Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Filling the New Line gap

The Loews Santa Monica Beach Hotel, one of the AFM venues

Kristin here-

The 2008 American Film Market started yesterday. Like the film festivals at Cannes, Toronto, and, increasingly, Berlin, the AFM is one of the major places where independent and foreign-language films get sold. Distributors from all over the world come to sell their products and to buy the films that they will release at home. It seems a good occasion to look at what effect the folding-in of New Line Cinema into a unit within Warner Bros. early this year has had on the international independent film market.

The good old days

In my book The Frodo Franchise, Chapter 9 dealt with the impact of The Lord of the Rings on the film industry. There I discuss what effects the trilogy had on New Line and its parent company Time Warner. I also analyze the rise of the fantasy genre, the technological advances, and the boost given to the depressed indie market internationally. The 26 international independent distributors that financed a substantial portion of the film’s production through presales—with commitments to all three parts, sight unseen, at very steep prices—grew dramatically as a result of its success.

In 2001, an international slump in independent and foreign-language cinema started. The causes were complex, and I detail them in the book; they included a sag in advertising, the dot-com bust, the September 11 attacks, and the American dollar’s high exchange rate. With perfect timing, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring came out in December of 2001. Its theatrical and DVD earnings in 2002 poured money into the market through the 26 companies’ ability to buy new product when other distributors were still strapped for cash. By early 2004, the market had substantially recovered. Rings wasn’t the only factor aiding that recovery, but it was a major one.

That section of Chapter 9 is one of the parts of the book I’m proudest of. Most people interested in film knew something about most of the topics I covered. They were probably at least vaguely aware of the video games and other tie-in products, the highest successful internet campaign, the growth in filmmaking and tourism in New Zealand, and so on. But the fact that this massive blockbuster was an independently financed film, sold on the independent market, and highly beneficial to that market was something completely unknown except to specialists within the industry. I cottoned onto it only because there were a few references to these distributors’ unusual buying power during the coverage of the 2003 Cannes Film Festival and AFM in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.

Beyond those brief discussions, there was really no way I could research the topic without talking to people involved. That meant interviewing some of the executives of those 26 companies and someone very expert in the international indie market. A very helpful source was Mads Nedergaard, then of SF-Film, Copenhagen, who provided marvelous information for my major case study in that chapter. For the expert, I decided upon Jonathan Wolf, then and now the Managing Director of the AFM. Luckily he agreed to be interviewed. During our conversation Jonathan remarked that he had been very struck that I understood that Rings was an independent film and that it had had a positive impact on international markets. I gather that’s why he agreed to the interview, during which he furnished me with valuable insights. Those two interviews really made that part of the chapter possible.

Despite the huge success of the trilogy, New Line continued to function as an independent, financing its films through presales of distribution rights and of licensing fees for ancillary products. It continued to sell them at events like the AFM, as well as having regular output deals with some of the same overseas companies that it had been dealing with for nearly a decade. New Line was one of the main U.S. firms supplying such distributors. Its growing success ultimately became part of what got the studio into trouble.

What had worked so well for Rings continued to work until the blockbuster fantasy trilogy that had been touted as the successor to Rings. The Golden Compass was financed in the same way, with special rights pre-sold to foreign distributors, many of them the same ones that had handled Rings. The problem was that Compass did tepid business in the U.S. but was a distinct success abroad. That money stayed with the foreign distributors.

Absorbed into Warner Bros.

The Compass problem coincided with the promotion of Jeff Bewkes as CEO of Time Warner at a time when the conglomerate’s stock price was low. The real problem was the encumbrance of AOL, but that was a problem that would take time to solve. New Line’s lack of success with its big Christmas release made it a target. Bewkes could slash the company as a signal to stockholders that he would streamline Time Warner. On February 25, he announced that New Line would be folded into Time Warner, to become a production unit specializing in the sort of genre fare that had sustained New Line for so long, such as the Nightmare on Elm Street series. It would also continue to produce the occasional major film, such as The Hobbit.

The point of absorbing New Line into Warner Bros. was largely to downsize the former by eliminating its distribution and other departments that could be handled by Warners. With Warners distributing New Line films abroad, the income would return to the studio rather than remaining with foreign distributors. Receiving financing from Warners, New Line would no longer need to finance films through presales.

For Time Warner, this made sense, but it was a blow to the overseas distributors with regular output deals with New Line. New Line and Miramax had provided steady product to these companies, which otherwise would have to compete in the open market on a film-by-film basis. With the departure of the Weinstein brothers from Miramax, that firm had dried up as a source, leaving the burden on New Line. Now New Line was disappearing as well.

What now?

In the 7 March 2008 issue of Screen International (the online version is subscription only), Mike Goodridge discussed where these distributors might be able to turn after the expiration of their New Line contracts. He pointed out, “The distribution partners had good years and bad with New Line. None were thrilled with The Long Kiss Goodnight or The Island Of Dr. Moreau but for every flop, there was a Seven or Austin Powers, a Mask or Rush Hour.” He also confirms my claims about the Rings trilogy’s impact on its international distributors: “The success of the three films for the international partners cannot be overestimated. Nor can the fact that they, more than anybody involved, took a huge risk on the trilogy. The risk paid off. The Greens at Entertainment [the U.K. distributor], the Hadidas at Metropolitan [the French distributor] and others genuinely shared in the profits of one of the box-office phenomenons of the last 20 years. It was the international buyers’ dream. Instead of losing money on studio cast-offs, they had a hefty piece of a trilogy which grossed nearly $2bn outside North America.” New Line’s disappearance as a source of hit films “brings a dramatic sea change to the complexion of the global business,” according to Goodridge. These independent firms “will be competing for an increasingly small number of tentpole pictures available to them.”

Where have these distributors turned for films? In some cases their contracts with New Line, which predate the studio’s absorption into Warner Bros., are good through 2009. That means, however, that those distributors are already looking ahead for releases after the contracts end. At Cannes this year, New Line had a much-reduced presence. Camela Galano, one of the executives who had been in the studio’s international sales wing for years, was promoted to being its president in May. She brought only Journey to the Center of the Earth. Galano told Variety, “We just won’t be selling movies … but we’ll be doing what we normally do with our outputs, which is go through the lineup, releases and materials.”

A number of firms at Cannes stepped up to fill in the void left by New Line’s withdrawal from distribution. One up-and-coming firm, QED, was selling Oliver Stone’s W, the sci-fi film District 9 (produced by Peter Jackson and due out in the U.S. next August 14), and the Milla Jovovich thriller A Perfect Getaway. Gary Michael Walters, co-president of Bold Films, commented that he saw an opportunity presented by Warners’ takeover of New Line’s foreign distribution. “We see a sweet spot in that niche of $10 million-$30 million smart but commercial pictures.” Similar rising firms include IM Global, formed by the former head of Miramax International, Stuart Ford. (See Variety‘s summary here.)

John Hazleton analyzed the impact of New Line’s withdrawal from the international market for Screen International just before Cannes (May 9, 2008 issue). Hazleton harks back to the impact of Rings and other New Line franchises:

Many sales executives, in fact, go further and suggest that by boosting the fortunes of the distributor partners with which it had ongoing output or package deals—companies including the UK’s Entertainment, France’s Metropolitan, Australia’s Villege Roadshow and Spain’s Tri Pictures—New Line effectively elevated the independent international industry as a whole. Other sellers benefited, for example, when the New Line distributors reinvested profits from The Lord of the Rings and Rush Hour movies—or from last Christmas’ The Golden Compass—in the acquisition of non-New Line films.

No wonder, then, [that] the decision by parent Warner Bros to turn New Line into a stripped-down genre label whose films will (once current deals expire) be distributed worldwide by the studio is having such an impact in the independent arena. Filling the New Line void has suddenly become a pressing need, or an enticing opportunity, for all sorts of independent players.

One such player is Hyde Park International, whose president Lisa Wilson told Hazleton, “We’re certainly seeing an uptick in interest from distributors who previously didn’t need as much product because they were secure in having the New Line output. They’ve been making more of an effort than usual to meet us before Cannes.” Another is The Film Department, selling two films under production, Law Abiding Citizen, a thriller starring Gerard Butler, and The Rebound, a Catherine Zeta-Jones vehicle.

Hazleton identifies two major independent films suppliers that are stepping into the supply gap left by New Line’s departure:

Leading the field of remaining big picture suppliers are Summit Entertainment and the combination of Lionsgate and Mandate formed when the former acquired the latter last September. Crucially, like New Line, each group now has its own North American theatrical distribution operation, giving international buyers assurance that films will get a domestic theatrical launch and allowing the co-ordination of domestic and international release dates.

Summit is new to the domestic distribution business. But it is a company with vast international experience that plans to handle 10-12 films in the $15m-$45m budget range a year. Its Cannes slate includes Terrence Malick’s drama Tree of Life, starring Brad Pitt, and it already has output deals for its own productions in France, Germany, UK and Scandinavia.

In Lionsgate, Mandate has a well-proven domestic distribution outlet that last year scored three $50m-plus box-office hits and this year has a bigger market share than any independent or studio specialty division.

As the combination’s international arm, Mandate—which will be in Cannes with titles including Whip It! featuring rising star Ellen Page, and family animation Alpha And Omega—handles around half of Lionsgate’s domestic slate plus titles from third-party producers.

New Line’s withdrawal, says Helen Lee Kim, president of Mandate International, “just puts us in a better situation, because you can count on one hand the independent companies able to bring studio-level product to the marketplace.”

Hazleton also points out that “Studio-owned sales operations Paramount Vantage and Focus Films International [a Universal subsidiary] will be another alternative source for buyers.” In general, though, the Hollywood studios’ recent retreat from art-house divisions means that they will have less to contribute to foreign distributors.

Summit and Mandate are both participating in the AFM as well. Another major firm is Relativity Media, a rapidly expanding production-distribution independent responsible for such recent films as 3:10 to Yuma, Atonement, Baby Mama, and Pineapple Express. Relativity had expanded into international sales this year at Cannes. In October it offered $150 million for Universal’s Rogue Pictures and will gain the 40-50 projects that genre division has in the works. As the AFM began, it had just signed long-term output contracts with nine foreign distributors. Finally, Relativity has, according to Variety, “partnered with sales company Mandate Intl. to oversee sales in non-output territories as well as provide worldwide servicing of the slate.”

Other sales firms at Cannes included Odd Lot and Essential, and new companies debuting at the AFM this year were FilmNation, Exclusive Film Distribution, Icon Entertainment, and WestEnd Films. Some of these companies will grow, others won’t. But gradually they will absorb the market position formerly held by New Line.

So does all this mean that the impact of New Line’s glory days is over? Not entirely. I believe that although the distribution of The Lord of the Rings has receded five years into the past and New Line has now disappeared as an independent entity, the trilogy’s impact still lingers in the international industry. Steve Bickel, president of The Film Department, commented to Screen International shortly before Cannes, “The loss of any independent or independent-spirited company is a loss to the industry. New Line provided a great service to all of us because they helped make strong companies that we’re now able to sell to.”

Superheroes for sale

DB here:

After a day at the movies, maybe I am living in a parallel universe. I go to see two films praised by people whose tastes I respect. I find myself bored and depressed. I’m also asking questions.

Over the twenty years since Batman (1989), and especially in the last decade or so, some tentpole pictures, and many movies at lower budget levels, have featured superheroes from the Golden and Silver age of comic books. By my count, since 2002, there have been between three and seven comic-book superhero movies released every year. (I’m not counting other movies derived from comic books or characters, like Richie Rich or Ghost World.)

Until quite recently, superheroes haven’t been the biggest money-spinners. Only eleven of the top 100 films on Box Office Mojo’s current worldwide-grosser list are derived from comics, and none ranks in the top ten titles. But things are changing. For nearly every year since 2000, at least one title has made it into the list of top twenty worldwide grossers. For most years two titles have cracked this list, and in 2007 there were three. This year three films have already arrived in the global top twenty: The Dark Knight, Iron Man, and The Incredible Hulk (four, if you count Wanted as a superhero movie).

This 2008 successes have vindicated Marvel’s long-term strategy to invest directly in movies and have spurred Warners to slate more comic-book titles. David S. Cohen analyses this new market here. So we are clearly in the midst of a Trend. My trip to the multiplex got me asking: What has enabled superhero comic-book movies to blast into a central spot in today’s blockbuster economy?

Enter the comic-book guys

It’s clearly not due to a boom in comic-book reading. Superhero books have not commanded a wide audience for a long time. Statistics on comic-book readership are closely guarded, but the expert commentator John Jackson Miller reports that back in 1959, at least 26 million comic books were sold every month. In the highest month of 2006, comic shops ordered, by Miller’s estimate, about 8 million books (and this total includes not only periodical comics but graphic novels, independent comics, and non-superhero titles). There have been upticks and downturns over the decades, but the overall pattern is a steep slump.

Try to buy an old-fashioned comic book, with staples and floppy covers, and you’ll have to look hard. You can get albums and graphic novels at the chain stores like Borders, but not the monthly periodicals. For those you have to go to a comics shop, and Hank Luttrell, one of my local purveyors of comics, estimates there aren’t more than 1000 of them in the U. S.

Moreover, there’s still a stigma attached to reading superhero comics. Even kitsch novels have long had a slightly higher cultural standing than comic books. Admitting you had read The Devil Wears Prada would be less embarrassing than admitting you read Daredevil.

For such reasons and others, the audience for superhero comics is far smaller than the audience for superhero movies. The movies seem to float pretty free of their origins; you can imagine a young Spider-Man fan who loved the series but never knew the books. What’s going on?

Men in tights, and iron pants

The films that disappointed me on that moviegoing day were Iron Man and The Dark Knight. The first seemed to me an ordinary comic-book movie endowed with verve by Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. While he’s thought of as a versatile actor, Downey also has a star persona—the guy who’s wound a few turns too tight, putting up a good front with rapid-fire patter (see Home for the Holidays, Wonder Boys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Zodiac). Downey’s cynical chatterbox makes Iron Man watchable. When he’s not onscreen we get excelsior.

Christopher Nolan showed himself a clever director in Memento and a promising one in The Prestige. So how did he manage to make The Dark Knight such a portentously hollow movie? Apart from enjoying seeing Hong Kong in Imax, I was struck by the repetition of gimmicky situations–disguises, hostage-taking, ticking bombs, characters dangling over a skyscraper abyss, who’s dead really once and for all? The fights and chases were as unintelligible as most such sequences are nowadays, and the usual roaming-camera formulas were applied without much variety. Shoot lots of singles, track slowly in on everybody who’s speaking, spin a circle around characters now and then, and transition to a new scene with a quick airborne shot of a cityscape. Like Jim Emerson, I thought that everything hurtled along at the same aggressive pace. If I want an arch-criminal caper aiming for shock, emotional distress, and political comment, I’ll take Benny Chan’s New Police Story.

Then there are the mouths. This is a movie about mouths. I couldn’t stop staring at them. Given Batman’s cowl and his husky whisper, you practically have to lip-read his lines. Harvey Dent’s vagrant facial parts are especially engaging around the jaws, and of course the Joker’s double rictus dominates his face. Gradually I found Maggie Gyllenhaal’s spoonbill lips starting to look peculiar.

The expository scenes were played with a somber knowingness I found stifling. Quoting lame dialogue is one of the handiest weapons in a critic’s arsenal and I usually don’t resort to it; many very good movies are weak on this front. Still, I can’t resist feeling that some weighty lines were doing duty for extended dramatic development, trying to convince me that enormous issues were churning underneath all the heists, fights, and chases. Know your limits, Master Wayne. Or: Some men just want to watch the world burn. Or: In their last moments people show you who they really are. Or: The night is darkest before the dawn.

I want to ask: Why so serious?

Odds are you think better of Iron Man and The Dark Knight than I do. That debate will go on for years. My purpose here is to explore a historical question: Why comic-book superhero movies now?

Z as in Zeitgeist

More superhero movies after 2002, you say? Obviously 9/11 so traumatized us that we feel a yearning for superheroes to protect us. Our old friend the zeitgeist furnishes an explanation. Every popular movie can be read as taking the pulse of the public mood or the national unconscious.

I’ve argued against zeitgeist readings in Poetics of Cinema, so I’ll just mention some problems with them:

*A zeitgeist is hard to pin down. There’s no reason to think that the millions of people who go to the movies share the same values, attitudes, moods, or opinions. In fact, all the measures we have of these things show that people differ greatly along all these dimensions. I suspect that the main reason we think there’s a zeitgeist is that we can find it in popular culture. But we would need to find it independently, in our everyday lives, to show that popular culture reflects it.

*So many different movies are popular at any moment that we’d have to posit a pretty fragmented national psyche. Right now, it seems, we affirm heroic achievement (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Kung Fu Panda, Prince Caspian) except when we don’t (Get Smart, The Dark Knight). So maybe the zeitgeist is somehow split? That leads to vacuity, since that answer can accommodate an indefinitely large number of movies. (We’d have to add fractions of our psyche that are solicited by Sex and the City and Horton Hears a Who!)

*The movie audience isn’t a good cross-section of the general public. The demographic profile tilts very young and moderately affluent. Movies are largely a middle-class teenage and twentysomething form. When a producer says her movie is trying to catch the zeitgeist, she’s not tracking retired guys in Arizona wearing white belts; she’s thinking mostly of the tastes of kids in baseball caps and draggy jeans.

* Just because a movie is popular doesn’t mean that people have found the same meanings in it that critics do. Interpretation is a matter of constructing meaning out of what a movie puts before us, not finding the buried treasure, and there’s no guarantee that the critic’s construal conforms to any audience member’s.

*Critics tend to think that if a movie is popular, it reflects the populace. But a ticket is not a vote for the movie’s values. I may like or dislike it, and I may do either for reasons that have nothing to do with its projection of my hidden anxieties.

*Many Hollywood films are popular abroad, in nations presumably possessing a different zeitgeist or national unconscious. How can that work? Or do audiences on different continents share the same zeitgeist?

Wait, somebody will reply, The Dark Knight is a special case! Nolan and his collaborators have strewn the film with references to post-9/11 policies about torture and surveillance. What, though, is the film saying about those policies? The blogosphere is already ablaze with discussions of whether the film supports or criticizes Bush’s White House. And the Editorial Board of the good, gray Times has noticed:

It does not take a lot of imagination to see the new Batman movie that is setting box office records, The Dark Knight, as something of a commentary on the war on terror.

You said it! Takes no imagination at all. But what is the commentary? The Board decides that the water is murky, that some elements of the movie line up on one side, some on the other. The result: “Societies get the heroes they deserve,” which is virtually a line from the movie.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). That’s the bait the Times writers took.

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Back to basics

If the zeitgeist doesn’t explain the flourishing of the superhero movie in the last few years, what does? I offer some suggestions. They’re based on my hunch that the genre has brought together several trends in contemporary Hollywood film. These trends, which can commingle, were around before 2000, but they seem to be developing in a way that has created a niche for the superhero film.

The changing hierarchy of genres. Not all genres are created equal, and they rise or fall in status. As the Western and the musical fell in the 1970s, the urban crime film, horror, and science-fiction rose. For a long time, it would be unthinkable for an A-list director to do a horror or science-fiction movie, but that changed after Polanski, Kubrick, Ridley Scott, et al. gave those genres a fresh luster just by their participation. More recently, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It, the fantasy film arrived as a respectable genre, as measured by box-office receipts, critical respect, and awards. It seems that the sword-and-sorcery movie reached its full rehabilitation when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King scored its eleven Academy Awards.

The comic-book movie has had a longer slog from the B- and sub-B-regions. Superman, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy were all fodder for serials and low-budget fare. Prince Valiant (1954) was the only comics-derived movie of any standing in the 1950s, as I recall, and you can argue that it fitted into a cycle of widescreen costume pictures. (Though it looks like a pretty camp undertaking today.) Much later came revivals of the two most popular superheroes, Superman (1978) and Batman (1989).

The success of the Batman film, which was carefully orchestrated by Warners and its DC comics subsidiary, can be seen as preparing the grounds for today’s superhero franchises. The idea was to avoid simply reiterating a series, as the Superman movie did, or mocking it, as the Batman TV show did. The purpose was to “reimagine” the series, to “reboot” it as we now say, the way Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns re-launched the Batman comic. Rebooting modernizes the mythos by reinterpreting it in a thematically serious and graphically daring way.

During the 1990s, less famous superheroes filled in as the Batman franchise tailed off. Examples were The Rocketeer (1991), Timecop (1994), The Crow (1994) and The Crow: City of Angels (1996), Judge Dredd (1995), Men in Black (1997), Spawn (1997), Blade (1998), and Mystery Men (1999). Most of these managed to fuse their appeals with those of another parvenu genre, the kinetic action-adventure movie.

Significantly, these were typically medium-budget films from semi-independent companies. Although some failed, a few were huge and many earned well, especially once home video was reckoned in. Moreover, the growing number of titles, sometimes featuring name actors, fueled a sense that this genre was becoming important. As often happens, marginal companies developed the market more nimbly than the big ones, who tend to move in once the market has matured.

I’d also suggest that The Matrix (1999) helped legitimize the cycle. (Neo isn’t a superhero? In the final scene he can fly.) The pseudophilosophical aura this movie radiated, as well as its easy familiarity with comics, videogames, and the Web, made it irrevocably cool. Now ambitious young directors like Nolan, Singer, and Brett Ratner could sign such projects with no sense they were going downmarket.

The importance of special effects. Arguably there were no fundamental breakthroughs in special-effects technology from the 1940s to the 1960s. But with motion-control cinematography, showcased in the first Star Wars installment (1977) filmmakers could create a new level of realism in the use of miniatures. Later developments in matte work, blue- and green-screen techniques, and digital imagery were suited to, and driven by, the other genres that were on the rise—horror, science-fiction, and fantasy—but comic-book movies benefited as well. The tagline for Superman was “You’ll believe a man can fly.”

Special effects thereby became one of a film’s attractions. Instead of hiding the technique, films flaunted it as a mark of big budgets and technological sophistication. The fantastic powers of superheroes cried out for CGI, and it may be that convincing movies in the genre weren’t really ready until the software matured.

The rise of franchises. Studios have always sought predictability, and the classic studio system relied on stars and genres to encourage the audience to return for more of what it liked. But as film attendance waned, producers looked for other models. One that was successful was the branded series, epitomized in the James Bond films. With the rise of the summer blockbuster, producers searched for properties that could be exploited in a string of movies. A memorable character could tie the installments together, and so filmmakers turned to pop literature (e.g., the Harry Potter books) and comic books. Today, Marvel Enterprises is less concerned with publishing comics than with creating film vehicles for its 5000 characters. Indeed, to get bank financing it put up ten of its characters as collateral!

Yet a single character might not sustain a robust franchise. Henry Jenkins has written about how popular culture is gravitating to multi-character “worlds” that allow different media texts to be carved out of them. Now that periodical sales of comics have flagged, the tail is wagging the dog. The 5000 characters in the Marvel Universe furnish endless franchise opportunities. If you stayed for the credit cookie at the end of Iron Man, you saw the setup for a sequel that will pair the hero with at least one more Marvel protagonist.

Merchandising and corporate synergy. It’s too obvious to dwell on, but superhero movies fit neatly into the demand that franchises should spawn books, TV shows, soundtracks, toys, apparel, and so on. Time Warner’s acquisition of DC Comics was crucial to the cross-platform marketing of the first Batman. Moreover, most comics readers are relatively affluent (a big change from my boyhood), so they have the income to buy action figures and other pricy collectibles, like a Batbed.

The shift from an auteur cinema to a genre cinema. The classic studio system maintained a fruitful, sometimes tense, balance between directorial expression and genre demands. Somewhere in recent decades that balance has split into polarities. We now have big-budget genre films that made by directors of no discernible individuality, and small “personal” films that showcase the director’s sensibility. There have always been impersonal craftsmen in Hollywood, but the most distinctive directors could often bring their own sensibilities to projects big or small.

David Lynch could make Dune (1984) part of his own oeuvre, but since then we have many big-budget genre pictures that bear no signs of directorial individuality. In particular, science-fiction, fantasy, and superhero movies demand so much high-tech input, so much preparation, so many logistical tasks in shooting, and such intensive postproduction, that economy of effort favors a standardized look and feel. Hence perhaps the recourse to well-established techniques of shooting and cutting; intensified continuity provides a line of least resistance. A comic-book movie can succeed if it doesn’t stray from the fanbase’s expectations and swiftly initiates the newbies. Not much directorial finesse is needed, as 300 (2007) shows.

The development of the megapicture may have led the more talented directors to the “one for them, one for me” motto. Think of the difference between Burton’s Planet of the Apes or even Sweeney Todd and, say, Ed Wood or Big Fish. Or think of the moments of elegance in Memento and The Prestige, as opposed to the blunt handling of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Too much is never enough. Since the 1980s, mass-audience pictures have gravitated toward ever more exaggerated presentation of momentary effects. In a comedy, if a car is about to crash, everyone inside must stare at the camera and shriek in concert. Extreme wide-angle shooting makes faces funny in themselves (or so Barry Sonnenfeld thinks). Action movies shift from slo-mo to fast-mo to reverse-mo, all stitched together by ramping, because somebody thinks these devices make for eye candy. Steep high and low angles, familiar in 1940s noir films, were picked up in comics, which in turn re-influenced movies.

Movies now love to make everything airborne, even the penny in Ghost. Things fly out at us, and thanks to surround channels we can hear them after they pass. It’s not enough simply to fire an arrow or bullet; the camera has to ride the projectile to its destination—or, in Wanted, from its target back to its source. In 21 of earlier this year, blackjack is given a monumentality more appropriate to buildings slated for demolition: giant playing cards whoosh like Stealth fighters or topple like brick walls.

I’m not against such one-off bursts of imagery. There’s an undoubted wow factor in seeing spent bullet casings shower into our face in The Matrix.

I just ask: What do such images remind us of? My answer: Comic book panels, those graphically dynamic compositions that keep us turning the pages. In fact, we call such effects “cartoonish.” Here’s an example from Watchmen, where the slow-motion effect of the Smiley pin floating down toward us is sustained by a series of lines of dialogue from the funeral service.

With comic-book imagery showing up in non-comic-book movies, one source may be greater reliance on storyboards and animatics. Spfx demand intensive planning, so detailed storyboarding was a necessity. Once you’re planning shot by shot, why not create very fancy compositions in previsualization? Spielberg seems to me the live-action master of “storyboard cinema.” And of course storyboards look like comic-book pages.

The hambone factor. In the studio era, star acting ruled. A star carried her or his persona (literally, mask) from project to project. Parker Tyler once compared Hollywood star acting to a charade; we always recognized the person underneath the mime.

This is not to say that the stars were mannequins or dead meat. Rather, like a sculptor who reshapes a piece of wood, a star remolded the persona to the project. Cary Grant was always Cary Grant, with that implausible accent, but the Cary Grant of Only Angels Have Wings is not that of His Girl Friday or Suspicion or Notorious or Arsenic and Old Lace. Or compare Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve, Double Indemnity, and Meet John Doe. Young Mr. Lincoln is not the same character as Mr. Roberts, but both are recognizably Henry Fonda.

Dress them up as you like, but their bearing and especially their voices would always betray them. As Mr. Kralik in The Shop around the Corner, James Stewart talks like Mr. Smith on his way to Washington. In The Little Foxes, Herbert Marshall and Bette Davis sound about as southern as I do.

Star acting persisted into the 1960s, with Fonda, Stewart, Wayne, Crawford, and other granitic survivors of the studio era finishing out their careers. Star acting continues in what scholar Steve Seidman has called “comedian comedy,” from Jerry Lewis to Adam Sandler and Jack Black. Their characters are usually the same guy, again. Arguably some women, like Sandra Bullock and Ashlee Judd, also continued the tradition.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

Horror and comic-book movies offer ripe opportunities for this sort of masquerade. In a straight drama, confined by realism, you usually can’t go over the top, but given the role of Hannibal Lector, there is no top. The awesome villain is a playground for the virtuoso, or the virtuoso in training. You can overplay, underplay, or over-underplay. You can also shift registers with no warning, as when hambone supreme Orson Welles would switch from a whisper to a bellow. More often now we get the flip from menace to gargoylish humor. Jack Nicholson’s “Heeere’s Johnny” in The Shining is iconic in this respect. In classic Hollywood, humor was used to strengthen sentiment, but now it’s used to dilute violence.

Such is the range we find in The Dark Knight. True, some players turn in fairly low-key work. Morgan Freeman plays Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine does his usual punctilious job, and Gary Oldman seems to have stumbled in from an ordinary crime film. Maggie Gylenhaal and Aaron Eckhart provide a degree of normality by only slightly overplaying; even after Harvey Dent’s fiery makeover Eckhart treats the role as no occasion for theatrics.

All else is Guignol. The Joker’s darting eyes, waggling brows, chortles, and restless licking of his lips send every bit of dialogue Special Delivery. Ledger’s performance has been much praised, but what would count as a bad line reading here? The part seems designed for scenery-chewing. By contrast, poor Bale has little to work with. As Bruce Wayne, he must be stiff as a plank, kissing Rachel while keeping one hand suavely tucked in his pocket, GQ style. In his Bat-cowl, he’s missing as much acreage of his face as Dent is, so all Bale has is the voice, over-underplayed as a hoarse bark.

In sum, our principals are sweating through their scenes. You get no strokes for making it look easy, but if you work really hard you might get an Oscar.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

But of course the caricaturists got here first, from Hogarth and Daumier onward. Most memorably, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy strip offered a parade of mutilated villains like Flattop, the Brow, the Mole, and the Blank, a gentleman who was literally defaced. The Batman comics followed Gould in giving the protagonist an array of adversaries who would even raise an eyebrow in a Manhattan subway car.

Eisenstein once argued that horrific grotesquerie was unstable and hard to sustain. He thought that it teetered between the comic-grotesque and the pathetic-grotesque. That’s the difference, I suppose, between Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands, or between the Joker and Harvey Dent. In any case, in all its guises the grotesque is available to our comic-book pictures, and it plays nicely into the oversize acting style that’s coming into favor.

You’re thinking that I’ve gone on way too long, and you’re right. Yet I can’t withhold two more quickies:

The global recognition of anime and Hong Kong swordplay films. During the climactic battle between Iron Man 2.0 and 3.0, so reminiscent of Transformers, I thought: “The mecha look has won.”

Learning to love the dark. That is, filmmakers’ current belief that “dark” themes, carried by monochrome cinematography, somehow carry more prestige than light ones in a wide palette. This parallels comics’ urge for legitimacy by treating serious subjects in somber hues, especially in graphic novels.

Time to stop! This is, after all, just a list of causes and conditions that occurred to me after my day in the multiplex. I’m sure we can find others. Still, factors like these seem to me more precise and proximate causes for the surge in comic-book films than a vague sense that we need these heroes now. These heroes have been around for fifty years, so in some sense they’ve always been needed, and somebody may still need them. The major media companies, for sure. Gazillions of fans, apparently. Me, not so much. But after Hellboy II: The Golden Army I live in hope.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell for information about the history of the comics market.

The superhero rankings I mentioned are: Spider-Man 3 (no. 12), Spider-Man (no. 17), Spider-Man 2 (no. 23), The Dark Knight (currently at no. 29, but that will change), Men in Black (no. 42), Iron Man (no. 45), X-Men: The Last Stand (no. 75), 300 (no. 80), Men in Black II (no. 85), Batman (no. 95), and X2: X-Men United (no. 98). The usual caveat applies: This list is based on unadjusted grosses and so favors recent titles, because of inflation and the increased ticket prices. If you adjust for these factors, the list of 100 all-time top grossers includes seven comics titles, with the highest-ranking one being Spider-Man, at no. 33.

For a thoughtful essay written just as the trend was starting, see Ken Tucker’s 2000 Entertainment Weekly piece, “Caped Fears.” It’s incompletely available here.

Comics aficionados may object that I am obviously against comics as a whole. True, I have little interest in superhero comic books. As a boy I read the DC titles, but I preferred Mad, Archie, Uncle Scrooge, and Little Lulu. In high school and college I missed the whole Marvel revolution and never caught up. Like everybody else in the 1980s I read The Dark Knight Returns, but I preferred Watchmen (and I look forward to the movie). I like the Hellboy movies too. But I’m not gripped by many of the newest trends in comics. Sin City strikes me as a fastidious piece of draftsmanship exercised on formulaic material, as if Mickey Spillane were rewritten by Nicholson Baker. Since the 80s my tastes have run to Ware, Clowes, a few manga, and especially Eurocomics derived from the clear-line tradition (Chaland, Floc’h, Swarte, etc.). I believe that McCay and Herriman are major twentieth-century artists, with Chester Gould and Cliff Sterrett worth considering for the honor too.

You can argue that Oliver Stone’s films create ambivalence inadvertently. JFK seems to have a clear-cut message, but the plotting is diverted by so many conspiracy scenarios that the viewer might get confused about what exactly Stone is claiming really happened.

On the ways that worldmaking replaces character-centered media storytelling, the crucial discussion is in Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York University Press, 2007), 113-122.

On franchise-building, see the detailed account in detail in Eileen R. Meehan, “‘Holy Commodity Fetish, Batman!’: The Political Economy of a Commercial Intertext,” in The Many Lives of the Batman, ed. Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (Routledge, 1991), 47-65. Other essays in this collection offer information on the strategies of franchise-building.

Just as Star Wars helped legitimate itself by including Alec Guinness in its cast (surely he wouldn’t be in a potboiler), several superhero movies have a proclivity for including a touch of British class: McKellan and Stewart in X-Men, Caine in the Batman series. These old reliables like to keep busy and earn a spot of cash.

PS: 21 August 2008: This post has gotten some intriguing responses, both on the Internets and in correspondence with me, so I’m adding a few here.

Jim Emerson elaborated on the zeitgeist motif in an entry at Scanners. At Crooked Timber, John Holbo examines how much the film’s dark cast owes to the 1990s reincarnation of Batman. Peter Coogan writes to tell me that he makes a narrower version of the zeitgeist argument in relation to superheroes in Chapter 10 of his book, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, to be reprinted next year. Even the more moderate form he proposes doesn’t convince me, I’m afraid, but the book ought to be of value to readers interested in the genre.

From Stew Fyfe comes a letter offering some corrections and qualifications.

*Stew points out that chain stores like Borders do sell some periodical comics titles, though not always regularly.

*Comics publishing, while not at the circulation levels seen in the golden era, is undergoing something of a resurgence now, possibly because of the success of the franchise movies. Watchmen sales alone will be a big bump in anticipation of the movie.

*As for my claim that film is driving the publishing side, Stew suggests that the relations between the media are more complicated. The idea that the tail wags the dog might apply to DC, but Marvel has made efforts to diversify the relations between the books and the films.

They’ve done things like replacing the Hulk with a red, articulate version of the character just before the movie came out (which is odd because if there’s one thing that the general public knows about the character is that he’s green and he grunts). They’ve also handed the Hulk’s main title over to a minor character, Hercules. They’ve spent a year turning Iron Man, in the main continuity, into something of a techno-fascist (if lately a repentant one) who locks up other superheroes.

Stew speculates that Marvel is trying to multiply its audiences. It relies on its main “continuity books” to serve the fanbase who patronizes the shops, and the films sustain each title’s proprietary look and feel. In addition, some of the books offer fresh material for anyone who might want to buy the comic after seeing the film; this tactic includes reprinted material and rebooted continuity lines in the Ultimate series. Marvel has also brought in film and TV creators as writers (Joss Whedon, Kevin Smith), while occasionally comics artists work in TV shows like Heroes, Lost, and Battlestar Galactica. So the connections are more complex than I was indicating.

Thanks to all these readers for their comments.

Comic-Con 2008, Part 2: Why Hollywood cares

Kristin here-

You can’t picture the typical reader of Variety or the New York Times picking up the latest issue of Superman at the local comics shop. So why is Comic-Con, the annual confab of fans from around the world, gathering so much interest from both mainstream media and the trade press?

The obvious answer is that a growing number of megapictures and TV series are derived from superhero comics and, more broadly, fantasy and science-fiction literature. The chance to see stars and directors on panels, the first look at preview clips–these draw both fans and entertainment reporters.

Recently, the press is suggesting that Hollywood’s presence is becoming dominant at this gathering of self-professed geeks. After going to my first Comic-Con last month, I’m thinking that something else is going on. First, it’s not clear that Hollywood rules the Con. Second, and more interesting, is the question of exactly how Hollywood benefits from being there–or indeed, whether it benefits at all.

Hollywood vs. comics

Michael Cieply’s July 25 article in the New York Times is entitled, “Comic-Con Brings Out the Stars, and Plugs for Movies.” To read it, you would think that Comic-Con is a purely film event. Cieply Refers to Hugh Jackman promoting X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Mark Wahlberg presenting clips from Max Payne, the cast and director of Twilight addressing a squealing crowd of young female fans, and so on. Nary a mention of comics, video games, action figures, collectibles, original artworks, and other items being sold or promoted in the vast exhibition hall, let alone the numerous simultaneous panels going on all day upstairs and the long, sinuous lines of fans awaiting their turn for autographs from artists.

Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Geoff Boucher started his July 28 story, “This is the year they tried to take the comic out of Comic-Con.” The piece is entitled “Comic books overshadowed by the embrace of Hollywood.” A reporter could probably find plenty of people at Comic-Con to deplore the decline of comics’ representation at the event and an equal number to say that the non-Hollywood part of Comic-Con is alive and well.

Boucher quotes two of the former, who tend to be people who have been attending Comic-Con and other such events for decades. Michael Uslan, a comic-book author in the 1970s and now the executive producer of, among others, The Dark Knight, declares, “I think Comic-Con is in danger of having Hollywood co-opt its soul. It’s turning into something new, and you could really see it this year.” Robert Beerbohm, who has sold comics at every Comic-Con since it was first held in 1970, also worries about the trend: “All the Hollywood directors say that they loved comics as a kid, but now they [i.e., the comics] are being pushed off the floor. Where are the next generation of directors going to come from?”

I tend to think that young directors get influenced by such a diverse mix of popular and high cultural works that the putative lack of comics at Comic-Con won’t make much difference. Plus these days the “comics” are often graphic novels, readily available to any future director from big bookstore chains and internet sources.

Avoiding Hall H

Comic-Con has grown hugely over its nearly four decades of existence, and other media have crept in slowly. Hollywood has been prominently represented for years now. Peter Jackson promoted The Lord of the Rings there, and Adrien Brody and Naomi Watts showed up to promote his King Kong. But somehow this year the journalistic zeitgeist seems to have dictated that most writers choose to stress that Hollywood is in danger of taking over the con. Well, it makes for a dramatic story premise.

Admittedly, I’m a Comic-Con newbie. I’m sure to the old hands the creeping presence of films and TV is noticeable and perhaps worrisome. To me the big Hollywood previews were something you had to seek out, and they weren’t that easy to get to. As I mentioned in my first blog on the subject, the ground floor of the enormous, lengthy building is divided into halls A to H. A to G formed one vast open space, and an attendee could trek from one end to the other without going through doors or lobbies. Hall H, where most of the biggest Hollywood previews and panels took place, was entered from a separate door on the outside of the building. The lines to get in snaked in the opposite direction from doors A to G. Entering and exiting the exhibition hall’s lobby through one of those doors, you might not even notice the lines.

The other big “Hollywood” space is Ballroom 20, on the second floor. Anyone going from one part of the building to the other on this level, on the way to the panel rooms or the autograph area, would be likely to pass it.

My sole Hall H experience came when I attended the Terminator Salvation and Pixar previews on Saturday afternoon. The rest of my time at Comic-Con bore no resemblance to what the news stories describe. Apart from Hall H, I moved extensively around the exhibition hall, the various hallways between the panel rooms, through the “sails pavilion” and along the main lobby without having any sense of the big film and television events going on. I occasionally passed Ballroom 20 when there was a long line outside, but even then there was seldom any indication of what the people were waiting for—no banners or posters. (In general, Comic-Con has sold only very limited “signage” outside the exhibition hall. The upstairs hallways outside the panel doors were unadorned apart from small schedule boards.) In the exhibition hall I saw the studio logos hanging above their exhibit spaces and learned to skirt around them to avoid the particularly dense crowds in that area—but it was one area among many in that giant space. I seem to have experienced a different Con from the one widely reported on.

I’m not alone in thinking that Comic-Con is a giant, diverse event that simply has a big Hollywood screening room next door for those who are interested. Marc Graser, who wrote several pieces on this year’s Con for Variety, talked with its PR director, David Glanzer:

“Not every studio has a presentation every year,” Glanzer says. “It’s not an earth-shattering event. Sometimes people read too much into it.”

Yet the irony in all of this is that film- and TV-specific programming makes up less than 25% of the Con’s schedule, Glanzer says. And even on the event’s show floor, studios are overshadowed by comicbook publishers, retailers, videogames and toy companies.

The rest of the panels are educational sessions on how to break into the comicbook biz, for example, that allow Comic-Con to consider itself an educational nonprofit.

In other sources, Glanzer gives the more specific figure for film- and TV-related programming as 22%.

Those educational sessions for budding comic-book creators do make up quite a share of the program. These aren’t just how-to-draw lessons. There was a panel, “Comic Book Law School Afternoon Special: Gone But Not Forgotten!” dealing with intellectual property rights and others on the practicalities of the business. There were also 50-minute “Spotlight” sessions devoted to individual artists like Ralph Bakshi and Lynda Barry. The Eisner Awards ceremony celebrated accomplishment in the comics world.

Camping in Hall H

Why do journalists covering Comic-Con tend to stress Hollywood so much? I assume because the previews and panels are where the big stars are. They and their forthcoming films are the big news, the buzz that makes it worthwhile for magazines, newspapers, and blogs to spend the money to send their reporters or hire free-lancers. Most reporters experience that other “Hall H” con that I only visited once. I saw Anne Thompson at the “Masters of the Web” panel on Thursday morning, and she duly blogged about it. Still, most of the many Comic-Con stories posted on her Variety blog by her and other reporters were on the films and TV shows.

And why not? The big entertainment reporters get access to the major talent for short interviews, and their photographers can get up close for glamorous shots to use as illustrations. That’s no doubt what the largest portion of their readership or viewership is interested in. Attending the Con is an efficient way of generating a lot of copy.

Nevertheless, it doesn’t hurt to note that Hall H seats 6500 people, dozens, perhaps hundreds of them the entertainment reporters and bloggers. That’s out of 125,000 attendees who bought passes and probably tens of thousands more who were exhibitors, “booth babes,” or panel presenters. Granted, people circulated in and out of Hall H, though my impression is that some people stayed there much of the time. If sheer numbers of fans were to determine news coverage, the other facets of Comic-Con would get more attention than they do. But it’s the stars.

What’s in it for the studios?

The answer to that question might seem self-evident: publicity, and lots of it. The situation fuels itself. As more reporters from bigger outlets come to Comic-Con, the studios get more valuable publicity at a relatively small cost. (USA Today’s July 28 wrap-up occupied nearly a page and a half of the print edition.) And as more studios send previews and big stars, more news sources will find it worth sending their main reporters. In fact, perhaps this year the situation reached saturation. Hollywood studios filled all the possible slots in the two large halls, and in some cases big news outlets sent teams of reporters. That might be what gave both studio execs and reporters the impression that Hollywood is steamrolling the rest of the Con.

Publicity is all very well, but in the August 1 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, Steven Zeitchik questions whether it’s really worth all the fuss to preach to the converted. He notes the growth of the big studios’ efforts to impress fans: “On its face, this shouldn’t be the case. A brand’s cult following isn’t a very large number, and it’s also a group already inclined to like and spend money on a product, which by most marketing logic is exactly the group you should spend the fewest resources on.”

Sure, the Comic-Con previews may impress fans who are assumed to be tastemakers, particularly in the blogosphere. Zeitchik comments, “And if the tastemaker effect doesn’t happen, the strategy loses its teeth. One director who’s had repeated visits to Comic-Con noted just before he went to this year’s convention that ‘The total number of people in the blog world is probably only a few hundred thousand, and as much as they might hate to hear it, for most movies that’s not going to make the difference between a success and a failure.’” Zeitchik points out that the Speed Racer preview at the 2007 Con was cheered, but that didn’t mean that a lot of fans bought tickets to the film itself. The wider public stayed away.

Yet surely the studio suits know all this, and they keep providing glimpses of films and series to come. What other advantages do they perceive?

A Comic-Con preview can be a chance not only to woo fans but to get clues that might help in the general publicity campaign. Focus Features president James Shamus, who previewed Hamlet 2 at Comic-Con this year, views the process as a chance to get instantaneous feedback that might help later in promoting a film: “It’s the start of an ongoing dialog. It doesn’t just start and end there. It’s not a thumbs up or thumbs down because some guy didn’t like your poster.”

Many studio executives also still believe in the viral quality of fan buzz on the internet. Lisa Greogorian, the executive vice-president of marketing for Warner Bros. Television, assesses past years’ previews of Chuck, Pushing Daisies, and The Sarah Connor Chronicles: “We saw an immediate impact online. Word of mouth is now one individual impacting a couple hundred individuals who can impact thousands. Social networking has allowed us to empower one fan to impact thousands of potential viewers.” (Both executives spoke to Marc Graser for a July 11 Comic-Con preview in Variety.)

I emailed James, who is an old friend of ours, about the subject. He pointed out that while the blockbusters may have a pre-sold audience, smaller films like Shaun of the Dead can create momentum at Comic-Con. Moreover, there are a lot of blogs out there now, and studios monitor the more important ones to help shape their own publicity efforts.

A Comic-Con presence often, however, is not simply a matter of persuading fans to watch a film or TV series. Sometimes major negative buzz began to surround a film from a few bad online comments based solely on the Con previews. Wooing the fans with stars and footage can be a way to prevent that negativity from getting started—or a big reason for some studios not to preview a film at the Con.

One factor that doesn’t get mentioned in the press coverage of why the Hollywood studios bother with Comic-Con previews is that this event in effect provides them with huge, low-cost press junkets.

The modern press junket for a tentpole film is typically an expensive affair. The studio pays for dozens, maybe hundreds of reporters to travel to a single spot. It may be as bland as a rented hotel conference room, or it may be set in some more picturesque locale. At Cannes in 2001, New Line held a big junket for The Lord of the Rings at a hillside chateau with a spectacular view. Other junkets might be on-set, at a studio where the film is still shooting. The studios have to shell out for the reporters’ hotels, give them a per diem, and supply a reasonably impressive swag-bag. And there isn’t just one junket, but several in the course of publicizing a major release.

With Comic-Con, the studios have a whole bevy of reporters, many of them famous names in their own right, delivered to them at their employers’ expense. There are rows up front in Hall H reserved for them They sit through preview session after preview session for four days and generate a huge amount of publicity. Certainly there are expenses involved for the studios, but cutting together a few scenes or a random collection of finished shots together with a temp music track doesn’t cost a lot, and the actors don’t get paid extra for their publicity appearances. Transportation might be a relatively simple matter of sending whatever stars happen to be in Los Angeles in a limo down to San Diego. James specified to me that Comic-Con is “a very cost-effective” way of bringing the talent from a film together with fans to gauge how they interact.

I suppose for the reporters, the chance to attend what is in effect a whole passel of press junkets in one stretch saves a lot of time on airplanes.

Oh, yes, the comics

Some stories do stress the comics. Not surprisingly, Publisher’s Weekly printed an excellent preview that talked about the comics and graphic-novels companies that would be present. The author also pointed out that the connections between comics and films are getting closer, what with all the adaptations that have been made or are in the pipeline. The article quotes comics author Steve Niles (30 Days of Night) as saying, that the Con is “crawling with producers now, which means some of the up-and-comers have a chance to get someone to notice their book.”

USA Today ran a story that analyzed the recent trend toward comics-based movies quite carefully. Author Scott Bowles discusses the trends toward darker stories and heroes who aren’t conventional heroic, such as Hancock and the Watchmen. The story also discusses whether this trend indicates that the superhero genre is nearly over or just reaching a more imaginative stage.

Bowles also points out that the traditional notion of the Con as largely frequented by fanboys is no longer accurate. This year nearly 40% of the fans were female.

Costumes and the press

Naturally journalists with cameras make a beeline for costumed Comic-Con attendees. They stand out in the crowd, they seem to these journalists to epitomize the fan sensibility, and they are delighted to pose at any length for photos. (Anne Thompson’s blog has a sampling posted.) Many of them have very impressive costumes and put on little skits or tableaux in the hallways. There’s a “masquerade” competition with cash (up to $150) and merchandise prizes on Saturday night.

[Added August 11: David Glanzer kindly emailed me to compliment me on this entry. He informed me that roughly one percent of fans attending Comic-Con come in costume. Not that either he or I have anything against costumed fans. On the contrary, I enjoyed seeing them, and obviously they were having a terrific time. But some journalists adopt a definitely mocking tone, and even those who are respectful tend to mislead the public about the attendees at the Con in general.]

But most attendees are content to declare their interests on their T-shirts, as I did, and their shopping bags. Again, that doesn’t make for good copy or images. The photos at top and bottom show what I saw much of the time in the exhibition hall. These people are not likely to be approached by journalists, though these days they might have a questionnaire thrust into their hands by a sociologist or ethnographer trying to figure out what makes fans tick.

If you have to ask …

For my account of things and event relating to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at Comic-Con, see here.

Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends

DB here:

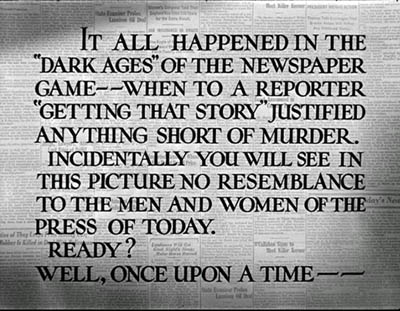

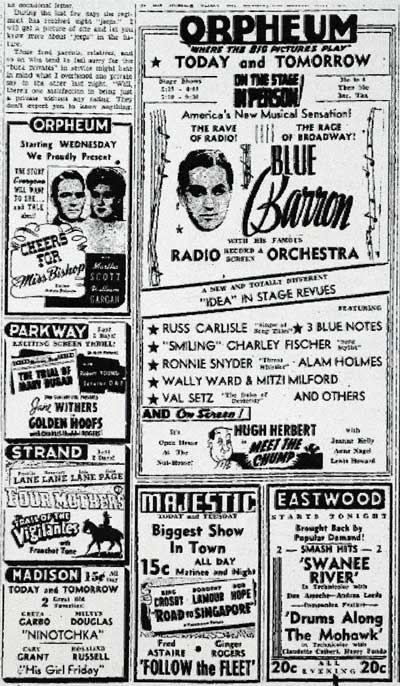

In early April of 1940, His Girl Friday came to Madison, Wisconsin. It ran opposite Juarez, The Light that Failed, Of Mice and Men, and a re-release of Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Pinocchio was about to open. Most screenings cost fifteen cents, or $2.21 in today’s currency.

Before television and home video, film was a disposable art. Except in big cities, a movie typically played a town for a few days. Programs changed two or three times a week, and double bills assured the public a spate of movies—nearly 700 in 1940 alone. People responded, going to the theatres on average 32 times per year. Given the competition, it’s no surprise that His Girl Friday didn’t stand out in the field; it was nominated for no Academy Awards and honored by no prizes. On just a single day in Madison, the cast of His Girl Friday was up against icons like Muni, Colman, March, and Bette Davis.

Nowadays, of course, nearly everyone regards HGF as one of the great accomplishments of the studio system. Most would consider it a better movie than any of the others it played opposite in my home town. A typical example of critical exuberance is Jim Emerson’s comment here. Or read James Harvey’s 1987 encomium:

It would be hard to overstate, I think, the boldness and brilliance of what Hawks has done here: not only an astonishingly funny comedy, but a fulfillment of a whole tradition of comedy—the ur-text of the tough comedy appropriated fully and seamlessly to the spirit and style of screwball romance. His Girl Friday is not only a triumph, but a revelation.

Oddly, this extraordinary film lay largely unnoticed for three decades. How did it become a classic? The answer has partly to do with the rising status of Howard Hawks, the director, among critics. It also owes something to changes in how academics thought about film history. And a little movie piracy didn’t hurt.

An unseen power watches over the Morning Post

Hawks the Artist is a creation of the 1960s. Before that, American film historians almost completely ignored him. Andrew Sarris often reminds us that he’s absent from Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1939), but he’s also missing from Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957), the most popular survey history of its day. Apart from press releases and reviews of individual films, there were few discussions of Hawks in American newspapers and magazines. The most famous piece is probably Manny Farber’s “Underground Movies” of 1957, which treats Hawks along with other hard-boiled directors like Wellman and Mann.

From the start, Hawks was more appreciated in France. There film historians acknowledged A Girl in Every Port (1928), in part because of the presence of Louise Brooks, and they usually flagged Scarface (1932) as well, which they could see and Americans couldn’t. (Howard Hughes kept it out of circulation for decades.) But Hawks is barely mentioned in Georges Sadoul’s one-volume Histoire du cinéma mondiale (orig. 1949) and he’s ignored in the 1939-1945 volume of René Jeanne and Charles Ford’s monumentally monotonous Histoire encyclopédique du cinéma (1958).

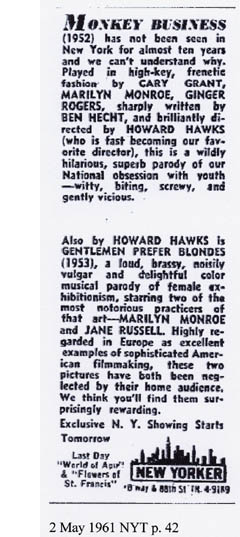

The essay that marked the first phase of reevaulation was evidently Jacques Rivette’s “The Genius of Howard Hawks” in Cahiers du cinéma in 1953. Inspired by Monkey Business, Rivette’s philosophical flights and you-see-it-or-you-don’t tone helped define the auteur tactics identified with Cahiers’s young Turks. Rivette and his colleagues became known as “Hitchcocko-Hawksians.” The essay, however, doesn’t seem to have been immediately influential. Antoine de Baecque claims that within Cahiers, an admiration for Hawks was controversial in a way that liking Hitchcock was not. (1) It took some years for Hawks to ascend to the Pantheon.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

For the MoMA retrospective, Hawks granted Bogdanovich a monograph-length interview, which was to be endlessly reprinted and quoted in the years to come. (2) Sarris, now knowing who the hell Hawks was, wrote a career overview for the little magazine, The New York Film Bulletin, and this piece became a two-part essay in the British journal Films and Filming. Both Bogdanovich and Sarris made brief reference to His Girl Friday, as did Peter John Dyer in another 1962 essay, this one for Sight and Sound. At the end of 1962, another British magazine, Movie, published an issue on Hawks. At the start of 1963, Cahiers devoted an issue to him, including an homage by Langlois himself. Thanks to the work of Archer, Bogdanovich, Sarris, and MoMA, Hawks was rediscovered.

Sarris provided a condensed case for Hawks in his far-reaching catalogue of American directors, published as an entire issue of Film Culture in spring of 1963. There followed an interview with Hawks’s female performers in the California journal Cinema (late 1963), an appreciation by Lee Russell (aka Peter Wollen) in New Left Review (1964), another Cahiers issue (November 1964), J. C. Missiaen’s slim French volume Howard Hawks (1966), Robin Wood’s Howard Hawks (1968), and Manny Farber’s Artforum essay (1969). There were doubtless other publications and events that I never learned about or have forgotten. In any case, by the time I started grad school in 1970, if you were a film lover, you were clued in to Hawks, and you argued with the benighted souls who preferred Huston. . . even if you hadn’t seen His Girl Friday.

Light up with Hildy Johnson

One of my obsessions in graduate school was the close analysis of films. But I was also interested in whether one could build generalizations out of those analyses. My initial thinking ran along art-historical lines. My Ph. D. thesis on French Impressionist cinema sought to put the idea of a cinematic group style on a firmer footing, through close description and the tagging of characteristic techniques. But that approach came to seem superficial. I wasn’t satisfied with my dissertation; although it probably captured the filmmakers’ shared conceptions and stylistic choices, I couldn’t offer a very dynamic or principled account of formal continuity or change.

Watch a bunch of movies. Can you disengage not only recurring themes and techniques, but principles of construction that filmmakers seem to be following, if only by intuition? As I was finishing my dissertation, reading Russian Formalist literary theory pushed me toward the idea that artists accept, revise, or reject traditional systems of expression. These become tacit norms for what works on audiences. My reading of E. H. Gombrich pushed me further along this path. We should, I thought, be able to make explicit some of those norms. Eventually I would call this perspective a poetics of cinema.

I was assembling my own version of some ideas that were circulating at the time. In the early 1970s, several theorists floated the idea that different traditions fostered different approaches to filmic storytelling. People were seeing more experimental and “underground” work, as well as films from Asia and what was then called the Third World. Being exposed to such alternative traditions helped wake us up to the norms we took for granted. The mainstream movie, typified by what Godard called “Hollywood-Mosfilm,” seemed more and more an arbitrary construction.

People began examining films not as masterworks or as expressions of an auteur, but as instances of a representational regime. Films became “tutor-texts,” specimens of formal strategies that were at play across genres, studios, periods, and directors. Again, the French pointed the way, particularly Raymond Bellour, Thierry Kuntzel, and Marie-Claire Ropars. At the same moment, Barthes’ S/z was published in English, and it seemed to provide a model for how one might unpick the various strands of a text, either literary or cinematic. Screen magazine was a conduit for many of these ideas in the English-speaking world.

Some of my contemporaries disdained the mainstream cinema and moved toward experimental or engaged cinema. Others read the dominant cinema symptomatically, for the ways it revealed the contradictions of ideology. I learned from both approaches, but I believed that the current analysis of how Hollywood worked, even considered as a malevolent machine, was incomplete. Could we come up with a more comprehensive and nuanced account of the mainstream movie? This line of thinking was already apparent in non-evaluative studies of form and style, such as essays by Thomas Elsaesser, Marshall Deutelbaum, and Alan Williams. (3)

At some point in graduate school at the University of Iowa, between fall 1970 and spring 1973, I saw a screening of His Girl Friday. I fell in love with its heedless energy. It seemed to me a perfect example of what Hollywood could do.

In my admiration I was channeling the cultists. Rivette, in a review of Land of the Pharoahs: “Hawks incarnates the classical American cinema.” (4) Bogdanovich: He is “probably the most typical American director of all.” Richard Griffith, then film curator of MoMA, had slighted Hawks in his addendum to Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, but in his foreword to the Bogdanovich interview he caved to the younger generation: “Hawks works cleanly and simply in the classical American cinematic tradition, without appliquéd aesthetic curlicues.” As for HGF, in the 1963 Cahiers tribute Louis Marcorelles called it “the American film par excellence.”

Praising Hawks, and HGF specifically, was part of a larger Cahiers strategy to validate the sound cinema as fulfilling the mission of film as an art. What traditional critics would have considered theatrical and uncinematic in HGF—confinement to a few rooms, constant talk, an unassertive camera style—exactly fit the style that Bazin and his younger colleagues championed. (For more on that argument, see Chapter 3 of my On the History of Film Style.)