Archive for the 'Independent American film' Category

Do sell us shorts

Kristin here—

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a single theater playing all five nominees for the best-picture Oscar. It’s happening now at the six-screen Sundance Cinemas here in Madison, plus they’ve got The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (nominated for director, cinematography, adapted screenplay, and editing) and Persepolis (animated-feature nominee). The latter is very impressive, and I think it would win in an ordinary year, but probably not when it’s up against Ratatouille.

[February 9. That outcome seems even more likely now. Last night Ratatouille won nine Annie Awards, prizes given out by the professional animation community. In the 35 years of those awards’ existence, only once has the top animated feature prize not gone to the film that went on to win the best animated film Oscar. Pixar’s accompanying short, Your Friend the Rat, won best short subject. It’s not eligible for an Oscar, since it was a supplement on the Ratatouille DVD and not shown theatrically.]

Films like these get widely seen, obviously. An awful lot of films, though, get nominated for Oscars that far fewer people will see. How many people fill out their office Oscar pool ballots knowing anything about the short animated and live-action films? Some you can track down online or on TV (HBO, Sundance, the IFC, and so on), but viewing them all would be difficult.

For three years now, however, Magnolia Pictures has been packaging the films in those two categories into a single program that goes out to theaters and then onto DVD. Magnolia is a small independent distributor, best known perhaps for its documentaries, including Enron: Smartest Guys in the Room and Capturing the Friedmans and for its imports like Ong Bak and The World’s Fastest Indian.

This year’s program, “The 2007 Academy Award Nominated Shorts,” is listed on the company’s website as playing in 80 theaters, though perhaps that number will rise. Many of the runs (including the one at our Sundance Cinemas) start on February 15, and others are scheduled from then on into April.

Thanks to Sarah Simonds, manager at Sundance, I was able to get an early look at the ten films on the program.

As one might predict, the range of quality is greater in the live-action films than in the animated ones. I’m not sure why that would be predictable, but I have my suspicions. There’s not much of a theatrical market for live-action shorts, which mainly get seen at festivals and on TV. They tend to be portfolio films, made by people trying to attract attention and move up to features. Hence they more often come from beginners. Animators who don’t want to work their way up through big studios—and who stand little chance of ever directing a major animated feature—or who simply value their independence may stick with shorts.

Another factor working in favor of animation is that it’s a medium that demands the detailed planning of literally every frame. No improvisation, no casual shooting in real locales, no direct sound. All in all, I think that if I were an Academy member, I’d have more trouble making a decision in the animated-shorts category.

Real, Live People

In the live-action category there’s no doubt that I would vote for The Tonto Woman, a UK short directed by Daniel Barber from an Elmore Leonard short story. Remarkably, Barber had mainly directed TV commercials before embarking on this, his first 35mm short, as a way of breaking into the film industry. He produced and funded it himself, with a ten-day shoot in Spain using locations and standing sets that had figured in such films as A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

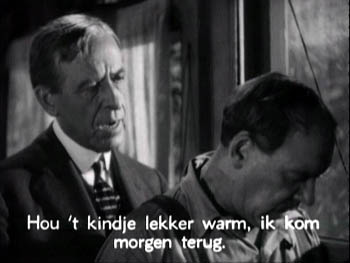

The result might be described as The Piano meets There Will Be Blood. A cattle rustler (well played by Anthony Quinn’s son Francesco) encounters a rich man’s wife (Charlotte Asprey) who is living in enforced seclusion after having been kidnapped and held for eleven years by Mojave Indians (image above). The film has landscapes with the epic quality of both There Will Be Blood and No Country for Old Men, and its drama has the depth of a feature film without feeling rushed in its 35 minutes.

Leonard’s website has a press release giving more details, as well as a profile of Berber. The latter suggests that the director has been contacted by people within the film industry. All I can say is, fund this man immediately. I definitely want to see what he could do at feature length.

David has written quite a bit about the lively contemporary Danish cinema, including two entries on this blog, here and here. The country continues to be on a filmic roll in terms of Oscar nominations, with the short At Night being the one I’d vote if I were an Academy member and weren’t already voting for The Tonto Woman. It’s directed by Christian E. Christiansen and produced by Zentropa with support from the Danish Film Institute.

The subject matter sounds like the sort of thing that would ordinarily make me run the other way: three very young women with cancer bonding in the hospital ward they share. But the film avoids the touchy-feely clichés that so easily could sink such a project (except for a conventional Polaroid-photo montage of their little New Year’s party). It’s not just a sick-women’s-solidarity picture. One does come to care about these three and to understand how their illnesses make them better able to communicate with each other than with their families. It manages to pack a considerable emotional impact into forty minutes. Again, here is someone who could probably direct a fine feature film—and, given the current strength of the country’s industry, may well get the chance.

Tanghi Argentini is a charming comedy from Flemish director Guido Thys, dealing with an office worker who asks a colleague to teach him how to tango to impress a woman he has met on the internet. It combines a clever concept with a surprise twist at the end that works so well in both the short-story and short-film format. It’s entertaining but not so unusual or substantial that I would think of it as Oscar-worthy.

The two other films, France’s Le Mozart des Pickpockets (director/writer/actor Philippe Pollet-Villard) and Italy’s The Substitute (director Andrea Jublin), though both amusing, seemed surprisingly lightweight and conventional to have received nominations.

Puppets and Pictures

Trying to decide which of these animated shorts I would vote for is more difficult. Each is well-executed, entertaining, and imaginative. I tried thinking which I would want to watch again, which I would recommend to friends.

By those standards, there are again two stand-outs for me. I’d ultimately opt for Même les pigeons vont au paradis (Even Pigeons Go to Heaven), a French puppet film by Samuel Tourneux. It’s about a priest who attempts to sell a heaven-simulating machine to a miserly peasant about to be visited by the Grim Reaper. It’s fast-paced, very funny, and beautifully detailed in its depictions of the characters and settings. It’s not claymation, but it has some of the polish and wit of Aardman shorts.

My close second choice would be a very different sort of film, My Love, from Russia, directed by Alexander Petrov. It’s a pretty, lyrical tale of a fifteen-year-old boy’s idealistic yearnings after a pretty servant girl and a more glamorous and mysterious woman who lives next door. The animation is impressionistic and shimmering, with constantly added brushstrokes transforming the compositions. Its visual style is derived from nineteenth-century Russian realist painting, especially that of Ilya Repin.

My close second choice would be a very different sort of film, My Love, from Russia, directed by Alexander Petrov. It’s a pretty, lyrical tale of a fifteen-year-old boy’s idealistic yearnings after a pretty servant girl and a more glamorous and mysterious woman who lives next door. The animation is impressionistic and shimmering, with constantly added brushstrokes transforming the compositions. Its visual style is derived from nineteenth-century Russian realist painting, especially that of Ilya Repin.

Suzie Templeton animating the Duck for Peter & the Wolf*

I suspect the Oscar winner might well be Peter & the Wolf, a British-Polish co-production that illustrates the classic Sergei Prokofiev tone poem. It was directed by Suzie Templeton and made at the Se-ma-for Studios in Łódź. There’s no doubt that it’s an impressive item, with elaborate miniature studio sets that could pass for real landscapes, precise and amusing puppets, and a mind-boggling frame-by-frame manipulation of furry puppets that leaves nary a ripple in their hair. (The photo above hints at how the latter feat was accomplished.) Still, the appeal of the original music is its evocation of events in our mind’s eye, and for me the literal playing out of those events at times carried a faint air of tedium. It’s the sort of prestige project that one can imagine a lot of Academy members loving.

The same cannot be said for the edgier I Met The Walrus, from Canada. It’s derived from an existing soundtrack, a tape-recording made by a 14-year-old Jerry Levitan when he snuck into John Lennon’s hotel room and interviewed him. Now, many years later, director Josh Raskin has created an animated image track to accompany it. It’s a clever idea, but to me the illustrations of Lennon’s words soon became a bit too literal, and I found myself thinking that the animation was Terry Gilliam (in his Monty Python days, that is) meets Yellow Submarine meets Max Ernst collage-novel.

The same cannot be said for the edgier I Met The Walrus, from Canada. It’s derived from an existing soundtrack, a tape-recording made by a 14-year-old Jerry Levitan when he snuck into John Lennon’s hotel room and interviewed him. Now, many years later, director Josh Raskin has created an animated image track to accompany it. It’s a clever idea, but to me the illustrations of Lennon’s words soon became a bit too literal, and I found myself thinking that the animation was Terry Gilliam (in his Monty Python days, that is) meets Yellow Submarine meets Max Ernst collage-novel.

I’m very much of two minds about Madame Tutli Putli, the seemingly inevitable entry from the National Film Board of Canada (directed by Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerborski). A puppet film four years in production, it is an extraordinary technical accomplishment. It deals with a mousey woman who takes a train journey that confronts her with bizarre and ultimately threatening events. The grim tone and grubby puppets and objects reminded me of Jan Svankmajer’s work.

The most disturbing thing about the images, however, is not the subject matter but the creepily realistic eyes. To me it was obvious that real eyes had been superimposed onto the puppets’ faces. Investigating how this had been done, I found this brief making-of demonstration on YouTube, which indeed revealed the main character to be a puppet with blank areas where the eyes would be. Looking further, I learned that the special effects were done by painter/animator Jason Walker, who devised a complicated process to coordinate the photographed eyes with the animation. Some demonstrations of that process are available here, and there is an interview with him here.

There’s no doubt that the technique is unnerving, and yet at the same time it’s distracting (if one notices it). Is it “fair”? Of course people have been combining live action and animation in various ways since the 1910s. Yet superimposing photographed elements in such a way as to make them appear to be part of the animation almost seems like cheating. Here one would be tempted to marvel at how skillfully the animators had simulated human eyes—a notoriously difficult subject to capture realistically. I suppose for many viewers the eyes and the rest of the image would blend seamlessly and not prove distracting. For me, it didn’t quite work.

Overall, the program is undoubtedly worth seeing on the big screen.

As to the previous two programs of Oscar nominees, see here for the list of 2005 shorts and here for the DVD; see here for the 2006 list and here for the DVD.

*The production image from Peter & the Wolf derives from a making-of short on the British release of the German-made DVD (from Arthaus Musik), which now seems to be out of print.

Beyond praise: DVD supplements that really tell you something

Filming The Da Vinci Code in the Louvre.

Kristin here—

In the 8th edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added a feature, “Recommended DVD Supplements.” Most chapters end with one of these, which contains information about relevant supplements that might be useful to teachers and students. Filmgoers outside the classroom might find them helpful as well.

As we all know too well, many DVD supplements consist largely of interviews with the main cast and crew members in which they praise each other. (“I don’t know how we could have made this movie without _______. She was perfect for that part.” “We were lucky to be working with a director who’s a genius.”) Not very interesting. We try to sort through and find supplements where the filmmakers actually talk in an informative and entertaining way about how they went about their work.

Obviously many DVDs have come out since we finished our last round of revisions, so we plan to use this blog as a means of occasionally updating our recommendations. Your suggestions about especially informative supplements are welcome.

King Kong (Deluxe Extended Edition, Universal)

In Film Art 8, I recommended the Production Diaries Peter Jackson put together for King Kong, since they cover (albeit briefly) a lot of topics that few supplements tackle. One day’s diary entry is devoted entirely to clapperboards! In the extended King Kong DVD, some of the additional supplements also deal with topics that most DVD’s extras bypass.

In relation to the section on settings in the Mise-en-scene chapter, for instance, you might look at “New York, New Zealand” (23 minutes). While most descriptions of CGI talk about how it is used to make monsters or crowds, this supplement discusses how the creation of settings can depend on digital imagery (above). During the fairly lengthy (42 minutes) documentary, “Pre-Production: The Return of Kong,” there is a discussion of what a First Assistant Director does during during this phase of production (40 minutes in). How often do you run across that? It could be used in conjunction with our layout of production roles in Chapter 1.

The 30-minute “Return to Skull Island” section goes into miniatures, matte paintings, and green-screen work—things that are often featured in supplements. This one also covers a less familiar technology, digital doubles.

Far from Heaven (Universal)

Supplements that examine a single scene, technique by technique, are pretty rare. One of the supplements on the Far from Heaven DVD does so in a useful way. The track originated as a documentary, “Anatomy of a Scene,” produced by the Sundance Channel (27 minutes). The analysis covers the production design and costumes, cinematography, acting, editing, and music. At the end, the completed scene is shown. The other large supplement on the disc, “The Making of Far from Heaven,” discusses the filmmakers’ attempts to replicate a 1950s look. It’s rather bland, with a little on style, a little on ideology, and a lot of mutual praise.

The Da Vinci Code (Sony; all editions have the supplements)

The DVD of The Da Vinci Code has two useful supplements. “Magical Places” (16 minutes) is an excellent demonstration on the logistics of going on location: permissions needed, technical challenges (such as lighting real interiors), and the substitution of one real building for another. Students will gain an awareness that even in real locales, filming doesn’t mean just going out, aiming a camera, and shooting stuff.

The second, “Filmmakers’ Journey Part One” (24.5 minutes) is not as good but still interesting. It could be used in conjunction with our Chapter 3, “Narrative as a Formal System,” which is rather hard to find relevant supplements for. There is discussion of character, timing, and rhythm. One passage that is particularly good for showing how filmmakers think about the form of films comes in a segment on the introduction of a major new character (Sir Lee Teabing) fully halfway through the film. Moreover, as director Ron Howard says, the Chateau Villette scene in question is a “high-wire act,” with a great deal of exposition suddenly brought into the middle of what has largely been an action-filled chase film. There is also discussion of the film’s series of journeys: “There was this sort of classic structure that we were working with.” It’s a pattern we discuss in Chapter 3. If nothing else, this supplement might convince students that their textbook’s authors are not just making up these terms to bedevil them!

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest ( Disney, 2-disc Special Edition)

Unexpectedly, one of the best sets of supplements I’ve seen lately accompanies Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. It’s a film that I mildly enjoyed watching, but I liked the making-of documentaries more. For one thing, the style is unusually low-key and lacks the chat about how wonderful everyone and everything was.

“Charting the Return” (about 26 minutes), for example, follows the stages of pre-production not just through interviews but also via a fly-on-the-wall presence of the camera at meetings and discussions. Often the people onscreen are not being interviewed but are actually at work, talking to each other. We see scripting, location scouting, design, and scheduling. Problems with deadlines and budgets are discussed rather than glossed over. The candor makes for a surprisingly entertaining and informative little movie. The same is true for “According to Plan” (60 minutes), which covers principal photography. Crew members delight in the beautiful Caribbean locales–but also complain about the heat, humidity, tides, rocking boats, and roads too small for equipment trucks. It’s one of the few accounts I’ve seen that suggests both the joys and the frustrations of real filmmaking.

Unless you’re really, really interested in costuming—or in ogling Jack Sparrow—the “Captain Jack: From Head to Toe” is frivolous. The “Mastering the Blade” segment can be skipped as well.

“Meet Davy Jones” (about 12 minutes) describes an important development in motion-capture technology for creating CGI characters. “Image-based motion capture” can extract mocap markers from a two-dimensional image (e.g., a shot of an actor performing on a stage) and make it three-dimensional. It can then be manipulated and placed back in the shot. In a discussion of modern special effects, this supplement might usefully be compared with the ones about the creation of Gollum in the Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers extended DVD set. The “Creating the Kraken” film (10 minutes) explains well how practical and CG special-effects are blended.

Filming as the tide covers the island used as a location.

You can skip the “Fly on the Set: The Bone Cage” segment, which is a skimpy four minutes on blue-screen special effects and the use of multiple cameras. OK, but this topic is covered more thoroughly on other films’ supplementary discs. Beware of “Jerry Bruckheimer: A Producer’s Photo Diary.” Bruckheimer makes up for all the compliments to director, cast and crew that were left out of the other supplements in this mercifully brief (5 minutes) track.

Unfortunately, some of the best recent films have come out on DVD with no supplements to speak of. When will we see some extras-laden editions of Cars and Zodiac?

[September 24: Film critic Kent Jones tells us that a deluxe DVD edition of Zodiac is coming out in the near future.]

1525 big thumbs up

Kristin here—

David and I just got back from Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. It’s been held under the auspices of the University of Illinois, Roger’s alma mater, in late April for nine years now. This year the event was front-page news because our irrepressible host attended the event while recovering from surgery for salivary-gland cancer and complications last summer.

David and I just got back from Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. It’s been held under the auspices of the University of Illinois, Roger’s alma mater, in late April for nine years now. This year the event was front-page news because our irrepressible host attended the event while recovering from surgery for salivary-gland cancer and complications last summer.

Roger’s features have changed somewhat and he faces further surgery and rehabilitation. Yet the man’s enthusiasm for movies and movie people has not waned. Most of the audience for Ebertfest (as it will officially be called starting next year) are regulars, and the standing ovations that greeted Roger and his wife Chaz show that the enthusiasm and affection are mutual. For more coverage, go here and here. For the official photoblog, with lots of neat pictures, go here.

If anything, Ebertfest audiences seemed even more cheerful and energetic than usual, happy that Roger has been so determined to avoid canceling this year’s event.

David and I have fond memories of Roger’s last visit to the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2006. There he introduced a restored print of Laura, held a signing at a local bookstore, and appeared at other screenings. People passing him on the street called out, “Hi, Roger,” as if he were an old friend. He graciously allowed me to interview him on the subject of press junkets for my chapter on marketing in The Frodo Franchise. There’s no way just to look up the history of junkets. No one has written one. But Roger is a primary document, having been attending them on and off since the 1960s. I learned a lot from our talk.

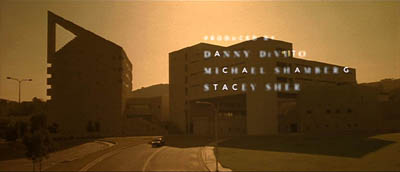

We drove down from Madison to Urbana-Champaign on Wednesday, David attending for the fourth year and I for the third. The opening film that evening was Gattaca (1997). With tepid reviews and box-office on its original release, Gattaca definitely counts as an overlooked film. Shown in an excellent print on the giant screen of the vintage Virginia movie palace, the cinematography was stunning and the story absorbing. Not an utter masterpiece, perhaps, but a very good film that deserved revival. As usual, people came from all over America to pack into the restored 1525-seat venue.

Now we’re back…and doing a summary blog. We had little time at the festival, and during our last day the web service at our lodgings conked out, so this stands as a fill-in.

Gattaca.

David’s two bits:

I saw ten films across three days and four nights.

The Virginia theatre did special justice to Gattaca. Writer-director Andrew Niccol used the anamorphic format imaginatively, a bit in the chilly manner of THX-1138, and the framings appeared to full effect on the 56-by-23-foot screen. This time I noticed how much the credit sequence, with only the G-A-T-C letters appearing first, owes to Godard. Like Alphaville, Gattaca uses not artificial sets but actual buildings to evoke the near future.

I thought that Moolade held up well on my second viewing, and the post-film discussion with the main performer Fatoumata Coulibaly (right) and Professor Samba Gadjigo was informative. The film’s call for an end to female genital mutilation is typical of Osmane Sembene’s use of controversial material; Professor Gadjigo recalled that Sembene calls his cinema a “night school” for Africa. Ms. Coulibaly said that in production “Papa Sembene” wouldn’t make eye contact with her, but before filming a painful sex scene he told her that she was “doing the scene for future generations.”

I thought that Moolade held up well on my second viewing, and the post-film discussion with the main performer Fatoumata Coulibaly (right) and Professor Samba Gadjigo was informative. The film’s call for an end to female genital mutilation is typical of Osmane Sembene’s use of controversial material; Professor Gadjigo recalled that Sembene calls his cinema a “night school” for Africa. Ms. Coulibaly said that in production “Papa Sembene” wouldn’t make eye contact with her, but before filming a painful sex scene he told her that she was “doing the scene for future generations.”

Sadie Thompson was still fine, I thought, with Walsh’s skill in cutting and staging exemplifying what Hollywood could do so easily in 1928. Swanson of course is tremendous in the role, using her whole body to tell the story of a woman who’s not as hard-edged as she makes out. The score by Joseph Turrin, conducted by Steve Larsen, was discreet and compelling.

La Dolce Vita seemed to me not to wear so well. I hadn’t seen it in at least twenty years, and its pacing and dramatic point-making appearing at once heavy and unfocused. Still, the film has that patented Fellini verve, and its daring fresco-like structure makes it a remarkable experiment in panoramic storytelling. It’s historically an enormously important film, and Jackie Reich illuminated it in our onstage discussion afterward. She has just published a book on Mastroianni’s career, Beyond the Latin Lover.

Of the items that were new to me:

The Weather Man took me by surprise, not only for its glum tone and antiheroic protagonist but also for its refusal of a tidy happy ending. Of Steve Conrad’s screenplay, Gil Bellows remarked that “one of the things that he can do is make you cringe for a character.” To his credit, Gore Verbinski, of Pirates of the Caribbean fame, found this uneasy domestic drama/ comedy a congenial project.

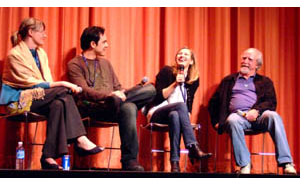

Come Early Morning by Joey Lauren Adams was a clear-eyed character study of an intelligent, flawed woman. Lacking villains and almost lacking heroes, it captures the rhythms of life in a small Arkansas town. Our protagonist, quietly efficient in her job, is caught in family and romance problems as she moves from man to man in a beery stupor. It was tactfully directed by Adams and graced by the underappreciated Ashley Judd. The Weather Man concludes with our hero facing us in close-up, but Come Early Morning ends with the protagonist turned away; in each case, the image feels right. On the left, Lisa Rosman, Eric Byler (Charlotte Sometimes), Joey Lauren Adams, and Scott Wilson (who plays the protagonist’s father).

Come Early Morning by Joey Lauren Adams was a clear-eyed character study of an intelligent, flawed woman. Lacking villains and almost lacking heroes, it captures the rhythms of life in a small Arkansas town. Our protagonist, quietly efficient in her job, is caught in family and romance problems as she moves from man to man in a beery stupor. It was tactfully directed by Adams and graced by the underappreciated Ashley Judd. The Weather Man concludes with our hero facing us in close-up, but Come Early Morning ends with the protagonist turned away; in each case, the image feels right. On the left, Lisa Rosman, Eric Byler (Charlotte Sometimes), Joey Lauren Adams, and Scott Wilson (who plays the protagonist’s father).

I must be the last person in North America to see Holes. Its tight plot, clever humor, and easygoing handling of racial matters endeared it to me. As in old Disney fare, familiar actors (Jon Voigt, Sigourney Weaver, Robin Wright Penn, Tim Blake Nelson) are willing to ham it up for the kids, with enjoyable results. And I was startled by the intricate flashback structure on offer; are kids now being trained to follow movies like 21 Grams? Given the interracial love story at the movie’s center, I had a new angle on what Walden Media might be contributing to modern Hollywood, something valuable that escapes cliches about “family-friendly” and “faith-based” entertainment.

Man of Flowers was a crowd-pleaser. I admired Paul Cox’s visuals, though the grainy print probably didn’t do justice to the range of dark tones in the original. An exercise in portraying a wealthy man’s obsessions and their sources in childhood, it moved toward Buñuel’s Archibaldo del Cruz, but it wasn’t prepared to be as lurid or delirious. A bit too dry and tasteful, perhaps. Still, I admire patient, unshowy long takes, and Man of Flowers is full of them. The photo above shows Paul reading a heartfelt tribute to Roger.

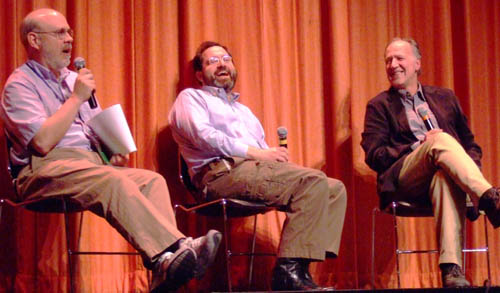

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer was much liked by the audience, and the presence of Alan Rickman made it all the more pungent. I wanted to like it more than I did. Despite my admiration for Tom Tykwer’s other films, particularly Winter Sleepers, The Princess and the Warrior, and Heaven, this one struck me as an overproduced Euro effort at a Big Movie. I thought it overdid the camera tricks (slow-mo, ramping) and the insistence on stuffing every shot with details (e.g., fish, cobwebbed glassware, glistening golden liquids). Above, you see the great actor with Festival Director Nate Kohn and entertainment analyst David Poland.

The simple and modest Stroszek was, for me, better at evoking smells—for instance, the stale smoke of the Himmel bar that our hero frequents. The print was faded and weatherbeaten, but the mysterious simplicity of this modern classic came through. The Wisconsin scenes, shot in Plainfield thirty years ago, wouldn’t need much changing today. As usual, I enjoyed the porous, unpredictable plot and Herzog’s willingness to dwell on unfathomable moments like a premature baby with powerful fingers (sleeping, he looks like a wrinkled alien) and the warped imagery of people passing a prison, seen through a hanging water bottle. The dancing chicken became one of the top screen icons of the 1970s.

Now for some quotes I like.

*Gattaca producer Michael Shamberg: “In the pilot scenes of Top Gun, Tom Cruise doesn’t wear his oxygen mask.” Ebertfest blogger Lisa Rosman: “It’s Scientology.”

*“None of the people I write about have friends.” Steven Conrad, screenwriter.

*“The US and Europe are my market. Africa is my public.” Osmane Sembene, quoted by Samba Gadjigo.

*Werner Herzog gave Roger Ebert an early alert about the importance of Anna Nicole Smith in American culture: “The poet must not avert his eyes.”

*“When I pray, I pray to Jesus.” Joey Lauren Adams.

*“Ambiguity in everyday life isn’t exactly celebrated in most movies. . . . It’s great when a big movie celebrates unnameable things.” Alan Rickman on Perfume.

*“Alan, be more subtle—do more.” Ang Lee to Alan Rickman, directing Sense and Sensibility.

*Why did Michael Wiese move to Penzance? “I was in a Witness Protec—oops.”

*“I’ve learned more about directing by working with bad directors than with good ones. And I’ve worked with a lot of bad directors.” Joey Lauren Adams.

*“Sometimes I think I’d like to join another species. . . . They seem to live a more sensible life.” Paul Cox.

*“Our technological civilization is not sustainable on this planet. Nature is going to regulate us very quickly. . . .We’ll be the next ones [to go extinct]. But that’s okay. Let’s enjoy movies and friendship and beer.” Werner Herzog.

*“I saw perhaps three or four films last year. I love cinema, but I’m not a cinephile.” Werner Herzog.

And some portraits of Ebertfest regulars:

First: Michael Wiese, filmmaker (Hardware Wars, The Sacred Sites of the Dalai Lamas) and publisher of outstanding books on the art and craft of film. Next, actor Scott Wilson (In Cold Blood, Junebug, The Host, and many more). Finally, Jim Emerson, who runs Roger’s website and writes fine film criticism at Scanners.

Each year, several guests receive an Ebert Thumb. This year, Kristin was one of the lucky ones.

Finally, here I am with Michael Barker, co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, and Werner Herzog. All I said was that I was from Wisconsin….

I plan to blog again soon about Roger and his contributions to filmmaking and film culture. For now, let me just echo Kristin’s opening point that his passion for film is exceeded only by his enjoyment of other people. This weekend’s gathering of top-rank filmmakers, young and old, and the enthusiastic audiences showed that he is probably the most deeply loved film critic whom we have ever had.

Trims and outtakes

Some jottings from DB:

Continuity Boy meets Badgers

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim studies the ways we scan shots and shift our attention across cuts. His talk was illustrated with film sequences showing little yellow dots swarming around the frame; these indicate the points in the image where his subjects’ glances landed. Tim shows pretty conclusively that there’s a consensus about where viewers look during a shot (faces, movement, the center of the frame) and that classical continuity cuts can push our attention to and fro with remarkable facility. One of the most surprising findings was that viewers are often starting to shift their attention to a new frame area just before the cut comes. Why? Tim has some intriguing suggestions.

Tim also showed some remarkable effects of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” the fast-cut close-ups that characterize so much current cinema. Because these passages leave no time for visual exploration, viewers seem to revert to a cursory test for the shot’s basic point, usually at the center of the frame. Tim’s examples from Requiem for a Dream were fascinating, showing how real viewers are playing catchup in very fast-cut sequences.

This is rich and promising research, showing once more that Leonardo da Vinci, Eisenstein, and a few others were right to think that many creative choices in the arts can be studied with the tools of science. It also shows that filmmakers, like other artists, are seat-of-the-pants psychologists, achieving complex effects through decisions that “feel right” and that they have no need to explain theoretically. That’s our job.

For Tim’s narrative of his visit, and a lot more about his research program, go here. For something not quite completely different, about eye-tracking, print ads, and crotches, go here.

Six more from RKO

The enterprising folks at Turner Classic Movies have discovered six RKO films that have been missing for many years. It’s a harvest of 1930s titles, promising some intriguing situations (e. g., Ginger Rogers as a telemarketer) and carrying the names of directors like William Wellman, John Cromwell, and Garson Kanin.

A Man to Remember (1938; at the top of this page), Kanin’s first film, is the only one of the batch I’ve seen so far. One of the New York Times‘ ten best films of 1938, it went virtually unseen until a print surfaced at the Netherlands Filmmuseum in 2000. A Man to Remember is a portrait of a small-town doctor who tends to the poor and lets others, chiefly a cadre of corrupt businessmen, take credit for his good works.

It could all be mawkish, but Edward Ellis plays the doctor as a testy guy who levels with his patients and wins the town’s respect through quiet cussedness. The performance echoes Ellis’ crabby but likable inventor in The Thin Man (1934). Dalton Trumbo’s script has an intriguing flashback structure, less bold than in The Power and the Glory (1933) but still ambitious for a B project.

The six RKO discoveries are screening on April 4th as an ensemble, then they’re scattered through the rest of the month. All should be worth checking out. Once more TCM proves itself the film-lover’s channel of first choice.

Bambi or kitty?

Two recent books support the claim that New Hollywood, or New New Hollywood, is at bottom in debt to old Hollywood. (The full case is presented in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood.)

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

Mamet adds a fair amount on editing, supplementing the remarks in his Pudovkin-flavored On Directing Film. For instance: “At the end of the take, in a close-up or one-shot, have the speaker look left, right, up, and down. Why? Because you might just find you can get out of the scene if you can have the speaker throw the focus. To what? To an actor or insert to be shot later, or to be found in (stolen from) another scene. It’s free. Shoot it, ’cause you just might need it.”

Mamet bemoans the script reader, whose motto must be Conform or Die. By contrast, Blake Snyder makes conformity seem fun and–well, if not easy, at least attainable. His Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need (Michael Wiese Productions) bulges with formulas, recipes, and gimmicks.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Speaking of screenplays….

J. J. Murphy is an old friend (we went to grad school with him in 1971) and colleague (he teaches in our department). Renowned as an experimental filmmaker, he has turned his attention to American indie cinema. His new book Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work offers an in-depth analysis of several recent films. J. J. shows how they obey mainstream conventions of construction while still innovating in other ways. I especially like his discussions of Hartley’s Trust, Korine’s Gummo, and Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. I think it’s a book that everyone interested in current American cinema would find stimulating.

You can find out more about it, and read an excerpt, here. Congratulations, J. J.!