Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Good Actors spell Good Acting, 2: Oscar bait

Kristin here–

David and I seem to be swimming against the stream of end-of-year blog entries. No ten-best lists, no predictions about Oscar nominations.

Instead, I’ll develop on the theme I introduced in my entry concerning the over-emphasis on star turns in reviews of films that contain an obviously outstanding performance. It’s interesting that quotes from such reviews are now routinely used in the “For Your Consideration” ads in show-business trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter when a studio is pushing a performance for award nominations.

There are a lot of good performances in any given year. We’ve all seen reviews that call a performance “Oscar-worthy” without the actor ending up getting nominated or even mentioned by pundits at year’s end predicting those nominations. Some types of performances just seem more like Oscar bait than others. What makes them that way?

Some of the reasons are apparent to almost anyone who pays any attention during the awards season. Notoriously, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences members prefer to honor dramatic roles rather than comic or musical ones. In 1985, a good deal of outrage was expressed—and rightly so–over the fact that Steve Martin was not nominated for his hilarious turn in All of Me. Conversely, the nomination of Johnny Depp for a comic role in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl created a stir, though few probably thought that he would actually win. (Remember, just being nominated is an honor, as nominees—and who would know better?—often point out.)

So, actors tend to be nominated for serious roles. Not just any kind of serious roles, though. History teaches us that playing a real person gives one’s chances for a “nod” (as nominations are for some reason now called). From Paul Muni in The Story of Louis Pasteur to George C. Scott in Patton to Ben Kingsley in Gandhi to Phillip Seymour Hoffman in Capote, it’s a familiar pattern. In the television age, when famous people’s appearances and behaviors are often familiar to the public, performances can become in part a matter of impersonation, and a skill at mimicry becomes a strong signal of “good acting.” Undoubtedly a performance like Helen Mirren’s as Elizabeth II in The Queen adds subtleties that go beyond the imitation of appearance and speech patterns and other obvious characteristics, but it’s the impersonation that gets talked about more.

Even when we’re not familiar with the person a character represents, for some reason it helps to have “based on a true story” attached to a title. Publicity often stresses that the actor met and spent time with the real person in order to craft an authentic performance.

Obviously making oneself less attractive to play a role gets Brownie points in a big way: Robert DeNiro gaining 60 pounds to play boxer Jake La Motta in Raging Bull, Charlize Theron sacrificing glamor in Monster, Nicole Kidman sporting an unflattering fake nose as Virginia Woolf in The Hours.

Characters with disabilities can definitely put an actor into the Oscar-bait realm: Cliff Robertson in Charly, John Mills in Ryan’s Daughter, Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot, or Jack Nicholson in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Presumably the implication of playing a real person or gaining weight for a role or simulating a disability all imply work, harder work than “just” playing a healthy, good-looking fictional person.

There are other indicators for nomination likelihood.

It helps to be old. Think Helen Hayes in Airport or Art Carney in Harry and Tonto. Their best performances? This year Peter O’Toole may finally get a non-honorary acting statuette.

It helps to be English and to have done Shakespeare.

For that matter, it helps to speak English. We’ll see if Penélope Cruz ends up being one of the very few to succeed without doing so. She did get nominated for a Golden Globe for Volver, but foreign-language films are definitely an afterthought when it comes to Academy Awards.

It helps to be Meryl Streep, whose performances don’t even have to fit any of these tendencies.

Oddly enough, most of these generalizations don’t seem to apply as much to the supporting-actor categories. Presumably “supporting” implies a less bravura turn that doesn’t compete with the stars.

Of course there are all sorts of reasons why actors get Oscars. A lot of people were surprised in 1997 when Juliette Binoche (The English Patient) beat out Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) as Best Supporting Actress. It helps to recall that three years earlier, through a technicality, Binoche had been judged ineligible to be nominated for Best Actress in Three Colors: Blue. The injustice of that clearly rankled Academy members (the majority of whom are actors), and the first time they had a chance to make it up to Binoche, they did. Both Jimmy Stewart and Denzel Washington supposedly won their Best Actor awards because voters felt they had deserved them for previous roles.

On Thursday the Golden Globes nominations were announced. Reporting on the Globes tends to center around their predictive powers for the later Academy Awards. (See “And … They’re Off!” in the new Entertainment Weekly.) The Globes are just as interesting, though, for the fact that they divide the main film-acting awards into two categories: “Drama” and “Musical or Comedy.” (Two parallel best-picture awards are given in these categories as well, but for some reason the supporting-actor awards aren’t divided by genre.) So Sacha Baron Cohen and Johnny Depp can get nominated for comedies and not have to compete against Will Smith and Forest Whitaker in dramas.

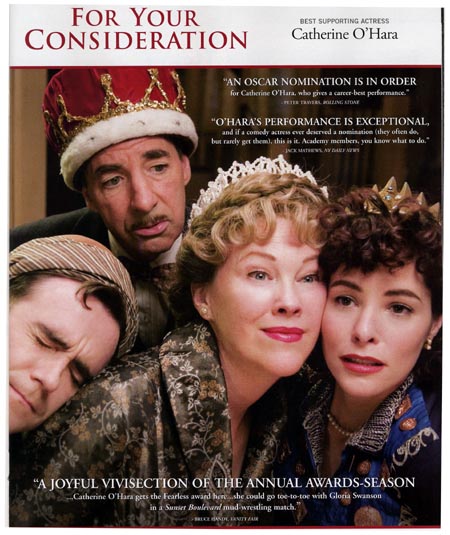

If you like endless speculation on nominees-to-be, check out the December 2006 Hollywood Reporter issue “The Actor.” In it Stephen Galloway talks about actors playing real people: “Whether a story surrounding a character is biographical or fictionalized, actors are determined to find the truth behind their real-life role models” (“As a Matter of Fact”). Part of the reason that the trade press devotes so much space to awards speculation is because these special issues sell lots of “For Your Consideration” ads. This year my favorite one touts Catherine O’Hara as best supporting actress. They don’t even have to tell us the title.

Borat Make Benefit Glorious Multinational of Murdoch

Kristin here–

For some reason, the November 10 issue of Entertainment Weekly ran a story right up front in their “Newsnotes” section as to whether Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan would be a success based on its internet hype. By the time the magazine showed up in our mailbox early the week after the November 3 release, the film had spectacularly won the weekend. Won it despite being in only 837 theaters. Won it with an average $31,607 per screen average for a total weekend haul of $26,455,463. By the way, shortly before the release, Fox actually reduced the number of planned theaters, wary about the film’s dubious chances. (I swear I said at the time, what are they thinking?)

The film predicted by Variety to win the weekend,, The Santa Clause 3: The Escape Clause came in a respectable second on 3,458 screens, averaged $5,640 and totaled $19,504,038. Flushed Away was not far behind, on 3,707 screen, averaging $5,075 and totaling $18,814,323. It seems fairly obvious that the two family-oriented films split that audience, while the considerable non-family-oriented audience had one obvious choice.

This film was hyped to an extent that few $18 million movies are. A clip was posted on YouTube shortly before the release, as the EW article points out, and chat, photos, and reviews filled the internet. EW’s question was this: Would Borat suffer the fate of Snakes on a Plane? That film caused huge amounts of buzz in cyberspace but reaped somewhat disappointing ticket sales for a horror-thriller. The film’s worldwide box-office, $59,377,419 on a reported budget of $33 million, wasn’t great, but it wasn’t disastrous, either. I suspect DVD sales will be much higher and put the film in the black.

The semi-failure of Snakes has led to speculation, as in EW’s article, that maybe the internet isn’t as powerful a means of publicizing films as the studios hoped. Borat’s success demonstrates that we just plain don’t know yet. Probably in some cases, yes, in some cases, no—just as with other forms of publicity. EW assigns grades to films’ trailers. Maybe someday they’ll do the same for internet campaigns.

Sure, Borat was all over the internet, but it was also all over the other media. You had to be living in a lighthouse on Easter Island if you wanted to miss all the PR. Sasha Baron Cohen himself was everywhere, including the sidewalk in front of the White House, promoting the film. He wisely appeared as Borat rather than as himself, giving people beyond his relatively small existing fan base a vivid hint of what they could expect from the film. The hype fed upon itself as the regular print and broadcast media began to treat the film as news precisely because it was becoming ubiquitous—and because the colorful Cohen/Borat made for great infotainment.

Even as I was drafting this entry, boxofficemojo.com posted the estimates for the Friday-night box-office figures. Not surprisingly, the top three films of last weekend look set to become the top three films of this weekend. Borat’s percentage of drop between weekends will probably be pretty low, a sign of a film with good word-of-mouth in addition to hype. “Borat on a Plane?” EW asks. Clearly not.

I’m interested in the relationship between online interest and the success of films. When I say “online interest,” I mostly mean the many fan-created sites and chatroom discussion that range far beyond a studio’s own campaign in cyberspace. In The Frodo Franchise, I’ve got two chapters on the relationship of The Lord of the Rings to the online publicity, from official to highly unofficial. There the internet clearly made a difference and boosted the film’s success, for a variety of reasons. But for other films without a built-in fan base that break out and generate widespread interest in cyberspace—The Blair Witch Project being the most obvious exception—the case is not so clear.

The contrasting cases of Borat and Snakes on a Plane are fascinating, and I’m planning to write more about the subject when the DVD of the latter comes out on January 2 (complete with a “Snakes on a Blog” supplement). I’ll explore why the two met such different fates despite the apparent similarity of the build-up on the internet.

Originality and origin stories

Kristin here–

In the November 6 issue of Newsweek (also online), Devin Gordon comments on the recent trend in franchise series to throw in a prequel covering an earlier period in the main character’s life. “So-called origin stories—how fill-in-the-blank became fill-in-the-blank.”

At first David and I wondered whether Gordon, like so many film journalists, would go for the easy answer. There are at least two easy answers in the context of popular films, and especially blockbuster franchise films. One, their stories reflect something about the current psyche of the nation. Alternatively, they are symptoms of Hollywood running out of creativity and backbone and going for the tried and true.

The public psyche theory may sound profound at first, but it’s basically a quick way to write a story without knowing much of anything about film history or how the film industry works. There may be all sorts of reasons why a given kind of movie is made at a certain time. We all know about genre cycles. But society is vast and multi-faceted, and it isn’t hard to make any given film seem to “reflect” some aspect of it. Might the vogue for origins stories mirror a widespread desire to return to a more innocent era before 9/11? Bingo, you’re got your hook and can make your deadline. (Don’t get me started on the fact that most big films these days are negotiated, greenlit, planned, and in production for years before they appear, thus presumably reflecting not our own Zeitgeist but one that has come and gone.)

As to Hollywood running out of creativity, there are plenty of people in Tinseltown with great scripts and the desire to make them. We’re living in an age, though, when the big studios are owned by conglomerates. More than ever, the studio decision makers and the investors who buy their stocks keep an eye on the bottom line. Variety’s October 23 front-page story, “Less Dream, More Factory,” is on the layoffs and other cost-cutting measures that the big studios face. (By the way, we aren’t putting links to stories in Variety.com, since it’s a subscription-only site.) So the tactics of producers now must be to focus on exploiting the most popular characters and story premises for their tentpole projects.

Gordon recognizes this and puts his finger on a major reason for the vogue for “origin stories.” The studios have to prolong their most lucrative franchises, which are essentially their owners’ big brands. Yet those franchises can grow formulaic. One way to renew their energy can be to leap back in time.

Gordon opines, too, that “Ironically, playing it safe financially also provides studios with the cover to take creative chances.” He points to the fact that Peter Webber, who is directing Young Hannibal, has only the indie hit Girl with a Pearl Earring to his credit. Similarly, art-house darling Christopher Nolan gave one big franchise a new respectability and audience with Batman Begins and will try to continue to do so with The Dark Knight.

Linking origin stories to the hiring of such filmmakers is perhaps a bit of a stretch. The new Bond film, Casino Royale, the earliest in the order of Ian Fleming’s original novels, shows a younger agent. Much of the flashier high-tech props of recent entries in the series are apparently gone, with a grittier feel to the film. Yet it was directed by Martin Campbell, who also had made an earlier entry, GoldenEye, as well as both the Zorro films.

It’s true that recently Hollywood studios have shown a strange propensity to hire independent or foreign directors to helm entries in franchises. In the wake of his hit Once Were Warriors, New Zealand’s Lee Tamahori was imported and made Die Another Day and xXx: State of the Union. Warner Bros. brought in Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón (Y tu mamá también) to make the third Harry Potter film, presumably because many critics had dubbed the first two, by Chris Colombus, too bland. Perhaps the studios simply see franchises as needing shaking up at intervals. Yet this is part of a larger trend of indie directors suddenly boosted to blockbuster assignments, as when Doug Liman went from Go to The Bourne Identity and Mr. and Mrs. Smith.

An “origin story” in the sense that Gordon is using the phrase is a type of prequel that jumps back far enough to show the protagonist distinctly younger and different from the way he is in the original film or series. It then explains how he changed into that protagonist.

Hong Kong filmmakers are adept at prequels of this sort. God of Gamblers: The Early Years, shows us the source of the protagonist’s lucky ring and his taste for gold-wrapped chocolate, both of which are major motifs in the original God of Gamblers. The case of A Better Tomorrow is more complicated. John Woo and Tsui Hark had intended it to be a stand-alone film, and they made the mistake of killing off the most charismatic character. The film was such a hit, largely on the basis of Chow Yun Fat’s performance as Mark, that A Better Tomorrow II gave Mark a twin brother, Ken, and put Chow back in action. That film’s success led to a prequel to the first film. A Better Tomorrow III traces how the Mark character acquired his fighting skills and his signature costume and habits.

Origin stories are not entirely new to Hollywood, either. As far back as 1974, The Godfather Part II wove in flashbacks to a time well before the first film’s action, tracing Don Corleone’s rise. In 1979, there was Butch and Sundance: The Early Days.

Origin stories can be thought of as expansions of a basic convention of mainstream storytelling: the flashback to crucial formative moments in a character’s life. In that sense, perhaps the quintessential origin story is Citizen Kane. Today, when everything is potentially franchisable, such an early-days sequence can create a series. The prologue of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade shows young Jones launching upon an adventure that prefigures the man he will become. (In what surely is an inside joke, River Phoenix even acquires Harrison Ford’s chin scar.) That sequence in turn spawned The Chronicles of Young Indiana Jones TV series (“Before the world discovered Indiana, Indiana discovered the world”) and four cable movies.

As a term, “origin stories” was coined by students of mythology, who use it to refer to various ethnic groups’ accounts of the origin of the world. In that case, it didn’t have anything to do with what we now call prequels.

Then the term got taken up in discussions of comic books to identify the sort of thing that Gordon is talking about. Before television, comic books were the ultimate franchise form of the twentieth century. In comic franchises, particularly those centering on superheroes, a book or short series of books might be devoted to an origin story. (Dave Carter’s blog has a lengthy entry on comic-book origin stories, giving examples.) It’s not surprising that one of the main origin films, Batman Begins, came from the comics.

Gordon does not mention another reason why studios might want to continue a franchise by jumping back to the hero’s origins: actors can age too much to continue a role. It’s been over 14 years since The Silence of the Lambs, and Anthony Hopkins could probably not be convincing in another turn as Lecter. Possibly we’ll get a chance to see whether a 60-something (or 70-something at the rate things are going) Harrison Ford can bring audiences in for the on-again-off-again Indiana Jones continuation. Or actors may exit the franchise, as Jody Foster did before Hannibal. Or grow up too quickly, as the Harry Potter kids are doing before our eyes. Or die, as Richard Harris did in the same series, forcing Warners to substitute Michael Gambon as Dumbledore.

But origin stories don’t have these problems. Just get new actors. One thing tentpole franchise films have taught us is that, as strongly identified with a character as a star may become, if the character and premises are even stronger, a new actor will be accepted. It’s happened with Batman, Superman, Bond, and almost did—and could yet–with Spider-Man.

Such stories, however, have their dangers as well. If the audience is devoted to the character as he (and it’s mostly he so far) is, will they care about seeing him as a very different person? If Hannibal Lecter is the middle-aged psychopath we love to hate, do we want to learn that he was once a vulnerable, suffering youth?

The End of cinema as we know it—yet again

Kristin here—

Our friend Brian Rose kindly send us a recent article from the Wall Street Journal, Joe Morgenstern’s “Set the DVD Player to ‘Random’” (28 October 2006, p. 10; the WSJ website is by subscription and wouldn’t let me link to the article). In it Morgenstern claims that iPods playing songs in random order, video games offering constant choice, multi-tasking, and all the supposedly distractive aspects of modern life are wrecking movie logic. The latest evidence? A new release called The Onyx Project, an inexpensively produced interactive movie starring David Strathairn that allows its viewer to wander through the narrative in random order.

According to Morgenstern, The Onyx Project is just further indication that “The entire entertainment industry is beset by fragmentation, both economic and perceptual. Kids who used to turn out for movies every weekend now devote themselves to videogaming, instant messaging, MySpacing and YouTubeing, sometimes simultaneously, while movie executives, pacing studio corridors, worry rightly that they no longer understand how kids’ minds work.” (Haven’t studio execs always paced and worried about how to understand spectators’ minds?)

Morgenstern even cites Pauline Kael’s essay, “Are Movies Going to Pieces?” where she cited the “creeping Marienbadism” in modern cinema. If only! Yes, I can just see today’s teenagers lamenting the fact that Last Year at Marienbad is out of print on DVD and searching eBay for it. Morgenstern simultaneously cites Marienbad as having brought fragmentation into the movies and praises such art films as Breathless, L’Avventura, and Caché, as well as sophisticated Hollywood storytelling in The Matrix and The Godfather Part II. But again, if fragmentation is what kids want, why aren’t they watching Caché?

It’s hard to know where to begin.

For a start, the makers of The Onyx Project declare on its website, “But NAVworlds are not movies.” (NAV stands for “Non-Linear Arrayed Video.”) Further, “They are not ‘interactive movies.’” The site compares these NAVworlds, quite logically, to videogames, but there’s a difference: “Video games present worlds. We love video games. But video games are programmed. NAVworlds are written, directed, acted and edited.” It’s a subtle distinction, but the point is, The Onyx Project is probably closer to a game than a movie. The fact that it is available only as a piece of software playable in computers but not in DVD players should be a clue.

But whatever we call The Onyx Project, is it really totally fragmented? Richard Siklos’ more temperate New York Times review, “In This Movie, the Audience Picks the Scene” (2 October 2006) points out that The Onyx Project retains some of the traits of a Hollywood narrative. “One idea behind the venture,” he declares, “is that no two viewers may see the movie unfold in the same way, yet its basic facts, characters and message will permeate the experience.

Sounds like a type of unity to me. Moreover, “The mystery at the center of the story is not revealed until the end.” Suspense and curiosity are maintained, controlled not by the viewer/player but the makers.

Let’s go back to that “The entire entertainment industry is beset by fragmentation” claim. One of the reasons that The Onyx Project is creating a little stir is that it is so atypical. These kinds of experiments in time shifting are often used specifically for mysteries, traditionally the genre where the story starts the latest in the action and then backtracks for the final reveal. Think Memento, The Usual Suspects, or any of the neo-noir follow-ups to Pulp Fiction.

In 1985 when Hollywood attempted to introduce a mild form of forking-paths storytelling into theatrical filmmaking, they chose Clue, not only a mystery but a game. Then viewers simply saw one of three possible endings. Presumably the spectator was supposed to be intrigued by this gimmick and see the film three times. Few proved willing to sit through it even once, and the film flopped. Naturally all three endings were included in the video release, giving the viewer a mild dose of interactivity. Now the technology has caught up to make this approach far more sophisticated and intriguing.

More important, though, is the fact that most movies that young people see in theaters are not fragments or shuffled in challenging ways. Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest may have been too long, but its cause-effect flow wasn’t fragmented, and it has earned over a billion dollars worldwide. Look at the most popular and/or lauded films of the past decade: Titanic, The Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, A Beautiful Mind, Spider-Man, Finding Nemo … the list could go on and on. These films are linear and causally tight for the most part, and when something is unclear, it’s a mistake, not a deliberate strategy. Even The Sixth Sense (another mystery of sorts) is easy to follow, and the twist, though genuinely surprising for most, is not baffling. A truly fragmented narrative is hard to find, in part because these sorts of films appeal to a very broad audience and have to be comprehensible if they are to succeed.

It’s easy to link the coincidence of the invention of gadgets like iPods with the trend toward Memento-like trickiness. As usually happens if one looks closely, though, complex narratives of this sort predate modern forms of interactivity. Even apart from the art cinema (whose main audiences from the end of World War II well into the 1970s and 1980s contained a large number of college students and graduates), there are Hollywood films that play with time in pretty sophisticated ways. In the 1940s there were the films noir, like Double Indemnity and The Locket, the latter with its flashbacks nested like matrioshki dolls. Later on but still in the pre-iPod era, there were playful films like Groundhog Day (1993) and Pleasantville (1998). MTV and the 1970s generation of American auteurs brought up on art cinema probably had more impact on story-telling than the iPod and similar devices have.

Moreover, even in traditional arts where interactivity would seem highly unlikely, one can find occasional works that offer choices. The Choose Your Own Adventure series of children’s books (1979 to the present) include numerous options about how to proceed. (Greg Lord offers an analysis of one of the books.)

Besides all that, the shuffle feature on iPods is usually used for songs, which are short, self-contained artworks. I doubt that people watching old episodes of Moonlighting on their video iPods skip among chapters randomly.

One thing most people tend to forget (if they ever knew it) is that in pre-television days, when movie theaters were a lot fuller than they tend to be now, there were continuous screenings. That meant the times when the screenings would start were not typically given in ads, and people just went to the theater, often standing in line until a seat became available. A lot of people ended up coming in in the middle of the feature and just sat through until they got to that point again. They didn’t seem to be much bothered by the fact that the film was “fragmented” in a random way. (In Storytelling in the New Hollywood I argue that comprehension was aided by a considerable redundancy in the flow of narrative information. David picks up on that idea in The Way Hollywood Tells It.) Notably, among the first theaters to list start times and sell reserved seats were early art houses, presumably because the more challenging films shown there were less easy to grasp unless seen beginning to end.

If The Onyx Project succeeds, it may usher in a new storytelling medium somewhere between films and videogames. If not, it will be the Clue of its day. Either way, most filmmakers in Hollywood and elsewhere will continue to try and make movies with stories that people can easily follow.