Archive for the 'Independent American film' Category

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

(50) Days of summer (movies), Part 1

Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea.

DB here:

Travel took me out of Madison for half of June and nearly all of July. While overseas, I saw only one recent US release. So I caught the American Summer Movies in two gulps–over a couple of weeks early on and over the last month or so. In all, exactly 50 days? Well, were there exactly 50 first dates in that movie?

Herewith, comments on a batch of titles. There are spoilers sprinkled throughout, but most of what I say won’t harm your encounter with the film. Because all my remarks amounted to an even longer blog than usual, I’ve broken it into two parts. The next installment, coming up in a few days, talks about The Taking of Pelham 123, Public Enemies, and Inglourious Basterds.

My summer movies were bracketed by two animated pictures. Up is to my mind the most mature Pixar film yet. It has all the virtues we associate with this studio: quick but not frantic pacing, expert handling of resonant motifs, technical brilliance (especially in its depiction of settings), and one-off gags. The poker-playing dogs had me laughing out loud. But as we’ve argued in other blogs (here and here and here), the Pixar team likes to set itself tough challenges. First there is the technical challenge of 3-D, which is easily surmounted. The 3-D effects get more pronounced once the plot lands in South America. More important, I think, is the challenge of representing the emotion of sorrow.

Another movie would have organized its plot around the kid, Russell, and let him meet the elderly Carl in the course of his adventures. That way, Carl would emerge as a merely touching secondary character. But by focusing point of view around Carl’s life, showing his marriage and widowhood, Pete Docter and his team have tackled one of the hardest problems of classic moviemaking. How do you render pure sentiment without becoming sentimental?

The protagonist’s portrait is surprisingly hard-edged. Carl is tightly wound even in his youth, unlike the exuberant and extroverted Ellie. Yet the couple seems to have no friends throughout their marriage, and it becomes easy to see how Carl could will himself into crabby isolation after her death. Thanks to the choice of viewpoint, Carl becomes no mere crank but a truly empathetic figure.

This is fragile stuff, and Docter handles it with tact. Many movies want you to cry at the end, but Up daringly invites you to indulge in its first ten minutes. It then spends the rest of its running time brightening your mood, so that the title could describe the film’s emotional trajectory. It’s one of my two favorite new movies I saw this summer.

Just a few days ago Kristin and I saw Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea. We’ve been Miyazaki fans since Totoro, and have especially admired Kiki’s Delivery Service and Spirited Away. As with this last and with Howl’s Moving Castle, I have a hard time figuring out the premises of the plot. What rules govern Ponyo’s transformations? Why can’t she become a real girl, exactly? And then why is she permitted to? The well-timed interventions of her mother, like the Witch’s change of heart in Howl, seems a way out of plot difficulties, and as often happens in Miyazaki the plot resolution seems rushed in comparison with the leisurely development of characters’ relationships.

But as usual I was won over by the effortless virtuosity of the imagery and the weird conviction suffusing Miyazaki’s concept of nature. As in Spirited Away, animation becomes animistic. The sea is bursting with hidden forces: goldfish with extraordinary powers of group effort, waves that turn into blue fish, and bubbles as solid and slippery as balloons. Nobody but Miyazaki could imagine the quasi-Wagnerian scale of Ponyo’s race, atop gigantic fish-waves, to catch up with Sosuke and his mother fleeing in their car.

These shots burst with more dynamic shifts of mass and scale than I’ve felt in any official 3-D picture.

Sometimes Nature is scary. Although nothing here is as traumatic as Spirited Away‘s transformation of parents into swine, the tsunami scenes induce genuine awe at nature’s exuberant destructiveness. There follows a reassuring calm. Ponyo and Sosuke glide along the flood waters while ancient creatures zigzag in the depths, and the townspeople quietly accept that their homes have been engulfed. Ponyo is a gentle movie, aimed (as Miyazaki explains here) at a younger audience than was his recent work. It’s suffused with simple human affection, seen in acts of spontaneous generosity. What American movie could include a moment when Ponyo, fish become girl, offers a nursing mother a sandwich to help her make milk for her baby? Again, sentiment without sentimentality. Ponyo offers more evidence that whatever the disappointments we may find in live-action movies, we are living in a golden age of animation.

Am I just being perverse in finding Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen not as abysmal as others have? Don’t get me wrong. It is not what you’d call good. It is rushed and overblown. What other movie accompanies its opening company logos with gnashing sound effects? Its plot is even more preposterous than the first one’s. Its performers bear that sheen of meretriciousness that fills nearly every Michael Bay project. It is also lazy in its plotting. Worse, I couldn’t really make out the design of the ‘bots. It’s not that the cutting is abnormally swift (a mere 3.0 seconds ASL, about the same as in Up and slower than that in The Hurt Locker). The problem is that the digital camera is swirling around the damn things so fast as they take shape that you can’t get a fix on what they actually look like. All those spinning wheels and dangling carburetors ought to be worth a glance.

But still….For non-Transformers shots Michael Bay at least puts his camera on a tripod, which these days counts as a plus with me. And a minibot humps the heroine’s leg. And John Turturro is in it. Would he grace a movie that signals the fall of Western Civilization?

In a similar vein but more satisfying was District 9. Its “racial subtext” is as perfunctory and confused as such weighty hidden meanings usually are, and anyhow whatever political points the movie wants to make drift out of view halfway through. Moreover, its “documentary immediacy” is inconsistent: despite footage marked as coming from surveillance and TV cameras, we have unimpeded access to all plot matters. But here the Bumpicam probably allows for cheaper CGI, and as a run-around-shooting-things movie, it needs to keep things simple.

In a similar vein but more satisfying was District 9. Its “racial subtext” is as perfunctory and confused as such weighty hidden meanings usually are, and anyhow whatever political points the movie wants to make drift out of view halfway through. Moreover, its “documentary immediacy” is inconsistent: despite footage marked as coming from surveillance and TV cameras, we have unimpeded access to all plot matters. But here the Bumpicam probably allows for cheaper CGI, and as a run-around-shooting-things movie, it needs to keep things simple.

I found the smash-and-grab look far more distracting in The Hurt Locker. Kathryn Bigelow has directed several first-rate movies, notably Near Dark (where she used a tripod), Blue Steel (ditto), and Point Break (tripod mostly). On this project, she seemed to me to be doing more conventional work. There are the titles telling us that time is running out (“16 Days Left”). There’s classic redundancy of characterization, as when we’re told that James is a hot dogger–“He’s reckless!” “You’re a wild man!”–as we watch him be all that he can be, and more. There’s the hapless kid who is so near to the end of his tour that you know he’s a marked man. There are even aching slow-mo replays of explosions bowling guys to the camera. What if war films gave up this convention and just showed bombs going off and bodies hurled around as fast as in reality? Might war look a little less picturesque?

The camera is locked down for these iconic slow-mo shots, but most of the scenes are handled in heat-seeking pans, artful misframings, chopped-off zooms, and would-be snapfocusing that can’t find something to fasten on. The editing plucks out bits of local color and sprinkles in some glimpses of onlookers that tend to turn them into props. I’ve tried to show elsewhere that this trend in rough-hewn technique nonetheless adheres to the conventions of classical style: establishing/ reestablishing shots, eyelines, reactions, and close-ups to underscore story points. Even wavering rack-focus can still orient us to the action quite clearly.

The question is what the harsher surface adds, especially when it’s so pervasive. Habituation is one of the best-proven phenomena in psychology, and movies like this seem to prove that it works. After the first few minutes, we’ve adapted to any visceral punch that the Unsteadicam hopes to provide. Maybe it serves to ratchet up suspense? Doubtful. A director would have to be a real duffer to dissipate suspense in a movie about dismantling an explosive device. The trick is to do something different, as in bomb-disposal movies like the Chinese Old Fish and the British Small Back Room.

Still, the plot is decently engaging, and there’s a taut, unpredictable siege in the desert. That long sequence displays a disciplined interplay of optical viewpoints, a sense of constantly revised tactics, a new aspect of James’s leadership style, and nice details about sharing juice boxes. In another era, The Hurt Locker would have been a studio picture in the vein of Anthony Mann’s bleak Men in War. I suppose it shows that yesterday’s genre film, executed with conviction and a certain edginess, can become today’s art movie.

Speaking of suspense: I thought that the setup to A Perfect Getaway was reasonably engrossing. There was some clever self-referential teasing: our hero’s a screenwriter, and there’s talk of a “second-act twist.” And it was mostly shot on a tripod. I hoped that director-writer David Twohy would have the courage to stick with its initial premise and be Deliverance in Hawaii. But sure enough, the things that smelled like red herrings were red herrings, and the reversal that you feared comes to pass in one of those point-of-view switcheroos that movies now indulge in. Come to think of it, that was the second-act twist. But I did like the strategically placed telemarketer call.

We’re evidently allotted one crossover indie movie per summer, a fact acknowledged in the title of this year’s hit. (500) Days of Summer, which really needs its parentheses not just because everybody now overuses them (there’s even a blog confessing it), but because its strategy is to disarm you with its knowing cuteness. It is so self-consciously winning your teeth will ache. It’s a twentysomething romance of the sort usually called “bittersweet.” The guy’s after love and the girl withholds commitment. Guaranteed result: emotional roller coastering, because we’ve seen her flighty sort before in kooky-girl figures like Petulia. There’s a fantasy musical number with a touch of animation, an avuncular narrating voice sliding in and out, a shuffled time scheme sorted out for us with a sort of daily odometer reading, and pop-culture references including retro ones to The Graduate and Ringo Starr. Everybody smiles a lot, and when they’re not smiling they’re crinkling up their faces.

(500) Days plays by the book. Tom and Summer work for a greeting-card company, a satiric target only a little harder to hit than the Pentagon. As in the movies mentioned above, the cutting is intent on making sure we see everybody deliver every syllable. (What ever happened to offscreen dialogue? Did TV kill it?) (Sorry about the parentheses.) The four-part script layout is as neat as embroidery: the first kiss at the photocopiers comes at 24:00, the splitup comes at 47:00, Tom delivers his diatribe against the lies about love at about 72:00, and the epilogue, with its fatal final line, finishes at 90:00. Yet I’m not curmudgeon enough to despise a movie so desperate to be liked, and at last I found a film whose narration clicks along in syncopation with my little tally counter.

The real indie film I admired in my fifty days was Ramin Bahrani’s Goodbye Solo, or Good Bye Solo as the credit title has it. Kristin and I have registered our admiration for Bahrani’s films here and here on this site, and his latest is no less modest, well-crafted, and affecting. A Senegalese emigre cab driver befriends an enigmatic old man who at the start of the film offers him $1000 to pick him up on October 20 and drive him to Blowing Rock Mountain. Solo infers that William is planning a suicide and so starts to intervene in his life. His involvement with William gets intertwined with his family problems and his hopes of becoming an airline attendant.

Goodbye Solo exemplifies the “character-driven” movie. Solo is sunny, quick-witted, and socially adroit; his audition for the airline managers shows him as an ideal employee. William is just the opposite–morose, aggrieved, profoundly unhappy. The treatment is observational, with lengthy shots (an average of over twelve seconds) capturing dialogue and slowly shifting character response.

The characters change, but Bahrani and his co-screenwriter Bahareh Azimi, wary of quick fixes, don’t push this too far. It would be easy to make William soften more, even eventually make him likeable, and to keep Solo an indefatigable force for optimism. Instead, if William accepts more of Solo’s ministrations, it’s largely due to his passivity, not a fundamental change of heart. Meanwhile, Solo becomes more anxious and pessimistic, shedding some of that casual charm that captivated us in the opening. Neither executes that neat character arc that Hollywood tends to favor and that’s visible in Up and (500) Days of Summer.

The characters change, but Bahrani and his co-screenwriter Bahareh Azimi, wary of quick fixes, don’t push this too far. It would be easy to make William soften more, even eventually make him likeable, and to keep Solo an indefatigable force for optimism. Instead, if William accepts more of Solo’s ministrations, it’s largely due to his passivity, not a fundamental change of heart. Meanwhile, Solo becomes more anxious and pessimistic, shedding some of that casual charm that captivated us in the opening. Neither executes that neat character arc that Hollywood tends to favor and that’s visible in Up and (500) Days of Summer.

Bahrani’s hatred of cliché obliges him to make his story events mundane and equivocal. As in Man Push Cart and Chop Shop, the plot emerges from variations in routine, a lesson well-taught by European festival cinema of the 1950s. But when you have a stubborn, taciturn character like William, and you’re restricted to another character’s range of knowledge, it’s hard to give the film a forward propulsion. You have a deadline, but no momentum. So plot dynamics arise from Solo’s relation to his wife and daughter, his career goals, and above all his investigation of William’s past–his search for what could drive the man to suicide. And this investigation turns on conveniently discovered clues.

Someday I must do a blog entry on tokens in narratives. Any plot of some complexity seems to need physical objects that encapsulate dramatic forces, spread out information, or become emotion-laden motifs. The photograph is probably the most traditional one, but notes, diaries, rings, and so on are useful too. In Goodbye Solo, William’s tokens move the drama of disclosure forward, and it’s possible to object to the film’s reliance on so many of them.

The problem Bahrani faces is that the film has to give us personal information about William while retaining tact and respect for characters’ integrity. For William to open up into a Tarantino-style confession would tear the movie apart; even a quiet moment of sobbing vulnerability is too indiscreet here. The film needs its tokens, however awkward they may seem as narrative devices, to keep faith with its people.

Staying a little outside the characters, allowing them to retain some private motives, is exactly what (500) Days of Summer doesn’t attempt. Bahrani’s discretion extends to the very last scene. The title becomes a line that someone should speak but doesn’t. Up till now, the quietly precise images have been shot by a camera locked down, but atop a mountain the camera leaves its tripod and supplies some mildly shaky imagery. And now it fits. It’s not just that the drama has reached an emotional pitch. The camera is simply buffeted by the wind. Once more Bahrani lets his world do its work.

You can read about our summer film-related travel here and here and here and here and here.

Overwhelmed by all the material on Pixar and Up, I merely point to two encyclopedic experts: the ever independent-minded Mike Barrier and the always-informative Bill Desowitz, who offers information on Pixar’s approach to 3-D here. For Ponyo background and an interview with Miyazaki, turn again to Bill D, here; he provides a transcript of a conversation between Miyazaki and John Lasseter here. A fat book of Miyazaki interviews and essays has just been published, and it includes some incendiary stuff, such as “Everything that Mr. Tezuka [Osamu, the ‘god of animation’] talked about or emphasized was wrong” (197).

The parentheses in (500) Days of Summer are explained by screenwriter Scott Neustadter at Jeff Goldsmith’s Creative Writing podcast.

Roger Ebert has reviewed nearly all these films and as always he has sensitive things to say, particularly on Goodbye Solo. He’s been championing Bahrani’s films for many years and he offers a warm career appreciation here.

Goodbye Solo.

Now leaving from platform 1

From a Facebook post by Tahereh

To all my friends:

What can I reply to Hossein? He’s pursuing me so avidly, but you know he isnt really a prime catch. No education, no house. If it werent for the earthquake, I wouldnt give him a second look. But he does interest me a little—he’s made me lose track of my lines so many times!

Oh no, now he’s chasing me across the field. What can I tell him? BRB!

DB here:

Many people in the film industry hold media studies in disdain, and often the feeling is mutual. Filmmakers recoil from the abstrusities of Big Theory, and academics often consider filmmakers gearheads (just before wagging their fingers and warning us about the Intentional Fallacy). But scholars like Rick Altman, John Caldwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin, and me, and younger folks like Patrick Keating and Ben Wright have been trying to study filmmakers’ creative choices in concrete ways. Some of us even ask filmmakers what they were trying to do.

So it’s heartening to see movement in the other direction. For quite a while academically trained filmmakers like James Schamus and Todd Haynes have brought ideas from their university studies into their films. Recently Reid Rosefelt composed an enlightening blog entry on Kathryn Bigelow’s intellectual side. Now some terms and ideas are being spread even more widely across the industry.

For example, in a recent Entertainment Weekly story about why women viewers like horror, we read:

One of the most consistent tropes of the genre is the character whom filmmakers call ”the final girl” — the survivor.

Actually, it was Carol Clover, scholar of horror movies and Scandinavian epics, who came up with the “final girl” nickname in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Going back to the EW sentence, you notice that academics helped popularize the term genre too, which you seldom find in Hollywood’s patter before the 1970s. And the very word trope smells of classrooms and chalkdust.

Even more striking is a recent Variety article entitled, “Transmedia Storytelling Is Future of Biz.” Peter Caranicas explains that it involves “developing a piece of intellectual property across multiple media platforms.” The Star Wars franchise is the major modern instance, as Caranicas explains.

What Lucas did went several steps beyond old-style character licensing and brand extensions. He created a unified body of work with an extensive backstory and mythology, and he determinedly guarded its canon [another academic term—DB] while simultaneously opening up peripheral parts of his universe to exploration by other contributors.

One of my former students assures me that Kristin and I used the term “transmedia” back in the 1990s, but we have no memory of doing so. More relevantly, Liz Rosenthal reminds us that Peter Greenaway was pushing the concept in 1993. “If the cinema intends to survive, it has to make a pact and a relationship with concepts of interactivity and it has to see itself as only part of a multimedia cultural adventure.”

In any case, the person who brought the concept of transmedia storytelling to the forefront of media studies, and thus industry parlance, was another Wisconsin student, Henry Jenkins. Henry has made the concept part of his broader research into how modern media connect with audiences, particularly fan audiences. In his 1992 essay on Twin Peaks, he was already exploring how fans used the still-emerging internet to respond to a range of ancillary texts around Lynch’s TV series. You can get a quick acquaintance with his most recent ideas in this 2007 blog essay. For me, his argument emerged most vividly in a talk he gave at Madison some years ago. The lecture became the chapter “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” in his book Convergence Culture. For his more recent thinking, you can check his current course syllabus, which includes reading and web references, in the 11 August entry here.

The platform-shifting that Caranicas describes is planned and executed at the creative end, moving the story world calculatedly across media. These, dubbed by Jenkins “commercial extensions,” differ from “grassroots extensions,” which are created by audience members without the permission, or even the knowledge, of the creators. The commercial extensions are what I’ll be considering here.

From aggregator Movie MMORPG:

Welcome to a sophisticated world teetering on the edge of decadence. Get hammered on Italian cocktails. Fight your way out of a hospital jammed with nymphos. Cheat on your wife. Seduce a married man. Wander through the streets and stare at gushing water. Have you got what it takes to survive a day in LaNotteCity? You’ll get hooked, since the endgame is always inconclusive!

As it’s currently discussed, transmedia storytelling has two uncontroversial components and one rare but intriguing one.

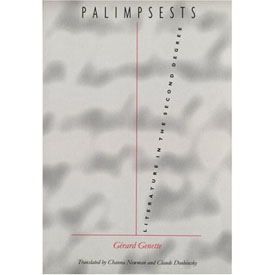

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

Novels and short stories feed off other novels and short stories. Obvious examples are parodies, pastiches, sequels, and continuations (sequels not written by the original author). Genette also considers what he calls the “transposition,” a very roomy category that’s of particular interest to us.

Transpositions are things like translations, rewritings, and literary adaptations, as when a novel becomes a play. A transposition also occurs when the original text is pruned or compressed, as in abridged versions of Don Quixote or Moby-Dick. At the other quantitative extreme is what Genette calls augmentation. Here, the derivative work expands the original, either in style (three sentences replace one) or narrative material (extra scenes or plots).

Yet another sort of transposition occurs when the story events in the original are rendered through alternative literary techniques. Charles Lamb retells Ulysses’ adventures in a different order than Homer does, and someone could rewrite the events of Madame Bovary in first person, from Charles’ point of view. When Genette was writing, he had to reach for some esoteric examples, but nowadays we have others. Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone (2001) retells Gone with the Wind from the point of view of a slave on Tara. The novel Wicked is a large-scale example, as is Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

All these examples of hypernarrative operate within a single medium. The second condition of transmedia storytelling is, of course, that it crosses media. Genette considers drama and written literature to be all part of the same medium, but if you don’t, then novels turned into plays, like Les Miserables, would count as transfers across media.

In this sense, transmedia storytelling is very, very old. The Bible, the Homeric epics, the Bhagvad-gita, and many other classic stories have been rendered in plays and the visual arts across centuries. There are paintings portraying episodes in mythology and Shakespeare plays. More recently, film, radio, and television have created their own versions of literary or dramatic or operatic works. The whole area of what we now call adaptation is a matter of stories passed among media.

What makes this traditional idea sexy? I think it’s a third, less common component that Henry has spotlighted. Some transmedia narratives create a more complex overall experience than that provided by any text alone. This can be accomplished by spreading characters and plot twists among the different texts. If you haven’t tracked the story world on different platforms, you have an imperfect grasp of it.

I can follow Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories well without seeing The Seven Percent Solution or The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. These pastiches/continuations are clearly side excursions, enjoyable or not in themselves and perhaps illuminating some aspects of the original tales. But according to Henry, we can’t appreciate the Matrix trilogy unless we understand that key story events have taken place in the videogame, the comic books, and the short films gathered in The Animatrix. The Kid in The Matrix Reloaded makes cryptic reference to finding Neo by fate, but only those who have watched the short devoted to him knows what that means. If Sherlock pastiches are parasites, the texts around The Matrix exist in symbiosis, giving as much as they take.

This strategy differentiates the new transmedia storytelling from your typical franchise. In most film franchises, the same characters play out their fixed roles in different movies, or comic books, or TV shows. You need not consume all to understand one. But Henry envisages the possibility of creating a whole that is greater than its parts, a vast narrative experience that doesn’t end when the book’s last page is turned or the theatre lights come up. His idea seems to be echoed in Will Wright’s suggestion:

It’s a fractal deployment of intellectual property. Instead of picking one format, you’re designing for one mega-platform. . . . We’ve been talking about this kind of synergy for years, but it’s finally happening.

Stimulating as this prospect is, it remains rare. The Matrix is perhaps the best example, but Henry suggests that it’s also an extreme instance: “For the casual consumer, The Matrix asked too much. For the hard-core fan, it provided too little” (p. 126). More common is a Genette-style transposition, in which the core text—usually the movie—is given offshoots and roundabouts that lead back to it. As I understand it, the Star Wars novels operate under the injunction that although they can take a story situation as the basis for a new plot, in the end that plot has to leave the films’ story arc unchanged. Similarly, websites with puzzles, games, clues, and other supplementary material tend to be subordinate to the film, planting hints and foreshadowings (The Blair Witch Project, Memento). Alternatively, the A. I. website provided a largely independent story world that impinged on the movie’s action only slightly.

The “immersive” ancillaries seem on the whole designed less to complete or complicate the film than to cement loyalty to the property, and even recruit fans to participate in marketing. It’s enhanced synergy, upgraded brand loyalty.

For the most part Hollywood is thinking pragmatically, adopting Lucas’ strategy of spinning off ancillaries in ways that respect the hardcore fans’ appreciation of the esoterica in the property. Caranicas quotes Jeff Gomez, an entrepreneur in transmedia storytelling, saying that for most of his clients “we make sure the universe of the film maintains its integrity as it’s expanded and implemented across multiple platforms.” It would seem to be a strategy of expanding and enriching fan following, and consequent purchases.

As best I can tell, then, in borrowing this academic idea, the industry is taking the radical edge off. But is that surprising?

Excerpt from www.ballsup.net

What a bloody week. Just now had a chance to update things. Fact is, it’s me last post. Luckily I let that cellphone drop and grabbed the satchel just before it fell into the Thames. Me and the crew are now packing for Bimini, ready for living large but in a rush becuz Big Chris may be looking for us. Hang on, must upload now, someone’s knocking at me d

Henry’s chapter in Convergence Culture grants that “relatively few, if any, franchises achieve the full aesthetic potential of transmedia storytelling—yet” (p. 97). Perhaps that hopeful “yet” will be fulfilled outside Hollywood? In the realm of the avant-garde, Matthew Barney has elaborated his own private mythology, dispersed among artifacts and hard-to-see films. In this he followed Joseph Beuys and Salvador Dalí. But you could argue that these artists really weren’t telling an overarching story. They were creating secular cults, full of arcana that only the pious initiates of Gallery Culture could grasp.

What about something more accessible? This month in Filmmaker magazine, Lance Weiler has suggested that indie filmmakers embrace the concept of transmedia storytelling (though he doesn’t use the term). Weiler argues that the explosion of digital technology has so transformed narrative that the filmmaker has to keep up. Instead of creating a script, with its genre formulas and three-act layout, the filmmaker should generate a bible, which plots an ensemble of characters and events that spills across film, websites, mobile communication, Twitter, gaming, and other platforms. The filmmaker designs “timelines, interaction trees, and flow charts” as well as “story bridges that provide seamless flow across devices and screens.”

Weiler doesn’t offer any specific examples apart from his Head Trauma, a horror feature accompanied by an alternate reality game that involved mobile and online access. You can watch his account of the “evolution of storytelling” here, where he and Ted Hope speculate about transmedia storytelling as offering economic help to filmmakers, reclaiming authorship from corporations, and promoting new relations with the audience.

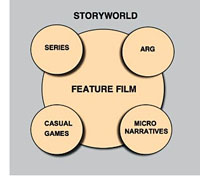

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

We should welcome experimentation, so I wish Hope, Weiler, and other creators well. But I think we ought to recognize some problems with expanding story worlds in these directions.

For one thing, most Hollywood and indie films aren’t particularly good. Perhaps it’s best to let most storyworlds molder away. Does every horror movie need a zigzag trail of web pages? Do you want a diary of Daredevil’s down time? Do you want to look at the Flickr page of the family in Little Miss Sunshine? Do you want to receive Tweets from Juno? Pursued to the max, transmedia storytelling could be as alternately dull and maddening as your own life.

Sure, somebody might go for it. Kristin points out, though, that people who would be motivated to follow up on all the transmedia bits of a spreadeagled narrative are people who would identify themselves as part of a fandom. There aren’t that many films/franchises that generate profoundly devoted fans on a large scale: The Matrix, Twilight, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Star Trek, maybe The Prisoner. These items are a tiny portion of the total number of films and TV series produced. It’s hard to imagine an ordinary feature, let alone an independent film, being able to motivate people to track down all these tributary narratives. There could be a lot of expensive flops if people tried to promote such things.

Consider a deeper point. Transmedia storytelling in the radical sense is posited as an active, participatory experience. Henry suggests that fans will race home from the multiplex to study up on iconography in The Matrix. Weiler’s article is accompanied by a hierarchy that lists “layers of interactivity.” The most superficial is “Passive Viewing,” defined as “Sit back and watch.” (Here Weiler parts company with Henry, who doesn’t consider ordinary viewing passive.) Further along are layers involving social networking, playing games, discussing or interacting with characters, finding hidden content, and even creating elements of the story world.

But it seems to me that film viewing is already an active, participatory experience. It requires attention, a degree of concentration, memory, anticipation, and a host of story-understanding skills. Even the simplest story gears up our minds. We may not notice this happening because our skills are so well-practiced; but skills they are. More complicated stories demand that we play a sort of mental game with the film. Trying to guess Hitchcock or Buñuel’s next twist can engross you deeply. And the very genre of puzzle films trades on brain strain, demanding that the film be watched many times (buy the DVD) for its narrational stratagems to be exposed. Films are interactive in the way a board game is: each move blocks certain possibilities, another anticipates what you’re going to do (mentally).

Moreover, how the ancillary texts add to the film is a crucial matter. No narrative is absolutely complete; the whole of any tale is never told. At the least, some intervals of time go missing, characters drift in and out of our ken, and things happen offscreen. Henry Jenkins suggests that gaps in the core text can be filled by the ancillary texts generated by fan fiction or the creators. But many films thrive by virtue of their gaps. In Psycho, just when did Marion decide to steal the bank’s money? There are the open endings, which leave the story action suspended. There are the uncertainties about motivation. In Anatomy of a Murder, did Lieutenant Manion kill his wife’s rapist in cold blood? Likewise, being locked to a certain character’s range of knowledge is the source of powerful emotional effects. We want to make the discoveries along with the character, be he Philip Marlowe or Travis Bickle.

The human imagination abhors a vacuum, I suppose, but many art works exploit that impulse by letting us play with alternative hypotheses about causes and outcomes. We don’t need the creators to close those hypotheses down. Indeed, you can argue that one of the contributions of independent film has been the possibility of pushing the audience toward accepting plots that don’t fit clear-cut norms. That innovation shrinks if we can run home to get background material online. By following the franchise logic, indie films risk giving up mystery.

At this point someone usually says that interactive storytelling allows the filmmaker to surrender some control to the viewer, who is empowered to choose her own adventure. This notion is worth a long blog entry in itself, so I’ll simply assert without proof: Storytelling is crucially all about control. It sometimes obliges the viewer to take adventures she could not imagine. Storytelling is artistic tyranny, and not always benevolent.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

In between opening and closing, the order in which we get story information is crucial to our experience of the story world. Suspense, curiosity, surprise, and concern for characters—all are created by the sequencing of story action programmed into the movie. It’s significant, I think, that proponents of hardcore multiplatform storytelling don’t tend to describe the ups and downs of that experience across the narrative. The meanderings of multimedia browsing can’t be described with the confidence we can ascribe to a film’s developing organization. Facing multiple points of access, no two consumers are likely to encounter story information in the same order. If I start a novel at chapter one, and you start it at chapter ten, we simply haven’t experienced the art work the same way. This isn’t to say, of course, that each of us has an identical experience of a movie. It’s just that our individual experiences of the film overlap to an extent that allows us to talk about the patterning of the story under our eyes.

In correspondence with me, Henry suggests that transmedia storytelling may work best with television because of the serialized format; different people hop aboard at different points. I’d add that television’s installment-based storytelling, operating in the lived time of the audience, allows time for viewers to explore or create media offshoots. The installment-based nature of serial TV poses intriguing aesthetic problems of continuity, coherence, and memory. (See Jason Mittell’s essay on this matter.) For films, however, which are typically designed to be consumed in one sitting, multiple points of entry will tend to make plot patterns less clearly profiled.

If transmedia storytelling is difficult to apprehend for the viewer, it also makes critical analysis and evaluation much more difficult. How might we analyze overarching patterns of multiplatform plotting in The Matrix? True, one can itemize the inputs and decipher the citations, but it’s very hard to show how they work together, how they unfold, what it all adds up to—except to note that different people will encounter information bits at different times and with different states of knowledge.

Gap-filling isn’t the only rationale for spreading the story across platforms, of course. Parallel worlds can be built, secondary characters can be promoted, the story can be presented through a minor character’s eyes. If these ancillary stories become not parasitic but symbiotic, we expect them to engage us on their own terms, and this requires creativity of an extraordinarily high order.

Henry Jenkins suggests that for big-budget projects, this means finding unusually gifted collaborators. In the indie sector, the obstacles are even more considerable. Whether the result is Wendy and Lucy or Goodbye Solo, creating a first-rate feature-length movie takes tremendous talent, sweat, and resourcefulness. It is immensely harder to create a story universe that sustains the same intensity and quality across platforms. True, you can sprinkle clues and cryptic references among websites and YouTube shorts. The formulas of genre (horror, mystery) help you generate shock effects and mystification in teaser trailers. Appeal to stock characterization helps you mount a “realistic” Second Life life. But building a vast, sturdy world teeming with distinctive characters, unpredictable plotting, and human resonance is an immense task.

We await our multimedia Balzac. In the meantime, maybe indie filmmakers should settle for trying to be Chekhov.

http://tinyurl.com/scarkiller

Debbie, sorry 2 hav left SOOOO suddenlike. am @ Gila flats = cactus + varmnts. LOL with Blankethead!!! :-/

Uncl Ethan

Thanks to Henry Jenkins for comments on this entry. He recommends that interested readers have a look at Geoffrey Long’s 2007 MA thesis on the Jim Henson company, available, along with many other MIT projects, here. Thanks also to Kristin and Jeff Smith for suggestions, and to Janet Staiger for correcting my memory and calling attention to Dennis Bound’s book on “transmedia poetics” as applied to Perry Mason.

PS 11 Sept: Henry Jenkins has responded to my entry, with the first of three installments starting here.

Getting real

Art is not reality; one of the damned things is enough.

Attributed to Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and others.

DB here, with another followup to Ebertfest:

Ebertfest, once known as the Overlooked Film Festival, has always been keen to support American independent filmmaking. In previous incarnations, Roger spotlighted Junebug, Tarnation, and other movies that flew below the multiplex radar. This year’s crop was especially ripe. Besides The Fall and Sita Sings the Blues, there were important documentaries like Begging Naked and Trouble the Water. In particular, two fiction features set me thinking about types of independent storytelling and how they might be considered realistic.

The river is wide

Roger noted that when he first saw Frozen River, he wanted to bring it to his festival, but then it became the very opposite of an overlooked movie. It has grossed $4.3 million worldwide, a very healthy amount for a small-budget film without big stars. It won eleven national awards and was nominated for fourteen others, including a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. By now, you’ve probably seen it. I had been away during its Madison run, so I was happy to catch up with it.

“You have five minutes to show the audience you’re in charge,” commented director Courtney Hunt in the Q & A, and her film follows that advice. Seconds into Frozen River, we hit a crisis. Ray finds that her no-good husband has grabbed their savings and taken off to gamble, even as she waits for the delivery of their new prefab home. What begins as a drama of pursuit, with Ray trying to track down her husband, turns into a blocked situation. He’s gone and she has to not only pay off their mortgage but also keep her two sons going, counting on their school lunches to offset their domestic meals of popcorn and Tang.

Drama is about choices, and good drama is about bad choices. Ray has clearly made her share of mistakes—addictive mate, kids she can’t support, a bigscreen TV she can’t afford—and the plot shows her making the biggest of all. To scrape together money she agrees to transport illegal immigrants from Canada to upstate New York, driving across the frozen St. Lawrence. She casts her lot with Lila Littlewolf, a Native American with her own bad choices, and their common fate creates a series of parallels about motherhood that are resolved through Ray’s final sacrifice. The film also activates some current concerns about immigration, racism, and the problems shared by poor whites and ethnic minorities.

Resolutely unHollywood in its setting, theme, and characters—deglamorized women, especially—Frozen River still adheres to classical script structure. We have characters with goals, encountering obstacles and entering into conflicts, and the turning points come at the standard junctures. The ending is a resolution, although not an entirely happy one. In the course of the plot, suspense is built up at many points. Will Ray and Lila be caught by the state troopers who grimly monitor their comings and goings? What will become of that abandoned baby? The film is a sturdy example of how classic principles of construction can be applied to subject matter that is worlds away from our prototype of Hollywood filmmaking.

Neo-neo and all that

Ramin Bahrani’s Chop Shop, which I was also just catching up with, offers another flavor of independent dramaturgy. Roger has been a staunch supporter of Ramin’s films since Man Push Cart, and he has declared him “the new great American director.”

Bahrani has mastered a somewhat different narrative tradition than the crisis-driven plotting of Frozen River. “Neo-neorealism,” A. O. Scott has called it, linking Goodbye Solo to Wendy and Lucy, Treeless Mountain, Old Joy, and other films that offer us an “escape from escapism.” Now, Scott suggests, American cinema is having its delayed Neorealist moment. Richard Brody offers some useful, sometimes scornful, qualifications of Scott’s conjecture, reminding us of the urban dramas of the 1940s and the rise of Method acting. Scott has replied, claiming that their dispute essentially depends on their differing tastes in movies.

Here’s my $.02. “Neorealism” isn’t a cinematic essence floating from place to place and settling in when times demand it. The term, like the films it labels, emerged under particular circumstances, and it’s hard to transfer the label to other conditions. Moreover, there are many problems just with applying the term to Italian cinema, since it tends to cover not only the purest cases, like Bicycle Thieves, but also more mixed ones like the historical drama The Mill on the Po.

Still, because postwar Italian cinema had a big influence on other national cinemas, we have a prototype of The Italian Neorealist Movie. The filmmaker focuses on the lives of working people. He emphasizes their daily routines and travails. The film will be shot on location (at least in the exteriors) and may use nonactors in some or all roles. Bazin pointed out that we’re likely to find an elliptical or unresolved plot. It’s also very likely that we’ll see washlines and women in slips.

Why not just call this an Italian variant of that broad tradition of naturalism or verismo or “working-class realism” that we find in many national cinemas? In France there was the work of Andre Antoine (e.g., La Terre, 1921) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidele (1923) and his lyrical barge romance La Belle Nivernaise (1923). More famous are Renoir’s Toni (1935) and The Lower Depths (1936). (Recall that Visconti was Renoir’s assistant on A Day in the Country, 1936.) In Italy, there were harbingers too, not only the famous ones like Four Steps in the Clouds (1942) but also the charming Treno Popolare (1933). And Japan gave us many instances in the 1930s, notably Ozu’s Inn in Tokyo (1935) and The Only Son (1936).

Realer than real

On an Ebertfest panel Ramin Bahrani argued for a realist aesthetic. “Most people in movies never seem to pay rent or keep track of how often they can eat out . . . [Ordinary people] have day-to-day struggles; they ask how to survive.” That’s to say that a realistic work is distinguished primarily by its subject matter, the social milieu it presents. Bahrani also mentioned that some plot devices are unrealistic. Criticizing Slumdog Millionaire, he remarked: “My world doesn’t end in a Hollywood fantasy.” He didn’t deny the need for a dramatic structure, but he did insist on avoiding “obvious plot points like ‘He crossed the door and can’t go back.’”

This leads me to another $.02 contribution. I’m reluctant to contrast realism with something like artifice or formula. To me, realism comes in many varieties, but none escapes artifice. All realisms I know rely on conventions shaped by tradition.

For example, Chop Shop shows us a slice of life that most of us don’t know, the world of garages and salvage yards clustered around Shea Stadium. Such a low-end milieu is a convention of literary naturalism (Zola, Gorki). In this tradition, an artwork acknowledging the lives of the poor gains a dose of realism that, say, a novel by P. G. Wodehouse or a play by Noël Coward will lack. Some critics complained that when Rossellini’s Europa 51 and Voyage to Italy presented upper-class life, he left Neorealism behind.

There seem to me other conventions at work in Chop Shop. In one garage we find a boy, Alejandro, who has two goals. He wants to set up a food van that will sell meals to the men working in the neighborhood, and he wants to keep his sister Isamar safe from bad companions. Goal-driven plotting is central to Hollywood dramaturgy, as it is to much literary realism (e.g., An American Tragedy). It’s true that in real life people often form goals, but many do not, and those who do seldom come to a state of heightened awareness in the time frame typical of a movie’s plot. Alejandro fails to achieve one goal but partially achieves another, so we have an open, somewhat ambivalent ending—another convention of realist storytelling and modern cinema (especially after Neorealism). Life goes on, as we, and many movies, often say.

Instead of following a crisis structure, as Frozen River does, Chop Shop presents what we might call “threads of routine.” Most scenes consist of ordinary activities: the work of the garage, Alejandro’s sales of candy and DVDs, opening and closing the shop, Alejandro watching from the window of his room. But these vignettes aren’t sheer repetitions. They vary as Alejandro encounters progress or setbacks with respect to his goals. Most of the routines establish a backdrop against which moments of change and conflict will stand out.

Building a movie out of routines can also make convenient coincidences seem plausible. For instance, dramas have always relied on accidental discoveries of key information—the overheard conversation, the token that betrays what’s really happening. In Chop Shop, Ale and his pal Carlos discover that Isamar has become one of the hookers who service men in the cab of a tractor-trailer. They might have discovered this, as in life, by simply wandering by the spot on a single occasion. Instead, Bahrani’s script motivates their discovery by explaining that they habitually spy on the truck assignations. “Let’s go to the truck stop and see some whores.” Planting information in scenes of everyday activities seems more natural than giving it special emphasis at a moment of crisis. In two later scenes, the truck-stop becomes an arena for conflict, so Ale’s initial discovery motivates his later actions.

As for plot points, Chop Shop has them. (At about 15 minutes, the zone of the Inciting Incident, Ale declares his intention to buy the van. At about 30 minutes he discovers that Isamar is turning to prostitution.) Likewise, the threaded routines yield poetic motifs, such as the pigeons that are carefully established early in the film. Bahrani’s plotting is meticulous, and it highlights the paradox of realism: It takes effort and calculation to “capture reality.” De Sica was said to have endlessly rehearsed the boy in Bicycle Thieves.

What gives the film a more episodic organization than Frozen River, I think, and what gives it a greater sense of “dailiness,” is that it lacks deadlines. There’s relatively little time pressure on the action, except for Ale’s sense that he’s getting close to having enough money for the van. Chop Shop’s refusal of Hollywood’s ticking clock seems to me to confirm the observation, made by Geoff Andrew and J. J. Murphy, that in some respects American indie film is located midway between classical narrative cinema and “art cinema.”

The threads-of-routine pattern can be harnessed to character-driven drama, as in Chop Shop, but it can also be more opaque or minimalist. During at least half of Elia Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance, we watch anonymous characters go through routines, but instead of revealing their psychological drives, the scenes show the people overwhelmed by their surroundings. Narrative development is charted through changes in the spaces that the figures inhabit and vacate. The result is a “surreal realism” that evokes the anxieties of Magritte or de Chirico.

To say that realist traditions rely on conventions doesn’t make them less worthwhile. Chop Shops seems to me quite a good film. Nor would I deny that realist conventions do capture some aspects of real life. Both the crisis structure and the threads-of-routines structure can be taken as realistic. Sometimes our lives are in crisis, and at other times we do just plod along. But more stylized narrative forms can capture important aspects of reality too. The Searchers, a work of high artifice, renders a portrait of a self-destructive racist that many of us recognize in the world outside the movie house. Has any film better caught the adolescent yearning for romantic love and family stability than Meet Me in St. Louis?

The problem comes when we think that only one variant of realism can lay claim to validity, let alone beauty. Sometimes fidelity takes a back seat to vivacity. In Roy Andersson’s films, everyday nuisances like checking in to a plane flight or waiting in a clinic are inflated to grotesque, gargantuan proportions, becoming torments in a vision of hell. Like all caricatures, the exaggeration captures something true.

Comparing Wilkie Collins and Dickens, T. S. Eliot notes that both writers give us vivid characters. Collins’ characters are “painstakingly coherent and life-like,” terms of praise that we could assign to Bahrani’s films as well. But, Eliot adds, “Dickens’ characters are real because there is no one like them.”

What was Neorealism? Some of André Bazin’s invaluable essays on the subject can be found in What Is Cinema? vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). Kristin and I offer a survey of some historical factors in Chapter 16 of Film History: An Introduction. (Go here for a little bibliography.) For more on art cinema and its commitments to realism and open endings, see my essay, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 151-169. On American indies’ borrowing of art-cinema conventions, see Geoff King, American Independent Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005) and J. J. Murphy, Me and You and Memento and Fargo (New York: Continuum, 2007). J.J. also has a blog entry on Chop Shop here. The quotations from T. S. Eliot come from “Wilkie Collins and Dickens,” Selected Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1950), 410-411.

Songs from the Second Floor (Roy Andersson, 2000).