Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

One summer does not a slump make

Kristin here:

Nor does an entire year. Yet at the end of 2011, the press was trumpeting the fact that the film industry was suffering a slump that might become permanent. After all, “the movies are in a slump!” makes for more catchy copy than “the movies have sunk back to normal” or “the movies are in a downturn from which they will probably recover.” The Hollywood Reporter went for a particularly dramatic approach to year-end coverage of the slump, as evidenced by the title/illustration (see above) of Pamela McClintock’s analysis, appearing in the January 13, 2012 print issue and online.

McClintock cited a number of factors. Young people are no longer going to the movie theaters. The studios are too dependent on big, familiar franchise pictures: “But exhibitors worry that moviegoers are growing impatient with Hollywood’s love affair with the familiar and shortage of original ideas (hello, Avatar!). In 2011, for the first time ever, all of the 10 top-grossing films domestically were franchise titles and spinoffs.” (But wouldn’t that mean that moviegoers are more than ever thrilled with Hollywood’s franchises?) She cites also the rise in admission costs, with ticket prices going up by 5% from 2009 to 2010.

That reason seems the most plausible. People really are tired of ticket prices that have risen faster than inflation. The industry may have pushed the cost up past a point that makes an evening at the movies seem attractive. If, as seems likely, the industry will raise the cost of 2D tickets rather than dropping the cost of 3D ones, we may see a real slump.

The 800-pound thanator in the room

Hollywood box office has its ups and downs, which is only to be expected. One year the successful releases cluster together; another year, they spread out or drop off a little. Any decline will be seized upon by many reporters as a slump, a sign that people are souring on the movies and turning to the many other forms of pop-culture entertainment available in the digital age.

Careful commentators have pointed out that naturally 2011 would be lower than 2010. As the AP’s film reporter, David Germain put it at the end of 2011, “An ‘Avatar’ hangover accounted for Hollywood’s dismal showing early this year, when revenues lagged far behind 2010 receipts that had been inflated by the huge success of James Cameron’s sci-fi sensation.”

Just how much did Avatar affect 2010’s box-office total? The film achieved a worldwide total gross of $2,782,275,172. Of that $1,786,146,809 came in during 2010. That’s comparable to, say, two Harry Potter films.

Predictably, Avatar ran for a long time. It was released on December 18, 2009 and ran for 238 days (34 weeks), closing on August 12, 2010. Naturally its most intense box-office period in 2010 would have been in the early months. Alice in Wonderland opened on March 5, on its way to crossing a billion dollars in international gross. This was a highly unusual synchronization of steamroller films. Still, in early 2011, the fact that the box office was off 20% from 2010 was immediately proclaimed as a signal of doom and gloom to come. Richard Verrier and Ben Fritz suggested that, putting aside some under-performing films, “even hits like Justin Bieber’s ‘Never Say Never,’ ‘The King’s Speech’ and ‘Battle: Los Angeles’ pale in comparison with the early 2010 blockbusters ‘Avatar’ and ‘Alice in Wonderland.’” Given that the first few months of the year are typically the dumping ground for films deemed unlikely to set the box-office on fire, early 2011 was a return to business as usual. Avatar and Alice in Wonderland hardly made for a realistic comparison.

The tentpole effect

We’ve seen that Avatar’s 2010 box office was comparable to two major blockbusters. Now consider the fact that two films released in 2010 grossed over a billion dollars each: Toy Story 3 ($1,063,171,189) and Alice in Wonderland ($1,024,299.904). (Here and throughout this entry, the amounts are given in unadjusted dollars.)

That’s the equivalent of having four very high-grossing films in one year. The only other time a similar pattern emerged was in 2002, when four of the top franchises brought forth a film: Spider-Man ($821,708,551), Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets ($878,979,634), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers ($926,047,111), and Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones ($649,398,328). It was a perfect storm that has so far not been repeated.

These are exceptional years, so one would expect the box-office to sink afterward. Yet somehow the industry and the world of entertainment journalism see years with such big box-office spikes as forming the new norms against which all other years should be judged. Studio executives seem to think that 2002 or 2010 indicate a realistic goal that they could achieve all the time, if only they could put out the right films. Almost inevitably, articles on declines in box office end with the notion that the films released in that particular year or quarter were just not appealing enough. But of course, there’s no way to deliberately achieve such a combination of blockbusters. Many blockbusters fail, and the big special-effects-laden ones take years to lumber through production. By sheer coincidence, some blockbusters converge.

The lesson to be learned here is that the really big films make so much money that just a few of them–or one James Cameron epic–can by themselves create the sense of the entire Hollywood output going way up or way down. They average out. If Hollywood attendance is dropping, it’s happening very slowly. Other factors are making up for that gradual attrition, as we’ll see below.

2002 was 2002

Journalists in particular have long been using 2002 as a benchmark to measure how badly Hollywood has been doing since. Ben Fritz and Amy Kaufman, in an otherwise good analysis written for the Los Angeles Times, resort to this comparison: “The box-office figure known in the industry as the ‘multiple’—the final box-office take compared to a movie’s opening weekend ticket sales—has dropped 25% since 2002.” The 2002 figure might have been skewed slightly by the fact that the three parts of The Lord of the Rings had an extraordinarily high incidence of repeat viewings and hence were in first run far longer than most films. For The Two Towers, the opening weekend was 18.2% of its total domestic gross (up from 15.1% for the previous part, The Fellowship of the Ring, which was in first run from mid-December, 2001 to August, 2002, half a week longer than Avatar). Spider-Man’s opening was a more typical 28.4% of the total; Attack of the Clones was 26.5%, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, 33.7%. A more recent film with above average repeat business, Inception (2010), drew only 21.5% in its opening weekend. With Iron Man 2 (2010), the opening was 41.0% of the total gross. Good word of mouth is another possible explanation for some films’ steady or even growing performances after their opening weekends. By the way, the fact that Fellowship of the Ring was in theaters for seven months in 2002 boosted the total box-office beyond the rise created by the four franchise films that premiered within that calendar year.

It’s not clear that the growth in the proportion of the box-office take represented by the opening weekend is directly related to the drop in attendance, as Fritz and Kaufman suggest. One might instead point to the growth in the number of screens, with new megaplexes opening and existing ones adding screens. In 2002 there were 35,500 US screens, but by 2011 there were over 39,300–an increase of nearly four thousand screens. They provide more exposure to the title on opening weekend.

Further evidence is the expansion of opening weekend releases. It was unheard of in the early 2000s to have even a major blockbuster open on 4000 screens. Now it’s not uncommon. At its widest release, The Two Towers was in 3622 theatres, while Iron Man 2 was in 4390. With that many theaters, the number of people able to get tickets for the opening weekend grows, which means that, unless a film generates significant repeat attendance or excellent word of mouth, the box-office take will fall off more rapidly than it used to. But the fall-off doesn’t necessarily mean that fewer people have bought tickets.

Oops! Never mind

The story of the slump suddenly began to look very different as soon as the new year began. At the end of February 2012, Variety reported that domestic box office for the first two months was up 21% over the same months of 2011. It so happens that in the same period of 2011, box office was down 20% against the early months of 2010. And the early months of 2010 saw Avatar going very strongly after its mid-December debut.

The Variety article’s author, Andrew Stewart, pointed out the fact that Avatar had unbalanced the 2010 results. He also pointed out that the fast start out of the 2012 box-office gate resulted from a larger number of films making less on average. But this year’s likeliest high-grossers are yet to come: The Hunger Games, The Dark Knight Rises, and the first part of The Hobbit, with The Bourne Legacy and The Amazing Spider-Man possible mega-hits as well. There are also new films in the Madagascar, Ice Age, and Men in Black franchises coming out. Ann Thompson weighed in a few days after Stewart, pointing out that the increased number of films was not necessarily a problem, since more theaters are being built at a fast clip around the world. More theaters theoretically need more product. (More on that below.)

But an important point about the early hits of 2012 is that they were relatively modest films. They could have been expected to earn far less than blockbusters but still perform well in relation to their production and distribution costs. The Vow, the first film of the year to cross $100 million, is a romance; Safe House a Denzel Washington thriller; and Journey 2: The Mysterious Island a mid-budget family adventure film. This is pretty much what a normal, non-Avatar year looks like early on. (In 2008, David wrote about one early-in-the-year release that was a modest hit, Cloverfield.)

Soon thereafter Chronicle, made on an announced $12 million budget, had pulled in about ten times that internationally and proven that young men, contrary to industry fears, were still willing to go to see movies in theaters. Then The Lorax became the first iron-clad blockbuster. Neither of these is part of a franchise. Talk of a 2011 slump has disappeared. I suspect it may resurface a year from now as a benchmark showing how extraordinarily well Hollywood films did at the box office in 2012.

The 3D effect

2009 and 2010 were the best years for 3D, with Avatar not only dominating world film screens but also luring producers to imitate its success. But in 2011, the advantage provided by the higher ticket prices that 3D permitted began to fade. Last summer I discussed the decline at some length, here and here. I won’t rehash that here. In 2009, 3D films made on average 71% of their box-office grosses from 3D screens, and in 2010 the figure was 67%. In 2011, 56% of business for 3D films came from 3D screens.

The decline may represent the end of the novelty appeal of 3D, as well as the increasing number of 3D films competing in the market. Anecdotal evidence suggests that moviegoers are tired of paying premium prices. The fact that 3D animated features took in a slim one-third of their grosses from 3D screens in 2011 suggests that the cost of a whole family attending together, especially if the younger children can’t keep the glasses on, has begun to hamper the format.

Thus 3D may have contributed to an artificial, temporary rise in total box-office figures in 2010. This would inevitably be reflected as a decline in 2011, as more people opted for 2D screenings of popular films.

(Figures from Screen Digest, February, 2012, p. 37.)

It’s a big, wide, ticket-buying world out there

All the box-office reports and prognostications discussed above are based on domestic box-office grosses, which in practice means the USA and Canada. But in parallel to the reports of a slump in 2011 BO figures, there were reports of impressive growth in foreign film markets.

Take the United Kingdom, traditionally a top consumer of Hollywood films. 2011 saw the total box-office gross surpass £1.5 billion for the third straight year. That total grew by 5% over 2010. Films from Hollywood’s Big Six studios took 74% of the market. Local productions had a particularly good year, with three in the top ten: The King’s Speech, The Inbetweeners Movie, and Arthur Christmas. Even if that success continues, however, Hollywood will have a healthy share of the market.

More generally, Variety announced in mid-January, “It was business as usual at the 2011 international box office. And business is booming.” (“International” refers to all markets apart from the USA and Canada.) The Russian market is growing quickly, with its total gross of $1.16 billion in 2011 representing a rise of 20% from 2010. Russian films make up only 14.7% of the market, with the rest mostly coming from Hollywood.

The Chinese market is huge, passing $2 billion for the first time in 2011, up 29% over the previous year. (See below.) There is a Chinese quota of 20 foreign films per year, but a recent decision to allow more 3D and Imax films in may herald a gradual opening of the market. Certainly the blockbusters that make their way into China are popular. According to Hollywood Reporter, for the first time, China was Paramount’s highest grossing foreign territory, with $303 million at the box office, largely thanks to Transformers: Dark of the Moon. Still, China yields only about 15 cents on the dollar back to the distributor, a situation likely to change only slowly.

Brazil, India, and Eastern Europe have seen healthy expansion as well.

Even Hollywood comedies, notoriously hard to sell abroad, are becoming more popular. In 2011, Bad Teacher, Just Go With It, and Friends With Benefits all made around $100 million outside North America. Very unusually for comedies, they also grossed more money abroad than domestically.

The major studios’ box-office grosses abroad were: Paramount, $3.19 billion; Warner Bros., $2.86 billion; Disney, $2.2 billion; Fox, $2.15 billion; Sony, $1.83 billion; and Universal, $1.3. (These figures represent the total amount paid for tickets; only a portion returns to the studio.) I take this information from Hollywood Reporter, which notes that the big studios are increasingly buying local, foreign-language films to distribute within those domestic or regional markets.

There’s more to Hollywood than tickets

One might conclude from all the stories about the box-office slump of 2011 that the big studios’ profits would be down, at least a little. Actually, a studio had to work hard not to see profits rise last year. That’s partly because they make things other than movies and partly because movies make a lot of money that has no direct connection with theatrical distribution.

The February 24, 2012 issue of The Hollywood Reporter published a helpful summary, “2011 Profitability: Studio vs. Studio.” (The online version is behind a paywall.) As the authors point out, the studios calculated their profitability on different criteria, so direct comparisons among them are difficult. Nevertheless, the article shows that most studios were profitable and suggests why.

Time Warner’s filmed entertainment wing had a 15% rise in profits from 2010 to 2011. That resulted in part from the release of the final Harry Potter film. Beyond that, however, there was the fact that WB now manufactures video games and shipped 6 million copies of Batman: Arkham City. (That game wouldn’t exist without the film series, so we see synergy at work here.) It also produces over 30 TV programs, including The Big Bang Theory and Two and a Half Men.

News Corps.’s film studio, Twentieth Century Fox, saw profits rise 9%. Rise of the Planet of the Apes boosted the bottom line, but so did strong home-entertainment sales. The TV wing produced Glee and Modern Family. “Films licensed to pay TV and free TV helped, as did digital content-licensing deals. The TV licenses are estimated to have been worth about $200 million in the second half of the year.” Thus quite apart from their box-office takings, films made a lot of money for the studio.

The profit from Sony’s film unit jumped an impressive 95%. $278 million of that was a one-time sale of merchandising rights for the new Spider-Man movie. The Smurfs was the studio’s top earner at the box-office, and according to The Hollywood Reporter, “The division also benefited from stronger-than-expected DVD sales of The Green Hornet and Battle: Los Angeles.”

Disney was the only studio to face a decline in profitability. Its profits slipped 20.5%, though they were hardly meager at $656 million. The disappointments of Mars Needs Moms and Cars 2 are largely to blame. Disney’s current attempt to create a new blockbuster franchise in John Carter clearly won’t reverse the trend.

Paramount’s profits were the lowest but improved the most in 2011: 128%. The growth seems due largely to the Transformers franchise and high income from a 2010 deal between Epix (Paramount’s 51%-owned VOD channel) and Netflix.

The Hollywood Reporter was unable to obtain figures for Universal.

This overview hints at the underlying factors that make assessing the health of the film industry through box-office figures alone a shaky process. Ideally we would have figures on DVD and Blu-ray sales, as well as on licensing deals for streaming and other digital distribution systems. But this information isn’t made public by the studios.

The uncertainties and appeal of post-theatrical markets

This is a pity, since the real crisis facing the film industry today is not fluctuations in box-office income. It’s how to deal with the rapidly changing post-theatrical revenue stream: the sudden proliferation of other ways to sell or rent films for viewing on the tablets, game consoles, cell phones, computers, and other devices now driving the death of tape- or disc-based home entertainment. Studios see new ways to make money and are at war with exhibitors about how short a window there would be between theatrical release and the various forms of video release.

Early in this proliferation of online-based distribution, studios continued to concentrate on selling DVDs and later Blu-rays. They licensed the rights to rent films on DVD or via streaming to Netflix and other companies. Now they’re beginning to realize that they don’t need the middleman, but they haven’t found models for handling all forms of post-theatrical distribution themselves. In the meantime, Redbox kiosks rent DVDs for a pittance and make the home-video experience seem like something that barely needs to be paid for–and certainly isn’t an Event.

The decisions the studios make about post-theatrical are crucial to the health of the film industry. Movie City News publisher David Poland recently summed up the situation, pointing out that the theatrical release is still far and away the biggest single generator of income per viewer for the industry. His essay is worth reading in full, but here is the gist in terms of how home-entertainment revenues relate to theatrical income:

1. Post-theatrical is already a blur for consumers and it will only get more so. People will expect access at all times on any device for a low, low price… either in a subscription model or a per-use price point of $2 or less.

2. Theatrical will soon be the ONLY revenue opportunity that stands apart from that post-theatrical blur. No other revenue stream will ever again generate as much as $10 a person… or even $5.50 per person.

3. Consumers adjust to whatever window you offer. But history tells us, the shorter the theatrical-to-post-theatrical window for wide-release movies, the more cannibalism of the theatrical.

4. Just as the DVD bubble could not be pumped back up after it was deflated by pricing aggression, theatrical will not survive a significantly shorter window to post-theatrical as we now know it… and once it is broken, it will not be able to be fixed. And that revenue stream will NOT be replaced by what is now post-theatrical. It is simply money that will be lost, never to be recovered.

Theatrical will never be The Drink again. You’re looking at a 2 month window for most studio films vs decades of post-theatrical revenue opportunities. It’s not an even fight. But take a deep breath and look at the obvious… for theatrical to still be as much as 40% of the revenue of a studio film is bloody amazing. It’s not the past. It’s not ’39 or ’69 or even ’89. But it’s a LOT of money. And it is insane to take it for granted or to dismiss it, because there is no proof out there that I have ever heard that suggests that theatrical revenues gets in the way of post-theatrical revenues… only the other way around. Why? Because theatrical is the unique proposition. It’s post-theatrical that really has to compete with EVERYTHING the world has to offer.

(David’s post came in response to one by Mike Fleming on Deadline.)

If the studios start selling their films in various digital forms for a dollar or two, and do so in ways that cannibalize the theatrical market, there will come a point where many people stop going to theaters and stay home to do their movie viewing. So there will need to be many more purchasers of that film than there currently are to make up the difference between that cheap sale and the price of a movie ticket. Without a boost in consumers, post-theatrical income would fall, and the studios wouldn’t be able to afford to make the sorts of films that currently generate the most money.

Whether David’s analysis is too pessimistic remains to be seen. But he points to a far bigger problem than a largely illusory drop in box-office figures.

Jumping to conclusions

The notion that 2011 saw a serious slump results from comparisons that make for catchy headlines. But sometimes a situation can prove misleading. Consider the title of a Variety article from February 23 of this year: “Imax profit plunges to $6.3 million.” Can this be the end of Imax? Yet read on:

Imax profit fell last quarter to $6.3 million from $54 million, mostly on a major tax benefit the year before. Revenue eased by $2 million to $67 million.

Without the tax and other items, income fell to $9 million from $14 million, in line with expectations given a soft box office.

The company said 2011 was a year of record signings and installations, with 497 Imax theaters installed in commercial multiplexes, up 33%, led by China, Russia and North America. CEO Rich Gelfond said the company will add focus on South America, including four new theaters in Brazil, Western Europe and India, where a recent deal will bring Bollywood titles to Imax. It will expand local film production from China into Russia and France.

(Note: The title of this story was subsequently changed to “Imax, Dish, Liberty stocks rise” when it was revised to add the fact that Imax’s stock rose 4.5% on the above news.)

The moral is, the obvious interpretation is not always the correct one. The implication of box-office fluctuations needs analysis beyond a simple comparison of ups and downs from one year to the next.

Moviegoers at the Super Cinema World in the Metro City shopping mall, Shanghai, China

Pandora’s digital box: Notes on NOCs

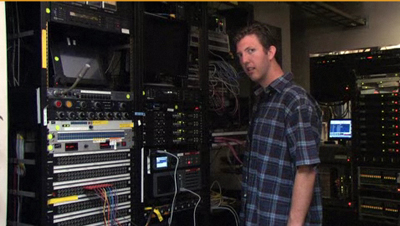

A video-wall display in the Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

DB here:

You’re in a multiplex. The pre-show attractions are large, loud promotions for TV shows, pop music, and star careers, interspersed with ads for men’s cologne and local pet-grooming facilities. Then comes the theatre chain itself telling you to hush up, turn off anything that emits light or sound, take your feet off the seats in front of you, and buy some popcorn. Next comes a barrage of trailers. Sooner or later the movie starts.

If you look back at the projection booth, will you see another human being? Not necessarily. It’s possible that everything that happens in your theatre is automated.

Now imagine another space, a large room with ranks of work stations. A couple of dozen people sit before their monitors, facing a video wall. From a room like this in Omaha, Nebraska, or in Cypress, California, or in Liège, Belgium, or in Shenzhen, China, these workers can remotely track thousands of theatre screens, including yours. It’s another consequence of the emergence of digital projection in our movie theatres.

Command and control

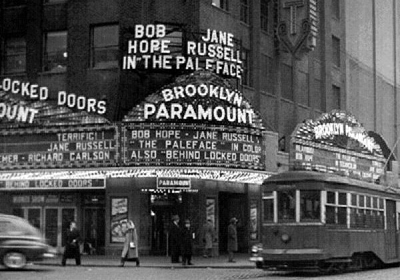

Brooklyn Paramount Theatre, 1948, from the splendor that is Cinema Treasures.

One of the many lessons you learn from Douglas Gomery’s magisterial history of the Hollywood studio system is straightforward. For about a hundred years, film producers and distributors have sought to control exhibition.

The advantages are obvious. Controlling exhibition keeps competitors off screens, it yields more or less assured revenues, and it allows vast economies of scale. If you can count on 2000-4000 screens playing your movie, as is common for Hollywood releases today, you can budget your production accordingly.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, studio control was quite direct. The Big Five companies (Paramount, Loew’s/MGM, 20th Century-Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO) wholly or partially owned hundreds of theatres, and these served as display cases for their product. Because no studio could supply all its theatre chains with films, studios shared their screens with their peers and kept other companies’ films out. “Here,” Gomery writes, “was a collusive oligopoly (control by a few) that operated as an almost pure monopoly.”

The studios didn’t own most of America’s theatres, just the most profitable ones. The thousands of independent houses and chains were subjected to studio control in more indirect ways. The studios forced the independents to book films in batches (“blocks”). To get prime releases, the exhibitors had to take weaker titles. Likewise, the independents had to bid for upcoming releases without being able to see them.

The structure of the market was another strategy of control. Adolph Zukor pioneered the system of runs, zones, and clearances. If people wanted to see a new release immediately, they had to pay top dollar at a first-run theatre. After a certain interval, the clearance, the movie would play a second run theatre in another territory at a lower price, and so on down the food chain of movie houses.

Technology was another strategy of control. The 35mm film standard wasn’t proprietary, but the sound systems that the studios adopted in the late 1920s were. Of the dozens of systems, only two became standardized: Western Electric and RCA. In a process similar to what’s happening today, theatres were forced to install one system or the other. The thousands of screens that couldn’t afford the new technology went dark.

This system worked to the Big Five’s benefit until 1948, when the Supreme Court declared Hollywood’s vertical integration monopolistic. The studios chose the wisest way to break up, given the slump in admissions: They divested themselves of their theatres and concentrated on production and distribution. (The process took several years in some cases, and there often remained close unofficial ties between the Majors and their former circuits.) In addition, block-booking and blind bidding were outlawed, so some market factors became more favorable to exhibitors.

The postwar studios occasionally tried to remake exhibition through new technology. CinemaScope, designed by 20th Century-Fox, sought to become the industry standard for widescreen presentation. Although there was considerable take-up, it had competition from other systems (notably Paramount’s VistaVision) and exhibitors were able to wring concessions from Fox. Centrally, exhibitors were reluctant to install magnetic stereo playback, and so Fox had to compromise by producing prints that could play on optical sound systems as well. Similarly, while various 70mm formats were tried, none became obligatory for exhibitors, since films released in 70 were also released in 35, if only in later runs.

Of course Hollywood still had a desirable product and could charge dearly for it, so stiff contracts for revenue returns gave studios considerable power. In the 1970s, the Majors (which no longer included RKO and had expanded to include Disney, Columbia, and Universal) found another way to use market dynamics to control exhibition. To publicize Jaws (1975), Universal launched massive television advertising and avoided the “platforming” or “exclusive engagement” practice. Studio chief Lew Wasserman opted for “saturation booking,” releasing Jaws on over 400 screens simultaneously. A month later it expanded to over 600.

The growth of the blockbuster, nurtured by Star Wars, Superman, and other huge hits, encouraged theatre chains to build multiplexes. The distributors could then blanket screens with their product. Exhibitors could realize economies of scale by holding over some movies for months while rotating regular releases through other screens.

With the arrival of cable, satellite transmission, and home video, studios were able to maintain tiers of price discrimination. The theatrical opening became the loss-leader, making less revenues but establishing buzz for the ancillary market. Theatrical runs were shortened considerably, but the “windows” of video distribution became the equivalent of second- and later runs. A movie becomes available on Pay Per View, then VOD and/or DVD, then premium cable, and so on. The windows’ length and ordering have changed over the years, but throughout, by carving up the market by price discrimination the studios continued to rule exhibition patterns.

My account makes recent history too neat, with studios apparently steamrollering unprotesting exhibitors. In fact, exhibitors have responded to some pressures by dragging their feet or pushing back. Better sound systems took some years to penetrate the market. Some big theatres refused to play Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace because of onerous terms, including a minimum guarantee and a commitment to a lengthy run in a ‘plex’s biggest auditorium. More recently, studios’ efforts to shorten windows and release films sooner on DVD or on VOD have sparked resistance.

Studios have periodically tried to become vertically integrated again. There were some attempts in the 1980s to run theatre circuits, but only Viacom has found success owning both Paramount and the National Amusements chain. Today, technology is providing a more effective lever–or rather a crowbar. Digital projection furnishes the most thoroughgoing opportunity for studio control over exhibition since the coming of sound, and perhaps since the days when the Majors owned movie houses.

NOC, NOC, who’s there?

Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

My first entry in this series considered the power of setting standards, something Hollywood has been good at for decades. In 2005 the Majors established the technical specifications for the Digital Cinema Initiatives. As has happened throughout history, they had the input from the powerful manufacturers, service companies, and professional associations, like the SMPTE and the American Society of Cinematographers.

Once the standards were set, the projection and service suppliers could move forward with appropriate equipment. The conversion is expensive, so exhibitors have been offered the option of signing up for a Virtual Print Fee. This is a partial subsidy from the major companies that is passed through an “integrator,” a third-party company that attends to acquiring the equipment, installing it, and monitoring payback.

A decade ago, over a dozen significant US theatre chains filed for bankruptcy protection, so costs are constantly on exhibitors’ minds. Digital projection offered multiplex operators the opportunity to cut staff. Screening film prints is somewhat technical, and it relies on mechanical skills that are growing rare. So anything the manager can do to simplify running the show is welcome. Movies on digital files filled the bill. A film projectionist, represented by what was once one of the more powerful unions around, is expensive. Teenage labor is not.

Digital works for the fresh-faced novice. Once the film comes in on a hard drive, it’s not terribly hard to set up a show. Disney has made a couple of remarkable instructional films (here and here) for the new projector operator Jimmy, who wears the requisite Bob & Ted apparel.

In the old days, Walt would have given us a cartoon, and Goofy would have been the star.

Jimmy loads the movies, and he or the manager sets up the programs. Once the features, the trailers, and the ads are on the servers or the library system, the theatre manager can program every screen. From a computer in the manager’s office, or almost anywhere, he or she can build each auditorium’s playlist by dragging and dropping. If the arrangements with the distributor permit, the files can be migrated from screen to screen.

Even under these conditions, though, you need minimal maintenance. Projector lamps must be changed, for instance. The installers or a local expert can supply routine maintenance, but sometimes there are problems. An encrypted file can’t be opened, or it’s corrupted, or the show mysteriously stops. Very likely Jimmy, even consulting his manual, can’t fix the problem.

Enter the NOC.

Network Operations Centers, also known as Data Centers, are part of broader Information Technology management. They’re used whenever a business or government agency has a network that needs 24/7 monitoring. All Fortune 1000 companies have NOCs, and probably have mirror backups of them scattered around the world. NOCs coordinate railway systems, military systems, banking, and police and fire departments. Amazon has a NOC in Seattle, Wal-Mart has one in Bentonville, Arkansas, and AT&T has a monstrous one in Bedminster, New Jersey (below).

There’s a nice gallery of NOCs here.

Don’t confuse NOCs with call centers or help lines. NOCs are handling and storing vast streams of data from computers, cameras, and other inputs. The goal is keeping track of things pertinent to the business or agency. But of course even large staffs can’t do this simply by eyeballing the flood of data. Instead, the software is set to notice anomalies and to call them to the attention of the humans. So if a police camera outside a Tube stop in London picks up a pattern of unusual activity, say three men running purposefully toward a woman, that information is pulled out of the stream and sent to an operator for inspection.

Once film theatres became digital, they acquired the ability to connect to NOCs via the Web. An owner who funded the purchase of the DCI-compliant equipment might well choose to pay a NOC to provide oversight and help. Exhibitors who sign up for a Virtual Print Fee program are required to sign up for a NOC. NOC services may be supplied by the equipment manufacturer (Sony, Christie’s, Barco, GDC et al.) or by the installer, such as Ballantyne Strong (Omaha) or Film-Tech Cinema Systems (Plano, Texas). An integrator may also offer NOC services, as Cinedigm does in the US and XDC does in Europe.

By the standards of giants like AT&T, a theatre-monitoring NOC tends to be fairly small, as my pictures indicate. Still, the purpose is the same. Each projector/ server combination and theatre-management system (essentially a master server) is connected via the internet to the NOC. The NOC monitors the state of the system, so that, for instance, it can keep track of lamp life, parts conditions, net connectivity, and the like. The software can send alerts to the theatre management for upcoming maintenance and can do troubleshooting. It’s also trained to notice problems—glitches in playback, lights going on, dropped subtitles, or whatever. Anomalies are called to the attention of the specialists at the work stations.

The projector manufacturer Christie’s initiated one of the first NOCs in 2003, and it now monitors over 3700 digital screens across the US and Canada. From its California facility it “manages the configuration of systems, provides help-desk services to customer staff, and access to local technicians with local parts to provide on-site repair and support.” The Shenzhen center maintained by GDC, a server company, monitors ten thousand screens. Most NOCs don’t plan programming or chase down encryption keys from distributors, but the NOC maintained by Film-Tech will perform these services as well. It will even power up and down the auditorium. With the Film-Tech system in place, says the company’s brochure, “The projection booth can literally operate for months without anyone ever entering it.”

The show must go on, if remotely

The projection area of the Studio Movie Grill City Centre, Houston, announced as the world’s first completely automated booth.

Now Jimmy and his manager have substantial support, but in turn they’ve shared a lot of information with the NOC. In order to collect the Virtual Print Fee, the exhibitor must play the studio’s film on a contractual basis—for a certain period, a certain number of times per day, and so on.

In earlier times, a dodgy exhibitor might run a film more frequently than was reported back to the distributor, with the exhibitor pocketing the difference. Or an exhibitor might trim shows of a poorly performing title, substituting something more popular and depriving the weak film of playing slots and box-office payback. In the pre-digital days, distributors sent out “checkers,” staff disguised as ordinary moviegoers, to see that theatres were running films according to the booking.

Now the projector/server mating provides real-time screening information to the NOC, and that flows to the distributor. Says an executive at a firm supplying NOC services:

All of the NOCs notify the studios about the performance of the systems. Uptime is critical or VPFs will not be paid. Exhibitors cannot miss more than a certain number of allotted shows and still receive their checks. . . . All NOCs provide the studios with access to the playback logs to ensure the movies booked are actually played.

According to the same source, some NOC systems monitor the use of the equipment outside normal shows. “Some of the traditional NOCs go so far as to ensure the equipment is not used for anything else, and the theatre will be back-charged for the use of that equipment.”

At a minimum, then, the performance information forces the exhibitor to abide by the booking contract. But it also means that even with full knowledge on the part of both exhibitor and distributor, the advantage lies with the distributor.

For example, if an exhibitor wants to play a film from outside the Majors, even if that film is available on a DCI-compliant file, that distributor has to pay a VPF. From the standpoint of the studios and the supply companies, he who pays the piper calls the tune: A DCI-compliant projector shouldn’t be used by free riders who didn’t participate in the DCI. Why should the Big Six establish the standard and fund the purchase and installation of the gear in order to play a competitor’s film? If the exhibitor dares to proceed without the VPF and uses the equipment to show unauthorized product, that information flows back to the NOC.

Consider as well the practice of “splitting.” Smaller theatres and art houses often adopt the multiplex tactic of offering many titles, but for them that entails showing two or more films on the same screen in a given day. Often splitting is done with the advance permission of the distributor, but sometimes it’s done ad hoc and reported after the fact (unlike the dodgy practice of show-shuffling I mentioned above). But VPF conditions may forbid splitting altogether. And if the exhibitor is obliged to do it, as when one movie file fails to run and another must replace it, the NOC will flag it.

Distributors allow a certain leeway for quality checks, running a film at odd hours to make sure it plays properly. Still, the NOC is tuned to those anomalies too. One exhibitor remarks, “If I’m demoing a movie, they may not know it’s a demo. They might wonder why I played a movie at 9:30 AM.”

In a highly automated environment, things can proceed blindly. There’s a story (not apocryphal, I think) about an early automated theatre system here in Madison, Wisconsin. During the 1970s, a snowstorm paralyzed the town, but someone at a theatre had left the system on. Even though the theatre was closed (and no one could get to it), the show went on: lights up, lights down, curtain parts, film runs, film halts, lights up, film rewinds….

More vaguely, some exhibitors worry about the NOC as a policing or surveillance operation. No one can object to a mechanism that enforces contracts, but film screenings have long had a certain fluidity, especially in the art-house realm. On-the-fly compromises and flexible arrangements emerged from negotiations among managers, programmers, bookers, and distribution staff. People knew one another and made allowances for specific circumstances. When so much of scheduling and operation is transferred to servers, playlists, and NOCs, human contact is likely to wane. The projectionist isn’t the only ghost haunting the multiplex.

Anyone who has ordered something with a credit card online has already submitted to the oversight of a NOC. But when your livelihood depends on smoothly functioning film screenings, you could be understandably apprehensive about turning your business over to unknown others in unknown places. Hacking, malware, and human error are spectres hovering over all of IT. As one theatre owner told me: “[The NOC] could shut off every theatre at one time and in the process send a little message, like the Jolly Roger in Independence Day when the guys bugged the mother ship.”

The studios innovated technology and had the power to set standards and restructure the flow of product. The multiplex exhibitors wanted to cut costs and simplify presentation. This meshing of interests allowed Hollywood studios to control exhibition to a new degree. Who wants to own theatres anyway? They entangle you in mortgages and real estate crises, and they have the awkward habit of going into bankruptcy. In addition, the Majors could win over local exhibitors by upcharging for 3D and by supplying ad packages that generate more income. Today if you control the files, the encryption, and the network, you control the show.

What’s left for the managers? Well, there’s selling popcorn.

This is the seventh in a series of entries on the conversion to digital projection in cinemas.

Thanks to Douglas Gomery, whose work on the American film industry has guided my thinking for the years going back to our teaching together at Madison in 1973. The place to start is his superb book The Hollywood Studio System: A History, which is complemented by his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States. I’m grateful as well to those exhibitors and service specialists willing to share information with me, as well as to Jenn Jennings, who is making a film about the digital transition, and Jim Cortada of IBM and the Irvington Way Institute.

The Film-Tech Forum is an informative chatroom concerning projection and general film matters. Examples of NOCs in action have been provided in videos by Christie and XDC. In the latter, and true to European sophistication, our fashion-challenged Jimmy is replaced by a woman with bangs and a discreet nose ring. Yet like you and me, she likes a snack.

As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?

Something to do with 2D to 3D conversion for Conan the Barbarian. (See 3DLiveFlix)

Kristin here:

Just over a month ago I posted “Do not forget to return your 3D glasses,” an entry suggesting that on average theatres were making less money from 3D versions of films than 2D versions. I made two basic points. First, claims that films were making, say, 60% or 45% of their box-office gross from 3D showings were inaccurate. Only the extra fee charged at 3D screenings was for 3D; the rest was for the film as such. By that logic, something closer to around 10% was actually being earned by 3D (assuming people who went to see a film in 3D would probably see it in 2D if necessary.)

Second, my point was that if a film’s box-office percentage from 3D screenings was lower than the percentage of theaters in which it was being shown in 3D, then the exhibitors in those theaters were making less money than exhibitors showing the film in 2D. For most films that have come out this summer, starting in May, the percentage has been distinctly lower.

Wasn’t this supposed to be the summer of 3D?

With the summer movie season drawing to a close, I thought I would summarize some recent developments. These tend to suggest that the decline in the popularity of 3D in the U.S. market has continued. Indeed, a recognition of that decline has started to have an impact on the effort within the industry to pressure theaters into showing films in 3D.

During August I noticed for the first time that trade-paper and online sources are becoming more explicit about saying that 3D is no longer as big a draw as it used to be. Reporting on August 13, the day after the release of Final Destination 5, Variety stated, “Though roughly 89% of its screens are in 3D, and 217 are in Imax, ‘Destination’ isn’t expected to see much of a boost from the format given waning interest in 3D. Optimistic B.O. pundits have the film topping out at $21 million through Sunday.”

In fact, Final Destination 5 grossed over $24 million. That was, however, the lowest opening-weekend gross of the franchise. It made about 75% of its gross from 3D screenings, which occupied 80% of locations. That’s better than most 3D films of the summer in proportion of income to screens, but still not great. Its comparatively good performance in 3D suggests that genres like horror still tend to draw the spectators most interested in 3D. Final Destination 5 came in third after two non-3D films, Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Help, both of which did much better than expected.

The weekend’s other 3D film, Glee the 3D Concert Movie, did so badly that the trades didn’t bother to report its percentages of 3D screens in proportion to income. Its box-office gross put it at #11 on the chart, earning less than $3000 per screen.

The following weekend, August 19-21, saw Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Help switch slots on the chart, with The Help becoming the first film since January to rise from a #2 opening to the #1 rank—a position it held this past weekend as well, experiencing a low 28% drop despite East Coast theatre closings due to the hurricane.

That same weekend saw three 3D films do lackluster business. Of those, Spy Kids: All the Time in the World did the best, coming in at number 3. About 44% of its income came from 3D, which fits into the 45% level typical of 3D films this summer. Interestingly, though, only 41% of the locations where the film was shown had it in 3D. Variety’s report on Saturday remarked, “The summer’s new norm is to make about 45% of grosses off 3D screens, though that figure could be even lower this weekend with so many pics vying for 3D play and so many of ‘Spy Kids’ engagements opting for 2D.”

There are two implications here. First, if fewer theaters show a film in 3D, the ones that do will make more money, since those moviegoers interested in seeing a film in 3D will converge on that smaller number of theaters. There apparently are not enough such moviegoers to justify having 60% or more of theaters showing 3D. Second, given that four 3D films were debuting that same weekend, theater owners opted to show the film aimed at young children in 2D. We know that there have been complaints that children don’t like wearing the glasses and that parents don’t like shelling out extra fees to take a whole family to a 3D screening. The strategy worked, which again suggests that genres aimed at teenagers might provide the home for 3D, if it survives long-term.

Don’t worry, that includes the whole family. (Just kidding! It’s actually a ticket to last year’s “OnHollywood” trade summit, where 3D was discussed.)

But the teenage-targeting assumption didn’t work out well for the two other 3D debuts of that weekend. Conan the Barbarian showed in 3D in 71% of its locations, but only 61% of its gross came from those locations. The figures were almost identical for Fright Night. Perhaps the two films split the teenage audience, to the detriment of both. Glee fell off 69.4% in its second weekend, to an average of less than $1000 per screen.

The weekend of August 19-21 saw six 3D films in the top 11. (I list 11 rather than 10 because the 11th was the summer’s most successful film and a 3D item, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2.) The 11 were, in order (3D films in bold): The Help; The Rise of the Planet of the Apes; Spy Kids: All the Time in the World; Conan the Barbarian; The Smurfs; Fright Night; Final Destination 5; 30 Minutes or Less; One Day; Crazy, Stupid, Love; and Harry Potter. Of those six films, only two, Harry Potter and The Smurfs, made it to number one—for only one week each, remarkably.

Still doing well abroad

The big Hollywood studios continue to defend 3D as a financial strategy, since films made with the process continue to clean up in most foreign territories. Even though the percentage of 3D box-office income has fallen to a fairly consistent 45% (apart from the occasional genre film), it still provides about 60-70% of the international gross. (Unfortunately percentages of theaters showing 3D films aren’t given in such reports.)

Variety’s Andrew Stewart helps explain how some foreign markets encourage 3D viewing:

To some degree, the divergence can be chalked up to a matter of preference — some cultures just like 3D more than others for reasons that can’t be quantified, and big-budget f/x spectacles continue to draw big auds overseas — but there are also some subtle differences in local pricing models that provide insight to studios and exhibitors eager to see 3D pay off on its promise of enhanced B.O. takings.

Some notable factors: Many international markets temper 3D upcharges with discount play periods. China has half-price Tuesdays. In Germany, “Cinema Day” brings a steep midweek price drop to matinees. And some territories even charge less for 3D pics that have shorter running times. In many countries, premium ticket prices for 3D are further mitigated because moviegoers are encouraged to buy their own reusable glasses.

[…]

Some Japanese exhibs ease 3D ticket prices by charging less to those who bring their own glasses. Dolby controls most of the Japanese 3D market, and in March, the company started offering reusable 3D glasses for $12 per pair. In Europe, RealD sells its reusable glasses at concession stands or the ticket window for about E1, saving auds the repeated expense.

But if theaters attract customers by giving discounts or waiving fees for those who bring their own glasses, how long can the high proportionate income from 3D hold up? Sales of glasses benefit the technology companies, not the theater or studios, and eventually the market will be largely saturated.

So far 3D is holding up well in most foreign markets, but there is one exception. In Spain, where the 3D premium averages a whopping 37%, Transformers earned 49% of its national gross from 3D, Pirates of the Caribbean 41%, and The Smurfs 39%. Variety blames the sag on 22% unemployment and “rampant piracy.” But unemployment and piracy aren’t unique to Spain by any means.

And foreign markets got into 3D exhibition a bit later than North America did. There’s nothing to say that ticket premiums and the decline in the novelty value of 3D won’t start affecting international exhibition eventually.

A certain lack of confidence

The August 12 edition of The Hollywood Reporter revealed that RealD’s “stock has plunged 60 percent since reaching a 52-week high in June as U.S. audiences seem to tire of the format.” Now that’s serious. Two weeks later, in the August 26 edition, a smiling Michael Lewis, the firm’s CEO (below), was given a two-page spread with an interview where he explained why he thought Wall Street was overreacting. (These references are to the print edition; online they’re behind a pay wall.)

Clearly, it was an overreaction. We had record earnings. We’re a relatively new company, and as time goes on we’ll prove the model. It doesn’t really matter if a film does 40 percent or 50 percent; we just believe this is a transformative event like the Internet and the personal computer. All visual displays are going to get better, and we’re really well positioned. Over time, Wall Street will figure that out.

That’s a remarkable claim. Many of us might say, “I don’t know how I got along before computers” or “before the Internet.” How many people would really say “I can’t imagine what we did before 3D came along”? This is hardly a transformative event on a scale even vaguely close to those two technologies. I can easily get along without seeing a film in 3D, but I would never go back to an era when endnotes didn’t rearrange themselves automatically  when you moved or added a reference in your text. Think, too, how profoundly computers and Internet have affected the world financially, and then compare that with the impact of 3D.

when you moved or added a reference in your text. Think, too, how profoundly computers and Internet have affected the world financially, and then compare that with the impact of 3D.

Lewis also seems disingenuous when he claims that whether a film does 40% or 50% of its business in 3D “doesn’t really matter.” It certainly matters to the local multiplex owner who sees more people going into an auditorium showing a movie in 2D than another auditorium showing it in 3D. It matters to the distributor who gets a cut of the take and to the studio that gets the remainder–and had to pay extra to begin with to make the film in 3D.

He may be right, though, that Wall Street overreacted. The interview includes some impressive figures. RealD controls roughly 85% market share of the domestic 3D box office. (Apart from selling its projection systems, special screens, and glasses to theaters, RealD gets a licensing fee averaging fifty cents for every ticket sold.) Within the U.S., it has 10,300 screens in 2,500 locations; abroad, the number is 7,200 screens in 2,300 locations. The firm’s 2011 fiscal-year revenue was $246.1 million, up 64% from the previous year. Its fiscal-year 2011 gross profit was $67.7 million, up 633%. This is flashy–though such growth came during the post-Avatar era when theaters which had missed out on the film’s bonanza were buying 3D equipment at a good clip, and more 3D films were in the pipeline. (Lewis says 2011 will see forty 3D films released.) If theater conversion is nearing saturation point and 2D screenings are outdrawing 3D ones, though, this summer may mark the end of the expansion for companies like RealD.

Lewis doesn’t exactly win me over either with his notions of what to do with 3D. He’d like to convert Singin’ in the Rain into 3D. That and The Love Bug. You know, the great classics. Plus he has a rather peculiar idea of Avatar‘s place in film history. Asked what Cameron’s film did for the business of 3D, Lewis responded: “It legitimized it. It was the Citizen Kane of our medium. After Avatar, I finally didn’t have to go into a meeting and explain why this was going to be important for our industry. The numbers spoke for themselves.” No doubt Avatar‘s phenomenal box-office success made exhibitors who had not yet installed 3D equipment keen to do so. But Kane was in fact not a financially successful film. No one could say of it, “After Kane, I didn’t have to go into a meeting and explain why deep focus was going to be important for our industry. The numbers spoke for themselves.” Both films are undoubtedly historically important, but there’s really very little comparable about them.

Auteurs to the rescue?

Speaking of legitimacy, Lewis is looking forward to the releases of Martin Scorsese’s Hugo in November and Ridley Scott’s Prometheus next year. On August 12, the Wall Street Journal ran a long story by Michelle Kung on how a trio of Movie Brats are about to reveal their first 3D films. Hugo is scheduled for November 23, Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin for December 23, and Francis Ford Coppola’s Twixt premieres in September at the Toronto Film Festival.

Spielberg’s popularity among a broad range of audiences remains intact, though whether Belgian import Tintin can win American spectators’ hearts remains to be seen. Whether Scorsese and Coppola, beloved of audiences of my generation, will prove the final boost that 3D needs is up for grabs. Coppola seems a particularly unlikely auteur to pin one’s hopes on. Twixt, a low-budget horror film, has only five minutes of 3D footage, and it has yet to find an American distributor. According to Anne Thompson’s blog, the director “first showed the film to distributors in Los Angeles Wednesday night [i.e., August 24]. Unless he gets a rich offer, Coppola will likely four-wall the film himself; he’s looking to sell video rights.” Today’s Variety reports that Pathé has picked up Twixt for “international sales and distribution in France.” That doesn’t seem to settle the question of a U.S. release.

A more likely shot in the arm for 3D would seem to be Peter Jackson’s Hobbit film, being shot even as I type. It should appeal to teenage 3D buffs and just about everyone else. But the first part is not due out until December, 2012. I suspect that the degree to which 3D will penetrate the theatrical market will be known by then.

The article quotes Jeffrey Katzenberg, who years ago claimed that every screen would eventually be converted to 3D, as saying “You now have some of the greatest filmmakers in the world stepping into the format to tell their stories.” Scorsese has gamely stepped up to the plate, commenting that if 3D had been around when he made Mean Streets or Taxi Driver or Raging Bull, “those stories would have fit in perfectly in 3-D.” It’s a bizarre thought, but maybe he’s serious.

Kung provides some interesting figures. It’s difficult to get a sense of how many people are opting to see 3D films in their 2D versions. Usually the comparison is made in terms of box-office gross rather than number of tickets. But the author says that 57% of people who saw the final Harry Potter film this summer opted for 2D, which seems a pretty significant figure. She also notes the falling stocks of RealD and other 3D firms:

“Consumers are pushing back,” says Richard Greenfield, an analyst at brokerage firm BTIG. “They’re tired of 3-D, both from a price perspective and from a physical-comfort perspective.” He adds that consumers have come to a key realization: A bad film in 3-D is still a bad film.”

Kung says that about 30 new 3D films are due for release next year. If Lewis’ figure of 40 for 2011 is accurate, that means a notable drop in planned 3D productions for the short term. Possibly it’s a temporary one, but perhaps studios are beginning to think that the extra returns from their share of those ticket premiums aren’t worth the cost and effort. If 57% of Harry Potter‘s audience opted for 2D, then perhaps an increasing number of theater owners are refusing to book 3D films from the distributors.

That figure of 30 releases doesn’t include the announced 3D conversions of Titanic and the Star Wars series, which may or may not be ready for release next year. The rumors of such conversions for these and other popular items like the Lord of the Rings film have been circulating, but precious little information on how, when, and where these will eventually reach theaters has been forthcoming.

As I’ve said in my previous posts on 3D, I don’t see any reason why the format would necessarily disappear. Once the match of number of 3D screens and number of moviegoers who want to see 3D movies reaches a reasonable balance–which at this point seems to mean a significant number of current 3D screens reverting to 2D–both formats will make money and 3D will continue, especially for blockbusters and teenage-oriented genre films. But the idea that studio and company executives can simply dictate that the entire public should embrace what is, after all, a relatively superficial technology added onto an already stable and successful product seems overweening and implausible. This summer’s movies have seemingly reflected the public’s more realistic attitude.

And now, enough of 3D. Unless something dramatic happens between now and when Hugo comes out, I shall hold off writing on the subject until we see what happens during the holiday season, when the format faces its next big test.

P.S. August 31: The Fandor blog has a post by Alejandro Adams, a filmmaker who manages a multiplex in northern California. He reports that until recently, studios demanded that all 3D films be shown only in 3D, no matter how many screens were available. Adams reports that this summer: “We’d just opened Captain America ‘over/under,’ meaning that we were offering two 2D shows and three 3D shows in a single auditorium. This was the first time any studio had allowed us to restrict the number of 3D shows. When I checked the grosses after opening day, I was alarmed. We sold twice as many tickets for 2D as 3D. As we’d never booked a 2D engagement of any film available in 3D, I’d never seen this disparity up close. The fact that we were permitted to over/under Captain America in 3D and 2D is itself a distressing development—are the studios suddenly willing to admit they didn’t hit the jackpot with the 3D craze? Are they going to start phasing out 3D so soon after we went to the trouble and expense of making our projectors and screens compliant with their demands?”

Adams calls this a “distressing development,” being a fan of 3D, both for his own and his children’s enjoyment. If my hunch turns out to be correct, they will still have the 3D option, but others will have access to 2D screenings.

RealD’s Michael Lewis. Hmm, those glasses do look a bit clunky. (Photo by Peden + Munk)

Despoiling the movies

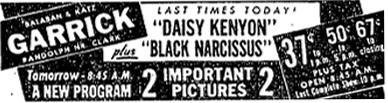

The Denton Record-Chronicle (28 December 1947).

DB here:

The last line of Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon is “When it comes to modern combat tactics, you’re both babies compared to me.” If you haven’t seen the film, does knowing that ruin it for you? Suppose I went further and identified the character who spoke the line, or the immediate circumstances, or the action leading up to it? Would knowing these things ruin your pleasure? Or would it give you a different sort of pleasure?

Who doesn’t come to Casablanca knowing about “Here’s looking at you, kid,” or “Play it, Sam,” or “Round up the usual suspects”? You likely saw the ending of King Kong in compilation films before you saw the whole movie, yet you probably still watch it with enjoyment. I saw Potemkin’s Odessa Steps sequence many times, on an 8mm reel I bought as a kid, before I saw the whole movie. I still enjoy Potemkin, possibly more than many who see it for the first time. Yet people complain about trailers that tell too much, and critics who give plot twists away. Accordingly, it’s been a convention of fan and Net writing that if you’re going to give away major story information, you alert readers with the word “spoiler.”

Surely people want to know something about a film’s story. Viewers clamored for the most basic information about Super 8. And evidently many moviegoers would feel less disgruntled about The Tree of Life if they had known in advance a little bit more about what they would encounter. It seems we want to know about the story’s basic situation, but not too much about how things develop. Say: bits from the first half-hour or so, up to the beginning of the Second Act (or what Kristin calls the Complicating Action). Beyond that, we want things kept quiet. Above all: Don’t tell the how things turn out in the end.

I’ve been driven to think again about spoilers after Jonah Lehrer reported on an experiment with literary texts. On the whole, readers in the study reported enjoying a short story somewhat more if they knew the ending in advance. Jim Emerson has provided his characteristically stimulating commentary on this finding, and his readers, surely among the most reflective in the online film community, have supplemented his thoughts.

This discussion overlaps with a question I raised a while back on this site. How can we feel suspense if we know a story’s outcome? One standard answer, which would apply to spoilers too, is that even with foreknowledge, we’re interested in how that turn of events comes about. This possibility is invoked by some of Jim’s readers, and it seems plausible, especially if one is a connoisseur of storytelling. How, we ask, does the narrative engineer this or that twist?

My further proposal in the blog entry was that our mind’s intake of narratives is modular in some respects. Part of us reacts as if we were encountering the events fresh, without knowledge of what is coming up. The analogy was to standing on a balcony overhanging a precipice. You know that you cannot fall, but when you imagine yourself falling, you feel a twinge of fear all the same.

The same might be true of consuming a narrative. One of our mental systems, fast but fairly dumb, reacts to things as they come, while secure knowledge hovers more distantly in the background. I suggested as well that the way that something is presented–say, with fast cutting or sweeping music–can override our knowledge and kindle a basic, more visceral response.

Today’s entry tackles the matter of foreknowledge from a different angle. It’s worth remembering that many people who went to the movies in the 1920s through the 1950s willingly subjected themselves to spoilers.

This is where we came in?

Chicago Daily Tribune (4 January 1948).

While the American studios developed their storytelling strategies in the 1920s and 1930s, movie exhibition became a big business. In 1935, eighty million Americans went to the movies every week. The historical high point was 1946-1948, when annual attendance hit 4.7 billion. But how did all those people see the movies? More specifically, did they watch them from start to finish?

We’re so used to showing up at a definite time for a screening that it’s hard to imagine a period when many viewers would simply drop in to what were called “continuous admissions” or “continuous performances.” In major cities, the film programs, complete with newsreels, cartoons, trailers, other shorts, and even a second feature, would run steadily with only brief intermissions. You could drop in any time.

When the houses filled up, prospective viewers would have to wait in line outside or in the lobby until someone left. Then an usher would show the next patron to the empty seat. Meyer Levin’s novel The Old Bunch describes a group of friends waiting forty-five minutes before just getting into the lobby of a Chicago theatre in the 1920s.

Some of the viewers would depart during the main or second feature. Naturally, the patrons admitted in medias res would see the end of a movie before they caught up with the beginning, perhaps some hours later. Hence the phrase, “This is where we came in,” meaning, “Now we’ve seen the whole picture and can leave.”

After Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, a few readers asked why we hadn’t talked about continuous admissions. The practice would seem to explain a lot about the redundancy of Hollywood storytelling. Hyperexplicit exposition, the Rule of Three (say everything important thrice), and the habit characters have of reminding us of their relations to each other (“Gee! You’re the swellest sister a guy ever had!”)—all this would seem to be aimed at a viewer who might well have come in halfway through and need orienting to basic plot premises.

We knew about continuous performances, of course, but we didn’t discuss them because we could find no evidence that filmmakers took these conditions into account when designing their stories. In reading Hollywood screenplay manuals, technical journals, and the like, I didn’t find anyone commenting on the exhibition practice. My colleague Lea Jacobs, who has scanned Variety very comprehensively for the 1920s and 1930s, can recall no mentions of it affecting production policies.

When you think about it, screenwriters and directors couldn’t really do much to bring a latecomer up to date. You can’t keep reiterating story premises and recapitulating all that went before, and still move the plot forward. Better to tell the story straightforwardly and assume, as a default, that under ideal circumstances people would see the whole film from scene one onward. The same assumption governs TV writing, despite viewers’ channel surfing and foreplay with the remote.

Still, during the Golden Age of Hollywood a significant population consumed movies knowing how the story turned out before they saw the beginning. Ask people of my generation or older, and you’ll usually hear: “Oh, we went whenever we wanted. We never tried to find the showtimes.” My childhood moviegoing memories are dim, but I recall being dropped off at the Elmwood Theatre by my parents when they went to town. I’d go in during the movie (I do recall The Sad Sack, 1957) and watch until my mother or father fetched me out. It’s very likely that adults drifted in at odd times as well.

There’s harder evidence that some people preferred convenience to coherence. In 1950 Twentieth Century-Fox announced that All About Eve (1950) would be screened only in “scheduled performances.” No one would be seated after the film began. Premiering at Manhattan’s Roxy Theatre, Eve ran for a week under the new policy. It failed. People hadn’t heard about the new rules, showed up late, and weren’t admitted. The results were angry lines outside and empty seats within. The practice was halted and Eve screened in continuous performance. The Hollywood Reporter attributed the failure to “the public’s deeply ingrained habit of going to a movie show at any desired hour, when most convenient or on impulse.”

In other words, many people were encountering what we call spoilers all the time, and it didn’t seem to bother them. So you wonder: Is watching a movie straight through, as we mostly do today, a newer, more “disciplined” mode of consumption?

It’s showtime

Daisy Kenyon.

It’s obvious that the custom of just dropping in didn’t guarantee a nonlinear movie experience. With a double-bill house, even if you dropped in arbitrarily, you would see one feature or the other in a single gulp. And assuming a three-hour program and a 90- or 95-minute A picture, your odds of walking in during the shorts or the B film were about fifty-fifty.

But were people obliged to drop in willy-nilly? Could they have seen the movie straight through if they wanted to?

There’s considerable evidence that parts of the audience did want to see the movies in linear fashion.Consider the early attenders. And many cinemas filled up quickly just before the show started. Coming in when the theatre opened seems a fairly clear indication of wanting a linear experience. True, early attenders would probably have to sit through a newsreel, trailers, and other shorts, but many people enjoyed those too. Further, since double-bill houses screened the A picture first, knowing that custom could guide your decision about when to come in.

Could patrons have gained specific information about when the movies were screening? There’s a widespread belief that theatres didn’t publicize showtimes. But that’s not the case.

First, the box office almost always posted a schedule breaking down the program. Sometimes cardboard clocks with movable hands indicated showtimes. Patrons might see the schedule when they arrived, or while passing the theatre during the day. Knowing the schedule, you didn’t have to go straight in. If you bought your ticket while the feature was running, you could linger in the lobby. Probably some viewers were reluctant to enter if the feature they wanted to see was just ending.

Second, there were newspaper advertisements. This evidence is varied and intriguing, full of unexpected quirks. First, I took a look at late 1940s ads for the Elmwood, my hometown venue. These ads are mostly bare-bones. They list the movies, all double features, with three changes a week (films played Friday-Saturday, Sunday-Monday, and Tuesday-Thursday). The theatre doesn’t supply its phone number, probably because many families in our area didn’t have phones until the late 1950s. Showtimes are seldom mentioned. Doubtless townfolks knew by local custom what the showtimes were, and there was no need to advertise it in newspapers or handbills (which were still around in the 1950s). One September 1949 item specifies opening and closing hours:

Matinees Daily 2:00

Evenings 7:00 to 11:30

Sundays and Holidays Continuous 2:00 to 11:30

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

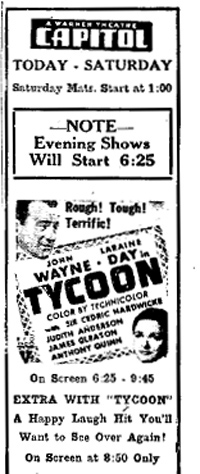

But some ads in other towns get a little more specific. “2 COMPLETE SHOWS 9:30 & 12 MIDNITE,” blares the Colonia of Norwich, New York in 1947. This indicates the starting times for the newsreel, cartoon, and ads, which all preceded the main feature. But since many theatres began their screening at 6:00, the accompanying ad from the Capitol, of Dunkirk, New York in 1948 seems to be saying that after all the shorts and ads, Tycoon hits the screen at 6:25. That movie ran a little over two hours, so there was time for filler leading up to the Happy Laugh Hit (presumably a revival). More unequivocal is the ad for Daisy Kenyon at the very top of this entry, which specifies when the feature starts. Again, the theatre probably opened at 1:00 and brought in the evening crowd at 7:00. That left fifteen minutes or so for pre-show material, including the color cartoon and “Global News”.

In short, some newspaper ads tell us only the theatre’s operating hours, while others specify showtimes. This sort of variation goes far back. The Olean (New York) Evening Herald advertised the Strand Theatre as “showing continuously 1 to 11 daily,” with no showtimes mentioned. On the same page we find specific starting times listed for a rival theatre’s showings of Fairbanks’Mark of Zorro (1921).

For special occasions, the scheduling could be quite exact. If you happened to be in Middletown, New York, on New Year’s Eve of 1947, you could welcome in “Kid 1948” at a gala show starting at 7:00 and ending “some time in 1948.” But not just “some time”: The State’s plan has a military precision.

Daisy Kenyon at 7:00 – 9:29 – 12:01

Comedy “Skooper Dooper” at 8:38 – 11:08

Terrytoon Cartoon “Silver Streak” at 9:12 – 11:42

Community Sing at 9:19 – 11:49

Latest Pathe News at 8:56 – 11:26

The ad goes on:

No seats reserved – No waiting in line. Come any time from 6:30 until 11:20 and see a complete show—Stay as long as you like! Come in one year—Leave the next!

The rival Goshen Theatre likewise provided a detailed schedule of its New Year’s Eve attractions, an astonishing four features plus cartoons. The show, broken into 9 “units,” started at 7:00 and ended at 1:00 in the morning, concluding with an “Exit March.” Why don’t movie theatres have exit marches any more?

Apart from ads specifying showtimes, we can glean other hints that at least some viewers preferred to know when to arrive to catch a film from the beginning. Some newspapers published lists of starting times. The New York Evening Post printed an extensive “Movie Clock” covering over eighty theatres. A Schenectady paper did the same thing under the rubric “Showing Today. What the Theatres Are Advertising.” You can find a similar feature in papers from Portland and Council Bluffs. Movie houses were often a small-town newspaper’s biggest and most reliable advertising source, so many editors were ready to oblige theatre managers.

Movie ads also sometimes included the theatre’s phone number, so people could call to check showtimes. Access to telephones was still spotty then; recall that the infamous Gallup Poll of 1948 misjudged Dewey’s chance for victory, partly by relying on phone surveys. But by 1945 there were about 16 million residential phones for a population of 140 million, so the middle-class people sought by exhibitors, then as now, might well be able to call up the movie house.

That is, in fact, what Daisy Kenyon does at one point in her movie. Having decided to go out with her girlfriend, she checks the phone number of the theatre she wants to visit and starts to call to check on showtimes. (She’s interrupted by a call from the mysterious Peter Lapham.) The scene seems to model one set of urban filmgoing habits.

Historian Douglas Gomery reminds us that there were many different sorts of theatres–first-run and subsequent-run, big downtown houses and neighborhood venues, rural ones, art houses, and so on. I’ve tried to capture some of this variety in my exploratory sample, but there are many fine-grained differences. Moreover, roadshow pictures often played to strict schedules, selling tickets for specific performances, and people adjusted their schedules to that regime for Gone with the Wind and other blockbusters. Perhaps the All About Eve fiasco came from people thinking this new film, in black-and-white and offered at regular admission prices, was not an event film like the usual roadshow attraction.

In all, it’s hard to generalize about viewing patterns. But it seems fair to say that in many circumstances viewers could, if they wanted, avoid seeing a movie’s ending before the beginning.