Archive for the 'Independent American film' Category

New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking

La La Land.

DB here:

Between the end of principal photography on First Man and the start of post-production, Damien Chazelle squeezed in a visit to the UW–Madison. We’re very glad he did. A hell of a time was had by all.

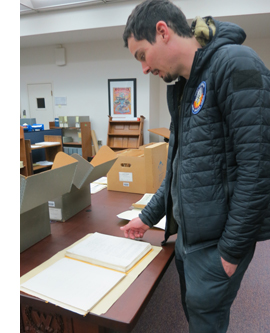

His visit culminated a Cinematheque series devoted to his work. On Friday 23 February we picked him up at O’H are and had a fine ride back talking about film and less important things. Then he visited our archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; on the right, he examines an original Final Revised script of Citizen Kane.

are and had a fine ride back talking about film and less important things. Then he visited our archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; on the right, he examines an original Final Revised script of Citizen Kane.

After that, he sat down for a conversation about his career with a hundred or so students. At a quick dinner, he and our Cinematheque impresario Jim Healy gave dueling impersonations of Michael Gazzo as Frankie Pentangeli. Damien then plunged into a long Q & A with a full house who had just seen La La Land in 35mm.

Next morning he met with Criterionistas Kim Hendrickson and Grant Delin for a FilmStruck segment. Then, in a discussion with Kelley Conway, he introduced a string of films he curated for the Cinematheque. But he wasn’t off the hook, because driving back to O’Hare with Kelley and Jeff Smith, he was immersed in more film talk.

Damien proved himself the ultimate guest—friendly and generous, enthusiastic and excited, free of airs and snark. We learned a lot from him. Herewith, a sample.

A Direct-Cinema musical

Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench.

Although he considered a musical career, film was Damien’s first love. He wrote scripts in middle school, transcribed movie dialogue from VHS tapes, and as an undergrad watched films in Harvard’s magnificent archive. The film program there, with leaders like Alfred Guzzetti and Ross McAlwee, stressed documentary and experimental film, and the exposure stuck. Among the films Damien curated for our Cinematheque show were the Rouch-Morin investigation Chronicle of a Summer and Su Friedrich’s Sink or Swim.

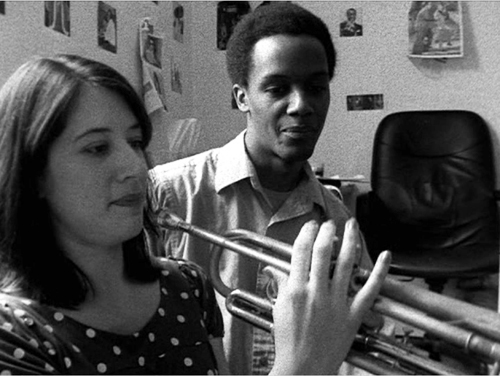

No surprise, then, that his first feature, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, was shot in a Direct Cinema mode. It’s got light leaks and run-and-gun footage, complete with bumpy handheld pans and zooms. To get around problems of inexperienced actors, Damien told some of them that it was a documentary. The 16mm project was produced over three years; sometimes the exposed films sat in the lab while Damien drummed up donations from friends, family, and strangers. (Writing blind to Harvard alums, Damien got a donation from John Lithgow.) When a processing accident ruined some footage, Damien’s producer talked the lab into free work for a time.

Guy and Madeline cuts among three characters: trumpeter Guy, his ex-girlfriend Madeline, and his new girlfriend Ilena. Like a Nouvelle Vague film, it relies on chance encounters. Madeline is emotionally wrenched by the breakup with Guy, and we follow her efforts to find work and a new partner. Ilena’s semi-reluctant meeting with an older man who brings her home to meet his daughter reminded me of the moment in Shoot the Piano Player when Charlie, running from the thugs, falls into step beside a stranger who tells him his own troubles. And of course the title characters recall the separated lovers of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

For all its documentary textures, the film at times becomes what J. Hoberman called a Mumblecore musical. But there’s a gradual shift to the full-blown show-biz mode. Damien talked of the thrilling moment in Hollywood musicals when realistic presentation of a scene gives way to nondiegetic music and the characters leap to a new, more ethereal level. Guy and Madeline presents this transition in gradual doses.

At first, the numbers are motivated realistically. Guy, an African American, plays trumpet with a jazz ensemble, so we get scenes of their performance at a local hangout. We move a bit further toward stylization with a party sequence that induces some talented kids to indulge in singing and tap-dancing among their friends—captured in casually imperfect framings.

The transition to pure musical fantasy comes forward after the breakup in a solo number, with Madeline singing a soliloquy as she wanders in the park. There’s no sense of an audience; this is a private reverie. (A whiff of this tune, heard on a car radio, makes its way into La La Land‘s opening shot.)

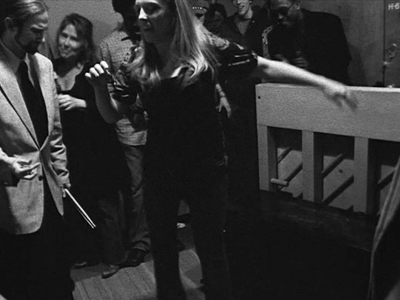

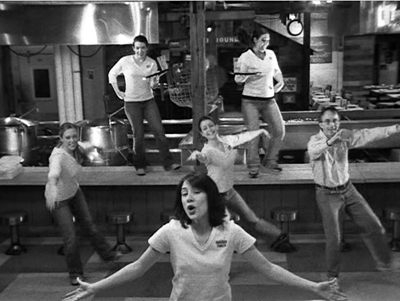

When Madeline takes up work at a diner, the components come together in an all-out production number addressed to us.

In an echo of Bande à part’s “Madison” sequence (lucky name), shooting a dance number in cinéma-vérité mode brings out an intriguing friction. It’s the same kind of productive clash we get on the soundtrack, between Justin Hurwitz’s shimmering Legrand-inflected score and varieties of jazz (Dixieland, Guy’s cool composition for Madeline). And like Nouvelle Vague characters, these people are devoted to books, the arts, and self-exploration.

As a “staged documentary” Chazelle’s film parallels Chronicle of a Summer in an intriguing way. That film starts as pure Direct Cinema, with investigators stopping people on the street to ask them questions. But as we get to know the group the film concentrates on, there’s a lot more control and “fictionalization.” There are precise matches on action, for instance, with camera ubiquity indicating careful restaging.

This rigging doesn’t damage the film as a document of summer 1960. Damien learned from it that you can make a truthful movie by “creating a situation with less and less acting to do.” Given this hybrid quality, Chronicle of a Summer becomes a vivid example of a moment when a film mode is “figuring itself out.” Its self-conscious artifice, which includes participants watching themselves during a screening, was foundational for the New Wave. “You watch a language being born.” That language was also political, as Damien pointed out: The film summons up memories of the Holocaust and glimpses of the Algerian war.

In other respects, Damien’s first film looks forward to La La Land thematically and formally. Guy and Madeline starts with the moment of the couple’s breakup (on the bench) and flashes back to vignettes of their love affair before returning to the bench. This opening loop is like the one that jumps from Mia’s night out back to the traffic jam and then follows Sebastian. A large stretch of each film’s plot is about how the couple’s lives converge and diverge.

Similarly, when the signature tune “I Left My Heart in Cincinnati” is played, shots of Madeline and Guy frame a flashback to the combo’s earlier performance, as if they’re sharing the memory. Something similar happens at the climax of La La Land, in what seems to be a mutual vision of Sebastian and Mia’s alternative future. As often happens in Chazelle’s cinema, epiphanies burst out in moments of musical performance.

Blood, sweat, and tears on the drumhead

Grand Piano.

Despite playing many festivals and winning critical praise, Guy and Madeline didn’t open any doors in Hollywood. Damien picked up odd jobs, not all film-related, while writing commercial genre screenplays. He sold a kidnapping script (not made) and Grand Piano (2013), skillfully directed by Eugenio Mira. He began getting assignments like The Last Exorcism Part II (2013) and he contributed to the screenplay for what became 10 Cloverfield Lane (2017), released long after he’d worked on it.

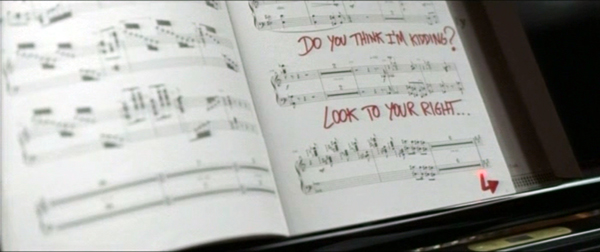

I found Grand Piano pretty impressive on the big screen. Chazelle’s script and Mira’s direction create a solid thriller built around the situation Hitchcock designed for his versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much. Most of the action takes place during a concert celebrating the return of a traumatized pianist to the stage. As he’s about to start the program, a sniper uses cellphone messages and scribbles on the score to demand a perfect performance of the florid piece that spooked the pianist years before.

At first restricted to the pianist, the film’s viewpoint widens gradually to include others, and soon crosscutting builds tension. The tormenting voice (“Play one wrong note and you die”) calls to mind the music teacher in Whiplash. As in a classic thriller, the climax arrives when the victim must fight back. And as in Whiplash, the performer wins using the only weapon he has: nearly crazed virtuosity.

Damien now thinks that the long germination of the scripts for Whiplash and La La Land made them better. As financing kept falling through, the films gained more layers. Whiplash (2014) found a home first, with Blumhouse producing and helping with the financing. It was their idea to shoot a scene to show investors (we screened it in our series), and the project found financing at Bold Films.

Given a $3 million budget and a 20-day schedule, Whiplash demanded meticulous storyboarding and very little coverage. Like Hitchcock and Leone, Damien shot only what he needed. He used two cameras for the rehearsal scenes and three for the climactic concert. The cuts and camera moves were planned to coincide with measures of the music.

Damien calls Whiplash a film about music (the same could apply to Grand Piano). It owes a lot to the sports-film genre as well; Damien envisioned its punishing force as indebted to Raging Bull. He turns big-band drumming into blunt-force trauma, with gory drumheads and cymbals. Sam Fuller would have approved.

Like Guy and Madeline and Grand Piano, Whiplash culminates in a musical performance that carries a powerful emotional impact. No wonder that as a kid Chazelle studied one-reel movies of classic drummers, then started to think of the shorts as films in their own right. In this spirit he curated for us two Dudley Murphy shorts, St. Louis Blues (1929, with Bessie Smith) and Black & Tan (1929, with Duke Ellington), along with the 1954 documentary Jazz Dance, a night on the town that explodes with pure human happiness. In all these, music-making is pushed to the edge of ecstasy.

This time around with Whiplash (good name for a movie about sadomasochistic musicians), I noticed its straightforward classical construction. Damien says that he learned screenplay construction after moving to LA. Its tale of a boy caught between a good but weak father and a punishing, strong one gains strength and sharpness from its traditional four-part plot.

At the crucial 25-minute mark, Fletcher wins Andrew’s trust. Four minutes later, in the performance of “Whiplash,” Fletcher is bellowing and Andrew is sobbing. First reversal noted. The second part, the Complicating Action, interweaves Andrew’s romance with Nicole, his persistence in drumming, and his fraught relation with his family. This part culminates at the midpoint with Fletcher’s giving Andrew a new rival, which impels Andrew to break up with Nicole. In the Development section, Andrew suffers more setbacks. A harrowing car accident leads him to botch a major competition and assault Fletcher. He leaves school, accuses Fletcher of abuse, and abandons drumming.

After he discovers Fletcher playing piano in a club, he agrees to join his new combo, which preciptates the climax: a competition performance at which Andrew, realizing that Fletcher is out for revenge, seizes control. The result is another burst of barely controlled frenzy, complete with unmotivated bursts of light spattering Andrew in the last shot.

Whiplash is a film without pity. Andrew’s rejection of Nicole suggests that he’s become obsessive, and after his scuffle with Fletcher he’s drained and numb. And no sympathy is extended to the monstrous Fletcher. Damien avoided what he called the “rubber ducky” moment that shows this man to be damaged by some childhood trauma. We get no explanation of his ruthless brutality; he’s simply a force to be fled or fought. (Damien told us that he modeled Fletcher on a music teacher he’d had; the original probably wasn’t as nasty, but Damien wanted the film to convey how frightening he was to a fifteen-year-old.)

At the end, Andrew earns a glint of triumph, but the reverse shot shrewdly withholds from us the expression that might warm us up to this man. His sliced-off smile and slight nod are all it takes for Andrew to react.

Still, his grudging approval means that Andrew has won over one scary dad.

Embarrassing yourself and your characters

At 29, Chazelle found himself with a hit, confirming the Magic Number 30 Rule. Whiplash made a splash at the Sundance Film Festival and went on to be nominated for several Oscars, winning three. It also brought in a lot more than its cost. Damien could now reignite La La Land.

Lionsgate, via Summit, picked it up and production began. There were 40 days of shooting across 65 locations. The production was able to be so efficient because of careful planning and the reliance on long takes. “The long take has become fashionable,” Damien says, who knows his film history: “But it’s actually the most old-fashioned kind of thing.” Whiplash is an editing-driven movie, but La La Land relies on many fewer shots. The moments of shot/reverse shot–notably in the spoiled dinner when Sebastian is briefly between tour gigs–gain a prominence they don’t have in most movies.

In shooting, the morning was given over to rehearsals, followed by a great many takes–often required to sync the actors to playback. Around about take twelve, Damien recalls, things started to crystallize, but sometimes as many as twenty takes were needed. While Whiplash stayed tight to the screenplay, La La Land was heavily improvised. The visuals were pre-designed, but the relationship at the center needed a casual feel, as if the characters were tossing off their lines.

Damien had thought he would simply be able to cut together the “one-ers,” but editing took five months, not least because he and his long-time editor Tom Cross played with many versions. Every number was a candidate for deletion, including the freeway opening. (Yeah, I shuddered.) There was also some digital adjustment of the 35mm original. David Koepp wrote me:

Maybe ask Chazelle about how beautifully he used color to direct our eye in his LA LA LAND opening. Always the right burst of costume color directing us to the right spot at the right time… although I guess that’s more of a compliment than a question.

Damien explained that he made those colors pop a bit more by digitally toning down other costumes in that intricate opening sequence.

La La Land has steadily grown in my regard and affection; I think it’s one of the best recent American movies. Just the title gets you going. “La la” suggests music, but also the self-absorption of jamming your ears lalalala. LA is a town of airheads, but it can become a town of worthwhile fantasy too. Damien spoke of most movies trying to make fake sets look real; he wanted to “take real stuff and make it look false.”

This time around, I was struck by the film’s harsh side. It’s pretty hard on mainstream Hollywood, from the smug partygoer who says he’s really good at world-building to Mia’s superficial roommates. Their anthem “Someone in the Crowd” is about careerism, but it becomes for her about the search for a soulmate.

Then there’s Sebastian. A lot of Hollywood plots work only if the guy is a jerk. In Whiplash, Andrew turns smug when he thinks he’s Fletcher’s pet, and he dumps Nicole heartlessly. (He’s becoming a bit like Fletcher.) In La La Land, I began to see Sebastian as a stubborn nerd, refusing to play the cocktail-bar set list and ranting about jazz to anyone who’ll listen. Ryan Gosling’s ingratiating performance makes this nerd more likable, but as written the character is pretty arrogant.

One scene that puzzled me now makes sense in a larger pattern of Seb’s obtuse, evasive behavior. After he learns he may be kept from attending Mia’s show, why doesn’t he phone her? We see him brooding outside the music studio.

He may think he can still make it in time, which would reflect his somewhat risky self-assurance. But Damien pointed out that elsewhere in the film he’s not seen using a cellphone, or for that matter a computer. Old school as he is, he seems wary of modern technology. He drives an utterly impractical Buick convertible. He plays cassette tapes and LPs and his apartment’s phone is an old-style handset, antenna and all. An omitted screenplay scene showed him in a movie audience ranting at somebody using a phone, thereby disturbing the viewers more than the caller has.

I’m being too hard on Sebastian, of course. We admire his idealism, his tenacity, and his romantic attachment to what he thinks is the best of the past. Still, Damien has remarked that he sees sides of himself in both Andrew and Sebastian, which reminds us that “commercial” films can also be personal ones. For him, the strongest creative choices risk exposing you. “If you’re not embarrassing yourself, you’re not doing your job.”

If Sebastian is too willful, Mia is too eager and desperate. “I can do it differently,” she tells the audition staff after they’ve brushed her off. Sebastian and Mia complement each other. His cockiness (“Fuck ’em”) pushes her to mount her one-woman show, while she tries to steer him back to his basic commitments. The larger theme seems to me that the most vital art comes from yourself, be it your memory of a Francophile aunt or your irrational attachment to classic jazz. Instead of having to fit into prefab TV characters, Mia gets her breakout role in a film that will build its script around her personality.

Damien spoke of the musical as Hollywood’s most avant-garde genre. That partly stems from the transition from realism to fantasy that launches a number. This shift provides the film’s final turning point, with Mia’s audition; for once a Chazelle film makes its musical climax a subdued one, but it’s no less a demonstration of the performer’s authentic emotion. Art’s power comes from novelty (“new colors to sing”) grounded in sincerity and self-awareness, even if by some standards it seems awkward and geekish.

The avant-garde overtones are also a matter of how musicals make real locations look unreal—as Demy films memorably show. So it was uncannily appropriate that Damien asked us to introduce La La Land with Bruce Baillie’s All My Life (1966). A slow pan left across a fence and flowers gives way to a diagonal tilt up to the sky; the whole accompanied by Ella Fitzgerald and Teddy Wilson.

La La Land might well be a sequel, as we tilt down from another blue sky to a gridlocked freeway.

As Baillie turns a prosaic bush and fence into an audiovisual flow, so the opening of Chazelle’s film takes the banality of a traffic jam and makes it an explosion of youthful hope and energy, complete with somersaults.

The sheer cinematic exuberance of La La Land will, I think, keep the film alive for a long time. “Every scene, a new idea”: Damien quoted Arnaud Desplechin quoting Truffaut. Many parts of La La Land put nifty tweaks on the conventions of comedy, drama, and the musical. There’s the “enacted” slow-mo at the party, the iris around a kiss, and the montage rendered as a flash-forward from a duet at the piano (“City of Stars”). There’s often a tweak on what might have been perfunctory filler. The exit-on-an-elevator shot is lit and costumed so as to (a) suggest the conformity of the dress code for an audition; (b) emphasize the height of her rivals; and (c) accentuate the spill on the less glamorous Mia’s blouse. Her disadvantages are diagrammed.

Then there’s the idea of having a “real” dream ballet at the planetarium and a virtual one at the end. Speaking of the end, I especially liked the head-fake at the start of the present-time part. By showing Mia on the Warners lot and Sebastian in his club, we’re invited to infer for a moment that they stayed a couple, before revealing that she’s actually married to an easygoing beefcake and Seb still lives alone.

Pitching La La Land, Damien found that many producers insisted that the couple unite for a happy ending. Damien objected that many of the great romantic films, including Casablanca, A Star Is Born, and Gone with the Wind, center on lost love. Still, he found a way to a happy ending by offering an alternative outcome that many viewers will prefer.

True, it’s sad. But Jacques Demy once remarked that sad movies make him happy. For me, La La Land is that sort of movie.

How much does cinephilia help a director? I’d expected Damien to recommend the sort of movie immersion he had as a kid. And he admitted the power of the past. “I can’t unwatch the movies I’ve seen.” But some great directors aren’t cinephiles, he granted. He cited Bresson and Dreyer; I thought of Ford. What’s important, he suggested, is a relation to some, any art form–if not film, then visual arts or theatre or literature.

Maybe the best of both worlds is to be a young filmmaker who knows both film and another medium, such as music, and thinks as an audiovisual artist. Damnien remarked that in writing he starts with images rather than words but then lets the dialogue focus the scene. Interestingly, Eisenstein taught his students to stage a scene first as if it were in a silent film, then revise it with music, color, and (only then) dialogue. That assured that pictorial storytelling would be foremost.

Kristin and I were gratified to hear that Damien has over the years read several things we’ve written. In turn, he taught us a lot. His visit reminded me that one path to filmmaking achievement is just thinking about your craft and your choices, in light of your life experiences and your encounters with powerful art. He passed that lesson along to the hundreds of people who came to learn from him.

Thanks to Damien Chazelle and Alissa Goldberg for making the visit possible. Thanks as well to J. J. Murphy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, Matt St. John, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Maria Belodubrovskaya, Erik Gunneson, Jason Quist, Kim Hendrickson, and Grant Delin. Event planners Kelley Conway, Jeff Smith, and above all Jim Healy, Cinematheque Director, deserve massive gratitude as well.

We have other discussion of La La Land on this site: my search for some of its roots in 1940s innovations, and my analysis of its song plot. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation among experts Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen. Jeff Smith weighed in on the film’s score, correctly predicting its Oscar triumph.

P.S. 8 March 2018: Many thanks to Steve Elworth for a correction about All My Life.

Kelley Conway interviews Damien Chazelle.

Wisconsin Film Festival: Retro-mania

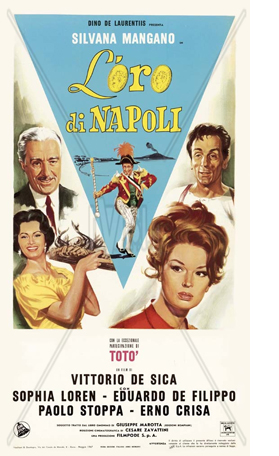

The Gold of Naples (L’oro di Napoli, 1954).

DB here:

With the growing popularity of subscription streaming services, I suspect that film festivals will need to amp up their retrospective offerings. I was very surprised that a good film like I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, which would in earlier years have played arthouses, had no theatrical release. Despite its acclaim at Sundance, it went straight to Netflix online. True, Amazon has shown great willingness to port its high-profile titles to big screens. But by and large, as Netflix, Amazon, and other services produce and buy up new films, I suspect that festival premieres of indie titles will become more and more a display case for streaming. See it this week at our festival, and next month online!

It must be dispiriting for filmmakers hoping for theatrical play. Yet this crunch may oblige festival programmers to emphasize archival and studio restorations. These rarities are unlikely to show up on streaming any time soon, and festival screenings can build a public for them—so that they may eventually come to DVD or subscription services.

Case in point: Several restored titles at our Wisconsin Film Festival drew sellout crowds.

AMPAS comes through

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

I did manage to squeeze into another Academy restoration, Howard Hughes’ Cock of the Air (1932). The film amply showcases Hughes’ two principal concerns, aviation and the female mammary glands. (I guess technically that makes three concerns.) It’s a minor-key Lubitsch switch in which priapic flyboy Chester Morris pursues sexy Billie Dove, who’s resolved to bring his ego crashing to earth. We get lots of nuzzling, murmured double entendres, and scenes of passion quickly doused by the woman’s coquettish withdrawal. I thought the plot thin, needing a romantic rival or two, but the leering pre-Code stuff is good dirty fun. The high point comes when Billie encases herself in a suit of armor and Chester arms himself with a can opener.

The direction is credited to Tom Buckingham, a lower-tier artisan, but it seems possible that parts of the film were handled by Lewis Milestone, who contributed the original story. The first couple of reels are very flashy, with odd angles, complicated tracking shots, and bursts of rhythmic editing. They’re typical of Milestone’s showy, sometimes showoffish, style in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and The Front Page (1931; also shown at WFF).

Cock of the Air encountered heavy censorship, with the can-opener episode entirely snipped from the release version. The Hays Office even provided local censor boards with guidance for further cutting. When Heather discovered a pre-censorship print at the Academy—an exciting find—she discovered that the offending footage was there, but the soundtrack portions were lost.

Heather proceeded to hire actors to voice the parts in accord with the script and the onscreen lip movements. The results are sonically smooth, but in the spirit of fair dealing, the bits of replacement are marked with a discreet bug in the lower right corner of the frame. This is a nice piece of archival integrity. Heather also showed an informative short on the restoration of this engaging piece of naughty early sound cinema.

Of incidents and non-incidents

The Incident (1967).

Two other pieces of film history got fitted into place with the revival of Larry Peerce’s One Potato, Two Potato (1964), a classic of American social-problem cinema, and the rarer The Incident (1967). This latter glimpse of mean streets creates what screenwriter David Koepp calls a Bottle, a tightly constrained space in which the drama plays out. Here the Bottle is a subway car in which several people, a cross-section of New York life, become the playthings of two young thugs, played by Tony Musante and Martin Sheen.

Starting by gay-bashing and culminating in a charged racial confrontation, the subway conflicts sought to show how the solid citizens can’t summon the will to respond collectively—even when they take their turn under the thugs’ lash. It was intended as a response to the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese, whose screams were mostly ignored by her Queens neighbors. (A recent documentary, The Witness, revisits the case.)

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

A believer in improvisation, Peerce rehearsed different groups of actors separately, then brought them together to let some natural friction emerge. He encouraged them to add to the script and build immediate reactions—so immediate that Thelma Ritter, a veteran unused to improv methods, responded to Musante’s goadings by slapping him. All this is captured in a superheated style of fast cuts, big close-ups, and screeching sound. It’s a white-knuckle ride that retains its power. I hadn’t seen it since 1970, but the violent climax, utterly earned, is disturbingly contemporary. The film’s final moments are being replayed, in reality, all over America as you read this.

The nicest surprise of my retrospective viewing was The Gold of Naples (1954). Studded with big names (Ponti and De Laurentiis, Totó and de Sica, Silvana Mangano and Sophia Loren), it has sometimes been thought to be one of those lightweight Italian comedies that represent a quiet refusal of the Neorealist impulse. On the contrary, it proves to be a bold contribution to block construction, here in the omnibus genre. Several stories are laid end to end, exemplifying the vivacity and poignancy of life in Naples’ back alleys.

One story has a tight, shocking arc: the tale of a prostitute (Mangano) who thinks she’s marrying for love until she learns her new husband’s guilt-ridden sadomasochistic motives. The finale is a scrappy anecdote, in which The People give a local plutocrat the ultimate vocalization of disrespect.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

Above all, in an episode cut from the original American release (and missing from this poster, though at the top of today’s entry), a mother follows her son’s coffin driven through the street. She throws wrapped candies for children to pick up. That’s it. No flashbacks to life with her boy, no dialogue telling us how he died, no colorful secondary characters to provide that life-goes-on final note. It could be called “The Incident,” though nothing more unlike the fever-pitch drama of Larry Peerce’s film could be imagined.

According to screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, a Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

The lack of a dramatic peak, to which a normal scene would build, can force our attention to downshift to the minutiae of moment-by-moment action, or rather micro-action. That’s what happens in this sequence of The Gold of Naples, which Zavattini helped write. Every gesture and glance becomes potentially, but ambiguously, significant. De Sica’s patient recording of a very thin slice of life is as radiantly unpretentious a model of “pure Neorealism” as anything to come from the 1940s.

This is just a glimpse of the delights among the 150 screenings that are gracing our eight-day film festival. (We’re now the largest university-sponsored festival in the country, though probably not in budget.) Details of this magnificently programmed affair are here. We’ll blog again soon.

Thanks to the programmers Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King, along with all the institutions, wise elders, community supporters, and volunteers that make WFF fun. You can browse earlier reportage from this event here.

You can also see the restored Front Page (1931) in Criterion’s new His Girl Friday DVD release. On Cock of the Air’s censorship travails, see the AFI site. It will be screened very soon at the TCM Festival. Also set for the TCM festival is The Incident, which will screen later in April at Film Forum. Mike Mashon gives more information on Aloha Wanderwell in his LoC blog.

How wrong I was to miss booking The Gold of Naples when I ran a film club in college and good old Audio-Brandon offered it. Even without the funeral scene and the up-yours finale, it would be worth seeing. Now no version seems available in the US; WFF director Jim Healy brought a print from Italy. It would be perfect for FilmStruck.

Read…watch movie…grab food…read…watch movie…

Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop

Ant-Man 2: This time it’s personal. Not that it wasn’t before. But now it’s personal and expensive.

DB here:

Sean Parker, the Napster founder who taught everybody that digital piracy means never having to say you’re sorry, has come up with a new killer app. Called The Screening Room, the pitch is catching the eye of an industry that thrives on finding new niches for its product.

Stuff you probably already know

Recall, as background, that Hollywood’s economic model depends on two conditions.

(1) Strong Intellectual Property measures, both technological and legal. (Intellectual is to be taken in a broad sense here. It includes Paul Blart movies.) Encryption is designed to protect DVDs, streaming, and the Digital Cinema Package that plays in your local multiplex. Law enforcement, under the auspices of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, backs up anti-piracy with fines and jail time.

(2) Price discrimination. The premise of the classic vertically-integrated studio system was that people will pay more to see a movie sooner than other people. Why this is true still mystifies me, but facts are facts. Hence the old system of “runs.” First-run movies demanded top dollar, then second runs were at lower prices, and subsequent runs were still cheaper. When the studios surrendered their theatre ownership, the runs system remained roughly in place, chiefly because most films were platform released, playing the big cities before gradually expanding to the provinces. And network TV was basically the only ancillary market. But wide releases–hundreds or even thousands of copies playing everywhere–became the industry norm as cable, home video, and other technologies came along. The run system was reborn, and price discrimination became much more fine-grained.

Known, confusingly, as “windows,” phases of the film’s life are assigned to various platforms. After the theatrical window, typically 90 days after release, there are windows for airline/hotel access, disc (DVD, Blu-ray), Pay-per-View, streaming, cable, and on down the line. The order of these windows for any one title can vary somewhat, depending on negotiations. Most of them are designed to define price points scaled along a curve: how much it’s worth to somebody to see the movie at intervals after the initial theatrical release. By the time a movie comes to free cable, you’ve pretty much squeezed everything out of it, though the industry relies very extensively on worldwide cable purchases.

The studios depend on the theatrical release, but not because it’s the biggest source of revenue. (For the top films it can yield a lot, of course, but most films don’t recoup their costs in that window.) The theatrical release builds awareness, making it stand out downstream in the ancillaries. Without theatrical release, a film needs a lot of publicity to draw notice. Witness all those films on your Netflix or Hulu menu, all those John Cusack movies you didn’t know existed.

Independent films are increasingly relying on day-and-date release between a mild theatrical run and some form of Video on Demand. Other indie titles, along with foreign ones, are going wholly VOD, and the big players–Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon–are vigorously buying titles and backing new projects against the looming day when the studios will license fewer blockbusters to them.

The studios need the theatre chains as a shop window for their top-tier product. The theatre chains obviously need the studios to keep crowds flowing in. But some parties have flirted with day-and-date theatrical/VOD. Most famously Ted Sarandos of Netflix argued for it in 2013, then had to backtrack a few days later. On the studio end, Universal in 2011 proposed softening the theatrical window by offering Tower Heist on “premium VOD.” The plan was to drastically cut into the theatrical window by making the film available after three weeks of release, for the hefty price of $59.95. Theatre owners threatened to boycott the film, and filmmakers howled in protest. Many feared that it was the thin edge of a wedge that would eventually, through price wars, shorten windows and lower prices–not to mention wreck theatre attendance. The idea was quickly dropped.

No bad idea ever goes away, as we learn from claims that tax cuts create jobs and that we’re just one intervention away from creating peace in the world. Thanks to Parker, we now have Premium VOD in a new guise. That means a new window, with corresponding price discrimination.

Premium VOD, steroidal

Last week, The Screening Room project, sponsored by Parker and entrepreneur Prem Akkaraju, was made public. Brent Lang of Variety outlined the plan circulating among the major players.

Individuals briefed on the plan said Screening Room would charge about $150 for access to the set-top box that transmits the movies and charge $50 per view. Consumers have a 48-hour window to view the film.

To get exhibitors on board, the company proposes cutting them in on a significant percentage of the revenue, as much as $20 of the fee. As an added incentive to theater owners, Screening Room is also offering customers who pay the $50 two free tickets to see the movie at a cinema of their choice. That way, exhibitors would get the added benefit of profiting from concession sales to those moviegoers.

Participating distributors would also get a cut of the $50-per-view proceeds, also believed to be 20%, before Screening Room took its own fee of 10%.

Parker assures all stakeholders that the magic box would assure maximum antipiracy controls.

Since then, developments have been swift. Peter Jackson, Ron Howard, and J.J. Abrams are supporting the plan, while James Cameron is opposing it. The Cinemark and Regal chains, at this point the biggest theatre chains in the country, are against it, but there are hints that AMC, soon to be the biggest chain in the world if it’s allowed to purchase Carmike, might be interested. As for studios, Universal, Sony, and Fox are rumored to be considering the prospect. Once the give-and-take of dealmaking gets under way, there’s no telling what a final arrangement might look like.

What’s transparently clear is the opposition of the art-house sector. Tim League of Alamo Drafthouse issued the first warning on Monday, calling The Screening Room a “half-baked” idea. Today the Art House Convergence, an association of 600 theatres, issued a severe criticism of Parker’s plan. The open letter has been summarized in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. Indiewire has published it in its entirety, and I do the same, as follows.

The Art House Convergence, a specialty cinema organization representing 600 theaters and allied cinema exhibition businesses, strongly opposes Screening Room, the start-up backed by Napster co-founder Sean Parker and Prem Akkaraju. The proposed model is incongruous with the movie exhibition sector by devaluing the in-theater experience and enabling increased piracy. Furthermore, we seriously question the economics of the proposed revenue-sharing model.

We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model, nor are we arguing for the decrease in home entertainment availability for customers – most independent theaters already play alongside VOD and Premium VOD, and as exhibitors, we are acutely aware of patrons who stay home to watch films instead of coming out to our theaters.

Rather, we are focused on the impact this particular model will have on the cinema market as a whole. We strongly believe if the studios, distributors, and major chains adopt this model, we will see a wildfire spread of pirated content, and consequently, a decline in overall film profitability through the cannibalization of theatrical revenue. The theatrical experience is unique and beneficial to maximizing profit for films. A theatrical release contributes to healthy ancillary revenue generation and thus cinema grosses must be protected from the potential erosion effect of piracy.

The exhibition community was required to subscribe to DCI-compliance in a very material way – either by financing through VPF integrators (and those contracts have not yet expired) or by turning to other models which necessitated substantial time and commitment. Those exhibitors who were unable to make the transition were punished by a loss of product. The digital conversion had a substantial cost per theater, upwards of $100,000 per screen, all in the name of piracy eradication and lowering print, storage and delivery costs to benefit the distributors. How will Screening Room prevent piracy? If studios are concerned enough with projectionists and patrons videotaping a film in theaters that they provide security with night-vision goggles for premieres and opening weekends, how do they reason that an at-home viewer won’t set up a $40 HD camera and capture a near-pristine version of the film for immediate upload to torrent sites?

This proposed model would negate DCI-compliance by making first-run titles available to anyone with the set-top device for an incredibly low fee – how will Screening Room prevent the sale of these devices to an apartment complex, a bar owner, or any other individual or company interested in creating their own pop-up exhibition space? We must consider how the existing structures for exhibition will be affected or enforced, including rights fees, VPFs and box office percentages.

A model like this will also have a local economic impact by encouraging traditional moviegoers to stay home, reducing in-theater revenue and making high-quality pirated content readily available. This loss of revenue through box office decline and piracy will result in a loss of jobs, both entry level and long-term, from part time concessions and ticket-takers to full time projectionists and programmers, and will negatively impact local establishments in the restaurant industry and other nearby businesses. How many of today’s filmmakers started their careers at their local moviehouse?

There are many unanswered questions as to how this business model will actually work. The proposed model, as we have read in countless articles, suggests exhibitors will receive $20 for each film purchased. At first glance, an exhibitor may think it represents a small, but potentially steady, additional revenue stream. But how will this actually be divided among the number of theaters playing the purchased title; will exhibitors who open the title receive more than an exhibitor who does not get the title until several weeks later (based on a distributor’s decision); who will audit the revenue to ensure exhibitors are being paid fairly; does this revenue come from Screening Room or from the distributor… these are just a few of the issues yet to be explained.

Similarly, Screening Room promises to give each subscriber two free cinema tickets with each film purchase. Yet to be disclosed is how an exhibitor will recoup the value of those tickets from Screening Room so they can then pay the percentage of box office revenue owed to the distributor of the film. Yet to be explained is who will manage the ticket program details such as location choice, method of purchase, and so on. Will all exhibitors be expected to honor Screening Room free tickets, or will some exhibitors receive preferential treatment over others?

We strongly urge the studios, filmmakers, and exhibitors to truly consider the impact this model could have on the exhibition industry. We as the Art House and independent community have serious concerns regarding the security of an at-home set-top box system as well as the transparency and effectiveness of the revenue-sharing model. Our exhibition sector has always welcomed innovation, disruption and forward-thinking ideas, most especially onscreen through independent film; however, we do not see Screening Room as innovative or forward-thinking in our favor, rather we see it as inviting piracy and significantly decreasing the overall profitability of film releases.

At this time and with the information available to us we strongly encourage all studios to deny all content to this service.

One point of clarification. Some reports have interpreted the paragraph beginning “We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model…” as meaning that art-house programmers, managers, and owners are okay with day-and-date VOD. But many Art Housers wish that day-and-date VOD had been strangled in its cradle. For those people, “not debating” doesn’t mean “accepting” or “not disputing.” It means that this is not the occasion for taking issue with that feature of the concept, as the Parker proposal introduces serious problems of its own.

The churn around this proposal is turbulent; stories kept popping up as I was writing the entry. A useful update is here. To keep up to speed, you may want to visit these two summative links, one for Variety and the other for The Hollywood Reporter.

There were, and are, still second-run movie houses. To my joy, Ant-Man, released last summer, has been playing for at least seven months at our second-run house here in Madison. And in 35! Is this a record in modern times? Also, too: My Ant-Man image up top comes from the first film, not the sequel, which doesn’t yet exist. I was just fooling and pretending.

What’s the Art House Convergence? Visit their site here. My visit to their annual confab is recorded here. An updated version is available in Pandora’s Digital Box.

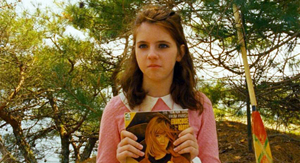

MOONRISE KINGDOM: Wes in Wonderland

DB here:

“An auteur is not a brand,” argues Richard Brody. Not always, I’d suggest; but it can happen. And it’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Wes Anderson has found a way to make films that project a unique sensibility while also fitting fairly smoothly into the modern American industry. He has his detractors (“I detest these films,” a friend tells me), but there’s no arguing with his distinctiveness. The Grand Budapest Hotel is perhaps the most vivid example of Andersonian whimsy as signature style.

In any case, before summer’s end I want to look at the auteurish aspects of another Anderson film. Whether you admire him, abominate him, or have mixed feelings, I think that studying this film can show us some interesting things about authorship in today’s film culture.

Toy worlds

When I’m making a movie, what I have in mind, first for the visuals, is how we can stage the scenes to bring them more to life in the most interesting way, and then how we can make a world for the story that the audience hasn’t quite been in before.

A film auteur is often described as having a characteristic tone, an attitude, and recurring themes. But we also find more tangible marks of authorship. One is a tendency to create distinctive story worlds. Hawks gives us milieus filled with stoic, sometimes grimly resigned professionals. Scorsese presents manic, sometimes vicious worlds that encourage his protagonists to go too far.

If the auteur’s story world is the what, plot patterning and cinematic narration give us the how. How are the actions arranged to create an arc of engagement? How are the events rendered in film style—the texture of images and sounds?

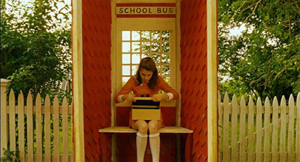

It seems clear that no auteur can be absolutely unique; each one works with norms and conventions given by tradition. For instance, a great many US independent films subscribe to the Hollywood convention of the goal-driven protagonist. Moonrise Kingdom accepts it too: Sam and Suzy want to be together, and their aims propel the action. Anderson and co-screenwriter Roman Coppola even give us the classic formula of lovers, kept apart by society, who escape to freedom in the wilderness. Likewise, the film maintains the convention of multiple lines of action: it creates parallels between the idealistic Suzy-Sam romance and the pallid routine of her parents’ marriage, as well as the hint of emerging affection between the phone operator Becky and Scoutmaster Ward.

Like a mainstream film, Moonrise Kingdom is at pains to build the plot toward a crisis—the second elopement of the couple and the massive storm that hits the region. The film turns the storm into a deadline: It will hit, says Bob Balaban’s narrator, “in three days’ time.” And as in a classical Hollywood film, the couple’s problems are solved and we get an epilogue showing their happy, if somewhat covert union.

Anderson has absorbed some lessons from mainstream cinema in more specific ways, I think. Since the Star Wars series (1977-on), we’ve seen Hollywood ever more eager to try “world-making”—adapting the traditions of fantasy, science-fiction, and comic books to creating fairly separate realms governed by their own rules. Batman and Superman adaptations of the 1980s and after followed this line, with Lord of the Rings proving that world-making could sustain long-running franchises (Harry Potter, the Marvel universe).

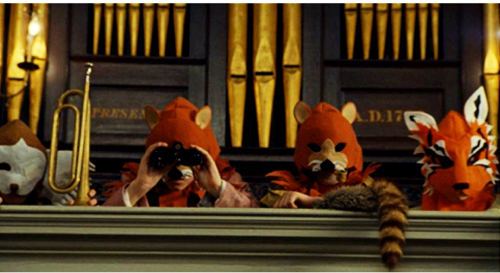

Anderson follows Lucas in creating his own worlds, but outside the conventions of space opera. We can find more or less parallel worlds in The Royal Tennenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, but Moonrise Kingdom may be the most elaborate example. It takes place in terra incognita, a cluster of imaginary islands presumably on the upper Atlantic coast. The name of the primary island, “New Penzance,” reminds us of the fantasy-worlds of Gilbert and Sullivan. There are make-believe Amerindians (Chickchaws) and the Khaki Scouts are parallel to the Boy Scouts, with Accomplishment Buttons instead of Merit Badges. The Scout regalia are given us in the sort of fussy detail that Anderson has long enjoyed.

Parts of the story are relayed by a gnome-like Narrator whose range of knowledge includes past, present, and future. He suggests a fairy-tale wizard or bard. An ancillary film tells us that he’s the librarian of New Penzance—the tribal chronicler as small-town administrator. (The existence of this short film serves to reinforce the pretense that New Penzance exists.) Then there are the young-adult books that Suzy carries with her. They’re fictitious but they get strongly tagged to aspects of the action. The books and the scouting gear take on the same solidity as retro details like Suzy’s battery-powered phonograph and Sam’s jar of Tang: 1965 stuff is recruited to flesh out Anderson’s miniature world.

Suzy’s books remind us that New Penzance, like other Anderson story worlds, is redolent of childhood. The film’s opening presents a family’s home as a dollhouse filled with toys and games. Once we’ve seen the fabric pictures rushing past on the walls, the landscapes they preview retain a miniaturized quality.

Those landscapes themselves have a childish defiance of gravity, as when we’re introduced to the poles at the tidal canals and when the Scouts build their tree house improbably high. This motif of top-heaviness eventually yields a sight gag when we learn the implausible fate of Redford’s motorcycle.

Childhood is everywhere. The music we hear in the opening is Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, played by three little brothers on a phonograph and narrated by a child for one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. Throughout the film we hear grownup music designed for kids, such as bits of Bernstein’s rendition of Saint-Saens’ Carnival of the Animals.

Benjamin Britten’s music is central to the film’s soundtrack, from his juvenilia (Simple Symphony, songs from Friday Afternoons) to his later opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream and its chorus of child fairies. A performance of Britten’s church parable Noye’s Fludde is the occasion of Sam’s first encounter with Suzy, and it prophesies the devastating storm of a year later. Carrying this kid-friendly ethos further, Anderson designs his closing credits so that Sam’s voice-over can anatomize Alexandre Desplat’s score, instrument by instrument.

If Britten suggests childhood vitality, the mournful Hank Williams tunes evoke adult disappointment. They’re associated from the start with the lonely, not-overbright Captain Sharp. When Sam’s canoe odyssey is accompanied by the fantasy Williams song “Kaw-Liga,” about a wooden Indian yearning for the carved woman across the street, Anderson suggests a parallel between two lonely, yearning males, and tagging it to Sam prefigures his eventual alliance with his surrogate father.

A tradition of twee

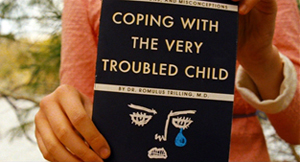

The density of this childish New Penzance, like that of other DIY cinematic worlds, supports a tendency I talked about in The Way Hollywood Tells It. For some time now, filmmakers have been filling their films with details that can be discovered on re-viewing, particularly on the DVD format, which allows us to stop and study a frame. The musical citations I just mentioned can be researched after an initial viewing, and perhaps cinephiles will notice that the therapy book’s cover is a riff on Saul Bass’s credit sequence for Bonjour Tristesse (like Françoise Hardy, a link to Left Bank pop culture).

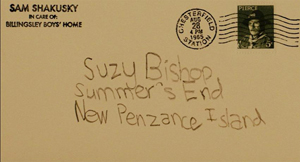

Still, on the first pass we’re unlikely to notice that the stamp on Sam’s postcard to Suzy bears the likeness of Commander Pierce.

Likewise, only after many viewings did I notice that the peculiar flaming-scissors abstraction during the skirmish in the woods is given the same design as that on the motorcycle and helmet of the despicable, and rightfully lacerated, Redford.

And in the epilogue, we might spot that Sam, having cast off his Accomplishment Buttons, has kept his mother’s pin on his new Island Police uniform.

Art and commerce again: What exec could object to loading every rift with ore when it supports ancillary sales to the fan faithful?

Some people find an inward-turned world like this to be fey, coy, twee, infantile, precious, or self-indulgent. It seems to me, though, that Anderson’s work from The Life Aquatic onward links up with a literary tradition we associate with J. M. Barrie and G. K. Chesterton. These writers employed childhood fantasy in an effort to imagine a richer, livelier realm behind prosaic reality. Another kindred spirit would be Winsor McCay, like Anderson an obsessively meticulous stylist who gives heft and lilt to dream worlds. In cinema we might recall Greenaway’s The Falls (1980), as obsessive and precious a project as can be imagined.

Indeed, why not mention the most famous figure of all? There is a trace of Lewis Carroll in Moonrise Kingdom’s looking-glass world—its strangely safe tree house, its deadpan absurdity, the habit of lawyers talking as if always in court. Like Carroll, Anderson doesn’t shrink from cruelty; the death of Snoopy is as perfunctory as that of the oysters on which the Walrus and the Carpenter tearfully dine.

Significantly, modern efforts to reenchant the world are often framed by loss. Wendy comes back from Neverland, Little Nemo awakes with a thump, Alice must return to lazy and boring afternoons. Anderson too evokes the fading of enchantment. Moonrise Kingdom takes place at the onset of autumn, and Suzy’s family lives at Summer’s End. Unlike other modern explorations of faerie, however, this one lets its characters wake up in something approximating their dream life.

Day by day, with interruptions

In accord with the child-based story world, the plot of Moonrise Kingdom provides something of a modern fairy tale. A runaway orphan who retains a token of his parentage heads out for the wilderness. A princess imprisoned in a tower scans the horizon for her rescuer. Lovers exchange messages before they escape into a realm of danger and death. They are rescued by a beneficent authority who will allow them to stay together.

Of course it’s a meta-exercise, since its authors and audiences are self-consciously deploying fairy-tale conventions. But as Barrie and Chesterton and Carroll show, enjoyment of artifice is central to art. Anderson accordingly stylizes both his plot structure and his narration.

He has long been drawn to block construction, building his plots out of big chunks that are often signaled explicitly. In Moonrise Kingdom, the chunks divide up in unusual ways—part, again, of this auteur’s cinematic signature.

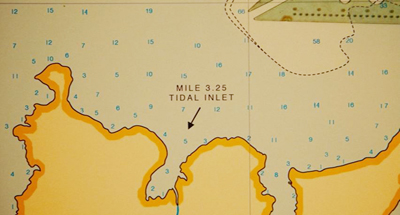

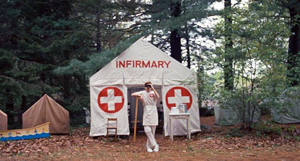

At first we might think we can just track the adventure day by day. On 2 September 1965 Sam goes AWOL from scout camp and Suzy sets out with her belongings. On 3 September the couple fend off their pursuers—the battle of arrow, BB gun, and scissors—and make camp on Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet. There they swim, dance, and spend the night. On 4 September they’re captured and separated.

But that night the scouts help them escape again, and all head for New Lebanon. The “marriage” of Sam and Suzy on the 5th leads to their flight to Saint Jack Wood Island just as the storm hits. Before they can make a lovers’ leap from the church steeple, Captain Sharp rescues them and arranges to be Sam’s foster parent. These four days are sporadically marked by changes from day to night and some remarks, as when Scoutmaster Ward dictates into his tape recorder. An epilogue is reserved for 10 October.

Running athwart the day-by-day divisions are other blocks. Actually, the first day is shown us three times, via shifts in narrational attachment. First we’re with Scoutmaster Ward, his charges, and Captain Sharp, all of whom are searching for Sam. After Ward dolefully ends his audio diary entry (“Let’s hope tomorrow is better”), Anderson cuts to Sam in the stolen canoe.

You might think this scene of Sam paddling is taking place the next day, but actually it skips back to the morning of the 2nd, when he sneaked off. Thereafter we’re attached to him when he meets Suzy in the meadow and they share their first day on the run. Then the plot skips back again to earlier that night, when Mrs. Bishop calls Suzy to dinner and discovers that she’s gone.

The 2 September section is even more complicated than I’ve suggested. When Suzy and Sam rendezvous in the meadow, their encounter is interrupted by a flashback to their first meeting a year earlier (signaled by a title). Later, the Bishop-centered evening section is interrupted by another block, a flashback montage triggered by Mrs. Bishop’s discovery of the couple’s love letters.

Here Anderson provides important backstory paralleling the two kids’ reasons for running away. Sam is bullied by the older boys in the foster-family-compound run by the Billingsleys, and Suzy blows up at her parents and schoolmates. By the end of the third iteration of 2 September, all the major forces in the drama have been delineated.

The two expository flashbacks give us more reason to care about Sam and Suzy in the following scenes, particularly during their skirmish with the Khaki Scouts squadron. Redford’s bullying ways, ignoring Ward’s orders to avoid violence, earn him a lumbar thrust from Suzy’s scissors, and it’s a mis-aimed arrow that wipes out poor Snoopy.

The couple’s idyll, presented as more or less another block, becomes the center of the film. It ends, at the midpoint of the running time, with Suzy reading: “Part Two.”

After they’re captured, Mr. Bishop vows to keep Suzy from Sam. Worse, Captain Sharp learns that Sam is headed for an orphanage and maybe shock therapy. This will encourage Sharp to defend and rescue the two kids at the climax.

With this crisis looming, the plot gives us a sort of nocturne on the evening of September fourth and the dawn of the fifth. In the night, all the players mull over what has happened: Suzy and her mother, Sam and Captain Sharp, Mr. and Mrs. Bishop, and Scoutmaster Ward. But this isn’t merely downtime. The Scouts in their treehouse decide they’ve treated Sam unjustly and set out to help the couple. This decision propels the climax.

By the morning of the final day, Sam and Suzy are reunited and ready for their mock marriage. All that remains is for the storm to disrupt things (even giving Sam some shock therapy by lightning), but also to set things right. The epilogue shows the new stable state of the story world, tying together the plot action neatly. Scoutmaster Ward, reinstated from disgrace, has replaced Captain Pierce’s picture with Becky’s. Sam has a foster father, and he can covertly see Suzy every day.

The magic power of binoculars

Narration involves the moment-by-moment flow of story information, organized around the key question: Who knows what, when?

A simple example: Early in the film Suzy finds a letter in the family mailbox. She takes it to the bus shelter and reads it. When she’s done, she looks up resolutely at us and slips the letter into a shoe box.

What was in the letter? The narration has suppressed that information, stirring up curiosity and preparing us for what, many scenes later, Mrs. Bishop will reveal when she finds it: Sam’s final message about their rendezvous. Moreover, the narration flaunts its suppressiveness: She looks at us as if insisting that the message is private.

Unlike the letter scene, which suppresses information, the opening tours of the house give us a fair amount, but we’re not yet in a position to understand it. This applies to our glimpses of the scissors and the New Penzance locations, but there’s also the vertically rising shot showing Suzy’s suitcase in the attic along with her cat peeping out of the fishing creel.

This becomes significant only later, when we realize that Suzy is preparing to bolt.

The narrational process mobilizes film style, both visual and auditory, to engage us in a constant process of expectations—stated, prolonged, fulfilled, or cheated. Consider Suzy’s binoculars. Early in the film we see her looking through them, but we don’t see what she sees. What is she looking at? Or looking for? Soon enough we’ll see that she manages to learn of her mother’s affair with Captain Sharp.

Once we’re set up for the binoculars device, Anderson can use it elliptically. In the meadow we see Sam through binoculars, so we’ll assume that Suzy is looking at him, even if Anderson doesn’t show the customary head-on reverse shot of her.

In effect, this image of Sam is the answering POV shot that has been missing in the early sequences.

But at the climax, when Sam rushes back to camp to fetch Suzy’s binoculars, he’s again caught in their field of view. This immediately leads us to ask: Who’s watching him? Anderson has stuck to Sam in the scene, so we get a gratifying surprise when we learn that the odious Redford has grabbed the glasses and is watching Sam’s search.

Or consider the film’s opening as a narrational gesture. The toy world that the tracking shots present is packed with story information. The very first image shows a fabric version of the Bishops’ house, flanked by Suzy’s left-handed scissors; the picture will soon be echoed by an establishing shot.

Shot by shot, the film channels information in order to set up expectations, to prolong them, to confirm them, or to deflate them. This is how cinematic narration can engage us.

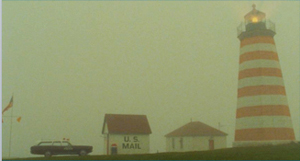

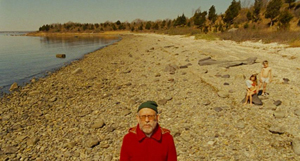

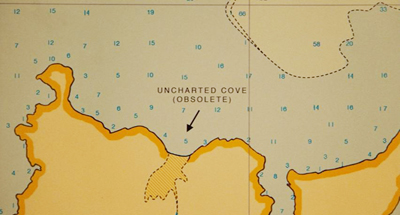

The gnome-like narrator is another source of information. Anderson has compared him to the Stage Manager in Our Town, who can address the audience but also interact with other characters. His opening explanation supplies factoids about this imaginary landscape, while foreshadowing things explicitly (the storm) and implicitly, as with this image that looks forward to Sam and Suzy’s interlude at Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet.

Narration doesn’t just pass along information; sometimes it suppresses it. It can point out when it’s hiding something, as when the film refuses to show us Suzy’s letter. Sometimes information is noticeably incomplete, as when only bits of Suzy’s and Sam’s correspondence are relayed to us. Another instance is the elliptical handling of the Khaki bullies’ attack on the couple, with a glimpse of an arrow and Paul-Sharits-ish flashes of scissors. Only quite a bit after the assault do we see the damage.

At other moments a film’s narration can create an informational gap that it doesn’t fill, only to do so later. During the central idyll Moonrise Kingdom omits a crucial piece of information and puts it in place only at the very end.

Down the aisle and face to face

Cinematic narration involves stylistic choices as well, and here again Anderson has sought an identifiable look and feel. In an earlier entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel, I talked about his adherence to planimetric images, the tendency to fix the camera at right angles to a background plane and then arrange figures either horizontally, like clothes on a line, or in profile.

Likewise, Anderseon employs what I’ve called compass-point editing. He usually puts the camera between the characters so that they face us in shot/ reverse-shot.

Or he films the action from straight-on, straight-back, or at a right angle. This geometry can be extended to camera movements: moving lateral and parallel to the planes of the shot, or panning at right angles, or zooming along the lens axis. Another extension is the straight-down angle, which is another variant of shooting at a different right angle to the action.

Planimetric shots and compass-point editing aren’t absolutely new with Anderson, but he uses them more thoroughly than most other filmmakers do. They govern his staging to the extent of pushing him away from realism. How plausible is it that all the Khaki scouts would line up on one side of the picnic table? Or that Ward wouldn’t notice, in a later scene, that all of them are gone?

Anderson’s use of such imagery evokes silent-film comedy, especially the compositions of Keaton, but these shots also suit a fairy-tale world. The stylized naivete of these compositions recalls children’s drawings, which tend to spread figures out against a flat background. (This was prefigured in the squashed perspective of the Bishop house as portrayed in the fabric picture.)

When a director commits to a particular style, he or she may have limited choices on other fronts. A good example is the climactic confrontation of all the adults in the St. Jack Wood church. Anderson might have staged this in many ways, but his stylistic preferences make the central aisle the most feasible arena. So we get the groups facing one another, in reverse-angle depth, moving from one planimetric composition to another, the cutting being either 180-degree reverses or simple axial cuts (zero-degree changes of angle). Sometimes the actors pivot to provide foreground profiles and frontal faces in the distance.

Once you the filmmaker embrace such a marked style so thoroughly, how can you signal special moments? In Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson does this by reverting to more commonplace technical choices.

When Suzy and Sam meet in the dressing room in 1964, we get straightforward 180-degree reversals.

And when they re-meet in the meadow, we get a mixture of profile and head-on shots.

But then Anderson starts to exempt them from the usual spatial strictures. The correspondence montage, for instance, retains the perpendicular framing but decenters his protagonists in mirror-image fashion.

As they get to know one another on their camping trip, the facing-front staging becomes less severe, more modulated.

And finally, when they admit their love to each other, Anderson gives us conventional ¾ views of faces and over-the-shoulder angles. These setups are reiterated when they embrace and dance.

At an emotional peak, Anderson sharply violates the film’s intrinsic norm by bringing in a common technique—which now gains a force it doesn’t customarily have.

Summer’s end

The epilogue recapitulates both narrative and stylistic features. There’s another lateral tracking shot of the Bishop house, but now Sam is painting in a space that was empty at the start.

Again Suzy is using her binoculars, but now, dressed in cheery yellow, she has something worth seeing.

On the soundtrack we hear Britten’s “Cuckoo” song, a reiteration of the summer’s-end motif. The cuckoo, born in spring, enjoys the summer but must eventually fly. As we hear this over Sam’s departure through the window, Anderson’s camera slides down to reveal that Sam’s picture presents a landscape that has now vanished.

Here is the big ellipsis that Anderson didn’t flag in the central idyll. When Sam was painting a stretched-out Suzy at Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet, they had agreed that the name of the place was insipid. She says she’ll think of a new name. But we’re told no more about the matter. In the epilogue, when we see Sam’s picture, we realize that they have given the place a better name: Moonrise Kingdom, inscribed in white on the shore.

“This is our land!” Sam had shouted when they looked out at the inlet. Like Anderson’s imagining of a parallel world of childhood, Sam has recreated, in the manner of modern fairy tales, something that is gone. As if in sympathy with the gesture, the film’s closing shot updates one that was given us during the scenes on the shore, with the yellow pup tent now pitched as the mist rolls in.

Did the couple really write MOONRISE KINGDOM on the shore during their stay? Hard to say. What matters is that, provoked by Sam’s picture, the film’s narration concludes by asserting the power of imaginative artifice.

Selling directors

Floating Real Scarab Beetle Earrings.

Thinking about auteurs has always obliged us to focus on the interchange between industrial demands and artistic aims.

In general, I don’t see an inevitable conflict between market demands and artistic expression. (I argue for this here and elsewhere.) True, often producers and executives and censors mangle creators’ efforts. But some directors know how to do what they want with what they have. For example, Hitchcock’s artistry benefited from his status as a celebrity director. He won substantial budgets and greater control of his work. And sometimes the suits’ demands improve a film (as I suggest here).

Historically, it isn’t easy to separate auteurs from their brands. Let’s assume that a branded auteur is one who is known to a broad public for certain qualities of his or her films. A simple measure would be an ordinary viewer saying “I like X movies,” where X is the name of the director.

Hitchcock is nearly everybody’s clear-cut example of an auteur, but by the time the Cahiers du cinéma critics were forging their conception of cinematic artistry, Hitch was a brand too. How else to explain the 1940s-1950s book collections bearing his name, or The Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, or the tag, “The master of suspense”? Hitchcock participated in this image-building with his jokey interviews, his walk-on appearances in his movies, and his reputation as a bland-faced prankster. Few directors today foster such shameless self-promotion. Also branded were Chaplin, Disney, Welles, and Cecil B. DeMille. Among the cinephilic public there was recognition of Huston, Sturges, and a few other hands.

Hitchcock is nearly everybody’s clear-cut example of an auteur, but by the time the Cahiers du cinéma critics were forging their conception of cinematic artistry, Hitch was a brand too. How else to explain the 1940s-1950s book collections bearing his name, or The Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, or the tag, “The master of suspense”? Hitchcock participated in this image-building with his jokey interviews, his walk-on appearances in his movies, and his reputation as a bland-faced prankster. Few directors today foster such shameless self-promotion. Also branded were Chaplin, Disney, Welles, and Cecil B. DeMille. Among the cinephilic public there was recognition of Huston, Sturges, and a few other hands.

Of course many of the auteurs discovered by the Cahiers critics were unknown to the public at large, and they didn’t make profitable pictures. In 1940s Hollywood, the successful Lang was Walter, not Fritz. But as the film industry developed, and as auteur criticism became prominent, directorial distinctiveness became a marketing angle. By the 1970s, the movie brats, along with older hands like Altman, were presenting themselves as having “personal visions” carried by their films.

More recently, US independent cinema has come to depend on several appeals (sex, social comment, and the like), but surely authorship is a central one. The indie scene exploits the signatures of directors as different as Lynch, Jarmusch, and Paul Thomas Anderson. The emergence of younger talent like Nicholas Winding Refn and Kelly Reichardt conforms to a similar pattern; people follow and support emerging directors, and distributors publicize the films that way. No wonder James Schamus, founder of Good Machine and late of Focus Features, once remarked: “I’m in the business of selling directors.”

This is just a fact of life for ambitious independent filmmakers. Wes Anderson’s cultivation of a distinct style is probably partly a genuine reflection of his personality and partly a matter of willed self-presentation. But of course we’re all indulging in self-presentation, using Goffman’s “impression management,” every time we interact with others.

Like an indie band, Anderson has created a marque unusual enough to let the fans feel they’re in on something keyed to their nonconformist tastes. He has provided the usual panoply of ancillary items, like soundtracks and bonus DVD tracks, but he has allowed others to participate in his world. Amateur videos comment on his style; graphic artists render their own versions of his posters. There are dozens of unlicensed Moonrise Kingdom tchotchkes. Anderson’s willingness to permit all manner of “tribute” memorabilia fits the handmade quality evoked by his films.

Like an indie band, Anderson has created a marque unusual enough to let the fans feel they’re in on something keyed to their nonconformist tastes. He has provided the usual panoply of ancillary items, like soundtracks and bonus DVD tracks, but he has allowed others to participate in his world. Amateur videos comment on his style; graphic artists render their own versions of his posters. There are dozens of unlicensed Moonrise Kingdom tchotchkes. Anderson’s willingness to permit all manner of “tribute” memorabilia fits the handmade quality evoked by his films.

Call it Geek Chic if you want, but it exemplifies an important and potentially valuable part of modern popular culture. For such reasons, I don’t see anything inherently bad about being an auteur with marketing possibilities. People don’t seem to object to David Lynch’s coffee and his nightclub. With eccentricity, spontaneous or willed, all is permitted.

My argument assumes that the term “auteur” picks out something neutral. For some people, though, it’s not a description but a compliment; there can be no bad auteurs. But I think we can have both weak auteurs—filmmakers distinguished only by technique or tone or narrative strategy—and downright bad ones as well. I have my own list.

This piece is based on a talk I gave earlier in July at the Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film in Munich. Thanks to Andreas Rost and Michaela Krützen for arranging my visit.

In the New Yorker column I mention, Richard Brody develops an argument along a different line than mine. As I understand it, he’s replying to critics who claim that the auteur approach overrates individual creativity at the expense of collaborators. He’s also objecting to the expanding search for ever more auteurs, who turn out to be minor artisans at best. My remarks are focused on different issues.

For much more on Moonrise Kingdom consult Matthew Zoller Seitz’s indispensable The Wes Anderson Collection. Michael Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture examines Anderson’s cinema as a development of the “Quirky Indie.” The fan-generated merchandise exemplifies what Henry Jenkins, in his book Textual Poachers, called “participatory culture.”