Archive for the 'Independent American film' Category

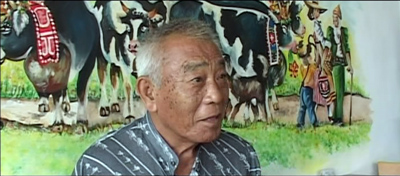

A man and his Focus

James Schamus on State Street, hailed by local livestock.

DB here:

“I wish,” one of my students said during a James Schamus visit to Madison back in the 1990s, “I could just download his brain.” Probably many have shared that wish. James is an award-winning screenwriter who has become a successful producer and head of a studio division, Focus Features (currently celebrating its tenth anniversary). No one knows more about how the US film industry works than James does. Yet he’s also deeply versed in the history and aesthetics of cinema. He teaches in Columbia’s film program, and his courses involve not filmmaking but film theory and analysis. How many people who can greenlight a picture have written an in-depth book on Dreyer’s Gertrud?

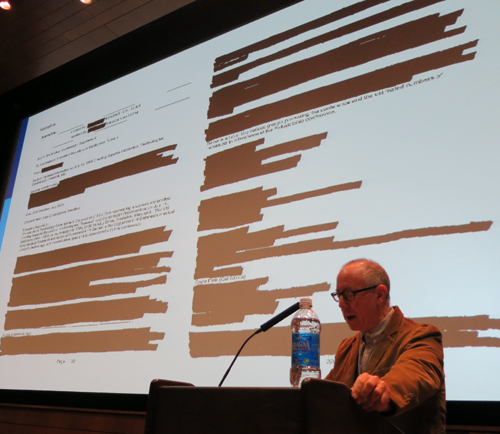

James came to campus last month for our Wisconsin Film Festival. His official event, sponsored by the University Center for the Humanities, was a talk called “My Wife Is a Terrorist: Lessons in Storytelling from the Department of Homeland Security.” That was quite an item in itself, tracing how James’ wife Nancy Kricorian discovered that she had a Homeland Security file. Pursuing that led him to broader meditations on digital surveillance in modern life. If he’s invited to present this in a venue near you, you’ll want to catch this provocative tutorial in how to read a redacted document.

While he was here, James spent a couple of hours in J. J. Murphy’s screenwriting seminar, and of course I had to be there. Herewith, some information and ideas from a sparkling session.

All battleships are gray in the dark

Hulk.

“This is not writing,” Schamus said. By that he meant that a screenplay isn’t parallel to a piece of creative writing, an autonomous work of art. Nobody ever walked out of a movie saying, “Bad film, but a great script.” In this he echoed Jean-Claude Carrière at the Screenwriting Research Network conference I visited back in September. A screenplay is “a description of the best film you can imagine.”

What sort of description? For certain directors, sparse indications are best. Collaborating with Ang Lee, Schamus knows he must under-write. Lee doesn’t want a movie that’s wholly on the page: “Ang wants to solve puzzles.” But for a studio project, the screenplay has to be airtight, since it functions as an insurance package for any director the producers hire. “A script has to be a battleship that no director can sink.”

James pointed out a bit of history. Back in the 1910s Thomas Ince rationalized studio production by using the script as the basis of all planning—budget, schedule, locations, and deployment of resources. The same happens today, with the Assistant Director breaking down the script for different phases and tasks of production. But on a studio project not everything is tidily planned in advance. Scripts can be rewritten during shooting or even later. Sometimes there are “parallel scripts”: stars can hire writers who spin out “production rewrites” to be thrust on the director. James, who has prepared the screenplay for Hulk and done his share of uncredited rewrites on other big films, speaks from experience.

Independent companies rely on screenplays too; Focus is writer-friendly. But in this zone of the industry, the writer needs to create a “community” around a script idea—a director or group of actors and craft people that support it. These are as valuable as a polished screenplay in getting a film funded.

What about the current conventions, like the three-act structure? James rejects the Syd Field formula. He thinks that the writer will spontaneously devise some intriguing incidents and arresting characters without recourse to beats, arcs, and plot points. “You can’t have half an hour go by without giving your characters something to do, or to shoot for.”

He also suggests that the writer’s second draft should be an exercise in rethinking the whole thing. “Don’t write your second draft from the first-draft file.” In your redraft, use flashbacks, play around with structure, or tell the action from a different point of view. This will engage you more deeply with the material and show you possibilities you hadn’t imagined. In terms I’ve floated in various places: take the same story world, but recast the plot structure or the film’s moment-by-moment flow of information (that is, its narration). Or try choosing a different genre. For The Wedding Banquet, James turned the original script, a melodrama, into a situation derived from screwball comedy.

Down in the mosh pit

Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

James has been both an independent producer, in partnership with Ted Hope at Good Machine during the 1990s, and a specialty-division producer with Universal for Focus. The moment of passage for him came when, rewriting Ang Lee’s first feature, Pushing Hands, James realized that he had to get the whole project in shape for filming. After that, and The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman, producing followed naturally.

When James started, a single person could cover most producer duties on an indie film, but now it’s very difficult. Finding material, gathering money, signing talent, checking on principal photography and post-production, planning marketing and distribution across many platforms, tracking payments after release—it’s all a daunting task for one individual. Today an indie movie may list seven to twenty producers. Some probably helped by finding money, some worked especially hard to get material, and a few just slept with somebody.

A traditional producer’s job is to keep the budget under control. Today, with digital filming making special effects cheaper, screenwriters and directors think naturally of more elaborate visuals. This can work with something like Take Shelter, James suggested, but on the whole he thinks that directors shouldn’t jump to extremes. He recalled that using “handcrafted effects” cut the original budget of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by a third, and that led to more unusual creative results, like outsize sets and in-camera trickery.

The “independent cinema” scene has always been quite varied. Again James had recourse to history: in the 1960s both United Artists and Roger Corman were labeled independents. The artier independent side developed through the infusion of foreign money and new technology. From the 1970s onward, overseas public-television channels invested in US films by Jarmusch and others, while cable and home video needed product and so financed or bought indie projects. The video distributor Vestron, for instance, could not acquire studio films, so, armed with half a billion dollars, the company began generating its own content. In the same era, pornography was shot on 35mm, and many crafts people learned in that venue and transferred their skills to independent cinema.

Today, however, the indie market is both more fragmented and more fluid. The spectrum space between tentpole Hollywood and DIY indies is being filled by net platforms and cable television. James pointed to the ease with which Lena Dunham moved from Tiny Furniture to the HBO series Girls. Downloading and streaming add to the churn. IFC and Magnolia distribute films, but these companies are owned by cable channels and hold theatrical venues as well. They acquire scores of new films a year, using theatrical releases to get reviews that can support VOD and DVD. Focus can tier its marketing in similar ways, using DVD and VOD outlets to lead viewers to content online under the rubric Focus World.

These new “paramarkets,” James suggests, are porous, overlapping, and still evolving. Traditional windows, he says, have become a mosh pit.

James had a lot more to say, and I expect to be referencing more of his ideas on VOD in a blog to come. But this gives you a taste of the energy and breadth of his thinking. He’s constantly busy but never less than enthusiastic and generous. He always has time to share ideas about anything, from politics to cinephilia. The most exhilarating thing about talking with him is that you know more excellent work lies ahead.

Apart from titles I’ve already mentioned, James Schamus’ screenplays include The Ice Storm, Ride with the Devil, Taking Woodstock, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Lust, Caution, Films that he produced and/or distributed include Poison, The Brothers McMullen, Safe, Walking and Talking, Happiness, The Pianist, 21 Grams, Lost in Translation, Shaun of the Dead, A Serious Man, Coraline, Brokeback Mountain, The Motorcycle Diaries, Eastern Promises, Atonement, Reservation Road, In Bruges, Milk, Sin Nombre, Greenberg, The Kids Are All Right, The Debt, Pariah, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy…and plenty more.

Schamus provides a video review of the top ten Focus titles chosen by viewers for the company’s anniversary.

J. J. Murphy blogs about screenwriting, the avant-garde, and independent film here. His most recent book is The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol.

More on the concepts of story world, plot structure, and narration can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in my book Poetics of Cinema. A brief account is here.

James Schamus lecturing, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for the Humanities, 19 April 2012.

Carry me back to the old Virginia

Chaz Ebert and Roger Ebert on the stage of the Virginia Theatre, Ebertfest 2012. Photo by DB.

DB here:

The fourteenth Ebertfest, held in the sumptuous Virginia Theatre in Urbana, had its customary mix of independent films old and new, Hollywood classics (sometimes cult classics), an Alloy Orchestra performance, and some unclassifiable items. It was, as ever, a crowd-pleasing jamboree. It reflected Roger’s eclectic tastes and was brought to us by Chaz Ebert, festival director Nate Kohn, and woman-who-knows-and-does-all-things Mary Susan Britt.

You can see the intros, the panels, and the Q & As—that is, nearly everything, except the movies and the offside fun–on the Festival channel here.

The young and the restless

Kinyarwanda.

First features are a hallmark of Ebertfest, and many have stayed in my memory, among them The Stone Reader (2003), Tarnation (2004), Man Push Cart (2006), The Band’s Visit (2008), and Frozen River (2009). This year there were several feature debuts.

Patang (The Kite) concentrates on a single day in the life of a family celebrating the annual festival of kite-flying in Ahmedabad, India. An uncle has returned to town with his daughter, and usual in such movie reunions, old tensions are reignited. A side-story concerns Bobby, a street-wise local, and a little boy who delivers kites. Needless to say, this story intersects with and sheds light on the primary family conflict.

Prashant Barghava is a pictorialist with an eye for startling color and compositions. Shot in nervous handheld images, with many planes of action jammed together and the camera eye seeking something to focus on, Patang reminded me of The Hurt Locker, but without that film’s sense of ominous vigilance. The tone of this one is more exuberant, and the cast of nonactors gives it vibrancy.

Kinyarwanda, by Alrick Brown and an energetic team of collaborators, explores the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in an unusual way. It displays the role of the Muslim community in protecting the Hutu population (many Christian, some not) from the depredations of the Tutsi death squads. To emphasize the breadth of experience, the film adopts a chaptered network-narrative structure. A Catholic priest, a young woman, an angry Tutsi, a sympathetic imam, a little boy, and a leader of the Rwanda Patriotic Front gradually converge, first in a mosque compound, and ten years later in a reeducation and reconciliation camp. The film also plays with time, replaying some key events—notably the Tutsi’s advance on Jeanne’s home—but also anticipating some outcomes. Interestingly, by showing many of the Tutsi killers in 2004 repenting their crimes before we see those attacks, the film builds a degree of compassion into its overall form.

Scenes with adults are dominated by either personal problems (the Hutu/ Tutsi clash infiltrates a marriage) or discussions of religious doctrine. There are as well wordless moments in which we follow children—a little girl whose Qu’ran has been defaced, a boy who encounters a death squad while sent to fetch cigarettes. If the adults supply the film’s prose, the kids are its poetry.

Patang played both Berlin and Tribeca and will be opening in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco soon. Kinyarwanda won awards at several festivals, including Sundance and AFI Fest, and is coming to several other festivals. It arrives on DVD 1 May.

The misfit section

Terri.

Two other young directors got good exposure. Robert Siegel wrote the screenplay for The Wrestler after working on The Onion (Madison cheer obligatory here). His debut feature, Big Fan, is the story of a football fan who is mangled by his idol and has to struggle against his family’s pressure to sue. Patton Oswalt, who had to cancel his Ebertfest visit at the last minute, played Paul with a potato-like obstinacy that offset the shrieking caricatures around him. On the down side, I could have done with a couple of hundred fewer close-ups. (Watching a movie at the Virginia reminds you of the power of the two-shot.) Still, Siegel wisely doesn’t give his hero a girlfriend who would lead him to the Big Normal and wean him away from his obsession. As Siegel points out, “He’s completely happy, but everyone around him thinks he’s unhappy.” Big Fan is an enjoyable portrait of the sports nerd.

More laid-back was Azazel Jacobs’ second feature Terri. It’s sort of a coming-of-age movie, but it has a peculiar humor that such wistful exercises usually lack. Terri, an enormous teenager, goes to high school in pajamas and is teased mercilessly, but he reacts with a dead-eyed passivity that suggests both resignation and resilience. Like the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, the book Terri is working his way through, he’s tied down by Lilliputians around him, but he gets by.

It’s a film of character revelation rather than plot turns. No, Terri’s addled uncle isn’t going to die; no, Terri’s not going to lose his virginity. The action revolves around Jacob Wysocki as the title character and John C. Reilly, who never disappoints in any film, as the school principal. Their scenes together are the heart of the film, and if Terri is looking for a father-figure/ role model this off-center administrator with a soft heart for hard cases wouldn’t be a bad choice. To the film’s credit, though, we have little reason to suggest that he’s looking for any such thing. This movie has tact.

I ran into another Ebertfest first-time-director, Nina Paley, whose Sita Sings the Blues (2009) I first saw and loved at Roger’s event. Kristin had already seen it at the Wisconsin Film Fest. Sita worked her way into our blog and into our Film Art material. Nina, long a foe of copyright in any form, told me she plans an act of “copyright civil disobedience” soon. In the meantime, check her effervescent blog site, news of her new project Seder-Masochist, and excerpts from her new books about Mimi, Eunice, and their take on IP.

And then there was…

Take Shelter.

The first evening’s late show was given over to John Davies and Raymond Lambert’s Phunny Business, a documentary about the rise of a Chicago comic club, and this was preceded by Kelechi Ezie’s The Truth about Beauty and Blogs. I had to miss the doc, but go here for a review from Scott Jordan Harris. The short was charming—a snappy comedy about a single woman trying to be Queen of All Media on her YouTube show. Very quickly her aplomb cracks and she uses her online persona to recapture her straying boyfriend. Her web skills give her a rostrum, and then a tracking device (she follows him on Facebook), but soon her site turns into a diary of mounting desperation.

Higher Ground: Not a come-to-Jesus moment but a go-from-Jesus one. I had trouble figuring out the tone. I think the obvious caricatures, including an unctuous evangelical marriage counselor, were there to suggest that the ordinary believers were more worthy of respect. But they all gave me the creeps, including the relentlessly sunny pastor. Also, it seemed a bit of a hothouse drama. I missed a sense of exactly where this story took place, and I kept wondering how all these people made a living wage. But of course it’s Vera Farmiga’s film, and as usual she projects a wary intelligence. The opening sequence showing a string of people being immersion-baptized had a winning radiance.

Joe vs. the Volcano: Joe wins the match, sort of. It deserves to be a cult film for its portrayal of a workday out of the dankest basements of Brazil and Hudsucker Industries. Still, I thought everybody was trying a little too hard, especially Meg Ryan. Cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt talked about how he likes shooting on film and showing on digital: Film’s richness can support 4K, 8K, or whatever. As for 48 frames per second: “I can’t wait.”

Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time: A warts-and-all tribute to the stubborn director of over thirty films. I can’t think of a question to ask about Paul Cox that the film doesn’t answer.

The Alloy Orchestra: Wild and Weird: Classic early trick-films plus a couple of avant-garde items from the 1920s given new brio by the Alloy boys. It was fun but less hefty than earlier efforts. I especially liked re-seeing Winsor McKay’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (aka The Pet) from 1921, which replays McKay’s fascination with figures and spaces that swell to mammoth proportions (a bit like Avery’s King-Size Canary), though the effect is less looming onscreen than in the comics. You can see the whole thing, and other of the W & W titles, on Fandor, one of this years E-fest sponsors.

I’d like to see the Alloy talents and others move away from the big spectacles like Napoleon and Metropolis, which appeal to our current tastes in splashy films with special effects, and toward quieter, less-known silent masterworks by the French (e.g., Germinal), the Danes (The Abyss, The Ballet Dancer, The Evangelist’s Life), Italians (Il Fauno, Rapsodia Satanica, Ma l’amore mio non muore) and above all Victor Sjöström. Audiences would, I think, love Ingeborg Holm, Sons of Ingmar, Masterman, and The Girl from Stormycroft, and the Alloyists could do them proud. Not to mention William S. Hart, whose films are among the pride of US silent cinema.

Take Shelter: A tour de force of what literary theorists call the fantastic: Is the hero going mad, or is there indeed something real behind his visions of impending disaster? Everyone has praised, and rightly, the precision of the performances and framings. Jeff Nichols was another first-timer at Ebertfest some years back, with Shotgun Stories. Take Shelter is the sort of movie that makes independent American cinema proud.

A Separation: I wrote about it here a year ago, having seen it during what might be my last visit to Hong Kong. This time around, I admired it all over again. It shows many characters’ attitudes without bias (everyone has his or her reasons), and it’s aware of how lies told out of loyalty corrode love. The screening was enhanced by excellent background information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Omer Mazaffar during the Q and A.

If you’re a good storyteller, I think, you balance straightforward presentation (e.g., A Separation’s exposition, which sketches in the core of a relationship) and somewhat sneaky suppression (e.g., the ellipsis that hides a key event from us). I’ve argued that Iranian directors understand suspense better than almost anybody working today, and this film supports that hunch. Now let’s get hope we get to see, on some platform, Arghadi’s earlier exercise in mystery and ambivalent morality, About Elly. Now there’s an overlooked/ forgotten film.

E-fest goes digital

Ebertfest has shown digital copies of films in the past, notably Bad Santa and Woodstock, but this time around only Take Shelter was on film. Everything else was on HDCam, except Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time, which was on Blu-ray.

James Bond, legendary projection magician and theatre designer/ outfitter, oversaw the shows. Although the films often looked very good on the 50+ -foot Virginia screen, his expert eye saw shortcomings in the digital versions. Even I could detect the videoish quality of Joe vs. the Volcano. It looked pretty good, but compared to what James had shown in years past—70mm prints of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, My Fair Lady—there was definitely a sense that we were passing into a new era. Above you see James between his thoroughbreds, the lovingly assembled 35/70mm projectors.

Because Steak ‘n Shake became a festival sponsor this year, Roger presented James with the first-ever S-n-S award, a cap displaying the motto, “In Sight It Must Be Right,” a fitting label for James’ superlative standards in projection. Here he receives the Order of Takhomasak.

James was ably assisted by Steve Kraus and Travis Bird, who is both a musician and a cinephile. Great guys and great professionals, all.

The Virginia Theatre, an analog artifact if there ever was one, is closing after Ebertfest this year. It will be renovated and spiffed up, with new seats and many other upgrades.

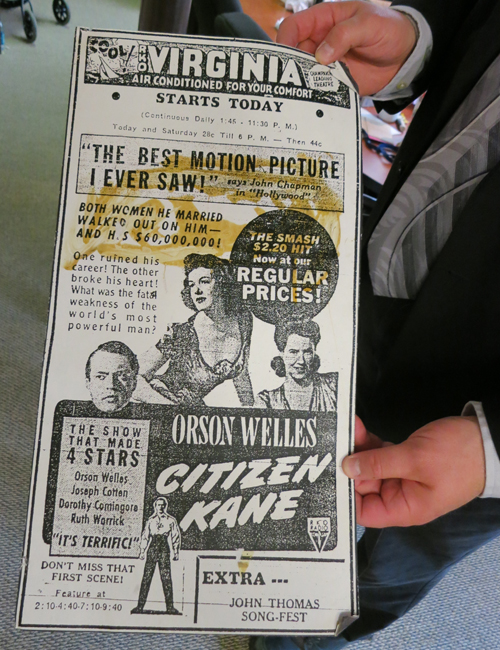

The festival wrapped up with Citizen Kane brought to us digitally. A Blu-ray copy was screened, and instead of the film’s original track, we heard Roger’s pointed and wide-ranging 2001 commentary. He was by this point an old hand at play-by-play explication, after years with his “Cinema Interruptus” series, now taken over by Jim Emerson. After the screening, I was happy to be able to interview Jeff Lerner, of Blue Collar Productions. Jeff produced and recorded Roger’s commentary. Again, check the Ebertfest channel if you want to see the Q & A, which takes off after Chaz’s moving memoir.

Thanks to the many staff and guests who made this year’s Ebertfest especially enjoyable. I’m particularly grateful to C. O. “Doc” Erickson for giving me an interview for an upcoming blog entry, and to David Poland and Michael Barker for enlightening table talk. Thanks as well to Jim Emerson, excellent companion of the highway.

Thanks to Kat Spring and Nate Kohn for correction of boo-boos.

Speaking of digital, here’s a neat possibility: http://gizmodo.com/5906353/the-avengers-screening-delayed-because-some-dunce-deleted-the-freaking-movie.

This deserves a blog entry of its own. The hands belong to Steven Bentz, Virginia Theatre Director, whom we must thank for preserving this ad (from, I assume, 1941). Note the listing of start times for the feature, and the request not to miss the opening. This is a topic discussed elsewhere on this site.

Time for a quick one: A miscellany from friends

The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror).

DB here, catching up with books, videos, and events:

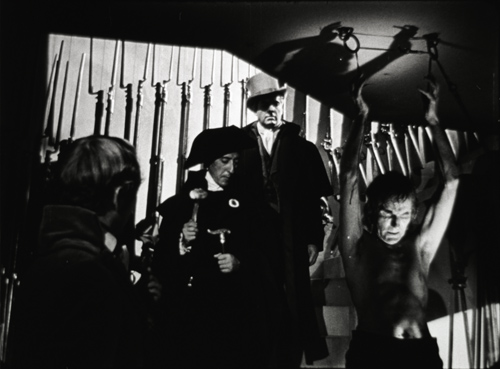

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

In The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror) Menzies found soul mates in two other aggressive pictorialists, Anthony Mann and John Alton, the team becoming “a crazy triangle,” eager to indulge in “thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositons.” Bob Cummings never looked so bizarre, before or since. I didn’t talk about this wild movie in my online Menzies material here and here because I had such poor illustrations from it. Now things have changed, and a decent, or perhaps rather indecent, sample of the film’s delirium (above) can serve to back David’s point.

David’s “Dreams of a Creative Begetter” is one of several film-related pieces in this issue of The Believer. The issue includes a DVD of the seminal People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), which gathered the talents of Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, and Rochus Gliese. A helpful introductory essay is at the Believer site.

Speaking of David’s writing, don’t miss his superb shot-by-shot analysis of a key scene in Gilda at his Shadowplay site, an obligatory stop for all cinephiles.

Seldom does a monograph on a single film probe so deeply as Mette Hjort’s new book on Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. It’s easy to take this movie as Dogme Lite, since compared to the earliest, rather harrowing Dogme efforts, it’s an ingratiating romantic comedy-drama. Mette does justice to this side of Scherfig’s film, but she also shows that it’s an exercise in moral seriousness. Reconstructing the production process, she conducts in-depth analysis of performance and technique. She is sensitive to actors’ moments, such as simply laying down a knife and fork; aware that these gestures are developed through improvisation, she is able to trace how each character is built up through details.

In her books and articles on the Dogme school Mette has shown that its innovations go beyond the vaunted technical “rules.” She always addresses them, of course; here she provides an illuminating typology of ways the rules have been followed or dodged. But she also stresses, as most writers don’t, that Dogme films engage with matters of political importance. For example, she has shown that The Idiots’ controversial display of “spazzing” triggered an important debate about Danish attitudes toward the disabled. In her new book Mette indicates that Scherfig’s efforts to endow her characters with the dignity to be found in everyday life offers viewers a chance “to re-connect with one of their culture’s most powerful moral commitments.” Mette talks about the project in this video.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

Michael starts by looking closely at the audiences and marketing. He suggests that viewers engage with the films through particular viewing habits (e.g., “Characters are emblems”). He then shows how these habits were nourished and refined by distributors, promotion, and film festivals. The next two sections of the book consider what we might take to be the two poles of indie difference from Hollywood: greater realism, and more self-conscious artifice. The central chapters analyze realism in relation to “character-centered” filmmaking in the Indie trend. Michael turns a critical eye on characterization in films as different as Walking and Talking, Lost in Translation, and Welcome to the Dollhouse. The third batch of chapters considers the trend’s other major appeal, the sort of play with style and form we get in the Coens, Tarantino, Nolan, and others.

Michael shows how character-driven realism and gamelike artifice mesh well with the mandates of distribution and reception—how, in effect, “originality” becomes something that can be calculated and branded. The book concludes with thoughts on the evolution of the trend, comparing Happiness with Juno and raising the inevitable question: How artistically independent is independent film? Newman leaves us pondering: “Indie cinema has become Hollywood’s most prominent alternative to itself.”

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

Chris concentrates on 1960s black-themed films from A Raisin in the Sun onward, because he wants to trace how filmmakers tried out a variety of ways to represent and comment on black life. It was a transitional era, but as he puts it “because of the insights they reveal about the periods that bracket them, transitional periods are among the most fascinating and significant in all of film history.”

For Chris, Gone Are the Days (1963), The Cool World (1964), Uptight (1968), The Landlord (1970), and the unproduced Confessions of Nat Turner provide case studies of alternatives to what became the crime-and-comedy product of blaxploitation. Why did decision-makers believe that black-themed films would sell broadly enough to repay investment? What choices and compromises were necessary to “universalize” material (for white viewers) while also retaining “authentic” blackness? Or was it better simply aim the films at white liberals?

Chris tackles such questions through a painstaking study of the film industry’s efforts to find, or create, an audience for films that took great risks. Written with verve (on the screen handling of the Black Panthers, Chris talks about Hollywood’s “Black Power outage”), Soul Searching revives films that are all but forgotten and shows how their efforts to create one variety of independent cinema failed for particular social and industrial reasons.

Someone I’ve been meaning to spotlight for a while: Frédéric Ambroisine is a multitalented critic, filmmaker, stuntman, and collector based in Paris. One of his careers is making supplements for French DVD releases of Hong Kong films, both classic and current. If you have even a smattering of French, you can follow his supplements with ease. He gets precious interviews with screen legends like Kara Hui Ying-hung and Ku Feng (below), master villain of the great New One-Armed Swordsman.

The videos from Wild Side often include Fred’s featurettes. You can follow Fred’s activities at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead. Much of the material in both places is in English.

Finally, if you’re in Los Angeles this week, why not visit the celebration of Orphan Films playing at UCLA 13 and 14 May? While I was in New York in February, I met NYU’s Dan Streible, moving spirit of the Orphan Films movement. Dan and his colleagues work with archives, collectors, and filmmakers to save films that fall through the cracks, digging up everything from home movies to news clips and experimental cinema. Dan curated a program of orphans at our local festival earlier this spring. At UCLA he will be a guest for screenings and discussions of many orphan titles, including the mysterious Madison Newsreel (Madison, Maine alas, not Wisconsin). Go here for Sean Savage’s discussion of the orphan oddity that has become a cult movie, and here for background on Northeast Historic Film, which found the footage.

PS: Speaking of friends, I should thank the solicitous people who wrote me during my recent illness. I appreciate your get-well notes, and I’m happy to report that I’m on the mend.

“World’s Youngest Acrobat” (Hearst Metrotone/ Fox Movietone 1929). From Orphans 7: A Film Symposium.

INCEPTION; or, Dream a Little Dream within a Dream with Me

Kristin here:

Inception reminds me of the common claim that Hollywood films are no longer character-centered. Special effects and slam-bang action supposedly have replaced character traits as the basis for storytelling. Now, here is a contemporary film released as a summer tentpole film and definitely successful in box-office terms. It crossed the $200 million domestic gross figure on Tuesday, August 3. Yet the nearly universal complaint, for those who don’t like the film, or some aspects of the film, is that we don’t get to know the characters.

If modern tentpoles have generally neglected characterization, that must be a convention by now. Why would people expect to find rounded characters? Is this complicated/complex (take your choice) intellectual film aimed at adults ironically going to prove that the critics of modern Hollywood blockbusters have been right all along?

I agree that the characters in Inception, apart from Cobb, the protagonist, are barely assigned traits. Ariadne, for example, does not return to join Cobb’s team as its architect because she has some personal goal or trait that inclines her to want to do so. It’s just that everyone who experiences the possibilities of shared dreams gets hooked.

But if there’s little characterization, is Nolan substituting something interesting in its place—apart from the usual computer-effects and spectacle? The first time I saw the film, I suspected he is, but for a long time I couldn’t figure out what. As a result, I did not really enjoy it until the point where the van breaks through the railing on the bridge and starts to fall. That’s pretty far into the film, 104 minutes in a roughly 140-minute film, not counting the credits. The van’s beginning to fall also marks the end of what we’ve called the Development portion of the film and the beginning of the Climax. (See here and here and here.)

At that turning point, it dawned on me that Nolan has elevated exposition of new premises to the main form of communication among characters. Discussion of their personal relationships, hopes, and doubts largely drops out. As the Russian Formalists would say, exposition, usually given early on and at wide intervals later in a plot, becomes the dominant here. That’s an unusual enough tactic to warrant a closer look.

We grasp most of the characters by the types of premises they provide. Yusuf is the man who understands how to manipulate the sedatives that will allows the team to progress deep enough into Fischer’s subconscious to plant the idea. Oh, yes, and he has a cat. Robert Fischer is the man who thinks his father despised him, so he is susceptible to the team’s machinations to plant the idea in his subconscious. (Saito says that Fischer has a “complicated” relationship with his father, but it’s actually just the opposite: a single trait, which is all that’s needed to establish his part in the action.) He also seems to be very concerned with security, since his subconscious conveniently peoples the dream levels with bodyguards who provide obstacles, fatally wound Saito, and force the van off the bridge, among other functions.

The characters’ goals, apart from Cobb’s, arise from the premises of the dream-sharing technology. Of course, they want to get paid, but that’s assumed. Their actions all arise from the need to keep doing what they must to sustain the dreams and later from the need to improvise solutions to unforeseen problems that seem to violate the rules they have previously known. Why they need the money, whom they go home to when off-duty, how they got into this business, and all the other conventions of Hollywood characterization, are simply ignored. Even Saito’s claim that Maurice Fischer’s corporation is dangerous to the world because it controls so much of its energy sources is simply assumed to be true. Our possible suspicions that Saito himself might really be the more dangerous tycoon, out to eliminate a powerful rival, might add a little complexity. The film, however, never hints at such a possibility.

Ariadne is somewhat different in her function. As in so many Hollywood films, there are two lines of action. First, there is the attempt to perform inception in Fischer’s subconscious. Second, there are Cobb’s related goals of getting back to his children but also of holding onto his dead wife through his visits to his projection of her in dreams. No one besides Ariadne fully understands Cobb’s obsession with Mal and hence she alone sees the danger it poses to the team. Ariadne lives up to her ancient namesake, guiding us through the maze of the Cobb’s obsession by acting as an expository figure in that storyline.

That is presumably why she doesn’t simply tell Arthur, who is much more experienced than she is in sharing dreams, about Cobb’s dangerous obsession. Instead, she decides to go into the dream levels as part of the team to keep on eye on Cobb—thus allowing her to continue as a privileged witness and transmitter of vital information about that storyline.

Each new premise creates a link in the chain of actions, and for the most part the actions are governed by the rules, or apparent rules of the dream-sharing machine, the sedatives, the levels, the characters’ respective skills, and all the other factors.

The narration constructs its causal chain by being nominally omniscient. For short stretches of the film we may be “with” Ariadne and Cobb or Mal and Cobb and witness them having personal conversations, most dramatically when Cobb fails to talk Mal out of leaping to her death. These moments provide the main alternative to the exposition-ridden dialogue, and they are a very small portion of the overall speech in the film. Yet the narration arches over all, stitching together the series of causes by moving us among the levels, catching at exactly the right moment the critical action (Arthur is putting a stack of dreaming people into an elevator) or dialogue (Cobb is asking Ariadne where she designed a route bypassing the labyrinth in the hospital).

Once I realized that this film’s plot concerns fiendishly complicated action that requires almost constant exposition from the characters, I enjoyed the rest of it. I saw it a second time and enjoyed it even more. I certainly don’t understand the entire plot, and I suspect that’s partly because, despite the nearly constant revelation of premises, there were a few left out. For one thing, just how does Eames, the “forger,” manage to change into other people? (No mention of polyjuice potion or anything else.) I can understand how he might do it in his own dreams, but the one dream where he doesn’t change is his own. Even the guides to Inception that have already been posted on the internet don’t answer every question. (Here and here are two examples of many.) Perhaps when the DVD comes out, the answers will be forthcoming—more of them, but probably not all.

In the meantime, I don’t see why we should get annoyed because Inception doesn’t contain rich, fully rounded characters. It’s clearly a puzzle film that takes the usual complicated premises of a heist movie and pushes them to extremes. Accepting the flow of nearly continuous exposition may remove some of the frustrations viewers face. After all, there’s no rule against it.

DB here:

When an actor comes to me and wants to discuss his character, I say, “It’s in the script.” If he says, “But what’s my motivation?”, I say, “Your salary”.

Alfred Hitchcock

Forget dream stuff for a while. Yes, Nolan says he was interested in dreams, especially lucid dreaming. Yes, he claims that the precision of detail in the film was an effort to suggest how “real” dreams feel when you’re having one. And yes, critics have defended the films’ dream worlds as realistic, or attacked them as phony substitutes. All interesting points and worth exploring, but not my focus at the moment.

And forget videogames. I leave that stuff to the experts, such as several members of our Wisconsin Filmies listserv. They have kindly pointed out many analogies and disanalogies. (See the coda for specifics.) And of course there’s no shortage of commentary about the film’s ties to gaming, or dreaming, on the Net.

My focus instead is motivation. Not the sort that Hitchcock and Bergman talked about, but rather the idea that any artwork needs to justify certain elements or strategies it presents.

Motivation beyond Bergman

You want your movie to have musical numbers. How to justify them in your story? Many early musicals simply make the characters show-business types, so we see them rehearsing and performing numbers for the audience. Other musicals cast that “realistic” motivation aside and let the characters sing and dance wholly for one another. But then those films were appealing to a sort of motivation familiar from opera, where characters simply burst into song or dance without realistic motivation. We accept this type of artifice too because that’s just what this genre of film permits—the way that horror films include monsters that are unlikely to exist in the real world.

The notion of motivation turns a lot of our usual thinking about cinema inside out. Usually we think that something is present in order to support what the film “says.” But actually a lot of what we find in films is motivated, either by genre or by appeal to realism, in order to give us a particular narrative experience.

For a couple of decades, some American cinema (both Hollywood and indie) has been launching some ambitious narrative experimentation. We’ve seen “puzzle films” (Primer), forking-path or alternative-future films (Sliding Doors), network narratives (Babel, Crash), and other sorts. This trend isn’t utterly new—there are earlier cases, especially in the 1940s—but it seems to have been accelerating in recent years, particularly after Pulp Fiction (1994). Christopher Nolan has participated in the trend as well, with Following and Memento.

The film industry encourages some degree of innovation. Novelty can attract attention, and perhaps audiences too. Yet, as I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It, such innovations are counterbalanced by traditional storytelling maneuvers. These make sure that audiences aren’t entirely lost. For example, Memento’s backward structure requires very explicit signposting of the transitions, highlighting objects or gestures we’ve seen in the previous time-slice to link them to the next one we see. At the same time, these experiments can pay off financially: a complex narrative that balances enigma and understanding can lure audiences to revisit the multiplex or buy the DVD for further scrutiny. Remember, we are all nerds now.

Memento illustrates a couple of ways in which Hollywood efforts at innovation are controlled by tradition. First, you can motivate a film’s formal play through genre conventions. A science-fiction film, for instance, can invoke time travel or alternate universes. Doc’s time machine in the Back to the Future series motivates a fairly unusual play with cause and effect, particularly in the second installment. Likewise, mystery and detective stories pioneered the “lying flashback,” when people give false testimony about a crime (as in Crossfire). The possibility that a film noir will encourage complicated narration (an optically subjective first-person narrator in The Lady in the Lake, a dying narrator in Double Indemnity, a dead one in Sunset Blvd.) helps us recognize that Memento is an experiment in that tradition.

Second, you can motivate formal experiment through the movie’s appeal to some widely-believed law of life, a common-sense realism. Uncanny coincidences in movies like Serendipity and Sliding Doors are justified by the notion that fate or spiritual harmony can bring soulmates together. Six Degrees of Separation’s plot exploits the idea of social networks. Likewise, the backward progression of Memento’s plot is partly justified by the clinical condition of short-term memory deficits. I grant you, why this ailment supports a reverse-chronology tale is a bit puzzling—but that may only suggest that we’re ready to overlook flimsy justification if the novelty is piquant enough. A little motivation can go a long way.

So we ought to recognize that Inception is relying heavily on motivation from these two sources, genre and commonsense realism. Science fiction grants the possibility of entering people’s dreams through a futuristic technology. Likewise, we have all experienced dreams, so the film can appeal to folk wisdom about them. I suggest, though, that the purpose of the film not to explore the dream life but rather to use the idea of exploring the dream life to justify creating a complex narrative experience for the viewer. That is the purpose of the film; the dreams operate as alibis.

Interestingly, traditions outside Hollywood don’t require these sorts of motivation for narrative experiments. Last Year at Marienbad is perhaps the supreme example of a purely artificial construct, which can’t be justified by genre or subject/theme. I’d argue that Kieslowski’s Blind Chance, Buñuel’s Obscure Object of Desire, van Dormael’s Toto le héros, and other films of a highly artificial cast either ignore or cancel both realistic and generic motivation. They present themselves as experiments in storytelling, pure and simple. Another art-cinema motivational ploy invokes psychological realism, as in Fellini’s 8 ½. This is less daring than the blunt-artifice option, and so has been more easily adapted to mainstream storytelling.

One more point about the New (or now Not-So-New) Narrative Artifice. Strategies that seemed striking in the pioneering films are quickly mastered by others. Innovations are copied, and the learning curve is steep. By now anybody can create a fairly coherent network narrative or forking-path tale. Artistically ambitious filmmakers want to press further. So how can you create fresh experiments in storytelling today?

Architecture beyond Ariadne

If you decide to organize a film in sharply distinct plotlines, you have two problems. First, how do you combine them? What will be the overall architecture? Second, how do you fill in the chain of actions?

Consider combination first. You can create parallel plotlines, as in Intolerance’s assembly of four different historical periods or in Vera Chytilová’s Something Different, in which two women living at the same moment lead very different lives. You can create branching or forking-path plotlines, as in Run Lola Run. You can link stories through a simple overlap, as in Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, or by letting them pass through the same place; the inn in Wong’s Ashes of Time functions as a sort of node that gathers together the destinies of different characters.

One sort of plot construction that hasn’t been explored deeply in recent years is actually one of the oldest. The embedded story, or the tale-within-the-tale, dates back at least to The Odyssey. In the standard case, we have one level of story reality, and in that a character tells a story that takes place earlier and elsewhere. Typically the embedded story is pretty extensive, with its own structure of exposition, development, crisis, and climax. You can of course multiply the stories, as in The Arabian Nights, The Decameron, and The Canterbury Tales.

Sometimes the framing story is merely a backdrop, though usually that has its own dramatic impetus: Scheherazade tells a story each night to postpone her death. Often, though, the framing situation carries the main interest. In Don Quixote, readers are tempted to skip the tales told by people whom the knight and Sancho encounter, in order to get back to the real story, the relationship of the central pair.

The “discovered manuscript” convention of nineteenth-century fiction was an equivalent of this pattern, a sort of novel-within-a-novel. Some experimental fiction has exploited the embedded story; I think of Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. The principle of embedding has been found in cinema too, of course. Citizen Kane is the classic example, since it embeds recounted stories (most of the flashbacks), a written text (Thatcher’s memoirs), and even a film-within-a-film (News on the March). Many of the embedded stories we find in films are presented as flashbacks, and those are usually motivated by a character recalling or telling another character about past events. (See our blog entry “Grandmaster Flashback” for some more discussion.)

The task of the author is to motivate the story’s presence through relevance to the framing situation. Why insert the tale in the first place? Most commonly, it involves some of the same characters we find in the surrounding story world, as in a flashback. In that case, the embedded tale supplies new information about plot or character. It may also provide a parable or counterpoint to what’s happening in the surrounding situation. In The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931), a woman is about to leave her husband, but she changes her mind when a family friend tells her, for the bulk of the movie, about the sacrifices made by the husband’s mother.

Some researchers might argue that the purest instance of this format is one in which the characters of the overarching frame story don’t participate in the embedded tale. Classic instances like the Mahabhrata are often studied as compilations. A partial instance in cinema is the country-house frame story of Dead of Night, in which some characters recount stories that didn’t involve them. Here the frame story arouses considerable interest in its own right.

Once you allow the possibility of an embedded story, some storyteller will ask: Why not embed a story into the embedded story? And so on. Calvino’s novel does this, suggesting the possibility of that infinitely extended series we see when somebody stands between two mirrors and the image is multiplied forever. (Inception gives us such an image when Ariadne summons up mirrors on a Parisian street.) Hollywood filmmakers experimented with multiple embedding in some flashback films of the 1940s. In The Locket and Passage to Marseille, there are flashbacks within flashbacks. More daring, and closer to Calvino, is Pasolini’s Arabian Nights, in which one character recounts a tale in which he encounters another character, who recounts his tale, and so on.

Here, I think, is the accomplishment of Nolan’s film. The general absence of complicated embeddings today (at least since The Matrix) presents an opportunity for an ambitious moviemaker. Inception constitutes an extended experiment in what you can do with a nested plot structure, motivated by the dream-invasion premise.

The Dream team

Nolan adds a new wrinkle. Instead of recounting or recalling stories, the characters enter worlds “hosted” by one of their number and furnished by another. The movie introduces this strategy to us obliquely. After the prologue in which Cobb confronts a very aged Saito in Limbo (which I think you can take as either a flashforward or a symptom of their collaborative dreaming at the moment), we are plunged into layers of embedding. In the real world, Cobb, Arthur, and the architect are dreaming with Saito on a train; we later learn that this is an audition to test Cobb’s extraction skills. They dream that they are in an apartment where Saito meets his mistress. But in that apartment they are sleeping, and dreaming that they are in a luxurious mansion where Cobb is trying to discover Saito’s secrets. That effort is disrupted by Mal, Cobb’s ex-wife, and the dream world collapses.

What’s tricky is that Nolan doesn’t establish these layers of embedding in customary order. The flashback tradition leads us to expect to move from outside to inside, like peeling an onion: from the train to the apartment to the mansion. Instead, we are first shown the mansion, and we get glimpses of the apartment. That tactic hints that the apartment is the primary level of reality in the fiction. But in the apartment Saito notices discrepancies in the carpet, making him realize he’s dreaming. Only then does Nolan shift to the external frame, the four men on the train, minded by a young Japanese passenger.

This has been our first training exercise, and it turns out to be based on surprise: We weren’t aware of how many embedded plotlines were in play. In the film’s terms, the dream session on the train went down two levels. Cobb says he can go down three, and that forms one goal for the team.

Later exercises are simpler, involving only shared dreams rather than embedded ones. That’s because these dreams operate as tutorials, as when Cobb shows Ariadne how dreamworlds are constructed and populated (though the framing situation is deleted at the outset–another, if milder, surprise). The dreams also function as psychological probes, as when Ariadne learns that Cobb’s unresolved problems with his wife are expressed in her eruptions into whatever dreamworld is conjured up. These études have to be relatively transparent if we’re to understand all the premises of this game. Similarly, our introduction to Limbo is given not through dream-penetration but through a good old flashback, when in the first-level dream world Cobb confesses to Ariadne that he and Mal built their own dreamscape there. Limbo changes the rules of the game to such an extent that we shouldn’t have to worry about who’s dreaming what for whom; a straightforward piece of visual exposition does the trick.

The most intricate embedding takes place in the final seventy-five minutes, most of the second half of the film. Instead of a train, a plane. Instead of four dreamers, six: the target young Fischer, plus all the members of the team, including Ariadne, who will monitor Cobb’s subconscious. Each team member hosts one story world, the other members enter it, and Fischer gets to populate it. Yusuf the chemist hosts the rainy car chase that leads to the van’s descent to the river. Arthur the point man hosts the hotel scene in which Cobb accosts Fischer. Eames the Forger (or rather the imposter) hosts the snow fortress siege, in which Fischer is induced to confront his dying father (thinking he is entering the dream of the family confidant Browning). Finally, to pursue Mal, Cobb and Ariadne plunge into the beachfront/ metropolis zone of Limbo constructed by the couple during their dream days. It’s then revealed that Cobb brought about his wife’s idée fixe by planting the idea that dreams could become reality; this showed him, with tragic consequences, that inception could work.

So we have five levels: the plane trip embeds the rainswept chase, which embeds the hotel, which embeds the snow fortress, which embeds the Limbo confrontation. The nested structure is recapitulated in the burst of shots showing Ariadne snapping awake in each level up to the submerged van (dream level 1).

Indeed, I think that one prime purpose of Nolan’s fancy structure is to foster such little coups. The Ariadne passage is cinematically simple—just a string of quick, graphically matched close-ups—but in context arresting. Of course that context displays a clockwork intricacy. What Nolan has done is created four distinct subplots, each with its own goal, obstacles, and deadline. Moreover, all the deadlines have to synchronize; this is the device of the kick, which ejects a team member from a dream layer. With so many levels, we need a cascade of kicks.

The last forty-five minutes of the film become an extended exercise in crosscutting. As each plotline is added to the mix, Nolan can flash among them, building eventually to four alternating strands—with additional crosscutting within each strand (in the hotel, Cobb at the bar/ Saito and Eames in the elevator/Arthur and Ariadne in the lobby). Each level has its own clock, with duration stretched the farther down you go. One thing that has long struck me about classical crosscutting is that in one line of action time is accelerated, while in another it slows down. The villains are inches away from breaking into the cabin/ the hero is miles away/ the villains are almost inside/ the hero is just arriving. I wonder if Nolan noticed this aspect of the crosscutting convention and built it into his plot, supplying motivation (that word again) by stipulating that different dream levels have different rates of change.

Another clever touch is what Nolan doesn’t include in the orgy of crosscutting: the framing situation in the first-class jet cabin. Once we leave that, we don’t see it again for about seventy minutes. I think we tend to forget about it, so that Cobb’s startled expression upon finally awakening mimics our own realization that all the intense physical action has been enframed by this quiet, stable situation.

I think that structurally, if not stylistically, the climax is a virtuoso piece of cinema. It recalls Griffith’s Intolerance, which also intercuts the climaxes of four plotlines, and supplies crosscut lines of action within each line as well. Here, one might say, is one way to innovate in the New Narrative Artifice: Create something like the Intolerance of the twenty-first century.

Possible, and not that unstable

The film is shameless in its regard for cinema, and its plundering of cinematic history. What’s fun is that a lot of people I talk to come up with very different movies that they see in the film, and most of them are spot-on. There are all kinds of references in there.

Also like Griffith, Nolan has hit upon some ways to make his innovation user-friendly. For one thing, as most viewers have noticed, he situates his levels in very different locales: rainy, traffic-filled city versus eerily vacant metropolis; cushy hotel versus more Spartan one; beach versus mountains. This allows us to keep oriented during even the most rapidly cut portions. More subtly, Nolan has, deliberately or not, respected the limits of recursive thinking, or metacognition.

As shrewd members of a very social species, we are all good at mindreading, figuring out what other people are thinking. I know that Chelsea admires Hillary. We’re good at moving to the next level too: I know that Chelsea believes that Hillary wants to monitor Bill. And I know that Chelsea believes that Hillary suspects that Bill is smitten with Monica. If you drew this situation as a cartoon, you’d have one thought bubble inside another inside another, and so on—like the Russian-doll structure of the climax of Inception.

It turns out that our minds can’t build these nested structures indefinitely. We hit a limit.

Peter believes that Jane thinks that Sally wants Peter to suppose that Jane intends Sally to believe that her ball is under the cushion.

Robin Dunbar, whose example this is, suggests that most adults can’t handle so much recursion. His experiments indicate that the normal limit is at most five levels—just what we have in Inception (four dream layers plus the reality frame). Add more, and most of us would get muddled.

The filmmaker’s second big problem with modular plotting, I mentioned near the start, is how to fill in the plotlines. Let me suggest a general principle, at least for storytelling aimed at a broad audience: The more complex your macrostructure is, the simpler your microstructure should be. In Memento, the high degree of redundancy between memory episodes and the unusually heightened transitions help us track the backward layout of scenes. Similarly, all four episodes of Intolerance culminate in a race to the rescue—a device that was by 1916 immediately legible for audiences.

Genre plays a role in simplifying the modules too. Our efforts to make sense of Memento are helped by film noir conventions like the trail of clues, the deceptive allies, and the maneuvers of a femme fatale. Likewise, Griffith used the conventions of current genres to fill in the plotlines of Intolerance. The Christ story can be seen as a recasting of the many pious Passion plays of the first years of cinema. The Babylonian story and the Huguenots’ story rely on the established conventions of the costume pictures, including the French and Italian features that were popular at the time. (Capellani, discussed in an earlier entry, was one master of this genre.) And of course Intolerance’s modern story is pure melodrama, showing a young family pulled apart by the forces of urban poverty and bluenose reform. Griffith wove together not only four epochs but several genres.

So does Nolan in Inception. He recruits the conventions of science fiction, heist movies, Bond intrigues, and team-mission plots like The Guns of Navarone to make the scene-by-scene progression of the plot comprehensible. The iterated chases and fights keeps us grounded too, though you might wonder why Fischer’s subconscious projections all seem to have leaped out of a Bruckheimer picture. And of course you’ve seen many of the other images before, from the Paris café to the luxury hotel bar. Shamelessly clichéd, the image of kids playing in the sunlight immediately evokes fatherhood and family in any film.

I’ve already argued that the comparatively transparent training and exploration sessions in the middle of the film help us keep our bearings. Another handhold is the convention of the new male melodrama, the husband or boyfriend trying to come to terms with the death of his woman. The simple action movie, from Death Wish to Bad Boys, uses vengeance to ease the man’s torment. The more “serious” plot makes the man responsible in some degree for the woman’s fate. The emotional temperature rises as the male protagonist tries to fight his feelings of guilt, turning it outward to a perpetrator (as in The Prestige) or inward (as in Memento, and Shutter Island). The under-plot of Inception, driven by Ariadne’s curiosity, gradually reveals to us that Cobb gave Mal the fatal idea of dwelling in dreams.

Moreover, the rise of fantasy, science-fiction, and comic-book movies has brought a new interest in creating “worlds” with their own laws. Once you have Superman, you need a secret identity and Kryptonite and well-placed phone booths, not to mention a host of constraints on what can and can’t happen. Comic books supply not only a world furnished with characters and settings but also rules about conduct, morality, even physics. George Lucas, in his youth more of a comic-book reader than a cinephile, took over this principle of construction for Star Wars. Of course this idea of richly furnished, rule-governed worlds has been elaborated more fully in videogames. My point is that contemporary viewers are ready to ride with this as another convention of contemporary virtual-world storytelling, and this habit simplifies our pickup of the rules governing Inception’s embedded stories.

In sum, as ambitious artists compete to engineer clockwork narratives and puzzle films, Nolan raises the stakes by reviving a very old tradition, that of the embedded story. He motivates it through dreams and modernizes it with a blend of science fiction, fantasy, action pictures, and male masochism. Above all, the dream motivation allows him to crosscut four embedded stories, all built on classic Hollywood plot arcs. In the process he creates a virtuoso stretch of cinematic storytelling.

I could find faults. As in The Dark Knight, Nolan’s action scenes are clunky and distressingly casual in their composition and cutting. He is much better at mind games than spatially precise physical activity. Some dialogue could be pruned too. (What are you doing here? He loved you–in his own way. Something is happening…as we speak.) And I haven’t even posed the interpretive issues. Find a sympathetic young woman to exorcise the demonic wife you can’t quite abandon. Find a new father figure (Japanese mogul) to replace the old one (Brit architect). Use the spinning top to exemplify both change and stability, childhood and maturity, and/or the unending flux of narrative. As Kristin hints, the whole thing might actually be complicated rather than complex; instead of a dense but coherent cluster of principles we might have a shiny contraption, bolting on new premises as it hurtles along.

Nonetheless, if current excitement about this movie is any measure, Nolan has pulled off the big balancing act. The film is redundant and familiar enough to let most of us follow the main trajectories on the first pass. Yet it’s enigmatic, elliptical, and equivocal enough to keep many of us talking about it. . . and watching it again. Recidivism, thy name is Inception.

Based on Uncle Scrooge? That’s rich!

Kristin back again:

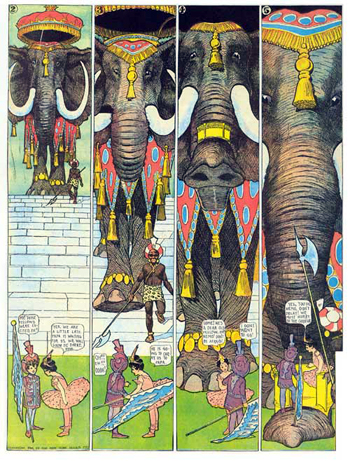

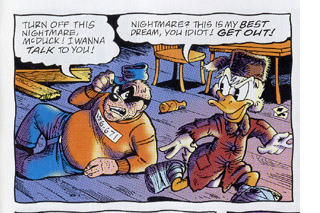

There has been much suggestion on the internet, sometimes in jest, sometimes in earnest, sometimes half in jest and half in earnest, that Nolan got the idea for Inception from an Uncle Scrooge comic story with a shared-dream premise, “The Dream of a Lifetime!” Nearly all postings on this subject date this comic, created by Don Rosa, to 2002. Yes, “Dream” first appeared in 2002—in Danish. It came out in the U.S. in the May, 2004 issue of Uncle Scrooge (Gemstone #329). In 2006, it was reprinted in Rosa’s book, The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck Companion.

A download of “The Dream of a Lifetime” is available online, but it is missing a page, so I’m not linking it here. The Companion volume is out of print but can still be purchased here. It contains Rosa’s “The Making of ‘The Dream of a Lifetime!’” “The Dream of a Lifetime” is included in the tenth and final volume of a series reprinting all of Rosa’s duck stories chronologically by their original appearance. The “Behind the Scenes” section at the back leads off with a revised version of “The Making of ‘The Dream of a Lifetime!'” Here Rosa mentions the theory that Inception was based on his comic tale. He saw the film only after reading about this on the internet and being skeptical of fans’ claims. His comment upon seeing the film is “And … whoa … I was no longer so dismissive of those internet theorists. There are so many elements in Inception that match aspects of my story very closely! Ah well–no matter.” (p. 175)

If Nolan got the idea from the Rosa tale, which seems unlikely, he certainly developed upon and changed it considerably. In fact, there are more significant differences than similarities.

First, the similarities:

1. In “The Dream of a Lifetime!” several people enter the dream by being hooked up to a machine. Here it’s a radio-controlled device invented by Gyro Gearloose, who intended for it “to help psychiatrists examine the dreams of their patients.” (Gearloose was created in 1952 by Carl Barks to provide whatever wacky invention his plots required.) The receivers are metal colanders wired as antennae and worn on the heads of the people sharing the dream.

2. Waking up from visiting the dream is triggered by falling (see below).

3. Characters in reality can attempt to insert objects or situations into the dream by making sounds or presenting objects for Scrooge to smell, though this usually goes comically wrong. This somewhat resembles the premise that the jolts of the van in the first dream level of Inception cause earthquake-like rumbles in the second level and so on.

4. The characters frequently explain to each other how the shared-dream technology works. Rosa makes this humorous in part by starting the story with Scrooge dreaming and the Beagle Boys arriving in his money bin with the Gearloose equipment, which they have already stolen. He then makes the exposition deliberately clunky and obvious. One of the stupider Beagles asks, “Sure … uh … tell me again how it works?” There are then several panels of explanation as the group arranges the equipment to enter the dream. As they are about ready, one remarks, “But I’ll explain later” how they will get Scrooge to tell them the combination to his vault.

5. All of the characters who enter Scrooge’s mind are aware that they are in a dream, as is Scrooge, who has had each of these dreams many times.

Now, the differences:

1. There is a single dreamer throughout, and Scrooge remains in his own bed.

2. There is only one level of dreaming, and Donald, who enters the dream to foil the Beagle Boys, returns at intervals to the bedroom to report progress and plan strategies.

3. Spatially, the dream extends only a short distance around Scrooge. If the characters move too far from him, it fades out, which Rosa represents by having portions of the panels go white. The Beagle Boys exit the dream, one by one, by falling into the white void (see below).

4. Scrooge’s dreams are essentially flashbacks, though they are altered by the other characters who enter the dreams. The plot passes through a series of seven recurring dreams, all based on real adventures Scrooge has had in the distant past. Each of the seven dreams derives from situations in Rosa’s The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck series. (The one-volume edition of this series is out of print, but it still is available in a two-volume version, here and here.) These dreams take place out of chronological order, and Scrooge’s age changes with each new dream. (The stories are “The Vigilante of Pizen Bluff,” #6, Scrooge age 23; “The Dreamtime Duck of the Never Never,” #7, age 29; “The Master of the Mississippi,” #2, age 15; “The Empire Builder from Calisota,” #11, age 45; “The Buckaroo of the Badlands,” #3, age 15; “The Last of the Clan McDuck,” #1, age 10; and “Hearts of the Yukon,” #8C, age 31.)

5. The rules are relatively simple. Crucially, Scrooge may be any age within the current dream, but he, being the main dreamer, recognizes Donald and the Beagle Boys.

5. The rules are relatively simple. Crucially, Scrooge may be any age within the current dream, but he, being the main dreamer, recognizes Donald and the Beagle Boys.

6. “Dream” is designed to be funny, as when the Beagle Boys keep complaining that they’re in a nightmare, while Scrooge thinks of them as pleasant dreams. This is normal life to such an adventurous character.

It should be clear that the complexity of Rosa’s story originates not from the shared-dream structure, which is fairly straightforward. Rosa is more interested in finding a way to rework some of the scenes from his earlier biographical Scrooge comics. The whole Life and Times project originated from Rosa’s working method of teasing out minutiae about Scrooge from the original Carl Barks stories and then concocting sequels or prequels to them. Life and Times is an attempt to use all the mentions of past events, relatives, locales, and dates to devise a biography of Scrooge. “Dream of a Lifetime!” carries that modus operandi one step further.

The other big difference between “Dream” and Inception is that a reader who was not familiar with the seven earlier stories would miss much of what goes on in “Dream.” It was written for McDuck aficionados as a sort of game of recognition. For those who do recognize the seven situations referenced, “Dream” is quite easy to follow. For those who don’t, it must seem complicated and mysterious, most crucially since they won’t recognize Glittering Goldie, Scrooge’s lost love, in the opening “private” part of the dream.

In contrast, Inception is self-contained and tries for a very different sort of game of comprehension with the viewer, one which would not be aided by knowledge from other Nolan films.

“Dream” is also recognizable to fans as another of the “trick” stories that Rosa has written occasionally. These are not linked to Barks’s stories but develop some simple premise that allows Rosa to play with time and space in virtuoso fashion. These include “Cash Flow,” where the Beagle Boys buy an anti-friction ray-gun (Uncle Scrooge, Gladstone #224); “The Beagle Boys vs. the Money Bin,” (Uncle Scrooge, Gemstone #325), where the Beagle Boys find a map of the money bin; and my favorite, “A Matter of Some Gravity” (Walt Disney’s Comics, Gladstone, #610), where Magica de Spell buys a wand that turns gravity sideways for Scrooge and Donald.

In short, if Nolan ever saw “Dream of a Lifetime!” it could only have given him a few ideas out of the many that went into Inception.

DB coda:

For more discussion of the art of Christopher Nolan, see his category on the right-hand side of the page. We have an analysis of sound in The Prestige in the ninth edition of Film Art: An Introduction, and there we discuss the film’s narrative strategies as well.

Despite not caring for the movie, Jim Emerson has been assembling a wide-ranging and long-running dossier on Inception, with many comments. Scroll down the several entries here. Likewise visit David Cairns, who makes the necessary Anthony Mann comparison. The Wikipedia entry on the film is information-packed, and it includes several helpful links.

Our UW informants suggest that videogames having affinities with Inception include Assassin’s Creed II, Meigakure, and Shadow of Destiny. Thanks to Jason Mittell, Tim Palmer, Evan Davis, Leo Rubinkowski, Ethan de Seife, Edward Branigan, and Andrea Comisky for suggestions. See also Kirk Hamilton’s “Inception’s Usability Problem.”

On fourth-and fifth-level mindreading, see Robin Dunbar, The Human Story: A New History of Mankind’s Evolution (London: Faber, 2004), pp. 45-52. Dunbar’s study found evidence suggesting that women are better at tracking recursive mental states than men are.

Jan Simons offers an analytical survey of writing about New Artifice in an article here. For interpretations of particular films within the trend, see Allan Cameron, Modular Narratives in Contemporary Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) and Warren Buckland, ed., Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009). I try to lay out some narrative principles governing such films, including Memento, in The Way Hollywood Tells It and in the essays “Film Futures” and “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance” in Poetics of Cinema.

PS (17 December 2010): We have a rethink of Inception in this later entry.

[November 29, 2018: I have updated the section on Don Rosa’s “The Dream of a Lifetime!” by removing or updating dead links, correcting one error, and adding a few remarks on Rosa’s updated making-of essay on the comic. (KT)]