Archive for the 'Internet life' Category

OBSERVATIONS goes all FILMSTRUCK

DB here:

In light of the cataclysm that struck on election day, to return to talking of films can seem frivolous. We’ve delayed posting this blog because we, like millions of other people, are seized with a dread as to what may come for our friends, our neighbors, our country and the world.

At least for the moment, though, we can’t stop living other aspects of our lives. Judging by the attention our entries continue to get in these days, we think that we should keep trying to provide ideas and information about film. Art is important too.

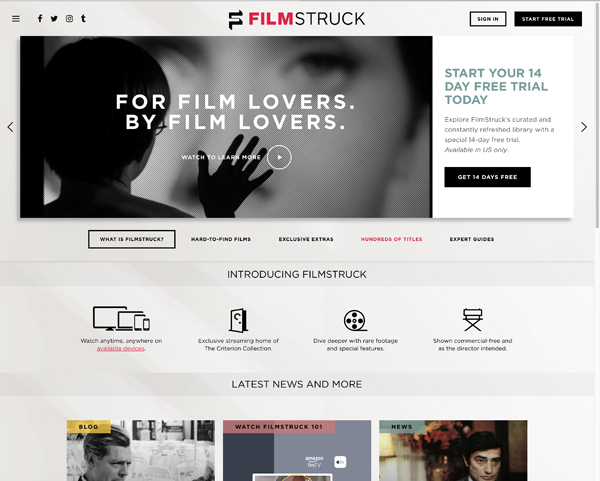

Thunderstruck by FilmStruck

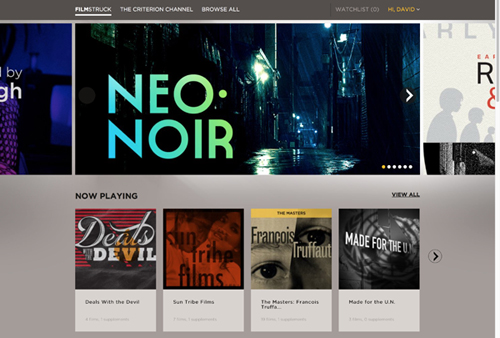

You probably know that Turner Classic Movies has partnered with the Criterion Collection to create a streaming service called FilmStruck. There’s a comprehensive overview of the service on Variety, and Peter Becker has an invigorating introduction on the Criterion site.

The library includes many hundreds of films, mostly foreign imports and independent features and shorts. Many of the titles come from US non-studio distributors, but a vast number are from the Criterion library. Many will be titles not available on DVD.

It’s an all-you-can eat subscription service. For $6.99 per month you can get a basic membership in FilmStruck, and that will provide hundreds of titles, including many Criterion ones. For an extra $4, you can add on the Criterion Channel, with a huge additional selection (about 500 titles at any moment). There’s an annual rate covering both for $99. You can sign up for a 14-day free trial here.

Both wings of Filmstruck include the sort of bonus materials found on DVDs: background information, archival footage, talking heads, and video essays. The Criterion titles include voice-over commentary you can play while watching. I’m especially excited by the prospect of having the filmmakers’ commentaries from out-of-print laserdisc editions (e.g., Boogie Nights). And the FilmStruck site is already hosting, for free, a rich array of blog entries by experts (Pablo Kjolseth, Kimberly Lindbergs et al.) offering perspectives on the library titles.

The films can stand singly, but they’re also gathered into groups by theme, director, nation, or whatever.

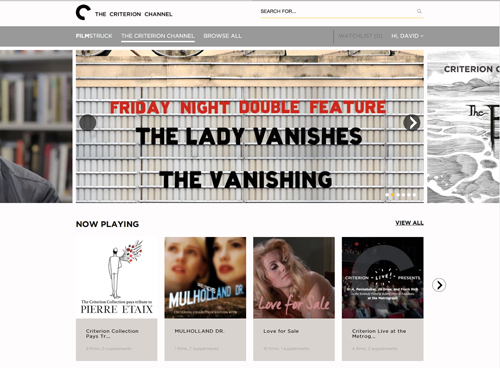

The Criterion Collection is richly curated too, with new groupings and titles highlighted every day. There are even Friday night double features, and new releases constantly refreshing the pool. And there are special events, like an evening at Manhattan’s wonderful Metrograph theatre.

This double feature is introduced by Michael Sragow on the regular Criterion website, so the synergy is tight.

In addition, there are new introductions and appreciative discussions of films. For example, our friend Sean Axmaker has some coming up. And there are continuing series with film-struck partisans.

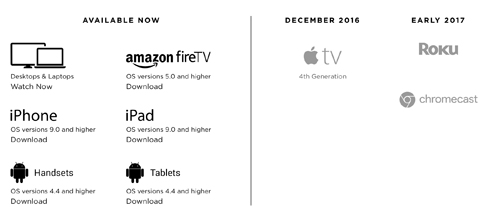

At present, FilmStruck can be streamed on any computer or laptop, Amazon Fire, recent generations of iPad, and other devices. But not on your iPhone, pleeze. Roku and Chromecast access are coming early next year.

In short, this is a treasure house for fans of classic foreign and American films. Some older Hollywood studio films are available (e.g., Brute Force from Criterion), but I bet more of the TCM library studio will migrate to the service. I’m itching for those beautiful Warner Archive items.

FilmStruck and us (and you, we hope)

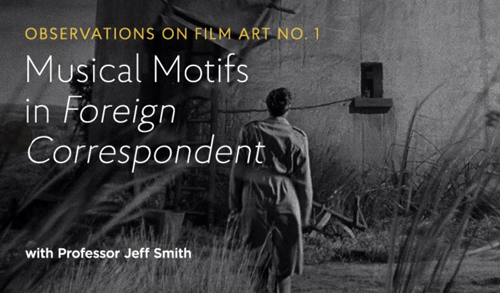

We are honored and happy to be involved with FilmStruck. Under the blog rubric, “Observations on Film Art,” Kristin and I and Jeff Smith, our collaborator on Film Art have launched a series for the Criterion Channel. We offer short appreciations of particular films and filmmakers.

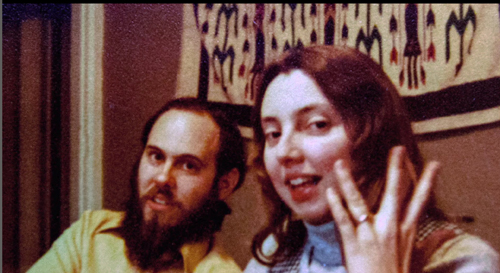

There’s a video introduction to the three of us…

… including some potentially embarrassing vintage images.

Here’s our first entry, featuring Jeff Smith.

Coming up are Kristin on Kiarostami, and me on L’Avventura and Sanshiro Sugata. We hope to post about one per month.

Our discussions are analytical, focusing on particular techniques of style and narrative. They don’t contain crucial spoilers, so most can be watched before the film as well as after.

Of course we’re tremendously excited to get our ideas out there in a new platform. We conceive the series as like our blog—applying our research into film form, style, and history to films in a user-friendly way. We hope that we’ll find an audience among cinephiles as well as among more casual viewers who simply want to get more out of the films they see.

As the installments go online, we hope to post blog entries that flesh them out. Jeff will soon be posting an entry that supplements his Foreign Correspondent analysis.

My email address is still visible on every page of this site, so if you have responses to the FilmStruck versions of “Observations on Film Art,” we’d welcome hearing them. We look forward to working with our colleagues at Criterion—Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Tara Young, Penelope Bartlett, and all their associates. This ought to be plenty fun.

Thanks to Mary Huelsbeck and Amy Sloper of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research for letting us prowl the premises for our introductory video.

At Stream on Demand, Sean Axmaker reviews the FilmStruck project.

P.S. 15 November: Peter Becker talks with Scott Macaulay of Filmmaker about the ambitions of the Criterion Channel, with many details about films and filmmakers to be showcased.

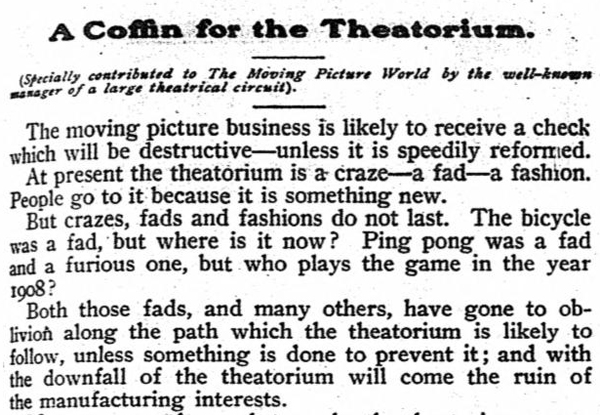

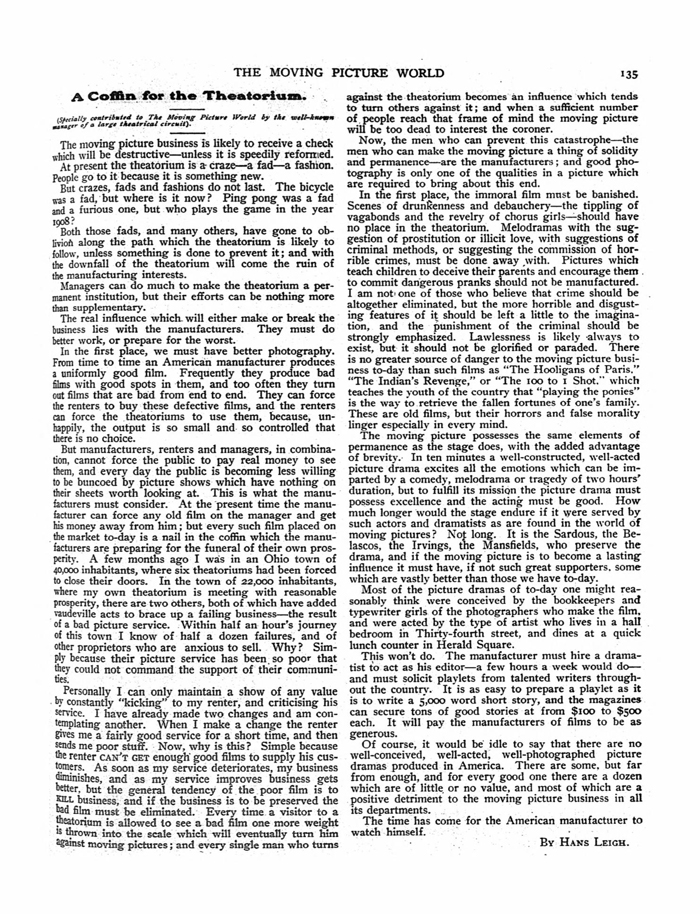

The end of Theatoriums, too

Moving Picture World (February 1908), 135.

DB here:

Vis-à-vis the last post, all of three hours ago, Alert Reader and arthouse impresario Martin McCaffery sends the above.

Actually, it’s much in the spirit of current jeremiads: Movies and their theatoriums better shape up, or they’ll be finished–like bicycles and Ping-Pong.

History is so cool. Full text here and below. There’s also a 1908 rebuttal, in the spirit of movies-are-doing-just-fine-thanks, here. Both courtesy the prodigious Lantern.

Good, old-fashioned love (i.e., close analysis) of film

Kristin here:

On April 10, I received a message from Tracy Cox-Stanton, the editor of a new online journal, The Cine-Files. This journal is run out of the Cinema Studies department of the Savannah College of Art and Design. The message was an invitation to contribute to the fourth issue of the journal, of which, I must admit, I had been unaware until that time.

The invitation included two options. One was: “Offer a brief (1000-2000 word) reading of a film “moment” that considers how some particular detail of a film’s mise-en-scène (a prop, an actor’s gesture, an aspect of costume, a camera movement, etc.) illuminates the film as a whole, helping us understand the relationship between a film’s details and the overall “work” of cinema. We encourage the use of film stills.”

Having lived for decades in an academic publishing world which tended to discourage the use of film stills, I found this a cordial invitation indeed. Still, my initial thought was, if I had an idea for a study of a film “moment,” I should put it on our blog. We bloggers tend to become selfish about ideas for compact, easy-to-write analyses.

The other option, however, seemed more feasible: to respond to three questions as an online interview. It seemed a simple way of encouraging a promising new journal, and I accepted.

The Cine-Files is an appealing project. In place of the recent focus on cinephilia , which has often encouraged self-absorbed pieces in which film-lovers ponder the nature of their own love of film, “Cine-Files” implies good, hard study, with research resulting in files full of data that can result in informative, meaningful history and analysis.

It reminds me of The Velvet Light Trap in its heyday, though its format is quite different. In 1973, when David and I first arrived at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, graduate students in the young cinema-studies program and coordinators of film societies (showing 16mm prints by the dozen each night) published this extraordinary magazine. It was a combination of auteur worship, studies of studios, and genre analysis. The Velvet Light Trap was a film journal in an era when such things were rare and graduate students could be tastemakers.

The Cine-Files is similarly focused on films in their historical context. It is semi-annual and alternates open-topic and themed issues. Its first themed issue was on the French New Wave. Remarkably for a new journal, it attracted comments from experts such as Dudley Andrew, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Richard Neupert. The newest issue, to which I contributed, is on Mise-en-scène. The topic for interviews, however, was a bit broader: “close readings.” The new issue, #4, has recently been posted, and my interview is here. There is also a call for papers for the fifth issue, an open-topic one, here.

Tracy has kindly agreed to our re-posting my responses to the three questions about close readings here. We have slightly modified the original post to suit this venue. We thank Tracy for a set of questions that provoked what we hope are interesting responses.

What is at stake in close reading?

To begin with, I don’t use the phrase “close reading.” I prefer “close analysis.” The notion of close reading is presumably a holdover from the 1970s and 1980s, when semiotics was a popular approach in film studies. Cinematic technique was thought to be closely comparable to a language, with coded units and grammar. Although there are some comparisons to be made between the techniques of cinema and a language, I don’t think the similarities can be taken very far.

“Reading” to me implies that interpretation is one’s main goal in looking closely at a film. I usually use interpretation as part of analysis, but it is seldom my main goal. Analysis, loosely speaking, to me means noting patterns in the relationship of the individual devices in a film (devices being techniques of style and form) to each other and figuring out why those patterns are there. What purposes do they serve?

What is at stake in close analysis depends on what sort of analysis one is doing. I’m assuming here that the subject is scholarly or semi-scholarly analysis intended for publication. My own purposes for analysis fall into at least these categories:

1. The simplest reason to analyze a film would be to find out more about it because it’s appealing or intriguing.

I’ve written essays on Jacques Tati’s Les Vacances de M. Hulot and Play Time, in both cases because I admired them and wanted to be able to understand and appreciate them better. I go on the simple assumption that we can only be entertained and moved by films to the degree that we notice things in them. Complex films can’t be thoroughly comprehended on a single viewing or even several viewings. Sometimes you may need to watch them more closely, not in a screening but on a machine, like a flatbed editor or a DVD player, that lets you pause and slow down the image.

2. One might analyze a film in order to answer a question, often to do with the nature of cinema in general.

My essay on “Duplicitous Narration and Stage Fright,” as the title suggests, arose more from my interest in a particular, unusual device, the “lying flashback,” than from a particular admiration for the film.

3. You might want to make a case that a film is significant and suggest why others should pay attention to it.

One example would be the rediscovery over the past few years of Alberto Capellani’s French and Hollywood silent films. On this blog site, I posted two entries, “Capellani ritrovato” and “Capellani trionfante,” analyzing some scenes to support the claim that Capellani was one of the most important stylists and innovators of the era from 1905 to 1914.

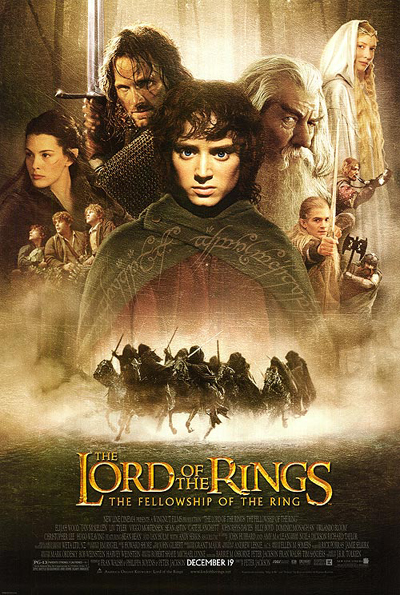

A very different case came with The Lord of the Rings trilogy by Peter Jackson. I had written a book, The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007), primarily on the marketing and merchandising surrounding the film and on its many influences. I would not claim Jackson’s film to be a masterpiece, but there was such a great backlash against it, mostly by literary scholars of Tolkien, that I thought it might be worth counterbalancing their opinions. I wanted to make a modest defense of the film as containing some excellent passages and effective decisions concerning the adaptation process. So I wrote two essays based on that argument. (See the codicil to this entry for references.)

4. Close analysis can be vital for writing about film history.

For example, David and I have studied films closely to determine the stylistic and narrative norms of specific times and places. We’re also interested in finding films that were innovative in relation to those norms. Rather than examining a single film closely, such an approach involves analyzing many films to find commonalities and divergences. For example, David has studied the norms and innovations of modern Hong Kong cinema (Planet Hong Kong, Harvard University Press, 2000; second edition available online at Observations on Film Art).

Another such project was my Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique (Harvard University Press, 1999). There had been many claims in academic and journalistic writings that the norms of Hollywood storytelling had declined after the end of the studio era and that we were now in a post-classical era. Such claims didn’t tally with what I was seeing in the best Hollywood films, the ones held up as models within the industry. I did case studies of ten such films, dating from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, going through each scene by scene. I showed how classical techniques like protagonists’ goals, dangling causes, dialogue hooks, redundant motivation, and other traditional norms were still pervasive in modern Hollywood. I chose the ten films because I liked them, but others would have made my point equally well.

Please tell us about something that couldn’t be understood without a frame-by-frame attention to detail.

I don’t think most close analysis goes to the minute detail of examining a film frame by frame. Sometimes it’s necessary, especially with French and Soviet films of the 1920s or with some experimental work. There can be lots of ways of looking closely at the parts of a film and relating them to other parts.

Take a simple example, in my essay on Late Spring, I reproduced eleven shots across the length of the film that include a sewing machine off to one side of the frame–or, in one case, the space where the machine had been. No two of these shots are the same, though they often are only small variations on each other, with the machine closer or further from the camera, sometimes on the left, sometimes the right, and so on. I even missed a couple, the second and third shots immediately below, so there are actually thirteen variants. (DVDs do have their advantages. It’s not so easy going back and forth across a film looking for such repetitions in a 35mm print.)

The series culminates late in the film, after the daughter has married and left her widowed father living alone. We see a similar framing along a corridor, and the space formerly occupied by the sewing machine is empty. (See below.)

The daughter doesn’t use this sewing machine in the course of the action, and no one mentions it. Many viewers probably vaguely notice that there is a sewing machine in the house. A few may notice its eventual absence late in the film. But even someone who watches the film over and over and at some point notices that there is a meaningful pattern of the sewing-machine shots would not be able to describe it. I suspected that the sewing-machine shots were small variations on each other, but were there some repetitions? How many were there? I was only able to get a good understanding of how the motif worked by photographing all the shots (or so I thought at the time) and comparing them side by side—and having the luxury to reproduce all eleven frame enlargements in my book.

What point is there in analyzing such a motif in detail? If we admire Claude Monet for taking infinite trouble to capture tiny changes of light on haystacks or lily-ponds, why not devote the same respect to one of the cinema’s greatest directors? To go back to my point at the beginning, we can only appreciate a film to the extent that we notice things about it. I take it that the critic’s job is to notice such things and point them out for the enrichment of others who don’t have the time or inclination to do close analysis.

How do digital technologies allow us to engage in “direct” criticism that bypasses traditional written criticism?

One obvious answer is that digital technologies allow anything that could be published in printed form to be offered online. Whether written for consumption via the internet or already published and then scanned to be posted, online criticism offers some obvious advantages. There is no lag in publication time and no need to hunt for a press. Of course there are disadvantages too: no real guarantee of long-term survival, often no academic reward for publishing through a non-refereed process. David and I have posted many entries involving close analysis on this blog. (I discuss the history and approach of Observations on Film Art in an essay for the first issue of the online journal, Frames Cinema Journal: “Not in Print: Two Film Scholars on the Internet.”)

Perhaps more interesting is the question of what critical tools digital technologies offer for analysis itself. In past decades, David and I had to rig up elaborate camera-and-bellows systems to photograph frames from prints of films—as well as to travel far and depend on the hospitality of archivists to gain access to those prints. Nowadays DVDs and Blu-rays bring hitherto rare films to the critic, and readily available players and apps allow for easy capture of frames for illustration purposes. If the essay or book based on close analysis using such tools is to go online, it also becomes practical to reproduce a great many more frames as illustrations than would be possible in a print publication. David’s e-book edition of Planet Hong Kong permitted him to publish most of the illustrations in color, an option that would have been prohibitive in a university press volume.

The possibility of using short clips as illustrations in an article or book is very promising, especially once electronic textbooks get past the trial stages. I made a modest contribution to the use of clips as examples for introductory students with “Elliptical Editing in Vagabond”; this was done with the cooperation of the Criterion Collection and posted by them on YouTube in 2012. Other extracts appear as proprietary supplements for Film Art: An Introduction. Since then, David has offered three online lectures analyzing editing, the history of film style, and the aesthetics of CinemaScope; see our Videos listing on the left.

Video essays analyzing films are still a new format but show great potential. Their usefulness will depend on how the issue of copyright plays out. At this point, I’m hopeful that showing clips as part of an analytical study will become established as fair use, as clearly it should be. Being able to use moving images complete with sound as well as still frames from films will be an extraordinarily useful tool.

I hope that critics using digital tools will take the trouble to create analyses as complex as one can achieve through description in printed prose. This would mean editing together stills and short segments from across a film, recording voiceover comments, adding graphics where useful, and so on. Close analysis of this type will always be a labor-intensive process.

The analyses mentioned in this article have been published in collections. “Boredom on the Beach: Triviality and Humor in Les vacances de M. Hulot,” “Duplicitous Narration and Stage Fright,” “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception,” and “Late Spring and Ozu’s Unreasonable Style” appear in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988). “Stepping out of Blockbuster Mode: The Lighting of the Beacons in The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003),” was published in Tom Brown and James Walters, eds., Film Moments (British Film Institute, 2010), and “Gollum Talks to Himself: Problems and Solutions in Peter Jackson’s Film Adaptation of The Lord of the Rings” appeared in Janice M. Bogstad and Philip E. Kaveny, eds. Picturing Tolkien: Essays on Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings Film Trilogy (McFarland, 2011).

Late Spring (1949).

Jack and the Bean-counters

Kristin here:

I don’t know about you, but back on January 16 about the last thing on my mind was the release, still six weeks away, of Jack the Giant Slayer. It wasn’t a film I was planning to see. Not many people were, as it predictably turned out. I was more concerned with a recent release, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, and whether the decision to turn a two-part film into a trilogy had adversely affected the narrative. I posted my some-good-news-some-bad-news entry that day.

Not as giant as they might think

It turned out on that same day there were some fans of fantasy films and/or Bryan Singer, the director of Jack, who were exercised about the recently released poster for the film (reproduced above). I discovered this from a Hollywood Reporter story published in the wake of Jack’s disappointing opening weekend, when it grossed $27.2 million domestically. The story led off with an anecdote about the poster kerfuffle:

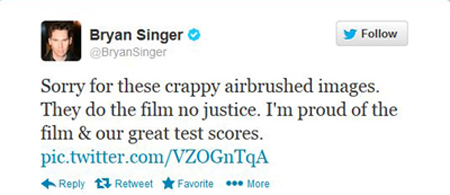

When Bryan Singer sat down at his computer in mid-January and read Internet comments criticizing a new Warner Bros. poster for his big-budget epic Jack the Giant Slayer, he fumed. He didn’t care for the cartoonish image of the film’s stars brandishing swords and standing around a swirling beanstalk. So Singer complained on Twitter. “Sorry for these crappy airbrushed images,” he wrote Jan. 16, irking Warners’ powerful marketing head Sue Kroll. “They do the film no justice. I’m proud of the film & our great test scores.” An insider confesses, “Bryan felt like he had to apologize to his fans.”

This gesture annoyed studio executives, who demanded that Singer take it down. He hasn’t. The apology won him some points with the fans, as some sample tweets in response show:

Do any current Warner Bros. executives know who Saul Bass was? More to the point, do the studios have any idea how much fan devotion is gained by directors like Singer, Peter Jackson, and Guillermo del Toro, who try to communicate directly with the fans as often as they are allowed to, and even sometimes when they aren’t? If the studios did have any idea, they would encourage directors to hold question-and-answer sessions on fan sites and communicate via social media far much more than they do now. I suspect studios give up tens of millions of dollars in free publicity by treating fans as potential spies, spoiler-mongers, and authors of vicious reviews based on trailers.

Ring? What Ring?

This disappointment with Jack’s poster reminded me of an incident that happened late in the filming of The Lord of the Rings. I describe it in The Frodo Franchise:

On 16 Dcember 2000, New Line’s president of domestic theatrical marketing, Joe Nimziki, met with the director concerning the Rings publicity campaign. One of his purposes in visiting Wellington was to meet the cast, who would be involved in the upcoming press junkets, parties, and premieres. The occasion soured when the filmmakers and actors saw the proposed poster design. Based on its audience research, New Line had concluded that Rings would appeal primarily to teenage boys, and the design was busy and garish. The actors backed Jackson up, threatening not to participate in the marketing campaign if it proceeded along those lines. Jackson had a mock-up poster made, featuring muted tones and a simply design centered on an image of the One Ring. The design was not used, but it gave New Line a sense of what the filmmakers considered appropriate. (p. 81)

When I made my first research trip to Wellington in 2003, I had no idea that this incident had occurred. Someone high in the production mentioned it to me out of the blue during an interview, which led me to think that this person considered it important and wanted me to mention it. After nearly three years, it obviously had remained a sore point. (I did describe the incident, but in general I portrayed the few mistakes I mentioned in my book as part of a learning curve that the studio benefited from.) Unfortunately I have never seen the offending poster design. I have seen one of what were apparently two mock-up copies of Jackson’s version made, on the basis of which I wrote the brief description above. The design was too muted in color and minimalist in layout to be useable, but it evidently served its purpose.

Obviously there’s a big difference between the handling of these two offending poster designs. New Line, which produced The Lord of the Rings, took the trouble to show the cast and crew the planned poster and acceded to their wishes about replacing it. As a result, the cast participated in the many press junkets and other publicity events. I’m not sure which poster design for The Fellowship of the Ring convinced the cast, but the one at the bottom of this entry was the main one used. Definitely better than the one for Jack at the top.

Warner Bros. presumably did not bother to show Singer the poster, or test it on fans, or do anything to make sure that it would boost rather than dampen potential moviegoers’ enthusiasm. It is as conventional a poster as one could imagine for such an expensive film.

The irony in all this is that New Line also produced Jack the Giant Slayer. Due to various post-Lord of the Rings failures, primarily The Golden Compass, New Line is now a production unit within Warner Bros. It doesn’t handle its own distribution or marketing, having been downsized by about 80 percent. Warners takes care of everything except the production itself.

Doesn’t amount to a hill of beans

Jack’s opening weekend’s gross was followed by a nearly 64 percent drop during its second weekend. It just went into second run last week, so its theatrical life is rapidly tapering off. In the same Hollywood Reporter story that alerted us to the poster tweets, author Pamela McClintock called Jack “the latest in a string of dismal 2013 domestic releases.” She added,

Revenue and attendance are both down a steep 15 percent from the same period in 2012, wiping away gains made last year. Jack may have cost far more than any of the other misses, but in assessing the carnage, there’s a collective sense that Hollywood is misjudging the moviegoing audience and piling too many of the same types of movies on top of one another.

I think that collective sense is shared by almost every ordinary viewer. Jack the Giant Slayer. Really? For that matter, Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters? Upon merely hearing these titles, I didn’t expect them to be hits. In the wake of The Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter series, Hollywood has been pushing fantasy harder and harder, but there is a limit. I think that has been reached with the mini-trend toward adapting fairy tales with adults in the lead child roles. Making Jack a “giant slayer” (grammar-police note: this should be “giant-slayer”) doesn’t hide the fact that this is really “Jack and the Beanstalk” re-titled by committee.

Recently Variety reported that the success of Alice in Wonderland early in the year (it was released in March, 2010) has led studios to release films of the summer-tentpole type well before the traditional Memorial Day weekend opening of the summer season: “Warner Bros. started this year’s March madness with the pricey Jack the Giant Slayer, which never sprouted.” Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful opened one week later.

Now there’s a film I wanted to see, and many others did, too. It’s currently still in first run and pushing toward the $500 million mark worldwide. With a reported $215 million budget plus publicity costs, that’s not a big hit (it’ll probably become profitable in Blu-ray, streaming, etc.), but it’s doing a lot better than Jack. Jack’s budget is reported at slightly under $200 million, with marketing costs of over $100 million. As of now it has grossed a little under $200 million worldwide. A week after Oz, The Croods appeared, aimed to some extent at the same audience as the two films that preceded it. In short, Hollywood is not only making a lot of children’s fantasies, adapted to a broader audiences including adults, but it is releasing them opposite each other.

Fans? what fans?

This is not to say that all such films fail. I found Oz a clever film, better than most critics have given it credit for. It presents an imaginative riff on the 1939 The Wizard of Oz as if it had been made using classical storytelling techniques but with digital technology.

But back to that claim that “Hollywood is misjudging the moviegoing audience.” It’s hard to imagine a group of executives sitting around a big table and seriously thinking that an expensive digital extravaganza based on “Jack and the Beanstalk” would bring people flocking to theaters, yet they did. Why? Possibly because they are out of touch with the fandoms they depend on.

Back when I was researching the Lord of the Rings online fandom and its relationship to New Line’s publicity department, it seemed that Hollywood was beginning to understand fans. It was a hard learning process, but New Line’s executives reluctantly gave some big websites occasional access to sets and once in a while sent them news exclusives. Such openness, grudging though it was, generated free publicity and goodwill. The studio also allowed Peter Jackson to interact with fans, though in strictly controlled circumstances.

Warner Bros. is a different animal altogether, and it has squandered much of what goodwill New Line gained in those days. The Jack the Giant Slayer poster controversy provides perhaps one clue as to how indifferent studios now are to their public and how much their insularity can damage their bottom lines.

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, made by New Line under the tight control of Warner Bros., has of course done very well financially. It grossed over a billion dollars worldwide–though just barely, at $1,017,003,568. If we could adjust worldwide figures for inflation (impossible due to different inflation rates in different countries), each installment of The Lord of the Rings would undoubtedly turn out to have earned more. This despite all the surcharges for the many 3D screenings of The Hobbit.

Why didn’t it do quite as well as the previous entries in the franchise? Perhaps some people who had liked Rings were put off by their perception of The Hobbit as more of a children’s film. Perhaps it was partly the reviews, which were considerably less enthusiastic than for any of the three parts of Rings.

I wonder, though, if Warner Bros.’s lack of interest in the fans might have had something to do with it. Consider what New Line had done for fans in the marketing of Rings as compared to what Warner Bros. has done with The Hobbit. New Line started a pioneering website, managed by Gordon Paddison, that drew millions of fans long before The Fellowship of the Ring appeared. Gordon Paddison, now running his own publicity firm, has created a Hobbit website as well, but it’s primarily a large ad for the Blu-ray and DVD, with none of the free wallpapers and other items that were so popular on the Rings site. Even a live online event from March 24, during which Peter Jackson answered fan questions, was re-posted there without the brief preview footage from The Desolation of Smaug–an unkind cut that annoyed fans greatly. This was especially unfair because to log in to the live event, one needed a code enclosed in the Blu-ray/DVD package, and the Blu-ray release hadn’t occurred in many part of the world by March 24. Not good public relations.

The main online publicity venue for The Hobbit has been Jackson’s own Facebook page, where ten production vlog entries were posted at wide intervals. These later became the main supplements for the theatrical DVD release. Given the breezy, open tone of these vlog entries, it seems possible that they can be credited more to Jackson’s initiative than Warner Bros.’s.

New Line also licensed a company to create a fan club for The Lord of the Rings, complete with an excellent bimonthly magazine. A considerable amount of effort was put into the eighteen issues that appeared, including interviews not only with the filmmakers but with the makers of licensed tie-in products. Fans were encouraged to send in questions for the interviewees, and some of these got included. The names of the charter members of the club were run in a crawl after the credits of the extended-edition versions of the DVDs, a process that, even at a rather fast clip, ran for about twenty minutes. This won huge loyalty from fans, even those who joined later and didn’t get into that crawl-title.

For The Hobbit, there was no fan club and no magazine. I can imagine that the Rings fan club generated a relatively small income for New Line compared to the many other licensed items, but it created much enthusiasm among fans. The film’s official Facebook page is a feeble substitute.

For decades people have been saying that Hollywood executives are out of touch with their audiences, make too many movies, spend too much on their movies–especially in age of special-effects-based blockbusters. It’s an old complaint but one that may be a genuine and growing problem as executives with no personal film production experience control the output of studios owned by huge corporations.

The Hollywood Reporter story that began with the anecdote about Singer’s apologetic tweet ends with some insight:

Privately, studio executives concede that Jack was a feathered fish, neither a straight fanboy tentpole that Singer (X-Men, Superman Returns) is famous for nor a pure family play. “Sometimes you simply have a movie that is rejected,” laments one Warner executive, a common refrain these days in Hollywood. “You can spend as much as you want, market it a zillion different ways, and it still doesn’t work.”

Someone might point out that Jack and Rings are not comparable projects. Rings was adapted from a beloved classic and already had a significant fan base. Jack was not based on a novel and had no such fan base. But I believe that the big studios view fantasy as a genre with a broad, somewhat unified fan base consisting of people who will go to see just about any fantasy film. The failures of not only Jack and Hansel and Gretel but also of others like Mirror, Mirror show that that’s not the case.

The answer is out there

One solution to the studios’ isolation could be to get on the Internet, keep tabs of the huge amount of fan opinion already there and appearing every day, and get a sense of what the real audience wants.

One solution to the studios’ isolation could be to get on the Internet, keep tabs of the huge amount of fan opinion already there and appearing every day, and get a sense of what the real audience wants.

For a start, there is no “fantasy” fandom. There are fandoms around specific stories or series or movies or games. They create websites and Facebook pages and videos. Many fans are quite smart and understand the conventions of the fantasy genre. They know how the industry markets things to them. (Witness all the accusations that fly when a studio repackages a film yet again as a DVD/Blu-ray with only minimal changes in the supplements.) They know exactly what they want marketed to them and what they don’t want. Richard Taylor, the head of Weta Workshop, which designed many of the collectibles as well as the Rings and Hobbit films, is a hero to fans. Affluent Rings fans who get married can commission Daniel Reeves, the calligrapher for the franchise, to design their wedding invitations. Denny’s Hobbit meals, on the other hand, are viewed variously as merely amusing to downright offensive.

There are also rivalries among fandoms. Ask a Ringer and a Harry Potter fan who is the greater wizard, Gandalf or Dumbledore, and watch the feathers fly.

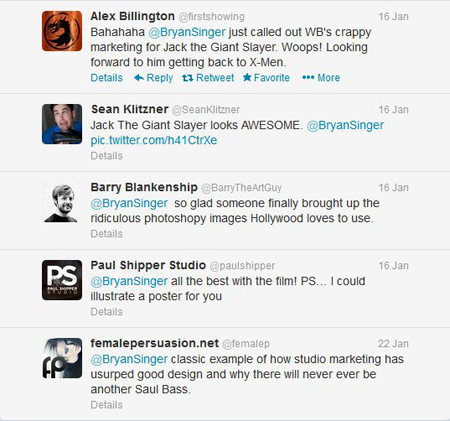

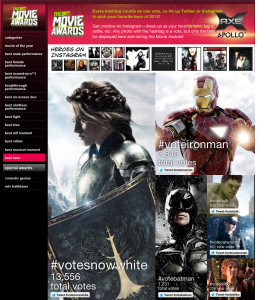

There was a vivid example of this just last month. The MTV Awards nominations for 2012 were posted for fans to vote on. In the Best Hero category there were Snow White (the Snow White and the Huntsman version), Batman, Catwoman, Iron Man, Hulk. and Bilbo Baggins. Shortly into the voting, Snow White was at first place with 13,556, with Bilbo dead last with 226 (left).

Snow White beating Iron Man and Batman? Ringers realized at once that this was not an overwhelming vote for Snow White but for Kristen Stewart, and it was happening because of the Twihards–the devotees of the Twilight series.

Rallying around, Ringers began trying to get people to Vote Bilbo. Fans created memes for tweeting and re-tweeting. TheOneRing.net, the biggest Tolkien website, got involved in helping coordinate individual efforts into a unified campaign to spread the word. Spiegel Ei posted a amusing video on Vimeo, “put a ring on it #VoteBilbo,” in which Bella Swan (Stewart’s character in the series) meets several Rings characters, reads Tolkien’s novel, researches it on the Internet, and abandons her world for Middle-earth. The short film was so clever that MTV’s website even featured a news story , linking to it–a strange case of bias that may have helped sway the voters. (The # symbol in the title comes from the fact that fans could vote only by tweeting for one of the six nominees.)

Even so, during the final exciting week, the MTV vote seesawed back and forth between Snow White and Bilbo, but the Ringers’ campaign won out, with Bilbo attaining a margin of just over 100 thousand:

Measured by the box-office records of all the films, Snow White would seem to be least popular. Yet it wasn’t the ticket-buying audience as a whole voting. It was the hardcore fans–and mostly fans from a different fandom at that.

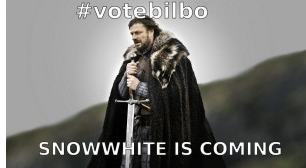

Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway has posted an excellent rundown of the campaign on TheOneRing.net, “When Fandom Comes Together: How #VoteBilbo Rallied the Ringers.” It conveys how a large number of devotees worked very hard for free to create an almost professional-level campaign for a character and film they loved. All this within the space of a few weeks.

I’m not saying that a studio marketer could go onto the Internet and find hard facts on fans’ likes and dislikes. It’s something one gets a feel for by looking at the message boards on TheOneRing.net or checking out The Leaky Cauldron (the biggest Harry Potter fansite) or liking a bunch of directors’ and films’ Facebook pages. By the way, it’s odd that Peter Jackson has a FB page that, with its nearly 800 thousand Likes, has become the main online publicity site for The Hobbit, while Bryan Singer doesn’t even have a FB page. Does that suggest any systematic approach in WB’s publicity campaigns? True, Jack has a FB page, but these days every film does.

What sorts of things can you learn by looking at such sites and pages? It’s interesting, for example, that Cliff’s fandom story includes one of many images that were devised by fans for the twitter campaign for Bilbo, one not from Rings or The Hobbit, but from Game of Thrones (right). Ringers would instinctively know that Lord of the Rings fans would be far more likely to read George R.. R. Martin’s book series or watch the TV adaptation than would Twihards. Not only would they recognize the image shown (the character played by Sean Bean, who was Boromir in The Fellowship of the Ring), but they would know that “Snowwhite is coming” is a riff on a portentous line from Game of Thrones, “Winter is coming.”

What sorts of things can you learn by looking at such sites and pages? It’s interesting, for example, that Cliff’s fandom story includes one of many images that were devised by fans for the twitter campaign for Bilbo, one not from Rings or The Hobbit, but from Game of Thrones (right). Ringers would instinctively know that Lord of the Rings fans would be far more likely to read George R.. R. Martin’s book series or watch the TV adaptation than would Twihards. Not only would they recognize the image shown (the character played by Sean Bean, who was Boromir in The Fellowship of the Ring), but they would know that “Snowwhite is coming” is a riff on a portentous line from Game of Thrones, “Winter is coming.”

It is also interesting that TheOneRing.net catered to the slightly older-skewing demographic that is far more important in Rings fandom than in Twilight fandom. As Cliff says: “We have an audience that included older-generation folks who had never used Twitter, so we gave quick and easy instructions to help guide our friends toward their goal.” New Line’s audience research, which originally convinced them that teenaged boys were their primary audience, didn’t reveal that other big audience–which most Ringers would know about.

These little details may not be important in themselves, but picking up many of them from fan discussion adds up to an overall view of characteristics and attitudes. Fans are also quite clear on their likes and dislikes as far as directors and stars go. Just the other day on a thread on TheOneRing.net, Lusitano gave his opinion concerning future possible adaptations of material from Tolkien’s The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales: “If in the future they end up being adapted, it is only sensible to give them to someone else [other than Peter Jackson]. Tim Burton, perhaps? ” Such an adaptation would, I think, be unwise, but a producer who went down that road ought to be interested in that opinion.

Clearly from the way most studios treat most fan sites, they aren’t particularly grateful for any of this. They also don’t seem to recognize that the most devoted fans working for such sites or posting on their own FB pages, YouTube, and Vimeo, have an extraordinary expertise concerning one fandom and often several.

Possibly the studios do closely monitor fansites. Certainly some people in the Rings filmmaking team read TheOneRing.net. When Guillermo del Toro was slated to direct The Hobbit, he even joined the Message Boards and participated in discussions fairly frequently. Naturally the fans adored him for it. If he had stayed on as director, would WB have allowed him to keep up that practice? Probably not unless he cleared every contribution with the studio publicity department.

I’m not saying that cruising online fan outlets would guarantee that the studios would get such a feel for their public that all the films they greenlight would be successes. There are always inexplicable flops. Why did audiences who flocked to Tim Burton and Johnny Depp’s Alice in Wonderland reject the same team when Dark Shadows appeared? Was it just the difference between the sources: a universally known classic book vs. an old TV show with a devoted but small cult following?

Still, when I hear about such incidents as the ones I’ve described here, I can’t help but feel that the fans are a far more valuable source about potential audiences than the studios realize. Why do studios not identify certain particularly knowledgeable and devoted fans as experts and hire them as consultants? Or at least quietly study what they say and do and benefit from it? Maybe then they would know what many of us already know: that the impending failure of some films, like Jack and Hansel and Gretel, is bone obvious from the start.

All this is not to say that Jack the Giant Slayer is a bad film and not worth seeing. It has gotten some surprisingly good, if not rave reviews, though its score on Rotten Tomatoes is only 52% (and 61% among fans). It’s just that WB should have known what they were getting into.