Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Born on the 23rd of July

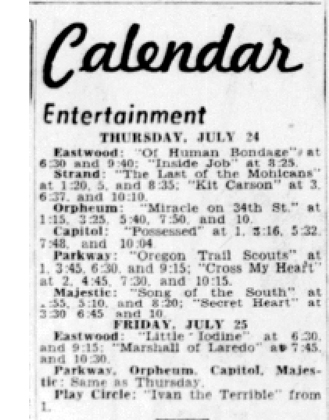

The Wisconsin State Journal, Wednesday 23 July 1947.

DB here:

Today I turn 69. (Please keep the cheers discreet.) I was born in western New York State, but I’ve spent over forty years in Madison, Wisconsin. So for fun I thought I’d take a look at what you could have seen on 23 July 1947 in my current home town.

This isn’t (just) an exercise in baby-boomer self-regard. Looking at the movie ads in the Wisconsin State Journal for that fateful day can remind us of interesting stuff about American cinema of the postwar years. Or so I think, fueled by work on Hollywood in the 40s for a book I’m nearly done with.

Classics, just passing through

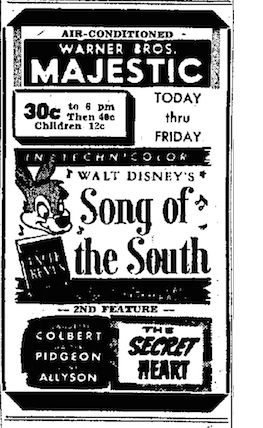

Song of the South (1946).

The first thing that strikes me the quality that’s on offer. On that Wednesday you could have seen four superb films (Rebecca, Stairway to Heaven, Song of the South, Possessed) and two worthwhile pictures (Of Human Bondage and Miracle on 34th Street). These movies are still remembered and admired.

Can this morning’s list of multiplex showtimes promise anything so enduring? Maybe Finding Dory and The BFG will be watched sixty-nine years from now, but our other current releases seem bound for oblivion. And of course the 1947 bill of fare was, with the important exception of Song of the South, designed for grownups.

Those who want to use this 1947 data-point as an example of the death of American cinema are welcome to do so.

Admittedly, today we don’t expect summer to generate the highest-quality films. (Though it often does; think of the last Mad Max installment. And James Schamus’s Indignation is coming up next week.) In 1947 the summer market was rather different from that today. Studios planned their major releases from late August onward, with big pictures playing through fall, winter, and early spring. June, July, and much of August were a slack stretch, when, Hollywood charmingly assumed, people wanted to be outside. So summer releases tended to be minor titles, and exhibitors turned to foreign fare, B pictures, and reissues.

Still, Possessed and Miracle were brand-new releases. At the end of the 40s, it seems clear, studios began releasing more of their important pictures in the summer. And as you can see, air conditioning–rare then, even in public buildings–lured some folks in.

In any case, for moviegoing purposes, I’d rather have been in Madison in July of 1947. In the two weeks sandwiching my birthday (16 July-30 July), I could have seen Brief Encounter, Her Sister’s Secret, Tomorrow Is Forever, Tender Comrade, The Sea Hawk, The Sea Wolf, Dead Reckoning, The Hucksters, The Unfaithful, The Lady in the Lake, Bohemian Girl, Boom Town, The Razor’s Edge, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, Mr. District Attorney, Calcutta, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, Angel and the Badman, The Dark Mirror, Till the Clouds Roll By, Pursued, and Sister Kenny—along with a couple Lone Wolf and Falcon movies. Not a bad lineup. And I’m not counting La Grande Illusion and Ivan the Terrible on the UW campus.

Safety in numbers

Possessed (1947).

Then there’s quantity. Madison, Wisconsin had a population of about 65,000 in the year of my birth. It was dwarfed by Milwaukee, which had nearly ten times that. Yet by my count, over the two weeks around my birthday, a Madison moviegoer had 73 films to choose from. For the same 15-day stretch in town today, I come up with no more than 20. (For both time frames, I’m not counting campus or library screenings.)

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

Of course my 69-year-old self has a much bigger choice of movies than what’s in theatres. I can choose among thousands of titles on cable TV, disc, or streaming. TV wasn’t a significant part of the American landscape in 1947. Cinema existed in an economy of scarcity rather than overabundance.

This circumstance led people to go immediately to see the newest picture, as they couldn’t be sure it would return in second-run or a reissue. Today many of us skip a new release in theatres because we know we can catch it in a later video window. Does this all-you-can-eat plenitude make cinema seem less urgent and immediate—more a matter of “content” filling libraries and bookshelves and hard drives and Netflix queues? I think so. We’re all collectors now, in a way a 1947 moviegoer couldn’t be, but that means we lack the impulsion to see most films immediately. It takes effort to go out to see a film, but maybe that effort makes the experience more valuable (when the movie is satisfying, of course).

Dueling duals

Oregon Trail Scouts (1947).

The ads reveal more about quantity. You’ll have noticed that a great many of the films are playing on double bills (“duals”). From the 1930s on there was a perpetual debate about whether duals helped or hurt the industry. Most studio chiefs deplored them and confidently announced that a majority of audiences didn’t like them. The trade papers regularly ran stories predicting that the dual’s days were numbered.

They were wrong. Duals persisted into my college years; to see Help! (1965) twice in first release without buying another ticket, I had to sit through The Glory Guys (1965). Most exhibitors were independent of the studios, and they liked duals. So, obviously, did many viewers, who enjoyed getting two movies for the price of one.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

The other theatres in the ad are running duals. Some of them ran recent releases, but late in the run. For instance, the Parkway (despite its name, another downtown theatre) was a big venue, with a 1200-seat capacity. On my birthday it screened Cross My Heart (a January ’47 release) and Oregon Trail Scouts (a May release). These were first-run, but with less must-see appeal than Miracle and Possessed. Also, Oregon Trail Scouts is a prototypical B picture, running 58 minutes. So the Parkway, another Fox-controlled screen, mated a mildly attractive Paramount programmer or “nervous A” with a Republic B. A third Fox venue, the Strand, a 1300-seater on the square, drew on second-run titles and reissues for its duals.

The town’s smaller theatres relied on duals. The Majestic, an old vaudeville house with some of the most skewed sightlines in Christendom, was at that point another Warners house. Yet it had no qualms about showing subsequent-run titles from Disney/RKO (Song of the South, in its third Madison run) and MGM (The Secret Heart, back for a second).

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

As a result, in my one-day snapshot every major Hollywood studio is represented; even RKO gets in with its “Passport to Nowhere” short. How can this be, in a town with four Fox screens, two Warners screens, and only one independent exhibitor? Research by our colleague Andrea Comiskey has shown a remarkable flexibility in studio screening policies. Often a subsequent-run house owned by a studio played few or none of the studio’s own releases. This way everybody could make money off everybody else’s movies. Such are the ways of oligopolies.

Why so many B’s, particularly Westerns? Given double bills, they were what the trade papers openly called fodder, and they saved money. B’s were rented on a flat-fee basis, while A’s were rented on a percentage basis. Some exhibitors ran the B more frequently than the A each day, so as to keep more of the box-office take. Such wasn’t the case with the Madison, though: Both Stairway and Vigilante played an equal number of times each day.

Was the B the chaser, clearing the house after the A? Maybe, but maybe someone coming to see a prestigious Powell and Pressburger would stick around for Jon Hall and Andy Devine. In any case, since the Big Five studios were making fewer pictures in the 1940s and were concentrating on A items (the big-ticket income), the ongoing demand for duals helped less important studios, which were heavy suppliers of B’s.

There was only one independent house in Madison proper. The Eastwood (still standing, now a live venue and called the Barrymore) was playing second-runs in its 950-seat auditorium.

Finally, runs were tied to ticket price. I haven’t got good information on ticket costs in these theatres, but the fact that the Majestic boasts of charging $.30 until 6 PM, and then bumps the cost to $.40, is typical of a second-run house of the time. First-run tickets, depending on time of day, could be $.50 or more.

Those costs, by the way, translate to ticket prices between $3.30 and $5.50 in today’s currency. Another data point favoring the good old days.

Heavy rotation

The Middleton Theatre, Middleton Wisconsin, in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Duals multiplied the number of pictures on offer. So did the length, or rather the brevity, of runs.

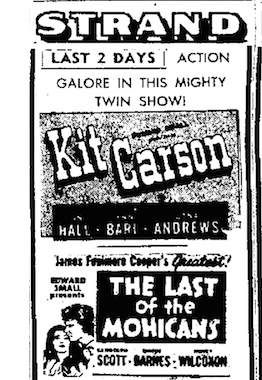

The first-run A’s, Possessed and Miracle on 34th Street, ran a week; Miracle, in fact, was moved over to the Madison at the end of July for a longer stay. But most duals changed more frequently. The Madison’s dual of Tomorrow Is Forever and Tender Comrade ran five days, as did the Strand’s Last of the Mohicans and Kit Carson. But the Parkway typically changed bills every three days, while other theatres split up the week even more. Some programs ran only two days.

We’re so used to pictures hanging on for weeks or months that these rapid playoffs are surprising. But here my birthday snapshot is a bit misleading. Many of the films brought in for two or three days were second-run titles, and a surprising number were reissues.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

The number of reissues increased powerfully just before my birthday. In late May, the Hollywood Reporter claimed that of 224 pictures playing in metropolitan New York, 105 were “oldies.” Just after said birthday, HR reported that “the highly satisfactory boxoffice results from reissues in recent months, plus the necessity of averaging down the cost of new productions which continue to call for multi-million dollar budgets, will result in nearly twice as many reissues in 1947-48 as in the past year.” That number was said to be 75 from the Majors, along with another 100 or so titles already sold or leased by non-Majors.

The oldest reissue on offer in Mad City on my birthday was The Last of the Mohicans (1936), paired with Kit Carson (1940). This package had already had great success in New York and had helped sustain the reissue boom. So strong was this Mighty Twin Show that producer Edward S. Small could demand not the usual flat-rate terms but rather a 35% of the box office. In Madison during the weeks around 23 July, you could have seen a great many other films from the 1930s and 1940s, on brief-stay duals.

Speaking of reissues, the Middleton, the venue announcing Rebecca in the ad, is interesting in its own right. Middleton is a pretty bedroom community west of Madison, then with about 2000 souls. Now, thanks to infill, it’s more or less a continuation of our town. Its theatre, an independent house built in 1946 and with a capacity of 500, ran both second-run and reissues, including, during the DB magic weeks, Sun Valley Serenade (1941), The Westerner (1940), and, for one day, Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942).

Maybe more interesting is that the Middleton was a Quonset hut, with a wraparound roof.

More about the Middleton here. Kristin and I saw E. T. there, and I wish we’d gone more often. It was demolished in 1992.

Foreign accents

A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven, 1946).

The presence of Stairway to Heaven (in first run) points up another trend. During the 1940s, foreign films gained a new prominence on American screens. While reissues were flooding New York City screens as noted, the number of imports among them was sharply up: fourteen British titles, five French, four Spanish, three Italian, two Russian, and one Swedish.

Those proportions reflect the growing popularity of British cinema. At year’s end, Variety noted that the number of British releases in 1947 doubled from the previous year, from ten to twenty. In the two weeks surrounding my birthday, Madisonians could have seen Brief Encounter, also at the Madison. The Madison seems to have sometimes operated as an art house. It screened Open City a month earlier, promoted in a memorable ad that somehow plays up sexytime without showing Anna Magnani.

Note what’s playing with it. The Madison stayed classy.

1946 was the high-water mark of American movie attendance and Hollywood studio profits. 4.7 billion US tickets were sold, and profits came to nearly $120 million. Attendance remained strong in 1947, but profits started to fall steeply, to about $87 million. The soaring costs of production, including millions spent on rights to projects that were never filmed, came due. And soon enough attendance dropped calamitously as well. Ticket sales in 1952 were only a bit more than half of 1946’s total. A great many Americans stopped going to the movies.

There were rumblings, though, before I showed up. “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” announced the headline of Hollywood Reporter for 20 May 1947. Was this just a “spring slump,” such as those before World War II, when good weather drove people outside? “If there is no general rise in grosses by the middle of July,” said one executive, “then our fears will have been realized, as it will reflect an economic crisis.” Studio employment was off 20%; the Majors’ building plans were put on hold; and reissues from non-Major sources were gaining a bigger share of the receipts. Ultimately, 1947 fell off only a little, but film folk were nervous. The big dip would come soon.

Another crisis: In less than a year after my birthday the Supreme Court would declare that the studios’ ownership of theatres was monopolistic, and the companies would begin gradually splitting off their theatre chains.

I was born, then, on a sort of cusp. By the time I was 5, people were declaring the studio system dead. Knowing nothing of this, I continued watching new releases (Peter Pan, Francis the Talking Mule movies) and old films that were starting to show up on TV. I didn’t suspect that, decades along, I would spend my more-or-less adult life studying those movies that played the Capitol, the Parkway, and the Middleton. Just looking at this page from the State Journal has me hoping that Kristin gets me a time machine for my next birthday.

For help in preparing this entry, thanks to Lea Jacobs, Jeff Smith, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Lisa Marine, and Rob Thomas.

Some sources: “Double-Bill Reissue Packages Prove Surprising B.O. on B’way,” Variety (9 April 1947), 7, 18; “Re-Issues Flood New York Screens,” Hollywood Reporter (22 May 1947), 1, 3; “Reissues Doubled for 1947-48,” HR (26 August 1947), 1, 11;”Industry Schedules 130 Re-Releases for This Year,” HR (5 February 1948), 1, 13; “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” HR (20 May 1947), 1, 12; “Industry in Crucial Period before Upturn, Say Toppers,” HR (26 May 1947), 1, 12; “July Will Disclose Actual Extent of Boxoffice Downturn,” HR (9 June 1947), 10; “8 Majors and 4 Lesser Distribs Released 428 in ’47 vs. 405 in ’46,” Variety (31 December 1947), 6. Chapter 6 of Susan Ohmer’s book George Gallup in Hollywood (Columbia University Press, 2006) provides an excellent overview of the disputes about double bills.

There was another crisis in my late prenatal phase. In response to shopkeepers, the ever-watchful Wisconsin state legislature had drafted a bill banning candy, food, and drink from being sold in movie houses. Exhibitors mobilized and lobbied for tasty snack treats. “With boxoffice grosses rapidly slipping from their wartime peaks to pre-war levels, the candy, popcorn, sandwich and soft drink sales now are especially essential to keep the houses on the profit side of the ledger.” “Wisconsin Candy Sale Ban Doomed,” HR (7 May 1947), 5. Fortunately for all Cheeseheads, this bill was defeated.

Browsing the wonderful site Cinema Treasures can make you aware of all those lost movie houses. The Wisconsin Historical Society presents many photos of Madison’s old theatres. My photo of the Middleton in the 70s comes from this collection, Reference no. 5572.

The saga of Madison’s Orpheum is told in part here, though an update on all the intrigue is probably in order. At least the magnificent sign has been redone and has gone up. The Capital Times covers the process here and here. The refurbished sign got lit up last night. For more on local theatres, including the ones I actually frequented back East, go here and here. Also relevant is this visit to Rochester’s Cinema Theatre, with information from Andrea Comiskey. Also a cat.

On the importing of movies from overseas at this period, the definitive source is Tino Balio’s book The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010).

P.S. 30 July 2016: The Middleton Theatre stirs fond memories. See Nadine Goff’s Facebook page on historic Wisconsin photographs for reminiscences of sticky floors and rain on the roof.

Another fateful birthday headline.

Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop

Ant-Man 2: This time it’s personal. Not that it wasn’t before. But now it’s personal and expensive.

DB here:

Sean Parker, the Napster founder who taught everybody that digital piracy means never having to say you’re sorry, has come up with a new killer app. Called The Screening Room, the pitch is catching the eye of an industry that thrives on finding new niches for its product.

Stuff you probably already know

Recall, as background, that Hollywood’s economic model depends on two conditions.

(1) Strong Intellectual Property measures, both technological and legal. (Intellectual is to be taken in a broad sense here. It includes Paul Blart movies.) Encryption is designed to protect DVDs, streaming, and the Digital Cinema Package that plays in your local multiplex. Law enforcement, under the auspices of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, backs up anti-piracy with fines and jail time.

(2) Price discrimination. The premise of the classic vertically-integrated studio system was that people will pay more to see a movie sooner than other people. Why this is true still mystifies me, but facts are facts. Hence the old system of “runs.” First-run movies demanded top dollar, then second runs were at lower prices, and subsequent runs were still cheaper. When the studios surrendered their theatre ownership, the runs system remained roughly in place, chiefly because most films were platform released, playing the big cities before gradually expanding to the provinces. And network TV was basically the only ancillary market. But wide releases–hundreds or even thousands of copies playing everywhere–became the industry norm as cable, home video, and other technologies came along. The run system was reborn, and price discrimination became much more fine-grained.

Known, confusingly, as “windows,” phases of the film’s life are assigned to various platforms. After the theatrical window, typically 90 days after release, there are windows for airline/hotel access, disc (DVD, Blu-ray), Pay-per-View, streaming, cable, and on down the line. The order of these windows for any one title can vary somewhat, depending on negotiations. Most of them are designed to define price points scaled along a curve: how much it’s worth to somebody to see the movie at intervals after the initial theatrical release. By the time a movie comes to free cable, you’ve pretty much squeezed everything out of it, though the industry relies very extensively on worldwide cable purchases.

The studios depend on the theatrical release, but not because it’s the biggest source of revenue. (For the top films it can yield a lot, of course, but most films don’t recoup their costs in that window.) The theatrical release builds awareness, making it stand out downstream in the ancillaries. Without theatrical release, a film needs a lot of publicity to draw notice. Witness all those films on your Netflix or Hulu menu, all those John Cusack movies you didn’t know existed.

Independent films are increasingly relying on day-and-date release between a mild theatrical run and some form of Video on Demand. Other indie titles, along with foreign ones, are going wholly VOD, and the big players–Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon–are vigorously buying titles and backing new projects against the looming day when the studios will license fewer blockbusters to them.

The studios need the theatre chains as a shop window for their top-tier product. The theatre chains obviously need the studios to keep crowds flowing in. But some parties have flirted with day-and-date theatrical/VOD. Most famously Ted Sarandos of Netflix argued for it in 2013, then had to backtrack a few days later. On the studio end, Universal in 2011 proposed softening the theatrical window by offering Tower Heist on “premium VOD.” The plan was to drastically cut into the theatrical window by making the film available after three weeks of release, for the hefty price of $59.95. Theatre owners threatened to boycott the film, and filmmakers howled in protest. Many feared that it was the thin edge of a wedge that would eventually, through price wars, shorten windows and lower prices–not to mention wreck theatre attendance. The idea was quickly dropped.

No bad idea ever goes away, as we learn from claims that tax cuts create jobs and that we’re just one intervention away from creating peace in the world. Thanks to Parker, we now have Premium VOD in a new guise. That means a new window, with corresponding price discrimination.

Premium VOD, steroidal

Last week, The Screening Room project, sponsored by Parker and entrepreneur Prem Akkaraju, was made public. Brent Lang of Variety outlined the plan circulating among the major players.

Individuals briefed on the plan said Screening Room would charge about $150 for access to the set-top box that transmits the movies and charge $50 per view. Consumers have a 48-hour window to view the film.

To get exhibitors on board, the company proposes cutting them in on a significant percentage of the revenue, as much as $20 of the fee. As an added incentive to theater owners, Screening Room is also offering customers who pay the $50 two free tickets to see the movie at a cinema of their choice. That way, exhibitors would get the added benefit of profiting from concession sales to those moviegoers.

Participating distributors would also get a cut of the $50-per-view proceeds, also believed to be 20%, before Screening Room took its own fee of 10%.

Parker assures all stakeholders that the magic box would assure maximum antipiracy controls.

Since then, developments have been swift. Peter Jackson, Ron Howard, and J.J. Abrams are supporting the plan, while James Cameron is opposing it. The Cinemark and Regal chains, at this point the biggest theatre chains in the country, are against it, but there are hints that AMC, soon to be the biggest chain in the world if it’s allowed to purchase Carmike, might be interested. As for studios, Universal, Sony, and Fox are rumored to be considering the prospect. Once the give-and-take of dealmaking gets under way, there’s no telling what a final arrangement might look like.

What’s transparently clear is the opposition of the art-house sector. Tim League of Alamo Drafthouse issued the first warning on Monday, calling The Screening Room a “half-baked” idea. Today the Art House Convergence, an association of 600 theatres, issued a severe criticism of Parker’s plan. The open letter has been summarized in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. Indiewire has published it in its entirety, and I do the same, as follows.

The Art House Convergence, a specialty cinema organization representing 600 theaters and allied cinema exhibition businesses, strongly opposes Screening Room, the start-up backed by Napster co-founder Sean Parker and Prem Akkaraju. The proposed model is incongruous with the movie exhibition sector by devaluing the in-theater experience and enabling increased piracy. Furthermore, we seriously question the economics of the proposed revenue-sharing model.

We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model, nor are we arguing for the decrease in home entertainment availability for customers – most independent theaters already play alongside VOD and Premium VOD, and as exhibitors, we are acutely aware of patrons who stay home to watch films instead of coming out to our theaters.

Rather, we are focused on the impact this particular model will have on the cinema market as a whole. We strongly believe if the studios, distributors, and major chains adopt this model, we will see a wildfire spread of pirated content, and consequently, a decline in overall film profitability through the cannibalization of theatrical revenue. The theatrical experience is unique and beneficial to maximizing profit for films. A theatrical release contributes to healthy ancillary revenue generation and thus cinema grosses must be protected from the potential erosion effect of piracy.

The exhibition community was required to subscribe to DCI-compliance in a very material way – either by financing through VPF integrators (and those contracts have not yet expired) or by turning to other models which necessitated substantial time and commitment. Those exhibitors who were unable to make the transition were punished by a loss of product. The digital conversion had a substantial cost per theater, upwards of $100,000 per screen, all in the name of piracy eradication and lowering print, storage and delivery costs to benefit the distributors. How will Screening Room prevent piracy? If studios are concerned enough with projectionists and patrons videotaping a film in theaters that they provide security with night-vision goggles for premieres and opening weekends, how do they reason that an at-home viewer won’t set up a $40 HD camera and capture a near-pristine version of the film for immediate upload to torrent sites?

This proposed model would negate DCI-compliance by making first-run titles available to anyone with the set-top device for an incredibly low fee – how will Screening Room prevent the sale of these devices to an apartment complex, a bar owner, or any other individual or company interested in creating their own pop-up exhibition space? We must consider how the existing structures for exhibition will be affected or enforced, including rights fees, VPFs and box office percentages.

A model like this will also have a local economic impact by encouraging traditional moviegoers to stay home, reducing in-theater revenue and making high-quality pirated content readily available. This loss of revenue through box office decline and piracy will result in a loss of jobs, both entry level and long-term, from part time concessions and ticket-takers to full time projectionists and programmers, and will negatively impact local establishments in the restaurant industry and other nearby businesses. How many of today’s filmmakers started their careers at their local moviehouse?

There are many unanswered questions as to how this business model will actually work. The proposed model, as we have read in countless articles, suggests exhibitors will receive $20 for each film purchased. At first glance, an exhibitor may think it represents a small, but potentially steady, additional revenue stream. But how will this actually be divided among the number of theaters playing the purchased title; will exhibitors who open the title receive more than an exhibitor who does not get the title until several weeks later (based on a distributor’s decision); who will audit the revenue to ensure exhibitors are being paid fairly; does this revenue come from Screening Room or from the distributor… these are just a few of the issues yet to be explained.

Similarly, Screening Room promises to give each subscriber two free cinema tickets with each film purchase. Yet to be disclosed is how an exhibitor will recoup the value of those tickets from Screening Room so they can then pay the percentage of box office revenue owed to the distributor of the film. Yet to be explained is who will manage the ticket program details such as location choice, method of purchase, and so on. Will all exhibitors be expected to honor Screening Room free tickets, or will some exhibitors receive preferential treatment over others?

We strongly urge the studios, filmmakers, and exhibitors to truly consider the impact this model could have on the exhibition industry. We as the Art House and independent community have serious concerns regarding the security of an at-home set-top box system as well as the transparency and effectiveness of the revenue-sharing model. Our exhibition sector has always welcomed innovation, disruption and forward-thinking ideas, most especially onscreen through independent film; however, we do not see Screening Room as innovative or forward-thinking in our favor, rather we see it as inviting piracy and significantly decreasing the overall profitability of film releases.

At this time and with the information available to us we strongly encourage all studios to deny all content to this service.

One point of clarification. Some reports have interpreted the paragraph beginning “We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model…” as meaning that art-house programmers, managers, and owners are okay with day-and-date VOD. But many Art Housers wish that day-and-date VOD had been strangled in its cradle. For those people, “not debating” doesn’t mean “accepting” or “not disputing.” It means that this is not the occasion for taking issue with that feature of the concept, as the Parker proposal introduces serious problems of its own.

The churn around this proposal is turbulent; stories kept popping up as I was writing the entry. A useful update is here. To keep up to speed, you may want to visit these two summative links, one for Variety and the other for The Hollywood Reporter.

There were, and are, still second-run movie houses. To my joy, Ant-Man, released last summer, has been playing for at least seven months at our second-run house here in Madison. And in 35! Is this a record in modern times? Also, too: My Ant-Man image up top comes from the first film, not the sequel, which doesn’t yet exist. I was just fooling and pretending.

What’s the Art House Convergence? Visit their site here. My visit to their annual confab is recorded here. An updated version is available in Pandora’s Digital Box.

THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth

DB here:

By now everybody knows that Tarantino’s forthcoming The Hateful Eight was shot on film in the Ultra Panavision 70 format. This anamorphic widescreen process yields a projected aspect ratio of 2.76–in a word, humongous. An early version of it, MGM Camera 65, was employed on Ben-Hur (1959), but Panavision quickly developed a new generation of cameras and renamed the process. It wasn’t heavily used; supposedly Khartoum (1966) was the last film shot in the format.

The process by which Tarantino, ace cinematographer Robert Richardson, and the enthusiastic boffins at Panavision revived Ultra Panavision 70 is detailed in the current American Cinematographer (alas, not yet online). The production is an extraordinary tale. But what about exhibition? Luckily, the widescreen fans among us can glean a lot about that from veteran projectionist Paul Rayton’s interview with Chapin Cutler, co-owner of Boston Light & Sound. It was the task of Chapin and his team to find over 100 projectors, refurbish them, test them, and set them up in theatres all over America.

Chapin is a legendary figure in movie exhibition. Trained as a projectionist during his college years, he and Larry Shaw have made BL&S one of the very top companies for installation and maintenance of theatre projection equipment. He has supervised theatrical setups at festivals (Sundance, Telluride, TCM), industry gatherings (CinemaCon), and at some of the world’s top-notch theatres.

He’s more than a professional’s professional: He loves film and prides himself on delivering a powerhouse show. He was a natural choice for a movie geek like Tarantino to arrange the roadshow screenings of The Hateful Eight.

Chapin has discussed the nearly military precision necessary to fulfill Tarantino’s mandate in The New York Times and The Boston Globe. You should read these pieces for essential background. When Chapin added some new information courtesy of the listserv of the Art House Convergence, I jumped at the chance to include you in the audience. I know that many of our readers are keen to devour whatever they can learn about this film, one of the year’s major American releases.

So here are Chapin’s notes on how you prepare and ship out 100+ 70mm film prints.

For those of you that are interested in these things, attached is a picture of our “platter farm” in Valencia CA. This is where all the prints are being made up.

The space before, in Academy ratio.

The space after, in sort of Ultra Panavision.

We are getting the prints as 1000 ft. loads, so we have to assemble 20 rolls to make a print up.

About 90 of the prints will be made up for platter operation and shipped totally assembled. The prints are being ultrasonically welded so that it is one continuous piece of film; no splices. The remaining prints are going out for reel to reel houses.

On the right of the frame above you can see part of one of the shipping cases. It is 5 ft. x 5 ft. by 1 ft. thick. When loaded, it weighs about 400 lbs. On the platter next to it, there is a partially disassembled platter reel. With the reel full, out of the box, the film and reel weigh about 250 lbs. Four people can easily lift it onto a platter deck.

We have a dedicated team of four folks working 7 days a week to get this done.

All this makes you appreciate the effort behind the scenes that makes this remarkable enterprise work. (So far, there have been a couple of problematic press screenings, but a dozen or so other shows–notably last night’s SAG screening at the Egyptian–have gone off perfectly.) Whatever you think of Tarantino as a filmmaker (I like him), he deserves credit for exposing a new generation to the volcanic fun of a roadshow presentation. And we should thank Chapin, the guru with the bandit mustache, as well.

Photo credits: Chas. Phillips.

The Hateful Eight.

Ode to the New Beverly; and a downbeat coda

Out of Print (2014).

DB here:

Out of Print is a new documentary (on 35!) by Julia Marchese about a hallowed Los Angeles theatre, the New Beverly. The film has gone up on Vimeo here.

It’s a portrait of a theatre and its history. It’s also a portrait of a team that is a community that is a family that is a way of life for hundreds of people. The film includes interviews with Joe Dante, Stuart Gordon, and other friends of our blog.

After she finished the film, Ms Marchese found herself in a very different situation at the theatre. She explains here.

We haven’t heard the last of this, I expect. In the meantime, netizens are rushing to watch the movie, which is indeed enjoyable. In its late sections it constitutes a plea for retaining and circulating 35mm prints as well as digital copies. It’s also an invigorating testament to revival and repertory cinemas and to the creativity of programmers.

Thanks to John Toner of Renew Theaters for the link!