Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Has 3-D already failed?

Kristin here–

Years ago, James Cameron announced that his upcoming film, Avatar, would only be released to theaters capable of showing it in 3-D. Since then, he has proselytized fervently at trade shows and fan cons, hoping that Avatar would be such a blockbuster that exhibitors would finally decide to make that expensive leap and invest to convert their auditoriums to add 3-D.

Many commentators seemed to assume that Cameron’s saying such a thing would make it so. Here’s what Popular Mechanics opined only a little over a year ago:

Cameron’s insistence on 3-D projection will likely force the industry to ramp up the installation of 3-D technology dramatically. “Cameron is going to be able to bully theaters into compliance,” says former Premiere magazine critic Glenn Kenny. “He’s got the clout, and he’s got the mojo to do it. Everybody is going to want his next film.”

Avatar will need about 4,000 screens for a 3-D-only release, estimates Doug Darrow, manager of DLP brand and marketing at Texas Instruments, which makes the chips that power theatrical 3-D projectors. Of course, once the Avatar-inspired infrastructure is in place, other 3-D-only releases will follow.

The problems with conversion are manifest. Number one is the expense. 3-D systems are digital, so first the theater owner must convert from 35mm projectors to digital. 3-D is an add-on system that entails additional expenditure. A digital conversion alone costs over $100,000, about five times the cost of a 35mm platter projector. Right now most “D” theaters have 2K projection, but 4K is gradually being introduced for both shooting and showing. (Che and District 9 were shot mostly on 4K.) What theater owner wants to buy an expensive projector that will be obsolete within a few years? And what was supposed to be the breakthrough year for 3-D sees us at what may be the bottom of a huge financial crisis. It has slowed down an already laggardly process.

Among commentators, there’s apparently a lot of support for Cameron’s position. This year, coverage of Avatar has been considerable and has mostly echoed his prediction that this is the future of cinema. Geeks who tend to love special-effects-heavy sci fi and fantasy films also tend to long for all of those films to be 3-D. Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings cannot be converted into 3-D fast enough for them. They run websites to express their fervor and to report every new technical innovation and every rumor about a future film perhaps being made in 3-D.

I’ll admit that the signs that 3-D is finally going to become a routine and frequent method for making and exhibiting films are clearer than ever this year. More theater chains are announcing conversion to digital projection after years of resistance. More films in 3-D, and good films, are appearing, like Coraline and Up. And I have to admit that I enjoyed Monsters vs. Aliens more than its tepid reviews had suggested I might.

But there are negative signs as well. Perhaps most notably, the major proponents of 3-D, after years of berating the exhibition wing of the industry for its slow adoption of digital and 3-D technology, are still berating it. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had announced that all Dreamworks Animation features would henceforth be made in 3-D, is one such complainer. Cameron is another. As of now, roughly 320 of the U.K.’s 3600 screen are digital—which doesn’t entail that all have 3-D capacity. In the U.S. it’s 2500 out of 38,000.

These days, a major blockbuster may open on 4000 screens or more. Given Avatar’s massive budget, rumored at $237 million (not counting prints and advertising), Twentieth Century Fox couldn’t settle for showing only in 3-D, even if every properly equipped screen in the country showed it.

The recent theatrical free previews of scenes from Avatar in 3-D have renewed the claims that this approach is the future. Yet some commentators are cautious about that claim. The Guardian quotes Louise Tutt, deputy editor of Screen International: “It seems a little overambitious,” she says. “A little over-enthusiastic. I mean, take a film like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days – who needs to see that in 3-D? So no, I don’t believe it will happen.” She sighs. “But then who am I to contradict James Cameron?”

Cameron is a mighty force for change, no doubt. The Abyss and Terminator 2 introduced the sort of morphing technology that made digital effects a reality. But oddly, there aren’t a lot of other directors quite that gung-ho about 3-D. They’re willing to praise it and suggest that they may make films in 3-D, but they don’t go around to trade shows pressuring exhibitors to convert their theaters.

Peter Jackson, for example, keeps hinting at such a possibility. Apparently his team is testing the new Red camera’s 3-D model with an eye to using it in the remake of The Dambusters. That’s slated to be produced by Jackson and directed by Christian Rivers. But if Jackson were as enthusiastic about the process as Cameron, wouldn’t The Lovely Bones be in 3-D? Steven Spielberg hasn’t been pushing 3-D, although there are rumors about the Tintin films being 3-D. But rumors and expressed interest don’t influence exhibitors reluctant to invest in upgrading theaters on the basis of the still-limited 3-D product that’s out there so far. Where’s Ridley Scott in this debate? Well, to be fair, he called the Avatar footage “phenomenal,” but I don’t see him making 3-D movies and demanding that they play only in properly equipped theaters. Where’s Tim Burton? Even George Lucas, Mr. Digital Technology, who keeps saying that Star Wars will be converted to 3-D, doesn’t have Cameron’s zeal.

Retro-fitting movies is hugely expensive, by the way. One of the few retro-fitted titles, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas, has taken to returning annually, as if to remind us of that fact.

Even Pixar, which has said it will henceforth make all its films in 3-D, has been strangely low-key about its current project of re-doing the first two Toy Story films in 3-D and re-releasing them as a lead-up to the premiere of the third film, planned in 3D from the start. (This year the first two will be shown at the Venice film festival, which has added a 3-D prize.) Presumably they are content to provide both 3-D and 2-D prints.

We’re also not seeing a lot of directors in other countries clamoring for the option of making their movies in 3-D. Hollywood may dominate world cinema in terms of screen time occupied and tickets sold, but there are still thousands of movies made elsewhere each year.

There are still few enough theaters in the U.S. capable of showing 3-D movies that films end up with truncated runs. Coraline perhaps suffered most from being taken off screens while it still had commercial potential and before word of mouth had time to help it gain the audiences it deserved. The release of the partially 3-D Imax version of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was delayed by the fact that Transformers 2 was still occupying Imax theaters. I can’t help but wonder if there are some studio executives who look at this situation and, without announcing it to the world, decide that the films they’re about to greenlight will be made in 2-D. Plenty of those theaters to go around. (Well, not for all the independent films jostling each other in the market, but that’s another blog topic.)

Cameron has bowed to the inevitable and is allowing Avatar to play in both 3-D and 2-D theaters. It seems obvious that it will still take years before a film can go out into the world without 2-D 35mm prints being included in its distribution.

During those years, there’s the potential that 3-D will lose its luster for audiences. One of the main arguments always rolled out in favor of conversion is that theaters can charge more for 3-D screenings. Proportionately, theaters that show a film in 3-D will take in more at the box-office because they charge in the range of $3 more per ticket than do theaters offering the same title in a flat version.

But what happens when, say, half the films playing at any given time in a city are in 3-D? Will moviegoers decide that the $3 isn’t really worth it? Even now, would they pay $3 extra to see The Proposal or Julie & Julia in 3-D? The kinds of films that seem as if they call out for 3-D are far from being the only kinds people want to see. Films like these already make money on their own, unassisted by fancy technology.

Then there’s the fact that the extra $3 is not simply profit. There has to be an employee handing out the glasses, though sometimes the ticketseller does that. And those glasses in themselves cost money. Some will get damaged. When David and I saw Monsters vs. Aliens, there was a woman with a child, perhaps four years old, in front of us in the concession line. She handed both pairs of glasses to the kid while she dealt with paying for the refreshments. He had his fingers all over the lenses, of course.

If a theater is using the RealD 3-D system, it’s no big deal if kids with sticky fingers get hold of the glasses. They are so cheap as to be disposable, if the theater doesn’t want to bother collecting and re-using them. Problem is, the theater has to buy or rent a special silver screen to project on. The Dolby 3D system doesn’t require a special screen, but its glasses cost a whopping $50 apiece as of 2007. In Dolby theaters, you’ll find tense ushers waiting outside, making absolutely sure everyone returns theirs for washing and re-use.

[September 9: A Dolby representative informs me that the cost of the company’s glasses is currently $27.50, well as this information:

- The Dolby 3D glasses are high-performance, eco-friendly passive glasses that require no batteries or charging and can be reused hundreds of times without sacrificing image quality.

- The environmentally friendly and reusable glasses can be used repeatedly, significantly reducing the cost down to cents per pair per screening for exhibitors.

Thanks, Erin.]

No doubt 3-D enthusiasts would object that someday the system will be so routine that we’ll all have our own glasses and bring them along. That would cut the expenses to the theater, to be sure. But remember, different 3-D systems require different kinds of glasses. Are audiences willing to collect one of each and keep track of which they need to take along when they head for the theater—especially those $50 ones? (“Check the theaters listings, honey. Is it RealD or Dolby tonight?”) And there are more competitors entering the market, with their own glasses.

Is current audience enthusiasm permanent?

As usual, the studios take box-office figures to equal enthusiasm on the part of fans. In public, at least, they don’t speculate as to whether 3-D might again be, as it was in the 1950s, a mere fad or a specialized taste. But because spectators are willing to pay extra now because 3-D is still a novelty, does that mean they’ll maintain that attitude once 3-D is common?

Maybe not. And maybe even now not all filmgoers care. Some even dislike 3-D.

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

In my review of the 3-D “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” I wrote that I wished I had seen it in 2-D: “Since there’s that part of me with a certain weakness for movies like this, it’s possible I would have liked it more. It would have looked brighter and clearer, and the photography wouldn’t have been cluttered up with all the leaping and gnashing of teeth.” “Journey” will be released on 2-D on DVD, and I am actually planning to watch it that way, to see the movie inside the distracting technique. I expect to feel considerably more affection for it.

Ask yourself this question: Have you ever watched a 2-D movie and wished it were in 3-D? Remember that boulder rolling behind Indiana Jones in “Raiders of the Lost Ark?” Better in 3-D? No, it would have been worse. Would have been a tragedy.

He refutes the widespread argument in favor of realism:

There is a mistaken belief that 3-D is “realistic.” Not at all. In real life we perceive in three dimensions, yes, but we do not perceive parts of our vision dislodging themselves from the rest and leaping at us. Nor do such things, such as arrows, cannonballs or fists, move so slowly that we can perceive them actually in motion. If a cannonball approached that slowly, it would be rolling on the ground.

It’s true that the “coming at you!” effects in 3-D movies are disruptive. I remember the 3-D in Bwana Beowulf, excuse me, Beowulf primarily for those weapons thrusting out of the screen or the gratuitous overhead tracks past beams looking down toward the distant floor. More interesting, though, is that fact that although I saw Coraline and Up in 3-D, I remember them in 2-D. Those films didn’t throw spears at the spectator or otherwise seek to pierce that fourth wall with their props. Of course as I was watching, I noticed that the mise-en-scene had layers of depth and the figures a rounded look, but apparently my life-long movie habits filtered those aspects out as the films entered my memory. I look forward to seeing both films again on DVD, and given the fact that home-theater 3-D is still in its very early stages, I’ll probably see them flat. Fine with me.

Yes, Coraline was carefully designed with 3-D effects in mind, playing with skewed perspective to characterize the two worlds the heroine moves between. But as David showed by reproducing a frame here on our merely 2-D blog, the same motifs worked without the glasses. They’re quite similar, in fact, to the forced or distorted perspective used in German films of the 1920s.

We saw District 9 this week. No 3-D, and I for one am glad about that.

On August 26, TheOneRing.net, the premiere Tolkien site on the internet (for both novels and films), pointed to the current results of its ongoing poll. They asked, “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” Many of the fans who frequent TORN do so because of the films. They have heard rumors over the years, mainly hints dropped by Peter Jackson, that The Hobbit might be made in 3-D. So what is their reaction as reflected by the poll? As of August 26, 55% say no, 13% say emphatically no (“Ugh … 3-D?”), 13% are sitting on the fence, and 13% say yes.

[Aug. 29: For some reason the poll “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” has disappeared from TORN. It has been replaced by a discussion of the poll results on a discussion thread in the Message Boards.]

TORN subsequently checked with director Guillermo del Toro, who reassured them, “I can safely say that, as of this moment, there are absolutely NO conversations about doing the HOBBIT films in 3D.”

Of course, my title, “Has 3-D already failed?” was meant to be provocative. Its answer depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

Right now, the big proliferation is in tiny personal screens, iPod Touches, cell phones, portable gaming devices. Will teenagers allow themselves to look dorky by sitting with 3-D glasses staring at their phones? 3-D has the effect of making films that won’t play well on the very devices that studio heads would love to see playing their movies. So far, it is a remarkably inadaptable technology to try and force on people whose movie-playing gadgets change every few years. The big break-through, home-video 3-D, is aimed at a machine that people are supposedly abandoning in favor of other screens. 3-D movies on your computer? So much for inviting pals over for a sociable evening of popcorn and a movie in your impressive home theater.

Maybe Hollywood will forge ahead, despite all the obstacles I’ve mentioned. But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If that more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical. Given the banner year that Hollywood is having, I echo Daffy Duck in The Scarlet Pumpernickel when after his lover picks him up and, crying “Save me,” races from her forced marriage, he says,“So what’s to save?”

[September 17: On the occasion of the 3D Entertainment Summit, Variety has posted an article on the subject. It deals mainly with the losses of revenue from the fact that there are too many 3-D films jostling for too few equipped screens, saying that the format “is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success.”]

Now leaving from platform 1

From a Facebook post by Tahereh

To all my friends:

What can I reply to Hossein? He’s pursuing me so avidly, but you know he isnt really a prime catch. No education, no house. If it werent for the earthquake, I wouldnt give him a second look. But he does interest me a little—he’s made me lose track of my lines so many times!

Oh no, now he’s chasing me across the field. What can I tell him? BRB!

DB here:

Many people in the film industry hold media studies in disdain, and often the feeling is mutual. Filmmakers recoil from the abstrusities of Big Theory, and academics often consider filmmakers gearheads (just before wagging their fingers and warning us about the Intentional Fallacy). But scholars like Rick Altman, John Caldwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin, and me, and younger folks like Patrick Keating and Ben Wright have been trying to study filmmakers’ creative choices in concrete ways. Some of us even ask filmmakers what they were trying to do.

So it’s heartening to see movement in the other direction. For quite a while academically trained filmmakers like James Schamus and Todd Haynes have brought ideas from their university studies into their films. Recently Reid Rosefelt composed an enlightening blog entry on Kathryn Bigelow’s intellectual side. Now some terms and ideas are being spread even more widely across the industry.

For example, in a recent Entertainment Weekly story about why women viewers like horror, we read:

One of the most consistent tropes of the genre is the character whom filmmakers call ”the final girl” — the survivor.

Actually, it was Carol Clover, scholar of horror movies and Scandinavian epics, who came up with the “final girl” nickname in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Going back to the EW sentence, you notice that academics helped popularize the term genre too, which you seldom find in Hollywood’s patter before the 1970s. And the very word trope smells of classrooms and chalkdust.

Even more striking is a recent Variety article entitled, “Transmedia Storytelling Is Future of Biz.” Peter Caranicas explains that it involves “developing a piece of intellectual property across multiple media platforms.” The Star Wars franchise is the major modern instance, as Caranicas explains.

What Lucas did went several steps beyond old-style character licensing and brand extensions. He created a unified body of work with an extensive backstory and mythology, and he determinedly guarded its canon [another academic term—DB] while simultaneously opening up peripheral parts of his universe to exploration by other contributors.

One of my former students assures me that Kristin and I used the term “transmedia” back in the 1990s, but we have no memory of doing so. More relevantly, Liz Rosenthal reminds us that Peter Greenaway was pushing the concept in 1993. “If the cinema intends to survive, it has to make a pact and a relationship with concepts of interactivity and it has to see itself as only part of a multimedia cultural adventure.”

In any case, the person who brought the concept of transmedia storytelling to the forefront of media studies, and thus industry parlance, was another Wisconsin student, Henry Jenkins. Henry has made the concept part of his broader research into how modern media connect with audiences, particularly fan audiences. In his 1992 essay on Twin Peaks, he was already exploring how fans used the still-emerging internet to respond to a range of ancillary texts around Lynch’s TV series. You can get a quick acquaintance with his most recent ideas in this 2007 blog essay. For me, his argument emerged most vividly in a talk he gave at Madison some years ago. The lecture became the chapter “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” in his book Convergence Culture. For his more recent thinking, you can check his current course syllabus, which includes reading and web references, in the 11 August entry here.

The platform-shifting that Caranicas describes is planned and executed at the creative end, moving the story world calculatedly across media. These, dubbed by Jenkins “commercial extensions,” differ from “grassroots extensions,” which are created by audience members without the permission, or even the knowledge, of the creators. The commercial extensions are what I’ll be considering here.

From aggregator Movie MMORPG:

Welcome to a sophisticated world teetering on the edge of decadence. Get hammered on Italian cocktails. Fight your way out of a hospital jammed with nymphos. Cheat on your wife. Seduce a married man. Wander through the streets and stare at gushing water. Have you got what it takes to survive a day in LaNotteCity? You’ll get hooked, since the endgame is always inconclusive!

As it’s currently discussed, transmedia storytelling has two uncontroversial components and one rare but intriguing one.

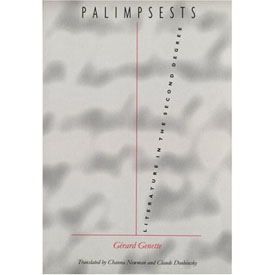

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

Novels and short stories feed off other novels and short stories. Obvious examples are parodies, pastiches, sequels, and continuations (sequels not written by the original author). Genette also considers what he calls the “transposition,” a very roomy category that’s of particular interest to us.

Transpositions are things like translations, rewritings, and literary adaptations, as when a novel becomes a play. A transposition also occurs when the original text is pruned or compressed, as in abridged versions of Don Quixote or Moby-Dick. At the other quantitative extreme is what Genette calls augmentation. Here, the derivative work expands the original, either in style (three sentences replace one) or narrative material (extra scenes or plots).

Yet another sort of transposition occurs when the story events in the original are rendered through alternative literary techniques. Charles Lamb retells Ulysses’ adventures in a different order than Homer does, and someone could rewrite the events of Madame Bovary in first person, from Charles’ point of view. When Genette was writing, he had to reach for some esoteric examples, but nowadays we have others. Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone (2001) retells Gone with the Wind from the point of view of a slave on Tara. The novel Wicked is a large-scale example, as is Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

All these examples of hypernarrative operate within a single medium. The second condition of transmedia storytelling is, of course, that it crosses media. Genette considers drama and written literature to be all part of the same medium, but if you don’t, then novels turned into plays, like Les Miserables, would count as transfers across media.

In this sense, transmedia storytelling is very, very old. The Bible, the Homeric epics, the Bhagvad-gita, and many other classic stories have been rendered in plays and the visual arts across centuries. There are paintings portraying episodes in mythology and Shakespeare plays. More recently, film, radio, and television have created their own versions of literary or dramatic or operatic works. The whole area of what we now call adaptation is a matter of stories passed among media.

What makes this traditional idea sexy? I think it’s a third, less common component that Henry has spotlighted. Some transmedia narratives create a more complex overall experience than that provided by any text alone. This can be accomplished by spreading characters and plot twists among the different texts. If you haven’t tracked the story world on different platforms, you have an imperfect grasp of it.

I can follow Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories well without seeing The Seven Percent Solution or The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. These pastiches/continuations are clearly side excursions, enjoyable or not in themselves and perhaps illuminating some aspects of the original tales. But according to Henry, we can’t appreciate the Matrix trilogy unless we understand that key story events have taken place in the videogame, the comic books, and the short films gathered in The Animatrix. The Kid in The Matrix Reloaded makes cryptic reference to finding Neo by fate, but only those who have watched the short devoted to him knows what that means. If Sherlock pastiches are parasites, the texts around The Matrix exist in symbiosis, giving as much as they take.

This strategy differentiates the new transmedia storytelling from your typical franchise. In most film franchises, the same characters play out their fixed roles in different movies, or comic books, or TV shows. You need not consume all to understand one. But Henry envisages the possibility of creating a whole that is greater than its parts, a vast narrative experience that doesn’t end when the book’s last page is turned or the theatre lights come up. His idea seems to be echoed in Will Wright’s suggestion:

It’s a fractal deployment of intellectual property. Instead of picking one format, you’re designing for one mega-platform. . . . We’ve been talking about this kind of synergy for years, but it’s finally happening.

Stimulating as this prospect is, it remains rare. The Matrix is perhaps the best example, but Henry suggests that it’s also an extreme instance: “For the casual consumer, The Matrix asked too much. For the hard-core fan, it provided too little” (p. 126). More common is a Genette-style transposition, in which the core text—usually the movie—is given offshoots and roundabouts that lead back to it. As I understand it, the Star Wars novels operate under the injunction that although they can take a story situation as the basis for a new plot, in the end that plot has to leave the films’ story arc unchanged. Similarly, websites with puzzles, games, clues, and other supplementary material tend to be subordinate to the film, planting hints and foreshadowings (The Blair Witch Project, Memento). Alternatively, the A. I. website provided a largely independent story world that impinged on the movie’s action only slightly.

The “immersive” ancillaries seem on the whole designed less to complete or complicate the film than to cement loyalty to the property, and even recruit fans to participate in marketing. It’s enhanced synergy, upgraded brand loyalty.

For the most part Hollywood is thinking pragmatically, adopting Lucas’ strategy of spinning off ancillaries in ways that respect the hardcore fans’ appreciation of the esoterica in the property. Caranicas quotes Jeff Gomez, an entrepreneur in transmedia storytelling, saying that for most of his clients “we make sure the universe of the film maintains its integrity as it’s expanded and implemented across multiple platforms.” It would seem to be a strategy of expanding and enriching fan following, and consequent purchases.

As best I can tell, then, in borrowing this academic idea, the industry is taking the radical edge off. But is that surprising?

Excerpt from www.ballsup.net

What a bloody week. Just now had a chance to update things. Fact is, it’s me last post. Luckily I let that cellphone drop and grabbed the satchel just before it fell into the Thames. Me and the crew are now packing for Bimini, ready for living large but in a rush becuz Big Chris may be looking for us. Hang on, must upload now, someone’s knocking at me d

Henry’s chapter in Convergence Culture grants that “relatively few, if any, franchises achieve the full aesthetic potential of transmedia storytelling—yet” (p. 97). Perhaps that hopeful “yet” will be fulfilled outside Hollywood? In the realm of the avant-garde, Matthew Barney has elaborated his own private mythology, dispersed among artifacts and hard-to-see films. In this he followed Joseph Beuys and Salvador Dalí. But you could argue that these artists really weren’t telling an overarching story. They were creating secular cults, full of arcana that only the pious initiates of Gallery Culture could grasp.

What about something more accessible? This month in Filmmaker magazine, Lance Weiler has suggested that indie filmmakers embrace the concept of transmedia storytelling (though he doesn’t use the term). Weiler argues that the explosion of digital technology has so transformed narrative that the filmmaker has to keep up. Instead of creating a script, with its genre formulas and three-act layout, the filmmaker should generate a bible, which plots an ensemble of characters and events that spills across film, websites, mobile communication, Twitter, gaming, and other platforms. The filmmaker designs “timelines, interaction trees, and flow charts” as well as “story bridges that provide seamless flow across devices and screens.”

Weiler doesn’t offer any specific examples apart from his Head Trauma, a horror feature accompanied by an alternate reality game that involved mobile and online access. You can watch his account of the “evolution of storytelling” here, where he and Ted Hope speculate about transmedia storytelling as offering economic help to filmmakers, reclaiming authorship from corporations, and promoting new relations with the audience.

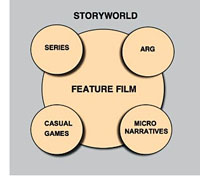

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

We should welcome experimentation, so I wish Hope, Weiler, and other creators well. But I think we ought to recognize some problems with expanding story worlds in these directions.

For one thing, most Hollywood and indie films aren’t particularly good. Perhaps it’s best to let most storyworlds molder away. Does every horror movie need a zigzag trail of web pages? Do you want a diary of Daredevil’s down time? Do you want to look at the Flickr page of the family in Little Miss Sunshine? Do you want to receive Tweets from Juno? Pursued to the max, transmedia storytelling could be as alternately dull and maddening as your own life.

Sure, somebody might go for it. Kristin points out, though, that people who would be motivated to follow up on all the transmedia bits of a spreadeagled narrative are people who would identify themselves as part of a fandom. There aren’t that many films/franchises that generate profoundly devoted fans on a large scale: The Matrix, Twilight, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Star Trek, maybe The Prisoner. These items are a tiny portion of the total number of films and TV series produced. It’s hard to imagine an ordinary feature, let alone an independent film, being able to motivate people to track down all these tributary narratives. There could be a lot of expensive flops if people tried to promote such things.

Consider a deeper point. Transmedia storytelling in the radical sense is posited as an active, participatory experience. Henry suggests that fans will race home from the multiplex to study up on iconography in The Matrix. Weiler’s article is accompanied by a hierarchy that lists “layers of interactivity.” The most superficial is “Passive Viewing,” defined as “Sit back and watch.” (Here Weiler parts company with Henry, who doesn’t consider ordinary viewing passive.) Further along are layers involving social networking, playing games, discussing or interacting with characters, finding hidden content, and even creating elements of the story world.

But it seems to me that film viewing is already an active, participatory experience. It requires attention, a degree of concentration, memory, anticipation, and a host of story-understanding skills. Even the simplest story gears up our minds. We may not notice this happening because our skills are so well-practiced; but skills they are. More complicated stories demand that we play a sort of mental game with the film. Trying to guess Hitchcock or Buñuel’s next twist can engross you deeply. And the very genre of puzzle films trades on brain strain, demanding that the film be watched many times (buy the DVD) for its narrational stratagems to be exposed. Films are interactive in the way a board game is: each move blocks certain possibilities, another anticipates what you’re going to do (mentally).

Moreover, how the ancillary texts add to the film is a crucial matter. No narrative is absolutely complete; the whole of any tale is never told. At the least, some intervals of time go missing, characters drift in and out of our ken, and things happen offscreen. Henry Jenkins suggests that gaps in the core text can be filled by the ancillary texts generated by fan fiction or the creators. But many films thrive by virtue of their gaps. In Psycho, just when did Marion decide to steal the bank’s money? There are the open endings, which leave the story action suspended. There are the uncertainties about motivation. In Anatomy of a Murder, did Lieutenant Manion kill his wife’s rapist in cold blood? Likewise, being locked to a certain character’s range of knowledge is the source of powerful emotional effects. We want to make the discoveries along with the character, be he Philip Marlowe or Travis Bickle.

The human imagination abhors a vacuum, I suppose, but many art works exploit that impulse by letting us play with alternative hypotheses about causes and outcomes. We don’t need the creators to close those hypotheses down. Indeed, you can argue that one of the contributions of independent film has been the possibility of pushing the audience toward accepting plots that don’t fit clear-cut norms. That innovation shrinks if we can run home to get background material online. By following the franchise logic, indie films risk giving up mystery.

At this point someone usually says that interactive storytelling allows the filmmaker to surrender some control to the viewer, who is empowered to choose her own adventure. This notion is worth a long blog entry in itself, so I’ll simply assert without proof: Storytelling is crucially all about control. It sometimes obliges the viewer to take adventures she could not imagine. Storytelling is artistic tyranny, and not always benevolent.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

In between opening and closing, the order in which we get story information is crucial to our experience of the story world. Suspense, curiosity, surprise, and concern for characters—all are created by the sequencing of story action programmed into the movie. It’s significant, I think, that proponents of hardcore multiplatform storytelling don’t tend to describe the ups and downs of that experience across the narrative. The meanderings of multimedia browsing can’t be described with the confidence we can ascribe to a film’s developing organization. Facing multiple points of access, no two consumers are likely to encounter story information in the same order. If I start a novel at chapter one, and you start it at chapter ten, we simply haven’t experienced the art work the same way. This isn’t to say, of course, that each of us has an identical experience of a movie. It’s just that our individual experiences of the film overlap to an extent that allows us to talk about the patterning of the story under our eyes.

In correspondence with me, Henry suggests that transmedia storytelling may work best with television because of the serialized format; different people hop aboard at different points. I’d add that television’s installment-based storytelling, operating in the lived time of the audience, allows time for viewers to explore or create media offshoots. The installment-based nature of serial TV poses intriguing aesthetic problems of continuity, coherence, and memory. (See Jason Mittell’s essay on this matter.) For films, however, which are typically designed to be consumed in one sitting, multiple points of entry will tend to make plot patterns less clearly profiled.

If transmedia storytelling is difficult to apprehend for the viewer, it also makes critical analysis and evaluation much more difficult. How might we analyze overarching patterns of multiplatform plotting in The Matrix? True, one can itemize the inputs and decipher the citations, but it’s very hard to show how they work together, how they unfold, what it all adds up to—except to note that different people will encounter information bits at different times and with different states of knowledge.

Gap-filling isn’t the only rationale for spreading the story across platforms, of course. Parallel worlds can be built, secondary characters can be promoted, the story can be presented through a minor character’s eyes. If these ancillary stories become not parasitic but symbiotic, we expect them to engage us on their own terms, and this requires creativity of an extraordinarily high order.

Henry Jenkins suggests that for big-budget projects, this means finding unusually gifted collaborators. In the indie sector, the obstacles are even more considerable. Whether the result is Wendy and Lucy or Goodbye Solo, creating a first-rate feature-length movie takes tremendous talent, sweat, and resourcefulness. It is immensely harder to create a story universe that sustains the same intensity and quality across platforms. True, you can sprinkle clues and cryptic references among websites and YouTube shorts. The formulas of genre (horror, mystery) help you generate shock effects and mystification in teaser trailers. Appeal to stock characterization helps you mount a “realistic” Second Life life. But building a vast, sturdy world teeming with distinctive characters, unpredictable plotting, and human resonance is an immense task.

We await our multimedia Balzac. In the meantime, maybe indie filmmakers should settle for trying to be Chekhov.

http://tinyurl.com/scarkiller

Debbie, sorry 2 hav left SOOOO suddenlike. am @ Gila flats = cactus + varmnts. LOL with Blankethead!!! :-/

Uncl Ethan

Thanks to Henry Jenkins for comments on this entry. He recommends that interested readers have a look at Geoffrey Long’s 2007 MA thesis on the Jim Henson company, available, along with many other MIT projects, here. Thanks also to Kristin and Jeff Smith for suggestions, and to Janet Staiger for correcting my memory and calling attention to Dennis Bound’s book on “transmedia poetics” as applied to Perry Mason.

PS 11 Sept: Henry Jenkins has responded to my entry, with the first of three installments starting here.

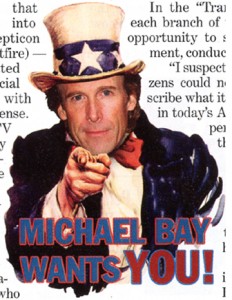

Your tax dollars at work for Michael Bay

Kristin here–

Back in July, when I was watching films at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, I managed to catch several of the films in the Frank Capra retrospective. Two of them, Dirigible (above and left) and Submarine, were surprisingly spectacular, given that at the time Columbia was still a relatively minor studio. It wasn’t known for high-budget items. How had Capra managed such lavish-looking films?

One clue lies in the title at the beginning of Dirigible: “Dedicated to the United States Navy without whose cooperation the production of this picture would not have been possible.” Clearly the film’s second sequence (from which both frames here were taken) was shot at an actual air field with real planes and dirigibles. Many shots in the scene were taken during what seems to have been a public air show.

One clue lies in the title at the beginning of Dirigible: “Dedicated to the United States Navy without whose cooperation the production of this picture would not have been possible.” Clearly the film’s second sequence (from which both frames here were taken) was shot at an actual air field with real planes and dirigibles. Many shots in the scene were taken during what seems to have been a public air show.

I recalled that when I was growing up, every now and then a movie I saw had a similar acknowledgement. Jimmy Stewart and other stalwart stars played government employees of various sorts, with pictures of impressive buildings in Washington and superimposed titles thanking this agency or that for its aid.

It also reminded me of The Lord of the Rings. One sequence in The Return of the King, the battle before the Black Gates, was shot in an old military practice range of the New Zealand army (right and below). The country, with its lush forests and stunning mountains, is short on desolate plains. The practice range was the only suitably Mordor-like landscape that could be found.

Not only did the army clear the field of unexploded ordnance, but it supplied soldiers to serve as extras by playing the Gondorian troops. The supplement on the extended-version DVD, “Cameras in Middle-earth,” shows these troops, as well as the officers who gave them orders. Apparently the soldiers were far more capable than regular extras of marching in straight lines and less willing to merely mime fighting during the battle.

Not only did the army clear the field of unexploded ordnance, but it supplied soldiers to serve as extras by playing the Gondorian troops. The supplement on the extended-version DVD, “Cameras in Middle-earth,” shows these troops, as well as the officers who gave them orders. Apparently the soldiers were far more capable than regular extras of marching in straight lines and less willing to merely mime fighting during the battle.

All this got me to wondering how much free or cheap labor and mise-en-scene movies have received from the military over the years. Coincidentally, when I got home in July, the stack of magazines awaiting me included an issue of Variety with the headline “Tanks a Lot, Uncle Sam,” on this very subject. In the article author Peter Debruge explains a lot about the nuts and bolts of how the military’s contributions work. (As often happens, Variety opted for a more dignified title for the same article online: “Film biz, military unite for mutual gain.”)

The occasion was the release of Transformers : Revenge of the Fallen. Lt. Col. Greg Bishop, an Iraqi vet appointed last year to handle the Army’s interface with Hollywood, says of it, “This is probably the largest joint-military movie ever made.” Indeed, Transformers enjoyed the assistance of four of the country’s five military branches, with the Coast Guard being the only exception. That’s unusual, as Bishop points out. Black Hawk Down mainly called upon the Army, Top Gun upon the Navy, and Iron Man upon the Air Force.

Debruge doesn’t offer a lot of historical background, but he does mention that the Vietnam War led to a period of anti-military films. Naturally the armed forces didn’t supply aid to films excoriating them. In recent decades relations have become chummier.

What are the typical financial arrangements? According to the article,

Hollywood has every incentive to seek the military’s blessing. A film like ‘Transformers’ gets much of the access, expertise and equipment for a fraction of what it would cost to arrange through private sources, with the production on the hook only for those expenses the government encounters as a direct consequence of supporting the film (such as transporting all that megabucks equipment to the set from the nearest military base). But the production pays no location fees for shooting on military property and no salaries to the service men and women who participate in the filming, in front of or behind the cameras.

In some cases, military exercises are arranged that can be incorporated into the filming. Capt. Bryon McGarry, the deputy director of the Air Force’s PR office, is quoted concerning a day when Transformers was shooting “at White Sands when a formation of six F-16s popped flares over the set, simulating a low-level, air-to-ground attack. ‘The flyover was very much the type of training the Air National Guard does every day. Only that day, Michael Bay and his cameras had a front-row seat to the air power show,’ he says.”

This sort of military assistance isn’t available to films that shoot entirely overseas, such as Saving Private Ryan and HBO’s Band of Brothers. Hence films like Transformers and Iron Man arrange to shoot some key sequences in the American West, where deserts and mountains can convincingly double for places like the Middle East.

Even in this day of elaborate CGI special effects, many directors prefer the real thing. For one thing, it often looks more realistic, and for another, CGI is really expensive.

Naturally the military doesn’t do all this for nothing. They want influence over the way the Armed Forces are depicted. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds had military assistance. The Pentagon’s film laiason, Phil Strub, says, “The big battle scene at the end was going to be different. We just wanted the case made that the Marines understood that they were not going to prevail, but they were nobly sacrificing so the civilians in that valley could escape.”

Naturally the military doesn’t do all this for nothing. They want influence over the way the Armed Forces are depicted. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds had military assistance. The Pentagon’s film laiason, Phil Strub, says, “The big battle scene at the end was going to be different. We just wanted the case made that the Marines understood that they were not going to prevail, but they were nobly sacrificing so the civilians in that valley could escape.”

Strub also decries “the enduring stereotype of the loner hero who must succeed by disobeying orders, going outside the rules by being stupid.” As Debruge points out, “By contrast, the ‘Transformers’ sequel embodies the military philosophy that teamwork is essential to success.”

The positive depiction of the military also might attract young people to enlist—and give enemies an impression of America’s overwhelming might. McGarry says, “Recruiting and deterrents are secondary goals, but they’re certainly there.”

The idea that Hollywood often gets in bed with the military won’t come as a surprise to anyone. (For a book emphasizing this aspect of the military’s involvement in filmmaking in the U.S., see David L. Robb’s Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies.) But the extent to which even the biggest—or maybe that should be especially the biggest—Hollywood films boost their budgets in a big way is less obvious. From the standpoint of the business history of Hollywood, it’s fascinating and deserves a closer look.

Color, shape, movement . . . and talk

Bonjour Tristesse.

DB here:

Our weekly Film Colloquium is sort of like your old high-school assembly, except that it’s fun. The Film Studies area meets nearly every Thursday afternoon at 4 to hear a paper by a grad student, a faculty member, or a guest. It’s a great forum for ideas and information, and it gives the speaker a chance to try out a talk before taking it to a conference or lecture gig. The local audience is, in my experience, the toughest I’m likely to encounter. And this spring, despite a heavy travel and work schedule, Kristin and I caught two outstanding presentations.

Not in color, but colored

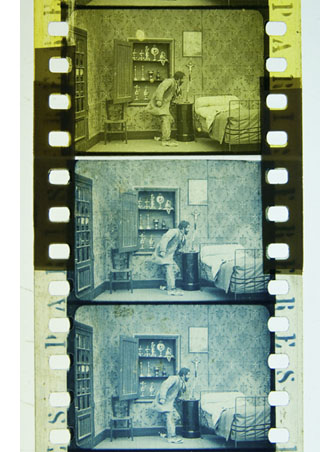

By now we all understand that silent films were most often shown with musical accompaniment, and sometimes sound effects. But we tend to forget that most silent films were in color too.

By the early 1920s, 80% of films were colored in one way or another. There were a few efforts to record the actual colors in a scene, but most often color was added after filming. Areas of the frame might be painted over by stenciling or by freehand. More commonly, the shots were dipped into dyes, yielding images that were tinted (washing over the image and coloring the areas of white, as in the frames below) or toned (coloring the darkest areas and leaving the white areas white). Over the years, film prints were preserved in black and white, partly because color stock was more expensive than today. As a result, even archival prints lost the sense of what audiences actually saw. Today archivists labor to reconstruct what silent films looked like in all their rainbow glory.

Professor Joshua Yumibe of Oakland University wrote his Ph. D. thesis on early color processes, and his Colloquium talk asked some powerful questions. We know that there was a transition in film artistry from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, a shift toward what Tom Gunning has called the “cinema of narrative integration.” As films became longer and were shown in more or less permanent venues, moviemakers began to tell more complicated stories. How, Josh asks, did this shift away from a cinema of isolated “attractions” affect practices of coloring? Do color processes affect the way stories were told? Do the color processes change how people saw the space on screen? How did the trade press respond to different strategies of coloring?

Professor Joshua Yumibe of Oakland University wrote his Ph. D. thesis on early color processes, and his Colloquium talk asked some powerful questions. We know that there was a transition in film artistry from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, a shift toward what Tom Gunning has called the “cinema of narrative integration.” As films became longer and were shown in more or less permanent venues, moviemakers began to tell more complicated stories. How, Josh asks, did this shift away from a cinema of isolated “attractions” affect practices of coloring? Do color processes affect the way stories were told? Do the color processes change how people saw the space on screen? How did the trade press respond to different strategies of coloring?

These are fascinating questions, and Josh’s exploration of them was careful and detailed. He has done enormous research on the various color processes, and he was able to trace several lines of development. For instance, he found that writers of the earliest years thought that color enhanced the sensual and emotional effects of the image, even creating an illusion of 3-D. In a shot like that of the butterfly dancer, people seem to have sensed that her multicolored shape was thrusting out of the screen toward them.

Josh argues that with the growing emphasis on narrative, color became more muted. Filmmakers were no longer aiming at momentary stimulation but at ongoing mood. Now tinting and toning came into their own. Color codes developed: blue for night scenes, yellow for sunlight, red for fire, amber for artificial light. Josh also explored the different ways in which European and US companies conceived of color; there seem to have been different color policies at Pathé and at American companies. But this wasn’t the end of change. In the 1920s, with the feature film now at the center of the theatre program, a wide variety of color practices emerged, including those isolated Technicolor sequences we find in films like The Wedding March.

The Q & A was as lively as the talk itself, and afterward, we repaired to a bar and thence to dinner. Josh’s talk was a model of deep, imaginative research and it kept us thinking and talking for a long time afterward. Not to mention his slide show, which regaled us with gorgeous shots that make you realize how much you’re missing when you see an old movie in black and white.

Bass, o profondo!

Another stimulating Colloq session was presided over by our old friend Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Chris was in town because our Cinematheque has been showcasing UCLA archival restorations across the semester, and he introduced our screening of The Dark Mirror. But we also got him to give a talk, and that was quite something.

Chris reminded me that we first met thirty years ago, here in Madison, when he came to do research on his dissertation. Since then Chris has been a top-flight scholar and author of many books. His Lovers of Cinema, published by our series at the UW Press, laid the groundwork for the popular film series Unseen Cinema. He’s also been one of the world’s leading film archivists, having supervised collections at Eastman House, the Munich Film Archive, Universal studios, and most recently UCLA.

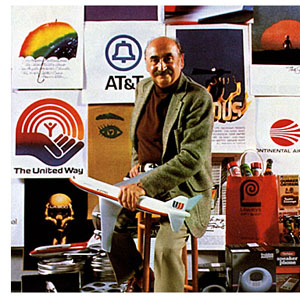

Chris has long worked at the intersection of film, photography, and the graphic arts. He is one of the world’s experts on the 1920s German avant-garde; one of his early curatorial coups was a 1979 restaging of the pioneering Film und Foto exhibition of 1929. Chris has also long been fascinated by film publicity, having written a book on the subject. So it’s natural that he would gravitate toward studying the film-related work of Saul Bass, one of America’s greatest graphic designers.

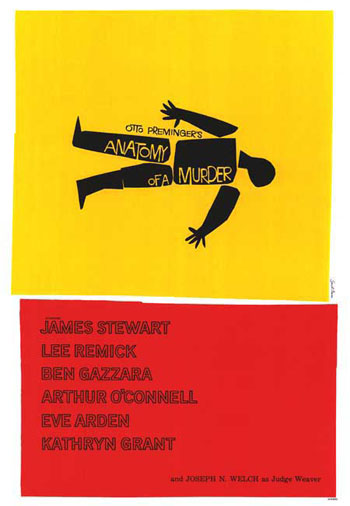

Chris’s talk focused not so much on Bass’s brilliant credit sequences for films by Preminger and Hitchcock as on Bass’s contributions to poster design. Bass turns out to have had a fascinating career, having worked in Manhattan advertising before moving to Los Angeles in 1948. Chris has found at least one early 1950s poster design that Bass probably executed, but he definitely worked for Preminger on publicity for The Moon Is Blue (1953) and Carmen Jones (1954)—the latter yielding to my mind one of the greatest credit sequences in film history. In 1955 Bass founded his own firm.

Chris’s talk focused not so much on Bass’s brilliant credit sequences for films by Preminger and Hitchcock as on Bass’s contributions to poster design. Bass turns out to have had a fascinating career, having worked in Manhattan advertising before moving to Los Angeles in 1948. Chris has found at least one early 1950s poster design that Bass probably executed, but he definitely worked for Preminger on publicity for The Moon Is Blue (1953) and Carmen Jones (1954)—the latter yielding to my mind one of the greatest credit sequences in film history. In 1955 Bass founded his own firm.

Throughout, he carried on the ideals of György Kepes, his teacher and a major conduit for Bauhaus ideas into America. Like his European models, Kepes promoted the idea of art as having cognitive value, teaching us to see the world in a new way. Kepes also emphasized that artworks could be of practical utility—an idea that chimed with Bass’s turn toward commercial design.

Chris was able to show that the Bauhaus tradition powerfully influenced Bass’s design principles. Who would have thought that the credits for The Seven Year Itch replayed Paul Klee? Obvious, though, when Chris showed us the images.

Chris emphasized two further points. First, Bass understood what we now call branding. We have to remember that it up to that time, most film publicity featured images of the stars, either in portraits or caught in typical scenes from the film. Bass’s poster design concealed the stars. Instead, he relied on dynamic geometrical design to capture a film’s mood in a powerful, stylized image. The result was an eye-catching logo, instantly recognizable: the flaming rose of Carmen Jones, the Vertigo whirlpool, the dismembered body of Anatomy of a Murder.

The key image could be repeated in newspaper ads, posters, credits, even the production company’s letterhead. When you saw the teaser trailer for Star Trek (“Under Construction”) dominated by that looming boomerang shape, you saw the heritage of Saul Bass. Who cares who’s in the movie? The very image is intriguing. No accident that Bass also designed many corporate logos, like the ATT bell and the United Way hand.

Chris’s second main point was that Bass was able to flourish because of the rise of independent production in the 1950s. Preminger, Hitchcock, and Wilder, acting as their own producers, could control the publicity for their films to a degree not possible for directors working in the classic studio system. Now films were sold as one-offs, and each film needed to pull itself above the clutter. In addition, Bass’s signature designs could set a director apart. In the 1950s, the Bass look was closely identified with his major clients like Hitchcock and Preminger, to the point that other designers for those directors tried to copy his style. I had always thought that Bass did the title design for Hurry Sundown, but Chris showed that it’s another artist’s pastiche of the master.

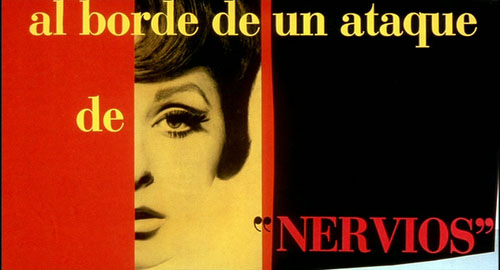

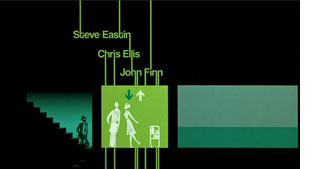

Chris’s talk reminded me that Bass contributed to making the opening credits a major attraction—not merely an overture, but an abstract treatment of the key story idea, a sort of graphic map that teases us into the main story. The opening sequences of Se7en and Catch Me If You Can (left) owe a lot to Bass’s idea that the credits should constitute a little movie, witty or ominous, tantalizing us with sketchy glimpses of what is to come. And Almodóvar’s diverting openings, probably the most sheerly enjoyable credit sequences we have today, are unthinkable without Bass. Synchronized with infectious music, Bass’s credit sequences can be seen as continuing the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, who back in the 1920s and 1930s made abstract films that advertised consumer goods.

Chris’s talk reminded me that Bass contributed to making the opening credits a major attraction—not merely an overture, but an abstract treatment of the key story idea, a sort of graphic map that teases us into the main story. The opening sequences of Se7en and Catch Me If You Can (left) owe a lot to Bass’s idea that the credits should constitute a little movie, witty or ominous, tantalizing us with sketchy glimpses of what is to come. And Almodóvar’s diverting openings, probably the most sheerly enjoyable credit sequences we have today, are unthinkable without Bass. Synchronized with infectious music, Bass’s credit sequences can be seen as continuing the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, who back in the 1920s and 1930s made abstract films that advertised consumer goods.

For such reasons, I’m glad I hung around Madison after my retirement. With visiting researchers like Josh and Chris, who wants to go fishing?

Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

Thanks to Joshua Umibe for the silent-film illustrations. The first comes from Gaston Velle, Métamorphoses du Papillon / A Butterfly’s Metamorphosis (Pathé, 1904). Frame enlargement from Discovering Cinema (di. Eric Lange and Serge Bromberg, Lobster Film/Flicker Alley). The second comes from Albert Capellani’s Le Chemineau / The Vagabond (Pathé, 1905; tinted and toned). Frame enlargement Joshua Yumibe, courtesy of the Netherlands Filmmuseum.