as a whole. Other sellers benefited, for example, when the New Line distributors reinvested profits from The Lord Of The Rings and Rush Hour movies—or from last Christmas’ The Golden Compass—in the acquisition of non-New Line films.

Hazelton quotes Steve Bickel, president of The Film Department’s international wing: “New Line provided a great service to all of us because they helped make strong companies that we’re now able to sell to.” The author also presciently singles out Summit and the newly merged Lionsgate and Mandate as “leading the field of remaining big picture suppliers,” noting that both companies had recently expanded into domestic distribution and were signing output deals in some foreign countries.

The article refers to The Weinstein Company and The Film Department as promising new players. Relativity, having produced Atonement, Evan Almighty, Baby Mama and Pineapple Express, was moving for the first time into international sales at Cannes. Other companies are mentioned as possibilities. Hazelton concludes:

On its own, Relativity probably will not fill the gap created by the disappearance of New Line from the business that A Nightmare On Elm Street, The Mask and The Lord of the Rings helped build. And neither will any of the other sales companies or producers now eyeing the fresh demand for upscale product from international buyers. But between them, the new entrants, growing boutiques and established players will be trying fill the New Line-shaped void appearing on the international sales landscape.

Reporting that autumn on the American Film Market, Screen International noted that The Weinstein Company had sold five films to Entertainment, formerly supplied by New Line. These included The Reader, Zack And Miri Make a Porno, and Piranha 3-D. Relativity had closed multi-year output deals with several overseas distributors, including former New Line customers Village Roadshow (Australia, New Zealand, and Greece) and Alliance Films (Canada). Neither company, however, would be the one to release the second indie blockbuster franchise.

From New Line to New Moon

In 2008, the world was in a global recession brought on by the financial crisis of 2007. But even as the trade press was speculating on which company or companies would replace New Line, help was on the way. Summit’s release of Twilight came in November of the same year, and although it did not make as much as the three following films in the franchise so far released, it grossed nearly $393 million internationally, $200 million of that outside North America. A healthy take for a film reportedly budgeted at $37 million.

The modest title did not indicate that Twilight was the launch of a franchise, though obviously Summit was hoping that it would be. The subsequent entries were more forthright and more lucrative: The Twilight Saga: New Moon (November, 2009, nearly $710 million worldwide), The Twilight Saga: Eclipse (June, 2010, about $700 million), and The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 1 (November, 2011, just over $705 million), with the final installment due out in November of this year.

On the occasion of the second film’s release, Mike Goodridge of Screen International noted that the franchise’s success echoed that of a certain earlier series:

Distributed in major territories by companies which had signed to output deals with Summit Entertainment for its in-house productions, the first film, Twilight, was a sensation buyers were hardly anticipating when they made the initial deals. [….] Seeing E1 Films take nearly $20m in the UK, SND in France scoring $17m, Eagle in Italy $14.3m and Aurum in Spain $13.7m last weekend brought back the heady days of The Lord of the Rings openings.

Goodridge also pointed out:

What The Lord of the Rings proved and the Twilight Saga reaffirms is that this kind of independent success is good for everybody. The Twilight distributors will have more money to invest in financing and acquisitions, benefiting other independent productions, while sales companies struggling to get films off the ground in a turgid distribution world will hopefully encounter a renewed buoyancy in the international markets.

He concluded, “For independents, the loss of New Line wasn’t as damaging as first imagined.” [“New Moon’s new line of success,” ScreenDaily.com, 26 November 2009.] It should be pointed out, though, that the gap between the third LOTR film and the first Twilight one was six years.

The Lionsgate share

On January 13, 2012, Lionsgate finalized its deal to buy Summit, thus acquiring the Twilight series. On March 23, Lionsgate released The Hunger Games, with an opening weekend of over $152 million domestically and a worldwide gross of $637 million after 9 weeks in release. Within less than three months, the company came to control the two largest indie franchises since LOTR. In late March, a financial analysis of Lionsgate by The Hollywood Reporter remarked, “The rest of the Hunger Games movies will now bring in significantly higher returns.” [Alex Ben Block, “How ‘Hunger Games’ Box Office Haul Impacts Lionsgate’s Bottom Line,” The Hollywood Reporter, 3 March 2012.] The reference was to the sales of foreign distribution rights, not higher box-office grosses.

Given how recent these events are, it happens that only two international distributors control both the Twilight series and The Hunger Games for their respective territories: Paris Filmes, of Brazil, and Nordisk Films, Denmark. Peter Philipsen, general manager for independent films at the latter told Variety that such series are rare: “There are not a lot of franchises in this business that really work, let along in the independent market,” Philipsen notes. “The last one before ‘Twilight’ was ‘Lord of the Rings,’ which was huge and gave a really big boost to the business as a whole.” [Diana Lodderhose and Adam Dawtrey, “International buyers eye bigger pics,” Variety.com, 5 May 2012.]

If Twilight helped ease the pain of the global recession for many indie distributors worldwide, by Cannes, 2012, the accumulating impact of its franchise and the addition of The Hunger Games led to greater prosperity. Those films and other successful non-franchise movies (some presumably bought with money from the Twilight franchise) led foreign distributors at this year’s Cannes festival to look for bigger films. Diana Lodderhose and Adam Dawtrey reported in Variety:

Sales agents brought a number of well-received big-budget projects to market last year, notably “Cloud Atlas,” “Pompeii” and “Enders Game.” But this year, with the indie sector stronger theatrically than it has been in years, and with international distributors flush with success from pics like the “Twilight” franchise and “The Hunger Games,” as well as “The Iron Lady,” “The Woman in Black,” “The Artist” and “Midnight in Paris” all having performed well territorially, there’s a feeling among buyers that bigger is better.”

A large number of new indie companies have emerged, many of them started by executives formerly at Summit, Lionsgate, and New Line. Among those represented at Cannes for the first time this year is Speranz13 Media, headed by Camela Galano, mentioned above as having helped arrange pre-sales for LOTR at New Line. Variety commented:

Pre-Cannes, a raft of new sales outfits headed by esteemed execs […], coupled with more money in the pockets of indie distribs who had successful runs with such pics as the latest “Twilight” installment, “The Hunger Games” and “The Intouchables,” suggested that this would be a market with greater liquidity.

And it has been.

“Many indie buyers have money now and they know what they want, which is studio-level movies,” said Foresight’s Tama Stuparich de la Barra, whose projects “Lone Survivor” and “Motor City” sold out at the market. [Diana Lodderhose and Dave McNary, “Cannes market totes up solid business,” 21 May, 2012.]

One notable aspect of all this is a return to pre-sales for financing big independent films. A few years ago, pre-sales were declared dead, partly because distributors couldn’t afford to invest in unmade projects. Lionsgate, however, financed about 60% of The Hunger Games through the sales of individual foreign sales rights. Production rebates from North Carolina kept the film’s budget at a relatively modest $80 million, limiting the studio’s risk on the film. These strategies are similar to what New Line tried while making LOTR.

I have yet to see coverage of Cannes that explicitly dubs Lionsgate the successor to New Line, the new indie “mini-major” that will supply a steady stream of films to foreign distributors with which it has output deals. Still, the conclusion seems all but made. At Cannes it began pre-sales for Catching Fire, the sequel to The Hunger Games. On May 23 it announced a long-term renewal of its partnership with the powerful French producer-distributor StudioCanal, including a deal for StudioCanal to distribute Catching Fire in German-speaking regions. Under this partnership Lionsgate has certain distribution rights to StudioCanal’s huge library of film and television titles, the third largest in the world, including titles ranging from Grand Illusion and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie to Terminator 2 and The Deer Hunter. [Dave McNary, “Lionsgate, Studiocanal extend pact,” Variety.com, 23 May 2012] On May 24, Screen International summed how various sales for various companies at Cannes were going:

Patrick Wachsberger and Helen Lee Kim reported a roaring trade on the Lionsgage slate, especially the Dirty Dancing remake. “It has been a strong market for us and the team has been seamless,” Wachsberger said of the post-merger infrastructure. [Jeremy Kay, “Market buoyed by sellouts,” 24 May 2012, p. 1.]

No doubt at some point Lionsgate will face a financial crisis and lose its central status, but with two big indie franchises in progress, it seems settled for the foreseeable future and beyond.

Ironically, the blockbuster franchise that started it all will resume this year, but not in the indie sector. The two parts of The Hobbit, due to be released in December of this year and 2013 as prequels to LOTR, are being produced by New Line. They are not being financed by pre-sales to indie distributors around the world. Instead Warner Bros. is providing funding, and it will also distribute.

I have linked to stories when I could find them online, but some articles I quoted are either behind paywalls or simply not online. They are taken from issues of the trade papers mentioned in the text.

The illustration at the top of the entry topped an article called “Hey, Big Spenders,” cited above. It appeared in The Hollywood Reporter (February 2003), pp. 1, 4, 8, 12. The piece dealt with the American Film Market, which at that time still happened in the spring. Naturally the caricature of Frodo tossing money around caught my eye. (The distributors flush with LOTR cash are, left to right, Joel Pearlman of Roadshow Films, Australia (?); Trevor Green of Entertainment Film Distributors, UK; and Hiromitsu Kurukawa, Nippon Herald Pictures, Japan.) This was one of the few articles I found in the trade press that dealt with the considerable impact that LOTR had on the international indie and foreign-language film market. I used the caricature as an illustration in Chapter 9 of my book. After all, how do you illustrate the concept of a film helping pull the indie business out of a global slump? That picture was ready-made for such a topic. I contacted the artist, Victor Juhasz, for permission to reprint the image, which he kindly gave. It occurred to me that he would be the ideal person to provide an image for the cover of the book as well. Again, how do you illustrate the general concept of a franchise based on The Lord of the Rings? Have a character surrounded by licensed products based on that character, I figured. Fortunately the University of California Press agreed. Based on photos, an action figure, a polystone collectible bust, and a video-game strategy book that I sent him, Victor produced exactly what I had in mind. A small image of that cover illustration appears up at the right, beside the Hollywood Reporter caricature.

PANDORA’s digital book

DB here:

Looking back at Kristin’s and my ventures online, I see a gradually expanding series of experiments. Step by step, maybe too cautiously, we’ve moved toward what you might call “para-academic” film writing–a way of getting ideas, information, and opinions out to a film-enthusiast readership whom we hadn’t reached with our earlier work. (Although we’re happy when academics take note of what we do.)

Today we have a new experiment to try. Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies is now available here. Backstory follows.

Baby steps, then longer ones

To take another metaphor, we’ve been gradually exploring various niches in the online ecosystem. At first, back in 2000, knowing almost nothing about cyberculture, I dumped my vitae and a little essay onto my brand-new Geocities site. Later I saw the site mainly as a supplement to print publication, a way to add and correct things I’d written in my books Figures Traced in Light (2004) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (2005), along with material we’d included in our textbooks Film Art and Film History. By then I had retired from teaching.

I started to write more online. I began posting long, stand-alone pieces that I couldn’t imagine any journal or anthology publishing. (They’re in the list on the left-hand column of this page.) Somewhere around 2007, after finishing the collection Poetics of Cinema, I made Web publishing my primary expressive vehicle. So when I was asked to write pieces for various occasions, I tried to secure permission to publish them here as well. They too have wound up in the line-up on the left– a little essay on Paolo Gioli, one on Shaw Brothers’ widescreen cinema, and a liner note about The Mad Detective for the Masters of Cinema DVD line. There are more to come in this vein, including a historical survey of how film theorists have drawn ideas from psychological research.

While moving to fill the essayistic niche, we saw archival and revival opportunities as well. Thanks to Markus Nornes, I was able to republish the out-of-print Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema in a downloadable pdf version, with color illustrations. That’s on the University of Michigan Press site. Vito Adiraensens, who made a pdf of Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment, allowed us to post that on our site.

At this point, whole books we’ve done were available online. But those were straight reprints. The next logical step was to offer a revised edition. After the rights to Planet Hong Kong (2000) reverted to me, I decided to update and expand it and add color illustrations. I also decided to ask for money, making PHK 2.0 the only item on the site that wasn’t free. That was an experiment too, to see if the year I spent reshaping it might yield some payback. It did; so far, the sales have covered the costs of design and yielded me a little for my efforts.

Meanwhile we’ve explored the blog niche. Started in 2006, refreshed once or twice a week, our blog has become greatly satisfying to us. This entry is number 499. We’ve treated the blog wing of the site as a sort of magazine, with each entry as a feature or column or festival report or book notes. We write about anything cinematic, old or new, that interests us. The freedom is exhilarating, and we don’t lack ideas. I have a desk drawer’s worth of folders on topics I want to explore.

Nearly all of these are long-form endeavors. Some run to 6000 words. Even our festival reports, which could have been emitted in a flurry of communiqués, are blended into spacious pieces that permit us to compare films or develop a common theme. At a time when everyone declares that attention spans have shrunk to pinpoints, readers have been very patient with us. People still visit our blog, recommend it to others, and even Facebook and Tweet about it. Roger Ebert has been an especially generous supporter. Thanks to the efforts of Rodney Powell of the University of Chicago Press, we gathered some of our entries into a book, a “real” one called Minding Movies, and I’d hope that the length and contextual depth of the pieces gave them some bookish solidity.

Another niche coming up: As virtual books have found a public, I’ve made a book designed primarily for an e-reader.

Not bloviation, blogiation

Last fall, after realizing the scope of the digital conversion of movie theatres, I decided to write a series of blogs about it. I had no fixed number in mind, but I didn’t expect it to run as long as it did. I kept learning more, so the series, called Pandora’s Digital Box, stretched from December through March. I was encouraged by people who praised it in blogs and on social media. I decided to try to build a book out of the pieces.

Some people think that this is silly. One reviewer of our blog book, Minding Movies, wondered why anyone would buy something that’s available for free. More alert reviewers, like Scott Foundas of Film Comment (May/June 2011), understood that some readers don’t like to read long-form prose online, or don’t like zigzagging through the labyrinth that is our site, or want some guidance in selecting what to pay attention to. Moreover, by gathering items topically, the book suggested recurring themes and an overall frame of reference governing what we do. The broad aims of our enterprise aren’t apparent in a daily skim of each entry.

Still, Minding Movies was a varied mixture. Pandora was from the start a more focused series. And we added no new essays for our collection, but I had quite a bit more to say about the digital conversion. So I cooked up new rules for my latest experiment.

1. The original entries wouldn’t be taken down. As with Minding Movies, the entries will remain available online.

2. The book wouldn’t be simply a blog sandwich. I’ve rewritten, rearranged, and merged entries for smoother reading. The topics are more logically ordered, and the whole thing hangs together organically. The blogs formed a kaleidoscope; the book is a narrative.

3. The book would have lots of new material. It includes things I didn’t know when I wrote the blog, ideas that have come to me since, and as much background and context as I could supply. The original blogs amounted to about 35,000 words (enough for a Kindle single). The finished book runs over 57,000 words.

4. It wouldn’t be an academic book. It’s written in the same conversational tenor as the blog. I try not to make anybody’s head hurt. No footnotes, but….

5. The book would exploit online access. The text is unsullied by links, to promote continuity of reading. But a section of references in the back contains citations and hyperlinks to documents, interviews, sources, and sites of interest. This section tells you where I got my information and, if that information is online, takes you there.

6. The book would have to be for sale… Part of this experiment is to see whether I can make back what I’ve spent on the project. I reckon that my travel to theatres and events like the Art House Convergence in Utah, along with other expenses like paying our Web tsarina Meg to polish up my self-designed Word book, comes to about $1200. In addition, I’d like something for my extra time and effort.

7. …but not cost too much. Planet Hong Kong 2.0 runs $15, which I think is a fair price given the cost of designing a book with hundreds of color pictures. But Pandora is a lot simpler and has only a few stills. So I’m offering it for much less: $3.99.

Another Whatsit, but only $3.99

Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies traces how the digital conversion came about, how it affects different sorts of theatres, how it shapes the tasks of film archives, and what it portends for film culture, especially the culture of moviegoing.

A key concern was trying to go beyond what I’d already written. For one thing, I try to answer questions I didn’t pursue in the blog entries. How did the major distributors orchestrate the transition? How did they reconcile the interests of the various stakeholders—filmmakers, theatre owners, manufacturers? By 2005, the specifications for digital cinema were established, but the real uptake came five to six years later. What led to the delay? How was digital cinema deployed outside the US? And so on.

Second, I provide background and context for areas I surveyed quickly online. For example, instead of sketching how a movie file gets projected, I take you into a booth and we follow the process step by step. The chapter on small-town cinemas reviews the role of single-screen theatres in the industry. The chapter on art-house cinemas goes back to the 1920s and shows remarkable continuity of taste and business tactics up to the present. Throughout, I consider how the US exhibition system has worked since the rise of multiplexes.

Third, there are unexpected tidbits. How did celebrity directors like Lucas, Cameron, and Jackson spearhead the shift to digital and later innovations? (I touched on that in a couple of recent entries here and here, but there’s more in the book.) Who invented multiplexes? Cup holders? When did those annoying preshow displays start, and more important, who controls them? How do distributors decide whether to release a movie wide or to let it “platform”? Why do art-house theatres serve coffee? There are even a couple of jokes (maybe more unintentional ones).

I think it has worked out well. I’ve tested the text on Kindle, Nook, and the iPad, and it fits very snugly. You just have to import it as a pdf from your computer. On the iPad, it seems to work particularly well with the app GoodReader, which permits smooth searches, easy bookmarking, and quick shifts back and forth.

As I mentioned above, you can go here to order the book. On the same page you can examine the Table of Contents and a bit of the Introduction.

It’s possible that some people might want to make a bulk purchase. Pandora might be used in a class, or given to staff members working at a film festival, or presented to members or patrons of an art house. For such worthy purposes, I can make the bulk price quite low. If you’re interested, please write to me at the email address above.

Self-publication is a risk for both author and reader. If you decide to buy the book, I thank you.

The next logical steps? A new ecological niche? A completely original book online, maybe. Or PowerPoint lectures with voice-over. Who knows? As Jack Ryan says at the end of The Hunt for Red October: Welcome to the new world.

Thanks as usual to our Web tsarina Meg Hamel, who did her usual superb job turning Pandora the Blog into Pandora the Book, and who has set up the payment process to be quick and easy. Earlier helpmates were Vera Crowell and Jonathan Frome, whose efforts in creating this site are remembered and appreciated.

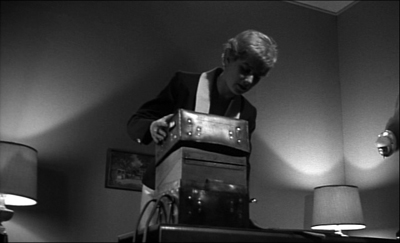

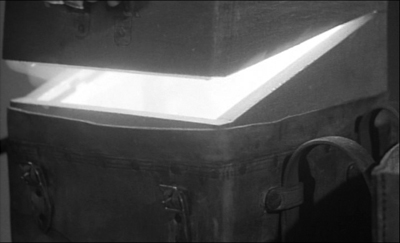

The illustrations are from Kiss Me Deadly and Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, but you knew that. Thanks to Jim Emerson for his suggestions.

The Gearheads

Mourning.

DB here:

At the Wisconsin Film Festival I saw the best film I’ve seen over the last six months. I can’t really say much about it, but I’ll do what I can. My remarks make most sense, I think, if I embark on a pretty long detour.

The frame-rate shuffle

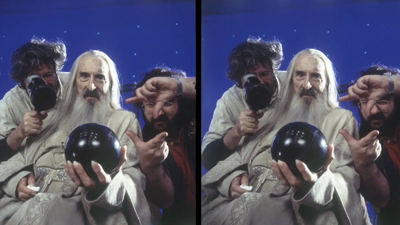

3D still photographs by Peter Jackson taken during the filming of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the wake of April’s convention of the National Association of Theater Owners, the biggest press tumult surrounded Peter Jackson’s ten-minute demo from The Hobbit. Fulfilling what James Cameron had called for at the 2011 NATO confab, Jackson has been shooting at 48 frames per second, and the demo was screened at that rate. Cameron and Jackson are concerned that there’s too much image judder and strobing in digital cinema, especially 3D. They propose a higher frame rate to smooth things out.

Opinion on the Hobbit footage was divided. Some theatre owners and operators were happy with it, but others were uneasy. The higher frame rate tends to eliminate motion blur and create a sharpness that recalls, for some viewers, the brittle look of HD sports broadcasts. “It looked to me like a behind-the-scenes featurette,” said one.

Jackson, who has been preparing for this initiative on his Facebook page, defended his decision. He maintains that audiences will adapt to it, just as his production team has. Many exhibitors seem to have dismissed the new initiative as too expensive, particularly at a time when many are still paying off the digital conversion. But the Regal Entertainment Group, the largest cinema chain in the US, announced plans to outfit up to 2700 screens so that The Hobbit can be screened at 48 fps. It now seems possible that The Hobbit may be shown in no fewer than six formats: 2D, 3D, and Imax, and in each there will be both 24 fps and 48 fps presentations.

Not being present to watch the footage, I have to withhold judgment about how it looks. I haven’t though, withheld my opinion about how Cameron and Jackson, along with George Lucas, have used their roles as superstar directors to prod exhibitors to adopt expensive new technology. They acted as the figureheads for the switch to digital in 2005, using 3D as the incentive for exhibitors to convert. A few years later, after proposing 3D television, Cameron upped the ante by urging higher frame rates for film. Jackson has joined him by actually making a film at 48 fps. Cameron has said he prefers 60 fps, which may mean that the goal posts get shifted again when Avatar 2 or something else comes along.

You can go to my earlier post for more thoughts on their tactics. My book on the digital conversion, due out on this site in a few days, offers a fuller account. In the meantime, I’m going to try to understand this frame-rate fracas in a wider historical context.

The palette

Cinema technology has been surprisingly stable, as befits its status as the last surviving nineteenth-century engine of popular entertainment. The dimensions of the film strip, the rate of shooting and showing, and other fundamental factors have altered relatively little. The coming of sound and then the replacement of nitrate-based film by acetate are perhaps the biggest alterations in the basic technology. Below this macro-level, though, innovation has been constant.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, most of the change came in the production sector. The adoption of panchromatic film stock; color processes, principally Technicolor and the monopack systems like Agfacolor and Eastman Color; the development of various lighting units (carbon-arc, incandescent, Xenon); the shift from optical sound recording and reproduction to magnetic processes; the emergence of different sorts of camera support (varieties of tripod, dollies, and cranes, along with handheld devices)—all of these shaped how movies were made but had relatively little effect on how they were shown.

Some 1950s innovations launched in the production sector, notably widescreen cinema, stereophonic sound, and 3D, reshaped exhibition more drastically, because they came at a moment when theatres were anxious to lure back their clientele. Other revampings of exhibition, like wide-gauge film (65mm/70mm) and Cinerama, were never intended to be the universal standard. They were designed for a distribution system that included roadshow exhibition. Dedicated screens showcased big films like The King and I and Lawrence of Arabia for long, well-upholstered runs before the film hit the neighborhoods and the suburbs.

Producers innovate and exhibitors hesitate. Exhibitors must be cautious and conservative; they risk revamping their venue at great cost only to find that the new technology isn’t catching on. The roadshow system repaid exhibitors well, until it collapsed in response to the rise of saturation booking in the 1970s. For similar conservative reasons, exhibitors looked askance at the digital sound reproduction technologies that emerged from the 1970s through the 1990s. At one point, a house had to accommodate four different sound systems, some of them subject to periodic upgrades.

When technologies emerge in the production sector, they mostly promise to enlarge the filmmaker’s palette. A 1950s film could be made black-and-white or color, deep-focus or soft-focus, with arc or incandescents, flat or anamorphic, and so on.

In practice, of course, not everything was possible on every project. Budgets, as ever, limited options, and many directors and DPs disliked shooting in color or CinemaScope but were obliged to do so. And there were some trade-offs. Filmmakers of the 1930s could not shoot on orthochromatic stock, and after the mid-1950s, it was hard to make a film destined for the classic 1.37 Academy ratio. Still, there were few absolutely forced choices, and many directors explored different options from project to project.

The prospect of an enhanced palette is in fact one reason that some filmmakers embraced new technologies. Sergei Eisenstein (who trained as an engineer) was eager to try out sound, color, and even television because they expanded creative choice. Orson Welles saw in the RKO effects department, which had pioneered sophisticated optical-printer work, a way to create images that couldn’t be generated in the camera. As is now widely known, many of Citizen Kane’s most famous “deep-focus” shots were achieved through special effects. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick renewed the power of his images through his eager adoption of new technologies, including long lenses for Paths of Glory, the handheld camera in Dr. Strangelove, faster lenses for Barry Lyndon, and the Steadicam for The Shining. These filmmakers wanted to multiply options, not foreclose them.

Share our fantasy

The changes that Cameron and Jackson propose are more sweeping. Now that digital projection is an accomplished fact, there will be backward pressure to create a wholly digital workflow. Filmmakers who want to shoot on 35mm will be reminded that they will eventually be fiddling with a digital intermediate, and that the final version will be digital, not film-based. A selling point of digital cinema to the creative community was the promise of complete control over the film’s look and sound, so that the audience gets exactly what the filmmaker envisioned. To assure that integrity, the director will have to shoot and finish the project on digital. That will take away an entire dimension of choice—specifically, shooting on film.

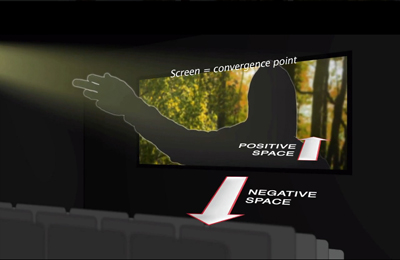

The pressure to shoot 3D adds to this. Martin Scorsese and Ang Lee showed up at the same NATO convention to praise the format. Now films that aren’t tentpole items can be made in 3D, they agreed. According to Variety, Scorsese claimed that “2D projection [sic] will eventually go the way of black-and-white—used primarily as a stylistic choice—as auds will soon acclimate to depth even in indie films.” This sounds like a widening-of-the-palette defense, as does his reaction to new frame rates. “You can do anything you want [in post-production] with that image at that level of clarity, can’t you?”

In contrast to Scorsese’s offhand pluralism, Cameron, Jackson, and their confrère Lucas may be creating a scorched-earth policy. Their conception of cinema, I would say, is now largely that of the Gearhead. Their notion of artistry has become quite mechanical, in that they see progress to depend almost wholly on improved hardware (and software).

They represent three mini-generations of Hollywood techno-lover: Lucas, who began in animation; Cameron, who started as a model-builder; and Jackson, the 1980s fanboy who played with King Kong action figures. They are directors who treat cinema as a delivery system for stories grounded in genre conventions. Fantasy is their touchstone, and realism of any sort bears only on how vividly we perceive the images, not what the films show or say or suggest.

Back in 1999, Lucas noted frankly that film was becoming a form of painting, “unfixing the image.”

You have news footage, you have documentary footage—which are supposedly realistic images—and then you have movies, which are completely fantasy images. There’s nothing in a movie that’s true or real—ever . . . . The people in the movie are actors playing parts. The characters are not real. The sets are not real. If you go behind that door you’ll see there’s no building—it’s just a big flat piece of wood. Nothing is real. Not one little tiny minutia of detail is real.

The Hollywood cinema was then putting fantasy and special effects at the center of its aesthetic, and Lucas understood that every film—action picture, romantic comedy, even dramas—would rely on special effects to a new extent.

Here’s Cameron saying the same thing in defending 3D in 2008.

Godard got it exactly backwards. Cinema is not truth 24 times a second, it is lies 24 times a second. Actors are pretending to be people they’re not, in situations and settings which are completely illusory. Day for night, dry for wet, Vancouver for New York, potato shavings for snow. The building is a thin-walled set, the sunlight is a Xenon, and the traffic noise is supplied by the sound designers. It’s all illusion, but the prize goes to those who make the fantasy the most real, the most visceral, the most involving. This sensation of truthfulness is vastly enhanced by the stereoscopic illusion.

It’s hard to believe that Lucas and Cameron don’t know the long tradition of debate in the arts about realism. Realism can be considered a question of subject matter, plot plausibility, random detail, psychological revelation, and many other things; it isn’t just about trompe l’oeil illusion. Moreover, documentary and experimental filmmakers have suggested that cinema can capture moments of unplanned truth. And André Bazin and others have argued that even when presenting fictional tales, photographic cinema gives us unique access to some essential qualities of phenomenal reality. For Bazin, even an awkwardly shot scene could preserve the sensuous surface of things with a conviction that no painterly manipulation can equal—not perfection but brute facticity. Instead, Lucas and Cameron offer a Frank Frazetta notion of realism: glistening, overripe, academically correct rendering of things we’ve seen many times before.

Turnstile dynamics

NATO’s 2005 ShoWest convention: Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, Randal Keiser, Robert Rodriguez, Cameron.

I see a valid place for a cinema of splendor and spectacle, especially in certain genres. There’s nothing wrong with seeking new methods of pictorial representation, as Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, a genuine triumph of veridical realism. Nor am I trashing Lucas and Cameron wholesale; I admire their early films a fair amount. But they’re forcing their conception of cinema on all filmmakers.

Am I being unfair? I don’t think so. When directors say that digital or 3D or 48 fps is the future of cinema, they’re implying wholesale conversion is in the offing. Although Scorsese says that 2D or another frame rate will remain an option, Cameron and Jackson aren’t quite so open-handed. Because they’re convinced that the result is much more immersive, and immersion is always good, the technology should suit every kind of movie. Cameron again:

It is intuitive to the film industry that this immersive quality is perfect for action, fantasy, and animation. What’s less obvious is that the enhanced sense of presence and realism works in all types of scenes, even intimate dramatic moments.

Both directors usually add that they’re not insisting that every film is suited to the new bells and whistles, that it has to suit the plot and so on—the usual boilerplate about the primacy of “story.” “Stereo [imagery] is just another color to paint with,” says Cameron.

But they sound as if not having 3D or 48 fps puts the movie at a disadvantage. Cameron in 2008:

Every time I watch a movie lately, from 300 to Atonement, I think how wonderful it would have been if shot in 3D.

Jackson in 2011:

You get used to this new look [48 fps] very quickly. . . Other film experiences look a little primitive. I saw a new movie in the cinema on Sunday and I kept getting distracted by the juddery panning and blurring. We’re getting spoilt! . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re headed toward movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates.

As happened before, the pronouncements of the directors mesh well with the initiative of the manufacturers. Back in 2005, Cameron, Lucas, Jackson, Robert Rodriguez, and Bob Zemeckis took to the NATO stage to help sell the Digital Cinema Initiatives program to skeptical exhibitors. Their support (and the box-office numbers of the 3D Chicken Little) aided the projector manufacturers Christie, Barco, NEC, and Sony in rolling out units. The number of digital screens in the US and Canada jumped from ninety in 2004 to over 300 at the end of 2005.

This year, with about two-thirds of all US screens fully converted, Christie circulated a promotional leaflet tied to Jackson’s demo. A few years ago, the future was all about 3D, but now, the text states flatly, “The future of cinema is all about high frame rates.” The cards are on the table.

At just 24 FPS, fast panning and sweeping camera movements that are a critical part of any blockbuster are severely limited by the visual artifacts that would result. . . .

The “Soap Opera Effect” has been derisively used to describe film purist perceptions of the cool, sterile visuals they say is [sic] brought on by digital.

But the success of Hollywood, Bollywood and big-budget filmmakers around the world has little to do with moody art-house films. The biggest blockbusters are usually about immersive experiences and escapism—big, vibrant, high-action motion pictures.

The HFR system, then, aims to spiff up franchises and tentpoles, and all other filmmaking must be dragged along and adjust. Although Jackson says he has heard no plans to charge more for 48 fps shows, Christie thinks we would pay for this treat:

Beyond the simple turnstile dynamics of “must-see” movies, a new, higher standard of movie-going should support premium pricing. Managed right, hotly-anticipated 3D HFR should empower ticket up-charges.

By all signs, the churn won’t stop. “Every three months you’re behind,” says Ang Lee. “We’re guinea pigs.” David S. Cohen, technology writer for Variety, believes that 48 fps is a transitional technology and that 60 fps will win out (“but not soon”). He adds: “Bizzers in both TV and movies are going to be making creative and financial decisions about HFR for years—maybe forever.”

Lucas and Cameron, and then Jackson, grasped that if cinema technology went wholly digital, it would change in fundamental ways. It would turn a medium into a platform, like a computer operating system. The most basic technology of showing a movie would become subject to rapid, radical, ceaseless remaking. It would demand versions, upgrades, patches, fixes, tweaks, and new software and hardware indefinitely.

I’m not sure that NATO’s members have fully realized this. They went into the deal lured by the chance to raise ticket prices and thus offset flat or slumping admission numbers. But attendance is still stagnant, even with the occasional stupendous successes like Avatar and The Avengers. Interestingly, AMC, one of the Big Three circuits that invested heavily in digital projection, is reportedly in talks to sell out to Chinese investors, and other chains are on the auction block. The studios are proceeding with VOD plans that may thin theatrical attendance even more.

Meanwhile, exhibitors face a long future of payouts. When cinema goes IT, as Steve Jobs might put it, we should expect a big bag of pain.

And now for something completely different

I saw Morteza Farshbaf’s Mourning (Soog) on a so-so DigiBeta copy at the Wisconsin Film Festival. This Iranian feature was shot on some godforsaken digital format, certainly nothing that Cameron and Company would approve. For all I know, its camera movements may have strobed unacceptably. I didn’t care.

Cameron et al. claim to worship the god of Story, but no film they’ve made has this subtle a grasp of narrative. Mourning gives us a plot so full of twists—in terms of what happens and how we learn about it—that I can’t summarize even the basic situation without subtracting some of your pleasure. A man and a woman are driving a little boy through a landscape. That’s about all I can tell you.

The film critics at Christie would consider it a moody art-house film. It’s also simple, suspenseful, and surprising, even shocking. It is formally inventive, emotionally poignant, and respectful of its characters and its audience. It is gentle but also unflinching. It’s the closest thing to Chekhov I’ve seen onscreen in a long time.

Was I immersed? Yes, but not in the way Cameron et al. define that state. I was trying to figure out what had already happened, what was happening at the moment, and what might happen next. And maybe I wasn’t seeing things “realistically,” in the 3D sense, but I was seeing something that captured the world we live in—our surroundings (and their stubborn physicality) and our relations to others. That world was also poetically heightened through the most straightforward means: camera placement, lighting, cutting, sound design. The film was, in other words, working in ways that we have always considered central to cinema’s creative mission.

Mourning is part of the fine Global Lens program of circulating features. Here’s a schedule of where and when films in the program are playing. Ask your local festival or art house to book Mourning, or try to see it when it’s available online or on disc. It’s even worth an upcharge.

Lucas’s remarks on realism come from “Return of the Jedi,” an interview with Don Shay in Cinefex no. 78 (July 1999), 18. Figures on the adoption of digital cinema are taken from the report, “Digital Cinema Roll-Out Begins,” Screen Digest (April 2006), 110. A detailed video explaining Hobbit production methods is here, as part of the video diaries on Jackson’s Facebook page. For more from a veteran, see “‘The Hobbit’: Douglas Trumbull on the 48 Frames debate.”

After writing this, I found that Devin Faraci of Badass Digest has a vigorously critical entry on the footage and even calls Jackson and Cameron “gearhead directors.” So I can’t claim originality, but it’s nice to know I have a badass ally.

Thanks to Jim Cortada, author of the forthcoming Digital Flood and Co-Director of the Irvington Way Institute, for explaining IT matters to me.

P.S. 11 May: Christopher Nolan, still embracing film-as-film, claims he’s no gearhead.

Pandora’s digital box: Harmony

DB here:

I had thought I was finished with my series on digital projection that started back in December. That was before a late-night trawl of the Internets brought the JEM Theatre to my attention. Sometimes reality has a taste for a dramatic story, and this was one I couldn’t resist.

So I went to Harmony.

All in the families

A birthday party at the JEM Theatre.

For decades exhibiting movies has been a family business. Many regional chains were founded by fathers and brothers and staffed by sons, daughters, and in-laws. The Midwest’s Marcus chain of 700 screens originated in 1935 with grandfather Ben and is run by son Stephen and grandson Gregory. More modestly, Smitty’s Cinema, a nine-screen movies-and-eats circuit in Maine and New Hampshire, was the brainchild of three brothers.

The smaller the venue, the more likely you’ll find a family in charge. The Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin, which I profiled earlier, has been in the family from the start. The single-screen Cozy in Wadena, Minnesota, has been run by the Quincers since 1923, with the founder’s great-grandson in charge today. Dirk and Jeri Reinauer have the Sunset Theatre in Connell, Washington. Tom and Barbara Budjanek, who bought Pennsylvania’s Ambridge Family theatre in 1967, are still running it in 2012.

Families pass theatres to each other. The venerable Roxy in Forsyth, Montana, was bought by a couple in 1967. They sold it to their projectionists, one of whom kept it going with his wife. (The theatre went digital in 2010, just in time for its eightieth birthday.) From 1947 to 1959 the Wayne Theatre in Bicknell, Utah, was operated by a husband and wife. Another couple bought it and ran it until 1994, when they sold it to a third husband and wife. A fourth family acquired it in 2008.

The record for husbands and wives running a single-screener might be held by the little town of Harmony, Minnesota. The JEM Theatre on the main street, closed in 1947, was reopened by Bob and Hazel Johnson in 1961. They ran it for twenty-five years. It passed through the hands of five more couples before Michelle and Paul Haugerud acquired it in 2002.

Paul and Michelle met in San Francisco, where Michelle was working for Bear Stearns and Paul had served in the Navy. In 1994 they moved to Harmony to be near Paul’s family. There they raised six children while Paul started a paint and drywall business and Michelle began a career in Web design. “When we bought the theatre,” Paul explained, “we knew it was gonna make no money. We knew it was gonna be basically like doing community service.”

To an extent that people living in cities and suburbs may not appreciate, the JEM has held a central place in the life of the town. By 2011, digital conversion threatened to end that.

Harmony, not far from Prosper

With a population of about a thousand, Harmony sits in farm country close to the Iowa border. As Prairie Home Companion reminds us every week, people of Norwegian descent are found all over Minnesota. What you may not know is that certain areas are also home to Amish communities. Waves of migration made Harmony a center of Minnesota’s Amish culture. Local businesses serve the five hundred households in the town, and tourism brings in some income too. One of the big attractions is Niagara cave, containing fossils pre-dating the dinosaurs. There’s also a major biking trail and a fall foliage tour.

The JEM was named, supposedly, for the first letter in the names of the original owner’s three children (but see the PS below). It helped knit the town together, and under the Haugeruds it became a unique institution.

They made a solid team, with Paul’s expertise in carpentry and engine repair matched by Michelle’s money-management skills. Paul, with no previous theatre experience, learned to thread up the platter projector. “The first few weeks, I would literally sit there with sweat rolling down my face as I pushed the start button. I’d be so nervous I did something wrong.” Paul introduced screenings with announcements and jokes. The Haugeruds knew most of their patrons, but at every screening there were fresh faces from nearby towns in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.

The JEM screened only on weekends, once each day at 7:30. Paul’s and Michelle’s day jobs made any other schedule impossible. During football season, Fridays brought in few teenagers, but Saturdays were better and Sundays were quite good. Overall, the 200-seat house averaged around 55 each night. On snowy nights, a few souls still braved the Minnesota winter to come see a movie.

The Haugeruds ran the JEM as a family business. There was no paid staff. The Haugerud kids sold tickets and snacks and helped with cleanup. Friends and volunteers came out as well. Michelle made the pre-show video slides of ads for local businesses. Even with low overhead, the theatre barely broke even. All tickets were $3. “We’ve always kept prices low,” Michelle explained, “so families that are financially hardshipped can still get their kids out of the house.”

Most of the JEM’s programs were subruns—movies that had opened nationally two or three weeks before. To avoid courier service costs, Michelle and Paul would make midnight drives to pick up prints from other towns. “I’d call and they’d just be breaking down their print from their last show on Thursday,” she says. “I’d say, ‘I’ll be there in fifteen minutes,’ and at midnight I’d go get the print for Paul to make up on Friday.”

Snack concessions are the core of every theatre’s income, but even here Paul and Michelle offered deals. They priced their candy at a dollar and a big tub of popcorn at four bucks. Soda was sold in plastic bottles, to allow for recycling and to keep costs down. Instead of getting concession items from theatre suppliers, Michelle bought them in bulk at Sam’s Club.

The JEM popcorn developed a following. High schoolers came to pop and bag it for football games. Paul and Michelle encouraged people to bring their own buckets to be filled with corn at a fixed price; some people showed up with shopping bags. The Amish didn’t come to the films, of course, but on some days you could see a horse and carriage lingering outside while the driver was buying a supply of popcorn.

The Haugeruds were generous with free passes as well. Over the years, they have donated hundreds of free passes to help local organizations raise money. At other times, Michelle realized, passes are a good form of marketing. “Give out one, and three more people will come along to pay.”

The JEM wasn’t just for movies. Youth groups held meetings there. Many local kids had their birthday parties there, accompanied by a movie or a videogame. The Haugerud daughters had slumber parties in the auditorium; after a movie, they settled down, if that’s the right word for a slumber party, in sleeping bags down front and in the aisles.

Many in Harmony believed that the JEM brought business to town. Julie Barrett, owner of the Village Square Restaurant across the street (and famous for her daily pies) said, “When people go to the movie, they stop at the Kwik Trip, our hardware store is open until 6:30, so you know they might try to kill two birds with one stone when they come to town.”

Over the situation hovered the fate facing every small town—the hollowing out of the center by the big-box stores down the road. Pull off any interstate highway, and you’ll see that the main streets of small towns have turned into empty storefronts, municipal offices, or struggling boutiques. When the JEM faced the need to go digital, Paul was concerned. “If we take one more thing away it’s going to hurt the community. I’m scared to death that main street is going to look like Harmony in the 1980’s when I was growing up. It was pretty bare.”

Single-screeners

Tonja Lawler selling tickets, Michelle Haugerud selling concessions.

The major distributors and the National Association of Theatre Owners now seem to take for granted that thousands of screens will close over the next few years. Some will fail to convert; others will struggle to pay for the conversion but still fold up. What are the likeliest victims? Those at the bottom of the food chain, the single screens and the “miniplexes” holding between two and seven screens.

These two categories account for over half of all exhibition sites in the US. But they amount to only a small slice of the total number of screens, which is what matters. And the number of small houses is shrinking. During the bankruptcy convulsions of the 1999-2001 period, circuits shed hundreds of screens. Since 2007, the total number of U. S. screens has remained fairly constant, but multiplex and megaplex installations have swollen by 2000 screens. Smaller facilities have lost about the same number—by going out of business.

Hollywood, people like to say, doesn’t want to leave money on the table. But more and more the long tail is a waste of resources. Why bother to prepare and ship a DCP to a theatre that yields a box-office take of less than $300 per day? Many decision-makers among the major distributors would be just as happy to let people in small towns wait a couple of months and catch the film on VOD or disc (rented from a gas station, since the video stores are gone too). As long as the megaplexes publicize the must-see movies, people will know what to buy or rent or stream. If you live in the countryside and you really feel the urge to catch the latest hit, get in your car or pickup and drive an hour to a ‘plex. No vehicle? Too young to drive? Wait for the video.

While digital projection allowed the major distributors to consolidate their power, it also offered a way to streamline and downsize exhibition. The 1600 American single-screen venues are especially vulnerable. For the industry, it seems, any part of film culture that preserves some history or takes root in a community is simply a nuisance. Michelle Haugerud puts it simply. “They don’t care if we go out of business.”

A digital jug

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

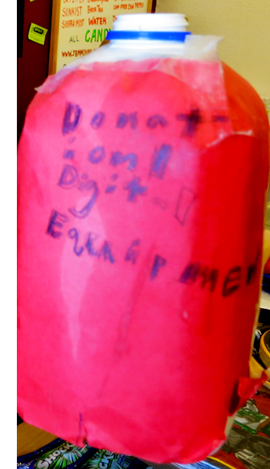

They began a fundraising drive. A young patron named Kirsten Mock decorated an old red juice jug for donations and put it on the candy counter. Paul and Michelle set up a designated savings account with a local lawyer’s name attached to make sure people understood that any donations would go only to the projector. A list was kept of all who put their names on donations, and the money would be refunded if the target sum weren’t reached.

The problem was that the JEM, privately owned and operated, wasn’t a nonprofit. Donations were not tax-deductible, and local government agencies couldn’t normally supply grants or other aid. During 4 July celebrations, however, a “Harmony Goes Hollywood” event featured a room in the Historical Society set up with an old projector and theatre seats, with clippings and photos showing the JEM over the years.

A local woman tipped Twin Cities media to the campaign. It was good timing: The US press was starting to notice the nationwide digital conversion. News outlets and TV stations covered the JEM’s crisis. Minnesota Public Radio picked up the story.

By fall, when the campaign had raised about $7200 locally, Paul and Michelle found a nearly new projector for $55,000. They managed to borrow the $48,000 they needed from a local bank. By shouldering the loan themselves, they showed the public that they were committed, and this gesture boosted donations.

As a result, on 11 November, the JEM screened its first movie on the Digital Cinema Package format, Dolphin Tale. On that weekend Paul thanked Kirsten for kicking off the fundraising and gave her a lifetime pass to the JEM. For the older crowd there was Football Monday, when Paul and Michelle projected a Vikings-Packers game. They couldn’t charge admission, but they sold tickets for drawings of prizes donated by local businesses.

Even though they had the equipment, Paul and Michelle still needed to pay for it. Later in November, the Trust for a Better Harmony stepped in to help. Enabled by a generous gift from Ms. Gladys Evenrud, the Trust and a Minnesota agency for community development arranged for a flexible loan package. As a result, the JEM now needed only $28,000, to be paid from community donation. The loan sparked still more offerings to the projection bank account.

New decisions

Paul Haugerud, son Peter (in overalls), and local boys tour the JEM booth.

On 13 January of this year, Paul died.

Commander of the local American Legion, he was cremated with military honors. He left behind Michelle, his six children, his parents, four brothers, and two grandchildren. The town grieved. “There’s nothing he wouldn’t do to help someone else,” a friend said.

Michelle remembers weeks going by in a blur. Friends brought over way too much food. “I had to freeze a lot of it.” She decided she simply had to move forward. She had a full-time job and had Peter, Julia, and Sierra at home, but she would keep running the JEM.

In February, a fundraiser was held at Wheelers Bar & Grill. The event had been planned before Paul’s death, but now it gained a new urgency and poignancy. Wheelers is named for its big roller rink, where Paul had helped out often. Across the day Wheelers held a silent auction and some bean-bag and darts tournaments. Those, along with food, drink, and music, raised an astonishing $16,000. That, plus the balance in the digital account, yielded enough to pay off the bank note for the projector. There have been more fundraising events, including a pancake breakfast. Michelle will soon pay the rest of the money owed. Any funds left over will be used for upgrades. Michelle is considering 3D conversion in a year or two.

Saturday night at the movies

Things have happened so quickly that Michelle hasn’t had time to thank everyone fully on her website, but she adds in a note to me:

It is so overwhelming to think of how the entire community and beyond has come together to make this all happen. I know that even though I am now the owner/ operator of the JEM, this theatre will be here for generations to come. I have had so many thanking me for staying in business. I know this is part due to the conversion and part due to Paul’s passing. I am very grateful for Paul’s family and my friends for being there helping me through all this.

Last Saturday, The Hunger Games drew a robust crowd, mostly groups of boys, groups of girls, and families, with a few elders sprinkled in. Nearly everybody bought concessions. Many carried in buckets for popcorn. The ticket booth was decorated with Easter rabbits and a Darth Vader helmet.

Upstairs, I saw a little room off the projection booth with a porthole. It was Michelle’s and Paul’s “private screening room,” she explained. They would watch the show from an old car seat there.

On the sidewalk outside, Girl Scouts were selling cookies. In the tiny lobby, dozens of construction-paper stars were pinned up, each bearing the name of someone who donated money. Above the booth was hung a framed lobby card for It’s a Wonderful Life.

Thanks to Michelle Haugerud for all her cooperation and enthusiasm. Her informative JEM website starts here. The page devoted to the digital upgrade traces the fundraising process and records her gratitude to the community. , On the same page, scroll down to see a video of Paul running the last 35mm show. Michelle supplied the photo of Paul and Peter above. Many of my quotations come from news stories that are linked on the JEM site.

Statistics on the number of theatres and screens in the US come from the annual reports of the Motion Picture Association of America and from The NATO Encyclopedia of Exhibition. Patrick Corcoran of NATO kindly supplied me with further information.

During my time in Harmony, I couldn’t get access to much material about the JEM in the old days. According to The Film Daily Year Book, the original JEM Theatre (sometimes called the Gem) opened in the mid-1930s. It burned down in 1940. The building next door was renovated as the New JEM, which opened in September of that year. A plain-spoken house of 325 seats, it had fluorescent lighting, satin curtains, three layers of acoustic tile, and a big furnace for the cold months. Its estimated cost was $18,000. For the premiere, a four-page color brochure was printed and sent to 3000 homes in the area. The publication was “made possible thru the whole-hearted cooperation of the businessmen of Harmony who fully realize the value and convenience of this modern, good-looking theatre.” This information comes from “Harmony, Minnesota, Salutes New Jem Theatre, S. E. Minnesota’s Finest Showplace!” The Harmony News, flyer dated September 1940.

Three years later the JEM closed and became a bowling alley. It sat vacant from 1947 to 1961, when Bob and Hazel Johnson reopened it. For a fuller chronology, go to Michelle’s page on JEM history.

Michelle Haugerud and daughter Julia, 24 March 2012.

PS 1 April 2012 Marilyn Bratager writes with this correction about the source of the JEM’s name.

Relatives of mine were the original owners: Joseph Milford Rostvold and his wife, Emma. The J was for Joseph Sr. and Jr., the E for Emma and their daughter Elizabeth, and the M for the senior Joseph’s middle name, Milford, which was the name he was known by. There was a third child, Richard, but they didn’t use his initial as they didn’t want the theatre to be called JERM. 🙂

Thanks to Marilyn for the information!