Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

What makes Hollywood run?

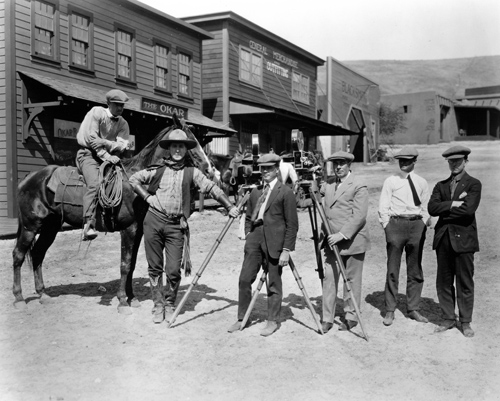

William S. Hart and crew at Inceville, 1910s.

DB here:

For decades most people had a sketchy idea of The Hollywood Studio Film. Boy meets girl, glamorous close-ups, spectacular dance numbers or battle scenes, happy endings, fade-out on the clinch. But even if such clichés were accurate, they didn’t cut very deep or capture a lot of other things about the movies. Could we go farther and, suspending judgments pro or con the Dream Factory, characterize U. S. studio filmmaking as an artistic tradition worth studying in depth? Could we explain how it came to be a distinctive tradition, and how that tradition was maintained?

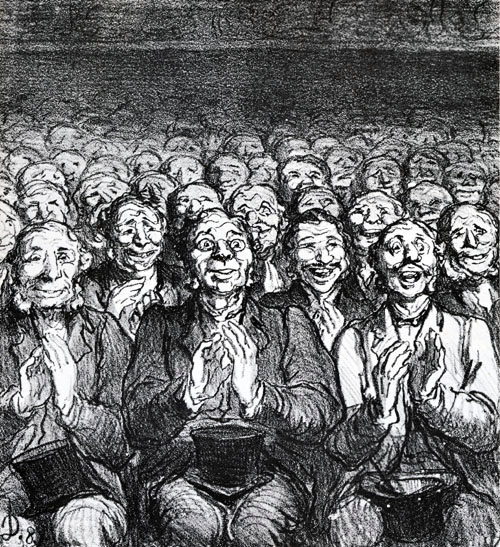

In 1985 Routledge and Kegan Paul of London published The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote it. Since it’s rare for an academic film book to remain in print for twenty-five years, we thought we’d take the occasion of its anniversary to think about it again. Those thoughts can be found in the adjacent web essay, where we three discuss what we tried to do in the book, spiced with comments about areas of disagreement and more recent thoughts. This blog entry is just a teaser.

A touch of classical

John Arnold, a Bell & Howell camera, and Renée Adorée in 1927.

The prospect of analyzing Hollywood as offering a distinctive approach to cinematic storytelling emerged slowly. The earliest generations of film historians tended to talk about the emergence of film techniques in a rather general way. For example, historians were likely to trace the development of editing as a general expressive resource, appearing in all sorts of movies. While they recognized that, say, the Soviet filmmakers made unusual uses of this technique, writers still tended to think of editing as either a fundamental film technique or a very specific one—e.g., Eisenstein’s personal approach to editing.

An alternative approach was to understand the history of film as an art as a stream of cinematic traditions, or modes of representation, within which filmmakers worked. From this angle, there was a Hollywood or “standard” or “mainstream” conception of editing, and this didn’t exhaust all the creative possibilities of the technique. But it went beyond the inclinations of any particular director. People had long recognized that there were group styles, like German Expressionism and Italian Neorealism, but it took longer to start to think of mainstream moviemaking as, in a sense, a very broad and fairly diverse group style.

In the late 1940s André Bazin and his contemporaries started to point out that different sorts of films had standardized their forms and styles quite considerably. Bazin attributed the success of Hollywood cinema to what he called “the genius of the system.” In my view, his phrase referred not to the studio system as a business enterprise but rather to an artistic tradition based on solid genres and a standardized approach to cinematic narration. This artistic system, he suggested, had influenced other cinemas, creating a sort of international film language.

The idea that there was a dominant filmmaking style, tied to American studio moviemaking, was developed in more depth during the 1960s and 1970s. Christian Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film pointed toward alternative technical choices available in the “ordinary film.” Raymond Bellour’s analysis of The Birds, The Big Sleep, and other films pointed to a fundamental dynamic of repetition and difference governing American studio cinema. Somewhat in the manner of Roland Barthes’ S/z, Thierry Kuntzel’s essays explored M and The Most Dangerous Game looking for underlying representational processes that were characteristic of studio films. From a somewhat different angle, in the book Praxis du cinema and later essays Noël Burch traced out a dominant set of techniques that formed what he would eventually call the “Institutional Mode of Representation.” The Cahiers du cinéma critics famously posited different categories of filmic construction, each one tied to the representation of ideology. In English, Raymond Durgnat was an early advocate of studying what he called the “ancienne vague,” the conventional filmmaking that young directors were rebelling against.

The trend was given a new thrust by the British journal Screen, which disseminated the idea of a “classical narrative cinema,” a mode of representation characterized by distinctive dynamics of story, style, and ideology. Perhaps the most emblematic article of this sort was Stephen Heath’s in-depth analysis of Touch of Evil. Over the same years a new generation of film historians was studying early cinema with unprecedented care, and they too were finding a variety of modes of representation at work in filmmaking of the pre-1920 era.

The effect was to relativize our understanding of Hollywood. Mainstream U. S. commercial filmmaking wasn’t the cinema, merely one branch of film history, one way of making movies. Breaking a scene into a coherent set of shots, to take the earlier example, wasn’t Editing as such. It was one creative choice, although it had become the dominant one. And what made Hollywood’s brand of coherence the only option? Eisenstein, Resnais, Godard, and other filmmakers explored unorthodox alternatives.

Nearly all of the influential research programs of the period emphasized the film as a “text.” This wasn’t surprising, since several of the writers were working with concepts derived from literary semiotics and structuralism. At the same period, other scholars were developing ideas about Hollywood as a business enterprise. Douglas Gomery, Tino Balio, and a few others were showing that the studio system was just that—a system of industrial practices with its own strategies of organization and conduct. But most of those business studies did not touch on the way the movies looked and sounded, or the way they told their stories.

Could the two strains of research be integrated? Could one go more deeply into the films and extract some pervasive principles of construction? And could one go beyond the films and show how those principles of style and story connected to the film industry?

The prospect of integrating these various aspects—and, naturally, of finding out new things—intrigued us.

Secrets of the system

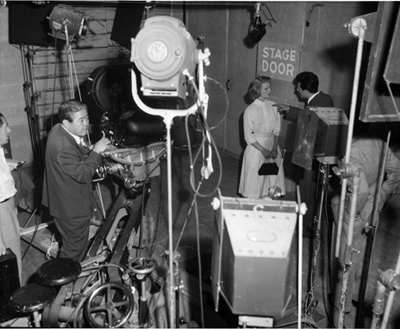

Main Street to Broadway (1953, MGM release). Cinematographer James Wong Howe on left.

The overall layout of CHC tried to answer these questions while weaving together a historical overview. Part One, written by me, provided a model or ideal type of a classical film, in its narrative and stylistic construction. Part Two, by Janet, outlined the development of the Hollywood mode of production until 1930. In Park Three, Kristin traced the origins and crystallization of the style, from 1909 to 1928. Part Four included chapters by all three authors on the role of technology in standardizing and altering classical procedures during the silent and early sound era. In Part Five Janet resumed her account of the mode of production, tracing changes from 1930 to 1960. The technology thread was brought up to date in Part Six, where I discussed deep-focus cinematography, Technicolor, and the emergence of widescreen cinema. Part seven, which Janet and I wrote together, pointed out implications of the study and suggested how Hollywood compared with alternative modes of film practice.

Clearly, CHC was several books in one. Janet could easily have written a free-standing account of the mode of production. Kristin could have done a book on silent film technique and technology. I could have focused on style and form, using sound-era technologies as test cases. The point of interspersing all these studies (and creating a slightly cumbersome string of authorial tags within sections) was to trace interdependences. For instance, Kristin examined the emerging stylistic standardization in the 1910s. Janet showed how that standardization was facilitated by a systematic division of labor and hierarchy of control, centered around the continuity script. At the same time, the organization of work was designed to permit novelties in the finished product, a process of differentiation that is important in any entertainment business.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

In the late 1920s, for instance, sound recording made the camera heavier than the tripods of the silent era could bear. Supply firms engineered “camera carriages” that could wheel the beast from setup to setup. But this development occurred soon after filmmakers had noticed the expressive advantages of the “unleashed camera” in German films and some American ones. So the camera carriage became a dolly, redesigned to permit moving the camera while filming. It’s not that there weren’t moving-camera shots before, of course, but with the camera permanently on a mobile base, tracking and reframing shots could play a bigger role in a scene’s visual texture. Similarly, studio demands for ways of representing actors’ faces in close-ups forced Technicolor engineers back to their drawing boards again and again. Once the problem of rendering faces pleasant in color was solved, filmmakers could then redesign their sets and adjust their make-up to suit the vibrant three-strip process. And the interaction of work, tools, and style triggered larger cycles of activity. The need to pool information about stylistic demands and technological possibilities helped foster the growth of professional associations and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This give-and-take among the studios, the supply sector, and the stylistic norms had never been discussed before, and we couldn’t have done justice to it in separately published books. Nor could isolated studies have easily traced how industrial discourses—the articles in trade journals, the communication among the major players—helped weld the mode of production to artistic choices about filmic storytelling.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema was generously reviewed, in terms that made us feel our hard work had been worth it. Books we’ve written since haven’t been so widely acclaimed. (Nothing like peaking young.) We’re grateful to the reviewers who praised the book, and to the teachers and students who have strengthened their biceps by picking it up to read. Of course there are others who don’t consider the project worthwhile; the TLS reviewer called it “sludge.” Probably nothing we say in the accompanying essay will persuade those readers to take a second look. Without responding to all the criticisms the book received (that would take a book in itself), our accompanying essay tries to position this 1985 project within our current lines of thinking.

We studied how Hollywood routinized its work, but that doesn’t mean that we think division of labor is always alienating. It may produce a much better outcome than do the efforts of a solitary individual. For us, that’s what happened during this rewarding exercise in collaboration.

Our thinking was shaped by many sources; here are some of them.

For André Bazin on “the genius of the system,” see “La Politique des auteurs,” in The New Wave, ed. Peter Graham (New York: Doubleday, 1968), pp. 143, 154, and “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), pp. 23-40. Christian Metz explains the Grande Syntagmatique of the image track in “Problems of Denotation in the Fiction Film,” Film Language, trans. Michael Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 108-146. Raymond Bellour’s essays of the period are available in The Analysis of Film. Thierry Kuntzel’s essay on The Most Dangerous Game was translated into English as “The Film-Work 2,” Camera Obscura no. 5 (1980), 7-68. An important gathering of essays in this line of inquiry is Dominique Noguez, ed., Cinéma: Théorie, lectures (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973).

Noël Burch’s early ideas are set out in Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane (New York: Prager, 1973). Even more important to our project was Noël Burch and Jorge Dana, “Propositions,” Afterimage no. 5 (Spring 1974), 40-66, and Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film (London: Scolar Press, 1979), available online here.

Raymond Durgnat’s series, “Images of the Mind,” deserves to be republished, preferably online. The most relevant installments for this entry are “Throwaway Movies,” Films and Filming 14, 10 (July 1968), 5-10; “Part Two,” Films and Filming 14, 11 (August 1968), 13-17; and “The Impossible Takes a Little Longer,” Films and Filming 14, 12 September 1968), 13-16. Stephen Heath’s analysis of Touch of Evil may be found in “Film and System: Terms of Analysis,” Screen 16, 1 (Spring 1975), 91-113 and 16, 2 (Summer 1975), 91-113.

Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983) works in comparable areas to CHC, though without our interest in industry-based sources of stability and change. The newest edition is here.

Tino Balio’s courses and his collection The American Film Industry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) had a substantial influence on us. He has been a wonderful friend and guide for us all since the 1970s. Our friendship with Douglas Gomery dates from our early days in Madison. Many conversations, along with his teaching in our program, shaped our thinking. A good summing up his of decades of work on the business and economics of Hollywood is The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

Some of the stylistic traditions discussed in this entry are discussed in my On the History of Film Style. Several blog entries on this site fill in more details; click on the category “Hollywood: Artistic traditions.”

PS 26 September 2010: Douglas Gomery reminds me that the idea of sampling Hollywood films in an unbiased fashion–one feature of our method in CHC–was suggested to us by Marilyn Moon, economist extraordinaire. I’m happy to thank Marilyn, along with Joanne Cantor and Douglas himself, who helped us devise a sampling procedure.

Actors and set for Blondie Johnson (Warners, 1933).

Festival as repertory

DB here:

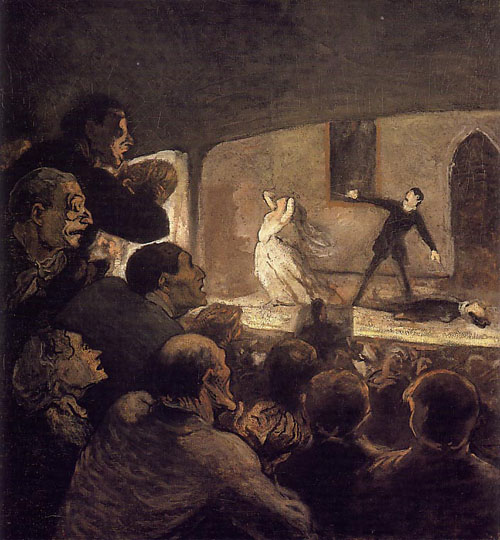

This picture points backward and forward. It looks back to the days when movies were shown on a big screen to hundreds of people in real time. No pausing or fast forwarding; you take what you get. Some viewers are settled in pretty close to the screen, and a few dare to sit in the front row. (Save me the center seat, fortunately still vacant.) The critic sits slumped far back, implying coolly distant appraisal. The pen is poised to note down moments of power, beauty, or stupidity.

But the big auditorium is nearly empty, and this makes the drawing foreshadow the approaching end of moviegoing. The warning signs are emerging: Visit any movie, even an Imax spectacular, in the off-hours (Monday through Wednesday, especially matinees) and you’re likely to find the house as empty as it is here. As for the critic, ready to jot down notes for a review: An anachronism these days, as many will tell you.

But wait. Isn’t the theatrical business booming? We’re told that 2009 was a banner year, and 2010 will be even better. True, worldwide admissions for 2009 totaled $29.9 billion, a new high. But the increase, according to the MPAA, is mostly due to 3D. In the US, the format accounted for 11 % of the country’s $10.6 billion box-office income, a sum about equal to the gain over last year’s take. Moreover, the number of domestic tickets sold increased only a little from recent years, to 1.4 billion. Overall, the years 2005-2009 have fallen off from the high points of 2002-2004, when attendance was 1.5 billion or more.

Nor is the international film industry expanding its audience. For the last five years or so, worldwide attendance has been remarkably flat, with only the Asia-Pacific region seeing signs of growth. Overall, it seems, 3D serves to let Hollywood hang on to its audience, and charge more.

The spurt in theatrical income helps offset the decline of packaged media. The DVD sell-through boom lasted from 1998 to about 2008, when subscription rental companies (Netflix, Lovefilm) and kiosks (Redbox et al) pushed down retail sales. The slump was accelerated by a glut of DVD releases, big-box stores offering discs at rock-bottom prices, the rise of downloading and video on demand, and, not least, a massive recession that made consumers cost-conscious. Today, many industry observers think that young people are more inclined to graze in the luxuriance of YouTube than visit the multiplex. At best, the Millennials might watch a current hit streaming on their cellphones or laptops or TV monitor. An admittedly small-scale inquiry in the recent Screen Digest (April, p. 100; here, but proprietary) suggests that most young entertainment fans don’t feel a need to rent a disc, let alone buy one. Moreover, all those sampled saw far more movies on monitors, often through shady downloads, than on theatre screens.

It’s not hard to imagine a near future when a movie opens simultaneously on the global market to satisfy its most devoted public before moving in a very few weeks to DVD, VOD, iTunes, and other digital platforms. It then snuggles into hundreds of thousands of hard drives around the world, ready to be awakened when somebody feels the urge to watch. These seem to be the two poles we’re moving toward: the brief big-screen shotgun blast, and the limbo of everlasting virtual access. You can argue that the very success of home video, cable, and the internet have cheapened our sense of a movie’s identity.

Which is one reason why film festivals are very, very important.

Apocalypse then and now

I’ve spent most of the last several weeks at festivals. The Hong Kong International Film Festival is a 2 1/2 week showcase of global cinema, attached to a major regional market assembly and spiced with local attractions and international retrospectives. The Wisconsin Film Festival is a 4 1/2 day local event highlighting US independent cinema but with a leavening of recent arthouse titles and restored classics. Ebertfest, formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked Films, is a topical festival held in a single venue, featuring a wide array of guests, and reflecting its founder’s eclectic tastes.

Each offers unique pleasures, and each reaffirms the value of the theatrical motion-picture experience. I’ve already written a bit about Hong Kong here and here and here, and I hope to write more about the Wisconsin event soon. For now I’ll concentrate on a few high points of Ebertfest, which took Roger’s cartoon above as its emblem. Kristin and I have been guests for many years (our posts are in the Festivals: Ebertfest category on the right), but this time she was in Egypt scouring the sands for pieces of statues. So I’ve had to blog solo.

Fortunately, we now have a vast archive of what happened in Urbana. With the generosity typical of Roger’s event, all the Q & A sessions and panel discussions were recorded and streamed. They’re available here. And for an appreciative account of what it all means, see Jim Emerson’s piece on Roger’s site.

Start with the obvious. Apocalypse Now Redux was shown in a Technicolor restoration in the Virginia Theatre, a picture palace built in 1926. The image loomed, the sound engulfed you. Several people, most of them young, told me that they felt privileged to have seen the film, for once in their lives, as it must be seen. As soon as you get a home theatre that matches this presentation in sheer primal impact, call me. I’m coming over.

Editor and sound designer Walter Murch, one of my heroes, was prevented from coming by the European volcano ash. So I tried in my introduction to pay homage to what is surely one of the most complex soundtracks of any film of the period—a mixture of synthesizer, rock and roll, and layer upon layer of subtly enhanced noises. During the screening I was able to appreciate some of the daring soundfields Murch created. When Willard gets up to look out the blinds of his Saigon hotel, the sound in the left and right and surround channels narrows abruptly to the central speaker, bringing him back to mundane R & R reality. Later, most ordinary dialogue comes from the central speaker, but when Willard voices his commentary, we hear him from all three front speakers; the soft tone creates an intimacy, while the auditory spread gives it weight and authority.

A panel of commentators including Ali Arikan, Michael Phillips, and Janet Pierson did a fine job of probing various aspects of the film. Ali considers it Coppola’s crowning achievement and one of the great American films. Michael, by contrast, thought that what he aptly called the “terror and grandeur” of its opening half gives way to off-kilter and pretentious scenes in Kurtz’s compound. Janet, who had seen the film on the big screen more often than any of us, found it an enduringly impressive accomplishment in both sound and image. With the audience we had a lively exchange about the role of women in the film and the inclusion of the notorious French plantation sequence. Matt Zoller Seitz made a shrewd point about how the film shows Americans bringing along homegrown entertainments (Playmate performances, rock music, surfing) to redefine the war in familiar terms.

Despite all the shock and awe, I like the film only moderately. It’s a stunning logistical accomplishment, and it has some brilliant moments; but I think it has problems almost as soon as Willard moves upriver. I might be the only person who finds the Kilgore scenes overdrawn, almost Dr. Strangeloveish. When Kurtz bends down to give water to the wounded Vietnamese, he’s interrupted by news of surfing, and he yanks his canteen away as the VC scrabbles for it.

Heavy, heavy—as is the repeated motif of Americans strafing civilians and then tending to their wounds. Willard spells it out: “We cut them in half and then give them a Band-Aid.” Yet I still admire the utterly disorienting opening, which mixes thrumming choppers with ceiling fans and justifies what Michael Herr called it: the rock-and-roll war. Later we’ll see battles wreathed in psychedelic haze, and a hallucinatory assault on the bridge, with Willard stumbling through the dark and watching battle-fried infantrymen hurl ordnance into a void. It’s like a light show at the climax of a rock concert.

One of my favorite comments about the movie came during Dick Cavett’s television show circa 1980. Dick asked Jean-Luc Godard what he thought of Apocalypse Now. This was a period in which most of the press coverage obsessed about the film’s soaring budget. Godard remarked that Coppola had not spent enough. Cavett asked for an explanation. Godard: “Well, he spent only fifty million dollars and the war cost fifty billion. You cannot film this war on such a small budget.” That’s the way I remember it, anyhow.

From Rwanda to LA

Quick notes on two other E’fest titles. (I’ve already discussed Departures here.)

“I wanted to make a film for a Rwandan audience.” Not what you might expect to hear from an American director of Korean descent. Accordingly, Lee Isaac Chung gave Munyurangabo a leisurely pace and structure. The plot centers on two young men, Sangwa and Munyurangabo (aka Ngabo), taking what seems to be an enigmatic journey. One is Hutu, the other Tutsi. Longish takes and fairly distant framings follow them hitchhiking and stopping over at Sangwa’s home. Gradually, hints such as Ngabo’s carefully wrapped machete suggest that they are heading toward a confrontation. When the revelation comes, our attachment shifts from Sangwa and his family conflicts to Ngabo’s mission of vengeance. Chung explained that the soundtrack develops accordingly, moving from objectivity to subjectivity as we start to hear what his two protagonists hear.

The production background, explained by Chung and his colleagues Sam Anderson (co-writer and producer) and Jenny Lund (co-producer and sound recordist), was fascinating. The script consisted largely of a scene outline, and the dialogue was developed with the actors. The Americans worked with translators in guiding the performances. In some cases they drew on their own experiences. Perhaps partly because of its respect for everyday life, the film has been shown on local television and in the Parliament. It has become a Rwandan film.

My colleague J. J. Murphy has written an acute analysis of Munyurangabo. He rightly praises the sudden entrance of a bardic young man who recites a six-minute poem celebrating liberation and reconciliation. The performance wasn’t planned, Chung said, but it has become a high point of the film. J. J. also links to other enlightening interviews given by Chung, Anderson, and Lund.

If Munyurangabo’s loose structure evokes the Dardennes brothers, Michael Tolkin’s The New Age has the coiled-serpent dramaturgy of a classic psychodrama-comedy. It’s 1994, and a prosperous LA couple is suddenly without income. Facing bankruptcy, Katherine and Peter auction off their paintings, try to borrow from Peter’s father, and eventually open a boutique catering to the tastes of their friends. At the same time they slide into casual affairs and ceremonies of New Age spirituality. Ebert’s review captures the movie’s range of reference:

Tolkin gives us one richly detailed set piece after another, involving luncheons, openings, massages, telephone tag, psychic consultations, sex, heartfelt conversation, and pagan rituals led by a bald-headed woman who sees what others cannot see. Meanwhile, the material universe remains the one thing Peter and Katherine can really count on.

Few American films examine money and class, but this one is actually about needing a paycheck. By the end, when each of our protagonists becomes a seller rather than a buyer, we have seen a remarkably sharp dissection of a lifestyle.

In the Q & A afterward, Tolkin said that the genesis of the film came from watching a Melrose shop sink into failure. When I saw the film on its initial release, lines like “It’s not an insult, it’s an intervention” and “We need space” (psychological, but also retail) leaned me toward taking the film as satire. I still do. But Tolkin insists that it’s not. The plot dares to have two truly repellant protagonists, but Tolkin doesn’t find them nasty. “I like them.” He majored in religion in college and he takes his characters’ beliefs, no matter how shallow, seriously—not a big surprise from the creator of The Rapture.

He elaborated on some differences between novels and films. When he rereads one of his novels, he thinks, “How was I ever that smart?” but when he rewatches a film it’s the imperfections that jump out. A movie has to be more compressed and rhythmically varied than a novel—something The New Age demonstrates in its brisk montages alternating with slowly unfolding scenes. In the discussion Jim Emerson praised the film’s density of detail, Tolkin elaborated by invoking William Carlos Williams’ belief in compact expression.

The next two paragraphs include plot details you may prefer to pass over.

Tolkin’s script is indeed firmly contoured. The couple’s crucial quarrel takes place at the thirty-minute mark and launches the two major plot lines. They decide to try a separation (while sharing the house), and they launch their boutique. The development section begins about halfway through, as they conduct their love affairs and watch the shop founder. The last act presents their options: bankruptcy, suicide, low-end work.

Arguably the climax is Peter’s desperate effort to make his first telemarketing sale. Here, I think, Tolkin’s ambivalent sympathies come out. Early in the film Peter had asked a cold-caller whether he ever thought he’d be doing this as a career; it’s less a moral condemnation than glib snobbery. But when Peter has to close the sale, his self-loathing is mixed with a certain pride. The cashiered ad exec finds that he can do this. He’s on the road back.

The gorgeously designed movie, with hard blacks and saturated primaries, has a developing palette (“swatches for each act,” Tolkin says). Unhappily, I can’t study the design arc here because The New Age seems never to have had a DVD release. So much for the Celestial Multiplex. Good old 35mm pulled us through, in a radiant print.

Scholars seem now to agree that film festivals serve as an alternative international distribution system. Like Hollywood’s more formal and routinized machine, festivals bring movies to audiences. Usually the movies are current ones, and a festival is offering local viewers their only chance to see such pictures before video release.

Ebertfest shows that there’s an essential place for what we might call the repertory festival. That’s one that revives and reappraises films from earlier periods—and “earlier” may mean only a few years ago. Jumping from 1929 (Man with a Movie Camera, accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra) to the 1980s (Apocalypse Now, Barfly) and the 1990s (The New Age) and then right up to 2008 (Vincent, Trucker, Departures, Synecdoche, New York, Song Sung Blue), this year’s edition reminds us that every film, old or new, is a part of history.

To come fully into history, I’m convinced, a film needs scale. Even intimate dramas attain their true gravity when spread out like a gigantic picnic on a pale blanket. It’s not the only way to enjoy cinema, certainly; but it’s one that we must never abandon. Like the note-taker in the back row and the geeks up front, everyone needs a full view.

Apocalypse Now Redux.

PS 28 April: I just discovered this piece by Steven Zeitchik, who argues that reviving classics in a big-screen event format could also be good business.

Film criticism: Always declining, never quite falling

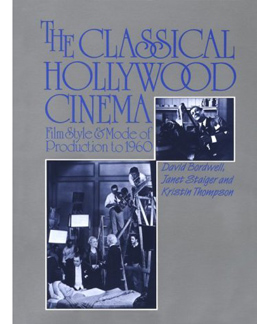

Daumier, Le mélodrame (1860-64)

DB here:

Before the Internets, did people fret as much about movie criticism as they do now? The dialogue has become as predictable as a minuet at Versailles.

Film criticism is dead.

No, it’s not! It’s alive and well on the Web.

Hah! Call that criticism? Nobody can be a movie critic unless they (a) write for print publication; (b) have been doing it for x years; (c) are a member of a critics’ professional society; and/ or (d) get paid for it.

Well, the track record of the official movie critics isn’t that great. Most of their writings are forgotten the minute they’re published.

Infinitely more awful is what you read on the Net. At least print critics kept up standards; there were gatekeepers (also called editors) and a literate public.

The result being….? When has a print critic of recent years equaled the greats of the past—Agee, Farber, Sarris, Kael?

Same thing goes for the Net. Blogs and websites don’t show me anything like that level of achievement. What I see is amateur hour.

Yeah? Well, bloggers and netwriters have passion!

But not a passion for using Spellcheck.

So if print criticism is so valuable, how come all those professional critics are getting fired?

Film criticism is dead.

Repeat as often as you like.

I thought I had watched this rondelay often enough from the wallflower section, but I got dragged onto the dance floor by Tom Doherty. In his piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Tom offered another eulogy for serious film criticism. Dead again, as Jim Emerson notes; killed by those wretched netizens.

To watch their backs and retain their 401(k)’s, most print critics have been forced into sleeping with the enemy. As a form of ancillary outreach, blogs, podcasts, and chat-room discussions have become a required part of the job description for print reviewers. Or maybe the print part of the gig is now the ancillary outreach.

Feeling the same heat, academic critics have also plunged into the brash new world. The film-studies panjandrum David Bordwell—think Knowles with chops in postmodern theory—runs one of the most closely watched blogs at David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema (http://davidbordwell.net/blog). The impact of the academic bloggers on Hollywood’s box-office gross is negligible (sorry, David), but the online work of the digital hordes is already making a substantial contribution to film scholarship—in the spirited parry and thrust of the dialogues, in the instant retrieval of past research, and in the factoid jackpots provided by the film databases.

I’m sure Tom means to be complimentary, but just to get mundane: No heat forced Kristin and me to the Web. I set up a bare-bones site in 2000, including a vitae and a statement about what studying film meant to me, because people were sometimes writing me asking for such information. Then, inspired by Philip Steadman’s stylish site extending the arguments in his book Vermeer’s Camera, I used mine to supplement my books, putting in corrections, second thoughts, and pictures. Then I began to write longish essays that build on things in the books.

When I retired in 2006, Kristin and I decided to recast the site as a supplement to our best-known book, Film Art: An Introduction. Our publisher McGraw-Hill funded an upgrade. But our efforts quickly went beyond spinning off the textbook. We treated Observations as our own magazine, with no pesky editors to tell us that a piece was too long or had too many stills. It offered a way to get our ideas out to a new audience, or maybe a bigger one. Just as important, after years spent writing books, I enjoy the recreation of writing shorter pieces. When you’re 62, sprints look better than marathons. Actually, because I’m a compulsive overwriter, some of my blog-sprints are like marathons.

Unhappily, none of this enhanced our 401(k)s.

Some other quibbles: Tom intended “panjandrum” as praise, but as many friends have pointed out, I’m probably the last person you’d associate with PoMo. I’m stuck in pre-post-modernism. Still, Tom is right on one point. My efforts to erode the box-office takings of Babel, The Departed, and The Dark Knight failed utterly. On the other hand, I may have considerably boosted Cloverfield’s first-dollar gross.

Nothing if not critical

Daumier, Les critiques (1862)

Tom’s piece, its place of publication, the comments on it, and his reply to those comments invite me to revive some points I made around this season in 2008 and 2009. (Is it a rite of spring?)

Film criticism takes many forms. Tom identifies criticism with being paid to review movies that have just come out. This is a form of arts journalism, and like all journalism it is being squeezed by the decline in advertising revenue. So yes, print-based paid reviewing is waning.

But criticism includes more activities than rapid-response reviewing. It includes what we might call haute journalism, as practiced in literary quarterlies, film magazines like Cineaste and Cinema Scope, and even occasionally in the New York Review of Books (which just got around to noticing Sokurov’s 2005 The Sun). There’s also reseach-based criticism, published in specialized venues like Cinema Journal and in semi-specialized journals like Film Quarterly (which seems to be moving toward haute journalism). And of course academics have written whole volumes of film criticism—through-composed books, not collections of published reviews.

Each of these modes of criticism has its own conventions. I try to characterize them here. I think Tom should have made some of these distinctions, because it doesn’t help film culture to encourage readers of the Chronicle to limit their conception of criticism to what they get in The New Yorker or Salon.

Insofar as we think of criticism as evaluation, we need to distinguish between taste (preferences, educated or not) and criteria for excellence. I may like a film a lot, but that doesn’t make it good. For arguments, go here again. Criteria are intersubjective standards that we can discuss; taste is what you feel in your bones. A critical piece that merits serious thinking tends to appeal to criteria that readers can recognize, and dispute if they choose.

Enough with the love, already. My only real quarrel with Gerry Peary’s film For the Love of Movies is that it seems to place “love of cinema” at the center of the critical activity. But everybody loves film. The real question is: What does this love lead to? Gossip? Infighting and insults? A desire to take chances and watch films you might hate? A desire to stretch and nuance one’s viewing? An urge to learn something subtle about cinema more generally?

Opinions need balancing with information and ideas. The best critics wear their knowledge lightly, but it’s there. To be able to compare films delicately, to trace their historical antecedents, to explain the creative craft of cinema to non-specialists: the critical essay is an ideal vehicle for such information. The critic is, in this respect, a teacher.

Which means that the critic traffics in ideas too. A critic of lasting value offers a vision of cinema, of the arts more generally, of society or politics or something beyond the individual movie. For Sarris, the key idea was directorial authorship. For Parker Tyler, it was the idea that popular culture spasmodically threw up surrealistic material. For Farber it was the prospect that the studio system nurtured films, or moments, that hinted at speed, harshness, and darkness. Sontag clung to the hope that cinema could carry on the program of post-World-War-II modernism. For Ebert, what seems central is the belief that cinema can yield humane wisdom that forms a guide for living. Beyond our shores there were Arnheim, Bazin, Eisenstein (yes, he wrote film criticism), the Cahiers and Positif crews, and many more. Their powerful and provocative ideas yielded new ways to think about any movie.

Last year I moderated an Ebertfest panel consisting of a dozen or so critics. A student from the audience said he wanted to be a critic too. Instead of advising him to get into a more financially rewarding form of endeavor, like selling consumer electronics off the back of a truck, the panelists encouraged him. This form of altruism, in which you help people to become your competitor, is alarmingly common in the arts.

A moderator doesn’t get to talk much, so I couldn’t respond. What I wanted to say was: Forget about becoming a film critic. Become an intellectual, a person to whom ideas matter. Read in history, science, politics, and the arts generally. Develop your own ideas, and see what sparks they strike in relation to films.

Writing style is overrated. Many people think that good reviewing amounts to personal opinions whipped up in frothy prose. Perhaps the snazzy styles of Farber and Kael have led people to weight style too much. Granted, the Web has revealed that a lot of people are excellent writers, and without the Web they would probably never have found an audience. Although lively writing is always welcome, it gets heft and endurance through its arguments, and that comes back to ideas and information as much as opinion.

Hollywood, still declining

As often happens, a current controversy sends me backward, and to books. Ezra Goodman’s Fifty-Year Decline and Fall of Hollywood was published in the momentous year 1960, as was Beth Day’s This Was Hollywood. Both wrote finis to the glory days of American studio cinema. But if Day was nostalgic, Goodman was sour, and racy.

He worked as reporter, publicist, and reviewer, most notably for Time. By 1960, he must have felt he never needed an LA job again, so he castigates every specimen of Hollywoodite, from press agents to stars. Buddy Adler, who for a while ran production at Twentieth Century-Fox was no more than “a dutiful office boy.” Humphrey Bogart had “as a result of four marriages, innumerable bouts with the bottle, and a paucity of food and sleep developed what was described as a look of intelligent depravity. . . .”

Goodman includes a long chapter on film reviewers, which launches with a decidedly contemporary ring:

It has been said that there are sometimes more clichés in movie reviews than in the movies they are discussing. Sample review phrases: “sure-fire,” “stunning,” “taut with suspense,” “lavish and exciting,” “sumptuous,” “captures the imagination,” “moving,” “significant drama,” “sheer screen artistry,” “uncommonly good performance,” “dramatic urgency,” “enormous compulsion,” “spectacular finish,” and once in a while, “ineptly directed,” “singularly dull.”

Fifty years later, Goodman would have to add jaw-dropping, adrenalin-charged, mind-bending, hellish/ hellacious, resonance/ resonate, lush, dark, incredible, intensely personal, pitch-perfect, and our two all-purpose adjectives of praise, amazing and terrific. You’d think that we were staggering around astounded all the time.

Yet reading Fifty-Year Decline and Fall confirms my hunch that we have made progress. I would say that the best film writing in all registers–daily/ weekly reviewing, haute journalism, “think pieces,” personal essays, research studies, whether on the web or off– is much better today than it was in Goodman’s era. Then the New York Times had Bosley Crowther; now it has Dargis and Scott. Richard Schickel has hurt his reputation with some insulting remarks he made recently, but read his book on Fairbanks, His Picture in the Papers, or his scathing The Disney Version, and you’ll find a keen eye and a nonconformist intelligence. Riding above the oceanic fizz of infotainment, there are many sharp writers both journalistic and academic. Start clicking our link-list for examples.

Which makes it all the more lamentable that two of our finest writers have lost their platform. Todd McCarthy’s work for Variety long exemplified the virtues I’ve itemized. He writes a brisk prose that isn’t showoffish. His reviews, often in a few deft words, situate the film historically; he’s one of those guys who has simply seen and read everything. He has as well a guiding idea of cinema—roughly, I think, the premise that straightforward classical storytelling is an inexhaustible resource—but he doesn’t deploy it as a bludgeon. McCarthy’s respect for studio history and the tradition of expressive narrative can be found in his and Charles Flynn’s indispensible collection Kings of the Bs (where you can see what a Republic budget sheet looked like) and in his biography of Howard Hawks. There are also his documentaries on filmmaking (e.g., Visions of Light) and film culture (Man of Cinema: Pierre Rissient), which allow him the leisure to probe subjects in depth.

Or consider Derek Elley. He is one of the most knowledgeable writers on Asian cinema, and his reviews skillfully tie a new film to a trend or earlier work by the same director. Few critics have his ability to supply a translation of a Chinese film’s original title, or to explain a crucial local custom. By dismissing McCarthy and Elley as contract writers, Variety has dealt a blow to informative, thoughtful film writing, whether you call it criticism or not.

Daumier, One says that the Parisians. . . (1864)

Don’t knock the blockbusters

Promoting Pirates of the Caribbean in Japan (By tralala.online)

Kristin here:

When was the last time you heard someone complaining about the high cost of the latest Toyota prototype? Probably not recently, since car manufacturers don’t tend to boast about how much it costs them to design a new model. In fact, I couldn’t find any information on how much the development of automobile prototypes costs. Some new models catch on, some don’t. Presumably some don’t make a profit for their makers. The same tends to be true for other big-ticket items.

In a way, a film’s negative is like a prototype. It costs a lot for a mainstream commercial film to be made, tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in many cases, before the first distribution print is struck and the first ticket sold. Yet once that prototype exists, any number of distribution prints can be struck, and a film may make back many times its negative cost.

[Added October 28: A friend of mine privy to information about car manufacturing informs me that an ordinary prototype runs $50 to 250 million. A radically new product like an electric car could run over a billion. And car companies do keep those figures secret, so it’s no wonder I couldn’t find them.

Coincidentally, $50 to 250 million is pretty much the range of budgets for mainstream commercial Hollywood features these days.

My friend told me other things about car manufacturing that make it sound as though the comparison between the two industries is a pretty reasonable one. For example, car companies can save money by releasing new, slightly modified versions of a popular model, such as the Honda Civic, rather than designing a new model from the ground up. Sort of like sequels in the film industry. More surprisingly, when car manufacturers (and some companies in other industries) make their products by outsourcing some of the components, they call it the “Hollywood model.”]

For some reason, the cost of making that negative is often public knowledge. To some extent, at least, since we all know that the budget as acknowledged by a studio may be considerably less than the actual costs. The notion that a movie set its company back by $200 million is to some extent a selling point. I’m sure that back in 1922 Universal wasn’t happy that Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives ended up costing more than a million dollars. Still, they turned it to their advantage by advertising it as the first million-dollar movie, and studios have been using the same tactic ever since.

The producers and makers of other kinds of artworks don’t tend to make such information public. How much does it cost to put on a symphonic concert or publish a book? We may hear about big advances paid to an author, but that’s basically a lump-sum against future royalties, and the author doesn’t get any more until–if ever–the advance is paid off. But how much do editorial supervision, printing, and binding set a publisher back? What kind of money goes into the creation of a large stone sculpture?

Journalists looking for a hook for an article about movies find a sturdy one in the idea that today’s film budgets are bloated. They point to classic movies of decades past that cost only a few million to make and then compare these to the loud, overblown summer tentpoles of today, with their multi-hundred-million-dollar costs. Of course this overlooks the inflation of the dollar over the years. In the 1950s the average family income was about $5000 and an average house cost under $20,000. A penny bought a gumball and could be used in parking meters. Just about everything costs a lot more now.

To be sure, other factors have raised the budgets of films well beyond what they would be through inflation alone. The key factors have been star salaries and computer-generated special effects. The latter can account for half the cost of an effects-heavy film. Beyond the negative cost, typical budgets for prints and advertising have skyrocketed.

Some people seem to see an innate immorality in today’s biggest budgets, as well as an almost inevitable lack of quality in the films that result. Here’s one of the first results of a search on “big budget movies,” from Dmitry Sheynin on suite101.com. He even makes the car comparison:

The film industry has had a good summer this year – action sequences were bigger than ever, and expensive displays of pyrotechnics and CGI showcased new and exciting ways to destroy cinematic credibility.

With the economic crisis forcing many companies to scale down or even discontinue some of their more opulent product lines (think GM), it’s comforting to know Hollywood studios are still spending inordinate sums of money producing bad movies.

I think that’s fairly typical of the grousing you find on the internet and in print. No doubt Hollywood produces many bad movies. But actually, it is comforting to know that Hollywood is still spending great sums of money, ordinate or in-, if you think of the welfare of the country as a whole.

Every now and then I’ve pondered the possibility that American movies must be one of the products, if not the product, that has the most favorable balance of trade. While the US doesn’t have quite the stranglehold on world film markets that it used to, most significant Hollywood films get exported to numerous countries. Conversely, very few films from abroad are imported, and those that come in, especially the foreign-language ones, play in far fewer theaters and sell far fewer tickets than do domestic films. In 2006, according to US census figures, foreign films took in $216 million in the U.S., while domestic films sold $7.1 billion worth of tickets. So that’s 3% of the U.S. market for imported films, which is the figure I’ve heard pretty consistently for decades.

(In passing, I note from the same report that theaters made 66% of their income on tickets, meaning that we moviegoers spend about a third of our cash on all that stuff in the lobby.)

Turns out my ponderings have been correct. On the Motion Picture Association of America’s “Research & Statistics” page, there appears the claim, “We are the only American industry to run a positive balance of trade in every country in which we do business.” (“The industry” includes both film and television.) In April the MPAA put out its latest annual report, “The Economic Impact of the Motion Picture & Television Industry on the United States.” The combined trade surplus in the moving-picture industry for 2007 was $13.6 billion, or 10% of the US trade surplus in private sector services. According to the report, “The motion picture and television surplus was larger than the combined surplus of the telecommunications, management and consulting, legal, and medical services sectors, and larger than sectors like computer and information services and insurance services.”

Lest anyone think these figures are mere industry propaganda, the MPAA’s information, though made public, is gathered for the benefit of the film studios, which collectively own the association. Screen Digest, a highly respected trade publication, summarized some of the report’s material in its September issue (“Film and TV Are Key to US Economy,” p. 265).

For better or worse, most films that are really successful abroad are big-budget items, with lots of expensive special effects and (usually) top stars. Back in 1997 people were aghast at the first $200 million movie, Titanic—until it brought in nearly $2 billion around the world. Here, in unadjusted dollars, are the top foreign earners for the past nine years (not including domestic box-office):

2008 Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull $469,534,914

2007 Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End $651,576,067

2006 Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest $642,863,913

2005 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire $605,908,000

2004 Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban $546,093,000

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King $742,083,616

2002 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets $616,655,000

2001 Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone $657,158,000

2000 Mission: Impossible II $330,978,216

Add in the DVDs and ancillary products, and the balance of trade gets even more favorable.

Yes, it may sound absurd that it requires $200 million to make a movie, especially one that gets mediocre reviews from critics and fans. Still, from a business point of view, it makes sense and it’s good for the country. It’s especially important in a period of financial crisis, when the movie industry’s income seems considerably less affected than many others. Our overall trade deficit is falling, since Americans are saving more and buying less from abroad. This year the film and television industry’s share of the surplus will presumably grow.

Apart from the balance of trade, according to the MPAA report, in 2007 the moving-image industry also employed 2.5 million people, paid $41.1 billion in wages, spent $38.2 billion at vendors and suppliers, and handed over $13 billion in federal and local taxes.

If you think the trade deficit doesn’t affect you, think again the next time you travel abroad and curse the exchange rate with the euro or the yen.

No doubt there’s a great deal of waste and slippery dealing involved in those huge budgets, but there are definite advantages that don’t get considered often enough.

I do see a lot of foreign cars on the roads.

[October 23: Coincidentally, two days ago Steven Saito posted a story on how foreign-language films that have achieved blockbuster status in the rest of the world don’t stand much of a chance of getting into the American market. He mentions the “Christmas Vacation” series that I referred to in an earlier post.]