Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Updates: Len Lye, Frodo Franchise, blockbusters, and news from/about Hong Kong

Kristin here—

More on Len Lye

After my recent post on Len Lye, I heard from both Roger Horrocks, Lye’s biographer, and Tyler Cann, Curator of the Len Lye Collecton of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. (Neither with corrections, I am happy to say!) They have filled me in on some activities that should make Lye’s film work more accessible.

First, a DVD of Lye’s films is being prepared. Unfortunately factors like the process of assembling the best surviving prints means that the finished product will not be available in the near future.

Second, the near future will bring a touring program of Lye’s films to North America. Called “Free Radical: The Films of Len Lye,” it has been organized by The New Zealand Film Archive, the Len Lye Foundation, and Anthology Film Archives. (The name was inspired by Lye’s scratched-on-film animated short, Free Radicals, 1958.) Here are the venues and dates:

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 18 NASCAD (Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) Halifax, Nova Scotia

Oct 23 Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

Oct. 28 Film Forum, Los Angeles

Oct 30th CALARTS, Los Angeles

Nov 2nd University of Notre Dame, Indiana

Nov. 7th George Eastman House, Rochester

Nov. 26th Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge

Dec 8th Chicago Filmmakers, Chicago

Dec. 15th International House, Philadelphia

Roger tells me that he intends to write a book on Lye’s theory and practice of what he called “the art of motion.” This reminds me that I forgot to mention that there is a collection of Lye’s writings, Figures of Motion: Len Lye Selected Writings, co-published in 1984 by Auckland University Press and Oxford University Press. It was co-edited by Roger and Wystan Curnow and is, alas, long out of print. Another thing to look for in your local library.

The Frodo Franchise

I am happy to report that The Frodo Franchise is now in the process of being rolled out. The University of California Press has been shipping copies for weeks, and it should soon appear on bookstore shelves—and may have already in some places. The copy we pre-ordered from Amazon back in April arrived on July 30.

I have bowed to the inevitable and am in the process of constructing a separate website, “Frodo Franchise,” to deal with matters relating to the book and the films. (That is, Meg, our web czarina, is constructing it.) I don’t want information about the book, comments on the Hobbit film situation, and similar items to overbalance our blog, which they threaten to do. I’ll post a notice when the site is up and running.

In the meantime, Pieter Collins of the Tolkien Library, an excellent reference and news site dedicated to the novels, has interviewed me about my book. You can read the result here. Henry Jenkins has done the same, through his site, Confessions of an Aca-Fan, is more oriented toward popular media and fandom. The interview is in three parts here, here, and here.

Hollywood Blockbusters Doing Pretty Well

On February 28 I posted an entry, “World rejects Hollywood blockbusters?” There I argued against claims in an article by Nathan Gardels, editor of NPQ and Global Viewpoint, and Michael Medavoy, CEO of Phoenix Pictures and producer of, among many others, Miss Potter. They claimed that there were many signs that Hollywood’s big-budget films are being rejected at the box office: “Audience trends for American blockbusters are beginning to show a decline as well, both at home and abroad.”

Since then, of course, Hollywood blockbusters have been cleaning up at home and abroad. We’re all familiar by now with the series of huge international openings, with many blockbusters being released day and date in most major markets. As one example, take Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, which so far has grossed $774,070,000 worldwide. The US and Canada claimed only about one-third ($264 million) of that total (Box Office Mojo, August 4). Overseas, Phoenix has scored $510 million, for 65.9% of its global haul. The Three Threes, Shrek, Pirates, and Spider-man, all cleaned up internationally, as did Transformers. (The fourth Three film, The Bourne Ultimatum, looks set to do the same.) The Simpsons Movie has recently begun its climb to box-office glory.

Leonard Klady, an excellent writer on the international film industry, summed up the situation for 2007 in the 22 June print edition of Screen International: “Worldwide predictions that 2007 would break recent box-office records look to be well founded. The international box office generated $4.5bn in the first four months of 2007. Combined with revenues from the domestic North American marketplace, the global gross for the period was $7.2bn. International theatrical [i.e., markets outside the U.S. and Canada] accounted for 61.6% of the worldwide box office on gross figures that exceeded domestic ticket sales by 60.6%. Based on current viewing trends, global box office could finish the year at a record-breaking $24.6bn.”

Klady points out that much of the rise comes from the factor I discussed in my earlier entry: the expansion of the international market. According to him, “The international market has become increasingly significant in the past decade.” A decade ago, foreign income averaged 45% of Hollywood films’ takings. By 2006 it was around two-thirds.

These facts also bear on Neil Gabler’s February article, “The movie magic is gone,” where he lamented the purported decline in theatrical films’ importance. That there was such a decline, he claimed, was evidenced by the fact that box-office revenues are down, both domestically and abroad. I refuted Gabler’s claims at some length in this March 11 post, and the successful summer that Hollywood is now enjoying adds further evidence to show that his argument was based on false assumptions.

DB here–

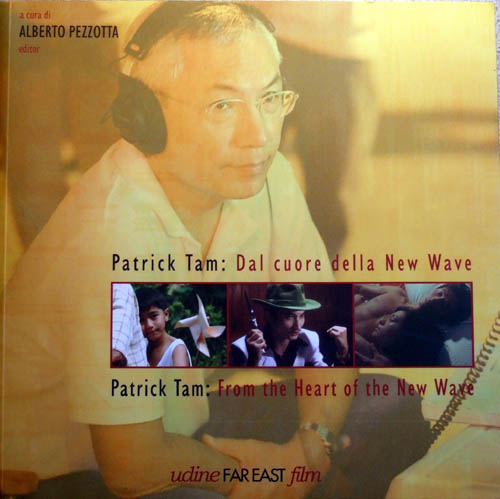

The Udine Far East Film Festival had a tremendous program this year, and just the YouTube promo made you want to book a ticket. But I couldn’t go! Still, the organizers kindly sent me their excellent catalogue Nickelodeon and the real topper, the festival’s thick volume dedicated to Patrick Tam Kar-ming. Editor Alberto Pezzotta, indefatigable researcher into Hong Kong film, organized a vast retrospective of Tam’s key New Wave films, such as Nomad and The Sword, as well as his less-known television work. The book includes critical essays, a detailed filmography, and a long, informative interview. Tam brought a cosmopolitan sensibility to Hong Kong film, thanks to his sensitivity to European directors like Godard and Antonioni. His latest film, the widely acclaimed After This, Our Exile, signals a new phase in his career.

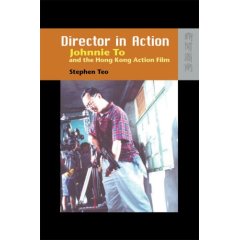

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

Fantasy franchises or franchise fantasies?

Kristin here–

While David is watching films in Brussels, I’m back in Madison, overseeing some house renovations, moving into the publicity phase of The Frodo Franchise in anticipation of its release, and generally enjoying a chance to catch up on my reading.

I’ve also finally tackled one of those “someday we really must …” projects. Not surprisingly, a considerable portion of our home is given over to storing books, journals, file folders, DVDs, videotapes, laserdiscs, negatives, and slides. For all too long a heap of old magazines has been sitting on the floor in the aisle between two of our bookshelves, on the assumption that someday we really must triage these and file the clippings in subject folders where we might actually have a chance of finding them.

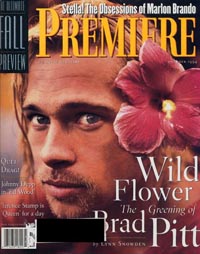

Most of these magazines are old issues of Premiere, mainly from the 1990s. Premiere ceased publication as of April, and I can’t say that I miss it greatly. It had slid distinctly by then, but back in the nineties it was actually pretty good. (J. Hoberman was writing regularly for it!) Every issue I’ve examined so far has at least one item worth saving, and sometimes two or three.

These issues aren’t in chronological order, so the first stack I scooped up to look through was a random batch, with the October 1994 issue on top. It featured a  big close-up of Brad Pitt on its cover. He was just on the brink of becoming a star, being best known to that point for his supporting roles in Thelma and Louise and A River Runs Through It. He had just finished Interview with the Vampire.

big close-up of Brad Pitt on its cover. He was just on the brink of becoming a star, being best known to that point for his supporting roles in Thelma and Louise and A River Runs Through It. He had just finished Interview with the Vampire.

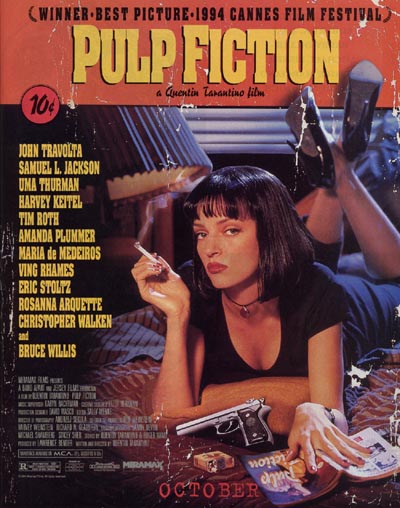

What interested me more was an ad that greeted me as I flipped the first few pages: the famous fake-worn-dust-jacket ad for Pulp Fiction. Odd that I had happened to begin with an issue from the season when one of the most influential films of the past two decades was being touted in preparation for its October release.

Indeed, the April issue happened to contain Premiere’s “Ultimate Fall Preview.” Naturally I got sucked into checking out what other films had been released that season. Given all the complaints these days about franchise films dominating Hollywood and pushing out the worthwhile films, I wondered just how good the good old days were.

To get a sense of what was going on in 1994, let’s start with the 10 top-grossing films of the year. Based on Box Office Mojo’s list of domestic grosses (in unadjusted dollars), they are: Forrest Gump, The Lion King, True Lies, The Santa Clause, The Flintstones, Dumb and Dumber, Clear and Present Danger, Speed, The Mask, and Pulp Fiction.

From our current perspective, the lack of franchise films on this list is striking. Only Clear and Present Danger, the second film starring Harrison Ford as Jack Ryan, belongs to part of an exiting series. The only film in a long-established franchise that came near the top was Star Trek: Generations at #15. Other sequels appear further down the top 50: The Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult (#23), City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly’s Gold (#32), Beverly Hills Cop III (#34), and Major League II (#45). No wonder sequels got a bad reputation!

On the other hand, several films in the top 10 spawned sequels: The Santa Clause, Dumb and Dumber, Speed, and The Mask. (Dumb and Dumber and The Mask both had their sequels considerably delayed by New Line Cinema’s inability to meet Jim Carrey’s skyrocketing salary demands and his resultant departure from the studio.)

In 1994, Hollywood was still in the early days of the franchise trend. After Batman in 1989, its sequel, Batman Returns, had come out in 1992, but that wasn’t enough to establish a pattern. Jurassic Park had appeared the year before but hadn’t yet seen a sequel. Aliens (1986) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) had both appeared seven years after the first films, suggesting that there was not exactly an automatic impulse to generate franchises. In fact, in 1994 we might expect to find Hollywood relatively untainted by franchise fever. Hence it should also very different from Hollywood today—if it’s true that franchises drive out other films. If all the anti-franchise critics are right, 1994 should also be a distinctly better year for auteurist fare, art-house movies, and stand-alone popular films.

What do we find in Premiere’s fall preview? In some ways it looks like a strong season. Apart from Pulp Fiction and Interview with the Vampire, there are Tim Burton’s Ed Wood, Robert Altman’s Prêt-à-Porter, Woody Allen’s Bullets over Broadway, Luc Besson’s Léon (aka The Professional), Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption, and Alan Rudolph’s Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle. Notable as well are Quiz Show and Nell. Buried in the “Also in Season” box at the end are Frederick Marx’s documentary Hoop Dreams, Clerks (with Kevin Smith not even mentioned), and Krysztof Kieslowski’s Red.

Alongside these films, though, there are the usual forgettable items: Junior (the Arnold Schwarzenegger-gets-pregnant comedy), Little Women, Disclosure, The Pagemaster, Radioland Murders and a bunch of other films that don’t get watched much anymore.

Putting aside the huge blockbusters of 2007, the fall season of 1994 doesn’t look all that different from the kind of fare Hollywood puts out now. Many of the same auteurs are with us. Burton is making Sweeney Todd (again with Johnny Depp). Allen continues to direct at his usual fast clip, albeit now in Europe. Besson promises more “Arthur” animated features. Darabont’s Stephen King adaptation, The Mist, is due out in November. Jordon’s thriller, The Brave One, starring Jodie Foster, is announced for September. Smith’s Clerks II came out last year. Tarantino tried to find inspiration by moving from dime novels to grindhouse movies, this time without success. The influence of his 1994 classic, however, is still very much with us. Even the unexpected success of Hoop Dreams is echoed by the recent vogue for documentaries. We have lost some of our major directors since 1994, of course, including Altman and Kieslowski, and Rudolph seems finally to have ceased being able to fund his eccentric independent films.

Is the fall season of 1994 typical? Premiere also used to run a chart of the year’s major releases called “Critics Choice,” which used a one-to-four-stars system to show how favorably each film was received by fifteen popular reviewers. Looking at the rest of 1994’s more memorable films, we find more familiar current directors , including Spike Lee (Crooklyn), the Coen Brothers (The Hudsucker Proxy), Ron Howard (The Paper), Oliver Stone (Natural Born Killers), John Waters (Serial Mom), Ben Stiller (Reality Bites), Zhang Yimou (To Live), Bille August (The House of the Spirits), Ang Lee (Eat Drink Man Woman), Kenneth Branagh (Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), Ken Loach (Ladybird Ladybird), James Cameron (True Lies), Robert Zemekis (Forrest Gump), Peter Jackson (Heavenly Creatures) and on, and on. Steven Spielberg would be there, too, if Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park hadn’t both come out in 1993. There is also the smattering of adorably eccentric (Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert) or beautifully acted (The Madness of King George) English-language imports of the sort that find an audience each year—not to mention the unclassifiable Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould. And 1994 was no richer in subtitled fare than recent years have been: apart from Red and To Live, the only other notable foreign-language import is Queen Margot.

I don’t want to push the similarities between this randomly chosen season and the current Hollywood situation too much. There certainly are some differences. The rise of blockbuster franchises has changed the pattern of releases, with the big series films occupying the summer and Christmas seasons. It’s interesting, for example, to note that the year’s top grosser, Forrest Gump, was released in July (a week before True Lies), while today it would probably be given a fall slot. That’s just a matter of timing, though. Even there we have distributors using counter-programming for smaller films, some of which inevitably become surprise successes, like The 40 Year Old Virgin.

So just what is it that got pushed out by franchises?

(For more on sequels and franchises, see the May discussion by the Badger squad and Henry Jenkins on the third Pirates of the Caribbean film. A lot of comments have been added to the latter since I first linked it. I see that Henry’s post was also cited by Lee Marshall in an article in the June 22, 2007 issue of Screen International, “The People’s Choice.” Marshall makes the point that reviewers who lambaste big franchise films often do so in a condescending way that implicitly criticizes the public for liking them.)

Once more on New Line, Peter Jackson, and The Hobbit

Gandalf introduces Bilbo to Beorn. Illustration by Michael Hague

Kristin here–

After several months of raised and dashed hopes, the question of who will direct the film of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit remains open. I first weighed in on the question back on October 2 of last year, when this blog was in its infancy. MGM had just announced that they would be making The Hobbit and hoped that Peter Jackson would direct. At that point I was trying to sort out Peter Jackson’s large number of film projects and to explain how his schedule might include time to direct The Hobbit.

Subsequently there was a clarification. MGM, which owns the distribution rights to any film version of the novel, would co-produce with New Line, which produced The Lord of the Rings and owns the filmmaking rights for The Hobbit.

Then, early this year, New Line founder and co-president Bob Shaye declared in an interview that Jackson would never direct The Hobbit while he is in charge of the company. The obstacle was a lawsuit that Jackson had filed against New Line; he wanted an accounting of earnings on the DVDs of The Fellowship of the Ring and various licensed products. See my January 13 attempt to explain all that.

As before, no doubt negotiations are going on behind the scenes. To reiterate my disclaimer from the earlier entries, I have no inside information, given that my contact with Jackson and the other filmmakers was back in 2003 and 2004, during the research for The Frodo Franchise. As someone who has followed the situation very closely since undertaking my book back in 2002, however, I can make what I hope are some enlightening comments on the scraps of news that have appeared since January.

A faint hint that Shaye might possibly be backing away from his absolute rejection of Jackson as director for The Hobbit came in a brief interview in the April issue of Wired (also online). As far as I could tell, this went largely unremarked at the time. The first two questions related to The Last Mimzy, the children’s fantasy directed by Shaye, which was then being released to what proved to be disappointing box-office results. Inevitably, though, the interviewer switched to the Hobbit situation:

You recently said Peter Jackson would never touch The Hobbit while you were at New Line.

You know, we’re being sued right now, so I can’t comment on ongoing litigation. But I said some things publicly, and I’m sorry that I’ve lost a colleague and a friend.

Is The Hobbit still a viable project?

I can only say we’re going to do the best we can with it. I respect the fans a lot.

Shaye’s statements might be seen by some as implying that he regretted his rejection of Jackson as a director. Given that the vast majority of fans want Jackson to direct, the last sentence seems to offer hope that Shaye might relent and bow to their wishes.

A greater stir was caused by Entertainment Weekly’s April 16 announcement that Sam Raimi had expressed interest in directing The Hobbit—a possibility that had been circulating widely as a rumor since shortly after Shaye’s January pronouncement. As I suggested in my previous entry, however, most directors would shrink from upsetting Jackson and his fans by simply taking the job. Raimi made it clear what circumstances would be necessary: “First and foremost, those are Peter Jackson and Bob Shaye’s films. If Peter didn’t want to do it and Bob wanted me to do it—and they were both okay with me picking up the reins—that would be great. I love the book.” (Raimi presumably refers to films in the plural because MGM had suggested in September that it was considering a two-part adaptation.)

Raimi risked riling not only Rings fans but Spider-Man afficionados, who were upset at the idea that he might bow out of a presumed fourth entry in his own franchise. In the nearly two months since Raimi’s statement, there has been no public indication that he is being seriously courted to accept the job directing The Hobbit.

Jackson, however, has been busy. The projects on his plate have changed considerably since early October. Only a few weeks after my summary, Universal and Twentieth Century Fox, which had been on board to finance the video-game-to-film adaptation of Halo for co-production by Jackson and Microsoft, bowed out. The project is now on hold, with the assumption that the release of the Halo 3 game, announced for September 27, will regenerate studios’ interest.

The remake of The Dam Busters is moving forward, but it is being directed by Christian Rivers rather than Jackson, who serves as producer. The acquisition of Naomi Novik’s “Temeraire” series by Jackson and partner Fran Walsh, announced September 12, apparently has not resulted in a specific project. The pair presumably have the option of making it into a film at some future date or letting their option lapse.

The project that has made great progress is Jackson and Walsh’s adaptation of Alice Sebold’s bestseller The Lovely Bones. Their script was up for bids this spring, and on May 4, Variety announced its sale to Dreamworks. Reportedly the film will be delivered by the fourth quarter of 2008. It might be possible to commence pre-production work on a Hobbit film while The Lovely Bones is in progress.

Less than two weeks later, Variety revealed that Steven Spielberg is teaming with Jackson to produce three feature films based on the classic Belgian comic books starring Tintin. Each plans to direct one of the features, with a third director undertaking the other.

In October I suggested that most of Jackson’s projects were flexible in their timing, and that left the possibility that he could shift them around to fit in The Hobbit. Given that no timing has been announced for the Tintin films, Jackson’s only apparent project with a deadline is The Lovely Bones.

Finally, at the Cannes Film Festival, Shaye and co-president of New Line Michael Lynne spoke to Variety’s editor-in-chief, Peter Bart, about the Hobbit project. Their remarks might give Rings fans cause for hope.

Shaye maintained his stance, declaring that New Line had paid Jackson and Walsh $250 million in profit participation. “The clash happened because ‘one of us has gotten poor counsel,’ Shaye said, without elaborating.”

The story continues: “Co-chief Michael Lynne struck a more upbeat note. ‘We do want to settle our dispute and I think we will.’” Neither would comment on the rumors that Raimi was being wooed for the Hobbit adaptation. When asked about Raimi, Lynne replied, “There’s never been any announcement.” Shaye added, “Like a lot of people, he might.”

I think there are two major factors underlying this feud between Jackson and Shaye that haven’t been pointed out and need to be. First, lawsuits of the type Jackson brought are pretty common in Hollywood. Second, Shaye is perhaps forgetting the amount of personal investment and financial risk Jackson took to get Rings made—investments that cost New Line nothing but which brought in a hugely successful film on a surprisingly low budget. (I explain how in the first chapter of The Frodo Franchise.)

Jackson’s isn’t even the first suit against New Line by someone central to the film’s making. Independent producer Saul Zaentz sold the adaptation rights to Miramax back in 1997, and that company in turn sold them to New Line in 1998. As part of these deals, Zaentz was to receive 5% of gross international receipts. He sued, claiming that the $168 million paid to him was calculated on net receipts, leaving a balance of $20 million owed him. The suit was to come to court on July 19, 2005, but New Line settled for an undisclosed amount shortly before that. The same thing could happen in Jackson’s case, and the settlement could come at any time.

Zaentz isn’t the only other person claiming to have been shortchanged by New Line. On May 30 of this year, a group of fifteen Kiwi actors filed a suit claiming that they had not been paid the 5% of net merchandising revenues for products bearing their likenesses. (The group includes Sarah McLeod, who played Rosie Cotton, Craig Parker, who played Haldir, and Bruce Hopkins, who played Gamling.) The suit isn’t likely to reach court soon, if ever, but Jackson isn’t alone in his doubts about New Line’s accounting practices.

Moreover, Jackson and Walsh spent an enormous amount of their own money upgrading the filmmaking firms in Wellington to make them sophisticated enough to handle all phases of Rings’s production. Weta’s two halves, Digital and Workshop, of which the couple owns a third, were vastly enlarged. Jackson and Walsh bought the country’s only post-production facility, The Film Unit, when it was for sale and under threat to be moved out of New Zealand. They went into debt to do that, and it, too, was enlarged and moved into a huge facility full of highly sophisticated equipment. Much of this expansion was paid for with the money Jackson received for making Rings.

The result was a trio of films that grossed nearly $3 billion internationally, as well as untold additional revenues for the DVDs, video games, and other ancillaries. New Line went from a small subsidiary of Time Warner known mainly for its Nightmare on Elm Street series to a well-respected company making prestige films like Terence Malick’s The New World and the upcoming The Golden Compass, an adaptation of the first novel of Phillip Pullman’s award-winning trilogy. Oh, and there’s the matter of the seventeen Oscars Rings won. Previously New Line, founded in 1967, had won two.

In the wake of Rings, Jackson was faced with having to keep Weta, The Film Unit (now renamed Park Road Post), the Stone Street Studios, and his WingNut production firm going. Beyond the physical facilities, which no doubt involve enormous overhead costs, there are the many hundreds of employees to be paid. New Line did not invest in these facilities. Jackson and Walsh, along with their partners Richard Taylor and Jamie Selkirk, did.

When I first visited Wellington, there was a question as to whether there would be enough business to keep the facilities going and the employees in work. King Kong helped in the short run, but would other big films follow? Since then, Weta Workshop has diversified and is thriving. Weta Digital gets regular work doing the CGI for large numbers of shots in such films as X-Men 3: The Last Stand and Eragon. James Cameron’s decision to make Avatar in Jackson’s facilities seems the final seal of approval. Weta Digital is now widely considered one of the top digital effects houses in the world, alongside such firms as ILM, Sony’s Imageworks, and Rhythm & Hues.

Now the Wellington facilities all seem to be doing well. Nevertheless, in the era before Rings’s release and huge success, Jackson took as big a risk as Shaye did. Maybe bigger. Shaye might ponder that as he decides what to do about the Hobbit project. He owes the Kiwi filmmaker gratitude for more than simply directing a runaway hit.

Beyond that, unless New Line has short-changed Jackson very badly through its accounting procedures (and all that would presumably come out eventually when the suit finishes up), the added value provided by the director’s name on a Hobbit film would surely be at least as great as the money owed. Unless there is some major unknown factor influencing Shaye’s decision, he would do well to tamp his resentment, make peace, and initiate a project that is as close to a guaranteed mega-hit as anything can be these days. He could settle out of court, as he did with Zaentz, and just get on with it.

[Added July 21: For my update on the Hobbit film, go here.]

[Added August 6: For my earlier comments on the Hobbit film, go here and here.]

Cannes: Behind the art, hype, and politics

Kristin here–

The Festival de Cannes has been around since 1946, so a sixtieth birthday party this year might seem a bit belated. The festival got off to a rocky start, however, and lack of funds forced its cancellation in 1948 and 1950.

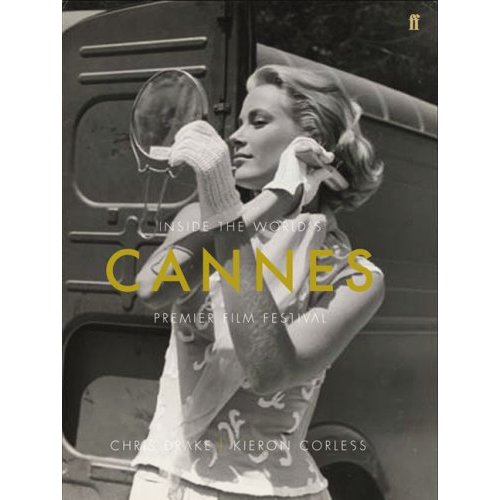

There have been many forms of celebration, but one that is likely to endure is Kieron Corless and Chris Darke’s new history, Cannes: Inside the World’s Premier Film Festival. We picked up a copy in Auckland. The book, published by Faber and Faber this year, is not currently available in the U.S. but is on offer from Amazon’s U.K. branch.

As the authors themselves note, “This is not one of those anecdotal and slightly self-indulgent Cannes memoirs, of which there are several available in English and French” (p. 3). Instead, they avoid the gossipy approach, trying “to redress the balance and probe beneath the surface by telling another story—a counter-history of Cannes, if you will” (p. 2). This is not to say that Cannes is a dry, pedantic look at the event. I found it an absorbing read during the long plane trip from Auckland to Los Angeles. Who wouldn’t enjoy a book whose first chapter begins, “It is tempting to imagine the first Cannes film festival as a Jacques Tati film”? And I wouldn’t call it a counter-history. It’s a solid historical study, well-researched and just the sort of study that any major festival warrants.

The approach is not chronological, though the authors segment the festival’s history into three phases. The first, stretching from 1946 to early 1968, saw Cannes as a platform for international politics, beginning with the Cold War and stretching into the “start of sixties libertarianism.” This period saw the rise of the great auteurs, such as Bergman, Fellini, and Buñuel, whose international reputations owed much to their exposure at the festival.

The second phase begins with the 1968 festival, where the political upheaval in France was enough to close the event down in midstream. In the years that followed, the festival’s organizers strove to become more inclusive, opening up to Third World films and inaugurating the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs to provide a venue for younger, more innovative filmmakers.

Corless and Darke see this phase as ending in 1983, when the opening of the new Palais des Festivals. That event ushered in an era of greater commercialism, more courting of the media, and the introduction of a film market alongside the festival. This third era continues today with the Hollywood studios’ increasing use of Cannes as an opportunity to launch blockbusters shortly before their summer releases.

Although the overall trajectory of the book follows these three phases, the chapters are organized primarily around thematic topics. For example, “Sacred Monsters” examines the increasingly provocative nature of some of the films shown at Cannes in the late 1950s and especially the 1960s. Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Rivette’s La Religieuse created scandals, and the authors use these to show how Catholic censorship affected the festival and how the titillation of more daring subject matter became a means of promoting European films in the U.S.

There is no shortage of anecdotes and discussion of the splashy, glamorous aspects of Cannes. Brigitte Bardot’s 1953 appearance, clad in a bikini and frolicking on the beach, is assessed partly in terms of its impact on her (and Roger Vadim’s) career. But the authors also show how in general starlets manipulated their interactions with more established stars (Kirk Douglas in Bardot’s case) to boost their own publicity value.

One major strand running through the book is the political pressures that frequently underlie the programming at Cannes. A festival launched in the immediate post-World War II years inevitably became a platform where the various countries jockeying for power could display themselves internationally by means of their films. The inclusion of Soviet Russian and later Eastern European movies became a delicate balancing act. The long love-hate relationship between France and the U.S. is traced. Determined to preserve its own culture in the face of competition from the dominant Hollywood product, the French also loved American films and desired the glamour they brought to the festival.

The authors also stress how Cannes’s organizers had to be forced to recognize filmmaking outside the U.S. and Europe by the traumatic shutdown of the 1968 festival. In 1969, Glauber Rocha won the Best Director prize for Antonio das Mortes, Fernando Solanas showed Hour of the Furnaces in the Critics Week program, and Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev—not the official Soviet entry—won the International Critics prize. In 1972, the system of allowing countries to choose their own films for competition was abolished in favor of selection by festival programmers.

A parallel strand considers how conservative Cannes has been through much of its history, both artistically and politically. In early decades, competition programming was done by allotting countries, primarily the U.S. and European nations, a certain number of slots. The countries then chose which titles they would send to fill those slots. Hollywood may have gained a surprisingly prominent place among Cannes’s screenings in recent years, but its films were a major part of the program in the early era as well. Multiple awards were given out in 1946, and honorees included Disney’s The Music Box and Wilder’s Lost Weekend. Wyler’s Friendly Persuasion, of all things, won the Palme d’Or in 1957.

Another sign of conservatism was the fact that major auteurs like Fellini and Bergman did not figure significantly at Cannes until they had already established their reputations. Only in the 1970s, with the post-war generation of filmmakers dying or retiring did the emphasis shift in part to discovering and launching young, unknown directors. Even then, though the book does not mention it, Cannes programmers largely overlooked the emerging 1990s East Asian cinema with China’s Fifth Generation, the New Taiwanese Cinema, and such current Cannes darlings as Wong Kar Wai.

Corless and Darke cannot cover every major event in a complicated history, but they are adept at choosing their case studies to provide a broad overview of the most important trends. Their concluding chapter deals with the immense growth in the number of film festivals and the consequent development of an alternative distribution market apart from theatres. They zero in on Abbas Kiarostami, arguably one of the greatest filmmakers working today but also the perfect exemplar of the “festival film-maker” (pp. 216-227).

The authors have an immense respect for the artistic value of Kiarostami’s work, but they also are clear-eyed in tracing the director’s dependence on Cannes and other festivals. Festivals have allowed him to keep directing in a country where his films have had little local acceptance, either from the government or from audiences. This section also offers an excellent summary of how the vibrant new Iranian filmmaking was brought to the world’s attention through Cannes and how other filmmakers, like Samira Makhmalbaf, have followed in Kiarostami’s wake.

This final chapter goes on to a case study that deals with how dependent on recent American independent cinema Cannes has become. Naturally the authors single out the Weinstein brothers and Miramax, which had their first big hit when sex, lies, and videotape won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1989. As the authors say, “‘Miramax’ also denotes a particular savvy commercial exploitation of independent or art cinema, whose cultural legitimacy and stamp of quality is conferred to a large extent by marketing exploitation of awards scooped at Cannes, which became hugely important to the Weinsteins” (p. 228).

The authors are film journalists and critics of a particularly serious bent. Corless is the deputy editor of Sight & Sound and writes for a variety of English magazines. Darke writes for such outlets as Film Comment, Sight & Sound, and Cahiers du cinéma. Given the drift toward pop entertainment coverage evident in those journals in recent years, the pair are to be congratulated on presenting substantive historical material in such a clear and readable fashion.

Apart from researching the written and filmed record on Cannes, the authors conducted interviews with a wide variety of Cannes organizers, attendees, and commentators. These range from Kiarostami to Tony Rayns to Gilles Jacob (general administrator from 1978 and president from 2000) to Rita Tushingham. (Mike Leigh’s comments are particularly trenchant and revealing, as when he describes Arnold Schwartzenegger’s stealing the spotlight by sweeping up the red carpet at the Cannes screening of Naked—and then disappearing through a side door before the film began.)

The only complaints I have about the book are some lapses in proofreading and a paucity of illustrations. Given the complaints about physical appearance of the 1983 Palais des Festival (nicknamed “the bunker”), it would be helpful to have a photo of it. That could easily have replaced the cluster of director portraits that ends the meager picture gallery.

Film festivals have become crucially important to both the art and business of the cinema, so Corless and Darke’s insights into how Cannes operates are most welcome.