Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

When worlds collide: Mixing the show-biz tale with true crime in ONCE UPON A TIME . . . IN HOLLYWOOD

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Jeff Smith here:

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood might turn out to be the buzziest film of 2019. Some of this water-cooler talk is due to its unusual status within an ever-enlarging field of true crime stories. (Call it a “not quite true” crime story.) Indeed, the genre is hotter than ever thanks to a bevy of new podcasts, telefilms, and miniseries.

Industry analysts, though, are also keen to interpret Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office fortunes. As that rare big summer release that is neither a sequel nor a franchise title, it can be seen as a test of whether original content can survive amidst heavily marketed, presold tentpoles.

The lesson so far? To quote William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything.” In The Washington Post, one unnamed studio executive warned, “I don’t see any blue-sky meaning here.” The executive added, “This movie has assets that almost no other film has. That’s what drove it.” At least one of those assets is Tarantino himself, who is a brand, if not a franchise. Fans know what to expect in a Tarantino film, which is why the film is sui generis when it comes to this summer’s slate. Due to its unique IP, it can’t really be compared with films like Men in Black International or Spider-man: Far from Home. Yet thanks to Tarantino’s larger than life presence, it also isn’t Long Shot or Booksmart or Stuber.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is catnip to Tarantino nerds like me. It has the usual surfeit of references to obscure films and television shows. Some of these are deftly interwoven into the story itself. It boasts a carefully curated soundtrack that unearths “some-hits” wonders. It also contains scenes depicting nasty yet comical violence, a hallmark of Tarantino’s work ever since Reservoir Dogs.

At first blush, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would seem to be Tarantino’s most linear film. Yet it still displays certain continuities with his oeuvre in terms of story structure and technique. Although the film eschews the chapters and title cards found in Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, it still contains elements of what David calls “block construction.” In the case of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, it is all about threes. The plot is structured around three days in the winter and summer of 1969: February 8th, February 9th, and August 9th. Each “chapter” is introduced showing the date via superimposed text. And all three chunks of narrative crosscut among the activities of three actors – Sharon Tate, Rick Dalton, and Cliff Booth – as they try to adapt to changes in the film and television industries.

If all of this assures that you’d never mistake Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as the work of another director, other elements show Tarantino striking out in new directions. Chief among these is his mash-up of two normally distinct story types: the show-biz tale and the true crime yarn. Think of it as Singin’ in the Rain meets In Cold Blood. In what follows I outline some of the ways that Tarantino adapts his signature style to two well-established storytelling options: the multiple draft narrative and the network narrative. I also consider the effects Tarantino’s counterfactual history has on the conventions of the show-biz tale and the celebrity biopic.

My analysis contains major spoilers. If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, stop reading now!

My world and welcome to it

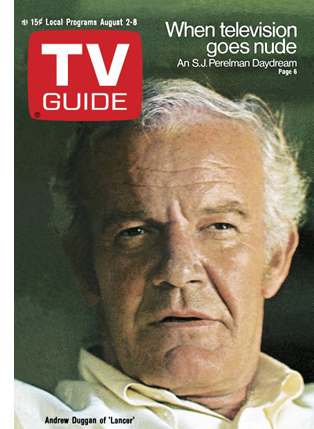

Quick trivia question: what actor was on the cover of TV Guide during the week that Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family? Sharp viewers of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should know the answer. We see Tate’s housemate, Woychiech Frykowski, reading that issue of the magazine as he watches Teenage Monster on late night television.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Tarantino’s film treats this little bit of pop culture ephemera as an uncanny coincidence. It simply becomes yet another way that he can intertwine the destinies of his three protagonists. But that brief shot got me thinking: did Tarantino start with the idea that he’d recreate whatever series was featured on TV Guide the week Tate was killed?

If so, Rick might have appeared just as easily as an aspiring cartoonist next to William Windom on the NBC sitcom, My World and Welcome to It. The show debuted just six weeks after Tate’s death. It is not unthinkable that NBC would have pushed for a cover on TV Guide in an effort to promote the premiere. Yet Tarantino’s counterfactual history in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would have been vastly different if that had been the case.

Did Tarantino really base his screenplay on this conceit? I doubt it. Lancer fits so snugly into the world that the director captures onscreen that it is not be so easily replaced. Tarantino seems to have a nostalgic fondness for the show, much as I did in my wasted youth. (I recall having a Lancer lunchbox at age six.) Production designer Barbara Ling describes the steps she took to recreate Lancer’s mix of Spanish/Western design. This involved adding adobe storefronts to the wooden ones, and substituting iron coils for wooden pegs on the saloon’s staircase. Ling added, “This was a [rich] cattle town and the buildings are two and three stories. It’s not Deadwood.”

Many critics have characterized Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as another hangout movie. This is Tarantino’s designation for a film that is leisurely paced, fairly light on plot, and mostly gives the audience a chance to spend time with the characters. Indeed, because of these qualities, reviewers often compare Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood to Jackie Brown, a film that Tarantino himself compared to Rio Bravo, which was Howard Hawks’ hangout movie.

The resemblances don’t stop there. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s three-headed protagonist bears certain similarities to Jackie Brown’s Jackie, Ordell, and Max.

Yet while watching Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I felt this film, more than any of Tarantino’s others, was an exercise in world-building. Normally we associate that term with sci-fi, fantasy, and comic book movies. It is especially important for transmedia properties where the fictional universe depicted exceeds the bounds of any individual film, television series, book, or video game.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is also an alternate history, a type of speculative fiction also common in sci-fi and comic book stories. The Avengers: End Game and Spider-man: Into the Spiderverse are both relatively recent examples. This suggests a loose affiliation between Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood and other blockbusters even as Tarantino tweaks that formula by situating his speculative fiction within the generic framework of true crime.

Tarantino largely avoids the industrial motivations behind these two narrative techniques commonly seen in tentpoles. Instead, he simply recreates the pop culture world of his youth. In doing so, the director’s real world, his “realer than real” universe, and his “movie movie” universe all collide.

Keepin’ it real (and realer)

As Tarantino has explained in interviews, the “realer than real” universe is an alternate reality close to our own where his fictional characters can intermingle with real people. The “movie movie” universe, on the other hand, is a more overtly fantastic world closer in spirit to comic books or exploitation films. The characters have unusual abilities or even supernatural powers. The “movie movie” thus downplays the realistic motivations usually found in the “realer than real.” In Tarantino’s oeuvre, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance exemplify the “realer than real.” Kill Bill and From Dusk to Dawn are instances of the “movie movie.”

Each universe features a web of connections that can link particular tales together. For example, Kill Bill’s Sheriff Earl McGraw and his son Edgar pop up in Death Proof. Similarly, Lee Donowitz, the cocaine-sniffing movie producer in True Romance, is purportedly the son of Sgt. Donny Donowitz, the “bear Jew” in Inglourious Basterds.

In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the most obvious references to these two Tarantino universes are the fictional brands he has created. During the end credits, we see Rick in a TV ad for Red Apple cigarettes. According to a Tarantino wiki, “ads or packs of these flavorful smokes” can be seen in The Hateful Eight, Inglourious Basterds, Planet Terror, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, From Dusk till Dawn, Four Rooms and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. (The latter is an obvious outlier. Yet the Red Apple nod was likely an in-joke related to Tarantino’s offscreen romance with Mira Sorvino, who played Romy.)

Similarly, Tarantino’s fictional fast food chain, Big Kahuna Burger, appears on a bus billboard in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. It previously was featured in a memorable scene in Pulp Fiction. (“That’s a tasty burger!”) But it had already debuted as a delicious snack devoured by Mr. Blonde in Reservoir Dogs. Big Kahuna later comes back in two other Tarantino films, From Dusk Till Dawn and Four Rooms, as well as Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.

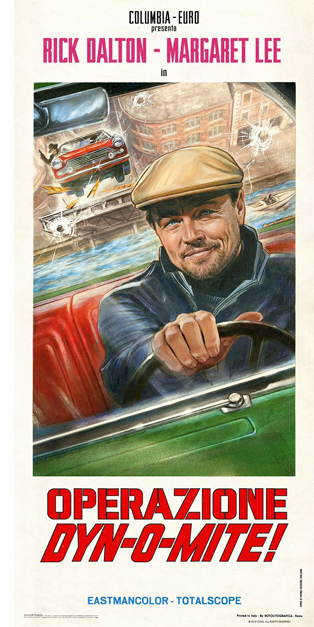

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Much of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes from the way Tarantino overlays these three universes to create a singular fictional world. For example, at one point we learn that Rick was considered for the role of Captain Virgil Hilts, the part played by Steve McQueen in John Sturges’ The Great Escape. Tarantino even inserts digitally altered footage of The Great Escape to show us a scene of Rick as Hilts. Since Rick claims he never met Sturges, this moment appears to represent an imagined version of the film that could exist in some type of alternate history. It invites us to consider how different Rick’s career might have been had fortune smiled upon him instead of McQueen.

To disentangle this knot, one must surmise that The Great Escape and Steve McQueen belong to both the real world and the “realer than real” world. Yet the scene of McQueen at the Playboy mansion and Rick describing his missed opportunity can only belong to the “realer than real.” And the character of Hilts himself exists only in the “movie movie” world. Hilts shares this status along with other characters Rick plays onscreen, such as Bounty Law’s Jake Cahill and The FBI’s Michael Murtaugh. After all, movie magic enables Cliff Booth to stand-in for Rick for scenes involving physical action. That two actors can play the same character within the same scene suggests that fictional personae in cinema have a unique ontological status quite different from the real world.

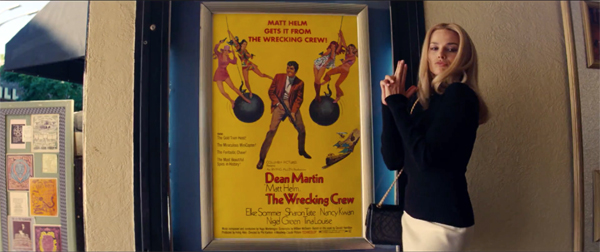

Arguably, the scene where Sharon Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew raises even more vexing issues about what is real and what is fictional. Unlike the clip from The Great Escape, the theatre screening shows the real Sharon Tate playing the character Freya in The Wrecking Crew. The fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate, along with the rest of the Bruin Theater’s audience. Yet, because Margot Robbie only pretends to be Sharon Tate for Tarantino’s camera, she doesn’t really watch herself playing the role. Obviously, Robbie belongs only to the real world. Yet Sharon Tate, as both an actual person and a fictional character, inhabits both the real world and the “realer than real world.”

Here the film indulges the Bazinian conceit that cinema has indexical properties. While making The Wrecking Crew, the film camera captured an imprint of the real Sharon Tate that preserved her being beyond the reaches of time and even death. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this moment is both joyful and sad. The viewer imagines the thrill that Tate feels in watching herself on the big screen, basking in the glow of incipient stardom. Yet the delight we experience is colored by our knowledge of what happened to the Sharon Tate seen falling on Dean Martin’s camera case. Unlike Robbie’s character, that Tate is doomed to a grisly death at the hands of psychopaths.

By film’s end, however, we are forced to reevaluate where Sharon Tate fits into Tarantino’s universe. When Cliff and Rick thwart the attack of Tex Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, and Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, both Sharon Tates appear to move solely to the realm of the “realer than real.” Like the fictional Sharon Tate played by Robbie, the actress who appeared in The Wrecking Crew also lives on in a parallel universe created by the forking of time. And the fate of that character remains completely undetermined. Now fully a part of the “realer than real,” Tarantino’s Sharon Tate might eventually snort cocaine with movie producer Lee Donowitz or bum a Red Apple cigarette from Pulp Fiction’s Mia Wallace.

Once she joins the “realer than real,” almost any fate you could imagine for Sharon Tate seems possible. And it is that sense of the actress’ unlimited horizons that gives the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its resonance. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time films always situated viewers in the realm of myth. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, on the other hand, evokes the fairy tale.

Tarantino is known for his experimentation with narrative, and the simplicity of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s “what-if” scenario could seem like a retreat from the formal play seen in his earlier films. Yet I’d argue that Tarantino’s merging of fact and fiction is even more audacious in certain respects. It strikes me as an unconventional example of what David calls “multiple draft narratives,” like Krzystof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance or Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gives us a second draft of history, albeit one where the key decision point is saved almost until the end of the film. And unlike Blind Chance or Sliding Doors, Tarantino doesn’t need to tell us what the different outcomes are for each of these tales. The first draft of history is one we already know.

In fact, the notion of multiple drafts offers a useful lens for all three films in Tarantino’s “counterfactual” trilogy. (The other two are Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained.) In Groundhog Day, Source Code, and Edge of Tomorrow, each iteration of the basic situation shows the protagonist inching toward his goals. They gradually progress to the point where they are able to alter destiny, either theirs or the world’s or both.

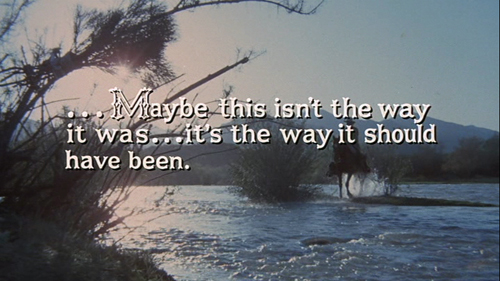

Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood all present images of history not as it was, but as it should have been. Such counterfactual histories run counter to the norms of speculative fictions that often present us with dystopian worlds we were lucky to avoid. (Think Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Robert Harris’ Fatherland, or Kevin Willmott’s “mockumentary” C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.) All of these stories depend upon our knowledge of the first draft of history. Yet Tarantino gives us second drafts that right particular historical wrongs in either small or large measure. In doing so, Tarantino gives us versions of history that are closer in spirit to his favorite movies. All three films in the “counterfactual” trilogy feature tidy resolutions. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, however, is even more self-conscious about the way Tarantino’s second draft of history takes the form of a “movie movie” climax. The realer-than-real version is the one we ought to prefer.

Paging Mr. Melcher, Mr. Terry Melcher…

If Tarantino’s conflation of fact and fiction evokes certain traits of the multiple-draft narrative, his vivid recreation of Hollywood circa 1969 illustrates another type of story popularized in American independent films and various art cinemas: the network narrative.

Tarantino has broached this form before in Inglourious Basterds. There he moves back and forth between three mostly independent storylines: 1) the Basterds’ guerrilla campaign against German soldiers, 2) Archie Hicox and Bridget von Hammersmarck’s initiation of Operation Kino, and 3) Shosanna’s plan to avenge her family’s deaths during the premiere of Nation’s Pride. SS officer Colonel Hans Landa threads through all three storylines. He orders the killing of Shosanna’s family in the opening scene. Later he shares apple streudel with Shosanna in a Paris café. Landa also investigates the scene where Hicox has been killed. In the climax, he interrogates Bridget in a scene that contains a grim allusion to Cinderella’s lost slipper.

Finally, Landa negotiates a deal with Aldo Raine’s superiors that guarantees his immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is obviously much less plot-driven than Inglourious Basterds. Yet, as noted above, it shares a similarity in the way it interweaves the stories of three characters: Rick, Cliff, and Sharon.

It’s frequently said that Hollywood is a company town. By situating all three characters within the film and television industries, Tarantino tacitly stays faithful to that truism. The protagonists’ shared profession also facilitates the kinds of attenuated links between stories commonly found in network narratives.

Part of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes in recognizing the “six degrees of separation” that join all of these people, both real and fictional, in the same entertainment ecosphere. Take, for instance, one decidedly minor character: actress and singer Connie Stevens, played by Dreama Walker. At the Playboy Mansion party, Stevens listens to Steve McQueen explain the romantic triangle that has Sharon living with her current husband, Roman Polanski, and her ex-boyfriend, Jay Sebring. Stevens, though, is the ex-wife of actor James Stacy, who played Johnny Madrid in Lancer. Stacy (played in our film by Timothy Olyphant) is Rick Dalton’s scene partner for the episode of Lancer that Dalton hopes can spur his comeback. Dalton is Sharon Tate’s neighbor on Cielo Drive, the same house that Charles Manson targets as the site of the “family’s” first murder. This circuit even loops back on itself. When Stacy and Dalton first meet on set, Stacy asks Rick whether it was true that he almost got a part in The Great Escape, the same part played by McQueen.

Two characters in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood serve as nodes that connect all three storylines together. The first is Cliff, Rick’s stunt man and gofer. Although not a resident at Cielo Drive, he spends a lot of time in Rick’s home and thus is privy to what happens in Sharon’s abode. This is especially evident when Cliff repairs Rick’s fallen TV antenna. The camera is aligned with him as he overhears Sharon playing a Paul Revere and the Raiders album. He also notices Charles Manson approaching the Polanski residence. Tarantino’s casting of Damon Herriman as Manson is likely an allusion to the television show, Justified. Herriman played Dewey Crowe alongside Olyphant.

Justified was also an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s “Raylan Givens” books. Tarantino has long admired Leonard’s work as a writer of both westerns and crime novels.

Employing a redundancy that befits Hollywood storytelling, Cliff gets linked to Sharon’s storyline in other ways. While working as Rick’s stunt man for an episode of The Green Hornet, he gets involved in a dust-up with Bruce Lee. Lee gave Sharon Tate some pointers on fighting as she prepared for her role in The Wrecking Crew. And in real life, the martial arts legend was recommended for the role of Kato on television’s The Green Hornet by Sebring, Tate’s former boyfriend.

Perhaps Cliff’s most important role in the film’s network involves his dalliance with Pussycat, one of the many young women who viewed Manson as a kind of guru. Cliff picks up Pussycat as a hitchhiker and gives her a ride back to the Spahn ranch. Having worked on the ranch back when it was an active production site, Cliff grows concerned for the safety of its owner, George Spahn. Cliff notices how the Manson clan has taken over and is troubled by its weird vibe. Determined to see George for himself, Cliff forces his way into George’s house over the objections of the Manson girls, especially Squeaky. George seems careworn, but Cliff finds that there is little he can do for him.

When Cliff sees a pocketknife sticking out of his front tire, he confronts Clem, one of Manson’s followers. The conflict becomes physical. Cliff breaks Clem’s nose with one punch and then proceeds to beat him to a bloody pulp.

This proves to be a dangling cause that gets resolved in the film’s climax when Cliff recognizes Tex, Sadie, and Katie as people he met at the Spahn ranch.

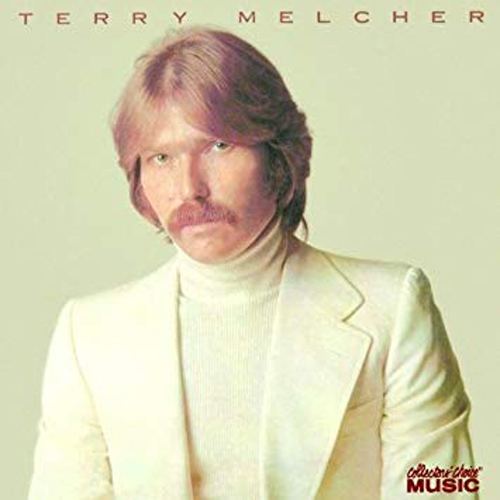

The other character who links the storylines together is one we never see: record producer Terry Melcher. Melcher is the “Terry” that Manson mentions when he visits Cielo Drive in the scene described above. Later, Tex reminds Sadie, Katie, and Linda that Charlie directed them to go to the place where Terry Melcher lived and kill everyone inside.

Although these are the only explicit references to Melcher, he is indirectly represented in several other aspects of the film. Here it helps to know a little about Melcher’s career and Manson lore. Even if Melcher’s name draws a blank, you likely know many of the bands he worked with: the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.

All these musicians crop up in one way or another in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Melcher’s last major credit of the 1960s was as producer of the Byrds’ Ballad of Easy Rider. When Rick berates Tex for parking his car on Cielo Drive, he yells, “Hey, Dennis Hopper! Move this fucking piece of shit!” Rick’s insult fits with his general disdain for hippies. But it also alludes to Easy Rider by comparing Tex’s look to that of Hopper’s character, Billy.

Two of the Mamas and the Papas – Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot – both appear in the party scene at the Playboy mansion.

We also hear the Mama and the Papas’ big hit, “California Dreaming” in a cover version by Puerto Rican singer José Feliciano. And when the car driven by Tex crawls up Cielo Drive, the music issuing from the Polanski residence is the Mamas and the Papas’ “12:30: Young Girls are Coming to the Canyon.” Even before Tex’s directive to the Manson girls, Tarantino has given us a subtle reminder that Melcher was Charlie’s intended, if indirect, target.

Finally, Sharon plays Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Good Thing” and “Hungry” on a hi-fi in her bedroom.

The choice of music is especially fitting since the band’s lead singer, Mark Lindsay, lived in the same house on Cielo Drive with Melcher and his then girlfriend, Candice Bergen.

Beyond these musical references, Melcher’s history with Manson informs Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in another way. Melcher recorded some demos of Manson’s songs, and even discussed making a documentary about Manson’s commune at the Spahn Ranch. In testimony at trial, Melcher said that any possibility of a record contract with Manson was sundered when Charlie asserted that he’d never join a musicians’ union. Manson’s staunch refusal was rooted in his desire to avoid entanglements with the establishment. Yet union membership was a condition for any contract with Melcher’s label, Columbia records. Another factor in Melcher’s decision was his assessment of Manson’s talent. Charlie couldn’t sing.

Although Melcher publicly stated that he only considered Manson’s musicianship, he privately expressed concerns about Charlie’s mental stability. These were heightened when he visited the Spahn Ranch and witnessed Manson in a physical altercation with a drunken stunt man. Tarantino more or less recreates this episode in his film, substituting Cliff for the unnamed stunt man and the hapless Clem for Charles Manson.

More importantly, Melcher is the son of screen legend Doris Day and stepson of agent/manager/producer Martin Melcher. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, he becomes the ideal, if absent, symbol of the combined worlds of music, television, and film that Tarantino so lovingly details.

How the West was lost

Los Angeles circa 1969 is presented as the epicenter of the American entertainment industries. It’s a place where a hairdresser like Jay Sebring rubs shoulders with action stars, TV cowboys, ingénues, film directors, and pop stars –and make $1000 a day to boot! The constant stream of hits from KHJ radio is as ubiquitous as the many movie posters, billboards, and theater marquees that feature Hollywood’s latest and greatest.

Tarantino’s press kit for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood makes reference to Joan Didion’s famous observation in “The White Album” that “the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community.” Most critics take Didion’s reference to the Sixties as shorthand for the end of the “peace and love generation.” Yet Tarantino’s slightly revisionist take suggests it’s not only the youthquake that died, but also a certain strain of Hollywood filmmaking that passed with it.

Although I don’t doubt their historical accuracy, the litany of titles that appear throughout Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels as curated as any of Tarantino’s music soundtracks. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, are films that entered the canon of great sixties cinema. Others, like The Night They Raided Minsky’s, are early films by directors who’d later achieve greatness. (In this case, William Friedkin, who won an Oscar in 1972 for The French Connection.)

But many, like Lady in Cement, Tora, Tora, Tora!, Krakatoa: East of Java, Mackenna’s Gold, C.C.& Company, and even The Wrecking Crew, are largely forgettable movies.

Tarantino clearly has affection for all of the drive-in theaters and Hollywood picture palaces where these titles played. But the titles themselves are evidence of the industry’s struggle to adapt to new tastes and a rapidly changing media landscape. Old-school show biz types, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, continued their success as singers and television personalities. But their careers as actors had functionally ended by 1969. And the efforts to keep them relevant often seemed either strikingly anachronistic or just plain weird.

In the opening scene of Lady in Cement, Frank Sinatra fights off a small school of sharks while he is examining the body of a nude woman who, like Luca Brazzi, sleeps with the fishes. And yes, the scene is as ludicrous as it sounds. If this is what became of Hollywood’s once great tradition, it is hard not to think we should just let it pass.

Yet, the fear of obsolescence also explains the oversize role that Tarantino gives to the Western as part of this changing landscape. True Grit and The Wild Bunch were among the summer of 1969’s biggest hits. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would eventually become the year’s top-grossing film. All three Westerns feature cowboy heroes that are either aging, outmoded, or both. They reminded contemporary viewers that horse riders would soon yield to horseless carriages, the lone bounty hunter would soon be supplanted by paramilitary detective agencies, and the humble six-shooter can’t match the lethal power of a Mexican army machine gun.

In retrospect, though, the popularity of the Western in 1969 represents the genre’s last gasp. Studios continued to make Westerns during the 1970s, but only three – Jeremiah Johnson, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and The Electric Horseman – would surpass $10 million in rentals in the entire decade.

On television, such long-running series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian had their last round-ups. The networks tried their hands at new Westerns, like Alias Smith and Jones (below), Hec Ramsey, Dirty Sally, and Lancer, but they were all short-lived. At the start of the 1980s, the genre was completely moribund. Subsequent efforts to recapture the Western’s former glory were mostly the equivalent of flogging a dead pony.

As a total cinephile, Tarantino is entirely aware of this aspect of the genre’s history. This is signaled quite explicitly in the decrepit condition of the Spahn Movie Ranch. Yet Tarantino also uses Rick’s career arc to signify its downward trajectory.

No character in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as strongly associated with the Western as Rick. His home is filled with collectibles like his Hopalong Cassidy coffee mugs. His walls are decorated with posters for The Golden Stallion and A Time for Killing. On set, he reads pulp oaters like Ride a Wild Bronc to relax between takes.

By using Rick to dramatize the twin declines of both Old Hollywood and its “bread and butter” genre, the narrative arc of Tarantino’s drugstore cowboy is one suffused with nostalgic melancholy. The key moment in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood occurs when Rick breaks down telling the story of Easy Breezy to Trudi Fraser, his Lancer co-star. He describes Easy “coming to terms with what it’s like to feel slightly more useless each day.”

The various threads of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s network finally knot together in the Manson family’s attack on Cielo Drive. At the moment of truth, it is telling that Rick reaches not for a firearm, but for the prop flamethrower he wielded in The 14 Fists of McCluskey. By recalling the moment when Rick shouts, “Anyone here order fried sauerkraut?”, Tarantino reminds us that violent spectacle and snappy quips will eventually replace the Western’s ritualistic showdowns.

Still, it is a musical allusion to the Western that gives Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its final grace note. Cliff and Rick have thwarted the Manson family’s attack. The ambulance takes Cliff to the hospital. Rick offers an explanation of what just happened to his neighbors. Jay recognizes Rick as television’s Jake Cahill. Via the intercom, Sharon invites him to come up for a drink. As Rick walks to the house, we hear the start of Maurice Jarre’s “Lily Langtry” [sic] from his score for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean.

John Huston’s film begins with an expository title shown below that highlights the western’s tendency toward self-mythology. It is especially apt for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s counterfactual history.

Jarre’s cue, though, appears in a scene where the renowned actress Lillie Langtry finally visits Judge Bean’s Texas town. Langtry is given a tour of the Bean’s house, now converted into a museum that also acts as a shrine to her. Bean worshipped Langtry, but tragically dies before he gets to meet her. Tarantino inverts both Huston’s sad ending and its dramatization of missed opportunity. By altering the course of history, the cowboy in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gets to be the real-life hero rather than the TV heavy. Rick also gets to meet the actress he’s admired from afar. Rick and Sharon are still both married to other people. But their chance meeting in the film’s epilogue feels more than anything like a dream fulfilled.

A star is unborn

In the previous section, I dwelt on the role of the Western in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood because of its symbolic significance in capturing a particular historical moment. But Tarantino borrows quite freely from another narrative prototype: the show-biz tale. In fact, while walking out of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I wondered aloud if it was Tarantino’s twisted take on A Star is Born.

Like A Star is Born, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood centers on a male performer whose career has started to decline and a female newcomer whose star is on the rise. Moreover, Rick’s drinking problems create an obstacle to his comeback in much the same way that alcohol contributes to the downfall of the male protagonists in all four versions of A Star is Born.

Tarantino, though, subtly alters this template in two ways. First, he depicts his two stars as neighbors rather than as a romantic couple. Secondly, he cleverly depicts Rick’s career arc as an inverse mirror of Sharon’s.

Tate was an Army brat who grew up in Europe. Her earliest work was as an extra in Italian films. She moved to Hollywood in 1962 and got her break playing Jethro Bodine’s girlfriend on The Beverly Hillbillies. In the mid-sixties, Tate made the move to films, appearing in Eye of the Devil and The Fearless Vampire Killers.

It was during production of the latter that Tate met her future husband, Roman Polanski. Tate’s role in Valley of the Dolls further enhanced her status as an “up and comer.” In 1968, Tate earned a Golden Globe nomination in the category of “Most Promising Newcomer — Female.”

In direct contrast, Rick’s career begins in Hollywood and ends in Italy. Rick enjoys early success with Bounty Law and The 14 Fists of McCluskey. But soon finds himself reduced to guest star roles on television. Against his better judgment, Rick agrees to star in four Italian quickies. Two of these are spaghetti westerns directed by Sergio Corbucci, a Tarantino fave who created the popular “Django” character. Rick returns to Hollywood but his future is uncertain. He could be the next Clint Eastwood, star of A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Or he could be the next Richard Harrison, star of $100,000 Dollars for Ringo and Secret Agent Fireball.

If this were all there was to the comparison, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But Tarantino hints at other parallels through a much more obscure and convoluted cinematic reference. An auteur as shrewd as Tarantino would undoubtedly remember that the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time” –used in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood under shots of Rick’s return from Rome – was previously featured in the opening sequence of Hal Ashby’s Coming Home.

The connection to Ashby’s film is strengthened by the casting of Bruce Dern as George Spahn, a role originally intended for Burt Reynolds. Early in his career Dern played Jane Fonda’s uptight, martinet husband in Coming Home. More importantly, during Coming Home’s climax, Dern’s character commits suicide by wading into the ocean to drown himself, just as James Mason does at the conclusion of George Cukor’s version of A Star is Born.

Which brings us back to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s controversial ending. Earlier I discussed the resemblance between its counterfactual history and multiple draft narratives. Here I want to discuss it as an illustration of the caprice of fame.

Much more than the endings of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, the climax of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels both resolved and unresolved. Hitler’s violent death in Inglourious Basterds surprised audiences who first saw it in theaters. Yet the historical record indicates that the Basterds simply saved Hitler the trouble of later killing himself and his wife, Eva Braun. At the conclusion of Django Unchained, the protagonist’s revolt clearly hasn’t ended slavery as a “peculiar institution.” But its story of personal revenge remains deeply satisfying.

The ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood left me with more questions than answers. I get it. Sharon Tate lives instead dying at the hands of the Manson family. Tarantino gives us the Hollywood happy ending that this story lacked in reality. But what’s next?

Do the deaths of Tex, Sadie, and Katie mean that Leno and Rosemary LaBianca also survive? Maybe. Perhaps the loss of three members of the cult might cause the others to reevaluate their loyalty to Manson. Perhaps Manson himself would reevaluate his plan to trigger a race war.

But maybe not. If Manson were the hero of Tarantino’s grindhouse climax rather than its villain, one could easily imagine the film running another twenty minutes with Manson vowing to get even. You might imagine it as something like the surprising “second climax” of Django Unchained. After mourning the loss of his compatriots, Charlie would proclaim. “The fires of Hell will descend upon the Hollywood hills. This time it’s personal.”

Perhaps the bigger question is whether Sharon continues to be the “It” girl during the next phase of her career. The allusions to A Star is Born suggest a steady upward trajectory. But the reality is that success depends upon a certain amount of luck. It is never assured. A few box office bombs and Sharon Tate might be reduced to the same sort of TV guest spots that Rick is doing.

In this way, the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood asks us to consider a potential paradox. Did Sharon Tate become more famous in death than she ever would have been in life?

The theme of talent tragically cut down in the prime of life is a hoary cliché of the celebrity biopic. Tarantino is smart to steer clear of it. Yet whenever we watch a film like Prefontaine, Beyond the Sea, or Lenny, one starts to wonder, “Would anyone bother to make this film if its subject had lived?”

To be sure, the totality of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood shuns any pat answer. Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas died at age 32. Initial reports said she choked on a ham sandwich in the midst of having a heart attack. I remember the media reports when Mama Cass passed in 1974. But does anyone who didn’t live through that moment?

James Stacy, star of Lancer, nearly died in a deadly motorcycle accident. (Tarantino hints at this fate by showing Stacy, sans helmet, riding his steel horse away from his trailer.) Stacy survived, but lost an arm and a leg as a result of his near fatal injuries. He eventually made a comeback in 1977 and even earned an Emmy nomination for his work on Cagney and Lacey.

Yet, if you mention James Stacy during dinner conversation tonight, I suspect your companion will ask, “Who?”

And then there is the scene where Pussycat and the other Manson girls walk past a large mural of James Dean in his iconic pose from Giant. Dean was certainly famous during his lifetime. But he became a legend at age 24 after his Porsche Spyder collided with another car, snapping his neck.

Would Sharon Tate have achieved stardom had she lived? God only knows. I certainly don’t. I do know one thing, though. Being a victim of the “crime of the century” preserved Tate’s image in popular memory with a vividness that very few human beings on this earth ever achieve.

Margot Robbie’s performance as Tate is extraordinary. She reminds modern viewers of the verve, spirit, and sensuality that Sharon brought to the screen. Yet it is the image of Tate as a tragically murdered heroine that Tarantino, like Mark Macpherson in Laura, appears to have fallen in love with. And it is this image that continues to haunt me some fifty years after Tate’s death.

Thank you to David and Kristin for their comments onf an earlier draft of this post. Thanks also to JJ Bersch and Maureen Rogers for letting me bounce some of ideas off them.

Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders remains the most comprehensive account of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Tom O’Neill, though, has spent the last 20 years investigating Manson’s crimes. His new book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the C.I.A., and the Secret History of the Sixties, claims that Bugliosi’s investigation was deeply flawed. Instead, his research suggests that Manson was a drug trafficker and C.I.A. operative. For O’Neill, the notion that Bugiliosi saved Los Angeles from a hippie death cult is wrong. The motive for the crimes was both simpler and more quotidian. All of Manson’s murders were the result of drug deals gone wrong. An interview with O’Neill can be found here.

The story that Terry Melcher witnessed a fight at the Span Movie Ranch between Charles Manson and a drunken stunt man sounds apocryphal. Yet it appeared in The Telegraph’s obituary for Melcher, which was first published in 2004. I haven’t been able to independently corroborate that story with another source. However, even if it isn’t true, it is part of Manson lore. I saw the same story repeated on at least three other websites. Doris Day’s death in May spawned the publication of a handful of articles about her relationship with Terry. They can be found here, here, and here. An brief overview of Melcher’s career as a record producer can be found in Rolling Stone’s obituary.

For those interested in learning more about Sharon Tate’s life, I recommend Sharon Tate: Recollection. It was written by Tate’s mother Debra. It also features a foreword by her husband, Roman Polanski.

Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood and Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls survey the momentous changes taking place in the film industry during the late 1960s.

Bruce Fretts provides a fairly thorough overview of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s voluminous pop culture references.

Several articles have also appeared that address different aspects of the film’s production. An interview with choreographer can be found here. Cinematographer Robert Richardson and production designer Barbara Ling detail their efforts to recreate the sets of the TV show Lancer here. Richardson also discussed Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s visual influences in a Hollywood Reporter podcast.

An interview with Mary Ramos, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music coordinator, can be found here. Guides to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music soundtrack can be found here, here, and here.

An analysis of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office implications is found here.

Finally, the release of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood has occasioned a number of think pieces that address aspect of the film’s counterfactual history and its identity politics. Here philosopher David Bentley Hart discusses the moral implications embedded in Tarantino’s counterfactual trilogy.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s gender politics is addressed here. The author, Aisha Harris, compares Tarantino’s depiction of Sharon Tate to other female characters in his filmography. Finally, zeitgeist readings of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in relation to the current political landscape can be found here and here.

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Could Hollywood possibly be in a box-office slump? Yet again?

Kristin here:

Speculative articles are presumably a lot cheaper for a news publication to run than are those pieces that involve travel, time-consuming research, and tracking down experts to weigh in on important events. The reporter need just sit at a computer, look at whatever evidence is at hand or a phone-call away, and opine on what one might expect to happen in the future. In part, of course, the opinion will be based on what happened in the past. The question is, what sort of information from the past would be most helpful in speculating with some likelihood of being right.

Not that it matters too much, since it’s pretty rare that months after events happen anyone goes back and checks on predictions made about them. That goes for prognosticators of award winners and of future hits and flops.

What might happen?

Facebook profile image for The Numbers research service

In this era of shrinking news media and burgeoning everything-else media, speculation has run rampant. It sustains the 24-hour news channels between breaking stories and a lot of print publications as well. Politics can generation all sorts of guesses and opinions, especially now, since there are so many players who can’t be expected to behave rationally. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter (both of which have advertising-supporting online versions) were once full of useful, hard-news articles that we film historians could snip and file away for, oh, say, cyclical revisions of a film-history textbook. Now David and I still subscribe to both and consider ourselves lucky if an issue has one or two truly informative pieces.

Not that these venerable publications are overwhelmingly full of speculative pieces. There’s the gossip, the real-estate section, the fashion section, the ten or twenty-five or one hundred most-powerful [fill in the blank] in show business, and so on.

But speculation seems to dominate in trade journals devoted to entertainment and film. There are obviously the predictions for Oscars and Emmys and other awards, which have become a year-round occupation. (The Oscars were given out in February, and almost ever since we’ve been getting lists of possible nominees for 2019, many for films not coming out for months.) Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and other trades indulge in awards-prediction coverage far more extensively than they used to, since it presumably extends the period during which film studios and distributors take out expensive “For your consideration” ads.

Box-office trends are often interesting and even useful to read after the fact, in the year-end analyses. They are, however, pretty vapid when presented piecemeal, month by month. There are a great many clichés that writers trying to fill page-inches with speculation can treat as if they are news. One particularly persistent and illogical one is that the industry must be in a slump when total grosses go down after a record-breaking year. We’re now at that stage in 2019 when enough films have come out to allow comparison with last year’s figures by this date.

Pamela McClintock recently wrote such an article for The Hollywood Reporter: “Will Red-Hot Avengers Blaze the Path to a Sizzling Summer?” in the April 30 print edition, and, with the strange habit that these trade papers have of changing articles’ titles for the online version, “‘Avengers: Endgame’ Will Need More Help to Save Summer Box Office”. Just after Avengers: Endgame opened, McClintock wrote that

North American revenue is still down 13.3 percent year-over-year during the January-to-April corridor, throwing cold water on predictions that 2019 could eclipse the best-ever $11.9 billion of 2018. (Before Disney’s Endgame unfurled April 26, revenue year-to-date was running nearly 17 percent behind last year, its lowest clip in at least six years.)

Nonetheless, analysts remain cautiously optimistic that Hollywood can at least match, if not best, 2018’s mark by Dec. 31, with predictions for the global haul settling a new benchmark of north of $41 billion.

These predictions are based on optimism about the plethora of upcoming sequel items and reboots: Aladdin, The Lion King, Toy Story 4, The Secret Life of Pets 2, Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, Spider-Man, and Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Let me point out three things.

First, in virtually all cases of year-to-year comparison are based on dollars unadjusted for inflation. Inflation is different in different countries, so trying to achieve a total global figure for any given year would involve a separate calculation for every country where movies are shown—which is close to, if not totally, impossible to do. Adjusted figures are helpful for some purposes, especially for comparing domestic grosses within the USA. For example, virtually everyone was claiming that the three Hobbit films outgrossed the original three Lord of the Rings films. In adjusted dollars, though, LotR is still the champ.

Here’s a helpful hint. Box Office Mojo has an inflation adjuster in its upper-right corner. If someone were to want to compare the domestic gross of Avengers: Endgame to that of some older film, say, Avatar, it would be informative to use the figure shown below instead of, or at least alongside, its gross in 2009 dollars: $749,766,139. (All figures in this entry stated to be in adjusted dollars were done using this feature, and all charts are from BoxOffice Mojo as well.)

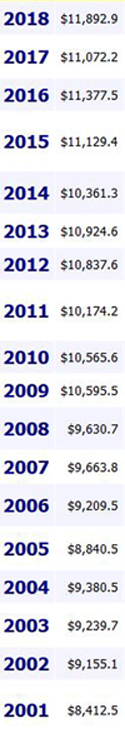

Seeing film grosses go up year after year can give the impression that the industry can go on expanding its earnings forever. Even after a record year like 2002 or 2009 or 2018, pundits seem to assume a slump if the following year sees lower box-office results. But every year can’t be a record year (except in movie executives’ dreams). The list at the left gives the total domestic gross of each year from 2001 to 2018 in millions of unadjusted dollars. Part of the rise is due to inflation. Part of it comes from ticket prices  being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

Second, usually a very few high-grossing films determine when there are record years. Avatar was the big film of 2009–but it had some help. More on this below.

Third, those high-grossing films are usually released in the summer and in the Thanksgiving-Christmas seasons. True, that cycle is breaking down in the current attempts by studios to avoid releasing the biggest films opposite or even near each other. Black Panther, the top grossing film of 2018, came out in February 16. The studio probably didn’t expect it to do as well as it did, but the very fact that a traditionally “summer”-type film came out that early and topped the charts will just reinforce the industry decision-makers’ believe that there can be big hits at any time of year.

The point, though, is that if really big films come out late in the year, their grosses earned after the New Year are counted for the following year’s total. So for example, Avatar came out on December 18, 2009, and well over half of its domestic earnings came in 2010: $466,141,929 out of the $749,766,139 total. As the list shows, total domestic earnings across the industry jumped by close to a billion dollars between 2008 and 2009, but there was almost no decline in 2010, partly because all but the first two weeks of Avatar’s run came then and partly because Toy Story 3 came out. As for 2009, it may have been the year of (two weeks of) Avatar, but it was also the year of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, and The Twilight Saga: Full Moon.

Thus in talking about record BO years and why they happened, it helps to look at when the top earners of the previous year were released.

Take another example, 2002, which for years was considered the target to shoot for when it came to setting new records for grosses. That was the first year that the domestic gross was over $8 billion, and 2001 had been the first year over $7 billion.

The year 2002 was cited as the benchmark for the industry because it had four really major films come out–a relatively rare event, or at least it was then. Three of them were from some of the top franchises of all time, and one established what is now the top franchise of all time: Spider-Man, Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

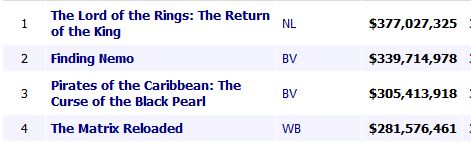

The last two titles were released on December 19 and November 15, so they helped make the 2003 total even slightly higher than the 2002 one—helped out by the top four of that year: The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Finding Nemo (is Pixar itself a franchise?), Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, and The Matrix Reloaded.

In fact, no year between 2002 and 2009 went below the 2002 gross except 2005. In 2003, three films had grossed over $300 million domestically (below right), while in 2005 only one, Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Beyond that, however, was the fact that there was relatively little continuing box-office income being generated by 2004 films in early 2005. The top three films had all been released early in 2004: Shrek (May 19), Spider-Man 2 (June 30), and The Passion of the Christ (Feb 25). The number four film, Meet the Fockers (Dec 22), contributed a healthy $103,501,600 to the 2005 grosses, but number five, The Incredibles (Nov 5) was largely played out by the end of 2004 and gave only $8,760,254 to the 2005 total.

Consider the calendar

I’m not going to say whether 2019’s gross domestic box office will surpass that of 2018, because it doesn’t matter that much. Annual figures fluctuate but have been remarkably steady over the years (adjusting for inflation). The industry will make a lot of money as a whole, and Disney will do extremely well. There will be the occasional modestly budgeted film that becomes a hit. Every year has its A Quiet Place or Crazy Rich Asians, numbers 16 and 17 among box-office leaders last year.

I can, however, point out some relevant contributing factors.

First, as in 2005, there’s an unusually small amount of money carried over from films released late last year and still playing early into 2019.

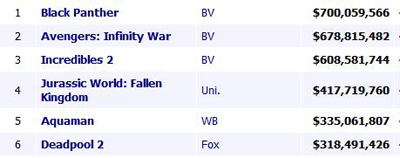

The top four films for 2018, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Incredibles 2, and Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom all came out in the summer or earlier. The fifth, Aquaman, is the exception,  released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

Given this rare disadvantage, can this year’s blockbusters make up the difference and match or top 2018’s total grosses? Let’s do what Box Office Mojo does: look at what the last film of the franchises made. Let’s do that in adjusted 2019 dollars.

I should note that now more big tentpole films are grossing a very large amount of the total box-office. The three top films that helped create last year’s record made over $600 million domestically: Black Panther at $700.1 million, Avengers: Infinity War at $678.8 million, and Incredibles 2 at $608.6 million. Compare this to the 2003 chart above, where the top earners were making in the $300+ million range. That shift can’t be wholly accounted for by inflation, which isn’t that high.

How many films this year can do that, or at least get over $500 million? Even as I post this, Avengers: Endgame is hovering on the brink of passing $800 million. How about Toy Story 4 (which deserves to, if only for its incredibly clever and funny trailers)? Toy Story 3 made, in 2019 dollars, $480.6 million. Beauty and the Beast made $511.8 million, and The Jungle Book $375.8 million. Disney has two of these remakes coming out this year, Aladdin and especially The Lion King. These three seem the likeliest possibilities.

Beyond that, The Secret Life of Pets made $389.0 in 2019 dollars. On the lower side, The Fate of the Furious made $227.5 and Godzilla $217.2.

The weirdest thing about the current speculation is that the prognosticators aren’t even talking about the entire year. Despite McClintock’s mention of total grosses for 2019 at least matching those of 2018 by December 31, the latest film that she mentions is Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbes & Shaw, due out August 2. But why are we worrying about a slump when it’s plausible that just the films released up to that point could by themselves bring the total at least close to last year’s? We’re witnessing a film that will make as much as two ordinary blockbusters and possibly become the top grosser of all time (in unadjusted dollars, at least). We’ve already seen one low-budget film become a hit. Us grossed $174,580,800–oddly enough, very close to the total for Crazy Rich Asians, which did the same last year. As I’ve suggested, we could anticipate at least two or three summer blockbusters grossing in the $500-600 million range.

But more importantly, there are, after all, films to come after August 2. Big films. Most notably, Frozen 2 on November 22. Frozen made $441.8 in adjusted dollars. There’s the untitled Jumanji sequel; the previous Jumanji entry made $404,515,480. (The BoxOffice Mojo adjuster isn’t adjusting 2017 or 2018 to 2019 dollars yet.) There’s Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The last Star Wars movie, Solo, was an exception to the saga’s fortunes, making only $213,767,512; so let’s take the previous one, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which made $620,181,382 domestically. Beyond these there is a bunch of somewhat more modest sequels (Terminator: Dark Fate, It Chapter Two), as well as some potentially big stand-alones (Cats, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Rocketman). I personally am rooting for Jojo Rabbit (below) to become an unexpected hit. We’ll see.

The lack of attention to films coming out late in the year does make some sense. Right now the industry is concerned to promote its summer films. That’s what marketing people want to talk about with trade-media journalists. November is a long way off. Plenty of time to start speculating about holiday box-office and the awards season come August.

All in all, taking the factors that I’ve laid out into account, it looks like a pretty safe year for Hollywood. I can’t quite help feeling that the hand-wringing over this putative slump just makes for a more dramatic story than one declaring that the 2019 box office is doing fine, thanks. Of course, it’s especially fine for Disney. The heads of other studios might be doing some justifiable hand-wringing.

Update, July 3, 2019: Now we’re into the summer season, and the pundits are still worried because this year hasn’t caught up with last year, where the high-grossing films came earlier in the year than usual. That said, I tried watching The Secret Life of Pets 2 on a transatlantic flight and was so bored I turned it off after about half an hour. That part of Rebecca Rubin and Brent Lang’s Variety article I can believe.

David has written an entry about a related ongoing trope in trade-journal coverage of the movie business. The box-office coverage during “slumps,” real or imagined, often gets linked to the “death of cinema” notion, which David discusses here.

Jojo Rabbit.

The classical Hollywood whatzis

Black Panther.

DB here:

In the academic world, there are conferences and conventions. Conventions tend to be humongous jamborees associated with professional groups like the Modern Language Association and the American Historical Association. They feature panels, workshops, plenary events, book displays, hundreds of papers, and meetings of subgroups–boards, caucuses, and the like. Also sexual liaisons, I’m told. If you want to feel like you belong to a corporation, go to a convention.

Conferences tend to be smaller and focused on single topics. Sometimes speakers are solicited through a call for papers, and sometimes the speakers are invited (the result might be called symposia). I think conferences are more exciting, liaisons aside. Some of the best experiences of my life have been get-togethers like “Imagination and the Adapted Mind: The Prehistory and Future of Poetry, Fiction, and Related Arts” (1999, University of California–Santa Barbara).

Last month, Kat Spring and Philippa Gates of Wilfred Laurier University added another to my list of favorite conferences. “Classical Hollywood Studies in the 21st Century,” which I announced in the run-up to it, was a wonderful gathering of scholars working on American studio cinema from a variety of angles.

Waterloo mon amour

Scott Higgins talks Minnelli.

We heard about production, distribution, marketing and publicity practices, censorship, and fandoms. Mark Glancy analyzed the trade-paper and fan-mag positioning of the Cary Grant/ Randolph Scott household (♥ + ♥?), while Will Scheibel studied discourse around the sad fate of Gene Tierney. Through both close analysis and probing of primary documents, several papers treated racial and gender representation: Charlene Regester on Double Indemnity, Philippa on portrayals of Chinatown, Barry Grant on race in science fiction, Ryan Jay Friedman on African American musical numbers. There was consideration of style and narrative as well, as in Chris Cagle’s case for distinguishing baroque and mannered styles within “1940s Hollywood formalism” and in Stefan Brandt’s tracing of thematic affinities between Finding Dory and The Grapes of Wrath.

I was glad to see the industry and its affiliated institutions get so much attention. Paul Monticone proposed a cultural approach to the MPPDA, while Tom Schatz traced industry developments in the New Hollywood and after. At the level of reception, Peter Decherney traced how digital tools can measure fan engagement with Star Wars. And John Belton, pioneer of detailed technological history, shared a Bazinian take on digital cinema.

Little-appreciated creative workers got to share the spotlight, in Helen Hanson’s paper on Lela Simone (music supervisor for the Freed unit) and Cristina Lane’s study of the career of Joan Harrison, Hitchcock’s “work wife.” Kay Kalinak revealed how composers swiped from themselves, as Tiomkin did in his score for The Big Sky. And there were lots of surprises, as with Shelley Stamp’s revelation of how film noir was sold to female audiences, Adrienne McLean’s account of stars’ running, or at least signing, advice columns, and Kirsten Moana Thompson’s dissection of the unique paint mixtures used in Disney animation.

It wasn’t musty, either. Things were light and friendly, with serious topics treated without pomp. Blair Davis’s obsessive search for science-fiction elements in serials and B films of the 1930s and 1940s, Steven Cohan’s zesty admiration for the “backstudio” picture, Kyle Edwards taking Torchy Blaine (and her budgets) straight, Dan Goldmark’s affectionate dissection of Pixar’s use of memory, and Liz Clarke’s enthusiasm for heroines of World War I films–all showed that classical filmmaking can be studied with both admiration and rigor. Not to mention Richard Maltby’s patented wry wit. (“David, you know I’ve always been a vulgar Marxist.”)

I have to signal my pride in witnessing how many of the participants were affiliated with our program. Tino Balio on MGM, Scott Higgins on Minnelli’s staging, Lisa Dombrowski on late Altman, Charlie Keil (with Denise McKenna) on Hollywood as a “social cluster,” Eric Hoyt (doyen of Lantern) on trade papers, Mary Huelsbeck on archival resources, Vince Bohlinger on US censorship of Soviet films, Maria Belodubrovskaya on Stalinist movie plots, Brad Schauer on Universal’s acting school, Kat Spring on how the trade papers conceived the musical, Patrick Keating on using the video-essay form to analyze lighting–all showed how you can pack a lot of ideas and information into 18 minutes. I was elated to see the learning and energy these several generations of Wisconsinites displayed.

The authors of The Classical Hollywood Cinema got in their licks. Janet Staiger talked about current screenwriting practices, highlighting the role of gatekeepers (agents, script analysts) and the need for vivid writing that can indulge in flourishes–“movies on the page.” Kristin drew on her Frodo Franchise project to show the problems, but also the advantages, of researching an event while it’s happening.

As for me, I got to give the keynote lecture. It was an intimidating situation, but it did allow me to make the case for analyzing films in relation to norms. Since the conference, I’ve thought more about the idea of Hollywood “classicism” and how we might analyze changes in it.

Not exactly classical, but sweet

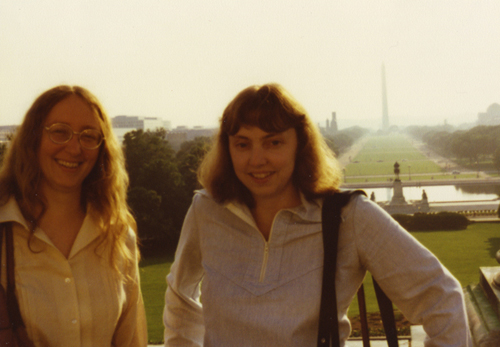

Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson, on a research trip to Washington DC 1979.

Now, some thirty-three years since we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we all know a lot more. There’s scarcely a paragraph of my chapters I wouldn’t change, and much of the research I and others have done since would correct, nuance, and deepen their claims. (I think Janet’s and Kristin’s contributions survive better than mine.)

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

The book received both praise and criticism. With the passage of time some issues have become clearer, and some critiques have, as far as I can tell, lost some force. For instance:

The term. Why call it “classical”? Humanists love to debate terminology. But we pointed out in the book that we inherited the term from French commentators, as far back as the 1920s, and from more recent academic circles. Nothing hangs on the name, actually. We could call it “standard” style or “mainstream” style or X style, and the descriptive claims we make about it will hold good. As I indicate in the book, the “classical” label suggests an effort toward coherent, unified storytelling–at least in comparison with the more episodic narratives we find in other traditions. (In Planet Hong Kong I reflect on more episodic approaches.)

The focus on production. Why not talk about distribution, exhibition, or reception? (A) It would require a much bigger book. (B) Production and its affiliated institutions are the most pertinent and proximate causal factors in shaping the films as we have them. (C) It’s not clear that conditions further along the chain have many consequences for the way the movies behave. (D) You can’t talk about everything. (E) All of the above.

The term, again. By calling Hollywood storytelling and style “classical,” don’t you ignore its ties to modern culture? This view, advanced most fully by Miriam Hansen, suggests that the causal factors we trace aren’t broad enough; we don’t consider the rise of urban culture and its associated patterns of behavior and experience. The modern city purportedly alters people’s perception and rhythms of life, and these shape the way films are made. Hollywood’s aesthetic is better conceived as “vernacular modernism.” I’ve responded to this line of argument in On the History of Film Style, where I argue that the position has an equivocal conception of urban experience and how perception works. Moreover, these critics haven’t shown how the cultural forces they invoke have shaped the narrative strategies and fine-grained stylistic features we analyze. The urban experience would have to have a sort of feedback effect on the filmmakers (given the proximity of production, as above). What’s the causal story to be told here? There’s also a problem of delayed timing: the modern city, choked with traffic and distracting displays, antedates the 1910s, when the Hollywood style crystallizes. On the whole, the modernity position seems to me to rely on analogies, not causation.

A rage for disorder. How unified are these films, really? Critics sometimes point to musicals, action movies, noirs, comedies, and other films that seem narratively disjointed. We argued that classical construction was a goal, not always achieved, but even genres that seemed to favor loose plotting put their films together fairly tightly. In addition, principles of both surface structure (dialogue hooks, continuity cutting) and plot structure (goal orientation, deadlines, appointments, etc.) bind the action in most feature-length pictures. In more recent years, analyses by Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and by me in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Reinventing Hollywood, along with some entries on this site, have, I think, convinced people just how carefully sculpted a classical film can be. Fights, chases, and escapes aren’t mere spectacle; they advance the story by creating new obstacles or revealing betrayals or killing off the hero’s best friend. I have, though, come to accept coincidence as being more important than screenwriting gurus have claimed. Yet even here, coincidence is absorbed into a pattern of cause-and-effect and motivation that isn’t willy-nilly. In short: Where you find planting and foreshadowing, you’ll find “classical” unity.

The neglect of auteurs. Why treat the output of hacks and mediocrities as on the same level as the work of the great filmmakers? Andrew Sarris promoted the idea of writing American film history as the accretion of the “personal visions” of directors. And historians of other arts routinely conceived of history as a succession of exemplary works produced by exceptional creators. But we were asking different questions. We sought to understand a tradition as a whole, and to explain its emergence and longevity. That’s an effort of value in its own right. Moreover, an auteurist could benefit from knowing relevant norms, because then one could pinpoint the distinctiveness of individual filmmakers. Throughout his work, Sarris occasionally signaled when a director made an uncommon choice of camera setup or cutting, and this gesture presupposes a norm in the background.

The schlock of the new. By stopping your survey in 1960, don’t you assume that a post-classical cinema came next–one less concerned with goal-directed plots and “invisible” style? We argued that the industrial conditions for the studios faltered around 1960, but the creative and labor practices (division of labor, hierarchy of control, etc.) continued into the present. We thought that classically constructed films dominated output afterward (Jaws, The Godfather, The Exorcist). Not that there aren’t changes. We suggested that many of the changes detectable in the more unusual “New Hollywood” films of the 197os are traceable to the influence of European art cinema; those principles of construction were blended with genres and stylistic patterns characteristic of the studio tradition. (Since then, other researchers have found this to be the case.) In addition, there are many post-1960 films which are “hyperclassical.” Back to the Future, Jerry Maguire, Die Hard, Hannah and Her Sisters, and others are “more classical than they have to be,” with intricate patterns of motifs and plotting–packed, we might say, with classical features. The same goes for many films we’ve discussed in our blog entries since 2006.

The monolith (no, not 2001). So the classical style never changes, is always in force, can’t go away? Ridiculously monolithic! Actually, we argued that classical filmmaking does change, but within boundaries. I invoked Leonard Meyer’s notion of “trended change,” in which

change takes place within a limiting set of preconditions, but the potential inherent in the established relationships may be realized in a number of different ways and the order of the realization may be variable. Change is successive and gradual, but not necessarily sequential; and its rate and extent are variable, depending more upon external circumstances than upon internal preconditions.

This seems to me to capture change in the studio tradition. Hollywood films can have 400 or 2000 shots, they can be told chronologically or not, they can have single protagonists or multiple protagonists, and there will be a lot of variety at any moment. But they will still tend to obey canons of classical staging, camerawork, cutting, sound work, and dramaturgy. And those changes are, as Meyer suggests, not generated from within the style, as a necessary unfolding like the growth of an organism. The variations are created by external circumstances such as budget constraints, production trends, influential models, new tools, fashion, competition among filmmakers, and the like. I’d make the analogy to the well-made play, which has survived as a model of plotting for nearly two centuries, but has allowed for a huge variety of manifestations, from Ibsen to Doubt and beyond. Perhaps perspective painting and Western tonal music, both robust traditions, would also exhibit trended change within history.

In the book, I tried to analyze levels of change by a three-tier model that still seems valid, though perhaps too abstract. Coming back from Waterloo, I began to see a way to specify a little more the kinds of change we can track, at least in terms of narrative construction. Maybe this effort will also help us understand why we think the “classical” system changes more than it does.

Black Panther in three dimensions

Narrative theorists often distinguish between “story” and “discourse.” There’s the causal-chronological string of events, and there’s the way they’re presented in the text we have. There are other terms for the distinction (story/plot, fabula/syuzhet), and they aren’t completely congruent. In an essay reprinted here I propose that we can better think of narratives as having three dimensions: the story world, the structure of the plot, and the narration.

Start with narration. Why? Because it’s the flow of information we encounter moment by moment, given to us through all the resources of the medium. Black Panther begins with a visual representation of how vibranium created the nation of Wakanda, while we hear on the soundtrack a father recounting the tale to his son. (Here the film’s narration is given as both pictorial and voice-over.)

In an earlier version of this entry, I said that it was T’Chaka speaking to T’Challa. But Fiona Pleasance wrote to point out that the voice is actually that of T’Chaka’s brother N’Jobu telling his son N’Jadaka, who will grow up to be Killmonger. They’re living in exile, which motivates the need to rehearse the nation’s origins.

The narration isn’t only giving exposition about Wakanda’s history. It’s establishing a hierarchy of knowledge, in which the father is presented as knowing more than his son. This is important for a later revelation of what aspects of the past are suppressed. And flashbacks and other narrational choices will further channel the flow of information. Soon after the prologue, we jump back to 1992, when T’Chaka learned of N’Jobu’s affiliation with arms dealer Klaue.