Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

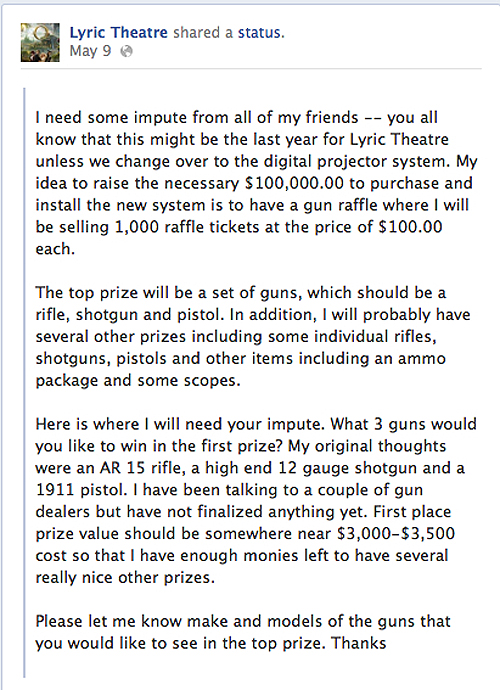

The annals of showmanship: Any popcorn or ammo with your Pepsi?

Pandora’s digital box: End times

35mm projection booth at Market Square Cinema, Madison, Wisconsin; 10 May 2013.

DB here:

When exactly did film end? According to the mass-market press, here are some terminal dates.

July 2011: Technicolor closes its Los Angeles laboratory.

October 2011: Panavision, Aaton, and Arri all announce that they will stop manufacturing film cameras.

November 2011: Twentieth Century Fox sends out a letter asserting that it will cease supplying theatres with 35mm prints “within the next year or two.”

January 2012: Eastman Kodak files for bankruptcy protection.

March 2013: Fuji stops selling negative and positive film stock for 35mm photography.

Each of these events looked like turning points, but now they seem merely phases within a gradual shift. After all, the digital conversion of cinema has been in the works for about fifteen years. The key events–the formation of a studio consortium to set standards, the cooperation of technical agencies and professional associations, the lobbying for 3D by top-money directors–didn’t get as much coverage. Because so many maneuvers took place behind the scenes and unfolded slowly, digital cinema seemed very distant to me. To understand the whole process, I had to do some research. Only in hindsight did the quiet buildups and sudden jolts form a pattern.

On the production end, it seems likely that filmmakers will continue to migrate to digital formats at a moderate pace. Proponents of 35mm are fond of pointing out that six of 2012’s Oscar-nominated pictures were shot wholly or partly on film. (To which you might well respond, Who cares about Oscar nominations? I would agree with you.) Yet even 35mm adherent Wally Pfister, DP for Christopher Nolan, admits that within ten years he will probably be shooting digital.

What about the other wings of the film industry, distribution and exhibition? Put aside distribution for a moment. Digital exhibition was the central focus of the blog series that became my e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. There I try to trace the historical process that led up to the big changes of 2009-early 2012.

Today, a year after Pandora’s publication, everybody knows that 35mm exhibition of recent releases is almost completely finished. But let’s explore things in a little more detail, including poking at some nuts and bolts. As we go, I’ll link to the original blog entries.

Top of the world!

35mm print of Warm Bodies about to be shipped out from Market Square Cinemas, Madison, Wisconsin; 10 May 2013.

The overall situation couldn’t be plainer. At the end of 2012, reports David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest, there were nearly 130,000 screens in the world. Of these, over two-thirds were digital, and a little over half of those were 3D-capable.

Northern European countries have committed heavily to the new format. The Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway are fully digital, while the UK is at 93% saturation and France is at 92%. Both national and EU funds have helped fund the switchover. Hancock reports that in Asia, Japanese screens are 88% digital, and South Korean ones are 100%. China is the growth engine. Rising living standards and swelling attendance have triggered a building frenzy. Over 85%, or 21,407 screens are already digital, and on average, each day adds at least eight new screens.

In the US and Canada, there were at end 2012 still over 6400 commercial analog screens, or about 15% of the nearly 43,000 total. My home town, Madison, Wisconsin, has a surprising number of these anachronisms. One multiplex retains at least two first-run 35mm screens. Five second-run screens at our Market Square multiplex have no digital equipment. That venue ran excellent 2D prints of Life of Pi (held over for seven weeks) and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. It’s currently screening many recent releases, including the incessantly and mysteriously popular Argo. In addition, our campus has several active 35mm venues (Cinematheque, Chazen Museum, Marquee). Our department shows a fair amount of 35mm for our courses as well; the last screening I dropped in on was The Quiet Man in the very nice UCLA restoration.

Unquestionably, however, 35mm is doomed as a commercial format. Formerly, a tentpole release might have required 3000-5000 film prints; now a few hundred are shipped. Our Market Square house sometimes gets prints bearing single-digit ID numbers. Jack Foley of Focus Features estimates that only about 5 % of the copies of a wide US release will be in 35mm. A narrower release might go somewhat higher, since art houses have been slower to transition to digital. Focus Features’ The Place Beyond the Pines was released on 1442 screens, only 105 (7%) of which employed 35mm.

In light of the rapid takeup of digital projection, Foley expects that most studios will stop supplying 35mm copies by the end of this year. David Hancock has suggested that by the end of 2015, there won’t be any new theatrical releases on 35mm.

Correspondingly, projectionists are vanishing. In Madison, Hal Theisen, my guide to digital operation in Chapter 4 of Pandora, has been dismissed. The films in that theatre are now set up by an assistant manager. Hal was the last full-time projectionist in town.

The wholesale conversion was initiated by the studios under the aegis of their Digital Cinema Initiatives corporation (DCI). The plan was helped along, after some negotiation, by the National Association of Theatre Owners. Smaller theatre chains and independent owners had to go along or risk closing down eventually. The Majors pursued the changeover aggressively, combining a stick—go digital or die!—with several carrots: lower shipping costs, higher ticket prices for 3D shows, no need for expensive unionized projectionists, and the prospect of “alternative content.”

The conversion to DCI standards was costly, running up to $100,000 per screen. Many exhibitors took advantage of the Virtual Print Fee, a subsidy from the distributors that paid into a third-party account every time the venue booked a film from the Majors. There were strings attached to the VPF. The deals are still protected by nondisclosure agreements, but terms have included demands that exhibitors remove all 35mm machines from the venue, show a certain number of the Majors’ films, equip some houses for 3D, and/or sign up for Network Operations Centers that would monitor the shows.

The biggest North American chains are Regal, AMC, and Cinemark. They control about 16,500 screens and own fifty-three of the sixty top-grossing US venues. The Big Three benefited considerably from the conversion. By forming the consortium Digital Cinema Solutions, they were able to negotiate Wall Street financing for their chains’ digital upgrade. They also formed National Cinemedia, a company that supplied FirstLook, a preshow assembly of promos for TV shows and music. Under the new name of NCM Network, the parent company now links 19,000 screens for advertising purposes. NCM also supplies alternative content to over 700 screens under the Fathom brand: sports, musical acts, the Metropolitan Opera, London’s National Theatre, and other items that try to perk up multiplex business in the middle of the week.

The digital conversion has coincided with—some would say, led to—a greater consolidation of US theatre chains. Last year the Texas-based Rave circuit was dissolved, and 483 of its screens, all digital, were picked up by Cinemark. More recently, the Regal chain gained over 500 screens by acquiring Hollywood Theatres. The biggest move took place in May 2012 when the AMC circuit was bought for $2.6 billion by Dalian Wanda Group, a Chinese real estate firm. Combined with Wanda’s 750 mainland screens, this acquisition created what may be the biggest cinema chain in the world. Wanda has declared its intent to invest half a billion dollars in upgrading AMC houses.

Meanwhile, vertical integration is emerging. In 2011, Regal and AMC founded Open Road Films, a distribution company. It has handled such high-profile titles as The Grey, Killer Elite, End of Watch, Side Effects, and The Host. Cinedigm, which began life as a third-party aggregator to handle VPFs, has moved into distribution too, billing itself as a company merging theatrical and home release strategies tailored to each project.

It has become evident that the digital revolution in exhibition permits American studio cinema a new level of conquest and control. Distribution, we’ve long known, is the seat of power in nearly all types of cinema. Whatever the virtues of YouTube, Vimeo, and other personal-movie exhibition platforms, film’s long-standing public dimension, the gathering of people who surrender their attention to a shared experience in real time, is still largely governed by what Hollywood studios put into their pipeline.

On the margins and off-center

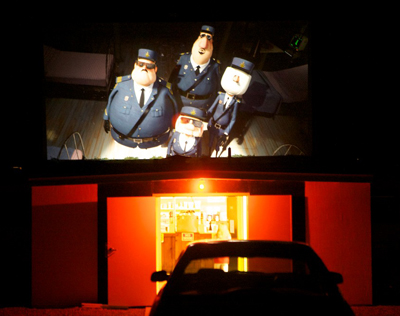

View of Madagascar from the Sky-Vu Drive-In, 2012. Photo by Duke Goetz.

While the Big Three grew stronger, what became of smaller fry? John Fithian of NATO suggested that any cinema with fewer than ten screens could probably not afford the changeover, and David Hancock suggested that up to 2000 screens might be lost. Recent speculation is that drive-ins will be especially hard hit. Pandora’s Digital Box, as blog and then book, surveyed those most at risk: the small local cinemas and the art houses.

I fretted about the loss of small-town theatres, not least because I grew up with them. Data on such local venues are hard to get, so for the blog and the book I went reportorial and visited two Midwestern towns. The blogs related to them are here and here.

The long-lived Goetz theatres in Monroe, Wisconsin, consist of a downtown triplex and the Sky-Vu drive-in. They’re run by Robert “Duke” Goetz, whose grandfather built the movie house back in 1931. Duke is a confirmed techie and showman. He designs and cuts ads and music videos to fill out his show, and he personally converted all his screens to 7.1 sound. So it’s no surprise that he’s a fan of digital cinema. But back in December his digital upgrade took place during the worst box-office weekend since 2008–a bad omen, if you believe in omens.

Seventeen months later, Duke reports more cheerful news. Everything has gone according to plan and budget. The company that installed the equipment, Bright Star Systems of Minneapolis, has proven reliable and excellent in answering questions. Duke especially likes the fact that digital projection allows him to “play musical chairs with the click of a mouse.”

I can move movies from screen to screen in short order or download from the Theatre Management System to any and all theatres at one time, so when the weather is damn cold, for Monday -Thursday screening I’ll play the shorter movies in the biggest house. . . . I am now able to start the movies from the box office with software that accesses the TMS, so it’s just like being at the projector. It saves my guys time and keeps them where the action is.

Duke programs his offerings to suit the tastes of the town, and for the most part, he can get the films he wants. Attendance at the three-screener has increased, partly, he thinks, because of digital. Even marginal product gets a bit more attention when people find the image appealing. Duke says that Skyfall played so long and robustly partly because it was a strong movie, but also because the presentation was compelling. Thanks to his subwoofer, viewers could feel onscreen shotgun blasts in their backsides. Immersion goes only so far, however. Duke remains leery of 3D: “People are tired of paying the extra charge, and with the economy in my area I’ll still wait.”

Contrary to trends elsewhere, the Sky-Vu has benefited strongly from digital display. Duke’s was the first North American drive-in to sign up for the NEC digital system. People comment on how the bright, sharp image has improved their experience. The drive-in had “a tremendous summer,” with the first Saturday night of Brave, coupled with Avengers, proving to be the best night of the year. Measured by both box office returns and number of admissions, that show did better than Transformers the summer before. Last fall, when the Sky-Vu was the only area drive-in still open, some patrons traveled 2 1/2 hours from Illinois. The only problem with digital under the stars was that Duke couldn’t get a satisfactory VPF deal for an outdoor cinema because he doesn’t run it year-round.

While Duke runs the Goetz theatres as a family business, the JEM Theatre in Harmony, Minnesota is more of a sideline for its owner-operator Michelle Haugerud. A single screen running only at 7:30 on weekend nights, the JEM plays a unifying role in the life of the town. But it’s a small market. Harmony consists of only 1020 people (many of them Amish), and the median household income is about $30,000. Michelle had to finance the conversion through donations and bank assistance. The task was complicated by the unexpected death of her husband Paul, who ran the JEM with her.

Michelle reports that the digital conversion hasn’t increased business. Box office was about the same in 2012 as in 2011, and so far this year ticket sales have been down. It has been a slow winter and spring throughout the industry, and people are hoping the summer blockbusters will lift revenues. But the JEM faces particular problems that the Goetz doesn’t.

Michelle wants to show films in first run, as Duke does. But the distributors typically demand that she play a new movie for three weeks. That’s not feasible in her small town, so Michelle winds up missing out on films she knows would draw well. In addition, she’d be willing to screen two shows a day, the first a kid movie and the second an adult picture, but the companies don’t allow this double-billing. Moreover, she thinks that the shrinking windows–the speed with which films come out on Pay Per View, VOD, and DVD–are eroding her audience. “Many people are willing to wait for these releases since they now realize they will be out shortly after they hit the theatres anyway.”

Michelle and her family run the JEM as much for the community as for themselves. She is hoping for better times.

Converting to digital has made showing movies easier, and I have had no issues with the new equipment. However, it has not helped with ticket sales at all. I am holding on and committed to this year, but if I get to the point where it is costing me personally to stay open, I don’t think I will continue. I love having the movie theatre and would love to keep it going. I do feel if I had a say on what movies I showed and when, I would do so much better.

Kickstarting the arthouse

Robert Redford addresses the Art House Convergence, January 2013.

Several managers and programmers of arthouse cinemas around the country have formed an informal association, the Art House Convergence. It meets once a year just before the Sundance Film Festival, which many members attend. When I visited the conference in 2012, the digital transition was the central topic. It aroused curiosity, bewilderment, frustration, and some annoyance. This year, things were different.

Participants were calmly reconciled to the inevitable, and some looked forward to it. On one of the few panels that took up the subject, moderator Jan Klingelhofer of Pacific Film Resources began by asking: “How many of you are still on the fence about digital?” Just one hand was raised.

On the panel, technology experts from major companies showed how new projection systems could be installed even in offbeat venues. The New Parkway in Oakland was once a garage, and the Mary D. Fisher Theatre in Sedona is a converted bank. Panelists also gave information on choices of technology, from lamps and servers to the best screen materials for 3D. The teeth-gnashing is over, and now art-house leaders are focusing on practicalities: the best strategies suited for their business models.

A private, for-profit art house faces many of the problems faced by Duke Goetz and Michelle Haugerud, except that the art-house is screening films of narrower appeal. Because the audience is smaller and more select, many art houses have become not-for-profit entities created by community cultural organizations. They are dependent on donations, private or public patronage, and miscellaneous income from many activities, not only screenings but filmmaking classes, special events, and other activities. A good example of the diversity of outreach an arthouse can have is the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, whose director, the estimable Juliet Goodfriend, also coordinates the annual AHC survey. So the coordinators of the not-for-profit theatre must persuade boards of directors and generous patrons that the digital upgrade is necessary.

Small venues, whether private or not-for-profit, can’t benefit much from economies of scale. A multiplex can amortize its costs across many screens, but a big proportion of art houses boasts only one or two. Add to this the fact that multiplexes are encroaching on the art-house turf with crossover films like Moonrise Kingdom and upscale entertainment like opera and plays from Fathom. Even museums are starting to install digital equipment and play arts-related programming.

The chief task, of course, is paying for the upgrade. Last year’s AHC session was often about the money. Small local cinemas like the Goetz could benefit from VPF deals, but for many art houses such deals weren’t a good option. These houses don’t run enough films from the Majors to repay the subsidy. While they’re often eager to take something from Fox Searchlight, Focus Features, and the Weinstein company, they book a lot from IFC, Magnolia, and other independent distributors.

A common solution was to launch fundraising campaigns from the community, much as Michelle did in Harmony. One of the biggest initiatives was that conducted by the boundlessly energetic John Toner and Chris Collier of Renew Theaters in Pennsylvania. Without going for a VPF, they raised $367,000 to pay for converting three screens (one in 3D). John and Chris are vigorous advocates for the new format, and their “This Is Digital Cinema” series treats restorations of classics like Gilda and The Ten Commandments as showcases for the DCP. At AHC 2013, John and Chris provided an entertaining PowerPoint presentation on how they managed the switchover; for a prose version, you can read John’s account here.

Likewise, the Tampa Theatre raised $89,000 from its community. But what if your community can’t sustain such a big campaign? I hadn’t predicted in Pandora how powerful Kickstarter would be in the film domain, and the results are initially encouraging. Donations to the Cable Car Cinema and Cafe of Providence surpassed the goal by six thousand dollars, and the theatre is already preparing for the new equipment. The final 35mm program will be, what else?, The Last Picture Show, complete with pulled-pork sandwiches. The Crescent Theatre of Mobile won nine thousand more than it asked for, and Martin McCaffrey, venerable moving spirit of Montgomery’s Capri Theatre, followed suit and came out ahead by about the same amount.

Currently the Kickstarter site lists dozens of conversion projects, and many have met their goals–with Boston’s Brattle and LA’s Cinefamily hitting over a hundred thousand dollars. The pitches are pretty creative (“The Cinefamily is a non-profit movie theater with awesome programming, but crappy everything else”) and so are the giveaways (the Skyline drive-in of Everett, Washington offers a vintage speaker box that’s “clean and suitable for presentation”).

So maybe predictions were too pessimistic. Will we lose so many theatres to the switchover? Maybe not. But raising money for the initial conversion isn’t the whole story.

Technology: Running in place to keep up?

In the shift to digital projection, some would say the pivotal moment came with the success of Avatar and other 2009 3D releases (Monsters vs. Aliens, Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs, and Up). In 2009 there were about 7400 digital screens; a year later there were nearly 15,000. Then the acceleration began. Ten thousand screens converted in 2011 and eight thousand more the following year.

But I see 2005 as another major marker. In 2004, there were only 80 digital screens in the US. By the end of 2005, there were over 1500. The early adopters were pushed by the emergence of 3D, heavily touted by several major directors at NATO’s annual convention and the strong 3D releases of The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005). So there were two bursts of digital adoption, both driven by 3D.

With 3D as a Trojan horse, digital entered exhibition. The format eventually settled on was the Digital Cinema Package, an ensemble of files gathered on a hard drive. The movie, with subtitles and alternate soundtracks, is wrapped in a thick swath of security files. The studios, petrified of piracy, had delayed the completion of digital cinema for some years until an ironclad system was protecting the movie. The DCP can be opened only with a customized key, delivered to the theatre separately from the hard drive. Typically the key is sent on a flash drive, so that the staff member need not retype the tediously long string of alphanumeric characters that make it up. Copying that key into the theatre’s server, its theatre management system, or the projector’s media block allows the film to be played on a certified projector.

A digital projector suitable for multiplex use relies on one of two available technologies. Sony’s proprietary system works only on its own projectors. Texas Instruments’ Digital Light Processing (DLP) technology was licensed to three manufacturers: Christie, Barco, and NEC. By fall 2010, all four companies had produced high-level, and quite expensive, machines capable of producing 4K displays. The rush to convert led to thousands of units being bought over a few months. This was great for business in the short term, but how could the manufacturers count on selling the product in the years and decades ahead? Michael Karagosian sketches the problem: “The big challenge today for technology companies is the massive downturn in sales that is destined to take place the last half of this decade as the digital installation boom ends.”

One way to expand the market was offered by cheaper machines. In fall of 2012, all the manufacturers introduced DCI-compliant projectors suitable for screens around thirty feet wide. The machines were still quite expensive, but they were marginally more affordable for the smaller or independent exhibitors who had been reluctant to convert or who had missed the deadlines for VPF financing. To maintain a quality difference from high-end machines, the cheaper versions typically lacked some features. They might be capable of only 2K, or they might not permit a wide range of frame rates, or they offered less brilliant illumination.

Another answer to a saturated market was continuous research and development. No sooner had exhibitors installed the “Series 2” projectors introduced in late 2009-early 2010 than speculation began about enhancements. How soon, for instance, might we expect 6K or even 8K resolution? Two other innovations were responding to problems with the dimness of digital 3D images.

One possibility was laser projection, which would be expected to brighten the image considerably. Laser projectors may start appearing in Imax cinemas later this year, but for most venues the current costs are prohibitive, running about half a million dollars per installation.

3D light levels could also be boosted by shooting and showing at higher frame rates than the standard 24. Peter Jackson famously experimented with 48-frame production on The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, and some theatres screened it that way. Response was mostly skeptical, with critics complaining of the hypersharp, “soap-opera” effect onscreen. The frame-rate issue has mostly quieted down, but it did trigger academic studies of the perceptual psychology involved in frame rates. In addition, James Cameron has insisted that his sequels to Avatar will be shot at an even higher frame rate. Most projectors require new software in order to increase frame rates.

Alongside developments in the projection market have come new devices for sound. As Jeff Smith pointed out in an earlier entry, innovative sound systems have been enabled by the switchover to digital presentation. 35mm film stock constrained the amount of physical space on the film strip that auditory information could occupy. Now that sound is a matter of digital files, sound designers can add many tracks for greater immersive effects—so-called “3D audio” platforms. Barco’s Auro 11.1 system and Dolby Atmos position several more speakers around the auditorium, including ones high above the audience. Costs of installation for these systems run from $40,000 to $90,000.

Still, projector and sound-system manufacturers can assume that business will continue because of the pressures for change inherent in digital technology. Experienced equipment installers suggest that a digital projector’s life is between five and ten years. Already the Series 1 projectors introduced in 2005 are becoming obsolete. Chapin Cutler, of Boston Light & Sound, notes:

A digital projector is a computer that puts out light. How many computers will you go through in the next ten years?

How many Series 1 projectors are still in use and supported by the manufacturers? Try buying parts for them. I know of one that was purchased four years ago that has been pushed into a corner. It has sat there for about two months so far, with no end in sight. (Thank heavens they still have their 35 mm gear!) It is broken and the manufacturer cannot supply parts; their customer service department doesn’t know about the machines, as they have only had to deal with the newer models; and the parts are not listed in their own internal parts book. Yes, four years old.

When replacement parts are available, they can be exceptionally pricey. A projector’s light engine, central to the image display, can run $22,000. And if an exhibitor buys a brand-new projector some years from now, the studios aren’t likely to launch a new round of VPF financing.

So even if a theatre can afford the expense of conversion today, upgrades and maintenance will demand big commitments of money in the years ahead. John Vanco, Senior VP and manager of New York City’s IFC Center, has put it well:

Many, many small, independent theatres, which are vital to the survival of non-studio films, will end up being fatally hobbled by the transition. They may be able to raise funds to cover the initial conversion, but what will crush many of them in the long term is the ongoing capital resources that will be necessary to continue to have DCI-compliant equipment in the next ten and twenty years. . . .

In the same way the current inexorable pattern of planned obsolescence forces consumers to continually repurchase computers, phones, etc., cinemas too are going to find that they have to spend much more for cinema equipment over the next twenty years than they did, say, from 1980 to 2000. . . . So these technological progressions will make it harder for those small theatres to survive.

Dylan Skolnick of Huntington, New York’s Cinema Arts Centre adds to Vanco’s point. “We have great supporters, but I can’t go back to them every five-to-ten years with a ‘Digital Upgrade or Die’ campaign.”

The problem is acute for small and art-house venues, but it isn’t minor for the Big Three either. Unless film attendance jumps spectacularly (it has been more or less flat for several years), exhibitors may need to raise ticket prices and the costs of concessions. This strategy may work in urban areas but won’t be popular elsewhere. Moreover, part of the boom in box-office revenues during recent years has been due to the upcharge for 3D features. But in the US, 3D revenues are currently leveling off at about $1.8 billion, a drop from the format’s 2010 peak of $2.14 billion. In 2012, 3D’s market share slipped as well. It isn’t clear that people would flock to 3D if the images were brighter. And if 3D television takes off, stereoscopic cinema will seem less compelling as a novelty.

Some observers hold out hope for glasses-free 3D technology in theatres, a change that would probably boost business. But the difficulties of creating 3D of this sort for multiplex venues are immense. The glasses-free platforms proposed by Dolby are aimed at small displays, like TVs, smartphones, and tablets. Of course, if 3D without glasses were devised for big screens, it would almost certainly demand yet another projector redesign.

No more silver bricks

When it comes to distribution, digital isn’t there yet. The UPS and Fed Ex corps still bring movies to multiplexes the old-fashioned way. The little briefcases are a lot lighter than hulking metal shipping cases, but we’re still dealing with physical artifacts.

At least for the moment. Festival submissions are already being placed in Cloud-based lockers like Withoutabox in an effort to replace DVD screeners. Online delivery is already being used for many of those operas, ballets, and other forms of “alternative content” flowing onto screens from various suppliers. A Norwegian distributor sent a 100 gigabyte local film, fully encrypted, to forty cinemas in the spring of 2012. This and experiments in other countries employ fiber-based networks, but the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a joint venture among Hollywood studios and the Big Three exhibition chains, is exploring satellite systems.

So much for the impassive silver bricks in their cute pink beds on the cover of Pandora’s Digital Box. They may become as quaint as film reels and changeover cue-marks. For a time, the hard drives may survive as backup systems that will reassure exhibitors, but eventually no physical site may serve as the movie’s home. An exhibitor will download the film to the server, apply a decryption key sensitive to time, venue, and machine, and the movie will be, as they say, “ingested.”

In the Pandora book, I included chapters on other exhibition domains I haven’t revisited here. Take archives. More and more studios refuse to rent prints, will not prepare DCPs of most classic titles, and won’t let theatres screen Blu-ray discs commercially. So repertory cinemas turn to archives, seeking to rent 35mm copies that may be irreplaceable. In addition, archivists, laboring under tight budget constraints, are racing to preserve and restore their material on film, which remains the most stable support medium. At the same time, archives are expected to get involved in preparing high-quality digital versions of popular classics. Henceforth most restorations that you see will be circulated on 2K or 4K, as Metropolis, La Grande Illusion, and Les Enfants du Paradis have been in recent years.

Film festivals, as Mike King, one of our Wisconsin Film Festival programmers observes, are now file festivals. Cameron Bailey reported that of the 362 titles screened at TIFF last year, only fifty-one were on film. Last month, our annual event ran twenty-one new films on film; most were 16mm experimental items. The remaining 132 were on DCP, HDCam, Quicktime files, or DVD/Blu-ray. On the plus side, independent filmmakers are learning to encode their films in the DCI-compliant format, often without layers of security, so at least in this respect technology may not be a severe barrier to entry.

As for me, I’m still in the midst of churn. I watch movies on film, on DCP, on DVD and Blu-ray and VOD, even on laserdisc, and sometimes on my iPad. But my research will miss 16mm and 35mm. Some of the questions I like to ask can be answered only by handling film. Last weekend I sat down at a Steenbeck flatbed and counted frames in passages of Notorious and King Hu’s Dragon Inn. This sort of scrutiny is virtually impossible on DVDs and Blu-rays, which don’t preserve original film frames.

What I’ve lost as a specialist is offset by many gains. Since the arrival of Betamax and VHS, nontheatrical cinema has expanded to limits we couldn’t have imagined in the 1970s. Thanks to consumer digital formats, more people have more access to more movies of all sorts than at any point in history. Although some aspects of film-originated movies are hard to recover on digital playback, we can study cinema craft to an extent that wasn’t possible before. Digitization has allowed sophisticated visual and sonic analysis to bloom on websites around the world. See, among many examples, Jim Emerson’s Scanners and A. D. Jameson’s work on Big Other.

With the rise of nontheatrical consumption, though, what’s most at risk is theatrical cinema: film viewing as a public forum. Exhibition outside film festivals is already starting to narrow to recent releases and a few approved classics. We will be able to watch The Suspended Step of the Stork and Leviathan on our home screens for a long time to come, but very seldom on the scale that benefits them most.

As ever, the problem of technology isn’t only a matter of hardware. Technology develops within institutions. Hollywood has standardized a new technology favoring its goals. The institutions of minority film culture–festivals, art houses, archives, local cinemas, schools–need to be robust and resourceful to maintain all the types of cinema we have known, and the types we might yet discover.

Since Pandora was published, a very comprehensive guide to the mechanics of digital projection has appeared: Torkell Saætervadet’s FIAF Digital Projection Guide, and it’s a must. One rich treatise I didn’t cite in Pandora is Hans Keining’s 2008 report 4K+ Systems: Theory Basics for Motion Picture Imaging. Michael Karagosian’s website is an excellent general source on digital exhibition in the late 2000s.

Screen Daily provides a good overview of the new technology on display at CinemaCon 2013. For general background on industry trends after the changeover, see the Variety article “Filmmakers Lament Extinction of Film Prints.” As for archives, Nicola Mazzanti edited a very useful European Commission study, Challenges of the Digital Era for Film Heritage Institutions (Berlin/ UK, 2012). May Haduong surveys current problems of print access and film archives in “Out of Print: The Changing Landscape of Print Accessibility for Repertory Programming,” The Moving Image (Fall 2012), 148-161. The piece requires online library access, but a summary is here.

Much of the industry information in this entry came from proprietary reports published in IHS Screen Digest. Thanks to David Hancock for his assistance with other data, and to Patrick Corcoran of NATO for updated information on theatre conversion. Thanks as well to Chapin Cutler, Duke Goetz, Michelle Haugerud, and Dylan Skolnick for permission to quote them. I’m also grateful to Jack Foley of Focus Features and Joshua Hittesdorf of Market Square Cinemas. Finally, I want to thank Russ Collins and his colleagues at the Art House Convergence for mounting another splendid event and for inviting me back last January. I continue to learn from the discussions on the AHC listserv, and I’m particularly grateful to John Toner for his reports on independent cinemas’ funding efforts.

Other entries on this site offer material on the digital transition. There’s “It’s good to be the King of the World,” on James Cameron’s push for 3D TV; “ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming,” about the powers of photochemical cinema on display at the Toronto International Film Festival 2012; “Digital projection, there and here,” some notes on the situation in Western Europe; and “Side by side: Quick catchups,” includes notes on sources for studying digital cinema. In “16, still super,” veteran programmers talk about how they continue to rely on this format; in the process they convey their commitment to providing unusual fare.

P. S. 15 May 2013: Rebecca Hall of the extraordinary Northwest Chicago Film Society has posted a continually updated list of theatres that are dedicated to showing films in 16mm and 35mm.

P.P.S. 12 June: David Hancock has just presented a very full report entitled “Digital Cinema Worldwide: 35mm phased out in many countries, though some lag behind.” It is published in the June IHS Screen Digest. One of my remarks above has been corrected in light of some information in the report: I claimed that Belgium has fully converted, but David’s figures indicate 96.5% conversion.

David predicts that by end 2013, 90 % of world screens will be digital. Even India is making the move, as circuits relying on DVD or other low-resolution sources are converting to DCI-compatible equipment. Those regions slowest to convert include Italy, Greece, and Spain (not surprisingly, given recent austerity policies), as well as areas of South America and the Pacific (e.g., Thailand, the Philippines). Thanks to David and his team at IHS Screen Digest for their comprehensive coverage of this process.

Dragon Inn (King Hu, 1967). 35mm frame enlargement, taken on Fujichrome 64.

Atmos, all around: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Today we have a guest entry by our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. Jeff teaches here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the Film Studies area. He’s an expert on cinema sound, particularly music. His book The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music is a trailblazing explanation of the ties between 1960s Hollywood and the music industry. It combines analysis of scoring with discussions of business decisions that shaped audience’s response to movie soundtracks. His forthcoming book is on how critics have understood the impact of the HUAC hearings and the Hollywood Blacklist, with emphasis on films that seem to comment on Cold War politics.

Jeff has written extensively on sound practices in contemporary American cinema. What better person to explain and analyze the newest sound technology in Hollywood movies?

Director Peter Jackson calls it “the completely immersive sound experience that filmmakers like myself have long dreamed about.” Mark Andrews, who made his feature film directorial debut with Pixar’s Brave, says, “It’s more 3D than 3D images.” “It” is Dolby Atmos, a new cinema sound system that promises to change the way you see and hear movies. Does it?

The buzz

Dolby Atmos made its debut with Brave at last year’s Los Angeles Film Festival. A handful of scenes from earlier films, including Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Incredibles had been test-mixed in the new Atmos system for demonstration purposes. But Brave is the first film to use the new platform from start to finish.

If you haven’t heard of Dolby Atmos, you’re not alone. When Brave opened, there were only fourteen theatres in the country that were capable of showing the film in Atmos. These tended to be high-end movie theatres, such as AMC’s six Enhanced Theatre Experience venues, which typically charge a premium ticket price.

The list of theatres wired for Atmos has grown since then, but the number remains quite small. At this point, there are 37 theatres in the U.S. that feature Dolby Atmos, a tiny fraction of the country’s nearly 40,000 screens. A little more than a third of these theatres are located in California. Approximately another third are clustered in just five states: Florida, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington. Most of these theatres are in the suburbs of major metropolitan areas. True, the recently opened Palms Theatre in Muscatine, Iowa (population 22,886) incorporated an Atmos system in its XL Digital Auditorium, but presumably it was part of its building plan. For existing theatres, an upgrade carries a hefty price tag of between $30,000 and $100,000. So Dolby Atmos may not be coming soon to a theatre near you.

Yet more and more films are being mixed for Atmos. Dolby has announced that more than twenty films will feature the new platform in 2013, a significant increase over the twelve films distributed with this format in 2012. The roster includes three of the most eagerly anticipated studio tentpoles of the summer season: Paramount’s Star Trek Into Darkness, Pixar’s Monsters University, and Warner Bros. Superman reboot, Man of Steel. Still, does the new system justify the expensive theatre conversions and the higher ticket prices that will follow?

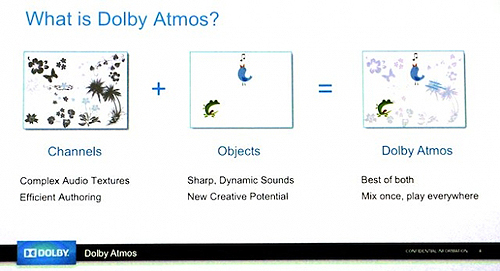

Two channels. Then five + one. Now, how about sixty?

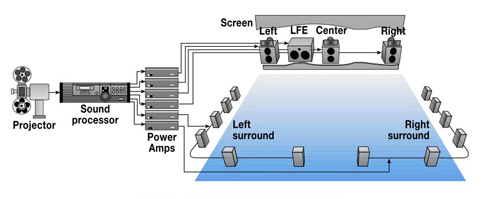

Dolby Digital Surround 5.1.

According to the Dolby website, Atmos grew out of the company’s efforts to introduce Dolby 7.1. For years, the flagship for Dolby’s digital surround sound technology was their 5.1 system. The digit 5 referred to the number of channels that could be used by sound mixers: three channels for speakers behind the screen (left, center, and right) and two channels for all the surround speakers that line the side and back walls of the auditorium (left surround and right surround). The .1 in 5.1 refers to the Low Frequency Effects channel (LFE) that sent sounds between 3 to 120 Hz to a subwoofer located behind the screen in the front of the auditorium. These low-frequency sounds trigger acoustic vibrations that add a kinesthetic kick to onscreen explosions and car crashes.

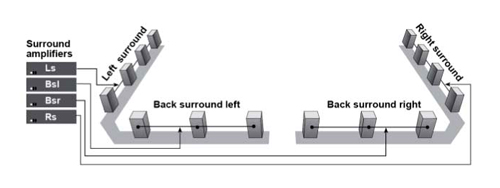

With Toy Story 3 in 2010, Dolby introduced two additional channels to their 5.1 platform. The 7.1 system subdivides the surround speakers. Instead of two channels for the surrounds (left surround and right surround), Dolby 7.1 offers sound mixers four channels (left side surround, left rear surround, right side surround, and right rear surround).

Dolby 7.1 came fairly late to the game, however. Sony already had introduced its own 7.1 system in 1993 with the premiere of John McTiernan’s Last Action Hero. Yet despite the eight-channel capability of Sony Dynamic Digital Sound, (SDDS), it never really caught on, largely because of the added expense of executing a 7.1 sound mix in addition to the standard 5.1 one. To date, more than 1400 films were mixed for the six-channel version of SDDS. Only 97 films received an eight-channel mix.

In the 2000s, Sony gradually began to phase out its 7.1 system. Filmmakers stopped building eight-channel mixes in SDDS in 2007. Moreover, about ten years after introducing SDDS, Sony stopped manufacturing decoders for SDDS content, citing decreased demand. SDDS had always lagged behind its competitors in the battle for screens, so Sony’s decision was not terribly surprising. Although new films continue to be mixed in SDDS to meet the needs of exhibitors that continue to use the system. Most theatre owners have replaced SDDS with one of Dolby’s systems. Sony promised exhibitors it would continue to make parts and service for current SDDS products available until 2014. But the electronics giant acknowledged that it was shifting its attention to digital cinema technologies that were already in development.

Considering Sony’s history and exhibitors’ reluctance to upgrade to an eight-channel system, it’s surprising that in 2010, Dolby would launch its own 7.1 counterpart. But maybe not so surprising, because Dolby’s new channels were differently placed. Sony’s 7.1 system had added channels to the speakers behind the screen. Instead of three front channels (left, center, and right), SDDS had five (left, left center, center, right center, and right). These extra sound sources probably made little difference to most moviegoers. Adding channels behind the screen made for smoother panning of sounds that seem to move across the space depicted in a shot, but it did nothing to increase the sense of spatial immersion.

In contrast, Dolby added its two extra channels to the surround areas. Its 7.1 platform treats the interior of the theatre as seven spatially distinct zones. The additional channels in the surround array enables mixers to position sound elements more precisely. This “zoning” of the surrounds offers mixers a wider variety of options for the placement of sounds, and it more closely approximates the way that sounds in real life come at us from several different directions.

Now Dolby Atmos pushes the premises of this aspect of Dolby 7.1 to the nth degree. While Dolby 7.1 makes a leap from six channels to eight channels, Dolby Atmos makes a leap from eight channels to sixty-four channels, a gigantic change from all of Atmos’ predecessors. Using the old nomenclature that described the sound platform as a ratio of speaker channels to LFE channels, we might call Dolby Atmos a 62.2 system! It offers more than sixty separate and distinct speaker channels as well as an optional channel for additional subwoofers located in the back corners of the auditorium. More importantly, with the vastly expanded number of speaker channels, Atmos enables mixers to position a single sound element in the theatre with unprecedented clarity and precision.

Say you have a screen door banging in the wind. In Dolby 5.1, if a mixer wanted to send that banging noise to the right surrounds, it went to every speaker in the array. In effect, it wouldn’t sound like a single door, but rather several doors banging in unison. In Atmos, however, if a mixer wants to position that banging sound in a particular part of the auditorium, he can treat it in a manner analogous to the way it would be heard in the real world. The sound is emitted from a single point of origin and is heard as a punctual effect rather than as aural ambience emanating from a broader area of the theatre.

All about the panning

Beyond its multiplication of channels, Dolby Atmos addresses certain limitations in earlier platforms. Simplifying a bit, we can say that for content providers Atmos is “all about the panning.” Atmos adds a couple of speakers on each side that are placed close to the screen to facilitate smoother pans for sounds that move from onscreen to offscreen.

The surround speakers in Atmos have a frequency range that closely matches that of the speakers behind the screen. This aspect of Atmos addresses a common complaint about more traditional digital surround systems. In those, the surround speakers have a narrower frequency range than the front ones. As a result, when sounds were panned from onscreen to offscreen, the audience could hear changes in timbre and fidelity. The extra subwoofers in Atmos ameliorate this problem since they help to “bass manage” the surrounds, thereby allowing sounds in them to have a much “fatter” low end.

Besides adding subwoofers to increase the number of LFE channels, theatre owners have the option of adding left center and right center channels to the speakers behind the screen. This allows for smoother pans of sounds made by characters or objects that move across the screen. In this respect, Atmos combines the best features of Dolby 7.1 and Sony’s eight-channel system.

Up in the air

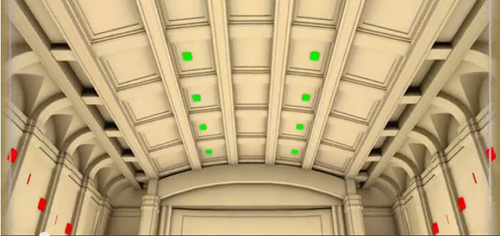

In platforms like Dolby 5.1, sound is situated almost entirely on one plane. The speakers behind the screen are at roughly the same height as are the surround speakers that line the sides and back wall of the auditorium. Dolby Atmos expands the auditory field by adding speakers to the theatre’s ceiling.

These additional speakers create an overhead sound plane, which enhances the sound mixer’s ability to localize sounds in the auditorium. In real life, of course, we hear all kinds of things overhead–bird calls, airplanes, building construction. Although mixers can use these ceiling speakers for sounds that are important in the story that unfolds onscreen, Dolby’s literature usefully reminds us that overhead ambient sound can enrich a film’s setting. A chirping cricket placed in one of the overhead speakers can convey the feeling of sitting at night beneath a forest canopy.

Admittedly, this new feature of Atmos technology merely represents a refinement of something filmmakers could do before. But previous sound technologies suggested an overhead sound plane through a psychological illusion. When the characters in Das Boot, for example, hear the pinging sounds of a British destroyer’s sonar system above their submarine, we might hear that sound originating above our heads. Yet its point of origin is no different from any other sounds that we hear in Das Boot.

Characters’ upturned gazes bias our response as we watch them anxiously awaiting the detonations of the depth charges released by the destroyer.

The extra surround channels and the overhead sources all create a more enveloping ambience and more punctual sound events—ultimately, a more realistic aural environment. Dolby’s innovations should be especially appealing for films projected in 3-D. Atmos, as its proponents note, offers a 3-D sound to match 3-D picture.

Is the recent popularity of 3-D cinema, though, the only factor in Dolby’s push to get more exhibitors on board with Atmos? Curiously, it comes right on the heels of Dolby’s introduction of its 7.1 system. Over the years, Dolby has continually pressed its R & D division to develop new sound technologies. But, in bringing both Dolby 7.1 and Atmos to the marketplace in about a two-year time span, I still have to wonder, “Why now?”

Backward compatibility

Fans of Atmos argue that it represents nothing less than a paradigm shift for cinema sound technology. That may prove to be true if more exhibitors decide to invest in it. But if we are witnessing a paradigm shift, it is one made possible by another paradigm shift, one of even greater historical import. I’m thinking here of the sweeping change that took place as theatres changed to digital projection.

David has written extensively on this topic, and you can find his account of this change in his e-book, Pandora’s Digital Box, a recasting of several blog entries under that name. Actually, the shift to digital projection didn’t demand Atmos. But it certainly made it possible.

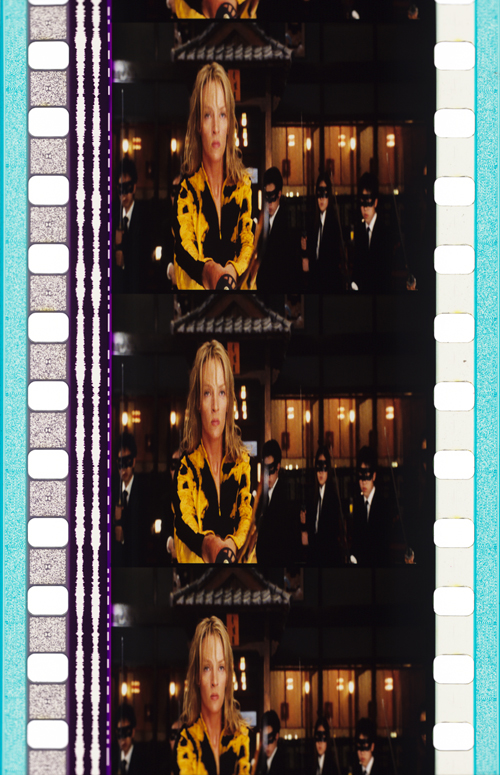

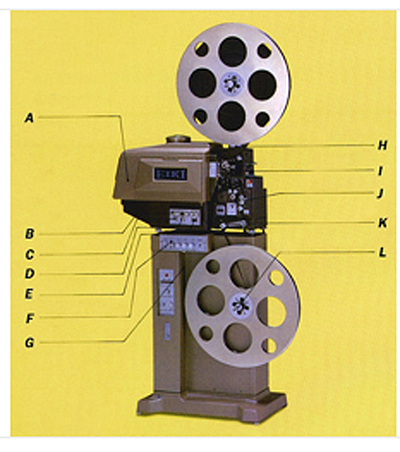

Look closely at a single frame of 35mm film. Like an archeological record, it preserves thirty-plus years of cinema sound innovation. Left of the picture area, you can see the twin optical sound stripes, encoded as wavy lines, that are used for older Dolby Stereo systems. Dolby continually refined its initial four-channel stereo system, ultimately introducing Dolby SR in 1986 as the last generation of its signature noise-reduction technology. (The SR stands for Spectral Recording.) These optical stripes on a 35mm print are still necessary for any theatre still using analog sound.

Just to the right of these optical stripes you can see dashed white lines used for DTS time code. DTS is a digital surround sound technology that uses compact discs to store and play back the film’s audio. The white lines maintain sync between picture and sound.

On the extreme left and right edges of the film strip, outside the perforations, is a speckled light blue stripe. That encodes the audio data for SDDS playback. The information in the two stripes is redundant, but that’s necessary because SDDS is decoded by a sound reader that mounts on the top of a 35mm projector. By putting the information on both sides of the frame, Sony’s design avoids any potential problems in threading the SDDS decoder.

Lastly, in between the sprocket holes on the left side, you can see the audio information for Dolby Digital. Like the SDDS stripes, these gray patches of Dolby Digital audio are encoded as data blocks that are read by a digital sound head. They send the information to a Dolby Cinema Sound Processor.

In our 35mm strip, a huge amount of audio information, along with the film image itself, is jammed into a space that’s less than an inch and a half wide. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, this “quad track” – that is, one analog system and three digital formats – proved to be very versatile. The audio could be played back in any theatre, regardless of the particular type of sound system that is used. The quad track allowed studios to avoid the distribution nightmare of having to match prints to screens using different audio systems. The one-size-fits-all approach also enabled multiplex exhibitors to move a print from one screen to another without worrying about compatibility.

But suppose we had to add another type of audio data to 35mm film, one that is capable of supporting more than sixty different audio channels. There just isn’t enough empty space on a 35mm print to make such an innovation possible. So even if Dolby’s engineers envisioned the potentiality of an overhead sound plane and of a cinema sound processor capable of supporting 64 different outputs, there was no practical way to add the audio information needed for Dolby Atmos and retain the compatibility offered by the quad-track 35mm.

Enter the Digital Cinema Package. With the large-scale conversion to digital projection, the prospect of innovating a system like Dolby Atmos suddenly took on new life. The audio files for Dolby Atmos are embedded in the DCP alongside the files for 5.1 and 7.1. Like the audio in 35mm film, the DCP is designed for maximum compatibility. The Dolby Atmos files are ingested into the theatre’s server along with all of the other audio and picture files found in a DCP. But for any theatre that is not wired for Atmos, the server simply ignores the Atmos files and uses the main audio track file for standard playback. More importantly, if there is any communication problem between the server and the Atmos sound processor, the system simply reverts to a Dolby Surround 7.1 or 5.1 mix, ensuring that a show can continue without delay. Even more impressively, the Atmos system even detects a damaged speaker or amplifier. Its flexible rendering system automatically works around the faulty component, sending the necessary audio data to other parts of the replay chain. So a show will continue despite a technical problem, and a narratively important sound effect or line of dialogue will not be lost due to a damaged speaker or amplifier.

The backward compatibility found in the Atmos system has long been an aspect of Dolby’s business strategy. When Dolby introduced its four-channel Stereo technology in 1975, it did so in a way that accommodated the needs of theatre owners who wanted to retain their existing sound systems. Dolby Stereo used a matrix system that mixed four channels of audio information down to the binaural optical stripes found on a standard 35mm print. After the projector’s sound head read these optical soundtracks, the information contained in them was then sent to a sound processor that “unpacked” the binaural stereo and sent the signals to the appropriate speakers in the auditorium. Dolby’s matrixing system, though, was prone to certain amount of cross-talk between the screen channels, and it occasionally caused a sound to be sent to the wrong output in the four-channel mix.

As a company concerned about backward compatibility, Dolby was willing to live with trade-offs. On one hand, the Dolby matrixing system avoided the kinds of format complications found in multi-channel systems that used magnetic striping. On the other hand, because of the potential for bleed between channels, some sound editors were reluctant to experiment with directional sounds in Dolby Stereo mixes. In practice, the surround channel in Dolby Stereo was reserved mostly for ambient noise, things that added texture to a film’s aural environment but that did not flaunt the precise directionality made possible by multi-channel playback.

Sound historians Jay Beck and Mark Kerins point out that such timidity has also characterized a good deal of sound work in the Digital Surround era. Contemporary sound designers strive to create immersive audio environments for films, but they also opt not to localize specific sounds that would draw our eyes away from the screen. In particular, designers shy away from assigning sudden loud sounds to the rear surround channels. Because the sound originates behind the audience, viewers are likely to be startled, which can be inappropriate to the mood of the story. Worse, the audience may turn to see what caused the unexpected noise. This is called the “exit-door” effect, because it pulls the viewer out of the story as if somebody had slammed the emergency exit.

Sound editors are much bolder about localizing individuated or punctual sounds in an Atmos mix. With 64 different channels to play with, Atmos offers myriad possibilities for audio experimentation. For content-providers, Atmos presents a “brave new world” for cinema sound. But this leads to a larger question: What is it like to see a film in Atmos?

Multi-channel sound with a Scottish lilt

While I was in Los Angeles last August doing research, I decided to spend a sunny Sunday morning at the movies. The City of Angels has a bevy of terrific movie theatres showing Hollywood’s latest, but the choice was easy. I headed to see Pixar’s Brave at Hollywood’s El Capitan Theatre, then one of only ten theatres in the country wired for Dolby Atmos.

El Capitan opened in 1926 as one of three theatres run by legendary showman Sid Grauman. Unlike Grauman’s nearby Egyptian and the famous Chinese Theatre, El Capitan was a venue for live performances. After a decline in attendance in the late 1930s, El Capitan was refurbished and reopened as the Hollywood Paramount Theatre. For several years, it remained a flagship for Paramount Pictures until the late 1940s, when the U.S. Supreme Court and the Justice Department forced all of the studios to divest their exhibition holdings. Until 1991, El Capitan was owned and managed by a series of different companies, including the Pacific Theatres Circuit.

That all changed in the late eighties when Disney offered to lease El Capitan from Pacific Theatres with an eye toward using it as a venue for premiering new films. Disney spent millions restoring the theatre’s original décor, although it seems to have been “imagineered” into a faux 1920s picture palace, complete with a Mighty Wurlitzer organ. Disney also restored El Capitan’s original name perhaps in an effort to sever the theatre from its earlier associations with Paramount. El Capitan is now Disney’s own flagship theatre in Hollywood and is fully integrated with their other businesses. Indeed, the Sunday morning that I attended Brave I was surrounded by families visiting it as one of the stops in Disney tour packages.

As a premium venue, El Capitan offers much more than your usual movie experience. As I walked in to find a seat, a talented organist played a medley of songs from classic Disney films, like Pinocchio’s “When You Wish Upon a Star,” and from more recent titles, such as Toy Story’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” and The Lion King’s “Circle of Life.”

There was plenty of other pre-show entertainment.: a couple of trailers, a brief light show, and song and dance numbers featuring costumed Disney characters. Unlike the organ medley, though, these live performances did not use music from Disney films, but instead drew from the Great American songbook. Mickey and Minnie danced to Astaire-Rogers tunes, followed by patriotic songs, including George M. Cohan’s “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and “The Yankee Doodle Boy.” The program culminated with a short medley of Scottish songs that introduced Disney’s newest princess, Merida.

This final number provided a more or less seamless segue into the start of Brave.

I didn’t know quite what to expect from the film, which has hailed as a change of pace for Pixar, a company that had developed a reputation for targeting a “family film” demographic centered on pre-teen boys. Despite the fact that Pixar had broken new ground with the film’s red-haired, tartan-clad heroine, Brave received middling reviews. By August, it was perceived as a bit of an underperformer, having earned “only” half a billion dollars worldwide. (Such is the high bar set by Pixar titles.)

I quite enjoyed Brave, not least because it was in Atmos. For the most part, Atmos lived up to the hype, offering a sonic experience that was unlike anything I’d heard in theatres before. In a way, Atmos simply refines things that could be accomplished in Dolby 5.1 or 7.1. Yet certain moments of Brave lived up to the promise of a fully three-dimensional sound that matches a film’s 3-D images. I’m not an audio engineer or sound technician. I’m really just a guy who likes going to the movies, albeit one who is a tad more attuned to the vagaries of digital surround sound mixes. So I’m offering some “in the moment” impressions of the Atmos system. If I’ve made any grievous errors in description, chalk it up to either faulty memory or the power of cognitive illusion.

I first became aware of Atmos as something different early on during a rather ordinary scene in which Merida receives “princess training” from her mother. As Merida recites a poem, the Queen, standing above her, instructs her to project her voice saying, “Enunciate! You must be understood from anywhere in the room or it’s all for naught.”

Cut to Merida. When she replies under her breath, “This is all for naught,” the Queen shoots back “I heard that!”

During this brief shot that holds on Merida, Emma Thompson’s mellifluous response as the Queen issues from one of the left rear surround speakers.

The localization of the Queen’s voice creates a brief “point of audition effect” as it realistically places us in the middle of the diagonal space that separates Merida from her mother. The moment also playfully demonstrates the Queen’s instruction to Merida to be heard from “anywhere in the room.”

Another example of Atmos’ innovative use of offscreen sound occurs during the family dinner scene in which Fergus is retelling the story of his confrontation with Mordu. After Merida sits down at the table, Fergus is about to take a bite from a leg of poultry. At this moment, we hear the sound of barking dogs swiftly panned through the right side surround speakers in the auditorium.

The dogs then burst into the frame from off right.

The use of spot sound effects in the surround speakers is quite conventional, but the panned barking had a smoothness and swiftness that I had not heard before.

This moment is interesting for another reason. Although this is admittedly a bit speculative, I believe it showcases Atmos’ ability to exploit a kind of aural correlate of the Phi Phenomenon. The Phi Phenomenon refers to an optical illusion involving the movement of light. Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer noticed in experiments conducted in the early 1910s that when two lights were flashed on and off rapidly enough, subjects saw them not as two flashing lights, but rather as a single light that appeared to move back and forth. Many neon signs exploit this perceptual illusion.

The same is true of this rapidly panned sound in Dolby’s Atmos, which is made possible by the system’s “pan-through array.” Because the sound editor can use positional metadata to send the sound of the bark to each of the right side surround speakers for just a couple milliseconds of time, our mind does not hear it as a group of fragmented sounds, but instead hears it as a single sound that zips through the space of the auditorium.

Later, while galloping in the woods, Merida finds herself thrown into the middle of a Stonehenge-like circle. As Merida gets her bearings, we hear a breathy, echoey, high-pitched sound coming from one of the right surround speakers. Cueing us by Merida’s glance into the space off right, director Mark Andrews cuts to a shot over Merida’s shoulder that shows a blue wisp off in the distance.

The use of a sound effect in the surround channels to steer our attention to offscreen space may be one of the most conventional aspects of digital sound aesthetics. Yet this moment is a bit unusual. It positions one localized sound effect against a bed of ambient sounds that are sent to all of the speakers in a geographical zone. In fact, this is an aspect of Atmos that Dolby showcases to content-providers. Unlike systems that are wholly channel-based, Atmos allows sound editors to locate a single sound effect in an individual speaker at the same time that other groups of sounds are fed to the system as a channel-based submix. The combination of “beds” and aural objects is captured in a visual diagram provided by Dolby.

The graphic of the bed shows a variety of gray-colored flora and fauna. The aural objects are represented as a green frog and a blue songbird. When the two images are combined, the green frog and blue bird stand out as individually colored objects set off against the bed of gray background elements. Background and foreground effects can all be developed individually and then blended at a later stage of postproduction. Atmos refines the creative possibilities found in other digital surround sound systems in a way that preserves current workflows.

Up until now, I have not said much about Atmos’ ability to exploit an overhead plane of sound. This may strike you as a bit curious since the legendary sound designer, Gary Rydstrom, discussed this aspect of Atmos in the Hollywood Reporter as one of the technology’s most appealing features. Describing a scene where Merida goes to retrieve an arrow that she has launched, Rydstrom says:

You hear the arrow ‘swish’ go through the theatre and land way back behind the audience. Then she goes into the forest. I love putting sound in the ceiling, things like scary forest birds. For a little girl, the forest feels even taller and more imposing if you can have weird sounds way up high.

Rydstrom’s description beautifully captures the way this moment from Brave works onscreen. Yet because I had read his comments before seeing the film, it was a little less powerful than some other events on the overhead sound plane. A moment I found more striking comes when the queen realizes that a magic spell has turned her into a bear. The bear flails about the room, ultimately falling backward onto her four-poster bed.

After falling through the bottom of the bed, the bear then bolts upright to smash through the canopy. Aurally, this moment is rendered as a loud crash located in the speakers suspended from the ceiling. The placement of the sound beautifully punctuates the bear’s sudden upward thrust, adding a sonic punch to the sight gag.

Probably the most vivid demonstration of Atmos’ capability comes in a scene in which Merida is caught in a thunderstorm. Sitting in the balcony of El Capitan, I felt pulled into the thick of events unfolding onscreen. If you shut your eyes, you could almost feel the patter of raindrops, the whoosh of the wind, and the violent clamor of thunderclaps.

Admittedly, such scenes can seem pretty powerful in a theatre using a more conventional digital surround system. A Dolby 5.1 or 7.1 mix can create comparable aural immersion by simply sending submixes of the storm’s sounds to different zones within the theatre. I suspect that the impact of the Atmos mix came less from its ability to isolate particular sound effects than it did from the additional subwoofers placed in the back corners of the theatre. With three subwoofers, loud sounds seem flung at you from all directions. Thanks to the additional LFE channel, the sound waves from those thunderclaps triggered even stronger shakes and rumbles. (The extra subwoofers also enhanced Mordu’s ferocious roars during the epic confrontation, shown up top, that resolves Brave’s plot.) The overhead speakers also played a subtle role in creating the feeling of being caught in a storm. The sense of a three-dimensional environment is undoubtedly heightened by the sound of rain droplets falling and spattering above one’s head.

Is Dolby Atmos the great leap forward for cinema audio that its proponents claim? The answer depends upon the weight you place on potentiality vs. established practice. Atmos definitely creates opportunities for precise placement of sounds in the auditorium. That in turn offers new prospects for audio/visual coherence. As Dolby puts it in the white paper: “If a character on the screen looks inside the room toward a sound source, the mixer has the ability to precisely position the sound so that it matches the character’s line of sight, and the effect will be consistent throughout the audience.”

Yet the specific purposes to which Atmos was put in Brave – the use of spot sounds to activate offscreen space; the use of surround speakers for panned or moving sounds; the creation of a immersive, 3D aural environment; the use of loud noises to viscerally impact the audience – are all things that its predecessors accomplished, going all the way back to Dolby’s pioneering four-channel system. Atmos does these things either a little better or a lot better, depending upon the specific system you’re comparing it with.

Perhaps my description of Brave suggests that the advantages of Atmos are more subtle than spectacular. Perhaps you feel that contemporary movies are sound-polished enough already. If so, Atmos probably won’t hold much appeal for you as a moviegoer.

The bigger question for me is whether it will be widely adopted by theatre owners. A key aspect of Dolby’s sales pitch for Atmos is that it is scalable to almost any size of theatre. If your theatre is too small for a 62.2 configuration, you can reduce the speaker array and get some of the benefits of Atmos’ improved surround definition and overhead sound plane. Dolby says its minimum configuration for Atmos is 9.1. But if the best that you can do for your theatre is 9.1, then perhaps Dolby’s 7.1 system is a more sensible option.

The exhibitor’s ability to mix and match components in Atmos was something I experienced firsthand during a recent visit to the ShowPlace ICON in Chicago. The ICON has two screens wired for Atmos, but those auditoriums weren’t equipped with the optional subwoofers that were in the system at El Capitan. Why? With two additional subwoofers, there is increased risk of sound bleeding over to the neighboring auditoriums of a multiplex. This wasn’t a problem for El Capitan, a huge, standalone theatre.

In any case, the costs to upgrade all the screens in a multiplex would be prohibitive, particularly at a time when many theatre owners are still smarting from expenditures of converting to digital projection. For that reason, Atmos may be introduced as 3D was, with one or two screens per venue at first. The decision to do an Atmos upgrade may devolve upon the question of what particular sound system is good enough to meet the needs of both theatre owners and patrons.

Yet the threshold for “good enough” is not static, and theatre owners may find themselves under increasing pressure as home theatre technologies become ever more sophisticated. If Quentin Tarantino is right that watching digital projection in a movie theatre is like watching a giant television screen in someone’s living room, then Atmos really offers exhibitors something to differentiate the multiplex from the home theatre. With 4K televisions already showing up at big-box retailers, cinema audio may provide exhibitors with the best means of luring movie fans out of their living rooms. After all, are you really ready to deploy a couple of dozen speakers around your walls and from your ceiling?

At several points in this post, I cited information made available in a white paper prepared by Dolby that explains the key features of Atmos to content providers and exhibitors. Additionally, Dolby’s website offers lots of other information about their Atmos system: a list of theaters wired for Atmos, a roster of films mixed in the process, and a short video explaining some of the differences between Atmos and other systems.

Information about Brave in Atmos can be found in two articles published by The Hollywood Reporter that are available here and here. There’s also a video interview with Brave’s sound design team. A brief history of the El Capitan can be found on the theatre’s website.

Film scholars Jay Beck and Mark Kerins both have written excellent histories of Dolby’s Atmos’ predecessors. Beck’s 2003 Ph.D. dissertation, “A Quiet Revolution: Changes in American Film Sound Practices, 1967-1979,” offers a terrific account of Dolby’s innovation of its pioneering four-channel stereo system. For a sampling of Beck’s analysis of Dolby Stereo aesthetics, see his essay, “The Sounds of ‘Silence’: Dolby Stereo, Sound Design, and Silence of the Lambs” in Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound, coedited by Beck and Tony Grajeda. Kerins’ work, on the other hand, focuses more squarely on Dolby 5.1 and what he calls a “digital surround sound style.” See Kerins’ Beyond Dolby (Stereo): Cinema in the Digital Sound Age.

For more on Atmos, see Eric Dienstfrey’s excellent explanation on our UW media blog, Antenna.

Wanda, the biggest cinema chain in China and purchaser of the AMC chain in the US, recently announced a major commitment to Atmos in its Mainland cinemas.

16, still super

From Lost & Found Film Club.

DB back:

While I was semi-snowbound in Evanston, IL, messages kept rolling in. Many of them were responding to my account of surrendering my 16mm movies and gear. That post’s whiff of nostalgia was caught by Gary Meyer, co-director of the Telluride Film Festival.

Don’t get me started on 16mm memories. I started showing movies in 8mm at about ten years old and by thirteen I had two for changeovers on silent classics rented from Cooper Films in Chicago. For about $2 I got a full feature and short including postage. Using my parents’ record collection I could score the films. . . .

Graduated to 16mm in high school when a local church and the library each offered use of their projectors and I started collecting prints seriously. In college I got a job in the media center showing films, cleaning prints and projectors. When the department decided to buy Bell & Howell Auto-Shreds, they sold off the old projectors for $50. I knew each machine intimately and selected the quietest, gentlest RCA 400 which I still have in a booth in my basement. One of my favorite projectors.

With 16mm projectors I have shown movies on garage doors from my apartment, in a barn, an orchard or two, and most famously on clouds, which resulted in the police department getting many phone calls about aliens.

Gary reports that his former venue, the Balboa Theatre, has given its theatrical Eiki projector to the San Francisco State University film department, but it can be borrowed back if ever needed. A more acute sense of the passing of an era was reported by program curator and Czech arts consultant Irena Kovarova:

One of the sad moments in my film history was being invited to the Czech Embassy in Washington, DC to visit a room of 16mm film piles. I was asked to pick and choose which ones should be saved and which would be chucked away (the majority). It was a collection of films that the Embassy inherited from the Communist-era offices when the staff was shipped films for their entertainment (Czech popular comedies) and of course tons of “travel” and “propaganda” stuff. It was impossible to know what was really there and a lot was mediocre, but still such a sad thing that no one could really dig in and explore.

Secrets of the Incas, and non-Incas

Projection booth, Cleveland Cinematheque.

But there was good news too. In the course of that entry, I said that 16 was “nearly dead” as an exhibition format. Trust this blog’s alert readers to give a more upbeat emphasis and offer some weighty counterexamples. Don’t hesitate to use the hyperlinks!

I was confirmed in my belief that archives will keep the format going. I hear from our old friend Antti Alanen of the National Audiovisual Archive of Finland, that 16 flourishes in Helsinki.

We still keep screening 16mm regularly at Cinema Orion, and for the moment print access is still good. We recently showed three programs of Stan Brakhage movies (from Canyon Cinema) and one programme of Rose Lowder movies (from Light Cone of Paris), all in the original format of 16mm, all prints and colours perfect.

I haven’t seen Brakhage on DVD, but those who have remarked that it is not the same thing. There is something about the special sensuality of 16mm which is essential to the Stan Brakhage experience. All of those films fill up the senses.

Besides Canyon Cinema and Light Cone, LUX in London still seems to be well-stocked with good 16mm prints in commercial distribution.

Bracing news. Antti mentions as well that he used to be able to access 16mm films made for the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, but now the agency has realized that the prints are irreplaceable and provide digibeta copies instead. The loss for showing is a gain for preservation.

I indicated as well that colleges, universities, and museums will probably maintain 16mm prints and showings. My correspondents have confirmed it, and offer some ripe local detail. Tracy Stephenson of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells me that they have shown films since the 1930s and may be the only venue in Houston that still screens 16. They have a program of jazz shorts coming up in June.

Here’s John Ewing of Cleveland:

I still show 16mm on occasion (and two-projector 16mm at that) at both of my venues: the Cleveland Cinematheque and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In fact, I just ran the 16mm program from the 50th Ann arbor Film Festival tour last Thursday night at the Cinematheque. Last time I showed 16 at the art museum was in December when we screened an IB Tech print of Secret of the Incas, from the Academy Film Archive.

From the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Brian Hearn writes:

We are pretty serious about 16mm and maintain a modest collection of about 500 prints, ranging from Lumiere Brothers shorts to studio features to avant-garde to educational films to 70s exploitation trailers. As the film medium dematerializes it makes me appreciate our collection even more, vinegar and pink fading prints included!

Calling a collection of 500 titles modest makes me grin (in envy). On the university side, Jon Vickers supplies other breathtaking information:

Indiana University Cinema programs from the University’s 16mm collection on a regular basis, with 16mm screenings at least once each month. In the IU Libraries Film Archives, there are over 80,000 items, the majority being 16mm. Within that collection is Lilly Library’s David Bradley Collection, spanning the history of cinema in the US and Europe, including classic, obscure, and some unique titles. We dedicate a series each semester to the holdings within the Bradley Collection (programmed by Film and Media Studies grad students), as well as program from the educational/non-theatrical collections and holdings.

We can’t imagine a day when we will stop screening 16mm.