Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Women, Oscars, and power

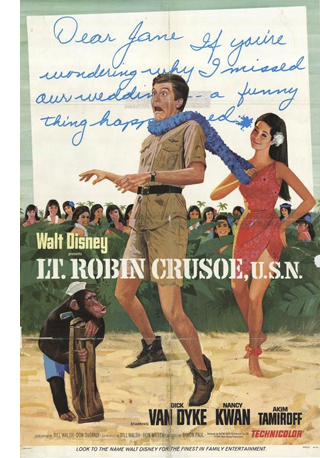

Kathleen Kennedy on the 1 January 2013 cover.

Kristin here:

Now that I have your attention …

We are now well into the season when award speculation begins. Well, actually Oscar speculation knows no season these days, but it snowballs between now and the announcement of the winners on March 4–at which point the speculation concerning the 2018 Oscar race revs up.

Among the issues that will inevitably come up is the question of whether more women directors will get nominated, especially following the critical and box-office success of Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman. It would be great to see more female nominees for Best Director, but the real problem is achieving more equity in the number of women being able to direct films at all. Unless more women direct more films, their odds of getting nominated will be low. Maybe the occasional Kathryn Bigelow will emerge, but overall the directors making theatrical features remain largely male.

Variety recently ran a story about initiatives to boost women’s chances in Hollywood. It stressed the low percentage of women in various key filmmaking roles:

The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University found that in 2014, women made up just 7% of the directors behind Hollywood’s top 250 films. Overall, of the 700 films the center studied in 2014, 85% had no female directors, 80% had no female writers, 33% had no female producers, 78% had no female editors and 92% had no female cinematographers.

Discouraging, except that there’s one figure that doesn’t support the lack of women. If 33% of films were without female producers, that means 67% had female producers–which is a lot better than in those other categories.

One thing that has struck me as odd is the lack of attention paid to the distinct rise in the number of female producers being up for Oscars in the recent past. This Variety article, however, is the first one I’ve seen offering numbers to show that women are doing a lot better in the producing field than in other major areas.

The missing names

Kathleen Kennedy, the lady illustrated at the top of this entry has produced seven films nominated as Best Picture, and she is considered one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. How could she not be? She produced Steven Spielberg’s films, alongside others, for many years and since October, 2012, she has been President of Lucasfilm in its incarnation as a subsidiary of Disney. She runs the Star Wars series.

In the Indie realm, producer Dede Gardner is on a roll, having since 2011 had three films nominated for the top prize in addition to wins in 2013 and 2016. Others, such as Megan Ellison and Tracey Seaward, have enjoyed multiple nominations. (I’m using the film’s year of release rather than the year when the award was bestowed.) As we’ll see, female producers are beginning to catch up to their male colleagues in number as well as prestige. Why no fuss about such important strides?

I think the main reason is that there’s no “Best Producer” category. If there were, I suspect our image of women in the industry would be very different. But there’s just a Best Picture one. In most cases neither the industry journals nor the infotainment coverage lists the producers alongside the titles of the Best Picture nominees. So who’s to know that the “Best Picture” race also is, faut de mieux, the “Best Producer” contest.

Another, perhaps less important reason why producers draw less attention is that because a film often has several producers. It’s more complicated to assign responsibility for who did what. Most people have a general idea of what directors do. They’re on set, they make decisions, and they supervise other artists. A female producer, like a male one, may have been included for many reasons. She might have done most of the work in assembling the main cast or crew members or she might have concentrated on gaining financial support. She might instead be termed a producer as a reward for crucial support at one juncture. We can’t know, and that perhaps makes it difficult for the public to get enthusiastic about producers. Of course, if journalists covered them more in the entertainment press, the public might gain more of a sense of what producers do.

Yet whatever their contribution, those producers played some sort of crucial role, and they are the ones who get up and receive the statuettes when that last climactic announcement of the evening is made. (Lately there has been a trend for the every member of the cast and crew and all their relatives present to rush onto the stage for a grand finale, but it’s the producers who give the thank-you speeches.) They can take those statuettes, with their names engraved on them, home and put them on their mantels or to their office to display in a glass case. Yet few have any name recognition outside the industry, the entertainment press, and a few academics.

Despite these producers’ importance, it’s difficult to find out who they have been over the years. Go to almost any website, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ own, in search of Oscar nominees stretching back through the years, and you will usually find names listed in all the other categories–but only the title of the nominated films in the Best Picture category. I finally found a complete list of Best Picture nominees’ producers compiled by an industrious contributor to Wikipedia. Going through and doing some counting and cross-checking, I have created and annotated my own list. With it I’ve tried to show the fairly steady progress that women have made in this category. I call them “nominees” below. Somewhat paradoxically, they win the Oscars, though technically the film is the official nominee.

To keep this list from becoming even longer, I’ve listed only nominated films which had one or more women among their group of producers. Up to 2008 there were five films each year. Starting in 2009 the number could be anywhere between five and ten, though it’s usually eight or nine. I give the number of nominated films starting in 2009. Assume any films not listed were produced by men. If you’re curious about who those men were, click on the link in the previous paragraph.

Here’s how things developed, including only years when female producers were “nominated.” (My comments in red.) Be patient. It gets off to a slow start, but things pick up.

And the nominees are …

1973 The Sting (WINNER) Tony Bill, Michael Phillips, and Julia Phillips.

Julia Phillips becomes the first female producer nominated since the Oscars began in 1927 and the first to win.

1982 E.T. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

The second female producer nominated.

1984 Places in the Heart. Arlene Donovon.

The third nominated female producer.

1987 Fatal Attraction. Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing.

The fourth nominated female producer.

1989 Driving Miss Daisy. (WINNER) Richard D. Zanuck and Lili Fini Zanuck.

Lili Fini Zanuck is the second female producer to win.

1991 The Prince of Tides. Barbra Streisand and Andrew S. Karsch.

1994 Forrest Gump. (WINNER) Wendy Finerman, Steve Tisch, and Steve Starkey.

The Shawshank Redemption. Niki Marvin.

Wendy Finerman (right) becomes the third woman producer to win a Best Picture Oscar.

This is the first year when two women are nominated. From this point to the present, there has been no year without at least one female producer nominated.

1995 Sense and Sensibility. Lindsay Doran.

1996 Shine. Jane Scott.

1997 As Good as It Gets. James L. Brooks, Bridget Johnson, and Kristi Zea.

The first year when four women are nominated.

The first time two women are nominated for the same film.

1998 Shakespeare in Love. (WINNER) David Parfitt, Donna Gigliotti, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Swick, and Marc Norman.

Elizabeth. Alison Owen, Eric Fellner, and Tim Bevan.

Life Is Beautiful. Elda Ferri and Gianluigi Brasch.

Gigliotti is the fourth woman to win a producing Oscar.

1999 The Sixth Sense. Frank Marshall, Kathleen Kennedy, and Barry Mendel.

First year when a woman producer, Kennedy, is nominated for a second time.

2000 Chocolat. David Brown, Kit Golden, and Leslie Holleran.

Erin Brockovich. Danny DeVito, Michael Shamberg, and Stacey Sher.

For the second time, two women are nominated for the same film.

2001 The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2002 The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. (WINNER) Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

Lost in Translation. Ross Katz and Sofia Coppola.

Mystic River. Robert Lorenz, Judie G. Hoyt, and Clint Eastwood.

Seabiscuit. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Gary Ross.

Walsh is the fifth woman to win in this category.

Walsh and Kennedy tie for the first woman nominated three times.

The second year when four women are nominated.

2004 Finding Neverland. Richard N. Gladstein and Nellie Bellflower.

2005 Crash. (WINNER) Paul Haggis and Cathy Schulman.

Brokeback Mountain. Diana Ossance and James Schamus.

Capote. Caroline Baron, William Vince, and Michael Ohoven.

Munich. Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Michael Mendel.

Cathy Schulman is the sixth woman to win.

The third time four women are nominated.

Kennedy becomes the first woman nominated four times.

2006 The Queen. Andy Harris, Christine Langan, and Tracey Seaward.

2007 Michael Clayton. Jennifer Fox and Sydney Pollack.

Juno. Lianne Halfon, Mason Novack, and Russell Smith.

There Will Be Blood. Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Lopi, and JoAnne Sellar.

The first year in which five women are nominated in this category.

2008 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Céan Chaffin.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

First time a woman, Kennedy, reaches a fifth nomination.

The third time two women are nominated for the same film.

2009 The first year of up to ten nominations. Ten films nominated.

The Hurt Locker. (WINNER) Kathryn Bigelow, Mark Boal, Nicholas Chartier, and Greg Shapiro.

District 9. Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham.

An Education. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

Precious. Lee Daniels, Sarah Siegel-Magness, and Gary Magness.

Kathryn Bigelow becomes the seventh woman to win in this category. (Right, with her producing and directing Oscars.)

The fourth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2010 Ten films nominated.

Inception. Christopher Noland and Emma Thomas.

The Kids Are All Right. Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, and Celine Rattray.

The Social Network. Pana Brunetti, Céan Chaffin, Michael De Luca, and Scott Rudin.

Toy Story 3. Darla K. Anderson.

Winter’s Bone. Alex Madigan and Ann Rossellini.

The second year five women are nominated in this category.

2011 Nine films nominated.

Midnight in Paris. Letty Aronson and Stephen Tenebaum.

Moneyball. Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, and Brad Pitt.

The Tree of Life. Sarah Green, Bill Pohlad, Dede Gardner, and Grant Hill.

War Horse. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Kennedy receives her sixth nomination.

The third year in which five women are nominated in this category.

The fifth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2012 Nine films nominated.

Amour. Margaret Mengoz, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz.

Django Unchained. Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin, and Pilar Savone.

Les Misérables. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Debra Hayward, and Cameron Mackintosh.

Lincoln. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Silver Linings Playbook. Donna Gigliotti, Bruce Cohen, and Jonathan Gordon.

Zero Dark Thirty. Mark Boal, Kathryn Bigelow, and Megan Ellison.

Eight female producers nominated, besting the previous record by three.

The first year in which each of two nominated films has two female producers.

Kennedy receives her seventh nomination.

2013 Nine films nominated.

12 Years a Slave. (WINNER) Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Klein, Steve McQueen, and Anthony Katugas.

American Hustle. Charles Roven, Richard Suckle, Megan Ellison, and Jonathan Gordan.

Dallas Buyers Club. Robbie Brennert and Rachel Winter.

Her. Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, and Vincent Landay.

Philomena. Gabrielle Tana, Steve Coogan, and Tracey Seaward.

The Wolf of Wall Street. Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joey McFarland, and Emma Tillinger Koskoff.

Dede Gardner becomes the eighth woman to win an Oscar in this category.

Megan Ellison becomes the first woman nominated for two films in the same year.

2014 Eight films nominated.

Boyhood. Richard Linklater and Cathleen Sutherland.

The Imitation Game. Nora Grossman, Ido Wostrowskya, and Teddy Scharzman.

Selma. Christian Colson, Oprah Winfrey, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

The Theory of Everything. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, and Anthony McCarten.

Whiplash. Jason Blum, Helen Estabrook, and David Lancaster.

2015 Eight films nominated.

Spotlight. (WINNER) Blye Pagon Faust, Steve Golin, Nicole Roaklin, and Michael Sugar.

The Big Short. Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, and Brad Pitt.

Bridge of Spies. Steven Spielberg, Marc Platt, and Kristie Macosko Krieger.

Brooklyn. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

The Revenant. Arnon Milchan, Steve Golin, Alejandro G. Iñárittu, Mary Parent, and Keith Redmon.

Blye Pagon Faust and Nicole Roaklin become the ninth and tenth winners.

For the first time two women win for the same film.

For the second time, two nominated films have two female producers.

2016 Eight films nominated.

Moonlight. (WINNER) Adela Romanski, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

Hell or High Water. Carla Haaken and Julie Yorn.

Hidden Figures. Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenro Topping, Pharrell Williams, and Theodore Melfi.

Lion. Emile Sherman, Iain Canning, and Angie Fielder.

Manchester by the Sea. Matt Damon, Kimberly Steward, Chris Moore, Lauren Beck, and Kevin J. Walsh.

Adela Romanski and Dede Gardner become the eleventh and twelfth winners.

For the second time, two women win for the same film.

For the second time, eight women are nominated, which so far remains the record.

Why should these names be hidden?

So we have overall 88 nominations for women, with twelve women winning Oscars for producing films. That compares with four nominations and one win for female directors. Women have not come all that close to parity with men in the producing category, but compared to the directors category, which people seem to take as a bellwether for the status of professional women in Hollywood, it’s spectacular. Moreover, we can see a fairly steady growth over the past twenty-three years, to the point where seven or eight producing nominations a year routinely go to women.

Of course, Oscars are not the only or the most objective way of measuring women’s power in Hollywood. One could try a similar examination of the number of women producing Hollywood’s top box-office films over the years. I assume there would be a similar growth in numbers, but the measurement would probably be a little more nuanced. That would be a much bigger project than would fit in a blog entry–even entries as long as the ones we occasionally favor our readers with. The San Diego State University study I mentioned earlier took an approach of this sort, and I’m sure there is deeper digging to be done among the statistics revealed by such research..

Given the way the Oscars have captured the public’s and the industry’s imaginations, however, the growing number of female producers being honored is a good way to point out that things may be better than they seem when one focuses narrowly on the directors category.

After all, the prescription for putting more women in the director’s chair and behind the camera and so forth is always that more female producers and writers are needed, making films for women and by women. This seems reasonable, and yet the question remains, if women are doing so well, relatively speaking, in rising to the top as producers, why, over the twenty-three years since 1994 haven’t they hired more women at every level for their film crews? (Of course, some of them have acted as producer-directors on their own projects.) Why hasn’t Kennedy, who has been firing and hiring male directors for Star Wars projects lately, ever given a female director a shot at it? Maybe she will at some point, as the evidence grows that women can create hits.

Perhaps most women producers are constrained by their fellow producers on projects, who are often men. They may feel pressured to reassure studio stockholders and financiers by sticking with the tried and true. And yet there do finally seem to be signs that studios are looking beyond the obvious pool of talent. Patty Jenkins, an indie filmmaker, directs Wonder Woman to unexpected success. Taika Waititi, a Maori-Jewish indie filmmaker from New Zealand, suddenly finds himself directing Thor: Ragnarok, which shows every sign of becoming a hit. With luck, the effect of the rise of female producers, as well as of more broadminded male ones, will finally have a significant impact on both gender and ethnic diversity in Hollywood filmmaking.

In closing, I would suggest to the press that it would be helpful for them in writing their endless awards coverage to list more than just the titles of the Best Picture nominees. Add the names of their producers, who are in effect nominated for Oscars. Treat them more like stars, the way you do with directors. I realize that there are often lingering disputes over which of the many producers attached to some films are actually the ones eligible to accept Oscars for them. But once such disputes are resolved, these “nominees” should be listed, and certainly after the awards are given out, they should be part of the historical record of Oscar nominees and winners. This would help both the public and the industry to get the big picture, not just the Best Picture.

[Oct. 24, 2017: My thanks to Peter Nellhaus for pointing out Julia Phillips’ win for The Sting in 1973. I have corrected the text accordingly.]

The Shawkshank Redemption (1994).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past

Cover Girl (1944).

DB here:

I just got my first copy of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I’m always scared to look at a published piece because I expect my eye to light on (a) a misprint; or (b) a sentence of unusual clumsiness or simplemindedness. Other writers have told me they have similar qualms. But I did look, and on this fat volume: so far, so good. It even has black, slightly corrugated endpapers, like the paper inside a box of chocolates.

This was a personal project for me, for reasons I’ve sketched elsewhere on this site. I grew up watching 1940s films on TV and have always had a fondness for what James Naremore has called “the beating heart of Hollywood.” In my teen years, watching Welles and Hitchcock movies along with B films and minor musicals fed my interest in studio cinema.

When I started teaching in the 1970s, I was keen to catch up with all those nifty movies sitting comfortably in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. My classes screened His Girl Friday (in a pirate copy) and Meet Me in St. Louis and Possessed and The Locket and White Heat and The Ministry of Fear and many more. Students working with me studied Gothics, war films, and I Remember Mama. It was then I started to realize just how creative this period was.

One piece of boilerplate for the book puts it more melodramatically.

In the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Viewers were plunged into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists. Others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes were lurching into violent confrontations.

Films were exploring parallel universes and supernatural dimensions. Characters switched bodies or intuited the future. Combining many of these ingredients, there emerged a new genre—the psychological thriller, populated by murderous spouses and witnesses who became targets of violence.

If this sounds like our cinema of today, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, David Bordwell examines for the first time the range and depth of the 1940s trends. Those trends crystallized into traditions. The Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the 1940s.

Bordwell shows that the booming movie market at the start of the Forties allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. He traces how Orson Welles, Preston Sturges, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and dozens of lesser-known creators built models of intricate plotting and psychological complexity.

Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun in the late 1930s, in radio, fiction, and theatre before migrating to cinema. And even with the late 1940s recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation could not be stopped. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, when filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analysis of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, Bordwell analyzes the era’s unique ambitious and its legacy for future filmmakers.

Today I’d like to give you some background on the book and flag a new page on this site you might find of interest. (If you can’t wait, you have permission to go there now.)

Questions, questions

Kitty Foyle (1940).

Reinventing Hollywood turned my enthusiasm for the 1940s into a set of questions.

The enthusiasm was based on a hunch that Hollywood cinema between 1939 and 1952 saw a burst of innovative storytelling. The innovations weren’t utterly new, but they differed from what was seen in the 1930s by virtue of their range, number, and complexity. The more I looked, the more I realized that the Forties recaptured the narrative range and fluidity of silent cinema, extending and nuancing it with sound. In essence, a new set of norms emerged, forged by many filmmakers.

Several questions followed. How to describe those innovations? How to chart their range and variations? How to analyze their effects—on the sort of stories told, on how viewers understood them? How did the innovations alter genres, or create new ones? How might we explain the rise and expansion of these new norms? And finally, what sort of legacy did this process of changing conventions leave to the filmmakers that followed? In all, how did various trends coalesce into a tradition?

This plan, ridiculously ambitious, at least has the virtue of originality. Most books about the 1940s concentrate on major figures—stars, producers, directors, the Hollywood Ten. Other books explain how studios or censorship or labor disputes worked. Others focus on genres such as the musical or the melodrama or the combat film. A popular option is devoted to that not-quite-a-genre film noir. These are all worthy subjects. And there’s no shortage of books seeing 40s film as a reflection of wartime or postwar America, or the geopolitics of the Cold War.

Studying narrative norms cuts across many of these common perspectives. Individuals matter, particularly ambitious screenwriters, producers, and directors striving to tell stories in unusual ways. But institutions matter too, as studio culture and writers’ associations prized a degree of originality in plotting or point of view. And narrative devices cut across genres to a considerable degree. Although flashbacks have come to be associated with film noir, they actually appear in all genres, and take on different roles accordingly.

So, 621 films later, my project has become an effort to contribute to a history of film form—the various storytelling methods that filmmakers have developed in different times and places. (In other words, a poetics of cinema.) In effect, I’m asking that the kind of appreciation people show for genres, actors, and auteurs be stretched to narrative strategies as well.

Darryl F. Zanuck, with his shrewd narrative instinct, gave me my epigraph.

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

The book in between

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

The project blended in with earlier work I’d done, particularly in The Classical Hollywood Cinema and The Way Hollywood Tells It. In a sense, Reinventing Hollywood is a bridge between those two books.

CHC, written with Kristin and Janet Staiger, traced continuity and change in the studio storytelling tradition from its inception to 1960. It analyzed how conventions of story, style, and work practices were established and maintained over the decades. The Way Hollywood Tells It suggested that after 1960, the broad conventions remained in place but were modified in particular ways.

In passing, I suggested that innovations of “contemporary Hollywood” owed a lot to experiments launched in the 1940s. The new book tries to pay off that IOU. Reinventing Hollywood asks how, within the broad conventions of classical Hollywood, particular innovations could emerge in the boom-and-bust 1940s. Many standard devices of our films today, from voice-over and fragmentary flashbacks to block construction and tricks with point of view, can be traced back to the Forties, when they were consolidated and refined.

The two earlier books also considered film technique—staging, shooting, editing, and the like. Reinventing Hollywood doesn’t tackle visual style, for two reasons. It would have doubled the book’s length, and I’ve said my say on 40s style in other work. Style shapes story, of course, and I’ve tried to take this factor into account. But I concentrate on the principles of story world, plot construction, and narration—the three dimensions of narrative I’ve outlined elsewhere.

None of these books is auteurist in basic orientation, but they aren’t anti-auteurist either. Surveying techniques in a systematic way helps call attention to adepts, middling talents, and innovators. In Reinventing, I think the interludes on Mankiewicz, Sturges, Welles, and Hitchcock show how skillful filmmakers mobilized emerging conventions in powerful ways. In effect, we reconstruct a menu of options to sense the values in picking and mixing them. For example, Citizen Kane‘s investigation plot, adorned with a dying message and a bevy of flashbacks, was a vigorous synthesis of devices that were circulating through film and other media in the late 1930s. The boldness of the effort made it influential on what followed. We get a better sense of directors’ (and writers’ and producers’) idiosyncratic strengths when we know the norms they’re working with, and sometimes against.

Reinventing Hollywood, running nearly 600 pages, makes The Rhapsodes look scrawny. But it isn’t the behemoth that CHC is. CHC could give this book noogies.

The big and the small

The Bishop’s Wife (1947).

It was hard to discuss broad trends and still probe particular cases in detail. So the chapters move from generalities to specifics in steps. Some films are merely mentioned, others described briefly, others considered at greater length, and some analyzed in depth. After a conceptual introduction and a historical panorama of Hollywood as a creative community (Chapter 1), there are chapters on flashbacks, plot construction, woven versus chaptered plots, manipulation of viewpoint, voice-over, character subjectivity, psychoanalytic plots, realism and fantasy, mystery plots, and self-conscious artifice. The conclusion looks at the impact of the period on later filmmakers.

I try to go beyond obvious observations to study the mechanics of familiar devices. So I come up with terms and concepts to pick out finer-grained tactics: the breadcrumb trail that sets up many flashbacks, block construction, hooks, switcheroos, and the like.

The chapters on particular techniques are broken by “interludes” devoted to particular movies or moviemakers. Some of these interludes involve well-known films and figures, but others look at obscure items. (Yes, The Chase is involved.) Even the treatment of Big Names tries to offer something original, as when I argue that Hitchcock and Welles pushed 40s innovations very far and sustained them throughout their later careers.

Here’s the table of contents, with small annotations

Introduction: The Way Hollywood Told It

Chapter 1: The Frenzy of Five Fat Years (Hollywood as an ecosystem)

Interlude: Spring 1940: Lessons from Our Town

Chapter 2: Time and Time Again (flashbacks)

Interlude: Kitty and Lydia, Julia and Nancy

Chapter 3: Plots: The Menu (conventions of plot structure)

Interlude: Schema and Revision, between Rounds

Chapter 4: Slices, Strands, and Chunks (alternative structural options)

Interlude: Mankiewicz: Modularity and Polyphony

Chapter 5: What They Didn’t Know Was (managing narrative information)

Interlude: Identity Thieves and Tangled Networks

Chapter 6: Voices out of the Dark (voice-over)

Interlude: Remaking Middlebrow Modernism

Chapter 7: Into the Depths (subjectivity)

Chapter 8: Call It Psychology (psychoanalytic films)

Interlude: Innovation by Misadventure

Chapter 9: From the Naked City to Bedford Falls (realism, fantasy, and in-between)

Chapter 10: I Love a Mystery (thrillers and mystery-based plotting)

Interlude: Sturges, or Showing the Puppet Strings

Chapter 11: Artifice in Excelsis (self-conscious display of conventions)

Interlude: Hitchcock and Welles: The Lessons of the Masters

Conclusion: The Way Hollywood Keeps Telling It (legacy of the 1940s)

To keep things specific, I’ve prepared eleven film clips keyed to particular analyses. Just playing the clips might give you a sense of the book’s range. They’re also fun in their own right.

No zeitgeists, please

Blues in the Night (1941).

Two last points. One bears on preferred explanations. How do we explain why cinematic innovation burst out at this particular time? Again, the book tries to pursue an uncommon path.

Many writers look to a zeitgeist—the anxieties of war, the anxieties of postwar adjustment, the anxieties of the anti-Communist crusade, any anxiety you can imagine. Instead I try to look for institutional factors shaping the films’ norms. Centrally, there are the conditions of the film industry, with its rich interplay of personnel and story materials shuttling all over the place. There are also the cinematic traditions themselves, such as plots depending on amnesia. Particularly important are the adjacent arts, including theatre, radio, and popular fiction. All these sources get modified by a process of schema and revision—borrowing something already out there but warping it to new ends. In short, instead of looking for remote causes in the broader society, I try to locate more proximate ones within the filmmaking community and the turmoil of popular culture.

Someone might argue that this just pushes the problem back a step. Don’t social anxieties surface in all these media? To this I’d argue, as I did here and here, that those anxieties are very hard to identify. Not all anxieties or concerns will be shared by a populace (viz. our current political situation). And we can’t establish a strong causal connection between them and the products of popular media—especially since media are indeed mediated, by tastemakers, gatekeepers, and the institutions that produce popular culture.

For the period I’m concerned with, James Agee noted the role of mediators in his complaints aimed at the film-as-dream sociologists of the period:

It seems a grave mistake to take [movies] as evidence as definitive, as from-the-public, as if 40 million people had actually dreamed them. Take the far simpler case of advertising art. The American family, as shown therein, is not only not The Family; it isn’t even what the American people imagines as The family. It is A’s guess at that, subject to the guesswork of his boss, which is subject in turn to the guesswork of the client. At best, a queer, interesting, possible approximation, but certainly never definitive. In movies many more people take part in the guesswork, but not enough to represent a population: and many more accidents and irrelevant rules and laws deflect and distort the image.

A movie does not grow out of The People; it is imposed on the people— as careful as possible a guess as to what they want. Moreover, the relative popularity or failure of a picture, though it means something, does not at all necessarily mean it has made a dream come true. It means, usually, just that something has been successfully imposed.

Instead of social reflection, we should expect refraction. Decision-makers opportunistically grab memes and commonplaces (the unhappy housewife, the juvenile delinquent, the returning vet) in hopes they can make something appealing out of them. They absorb those into familiar (narrative) forms. We get, then, not a “vertical” or top-down flow of social anxieties into artworks, but a “horizontal” ecosystem, a dynamic of exchange and transformation. The creators copy one another, obeying local norms while also resetting boundaries. This process includes selective assimilation of ideas thrown up by the culture, and it gets amplified by network effects, as sticky ideas themselves get copied. In other words, ideology doesn’t turn on the camera. The final film is always mediated by humans working in institutions, and both the people and the institution have many agendas.

A second point follows. Working on this book brought home to me how much film owes to other media. In a way, Forties cinema became more “novelistic” because it sought to assimilate techniques of split viewpoints, replays, inner monologue, and subjective response characteristic not so much of modernism (those were old hat by the 1940s) but of popular fiction and what we might call “middlebrow modernism.” A Letter to Three Wives (1948) attaches itself in turn to three women, each with memories of the past, with that trio interrupted by a never-seen fourth woman mockingly narrating the tale. It’s a cinematic treatment of the shifting viewpoints and personified narrative voices to be found in the nineteenth-century novel (Dickens, Collins, James) and later in genre fiction, not least in mystery tales. (It’s also a modification of the source novel.)

But you could also argue, as André Bazin did, that the 1940s saw a new “theatricalization” of cinema, with self-conscious adaptations that stressed stage conventions like the single-setting action. And of course radio supplied important prototypes for acoustic texture and first-person voice-over. Each of these devices wasn’t simply ported over to film; moving images and recorded sound gave literary, theatrical, and radio-based techniques new expressive possibilities. And all depended on the churn of people working side by side to innovate within familiar norms.

Every author discovers or remembers too late those things that should have been mentioned. Doug Holm reminded me of the dream narrative of Sh! The Octopus (1937). Jim Naremore pointed out that Rex Stout had already done my work for me in Too Many Women (1947, year of my birth), when Archie reports, “It was a wonderful movie . . . Only two people in it have amnesia.” On a different pathway, I’d love to do more research on moguls’ screening rooms as a condition of influence. (They could borrow films from rival studios without charge.) Julien Duvivier is a minor hero of my book, but only after the book was submitted did I see his L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), a perfect extension of 1940s storytelling to a French milieu.

And just recently I found a nice confirmation of the unexpected byways of the ecosystem. According to the author, the figure of the “psycho-neurotic” returning soldier was at first mandated by government policy but then twisted by ambitious screenwriters into tales of civilian madmen. The article has the enviable title: “That Psycho Story Swing Is No Cycle; It’s Now an Obsession.” If you buy the book, please write that into the endnotes.

And for the third time, feel free to visit the clips page!

I owe a lot to several people who saw this book through publication. Foremost are my editor at the University of Chicago Press, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues Melinda Kennedy and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. Then too there is Bob Davis, who supplied the book’s jacket photograph; Kait Fyfe, who prepared the clips for posting; and web tsarina Meg Hamel who set up the clips page. My other debts are recorded in the acknowledgments, but of course I must mention Kristin who had the hardest job of all. She had to put up with the author.

My Agee quotation comes from “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for Museum of Modern Art Round Table (1949),” in James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017), 975. I’m indebted to Chuck for sharing this with me. Chuck’s discussion of Agee on our site is well worth a read.

Many entries on this site are dedicated to 1940s Hollywood. See the relevant category. “Murder Culture” has been revised as a chapter in the book. On 1940s visual style, see Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style, and entries under 1940s Hollywood. There’s also the web essay on William Cameron Menzies. My most detailed arguments against social reflection and zeitgeists in historical explanations comes in the title essay in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32.

Although the Amazon page offering Reinventing Hollywood says copies aren’t available until October, it seems that copies are shipping now from Chicago’s webpage. Amazon offers no discount on the title. (See P.S.) It’s currently available only in hardcover, with a paperback planned for the distant future.

P.S. 27 Sept 2017: Actually, Amazon is now discounting Reinventing Hollywood; it’s $30.77, as opposed to the $40 list price.

P.P.S. 13 October: Amazon’s prices on the thing have been fluctuating wildly. See this entry. Those wild and crazy algorithms!

Our Town (1940).

The end of Theatoriums, too

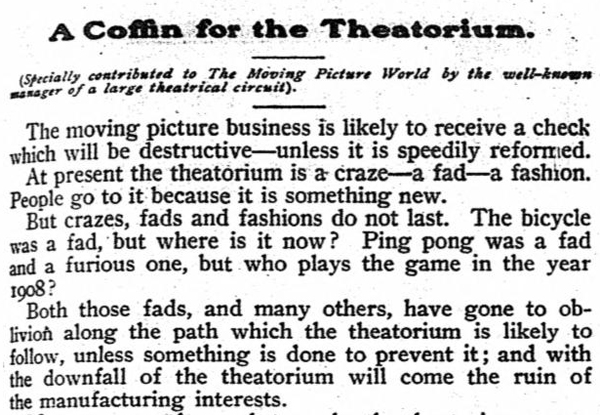

Moving Picture World (February 1908), 135.

DB here:

Vis-à-vis the last post, all of three hours ago, Alert Reader and arthouse impresario Martin McCaffery sends the above.

Actually, it’s much in the spirit of current jeremiads: Movies and their theatoriums better shape up, or they’ll be finished–like bicycles and Ping-Pong.

History is so cool. Full text here and below. There’s also a 1908 rebuttal, in the spirit of movies-are-doing-just-fine-thanks, here. Both courtesy the prodigious Lantern.

It’s all over, until the next time

Our Little Sister (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2015).

DB here:

The perennial Silly Season topic, The Death of Film, is back.

In June, Huffington Post‘s Matthew Jacobs announced “The death of Movies As We Know Them.” He laments the loss of “solid storytelling and bankable stars.” In August, Brian Raftery asked: “Could this be the year that movies stopped mattering?” The author argues that now movies are “Something to Do When the Wi-Fi’s Down.” Echoing the virality theme, Ty Burr announced that two albums, Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and Frank Ocean’s “Blonde,” “came packaged with better movies than anything in theatres.” For Burr, the summer season confirmed that audiences are more interested in grazing among YouTube clips and luxuriating in eight-hour video serials than watching a feature film. “The two-hour movie, especially in its larger and more commercial form, is becoming a relic.”

Richard Brody eloquently replied to Raftery, noting Beyoncé’s debt to Julie Dash and Khalik Allah’s films. Brody has been around this block before, as I noted in a 2012 blog entry.

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

But after four years, maybe things really have deteriorated. So let’s get specific. What’s really going down the tubes? The theatrical side of the industry? Quality? Cultural cachet?

Movies, your best entertainment value

Bar area of Orange Cinema Club, Beijing.

Let’s look at some current evidence about the industry, thanks to the redoubtable Cinema research division of IHS Media Technology.

The newest symptom of cinema’s demise, according to many, is the rise of Netflix and other streaming platforms. Serial TV is attracting a lot of attention, true, but streaming has long relied on licensing feature films from studios, independents, and overseas companies. TCM and Criterion are launching FilmStruck as a new channel chock-full of classic films from Hollywood and elsewhere. Amazon and Netflix have also begun acquiring and financing features to guarantee a supply of those two-hour films that for some reason people still want to watch.

But what about movies in theatres? Actually, things are pretty robust. Despite everybody viewing at home and on the go, for many years theatre growth has been phenomenal. In 2015 the world added about 12,000 screens, hitting a new high: 153,163. Not counting all our “second screens” (and third), there are more movie screens now than ever before.

By the way, those of us, me included, who worried that the rise of digital exhibition would cause a drop in screens were wrong. Digital was a shot in the arm to theatrical exhibition, and it made 3D a viable platform. That format shows signs of growth, chiefly because of China, and now 16-20% of box-office grosses come from 3D screenings.

In keeping with the expansion of exhibition, for the last decade, the global box office has risen steadily. Almost every year sets a record. The new height is $37.7 billion for 2015, and it seems likely that 2016 will beat that.

As for number of admissions, 2015 also set a record: 7.4 billion, a jump of 13% over 2014. This is a bit more than one ticket for every man, woman, and child on earth. The first half of 2016 is ahead of the same period last year.

Of course revenues don’t equal profits. Jacobs is especially concerned that some big films have been losing money in their domestic theatrical run. But most films lose money in that run. For a long time, ancillary markets (DVD, overseas cable, merchandising, etc.) made up for the deficits. More and more, overseas theatrical is helping in a big way. In a recent rundown, of the summer’s top twenty hits, a print story in The Hollywood Reporter indicates that foreign grosses outweigh US/Canadian ones in most cases, and sometimes by a lot.

For example, big as Captain America: Civil War was in the US, 65% of its $1.1 billion haul was due to the offshore market. X-Men: Apocalypse got half a billion theatrical, 71% of which came from the international audience. Ancillaries will still need to kick in, given the mammoth budgets of films like these, but those ancillaries piggyback on theatrical visibility. As ever, the big pictures pay for a lot of lesser films.

Moreover, so many costs are buried or dispersed in overhead, debt service, tax incentives, deferred payments, far-fetched studio expenses, and the like that it seems hard to know what final profits really are. Nor will we know what, if any, profits are yielded by films from countries with subsidized film industries.

There are many things to worry about in the exhibition business, but it doesn’t seem on the verge of collapse. Let’s keep a sense of proportion. Here is what the death of “our cinema” might really look like.

Theatre admissions fall 45% over six years. Studio profits fall 80% over the same period. One-sixth of theatres close. Major overseas markets refuse to remit the earnings of Hollywood films. Audiences turn increasingly to other leisure activities.

This was the state of the American film industry in 1953. The prosperous war years, culminating in the all-time admissions high of 1946, were over and the studios went into sharp decline. Thanks to the 1948 Supreme Court “Divorcement Decree,” the studios lost control of their theatres, relinquishing not only valuable showcases for their product but also millions of dollars of prime real estate.

Yet as we know, 1953 didn’t end cinema, not even American cinema. As the old studio system waned, a new one eventually replaced it. In the process, Hollywood continued to make major films. Filmmaking abroad—in Asia, Europe, and South America especially—flourished. Film festivals sprang up, and a new young public proved eager to watch movies from a variety of cultures. Avant-garde and documentary movements gained traction, partly because of the widespread dissemination of 16mm.

No one, so far as I can tell, predicted the end of cinema, or Hollywood, because of the 1947-1953 crisis. That person would have looked very foolish. Things today aren’t nearly so severe.

Long, hot summers

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

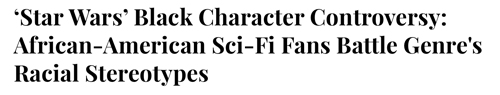

Things often seem grim at summer’s end. Let’s go back fifty years, to the summer of 1966. In those days, the blockbusters and prestige pictures were saved for fall and winter. Indeed, the blockbusters were largely the prestige pictures, the adaptations of novels and plays. The big grosser of the year was Hawaii, released in October. Two others were The Bible: In the Beginning (September) and A Man for All Seasons (December). But two of the top-grossers hit the jackpot in the summer: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (July) and Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN (June).

Pause on this last title. Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN was an indisputably lowbrow hit, a Disney comedy starring Dick Van Dyke. The fact that it earned $10.1 million (about $75 million today) might well have set critics worrying about American tastes. Worse, they might have concluded there was no hope, because from 1950 to 1970, twenty Disney films appeared in the annual top five. That record includes not only animated classics but In Search of the Castaways, That Darn Cat, and Darby O’Gill and the Little People–enough to make intellectuals despair of American moviegoers. Robin Crusoe‘s summer success might have seemed another sign of End Times.

Summer 1966 also saw The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, Fantastic Voyage, the remake of Stagecoach, a Bob Hope comedy, the low camp of Batman, and the high camp of Modesty Blaise. The 1966 counterpart to our spate of superhero sagas was a cycle of spy movies, somber or spoofy. The summer yielded Blindfold, Arabesque, and even The Man Called Flintstone. Along with these came Nevada Smith, Khartoum, What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?, This Property Is Condemned, and Wild Angels.

Some of these are well-remembered, mostly by viewers exposed at an impressionable age. For prestige there was and remains Virginia Woolf. For auteurists, there was Three on a Couch and Torn Curtain, and perhaps Modesty Blaise. As for the rest, most were and are still decried as junk.

Things were not looking good for American cinema. The Sound of Music had just won the Best Picture Oscar, a middlebrow shot across critics’ bow, and Pauline Kael was turning angry firepower on the massive threat posed by The Singing Nun. In the summer, the Times lambasted Hitchcock and Jerry Lewis. As far as I can tell, the follow-ups to the Bond boom pleased hardly anybody.

In sum, we forget just how godawful summer movies can be, year in and year out. The few we remember after Labor Day bob up from a river of sludge. We should be grateful for Indignation, Finding Dory, Lights Out, The Shallows, Hell or High Water, Don’t Breathe, The BFG, Kubo and the Two Strings, and probably half a dozen others I haven’t seen. (But not Jason Bourne, which I have.) Ben-Hur wasn’t as terrible as I’d been led to believe.

And of course, everybody’s pumped for the fall, for Snowden and The Arrival and The Birth of a Nation and La La Land and Manchester by the Sea and all the rest. 1966 critics were looking forward as well, but to what? Not only Hawaii, The Bible, and A Man for All Seasons but also Is Paris Burning?, Grand Prix, Any Wednesday, The Sand Pebbles and more spy movies (Gambit, The Quiller Memorandum). Not so exciting by our standards; Big Pictures were more square then.

True, also coming up in the fall of ’66 were The Fortune Cookie, Seconds, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Fahrenheit 451, The Professionals, Loves of a Blonde, and Blow-Up. But even then some critics stayed unhappy. Kael denounced Blow-Up, and Vernon Young intoned: “The party’s over. . . . Another phase of film history, in many ways the most creative, is drawing to a close.” Sound familiar?

Conversation starters and stoppers

End-of-movie writers argue that pop music and Quality Television are usurping the cultural place of film. But I’m skeptical, because I don’t think film is playing in the same arena.

Odd as it sounds, film has never been popular on the scale of other mass media. Before TV, radio listeners far outnumbered film audiences. Via radio and records, a hit tune reached more people than nearly any movie. Even today, radio audiences are surprisingly big. Nielsen reported in 2014 that just in the 18-35 age group, 65 million people listen to radio broadcasts each week. That’s nearly three times the average number of all viewers who attend movie theatres in a week.

Once TV came along, it became another truly mass medium. 73 million people, over a third of the US population, watched the Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964. TV is still the big game. More than 20 million people watch The Big Bang Theory each week. It’s reported that 8.9 million people watched the season finale of Game of Thrones in original cablecast, and 23 million in all its iterations. Yet, again, about 23 million people see all the movies playing in a given week.

The plain fact is that visiting a theatre to see a movie has been, throughout most of American history, a middle-class pastime. It’s relatively expensive, and getting more so. It’s not quite niche, not as rarefied as theatre or concert music or novels, but still not on the scale of other media. We ought to expect that memes will spread faster and more pervasively in pop music and television platforms.

Our critics are concerned that films aren’t part of what Raftery calls “the pop-cultural conversation.” “What in popular culture got people excited or even interested over the last few months?” asks Burr, going on to worry that movies didn’t do so. This is a strange criterion for judging films. Hula hoops, Rubik cubes, Chia pets, and Donald Trump’s coiffure have all been part of the cultural conversation. Some good films excite lots of people, and some don’t (partly because those people don’t know of them). And of course many people got excited by films Burr and Raftery considered bad, like Suicide Squad. Excitement may not be a great standard for excellence.

The cultural-conversation gambit suggests that mere popularity needs to be accompanied by a special jolt, the hum of nowness, the throb of hipness. Financially successful films like The Jungle Book or Finding Dory don’t give off much buzz. Where does that special ingredient come from? Apparently, now, the Netizens. It’s natural that critics, who are assigned to surf the waves of mass tastes, would identify important art with what’s trending on Facebook. It’s their job to hop on what’s hot.

Or in truth, help make it hot. When critics treat what’s buzzy as valuable, they agree with marketers, and cooperate with them. How many critics who loved The Dark Knight had been prompted by the campaign that played up “Why So Serious?” and other memes that publicists thought would stick? Kristin has documented how The Lord of the Rings marketers set the agenda for journalists by means of junkets and Electronic Press Kits (above), while wooing fans with carefully judged opportunities to participate online (a “pop-cultural conversation,” for sure). The typical big film is positioned by the marketing campaign, and even unanticipated responses, especially if the film is strategically ambiguous, can feed ticket sales.

The People don’t start the cultural conversation; they react to what they’re given. The conversation is started by the studios, and they try to channel it. They generate the “controversies” about making the protagonists of Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens a woman and an African American man. The critics pick up the story. (Remember: column inches.) Viewers dutifully enter their opinions on blogs, tweets, and comments columns–which the critics then re-spin. As Brody points out of Quality TV, it’s all about expanding discourse, indefinitely. Criticism begets “comments” which beget chitchat. This is less a conversation than a perpetually chattering flashmob.

A side note: I wonder if making cultural buzz a criterion of worthwhile cinema doesn’t owe something to the influence of Pauline Kael. She sent contradictory signals on this score, worrying that audiences were too easily bought off; the industry jollied them into accepting junk as fun. But she thought that one reason to like, say, Bonnie and Clyde was the fact that it was “contemporary in feeling.” It brought into movies “things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about.”

For a moment let’s accept the assumption that worthy movies have some broader cultural impact. How could we measure that? I suggest the Tagline Test. A movie enters the culture when a line becomes instantly recognizable. At its best, the tagline applies to an immediate situation. You step into a startling new setting and tell your friend you don’t think you’re in Kansas any more. You talk about your boss making you an offer you can’t refuse. You’re bargaining and you say, “Show me the money.” TV gives us plenty of catchphrases, of course. (“You rang?” “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” “Don’t have a cow, man.” “That’s what she said.”) This is one symptom of a show’s buzziness.

When I came up with the Tagline Test, I thought it supported the doomsayers’ diagnosis. I couldn’t think of many memorable lines from films after the 1980s. Had TV taken over the traffic in catchphrases? Crowdsourcing among two fairly diverse populations came up with a big set. Here’s a sample:

Hasta la vista, baby. Houston, we have a problem. That’ll do, pig; that’ll do. I drink your milkshake. The Precious (enunciated in a high voice). With great power comes great responsibility. Stop trying to make fetch happen. She doesn’t even go here. Stay classy. That escalated quickly. The first Rule of Fight Club… 60% of the time, it works every time. Little golden-haired baby Jesus in the crib. Schwing! Coffee is for closers. King of the World! Stay alive; I will find you.

The Big Lebowski is a virtual encyclopedia of them: The Dude abides. Obviously you’re not a golfer. That rug really tied the room together. Nobody fucks with the Jesus. So too Napoleon Dynamite: Whatever I feel like I wanna do GOSH! I’m pretty much the best in the world at it.

Maybe you don’t agree that these are all equally common; I didn’t know about the Mean Girls and Napoleon Dynamite ones. But all I need to show is that recent movies have entered the “cultural conversation” quite literally. Maybe it just takes months or years for movie taglines to replicate in everyday life. Anyhow, those who want movies to get all buzzy don’t have to worry. With Oscar season upon us, the frenzy will begin. In fact it already has, with Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation.

Who’s we?

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

Still, maybe it’s time to admit that we don’t own Hollywood. Maybe we never did, but it seems clear that with globalization “our” popular cinema is becoming something else–not exactly “theirs,” but not wholly ours either. Now You See Me 2 may have attracted only mild interest here: little cultural chitchat, except maybe among magicians, and $65 million box office (less than Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN). But it garnered $266 million internationally. Nearly a hundred million of that came from China, perhaps partly owing to long stretches set in Macau and short stretches featuring Jay Chou Kit-lun. And the director was Asian-American Jon M. Chu.

Now Lionsgate announces a Now You See Me spinoff, a feature co-production with China that will use local stars. So who owns this franchise? “Us” or “them”? If it disappoints us and pleases them, how does that mean that movies are so over? Maybe other countries’ cultural conversations are pulsing with talk of the Four Horsemen (one of whom is a woman).

It’s long been obvious that other film industries create their own versions of Hollywood. Europe, India, and Hong Kong have done it for decades. Current Chinese hits borrow from “our” rom-coms, action pictures, and comedies. In Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s The Mermaid, you can watch a blockbuster premise coming unglued. It’s a mixture of sentiment, message, slapstick, and bad taste; Hollywood twisted up in Chow’s characteristic funhouse mirror.

This won’t stop. One of the most astonishing and puzzling facts of contemporary cinema gets almost no press, maybe because it contravenes the death-of-film narrative. Over the last ten years, there has been a huge rise in the number of feature films.

In 2001, the world produced about 3800 features annually. The number passed 4000 in 2002, passed 5000 in 2007, and passed 6000 in 2011. In 2014, IHS estimates, over 7300 feature films were made in the world. There are now fifteen countries that produce over 100 features a year. As a result, only 18% of the world’s features come from North America. The boom took place despite the rise of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. And it happened despite the fact that American blockbusters rule nearly every national market. This may be a bubble, or it may be genuine growth. In any case, we ought to investigate the reasons that a great many people around the world stubbornly persist in making two-hour films. They don’t appear to care if We sense a summer slump.

While I was preparing this entry, Kristin and I went to Our Little Sister, Kore-eda Hirokazu’s 2015 film about three sisters abandoned, first by the father, then by their mother, and raised by the moderately stern oldest sister. The plot follows what happens when the trio takes in their half-sister after her mother dies. This is a movie that’s bereft of villains and almost totally lacking in conflict. The sisters’ misjudgments and flaws cause them problems, and sometimes they quarrel, but mostly we see decent people trying to lead happy lives, and largely succeeding. Compared to Kore-eda’s debut, Maboroshi (1995), it’s pictorially rather conventional. (That damn sidling camera.) But its episodic, open-textured plot, its quiet depiction of changes across seasons and years, and its casually serene vision of family and community make it one of the most enjoyable and moving films I’ve seen this year.

Based on the graphic novel Umimachi Diary, the film participated in Japan’s “cultural conversation.” It’s certainly a mainstream commercial movie, of a sort that Japanese studios have turned out for decades. It won solid attention on the festival circuit too. It earned a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, up there with Kubo and Hell or High Water. But such a reserved, sentimental film will never get the edgy buzz that our doomsayers want. Sentiment, after all, is anathema to our dominant mode of consuming pop culture, that of cool, ironic knowingness.

I don’t want to oversell Our Little Sister: Kore-eda is no Ozu. But this film and many others remind us that worthwhile films are still made, and released, and available outside the circus tent of Entertainment Weekly cover stories. (In this case, Americans’ thanks should go to Sony Pictures Classics, now celebrating its 25th anniversary.)

In short: Forget the zeitgeist; it likely doesn’t exist, apart from marketers’ dreams and journalists’ deadlines. Forget the cultural conversation; there’s not only one. Seek out the films that matter to you, and not “to us.” Stay classy!

Thanks to correspondents on two listserves, that of Communication Arts film folk and that of the Art House Convergence. A great many people made many suggestions, with the inevitable duplication, so thanking everyone by name would be protracted. But you know who you are.

My information on worldwide production and exhibition comes from issues of IHS Media & Technology Digest and Cinema Intelligence Report. Special thanks to David Hancock, Director of IHS Cinema division. Pamela McClintock’s “Summer Anxiety Despite Near-Record Numbers” in the 16 September Hollywood Reporter print edition contains the top-twenty film list I mention; that chart isn’t included in the online version.

On the summer 1966 US releases, see The Film Daily Yearbook of Motion Pictures 1967 (Film Daily, 1967), 144-168. I charted the year’s top-grossers from Susan Sackett, The Hollywood Reporter Book of Box Office Hits (Billboard, 1996).

My quotations from Pauline Kael come from her Bonnie and Clyde review reprinted in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1968), 47. My quotation from Vernon Young is the opening of his “The Verge and After: Film by 1966,” in On Film: Unpopular Essays on a Popular Art (Quadrangle, 1972), 273.

It’s probably irrelevant to mention that both Scorpio Rising and The Brig were released, in some sense, in summer 1966.

P. S. 18 September 2016: And see the practically real-time followup. Remember when blogs were like Twitter is now?

12,000 tickets are sold for premiere screenings of Baahubali (2015) in Hyderabad, India.