Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

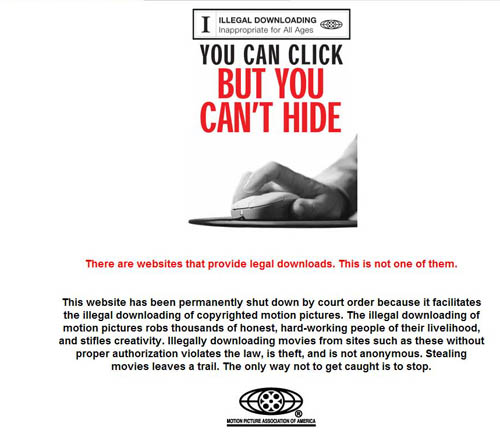

I was, and may still be, a spy for the MPAA

DB here:

The Motion Picture Association of America is the trade association of the major film production and distribution companies. Founded in 1922, it helped the Hollywood studios maintain their control of the US industry and foster its business abroad. (See Kristin’s book Exporting Entertainment for an explanation of how it worked.) In 1945 the MPAA split off its international efforts and created a subsidiary, the Motion Picture Export Association of America, which helped the majors move in a systematic way into world markets. The current MPAA members are the Big Six: Sony (Columbia), Buena Vista (Disney), Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., and Twentieth Century Fox.

About fifteen months ago, the MPAA created a survey called My Movie Muse. Reading about it in Variety, I eagerly signed up. Every three or four months My Muse contacts me and asks me to answer some questions. At the end of the survey, I’m told that my name has been entered in a drawing for a gift certificate from Amazon.

I’ve never won. I’ve never heard who did. Maybe I won and the MPAA forgot to tell me.

The Movie Muse survey started last year with 7500 participants. You can join us by going to the website.

The initiative, according to MPAA head Dan Glickman, enables moviegoers to tell the industry their concerns.

People want to have input. They want to know that their movie viewing experiences are worth their time and money, and they want to know that our industry is hearing their criticisms and demands. In this age of participatory media, My Movie Muse will give consumers an opportunity to be heard.

Unfortunately, we Musers have little opportunity to say anything that doesn’t fall into a narrow set of multiple-choice queries. Let’s take a little drive through the questions. Beware the speed bump.

Eyes on your own paper, buddy

Every Muse form I’ve filled out is essentially the same, with a few seasonal variants. (What is your favorite Halloween movie?) The Muse announces that some questions will be repeated every few months “so that we can see how your opinions change over time.” You could perhaps make the Muse happy providing different answers at each iteration of the survey.

The Muse’s first clutch of questions involves your opinion of movies in general. Do you like ‘em or dislike ‘em? Do you think they’re better than they were in the 1990s? How do they compare with other forms of entertainment, like TV shows, videogames, and music? Do you like indies, kid movies, dramas, comedies, animation, documentary, whatever? How often do you see movies in theatres, rent DVDs, buy DVDs, or watch a movie online? How do you like the moviegoing experience in your local theatre? And so on. This is all pretty banal and anodyne, though I can imagine a firm using these data to help back up production decisions. (“See? I told you nobody likes Westerns.”)

The Muse proffers the Don’t Know option often, sometimes to puzzling effect. Is Don’t know really an appropriate answer to statements like the following?

Movies are often a topic of conversation among my friends.

I like to watch my favorite movies over and over again.

I use a DVR, iPod, computer CD or DVD burner on a regular basis.

Sometimes the inquiry turns Borgesian. Here’s one statement:

Movie plots are more predictable than they used to be.

If you don’t know, they’re probably not more predictable, at least to you. Another question asks:

Did you know that some movie theaters offer programs for frequent moviegoers, where you can earn free popcorn, sodas, and movie tickets depending on how many times you go to the theater?

The options are: Yes/ No/ Don’t know. Presumably if you don’t know, you’ll answer No. But if you answer Don’t know, does that mean that you don’t know whether you know?

In any case, the speed bump comes up soon enough. Not to scare you, but maybe there’s some serious stuff ahead.

Don’t know what a slide rule is for

We’re eased into the hard questions gradually:

Are you aware of peer-to-peer file-sharing services that allow you to download full-length films or TV shows via the Internet for free?

Again we get Don’t know as an option, which isn’t really viable. Try telling an interrogator allowed to use harsh measures, I don’t know if I’m aware of peer-to-peer file-sharing services. . . But now there’s another option: Prefer not to say. Good choice. Too bad it won’t come up again.

We’re asked how often we download purchased movies and TV shows, download bootleg material, buy bootleg DVDs, copy DVD files to hard drives, and receive CD or DVD copies from a friend. The Muse is also curious about how often you copy such material to disc for a friend, or for your personal use. The permitted answers range from Never to 4 or more times a month. This menu may need revising; I suspect some of my friends pursue these activities 4 or more times an hour.

Anyhow, it seems likely that nearly everybody between the ages of 4 and 50 has done at least one of these things. You’d prefer to say Prefer not to say, but the only evasive tactic is Don’t know.

You recall the Perry Mason trick: After the sweating witness has testified, Perry asks, “Are you aware of the penalties for perjury?” Something similar happens here. Once the Muse establishes that you’ve surely broken the law, with relentless prosecutorial logic it asks if you did so willfully. Getting cozy in a Good Cop way, the Muse acquires a singular personal pronoun:

For each of the following activities, please tell me whether you think they are legal or illegal:

Copy a movie or TV show on a CD or DVD to give to someone else.

Go to a website and download a TV show you paid for.

Go to a website and download a full-length movie you paid for.

Copy files from DVDs onto your hard drive.

Buy a bootleg DVD.

Go to a file-sharing site and download a TV show for free.

Receive a copy of a movie or a TV show on a CD or DVD for your own use—to watch whenever you want.

But the statements are too bald and inexact. These activities aren’t necessarily illegal, according to intellectual property attorney Jim Peterson:

The work might be in the public domain (too old, registration or renewal failure) or it might be a fair use. You could conceivably download a movie as a fair use for your own scholarship without violating the DMCA prohibitions on defeating copy protection or removing copyright management information. The guy who cracked the copy protection on the DVD probably has some Digital Millennium Copyright Act problems, though. Same thing with buying a bootleg DVD. I don’t think buying is illegal; it’s selling that’s the problem.

Since the Muse’s questions don’t allow for such nuances, once more the Don’t know option is looking mighty attractive.

My Muse goes on to ask if any of the following considerations would affect your decision to undertake the illegal activities you’ve already mentioned. Now if you thought that they were all legal, or if you answered Don’t know, then presumably you don’t have to reply to what follows. In any case, imagine Penn Gillette reciting each of these possibilities in his most explosively disrespectful voice, with expletives freely inserted. Would you avoid breaking the law . . .

If official DVDs were $5 cheaper?

If tickets for the movie theater were $2 cheaper?

If a portion of the DVD price was contributed to charity?

If you were concerned that buying and downloading unofficial copies was tied to criminal activities or terrorism?

If friends or somebody in your community were being prosecuted for a similar activity?

If you received a notice warning you that you might be prosecuted?

If you got off with a wrist slap and a threat of future surveillance?

If you were made an example in order to deter other scum?

If specially-made DVDs carried an electrical charge of 50,000 volts to be shot into a user when s/he sought to copy them?

If certain DVDs were sprayed with microbes carrying sexually transmitted diseases?

Granted, I made up some of these, but maybe you can’t tell which ones. Anyhow, the correct answer is Don’t know, said quickly ten times with your hands over your ears.

Suppose you say you don’t download movies illegally. Then My Muse, not one to back off, asks why you don’t break the law. The lengthy set of options includes such noble justifications as I don’t have the time, I don’t know how to do it, I don’t like to watch movies at my computer, It takes too long, and I wouldn’t get the DVD bonus materials. For such freedoms brave men died.

The replies It is illegal and I’m afraid of getting prosecuted and sued come at the very end. Correct answer: Oh, riiight . . . It’s illegal. Sure . . . that’s it . . . Illegal. Of course, if the purpose of the questionnaire is not to find out what we think but to tell us what to think, then these questions come at the right moment. They tacitly say: All of the above-mentioned things you are doing, or are now thinking about doing, can be punished by lawsuits and a stay in the Big House.

The last page offers you a list of legal movie download sites, asking if you recognize or use any of them. I recognized most, but Guba and Vongo were new names to me. I don’t think I could bring myself to use any service, even for roto-rooting purposes, called Guba or Vongo.

Just as you’re ready to pack your toothbrush for the holding tank, the Muse gives a cheery farewell. “That’s it! . . .You’re done!”

When My Muse went online last year, industry observers noticed right away that the survey seemed more about selling people the MPAA’s line on copyright than about getting their responses. Anthony Kaufman, one of the dueling cavaliers of the cineblogosphere, wrote:

The leading questions are clearly part of a larger MPAA struggle to bolster copyright initiatives and crack down on fair use, file sharing and anything that threatens the bottom line of the international conglomerates. Dan Glickman may be the kinder, gentler face of the MPAA in the wake of Jack Valenti’s exit, but if his demeanor is softer, his goals are still just as nefarious.

This is a plausible interpretation. But I don’t want to rule out the possibility that the studios might really listen to my write-in request that they upgrade release prints and stick with 35mm instead of going digital. Or maybe the MPAA is branching out into online entertainment, like those commercials, quizzes, and snack-bar plugs that come up before the trailers. Is My Movie Muse a trial balloon for a new feature, DRM: Be Very Afraid?

Don’t know, Don’t know, Don’t know.

I’m not holding my breath for my Amazon certificate either.

Crix Nix Variety’s Tics

Kristin here–

Today Anne Thompson’s blog contains a short entry linking to an “acerbic Brit Blogger” who has objected to the language used in Variety. The writer in question is Ronald Bergan, whose title sums up his claim: “It’s time Variety started speaking English.”

Bergan acknowledges that Variety is the best source of news on film, film festivals, and reviews. (The journal also covers TV and theater, as well as occasionally music and videogames.) But, he adds, “Pity then that it is unreadable.” Bergan attributes the cause to “Varietyese.” “Sticks Nix Hick Pix,” which he cites from the 1930s, is the sort of joke that has “now worn thin.”

Bergan also quotes a passage rife with what Variety itself terms “slanguage”: “The rookie self-distribbed indie pic, helmed and lensed by Alan Smithee, is geared for upscale fest auds and urban markets, particularly in Euro zones west and east. But the protags are too high-hat for wider BO appeal. Most perfs are boffo and tech contributions are on the money.” His opinion is that “This sort of writing not only degrades film criticism and demeans reviewers but debases the English language.”

Thompson, unfazed, responds, “I enjoy throwing around slanguage like prexy, helmer, boffo and pics with legs. They’re ingrained in my brain. What’s not to like?”

What, indeed? Anne, there’s plenty of mitting for your position, despite a few sour comments agreeing with Bergan that have been posted in response to your entry. As you point out, the heavier use of terms that might be unfamiliar to many comes in the print versions of Variety. The website, available to a broader public, tones them down distinctly. Given how much it costs to subscribe to the print edition, presumably mostly industry insiders (and some film historians) are reading it. Speaking as one who looks forward to the arrival of Variety every week and reads the film parts immediately, I enjoy its distinctive prose.

I occasionally run across a slanguage term I don’t recognize. Usually they’re pretty easy to figure out. As a hypothetical headline, “Thesp Ankles Ten-percenter” is a little odd, but couldn’t a reader figure out that an actor has left his or her agent? OK, it’s a little obscure, but I for one find it charming rather than annoying. And if I can’t figure a term out, I can check Variety‘s online slanguage dictionary.

Indeed, I’d like to suggest that slanguage is only one element in a Variety style. It’s partly the breezy tone, whether slanguage is employed or not. It’s most evident in the headlines, which can draw upon a number of devices. I can think of at least three. These examples come from the October 22-28, 2007 print edition.

There’s rhyming, as most famously represented by “Sticks Nix Hick Pix.” Most aren’t that spectacular, but there’s the subtler “Studios try slower pace to kudos race.” (That’s for one of Thompson’s own stories.)

There is insistent alliteration, which is a pretty common tactic. Three instances: “Super-size Skeins Shrink Skeds”; “Brooks Book is Biz’s Bible”; and “Claques Click with Canucks.”

Finally, there’s the pun on a familiar title or phrase: “Puttin’ on the Snits.”

These are all fairly ordinary Varietyese. I wish I could remember some of the past titles that have made me laugh out loud. Glancing through my files, I could only find one of those, on a story concerning studio head Michael De Luca’s abrupt departure from New Line Cinema in early 2001 (above).

Dignified? No, but Variety covers the entertainment industries, and why should it not take on a little of the spirit of its subject?

When I was writing The Frodo Franchise, I wanted to make its style appealing. I wanted it to be clear that it wasn’t just an academic tome but one aimed at the general reader—especially fans of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Of course there are the standard tricks, such as starting chapters with an intriguing anecdote or with a surprising fact. It occurred to me that maybe I could lighten the tone with some amusing titles for the chapters and their subsections. What better model to follow than Variety?

I began to appreciate the challenges a Variety title-writer must face. In some cases I came up with some decent ones, falling into the three types I listed above—not that I thought about the categories while waiting for inspiration to strike. I’ve read the trades long enough to know what an authentic Varietyese title sounds like.

Rhyme: “Last Ditch for PJ Pitch” for the section where I talk about Peter Jackson’s presentation of his project to New Line head Bob Shaye.

Alliteration: The book title itself, and the chapter “Flying Billboards and FAQs.”

Puns on familiar phrases: “In the Darkness Spellbind Them,” on the release and success of the films, and my personal favorite, “Zaentz and Zaentz-ability,” on Miramax’s negotiations with producer Saul Zaentz for the Rings production rights. A zinger of a Variety headline should make you groan at the silliness and yet at the same time shake your head with admiration.

But I couldn’t think of such “headline” titles for every chapter and subsection. Many of them ended up being just plain and descriptive. Still, I tried in every case. It was fun.

That brings us back to the Bergan blog entry. He seems to believe that Variety’s writers are forced to write such stuff by their employers and ends his entry by urging them to “go on strike for more textual flexibility. I can see the headline now: Hax Nix Variety Lingo.”

The author presumably thinks that that headline typifies Varietyese, but it really doesn’t. It has no rhyme, no alliteration, no pun, and no slanguage words. Bergan just made up “hax” to echo the “Sticks” title quoted above. (Pretty insulting to Variety scribes, too.) I’ll never be good enough or quick enough at this to get a job at Variety. Still, I offer the title of this entry as more in the magazine’s true spirit.

Our first anniversary, with a note on the unexpected fruits of film piracy

DB here:

This blog started on 26 September 2006. During its first year, it has attracted over 400,000 pageloads, over a quarter of a million visitors, and over 50,000 returning visitors. We currently average about 1000 visitors a day. While this is small potatoes by the standards of mammoth websites, it’s far more than we expected when we started. We’re grateful to all those readers who sought us out or stumbled upon us, who Googled and Yahoo’d us, who linked and listed us, who sent us corrections and extra information. And we’re grateful to our web tsarina Meg Hamel who set this up and keeps things running smoothly.

In the last twelve months, we’ve posted about 200,000 words, or enough for two books. We’ve tried to make most entries as attentive to ideas and information as what we’d write for a print publication—if not a scholarly book, at least a mainstream article. Kristin and I think of our blog as a sort of column, published in a magazine we edit, with no length restrictions, no assigned topics, and as many pictures as we like. It’s been fun to write more informally than we usually do. We’ve also been able to call attention to regional and national cinemas (e.g., Hong Kong, Denmark, New Zealand) we think deserve more attention. We can also pursue topics that we couldn’t fit into larger research projects, like Kristin’s interest in the Lord of the Rings franchise and my curiosity about alien autopsies.

While the blog originally aimed to supplement Film Art: An Introduction, we think that the best way to do that is to keep reminding our readers that the world of film is dazzling in its diversity and unpredictability. One commentator said that our blog was aimed at students and nonspecialists, but we find that many professional film scholars and film journalists check on us. Perhaps that’s because we wander where we like, from very old films to recent films we see at multiplexes and festivals, and we propose ideas that could be considered more closely and researched more exactingly. One correspondent said that many of our entries could be the basis for research articles. Maybe, but we have more ideas than we can ever write up systematically, so off to the blog they have gone. In addition, we’ve sometimes used the blog to extend or supplement things we’ve published in books and articles.

Looking back at what we’ve done, I notice some recurrent themes.

*In keeping with the blog’s title, we emphasize film as an art form. More specifically, we’re especially interested in how structure and technique work together, which few blogs outside the industry do. For instance, most online critics have concentrated on praising or condemining The Brave One, and in rather general terms. If we wrote about it, we’d probably focus on the effects of its alternating points of view, its use of the four-part script structure, and its recourse to oddly rocking camera movements to convey Erica’s disorientation at crucial moments (and trace how those develop in patterned ways across the film). That is, we’d incline toward somewhat finer-grained analysis of cinematic storytelling, even if that means going shot by shot. If we want as well to make an evaluation of the film, as we sometimes do, we then have some concrete evidence to back it up.

*We also treat film art as tied to film commerce—both the mainstream industry and the less-acknowledged form of commerce known as film festivals. We’ve always believed that there isn’t necessarily a battle between film as an art form and “the business.” Much of our published work, including Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment and my work on Hong Kong film and contemporary Hollywood, as well as our collaboration with Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, tries to trace out ways in which funding affects the look and feel of the finished work. Money matters!

*We’re happy to find that a lot of filmmakers read and link us. One of the purposes of Film Art was to show how artistic expression in cinema is tied to practical decisions made by filmmakers; that’s why we begin the book with an overview of the process of film production. In our academic work as well, we’ve been more inclined than most scholars to interview filmmakers, to read technical journals, and to study how craft practices create artistic effects. We’ve developed friendly relations with Asian filmmakers like Johnnie To and American filmmakers like Mark Johnson and James Mangold. We’ll continue to discuss how technique, technology, and filmmaking traditions interact in cinematic expression.

*We’ve tried to deflate some clichés of mainstream film journalism. Writers of feature articles are pressed to hit deadlines and fill column inches, so they sometimes reiterate ideas that don’t rest on much evidence. Again and again we hear that sequels are crowding out quality films, action movies are terrible, people are no longer going to the movies, the industry is falling on hard times, audiences want escape, New Media are killing traditional media, indie films are worthwhile because they’re edgy, some day all movies will be available on the Internet, and so on. Too many writers fall back on received wisdom. If the coverage of film in the popular press is ever to be as solid as, say, science journalism or even the best arts journalism, writers have to be pushed to think more originally and skeptically.

*There’s the theme we might call the continuing presence of the past. I notice that many of our entries comment on a current event or topic by showing that it has parallels and precedents in earlier periods of film history. This isn’t, I hope, showoffishness or academic point-scoring or a bored conservatism. Often this historical awareness allows us to correct hype and nuance ideas. Yes, today’s cinema experiments with flashbacks and intersecting story lines; but these are formal strategies we find in earlier periods of filmmaking too. So the interesting questions become: How are today’s strategies different? Why do these traditions get reinvented now? What consequences do they yield in our current circumstances? Rather than celebrating apparent innovation, it’s more exciting to see how filmmakers connect to tradition, shaping it in ways that even they might not be aware of doing. We tend to see the present through a narrow window, but historical awareness widens and deepens the view.

We rethink our project from time to time. Regular readers will notice that we’ve just added a roll of Readers’ Favorite Entries, on the right. We’ve also talked about adding a podcast to the site. In any event, we look forward to another year of our little magazine, and we have a folder full of ideas that we hope will tantalize you.

I’m off to Vancouver to cover the festival, as I did a year ago. More information on its wonderful lineup is here. In the meantime, some dessert.

Piracy ahoy

In Shanghai a few years ago I visited a shop selling pirated DVDs. Two illegal titles caught my eye.

According to the Motion Picture Association of America, the trade association of the major Hollywood companies, all pirated editions have their origin in camcorder copies made during screenings. In other words, it’s those outlaw consumers ripping us off.

But a large part of piracy can be traced to people working inside the industry. A common source is the raft of DVD screeners sent out to Academy members during awards season. It has proven impossible to keep these discs from getting into the hands of pirates. Other bootleg copies come from inside the production and distribution companies. Famously, a copy of Bulletproof Monk surfaced in China before the final cut was made; it’s widely believed that an employee leaked it. With so many special-effects houses working on a film in postproduction, it’s not difficult for one keyboard jockey to upload a working copy to the Darknet. Hence all those time-coded versions of the Star Wars saga that made their way into eager fans’ hard drives.

Further evidence of this tendency comes from the first Shanghai DVD I examined, that of The Passion of the Christ, not then available legally anywhere. It was a curious copy. It was an auditorium version, as pirates call movies snagged during a screening. The color and resolution were poor, and the camera zoomed in during the credits to a 1.75 ratio, wrecking the anamorphic compositions and creating closer framings.

Poor as it was, the bootlegged disc lacked some of the usual problems. The image was stable and centered, with no sign of being filmed from a seat in the house. The sound wasn’t tinny or boomy, as it would be if it came from theatre speakers, but it was plagued with whistles and dropouts.

I concluded that this was a version made by a projectionist in off-hours. He or she had time to set up the camera on a tripod near the back of the house and record the whole film without distraction, using an iffy sound feed. But what was more puzzling was the fact that the print being screened had no subtitles.

So what I was seeing was an early version, before any subtitles had been put on. The projectionist wasn’t your local multiplex employee but someone in the postproduction process. In a way, however, this bootleg copy fulfills Mel’s dream. As the film began shooting Mel claimed:

Obviously, nobody wants to touch something filmed in two dead languages. They think I’m crazy, and maybe I am. But maybe I’m a genius. I want to show the film without subtitles. Hopefully, I’ll be able to transcend language barriers with visual storytelling. If I fail, I’ll put subtitles on it, though I don’t want to.

On the bootleg DVD you could add Chinese titles or barely comprehensible English ones. Of course once the official DVD version came out, you could turn all subs off, but for a moment the bootleg market had given us Mel’s vision pure.

The second DVD that caught my eye points up another unexpected consequence of piracy. The cover of the release is at the very top of today’s entry. What made me investigate was the fact that Michael Caine is listed as being in the movie twice (though with different Chinese characters giving “his” name). Even the eager young researcher of PCU, immersed in the oeuvres of Gene Hackman and Michael Caine, might want to add a paragraph about this movie.

The credits on the back of the package add to the confusion. They are for Disney’s The Kid, and the running time is listed at 2:49. (The Kid is only 104 min.) I later learned that The Kid is a default paste-in on many DVD backsides. Why reproduce several different credit lists when all that matters is the metamessage, “This is an American movie”? But if it’s a Disney film, why does the printing also provide the Universal logo and an R rating?

So I broke down and watched the movie. (Flawless copy, by the way.) It is Code 11-14, a 2001 TV movie by Jean de Segonzac (big clue on the cover). An LA cop is tracking a serial killer. The killer follows the cop and his family onto a passenger jet and terrorizes them. According to Hal Erickson’s All Movie Guide, CBS pulled it from the schedule in the wake of 9/11. It wasn’t broadcast until 2003. Code 11-14 stars David James Elliott, Nanci Chambers et al., but not Michael Caine.

These sorts of mind games are pleasant. It’s fun to be thrown off balance by guessing how the credits got scrambled (PhotoShop set to Random?) and why Mr. Caine is credited doubly. Is he twice as popular in China as any other actor?

But the strongest justification for the existence of this pirate copy seems to me the liner notes.

What you see on the cover above—England movie circles cluster animportant history for but moving—is but a foretaste of what you find on the back. I reproduce it word for word.

This large war movie, empty cluster in the movie circles elite of England but move, for re-appear their motherland atAn important history of the period of World War II but worker harder, the film to record theatrical breeze The space describes the German Nazi in 1910 got empty bomb British intensive metropolis, make England Lose miserably heavy, but also arose England people together enemy spirit to make Germany, in numerous Popular actor inside, exceed the gram. The boon of . The willing to thinks, the shares the drama more, play the cuckoldry of The jade of Susan then expresses romantic, in addition, the Lawrence the brilliant jazz in military tactics with, the plays the plays the heartless condition in hungry clap very sublime and lifelike.

Exactly. I rest my case.

PS 30 Sept: I should’ve realized there’d be a website devoted to maniacal pirate prose and pictures. Thanks to Stuart Ian Burns, I learn that you can find many more at a Flickr group called, logically, crappy DVD bootleg covers.

The magic number 30, give or take 4

David here–

When I was teaching, students often came to my office hours with variants of this question. “I want to direct Hollywood movies. When should I start trying to get into the industry?”

My answer usually ran this way:

Your prospects are almost nil. It’s tremendously unlikely that you will become a professional director. You may wind up in some other branch of the industry, though. In any case, start now. Aim for summer internships while you’re in school, and try to get a job in LA immediately after graduation—preferably through a friend, a relative, a relative of a friend, or a friend of a relative.

My answer still seems reasonable, but recently I’ve begun to wonder if it holds up across history. Suppose we refocus our goggles on the macro scale. At what ages do most Hollywood directors make their first feature? If we can come up with a solid answer, it would be one instance in which studying film history can have very practical consequences.

No country for old men

In any field, most people would expect to have their careers moving along by the time they hit their early thirties. But aspiring filmmakers may think that there’s a long period of preparation–working in a mailroom, sweating over screenplays–before they finally get to direct. Directing films is a top-of-the-heap role. Who would trust a young first-timer with a multimillion-dollar investment and authority over far more experienced performers and technicians?

Nearly everybody, actually.

Executives tend to be oldish and not fully aware of what the target movie audience likes. A few years ago a friend of mine, consulting for the studios, went to a meeting of suits and was told that all the new digital sampling and mixing software was purely an effort to steal music. He replied that there were legitimate creative uses of that technology. “For example?” one exec asked. My friend said, “Well, there’s Moby.” Nobody at the table knew who Moby was.

So hiring young people in touch with their peers’ tastes makes sense. Indeed, many of today’s top filmmakers started making features quite young. I haven’t made an exhaustive survey, but picking directors more or less at random yields some pretty interesting results.

Note: It’s hard to know how long a movie took to make, so I’ll use the release date as my benchmark. With the exceptions noted at the end, I haven’t checked people’s birthdays against day and month release dates. As a result, the ages of directors that I’ll be giving fall within a year of the releases. That works well enough to establish an approximate age range for a general tendency. And since it takes at least a year to get a project finished and released, we have to remember that most of these people started work on their first feature quite a bit earlier than is indicated by the age I give.

Start with directors who broke through in the 1990s and 2000s. Many were about 30 when their first features came out: Keenen Ivory Wyans (above; I’m Gonna Get You Sucka), Michael Bay (Bad Boys), David Fincher (Alien 3), and Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich). A tad older at their debuts were Alex Proyas at 31 (The Crow), Cameron Crowe at 32 (Say Anything), James Mangold at 32 (Heavy), Karyn Kusuma at 32 (Girlfight), McG at 32 (Charlie’s Angels), David Koepp at 33 (The Trigger Effect), Allison Anders at 33 (Border Radio), and Mark Neveldine at 33 (Crank).

Actually these are the older entrants. A great many current directors completed their first feature in their twenties. Quentin Tarantino, Reginald Hudlin, Roger Avary, and Joe Carnahan debuted at 29, Sofia Coppola and Brett Ratner at 28, Peter Jackson and F. Gary Gray at 26.

Go a little further past 33 and you’ll find a few big names like Alexander Payne (35), Nicole Holofcenter (36), Simon West (36), and Ang Lee (38). Almost no contemporary directors broke into the game past 40. The most striking case I found is Mimi Leder, who signed The Peacemaker when she was 45.

On the whole, the directors who start old have found fame and power playing other roles. When you’re David Mamet, you can tackle your first feature at 40. (He’s my age; don’t think this doesn’t make me depressed.) If you’re a producer like Bob Shaye or Jon Avnet, you can start directing in your fifties. Actors, especially stars, get a pass at any age. Mel Gibson made his first feature at 37, Steve Buscemi at 39, Barbra Streisand at 41, Anthony Hopkins at 59.

Putting aside such heavyweights, the lesson seems to be this. In today’s Hollywood, a novice director is likely to start making features between ages 26 and 34. It’s also very likely that he or she will have already done professional directing in commercials, music videos, or episodic TV, as many of my samples did.

But what about the Movie Brats?

Is today’s youth boom a new development? The Baby Boomers will yelp, “No! Everybody knows that we invented the director-prodigy.” Look:

*Dementia 13: Francis Ford Coppola, 24. If you don’t want to count that, You’re a Big Boy Now was released when Coppola was 27.

*Who’s That Knocking at My Door?: Martin Scorsese, 25.

*Dark Star: John Carpenter (above), 26.

*THX 1138: George Lucas, 27.

*Night of the Living Dead: George Romero, 28.

*The Sugarland Express: Steven Spielberg, 28. If you count the TV feature Duel, subtract 2 years.

*Targets: Peter Bogdanovich, 29.

*Dillinger: John Milius, 29.

*Blue Collar: Paul Schrader, 32.

*Good Times (with Sonny and Cher): William Friedkin, 32.

*Easy Rider: Dennis Hopper, 33.

True, the 70s also revved up veterans like Altman and Ashby, but it was the new generation, we’re always told, who made the difference. Hollywood was run by old men who had brought the studio system to the brink of ruin. The twentysomethings smashed the barricades and made a place for young filmmakers.

It might have seemed that way at the time, but the belief was probably due to a quirk of history. The 1960s and early 1970s were in one respect a unique period in the history of American cinema. During those years, the studios had the widest range of age and experience ever assembled. For the first time in history, it looked like a retirement home.

Look at it this way. In the 1960s, films were being made by directors who had started in the 1950s (e.g., Arthur Penn, Sidney Lumet), as you’d expect. But at the same time there were films by directors who had started in the 1940s: Fred Zinneman, Sam Fuller, Robert Aldrich, Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Vincente Minnelli, Robert Rossen, Robert Wise, Mark Robson, and many others. Furthermore, some of the biggest names of the 1960s were directors who had started in the 1930s, like George Cukor, Carol Reed, George Stevens, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Mankiewicz. More remarkably, the 1960s saw the release of films by masters who had begun in the 1920s, notably Hitchcock, Hawks, Capra, and Wyler.

And believe it or not, several directors who had begun in the 1910s were still active nearly fifty years later. John Ford is the most obvious case, but Chaplin, Alan Dwan, Henry King, Fritz Lang, George Marshall, and Raoul Walsh signed films in the 1960s. When Sidney Lumet celebrates a half-century of directing with the upcoming release of Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, he will be considered a rare bird in today’s cinema; but in a broader historical context he doesn’t stand alone.

Interestingly, the arrival of the Movie Brats and the blockbuster brought nearly all the veterans’ careers to a halt. No matter what decade an old-timer started, by the mid-1970s he was most likely dead, retired, or making flops. Perhaps the Movie Brats’ sense of Hollywood as a haunted house was created in part by the felt presence of six decades of history.

The studio years

But what about those codgers? At what age did they get started? A look at the evidence suggests that the rise of the twentysomething Movie Brats has plenty of precedents.

The Hollywood studios ran a sort of apprentice system. In the 1920s and 1930s, short comedies and dramas were the era’s equivalent of music videos and commercials—ephemeral material that allowed youngsters to learn their craft. For example, George Stevens started as a cameraman, and at age 26 graduated to directing short comedies. Three years later he made his first feature (The Cohens and Kellys in Trouble, 1933).

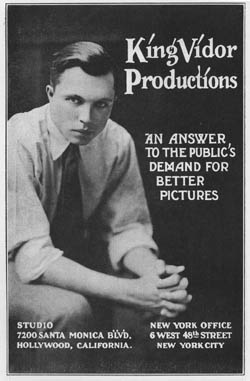

Stevens wasn’t atypical. In the 1920s and 1930s, major directors seem to have started as young as they do now. King Vidor began in features at 25, Rouben Mamoulian at 26. Mervyn LeRoy’s first feature was released when he was 27, the same age that Keaton, Capra, and Sam Taylor entered the field. Byron Haskin and W. S. Van Dyke made their debuts at 28. Hawks started at 30, as did Victor Fleming, Lewis Milestone, and Joseph H. Lewis. Clarence Brown signed his first solo feature at 31, the same age as Jules Dassin and George Cukor at their debuts.

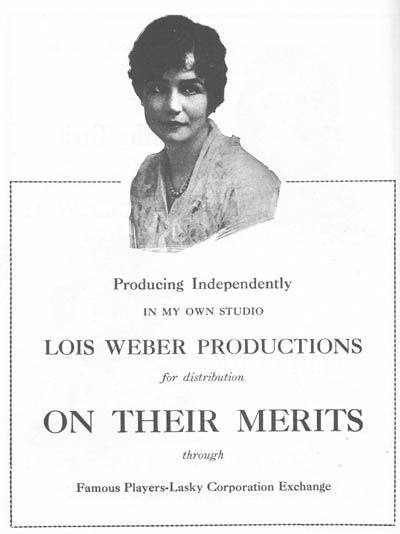

Even more remarkable is what went on during the 1910s. As Hollywood was becoming a film capital, it became a playground for twentysomethings. Lois Weber, Alan Dwan (who may have directed 400 movies), James Cruze, Reginald Barker, George Marshall, George Fitzmaurice, Raoul Walsh, and many others directed their first features before they were thirty. (At this point, a feature film could be around an hour. Kristin explains here.) Cecil B. DeMille was on the senior side, having directed The Squaw Man (1914) at age 33. Griffith was then even older of course, but having started in 1908, somewhat earlier than this generation, his authority waned as theirs rose. And he had started directing within my golden zone, at age 33.

Why so many youngsters? In the 1910s, the industry was growing rapidly and it needed a lot of labor. Few people went to college, so teenagers could take low-level jobs at the studios straight out of high school, or even without a secondary education. Moreover, Kristin reminds me that at this time life expectancy was much lower than today; in 1915 a white male on average would live only 53 years. Beginners hurried to get started, and bosses probably found comparatively few oldsters around.

At the other extreme, the World War II years seem to have been a tough time to break in. Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Don Siegel, Richard Brooks, Robert Aldrich, Robert Rossen, and other gifted directors had to wait until their mid- to late thirties before taking the director’s chair in the second half of the 1940s. The 1950s somewhat put the premium on youth again with fresh blood, especially from the East Coast. The most famous instances are Stanley Kubrick (Hollywood feature debut at 28), John Frankenheimer (debut at 30), and John Cassavetes (Hollywood debut at 32).

In short, Hollywood has always favored fresh-faced novices. It’s not surprising. Young people will work exceptionally hard for little pay. They have reserves of energy to cope with a milieu dominated by deadlines, delays, long hours, and rough justice. They are more or less idealistic, which allows them to be exploited but which also infuses the creative process with some imagination and daring. The executives need wisdom, but the talent needs, as they say, a vision.

Some last questions

Of course in every era a few older hands start directing features comparatively late. Lloyd Bacon, auteur of the masterpiece Footlight Parade, didn’t make a feature (Broken Hearts of Hollywood, 1926) until he was thirty-seven, after dozens of shorts. Daniel Petrie was forty when his 1960 feature The Bramble Bush was released, and Julie Dash was forty when Daughters of the Dust came out. But you have to look hard to find careers starting this late. Most of the evidence I’ve seen indicates that first features skew young.

First question, then: Is the tendency to seize talent young unique to Hollywood, or is it a characteristic of other popular film industries? My hunch is that it has been a worldwide phenomenon. Eisenstein, who was 27 when he made Potemkin, was treated the oldest of his cohort of Soviet directors; at the other end of that scale were Gregori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, who collaborated on their first film when they were 19! In Japan, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Kurosawa started directing in their twenties. Michael Curtiz was 30 when he made his first feature, which happened to be Hungary’s first as well. The very name of the French New Wave was borrowed from a sociologist’s catchphrase for postwar twentysomethings. Today, in Europe or Asia, most beginning directors are in their mid-to-late twenties or early thirties. I suspect that everywhere the film industry gobbles up youth, both in front of and behind the camera.

Second, a question for further research. Hollywood hires a lot of first-timers, but how many of them build long-lasting careers? It’s sometimes said that it’s easier to get a first feature than a second.

Third, who’s the youngest director to make a Hollywood feature? The most famous candidate for the Early Admissions program is Orson Welles, who was 25 when Citizen Kane premiered. But on this score at least his old rival William Wyler had him beat. Wyler was 24 when he released his first feature. The fact that his mother was a cousin of Carl Laemmle, boss of Universal, doubtless helped him start near the top.

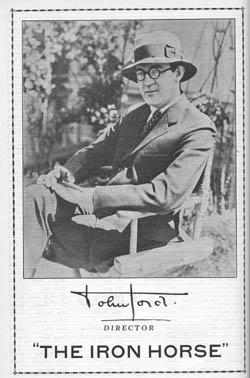

So is Wyler, at 24, the winner? No. John Ford, Ron Howard, and Harmony Korine were 23 when their first features opened. But wait: Leo McCarey was only 22 when his first feature (Society Secrets) was released in 1921. M. Knight Shyamalan’s first first feature, Praying with Anger, achieved a limited release in 1993, when he was 22.

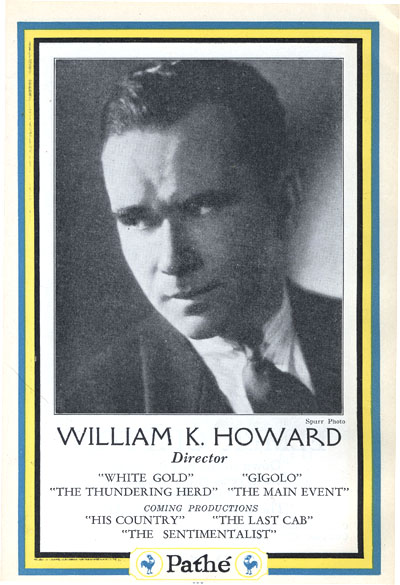

Yet I think that William K. Howard has the edge. Born on 16 June 1899, he signed two features in late 1921, when he was 22, putting him abreast of McCarey and Shyamalan. But Howard also co-directed a feature that was released on 22 May 1921—about three weeks before his twenty-second birthday. Brett and Sofia and PJ, you are so over the hill.

(Once we move out of the US, the clear winner would seem to be Hana Makhmalbaf. When she was ten, she served as AD for her sister Samira on The Apple, and she signed a documentary feature when she was fifteen. “I used to get excited over the words sound, camera, action. There was a strange power in these three words. That’s why I quit elementary school after second grade at age eight.”)

Finally, how does a little knowledge of film history help us steer hopefuls on the road to Hollywood? It gives us a sharper sense of timing and opportunity. My best revised answer would be this.

Start as young as you can, in any capacity. For directing music videos and commercials, the window opens around age 23. For features, the best you can hope for is to start in your late twenties. But the window closes too. If you haven’t directed a feature-length Hollywood picture by the time you’re 35, you probably never will.

Unless your last name is Bruckheimer, Bullock, Kidman, Cruise, or Bale.

PS 16 Sept 2007: Some corrections and updates: I’m not surprised that my more or less random sampling missed some things. So I’m happy to say that we have new contenders in the youth category.

Charles Coleman, Film Program Director at Facets in Chicago, pointed out that Matty Rich was only 19 when Straight Out of Brooklyn was released in 1991. So my candidate, William K. Howard, is second-best at best.

As for Hana Makhmalbaf, she’s been beaten too. Alert reader Ben Dooley wrote to tell me of Kishan Shrikanth, who was evidently ten years old at the release of his feature, Care of Footpath, a Kannada film featuring several Indian stars. Kishan, a movie actor from the age of four, has been dubbed the world’s youngest feature film director by the Guinness Book of World Records. You can read about him here, and this is an interview.

As for Hana Makhmalbaf, she’s been beaten too. Alert reader Ben Dooley wrote to tell me of Kishan Shrikanth, who was evidently ten years old at the release of his feature, Care of Footpath, a Kannada film featuring several Indian stars. Kishan, a movie actor from the age of four, has been dubbed the world’s youngest feature film director by the Guinness Book of World Records. You can read about him here, and this is an interview.

From Australia, critic Adrian Martin writes to point out that Alex Proyas made features before The Crow. “A clear case of Hollywood/ Americanist bias!! (Just kidding.) Proyas had an extensive career in Australia before the USA, and that includes his first, intriguing feature, Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds, in 1989. Which puts him around 27 at the time!”

Finally (but what is final in a discussion like this?) over at Mark Mayerson’s informative animation blog, there’s a discussion about animation directors, who tend to be quite a bit older when they sign their first full-length effort. Mark’s reflections and the comments point up some differences between career opportunities in live-action and animated features.

PPS 27 December 2007: Malcolm Mays, currently 17 years old, is shooting a feature under studio auspices. Read the inspiring story here.