Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.

The Walk combines narrative and genre in an unusual way. The first part is a romantic comedy, the second a suspense film, and the third a lyrical piece. We suggest why in Talking THE WALK.

The way a film tells its story can vary considerably depending on whether it has a single protagonist, a dual protagonist, or a multiple protagonist (as in The Big Short, bottom). We examine some of the differences in Pick your protagonist(s).

Looking back over our blog as we passed 700 entries early this year, it occurred to us that several entries discussing principles of storytelling could be arranged to create a pretty good class in classical narrative strategy. We made up an imaginary syllabus in Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101. No tuition charged.

With the very end of the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise–the release of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third Hobbit film–we discuss the strengths of the film and the plot gaps left unfilled in A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

To celebrate Orson Welles’s 101st birthday, we examined some of the sources for some of the techniques used in Citizen Kane, a film we analyze in detail in Chapters 3 and 8. See Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts.

In Hollywood it is a common assumption that the protagonist(s) of a film must have a “character arc.” Filmmaker Rory Kelly, who teaches in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, wrote a guest entry for our site. Rory analyzes the character arc in The Apartment, with examples from Casablanca, Jaws, and About a Boy as supplements. See Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly.

James Schamus’ Indignation, an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, draws on novelistic narrative devices not in the original. In INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film, we suggest that those devices first became standard in cinema during the 1940s.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

Teachers and students always want to us add more about acting to our book. It’s a hard subject to pin down. We introduce the great stage actor Mark Rylance, who was largely unknown outside the United Kingdom before he won an Oscar for Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, and discuss how he achieves his expressively reserved performances in that film and the series Wolf Hall. See Mark Rylance, man of mystery. (Above at left, on set with Tom Hanks and Spielberg.)

In an era when most staging of actors in movies follows a few simple conventions, we examine the more imaginative ways of playing a scene on display in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950) in Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers young and old.

Continuing with the theme of acting and staging, our friends and colleagues, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have put a revised version of their in-depth study of silent-cinema acting online for free. Learn about it and the enhancements that internet publishing has allowed in Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

We look at the visual style of Anthony Mann’s Side Street (1949) and show how a simple, seemingly minor technique like a reframing can create a strong reaction in the spectator. See Sometimes a reframing …

Framing a composition is one of the most basic aspects of cinematography. We discuss centered framing, decentered framing, balanced framing, framing in widescreen movies, and particularly framing in Mad Max: Fury Road (above) in Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom.

In a follow-up entry, we discuss framing in the classic Academy ratio, 4:3, with emphasis on action at the edges of the frame: Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

For the new edition of Film Art, we had to eliminate our main example of sound technique, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige. But we put that section of the earlier editions online. THE PRESTIGE, one way or another takes you to it.

For those who have been looking for examples of internal diegetic sound, we take a close look (listen) at a sneaky one in Nightmare Alley: Do we hear what he hears?

The fact that the protagonist narrates The Walk in an impossible situation, standing on the torch of the Statue of Liberty and talking to the camera, bothered a lot of critics. We suggest some justifications for this decision in Talking THE WALK.

We offer brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated music from 2015 films in Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Many different filmic techniques can serve similar functions. Filmmakers of the 1940s had a broad range to choose from when they portrayed dead people, or Afterlifers, on the screen. We look at how their choices affected the impact of the scenes (as in Curse of the Cat People, above) in They see dead people.

Style and form in three films of Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and especially his most recent work, Sunset Song. See Terence Davies: Sunset Songs.

Style and form in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, on the occasion of its magnificent release by The Criterion Collection, in A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

Leo Hurwitz’s little-known documentary, Strange Victory (1948) has recently come out on Milestone’s DVD/Blu-ray. Released shortly after the end of World War II, it suggests that the Nazi atrocities were only an extreme instance of the cruelty of racism. We discuss the film and its relevance to the current political situation in Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948).

Experimental filmmaker Paolo Gioli makes films without cameras, or at least, he cobbles together pinhole cameras of his own from simple materials. The results are remarkable. We describe his work and link to a recent release of his work on DVD in Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

The eleventh edition of Film Art contains a new sample analysis of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. We discuss some additional aspects of the film in Wesworld.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

At the end of each year we avoid doing a standard ten-best list by choosing the ten best films of ninety years ago. For 2015, we dealt with The ten best films of … 1925 (including Frank Borzage’s Lazybones, above). It was a very good year.

A rare French Impressionist film, Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine, has been released on DVD/Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. We discuss the film and its background in L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema.

Film Adaptations

Our eleventh edition offers an optional chapter on film adaptations from a wide variety of art forms and even objects.

For thoughts on popular female novelists whose books were adapted into films during the 1940s and 1940s (and who sometimes became screenwriters), see Deadlier than the male (novelist).

Adaptations can be made from nonfiction as well fictional books. We look at how Dalton Trumbo’s life was made into a biopic in Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO.

In a series of entries, we have commented on the adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit into a three-part film. For an analysis of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third part, see A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump? (Links in that entry lead to earlier posts on this subject.)

As always, we have blogged about some recent books and DVDs/Blu-rays. See here (Vertov, sound technology, 3D), here, (Kelley Conway’s new book on Agnès Varda), here (experimental films, the first Sherlock Holmes, the Little Tramp), here (Tony Rayns on In the Mood for Love), and here (on some older foreign classics that have finally made it to home video in the USA, primarily those of Hou Hsioa-hsien). The publication of the eleventh edition of Film Art led us to look back on how it was written and some of the ideas that went into it. We took the occasion to introduce our new co-author, Jeff Smith. See FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

We were also profiled in Madison’s local free paper, Isthmus, by Laura Jones, reporter and filmmaker. She read Film Art as a student.

The Big Short (2015).

Sometimes a production still…

Frisco Sally Levy (MGM, 1927; dir. William Beaudine).

….makes you say, Jeepers.

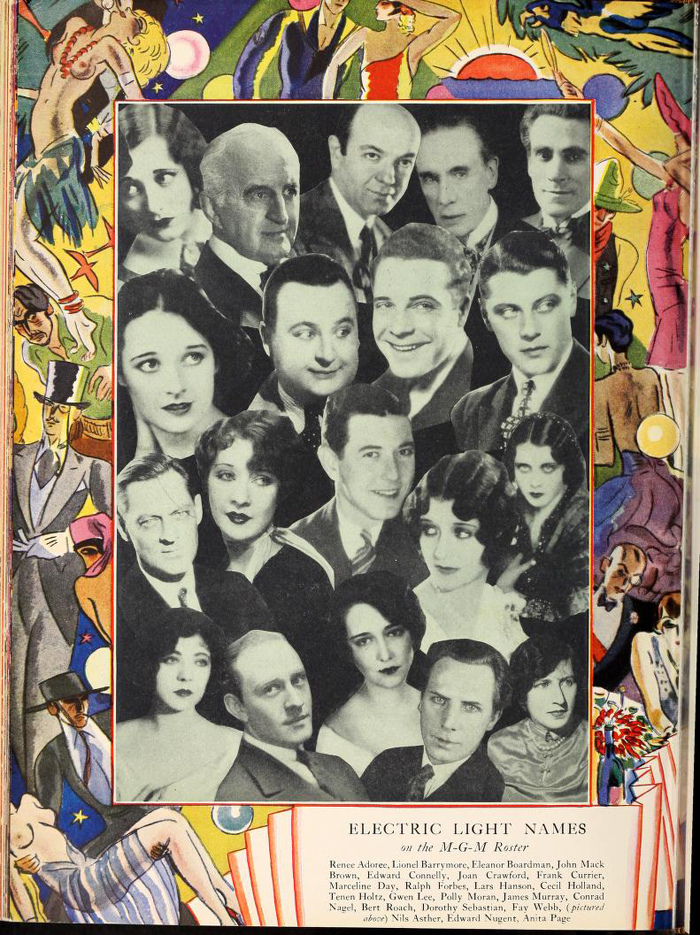

Henry Sapoznik is an outstanding performer and producer of music, a many-times Grammy nominee, and my colleague here at UW, where he heads the Mayrent Institute for Yiddish Culture. He’s also the grand-nephew of character actor Tenen Holtz. When Henry showed me this still from his collection, it gave me a buzz in many ways. Let me count them.

The Buzz Topical. Open-carry at the family table. It’s not just for breakfast any more. Joey, do you like movies with guns?

The Buzz Narrative. Here’s the plot, courtesy of the American Film Institute:

Sally Colleen Lapidowitz, the daughter of an orthodox Jewish father and an intensely Irish mother, is the steady girl of Patrick Sweeney, a motorcycle cop. Sally becomes infatuated with Stuart Gold, a Jewish dandy, who, though he is approved by her father, soon proves himself to be a worthless cad. Patrick rescues her from the dandy, and all ends happily in the Hebrew-Irish family.

Alas, no mention of this intimate scene.

The Buzz Ethnic-Shtick. Frisco Sally Levy belongs to a cycle of comedies centering on Irish and Jewish families. The most famous are Abie’s Irish Rose (stage play, 1922; film, 1928) and The Cohens and the Kellys (1926 film). Variety thought the movie a hoot, “averaging a dozen laughs to the minute.” Special praise was reserved for the Lapidowitz boys: “as a team of juvenile comedians these two youngsters are unsurpassed.”

Then there’s the gag involving a St. Patrick’s Day parade, evidently in a color sequence. Ma and Pa call out from the sidewalk, “Hello, Pat!” “And immediately every one of the carefully tailored, frock-coated, top-hatted gentlemen turn about with military precision and raise their hats in unison.” “Then,” the critic adds, “there are laughs with the close-ups of an ambulance and a German band leading the Irish patriots.” We’re told that Tenen Holtz puts across his role of paterfamilias well, rising above the caricatured Jewish tailor, which is all too often “obnoxious if over-drawn and too Jewish for comfort.” Ouch.

The Buzz Compositional: Would that today’s production stills were as nifty. The grouping, the eyelines, and Patrick’s gesture all drive our attention to the pistol. But space is left for us to notice Sally’s fixed stare at Patrick (mute devotion? apprehension at the gunplay?). And there are centrifugal attractions. There’s the younger daughter with her head slumped in her plate. Scared? Asleep? Bored? Sick? Doped? And of course the pooch, intent on table scraps, is missing the point. Nice apartment too, with both a phone and a writing desk. A symmetrical room for a symmetrical shot.

Alas, the film has not yet been found (a nice way of saying “lost”). Is there a collector out there with a copy? In the meantime, with stills like these we can make up our own stories.

Thanks to Henry for the still and permission to post it. The review is “Frisco Sally Levy,” Variety (13 April 1927), 13. See also “‘Sally Levy’ Takes Frisco for $26,200,” Variety (27 April 1927), 7.

Other entries in the “Sometimes…” series are: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…” and “Sometimes a reframing…”

Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World (12 May 1928).

Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO

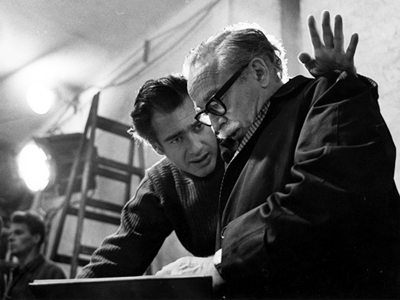

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo; John Frankenheimer and Dalton Trumbo.

DB here:

Who better to comment on the historical implications of Jay Roach’s Trumbo than our friend and collaborator on Film Art, Jeff Smith? He’s not only an expert on film sound, as he showed in his guest post on Brave, but he has written a book on the Hollywood blacklist. Jeff offers these observations on the film.

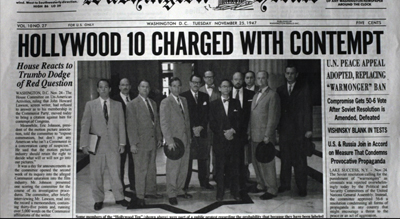

Last week, I was delighted to see that Bryan Cranston received an Oscar nomination as the star of Trumbo. Throughout the month of November, I was “johnny-on-the-spot” for local media interested in covering the new biopic about Dalton Trumbo. The story had a local angle. In 1962, Trumbo donated a large collection of scripts, notes, contracts, photos, and business correspondence to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Since then, scholars interested in the Hollywood blacklist have been making pilgrimages to Madison to probe Trumbo’s collection as well as the papers of five other members of the Hollywood Ten (Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner Jr., Herbert Biberman, Samuel Ornitz, and Alvah Bessie.)

I had done a lot of work with the collection, so I could do interviews with WMTV, WISC, The Wisconsin State Journal, and University Publications. Unfortunately I had not yet seen Trumbo, the Jay Roach film based upon Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography. I could talk about Trumbo’s life and career and the buzz I’d heard about the movie, but until it played Madison, I had to stay mum about the movie itself.

After a couple of weeks in distribution in limited release, Trumbo went wide just before Thanksgiving. Now that I’ve seen it, I am delighted to report that Trumbo merits every bit of the hype that surrounded it. To my mind, it is the best fictional film about the blacklist that Hollywood has yet produced.

Buoyed by a standout performance by Cranston, Trumbo is fast-paced and funny, and rather nimbly summarizes many of the political and industrial issues that led to the institution of the blacklist in 1947. It also showcases the effect that “unemployable” writers working on the black market had in undermining the rhetoric of the blacklist throughout the Cold War period. It became hard to say with a straight face that you were protecting American screens from the taint of Red propaganda when films secretly written by Communists were winning awards and topping the box office.

I was struck by some of the choices made by Roach and screenwriter John McNamara in bringing Trumbo’s story to the big screen. Although Trumbo’s career has been well documented by film scholars, Roach and McNamara faced the same challenges in adapting Cook’s biography that any filmmaker does in transforming a literary property into a classical narrative structure. How do you make Trumbo an active, goal-oriented protagonist despite the fact that he was the victim of historical circumstance? How do you deal with the welter of historical actors and subplots that populate Cook’s biography? How do you boil down a complex historical situation into a clear, transmissible narrative?

Witnesses, friendly and otherwise

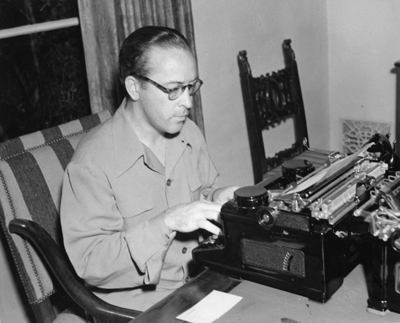

Dalton Trumbo at work.

Like many contemporary Hollywood biopics, Trumbo doesn’t try to convey the full sweep of its subject’s quite colorful life. It omits reference to young Dalton’s Christian Scientist upbringing, his early toils in the Davis Perfection Bakery, or even the publication of his first story in 1933. Indeed, the film also makes only offhand references to Trumbo’s early achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. These are briefly acknowledged near the film’s start through a series of shots in Trumbo’s office at the Lazy-T Ranch that reveal his award for Johnny Got His Gun and his Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle.

Instead the film focuses on the period of Trumbo’s career during which the screenwriter became one of Hollywood’s sacrificial lambs at the altar of HUAC’s anti-Communism. When the film begins in the mid-forties, Trumbo was the most highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood, earning $75,000 per script. In today’s currency, that amounts to about $800,000 per picture, a remarkable sum for someone under studio contract.

Just a few years later, Trumbo would appear as an “unfriendly witness” during hearings conducted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in October of 1947. As a result, he’d eventually be convicted of Contempt of Congress charges and sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky.

Although HUAC was concerned about the potential subversion of American screen content, it was not, in fact, illegal to be a member of the Communist Party. It was, however, a criminal offense to advocate for the overthrow of the American government according to the provisions of the Alien Registration Act (aka the Smith Act) passed in 1940.

About six months after HUAC concluded their hearings on Hollywood, a dozen Communist Party leaders were indicted for Smith Act violations. Defendants insisted that political change in America could be accomplished through democratic process and constitutional principle. But prosecutors claimed these statements couldn’t be trusted since Communists employed “Aesopian language” and therefore did not really mean what they said. The attack proved successful and effectively criminalized membership in the Communist Party as a result. Since any individual’s denial of revolutionary rhetoric would be viewed with suspicion, you were likely seen as guilty of the Smith Act if you simply owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto.

Even before the Foley Square trials, as they came to be known, many of the Communist Party’s rank and file, including the Hollywood Ten, also feared that they would be prosecuted on similar grounds if they admitted their membership. This proved to be one factor that favored the Ten’s failed “first amendment” defense. True, they risked getting cited for Contempt of Congress. But that had the prospect of looking more dignified than simply being hauled off in cuffs on Smith Act charges.

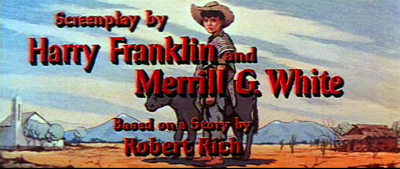

When he returned from prison, Trumbo encountered an industry that wanted him, but not his name on the credits. Producers recognized his talent, and he continued to write through the circuitous network of fronts and pseudonyms. Trumbo would win two Oscars for his work as a black market screenwriter: one for the Gregory Peck/Audrey Hepburn classic, Roman Holiday (below) and another for a Disneyesque “boy and bull” story, The Brave One.

By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s name would once again grace movie screens as the credited screenwriter on Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and on Otto Preminger’s Exodus. This moment essentially ended what remained of the Hollywood blacklist. In moving from the limelight to the shadows and back again, Trumbo’s life had the kind of plot arc that Hollywood loves. It’s a story of redemption in which the hero overcomes overwhelming odds to regain the professional respect and recognition he’d been denied.

Although all of this suggests that Trumbo is a pretty conventional biopic, it’s quite unconventional in its treatment of the blacklist. As the late Jeanne Hall noted years ago, Hollywood’s representation of this dark chapter of its past was surprisingly evasive, getting on the right side of history but for all the wrong reasons.

Bad Faith in Appleton

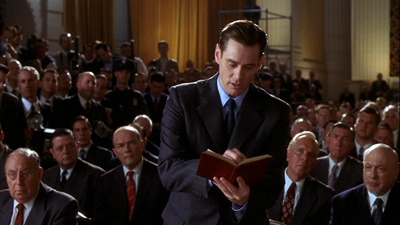

The Majestic (1999).

In titles like The Way We Were, The Front, and Guilty by Suspicion, filmmakers pulled a “bait and switch.” They substituted obvious cases of injustice for the much messier questions posed about HUAC’s abrogation of basic civil rights protections. The Hollywood Ten tried to defend themselves on First Amendment grounds, questioning whether HUAC itself had the right to invade their privacy or to limit their freedom of assembly. But in most of these earlier films about the blacklist, HUAC’s inquiry eventually entangles someone who was never a member of the Communist Party. In The Way We Were, the WASP-y Hubbell comes under suspicion for his relationship with the Jewish radical, Katie. In The Front, Howard comes under suspicion after selling black market scripts by Communist writers under his own name. Both of these instances present obvious cases of individuals wrongfully accused. They recruit our sympathies for characters that suffer as a result of HUAC’s tactics, but gloss over more fundamental questions about whether someone should be denied employment on the basis of their political beliefs.

No film, however, displays the equivocation evident in previous representations of the blacklist as vividly as Frank Darabont’s The Majestic. The protagonist, Peter Appleton, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has just been named by the committee. Distraught, he takes a drive out of Hollywood, but has an accident en route. Suffering from amnesia, Appleton finds himself in the small town of Lawson, California where is mistaken for Luke Trimble, a soldier killed in action some nine years earlier. Appleton becomes immersed in the Lawson community, helping his “father,” Harry, restore the small town theater that gives the film its title. Prompted by a combat film shown in the Majestic, Appleton regains his memory, and confides the truth of his situation to his new girlfriend. After his car is discovered, federal agents give Appleton a summons to testify about his Communist affiliations.

During the climax, Appleton appears before HUAC with the aim of clearing himself. Congressman Elvin Clyde confronts Appleton with evidence that he attended a meeting of the “Bread Instead of Bullets” club. Appleton pleads innocence, saying he only went because he was a “horny, young man” seeking to impress his date, Lucille Angstrom. Just as he is about to deliver his prepared statement purging himself of Communist associations, Appleton changes his mind. Instead he gives an impassioned speech that cites his First Amendment rights and denounces the investigation as a betrayal of America’s real ideals. Appleton saunters out of the hearing to the loud applause of onlookers. Yet Appleton’s lawyer later tells him that Angstrom is currently a CBS producer on Studio One, and his reference to her as a member of the Communist front organization is viewed as cooperation with the Committee.

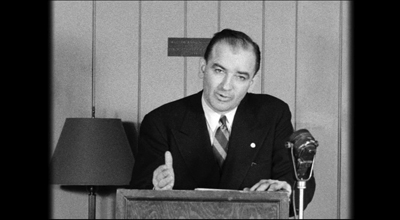

In The Majestic’s civic fantasy, the committee hearing revives the “wrongly accused” trope seen in earlier blacklist films. Worse, it shows its hero successfully using the First Amendment legal defense that had spectacularly failed when the Hollywood Ten used it during the 1947 hearings. Moreover, because Appleton is a political naïf, his inadvertent naming of names redounds to his benefit. Given the film’s hopelessly confused politics, perhaps there is unintentional irony in the fact that Appleton is also the name of the Wisconsin hometown of Senator Joseph McCarthy (below), the man synonymous with the Cold War’s anti-Communist campaign.

Trumbo, in contrast, doesn’t pull any punches. The film condemns HUAC’s activities not because it was prone to wild, unproven accusations like those of McCarthy, but rather because the very nature and essence of its inquiry was itself an abuse of power. The movie does nothing to deny Trumbo’s guilt. Indeed, the real-life Trumbo freely admitted it. In the 1976 documentary Hollywood on Trial, Trumbo described his reaction to his trial thusly: “As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since.”

Yet, while not excusing Trumbo’s actions, the film dramatizes the debilitating effects of being blacklisted, both in his professional and personal life. The burden of Trumbo’s black market work put a strain on his marriage and his family, all of whom were enlisted to perform services he himself could not do publicly.

The blacklist: More than Red-baiting

Besides providing a more accurate picture of Red-baiting and its effects, Trumbo also proves remarkable in making passing reference to some of the important secondary causes that eventually led to the blacklist. An early scene, for example, shows Trumbo (above) on a picket line during the vituperative Congress of Studio Union strikes that took place in 1945. Film historian Jon Lewis argues that one reason for the studio’s cooperation with HUAC’s investigation was that it served their interests in their long-term relationship with Hollywood’s craft guilds. Once Communists within the film industry’s labor unions became targets of government scrutiny, only the more moderate factions remained. Whether or not HUAC’s investigation was a direct cause, Hollywood did not experience another strike until more than four decades later.

Trumbo refers to another cause of the blacklist: anti-Semitism. Although it was something of a stereotype, Communists were popularly associated with European Jews. In fact, when Warner Bros. released I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, several moviegoers wrote studio head Jack Warner complaining that the film repeated the lie that all Jews were Communists. Said one Julius Newman of Roxbury, Massachusetts: “I demand that this dangerous, rotten, and libelous bit of propaganda be withdrawn immediately before some Jewish mother somewhere, gets her son’s skull cracked for Mother’s Day.”

The perception that anti-Semitism was an underlying cause of the blacklist was aided by the fact that three of the Committee were members of the Ku Klux Klan at the time of the 1947 hearings, including the Chair, J. Parnell Thomas. Moreover, in a speech before the House of Representatives, another HUAC member, Mississippi Democrat John Rankin, attacked members of the Committee for the First Amendment, who had lobbied on behalf of the Hollywood Ten. Rankin claimed that certain performers were suspect because their Anglicized names hid their actual Jewish origins:

One of the names is June Havoc. We found that her real name is June Hovick… Another one is Eddie Cantor, whose real name is Edward Iskowitz. There is one who calls himself Edward Robinson. His real name is Emanuel Goldenberg. There is another here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg.

Screenwriter John McNamara wrote a similar speech for Trumbo, but placed it in the mouth of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. When MGM boss Louis B. Mayer reminds Hopper that the legal situation was complicated by the fact that several of the Hollywood Ten had contracts, she responds:

Then how about I make crystal clear to my thirty-five million readers who runs Hollywood and won’t fire these traitors? How about I name names, real names? Like yours, Lazar Meir; or Jack Warner, Jacob Varner; Sam Goldwyn, Schmuel Gelbfisz.

The presence of Hedda Hopper in Trumbo hints at a third underlying cause of the blacklist: the role of the trade press and gossip columnists, who prosecuted and enforced it. Hopper was not alone in this endeavor. Publishers like Billy Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter and columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan “cheered” HUAC’s efforts from the sidelines. They also helped the enforcement of the blacklist once it was instituted, calling public attention to the surreptitious presence of banned writers on the black market.

All of these elements in Trumbo’s script make it a richer, more sophisticated depiction of the Hollywood blacklist than that offered by its predecessors. They also remind us that its operations were about more than just politics. Once the blacklist was established, studio bosses gained the upper hand in their dealings with labor, gossipmongers used rumor and accusation to fill column inches and sell papers, and anti-Semites exploited the common association of Communism and Jewish intellectuals to thwart activism among progressives, including those in the Civil Rights movement.

In sum, Trumbo offers a more nuanced sense of the various factors at play at the time of the blacklist than virtually all of its cinematic predecessors. This makes it all the more surprising then that the film nonetheless rewrites history in other ways. In an effort to both streamline and personalize its protagonist’s story, Trumbo invents new characters, revises the order of historical events, and shorts the achievements of other black market screenwriters who also contributed to the blacklist’s ultimate demise.

The eleventh member of the Hollywood ten

Although most film audiences expect that movies will generally portray historical events with some degree of accuracy, Hollywood cinema rewrites history all the time. Despite the fact that this is common practice, some films that take such liberties are hurt by negative publicity, especially around awards time. Recall the controversy surrounding Selma’s depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as an opponent of Martin Luther King’s famous march rather than as a “behind the scenes” ally. Some believe that the loud complaints coming from the LBJ camp cost director Ava DuVernay an Oscar nod.

Trumbo is no exception to this principle, even though it has been unusually forthright about the changes made to the historical record. My spidey senses were alerted to this during the movie when they introduced Louis CK’s character as “Arlen Hird.” I’d never heard of Arlen Hird.

Both in interviews and in an article in the New York Times, screenwriter John McNamara has acknowledged that Hird is a composite character, whose traits and experiences are based on five other members of the Hollywood Ten. Louis CK, for example, physically resembles the real-life Alvah Bessie, who, like the character, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish civil war.

Moreover, when Hird is in prison, he hears a radio broadcast of Edward G. Robinson’s “friendly” testimony. Robinson calls him “the top fellow who they say is the, uh, commissar out there,” a swipe that blacklist historians would immediately associate with John Howard Lawson. And sadly, like Samuel Ornitz, Hird dies after battling cancer, having never seen the blacklist come to its ignoble end.

As Nicolas Rapold observes in the Times, Hird is meant to stand in for other Communist screenwriters whose attitudes were more doctrinaire than Trumbo’s. Yet I believe the real purpose of using a composite character is to simplify the historical record to make it more digestible for the viewer. Rather than tracing out Trumbo’s relation to all of the eighteen other “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed by HUAC, McNamara opts to consolidate them into a single character. Such a decision makes some intuitive sense, since viewers would be hard pressed to keep tabs on a parade of many characters. By creating Hird as a composite, Trumbo’s interactions with him gain vividness and salience.

Still, McNamara’s narrative technique is merely one approach among a larger menu of options, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. He could have treated the Hollywood Ten as a group protagonist, who all share the same goal in legally challenging HUAC’s authority. Such a gambit, though, would have displaced Trumbo from the center of the story early on. That decision would have weakened the causal motivation behind his later emergence as a black market crusader.

Alternatively, McNamara could have dramatized Trumbo’s individual interactions with Bessie, Lawson, and Ornitz, et.al., using a superimposed title to identify each one. The gain in accuracy, though, would likely mean a loss of dramatic clarity and a mildly more self-conscious style of narration. More important perhaps, it also would make for a less emotionally engaging story. The film shows Hird confiding in Trumbo at the Lazy-T ranch, participating in the Ten’s legal strategy, serving his prison term, and undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The accumulation of these details provide for a more fully fleshed out character. There’s also the opportunity to feel empathy for Hird’s children at his funeral, an effect that couldn’t have been as focused if Hird’s problems were scattered among separate individuals.

None of this is meant to suggest that McNamara absolutely made the right choice in deciding to treat so many members of the Ten as a composite. Rather, it is simply the recognition that such a technique is the result of a deliberate choice and further that one creative decision can lead to a cascade of others. Had McNamara stayed doggedly faithful to the historical record, Trumbo would have been a different film, but perhaps not a better one.

Perhaps we should recognize that screenwriters often must adapt historical narratives in the same way that they adapt literature. And the same sorts of questions about fidelity will bedevil us as when films change details of our favorite novels and stories. Rather than being dogmatic in expecting that historical films stick close to the facts, maybe we simply should ask whether the film is faithful to the spirit of the historical record, especially when its creators are so open and honest about the changes they made. Such a stance would at least recognize the difficulties faced by screenwriters in balancing the weight of classical narrative conventions against the strict measure of historical accuracy. If, as many screenwriters argue, films differ from literature in their emphasis on conflict and action, then the decision in Selma to treat LBJ as an obstacle to Martin Luther King’s goal makes a certain dramatic sense. Here again, one can debate the merits of that creative choice. But at least we do so with a fuller understanding of why such choices are made in the first place.

Get me rewrite!

Besides creating composite characters, McNamara rewrites history in other ways. Perhaps the most obvious is when he creates a scene in prison between Trumbo and HUAC chair, J. Parnell Thomas, which never actually happened. True, Thomas was convicted on corruption charges and was sent to federal prison. But he served his term in Danbury, Connecticut rather than Ashland, Kentucky where Trumbo was incarcerated.

In this case, the real-life story proves more entertaining than what appears in the film. While at Danbury, Thomas encountered two other members of the Hollywood Ten – Lester Cole and Ring Lardner, Jr. — serving their time on Contempt of Congress charges. Upon seeing Thomas working in the prison yard, Cole made a wisecrack that led the former HUAC chair to respond, “I see that you are still spouting radical nonsense.” Cole’s sharp retort: “And I see you are still shoveling chicken shit.”

In other cases, McNamara revises the chronology of events. In the film, Trumbo first meets with the King Brothers, Frank and Hymie, just after he is released from prison. In reality, Trumbo started working for the King Brothers just weeks after his HUAC testimony. Almost immediately after being suspended by MGM, Trumbo did black market work on the screenplay for the King Brothers’ cult classic, Gun Crazy, using fellow writer Millard Kaufman as a front. With Kaufman serving as intermediary, the Kings likely did not know of Trumbo’s involvement. But the brothers began working directly with Trumbo shortly thereafter. In fact, Frank King personally visited the Lazy-T ranch just prior to the Trumbo’s departure for prison, offering to pay him $8,000 to write the script for Carnival Story.

Trumbo coyly acknowledges the screenwriter’s contribution to Gun Crazy by featuring posters of the film in several shots. But by revising the historical circumstances of Trumbo’s first involvement with the Kings, the film more or less denies him actual credit attribution, ironically engaging in the same sort of opportunism displayed by the producers who surreptitiously hired him.

McNamara’s most significant changes to blacklist history, though, involve omissions. Trumbo’s Oscar victory for The Brave One is well documented and the episode – both in the film and in real-life – neatly captures his role as industry gadfly. But the same year that the mysterious “Robert Rich” won the Academy Award for Best Original Story, Michael Wilson also was nominated for a project for which he was publicly denied screen credit.

Wilson had completed a first draft of Friendly Persuasion for director Frank Capra in 1946, but no film was made from the script until producer/director William Wyler took over the project in 1955. When it came time to determine the screenwriter credit, Wyler suggested that it go to Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West for their extensive revisions, including many rewrites completed on set during shooting. When Wilson became aware of this, he immediately protested Wyler’s decision and forced arbitration by the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild ruled in Wilson’s favor, but also reminded the film’s distributor, Allied Artists, that they could legally deny credit to any screenwriter who had failed to clear himself before HUAC. When Friendly Persuasion was released in 1956, its only writing credits read “From the Book by Jessamyn West.”

Despite a good deal of press coverage of the dispute, the incident might have been a mere blip on the cultural radar if not for the 1957 Oscar nominations. When they were announced, a film with no credited screenwriter unexpectedly received a nomination for a screenwriting award. And with public acknowledgement of Wilson’s contribution to Friendly Persuasion more or less verboten, the text of the nomination simply said the writer was ineligible under Academy rules.

Worried that a public victory by a blacklisted writer would give the industry a big ol’ black eye, the Academy reportedly instructed Price Waterhouse to excise the nomination from the Oscar ballots that were sent to voters. Yet, even though the Academy essentially rigged the vote against Wilson, Groucho Marx offered an incisive quip about Wilson’s situation at the Writer’s Guild Awards banquet held about two weeks before the Oscars. Said Groucho, “The Ten Commandments. Original story by Moses. The producers were forced to keep Moses’s name off the credits because they found out he had once crossed the Red Sea.” Given all the effort that went into preventing Wilson from receiving the award, Trumbo’s Oscar win as “Robert Rich” must have tasted even sweeter. The award was given in absentia by Deborah Kerr, and Jesse Lasky, Jr. accepted it.

Moreover, the Rich incident was hardly the last humiliation that the Academy would suffer. The very next year novelist Pierre Boulle received a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination for The Bridge on the River Kwai, which was based on his book. But Boulle had been a front for Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, who had taken the assignment as black market work for producer Sam Spiegel. When Boulle’s name was announced as the winner, the novelist was nowhere to be found. Instead, Kim Novak accepted the award on his behalf. But insiders knew exactly why Boulle was absent. As someone who wrote and spoke in French rather than English, his stumbling acceptance speech would have exposed the hypocrisy by which Foreman and Wilson were denied an award that they merited. (Sadly, neither Foreman nor Wilson would live to see their work duly recognized. In 1984, the Academy posthumously recognized them as the true authors of Kwai’s screenplay.)

Nathan E. Douglas = ?

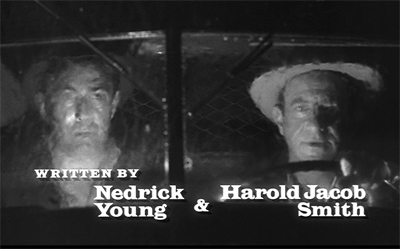

The original credits sequence of The Defiant Ones (1958) listed Nedrick Young as a coauthor under his pseudonym Nathan E. Douglas. He appeared in a bit part coinciding with his credit listing, along with coauthor Smith, in the cab of the truck. Video versions such as this have restored his name.

Things didn’t end there. The Oscar nominations in 1959 saw yet another brewing controversy regarding eligibility of a black market scribe. The writing team of Harold Jacob Smith and Nathan E. Douglas earned a nod for Best Original Screenplay for The Defiant Ones, even though the latter was a pseudonym for blacklisted writer Nedrick Young. If anything, Young’s participation in the making of The Defiant Ones was signaled by producer-director Stanley Kramer’s giving him a notable cameo in the film. During the opening credits, Young and Smith are both seen as prison guards riding in the front seat of a truck used to transport convicts. In a rather coy gesture, when the film’s writing credits are shown, Young’s pseudonym “Nathan E. Douglas” is superimposed over the man himself. Even though the general public didn’t know Young from Adam, his cameo made his participation an open secret in Hollywood.

During awards season, Young as “Nathan Douglas” collected a lot of hardware, including awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Writer’s Guild of America. With the nominations imminent, leadership within the Academy recognized that a third straight public relations disaster was in the offing. Just before Christmas in 1958, former Academy president George Seaton approached Young and Smith seeking assistance in overturning the Academy bylaw prohibiting blacklisted personnel from eligibility for awards. For his part, Trumbo himself stayed abreast of the situation and even rescheduled a media interview order to avoid fanning any flames of opposition from within the Academy.

On January 15, 1959, Seaton, Young, and Trumbo all got their wish as the hated bylaw was officially rescinded, passed by the Academy’s Board of Governors with near unanimous support. Two days later, Trumbo confirmed to newsman Bill Stout that he was, indeed, Robert Rich. On Oscar night a few months later, Young enjoyed the spotlight in a way that had been denied his predecessors. And when The Defiant Ones won the Oscar for the Best Story and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, Young strode to the podium along with Smith and offered a humble thank you. Ward Bond, one of John Wayne’s allies in the Motion Picture Alliance for American Ideals, observed: “They’re all working now, all these Fifth-Amendment Communists. We’ve just lost the fight. It’s as simple as that.”

Where does all of this backstory fit into the story told in Trumbo? As it turns out, nowhere. In choosing to concentrate on Trumbo’s story, the movie keeps all of this rich contextual material offscreen. As is often the case, the historical realities surrounding the end of the Hollywood blacklist were much denser, messier, and more complex than what can easily fit into a standard two-hour film. Classical Hollywood narrative, with its emphasis on goal-orientation and clearly motivated, causally linked events, tends to nudge screenwriters away from the sprawl more often found in novels or television miniseries. In the case of Trumbo, screenwriter John McNamara likely opted for the virtues of clarity and concision. He concentrated only on those incidents that directly involved the titular character, eliminating or minimizing anything that would detract from that narrative focus.

That being said, the creative choices of McNamara and director Jay Roach are, above all, choices. The screenplay for Bridge of Spies, for example, manages to convey something of the complex bilateral negotiations that linked the downing of U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers with the seemingly unrelated espionage case of KGB officer Rudolf Abel. One could imagine Roach and McNamara devising very brief scenes of Wilson, Foreman, and Young in their Academy imbroglios. Or alternatively, the film might have included Trumbo’s voiceover reading the text of his actual letters to Wilson, many of which commented on the perpetually changing conditions of the black market. As before, the inclusion of such material wouldn’t necessarily make Trumbo a better film. But it would make it a different one.

Although Dalton Trumbo led the fight against the blacklist, often using the industry’s greed, hypocrisy, and mendacity against itself in the process, my brief synopses of these other screenwriters’ Academy Award travails show that he was not alone. Many individuals taking small incremental actions led to the blacklist’s end. It wasn’t smashed; it crumbled through erosion. The fact that one of Hollywood’s “untouchables” was able to openly accept a major industry award made open screen credit a logical next step. Dalton Trumbo happened to be the lucky individual to regain his name without having to bow and scrape before HUAC. But even he knew it could just as easily have been Nedrick Young. Or Michael Wilson. Or Albert Maltz.

Come Oscar night on February 28th, if Bryan Cranston is lucky enough to hoist the Best Actor prize above his head, it will be a fitting tribute to a man whose struggles with this same institution helped to define him and his era. Yet an Oscar victory would also pay tribute to all those whose stories have not reached the screen, but whose grit and determination made Trumbo’s triumph possible. And Mr. Cranston, if you get to deliver that acceptance speech, be sure to remember all those unsung heroes that joined Trumbo in the fight.

Trumbo is based on Bruce Cook’s biography, which was first published in 1977. Readers should also check out Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo’s massive, exhaustively researched new biography, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical. Ceplair is also the co-author, with Steven Englund, of the standard work on the Hollywood blacklist itself, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics and the Film Community, 1930-1960. My book, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds, also considers Trumbo’s contribution to Spartacus.

Trumbo’s collection of correspondence, speeches, business papers, scripts, and photographs is held at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. A rich sampling of material from it is available here. Several of the photos in this entry come from the WCFTR collection. Go here to listen to excerpts from his HUAC testimony.

Excerpts from John Rankin’s infamous speech about Jewish actors in Hollywood can be found in Gordon Kahn’s Hollywood on Trial: The Story of the Ten Who Were Indicted. Trumbo himself commented on the role of anti-Semitism in HUAC’S investigations in The Time of the Toad: A Study in Inquisition in America.

Franklin Leonard interviewed John McNamara last November about his work on Trumbo for his Black List Table Reads podcast. Nicolas Rapold offers a useful guide to the individuals profiled in Trumbo, including its composite characters. If you’re interested, you can see actual footage of the announcements of various screenwriting awards at the Oscar ceremonies of 1957, 1958, and 1959.

For more on how adaptation works, see the thirteenth chapter of the new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming next week. That chapter is available for courses as an add-on to both the printed edition and the McGraw-Hill electronic edition.

Trumbo.

How he (mostly) got away with it: Matthew H. Bernstein on Preston Sturges

DB here:

Matthew H. Bernstein is a long-time friend and a superb scholar. His biography of Walter Wanger has become a classic of Hollywood business history, and his many books and articles have refined our sense of American cinema. When we learned of his research into Sturges (a favorite of this blog), we were happy to propose that he do a guest entry. Here’s the lively, trailblazing result.

How should films portray sex and marriage? Hollywood’s Production Code, established in 1930, set forth some definite ideas.

Sex

The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing. . . .

Scenes of Passion

They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown . . .

Seduction or Rape

They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

They are never the proper subject for comedy.

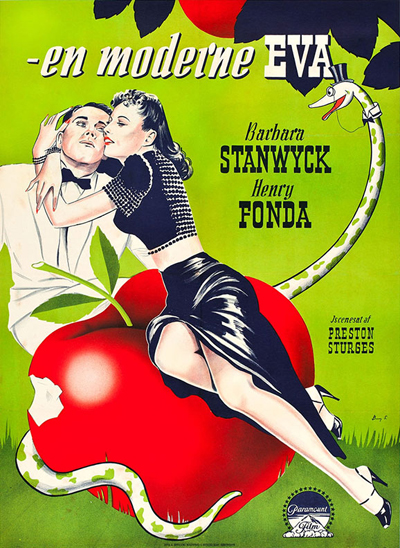

Those of us who savor Preston Sturges’s great romantic comedies of the 1940s—The Lady Eve (1940), The Palm Beach Story (1942) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944)—admire them in part for their violation of just about all these tenets. They are full of “suggestive postures” like the lengthy chaise longue scene in The Lady Eve. Their central topic is often the seduction of men by women (The Lady Eve, The Palm Beach Story and arguably Miracle). References to extra-marital sex, contemplated or accomplished, abound. And all three films ridicule “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” into the ground. Film critic Elliot Rubinstein once observed, “If Sturges’s scenarios don’t quite invade the province of the flatly censorable, they surely assault the border outposts, and some of the lines escalate the assault into bombardment.”

The Production Code Administration, on paper and in practice, was particularly obsessed with regulating the depiction of female sexuality on screen. Yet Sturges’ attacks on conventional morality are launched by heroines: con artist/card sharp Jean/Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve, the hard-headed Gerry Jeffers (Claudette Colbert) in The Palm Beach Story and the naïve man-bait Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. They are all variants of what Kathleen Rowe has called the “unruly woman,” characters who create “disorder by dominating, or trying to dominate, men,” and being “unable or unwilling” to stay in a woman’s traditional place. Mary Astor’s much-married Princess Centimilia/Maude in The Palm Beach Story deserves an honorable mention here too.

True, by each film’s conclusion, the Sturges heroine agrees to get or stay married. She fulfills the conventions of romantic comedy and the stipulations of the PCA. Yet in each film the path to a proper end looks so much like a roller-coaster ride that the significance and sanctity of marriage come to seem ridiculous.

How did Sturges get away with so much? A look behind the scenes at the negotiations around The Lady Eve can help us understand his strategies. It also shows that the Code was more flexible and fallible than we often realize.

Convolutions in the Code

Sturges had one advantage at the outset. He worked in a genre that was already testing the limits of the Code. Granted, the PCA in 1934 aimed to regulate film content in every genre. None, however, flaunted, even parodied, the strictures of the Code more thoroughly than screwball comedy did. Rubinstein puts it well: “The very style of screwball, the complexity and inventiveness and wit of its detours around certain facts of certain lives, the force of its attack on the very pieties it is pledged to sustain, cannot be explained without recognition of the censors. Screwball comedy is censored comedy.“

By the end of the 1930s, filmmakers were pushing hard against censorship. Romantic comedies were growing more risqué by the month, as shown by 1940 releases like My Little Chickadee, The Philadelphia Story, The Road to Singapore, Too Many Husbands, The Primrose Path, Strange Cargo, and most especially, This Thing Called Love. A sort of arms race took place, and Sturges, emerging as a writer-director in 1940, benefited from this escalation.

Just as important is a fact that many fans of Hollywood still don’t realize. We like to think that daring filmmakers were charging boldly against an iron wall, with chief censor Joseph Breen and his associates setting forth implacable demands. But the administration of the Code was not a mechanical, totalitarian affair. It was most often a matter of negotiation.

Releasing Hollywood’s product, even risqué films, benefited all parties involved. If the Code were enforced with absolute rigidity, the industry would suffer. Some films would have to be abandoned. Then urban audiences would have found the safely released product pallid, and critics would have complained about bland output. Then as now, edginess sold, and at least some audiences were eager for it.

Accordingly, Breen and co. recognized that the Code could not be applied ruthlessly. Indeed, historians Lea Jacobs, Richard Maltby and Ruth Vasey have shown that the PCA, like its forerunner the Studio Relations Committee, often helped filmmakers find ways around the most stringent policy demands. Through a give-and-take, censors and filmmakers could settle on scenes and lines of dialogue that could avoid public outcry. No one flaunted and taunted the PCA as well as Sturges, yet Breen and co. often helped him find ways of rendering suggestive situations without baldly transgressing the Code.

One typical filmmaker/PCA tactic that favored Sturges was an appeal to ambiguity. Far from being inflexible, the staff recognized that not every viewer picked up on a lewd line or suggestive situation. Some viewers would find no innuendo in a sexually-charged scene. (The 1940s critic Parker Tyler referred to this as “the Morality of the Single Instance.”) For example, in The Lady Eve, there’s a fade-out from Charles’s and Jean’s passionate embrace in the bow of the ship at night to the fade in of the ship’s prow slicing through the ocean the next morning.

That passage would suggest to the naïve viewer that they kissed for a while and went to their cabins separately. After all, in the morning we find Jean getting dressed in her stateroom and talking with her father. Then we see Charles on deck alone, waiting for Jean.

But the sophisticated viewer would understand that the earlier fade-out indicated what Joseph Breen routinely called “a sex affair.” (The ocean spray on the fade-in could be seen as a very subtle extra touch.) Crucially, Jean’s later statement to Hopsy after she is unmasked as a cardsharp sustains both readings. “I’m glad you got the picture this morning instead of last night, if that means anything to you . . . it should.” When self-regulation was well-calibrated—and this was a moment-to- moment, scene-by-sceene, film-by-film achievement—there was wiggle-room that would let innocent viewers remain innocent while letting sophisticated viewers feel sophisticated.

Apart from the increasing eroticism in screwball comedy and the willingness of the PCA to work with filmmakers to allow double layers of meaning, Sturges benefited from good timing. During this period, Breen grew more permissive in his application of the Code. He never explained why, but the late-1930s bombardment of questionable material was probably one cause. Breen was pretty exhausted after seven years of trying to accommodate the filmmakers’ increasingly outré ideas. He was so tired that he temporarily resigned in Spring 1941.

Sturges’ circumvention of the Code also depended on his personal qualities. Clearly he was a persuasive negotiator. The PCA correspondence shows Breen and his successor, Geoffrey Shurlock, rescinding countless directives they initially gave him to eliminate dialogue lines or bits of action. It’s likely that the PCA admired Sturges’ comic gifts and thus gave him greater room to maneuver than other directors enjoyed. (Much the same thing happened when the Studio Relations Committee had given leeway to Ernst Lubitsch prior to 1934.) Sturges also employed a tactic of overkill. In his scripts and in the scenes as finally staged and shot, he created so many potential infractions of the Code that to challenge each one would reduce the film to rubble, or reduce Breen and co. to stress-induced madness.

Still, Sturges played the PCA game. His convoluted plots stuck to the letter of the Code, always finally coming down on the side of pure romance and happy marriage. But they wreaked havoc with its spirit—often with the PCA’s sanction. By the premiere of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Sturges was relentlessly mocking the PCA’s regulations. It’s likely, I think, that the PCA was for the most part in on the joke.

After negotiations, which grew more elaborate with each title, each Sturges romantic comedy received a seal. The films made it through partly because of the PCA’s quixotic mandate, partly because the Code’s requirements had been loosened, and partly because of Sturges’ extraordinary skill in exploiting the Code. These are the crucial reasons Sturges got away with it. Along with his prolific comedic imagination, he was often aided by the very body that was supposed to be censoring him.

Once the Sturges film was released, the PCA staffers could wearily pat themselves on the back for a job well done. Yet critics’ reviews, complaints from state censor boards, and letters of protest from ordinary viewers indicate that the agency often badly misjudged how the films’ moral tone would be received. The PCA’s dual mandate—to try to give filmmakers the maximum freedom to create risqué situations but at the same time to uphold the Code–was a tightrope walk. With Sturges and other filmmakers, the agency lost its balance. Sometimes the PCA didn’t diminish the sexual dimensions enough, and sometimes the agency did not even notice elements that could give offense.

There were signs already, in the reaction to the 1940 burst of sexier films like The Primrose Path and This Thing Called Love. Local informants had asked MPPDA attorney Charles C. Pettijohn, “Doesn’t Mr. Hays have any influence with the producers any more, and has that fellow Breen out there killed himself or has he just been compelled to walk the gangplank?” Unlike the PCA staff, who had worked day by day to tone down an audacious script and had faced the charms of a persuasive filmmaker, local censorship boards reacted solely to a finished Sturges film. They merely saw what was on the screen. Many did not like what they saw.

Up the Amazon for a year

The PCA correspondence concerning The Lady Eve is surprisingly brief. Before the film was completed and a seal was granted, Breen sent only two letters to Luigi Luraschi, Paramount’s liaison on censorship. They strikingly illustrate how cooperative Breen could be when it came to scenes regarding illicit sex.

When he read Sturges’s first complete script of 7 October 1940, Breen had objections to many “questionable lines of dialogue.” Breen warned Sturges and Luraschi against anything “suggestive” in the scene between Muggsy and Lulu as they say their farewells before departing the expedition. In this brief exchange, Mugsy stiffly tells her “So long, Lulu…I’ll send you a post card” as she demurely (looking down) places a lei over his neck. This brief exchange directly undercuts Hopsy’s just-spoken, high-minded farewell to the Professor: “This is the way I’d like to spend all my time…in the company of men like yourselves…in the pursuit of knowledge.”

While it’s difficult to imagine Muggsy as a sexual partner to anyone, the woman’s downcast face and her gift of a lei could be seen to suggest her heartbreak.

Jean’s later, rapid-fire description of Hopsy’s many female admirers in the Main Dining Room of the S.S. Southern Queen originally contained comments about women who were “a little flat in the front” or “a little flat behind. ” These were cut because they were too physiologically specific about the female form. We hardly miss them, as Jean was permitted to deliver plenty of color commentary, as she detailed the women’s futile attempts to attract Hopsy’s attention.

However, Breen wrote the word “in” alongside certain demands he had made for eliminations in his 9 October letter, indicating that Sturges and Luraschi had persuaded him to relent. For example, Breen eventually accepted this exchange from Jean and Charles’s first evening together. Charles has suggested they go dancing:

Jean: Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?

Charles (after a pause): You’re certainly a funny girl for anyone to meet who’s just been up the Amazon for a year.

Jean: (after a pause): Good thing you weren’t up there two years.

Breen’s next letter (21 October) on Sturges’s revised script expressed satisfaction with all the changes made, noting that Jean’s line about heading to bed “will be delivered without any suggestive inference, or reaction.”

In the finished film, there is nothing arch about Stanwyck’s thoughtful, almost parental delivery of the first line, spoken as she looks straight ahead and then looks down to stub out her cigarette before she turns to face Charles. Likewise, her delivery of the second line is wry and mildly mocking yet almost compassionate. Still, the connotation remains that Jean is suggesting they sleep together. Instead, the couple proceeds to Charles’s cabin to meet his snake Emma.

Breen was particularly concerned about other allusive dialogue. At the Pikes’ party, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore) explains to Charles a fictionalized version of Jean’s family history which resulted in the existence of two sisters, one a lady, one a cardsharp. (Sir Alfred will later describe this as “Cecilia or the Coachman’s daughter, a gaslight melodrama.”) Breen insisted that Sir Alfred’s tale include a line indicating that Jean’s mother divorced her elderly earl before taking up with the groom “Handsome Harry” and giving birth to Jean. That way Jean’s birth would not seem illegitimate. Sturges obliged. Yet he somehow persuaded Breen to retain this later portion of the Alfred-Charles exchange, also alluding to an adulterous affair.

Charles: They [Jean and Eve] look exactly alike!

Sir Alfred: We must close our minds to that fact…as it brings up the dreadful and thoroughly unfounded suspicion that we must carry to our tombs, you understand…as it is absolutely untenable…that the coachman, in both instances…need I say more?

Why did Breen let Sturges keep in this suggestion that Handsome Harry was the biological father of both sisters, perhaps as the result of adulterous affairs? It is hard to say. True, the offending line concerns a “suspicion” voiced by Sir Alfred, rather than a fact. But Charles immediately affirms its likelihood: “But he did, I mean, he was, I mean…” before being shushed for the nth time by Sir Alfred. Here again, Breen consented to Sturges’s use of questionable material.

Breen’s greatest objection in his initial letter concerned pp. 70-74 of the first submitted script, which suggested “a sex affair.” “Inasmuch as this is treated without the proper compensating moral values, it is in violation of the Production Code, and will have to be eliminated entirely from your finished picture.”

The offending pages outlined a scene between Charles and Jean set on the deck of Jean’s cabin at the end of their first evening together. Just previously, Jean has caught Charles and her father the Colonel (Charles Coburn) playing double or nothing. Charles would then be called away to receive from the ship’s purser the incriminating photo of Jean, the Colonel and Gerald. Charles would then return to the gaming room table and the dialogue exchange with Jean about all women being adventuresses. Then Charles would ask Jean if they can go down to her cabin. There, Charles lights Jean’s cigarette; he “struggles to say something” but Jean tells him, “Kiss me,” and he obeys. (“He crushes her in his arms” as she “sinks back against the chaise longue.”) The film would then cut to a shot of the rail of Jean’s deck and of “the moonlit water beyond. A lighted cigarette arcs over the rail and down into the water. FADE OUT.”

This version presents Charles sleeping with Jean even though he knows from the purser’s photograph that she’s a cardsharp. As Brian Henderson notes, this arrangement of events would make Charles a cad, far worse than the hypocritical prig that he is in the finished film. Sturges eventually solved the problem by having Charles learn of Jean’s duplicity on the morning of their third day together at sea. But before Sturges made this change, Breen’s October 9 letter directed that Charles could not speak the line about going down to her cabin; that the scene could not play out on Jean’s private deck; and that “it would be better to have the embrace with the couple standing up.” The shot of the cigarette thrown over the railing also “should be omitted, on account of its connotations.”

In response, Sturges watered down the offending scene of passion and relocated it to the bow of the ship, where (in a reworking of a scene he had always envisioned) Charles recites his “I’ve always loved you” speech and they eventually embrace as the scene fades out. This created the PCA-approved ambiguity about what transpired sexually between them.

Here, Sturges’s solution to a problem of plot and characterization went hand in hand with the double-meaning practices of the Production Code. Sturges must have written the passionate private deck scene knowing full well that Breen would demand its elimination or transposition. His immediate agreement to revise it was likely a bargaining ploy to earn Breen’s goodwill to bank against other PCA objections.

When Sturges cut the cabin deck setting and the prone postures of pp. 70-74 from the first submitted script, he also saved a crucial part of Jean and Charles’s penultimate exchange as they enter Jean’s cabin.

Charles: Will you forgive me?

Jean: For what? Oh, you mean…on the boat…the question is, will you forgive me?

Although Breen accurately predicted that this bit of dialogue would “probably be acceptable” if the earlier scene “is cleaned up,” for now, Breen stated that their exchange had to be cut “by reason of its reference to the aforementioned sex affair.” In other words, Breen, not unreasonably, read Jean and Charles’s dialogue as referring only to their sleeping together, rather than to everything that transpired between them on the S.S. Southern Queen, including Jean’s duplicity and Charles’s narrow-mindedness. Forgiveness is of course a key issue in the drama of The Lady Eve.

Hix Nix Sexy Pix

The MPPDA issued its seal on 26 December 1940. Released in mid-March 1941, The Lady Eve passed the censors without cuts in Chicago and the states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. However, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania were a completely different story.

Some local censors demanded deletions of elements Breen had highlighted. Ohio and other localities objected to Sir Alfred’s dialogue about the fantasy fatherhood of Jean and Eve (“as it is utterly untenable that the coachman in both instances. . . .”). But most of the eliminations concerned elements Breen and his team had not commented upon. Among these were (again for Ohio, initially) Sir Alfred’s summary recap of the tale to Jean the next morning: “So I filled him full of handsome coachmen, elderly Earls, — young wives, and the two little girls who looked exactly alike.”

Other targets were Jean’s wisecracks. When Jean and Charles return from her stateroom after changing her shoes, the Colonel archly comments, “Well, you certainly took long enough to come back in the same outfit.” Jean’s reply–“I’m lucky to have this on. Mr. Pike has been up a river for a year”—offended Pennsylvania. Ohio objected to Jean’s comment, “That’s a new one, isn’t it?”, when Charles invites her into his cabin to see Emma.

Yet another instance concerned Charles’s exchange with Eve during their wedding night train ride. He is asking about her previous marriage to Angus.

Charles: When they brought you back, it was before nightfall, I trust.

Jean: Oh, no.

Charles: You were out all night?

Jean: Oh, my dear, it took them weeks to find us. You see, we’d make up different names at the different inns we stayed at.

Though Jean and Angus were married, the implication of using false names at a hotel (which Sturges would recycle for Trudy and her unknown husband in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek) was the deal-breaker for Ohio. Of course, one possible connotation of Eve’s many pre-Charles couplings is that not all of them were marriages. (If they were, this imaginary Eve is an early version of the Princess in The Palm Beach Story, another figure who satirizes conventional marriage.) Yet Breen’s only comments on this scene concerned Eve’s nightgown and particularly the scene’s blocking—that Eve’s revelations of her previous marriages occur away from the bed and that the bed be deemphasized throughout the scene.

Sturges must have made the case that there was no room to have the actors sit elsewhere. Meanwhile, Breen was distracted from what Jean was saying by where she was when she said it.

Local censors were most keenly opposed to two other scenes that Breen had ignored. Both take place in Jean’s stateroom.

In the first, Charles replaces Jean’s broken shoe. In one twenty-second two-shot, he kneels down to slip the shoe on her foot; looks over her foot and slowly looks up her leg all the way to her face; expresses his hope that he didn’t hurt her when she tripped him in the dining room; and then on his way to looking down at her leg and foot again, pauses momentarily but very definitely, on her décolletage. Then he looks back up at her again. There is no dialogue to distract the viewer from what Charles is looking at.

Oddly, no censors objected to this very suggestive shot; instead they focused on what ensued. Ohio, Kansas, and Maryland joined Pennsylvania in demanding the elimination of what the last described as the “semi close-up view where [Charles] allows his eyes to pass up and down over her.” This was a quick POV series of shots in which (1) Charles struggles to look at Jean; (2) Jean appears blurry and asks Charles if he’s all right; and (3) Charles, after swallowing, struggles to reply in the affirmative.

Charles is so “cockeyed” from Jean’s perfume that when they eventually stand up, he can make only the weakest attempt to kiss her, which Jean easily repulses. To the censors, however, the combination of close shot scale, physical intimacy, and intoxication (even from perfume) was intolerable–too expressive of Charles’ rising desire. I suspect they actually conflated the lengthy take and the medium close-ups (no “looking over” occurs in the point of view sequence). In any case, censors had seldom seen such “looking over” shots since the early 1930s.

In addition, all four offended states were roused by the famous chaise longue scene. As Charles tries to apologize for scaring Jean with his snake Emma, she holds him close, runs her hands through his hair, tickles his ear, and breathes heavily in his face. Taking the key elements of the shoe-replacement business to another level, the erotic hilarity of this scene arises from the complete power of Jean’s spell over Charles and their sheer proximity, in two long takes (one lasting 36 seconds, and then a closer, three-minute and fourteen-second shot). During all this time, Jean won’t let Charles kiss her, but their faces are close together and their lips are never far apart. For some censors, the most provocative elements of the scene resided in the dialogue that begins with Charles’s fall to the ground ands run through his “accompanying indecent action” (Pennsylvania again) of pulling down Jean’s skirt.

Pennsylvania also cut Jean’s sigh of anticipatory orgasmic release after describing her first encounter with her future husband: “And the night will be heavy with perfume and I’ll hear a step behind me and somebody breathing heavily and then – Ohhhhh!”

Ohio originally wanted the entire scene deleted, starting with Jean’s command “Oh, come over here and sit down beside me” through their final exchange:

Jean: Oh, you’d better go to bed, Hopsy. I think I can sleep peacefully now.

Charles (adjusting his bow tie): Well, I wish I could say the same.

Jean: Why, Hopsy!

Industry representatives negotiated with the Ohio and Pennsylvania boards to try to reduce their demands; Pennsylvania was unmoved, but Ohio was persuaded to let all but their final exchange remain in the film. An outraged San Antonio Amusement Inspector articulated the boards’ thinking when she cut what she called the film’s two “prolonged scenes of passion” in Jean’s stateroom. These, she pointed out to Breen, violated Section 2 of the Code, about “suggestive postures and gestures” and seduction being used for comedy. So in San Antonio, as in Pennsylvania and Kansas, viewers missed the bulk of two of the most celebrated comic scenes in American film history.

With The Lady Eve, Breen’s instincts were generally astute. He had advised against Sir Alfred’s sketch of the Handsome Harry plot. He had eliminated the overt sex affair scene in Jean’s cabin. Yet he missed many elements as well. Besides those stateroom scenes cut by state and city censors, there were ostensibly innocent lines. As Charles searched for a new pair of shoes, Jean says, “See anything you like?” and leans back with a bare midriff.

The constantly repeated phrase “been up the Amazon for a year” references Charles’s extended sexual privation and naivete, which make him susceptible to Jean’s wiles. But the phrase can also be taken as evoking female anatomy itself. The neglect of these details resulted from Breen’s increasing tolerance and his equally increasing tiredness. We’re lucky he left them in.

Upping the ante

The negotiations over The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek followed the pattern set by The Lady Eve. The writer-director proposed increasingly outlandish scenarios; Geoffrey Shurlock and Breen again demanded an increasinglyu longer list of changes across a longer series of letters. Sturges alternately made cuts or assured them he could handle the material.

Once more, certain moments wound up offending local censors. For The Palm Beach Story, released in late 1942, only New York and Kansas passed the film without eliminations. Elsewhere, many of the suggestive elements that Shurlock had criticized were cut. One was Gerry’s line—describing how Tom sees her after many years of marriage–as “just something to snuggle up to and keep you warm at night, like a blanket” (Pennsylvania). Another was the first vertebrae-kissing scene in which a very drunk Tom breaks down a very drunk Gerry’s resistance to having sex.

Other deletions concerned details that had escaped Shurlock’s notice: Pennsylvania removed the underlined portion of Gerry’s explanation to Tom, after the Wienie King’s visit and munificence, of “the look” women get from men: “From the time you’re about so big, and wondering why your girl friends’ fathers are getting so arch all of a sudden – nothing wrong – just an overture to the opera that’s coming.” Even after many changes to her dialogue, scenes with Princess Centimilia could have provoked bans or major cuts. After all, she is followed around by her gigolo Toto (Sig Arno) and (in an ironic adherence to the Code’s demands) marries purely to legitimize her sexual impulses. Yet in part because of Mary Astor’s frantic line delivery, her scenes were retained. Overall, relative to its many potential offenses, The Palm Beach Story faced surprisingly minimal objections.

The entire premise of Miracle and the ensuing action mock the notion of marriage’s sanctity from multiple angles. Breen, the American military, and the Legion of Decency examined the film minutely before it was issued a seal, and many changes were made. For this reason, only one state board (Kansas) cut one line of dialogue: Trudy’s comment that “Some sort of fun lasts longer than others.”

Still, there was much to offend audiences and censors in the completed film. For example, the MPPDA and Sturges received numerous letters of complaint linking the film to the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. One viewer in Minneapolis wrote that the film showed it to be “a subject for slapstick and high comedy, especially if the delinquent is unusually fruitful. . . . My boy thought she must have passed the night with 6 soldiers or sailors. . . . In Hollywood I understand you can get away with despoiling young girls and morals don’t exist except for yokels. Do you have to spread that poison?” Given the growing panic over what was seen as a national JD epidemic, Paramount’s delay in distributing Miracle—it was completed in Spring 1943 but released in January 1944—exacerbated the controversy.