Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Back to the vaults, and over the edge

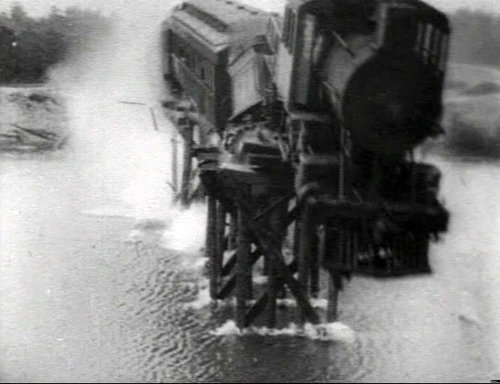

Unstoppable? Not really. The Juggernaut (1915).

DB here:

A few weeks ago, I praised Variety for making its back issues available digitally. The result is a magnificent vault of information. I also expressed frustration that the recent makeover of The Hollywood Reporter neglected to offer access to its original online archive, which indexed issues across the last twenty years. On the last point, some news.

First, my inquiry to the address listed on the HR website eventually yielded this blue note.

Good Morning,

We apologize for the delayed response.

I do not think there is a way to go back to prior to the changeover.

You would need to contact the publisher about that, as we do not handle the website directly.

Here is a phone number for you 323-525-2150.

Thank you.

I called the number, which handles only subscriptions, and the person answering had no idea what I was asking about.

But all is not lost. My first efforts to access the archive turned up very little for 2010, but shortly afterward I was able to access items from most of this year. Now, if you type a search term into the Search box of the HR site, it brings up items from as far back as 2008. This is an improvement over earlier attempts I made. It seems that THR is gradually adding old material to their archive, in reverse order.

Unfortunately, the search mechanism is quite indiscriminate. Searching “Johnnie To,” with and without quotation marks, yielded 290 hits, but I could find no articles about Johnnie To. Instead, the items with highest relevancy concerned Johnny Depp, Johnny English, John McCain, and the new Narnia movie.

The best news of all came from alert reader David Fristrom of Boston University. He advises me that the old HR archives are still available through LexisNexis. So I tried there with Johnnie To, and I got 338 references, stretching back to 1992. The ones at the top of the relevancy scale were indeed about Mr. To, including a Cannes piece called “Fest’s Red Carpet Flows with Blood.”

Accessing the archive isn’t straightforward, but you don’t need a subscription to HR if your library has purchased access to LexisNexis. I append David’s instructions at the end of this entry. Thanks to him for sorting this out for me.

Now, back into the Variety vaults.

This one’s a real train wreck

On 12 March 1915, Variety reviewed The Birth of a Nation. Alongside that review sits one of The Juggernaut, a Vitagraph feature directed by Ralph Ince. The reviewer, “Simc.,” dwells almost entirely on what he calls “the train-through-the-bridge thing.” The producers bought an old locomotive and some passenger cars, built a flimsy bridge, and ran their train off into what appeared to be a river.

The review exhibits some Variety touches that are still with us. Take the (quite reasonable) idea that nearly every movie is too long. “If this five-reeler were cut down to three reels, which could easily be done, the Vitagraph would have a real thriller.” There’s also the notion that people who come to the see the movie should be aware of its main attraction. “If the audience knows a train will go through a bridge at the finish, it won’t mind the fiddling about in the first four reels before that scene is reached. But if the audience doesn’t know what is to come, there may be many walk-outs.” At the beginning of Unstoppable we’ll sit through all the union and non-union wrangling and alpha-male preening if we’re sure we’re going to see a train that is certifiably unstoppable, except that it’s likely to be stopped by our heroes.

The Juggernaut does give us a pretty spectacular train wreck, as you see above. The entire film may not survive, but we have a version of the last reel (perhaps because a collector thought it worth saving). Train or no train, the film is of interest in showing what Griffith’s rivals were up to.

The plot centers on a crooked railroad magnate, Philip Hardin, and his college friend John Ballard. In the reel we have, Hardin’s daughter Louise, who loves John, sets out on an errand. When her car stalls she boards an express train. A track-walker finds worn ties on a bridge and warns the company, but too late. As Hardin races to stop Louise’s train, it arrives at the bridge and he watches it topple into the water. The sight kills him on the spot. John arrives and swims out to rescue Louise.

That’s when things get dicey. According to the Variety review and other sources, Louise dies in the wreck. Simc again:

The leading woman of the film, Anita Stewart, is discovered dead, lying against one of the windows, with particular pains taken that her features shall be clearly visible. . . . Anita is carried to shore and lain alongside of her father, who had died of heart failure (on land) a few moments before.

In the version available on DVD, John does bring her body ashore, but she revives, lifts herself up, and embraces him. The print ends there. Why the varying ending? Perhaps this is a version made at the time for a different market or in response to censorship, or it might be a rerelease using alternative footage. Or perhaps the press reviews were based on a synopsis supplied by Vitagraph, and the studio made modifications in the print before release.

The Juggernaut is also intriguing stylistically. By this point, crosscutting and scene analysis were common techniques in U. S. films. To set up the perilous situation, the cutting alternates shots of the track-walker, of Hardin, and of Louise. Once Hardin discovers that Louise is on the train headed for the dilapidated trestle, we are set up for a last-minute rescue–which fails. A particularly interesting series of shots shows Hardin’s trajectory converging with the train’s path. Riding in a power boat, Hardin looks back and we get a shot of the train in the distance, suggesting that he can see it.

From this we cut to a shot of Louise, confirming that she’s on board and showing her innocent lack of awareness. Then we get a repeated framing of the train rushing toward the bridge.

After another long shot of the train, we get a shot of Hardin in his powerboat with the train whizzing by in the background. This confirms that he was indeed watching it approach off screen left in the earlier shot, and it shows that he isn’t likely to catch up.

Once the train has toppled into the stream, there are some striking shots of people trapped inside or scrambling to escape. We see Louise raise one hand and then freeze, as if dying.

Earlier, there’s some emphatic “classical” cutting when Hardin learns that Louise is in danger. An enlarged framing (via an axial cut) underscores his reaction to the telegram.

Most striking is a series of shots of the dead-or-not Louise; the abrupt enlargement of her face has something of the force that Kurosawa would channel in his axial cuts.

Soon Ralph Ince cuts back along the same camera axis, and inward again as the couple embrace.

I can’t recall a comparable stretch of “concertina” cutting in the intimate scenes of Birth, and no such tight views of faces either. Griffith sometimes gives us “close-ups within medium-shots” by means of irising and vignetting.

Other directors (e.g., Dreyer) liked to use the serrated surround to highlight faces, but the American norm eventually became the unadorned closer view, as in the shot of Louise in The Juggernaut. Such shots probably saved production time as well. We’re confronted with the familiar situation that sometimes non-Griffith films from 1915 (e.g., The Cheat, Regeneration) look somewhat more “modern” than does Birth.

Going back to the train-through-the-bridge thing, the staging of the scene in late September 1914 elicited a lot of publicity. For one thing, the cost was played up; I’ve seen stories claiming $20,000, $30,000, and $50,000. The New York Times wrote up the shoot twice; the second of these could well be a publicity release from Vitagraph. According to the Times, the “river” was actually a flooded quarry. Before the shoot, buzz leaked out and crowds reported as numbering thousands showed up to watch. The crew spent hours herding them out of camera range. Actors were freezing in the water by the time cameramen got to take their shots. The Times also claims that the crash was filmed by fifteen (or twenty-five) cameras, a stupendously implausible number, especially in light of the footage we have. Worse, according to the second NYT story, Ince decided that the first pass didn’t work and they would have to start all over with a new train! A retake is not mentioned in Variety’s coverage, which does report some studio rivalry:

The ink on the New York dailies telling of the Vita’s big wreck stunt in the cameraing of “The Juggernaut” had hardly dried when the Universal sent over camera men posthaste Sunday to take views of what was left of the wreck. [Vitagraph studio manager Victor Smith], getting a hunch, got on the ground ahead of them and with a sturdy band of Vita “protectors” nipped the U’s little scheme in the bud.

One can only imagine how the “protectors” dealt with the Universal boys. Once more, the Variety Vault gives us the flavor, and perhaps sometimes the facts, of heroic times.

How to access the Hollywood Reporter archive, courtesy David Fristrom:

Once you are in LexisNexis, it can be a little tricky to search in The Hollywood Reporter (for some reason it doesn’t show up if you type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Source Title” box), but you can follow these steps:

1. Click on “Power Search” in the upper-left corner.

2. On the “Power Search” page, find the “Select Source” box (near the bottom) and click on the “Find Sources” link.

3. On the “Find Sources” page, type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Keyword” box and press enter.

4. At the top of the results should be “The Hollywood Reporter.”

Check the box next to it, then click on the “Ok-Continue” button that appears in the upper right corner.

5. You are now ready to search in the Hollywood Reporter archives –just type your search terms into the search box.

Thanks again to David!

The Variety review of The Juggernaut appears in the issue of 12 March 1915, p. 23. The story about Universal staff trying to shoot the wreckage is “Vita Putting It Over,” Variety, 10 October 1914, p. 23. The New York Times articles are “Film Train Wreck Almost a Tragedy,” NYT, 28 September 1914, p. 13, and “Tossing Dollars Around As If They Were Pennies,” NYT, 18 October 1914, p. X7. For more on Vitagraph, see Anthony Slide, The Big V: A History of the Vitagraph Company, rev. ed. (Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1987); Tony provides some production background on The Juggernaut on pp. 64-65.

The Juggernaut excerpt is available on Nickelodia 2, a DVD collection from Unknown Video. Oddly, the snapcase doesn’t list the reel as included on the disc, nor does the product information on the Unknown Video site or Amazon. I’d welcome more information about The Juggernaut‘s plot resolution if anybody out there has any.

The Juggernaut (1915).

Trade secrets

DB here:

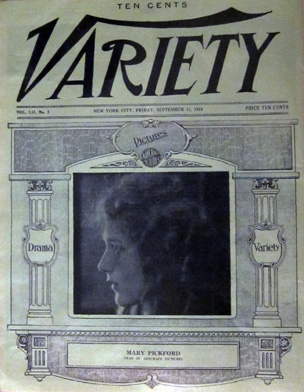

Over the last couple of months, some strange things have been happening to America’s most venerable show-business trade papers. In the case of Variety, the strange thing is very important and yields almost unalloyed good news. In the case of The Hollywood Reporter, the strange thing is, at least for the moment, a step backward.

Kristin and I have subscribed to weekly editions of both newspapers since the mid-1990s. With the advent of Web 2.0, each paper created an online archive, more or less searchable, stretching back into the 1990s. Not everything you would wish for, since Variety started publishing in 1905 and The Hollywood Reporter began in 1930. But film historians are grateful for anything. I found both papers’ archives very helpful in reworking Planet Hong Kong over the last year. Now, however, some of the recent happenings affect our ability to do research.

Issues about issues

First the bad strange new thing. In a collapsing advertising market, The Hollywood Reporter has done a makeover. From being a daily and weekly trade paper it turned into an upscale lifestyle weekly, sort of an industry-slanted version of Vanity Fair‘s movie issue, with a soupçon of airline magazine. Among the recycled press releases, superficial interviews, soft-focus profiles, and awards-season handicapping, you find fashion tips like “Into the Blue: Punch up your executive look—top to toe—with the season’s blockbuster hue.” There’s also the sort of feature that movers and shakers can use to promote themselves: “Hollywood’s Young Guns ….Where they work, why they matter, how they’re changing the game.”

True, Variety sometimes resorted to such frippery in these desperate years. V-Life was in some ways a forerunner of the new HR, but V-Life was a supplement. In the main paper you could still find reportage, analysis, overviews, and opinion. There’s relatively few of these ingredients in the new Hollywood Reporter.

If this is the strategy for fighting Movie City News and Deadline Hollywood and IFC, I’m betting on the webroots.

Anyhow, forget the daily THR ephemera. I want to go into the past, as I did until October, scrambling through elusive coverage of Hong Kong stuff. Problem is: I can’t do that any more.

THR not only remade its magazine; it remade its website, radically. So radically that when I go there via Safari or Chrome I get this welcome.

Well, you say, skip your bookmarks and go through Google. But then:

Only Firefox does the trick.

Anyhow, at last I’m on. Breaking News today starts with “Jennifer Grey Wins ‘Dancing with the Stars’; Bristol Palin Comes in Third.” Skip that. As a subscriber, I ought to be able to log in to the proprietary content, right?

Here is the routine. Using my old password, I have no luck. When I call the 800 number, an ominous recording tells me that they are aware of the “issues” (what we used to call “problems”) with the website and subscriber logins. After half an hour, a hard-working person answers and with a few magic passes of her mouse she gets me into the subscriber areas.

Yet the next time I try, I’m refused again. So I write to the email service they announce, and immediately get a form reply saying that my problem will be addressed in 1-2 business days. The next communiqué, from some days later, begins: “We apologize for the delayed response.” They give me a password which is suspiciously generic.

This has been going on for nearly three weeks. But I can live with it because I’m not so concerned with Jennifer Grey or Bristol Palin. I’m there for the archive.

Problem is, the Archive isn’t there for me. Once I’m inside as a subscriber, I find no way to get into the two decades of stories and stats I could reach under the earlier incarnation of the website.

Another call, another recording apologizing for the “issues,” another half-hour of wait, and now a very puzzled answerperson. Where’s the Archive? Nobody ever asked him that before. He’s no better than I am at finding a button for it. He consults his supervisor. The supervisor doesn’t know where the Archive went either.

You can search the site, he points out. True, but the search takes me only to items posted since the makeover began.

Hmmm. The best they can do is suggest I call the Editorial Offices. When I do, the recording instructs me to leave my story tip and someone will get back to me. I might say, “Psst, I have it on good authority that the next big color will be vermillion,” but instead I hang up.

Trying tonight, I find that the search function now turns up articles published throughout calendar 2010, but no earlier. So maybe THR will gradually expand its backfile. It would be too bad if the dolled-up version of the print mag drained resources from maintaining a stable and deep website. I worry that THR intends to dump the old (already very partial) online archive altogether, resetting the clock at the year of the makeover. If so, they send a signal that the past—theirs, that of the industry they cover—doesn’t matter. They wouldn’t even agree with Jack Valenti, who supposedly did say, “It’s only history,” and then opened the MPPDA papers for research.

Infinite Variety

13 September 2010 was the date of the good thing that happened to the trade papers. At that point, Variety went the opposite direction of The Hollywood Reporter. It opened up its vault completely.

For many years film historians have relied on Variety for detailed information about how Hollywood and other national industries have worked. Most of these historians have scanned the paper on microfilm, cranking through reel after reel, getting dizzy from the whizzing lines your eyes try to fasten on. But these scholars managed to do real research. You couldn’t believe everything you read in the paper, of course; you had to be skeptical. Still, getting something was always better than getting nothing.

More recently, Variety has kept an online archive of its materials since the early 1990s. These stories were in html-friendly format, not in the form of published pages, and some stories that appeared in the paper never made it online or were revised for the net. Older stories, mostly film reviews, were summarized and undated. So as records, they were only partly reliable. Still, even this iceberg-tip was well worth surveying.

In September, though, Variety put online its back file from 1906 to the present. Every page of the weekly and daily paper has been digitized. You can access it for a year for a $600 subscription fee, probably what many people pay for designer coffee over the same period. If you want shorter-term access, $60 gets you into up to 50 issues per month.

Reader, I signed up.

There were teething pains for a few weeks. Some pages failed to load, and often you had to scroll through an entire issue to find the page you wanted. But those “issues” are mostly in the past. Now you can plunge into an ocean of well-mapped movie coverage.

As usual with people of my generation, I’m shaken by the abrupt transition from a research economy of scarcity to one of overabundance. Had this bounty existed when Kristin and Janet Staiger and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we might still be writing it. Type in “John Ford” or “Meet Me in St. Louis” and you’re led into the labyrinth, with one item teasing you to search others, forever.

Some things, for instance, seem never to change. “CINEMAS TO SURVIVE HI-TECH ERA,” wrote A. D. Murphy in the 4 August 1982 issue’s top story. People were claiming that the theatre experience would soon vanish (presumably because of home video, although that’s barely mentioned). No way, says Murphy, citing several reasons, including the plausible assumption that “Nothing yet has managed to keep young people confined to their homes.” He adds that going out to the movies is the most robust form of “pay per view….free of all that bother of billing, dunning, disconnects and such.”

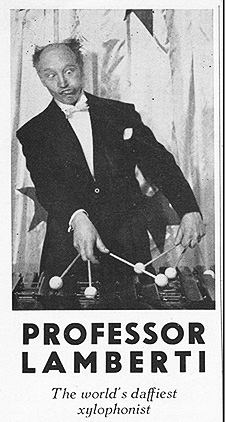

Yet a stroll through the vault can also remind you of how strange things were back then. How’d you like to sit through a live opening act before Citizen Kane? Variety tells us that in San Francisco’s Golden Gate theatre in early September 1941, Kane did brisk business at popular prices. It was accompanied by the vaudeville act of one Prof. Lamberti. The local Hearst newspapers, while refusing to advertise Kane for the unsurprising reason that Hearst thought the movie was about him, did advertise Prof. Lamberti’s act at the house. He was worth paying attention to. He never made snide fun of Marion Davies.

Yet a stroll through the vault can also remind you of how strange things were back then. How’d you like to sit through a live opening act before Citizen Kane? Variety tells us that in San Francisco’s Golden Gate theatre in early September 1941, Kane did brisk business at popular prices. It was accompanied by the vaudeville act of one Prof. Lamberti. The local Hearst newspapers, while refusing to advertise Kane for the unsurprising reason that Hearst thought the movie was about him, did advertise Prof. Lamberti’s act at the house. He was worth paying attention to. He never made snide fun of Marion Davies.

But who was Prof. Lamberti? A magician, a musician, a real prof? We check Variety for 22 March 1950 and learn from his obituary that “Professor” Lamberti was a comedian who played on stage and in nightclubs. According to the obit:

Lamberti’s best known act was playing the xylophone, while shapely gal did a striptease back of him and he was apparently unaware of the goings on. This provided the delusion that successive encores on the semi-classic tunes such as “Listen to the Mocking Bird” were prompted by the audience’s music appreciation, rather than the bumps and grinds of the peeler. Howl finish had the comic get hep and seltzer squirt the gal off stage.

I ask you: How could a red-blooded American male viewer concentrate on the ambiguities of Thompson’s quest after an opening act like that? And as a mood-setter for the opening sequence at Xanadu, the World’s Daffiest Xylophonist might not be ideal. Even more striking, we learn from the same obit that Prof. Lamberti did his signature bit in the film Tonight and Every Night (1945) with Rita Hayworth “as the strip-gal”—the same Rita Hayworth who was then married to Citizen Kane’s director.

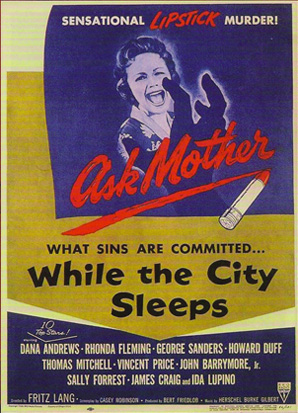

Aha, you say, but Wikipedia has an article on Prof. Lamberti too, and with more details than the Variety obit. (Please visit this orphan entry; it needs hits.) I would never badmouth Wikipedia, that wonder of our young century, but it’s not yet the poor man’s Variety vault. For one thing, it doesn’t use the phrase “bumps and grinds of the peeler.” Further, I can find no help on Wikipedia on a looming question that has vexed some of our best minds: At what aspect ratio should Lang’s While the City Sleeps (1956) be shown?

A lack of ‘Scope

There is a full-frame version occasionally broadcast on Turner Classic Movies and now available on Region 2 DVD. There’s also a 1.66 crop that was released on laserdisc many years ago. Some older cinephiles recall seeing a widescreen anamorphic version circulating on 16mm. Yet Lang apparently claimed he did not shoot the film in anamorphic widescreen.

When While the City Sleeps was made, the releasing studio RKO was supporting a widescreen system called SuperScope. That’s what Variety called it, anyhow, though sometimes you’ll see the name with a small middle s, or with “Super” italicized.

Invented by the brothers Joseph and Irving Tushinsky, SuperScope was a progenitor of the Super-35mm system of today. A film shot in standard full-frame 35mm would be turned into an anamorphic one. A portion of the frame was extracted, optically squeezed, and printed as an anamorphic image, which would then be unsqueezed in projection. The aspect ratio was 2.0:1. The reasoning was that it was easier to shoot a movie in the standard way and then “SuperScope” it than it was to shoot a CinemaScope film. Some projectionists called this process BogusScope, not just because it was fake but because Benedict Bogeaus was then a producer feeding projects to RKO, and some of his titles used the format.

Slightly Scarlet and Invasion of the Body Snatchers, both released in 1956, were designed to be given the SuperScope treatment. The films carry the logo in their credits, and contemporary Variety reviews mention the process by name (15 February 1956 and 29 February 1956). The accompanying Italian poster for While the City Sleeps also makes reference to the SuperScope process. But there is no mention of SuperScope on the release print, or in the Variety review (2 May 1956), or in the US release poster, or in the pressbook kindly posted online by TCM.

Lang is on record, in Peter Bogdanovich’s Who the Devil Made It, as saying that he disliked CinemaScope. He told Bogdanovich that he agreed with his famous claim in Godard’s Contempt that “CinemaScope is only good for snakes and funerals” (p. 224). But SuperScope is not CinemaScope (which is 2.35:1 or sometimes even wider), and moreover Lang made one of the better CinemaScope films in Moonfleet (1955). So the question can’t immediately be resolved on auteur grounds.

Moreover, SuperScope prints of While the City Sleeps do exist. I found one in a European archive some years ago. It was pretty fuzzy (a chronic problem with SuperScope prints, because of the rephotography involved), but I took some frames from it. Here are some comparisons with the 1.37 DVD.

For my purposes here, I could have simply cropped and blown up the full-aperture frame grabs, but I’d rather preserve the slightly bulgier quality that seems to have come with the anamorphic optics. Also, because the wider versions are from 35mm frames, they include a little more area on the sides, which is lost in video versions like my DVD grabs on the left.

Actually, the widescreen version isn’t terribly offensive to me. For one thing, it slices off that slab running across the top of the bar set in the first image above. But in some cases the change in shot scale and internal relations make for mild differences in emphasis. The SuperScope version brings characters quite a bit nearer to us. Do they also seem seem closer together? There’s also the matter of taste. Some will dislike the headroom in the left shot below, while noting that the right one looks like a classic early ‘Scope composition.

So which one is the original? You can sample the online cinephile discussions from 2003 onward here and here and here. The ever-diligent folks at DVD Beaver have much to add as well.

Fortunately, about five minutes of snooping in the Variety vault reveals the answer.

Joseph and Irving Tushinsky yesterday concluded a contract with RKO for conversion of “While the City Sleeps” into the SuperScope process for foreign release (“SuperScoping ‘City,’” Variety, 12 April 1956, p. 3).

According to other stories in Variety, several films were given the SuperScope treatment ex post facto, including a re-release of Olivier’s Henry V (1945).

So we can confirm the hunch expressed by some of the cinephiles above that the SuperScoped copies were destined for overseas screenings. The Variety vault proves useful for things both great and small. Okay, mostly small, but you get my point.

Scoping things out: An epilogue for ratio fetishists

SuperScope logo for Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

There’s still all that headroom in the full-frame images. That roominess is fairly uncharacteristic of Lang. In his pre-widescreen films, he used the whole frame, even the corners. Try SuperScoping this tightly-packed shot from Kriemhilde’s Revenge.

In Cloak and Dagger, Cooper’s character uses the apple on the workbench to explain the power locked up in the atom, and apples will become thematically significant in a later Adam-and-Eve scene.

Moonfleet also takes advantage of the lower right corner (see the image at the very end of today’s entry). But Lang’s last two American films, While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), seem to me to have more open and less compact compositions. There’s quite a bit of unused furniture in City‘s mise-en-scene, even though it adds a Vidor-Fountainhead air of vastness.

At this point we should recall that by 1956, most U. S. theatrical releases were shown in something wider than 1.33. There was a lot of variability, but films were commonly cropped in printing or projection to 1.66 or 1.75 or 1.85. Even if Lang did not shoot City with an anamorphic ratio in mind, he might well have assumed there would be cropping to some wide ratio. The approximately 1.75 ratio seen on the laserdisc version looks like a reasonable compromise between the extremes.

I’m inclined to say that Lang expected the film to be cropped somewhat in projection, but probably not to the full 2.0 proportions. He could no longer count on projectionists’ framing a single ratio, so he doesn’t tuck details along the edges or into the corners.

Unfortunately, I can’t find confirmation of Lang’s wide-frame choices in the fabled Variety vault. But I’m still looking, there and elsewhere. And maybe some researcher reading this entry can clarify things further. In any case, Variety has given a magnificent gift to those of us interested in film history–who ought to be everybody.

The standard source on widescreen systems of the postwar era is Robert E. Carr and R. M. Hayes, Wide Screen Movies: A History and Filmography of Wide Gauge Filmmaking (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1988). Carr and Hayes discuss SuperScope, or as they call it SuperScope (the credit logo is actually in caps, as in SUPERSCOPE) on pp. 67-72 and list the films in that format on p. 104. They don’t include While the City Sleeps. See also Daniel Sherlock’s comments on the book at Film-Tech.

Writing this has led me to wonder whether the admiration of European, especially French, critics for While the City Sleeps is based on their seeing the anamorphic version. In their writings I haven’t found specific reference to SuperScope. Raymond Bellour’s probing 1966 essay “On Fritz Lang” is one of the few I know from that period to scrutinize the patterns of composition and framing in While the City Sleeps, but I can’t tell whether he’s referring to the widescreen version. An English translation is in Fritz Lang: The Image and the Look, ed. Stephen Jenkins; see pp. 31-35.

Although Turner Classic Movies has run While the City Sleeps in 1.37, the TCM website recommends that it play at 1.66. Interestingly, the illustrations in Tom Gunning’s Films of Fritz Lang are in about 1.75:1 ratio. Another SuperScope production, Jacques Tourneur’s Great Day in the Morning (1956), runs on TCM in this ratio. Since projectionists of the period, and still today, are fairly flexible about ratios, it’s possible that even anamorphic 2.0 SuperScope was projected with a little trimmed from the sides.

A DVD release of Invasion of the Body Snatchers includes both a SuperScope 2.0 version and a 1.37 one. But the 1.37 one is a pan-and-scan version of the SuperScope one, not the integral frame that SuperScope worked from. The DVD version of Slightly Scarlet from VCI International is framed at 1.78, and the transfer (of poor optical quality) has been bungled so that everything is slightly stretched left to right. Both Arlene Dahl and Rhonda Fleming are more zaftig than they should be.

For more on aspect ratios, you can go here and here on this site. I experiment with extracting ‘Scope proportions from a 1930s movie in a general essay on widescreen aesthetics, “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses,” in Poetics of Cinema, p. 323.

Correction (28 November 2010): The original version of the piece claimed that the Search function of the Hollywood Reporter website found only pieces published since the recent makeover. That was the case when I used it two weeks ago. A more recent search I conducted this evening turned up articles from throughout 2010. I have recast the entry to reflect this change.

PS (17 December 2010): More developments on the Hollywood Reporter backfile, and more on the uses of the Variety Vault are discussed in this later entry.

Moonfleet.

New Zealand is still Middle-earth: A summary of the Hobbit crisis

Richard Taylor during the October 20 anti-boycott march.

Kristin here:

Ordinarily I post about Peter Jackson’s Tolkien-adapted films on my other blog, The Frodo Franchise. But over the past five weeks a dramatic series of events has played out in New Zealand in regard to the Hobbit production. Those events tell us interesting things about today’s global filmmaking environment. As countries around the world create sophisticated filmmaking infrastructures, complete with post-production facilities, they are creating a competitive climate. Government agencies woo producers of big-budget films by offering tax rebates and other monetary and material incentives. Usually such negotiations go on behind closed doors, but the recent struggle over The Hobbit was played out more publicly.

Back in late September, the progress of Jackson’s project seemed slow. We Hobbit-watchers were mainly fretting over the lack of a greenlight for the two-part film “prequel” to The Lord of the Rings.

Of course, Tolkien’s LOTR (1954-55) was a sequel to The Hobbit (1937), but the films will have been made in reverse order. That’s due to MGM’s having the distribution rights back in 1995 when Peter Jackson went looking to use Tolkien’s novels to show off Weta Digital’s fancy new CGI abilities. Miramax bought the LOTR production and distribution rights and the Hobbit production rights.

Most of the news I was then blogging about related to MGM’s financial problems and how they would be resolved. Would Spyglass semi-merge with the ailing studio, convert its nearly $4 billion in debt into equity for its creditors, and bring it back into a position to uphold its half of the Hobbit co-production/co-distribution deal with New Line? Or would Carl Icahn push through his scheme to merge Lionsgate and MGM? The answer, by the way, came just this Friday, October 29, when the 100+ creditors voted to accept the Spyglass deal. I have been saying all along that the MGM situation was not the primary sticking point that was delaying the greenlight, even though most media reports and fan-site discussions assumed that it was. The greenlight having been given before this past week’s vote, I assume I was right. The real reason for the delay has not been revealed.

Meanwhile, other websites were speculating about casting rumors. Would Martin Freeman really play Bilbo, or were his other commitments going to interfere? (He will play Bilbo. Good choice, in my opinion. The man looks just like a hobbit.)

Then, on September 25 came the news that international actors’ unions were telling their members not to accept parts in The Hobbit. There was a boycott. The result was a maelstrom of events for the past five weeks or so. You may have heard about some of them. There were meetings and petitions. When Warner Bros. threatened to take the film to a different country, pro-Hobbit rallies followed. A visit by some high-up New Line and WB execs and lawyers to New Zealand led to hurried legislation to change the labor laws to reassure the studios that a strike wouldn’t happen. Finally, the government ended up raising the tax rebates for the production. Result: The Hobbit will be made in New Zealand after all. New Line, by the way, was folded into Warner Bros. by their parent company, Time Warner, after The Golden Compass failed at the box office. It remains a production unit but no longer does its own distribution, DVDs, etc.

The news that followed the launch of the boycott has come thick and fast, often involving misinformation. It was complicated, centering on an ambiguity in New Zealand labor laws as applied to actors and on a strange alliance between Kiwi and Australian unions. One of the biggest American film studios decided to use the occasion to demand more monetary incentives from the New Zealand government. I tried to keep up with all this and ended up posting 110 entries on the subject. (In this I was helped mightily by loyal readers who sent me links. Special thanks to eagle-eyed Paul Pereira.) That was out of 144 total entries from September 25 to now. There was plenty of other news to report. During all this, the MGM financial crisis was creeping toward its resolution, firm casting decisions were finally being announced, and the film finally got its greenlight. Whew!

For those who are interested in The Hobbit and the film industry in general but don’t want to slog through my blow-by-blow coverage, I’m offering a summary here, along with some thoughts on the implications of these events. Those who want the whole story can start with the link in the next paragraph and work your way forward. Obviously the links below don’t include all 110 entries.

In some cases the dates of my entries don’t mesh with those of the items I link to, given that New Zealand is one day ahead. I’ve indicated which side of the international dateline I’m talking about in cases where it matters.

September 25: Variety announces that the International Federation of Actors (an umbrella group of seven unions, including the Screen Actors Guild) is instructing its members not to accept roles in The Hobbit and to notify their union if they are offered one.

At that point, the film had not yet been greenlit, so it wasn’t clear how this would affect the production. The action against The Hobbit originated with the Australian union MEAA (Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance) and its director, Simon Whipp. Because relatively few actors in New Zealand are members of New Zealand Actors Equity, that small union is allied with the MEAA. The main goals of the union’s efforts were to secure residuals and job security for actors. The MEAA maintained that Ian McKellen (Gandalf), Cate Blanchett (Galadriel), and Hugo Weaving (Elrond) all supported the boycott; so far no evidence for this has been offered. Possibly they agreed to abide by it but were not in favor of it. Given the lack of a greenlight, none had been offered a role yet.

The main bone of contention has been a distinction made in labor laws in New Zealand. Actors are considered to be equivalent to contractors rather than employees, since they are hired on a temporary basis; it is illegal for a company to enter into negotiations with a union representing contractors. On that basis, Peter Jackson, who was first contacted in mid-August, refused to meet with the group. Besides, he isn’t the producer hiring the actors. Warner Bros., through New Line, is. As with all significant films, a separate production company, belonging to New Line, has been set up to make The Hobbit. It’s called 3 Foot 7. (The LOTR production company was 3 Foot 6, the average height of a hobbit being 3’6″.)

September 27. Peter Jackson responded angrily to the boycott, laying out the issues that would ultimately guide the New Zealand government’s response to the crisis:

“I can’t see beyond the ugly spectre of an Australian bully-boy using what he perceives as his weak Kiwi cousins to gain a foothold in this country’s film industry. They want greater  membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

“I feel growing anger at the way this tiny minority is endangering a project that hundreds of people have worked on over the last two years, and the thousands about to be employed for the next four years, [and] the hundreds of millions of Warner Brothers dollars that is about to be spent in our economy.”

Losing The Hobbit would leave New Zealand “humiliated on the world stage” and “Warners would take a financial hit that would cause other studios to steer clear of New Zealand”, Jackson said.

“If The Hobbit goes east [East Europe in fact], look forward to a long, dry, big-budget movie drought in this country. We have done better in recent years with attracting overseas movies and the Australians would like a greater slice of the pie, which begins with them using The Hobbit to gain control of our film industry.”

Various people and organizations in New Zealand soon line up behind one side or the other. Those siding with Jackson include Film New Zealand (which promotes filmmaking by foreign countries in New Zealand) and SPADA (the Screen Production and Development Association) and eventually the government. On the unions’ side is the Council of Trade Unions.

September 28. New Line, Warner Bros., and MGM weigh in with a statement that ups the ante. It dismisses the MEAA’s claims as “baseless and unfair to Peter Jackson” and continues:

To classify the production as “non-union” is inaccurate. The cast and crew are being engaged under collective bargaining agreements where applicable and we are mindful of the rights of those individuals pursuant to those agreements. And while we have previously worked with MEAA, an Australian union now seeking to represent actors in New Zealand, the fact remains that there cannot be any collective bargaining with MEAA on this New Zealand production, for to do so would expose the production to liability and sanctions under New Zealand law. This legal prohibition has been explained to MEAA. We are disappointed that MEAA has nonetheless continued to pursue this course of action.

Motion picture production requires the certainty that a production can reasonably proceed without disruption and it is our general policy to avoid filming in locations where there is potential for work force uncertainty or other forms of instability. As such, we are exploring all alternative options in order to protect our business interests.

Thus the specter of the production being not only delayed but also taken to another country is raised, and the implications of such a threat will gradually force the government to take measures to prevent that happening.

Peter Jackson also makes a statement to the Wellington newspaper that the Hobbit production might move to Eastern Europe. (The next day he reveals that WB is considering six countries for it.)

That night, a group of 200 actors met in Auckland, issuing a statement again asking the producers to meet for negotiations.

October 1. Jackson and WB voluntarily offer a form of residuals to Hobbit actors:

Sir Peter Jackson said New Zealand actors who did not belong to the United States-based Screen Actors’ Guild had never before received residuals – a form of profit participation. Warner Brothers had agreed to provide money for New Zealand actors to share in the proceeds from the Hobbit films.

It would be worth “very real money” to New Zealand actors. “We are proud that it’s being introduced on our movie. The level of residuals is better than a similar scheme in Canada, and is much the same as the UK residual scheme. It is not quite as much as the SAG rate.”

After much speculation, an announcement is made that Peter Jackson will definitely direct the film (which Guillermo del Toro had exited in May).

At about this time members of the filmmaking community begin campaigning actively against the boycott. An anti-boycott petition for New Zealand filmmakers and persons indirectly related to production to sign goes online; it ends with 3275 people having endorsed it.

October 15. The Hobbit is greenlit, but the possibility of moving the production out of New Zealand remains. Actors who have already been auditioned begin to be officially cast.

October 20. Actors Equity NZ is due to meet in Wellington. Richard Taylor (head of Weta Workshop) calls for a protest march. The actors’ meeting is called off due, the union says, to the “angry mob” that results. (Videos and photos posted online show a lengthy line of people walking through the streets in a peaceful fashion; that’s Richard talking to the press in the photo at the top. A person less likely to incite a “mob” to anger I cannot imagine.) An actors’ meeting scheduled for the next day in Auckland is also called off, putatively for the same reason, though no protest event had been planned there.

The turning-point day

October 21 (NZ). Jackson and his partner Fran Walsh issue a statement that implies that Warner Bros. has decided to move The Hobbit elsewhere:

“Next week Warners are coming down to New Zealand to make arrangements to move the production offshore. It appears we cannot make films in our own country even when substantial financing is available.”

Helen Kelly, president of the Council of Trade Unions calls Jackson “a spoiled little brat” on national television, helping turn the public against her cause.

Fran Walsh hints during a radio interview that WB might move The Hobbit to Pinewood Studios in England (where the Harry Potter films have been shot).

Prime Minister John Key says he hopes the production can be kept in New Zealand. Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee says he will meet with the WB delegation.

The international actors’ boycott against The Hobbit is called off.

October 21 (U.S.)/22 (NZ). WB is still considering moving the production, saying it has no guarantee that the actors will not go on strike. Key suggests that the labor law might be changed to provide that guarantee. The proposed legislation soon will become known as the “Hobbit bill.”

The Wall Street Journal suggests that a slight slip in the value of the New Zealand dollars against the American dollar is partly due to uncertainties about whether The Hobbit production will stay in the country.

WB announces the casting of Martin Freeman as Bilbo, plus several actors chosen as dwarves.

Bilbo Baggins by Tolkien and Martin Freeman, Bilbo-to-be.

A “positive rally” to convince WB to keep the production in New Zealand is announced. This eventually results in individual rallies in several cities and towns on October 25.

( U.S. time) Variety reports that unnamed sources within WB have said the studio is inclining toward keeping the production in New Zealand. This is the only hint of positive news from inside WB that comes out during the entire process.

Over the next few days, much finger-pointing takes place. Figures concerning the potential loss to NZ tourism if the film goes elsewhere are released. Helen Kelly apologizes for her “brat” remark.

October 25 (NZ). The WB delegation of 10 executives and lawyers arrive in Wellington. The pro-Hobbit rallies take place.

Pro-Hobbit rally in Wellington (Marty Melville/Getty Images).

October 26. News breaks that if The Hobbit is sent to another country, the post-production work (originally intended for Weta Digital and Park Road Post, companies belonging to Jackson and his colleagues) could take place outside New Zealand.

The WB delegation arrives at the prime minister’s residence in a fleet of silver BMWs. After the meeting ends, Key puts the chances of retaining the production at 50-50. He reiterates that the labor law might be changed.

Photo: NZPA

Presumably at this meeting, WB also puts forward a demand for higher tax rebates or other incentives; other countries it has been considering have more generous terms. Ireland has offered 28%, while New Zealand’s Large Budget Screen Production Grant scheme offers only 15%. This demand is not made public until later. During Key’s speech after the meeting, however, he mentions the possibility of higher incentives, but says the government cannot match 28%.

Editorials soon appear attacking the idea of changing a law at the behest of a foreign company.

The government’s deal with Warner Bros.

October 27. The New Zealand dollar again slips in relation to the American dollar, again attributed to uncertainty about The Hobbit.

Key and other government officials meet again with the WB delegation. The legal problem has been resolved to both sides’ satisfaction, but WB is holding out for higher incentives.

In the evening, Key announces that an agreement has been reached and the Hobbit production will stay in New Zealand:

As part of the deal to keep production of the “The Hobbit” in New Zealand, the government will introduce new legislation on Thursday to clarify the difference between an employee and a contractor, Mr. Key said during a news conference in Wellington, adding that the change would affect only the film industry.

In addition, Mr. Key said the country would offset $10 million of Warner’s marketing costs as the government agreed to a joint venture with the studio to promote New Zealand “on the world stage.”

He also announced an additional tax rebate for the films, saying Warner Brothers would be eligible for as much as $7.5 million extra per picture, depending on the success of the films. New Zealand already offers a 15 percent rebate on money spent on the production of major movies.

(The figure for the government’s contribution to marketing costs is later given as $13 million.)

October 28 (NZ). Peter Jackson returns to work on pre-production, which his spokesperson says has been delayed by five weeks as a result of the boycott. Principal photography is expected to begin in February, 2011, as had been announced when the film was greenlit. (The two parts are due out in December 2012 and December 2013.)

The Stone Street Studios. The huge soundstage built after LOTR is at the left; the former headquarters of 3 Foot 6 at the upper left.

In Parliament, a vote to rush through consideration of the “Hobbit bill” passes, and debate continues until 10 pm.

October 29 (NZ). The “Hobbit bill” passes in Parliament by a vote of 66 to 50, thus fulfilling the governments offer to WB and ensuring that The Hobbit would stay in New Zealand. It was known in advance that Key had enough votes going into the debate to carry the legislation.

It is revealed that James Cameron has been in talks with Weta to make the two sequels to Avatar in New Zealand. (Avatar itself was partly shot in New Zealand, with the bulk of the special effects being done there.) The timing has nothing to do with the Hobbit-boycott crisis. The two films are due to follow The Hobbit, with releases in December 2014 and December 2015.

October 30 (NZ). It is announced that the Hobbiton set on a farm outside Matamata will be built as a permanent fixture to act as a tourist attraction. (The same set, used for LOTR, was dismantled after filming, leaving only blank white facades where the hobbit-holes had been; nevertheless the farm has attracted thousands of tourists. See below.) Warner Bros. had been persuaded by the New Zealand government to permit this, though whether this was part of the agreement made with the studio’s delegation is not clear. I suspect it was.

It is also announced that the extended coverage of the 15% tax rebates specified in the “Hobbit bill” will apply to other films from abroad made in New Zealand—but only those with budgets of $150 million or more. (Presumably in New Zealand dollars.)

A remarkable outcome

In a way, it is amazing that a film production, even a huge one like The Hobbit, virtually guaranteed to be a pair of hits, could influence the law of a country–and make the legal process happen so quickly. Yet given the ways countries and even states within the USA compete with each other to offer monetary incentives to film productions, in another way it is intriguing that such pressure is not exercised by powerful studios more often. In most cases, a production company simply weighs the advantages and chooses a country to shoot in. Maybe countries get into bidding wars to lure productions or maybe they just submit their proposals and hope for the best. Certainly the six other countries considered briefly by WB were quick to jump in with information about what they could offer the Hobbit production.

In the case of Warner Bros. and The Hobbit, everyone initially assumed that the two parts would be filmed in New Zealand, just as LOTR had been. Yet the actors’ unions created an opportunity. The boycott gave Warner Bros. the excuse to threaten to pull the film out of New Zealand. Meeting with top government officials, WB executives demanded assurance that a strike would not occur–and oh, by the way, we need higher monetary incentives. As a result, a compromise was reached, the incentives were expanded, and there was a happy ending for the many hundreds of filmmakers of various stripes who would otherwise have been out of work.

Although there is considerable bitterness among the actors’ union members and those who supported their efforts, many in New Zealand see the tactics of the MEAA as extremely misguided. Kiwi Jonathan King, the director of the comic horror film Black Sheep, sums it up:

But this was all precipitated by an equal or greater attack on our sovereignty: an aggressive action by an Australian-based union taken in the name of a number of our local actors, backed by the international acting unions (but not supported by a majority of NZ film workers), targeting The Hobbit, but with a view to establishing a ’standard’ contract across our whole industry. While the actors’ ambitions may be reasonable (though I’m not convinced they are in our tiny market and in these times of an embattled film business), the tactic of trying to leverage an attack on this huge production at its most precarious point to gain advantage over an entire industry was grotesquely cynical and heavy-handed, and, as I say, driven out of Australia. Imagine SAG dictating to Canadian producers how they may or may not make Canadian films!

Whether the deal was unwisely caused by a pushy Australian union is a matter for debate. Whether the New Zealand government unreasonably bowed down to a big American studio is as well. But the deal that the two parties reached is a remarkable one, perhaps indicative of the way the film industry works in this day of global filmmaking.

Warner Bros. gets more money and a more stable labor situation. What’s in it for New Zealand? First, the incentives for large-budget films from abroad to be made in the country are raised. This comes not through an increase in the tax-rebate rate but an expansion of what it covers:

The Government revealed this week that the new rules would mean up to $20 million in extra money for Warner Bros via tax rebates, on top of the estimated $50 million to $60 million under the old rules.

While the details of the Large Budget Screen Production Grant remain under wraps, Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee said it would effectively increase the incentives for large productions to come to New Zealand.

The grant is a 15 per cent tax rebate available on eligible domestic spending. At the moment a production could claim the rebate on screen development and pre-production spending, or post-production and visual effects spending, but not both.

If the Government allowed both aspects to be eligible, it would be a large carrot to dangle in front of movie studios.

Mr Brownlee was giving little away yesterday but said the broader rules would apply only to productions worth more than US$150 million ($200 million).

It would bridge the gap “in a small way” between what New Zealand offered and what other countries could offer.

During this period, it was claimed that WB had already spent around $100 million on pre-production on The Hobbit, which has been going on for well over a year now. That figure presumably is in New Zealand currency.

There are some in New Zealand who oppose “taxpayer dollars” going to Warner Bros. As has been pointed out–though apparently not absorbed by a lot of people–Warner Bros. will spend a lot of money in New Zealand and get some of it back. The money wouldn’t be in the government’s coffers if the film weren’t made in the country. It’s not tax-payers’ money that could somehow be spent on something else if the production went abroad.

Another advantage for the country is the permanent Hobbiton set, which will no doubt increase tourism. There are fans who have already taken two or three tours of LOTR locations and will no doubt start saving up to take another.

One item that didn’t get noticed much during the deluge of news is that one of the two parts will have its world premiere in New Zealand. That’ll probably happen in the wonderful and historic Embassy theater, which was refurbished for the world premiere of The Return of the King. It was estimated that the influx of tourists and journalists for that event brought NZ$7 million to the city of Wellington. About $25 million in free publicity was provided by the international media coverage.

The Embassy in October 2003, being prepared for the Return of the King world premiere.

The deal also essentially makes the government of New Zealand into a brand partner with New Line to provide mutual publicity for The Hobbit. As I describe in Chapter 10 of The Frodo Franchise, the government used LOTR to “rebrand” the entire country. It worked spectacularly well and had a ripple effect through many sectors of society outside filmmaking. The country came to be known more for its beauty, its creativity, and its technical innovations than for its 40 million sheep. Now in the deal over The Hobbit, the government has committed to providing NZ$13 million for WB’s publicity campaign. But the money will also go to draw business and tourists. As TVNZ reported:

But the Prime Minister says for the other $13 million in marketing subsidies, the country’s tourism industry gets plenty in return.

“Warner Brothers has never done this before so they were reluctant participants, but we argued strongly,” Key said.

Every DVD and download of The Hobbit will also feature a Jackson-directed video promoting New Zealand as a tourist and filmmaking destination.

Graeme Mason of the New Zealand Film Commission says the promotional video will be invaluable.

“As someone who’s worked internationally for most of my life, you can’t quantify how much that is worth. That’s advertising you simply could not buy.”

If the first Hobbit film is as popular as the last Lord of the Rings movie, the promotional video could feature on 50 million DVDs.

Suzanne Carter of Tourism New Zealand agrees having The Hobbit production here is a dream come true.

“The opportunity to showcase New Zealand internationally both on the screen and now in living rooms around the world is a dream come true,” Carter said.

Marketing expert Paul Sinclair says the $13 million subsidy works out at 26 cents a DVD.

“It’s a bargain. It is gold literally for New Zealand, for brand New Zealand,” he said.

It’s not clear how the promotional partnership will be handled. There was a similar, if smaller partnership when LOTR was made. New Line permitted Investment New Zealand, Tourism New Zealand, the New Zealand Film Commission, and Film New Zealand to use the phrase, “New Zealand, Home of Middle-earth” without paying a licensing fee. (Air New Zealand was an actual brand partner during the LOTR years.) But for the government to actually underwrite the studio’s promotional campaign may entail more. That deal is more like the traditional brand partnership, where the partner agrees to pay for a certain amount of publicity costs in exchange for the right to use motifs from the film in its advertising. Has a whole country ever brand-partnered a film? I can’t think of one.

In my book I wrote that LOTR “can fairly claim to be one of the most historically significant films ever made.” That’s partly why I wrote the book, to trace its influences in almost every aspect of film making, marketing, and merchandising–as well as its impact on the tiny New Zealand film industry that existed before the trilogy came there. Years later, I still think that my claim about the trilogy’s influences was right. When an obscure art film from Chile or Iran carries a credit for digital color grading, it shows that the procedure, pioneered for LOTR, has become nearly ubiquitous. There are many other examples. The troubled lead-up to The Hobbit‘s production and the solutions found to its problems suggest that it will carry on in its predecessor’s fashion, having long-term consequences beyond boosting Warner Bros.’ bottom line. It will be interesting to see if other big studios announce they will film in one country and then find ways of maneuvering better terms by threatening to leave–or by actually leaving.

From Worldwide Hippies

The buddy system

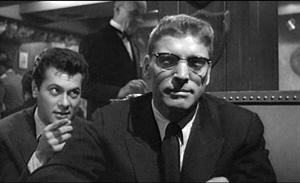

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

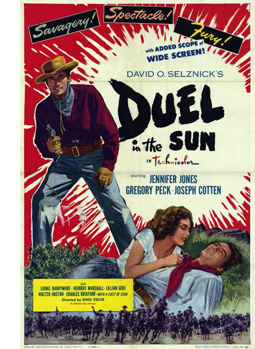

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

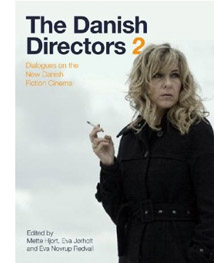

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.