Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Oscars by the numbers

Director Chris Butler: “Well, I’m flabbergasted!” with producer Arianne Sutner.

Kristin here:

The Oscars are looming large, with the presentation ceremony coming up February 9. But did they ever really go away? As I’ve pointed out before, Oscar prediction has become a year-round obsession for amateurs and profession for pundits. I expect on February 10 there will be journalists who start speculating about the 2020 Oscar-worthy films. The BAFTAs (to be given out a week before the Oscars, on February 7) and Golden Globes have also become more popular, though to some extent as bellwethers of possible Oscar winners. The PGA, DGA, SAG, and even obscure critics groups’ awards have come onto people’s radar as predictors.

How many people who follow the Oscar and other awards races do so because they expect the results to reveal to them what the truly best films of the year were? How many dutifully add the winners and nominees to their streaming lists if they haven’t already seen them? Probably quite a few, but there’s also a considerable amount of skepticism about the quality of the award-winners. In recent years there has arise the “will win/should win” genre of Oscar prediction columns in the entertainment press. It’s an acknowledgement that the truly best films, directors, performers, and so on don’t always win. In fact, sometimes it seems as if they seldom do, given the absurd win of Green Book over Roma and BlacKkKlansman. This year it looks as if we are facing another good-not-great film, 2017, winning over a strong lineup including Once upon a Time in … Hollywood, Parasite, and Little Women.

Still, even with a cynical view of the Oscars and other awards, it’s fun to follow the prognostications. It’s fun to have the chance to see or re-see the most-nominated films on the big screen when they’re brought back to theaters in the weeks before the Oscar ceremony. It’s fun to see excellence rewarded in the cases where the best film/person/team actually does win. It was great to witness Laika finally get rewarded (and flabbergasted, above) with a Golden Globe for Missing Link as best animated feature. True, Missing Link isn’t the best film Laika has made, but maybe this was a consolation prize for the studio having missed out on awards for the wonderful Kubo and the Two Strings and other earlier films.

It’s fun to attend Oscar parties and fill out one’s ballot in competition with one’s friends and colleagues. On one such occasion it was great to see Mark Rylance win best supporting actor for Bridge of Spies, partly because he deserved it and partly because I was the only one in our Oscar pool who voted for him. (After all, I knew that for years he had been winning Tonys and Oliviers right and left and is not a nominee you want to be up against.) Sylvester Stallone was the odds-on favorite to win, and I think everyone else in the room voted for him.

Oscarmetrics

Pundits have all sorts of methods for coming up with predictions about the Oscars. There’s the “He is very popular in Hollywood” angle. There’s the “It’s her turn after all those nominations” claim. There are the tallies of other Oscar nominations a given title has and in which categories. And there is the perpetually optimistic “They deserve it” plea.

Pundits have all sorts of methods for coming up with predictions about the Oscars. There’s the “He is very popular in Hollywood” angle. There’s the “It’s her turn after all those nominations” claim. There are the tallies of other Oscar nominations a given title has and in which categories. And there is the perpetually optimistic “They deserve it” plea.

For those interested in seeing someone dive deep into the records and come up with solid mathematical ways of predicting winners in every category of Oscars, Ben Zauzmer has published Oscarmetrics. Having studied applied math at Harvard, he decided to combine that with one of his passions, movies. Building up a huge database of facts from the obvious online sources–Wikipedia, IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, the Academy’s own website, and so on–he could then crunch numbers in all sorts of categories (e.g., for supporting actresses, he checks how far down their names were in the credits).

An early test of the viability of the method came in the 2011 Oscar race, while Zauzmer was still in school. That year Viola Davis (The Help) was up for best actress against Meryl Streep (The Iron Lady). Davis was taken to be the front-runner, but Zauzmer’s math gave Streep a slight edge. Her win reassured Zauzmer that there was something to his approach. His day job is currently doing sports analytics for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Those like me who are rather intimidated by math need not fear that Oscarmetrics is a book of jargon-laden prose and incomprehensible charts. It’s aimed at a general public. There are numerous anecdotes of Oscar lore. Zauzmer starts with Juliet Binoche’s (The English Patient) 1996 surprise win over Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) in the supporting actress category. Bacall was universally favored to win, but going back over the evidence using his method, Zauzmer discovered that even beforehand there were clear indications that Binoche might well win.

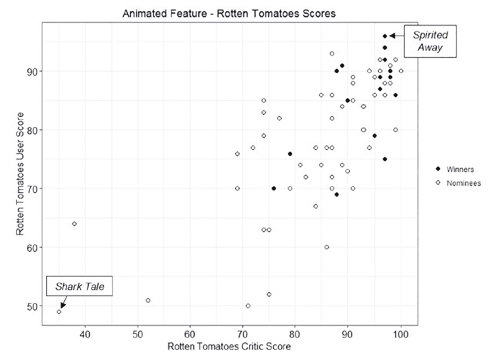

Zauzmer asks a different interesting question in each chapter and answers it with a variety of types of evidence. The questions are not all of the “why did this person unexpectedly win” variety. For the chapter on the best-animated-feature category, the question is “Do the Oscars have a Pixar bias?” It’s a logical thing to wonder, especially if we throw in the Pixar shorts that have won Oscars. Zauzmer’s method is not what one might predict. He posits that the combined critics’ and fans’ scores on Rotten Tomatoes genuinely tend to reflect the perceived quality of the films involved, and he charts the nominated animated features and winners in relation to their scores.

The results are pretty clear, in that Spirited Away is arguably the best animated feature made in the time since the Oscar category was instituted in 2001. In fact, I’ve seen it on some of the lists of the best films made since 2000, and it’s not an implausible choice either way. Shark Tale? I haven’t seen it, but I suspect it deserves its status as the least well-reviewed nominee in this category.

The results are pretty clear, in that Spirited Away is arguably the best animated feature made in the time since the Oscar category was instituted in 2001. In fact, I’ve seen it on some of the lists of the best films made since 2000, and it’s not an implausible choice either way. Shark Tale? I haven’t seen it, but I suspect it deserves its status as the least well-reviewed nominee in this category.

Using this evidence, Zauzmer zeroes in on Pixar, which has won the animated feature Oscar nine times out of its eleven nominations. In six cases, the Pixar film was the highest rated among that year’s nominees: Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, WALL-E, Up, Inside Out, and Coco.

In two cases, Pixar was rated highest but lost to a lower-rated film: Shrek over Monsters, Inc., and Happy Feet over Cars. I personally agree that neither Shrek nor Happy Feet should have won over Pixar. (Sorry, George Miller!)

Zauzmer finds three cases where Pixar did not have the highest rating but won over others that did: Ratatouille beat the slightly higher-rated Persepolis, Toy Story 3 should have lost to the similarly slightly higher-rated How to Train Your Dragon, and Wreck-It Ralph was way ahead on RT but lost to Brave. Wreck-It Ralph definitely should have won, and the sequel probably would have, had it not been unfortunate enough to be up against the highly original, widely adored Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse.

The conclusion from this is that the Academy “wrongly” gave the Oscar to Pixar films three times and “wrongly” withheld it twice. As Zauzmer points out, this is “certainly not a large enough gap to suggest that the Academy has a bias towards Pixar.” This is pleasantly counterintuitive, given how often we’ve seen Oscars go to Pixar films.

Oscarmetrics offers interesting material presented in an engaging prose style, more journalistic than academic, but thoroughly researched nonetheless.

In his introduction, Zauzmer points out that the book only covers up to the March, 2018 ceremony. It obviously can’t make predictions about future Oscars, though it might suggest some tactics you could use for making your own if so inclined. Zauzmer has been successful enough in the film arena that he writes for The Hollywood Reporter and other more general outlets. You can track down his work, including pieces on this years Oscar nominees, here.

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

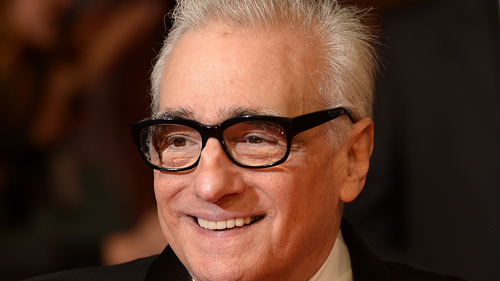

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

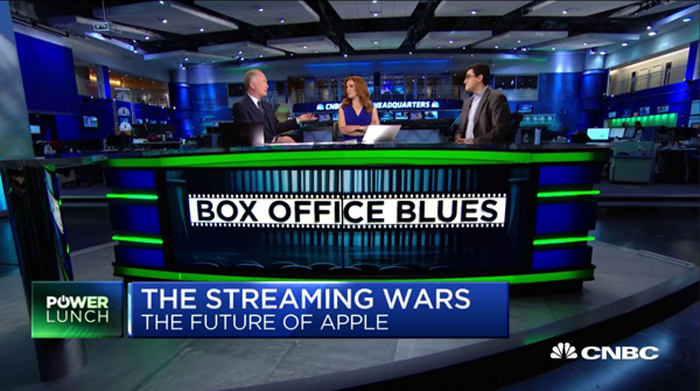

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).

So was there an actual box-office slump in 2019?

Kristin here:

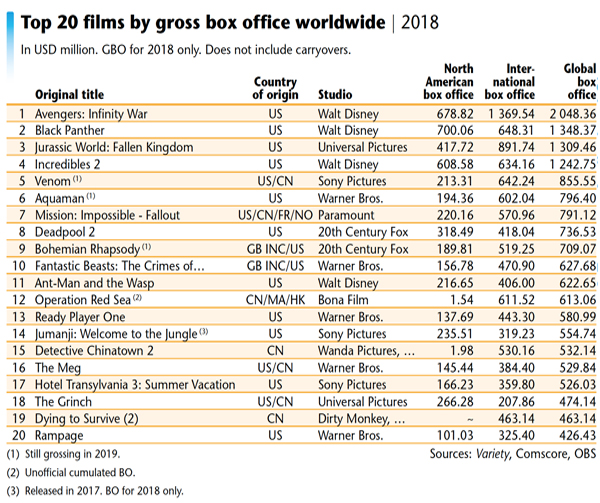

Last May, I posted an entry responding to all the lamentations about a supposed slump in box-office revenues for theatrical films in the early months of 2019 compared with the same period of 2018. I pointed out that the cause of the slump was not due, or at least not entirely due, to a sudden lack of interest in movie-going resulting from the rise of streaming. The main reason was that most of the biggest BO hits of 2018 had been released earlier in the year than usual. As a result, most or all of their income came entirely within the calendar year. In tallying annual BO, however, money brought in after December 31 gets added onto the new year’s tally.

Thus the fact that the four biggest hits 2018, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Incredibles 2, and Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom, all came out in the summer or earlier. No revenues from these films carried over into 2019. That almost inevitably meant that there would be a decline in 2019, but it wasn’t due to people deciding to camp out on their couches and watch stuff streamed to their TV sets. They had simply bought their tickets to those movies long before.

For some reason, pundits never seem to notice this. Or maybe some do, but, as I wrote last May, it’s much more dramatic to tear one’s hair over a dire slump than to point out that these ups and downs really don’t reflect any dramatic changes in the overall industry, at least not yet. Also, it’s more difficult to figure out and then explain the results of the fact that films still in release at year’s end have their grosses divided between two calendar years.

Assuredly there has been big shifts in the balance of power among the major studios. Obviously Disney is doing very well indeed, with seven films in the top ten domestic grossers for 2019, including all the top six. In contrast, Paramount, long ago the most powerful studio in the young Hollywood, is in a sad state. Quite possibly it will disappear into a larger firm, as 20th Century-Fox did. This imbalance within the current industry is not good for any of them apart from Disney, but it has so far had no discernible effect on the industry’s earning power as a whole.

Annual box-office totals, in numbers not adjusted for inflation, are percolating along as usual. There was no slump last year, just a little adjustment downward after a record year. Let’s take a look at what’s really going on.

Up and up, and down, and up and up

We’re barely into 2020 and already the trade papers are pointing out that the domestic box-office total for American theatrical films fell in 2019. Yes, but …

Here’s a chart from Box Office Mojo of the grosses since 2009, the first year when the figure topped $10 billion. (These figures are in dollars unadjusted for inflation. The three columns on the right side are number of features released, average take per film, and the top grosser of the year.)

Note for a start that there was a 7.4% rise in 2018 over 2017. In 2019 there was a drop of 4.8%. Now note that the decline of 4.8% in 2019 still left the total higher than it had been in 2017. Note also that this has usually been the case. The years of big growth–10% in 2009, 6.5% in 2012, 7.4% in 2015 and 2018–are followed either by smaller rises or by declines that do not wipe out the gains of the previous years.

If you look at the larger chart from which this was excerpted, it’s much clearer that theatrical income has risen impressively.

BO has nearly quadrupled from 1985 (again, in unadjusted dollars, so a significant part of that growth is inflation). In 1985 the total was a mere $3,041,480,248. Since then there have been 27 up years (though a few were nearly flat) and only 7 down years. Down years tend, not surprisingly, to come after record years. In 2014, there was a decline somewhat greater than that of 2019. Between 2014 and 2019, the total BO rose by 14.4%. About half of that, 7.4%, was in 2018, almost inevitably leading to a decline in 2019. But really, is a 4.8% decline that big a deal in comparison with a 14.4% rise? The basic point is that the BO continues to climb overall, despite these occasional “adjustments,” as business people would call them.

Moreover, note that 87 more features were released in 2018 than in 2019, and considerably more films than in previous years. Given the average box-office gross in 2018, that would add a little over a billion dollars. In fact the difference between the 2018 and 2019 totals was only about $570 million, so presumably some of those extra films brought in well under the average. Still, some of the record year was due simply to a greater number of films. Conversely a drop in the number of 2019 films to something closer to normal does not suggest a slump due to waning interest in theatrical movie-going.

Writing in Hollywood Reporter in November, 2019, Pamela McClintock made the 4.8% drop sound like a big deal, even while acknowledging that in fact 2019 would be the second biggest BO year in history (in unadjusted dollars, of course). McClintock’s figures differ slightly from the chart above, partly because final tallies were not in and partly because she used Comscore figures instead of Box Office Mojo ones.

With Dec. 31 fast approaching, industry leader Comscore projected Sunday that box office revenue in North America will hit $11.45 billion for the full year, a decline of 3.6 percent from 2018’s record bounty of $11.88 billion.

If Comscore’s rough estimate is correct, that would be the biggest year-over-year decline since 2014, when domestic revenue tumbled a steep 5.1 percent over 2013 to $10.36 billion. The North American box office rebounded in a major way in 2015, rising 7.5 percent to $11.13 billion.

The good news: $11.45 billion would represent the second-best showing of all time, besting the $11.38 billion collected in 2016 (a 2.2 percent uptick). Underscoring the cyclical nature of the film business, revenue was down 2.3 percent in 2017, followed by last year’s dramatic 6.9 percent jump.

While international box office numbers aren’t yet tallied for 2019, analysts expect worldwide ticket sales to match, or best, last year’s all-time high of $41.1 billion.

“Given the level of competition from a plethora of options across multiple platforms on an incalculable number of devices, it should be actually heartening to the industry that 2019 will deliver the second-best annual box office revenue in history,” says Paul Dergarabedian of Comscore.

Yes, it should, but again, second-best is not as dramatic as a worrisome slump. After all, the threat of streaming to theatrical business is the big story of recent show-biz journalism.

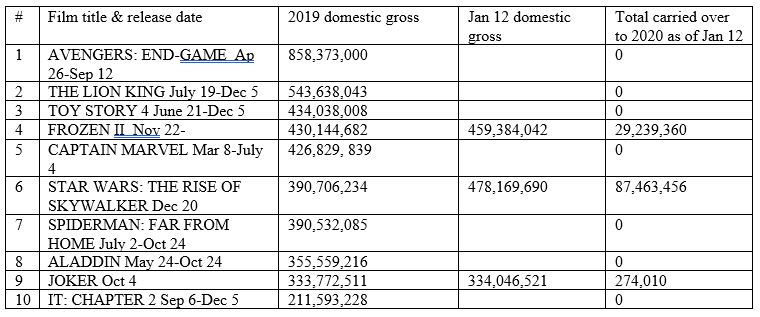

Carry-over into 2020

Is there likely to be much carry-over of box-office revenues from 2019 films into 2020? In other words, is there likely to be a repeat of 2019, with too many big grossers released well before the end of the year? It does seem possible. My home-made chart above, derived from Box Office Mojo figures as of January 12, 2020, shows that seven of the top ten domestic-earners went into and out of release in the spring or summer, somewhat as the comparable films from 2018 did. Of the three films still in release, Frozen II and especially Joker seem to have already earned much of what they will earn. (Indeed, Frozen II has already slightly outpaced my prediction, based on the gross of the original Frozen in adjusted 2019 dollars, $441.8 million.) The Star Wars entry, the latest release in the top ten, is still going strong and should contribute a fair amount.

1917 will provide most of its income to the 2020 figures. It opened in only eleven theaters on Christmas Day, stayed at that level for two weeks, and went wide (into 3434 theaters) on January 10, meaning that all but $2,721,279 of its domestic income will count for 2020. The film’s surprise Golden Globes wins and possible BAFTA and Oscar awards may help land it a higher gross than many would have predicted. As of January 15 it had grossed $51,561,309 domestically and was still at number one.

It’s way too early to predict what effect all the as-yet unearned carryover money from 2019 films will have on the 2020 total we’ll be discussing a year from now. I haven’t yet bothered to survey the new year’s anticipated blockbusters and their release dates. If studios continue to scatter their big earners throughout the year instead of saving them for the November-December holiday season, then carry-over income will be less significant and will perhaps cause fewer ups and downs. If so, pundits will need to find something else to make us nervous as regards the future of movie-going.

That something should not be the extremely common claim by journalists that streaming is killing theaters. It has been shown that people who stream more movies also go to more movies in theaters.

A final point

While noting in passing that 2019 both suffered a big decline and was the second-biggest BO year, Rebecca Rubin of Variety pointed out that the global box-office haul for 2019 hit $31.1 billion, the first time it has ever topped $30 billion. This rise in part reflects the fact that nearly 70% of Avengers: Endgame‘s total grosses came outside the US/Canadian market.

Rises in foreign ticket sales don’t entirely compensate for declines in domestic ones. Not as great a percentage of the box-office income returns to the American studios from some markets–notably China, which pays back 25%, as opposed to closer to 50% from other markets. (Ryan Faughnder and Robin Dixon summarized that and other problems faced by American films in the Chinese market for the Los Angeles Times last February.) But any foreign income helps, and so far the foreign markets continue to rise, even as streaming penetrates more of them.

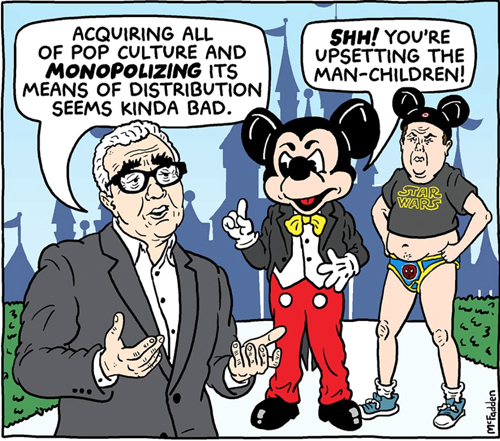

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

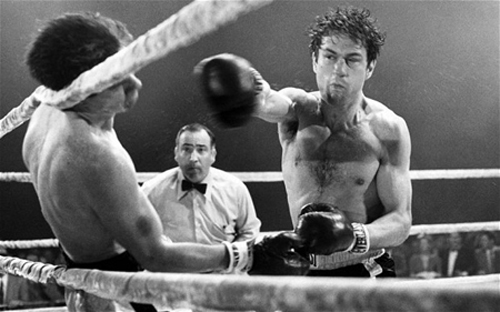

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

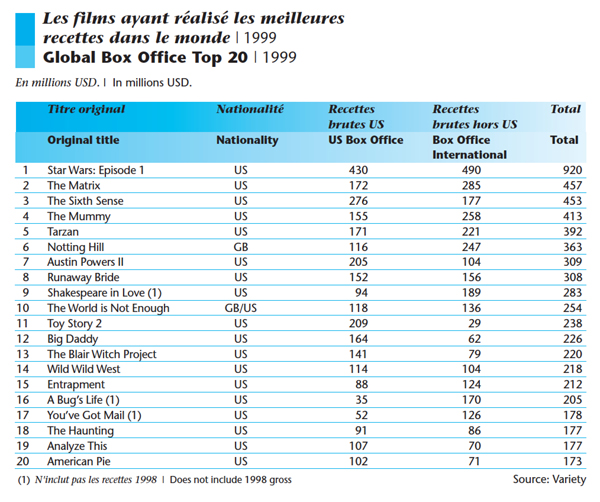

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

Now consider the 2018 situation.

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.

I’m just spitballing here, but for Scorsese and other stylized realists like Michael Mann, the comic-book convention of eternal return might seem merely juvenile wish fulfillment. Something really has to be at stake, and ultimates must be faced’ Danger and death are real. This is grown-up drama.

I’m not intrinsically opposed to the conventions ruling comic-book movies myself. In general, I think that plot is as underrated as character is overrated. (I’d rather give up the distinction altogether, but that’s another story.) Superhero films are mostly not to my taste, but I think they’re worth studying as intriguing contributions to trends in modern cinema. My point is just that the personal aesthetic of Scorsese, as both cinephile and cineaste, doesn’t fit very well with the elaborate, ever-changing rules of the magical MCU. He finds enough magic in a sinuous tracking shot, or a carefully synced doo-wop song, or an unexpected angle, or a wiseguy shouting match. That is Cinema.

There are other questions we might ask about Scorsese’s remarks. For instance, when he celebrates the thrill of communal moviegoing as a central feature of Cinema, he seems to ignore the fact that the franchise pictures are our prime multiplex attractions. Many viewers slot the more “personal films” into a future Netflix queue, but they commit themselves to seeing the big films on the big screen. That choice can yield contemporary viewers some of the electricity that Scorsese found at a screening of Rear Window. And when they’re not checking their text messages or chatting loudly with their pals, they might even give themselves up to laughs, screams, and applause, just as in the old days.

Since I wrote this, though, something much more draconian than superhero pictures may threaten non-franchise pictures. On Monday, Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim said that the Department of Justice is moving to end the consent decrees that have governed Hollywood studio conduct since 1948. (See here and here.)

The implications of this are staggering. We may see the return of block and blind booking, the prospect that a studio could own a theatre chain (and give favored place to its own pictures), and the decline of independent producers and art houses that favor smaller films. Nonsensically, Delrahim quoted an earlier Scorsese remark about his craft: “Cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Delrahim went on: “Antitrust enforcers, however, were not cast to decide in perpetuity what’s in and what’s out with respect to innovation in an industry.” Thus the ideology of predatory “disrupters” goes on, and even auteurs are unwillingly recruited to the enterprise.

Thanks to Jim Danky for calling my attention to the McFadden comic, and to Jeff Smith for discussions of Scorsese’s arguments. Thanks as well to Colin Burnett for discussion of the Bond saga.

My lists of top-twenty films come from the European Audiovisual Observatory’s publications Focus 1999 and Focus 2019.

I’ve left aside other writers’ analyses of Scorsese’s views. I benefited from reading Ben Child and Helen O’Hara in The Guardian, Christopher Orr’s older review in The Atlantic, and Zachary Zahos at Playback. Also pretty forceful is Kevin Feige’s defense of the MCU, which I discovered only after writing this entry. He argues for Marvel films’ value on several grounds, including their display of positive social values. And just before I posted this, the Russo brothers weighed in.

Here are other Scorsese comments made before the New York Times piece appeared. After his BAFTA David Lean lecture on 12 October, he reiterated his view.

Theatres have become amusement parks. That is all fine and good but don’t invade everything else in that sense. That is fine and good for those who enjoy that type of film and, by the way, knowing what goes into them now, I admire what they do. It’s not my kind of thing, it simply is not. It’s creating another kind of audience that thinks cinema is that. If you have a child and the child wants to see the picture, what are you going to do? It’s up to you. The audience that sees them now, the fans that see those pictures now, they were raised on pictures like that.

The technique is very well done, but there is only one Spielberg, only one Lucas, James Cameron, it’s a different thing now. It’s an invasion, so to speak, in the theatre. . . .

We are in a moment not only of evolution but of revolution, in pretty much the whole world, everything we know, the old political systems, it’s almost as if the 21st century is beginning now and technology has gone with it and that means cinema goes with it.

Yes, see a movie in a theatre, it’s the best with an audience, but the actual concept of cinema has become something that is not definable. Something can play as a hologram, something can play as virtual reality, maybe there is going to be an extraordinary epic in virtual reality at some point. We have to start expanding what we think of as narrative, music, literature, art and particularly the visual image.

Granted, this whole passage is a bit baffling. It’s not completely clarified in a press conference the next day at the BFI London Film Festival. The relevant section starts at 16:26.

It’s also interesting that Benedict Cumberbatch (aka Dr. Strange) defends the need for auteurs.

Some comments on Sarris’s career and the vagaries of auteur theory are here. I discuss Black Panther and its debt to classical Hollywood storytelling here.

Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas (2007).